Abstract

The European Green Deal (EGD) has become a key reform process in the European Union with a major impact on energy reforms in the Member States (MS). At the national level, the discourse around EGD and the Fit for 55 package plays a crucial role in shaping perceptions and potentially influencing behaviour. While scholars have examined particularly the EU discourse on the EGD, this paper focuses on Czechia and Sweden, two MS with contrasting attitudes towards renewable energy deployment and climate protection. Using the methodological framework of the Discourse-Historical Approach, the comparative analysis examines how EGD is framed within political and media discourses in these countries during the first phase of reform implementation (2019–2022). The main findings suggest that despite contextual differences, EGD appears to be universally accepted and shows resilience even in the midst of external and internal changes. Notably, although the argumentative strategies differ, the overarching acceptance of EGD remains consistent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The European Union (EU) has consistently championed climate action and set ambitious energy targets (EC, 2024). At the heart of these efforts is the 2019 European Green Deal (EGD), serving as a comprehensive roadmap of key policies to drive the EU’s climate agenda to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, including through a massive reduction in the use of fossil fuels (EC, 2019; EC, 2022); specific measures and legislation were developed by the 2021 Fit for 55 (FF55) packageFootnote 1 (European Council, 2023; Schlacke et al., 2022). The adoption of the EGD and FF55 package was the culmination of a debate on climate protection and is the result of the general acceptance of a certain ideology of environmental protection (Tews, 2015) and sustainable practices, which has been established and supported by the European Commission (Maltby, 2013; Skjærseth, 2017; Siddi and Prandin, 2023). The expected major structural changes in the energy sector, the economy and society as a whole, while challenging and costly, represent an industrial and economic opportunity (Siddi, 2016; Jerzyniak and Herranz‐Surrallés, 2024).

The impact of the adoption of the EGD is not exclusive to the European economy and society but has significant political implications at both EU and Member State (MS) levels (von Malmborg, 2023). Research on EGD and FF55 does not have to focus exclusively on the material level of its implementation, legislative processes and action-taking; discourse, narratives and stories are also relevant (Domorenok and Graziano, 2023). In doing so, EGD has become part of the discourse on energy policy at the EU and national level; the fight against climate change has become its justification as an imperative for the EU and its MS (Schunz, 2022). This being said, our aim is to enrich the academic literature by examining discourse in the MS with recognition of its relationship to the European level, since scholars have so far concentrated on analysing discourse at the EU level.

The focus on energy policy discourse is relevant to the assessment of EGD and its impacts for several reasons. First, discourse is not a mere reflection of material reality, but reflects the underlying thought framework and cognitive processes of a given actor. The discourse on energy policy in the EU is socially constructed and at the same time part of the social construction of reality (Simmerl, 2011). Simultaneously, discourse changes over time, and these changes may signal not only changes in material conditions, but especially the influence of other actors’ discourse. Finally, discourse has the power to change the behaviour of actors (in this case, the MS) and, therefore, the nature and shape of the instruments and institutions that these actors create and shape.

Thus, a comparative case study was chosen to analyse political and media discourses in Czechia and Sweden regarding the EGD, which can be considered a pivotal moment in the development of EU energy policy. The aim of the paper is to analyse the political and media discourse on the EGD in the Czechia and Sweden in the first phase after its adoption between 2019 and 2022. We claim that analysing discourse at the political level and in the media provides insights into how the debate on the EGD, framed by EU decisions, is conducted across the MS (Eising, Rasch and Rozbicka, 2015). In order to uncover how the discourse on the EGD is framed (by politicians) and presented (often through the media) to the general public, it is necessary to examine both types of discourses simultaneously. While pursuing this, the following research questions were set: (1) What topics and argumentative strategies can be observed in political and media energy discourse in relation to the EGD? (2) Are there changes in the discourses over time-related to domestic political changes or major events in European/global context?

The theoretical foundations are constructivism, energy discourse and securitisation. In line with this, the methodological framework draws on the Discourse Historical Approach (DHA) which claims that discourse is both socially constructed and constructive (Patton, 2002; Wodak and Krzyżanowski, 2008; Reisigl, 2014, 2017; Wodak, 2015; 2020; Rheindorf, 2022). Hence, investigating the intersubjective construction of the EGD in two seemingly different countries may shed light on how successful and efficient its implementation might be. Practically, the DHA consists of two levels of analysis. While the first one explores the topics that are discussed in the selected discourse, the second, in-depth level of analysis focuses on argumentative strategies, or the topoi.

The article is divided into five parts. The first part presents the academic debate on energy policy in the EU in relation to the discourse and the second part introduces the theoretical and conceptual background. The third part presents the case selection and methodological framework, and, in line with the DHA, the article encompasses a broader historical, legislative and socio-political context of current affairs (Wodak and Krzyżanowski, 2008; Reisigl and Wodak, 2009). The fourth part then deals with the results of a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the political and media discourses in both countries with an emphasis on identifying the steps and the most significant differences. The final part provides specific findings, particularly with regard to developments over time.

Academic debate on energy policy in the EU: state of art

Academic research in the field of energy policy has already addressed discourse in reference to the constructivist approach in IR (Wurzel, Liefferink and Di Lullo, 2019; Tichý, 2019; Hansson, 2020; Knodt and Ringel, 2022); but to a lesser extent than in the case of climate change and sustainable development, where critical discursive analysis was used in this context (Schunz, 2022; Wang and Huan, 2023). In particular, scholars have focused on the topics of securitisation of external dependence (Heinrich and Szulecki, 2018; Sperling and Webber, 2019; Harub, 2022), specifically in case studies focusing on Russia as a major energy supplier to the EU (Judge and Maltby, 2017; Hofmann and Staeger, 2019; Tichý, 2019; Siddi, 2018, 2020; Tichý and Dubský, 2020; Meyer, 2024), and the concept of Europeanisation (Tews, 2015; Solorio and Jörgens, 2020; Dupont, 2020). Also, they have used discourse to analyse the potential of the EU as an actor in framing the energy policies of the EU MS (Eising, Rasch and Rozbicka, 2015; Daviter, 2018; Goldthau and Sitter, 2020; Siddi and Kustova, 2021).

Pertaining to the EGD and FF55, research has concentrated predominantly on the EU level (Machin, 2019; Ossewaarde and Ossewaarde-Lowtoo, 2020; Eckert and Kovalevska, 2021; Schunz, 2022; Jerzyniak and Herranz‐Surrallés, 2024; Molek-Kozakowska, 2024), and sporadically on the MS level (Strunz, Gawel and Lehmann, 2015; Niskanen, Anshelm and Haikola, 2024). Despite recognising there is also a relation between the EU and MS levels, it was not examined in detail. Scholars have not attempted to distinguish between the implications of the formal implementation of EU energy policy by the MS and the reciprocal role of EU and MS energy discourse, including possible changes in their approaches. This research gap can only be filled by systematically exploring MS’ discourses at the national level in the context of EU energy policy development. Indeed, while attention has so far been paid to the discourse at the EU level, it seems appropriate to include the MS level as well, since (1) it is the MS that co-design EU energy policy within the Council of the EU (Wurzel, Liefferink and Di Lullo, 2019), and (2) it is the MS that are primarily responsible for the implementation of the objectives of the EGD (they will reform their economies, in particular the energy sector, in order to implement the EGD).

The power of discourse: the EU’s energy policy through the lens of social constructivism

Our article is theoretically anchored in social constructivism (Hopf, 1998; Checkel, 1998; Adler, 1997; 2013; Zehfuss, 2002; Simmerl, 2011). In contrast to the primary focus on the material world, social constructivism addresses the immaterial world of shared meanings, intersubjective perception and emphasises the study of discourse, when especially language is in the centre of research (Jones, 2016; Domorenok and Graziano, 2023). Discourse is constituted by reality and at the same time constitutive of it (Simpson, Mayr and Statham, 2019; Johnstone, 2019). Thus, the role of social interactions and communication is emphasised (Adler, 2013).

The discourse represents the way an actor reflects and interprets reality, reflects the cognitive processes used by the actor, and can indicate the intentions and reveal the priorities of the actor (Goddard and Carey, 2017). In doing so, discourse contains recurring themes and narratives, is used to frame an issue, and controls the way society conceptualises the world (Hajer and Forester, 1993). Actors seek to dominate discourses, to assert their interpretations, to participate in shaping the preferences of other actors (Zehfuss, 2002); the choice of certain solutions is the result of accepting the dominant discourse. It is then not possible to confirm the assumption of the formation of national preferences based on the rational assumptions of liberal theories and their importance for shaping the EU’s own policy as a search for a common solution at the EU level as international negotiations of MS in the form of a rational game (Moravcsik, 1993, 2002).

On the contrary, the dominant discourse makes it possible to emphasise the role of the EU as a framing actor (Eising, Rasch, and Rozbicka, 2015; Daviter, 2018), which is able to influence the policy of the MS with the help of discourse (cf. Checkel, 2023), even if it does not correspond to their rational choice. In the case of ongoing significant changes (such as the energy sector in response to climate change and the implementation of the EGD), social constructivism is an approach pointing to possibilities and ways of doing things (Galbin, 2014). Dominant discourses enable and legitimise political decisions (Ansari, Wijen and Gray, 2013; Siddi, 2020b) and are a result of the internalisation of values, norms, and ideas, as well as responses to the societal environment. The search for social consensus regarding the protection of livelihoods and the fight against climate change then plays a crucial role (Eckert and Kovalevska, 2021). This gives its implementation higher priority and legitimacy as EGD can become a strategic concern (Judge and Maltby, 2017; Harub, 2022; Domorenok and Graziano, 2023). Thanks to the EGD, the power structures of decision-making at the EU and national level remain more or less unchanged but are legitimised by the discourse of green growth (Ossewaarde and Ossewaarde-Lowtoo, 2020; Molek-Kozakowska, 2024).

An important concept associated with social constructivism is securitisation (Buzan, Wæver and De Wilde, 1998; Balzacq, 2005, 2009; Balzacq, Léonard and Ruzicka, 2016), which can be applied to climate change and energy policy, including the implementation of the EGD (Judge and Maltby, 2017; Heinrich and Szulecki, 2018; Hofmann and Staeger, 2019; Harub, 2022). In an international political perspective, securitisation is a process where a certain issue/problem (in our case, climate change and the fight against it) becomes a security issue/problem/threat based on the intersubjective interpretation and presentation of actors. This process represents an extreme form of politicising the issue; it is intentional and allows such issue/problem to be prioritised for resolution (Knodt and Ringel, 2022). This is not necessarily because of an actual threat, but because the issue is presented as a threat. A fundamental role is played by verbal expression, a speech act, whether it is political discourse or media (Balzacq, 2005).

Meanwhile, the EGD debate is part of the energy discourse as a fundamental interpretive framework for policy and media debates in MS for analysis; with energy policy (Machin, 2019; Eckert and Kovalevska, 2021; Schunz, 2022) and energy security (Heinrich, and Szulecki, 2018; Harub, 2022; Ah-Voun, Chyong and Li, 2024) at the centre of the energy discourse. Energy security, however, is not understood in a minimalist definitional form as ensuring stable and continuous energy supplies at affordable prices but reflects factors such as the identity, values, interests and preferences of MS and European institutions (Alhajji 2014; Eckert and Kovalevska, 2021). The energy discourse is reflected in political debate (in the broad sense), foreign policy debate (including the relations to the EU) and security policy in the context of energy (cf. Tichý, 2019). Energy discourse actors respond to stimuli coming from the European level of energy policy and this allows to link the topic of energy policy to the framing of the identity of the MS as part of EU institutions (Eising, Rasch, Rozbicka, 2015); also in relation to the EGD. Emphasising the security dimension helps to understand the interpretation of energy and transition-related phenomena as security threats, where in the case of EGDs, the threat of climate change can be operationalised, as well as the threat of dependence on energy imports (especially from Russia) (Siddi, 2020a). Thus, it is possible to determine whether the topic of EGD is securitised (Szulecki, 2018; Hofmann and Staeger, 2019; Sperling and Webber, 2019) in the media or political discourse of the MS and what argumentative strategies associated with this process are used. Overall, this broad and complex perspective on the perception of energy discourse makes it possible to identify and analyse diverse argumentative strategies within it.

Research design: case selection, data collection, and methodology

In this comparative case, study aimed at analysing the discourse on the EGD in selected MS, Czechia and Sweden were selected for analysis for the following reasons. On the one hand, they are countries of the same size in terms of population which allows for a meaningful comparison. On the other hand, they represent a case of diversity, with one country representing the Central European region (and at the same time the “East” of the EU) and the other a traditional part of the “West” in Northern Europe, which suggests in advance possible differences between them. Indeed, the energy mix of the two countries is distinct, especially with regard to the share of renewables, even though both countries agree on the role of nuclear energy in their energy mix (IEA, 2023; Kratochvil and Mišík, 2020). Also, their attitudes towards the deployment of renewables and the emphasis on climate protection are considered diverse (Gökgöz and Güvercin, 2018; Kacperska, Łukasiewicz and Pietrzak, 2021). These significant differences in their energy mixes and in the emphasis on climate protection and reform of national economies might foreshadow differences in the reception of the EGD in both countries.Footnote 2 The selection of the two countries as most different cases leads to the hypothesis: political and media energy discourses in the context of the EGD will differ with respect to different themes and argumentative strategies.

The research design is as follows: Firstly, since our main concern is to examine the official positions of both countries, the texts were scraped from the official websites of the Czech and Swedish governments, and statements of the leading political representatives debating the EGD and the FF55 were taken into account (the Prime Ministers and ministers responsible for energy and climate; in the case of Czechia: the Minister of Industry and Trade and the Minister of the Environment; in the case of Sweden: the Minister for Policy Coordination and Energy, the Minister for Energy and Digital Development and the Minister for Climate and the Environment). Then, three leading and representative media outlets from each country were selected (iDNES.cz, Novinky.cz, and HN.cz for Czechia; and GP.se, SVD.se, and DN.se for Sweden) and from these, articles discussing the EGD and the FF55 were scraped. In this case, other actors, such as representatives of opposition parties or businesses, were also analysed if they were covered by the media. This allows us to examine the media discourse in its full scope.

The timeframe examined focused on the first phase of the implementation of the EGD, covering its adoption, implementation in the form of the FF55 package, up to the first response to Russian aggression in Ukraine in the form of the REPowerEU announcement; specifically, it covers November/December 2019 and ends at the end of June 2022. This timeframe was chosen to allow for a comprehensive analysis of the discourse following the announcement of the EGD, but also to ensure that the results are not completely dominated by the EU’s response to the events of 2022, which we consider to be the second phase. The EU’s decision to completely cut itself off from energy supplies from Russia and to suspend cooperation with it due to the aggression of Ukraine in 2022, the deepening of energy cooperation with Ukraine and its support in the war with Russia are so fundamental that they accelerate not only the energy transition plans, but especially the EU discourse, which is characterised by the association of the EGD with energy security and the further securitisation and geopolitisation of energy policy (Siddi and Prandin, 2023; Ah-Voun and Chyong et al., 2024; Herranz-Surralles, 2024).

The documents were scraped partially via the R and Python programmes and partially manually, since the GP website did not allow for automatic scraping. Then, duplicates were identified, all the data was manually cleared, and non-relevant articles were deleted (e.g. articles about the US New Green Deal or the Swedish national project bearing the same name). The data collection was done in R (using the libraries rvest, tm, httr, tidyverse, ggplot2, and SnowballC) and Python (using the libraries pandas, requests, BeautifulSoup, and plotly). The scraping enabled the creation of a dataset containing 874 entries. Each entry also included categorisation and meta-information: the country of origin (Sweden or Czechia), the type of discourse (political or media), the concrete source (a ministry, a newspaper) and the date of publication (the day, month and year)Footnote 3.

Secondly, the data was analysed quantitatively. The distribution of the total frequency of EGD and FF55 terms in both countries over time was observed. In order to unveil the topics related to the key terms EGD and FF55, quantitative tools used for extracting keywords necessary for further qualitative analysis were applied. Specifically, a keyword frequency analysis (under the assumption of hegemonic interpretation) and a textual context quantification served as a basis for topic modelling and qualitative analysis using NVivo (Jacobs and Tschötschel, 2019). A list of the most frequent words in the dataset was therefore created. Among the 20 most frequent words in both languages (excluding stop words), a number of secondary keywords were identified. Keyness is not a widely agreed-upon category, since it is influenced by individual settings and parameters, but Culpeper and Demmen (2015) suggest that it is the first statistical step in a discourse analysis. Moreover, the arbitrariness can be limited by combining a quantitative and a qualitative approach.

A simple frequency analysis must be complemented with a more detailed approach to prove a close concordance rather than mere co-occurrence. We follow a common corpus linguistics method, namely that of key words in context (KWIC), where an n-gram of key words (called the key terms EGD and FF55 in this paper) is identified and its immediate context is highlighted. To make this method more robust, the most frequent words are also weighted in order to assess which frequent words appear more closely to the key term EGD or FF55 (and thus are more important). See the scoring formula applied in our dataset below (Equation 1).

Equation 1: The scoring formula

ω = word to score; A = set of articles; K = set of keywords; a(k) = k-th word of article a; len (a) = length (number of words) of article a. Source: Compiled by the authors.

The most common words appearing close to the terms of FF55, EGD, and their translations were selected based on a score computed from their proximity to the keywords, as well as the overall numbers of occurrences (see Table 1 below).

Thirdly, two-stage qualitative analysis was conducted, which will both focus on prominent themes and reveal argumentative strategies. The qualitative coding proceeded in the NVivo programme. The coding was informed by the theoretical framework, but mainly led by data, i.e., open or data-driven coding was employed (Gibbs, 2018). Specifically, based on the initial observation of a sub-sample of data, major topics and topoi were identified and preliminary names were developed in NVivo. Both the theoretical anchoring and official priorities of the EU were considered.

Then all the data was coded, the topoi were amended accordingly, and based on this coding, the analysis on both levels of the DHA proceeded. While the combination of theoretical and data-driven coding is possible within the DHA (Krzyżanowski, 2019), the main added value is considered to be the originally developed topoi. Indeed, the in-depth analysis allows for a deep and systematic interpretation of how the EGD is actually framed in both countries since even the same topics might be introduced in a different way (Reisigl, 2014). Particularly, the in-depth analysis explores the representation of relevant social actors and their argumentative strategies (topoi). The argumentative strategies are to be perceived as linguistic and cognitive processes of problem-solving which consist of relatively coherent statements. The aim of such statements is to justify what is right and wrong by convincing or manipulating, in both cases either openly or implicitly (Krzyżanowski, 2015; Reisigl, 2017; Rheindorf, 2022).

Main findings of the analyses of the energy discourses on the EGD in Czechia and Sweden

The results of quantitative analysis of the media and political discourses

It is at first important to notice the global differences between the Czech and Swedish media and political discourses. Figure 1 summarises how frequently the searched key terms EGD, FF55 and their translations appear.

Observation of the intensity of the discourse suggests that it does not correspond to the perceived importance of EGD as a priority for the EU. The chart shows that when the EGD was announced, the Swedish media reported on it extensively, but it did not attract much attention in Czechia or among Swedish politicians. In Czechia, almost no media coverage could be observed until July 2021, when the FF55 package was proposed. Since then, in contrast, the number of occurrences of the terms has been skyrocketing. Also, the Swedish media has paid more attention to the EGD/FF55. The EGD became a hot topic before the Czech parliamentary elections in September 2021, but after the elections, interest in them dropped again. Even the war in Ukraine has not changed this trend. Increasing coverage can be seen again at the end of the reporting period in June 2022, when the EU ministers agreed on new energy efficiency and renewable energy targets for 2030.

However, the increase in the intensity of media discourse in Czechia in 2021 may be related to another fact. Russia started to reduce gas inflows to European markets as early as the turn of May/June 2021 (which could have been a step taken in preparation for the aggression against Ukraine) and this led to manipulations of higher gas prices. Thus, energy prices in Europe rose during the summer and autumn of 2021 (when the threat of a Russian invasion of Ukraine becomes imminent, the issue of energy prices ceases to be crucial).

Subsequently, a comparison was made of the overall occurrence of keywords in each type of discourse in the countries examined (see Fig. 2).

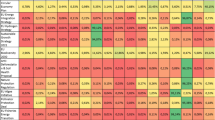

The comparison of the total occurrences of the keywords across the countries and types of discourse. Translation (y-axis, top to bottom): CZ political discourse: industry, price, resource, company, problem, measures, gas, finances, citizen, emissions, society. CZ media discourse: price, gas, resource, emissions, company, industry, society, problem, measures, finances, citizen. SE political discourse: climate, environment, emission, possibility, fossil, carbon dioxide, Paris agreement, world. SE media discourse: climate, emission, environment, world, carbon dioxide, fossil, Paris agreement, possibility. Source: Compiled by the authors.

In the political and media discourse, the accentuated topics differ for the observed countries quite substantially: (1) Whereas in the Czech political discourse, words such as “price“, “industry” and “firms” are the most frequent, the Swedish discourse highlights the scientific dimension of climate change (“emissions”, “environment”, “climate”). (2) An interesting comparison can be seen when Czech politicians refer to the EGD as a “problem”, while it is framed as an “opportunity” in Sweden. (3) Also, the frequency analysis shows that “citizens” are a frequently debated topic in the Czech media and politics, but the topic does not appear with such a frequency in Swedish discourses.

Adjusting the calculation according to the scoring formula applied to the observed data set (see Equation 1) allows us to present more detailed results, which are included in the Table 1.

From the results thus obtained, the following can be stated: (1) In texts from both countries, climate-related issues (e.g., the climate package) are predominant in the direct proximity of the terms EGD and FF55, but it seems that the framing and importance of this topic are different (see the qualitative part of the paper). (2) In addition, the specificities of both countries need to be observed. Although the word “problem” appears repeatedly in the Czech media and political discourse, it is not positioned in the immediate vicinity of the term EGD or FF55. Therefore, it can be argued that the association is looser and based on a broader context, which will be further analysed in the qualitative section (see the discussion of the topos of a financial burden). (3) Another tendency is the high number of occurrences of the words “citizen” and “company” in the Czech texts, but not in the Swedish ones. (4) While in Czechia the issue of coal is often associated directly with the EGD, in Sweden the issue which the EGD is most often associated with is deforestation. These differences confirm a specific context of the reality of the energy sector and the economies of the countries examined.

Moreover, the proximity of the words in the discourse confirms that the Czech economy is energy-intensive, which is related to the position of industry in the EGD generation. Czechia is still dependent on the coal industry and the automotive industry (Škoda as part of the Volkswagen concern) plays a key role. This seems to lead to scepticism about the possibilities of energy transition, including a strong voice of climate change deniers (see e.g., the 2008 book by the former Czech President Václav Klaus “Blue Planet in Green Shackles”, published with the financial help of the US libertarian/climate denier Competitive Enterprise Institute (Bolkestein, 2008) and later translated and distributed in Russia by LukOil). Hence, Czechia´s energy sector has been closely tied to Russia. Until 2022, it was highly dependent on Russian gas, especially at the household level. In terms of nuclear energy, even after Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, nuclear fuel was supplied to Czechia (however, the final 3 deliveries were made with Westinghouse being the new supplier).

This is not the case for Sweden, which is not dependent on energy from Russia, and the complete cut-off from Russian supplies has not had major consequences for it (there is no feeling that it had to rely on “cheap Russian energy”). In Sweden, the car industry has also been a central political factor in the past (Volvo, Scania, Saab), but its role has recently diminished, and the Swedish economy is not dependent on it. Volvo’s sales to China and the preference for e-vehicles may also play a role. Sweden’s energy mix is already very green, and the country, therefore, benefits greatly from EGD, not least because of its mining and metal industries (raw materials and technology needed to implement EGD).

The results of qualitative analysis of the media and political discourses

The entry-level qualitative analysis: prominent topics

In continuation of the quantitative analysis, which has shown similarities, but also several specificities of both countries’ discourses on a micro level, a broader qualitative approach needs to be taken. Within the first level of the qualitative analysis, the main topics were searched for. These were identified according to the topics related to the EGD as presented by the EU itself (EC, 2022) and with the additional help of the keywords found in the quantitative analysis. The results are shown in Table 2.

The findings again show some differences. Firstly, while the predominant topic in Czechia was energy, it was the climate in Sweden. Of course, these two topics are interrelated, but the different framings in the two countries are quite evident. Whereas Czechia emphasised the need to ensure sufficient energy sources for reasonable prices to protect Czech citizens and companies, Sweden pointed out the need for all energy to be fossil-free and clean. Secondly, in line with this, Czechia insisted on EU funds supporting its transition towards clean energy so that the financial burden on its businesses and citizens would be eliminated, whereas Sweden refused any new funds since they would only prolong the transition and enhance emissions. Specifically, the Czech Minister of Industry Karel Havlíček stated that it is key for the EU to acknowledge nuclear energy as a sustainable source because otherwise nuclear investments would not be favourable and energy prices might increase for Czech customers, which would be unacceptable (Havlíček, 2020). Similarly, the Czech Minister of Environment, Anna Hubáčková, was explicitly in favour of a new social fund to help compensate poorer families for the costs of the beginnings of the transition towards a low-emission economy (Hubáčková, 2022). Contrarily, the Swedish government insisted that there is “no need for additional budgetary mechanisms since extensive EU funds are already allocated to the climate transition within the EU budget and the recovery plan,” and “that the transition to fossil-free energy resources needs to be accelerated” (Government Offices of Sweden, 2021a).

Thirdly, another relevant issue discussed in both countries is transport, particularly in connection with electric cars. In Czechia, some politicians were cautious with regard to setting the deadline in 2035, which is presented as too ambitious. The Minister of Environment Richard Brabec even claimed that if Czechia demonstrated an active preference for electric cars too early, people might choose to keep their old cars instead of buying a very expensive electric car, which would lead to unintended consequences (Brabec, 2021). Also, Prime Minister Petr Fiala preferred a slower ban on cars with a combustion engine (Fiala, 2021). As for Sweden, the Swedish Minister for Climate Annika Strandhäll commented on the EU plan for stopping the production of cars with a combustion engine as follows: “I am very content with what we have achieved, even though Sweden wanted to go even further” (Strandhäll, 2022).

Overall, various aspects of the EGD were discussed in both countries. Also, all initiatives of the EU connected to the EGD and the FF55 were covered in both countries at least briefly (such as the circular economy, chemicals, batteries, or hydrogen power), which further demonstrates the relevance and importance of the EGD even though the attention paid to the EGD fluctuates diachronically and topics are framed differently in both countries as demonstrated in more detail below.

The in-depth qualitative analysis: argumentative strategies

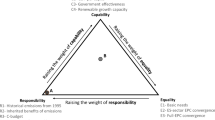

Pertaining to the in-depth level of analysis, seven topoi were developed to analyse and compare the discourses in Czechia and Sweden—see Table 3.

The results of the analysis point to the following differences in the discourses in the two countries and their argumentative strategies. Firstly, in Czechia, the most common argumentative strategy draws on the financial impact of the EGD on the Czech public. The topos of a financial burden is employed by both politicians and the media. The crux of the matter is that neither the Czech citizens nor Czech companies must suffer from the impact of the EGD. As stated above, Czech representatives require nuclear power and temporarily also gas to be considered sustainable, which should help solve the problem of increasing energy prices. Specifically, vulnerable customers should be protected from energy poverty (Ministry of Industry and Trade, 2021a; Ministry of the Environment, 2022a). Often, Czechia is compared to Germany within this topos: “given the energy mix, the structure of the economy and industry as well as the purchasing power of our citizens, the EGD commitments are much more demanding for Czechia than for Germany or other countries” (Ministry of Industry and Trade, 2021b). Hence, it is the financial implication that seems to be perceived problematically rather than the EGD as a whole. Moreover, the topos of a financial burden is usually framed as rational: “We are not saying no; we are pragmatic. We can´t end up like the yellow vests in France, where President Macron increased gas prices and the society did not accept it” (Brabec, 2021). This framing is not present in Sweden at all. Contrarily, the financial burden is perceived as necessary to save the climate. The message in both the political and the media discourse in Sweden is that if we do not invest now, the cost will be higher later: “A fiscal policy that lacks a clear green and long-term perspective will otherwise have disastrous consequences when the bill for the climate crisis comes” (DN Debatt, 2020).

Secondly, this contrast is mirrored in two following argumentative strategies, namely in the topos of competitiveness promoted by Czechia and the topos of leadership emphasised by Sweden. The Czech politicians and media are afraid that the EGD might decrease the competitiveness of Czechia and the EU as a whole since it is too ambitious, and if the biggest polluters such as China and India do not follow our demands, the EGD’s impact will be counterproductive. As Prime Minister Babiš said: “the EU cannot achieve anything without the participation of the biggest polluters, e.g., China and the USA (…). Despite these facts, the European Commission suggests further dangerous proposals (…). We do not know whether these goals [the FF55] are too ambitious” (Babiš, 2021). In Czechia, the topos of leadership is virtually missing. The fear of losing competitiveness is much more prominent than the urge to lead the rest of the world. Czech representatives claim that it will be very complicated for Czechia to fulfil all the EGD requirements as it is an industrial country heavily reliant on coal with an underdeveloped low-carbon economy. As Minister Havlíček argued: “We will rigorously require such a plan that will not harm the competitiveness of our car industry as it is key to the Czech economy” (Dvořák, 2021). This is not to say that nobody in Czechia considers the EGD as a great opportunity for modernisation and technological change, or a great opportunity to move forward by shifting the country’s mindset, but the people with such views are rather businessmen than politicians (Gallistl, 2022). The Swedish understanding is completely opposite. Swedish representatives claim that the EGD might increase the competitiveness of the EU, and that the EU must lead the rest of the world. Even Sweden itself is often pictured as a role model (Lövin, 2019). Similarly, the Swedish Minister for Infrastructure Tomas Eneroth said that the FF55 package “is nothing that inhibits competitiveness. It strengthens it” (Eneroth, 2021).

Thirdly, contrary to the first three topoi, there is rather an agreement on the following three topoi between the two countries. The topos of national interest is prominent in both countries. Czech representatives emphasise the need to allow nuclear energy and gas as transitional resources. This issue dominates both discourses in Czechia with an overall agreement among all the political parties (Czech News Agency, 2022). The goals of the EGD/FF55 are accepted but the emphasis is on Czechia as an industrial country where renewables are not sufficient and hence, other resources must compensate for the loss of coal, which is to be no longer used by 2030 (Ministry of Industry and Trade, 2021c). All political parties stress that each MS is different, and each national energy mix should remain within the discretion of the respective country. Another frequent argument is that impact studies for the EGD are completely missing despite them being considered of utmost importance since the EGD will have an impact on “everything—the whole society, companies, each citizen” (Government of the Czech Republic, 2021a).

In Sweden, although the country also uses nuclear power, the requirement to allow it is more complicated since some political parties push for renewables and do not promote nuclear energy. This clash of priorities was most visible when Minister Lövin had to go to Brussels to demand that nuclear energy be included in the taxonomy, while she and her party (the Green Party) were against it (Davidsson, 2020). The Minister for Energy in the following government, Khashayar Farmanbar, considered nuclear energy too expensive in comparison to other alternative energy sources and called it neither green nor renewable. He is even more critical of natural gas, rejecting it being included in the taxonomy (Farmanbar, 2022).

Apart from energy, the topos of national interest is prominent within agriculture. In particular, Sweden protests against the EU legislation on forests and demands that forests remain within the national discretion. Although Sweden acknowledges that forests must be protected and serve the purposes of climate protection, it opposes the EU legislation to be too detailed. The government “believes that forestry policy is a national competence, [and] new proposals must be in line with the possibility of sustainable active forestry and detailed regulation at EU level of what should be avoided in sustainable forestry” (Government Offices of Sweden, 2021b). Even the Swedish EU Commissioner (responsible for home affairs, not agriculture) Ylva Johansson intervened that Brussels should not decide about Swedish forestry (DN Sverige, 2021a).

Fourthly, while Czech representatives are very open in demanding that Czech interests and particularities should be considered, Sweden protects its own priorities more subtly. However, the core of the argumentation is similar and even supported by the virtual non-existence of the topos of cooperation, which is dominant in the EU discourse (EC, 2022). It seems that even when the two countries agree on the EGD as such, they still give a strong preference to their own interests or values, be it the protection of industry in Czechia or being a leader in climate protection in Sweden. Cooperation seems to be backgrounded at the expense of national priorities.

Finally, and surprisingly, given how the EGD is presented by the EU and in academic debate, it is very rarely securiticised (Siddi, 2020a). The topos of security were occasionally employed in Czechia after the Russian invasion, when it was particularly linked to national self-sufficiency of energy resources (Hilšer, 2022) and achieving energy independence through nuclear energy and renewables (Government of the Czech Republic, 2021a). Nevertheless, the prevalent framing is rather energy- and climate-related in both countries.

For the results of the analysis see Fig. 3.

Discussion of political specifics, dynamics and the overall assessment of the energy discourse

Above, the main topics and argumentative strategies in the media and political discourse in each country were analysed. Below, an overall assessment will be carried out.

Pertaining to the diachronic development of the discourses, it must be stated that the governments changed in both countries during the years 2019–2022. However, while the official discourse in Sweden has stayed more or less consistent, a discursive shift was observed in Czechia. Even though the government led by Andrej Babiš´s populist movement ANO, frequently criticised the EGD to the point of saying that it might be a disaster for Czechia, this was highly dependent on the context in which the statement was uttered (e.g., tearing the EGD to shreds during talks with the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán while being open to it when talking to Ursula von der Leyen about the National Recovery Plan) (Government of the Czech Republic, 2021b). Also, Babiš agreed with the EGD during the European Council meeting and admitted that climate change is a challenge that must be solved (Government of the Czech Republic, 2021c). His successor Petr Fiala and his government were more open to the idea of the EGD, which was even mentioned as a priority in their governmental programme and considered as an opportunity to invest in sustainable development and modernisation of the economy, while nuclear power and renewables were explicitly mentioned as means to achieve the EGD goals (Government of the Czech Republic, 2022a). In Sweden, both Stefan Löfven and Magdalena Andersson and the relevant ministers welcomed the EGD openly and supported an even more ambitious plan (DN Sverige, 2021b). In both countries, only a few actors explicitly reject the EGD, mostly representatives of right-wing populist parties (the Czech SPD and the Swedish Democrats). In Czechia, these were complemented by the President Miloš Zeman, who repeatedly claimed that the EGD should be abolished (Jeřábková, 2022).

Also, for the investigated period, two relevant milestones can be identified: (1) the Covid-19 pandemic and (2) the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In Czechia, since early 2020, when the pandemic started, many press statements of Czech politicians were opened with the topic of Covid-19, which was later succeeded by the EGD as the number two priority. On these occasions, the EGD was presented as a potentially important change for citizens and companies. The government and trade union representatives often emphasised that they would not allow people or companies to suffer from the EGD measures financially. Specifically, energy poverty was discussed heavily (Government of the Czech Republic, 2022b).

In Sweden, neither the pandemic nor the Russian invasion caused a change in the numbers or nature of the relevant published statements and articles. Most of the articles and statements studied here were published shortly after the EGD and the FF55 package had been presented, i.e., in December 2019 and July 2021. These were of a rather informative nature, explaining what the initiatives are about and how the leading Swedish representatives feel about them. Also, the Czech media devoted much more attention to the Russian invasion of Ukraine than the media in Sweden, which seems to be logical, since Czechia is much more dependent on Russian energy imports than Sweden.

Similarly, the two countries’ argumentative strategies also differed a lot after February 2022. While Sweden claimed that a quicker transition towards renewable energy and more investments into the EGD is needed, Czechia was more cautious regarding the EGD and insisted that coal should be allowed, at least temporarily, since renewables would not be sufficient. On the other hand, as Minister Anna Hubáčková said, the war in Ukraine does not mean that Czechia will not focus on topics related to the environment, that Czechia might postpone the fulfilment of the EGD or that Czechia would return to coal (Ministry of the Environment, 2022b). Thus, despite their different framings, both countries wanted to preserve the EGD. In Czechia, another topic was identified after the invasion, which was completely missing from the Swedish discourse, namely disinformation. On many occasions, it was mentioned that the EGD is criticised by Russian trolls and thus used as a weapon against the EU and renewables and, vice versa, in favour of Russian gas imports. However, overall, both countries emphasise that neither Covid-19 nor Ukraine should prevent the EGD from being implemented.

Moreover, no major differences were identified between the political and media discourses in each country or across the selected media outlets. The overall framing remained consistent with a few notable exceptions such as in case of iDNES.cz, which was much more sceptical about the future of the EGD after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The outlet paid attention to statements and opinions emphasising the need to make the EGD less ambitious and accept nuclear energy since renewables are neither sufficient nor reliable in Czechia, or explicitly rejecting the EGD as too radical or downright crazy. Other sources of data were more restrained and fact-based even when expressing dissatisfaction with the EGD. Interestingly, even a highly emotional politician, Andrej Babiš, often argued pragmatically about it. Although he criticised the EGD frequently, he did not forget to emphasise the need to protect the climate and that accepting the EGD means a lot of EU money for Czechia.

Overall, the perception of the EGD is rather positive in both countries. Hence, maybe surprisingly, the argumentation regarding the EGD is predominantly pragmatic in both countries. Albeit in Sweden, it is mostly explicit, while in Czechia it is often between the lines. Despite the agreement that the EGD is a good idea, the framing in the two countries differs. The hypothesis of the difference between the two discourses was thus only partially confirmed, particularly concerning the argumentative strategies. In Czechia, most of the analysed politicians argue that the idea of the EGD is good and that it is necessary and even inevitable to protect the climate and ensure clean energy, but they usually emphasise that it is necessary to take national specifics into account. In Sweden, national priorities are mentioned occasionally but overshadowed by the framing in which the EGD is desirable, but a more intensive plan should be enacted.

Conclusion

Czechia and Sweden occupy distinct positions in the realm of climate protection, shaped significantly by their energy sectors and economies. While Sweden stands as a climate champion, Czechia is often perceived as lagging behind with regard to EGD support as well as the energy-intensive model of the economy and the speed of implementation of changes. It was expected that differences in discourses between the selected MS are due to their economic, energy, and social specificities (Strunz, Gawel and Lehmann, 2015; Bocquillon and Maltby, 2020) which led us to hypothesise that discourses surrounding the EGD in the first phase of its implementation would diverge between these two countries. However, this hypothesis has not been fully verified by our research. Addressing our first research question, we find that the topics discussed in both Czechia and Sweden exhibit similarities, including energy, climate, EU funds, and transport. The nuances lie in how these topics are framed (prices, customers, firms, problems in Czechia versus opportunities in Sweden; EU funds as necessary in Czechia versus inessential in Sweden).

Pertaining to argumentative strategies (topoi), the topos of national interest are prominent in both countries. However, while this topos is expressed rather explicitly in Czechia, it is present primarily implicitly in Sweden. Also, other argumentative strategies show differences between the countries, with the Czech discourse being characterised by an emphasis on risks, namely concerns about the financial complexity, the possible loss of competitiveness, and the financial intensity of the reforms (topos of financial burden, topos of competitiveness). In contrast, the Swedish discourse sees the EGD more as a challenge that will bring Sweden and the EU a leadership position in the fight against climate change and strengthen their own positions and competitiveness (topos of leadership, topos of competitiveness).

A specific and essential finding is the fact that a security-based argumentative strategy is not present in the Swedish energy discourse in relation to the EGD and is also relatively absent in Czechia, although one might expect this argumentative strategy to resonate, especially after the Russian aggression against Ukraine (given the huge dependence of the MS on fossil fuel imports, especially from Russia) (Harub, 2022; Meyer, 2024). Indeed, securitisation is not employed in the media discourse regarding the severity of climate change, which can be considered a threat to European society and economy. Similarly, the securitisation of external dependence (Hofmann and Staeger, 2019; Siddi, 2018; 2020) is not fundamentally manifested. This justifies the need to implement the EGD as a way to reduce fossil fuel consumption, contrasting with the academic debate and European Commission argumentation (Skjærseth, 2017; Siddi and Prandin, 2023). Similarly, the topos of cooperation is virtually absent in both countries.

This leads us to answer the second research question, which shows that the discourse on the EGD (in the phase after its announcement and the first steps of implementation) seems to be rather resistant to socio-political changes in both countries (i.e., changes in the subsequent governments) but also to external (European and global) changes (i.e., covid pandemic, Russian invasion to Ukraine). The existence and necessity of the EGD seem to be broadly accepted in time despite all reservations. Indeed, the analysis of energy discourses in the political arena and in the media in Czechia and Sweden showed that the EGD is considered inevitable in both countries and if it is rejected, it is only political actors on the fringes of the political scene with a limited impact on the policy direction of these MS.

This could suggest the existence of a dominant energy discourse at the EU level, which shapes the interpretation of reality in the context of the EGD and determines the priorities not only of the EU but also of other actors (in our case the MS). The dominant discourse is thus essentially replicated in political and media discourse. The existence of a dominant discourse does not lead to the securitisation of climate change and dependency being used in the national discourse on the EGD (which has already been used in the creation of a dominant discourse at the EU level to legitimise political decisions) (Zehfuss, 2002; Siddi, 2020b). At this stage, the central power role of the European Commission is recognised, using narratives of the fight against climate change to justify the energy transition and its form. In doing so, it frames not only the MS’ own policies, but precisely their discourse (cf. Eising, Rasch and Rozbicka, 2015; Daviter, 2018; Eckert and Kovalevska, 2021). The EGD has gained wide acceptance among the MS surveyed and has overcome external and internal changes or shocks. The debate at the national level focuses on the implementation of the EGD while respecting national specificities.

For now, although it remains the case that the energy mix is determined by the MS themselves, and they will also implement reforms according to their interests, it is the influence of discourse that leads to a convergence of views among the MS. However, key internal factors of political will and implementation can be expected to come into play later, as the success of a decarbonised European economy depends not only on political commitment, but more importantly on capability and capacity. It will also be interesting to analyse the medium-term consequences of the Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2022. However, given the existence of a dominant discourse, it can be assumed that if the discourse on the EGD changes, it will depend more on the capacity or political will to implement it (either at the MS or the EU level) than on global trends in energy and international politics.

Data availability

Notes

As the FF55 package is a practical development of the EGD, we consider both terms as interrelated. For the sake of brevity, we do not always repeat both terms, since our main aim is to study the perception of the EGD.

The selection of the two countries is based on the perception that Sweden is traditionally seen as a leader in environmental protection, while Czechia is considered a laggard (cf. European Union 2024). Additionally, the choice was influenced by the practical consideration that the authors are familiar with both relevant languages.

The websites of both countries were searched for the lemmas “green deal” and “fit for 55”, and additionally the Czech sources were searched for the lemma “zelená dohoda”, and the Swedish ones for the lemma “gröna given”, including linguistic mutations of those key terms.

References

Adler E (1997) Seizing the middle ground: constructivism in world politics. Eur J Int Relat 3(3):319–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066197003003003

Adler E (2013) Constructivism in international relations: Sources, contributions, and debates. Handb Int Relat 2:112–144. Sage Publishing: London

Ah-Voun D, Chyong CK, Li C (2024) Europe’s energy security: From Russian dependence to renewable reliance. Energy Policy 184:113856

Alhajji AF (2014) Dimensions of energy security: competition, interaction and maximization. In: Sovacool BK (ed.). Energy security. Definitions and concepts of energy security. Sage Publishing, London

Ansari S, Wijen F, Gray B (2013) Constructing a climate change logic: an institutional perspective on the “Tragedy of the Commons”. Organ Sci 24(4):1014–1040. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1120.0799

Babiš A (2021) Pro jednotlivé členské státy je zcela zásadní zvolit si vlastní energetický mix k dosažení uhlíkové neutrality (It is crucial for individual Member States to choose their own energy mix to achieve carbon neutrality). https://www.vlada.cz/cz/clenove-vlady/premier/projevy/andrej-babis-pro-jednotlive-clenske-staty-je-zcela-zasadni-zvolit-si-vlastni-energeticky-mix-k-dosazeni-uhlikove-neutrality-191507/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Balzacq T (2005) The three faces of securitization: political agency, audience and context. Eur J Int Relat 11(2):171–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066105052960

Balzacq T (2009) Constructivism and securitization studies. In: The Routledge Handbook Of Security Studies. Routledge, London and New York. pp. 72–88

Balzacq T, Léonard S, Ruzicka J (2016) Securitization’ revisited: theory and cases. Int Relat 30(4):494–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117815596590

Bocquillon P, Maltby T (2020) EU energy policy integration as embedded intergovernmentalism: the case of energy union governance. J Eur Integr 42(1):39–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.170833

Bolkestein F (2008) Vaclav Klaus presents inconvenient truths. Blue planet in green shackles. Spil 247(2-3):40–43

Brabec R (2021) Bez plynu a jádra to EU nepodepíšu (I will not sign the EU without gas and nuclear power). https://www.idnes.cz/zpravy/domaci/richard-brabec-ano-elektromobil-eu-ovzdusi-emise.A210719_192012_domaci_wes (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Buzan B, Wæver O, De Wilde J (1998) Security: a new framework for analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers

Checkel JT (1998) The constructive turn in international relations theory. World Polit 50(2):324–348. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043887100008133

Checkel JT (2023) Identity politics and deep contestations of the liberal international order: the case of Europe. https://www.eui.eu/Documents/DepartmentsCentres/SPS/Profiles/Checkel/CwCWorkshopJune2023-CheckelPaper.pdf. (accessed 27 Oct 2024)

Culpeper J, Demmen J (2015) Keywords. In: Biber D, Reppen R (eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of English Corpus Linguistics (Cambridge Handbooks in Language and Linguistics). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Czech News Agency (2022) Politici oceňují návrh EK o jádru. Umožní nám to přejít na čisté zdroje, tvrdí ministryně (Politicians appreciate the EC proposal on the core. It will enable us to switch to clean sources, the minister claims). https://www.novinky.cz/clanek/domaci-politici-ocenuji-navrh-ek-o-jadru-umozni-nam-to-prejit-na-ciste-zdroje-tvrdi-ministryne-40382666 (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Davidsson M (2020) Lövin tvingas prata varmt om kärnkraft i EU (Lövin is forced to talk warmly about nuclear power in the EU). https://www.gp.se/nyheter/sverige/l%C3%B6vin-tvingas-prata-varmt-om-k%C3%A4rnkraft-i-eu-1.24667696 (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Daviter F (2018) The framing of EU policies. In: Heinelt H, Münch S (eds.). Handbook of European Policies: interpretive approaches to the EU. Edward Elgar Publishing

DN Debatt (2020) Använd den gröna given till att rädda Europas ekonomi (Use the green deal to save Europe’s economy). https://www.dn.se/debatt/anvand-den-grona-given-till-att-radda-europas-ekonomi/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

DN Sverige (2021a) EU:s nya skogsstrategi omgärdad av bråk (The EU’s new forest strategy surrounded by controversy). https://www.dn.se/sverige/eus-nya-skogsstrategi-omgardat-av-brak/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

DN Sverige (2021b) Polen hindrar EU från att enas om nollutsläpp till 2050 (Poland prevents the EU from agreeing on zero emissions by 2050). https://www.dn.se/nyheter/varlden/eu-har-enats-om-att-bli-klimatneutralt-2050-men-polen-slapar-efter/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Domorenok E, Graziano P (2023) Understanding the European Green Deal: a narrative policy framework approach. Eur Policy Anal 9(1):9–29. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1168

Dupont C (2020) Defusing contested authority: EU energy efficiency policymaking. J Eur Integr 42(1):95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1708346

Dvořák F (2021) Ministr Havlíček píše do Bruselu kvůli ekonormě: Euro 7 bude problem (Minister Havlíček writes to Brussels about the econorm: Euro 7 will be a problem). https://www.idnes.cz/auto/zpravodajstvi/karel-havlicek-euro-7-emise-automobily-prumysl-brusel-norma.A210921_161308_automoto_fdv (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

EC (2019) A European Green Deal, European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 11 Jan 2023)

EC (2022) A European Green Deal: striving to be the first climate-neutral continent.https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

EC (2024) EU Climate Action Progress Report 2024. Leading the way: from plans to implementation for a green and competitive Europe. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/document/download/7bd19c68-b179-4f3f-af75-4e309ec0646f_en?filename=CAPR-report2024-web.pdf (accessed 27 Oct 2024)

Eckert E, Kovalevska O (2021) Sustainability in the European Union: analyzing the discourse of the European Green Deal. JRFM, 14(2). https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:gam:jjrfmx:v:14:y:2021:i:2:p:80-:d:500748 (accessed on 15 Feb 2023)

Eising R, Rasch D, Rozbicka P (2015) Institutions, policies, and arguments: context and strategy in EU policy framing. J Eur Public Policy 22(4):516–533

Eneroth T (2021) Laddstolpar i mängd när EU ställer om (Charging poles in quantity when the EU changes). https://www.gp.se/ekonomi/laddstolpar-i-m%C3%A4ngd-n%C3%A4r-eu-st%C3%A4ller-om-1.61140758 (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

European Council (2023) Fit for 55. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/fit-for-55/#0 (accessed 3 Nov 2024)

European Union (2024) Attitudes of Europeans towards the environment. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/3173 (accessed 3 Nov 2024)

Farmanbar K (2022) Ministern: Kärnkraften är inte grön (The Minister: Nuclear power is not green). https://www.gp.se/ekonomi/ministern-k%C3%A4rnkraften-%C3%A4r-inte-gr%C3%B6n-1.63123427 (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Fiala P (2021) Nemusíme vše řešit zákazy, pokud se budeme chovat odpovědně, řekl Fiala (We don’t have to solve everything with bans if we act responsibly, Fiala said). https://www.idnes.cz/zpravy/domaci/rozhovor-premier-petr-fiala-koronavirus.A211219_112436_domaci_vank (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Galbin A (2014) An introduction to social constructionism. Soc Res Rep. 26:82–92

Gallistl V (2022) Ceny pohonných hmot se k předválečným hodnotám nevrátí, tvrdí šéf platební firmy CCS Jan Polívka (Fuel prices will not return to pre-war values, claims the head of the payment company CCS Jan Polívka). https://archiv.hn.cz/c1-67057110-ceny-pohonnych-hmot-se-k-predvalecnym-hodnotam-nevrati-tvrdi-sef-platebni-firmy-ccs-jan-polivka (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Gibbs G (2018) Analyzing qualitative data. SAGE, Los Angeles

Goddard A, Carey N (2017) Discourse: the basics. Routledge, London and New York

Gökgöz F, Güvercin MT (2018) Energy security and renewable energy efficiency in EU. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 96:226–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2018.07.046

Goldthau A, Sitter N (2020) Power, authority and security: the EU’s Russian gas dilemma. J Eur Integr 42(1):111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1708341

Government of the Czech Republic, (2021a) Tisková konference po jednání tripartity (Press conference after the tripartite meeting). https://www.vlada.cz/scripts/detail.php?id=187661&tmplid=50 (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Government of the Czech Republic (2021b) Tisková konference po jednání s maďarským předsedou vlády Viktorem Orbánem (Press conference after the meeting with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán). https://icv.vlada.cz/cz/media-centrum/tiskove-konference/tiskova-konference-po-jednani-s-madarskym-predsedou-vlady-viktorem-orbanem--29--zari-2021-190963/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Government of the Czech Republic, (2021c) Ursula von der Leyenová v Praze oznámila schválení Národního plánu obnovy ČR (In Prague, Ursula von der Leyen announced the approval of the National Recovery Plan of the Czech Republic). https://www.vlada.cz/cz/media-centrum/aktualne/ursula-von-der-leyenova-v-praze-oznamila-schvaleni-narodniho-planu-obnovy-cr-189816/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Government of the Czech Republic (2022a) Vláda Petra Fialy zveřejnila programové prohlášení, chce Česko posunout mezi nejvyspělejší země světa (The government of Petr Fiala has published a program statement, it wants to move the Czech Republic among the most developed countries in the world). https://icv.vlada.cz/cz/media-centrum/aktualne/vlada-petra-fialy-zverejnila-programove-prohlaseni--chce-cesko-posunout-mezi-nejvyspelejsi-zeme-sveta-193549/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Government of the Czech Republic (2022b) Tisková konference po jednání tripartity (Press conference after the tripartite meeting). https://icv.vlada.cz/cz/media-centrum/tiskove-konference/tiskova-konference-po-jednani-tripartity--18--ledna-2022-193800/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Government Offices of Sweden (2021a) Hoga energipriser och eus klimatpaket pa energiradsmote (High energy prices and the EU’s climate package on energy row mode). https://www.regeringen.se/artiklar/2021/12/hoga-energipriser-och-eus-klimatpaket-pa-energiradsmote/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Government Offices of Sweden (2021b) https://www.regeringen.se/artiklar/2021/10/fit-for-55-och-cop26-pa-eu-mote/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Hajer MA, Forester J (1993) Discourse coalitions and the institutionalisation of practice: the case of air pollution. The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning, editado por Frank Fisher y John Forester, 43–76. Duke University Press, London

Hansson SO (2020) Social constructionism and climate science denial. Eur J Philos Sci 10(37):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-020-00305-w

Harub L (2022) Securitisation of energy in discourse and practice. In: Harub L. Deconstructing ‘Energy Security’ in Oman. A Journey of Securitisation from 1920 to 2020. Springer, Singapore

Havlíček K (2020) Vláda schválila další kroky ohledně výstavby nového bloku jaderné elektrárny Dukovany a dala vicepremiérovi Karlu Havlíčkovi mandát k dalším jednáním (The government approved further steps regarding the construction of a new block of the Dukovany nuclear power plant and gave Deputy Prime Minister Karel Havlíček a mandate for further negotiations). https://www.mpo.cz/cz/rozcestnik/pro-media/tiskove-zpravy/vlada-schvalila-dalsi-kroky-ohledne-vystavby-noveho-bloku-jaderne-elektrarny-dukovany-a-dala-vicepremierovi-karlu-havlickovi-mandat-k-dalsim-jednanim--254262/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Heinrich A, Szulecki K, (2018) Energy securitisation: Applying the Copenhagen school’s framework to energy. Energy security in Europe: Divergent perceptions and policy challenges. Palgrave Macmillan Cham: Cham. pp. 33–59

Herranz-Surralles A (2024) The EU energy transition in a geopoliticizing world. Geopolitics 29(5):1882–1912. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2023.2283489

Hilšer M (2022) Kdo investuje na Ukrajině, kde bude hrozit obnova konfliktu, ptá se Hilšer (Who invests in Ukraine, where there will be a threat of renewed conflict, asks Hilšer). https://www.idnes.cz/zpravy/domaci/marek-hilser-prezidentske-volby-ukrajina-valka-invesice-rusko-konflikt.A220416_080756_domaci_knn (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Hofmann SC, Staeger U (2019) Frame contestation and collective securitisation: the case of EU energy policy. West Eur Polit 42(2):323–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1510197

Hopf T (1998) The promise of constructivism in international relations theory. Int Security 23(1):171–200. https://doi.org/10.2307/2539267

Hubáčková A (2022) Chceme podpořit nákup elektroaut pro občany (We want to support the purchase of electric cars for citizens). https://www.mzp.cz/cz/articles_20220614_E15-Chceme-podporit-nakup-elektroaut-pro-obcany (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

IEA, 2023. IEA: Countries and regions. https://www.iea.org/countries (accessed 5 May 2023)

Jacobs T, Tschötschel R (2019) Topic models meet discourse analysis: a quantitative tool for a qualitative approach. Int J Soc Res Methodol 22(5):469–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2019.1576317

Jeřábková D (2022) Fiala: Jestli měl Zeman s Green Dealem problém, měl to říct Babišovi (Fiala: If Zeman had a problem with the Green Deal, he should have told Babiš). https://www.novinky.cz/domaci/clanek/jestli-mel-zeman-s-green-dealem-problem-mel-ho-rict-babisovi-40382701 (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Jerzyniak T, Herranz-Surrallés A (2024) EU geoeconomic power in the clean energy transition. J Common Market Stud 62(4):1028–1045

Johnstone B (2019) Discourse analysis (Introducing Linguistics) (4 edn). Blackwell, Oxford

Jones R (2016) Spoken discourse. Bloomsbury Academic, London

Judge A, Maltby T (2017) European energy union? Caught between securitisation and “Riskification. Eur J Int Security 2(2):179–202. https://doi.org/10.1017/eis.2017.3

Kacperska E, Łukasiewicz K, Pietrzak P (2021) Use of renewable energy sources in the European Union and the Visegrad Group countries—Results of cluster analysis. Energies 14(18):5680. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14185680

Knodt M, Ringel M (2022) European Union energy policy: a discourse perspective. In: Handbook of energy governance in Europe. Springer International Publishing, Cham. pp. 121–142

Kratochvil P, Mišík M (2020) Bad external actors and good nuclear energy: media discourse on energy supplies in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Energy Policy 136:111058

Krzyżanowski M (2015) International leadership re-/constructed? Ambivalence and heterogeneity of identity discourses in European Union’s policy on climate change. J Lang Polit 14(1):110–133. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.14.1.06krz

Krzyżanowski M (2019) Brexit and the imaginary of ‘crisis’: a discourse conceptual analysis of European news media. Crit Discourse Stud 16(4):465–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2019.1592001

Lövin I (2019) Klimatforhandlingarna pa fns klimatmote cop 25 ar avslutade (The climate negotiations at the UN climate convention COP 25 have ended). https://www.regeringen.se/pressmeddelanden/2019/12/klimatforhandlingarna-pa-fns-klimatmote-cop-25-ar-avslutade/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Machin A (2019) Changing the story? The discourse of ecological modernisation in the European Union. Environ Polit 28(2):208–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1549780

Maltby T (2013) European Union energy policy integration: a case of European Commission policy entrepreneurship and increasing supranationalism. Energy Policy 55:435–444

Meyer T (2024) Mapping energy geopolitics in Europe: journalistic cartography and energy securitisation After the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Geopolitics 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2024.2362668

Ministry of Industry and Trade (2021a) Jádro a dočasně i plyn je třeba v kontextu s přechodem na zelenou ekonomiku považovat za udržitelné zdroje energie, pomůžou s cenami (In the context of the transition to a green economy, nuclear and temporarily gas should be considered as sustainable energy sources, they will help with prices). https://www.mpo.cz/cz/rozcestnik/pro-media/tiskove-zpravy/jadro-a-docasne-i-plyn-je-treba-v-kontextu-s-prechodem-na-zelenou-ekonomiku-povazovat-za-udrzitelne-zdroje-energie--pomuzou-s-cenami--264794/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Ministry of Industry and Trade (2021b) Nejen gigafactory může pomoci automobilovému průmyslu v České republice (Not only the gigafactory can help the automotive industry in the Czech Republic). https://www.mpo.cz/cz/rozcestnik/pro-media/tiskove-zpravy/nejen-gigafactory-muze-pomoci-automobilovemu-prumyslu-v-ceske-republice---263905/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Ministry of Industry and Trade (2021c) Fit for 55: Ministři pro energetiku řešili novou energetickou legislativu a rostoucí ceny energií v EU (Fit for 55: Energy ministers discussed new energy legislation and rising energy prices in the EU). https://www.mpo.cz/cz/energetika/mezinarodni-spoluprace/evropska-energeticka-politika/fit-for-55-ministri-pro-energetiku-resili-novou-energetickou-legislativu-a-rostouci-ceny-energii-v-eu--263609/ (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Ministry of the Environment (2022a) Balíček Fit for 55 může přispět ke snížení závislosti na ruské ropě a plynu (The Fit for 55 package can help reduce dependence on Russian oil and gas). https://www.mzp.cz/cz/news_20220317-Balicek-Fit-for-55-muze-prispet-ke-snizeni-zavislosti-na-ruske-rope-a-plyn (accessed 15 October 2023)

Ministry of the Environment (2022b) Vláda představila základní priority českého předsednictví Evropské unie. Zelená energetika k nim patří (The government presented the basic priorities of the Czech presidency of the European Union. Green energy is one of them). https://www.mzp.cz/cz/news_20220515_Vlada_predstavila_zakladni_priority_ceskeho_predsednictvi_Evropske_unie (accessed 15 Oct 2023)

Molek-Kozakowska K (2024) The hybrid discourse of the ‘European Green Deal’: road-mapping economic transition to environmental sustainability (almost) seamlessly. Crit Discourse Stud 21(2):182–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2023.2197607

Moravcsik A (1993) Preferences and power in the European Community: a liberal intergovernmentalist approach. J Common Mark Stud 31(4):473–524. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.1993.tb00477.x

Moravcsik A (2002) Reassessing legitimacy in the European Union. J Common Mark Stud 40(4):603–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00390

Niskanen J, Anshelm J, Haikola S (2024) A multi-level discourse analysis of Swedish wind power resistance, 2009–2022. Political Geogr 108:103017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.103017

Ossewaarde M, Ossewaarde-Lowtoo R (2020) The EU’s Green deal: a third alternative to green growth and degrowth? Sustainability 12(23):9825. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12239825

Patton MQ (2002) Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Reisigl M (2014) Argumentation analysis and the discourse-historical approach. a methodological framework. In: Hart, Ch., Cap, P. (eds). Contemporary critical discourse studies. Bloomsbury, London

Reisigl M (2017) The discourse-historic approach. In: Flowerdew J, Richardson JE (eds). Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies. Routledge, London

Reisigl M, Wodak R (2009) The discourse-historical approach (DHA). In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds). Methods for critical discourse analysis (2nd revised edn). Sage, London

Rheindorf M (2022) The discourse-historical approach: methodological innovation and triangulation. In: Wodak R, Rheindorf M (eds). Identity politics past and present. University of Exeter Press, Exeter

Schlacke S, Wentzien H, Thierjung EM, Köster M (2022) Implementing the EU Climate Law via the ‘Fit for 55’ package. Oxford Open Energy. 1. https://doi.org/10.1093/ooenergy/oiab002

Schunz S (2022) The ‘European Green Deal’—a paradigm shift? Transformations in the European Union’s sustainability meta-discourse. Polit Res Exchange. 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2022.2085121

Siddi M (2016) The European Green Deal: assessing its current state and future implementation. The Finnish Institute of International Affairs, Helsinki. www.fiia.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/wp114_european-green-deal.pdf (accessed on 15 Feb 2023)

Siddi M (2018) Identities and vulnerabilities: the Ukraine crisis and the securitisation of the EU-Russia gas trade. Energy security in Europe: Divergent perceptions and policy challenges. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. pp. 251–273

Siddi M (2020a) Theorising conflict and cooperation in EU-Russia energy relations: ideas, identities and material factors in the Nord Stream 2 Debate. East Eur Polit 36(4):544–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2019.1700955

Siddi M (2020b) European identities and foreign policy discourses on Russia: from the Ukraine to the Syrian Crisis. Routledge, London and New York

Siddi M, Kustova S (2021) From a liberal to a strategic actor: the evolution of the EU’s approach to international energy governance. J Eur Public Policy 28(7):1076–1094. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1918219

Siddi M, Prandin F (2023) Governing the EU’s energy crisis: the European Commission’s geopolitical turn and its pitfalls. Polit Gov 11(4):286–296

Simmerl G (2011) Critical constructivist perspective on global multi-level governance. Discursive struggles among multiple actors in a globalized political space. Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin

Simpson P, Mayr A, Statham S (2019) Language and power (2nd edn.). Routledge, London and New York

Skjærseth JB (2017) The European Commission’s shifting climate leadership. Glob Environ Polit 17(2):84–104

Solorio I, Jörgens H (2020) Contested energy transition? Europeanization and authority turns in EU renewable energy policy. J Eur Integr 42(1):77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1708342

Sperling J, Webber M (2019) The European Union: security governance and collective securitization. West Eur Politics 42(2):228–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1510193

Strandhäll A (2022) EU-länder eniga om stopp för nya fossilbilar (EU countries agree to stop new fossil fuel cars). https://www.gp.se/nyheter/v%C3%A4rlden/eu-l%C3%A4nder-eniga-om-stopp-f%C3%B6r-nya-fossilbilar-1.75854631 (accessed 15 October 2023)

Strunz S, Gawel E, Lehmann P (2015) Towards a general “Europeanization” of EU Member States’ energy policies? Econ Energy Environ Policy 4(2):143–160

Szulecki K (ed.) (2018) Energy security in Europe. Divergent perceptions and policy challenges. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Tews K (2015) Europeanization of energy and climate policy: the struggle between competing ideas of coordinating energy transitions. J Environ Dev 24(3):267–291

Tichý L (2019) EU-Russia energy relations: a discursive approach. Springer, Cham

Tichý L, Dubský Z (2020) Russian energy discourse on the V4 countries. Energy Policy 137:111128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111128

von Malmborg F (2023) First and last and always: politics of the ‘energy efficiency first’principle in EU energy and climate policy. Energy Res Soc Sci 101:103126

Wang G, Huan C (2023) Negotiating climate change in public discourse: insights from critical discourse studies. Crit Discourse Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2023.2198725

Wodak R (2015) Critical discourse analysis, discourse-historical approach. The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118611463.wbielsi116

Wodak R (2020) Analysing the politics of denial: critical discourse studies and the discourse-historical approach. In: Discourses in action. Routledge. pp. 19–36

Wodak R, Krzyżanowski M (2008) Qualitative discourse analysis in the social sciences. Basingstoke. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Wurzel RKW, Liefferink D, Di Lullo M (2019) The European Council, the Council and the Member States: changing environmental leadership dynamics in the European Union. Environ Polit 28(2):248–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1549783

Zehfuss M (2002) Constructivism in international relations: the politics of reality. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Funding