Abstract

Using a panel dataset of 24,527 farming households from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) for the years 2014–2020, this study employed the fixed-effects, mediation-effect, and two-stage least squares (2SLS) models to explore why in the context of non-agricultural employment Chinese farmers are reluctant to lease out their land from an agricultural mechanization perspective. The analysis yielded several significant findings. First, participation in non-agricultural employment significantly increases the likelihood of farmers leasing out their land. Second, remittances do not significantly impact the increase in agricultural machinery procurement investments but increase expenditures on agricultural machinery leasing. Third, both pathways of agricultural mechanization—self-purchased machinery and machinery leasing—significantly inhibit farmers from leasing out land, indicating a negative mediating effect of agricultural mechanization on the impact of non-agricultural employment on land leasing. Fourth, a complementary rather than a substitutive effect exists between self-purchased and leased agricultural machinery. Collectively, the findings suggest that the government should increase agricultural machinery subsidies to advance the process of agricultural mechanization in China, which plays a crucial compensatory role in the loss of rural labor. Furthermore, improving the wages, benefits, and employment stability of migrant workers is significantly conducive to promoting and stabilizing land transfers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Following the reform and opening-up policy, China has experienced rapid development. The surge in urban wages has drawn numerous rural surplus laborers to cities searching for non-agricultural employment, leading to several “migrant worker waves.” By the end of 2021, China’s total pastoral migrant worker population had reached 293 million, with the majority (58.71%) seeking employment outside their prefecture-level cities in other cities or provinces (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China (NBS), 2022). This migration signifies a shift from agricultural to non-agricultural and urban sectors, resulting in a decreased number of rural laborers and a transformation in their demographic composition, characterized by aging and an increase in female laborers (Ji et al. 2017; Xie and Lu, 2017; Ma et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019). The gender distribution of rural migrant workers in 2021 was 64.1% male workers and 35.9% female workers. Age-wise, 61.8% of workers were under 50 and 38.2% over 50 (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China (NBS), 2022).

Amid the declining quantity and quality of agricultural labor, concerns about who will cultivate the fields in the future have emerged alongside China’s rapid economic expansion (Liu and Zhou, 2021). On one front, the dual challenges of agricultural labor loss and the increased opportunity cost of farming have led many farmers to transfer their contracted land. The Chinese government has enacted policies to promote and stabilize the rural land transfer process, such as the “Opinions on Guiding the Healthy Development of the Rural Property Rights Transfer and Trading Market” in 2014, which standardized the rural land property rights transfer and transaction market across China (General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (GOSC), 2014).

In 2016, the “Opinions on Perfecting the Separation of Ownership Rights, Contract Rights, and Management Rights of Rural Land” introduced a division of farmers’ land contract management rights into contract rights and management rights. By so doing, it implemented a system wherein ownership rights, contract rights, and management rights are separated and operate in parallel (General Office of the CPC Central Committee GOCCC, General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (GOSC), 2016). This initiative represented another significant innovation in China’s rural reforms. The Three Property Rights Separation (TPRS) reform legalized farmland transfer practices in rural China, stimulating the national farmland transfer market (Han et al. 2023). These initiatives have provided an institutional guarantee for protecting farmers’ land rights and accelerating land transfer.

Since 2000, the scale of land transfer in rural China has expanded continuously. In 2021, the transferred land area accounted for 31.38% of the total, enabling the formation of numerous large-scale business entities through land transfer (Policy and Reform Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (PRD), 2022). Concurrently, the past 40 years have witnessed significant advancements in China’s agricultural mechanization, which offers essential technical support to address the challenges posed by the loss of agricultural labor. Many farmers remain engaged in agriculture despite migrating family labor to non-agricultural sectors.

The Chinese government has enacted policies to elevate agricultural mechanization, such as the “Agricultural Mechanization Promotion Law of the People’s Republic of China.” This law mandates that central and provincial financial authorities allocate special funds to subsidize farmers and agricultural production and operation organizations to purchase advanced and suitable agricultural machinery supported and promoted by the state. Concurrently, governments at all levels are required to encourage and support the development of agricultural machinery service organizations, advance the construction of an agricultural mechanization information network, and improve the agricultural mechanization service system (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (MARA), 2018). In 2021, the comprehensive mechanization rate for crop cultivation and harvesting in China reached 72.03% (Agricultural Mechanization Management Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (AMMD), 2022).

In 2021, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China issued the “Management Measures for the Transfer of Rural Land Operation Rights,” which proposes that the land transfer scale should align with the urbanization process, rural labor force migration, and improvement in the level of agricultural socialization services. This approach aims to ensure that land transfer practices support the broader goals of sustainable rural development and agricultural modernization and harmonize with demographic and economic changes in rural areas (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (MARA), 2021). Consequently, critical inquiries have arisen regarding the interplay among non-agricultural employment, agricultural mechanization, and land transfer within rural China.

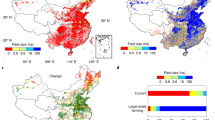

Mainstream research indicates that the intensification of non-agricultural employment in China leads farmers to transfer their land (Kung, 2002; Huang et al. 2012). Yet the current study observed that despite a significant increase in the total land transfer area in China, the pace of land transfer has not kept pace with the migration of the rural labor force. From 2014 to 2021, the proportion of land transfer area increased by only 3.21%. In 2021, the land transfer area constituted 31.38% of the total, while the proportion of Chinese migrant workers was 50.75% of the rural labor force during the same period (Fig. 1). This discrepancy suggests that agriculture remains a crucial livelihood for Chinese rural families, influencing farmers to retain their land. Additionally, the internal division of labor within families and the capital-for-labor substitution effect imply that farmers may not necessarily transfer their land, even when engaging in non-agricultural employment (Wang et al. 2016a; Li et al. 2021).

Farmers in China simultaneously engage in non-agricultural employment and agricultural production for several reasons. First, in China, land serves a distinct role as social security, discouraging farmers from transferring it (Wang et al. 2013, 2020b; Huang et al. 2021). Farmers rely on the economic stability provided by land to mitigate the uncertain risks associated with non-agricultural employment (Eakin, 2005). From the farmers’ viewpoint, agriculture is crucial to ensuring family food security, as relying on market purchases for food significantly diminishes their ability to afford other essentials (Van der Ploeg and Ye, 2010). Non-agricultural employment is often seen as complementing agricultural stability rather than an exit strategy from farming (Kimhi, 2000).

Second, China’s rural labor force exhibits a non-migration flow pattern. Rural migrant workers frequently oscillate between urban and rural areas, establishing a part-time farming model characterized by men working outside the home, while women look after farms at home. Moreover, younger, able-bodied workers go out to work, and the elderly remain at home to farm (Li and Sicular, 2013; Liu et al. 2019). This migration is seasonal, with workers returning to agriculture during peak seasons and pursuing other jobs in the off-season (Van der Ploeg and Ye, 2010). Finally, the rural labor force’s engagement in non-agricultural activities inevitably influences the allocation of agricultural production factors and management practices (Zhong et al. 2016). Labor and land, being crucial for agricultural production, require a reconfiguration due to the migration of surplus rural labor, leading to changes in land management (Li and Wang, 2004). This migration results in increased real wages, potentially spurring technological advancements. Farmers are thus motivated to substitute labor with capital, deepening their investment in agricultural production (Van den Berg et al. 2007; Ito and Ni, 2013).

The rapid advancement in China’s agricultural mechanization over the past 40 years illustrates this shift from labor to capital. The total power of China’s agricultural machinery increased from 117 million kilowatts in 1978 to 1.056 billion in 2020 (CAMIA, 2022). Regions with higher non-agricultural employment levels generally show more advanced agricultural mechanization (Li et al. 2021). Despite a decline in the importance of agricultural income, farmers seek technological solutions to supplement or replace agricultural labor, continuing to secure food from their farms and manage potential unemployment risks. The progress in agricultural mechanization enables farmers to maintain agricultural production alongside non-agricultural employment without transferring their land.

The internal and external dynamics of China’s agricultural development are rapidly evolving, with land transfer emerging as a critical method to address land fragmentation and modernization challenges (Chen et al. 2010). Understanding why Chinese farmers hesitate to transfer their land is of significant theoretical and practical importance. Although non-agricultural employment may prompt land transfer, agriculture remains essential for household livelihoods, mainly due to the instability of non-agricultural jobs. Consequently, farmers may prefer a part-time farming model, slowing land transfer rates. Moreover, the advancement of agricultural mechanization, supported by remittances from non-agricultural employment, has been crucial in replacing agricultural labor. This dynamic is a key reason farmers can sustain or enhance agricultural production post-migration, reducing the urgency to transfer land.

The existing literature offers valuable theoretical insights for this article, yet specific gaps must still be filled. One source of these gaps is that most studies rely on indicators such as “participation in non-agricultural employment,” “proportion of the non-agricultural labor force,” or “proportion of household non-agricultural income” to gauge the extent of farmers’ non-agricultural employment (Liu, 2017; Wang et al. 2020a; Zheng et al. 2021). This approach may introduce bias and overestimate the influence of non-agricultural employment on rural household decisions, as non-agricultural employment does not invariably result in remittances to rural areas (Mobrand, 2012). Although some households may have higher non-agricultural income statistically, laborers who migrate to cities might not remit significant portions of their income to their rural homes, often due to the high cost of living in urban areas and personal development needs. Consequently, the rural elderly, women, and other “left-behind” populations may not fully benefit from non-agricultural employment benefits gains. Moreover, a reduction in agricultural labor force within families due to participation in non-agricultural employment leads to a “labor force loss” effect, potentially diminishing the welfare impact of non-agricultural employment on farmers’ households and reinforcing the land’s security for these households.

Another source of these gaps is that most existing research on agricultural mechanization in China primarily focuses on agricultural machinery leasing or socialized services as indicators of mechanization levels (Liu et al. 2022; Yang and Li, 2022). However, these studies frequently overlook households’ direct purchases of agricultural machinery, which diverge from the actual circumstances in rural China. The current study found that increased remittances from non-agricultural employment enable non-migrant family members to afford small-scale agricultural machinery for modest land operations or opt to lease machinery. Consequently, these family members can maintain agricultural output with reduced labor, ensuring that retaining their land does not compromise household welfare.

Employing data from 24,527 rural households obtained from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) database from 2014 to 2020, this study conducted an empirical analysis of the impact of non-agricultural employment on land transfer. It used the mediation model and two-stage least squares (2SLS) model to explore the mediating role of agricultural mechanization between non-agricultural employment and land transfer. Additionally, this research explored whether a substitution or complementary effect exists between self-purchase and leasing of agricultural machinery in terms of their impact on land transfer, aiming to unravel the reasons behind Chinese farmers’ reluctance to transfer their land.

With its innovative design and analysis, this study makes several notable contributions. First, it used remittances to indicate the level of non-agricultural employment, which may have helped mitigate estimation biases. Second, it broadened the understanding of agricultural mechanization by considering the self-purchase and leasing of agricultural machinery. Third, the study investigated whether a substitution or complementary effect exists between self-purchasing and leasing of agricultural machinery in influencing land transfer, aiming to uncover why Chinese farmers are reluctant to transfer their land. In summary, this article contributes to the literature by using remittances as an indicator of non-agricultural employment level, thereby reducing estimation biases; expands the understanding of agricultural mechanization to include self-purchase and leasing of machinery; and examines the potential substitution or complementary relationship between these two mechanization approaches on land transfer.

Theoretical framework

The theory of change supports the analytical framework constructed in this study. Delineating a linear pathway of causality clarifies the essential logic connecting inputs, outputs, and outcomes, facilitating the establishment of a clear evaluative framework (James, 2011). Farmer engagement in non-agricultural sectors induces two primary shifts in households: a depletion of the agricultural labor force and an increase in non-agricultural income. The diminution of agricultural labor might compel households to employ technological advancements to boost productivity, ensuring the continued viability of farming activities. Furthermore, a rise in non-agricultural income or remittances alters the structure of household livelihoods, reducing the relative importance of agriculture, enhancing the ability of households to adopt new technologies, and easing financial constraints. Thus, although non-agricultural employment promotes a tendency among farmers to relinquish land, this effect can be eased if remittances are used to enhance agricultural mechanization. Figure 2 displays the theory of change that explains how non-agricultural employment influences land tenure transitions.

Since the reform and opening-up, the shift of the rural labor force from agricultural to non-agricultural employment has profoundly influenced the livelihoods of farming households in China. The level and proportion of non-agricultural income among Chinese farmers have significantly increased, with remittances from urban areas enhancing living conditions and supporting agricultural development (Taylor et al. 2003; Van der Ploeg and Ye, 2010). Notably, the proportion of remittances sent by Chinese migrant workers is 30–50% of their working income, which is high compared with other countries (Li, 2001, 2019), as corroborated by the CFPS data analyzed in this study.

The growth and stability of non-agricultural income play a crucial role in farmers’ decisions to lease their land (Shao, 2015; Su et al. 2018). However, this influence manifests through two opposing mechanisms: on the one hand, sufficient non-agricultural employment income may reduce agriculture’s role as the primary income source, prompting farmers to lease their land (Gao et al. 2020). On the other hand, despite not relying on land for their primary income, some households still exhibit reluctance to lease it out (Wang and Han, 2020). The stability of non-agricultural employment emerges as a critical factor in facilitating land transfer (Gao et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020a). Yet the household registration system poses challenges for most migrant workers in securing stable employment akin to that of urban residents. Facing unstable employment opportunities, migrant workers and their families often retain their land as a safeguard against urban living uncertainties (Su et al. 2018).

Furthermore, households with higher levels of non-agricultural employment require more agricultural machinery. As labor wages rise, farmers are increasingly likely to substitute labor with machinery in agricultural production (Wang et al. 2016a). Additionally, increased non-agricultural income alleviates financial constraints for farmers, enabling timely labor hiring and procurement of agricultural inputs, thus boosting agricultural productivity (Wouterse, 2010; Davis and Lopez-Carr, 2014; Yang et al. 2020). Nonetheless, the decision to invest economic returns from non-agricultural employment into agricultural activities hinges on the investment return expectations of the households left behind (De Brauw, 2019). Predominantly, remittances from non-agricultural income are used to improve current living conditions, such as housing, rather than investing in agricultural assets (Ming et al. 2014; Qian et al. 2015), with work remittances not significantly leading to an increase in household agricultural production inputs (De Brauw and Rozelle, 2008).

Based on the preceding analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1: Although the instability of non-agricultural employment causes concerns for farmers regarding leasing out their land, the increasing trend of entire families migrating for work, leading to a lack of family members to manage a farm, combined with the rising sufficiency of non-agricultural employment reduces the importance of agriculture in farmers’ livelihoods. Thus, overall, non-agricultural employment facilitates farmers’ transfer of land.

H2: Considering the lower stability and income levels of Chinese farmers’ non-agricultural employment, agriculture remains essential to farmers’ livelihoods. Hence, they are inclined to increase agricultural investments to compensate for the loss of agricultural labor and reduce labor intensity. Remittances provide necessary financial support for farmers to continue managing their land while engaging in non-agricultural work, easing the economic constraints of agricultural investments. Thus, remittances help increase investment in agricultural mechanization.

Agricultural mechanization is a technological substitute for agricultural labor amid non-agricultural employment, enabling farmers to transition to non-agricultural sectors without forsaking agricultural production. It encompasses purchasing agricultural machinery, renting services, and direct procurement of machinery (Ma et al. 2018; Qiu and Luo, 2021; Qian et al. 2022). The decision between purchasing machinery and purchasing services is influenced by production goals and the scale of expansion of farmland management, focusing on cost minimization, risk reduction, and profit maximization (Hu et al. 2019; Qiu and Luo, 2021). The high cost of agricultural machinery presents a significant barrier, especially for small-scale farmers who cannot afford extensive equipment for all production stages. The emergence of socialized agricultural machinery services has mitigated the indivisibility of machinery, enabling small farmers to engage in agricultural production by purchasing services instead of machinery when actual wages increase (Wang et al. 2016b; Deng et al. 2020; Zheng et al. 2021).

These services have played a pivotal role in the rapid advancement of agricultural mechanization in China, particularly under conditions of fragmented land. Agricultural mechanization provides exogenous technical support for Chinese farmers transitioning to cities and non-agricultural sectors, reducing the quantity of agricultural labor input and the intensity of agricultural labor. Rational farmers, considering maximizing family utility, opt to maintain a mixed-occupation household division of labor. Agricultural mechanization, by making farming operations more convenient, encourages farmers to retain land, thus reducing land transfer (Liu, 2016; Qian et al. 2022).

Considering these dynamics, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3: Mixed-occupation farming in China is a management model that relies on agricultural mechanization, characterized by lower labor and higher capital input. Advancements in mechanization effectively supplement the loss of agricultural labor, enabling farmers to maintain agricultural production even while engaging in non-agricultural employment. Therefore, agricultural mechanization has a negative mediating effect on the impact of non-agricultural employment on land transfer, potentially weakening the positive effect of non-agricultural employment on land transfer.

Recent research indicates a substitutive relationship between farmers’ self-purchased agricultural machinery and the utilization of socialized services (Yang et al. 2022). Nonetheless, given that small-scale farmers still predominate in rural China and agriculture remains a crucial income source, most small farmers continue operating their farms and own modest, economically priced machinery. Commonly held machinery includes small tractors, harvesters, and water pumps (Ji et al. 2012; Su et al. 2016). This observation leads some scholars to suggest a complementary relationship between personally owned agricultural machinery and outsourced machinery services (Qian et al. 2022).

The adoption of agricultural mechanization in China displays significant regional variation. Challenging terrain is a critical factor that limits mechanization adoption, as the difficulty posed by terrain diminishes the ease of operating agricultural machinery. Heavy machinery is often impractical in hilly and mountainous regions, increasing the cost of machinery operation and services (Jasinski et al. 2005; Ullah and Anad, 2007). Furthermore, China’s socialized service system for agricultural machinery is unevenly developed. In areas with low levels of marketization, the advancement of socialized agricultural machinery services is sluggish. Without easy access to various capital and technological resources to substitute for labor, farmers cannot reduce labor by increasing capital investments (Yang and Li, 2015). Production stages that cannot be efficiently externalized must be managed internally by households. Thus, to continue farming operations, farmers may find it necessary to purchase some small-scale machinery. When the supply of machinery services falls short of demand, the price of these services can become relatively high, making self-purchase of machinery a cost-effective option for reducing average production costs. Smaller investments in small machinery become more viable for small-scale farmers, making acquiring small agricultural machinery more advantageous (Yang et al. 2013).

Based on this analysis, the study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4: Self-purchased machinery and machinery services, as the two core aspects of agricultural mechanization in China, play complementary rather than substitutive roles in agricultural mechanization. Farmers choose different methods under varying conditions, and both aspects complement each other in the mechanization of agriculture in China.

Methods

Data

This study utilized data from the CFPS database, which was facilitated by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) at Peking University from 2014 to 2020. The CFPS aimed to understand Chinese residents’ economic and non-economic welfare, covering various research themes such as financial activities, educational outcomes, family relationships and dynamics, population migration, and health. As a nationwide, large-scale, multidisciplinary longitudinal survey, the CFPS encompassed 25 provinces, regions, and municipalities across China not including Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Hainan, and the territories of Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, representing approximately 95% of the Chinese population, ensuring a broad national representation. Initiated in 2010, the survey conducted biennial data collection waves in 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020. The CFPS employed a multi-stage, implicitly stratified, and probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling design to ensure a representative and efficient sample. Data collection was primarily conducted through computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI), supplemented by computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) and computer-assisted web interviews (CAWI). For this study, data from 2014 to 2020 were utilized, as the datasets from 2010 and 2012 lacked the core variables of interest.

Data preprocessing involved critical steps to ensure the reliability and relevance of the analysis. First, rural samples were identified based on the variables of urban* (urban2014/urban2016/urban2018/urban2020) in CFPS, which followed classification standards published by the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics. Due to the inclusion of rural and urban household samples in the CFPS database, rural samples were identified based on the urban* variable from the CFPS database spanning 2014 to 2020. The urban variable adheres to the urban–rural classification criteria established by the National Bureau of Statistics of China. An urban variable value of 1 indicates an urban setting, whereas 0 denotes a rural setting. Based on this classification, only rural samples were retained for analysis. Second, samples from separated households were removed. Separated households had been divided into distinct entities, often due to family restructuring, divorce, migration, or other social changes. Data regarding separated households provided by CFPS explain that family members were economically independent from each other. In prior survey waves, these households, although originally part of a single-family unit, had been divided due to events such as the marriages of children. Following separation, these households may have experienced systematic changes that could compromise the integrity of our longitudinal analysis. Third, families who were not allocated land in rural China were excluded. Since the 1980s, although land distribution in farmers’ villages included minimal reserves for population growth, increasing demographic pressures through marriages and births have rendered the available land insufficient for equitable distribution among all rural families. Last, households led by individuals younger than 16 were omitted to enhance the empirical accuracy of the findings.

The sample sizes for the family units considered in this analysis were 7488 in 2014, 6783 in 2016, 6156 in 2018, and 4100 in 2020. The notable reduction in sample size in 2020 can be attributed to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which presented unique challenges in data collection and resulted in a significantly lower sample size in that year’s dataset than in previous years. Among the 24,527 complete samples, 11,072 samples were tracked for four waves, 8283 samples for three waves, 3678 samples for two waves, and 1494 samples for one wave.

Empirical model

This study used the mediation effect model for empirical analysis, which encompassed three main steps: (1) regression of the explanatory variables on the explained variable when the mediation variable was not included, referred to as model 1; (2) regression of the explanatory variables on the mediation variable, referred to as models 2 and 3; and (3) regression of both explanatory variables and intermediary variables on the explained variables, referred to as 4. It is important to note that the dependent variables were binary category variables. However, the linear probability model (LPM) was chosen over the logit/probit model. The rationale was that the LPM model could control various classes of fixed effects, a capability not entirely achievable with the logit/probit model. In causal inference, the ability of a model to adequately control for fixed effects is a primary concern. Utilizing the logit/probit model could have led to skewed estimated coefficients due to unaccounted fixed effects. The specific model formulas are as follows:

where Rent_Outit represents land rented out, Remittanceit represents remittances received by the family, Machine_Valueit represents the value of household self-purchased agricultural machinery, Machine_Rentit represents household agricultural machinery lease expenditure, controls represents control variables, α and β represent the coefficient of variables, μt represents the time fixed effect, ρi represents the individual fixed effect, φc represents the village fixed effect, and ε represents the residual items.

To test whether there is a substitution or complementary effect between household self-purchasing of agricultural machinery and agricultural machinery leasing, this study incorporated an interaction term between these two mediating variables based on model (4). The specific model formulas are as follows:

Here, \({{{\rm {Machine}}\_{\rm {Value}}}}_{{{\rm {it}}}}* {{{\rm {Machine}}\_{\rm {Rent}}}}_{{{\rm {it}}}}\) is the interaction term between self-purchasing of agricultural machinery and agricultural machinery leasing. The interpretation of other variables and coefficients is unchanged. If the coefficient of \({{{\rm {Machine}}\_{\rm {Value}}}}_{{{\rm {it}}}}\) and \({{{\rm {Machine}}\_{\rm {Rent}}}}_{{{\rm {it}}}}\) are both significantly negative and the coefficient of the interaction term is very positive, it suggests that both factors promote the transfer of agricultural land. The marginal effect of one variable increases with the increase of the other, indicating a complementary relationship between the two. Conversely, if the coefficient of the interaction term is significantly negative, it implies that the marginal effect of one variable decreases as the other increases, signifying a substitutive relationship.

Variable selection

This study’s dependent variable was the leasing out of land by farmers in rural China. In this context, although land ownership rests with rural collectives, farmers possess land contracting and operating rights. The study thus focused on the transfer of these operating rights from farmers to other entities, operationalized through a binary categorical variable where leasing out land is coded as 1 and not leasing out is coded as 0, following the approach of Wang et al. (2020a), Xie and Lu (2017), and Gao et al. (2020). The explanatory variable under consideration is the amount of remittance, a proxy for the impact of non-agricultural employment of family members on the remaining rural family’s production and living conditions. The remittance amounts have been subjected to a logarithmic transformation to address the skewness typically associated with remittance data and mitigate the influence of outliers.

Mechanism variables in this study included the value of family-purchased agricultural machinery and family expenditures on agricultural machinery rentals. The former refers to the cumulative value of a household’s agricultural machinery, and the latter pertains to the costs incurred from renting agricultural machinery for farming operations. These intermediary variables have also been logarithmically transformed to facilitate a more nuanced analysis. Control variables were included to account for various household head and family characteristics that may influence the decision to lease out land. Characteristics of the household head such as age, gender, health status, and educational attainment were considered, alongside family characteristics such as the proportion of members with labor contracts, coverage by comprehensive social insurance schemes (often referred to as the “five insurances” in China), out-of-pocket medical expenses, the number of family members consuming meals at home, engagement in individual/private enterprises, the value of self-consumed agricultural products, and overall family size. The study further incorporated time, individual, and village fixed effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity that could have affected the outcomes. A comprehensive definition and descriptive analysis of all variables introduced in this study are presented in Table 1.

From the perspective of land transfer, 17.2% of farming households rent out their land. In terms of non-agricultural employment, 55.5% of households participate in non-agricultural jobs, with an average annual non-agricultural income per household of 18,138.6 CNY, of which ~48.5% (8796.1 CNY) is remitted back to rural households. However, only 16.5% of farmers sign labor contracts with their employers, and the proportion contributing to social insurance is <2%. Regarding agricultural mechanization, the average annual cost of leasing machinery per household is 420.8 CNY, and the average value of machinery per household is 3249.3 CNY.

Results

Basic regression results

This study initially explored the influence of participation in non-agricultural employment and the log-transformed off-farm income on the propensity of rural households to lease out their land. The findings from Models (1) and (2) presented in Table 2 clearly demonstrate that participation in non-agricultural activities and an increase in non-farm income significantly enhance land leasing. This observation is consistent with existing research, affirming the role of non-agricultural employment and non-farm income in facilitating land leasing decisions among rural households. Further analysis was conducted by introducing log-transformed remittances as a substitute explanatory variable. The outcomes of Model (3) emphasize a significantly positive influence of remittances on land leasing, substantiated at a 5% significance level. This result underscores the substantial role of remittances in the mediation model, thereby supporting H1. Moreover, the analysis reveals that the coefficient associated with remittances is smaller than that for non-farm income. A primary reason for this result is that not all non-farm income is remitted back to rural areas, leaving land and agriculture as essential sources of livelihood for family members who remain in the countryside. The remittances that they receive have a significant impact on these left-behind family members.

The endogeneity issue in this study primarily stems from the potential bidirectional causality among variables. To address this, the study employed a 2SLS model and controlled for fixed effects to mitigate the endogeneity problem. The model setup for the first stage was as follows:

In this context, \({S}_{{{{it}}}}\) represented the endogenous explanatory variable, \({X}_{{{{it}}}}\) represented exogenous explanatory variables, and \({Z}_{{{\rm {it}}}}\) represented instrumental variables. The meanings of the coefficients remain unchanged. The average non-farm income of villagers within the same village was used as an instrumental variable for remittances, and similarly, the village’s average investment in agricultural mechanization as an instrumental variable for such investments. This methodology was predicated on the understanding that non-farm income significantly influences remittance levels. In China, village social networks are crucial in securing farmers’ non-agricultural employment. Migrants often assist others from their village in finding employment, leading to similar job types and incomes among villagers. Therefore, a village’s average non-farm income affects individual remittances but does not directly impact decisions to transfer land, meeting the criteria for an instrumental variable.

The results of an endogeneity test confirmed that remittances conform to the endogeneity hypothesis at a 1% significance level. A weak instrumental variable test indicated that the chosen instrumental variables were robust, as evidenced by F/SW F-values exceeding the critical value of 16.38 and significant coefficients at the 1% level in the first stage. Given the equal number of instrumental and endogenous variables, an overidentification test was deemed unnecessary. Model (4) presents the 2SLS estimation results of the impact of remittances on land leasing. The results show that remittances have a significantly positive effect on land leasing at the 1% level, supporting the empirical findings of model (3). However, the coefficients in the 2SLS model are substantially larger than those in the ordinary least squares (OLS) model, indicating that the OLS model underestimates the coefficients due to the oversight of endogeneity issues.

Analysis of mediation and interaction effects

The results shown in Table 3 indicate a significant overall impact of the model. Further analyses were conducted based on the model setup to further examine the mediation effect. Initially, the analysis assessed the impact of remittances on investments in agricultural mechanization, using the rental and purchase of agricultural machinery as mediator variables. Subsequently, the model simultaneously included explanatory, mediator, and dependent variables to examine the mediation effect more comprehensively. Moreover, to explore the dynamics between the two forms of agricultural mechanization investments, an interaction term between agricultural machinery rentals and purchases was introduced, with both variables centered on mitigating multicollinearity concerns. This “mediation model with interaction effects” aimed to identify whether these investments exhibit complementary or substitutive effects on land leasing.

Models (5)–(8) shown in Table 3 initially presented the OLS estimation results. However, the OLS estimates may have been biased due to endogeneity issues, necessitating the use of 2SLS for robust estimation. Models (9)–(12) display the 2SLS model estimation results, upon which subsequent discussions and analyses are based. The results from Model (9) indicate that remittances have a significantly positive impact on agricultural machinery rental at the 5% level. The results from model (10) show that the impact of remittances on agricultural machinery investments is not significant, which is inconsistent with the OLS results. This suggests that remittances contribute to increasing farmers’ investments in agricultural mechanization, but primarily reflect investments in machinery rental. These findings partially support H2, as well as partially corroborate the findings of several studies that suggest remittances are not necessarily utilized to increase investments in agricultural fixed assets but are primarily allocated to improving household living conditions or savings (Ming et al. 2014; Qian et al. 2015). The results from Model (11) show that both machinery rentals and purchases have a significantly negative effect on land leasing, indicating that higher levels of agricultural mechanization may deter farmers from leasing out their land. This suggests that agricultural mechanization mediates the relationship between remittances and land leasing, tempering the facilitating effect of remittances on land transfer. These results support H3. The results of Model (12), in which an interaction term was included between machinery rentals and purchases, indicate that adding the interaction term did not significantly alter the core explanatory variable’s coefficient and significance. The interaction term was significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating a complementary relationship between machinery rentals and purchases. Given that both negatively impact land leasing, their complementary interaction further amplified this inhibitory effect on the propensity to lease land. Consequently, this analysis supported H4.

In 2014, China’s land transfer process hit a bottleneck from which it has yet to recover, highlighting flaws in the social security system. The uncertain income sources for rural laborers moving to cities and the absence of a unified social security system that bridges urban and rural divides underscores why land remains crucial for social protection in rural China, slowing the pace of land transfers. Decisions regarding non-agricultural employment or land transfer are often made at the family level rather than by individuals. The familiar “mixed-occupation” model in China further illustrates that having family members work non-agricultural jobs does not automatically lead to land being leased out. As non-agricultural employment and agricultural mechanization increase, the expected increase in land transfer has not materialized.

Heterogeneity analysis comparing older and younger generations

The older generation exhibits a more profound attachment to rural areas and land than the younger migrant workers. As they age, they are more likely to return to rural life, viewing agriculture as an essential livelihood for their families. Conversely, the younger generation is less inclined toward agricultural operations and retaining land, marking a clear distinction between the two cohorts. Generally, migrant workers born before 1980 are classified as the older generation and those born after 1980 as the younger generation. Thus, this study used 1980 as a temporal marker, categorizing heads of households into “younger” and “older” generations based on their birth dates (before or after 1980) to conduct heterogeneity robustness tests. This categorization was pivotal in understanding the nuanced differences in how each group views agriculture and land retention.

Compared to the LPM, the 2SLS model, which accounts for endogeneity, offers robust estimates and was thus used for the estimation. The findings shown in Table 4 reveal that for the older generation, remittances significantly aid in leasing out land and bolstering expenditures on agricultural mechanization, suggesting a continued investment in agricultural productivity. However, the effect of remittances on the direct purchase of agricultural machinery remains insignificant, indicating a nuanced approach to investment in agricultural assets. Conversely, the younger generation exhibits a negligible response to remittances in terms of land leasing. This reflects a broader trend among younger migrant workers, who favor urban living and employment, showing a lower propensity to return to rural farming. This group’s use of remittances does not significantly tend toward enhancing agricultural investments, implying that their land leasing decisions remain primarily unaffected by remittance inflows.

Heterogeneity analysis of regional differences

Due to regional characteristics that may lead to different impacts across areas, this study conducted a heterogeneity analysis by dividing the total sample into three sub-samples based on region—the eastern, central, and western regions—to explore regional differences in the impact of remittances. The findings, detailed in Table 5, reflect the varying influences of remittances on land leasing and agricultural mechanization across these regions, influenced by their distinct socioeconomic and geographical characteristics.

In eastern China, known for its developed economy and high urbanization levels, an increase in remittances significantly supports both land leasing and the purchase of agricultural machinery. The insignificance of remittances in leasing agricultural machinery might be attributed to the region’s urbanization, which facilitates the aggregation of larger, contiguous land plots. Here the remittance boost effectively eases financial constraints, making agricultural machinery a more viable and economically sensible option over the long term than leasing. The government should therefore consider bolstering subsidies for machinery purchases to lower acquisition costs, thereby facilitating mechanization progress.

Conversely, in central China, although remittances significantly impact land leasing and, to a lesser extent, the purchase of agricultural machinery, they notably influence the leasing of agricultural machinery. This region, characterized by lower incomes and dependence on agricultural livelihoods, sees remittances not as a direct enabler for land leasing but as a means to enhance agricultural mechanization by leasing machinery. This approach allows farmers to maintain their agricultural operations without substantial investments in machinery ownership. Therefore, the government should respect the farmers’ wishes and not force them to transfer land. At the same time, improving the agricultural social service system is necessary to provide better support for this region’s agricultural production.

In western China, the increase in remittances is positively associated with land leasing, yet its effect on agricultural mechanization remains minimal. The challenging natural environment, marked by less arable land and difficult geographical conditions, reduces the efficiency of agricultural machinery. Consequently, in western China, remittances may lead farmers to opt out of agricultural production rather than invest further in farm inputs.

Conclusions and implications

This study utilized data from the CFPS from 2014 to 2020 to investigate how non-agricultural employment among farmers affects their likelihood of leasing out their land and the role of agricultural mechanization in this dynamic. The empirical results reveal several key findings. First, non-agricultural employment and remittances significantly facilitate land transfer. Second, increasing remittances promotes investment in agricultural mechanization, primarily through leasing machinery. Third, higher levels of agricultural mechanization impede land leasing. Fourth, agricultural mechanization, leasing machinery, and purchasing mechanisms have a complementary rather than substitutive relationship with land leasing. Finally, the impact of remittances on land transfer and agricultural mechanization exhibits generational and regional variations. Based on these findings, several recommendations can be proposed.

Analysis has confirmed that farmers engaged in non-agricultural occupations are increasingly likely to lease their land due to the declining importance of agriculture. Nevertheless, land continues to hold substantial value for these farmers. Consequently, increased remittances also provide technical support for farmers to sustain their agricultural operations through mechanization. This situation highlights the importance of developing government policies sensitive to local environments before promoting land transfers and scaling agricultural operations. Relying on land transfer rates as a metric for evaluating local government performance may be inappropriate, as this should more fully respect farmers’ choices. The government should work to narrow the gap in social security between rural migrants and urban residents, improving the conditions for non-agricultural employment of migrants. These measures would bolster urbanization efforts and facilitate smoother land transitions in rural areas.

Our research further found that machinery leasing and purchasing are complementary in the mechanization process of Chinese agriculture, with remittances having a more pronounced impact on leasing than purchasing. However, rising prices drive small farmers away from agricultural social services (Qiu et al., 2021). Therefore, we propose an increase in government subsidies for agricultural machinery. Supporting the purchase of large and medium-sized equipment can enhance service providers’ willingness to invest, strengthening the agricultural social service system and promoting national mechanization. Subsidizing the purchase of small machinery can reduce acquisition costs for farmers, bridge gaps in agricultural social services, and significantly advance the mechanization of agriculture in China.

Finally, identifying different types of farmers and formulating targeted policies for other regions is crucial for effectively adjusting the land transfer process. This approach ensures that policies more closely align with farmers’ actual needs and regional characteristics, thereby promoting the efficiency and fairness of land use. By conducting an in-depth analysis of farmers’ agricultural characteristics and actual conditions in different regions, the government can implement more effective policies, thus achieving more efficient land resource allocation.

Data availability

Due to restrictions stipulated in the CFPS data usage agreement (https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/cjwt/fbxg/1379024.htm), we are not authorized to share the raw or processed datasets on external websites. However, the original CFPS data are publicly available at the CFPS official website (https://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/). To facilitate reproducibility, the processed datasets used in this study have been uploaded to the CFPS official platform and can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/TZ43PV.

References

Agricultural Mechanization Management Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (AMMD) (2022) National Agricultural Mechanization Development Statistical Bulletin 2021. http://www.njhs.moa.gov.cn/nyjxhqk/202208/t20220817_6407161.htm. Accessed 3 Oct 2024

Chen MQ, Zhong TY, Zhou BJ, Huang HS, He WJ (2010) Empirical research on farm households’ attitude and behavior for cultivated land transferring and its influencing factors in China. Agr Econ 56(9):409–420. https://doi.org/10.17221/93/2009-AGRICECON

China Agricultural Machinery Industry Association (CAMIA) (2022) China Agricultural Machinery Industry Yearbook 2021. China Agricultural Machinery Industry Yearbook Editorial Department, Beijing

Davis J, Lopez-Carr D (2014) Migration, remittances and smallholder decision-making: implications for land use and livelihood change in Central America. Land Use Policy 36:319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.09.001

De Brauw A (2019) Migration out of rural areas and implications for rural livelihoods. Annu Rev Resour Econ 11:461–481. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-100518-093906

De Brauw A, Rozelle S (2008) Migration and household investment in rural China. China Econ Rev 19(2):320–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2006.10.004

Deng X, Xu DD, Zeng M, Qi YB (2020) Does outsourcing affect the agricultural productivity of farmer households? Evidence from China. China Agric Econ Rev 12(4):673–688. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-12-2018-0236

Eakin H (2005) Institutional change, climate risk, and rural vulnerability: cases from Central Mexico. World Dev 33(11):1923–1938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.06.005

Gao J, Song G, Sun XQ (2020) Does labor migration affect rural land transfer? Evidence from China. Land Use Policy 99:105096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105096

General Office of the CPC Central Committee (GOCCC), General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (GOSC) (2016) Opinions on perfecting the separation of ownership rights, contract rights, and management rights of rural land. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/30/content_5126200.htm. Accessed 3 Oct 2024

General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (GOSC) (2014) Opinions on guiding the healthy development of the Rural Property Rights transfer and trading market. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2015/content_2814791.htm. Accessed 3 Oct 2024

Han W, Zhang Z, Zhang X (2023) The impact of farmland transfer participation on farmers’ livelihood choices—an empirical study of the effectiveness of the 2014 Three Property Rights Separation reform. China Agric Econ Rev 15(3):534–562. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-12-2021-0236

Hu W, Zhang JH, Chen ZJ (2019) Small farmer and large-scale production: farmland scale and agricultural capital deepening—taking agricultural machinery operation service as an example. J Agrotech Econ 6:82–96. https://doi.org/10.13246/j.cnki.jae.2020.03.001. in Chinese

Huang JK, Gao LL, Rozelle S (2012) The effect of off‐farm employment on the decisions of households to rent out and rent in cultivated land in China. China Agric Econ Rev 4(1):5–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/17561371211196748

Huang JQ, Antonides G, Christian HK, Nie FY (2021) Mental accounting and consumption of self-produced food. J Integr Agr 20(9):2569–2580. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2095-3119(20)63585-7

Ito J, Ni J (2013) Capital deepening, land use policy, and self-sufficiency in China’s grain sector. China Econ Rev 24:95–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2012.11.003

James C (2011) Theory of change review. Comic Relief, 835 pp

Jasinski E, Morton D, DeFries R, Shimabukuro Y, Anderson L, Hansen M (2005) Physical landscape correlates of the expansion of mechanized agriculture in Mato Grosso, Brazil. Earth Interact 9(16):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1175/EI143.1

Ji YQ, Hu XZ, Zhu J, Zhong FN (2017) Demographic change and its impact on farmers’ field production decisions. China Econ Rev 43:64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.01.006

Ji YQ, Yu XH, Zhong FN (2012) Machinery investment decision and off-farm employment in rural China. China Econ Rev 1:71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2011.08.001

Kimhi A (2000) Is part‐time farming really a step in the way out of agricultural? Am J Agric Econ 1:38–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/0002-9092.00004

Kung JK (2002) Off-farm labor markets and the emergence of land rental markets in rural China. J Comp Econ 2:395–414. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcec.2002.1780

Li F, Feng SY, Lu HL, D’Haese M (2021) How do non-farm employment and agricultural mechanization impact large-scale farming? A spatial panel data analysis from Jiangsu province, China. Land Use Policy 107:105517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105517

Li M, Sicular T (2013) Aging of the labor force and technical efficiency in crop production: evidence from Liaoning province, China. China Agric Econ Rev 3:342–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/caer-01-2012-0001

Li Q (2001) A study on Chinese migrant workers and their remittance. Sociol Stud 4:64–76. in Chinese

Li XC (2019) An analysis of the impact of migrant workers’ remittances on employment and welfare. Frontiers 10:40–47. (in Chinese)

Li XE, Wang CY (2004) Comparison of foreign rural surplus labor transfer models. Chin Rural Econ 5:69–75. (in Chinese)

Liu JC, Xu ZG, Zheng QF, Hua L (2019) Is the feminization of labor harmful to agricultural production? The decision-making and production control perspective. J Integr Agric 18(6):1392–1401. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2095-3119(19)62649-3

Liu LL (2017) Non-farm income, labor transfer and planting structure adjustment. Econ Probl 3:66–69. (in Chinese)

Liu TS (2016) Agricultural mechanization, nonfarm work, and farmers’ willingness to abdicate contracted land. China Popul Resour Environ 6:62–68. (in Chinese)

Liu Y, Ma XL, Shi XP (2022) The effect of agricultural machinery services on the “involution” of smallholders’ land rental. J Huazhong Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 2:146–157. (in Chinese)

Liu YS, Zhou Y (2021) Reflections on China’s food security and land use policy under rapid urbanization. Land Use Policy 109:105699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105699

Ma W, Renwick A, Grafton Q (2018) Farm machinery use, off‐farm employment and farm performance in China. Aust J Agric Resour Ec 2:279–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8489.12249

Ming J, Zeng X (2014) Rural labor force migrant work and hometown housing investment behavior—based on the Guangdong Provincial survey. Chin J Popul Sci 4:110-120+128. (in Chinese)

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (MARA) (2018) The Agricultural Mechanization Promotion Law of the People’s Republic of China. http://www.fgs.moa.gov.cn/flfg/202007/t20200716_6348748.htm. Accessed 3 Oct 2024

Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (MARA) (2021) Management measures for the transfer of Rural Land Operation Rights. https://www.moa.gov.cn/govpublic/zcggs/202102/t20210203_6361060.htm. Accessed 3 Oct 2024

Mobrand E (2012) Reverse remittances: internal migration and rural-to-urban remittances in industrialising South Korea. J Ethn Migr Stud 3:389–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2012.658544

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China (NBS) (2022) Monitoring and investigation of migrant workers report 2021. https://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sjfb/zxfb2020/202204/t20220429_1830139.html. Accessed 3 Oct 2024

Policy and Reform Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (PRD) (2022) Annual statistical report of China’s Rural Policy and Reform 2021. China Agriculture Press, Beijing

Qian L, Lu H, Gao Q, Lu HL (2022) Household-owned farm machinery vs. outsourced machinery services: the impact of agricultural mechanization on the land leasing behavior of relatively large-scale farmers in China. Land Use Policy 115:106008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106008

Qian WR, Li BZ, Zheng LY (2015) The impact of non-agricultural employment on farmland transfer and investment in agricultural assets: evidence from China 2015 Conference, August 9–14, Milan, Italy. International Association of Agricultural Economists

Qiu TW, Choy STB, Li YF, Luo BL, Li J (2021) Farmers’ exit from land operation in rural China: does the price of agricultural mechanization services Matter? China World Econ 2:99–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12372

Qiu TW, Luo BL (2021) Do small farms prefer agricultural mechanization services? Evidence from wheat production in China. Appl Econ 26:2962–2973

Shao S (2015) Study on the relationship between the industrial & commercial capital and land circulation: based on employment and security perspective. China Agric Univ J Soc Sci Ed 6:111–118. in Chinese

Su BZ, Li YH, Li LQ, Wang Y (2018) How do nonfarm employment stability influence farmers’ farmland transfer decisions? Implications for China’s land use policy. Land Use Policy 74:66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.053

Su WL, Liu CF, Zhang LX (2016) Study on the impact of non-agricultural employment on household agricultural mechanization service. J Agrotechn Econ 10:4–11. (in Chinese)

Taylor JE, Rozelle S, De Brauw A (2003) Migration and incomes in source communities: a new economics of migration perspective from China. Econ Dev Cult Change 1:75–101. https://doi.org/10.1086/380135

Ullah MW, Anad S (2007) Current status, constraints, and potentiality of agricultural mechanization in Fiji. Agric Mech Asia Aff 1:39. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.797806

Van den Berg MM, Hengsdijk H, Wolf J, Van-Ittersum MK, Wang GH, Roetter RP (2007) The impact of increasing farm size and mechanization on rural income and rice production in Zhejiang province, China. Agric Syst 3:841–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2006.11.010

Van der Ploeg JD, Ye JZ (2010) Multiple job holding in rural villages and the Chinese road to development. J Peasant Stud 3:513–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2010.494373

Wang JY, Xin LJ, Wang YH (2020a) How farmers’ non-agricultural employment affects rural land circulation in China? J Geogr Sci 3:378–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-020-1733-8

Wang L, Han Y (2020) Is the return migration of labor contrary to land transfer? How heterogeneous off-farm employment affects land transfer. Econ Probl 9:18–26. (in Chinese)

Wang XB, Weaver N, You J (2013) The social security function of agriculture in China. J Int Dev 1:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.2827

Wang XB, Yamauchi F, Huang JK (2016a) Rising wages, mechanization, and the substitution between capital and labor: evidence from the small-scale farm system in China. Agric Econ 3:309–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12231

Wang XB, Yamauchi F, Otsuka K, Huang JK (2016b) Wage growth, landholding, and mechanization in Chinese agriculture. World Dev 86:30–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.05.002

Wang YH, Li XB, He HY, Xin LJ, Tan MH (2020b) How reliable are cultivated land assets as social security for Chinese farmers? Land Use Policy 90:104318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104318

Wouterse F (2010) Migration and technical efficiency in cereal production: evidence from Burkina Faso. Agric Econ 5:385–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2010.00452.x

Xie HL, Lu H (2017) Impact of land fragmentation and non-agricultural labor supply on agricultural land management rights circulation. Land Use Policy 68:355–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.053

Yang J, Huang ZH, Zhang XB, Reardon T (2013) The rapid rise of cross-regional agricultural mechanization services in China. Am J Agr Econ 5:1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aat027

Yang J, Wan Q, Bi W (2020) Off-farm employment and grain production change: new evidence from China. China Econ Rev 63:101519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101519

Yang SY, Li W (2022) The impact of socialized agricultural machinery services on land productivity: evidence from China. Agriculture 12:2072. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12122072

Yang Y, Li R (2015) Labor transfer, factor substitution, and constraints. J Nanjing Agric Univ (Soc Sci Ed) 2:44-50+125. (in Chinese)

Yang ZY, Chen FB, Zhang RX (2022) Non-agricultural employment and agricultural production service adoption—a re-examination of substitution effect and income effect. J Agrotech Econ 3:84–99 (in Chinese)

Zheng HY, Ma WL, Guo YZ, Zhou XS (2021) Interactive relationship between non-farm employment and mechanization service expenditure in rural China. China Agric Econ Rev 1:84–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-10-2020-0251

Zhong FN, Lu WY, Xu ZG (2016) Whether migration of rural labor force is not conducive to food production?—Analysis of farmers’ factor substitution and planting structure adjustment behavior and constraints. Chin Rural Econ 7:36–47 (in Chinese)

Acknowledgements

Data used were from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) in this research, originally collected by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) of Peking University, China. This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Major Program) (22&ZD113).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guanqing Xu: Writing—original draft, methodology, formal analysis, conceptualization. Yifei Ma: Review and editing. Guoqing Qin: Empirical method. Caihua Xu: Review and editing. Yuchun Zhu: Supervision, resources, funding acquisition, conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The data employed in this study were obtained from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). The CFPS dataset is a secondary dataset, so ethical approval was obtained by the CFPS project team, not by the authors of this paper. The CFPS project and its data collection procedures were granted ethical approval by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University (IRB PU). The ethical approval number is IRB00001052-14010.

Informed consent

The informed consent of CPFS project can be found here: http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/docs/20200615135138318338.pdf.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, G., Ma, Y., Qin, G. et al. Why Chinese farmers are reluctant to transfer their land in the context of non-agricultural employment: insights from agricultural mechanization. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 428 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04559-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04559-8