Abstract

To better understand donors’ decisions within the nonprofit context, it is important to empirically attend to their perceptions of nonprofits. Drawing upon extant literature, a parsimonious conceptual model of donor perceptions is developed. Hypotheses derived from the model are empirically tested by means of structural equation modelling using 2017 survey data from 400 usable responses. The study finds positive associations between (1) perceptions of financial transparency and perceived performance, (2) perceived financial transparency and donor trust, and (3) donor trust and perceived performance. Different explanatory mechanisms are suggested to account for these findings. (1) could be explained by an ‘informational’ mechanism, whereas (2) and (3) could be explained by a ‘performative’ mechanism. The focus on donor perceptions has important implications for regulators when considering the assessment of nonprofit disclosure practices. The findings would also be valuable to nonprofits in developing strategies aimed at legitimising their operations by improving perceptions of their performance and trust in their ‘organisational brand’. By examining subjective perceptions of transparency and performance, this paper extends the nonprofit literature on donors’ perceptions, and adds a fresh perspective to the growing body of work on nonprofit transparency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Donor perception of nonprofits’ performance is critical for the survival of these organisations (Hyndman and McConville 2018). Public scandals around misallocation of donated funds to executive salaries and inflated overhead costs (e.g., Ricketts 2021) could undermine trust, elevate perceived risks tied to donation use (Agyemang et al. 2019), and render stark the information asymmetries between donors and nonprofits. Thus, regulatory efforts focused on accountability and transparency seek to improve donors’ trust in the performance of nonprofits. In this study, we examine whether there are indeed empirical relationships between donors’ perceptions of financial transparency, trust, and perceived performance of nonprofits.

The literature on nonprofit accountability, transparency, trust, and performance is by now well established. Recent studies have investigated micro-level accountability of social analysis and its link to trust (Yates et al. 2021), the impact of financial statement disclosures on credit financing (Lancksweerdt et al. 2023), and implications of comprehensive accountability on program effectiveness (Hengevoss 2023). Another stream of nonprofit studies investigating accountability and transparency has focused on motivations of individual giving (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017), and the determinants and consequences of disclosures around contributions (Harris and Neely 2018). This stream also explores links between donors’ perceptions of the decision-usefulness of financial disclosures and donation intentions (Ghoorah et al. 2021), as well as the impact on trust in accountability mechanisms tailored to stakeholders’ information needs (Hyndman and McConville 2018).

Most of these studies attend to the objective aspects of accountability, transparency, and performance. What is lacking, however, is an examination of subjective perceptions of these factors. With the exception of Yang and Northcott (2018), Farwell et al. (2019) and Daff and Parker (2021), studies rarely ask whether subjective perceptions influence decisions. Yang and Northcott’s (2018) case study of two New Zealand charities attempts to understand the role of ‘identity accountability’ in shaping outcome measurement practices by examining staff and managers’ perceptions and experiences. Similarly, Daff and Parker’s (2021) interviews with accountants explore perceptions of factors conditioning the communication of accounting information within Australian nonprofits. Meanwhile, Farwell et al.’s (2019) survey of the Canadian public’s perceptions of financial accountability, transparency, and familiarity aims to determine whether these factors uniquely predict trust in charitable entities.

The knowledge of subjective perception is important because donors necessarily make decisions based on their perception of nonprofits’ practices, not based on the practices per se. If financial disclosure actually occurs, but is not fully perceived by donors, then the link between objective disclosure practices and donor behaviour may be weakened or even broken; mutatis mutandis for the objective performance of nonprofits and donor perception of that performance.Footnote 1 Thus, this study examines underexplored relationships between donor perception of nonprofit financial transparency, trust, and perceived nonprofit performance. The conceptual model expounded below posits relationships between these constructs; furthermore, structural equation modelling using 2017 survey data from 400 responses is conducted to empirically test hypotheses derived from this model. The findings show significant positive associations between (1) perceptions of financial transparency and perceived performance, (2) perceived financial transparency and donor trust, and (3) donor trust and perceived performance.

In addition to extending the nonprofit literature on donors’ perceptions and adding a fresh perspective to the growing body of work on nonprofit transparency, this study should be of interest to regulators and stakeholders with the ability to influence not just nonprofit accountability and transparency practices per se, but donor perceptions thereof. The findings can be valuable to nonprofits in developing strategies aimed at legitimising their operations and improving perceptions of their performance.

The paper is structured as follows: it sets out the conceptual framework, outlines the hypotheses, and then describes the research method and results. Finally, it discusses the findings, along with implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses

We are interested in the relations between perceived financial transparency, donor trust, and perceived performance of nonprofits. As with any principal-agent relationship, the problem of asymmetric information arises in the nonprofit sector: donors (principals) lack perfect knowledge of the decisions and operations of the nonprofits (agents). So, donors cannot be certain that nonprofits will always act in accordance with their professed missions. This can be a problem if agents are self-interested and their goals do not perfectly align with those of principals, as is often the case with for-profit organisations (Akerlof 1978). However, nonprofits are different to for-profit organisations in two fundamental ways. First, the primary purpose of nonprofits is to pursue a social purpose rather than profit or revenue maximisation. Second, nonprofits have a non-distribution constraint: they have no residual claimants and are legally prohibited from sharing any surplus. For the purposes of this paper, nonprofits are defined in this broad way. As such, all sorts of organisations may fall within its ambit (ranging from charities to research institutes to sporting clubs), as long as they do not have a profit imperative and do not disburse any surplus to management or shareholders.

It is commonly presumed that nonprofit managers will not pursue their self-interest and will allocate resources in line with donors’ expectations (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017). On the other hand, nonprofits rarely seek to close the information gap between themselves and their donors (Ghoorah 2017), and periodic scandals involving fund misappropriation by nonprofit managers indicate abuse of these asymmetries (e.g., Brockbank and Beattie 2022; Hargrave 2022). These scandals do not appear to have permanent widespread negative effects on trust and confidence in the sector (Chapman et al. 2021a). Nonetheless, scandals do elicit a ‘moral disillusionment effect’, which undermines trust in individual nonprofits to a greater extent than for profit-driven companies (Chapman et al. 2022). Crucially, this negatively impacts their donations (Chapman et al. 2021b). What place does perceived financial transparency have in this story? Can perceived financial transparency of nonprofits impact on both donors’ trust and perceived performance of nonprofits? In seeking to answer these questions, we posit the following relationships: First, perceived financial transparency positively and directly impacts donors’ perceptions of nonprofit performance. Second, perceived transparency positively affects donors’ trust, and their trust is positively associated with perceived performance.

Transparency-performance link

Nonprofits can use various metrics to be transparent about their efficiency and performance. Yang et al. (2017) found institutional donors to be interested in organisational performance as a means of distinguishing expected and actual outcomes. It is reasonable to assume that small individual donors would have a similar interest in such information so that they too can make informed donation decisions. While comprehensive qualitative non-financial and quantitative financial accountability and transparency are, in principle, ideal, in practice there can be problems with the use of non-financial reporting.

First, there is the possibility that donors might be overwhelmed by too many signals of performance, leading to information overload (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017). Second, because qualitative non-financial information can be heterogeneous and incommensurable, and does not have a standardised format for reporting, donors may be uncertain about the overall performance of a nonprofit despite receiving this information (Yang et al. 2017). Indeed, individual donors could perceive overwhelming and/or unintelligible disclosures as de facto non-disclosure. By contrast, financial disclosures are in principle relatively easy to compare because they are quantitative, have a standardised format, occur regularly, and generally adhere to well-known accounting standards and methodologies. Financial disclosures thus tend to be deemed trustworthy because of these characteristics of standardisation, conformity, and reliability (Cordery and Baskerville 2011). Further, although they are certainly limited in their scope, financial disclosures do contain information that is valuable to donors’ assessment of nonprofit performance with respect to mission outlays and non-mission-related expenses.

Given that financial transparency is perceived to be a relatively reliable and accurate, if limited, form of performance disclosure to donors, there is a prima facie link between perceived financial transparency and perceived performance. With more financial information at donors’ disposal, the problem of asymmetric information between nonprofits and donors is reduced: donors’ risks are reduced because they are better able to assess the performance of nonprofits with respect to their expenditure and mission goals. Without such transparency, donors would be largely ignorant of nonprofits’ operations, less able to assess the performance of nonprofits, and therefore, be less likely to perceive nonprofits’ performance favourably. Indeed, donors who may not fully understand financial disclosures (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017) may interpret a lower perceived level of transparency as an indication of poor performance being hidden by the nonprofit. On the other hand, higher perceived transparency may indicate that performance is ‘on track’ and striving to achieve its mission (Dhanani and Connolly 2012; Harris and Neely 2018).

Transparency-trust-performance links

As Yates et al. (2021) have pointed out, transparency and trust are fundamentally intertwined. We argue that donor trust in a nonprofit is garnered by demonstrating legitimacy via financial transparency. Organisation legitimacy – a generalised perception that the actions of an organisation align with expected social ‘norms, values, beliefs, and definitions’ (Suchman 1995, p.574) – is widely regarded as being essential to the long-term sustainability of an organisation. As articulated by Yasmin and Ghafran (2021), there are different kinds of legitimacy: pragmatic, cognitive and moral. Pragmatic legitimacy, where the organisation fulfils direct exchanges with an immediate target group, represents the weakest form of legitimacy as it can be gained by engaging in activities that are favoured by powerful stakeholders only (for example, accounting practices that are seen favourably by government agencies, powerful donors, or lobbying networks). Cognitive legitimacy refers to the legitimacy gained by an organisation behaving in a way that is comprehensible – ‘when the organisation undertakes those activities which are proper and ‘making sense’ to society’ (Yasmin and Ghafran 2021, p.402). To achieve moral legitimacy, an organisation seeks to publicly demonstrate adherence to socially acceptable moral values. This type of legitimacy can be subdivided into three types: structural, where the organisation possesses characteristics deemed intrinsically worthy of support; procedural, where the organisation adopts best practices; and consequential, where the organizsation achieves acceptable outcomes (Suchman 1995).

Couched in terms of a principal-agent relationship, trust is a principal’s belief that the agent will fulfil its mutually understood promises to the principal (Yates et al. 2021). Trust is neither blind faith nor probabilistic ‘confidence’ (Sargeant and Lee 2002). In the case of impersonal relations between a principal and agent, the grounds for an agent’s trust lie with the perceived veridical legitimacy of the principal. So, to garner trust, an agent-organisation must publicly demonstrate pragmatic, cognitive, and moral legitimacy to agents. This can be achieved by public-facing activities and documentation – or in other words, by transparent practices of accountability. Indeed, Yasmin and Ghafran (2021, p.401) go so far as to define accountability as the ‘process of managing, navigating, and nurturing legitimacy.’ Generally, when the legitimacy of an organisation is threatened, it adopts restorative strategies, and this often involves greater transparency via disclosures (Suchman 1995) since this is symbolic of a professional, well-structured organisation (Harris and Neely 2018). It is thus reasonable to expect nonprofits to be strategic in their transparency (via disclosures) to enhance their legitimacy. This aligns with Connolly and Hyndman’s (2013, p.259) finding that nonprofits view the provision of formal information as ‘having significance’ and serving as ‘an important legitimising tool’.

Thus, we posit that perceived financial transparency of nonprofits is an important legitimisation strategy (Dhanani and Connolly 2012; Saxton et al. 2012), and it is perceived legitimacy that engenders donor trust in a nonprofit. When an agent is transparent with its principal about its operations and its achievements (as well as its failures), it provides evidential grounds for greater trust in it. We suggest that this epistemic logic holds for nonprofits. Specifically, nonprofits which are perceived to engage in acts of financial transparency via financial disclosures, signal their legitimacy (cf. Dhanani and Connolly 2012; Saxton et al. 2012) and thus elicit greater trust that they will act in accordance with their social mission (Yang and Northcott 2019). (Concomitantly, a failure to be financially transparent would tend to lead to donor suspicions – a loss of trust – about whether a nonprofit is properly allocating its resources to its social mission.) Indeed, even if small donors are not overly interested in a detailed engagement with financial reports, then it is possible the sheer perception of the existence of financial disclosures engenders trust that the nonprofit is serving its mission adequately. In short, donors’ perceptions of performance are positively affected by their trust in the disclosing nonprofit (Yates et al. 2021).

In all the above, we focus on perceived financial transparency, trust, and perceived performance to emphasise the perspective of donors, rather than on the objective behaviour of nonprofits. In sum, we posited two kinds of pathways linking perceived nonprofit financial transparency and perceived nonprofit performance. First, donor perception of performance is directly linked back to their perception of financial transparency. If donors perceive nonprofits to be financially transparent, they will be better informed about the performance of these organisations and will be more likely to perceive such performance favourably compared to financially opaque nonprofits. Second, donor perception of nonprofit performance is indirectly linked back to their perception of financial transparency via trust; that is, trust functions as the bridge between perceived transparency and perceived performance: (a) If donors perceive a nonprofit to be financially transparent, this signals organisational legitimacy which engenders donor trust; and (b) this trust has a favourable impact on donor perception of the organisational performance. The empirical hypotheses arising out of this conceptualisation are:

Hypothesis (H1): There is a positive relationship between donor perception of nonprofit financial transparency and their perception of nonprofit performance.

Hypothesis (H2): There is a positive relationship between donor perception of nonprofit financial transparency and their trust in nonprofits.

Hypothesis (H3): There is a positive relationship between donor trust in nonprofits and their perception of nonprofit performance.

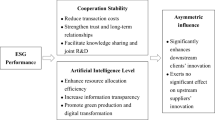

Diagrammatically, the three hypotheses can be represented as follows (Fig. 1).

Methods

Study context and data collection

Data was collected from the Australian nonprofit sector, a sector which is large and diverse with around 600,000 organisations, including over 60,000 charitiesFootnote 2 registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission (ACNC) (ACNC 2024)Footnote 3. The charitable sector employs 10.5% of the Australian labour force, receives $200 billion annual revenue to cover over $195 billion of expenses (including $108 billion in employee costs, and $74 billion in rent, fundraising expenses, administration, grants and donations), and contributes to social welfare across 864 program classifications (including health, education, social welfare, human rights, religion, animals and environment) (ACNC 2024). More than 51% of Australian charities are extra small and small (i.e., receive less than $250,000 in annual revenue) and less than 5% of charities are very large and extra-large (i.e., receive between $10 million and $100 million in annual revenue). While the sector as a whole is heavily reliant on individual donations ($13.9 billion in 2023, of which the top 30Footnote 4 charities and group received 20%) and volunteering (3.5 million volunteers), extra small charitiesFootnote 5 are almost entirely dependent on these resources (88% of extra small charities have no paid staff and receive only 0.1% of the sector’s income) to operate (ACNC 2024). Given links between perceptions of financial disclosures and donation intentions (Ghoorah et al. 2021) and the dependence of the sector on volunteering and donations, it is essential to understand relationships between individual donors’ perceptions of nonprofits (including charities), financial transparency, and performance.

A survey questionnaire was used to collect data. In the second half of 2017, 1305 random individuals across Australia were emailed an invitation with the survey link (no incentive was provided). The sample was restricted to individuals residing in Australia with an initial screening question (Are you an Australian resident?). Within a week, 465 participants had completed the survey. After removing responses with incomplete data (45) and responses with missing demographic information (20), an effective sample of 400 responses, representing a response rate of 32.25%, was finalised.

Roughly an equal number of males (51.25%) and females (48.75%) participated in the survey, and the sample was also roughly equally divided between donors (48.5%) and non-donors (51.5%). Most of the respondents were aged between 18 and 54 years (80.75%); half were employed (50.75%); 40% had a bachelor’s degree or higher; and 50% had at least 10 years of working experience. The respondents’ demographic characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Non-response bias

Non-response bias was assessed via wave analysis (Armstrong and Overton 1977). The sample was divided into the first and last 200 responders (following Baah-Peprah et al. 2024). Table 2 illustrates the significance of differences between the two waves of respondents for demographic factors. No evidence was identified for significant non-response bias in the sample.

Normality check

To check for normality of the data set, several tests were applied, including the Shapiro and Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS), Skewness, and Kurtosis tests, as well as graphical methods (namely, P-P plots and histograms). The data follows a normal distribution.

Constructs and measurements

The survey instrument consisted of the measurement scale items for the constructs covered in the theoretical model and respondents’ demographic details. The questionnaire gave a broad definition of nonprofits: ‘Not-for-profit organisations include social clubs, research institutes, education and training institutions, charities, culture and art organisations, libraries and museums’. This definition refers to examples of types of nonprofits, rather than the legal definitions used by regulators. During the pilot testing of the questionnaire, it became clear that laypeople related better to examples. For the three constructs, participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with item-statements using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). Higher scores were taken to be indicative of higher levels on each construct. The discrete response categories did not allow respondents to indicate partial scores. The statements or scale items were selected for their relevance and their plain, unambiguous language.

The constructs used in this study were measured using scales adapted or created based on existing literature. The five items for ‘Perceived financial transparency’ were modified from Piotrowski and Van Ryzin (2007) and Cho et al. (2009). The scale included items such as, “It is important to be able to get any financial statement information you want from a not-for-profit organisation,” “The public, in general, has a right to know about everything a not-for-profit organisation does,” and “Every member of the public should have complete access to information about not-for-profit organisations.” A three-item ‘Trust’ scale was adapted from Stanaland et al. (2011) which included “I believe the financial information provided by Australian not-for-profit organisations,” “Australian not-for-profit organisations do not make false claims” and “I trust Australian not-for-profit organisations to be frank” items. ‘Perceived performance’ was measured with a seven-item scale adapted from Dellaportas et al. (2012). Sample items of the scale included: “Financial information which provide assurance that the not-for-profit organisation is effective in achieving the results intended,” “Financial information which show that the not-for-profit organisation spends on its agreed objectives,” and “Financial disclosures which show the net surplus/loss of the not-for-profit organisation (revenue minus loss)”. Table 3 summarises constructs, indicators and their loadings.

Measurement model

AMOS Version 23 (Arbuckle 2014) was used to evaluate the fit of both the measurement model and the structural model. To validate the measurement model, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was first conducted using Principal Axis Factoring with Promax rotation. Three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained. The EFA revealed a three-factor structure that explained 68.32 of the total variance. Items with factor loadings above 0.50 were retained for further analysis.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was then performed to test the factor structure obtained from EFA. All standardised factor loadings were significant and exceeded 0.70, indicating strong item reliability to evaluate the distinctiveness of the scales used in this study. Model fit was assessed using various goodness-of-fit indices. As shown in Table 4, the chi-sqare statistic was significant (χ2 = 278.024, df = 87, p < 0.001), which is expected with larger sample sizes. The CFI and TLI values were 0.952 and 0.943, respectively, both exceeding the threshold of 0.90, indicating an acceptable fit (Bagozzi and Yi 2012). Additionally, the RMSEA value was 0.074, which is below the recommended cut-off of 0.08, and the SRMR value of 0.036 was also below 0.08, suggesting a good fit. The normed χ2/df ratio of 3.196 slightly exceeds the recommended range of 1 to 3 (Marsh and Hocevar 1985). However, as suggested by Bentler (1990), this does not automatically indicate poor model fit. Complementary fit indices, such as CFI and TLI, should be considered to provide a broader perspective on model adequacy.

Validity and reliability

In order to assess the reliability and validity of the constructs, Cronbach’s Alpha, Composity Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values were calculated. As shown in Tables 5 and 6, all constructs exceeded the recommended threshold values of 0.70 for Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability ranged from 0.86 to 0.93. Convergent validity was assesses through the AVE, with all constructs achieving values greater than 0.50, demonstrating the constructs captured more than half of the variance in their indicators (Hair et al. 2010). Discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ration (HTMT) as recommended by Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt (2015). The HTMT values for all construct pairs were below the threshold of 0.85, indicating sufficient discriminant validity.

Common method bias

We used the CFA marker technique to test for the presence of common method variance (Williams et al. 2010). Results indicated that method effects were present, but not problematic. The chi-square difference test between the Baseline model and the Method-C model indicated that the two models were significantly different from one another (χ²diff = 85.55, Δdf = 1, p < 0.05). Additionally, a comparison of the Method-C and Method-U models indicated that the impact of the method variable was not the same for all the items (χ²diff = 146.48, Δdf = 18, p < 0.05). The Method-U model showed that nine of the 20 items were contaminated by a source of common method variance captured by the marker variable, with a median value of 0.18. As the square of these values indicates the percentage of variance in the factors associated with the marker variable, the median amount of marker variance in each factor was only 3%. This indicates that common method variance was not a serious problem (Williams et al. 2010).

Results

The proposed structural model was estimated following Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988) two-step approach. In the first step, all construct items were analysed in a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to assess the construct validity of the measurement model. In the second step, structural models were run with clean measures to test the hypothesised model.

Hypothesis testing (path analysis)

Path analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between perception of financial transparency and performance, perception of financial transparency and trust, and trust and performance, as outlined in the three hypotheses. The result in Table 5 provided support for all proposed hypotheses.

Donor perception of financial transparency was positively related to donor perception of nonprofit performance (β = 0.632, p < 0.001), supporting H1. Donor perception of nonprofit financial transparency was positively associated with donor trust in nonprofits (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), supporting H2. Finally, donor trust in nonprofits was positively associated with donor perception of nonprofit performance (β = 0.36, p < 0.001), thus supporting H3. Squared multiple correlations were also assessed. Overall, the model explained approximately 66% of the variance in perceived performance owing to trust as opposed to approximately 12% due to transparency.

Control variables

To ensure the robustness of our results and eliminate the potential influence of confounding factors, we controlled for gender, age, education, tenure, and donor status to examine the model. Two separate models were tested – one excluding control variables and the other including them.

The results of the analysis showed that none of the control variables had a significant impact on financial performance except for education. Specifically, age was not significantly related to financial performance (β = 0.06, p > 0.05), gender (β = −0.026, p > 0.05), tenure (β = −0.018, p > 0.05), and donor status (β = −0.015, p > 0.05). Among all control variables, only education was found to be significantly related to financial performance (β = 0.118, p < 0.05). These results are reported in Fig. 2.

Model fit indices, and validity and reliability constructs for both models are presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. The results indicate that both models demonstrated acceptable fit to the data, as reflected by the reported indices. Specifically, the model excluding control variables had a chi-square value of 278.024 (degrees of freedom = 87), while the model including controls reported a chi-square value of 340.142 (degrees of freedom = 148). Both models yielded statistically significant p-values (p < 0.001), which is common in large sample sizes. The chi-sqare to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df) improved from 3.196 (without controls) to 2.98 (with controls), suggesting a better model fit with controls. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) decreased from 0.074 (without controls) to 0.057 (with controls), indicating improved model fit when controls were included. The standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) values were 0.036 and 0.034 for the models without and with control respectively, both of which fall within acceptable thresholds (<0.08). Both models exhibited strong comparative fit indices. The explanatory power, measured using R2 values, was consistent across both models. With control, the results R2 for performance was 0.669, and for trust, it was 0.168. which indicate a marginal increase in explanatory power for the model with controls, through the difference is minor.

Overall, the inclusion of control variables improved the model fit indices (e.g., lower RMSEA and χ2/df) and slightly enhanced the explanatory power. These results confirm that the key relationships in the model are consistent regardless of the inclusion of control variables, affirming the robustness of the main model and the conclusions drawn from it.

Additional analysis

A multi-group comparison (Byrne 2016) was conducted with two sub-samples of survey participants – ‘Donors’ (n = 196) and ‘Non-Donors’ (n = 204) – to check whether the sample variances and covariances from each sub-sample came from the same population in relation to the proposed model. This is consistent with invariant testing (e.g., Vandenberg and Lance 2000) by comparing an unconstrained model of variances and covariances of the measured variables to one in which the variances and covariances are constrained to equality across groups (not tabulated). Following chi-square test statistics for the nested model, the Δχ2 test between the unconstrained and measurement weights model (χ2(12) = 0.978, p = 0.467) was found to be insignificant. This further implies our variance-covariance matrices are equivalent across the sub-samples. Hence, the model had measurement and structural invariance for all parameter estimates and so no further tests were conducted (Vandenberg and Lance 2000). We also checked in case the ‘number of years of donor contribution’ had any effect on the proposed model. The result, however, did not find any significant relationship (β = 0.065, p > 0.05).

Discussion

Interpretations

The first major finding is that H1 was confirmed: a strong positive relationship exists between donor perception of nonprofit financial transparency and perception of nonprofit performance. Taking this finding to be indicative of a direct link, however, does not establish the precise mechanism involved. There are at least two possible interpretations of this direct link. One may be called a ‘calculative’ interpretation: donors make rational decisions based on a calculation of expected performance. If perceived performance of a nonprofit is conceptualised by donors as a function of stated mission outcomes relative to the risk of donations being used inappropriately, then in the donors’ calculus, greater financial transparency (that is, the provision of information impacting favourably on estimated risk) would translate into higher estimated perceived performance, ceteris paribus.

The other interpretation may be called ‘strategic’. It is based on the idea that donors believe the disclosures made by nonprofits are self-interested. As such, if donors believe that nonprofits use financial disclosures as a strategic means of publicising actual good performance, they tend to perceive those disclosures to be accurate signals of performance.Footnote 6 Conversely, if donors perceive low levels of financial disclosure as a signal of nonprofits strategically avoiding the publicising of performance, they will perceive the performance to have been poor. In this way, a link between perceived financial disclosures and perceived nonprofit performance is established.

Although both the ‘calculative’ and ‘strategic’ interpretations of the direct link between perceived financial transparency and perceived performance are plausible, they are both premised on the assumption that the primary function of financial disclosures is informational (thereby mitigating the asymmetric information problem). However, we also know from previous studiesFootnote 7 that at least some donors may not be interested in nor fully understand the details of financial statements. For these donors, the above explanations of the link are prima facie inadequate: donors who are uninterested in and/or unable to comprehend formal disclosures cannot make calculative or strategic assessments of performance based on the information contained in financial statements. For this reason, another pathway linking perceived financial transparency and perceived performance is required. This pathway, via the bridge of donor trust, was captured by H2 and H3.

The second major finding is that H2 was confirmed: there is a strong positive relationship between donor perception of nonprofit financial transparency and trust in the organisation. This supports the contention that perceived financial transparency can have a powerful impact in convincing donors of the legitimacy of a disclosing nonprofit (Dhanani and Connolly 2012), which in turn engenders trust.

This entails a qualitatively different interpretation to the calculative and strategic interpretations given for H1. For H2, we posit that financial disclosures by nonprofits serve another purpose: a performative function wherein financial disclosures are perceived as signalling or ‘performing’ legitimacy. Perceived disclosures (a) give pragmatic legitimacy to a nonprofit by indicating a willingness to be accountable to key stakeholders, including charity regulators. They (b) facilitate cognitive legitimacy by disclosing the basic purposes of fund allocation. Lastly, (c) perceived disclosures give moral legitimacy to the nonprofit, especially in its procedural dimension by conforming to socially recognised or regulated accounting norms, and in its consequential dimension by demonstrating effort to achieve its mission (cf. Yasmin and Ghafran 2021). When a nonprofit can achieve such manifold legitimacy, donors are more likely to trust that it will honestly strive to achieve its promissory mission by using its donations in a manner that is not wasteful or ethically dubious (Yates et al. 2021). Conversely, a nonprofit that fails to performatively indicate its manifold legitimacy through the signal of financial disclosure is likely to be less trusted by current and potential donors.

The third major finding is that H3 was confirmed: there is strong empirical support for a positive relationship between donors’ trust in a nonprofit and their perception of nonprofit performance. In the absence of perfect knowledge, if donors come to trust that a nonprofit is pragmatically, cognitively, and morally legitimate, they are likely to form affirmative presumptive perceptions of a nonprofit’s current and future performance. Conversely, if donors have lower levels of trust in a nonprofit, they are likely to presumptively perceive its performance poorly. All this is to say that trust in a nonprofit has a causal impact on perceptions of its performance (potentially irrespective of actual performance).

Considering the interpretations of the findings regarding H2 and H3 together, it is possible that the perception of the existence of financial disclosure reports, regardless of their informational content, acts as a performative signal to donors of nonprofit legitimacy. This, in turn, fosters trust that the nonprofit is using its donated funds appropriately and is serving its mission adequately. In other words, donors’ perceptions of performance are positively influenced by their trust in the nonprofit.

Finally, the results indicated that the control variable of education was significantly positively related to perceived financial performance. A possible explanation for this, which coheres with the hypotheses, is this: it is possible that individuals with higher education levels are more likely to have greater financial literacy, which would enable them to interpret financial transparency disclosures, leading to a more informed and favourable perceptions of nonprofit financial performance. Further, more educated individuals may have higher expectations for transparency and accountability. If they perceive a nonprofit to be financially transparent, they might be more inclined to trust the organisation and assess its performance favourably.

Implications

An obvious implication of these findings is that nonprofits can benefit from being perceived as financially transparent. Perceived transparency of a nonprofit’s financial situation offers two main advantages: (1) it provides donors with valuable information with which they can make more informed (less risky) decisions, and (2) it gives a nonprofit legitimacy which engenders donor trust – both of which favourably influence donors’ perceptions of nonprofit performance. If donors have a positive perception of a nonprofit’s performance, the organisation is more likely to retain, and perhaps increase, donor patronage, thereby providing the basis for its financial sustainability (Saxton et al. 2012).

Given the benefits of financial transparency, an argument could be made for voluntary self-regulation by nonprofits. This argument is a variation on the general free market argument advanced by some economists (e.g., Jones 1995), wherein nonprofits perceived to be financially transparent will establish superior reputations to those that don’t. Risk-averse donors will shift their donations to transparent nonprofits. Opaque nonprofits either must become financially transparent too or be driven out of the ‘market’ due to loss of donations. On this argument, in the long run, all surviving nonprofits will be voluntarily transparent.

The chief problem with this argument is that ‘the long run’ is a theoretical idealisation. The real ‘market’ for donations is populated by nonprofits with differing levels of legitimacy and response capacities, and thus heterogeneous ‘lag times’ in reacting to changes in donation income. Further, new nonprofits are continually entering the market, and will necessarily go through a process of discovering the important links between perceived disclosures, trust, perceived performance, and donations. The length of this process cannot be known a priori and is likely to be variable. Further, although major institutional donors may be able to exert pressure on nonprofits to improve transparency, this need not always occur; and such pressure does not necessarily translate into transparency for small individual donors. Small donors simply do not possess the power to demand financial transparency that serves their needs (Yang et al. 2017). This means, at best ‘market forces’ only imperfectly and unevenly ‘discipline’ nonprofits. It is thus not unsurprising that in fact there is often a lack of voluntary financial transparency within the nonprofit sector (Ghoorah 2017). Nor is it surprising that scandals of misappropriation, embezzlement, and mismanagement periodically occur (e.g., Brockbank and Beattie 2022; Hargrave 2022). As such, there are grounds for skepticism about the market’s capacity to systematically transmit to nonprofits the message that perceived transparency is important to their financial sustainability (Ghoorah et al. 2021). In short, the hope of universal, voluntarily self-imposed financial transparency by nonprofits seems unrealistic.

We therefore believe that policy makers and regulators have a responsibility to impose sectoral requirements on nonprofits to be financially transparent as the first step to signalling a nonprofit’s legitimacy. Indeed, this is precisely what has happened in several countries, where regulatory agencies have adopted various strategies to build trust through accountability and transparency. These approaches include a mix of enforcing regulatory compliance, educating nonprofits about accountability, and actively engaging in trust-building efforts with the public (Yang and Northcott 2021). Yet despite these efforts, the nonprofit sector continues to struggle to achieve public trust via accountability and transparency (Hyndman and McConville 2018). This might be because the focus of regulators is on formal transparent accountability per se, without giving due consideration to donors’ perceptions of transparency. We know, for instance, that donors often have a limited appreciation or understanding of disclosures imposed by accountability requirements, such as standardised financial disclosure statements (Connolly and Hyndman 2013; Ghoorah et al. 2017).

To improve perceptibility of transparency, regulatory bodies should consider prescribing and monitoring the language and formats of disclosure statements to non-specialist audiences (Yang and Northcott 2019). By using clear, non-technical language and formats that do not ‘overload’ donors with extraneous detail, nonprofits’ financial disclosure statements would be more likely to be understood by donors, thereby garnering a favourable perception of disclosure (Ghoorah et al. 2017). This may further enhance donor perception of nonprofit performance through both the direct and indirect links discussed in this paper. In brief, highly cognitively accessible financial statements may: (1) decrease the level of asymmetric information and uncertainty inherent in the donor-nonprofit relationship, thereby improving calculative perceptions of nonprofit performance. They may also (2) signal legitimacy and secure donors’ trust, which in turn elicits favourable perceptions of nonprofit performance.

Limitations and further research

This study contributes to the nonprofit literature by focusing attention on donors’ perceptions, rather than organisations’ standards and practices per se. Both are important, but the former has been relatively neglected compared to the latter. There is still much to be done on this topic, and its limitations may provide direction to future research.

First, due to the atemporal nature of the data used in this study, we were unable to empirically test causal relationships between the key variables. Instead, we offered tentative, plausible causal interpretations of the observed associations, based on the conceptual framework outlined in section 2 and discussed in section 5. Although we consider these interpretations plausible, future research could address this limitation by using panel data (cross-sectional time-series).

Second, in this paper, respondents did not distinguish between charity nonprofits and non-charity nonprofits. It is possible that donors might discriminate between them, which could give rise to heterogeneous results between these two subgroups. Future studies could explore whether donors’ perceptions differ between these two subgroups and perhaps other more fine-grained divisions (such as small, medium, and large nonprofits, or religious versus non-religious charities).

Third, this paper has not explored functional forms of the relationships between perceived transparency, trust, and performance. For example, a simple linear relationship between perceived disclosure and donor trust in a nonprofit seems prima facie implausible. One might hypothesise that at some level of perceived disclosure, marginal positive increases in trust would start to diminish and perhaps even reach a saddle point. This possibility is apposite in light of the possibility that individual donors could experience ‘information overload’ (Tremblay-Boire and Prakash 2017).

Fourth, this paper has restricted itself to the impact of perceived financial transparency. This is because non-financial transparency is difficult to report in a systematic and rigorous manner (Yang et al. 2017). At present, there are no standardised guidelines and formats for the reporting of non-financial information, which renders such information inconsistent across nonprofits. None the less, future research could seek to develop a metric for making inter-nonprofit comparisons of perceptions of non-financial transparency. This metric could then be incorporated into a conceptual model to empirically explore its effects on perceptions of broader notions of nonprofit performance. This may also enable exploration of the potential causal impact of non-financial disclosure versus financial disclosure on donor trust and perceived performance.

Conclusion

This study provides empirical evidence that donors’ perceptions of financial transparency positively influence their perceptions of nonprofits’ performance. It suggests that greater perceived transparency (1) reduces donor informational asymmetry and uncertainty, and (2) signals legitimacy, building donor trust. Both (1) and (2) contribute to improved donor perceptions of nonprofit performance. Given that nonprofits often provide limited financial disclosures, which unnecessarily increase donor uncertainty and weaken their legitimacy, the nonprofit sector would benefit from enhancing perceived financial transparency.

If, as we propose, the nonprofit ‘market’ cannot voluntarily achieve sufficient financial disclosure, regulators should consider imposing more stringent transparency requirements on nonprofits for the collective good of the sector. Importantly, these regulations should ensure that financial disclosures are both clear and informative to all donors.

Data availability

The dataset used for this study is available in the attached supplementary file.

Notes

There is a variety of motives for which individual donors support nonprofits. However, if these donors were to distrust a charity, these motives are immaterial as one is not going to support an organisation they do not trust.

Data within the rest of the paragraph relate to the Australian charitable sector only as, at the time of the study, these data are only available about registered charities.

Based on the Productivity Commission Report (2010), being the most recent report on the nonprofit sector. The next report is expected to be released next year.

In terms of revenue size.

Extra Small charities have an annual total revenue of less than $50,000, while small charities earn between $50,000 and $250,000 (ACNC 2024).

Such a belief on the part of donors would not be unreasonable. Yang and Northcott (2018) found that organisations use disclosures of favourable or superior performance to demonstrate they acted as per donors’ positive expectations.

References

ACNC (2024) Australian Charities Report. 10th ed. Australian Government. https://www.acnc.gov.au/tools/reports/australian-charities-report-10th-edition

Agyemang G, O’Dwyer B, Unerman J (2019) NGO accountability: retrospective and prospective academic contributions. Account Auditing Account J 32(8):2353–2366. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2018-3507

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural Equation Modelling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychological Bull 103(3):411–423

Arbuckle JL (2014) AMOS (Version 23.0) [Computer program]. IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL

Armstrong JS, Overton TS (1977) Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J Mark Res 14(3):396–402

Akerlof GA (1978) The market for”lemons”: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Uncertainty Econ, 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-214850-7.50022-X

Bentler PM (1990) Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bull 107(2):238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Baah-Peprah P, Shneor R, Munim ZH (2024) “In this together”: on the antecedents and implications of crowdfunding community identification and trust. Venture Capital, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2024.2310232

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (2012) Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 40(8):8–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0278-x

Brockbank N, Beattie S (2022) Toronto charity staff want ‘justice’ after former boss allegedly misappropriated $365K’ CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-charity-staff-under-investigation-1.6346655

Byrne BM (2016) Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed. New York, Routledge

Chapman CM, Hornsey MJ, Gillespie N (2021a) No global crisis of trust: a longitudinal and multinational examination of public trust in nonprofits. Nonprofit Voluntary Sect Q 50(2):441–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020962221

Chapman CM, Hornsey MJ, Gillespie N (2021b) To what extent is trust a prerequisite for charitable giving? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nonprofit Voluntary Sect Q 50(6):1274–1303. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640211003250

Chapman CM, Hornsey MJ, Mangan H, Gillespie N, La Macchia S, Lockey S (2022) Comparing the effectiveness of post-scandal apologies from nonprofit and commercial organizations: an extension of the moral disillusionment model. Nonprofit Voluntary Sect Q 51(6):1257–1280. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640211062666

Cho CH, Phillips JR, Hageman AM, Patten DM (2009) Media richness, user trust, and perceptions of corporate social responsibility: an experimental investigation of visual web site disclosures. Account Auditing Account J 22(6):933–952. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570910980481

Connolly C, Hyndman N (2013) Charity accountability in the UK: through the eyes of the donor. Qualitative Res Account Manag 10(3-4):259–278. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-02-2013-0006

Cordery CJ, Baskerville RF (2011) Charity transgressions, trust and accountability. VOLUNTAS Int J Voluntary Nonprofit Organ, 22(2):197–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-010-9132-x

Daff L, Parker LD (2021) A conceptual model of accountants’ communication inside not-for-profit organisations. Br Account Rev 53(3):100959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2020.100959

Dhanani A, Connolly C (2012) Discharging not‐for‐profit accountability: UK charities and public discourse. Account Auditing Account J 25(7):1140–1169. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571211263220

Dellaportas S, Langton J, West B (2012) Governance and accountability in Australian charitable organisations: perceptions from CFOs. Int J Account Inf Manag 20(3):238–254. https://doi.org/10.1108/18347641211245128

Farwell MM, Shier ML, Handy F (2019) Explaining trust in Canadian charities: the influence of public perceptions of accountability, transparency, familiarity and institutional trust. VOLUNTAS Int J Voluntary Nonprofit Organ, 30(4):768–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-00046-8

Ghoorah U (2017) Factors influencing the extent of accounting disclosures made in the annual reports of publicly reporting Australian not-for-profit organisations. Doctoral dissertation. Western Sydney University (Australia). http://hdl.handle.net/1959.7/uws:44081

Ghoorah U, Khan AM, Garrow NS (2017) Financial disclosures and calls for greater transparency in the Australian NFP sector. Pro Bono Australia Newsletter. https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2017/10/financial-disclosures-calls-greater-transparency-australian-nfp-sector/

Ghoorah U, Talukder AMH, Khan A (2021) Donors’ perceptions of financial disclosures and links to donation intentions. Account Forum 45(2):142–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2021.1872892

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2010) Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall

Hargrave R (2022) Inquiry into animal charity that has failed to file accounts for five years. Third Sector. https://www.thirdsector.co.uk/inquiry-animal-charity-failed-file-accounts-five-years/governance/article/1791160

Harris EE, Neely D (2018) Determinants and consequences of nonprofit transparency. J Account Auditing Financ 36(1):195–220. 10.1177%2F0148558X18814134

Hengevoss A (2023) Comprehensive INGO Accountability to Strengthen Perceived Program Effectiveness: A Logical Thing? VOLUNTAS Int J Voluntary Nonprofit Org, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00556-0

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43:115–135

Hyndman N, McConville D (2018) Trust and accountability in UK charities: exploring the virtuous circle. Br Account Rev 50(2):227–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2017.09.004

Jones TM (1995) Instrumental Stakeholder Theory: A Synthesis of Ethics and Economics. Acad Manag Rev 20(2):404–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/258852

Lancksweerdt L, Van Caneghem T, Reheul AM (2023) Mandatory Financial Statements Disclosure and Nonprofits’ Debt Structure: An Empirical Analysis. VOLUNTAS: Int J Voluntary Nonprofit Organ, 34:787–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00516-0

Marsh HW, Hocevar D (1985) Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: first- and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychological Bull 97(3):562–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.97.3.562

Piotrowski SJ, Van Ryzin GG (2007) Citizen attitudes toward transparency in local government. Am Rev public Adm 37(3):306–323. 10.1177%2F0275074006296777

Ricketts A (2021) Charity pay study 2021 – The biggest earners. Third Sector. https://www.thirdsector.co.uk/charity-pay-study-2021-biggest-earners/management/article/1713966

Sargeant A, Lee S (2002) Individual and contextual antecedents of donor trust in the voluntary sector. J Mark Manag 18(7–8):779–802. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257022780679

Saxton GD, Kuo JS, Ho YC (2012) The determinants of voluntary financial disclosure by nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Voluntary Sect Q 41(6):1051–1071. 10.1177%2F0899764011427597

Stanaland AJS, Lwin MO, Murphy PE (2011) Consumer perceptions of the antecedents and consequences of corporate social responsibility. J Bus Ethics 102(1):47–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0904-z

Suchman MC (1995) Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional approaches. Acad Manag Rev 20(3):571–610. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080331

Tremblay-Boire J, Prakash A (2017) Will you trust me?: how individual American donors respond to informational signals regarding local and global humanitarian charities. VOLUNTAS Int J Voluntary Nonprofit Organ, 28(2):621–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9782-4

Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE (2000) A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ Res Methods 3(1):4–70. 10.1177%2F109442810031002

Williams LJ, Hartman N, Cavazotte F (2010) Method variance and marker variables: a review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organ Res Methods 13(3):477–514. 10.1177%2F1094428110366036

Yang C, Northcott D (2018) Unveiling the role of identity accountability in shaping charity outcome measurement practices. Br Account Rev 50(2):214–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2017.09.010

Yang C, Northcott D (2019) How can the public trust charities? The role of performance accountability reporting. Account Financ 59(3):1681–1707. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12475

Yang C, Northcott D (2021) How do charity regulators build public trust? Financial Account Manag 37(4):367–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12283

Yang C, Northcott D, Sinclair R (2017) The accountability information needs of key charity funders. Public Money Manag 37(3):173–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2017.1281649

Yasmin S, Ghafran C (2021) Accountability and legitimacy of non‐profit organisations: challenging the current status quo and identifying avenues for future research. Financial Account Manag 37(4):399–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12280

Yates D, Belal AR, Gebreiter F, Lowe A (2021) Trust, accountability and ‘the Other’ within the charitable context: UK service clubs and grant‐making activity. Financial Account Manag 37(4):419–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12281

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr Ushi Ghoorah (Corresponding Author) conceptualized the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and significantly revised subsequent versions. Ushi Ghoorah also reviewed the manuscript and finalized the submission. Dr Edward Mariyani-Squire provided critical insights and expert guidance on data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript for accuracy. Dr Sabreena Zoha Amin contributed to data analysis. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Western Sydney University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (Date of approval: 11 July 2017, No: H12309). In providing this approval, the HREC determined that the questionnaire and methodology meet the requirements of the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research.

Informed consent

Each participant was asked for their explicit consent at the start of the survey. The collected data were de-identified by the principal researcher (main author). The dataset is handled and stored strictly by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghoorah, U., Mariyani-Squire, E. & Zoha Amin, S. Relationships between financial transparency, trust, and performance: an examination of donors’ perceptions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 315 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04640-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04640-2