Abstract

Scientific world is now privileging an interdisciplinary solution to problems, and the academic discourse it rests on is typically sensitive to its disciplinary context, but the discursive features of emerging interdisciplinarity remain under-investigated. This study aims to examine the deployment of interactive and interactional metadiscourse in research abstracts spanning three fields: computational linguistics, computer science, and applied linguistics. Based on a corpus of 270 abstracts in leading journals across the fields, the analysis demonstrated that writers in computational linguistics employed a greater frequency of both interactive and interactional metadiscourse in contrast to their counterparts in applied linguistics and computer science. Specifically, frame markers and self-mentions are predominantly utilized, reflecting the interdisciplinary essence of computational linguistics. Interestingly, apart from self-mentions, other interactional metadiscoursal elements are the second most frequently utilized category in computational linguistics abstracts. This observation underlines the field’s interdisciplinary nature, extends the common thread of disciplinary variation revealed in the literature, and points to addressing the disciplinary needs of these neighboring disciplines. In addition, pedagogical implications are also raised regarding the teaching of research writing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Successful academic writing often occurs within a shared professional context where individual writers achieve their personal and professional goals (Hyland, 2000). This socio-rhetorical context is referred to as a “discourse community” (Swales, 1990). In the context of disciplinary discourse communities, each discipline possesses distinct epistemological beliefs, discoursal practices, and norms of social interaction. Therefore, research on interdisciplinary discourse is crucial for helping writers enter and be accepted into their specific disciplinary communities. On one hand, interdisciplinary research can provide guidance on the academic literacy of novices by highlighting the writing preferences of neighboring disciplines. On the other hand, it offers valuable insights into the instruction of English for Academic Purposes (EAP).

The way that stance is expressed has been another crucial topic in EAP research. Its value in research papers has increased significantly as academic wiring is not just “a transparent transmitter of natural facts” (Bazerman, 1988, p.14), but the result of writers’ use of impersonal and interactional strategies to evaluate propositional contents, deliver attitudinal meanings, and ultimately convince disciplinary readers to believe the issues in question (Hyland and Jiang, 2018). This makes stance-taking a central element in knowledge construction and scientific communication, and thus a large body of research has investigated how stance is projected across different disciplines (Hyland and Jiang, 2016a; Hu and Cao, 2015).

Currently, the entire academic community is experiencing the emergence of the new liberal arts movement, a relatively recent disciplinary concept. This movement involves the integration of arts and sciences by restructuring traditional liberal arts and other professional courses, that is, integrating modern information technology into fields like philosophy, literature, language and others. The aim is to offer students comprehensive interdisciplinary learning opportunities, fostering knowledge expansion and nurturing innovative thinking skills. However, most previous investigations into academic discourse center on discrete and distinct disciplines, which are often in the form of hard science versus soft science. Disciplines that have overlaps and blur the disciplinary boundaries are rarely explored, and whether there exist any interdisciplinary variations or “preferred ways” in the use of stance resources remains to be seen and if so, to what extent. Barry and Born (2013) argues that a mere combination or a synthesis of individual disciplinary knowledge does not capture the essence of interdisciplinarity. It leads to new inter-disciplines via the process of being connected between two or multiple disciplines. Although Oakey and Russell (2014) and Choi and Richards (2017) are among the few studies which have approached the interdisciplinary research contexts, they both examined spoken interdisciplinary discourse.

In the context of the interdisciplinary wave, many inter-disciplines are emerging and warrant examination. For example, computational linguistics—an interdisciplinary field combining applied linguistics and computer science—is a growing area that uses computational tools to study and process natural language. Recently, with advancements in the liberal arts, computational linguistics and its applications have gained increasing attention. In this study, we focus on this interdisciplinary field (computational linguistics) and compare it with its related disciplines (applied linguistics and computer science) to explore how researchers convey their stance to interdisciplinary audiences.

Overall, this study aims to highlight the notion of “interdisciplinarity” concerning the utilization of interactive and interactional metadiscourse markers in research article (RA) abstracts and expand the line of work to uncover how expertise in computational linguistics is reflected in interdisciplinary research interaction mechanisms. Specifically, we addressed the following two questions:

-

(1)

Are there differences, if any, between the fields of computer science and applied linguistics, as well as their intermediate discipline of computational linguistics, in terms of how they employ interactive and interactional metadiscoursal resources in RA abstracts?

-

(2)

How does the intermediate discipline of computational linguistics reflect its nature of interdisciplinarity through the utilization of metadiscourse in RA abstracts?

Literature review

Interdisciplinary research discourse

Since the differences and similarities existing among disciplines may influence how knowledge is communicated and distributed to their intended audience (Becher and Trowler, 2001), it is widely acknowledged that academic authors from various disciplinary backgrounds are anticipated to adhere to specific discourse norms within their respective fields of expertise, which affords them communicative power in the course of knowledge construction and dissemination so as to establish a credible academic identity in their disciplinary domains.

As Becher (1989) points out, writing research papers in one discipline should adhere to the unspoken conventions, specific discursive codes and textual formulas within the discipline. Disciplinary knowledge can be negotiated through the creation of discourse which mirrors the disciplinary discourse conventions. According to Becher and Trowler (2001), disciplines are typically classified into hard and soft categories, determined by the knowledge they generate. Cross-disciplinary metadiscourse studies have become a central topic in metadiscourse research, where academic writers from diverse disciplinary backgrounds are expected to adhere to their specific conventions while engaging in knowledge construction and communication (Hyland, 2000).

Research on disciplinary metadiscourse has emerged as a prominent field in English for Academic Purposes (EAP), although the emphasis of this research varies. Recent studies adopt a diachronic perspective, tracing changing patterns of metadiscourse deployment across disciplines (Hyland and Jiang, 2016a, 2016b, 2018). Other studies have examined the influence of different languages and cultures on the use of cross-disciplinary metadiscourse (Dahl, 2004; Crismore et al. 1993). Additionally, Cao and Hu (2014) investigated the use of interactive metadiscourse across three soft disciplinary domains from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives. In addition to research articles, various specific genres have also been extensively examined in the context of cross-disciplinary discourse, including book reviews (Tse and Hyland, 2006) and L2 postgraduate writing (Hyland, 2004), among others. These studies primarily focus on the exploration of significant disciplinary differences, as evidenced by the diverse discursive and rhetorical strategies employed by writers across different disciplinary communities.

In the realm of cross-disciplinary research on the utilization of metadiscoursal resources, quite a few explorations have delved into comparisons of interactional metadiscourse between hard and soft domains (Becher and Trowler, 2001). For instance, Hyland (2005a) carried out a study of interactional metadiscourse in eight disciplines including both hard ones and soft ones, drawing a conclusion that interactional metadiscourse was more prevalent in soft disciplines than their counterparts. Similarly, Abdi (2002) conducted an investigation into the discussion sections of 40 research articles in natural and social sciences, comparing the employment of hedges, boosters, and attitude markers. The results indicated that there was a significant disparity in employing hedges and attitude markers between the two knowledge fields, with social scientists using more of these rhetorical features in texts. Analyzing 216 RAs in six disciplines to compare the use of boosters, Peacock (2006) found that boosters were more frequently used in the four social science fields than the two natural science fields.

In terms of employing interactive metadiscourse across different fields, on the other hand, there have also been numerous studies involved (Hyland, 2007; Dahl, 2004). Peacock (2010) examined the deployment of linking adverbials (overlapping with what Hyland called transitional markers), establishing a corpus of 320 RAs spanning eight disciplines categorized into sciences and non-sciences and discovered that those non-sciences exploited more linking adverbials than sciences.

Disciplines tend to function as granting academic institutions a context to guide their research endeavors (Clark, 1983). Theoretically, disciplinary frameworks define intellectual boundaries, allowing members to achieve different academic objectives within a unified and clearly defined context. However, since there are epistemological overlaps existing between certain academic fields, adhering strictly to these boundaries proves challenging in practice. Becher (1994) holds the notion that disciplines are characterized by the common characteristics of their associated research areas, and these areas have a tendency to intersect with those of adjacent fields (e.g., applied linguistics and computational linguistics), which has spawned the concept of inter-discipline.

Numerous studies have sought to explain these similarities by means of offering various categorization schemes for academic domains (Berliner, 2002; Durrant, 2017; Hyland, 2004). Biglan (1973), for example, evaluated faculty members’ perceptions based on attributes of 36 academic fields and identified three dimensions for the shape of academics’ awareness of those disciplines under study, and categorized them into three types: hard-soft, applied-pure, and life-nonlife systems. This categorization is essential due to the indication of how the characteristics of disciplines overlapping with other fields can impact the range of academic activities undertaken by their members.

Nevertheless, existing empirical research on interdisciplinary discourse appears to be both inadequate and fragmented. To characterize interdisciplinary discourse and offer researchers insights into the factors contributing to its success, Thompson and Hunston (2020) conducted a comparative study of research articles published in four leading journals within the environmental field: Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, Global Environmental Change, and Resource and Energy Economics. Additionally, other studies have compared single disciplines, such as Education and Neuroscience, with the emerging ‘inter-discipline’ of Educational Neuroscience, which integrates the two (Teich and Holtz, 2009; Muguiro, 2019). Another study on interdisciplinary discourse by Choi and Richards (2017) focused on spoken materials, investigating the dynamics of interdisciplinary collaboration and elucidating the characteristics of various disciplines and the concept of interdisciplinarity. In contrast, Teich and Holtz (2009) emphasized lexical items across two disciplines—Linguistics and Computer Science—and their interdisciplinary counterpart, Computational Linguistics. This research integrates the application of interdisciplinary distinctiveness with the concept of ‘Field’ from Systemic Functional Linguistics.

In summary, although a good deal of research has been focusing on cross-disciplinary comparison, the comparison is made either between pure hard disciplines, or pure soft disciplines, or the combination of hard ones and soft ones, with little attention given to intermediate disciplines---disciplines that have common knowledge areas and seek to achieve their respective rhetorical goals. Simultaneously, those few existing interdisciplinary studies are not embedded in a relatively comprehensive analytical framework. In addition, the extant literatures also suggest a paucity of metadiscoursal research on both side of interactive and interactional metadiscourse markers rather than just on one side.

Metadiscourse

Successful academic texts are supposed to build an appropriate relationship with readers, taking consideration of readers’ background knowledge, textual norms and processing needs. That is to say, writers should not only discuss a research topic and a shared interest, or just convey the propositional information reflective of the external reality, but should also employ various linguistic resources to maintain social relations with their readers (Hyland and Jiang, 2016a).

Metadiscourse is a range of broadly adopted linguistic resources pointing to the fields of discourse analysis, pragmatics, and language teaching (Hyland, 2015). It involves the commentary on a text provided by its producers during the process of writing or speaking (Hyland and Jiang, 2018), providing a robust way for writers to engage with readers language. Also, it has been fully proved that metadiscoursal resources serve as the lubricant that connects discourse and context in many fields of discourse scenes, such as text books (Crismore, 1984), postgraduate thesis (Hyland, 2004), economic discourse (Mauranen, 1993), political discourse (Abusalim et al. 2022), editorials (Alghazo et al. 2023a; Alghazo et al. 2023b) and so on.

Metadiscourse was first introduced by Zelig Harris (1959), a structural linguist, and gained significant scholarly attention and development in the mid-1980s, primarily due to a series of seminal works in applied linguistics (Vande Kopple, 1985; Crismore, 1989; Williams, 1981). The prominence of this research area is largely attributed to its strong relevance to academic writing. The fundamental concept of metadiscourse posits that language serves not only to convey information about the world but also to reflect upon the language itself. Through the deployment of various linguistic resources, metadiscourse facilitates readers’ organization, comprehension, and acceptance of the writer’s intended message (Jiang and Hyland, 2018).

There are various definitions and classifications of metadiscourse. Crismore et al. (1993) assert that metadiscourse encompasses linguistic elements that do not directly contribute to propositional content but serve to guide readers in understanding the presented information and assist writers in articulating their attitudes toward the propositional meaning. As noted by Ädel (2006), metadiscourse involves the reflexive use of language, which includes expressions that pertain to the ongoing discourse or its linguistic structure. This encompasses acknowledgments of the writer’s or speaker’s role, as well as considerations of the audience engaged in the discourse. Furthermore, a widely accepted conceptualization describes metadiscourse as “the self-reflective expressions used to negotiate interactional meanings in a text, assisting the writer (or speaker) to express a viewpoint and engage with readers as members of a particular community” (Hyland, 2005b, p. 37).

According to Hyland’s (2005b) model, metadiscourse can be classified into two types based on their rhetorical functions: interactive metadiscourse and interactional metadiscourse. The former is designed to organize the flow of information within the text, thereby aiding audiences in comprehending the writer’s intended meanings, while the latter emphasizes authorial presence by expressing the writer’s stance on propositional content and attitudes toward their disciplinary audience. This interaction fosters a sense of alliance between writers and readers, facilitating collaborative text construction (Hyland, 2005a; Hu and Cao, 2015). Furthermore, writers employ a variety of metadiscursive resources to anticipate potential reader disapproval or opposition, accommodate differing backgrounds and rhetorical norms, and address cultural needs, thereby establishing a reputable scholarly identity and fostering a close social relationship with readers (Hyland, 2007).

Research abstracts

Research article (RA) abstracts, serving as concise summaries of full articles, are regarded as a crucial academic genre across all fields of knowledge. They play a significant role in persuading audiences to engage more deeply with the content of the paper. RA abstracts not only function as the initial point of entry for readers but also constitute the first impression that the research article presents. As noted by Pho (2008, p. 31), an abstract effectively ‘sells’ the article. In an age of information overload, researchers from various discourse communities increasingly rely on abstracts to stay abreast of rapid developments within their fields (Khedri et al. 2013).

The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) defines an abstract as a condensed and precise representation of a document’s contents, ideally crafted by its author(s) for publication alongside the work. Drawing from this definition, Huckin (2006) identifies several key functions of an abstract: it serves as a standalone text that provides readers with an effective and quick summary of a study; it functions as a ‘screen device,’ helping readers decide whether to read the entire document; it acts as a ‘preview,’ offering a roadmap to guide readers through the article; and it serves as an ‘aid to indexing,’ facilitating access to information within large databases (Khedri et al. 2013). Therefore, mastering the skill of writing high-quality abstracts is essential for authors seeking acceptance within their disciplinary communities (Pho, 2008), particularly for novice writers aiming to gain entry into their respective fields. Moreover, a well-crafted abstract, conveying concise and clear information about the main content, allows readers to allocate more time and focus to the topics that interest them.

Given the significant research value of abstracts within academic genres, numerous studies and literature have emerged to assist writers in effectively promoting their research while aiding readers in grasping the main ideas of the text. Among these, some researchers have investigated cultural and linguistic variations in the use of interactional metadiscourse within research abstracts (Hu and Cao, 2011; Alghazo et al. 2021a), while others have examined abstract writing by comparing metadiscursive nouns across different genres (Jiang and Hyland, 2017). In the realm of cross-disciplinary research on research article abstracts, Alghazo et al. (2021b) conducted an investigation into grammatical devices of stance in RA abstracts, focusing specifically on applied linguistics and literature. Their study offered valuable insights into how academic writers within these disciplines can appropriately express their stances when composing research abstracts.

Simultaneously, the number of comparative studies examining metadiscourse from a disciplinary perspective is on the rise. For instance, Mansouri et al. (2016) employed both cross-linguistic and disciplinary perspectives to investigate metadiscourse in 20 abstracts from English and Persian research articles in the fields of computer engineering and applied linguistics. This cross-disciplinary study found a higher frequency of both interactive and interactional metadiscursive resources in the field of applied linguistics. Gillaerts and Van de Velde (2010) focused exclusively on applied linguistics, categorizing interactional metadiscourse into three sub-categories: hedges, boosters, and attitude markers. They adopted a diachronic perspective to assess whether the use of these linguistic resources in RA abstracts has evolved over the past 30 years. Similarly, Khedri et al. (2013) investigated interactive metadiscourse items in RA abstracts within two soft disciplines, applied linguistics and economics, based on Hyland’s (2005b) model. Their findings indicated that all types of interactive metadiscourse features, with the exception of transition markers, were more frequently employed by applied linguists than by economists. This suggests that applied linguists place greater emphasis on clarifying their claims and avoiding ambiguous interpretations, while economists tend to prioritize cohesive and persuasive argumentation.

Taken together, it appears that research attention to research article (RA) abstracts in interdisciplinary fields has been limited, and the mediation of rhetorical functions in these domains remains underexplored. To address these academic gaps, we aim to investigate the utilization and distribution of both interactive and interactional metadiscourse markers in RA abstracts from the disciplinary communities of applied linguistics, computer science, and their intersection, computational linguistics. The findings may offer valuable implications for RA abstract writing within these respective communities.

Methodology

Computational linguistics represents the intersection of multiple disciplines, focusing on how computers are utilized to process natural language. It arises from the integration of linguistics and computer science. On one hand, computational linguistics introduces novel topics for computer science, expanding its research and application scope. On the other hand, it has catalyzed the emergence of a new domain within linguistic inquiry. Consequently, it is evident that computational linguistics, applied linguistics, and computer science share both overlapping and distinct research paradigms and methodologies. In this section, we employ quantitative research methods to analyze the use of metadiscourse in research article (RA) abstracts across these three disciplines. Given the empirical nature of this study, we aim to utilize quantitative analysis to elucidate the interdisciplinary relationships by collecting and analyzing data. Quantitative methods are recognized for their high reliability and validity, allowing audiences to recognize the similarities and differences among the examined disciplines more intuitively and efficiently.

Corpus data

To address the research questions of our comparative and contrastive study, we constructed a corpus consisting of 270 research article (RA) abstracts, with 90 abstracts from each discipline: applied linguistics, computational linguistics, and computer science. For each of these three fields, we selected three prestigious journals published between 2017 and 2021, based on their journal rankings and 5-year impact factors. The applied linguistics journals included Applied Linguistics, TESOL Quarterly, and The Modern Language Journal. Abstracts for computational linguistics were sourced from Computational Linguistics, Natural Language Engineering, and Language Resources and Evaluation. The computer science corpus comprised abstracts from Artificial Intelligence, IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, and IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing. We randomly extracted 30 abstracts from corresponding research articles in each journal. The details of the corpus are presented in Table 1.

Analytical procedure

To identify the metadiscoursal resources, we adopted a well-established model introduced by Hyland (2005b). According to Hyland’s taxonomy, metadiscourse can be categorized into interactive ones and interactional ones. Further explanations and examples are as follows:

Interactive metadiscourse refers to features that organize propositional contents and guide readers through a text. They focus in the discourse flow, considering readers’ background knowledge, textual experiences as well as processing needs, and reflecting what is supposed to be made explicit to readers. Interactive resources include transition markers, frame markers, endophoric markers, evidentials, and code glosses. The functions of each interactive marker are explicated below.

Transition markers comprise conjunctions and adverbial phrases which signal internal relationships of additions, comparisons and consequences, aiding readers to make pragmatic connections between main clauses (e.g., in addition/but/thus). Frame markers serve the purpose of indicating text structures and boundaries by organizing the sequence of events, labeling different stages of the text, and signaling shifts in topics or goals, thereby making the content more explicit to readers. (e.g., finally/to conclude/my purpose is). Endophoric markers guide readers to other parts of the text, providing readers with the propositional information to facilitate their understanding of the writer’s intended meanings. (e.g., noted above/see Fig/in Section 2). Evidentials are linguistic features referring to intertextual materials and claims taken from other texts, which help writers to establish their authorial presence and promote a persuasive goal. (e.g., as/ according to). Code glosses serve to reiterate the aforementioned arguments, clarifying writers’ intended meanings and simultaneously easing readers’ understanding. (e.g., for instance, /in other words).

Interactional metadiscoursal resources are linguistic elements that focus on the interpersonal aspects in a text, expressing writers’ stance and their engagement with readers to present writers’ attitude towards data, claims and readers and realize a suitable writer-reader relationship. They comprise hedges, boosters, attitude markers, engagement markers, and self-mentions. The functions of each interactional marker are explicated below.

Hedges refer to linguistic features that aim to mitigate writers’ full commitment and certainty to propositional content (e.g., might/perhaps/possible), while boosters function to express writers’ certainty and close down alternative or conflicting views from audience (e.g., in fact/definitely/it is clear). In addition, attitude markers mainly serve to convey the writers’ attitude and evaluation of propositional information to persuade readers by accentuating shared values and attitudes (e.g., unfortunately/I agree/surprisingly). Engagement markers are rhetorical devices employed to directly address readers, including them as participants in the evolving discourse, or anticipating their objections. (e.g., consider/see/note that). Finally, self-mentions relate to items explicitly referring author’s presence in a text through first-person pronouns and possessives (e.g., I, we, our, my, etc.).

To identify metadiscourse items accurately, we use the concordance software Antconc (Anthony, 2011). It is widely accepted that metadiscourse is an intrinsically fuzzy category, implying that a lexico-grammatical feature can serve multiple functions, and whether it qualifies as metadiscourse depends on the context. In a word, metadiscourse is a relatively flexible linguistic category to which writers can add new items based on their contextual and rhetorical needs, which indicates that items taken as metadiscourse in a specific context are likely to act as propositional information in another. Hence, it is indispensable to precisely distinguish metadiscoursal resources in a particular text.

To achieve this goal, we conducted our research following several steps. First, we retrieved all selected research article (RA) abstracts directly from the electronic editions of their respective journals. Next, the materials were converted into plain text format and input into AntConc to automatically identify metadiscursive resources. To further verify whether the results generated by the software constituted metadiscourse, we manually reviewed each concordance line and excluded extraneous examples. Additionally, to mitigate the influence of corpus size and facilitate meaningful comparisons across the corpora, the results were standardized to 10,000 words.

Results and discussion

Results

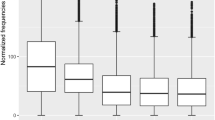

In this section, we present the results of the quantitative analysis. To identify potential disciplinary differences in metadiscourse usage, we calculated the frequency of each metadiscursive item per 10,000 words. The results are organized according to the sub-types of interactive and interactional metadiscourse, which will be discussed separately in detail.

Interactive metadiscourse

Interactive metadiscourse is employed to organize the flow of propositional content, build up his/her preferred meanings, and assist readers in navigating the text. Table 2 shows the distribution of interactive metadiscourse among three disciplines.

Overall, frame markers emerged as the most frequently used interactive resource, totaling 174 tokens (106.13 per 10,000 words) in applied linguistics journals, 233 tokens (131.63 per 10,000 words) in computational linguistics journals, and 156 tokens (86.24 per 10,000 words) in computer science journals. Transition markers ranked second, with 145 occurrences (88.44 per 10,000 words) in applied linguistics, 198 (111.86 per 10,000 words) in computational linguistics, and 181 (100.06 per 10,000 words) in computer science. The third most frequent category was code glosses, which appeared 65 times (39.65 per 10,000 words) in applied linguistics, 98 times (55.36 per 10,000 words) in computational linguistics, and 96 times (53.07 per 10,000 words) in computer science. In contrast, the frequencies of both endophoric markers and evidential markers were relatively low. A total of 14 endophoric markers were identified in the corpus, with 5 (3.05 per 10,000 words) in applied linguistics, 3 (1.69 per 10,000 words) in computational linguistics, and 6 (3.32 per 10,000 words) in computer science. Regarding evidential markers, only 6 occurrences were noted across all three disciplines, with applied linguistics (1.83 per 10,000 words) and computer science (1.66 per 10,000 words) each accounting for 3 instances, while the computational linguistics sub-corpus contained no evidential markers. This distribution of interactive resources is not uniform across the three disciplines. To clearly illustrate the distinctions and similarities in the deployment of interactive metadiscourse, the detailed status of each sub-type across the three disciplines will be discussed in the next section.

Interactional metadiscourse

Interactional metadiscourse is deployed to reflect the writers’ presence, signal their attitudes, and engage with their imagined readers through the process of textual construction. Table 3 summarizes the specific results of interactional metadiscourse.

In general, self-mentions emerged as the interactional resource with the highest frequency of occurrence, with applied linguists using it 70 times (42.70 per 10,000 words), computational linguists 323 times (182.48 per 10,000 words), and computer scientists 301 times (166.39 per 10,000 words). The next most prevalent interactional items were hedges, which appeared 160 times (97.59 per 10,000 words) in applied linguistics, 102 times (57.62 per 10,000 words) in computational linguistics, and 84 times (46.43 per 10,000 words) in computer science. Boosters ranked as the third most frequent category, with 80 occurrences (44.80 per 10,000 words) in applied linguistics, 90 (50.84 per 10,000 words) in computational linguistics, and 121 (66.89 per 10,000 words) in computer science. Attitude markers were the fourth most frequent, totaling 22 instances (13.42 per 10,000 words) in applied linguistics, 26 (14.69 per 10,000 words) in computational linguistics, and 40 (22.11 per 10,000 words) in computer science. Finally, engagement markers exhibited the lowest frequency across the three disciplines, with 43 occurrences (26.23 per 10,000 words) in applied linguistics, 14 (7.91 per 10,000 words) in computational linguistics, and 9 (4.98 per 10,000 words) in computer science. Notably, the data presented in Table 3 highlight significant differences in how writers from different communities employ interactional resources, which will be further analyzed and compared in detail below.

Discussion

Collectively, computational linguists utilize the most interactive resources among the three groups, with a frequency of 300.54 per 10,000 words. This finding is not particularly surprising, as computational linguistics is an emerging discipline that serves as a mixed discourse community, incorporating both computer scientists and applied linguists, each with their own disciplinary epistemologies and established writing conventions. Consequently, computational linguists are expected to invest more in interactive features to manage the flow of articles explicitly and guide readers effectively. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the overall occurrence of interactive items in applied linguistics is slightly lower than in computer science (239.1 per 10,000 words vs. 244.35 per 10,000 words), which contrasts with the findings of Mansouri et al. (2016). This discrepancy may arise from the study’s exclusive focus on articles written in English, without addressing cross-cultural aspects of research article abstracts.

Regarding the subtypes of interactive metadiscoursal elements across disciplines, Table 2 reveals a notable disparity in the utilization of transition markers by abstract writers. Specifically, applied linguists exhibit the lowest frequency of transition markers compared to computational linguists and computer scientists (88.44 per 10,000 words vs. 111.86 per 10,000 words vs. 100.06 per 10,000 words). This finding contrasts somewhat with the earlier study by Peacock (2010). One possible explanation for this discrepancy may be related to diachronic factors (Hyland and Jiang, 2018). Additionally, the current study focuses solely on research article abstracts rather than the entirety of the articles.

In examining the disciplinary distinctiveness in the deployment of transition markers in this study, one possible explanation is that authors in computer science and computational linguistics tend to compare and contrast their findings with earlier studies, thereby emphasizing the significance of their results. In contrast, authors in applied linguistics often prefer to present their own findings without connecting to previous research. The use of transition markers primarily serves to establish cognitive connections between clauses and ideas, facilitating the flow of information (Biber et al. 1999). Consequently, a greater use of transition markers may enhance the logical relationships between semantic units in these two disciplines with a scientific background (1 and 2).

-

(1)

The results of string kernels… are also significantly better than the state-of-the-art approach. In addition, in a cross-corpus experiment, the proposed approach shows that it can also be topic independent, improving the state-of-the-art system by 32.3%. (CL)

-

(2)

The noise power spectrum (NPS) of an image sensor provides the spectral noise properties needed to evaluate sensor performance. Hence, measuring an accurate NPS is important. However, the fixed pattern noise from the sensor’s nonuniform gain inflates the NPS, which is measured from images acquired by the sensor. (CS)

When examining frame markers—metadiscoursal features that delineate text boundaries and structures—it is evident that they are extensively used across all three knowledge fields. This trend may be attributed to the internal structure and generic characteristics of research article abstracts, where each section of the article is summarized according to the IMRD (Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion) format. However, a significant disciplinary discrepancy exists in the deployment of frame markers, with computer scientists using them far less frequently in their abstracts than their counterparts in applied linguistics and computational linguistics. This finding is not surprising, as computer science is categorized as a hard discipline, where practitioners tend to possess specialized domain knowledge and, therefore, require less guidance in understanding propositional content and textual structure (3).

In a similar vein, the aforementioned factor may also explain the significant use of frame markers in computational linguistics. From an interdisciplinary perspective, computational linguistics represents a convergence of applied linguistics and computer science, embodying the epistemological characteristics and knowledge construction methods of both soft and hard disciplines. Consequently, due to the dual nature of the discipline and the diverse intellectual backgrounds of its audience, writers in computational linguistics often employ a greater number of frame markers in their abstracts to delineate text structure and enhance discourse organization. This strategy aims to guide readers toward specific areas for intended interpretations (Hyland and Jiang, 2020) (4).

-

(3)

Last, we show the versatility of our approach using a number of specific scenarios (CS).

-

(4)

First, it is not clear why such a simple approach can compete with far more complex approaches that take words, lemmas, syntactic information, or even semantics into account. Second, although the approach is designed to be language independent, all experiments to date have been on English (CL).

In terms of endophoric markers and evidential markers, as illustrated in Table 2, both metadiscoursal features are infrequently employed in research article abstracts across all investigated disciplines. Furthermore, there is a lack of significant distinction in the usage of these markers among the three fields. This finding may be attributed to the rhetorical functions of these two interactive resources. Endophoric markers direct readers to other parts of the text or make supporting data accessible, while evidential markers refer to information outside the text, such as citations. However, the primary role of abstracts is to provide readers with a concise overview of the entire article, rather than to include excessive information, whether within or outside the text.

It is noteworthy that code glosses are less frequently represented in applied linguistics abstracts compared to the other two disciplines. As previously mentioned, code glosses are rhetorical features used to elaborate on the writer’s intended meaning. This disciplinary variation can be explained by findings from earlier research. Hyland (2007) found that the occurrence of code glosses in research article abstracts is significantly lower than in full research papers, registering approximately 53 cases per 10,000 words. This preference aligns with the brevity and conciseness characteristic of abstracts, which often adhere to the principle of economy in content presentation. In contrast, the sub-functions of code glosses, such as reformulation and exemplification, are more commonly employed in comprehensive research writing. Additionally, the relatively low presence of code glosses in applied linguistics may indicate broader disciplinary differences. In scientific fields, knowledge is typically accumulated and presented in a highly structured manner, requiring greater rhetorical investment to expound upon previous statements (5 and 6). Writers in applied linguistics abstracts tend to reserve further elaboration for the full paper, focusing instead on presenting essential and principal information within the abstracts.

-

(5)

Thus, typical problems of the first-order models, such as the staircasing effect cannot be overtaken. (CS)

-

(6)

I present a structured review of the evidence on whether BLEU is a valid evaluation technique—in other words, whether BLEU scores correlate with real-world utility and user-satisfaction of NLP systems. (CL)

Beyond interactive metadiscourse, the role of interactional metadiscourse in the selected disciplines merits further discussion. Overall, research article abstracts in computational linguistics exhibit the highest volume of interactional markers (313.54 per 10,000 words), only slightly surpassing those in computer science (306.8 per 10,000 words). This suggests a ‘hard’ characteristic of this intermediate discipline from the interactional perspective. In contrast, writers in applied linguistics employ significantly fewer interactional markers (228.74 per 10,000 words) than their counterparts in computer science and computational linguistics. This finding aligns with the conclusions of Hyland and Jiang (2018), which indicate a notable decline in interactional metadiscourse within soft fields over the past 50 years, accompanied by a substantial increase in its use within scientific subjects.

Regarding subtypes of interactional devices, hedges—used to mitigate a writer’s full commitment to a claim—are frequently employed across all disciplines in research article abstracts, as shown in Table 2. Notably, applied linguists utilize hedges more frequently than their counterparts in the sciences, which aligns with Abdi’s (2002) conclusion that social scientists often exhibit greater uncertainty in their texts. In contrast, the computer science group employs the fewest hedges. This discrepancy can be attributed to the epistemological differences in research methods and knowledge creation among disciplines. Specifically, soft fields tend to be more discursive than hard fields, where qualitative analyses or statistical probabilities are typically used to construct knowledge (Hyland, 2004). Consequently, writers in applied linguistics, a distinctly soft discipline, are inclined to use more hedges to leave discursive space for readers, anticipate potential objections, and express respect for their peers’ perspectives, thereby accommodating future revisions (7).

-

(7)

Given the importance of CEFR levels in many high-stakes contexts, the results suggest the need of a large empirical validation project.

In contrast, computer science, as a branch of hard disciplines, exhibits a clear inclination towards adopting quantitative research methods for knowledge creation and claim-making. Specifically, computer scientists often base their arguments on experimental data, natural principles, and objective realities, resulting in a reduced use of hedges. This finding aligns with previous studies by Hyland (2005a) and Abdi (2002), which highlight the differential employment of interactional metadiscourse across hard and soft knowledge fields.

Boosters, to some extent the rhetorical opposite of hedges, refer to emphatic and categorical expressions used to enhance commitment to propositions. As shown in Table 3, boosters are used least frequently in applied linguistics, with computer science displaying the highest frequency of occurrence. The lower frequency in applied linguistics may reflect writers’ intent to control authorial presence and emphasize objective interpretation of linguistic phenomena (Bazerman, 1988). Excessive definitive judgments and categorical claims in an RA abstract from a soft discipline could alienate readers, limiting the opportunity for writer-reader negotiation. In contrast, grounded in quantitative methods and experimental data, computer scientists are inclined to use more boosters to persuade readers of their arguments and establish a strong writer-reader connection (8, 9). The higher booster frequency in these two disciplines may also relate to the mounting pressure to publish and commercial interests, which may encourage more assertive language use (Jiang and Hyland, 2022).

-

(8)

We show that going beyond optimization approach is a promising task that provides considerable insights in which feature combinations contribute to the overall readability prediction. (CL)

-

(9)

Experimental results on real world data sets show the effectiveness of the proposed method for principal component analysis. (CS)

Attitude markers convey writers’ evaluative perceptions of propositional content and reflect affective stances toward academic claims. It is observed that all three disciplines employ a relatively low frequency of attitude markers in their abstracts, with no statistically significant differences between them. This finding aligns with Hyland and Guinda’s (2012) view that writers are cautious in using attitude markers to maintain a tone of fairness and objectivity in research writing.

The category of engagement markers—reader-oriented rhetorical resources—refers to linguistic expressions that allow the writer to openly acknowledge the reader’s presence and invite them to engage in jointly interpreting the knowledge and arguments presented. As shown in Table 3, engagement markers appear significantly more frequently in applied linguistics than in its hard and interdisciplinary counterparts, with the lowest frequency observed in computer science. This difference likely stems from the disciplinary epistemologies and conventional methods of knowledge construction within the humanities and social sciences. Applied linguists, inclined to present arguments in a more discursive manner, employ engagement markers to foster a rhetorical context that establishes an appropriate writer-reader relationship and promotes interpersonal solidarity, treating readers as insiders to the text and expressing a sense of collegiality (10).

-

(10)

The close reading of a multimodal text authored by an eight-year-old schoolgirl in the context of a creative-writing activity allows us to identify poetic and artistic means…(AL)

Additionally, RA abstracts function as promotional tools designed to capture readers’ interest and encourage them to read the full article (Dahl, 2009; Hyland, 2000; Hyland and Tse, 2005). Given this rhetorical purpose and the genre’s concise nature, it is unsurprising that applied linguists utilize engagement markers as a strategy to attract readers, positioning them as co-participants in the discourse. In contrast, computer scientists employ the fewest engagement markers—only about one-fifth of the frequency seen in applied linguistics. As a distinctly “hard” knowledge domain, computer science involves impersonal activities such as computational modeling and software development, with community members generally possessing specialized expertise. This disciplinary norm reflects the assumption that the audience is already proficient in the field’s technical knowledge, thereby reducing the need for engagement markers to address or persuade readers—explaining their notably low occurrence in computer science abstracts.

Regarding self-mentions, which serve as a rhetorical feature that explicitly references the writer, notable cross-disciplinary differences emerge in abstract writing, as illustrated in Table 3. The frequency of self-mentions in computer science is nearly four times that in applied linguistics (166.39 versus 42.70 per 10,000 words). Moreover, computational linguistics leads in the use of self-mentions, though only slightly more than computer science (182.48 versus 166.39 per 10,000 words). This pronounced cross-disciplinary variation may be attributed, in part, to factors of collaborative writing and co-authorship, commonly realized through the inclusive we. In recent years, academic collaboration has become more prevalent, driven by the complexity of contemporary research questions and an increasingly supportive environment for multi-investigator work, especially in “hard” fields (Hyland and Jiang, 2016b). As advancements in artificial intelligence and data mining continue to create complex research challenges within computer science, extensive collaboration and teamwork among computer scientists have become essential—providing a plausible explanation for the high frequency of self-mentions in this discipline (11).

-

(11)

In this paper, we try to address these shortcomings…Rather than using crude intensity values, we use 3D tensor structure at each pixel…Then, we form view clusters from multiple view action data and use space-time correlation filtering to achieve discriminative view representations. (CS)

Additionally, as an interdisciplinary field bridging applied linguistics and computer science, computational linguistics may attract a larger number of collaborative authors with diverse backgrounds (12), which could explain the slightly higher frequency of self-mentions by computational linguists. Conversely, research in applied linguistics is frequently conducted by individual authors, with limited use of the first-person singular in abstracts compared to the inclusive we. Furthermore, applied linguists often aim to minimize authorial presence in abstracts, prioritizing propositional content to effectively “market” their discursive knowledge. This tendency likely contributes to the relatively infrequent use of self-mentions in applied linguistics.

-

(12)

Because we also have gold standard information available for those features requiring deep processing, we are able to investigate the true upper bound of our Dutch system. Interestingly, we will observe that the performance of our fully automatic readability prediction pipeline is on par with the pipeline using gold-standard deep syntactic and semantic information. (CL)

Conclusion

As an emerging field, the interdisciplinary domain has not been adequately touched upon. While most previous studies were carried out to examine disciplinary variation, we took an unusual route to explore how metadiscoursal resources are used in interdisciplinary discourse. Our study has examined the use and distribution of both interactive and interactional metadiscourse in RA abstracts across three interrelated disciplines to find out how writers from different disciplinary communities organize their abstracts, how interactive and interactional metadiscoursal resources are deployed in different disciplines, how disciplinary information is presented to achieve cohesion and persuasion towards different readership, and how the discipline-specific discursive conventions are reflected in these three groups of scholars.

The results of the study do indicate some major differences and certain similarities across three disciplines concerning disciplinary epistemology as well as ways of knowledge construction, and the intermediate nature of computational linguistics is distinctly reflected as well through the employment of metadiscoursal resources. In specific, it can be found that writers in computational linguistics employed the highest number of both interactive makers and interactional markers compared to its counterparts, with frame markers and self-mentions leading the road. Furthermore, we found that hedges, boosters, attitude markers and engagement markers are all the second most frequently used category in computational linguistics abstracts, which reflects the interdisciplinary nature of this knowledge field from a statistical dimension; the frequency of self-mention in computational linguistics is far greater than applied linguistics, yet just slightly greater than computer science and the more interesting point is that the distribution of the whole types of metadiscourse are relatively even distributed among computer science and computational linguistics, manifesting the similarities between the two disciplines and also the hard aspect of computational linguistics.

Overall, the disciplines we chose in this comparative study are highly related (namely, applied linguistics, computational linguistics, and computer science), with computational linguistics being the intermediate discipline of the soft and hard academic communities. Through this comparative study, it can be concluded that the integration of different background into one discipline would change how this group of writers interact with their readers and persuade them. Meanwhile, the findings of metadiscoursal usage in RA abstracts offer an insight into how academic writers belonging to different but related disciplinary communities perceive the distinct rhetorical contexts within which they conduct research and the support readers might require to comprehend and acknowledge their arguments. Besides, the analysis shed light on pedagogical implications of how to deploy interactive and interactional metadiscourse into abstracts consistent with disciplinary practice, facilitating writers from different fields when they work on abstract writing and helping novices integrate into corresponding community.

Simultaneously, there are also some limitations reflected in this study. First, we only explored the use of metadiscourse in three disciplines, with each field only consisting one discipline, which has confined the generality of the findings. Second, the selected disciplines are only limited to computer-related ones except for applied linguistics, restricting the level of multidisciplinary comparative research. Based on the limitations above, future research endeavors could expand the scope of investigation to encompass a broader array of disciplines across various academic domains to achieve a more comprehensive and complete cross-disciplinary comparative study, especially from the perspective of interdisciplinarity. Furthermore, research on metadiscourse in RA abstracts can be extended to other sub-genres, such as introduction or discussion sections of research articles, so that we can provide more integrated ways to instruct academic writing.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. E-mail: jwyang20@mails.jlu.edu.cn.

References

Abdi R (2002) Interpersonal metadiscourse: An indicator of interaction and identity. Discourse Studies 4(2):139–145

Abusalim N, Zidouni S, Alghazo S et al. (2022) Textual and interpersonal metadiscourse markers in political discourse: A case study. Cogent Arts Humanite 9(1):2124683

Ädel A (2006) Metadiscourse in L1 and L2 English. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Alghazo S, Al Salem MN, Alrashdan I (2021a) Stance and engagement in English and Arabic research article abstracts. System 103:102681

Alghazo S, Al-Anbar K, Jarrah M et al. (2023a) Engagement strategies in English and Arabic newspaper editorials. Humanities Social Sciences Communications 10(1):1–10

Alghazo S, Al-Anbar K, Altakhaineh ARM et al. (2023b) Interactive metadiscourse in L1 and L2 English: Evidence from editorials. Top Linguist 24(1):55–66

Alghazo S, Al Salem MN, Alrashdan I et al. (2021b) Grammatical devices of stance in written academic English. Heliyon 7(11)

Anthony L (2011) AntConc 3.4.3. http://www.laurenceanthony.net/software.html

Barry A, Born G (2013) Interdisciplinarity: reconfigurations of the social and natural sciences. In Interdisciplinarity (pp. 1–56). Routledge

Bazerman C (1988) Shaping Written Knowledge. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Becher T (1989) Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual inquiry and the cultures of disciplines. Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press, Milton Keynes, UK

Becher T (1994) The significance of disciplinary differences. Stud High Educ 19(2):151–161

Becher T, Trowler P (2001) Academic tribes and territories. McGraw-Hill Education, UK

Berliner DC (2002) Comment: Educational research: The hardest science of all. Educ Res 31(8):18–20

Biber D (1999) A register perspective on grammar and discourse: Variability in the form and use of English complement clauses. Discourse Stud 1(2):131–150

Biglan A (1973) The characteristics of subject matter in different academic areas. J Appl Psychol 57(3):195

Cao F, Hu G (2014) Interactive metadiscourse in research articles: A comparative study of paradigmatic and disciplinary influences. J Pragmat 66:15–31

Choi S, Richards K (2017) Interdisciplinary discourse: Communicating across disciplines. Springer

Clark BR (1983) The contradictions of change in academic systems. High Educa 12(1):101–116

Crismore A (1984) The Rhetoric of Textbooks: Metadiscourse. J Curriculum Stud 16(3):279–296

Crismore A (1989) Talking with readers: Metadiscourse as rhetorical act. Peter Lang, New York

Crismore A, Markkanen R, Steffensen MS (1993) Metadiscourse in persuasive writing: A study of texts written by American and Finnish university students. Writ Commun 10(1):39–71

Dahl T (2004) Textual metadiscourse in research articles: A marker of national culture or of academic discipline? J Pragmat 36(10):1807–1825

Dahl T (2009) Author identity in economics and linguistics abstracts. Cross-linguistic Cross-cultural Perspectives Academic Discourse 193:123

Durrant P (2017) Lexical bundles and disciplinary variation in university students’ writing: Map** the territories. Appl Linguist 38(2):165–193

Gillaerts P, Van de Velde F (2010) Interactional metadiscourse in research article abstracts. J Engl Acad Purp 9(2):128–139

Harris Z (1959) The transformational model of language structure. Anthrop Linguist 1(1):27–29

Hu G, Cao F (2011) Hedging and boosting in abstracts of applied linguistics articles: A comparative study of English- and Chinese-medium journals. J Pragmat 43:2795–2809

Hu G, Cao F (2015) Disciplinary and paradigmatic influences on interactional metadiscourse in research articles. Engl Spec Purp 39:12–25

Huckin T (2006) ‘Abstracting from abstracts’. In: M Hewings (ed) Academic Writing in Context: implications and applications. Birmingham University Press, Birmingham p 93–103

Hyland K (2000) Disciplinary discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. Longman, London

Hyland K (2004) Disciplinary interactions: Metadiscourse in L2 postgraduate writing[J]. J Second Lang Writ 13(2):133–151

Hyland K (2005a) Stance and engagement: A model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Stud 7(2):173–192

Hyland K (2005b) Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing. Continuum, London

Hyland K (2007) Applying a gloss: Exemplifying and reformulating in academic discourse. Appl Linguist 28(2):266–285

Hyland K (2015) Academic publishing: issues and challenges in the construction of knowledge. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hyland K, Tse P (2005) Hooking the reader: A corpus study of evaluative that in abstracts. Engl Spec Purp 24(2):123–139

Hyland K, Guinda CS (2012) Stance and Voice in Written Academic Genres. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London

Hyland K, Jiang F (2016b) “We must conclude that…”: A diachronic study of academic engagement[J]. J Engl Acad Purp 24:29–42

Hyland K, Jiang F (2016a) Change of Attitude? A Diachronic Study of Stance. Writ Commun 33(3):251–274

Hyland K, Jiang F (2018) “In this paper we suggest”: changing patterns of dis- ciplinary metadiscourse. Engl Spec Purp 51:18–30

Hyland K, Jiang F (2020) Text-organizing metadiscourse: Tracking changes in rhetorical persuasion. J Hist Pragmat 21(1):137–164

Jiang F, Hyland K (2017) Metadiscursive nouns: Interaction and cohesion in abstract moves. Engl Spec Purp 46:1–14

Jiang F, Hyland K (2018) Nouns and Academic Interactions: A Neglected Feature of Metadiscourse. Appl Linguist 39(4):508–531

Jiang F, Hyland K (2022) “The datasets do not agree”: Negation in research abstracts. Engl Spec Purp 68:60–72

Khedri M, Heng CS, Ebrahimi SF (2013) An exploration of interactive metadiscourse markers in academic research article abstracts in two disciplines. Discourse Stud 15(3):319–331

Kopple WJV (1985) Some exploratory discourse on metadiscourse. Coll Compos Commun 26:82–93

Mansouri S, Najafabadi MM, Boroujeni SS (2016) Meta-discourse in Research Article Abstracts: A Cross-Lingual and Disciplinary Investigation. Journal Applied Linguistics Language Research 3(4):296–307

Mauranen A (1993) Contrastive ESP rhetoric: Metatext in Finnish-English economics texts. Engl Spec Purp 12(1):3–22

Muguiro NF (2019) Interdisciplinarity and academic writing: a corpus-based case study of three interdisciplines. Anuario 16(16):82–82

Oakey D, Russell D (2014) Beyond single domains: Writing in boundary crossing

Peacock M (2006) A cross-disciplinary comparison of boosting in research articles. Corpora 1(1):61–84

Peacock M (2010) Linking adverbials in research articles across eight disciplines. Ibérica (20):9–34

Pho PD (2008) Research article abstracts in applied linguistics and educational technology: A study of linguistic realizations of rhetorical structure and authorial stance. Discourse Stud 10(2):231–250

Swales J (1990) Genre analysis: English in academic and research setting. Cambridge University Press, UK, Cambridge

Teich E, Holtz M (2009) Scientific registers in contact: An exploration of the lexico-grammatical properties of interdisciplinary discourses. Int J Corpus Linguis 14(4):524–548

Thompson P, Hunston S (2020) What Topic Modelling Can Indicate About Interdisciplinary Research Discourse. Conference of the American Association for Applied Linguistics (AAAL)

Tse P, Hyland K (2006) ‘So what is the problem this book addresses?’: Interactions in academic book reviews. Text Talk 26(6):767–790

Williams JM (1981) Style: Ten Lessons in Clarity and Grace. Scott Foresman, Boston

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author conceptualized, drafted, and revised the manuscript, and provided final approval for the published version. He agrees to be accountable for ensuring the accuracy and integrity of the content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

The authors declare no competing interests. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J. Metadiscourse in the research abstracts of an interdisciplinary field: a case study of computational linguistics. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 448 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04582-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04582-9