Abstract

The rise of scientific populism has become a global issue, but research on the coexistence of scientific elitism and scientific populism, especially in East Asian societies, is still limited. Based on a large-scale online survey conducted in the Chinese mainland in 2023 (N = 2922), this study explores the tendencies towards scientific elitism, scientific populism, and scientific pluralism among different groups in Chinese society. The results show that Chinese women tend to have a more conservative view of scientists, with no clear inclination towards elitism or populism. People with middle income and education levels show a dual tendency, supporting both elitist views and populism, and even leaning towards pluralistic attitudes. The “initial construction generation,” has a more negative view of scientific elitism and tends towards extreme populism, while the “new century generation” shows less deference for elitism and a stronger populist tendency. The study also finds that the interaction between post-materialist values and interest in science significantly shapes attitudes towards scientists. Social media, especially short-video platforms, plays an important role in promoting scientific populism and its more extreme forms. This study emphasizes the need to account for the diversity and complexity of attitudes across different social groups when developing science communication strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, particularly following the outbreak of COVID-19, subtle shifts have occurred in public attitudes towards scientists, including distrust (Mede, 2022), skepticism (Staerklé et al., 2022), and the acceptance of misinformation (Scheufele et al., 2021). These shifts are not confined to Western contexts (Butler, 2020; Kennedy et al., 2022; Wissenschaft im Dialog, 2024; UZH News, 2022; Elchardus & Spruyt, 2014) but are also evident in non-Western countries (Lasco, 2020; Mietzner, 2020). Scholars have employed various concepts to describe the evolving public attitudes towards scientists, including scientific populism (Mede & Schäfer, 2020), anti-intellectualism (Motta, 2018), conspiracy theories (Mahl et al., 2023), and the post-truth era (Sismondo, 2017). These studies have shed light on key characteristics of public perceptions of the role and function of scientists in society.

However, the existing body of research might have overlooked two critical aspects. First, while evidence of growing skepticism is clear, recent large-scale cross-national surveys suggest that overall societal confidence in scientists remains robust (Cologna et al., 2024; Edelman, 2024). This finding highlights two seemingly contradictory attitudes: scientific elitism, reflecting deference to scientists and their authority; and scientific populism, characterized by questioning and challenging scientific authority (we will elaborate on this in the conceptual framework section). Scientific elitism and scientific populism coexist globally, although in varying forms and degrees. For example, Guenther et al. (2018) observed in their study of the South African public that attitudes toward science and technology simultaneously reflected “promise” and “reservation,” a duality that can coexist even within specific subgroups.

More importantly, much of the current research relies on data from Western societies, with limited evidence from East Asia. Actually, scientific populism has also emerged in East Asian societies in recent years (Lü & Gao, 2024; Chen & Zhu, 2023; Fominaya, 2022; Rauchfleisch et al., 2023; Yokoyama & Ikkatai, 2022; Kim et al., 2017). However, in East Asia, Confucian cultural traditions that emphasize social order and deference to authority (Ma, Yang, 2014; Tan & Chee, 2005) have cultivated a high-power-distance society (Hofstede, 1984), where members often accept and expect authority (Zhai, 2022; Zhai, 2017). These traditions may provide some resilience against scientific populism; even in the face of skepticism, significant public deference to scientists often endures. From the perspective of cultural value theory, embeddedness reinforces the public’s identification of scientists as “guardians of collective interests,” while hierarchical structures strengthen trust in scientific authority. However, the rise of autonomous values among younger generations and the expansion of the internet and digital culture have created new spaces for the expression of scientific populism (Schwartz, 1992). This cultural tension has fostered the coexistence of scientific elitism and scientific populism in East Asia.

In China, deeply influenced by Confucian culture and its socialist system, there has been a long-standing deference and trust in various authorities, including scientific ones. Scientific elitism remains a dominant feature of public attitudes toward scientists. Surveys show that Chinese public evaluations of scientists have become increasingly positive from 2017 to 2021 (Ye et al., 2023), and trust in scientists is significantly higher than the global average (Cologna et al., 2024). However, scientific populism, similar to trends observed in Western societies, has also begun to surface in China. This populism manifests in skepticism and opposition to scientists, with greater trust placed in local knowledge or personal experiences (Lü & Gao, 2024; Chen & Zhu, 2023; Cheng & Shi, 2020; Fan, 2015). Several areas have seen direct or indirect conflicts between the public and scientists, particularly in the wake of frequent academic misconduct scandals (Greely, 2019), public protests against chemical projects like the “PX” incidents (Zhu, 2017; Lee & Ho, 2014), discussions surrounding PM2.5 (Li et al., 2021; Huang, 2015), debates over genetically modified foods (Qiu et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2020), and controversies over COVID-19 measures (Yuan et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2022; Luo & Jia, 2022). Since 2022, topics resonating with scientific populism, such as the slogan “Advice for experts: Never advise!” have frequently appeared on social media hotlists (Chen & Zhu, 2023; Lü & Gao, 2024).

Given this backdrop, our study seeks to move beyond a singular polarized perspective to explore the coexistence of scientific elitism and scientific populism in Chinese society. We analyze how demographic and attitudinal variables distinguish these attitudes and identify groups that may simultaneously support both—a phenomenon we refer to as “scientific pluralism.” This investigation aims to deepen the understanding of deference in scientists and its resilience, shedding light on how these seemingly contradictory attitudes coexist in different cultural contexts.

The paradox of high deference and gradual populism in China

In modern Chinese society, scientists are often shown in official discussions as examples of national progress and patriotism, enjoying a high social status. Celebrated figures such as Jiaxian Deng, the “Father of China’s nuclear weapons,” Xuesen Qian, a pivotal figure in China’s space program, Longping Yuan, the “Father of hybrid rice,” and Youyou Tu, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of artemisinin to treat malaria, epitomizes this esteem (Ye et al., 2023). The public image of scientists has remained relatively stable, often characterized by perceptions of strong capabilities and significant contributions to societal progress (He & Wang, 2009; Ye et al., 2023). This deference is echoed in social trust surveys, where trust in scientists ranks among the highest, second only to close interpersonal relationships such as family and friends (Xiang et al., 2015). During the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, public trust in scientists soared, reaching historic highs by 2021 (Chen et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2021; Ye et al., 2023).

Political imperatives during different historical periods have shaped official discourses on scientific elitism, influencing how the public perceives the roles and functions of scientists. For instance, in the 1950s, scientists were portrayed as models of unity and learning from the Soviet Union. Following the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s, the discourse shifted to emphasize independence and self-reliance, casting scientists as symbols of national resilience (Zhang, 2016). However, during the “Cultural Revolution” of the 1960s and 1970s, scientists and intellectuals were persecuted and subjected to ideological scrutiny, transforming them from revered figures into targets of criticism and re-education (Li & Guo, 2015). Since the reform and opening-up period, scientists have been reimagined as key drivers of economic development and technological innovation. Overall, official narratives have consistently reinforced a stance of scientific elitism, presenting scientists as patriotic, competent, and diligent figures (Wang & Xu, 2021). The Communist Party of China (2019) issued the “Opinions on Further Promoting the Spirit of Scientists and Strengthening Academic and Conduct Standards,” emphasizing the need to guide the public toward showing deference to scientists. During the COVID-19 pandemic, prominent medical scientists such as Nanshan Zhong and Lanjuan Li were portrayed as trusted and exemplary figures, symbolizing the alignment of scientific excellence with national unity (Zhong, 2020). The strong influence of this elitist discourse has been a key factor in sustaining the public’s long-standing deference to scientists in China.

Under the deep influence of the official scientific elitist discourse, the Chinese public has generally maintained high deference toward scientists (Cologna et al., 2024). However, in recent years, public evaluations of scientists have become increasingly negative (Ye et al., 2023), accompanied by a growing prominence of scientific populism and a gradual decline in unquestioning reverence toward scientific authority.

This shift is partly driven by scandals involving scientists. In recent years, high-profile cases of academic misconduct and ethical violations have undermined trust in the scientific community. For example, the 2018 “He Jiankui gene-edited babies incident” drew worldwide criticism for its ethical violations (Greely, 2019). Additionally, scandals involving sexual harassment and academic fraud have further eroded public trust in scientists (Chen et al., 2023). Such incidents have not only weakened scientists’ authority in knowledge production but also damaged their moral credibility in the eyes of the public.

Conflicts between scientists and the public have also emerged in areas such as environmental health, food safety, and public policy. The “PX” incidents, a series of public protests against paraxylene chemical projects, represent one of the few cases of active public participation in scientific issues (Zhu, 2017; Chin-Fu, 2013). Paraxylene, used in producing plastics and fibers, has raised public concerns due to its potential environmental and health risks, prompting widespread protests (Wang et al., 2022). Similarly, debates over genetically modified foods reflect public fears that scientists may prioritize economic or political interests over safety and necessity (Hu et al., 2020; Lü & Chen, 2016). During the pandemic, statements by Chinese scientists on issues such as the origin of the virus, vaccine safety, treatment protocols, and lockdown measures often faced skepticism. Many of these statements were criticized as unsubstantiated or detached from public concerns. On social media, many people mock experts as “brick experts” (磚家), which is the exact homophone of “expert” (專家) in Chinese, humorously implying that these individuals lack genuine expertise. Similarly, they refer to professors as “callous beasts” (叫獸), which is also the exact homophone of “professor” (教授) in Chinese, ironically suggesting that professors may not be as knowledgeable or compassionate as their title implies. Since 2022, slogans such as “Advice for experts: Never advise!” have frequently trended on platforms like Zhihu and Weibo (see Fig. 1), reflecting public dissatisfaction with expert opinions (Chen & Zhu, 2023; Lü & Gao, 2024). In the later stages of the pandemic, even scientifically substantiated claims faced significant public skepticism. In response, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (2023) issued a “Code of Conduct for Academicians (Trial)”, mandating that academicians refrain from publicly expressing opinions unrelated to their fields of expertise, aiming to preserve the authoritative discourse of scientists.

It is particularly worth noting that China’s media environment plays a critical role in both the rise of scientific populism and the persistence of scientific elitism. Traditional official media and digital media contribute differently to these phenomena, reflecting the tension between mainstream ideology and grassroots scientific discussions. Traditional official media, such as People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency, Guangming Daily, and China Central Television, function as transmitters of mainstream ideology by emphasizing the central role of science and technology in national modernization and by highlighting the contributions of scientists to the nation and society (Hassid, 2020). Additionally, these outlets employ innovative communication strategies, such as subcultural narratives, to engage younger audiences (Li et al., 2024).

In contrast, digital media provide a decentralized platform for public engagement with science, allowing individuals to participate in discussions and even challenge scientific authority. Platforms such as Zhihu and Bilibili, as well as social media like Weibo and Douyin, have facilitated the emergence of citizen science communicators—members of the public without formal scientific backgrounds who actively take on the role of science communicators (Yang, 2021). This “dissolution of boundaries” not only challenges the traditional notion of scientists as the sole legitimate creators of scientific knowledge but also fosters the deconstruction and diversification of scientific authority in the eyes of the public (Yang, 2022). Moreover, Chinese scientists generally do not regard science communication as part of their professional responsibilities (Jia et al., 2018), and their communication on social media often reflects a preference for one-way dissemination of knowledge rather than interactive engagement. This lack of interaction further strengthens public skepticism of authority on digital platforms (Jia et al., 2017).

In summary, we observe the widespread prevalence of scientific elitism in both official and public discourse in China, alongside the emergence of various topics and actions characterized by scientific populism. The complexity of public attitudes towards scientists motivates us to explore which groups within society are more likely to support scientific populism, which are more inclined toward scientific elitism, and, more intriguingly, which groups might simultaneously hold both attitudes. To address these questions, we propose the following research questions:

RQ1: Which groups in Chinese society are more likely to support scientific elitism or scientific populism?

RQ2: Which groups in Chinese society are inclined to support both scientific elitism and scientific populism (scientific pluralism)?

Conceptual framework and existing research

Scientific elitism, populism, and pluralism

We have frequently referred to two core concepts in this study, namely scientific elitism and scientific populism, which now require precise definitions to establish a conceptual foundation for subsequent analysis. These two concepts not only depict the complex dynamics between the public and scientists—characterized by deference and skepticism, authority and equality, participation and representation—but also reflect the public’s attitudes and perceptions toward scientists and the knowledge they produce. Scientific elitism typically manifests as deference to and trust in the professional knowledge of scientists, whereas scientific populism reveals public skepticism and challenges to scientific authority. These attitudes are not isolated; rather, they are interwoven and mutually influential within societal contexts.

Scientific populism has been a widely discussed concept, indicating public skepticism towards scientists and their knowledge. Mede and Schäfer (2020) were among the first scholars to conceptualize and measure this phenomenon, emphasizing the significant opposition between “ordinary people” and “academic elites.” Advocates of scientific populism argue that knowledge created by scientific elites is often criticized as unhelpful, ideologically biased, and lacking practical value (Ylä-Anttila, 2018; Eberl et al., 2021), and is thus considered inferior to the “common sense” of the public on a value level. The daily experiences and intuition of the public are sometimes considered more credible than the theories and data analysis of scientists (Mede et al., 2021). Based on this view, some people advocate that the production of knowledge should rely more on the public, whose moral positions are more neutral, rather than on scientists (Mede et al., 2022). To a certain extent, scientific populism is seen as a “thin ideology” (Rekker, 2021) that does not advocate a complete system of knowledge but challenges the existing scientific authority.

Elitism is theoretically the mirror image of populism (Mudde, 2004), yet in practice, the relationship between populism and elitism is often blurred. Scientific elitism reflects the public’s respect and trust in the professional knowledge and authoritative status of scientists. In this concept, scientists, with their profound professional knowledge and skills, are granted authority in the field of science that surpasses that of the general public. They are considered able to provide more accurate interpretations and predictions of scientific phenomena, and their opinions and judgments are generally regarded as having higher value and significance (Spruyt et al., 2023; Bertsou & Caramani, 2022). Scientists are seen as legitimate creators and disseminators of scientific knowledge in scientific elitism. It should be emphasized that this point of scientific elitism differs from scientism. Scientism advocates that science and scientific methods are the main, if not the only, ways to understand the world and reality (Stenmark, 1997), but does not emphasize the unique role and authority of scientists in scientific inquiry and knowledge construction.

Although scientific populism and scientific elitism are often viewed as opposing concepts, they are not entirely mutually exclusive in practice and may coexist in certain situations (Akkerman et al., 2014). In some cases, the public may simultaneously respect the professional knowledge of scientists and be skeptical of scientific research results. In addition, the public may recognize the authority of scientists in technical issues but believe that the opinions of ordinary people are equally important when applying scientific knowledge to social policies or moral decisions. In this paper, we regard this attitude as scientific pluralism.

Differentiating factors of public attitudes towards scientists

Our focus is on which groups are inclined to support scientific elitism or scientific populism, and even hold both seemingly contradictory attitudes toward scientists. While existing research has largely concentrated on Western contexts, it has revealed how factors such as social backgrounds and personal interests influence public attitudes toward scientists. However, the applicability of these theories in the Chinese context remains underexplored. In light of this, our study adopts an exploratory perspective, situating the analysis within China’s unique socio-cultural context, and focuses on how socio-demographic characteristics, personal values, and media use serve as critical factors that differentiate groups in their attitudes toward scientists.

Gender

Gender plays a role in differentiating individuals’ attitudes towards scientific elitism and scientific populism, although existing research findings are not consistent. Some studies suggest that men are more inclined towards attitudes of scientific populism (Ralph-Morrow, 2022; Spruyt et al., 2016; Kaltwasser & van Hauwaert, 2020), while women are more supportive of scientific elitism (Yokoyama & Ikkatai, 2022). However, there are also studies indicating that women are more likely to criticize science or scientists (Morgan et al., 2018; Evans & Hargittai, 2020), and higher-income men may be more inclined towards scientific elitism (Evans & Hargittai, 2020; Gauchat, 2012). In addition, some studies suggest that gender may not have a significant impact on attitudes towards science (Gauchat, 2011; Johnson et al., 2015).

Generation

Studies point out that older people tend to show more attitudes of scientific populism (Mede et al., 2022; Spruyt et al., 2016; Kaltwasser & van Hauwaert, 2020), while younger people are relatively more supportive of scientists (Funk et al., 2020). However, there is also evidence that older people may be more supportive of scientists (Evans & Hargittai, 2020), which may be related to their generally positive attitude towards social trust (Lunz Trujillo, 2022; Li & Fung, 2013; Poulin & Haase, 2015; Price & Peterson, 2023), while younger people usually have lower levels of social trust (Connaughton, 2020; Gramlich, 2019).

In fact, an individual’s attitude towards scientists may be profoundly influenced by the historical period in which they live. Therefore, generational analysis provides a more in-depth perspective than simply considering absolute age, revealing the shaping of a generation’s values by shared historical and cultural experiences. In China, rapid socio-political changes and economic development have led to significant differences in values between different generations (Gao et al., 2022). For example, the generation that experienced the Cultural Revolution may have developed a critical attitude towards scientists due to the devaluation of scientists’ status and the prevalence of populism during that era (Zhang, 2016; Li & Guo, 2015). At the same time, Generation Z, who grew up in an environment of highly developed internet and information technology, may influence their views on science and scientists with their open-mindedness and critical thinking (Brosius et al., 2022; Lazányi, 2019; Turner, 2015).

Education

The level of education is also an important factor distinguishing an individual’s attitude towards scientists. Studies have shown that people with lower levels of education and less exposure to science are more inclined towards attitudes of scientific populism (Mede et al., 2022; Spruyt et al., 2016; Kaltwasser & van Hauwaert, 2020; Lunz Trujillo, 2022). According to the theory of reflexive modernization, people with more education are more aware of the failures of scientific institutions, especially scientific projects (Allum et al., 2008), and thus may hold critical attitudes towards scientific institutions and scientists. Some research in China partly supports this view, with a significant negative correlation between the level of education and trust in scientists (Ye et al., 2023; Jin & Chu, 2015). The theory of anomie suggests that lower levels of education are associated with skepticism towards scientific institutions, and people with less education are more likely to feel threatened by modernity and institutionalized systems (Achterberg et al., 2017), thus being more inclined towards scientific populism. Conversely, people with higher levels of education show more interest and trust in science and research (Wissenschaft im Dialog, 2024; Funk et al., 2020; Price & Peterson, 2023) and are more likely to lean towards scientific elitism. However, some studies also suggest that the impact of education may not be significant (Evans & Hargittai, 2020). In addition, the relationship between education and attitudes towards scientists may be influenced by the level of risk and uncertainty in the institutional environment (Wu, 2021), showing a nonlinear relationship, that is, individuals with a moderate level of education show the most pronounced scientific populism (Eberl et al., 2023; Mede et al., 2022).

Income

Similar to the role of educational level as a distinguishing factor, the influence of income level on an individual’s attitude towards scientists is also complex. Although some studies point out that individual or household income is not a strong predictor of attitudes towards scientists (Evans & Feng, 2013; Gauchat, 2015), other studies suggest that higher-income groups are more likely to support scientific elitism (Gauchat, 2012), and support for scientific populism may decrease with higher income levels (Spruyt et al., 2016). This may be because economically disadvantaged groups are more likely to feel out of control and relatively impoverished, thus being more inclined to support populism. In contrast, economically affluent individuals, with more resources and a sense of security, are more inclined to support scientific elitism.

Media

The influence of media on individual support and trust in scientists is a complex issue (Hmielowski et al., 2014; Neureiter et al., 2021). Different media usage may lead to different levels of trust in science. People who frequently use traditional media, such as newspapers, television, and radio, may be more inclined towards scientific elitism (Anderson et al., 2012; Jin & Chu, 2015). However, in some regions, the use of traditional media is also positively predictive of scientific populism (Mede, 2022). Social media platforms add greater uncertainty to this influence (Van Dijck & Alinejad, 2020; Mihelj et al., 2022). Social media facilitate direct interaction among the public, allowing individuals to easily share and amplify their views. This direct participation is particularly conducive to the spread of personal ideologies and provides conditions for the dissemination of scientific populism (Postill,2018; Gerbaudo, 2018; Engesser et al., 2017). While the broader media environment in China has been discussed above, its specific impact on attitudes toward scientists requires further investigation.

Scientific interest

Some studies indicate that people with less interest in science may be more inclined towards scientific populism because they are less interested in and willing to understand science, thus tending to reject it (Choung et al., 2020; Spruyt et al., 2016). However, scientific populism may also be consistent with a higher interest in science (Motta, 2018), and skepticism towards scientists and other elites does not necessarily mean a lack of interest in scientific knowledge and research results (Mede et al., 2022). In fact, people who are skeptical of science often participate in scientific discussions (Wintterlin et al., 2022). Existing research in China suggests that people interested in science are more likely to lean towards scientific elitism compared to those without interest (Ye et al., 2023).

Post-materialism

Since the reform and opening-up in 1978, China’s economy, social structure, and cultural concepts have undergone significant changes, and social values have become increasingly diverse (Gao et al., 2022). Post-materialism has become an important perspective in studying the transformation of Chinese public values (Chi et al., 2023; Guo, 2010; Li, 2017; Li, 2020). Post-materialist theory suggests that when society develops to a certain stage and basic material needs are fully met, active political participation and the independent expression of one’s own interests become an important part of public life (Inglehart, 1971, 1977). This shift in values also promotes the development of social and political participation, with an increasing number of groups challenging the elite, and mass politics becoming more frequent (Cho & Park, 2020; Flanagan & Lee, 2003).

In the field of science, the transformation of social values may affect individuals’ trust in scientists. In post-materialist societies where the direct benefits of science are becoming less significant, along with a growing awareness of the possible negative effects of technological development, people may rely less on and trust scientists less (Price & Peterson, 2016). Those who are still in the materialist stage may have just begun to experience the benefits brought by science, such as vaccination and the advancement of information technology, and therefore may have higher expectations for improving their quality of life through science (Price & Peterson, 2023). Research has found that in some highly developed countries, public interest and positive attitudes towards science have declined (Bauer et al., 1994). With China’s rapid economic growth and social structural changes, some people may gradually adopt post-materialist values, which may lead them to adopt a populist attitude towards science (Li, 2017; Liu, 2021). However, it is also possible that some people may continue to maintain materialist values, thereby supporting scientific elitism. It is currently unclear whether post-materialist values directly shape attitudes towards scientists, and this hypothesis needs to be verified by further research. Interest in science may be a key factor in the impact of post-materialist values on attitudes towards scientists, but this point still needs to be further explored.

Post-materialism & scientific interests

Furthermore, the influence of post-materialist values on attitudes toward scientists may not be direct but could depend on certain contextual factors. Among these, interest in science may act as an important moderator. Post-materialists often exhibit a higher need for self-expression and a propensity for critical thinking, but whether these traits translate into specific attitudes toward scientists likely depends on their level of engagement with science. Cultural values and scientific interest may jointly shape the formation of attitudes toward scientists (Kahan et al., 2012). This hypothesis requires further investigation.

Data and methods

Data

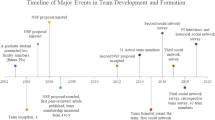

In December 2023, we conducted a large-scale online survey in mainland China using a quota-based non-probability sampling method. The sampling scheme was designed based on the demographic and geographic distribution data from the Chinese seventh national population census, ensuring representativeness in terms of geographical and age distribution (see Supplementary Material 1). The sampling error rate was 1.80%. Invitations were sent to 21,074 target respondents, and 9906 completed the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 47.01%.

To ensure data quality, rigorous screening was applied to the sample. During the automated filtering stage, 5,364 responses were excluded for reasons such as completion time being under 10 minutes, respondents being under 18 years old, exceeding geographic or age quotas, inconsistent answers to lie detection or duplicate screening questions, or detection of duplicate submissions based on IP address or device information. Subsequently, during the manual review stage, 1208 additional responses were excluded. These exclusions were based on anomalies such as selecting the same options for all scale items (variance = 0) and other inconsistencies in demographic variables (e.g., respondents aged 18-25 indicating a marital status of “widowed,” individuals with primary education indicating occupations as civil servants or teachers, respondents under 30 indicating “retired,” corporate executives reporting unusually low income, or PhD holders reporting manual labor jobs). After this rigorous screening process, 3000 valid responses were retained. Following the exclusion of records with missing data, a total of 2922 valid responses were included in the final analysis.

Measurement

Existing studies have developed scales such as SciPop (Mede et al., 2021) and NPSS (Morgan et al., 2018) to measure scientific populism or negative perceptions of science, providing significant insights into public attitudes toward scientists. However, rather than adopting predefined scales directly, this study employed an exploratory approach to extract key dimensions from the complexity of public attitudes toward scientists. This exploratory strategy revealed that scientific elitism and scientific populism are independent, asymmetrical dimensions rather than traditional binary opposites. We developed five items (see Supplementary Material 2): (1) Scientists know more about a scientific phenomenon than ordinary people. (2) Scientists’ views are more important than ordinary people’s opinions. (3) If all scientists agree on a theory, I will also believe in that theory. (4) Scientists rely too much on data and theory and ignore real-life experience. (5) Scientists’ research results are often wrong. We conducted a pilot survey using these five items in November 2023 (N = 100), and the measurement outcomes met our expectations. These items cover different aspects of public deference to and skepticism toward the professional authority of scientists. Respondents rated the items using a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 7 indicated “strongly agree.” A pilot study conducted in November 2023 (N = 100) confirmed that these items met expectations in terms of design.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to extract two distinct components from the first three and the last two items, named “scientific elitism” and “scientific populism,” respectively (see Supplementary Material 3). The results highlighted the multidimensional nature of attitudes toward scientists and validated the independence of scientific elitism and scientific populism. Internal consistency checks provided additional evidence. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scientific elitism items ((1), (2), and (3)) was 0.714, with an average interitem covariance of 0.905, indicating high consistency for this dimension. For the scientific populism items ((4) and (5)), the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.498, with an average interitem covariance of 0.891. While the lower internal consistency for scientific populism can be attributed to the smaller number of items, the scale remains theoretically robust. Notably, the lack of significant correlation between (1), (2), (3) and (4), (5) further underscores the independence of these two dimensions.

Based on the extracted components, we defined extreme variables: respondents scoring 6 or 7 on items (1), (2), and (3) were classified as “extreme scientific elitism”; respondents scoring 6 or 7 on items (4) and (5) were classified as “extreme scientific populism”; and respondents scoring 6 or 7 on all five items were classified as “scientific pluralism.”

For gender, education, and income variables, we adopted common practices. As for the generational division of Chinese people, there are different views in academia. However, most existing research believes that generational divisions should be based on key political events in Chinese history, such as the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Cultural Revolution, and the period of reform and opening up (Egri & Ralston, 2004; Sun & Wang, 2010). Therefore, we refer to existing research (Chi et al., 2023) and divide the samples into four different generations: (1) Initial construction generation, including those born before 1978; (2) Reform and opening up generation, born between 1979 and 1992; (3) Market-oriented generation, born between 1993 and 1999; (4) New century generation, born after 2000.

To measure post-materialist values, we adopted a scale fully aligned with the World Values Survey (Inglehart, 1981; Brym, 2016). To assess scientific interest, we used an indirect question: “How often do you discuss the latest developments or hot topics in science and technology with family, friends, and colleagues?” Although indirect measurement may result in some loss of validity, frequent interpersonal discussions about science-related topics can serve as an observable indicator of scientific interest (Romine et al., 2014). To measure social media usage, we asked: “How often do you visit information and comments related to science and technology on short video platforms such as TikTok, Kuaishou, or WeChat?”

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the core variables. All variables were standardized using Z-scores before analysis to mitigate the influence of different variable scales, improving the stability and comparability of the analysis. In the sample, males and females each accounted for 50.00%. Regarding income levels, 12.80% were in the low-income group (<6000 RMB), 21.20% in the low-middle income group (6000–9000 RMB), 27.00% in the middle-income group (9000–12000 RMB), 19.10% in the middle-upper income group (12000–15000 RMB), and 19.80% in the high-income group (>15000 RMB). In terms of education levels, 4.10% had elementary education, 12.80% had secondary education, 78.30% had tertiary or university education, and 4.80% had graduate education. Regarding generational segmentation, the initial construction generation (born before 1978) comprised 24.60%, the reform and opening-up generation (1979–1992) 13.30%, the market-oriented generation (1993–1999) 32.10%, and the new century generation (2000 and later) 30.00%.

Results

RQ1: Who is More Likely to Support Scientific Elitism or Scientific Populism?

Chi-square tests and ANOVA are useful for comparing group differences and providing descriptive statistics (see Supplementary Material 4). However, this study aims to uncover the key factors driving scientific elitism and scientific populism, making regression analysis a more suitable approach. Regression analysis not only accommodates both continuous variables (e.g., post-materialism, scientific interests, social media usage) and categorical variables (e.g., generation, education level, income level) but also allows for the control of confounding variables, enabling precise assessment of each variable’s independent effect on the outcomes. Additionally, regression analysis can model interaction effects, such as the interplay between post-materialism and scientific interests in shaping attitudes toward scientists, which helps to reveal complex relationships among variables. Therefore, regression analysis is crucial for this study. We also conducted a series of robustness checks to ensure the reliability of the regression results (see Supplementary Material 5).

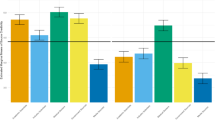

The regression results (see Table 2) reveal key findings: Women exhibit more conservative attitudes toward both scientific elitism and scientific populism. Compared to the low-income group, middle-income and middle-to-high-income groups display a significantly higher tendency toward scientific elitism. The high-income group shows the strongest inclination toward scientific elitism and a significantly lower tendency toward scientific populism. Furthermore, higher education levels correspond with a markedly lower tendency toward scientific populism compared to elementary education.

On the other hand, post-materialism is significantly associated with both scientific elitism and scientific populism, with a stronger correlation observed for scientific populism. Greater scientific interest fosters a tendency toward scientific elitism, while social media usage is strongly positively correlated with scientific populism. Generational differences are also evident: Compared to the market-oriented generation, the new century generation demonstrates a notably lower tendency toward scientific elitism, while scientific populism is on the rise among the younger generation.

When the dependent variables are changed to extreme scientific elitism and extreme scientific populism, slightly different patterns emerge. Women still exhibit more conservative positions, with significantly lower tendencies toward both forms of attitudes. Higher-income groups continue to show a stronger inclination toward scientific elitism. However, a critical difference arises: Middle-income and middle-to-high-income groups exhibit significant tendencies toward extreme scientific populism.

Education levels also yield distinctive patterns. Compared to elementary education, secondary, tertiary, and graduate education levels show significantly higher tendencies toward extreme scientific elitism. Interestingly, secondary education is significantly more associated with extreme scientific populism.

Generational differences reveal further nuances. Compared to the market-oriented generation, the new century generation exhibits a markedly lower tendency toward extreme scientific elitism but a higher tendency toward extreme scientific populism. Additionally, the initial construction generation shows a pronounced inclination toward extreme scientific populism. This suggests that the historical imprint of the Cultural Revolution or earlier periods may have shaped their populist attitudes.

Post-materialism is significantly associated with extreme scientific populism, while scientific interest is positively linked to both extreme scientific elitism and extreme scientific populism. Social media usage is significantly associated with extreme scientific populism but has no notable distinguishing effect on extreme scientific elitism.

RQ2: Who is more likely to simultaneously support scientific elitism and scientific populism?

We further explored whether extreme scientific elitism and extreme scientific populism could coexist within the same individual, referred to as scientific pluralism. The results indicate that women tended to adopt more conservative positions, while men were more likely to exhibit pluralistic tendencies. In terms of economic income, the middle-income group was more inclined towards pluralism compared to the low-income group. Regarding education, individuals with secondary and university education were more likely to demonstrate pluralistic tendencies than those with only elementary education. Generational differences were also significant: the initial construction generation was notably more inclined towards pluralism compared to the market-oriented generation. Both post-materialism values and scientific interest showed significant positive correlations with pluralism, whereas social media usage did not exhibit any significant association with this phenomenon.

The combined effect of post-materialism and scientific interest

As discussed in the literature review, post-materialism, as a broader social value system, may not directly shape attitudes toward scientists but interacts with scientific interest to exert influence. To test this theoretical hypothesis, we included an interaction term between post-materialism and scientific interest in the regression model to explore their combined effects on scientific elitism and scientific populism (see Table 3). The results show that the interaction term is significantly associated with both scientific elitism and scientific populism, while the standalone effect of post-materialist values becomes insignificant. This suggests that individuals with a strong interest in science are more likely to develop distinct attitudes toward scientists, whether in support of or in skepticism toward scientific authority. Conversely, those with little interest in science are less likely to exhibit strong attitudinal tendencies.

Discussion

The coexistence of “high deference” and “gradual populism” in Chinese attitudes toward scientists has sparked curiosity about the intricate dynamics within the Chinese context. We explored the subtle coexistence of scientific elitism and populism, along with their respective supporters, revealing a more multifaceted landscape than the single-dimensional perspectives commonly found in existing literature, particularly in studies focused on Western societies.

The conservative scientific tendencies of women

Contrary to the expectations of some existing literature, our study found that Chinese women did not show a more pronounced tendency towards scientific elitism (Yokoyama & Ikkatai, 2022) nor were they more inclined towards scientific populism (Morgan et al., 2018; Evans & Hargittai, 2020). In fact, Chinese women generally exhibited a conservative attitude towards scientists. This non-extreme attitude may stem from the caution of Chinese women and may also reflect broader social structural factors.

The middle-class pluralism

Our findings extend traditional assumptions about the relationship between social class and attitudes toward scientists, uncovering a more nuanced pattern. Contrary to research in Western societies that associates middle education levels with a greater propensity for scientific populism (Eberl et al., 2023; Mede et al., 2022), we find that in China, individuals with middle income and education levels display significant duality in their attitudes toward scientists. These individuals are not only likely to simultaneously hold scientific elitist and populist perspectives but may also lean toward pluralism. This coexistence of attitudes likely stems from the sense of “relative deprivation” experienced by the middle class—they are caught between lacking the economic advantages of the high-income group and the social supports and benefits available to the low-income group. This socio-economic “in-between” position creates favorable conditions for the emergence of complex attitudes toward scientists (Chen et al., 2023; Si et al., 2022).

Generational shifts in attitudes towards scientists

Unlike existing research discussing the impact of age on attitudes towards scientists, we are interested in the generational differences in attitudes towards scientists in Chinese society (Mede et al., 2022; Funk et al., 2020; Evans & Hargittai, 2020). The Initial construction generation experienced social upheavals such as the Cultural Revolution, and the social experiences of that era may have fostered skepticism towards any form of authority, leading to aversion to scientific elitism, and the populist attitudes towards scientists may also be rooted in the historical impact of that period (Zhang, 2016; Li & Guo, 2015). Meanwhile, the New century generation has grown up in an environment of information technology and the internet, where they are exposed to more information than any previous generation. This may lead them to be more cautious when facing scientific authority and knowledge. The scientific literacy education and critical thinking training of this generation may also reduce their unconditional worship of scientific elites, showing a lower tendency towards elitism and a higher tendency towards populism (Lazányi, 2019).

Scientific interest and post-materialism as “tracks of transformation”

Our research reveals the role of post-materialist values in shaping individual attitudes towards scientific populism, but the influence of these values needs to be activated and directed through an individual’s interest in science. In addition, individuals with a strong interest in science may exhibit dual tendencies towards both scientific elitism and scientific populism, indicating that scientific interest itself is multifaceted and can promote exploration and thinking from different perspectives about science, which complements existing literature (Ye et al., 2023; Choung et al., 2020; Motta, 2018).

Social media as an accelerator of polarization

Social media, particularly short video platforms, plays a pivotal role in driving the public toward scientific populism and its radical forms. These platforms amplify the “voice of the people” (Gerbaudo, 2018) and enable the rise of citizen science communicators—individuals without professional backgrounds who challenge traditional scientific authority (Yang, 2021). This dissolution of boundaries diversifies public perceptions of scientific authority (Yang, 2022) while intensifying polarization, making social media a critical force in shaping science communication.

Limitations

This study has certain limitations in terms of conceptual definition and research methods. Regarding conceptual measurement, although we developed a scale and conducted preliminary validation through a pilot survey, its face validity require further examination and confirmation. For instance, some items measuring scientific elitism and scientific populism did not explicitly specify whether the scientists’ opinions were confined to scientific domains, which may have led respondents to consider other fields when answering, potentially affecting measurement validity. In measuring scientific interest, we used indirect behavioral indicators to capture interest, which may not fully reflect respondents’ intrinsic levels of interest. Future research could consider combining direct and indirect measurement approaches.

Additionally, although we attempted to sample based on the geographic and age distribution of the national population, the sample may still be over-represented by individuals with higher education levels. Moreover, as this study employs a cross-sectional research design, it is not possible to establish causal relationships among the observed variables. Future studies should expand to other East Asian countries, such as Japan and South Korea, to enable cross-cultural comparisons and focus on improving measurement tools and methods to enhance both internal consistency and external validity.

Conclusion

Our study provides a supplementary perspective to the mainstream literature on the rise of scientific populism in Western societies, emphasizing that scientific elitism has not merely declined but can coexist with populism, reflecting a polarization at both societal and individual levels. This coexistence of attitudes should not be seen as a simple opposition but as a complex process involving multiple dimensions, including acceptance of basic knowledge, value identification, and emotional investment. This indicates a deep pluralism where individuals may cognitively accept scientific knowledge while being skeptical of scientists on emotional or value levels, akin to the coexistence of populism and elitism in the political field (Bertsou & Caramani, 2022; Akkerman et al., 2014). Moreover, individuals’ attitudes towards scientists may vary depending on specific contexts and topics, sometimes leaning towards elitism and at other times towards populism. In China, this pluralism is particularly pronounced, reflecting the tension between Confucian respect for authority and the trends of modern social innovation and critical questioning. Hence, in science communication research, we should recognize the diversity and complexity of attitudes towards scientists, avoiding the simplification of them as one-dimensional variables. Instead, we should understand their multifaceted and interpenetrating nature.

Our study also further distinguishes between conventional and extreme attitudes towards scientists. Simplifying conventional scientific elitism and populism as manifestations of polarization may overlook the inherent diversity and complexity of scientists’ attitudes. Extreme scientific populism may stem from deep social dissatisfaction or fundamental questioning, while conventional scientific populism may be more associated with direct responses to specific scientific issues or policies. In a society that emphasizes the value of professional knowledge, conventional scientific elitism can be understood as respect for the spirit of science. Similarly, in a society that advocates democratic participation and diverse voices, conventional scientific populism reflects a reasonable questioning and active participation in the scientific decision-making process, representing a constructive critical attitude, regardless of whether in the West or the East.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Achterberg P, De Koster W, Van der Waal J (2017) A science confidence gap: Education, trust in scientific methods, and trust in scientific institutions in the United States, 2014. Public Underst Sci 26(6):704–720

Akkerman A, Mudde C, Zaslove A (2014) How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comp Political Stud 47(9):1324–1353

Allum N, Sturgis P, Tabourazi D, Brunton-Smith I (2008) Science knowledge and attitudes across cultures: A meta-analysis. Public Underst Sci 17(1):35–54

Anderson AA, Scheufele DA, Brossard D, Corley EA (2012) The role of media and deference to scientific authority in cultivating trust in sources of information about emerging technologies. Int J Public Opin Res 24(2):225–237

Bauer M, Durant J, Evans G (1994) European public perceptions of science. Int J Public Opin Res 6(2):163–186

Bertsou E, Caramani D (2022) People haven’t had enough of experts: Technocratic attitudes among citizens in nine European democracies. Am J Political Sci 66(1):5–23

Brosius A, Ohme J, de Vreese CH (2022) Generational gaps in media trust and its antecedents in Europe. Int J Press/Politics 27(3):648–667

Brym R (2016) After Postmaterialism: An Essay on China, Russia and the United States. Can J Sociol 41(2):195–212

Butler, E. (2020, June 24). Coronavirus: Europeans say EU was irrelevant during pandemic. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/23/europeans-believe-in-more-cohesion-despite-eus-covid-19-failings

Chen H, Zhu Z, Yu B, Jin J (2023) Government trust, scientist trust, and social anxiety in public health crises: Observations from COVID-19 pandemic online public opinion. Contemp Commun 03:44–52

Chen X, Liu Y, Zhong H (2023) Generalized trust among rural-to-urban migrants in China: Role of relative deprivation and neighborhood context. Int J Intercultural Relat 94:101784

Chen Z, Zhu T (2023) Exploring the complex causes of “experts advising not to advise”: A perspective of distrust. N. Horiz Tianfu 05:97–106

Cheng T, Shi M (2020) A study of measurement of populism of the masses in China. Theory Reform 01:139–155

Chi S, Shi Y, Huang J (2023) Post-materialistic values and political participation of Chinese residents: Based on the analysis of generational differences. Chin J Sociol 43(05):204–234

Chinese Academy of Sciences. Code of conduct for academicians of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Trial) (2023)

Chin-Fu H (2013) Citizen journalism and cyberactivism in China’s anti-PX plant in Xiamen, 2007–2009. China: Int J 11(1):40–54

Cho K, Park, HY (2020) The evolution of south korean civic activism. In Research on KoreaSouth Korea’s Democracy Challenge (pp. 185-214). Peter Lang AG

Choung H, Newman TP, Stenhouse N (2020) The role of epistemic beliefs in predicting citizen interest and engagement with science and technology. Int J Sci Educ, Part B 10(3):248–265

Cologna V, Mede NG, Berger S et al. (2024) Trust in scientists and their role in society across 67 countries. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/6ay7s

Communist Party of China. Opinions on further promoting the spirit of scientists and strengthening the construction of work style and academic style. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-06/11/content_5399239.htm (2019)

Connaughton, A. Social trust in advanced economies is lower among young people and those with less education. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1426254/social-trust-in-advanced-economies-is-lower-among-young-people-and-those-with-less-education/2040657/ (2020)

Eberl JM, Huber RA, Greussing E (2021) From populism to the “plandemic”: Why populists believe in COVID-19 conspiracies. J Élect, Public Opin Parties 31(sup1):272–284

Eberl JM, Huber RA, Mede NG, Greussing E (2023) Populist attitudes towards politics and science: how do they differ? Political Res Exch 5(1):2159847

Edelman. Edelman Trust Barometer: Global report. Retrieved from https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2024-02/2024%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Global%20Report_FINAL.pdf (2024)

Egri CP, Ralston DA (2004) Generation cohorts and personal values: A comparison of China and the United States. Organ Sci 15(2):210–220

Elchardus M, Spruyt B (2014) Populism, persistent republicanism, and declinism: An empirical analysis of populism as a thin ideology. Gov Oppos 51(1):111–133

Engesser S, Ernst N, Esser F, Büchel F (2017) Populism and social media: How politicians spread a fragmented ideology. Inf, Commun Soc 20(8):1109–1126

Evans JH, Feng J (2013) Conservative Protestantism and skepticism of scientists studying climate change. Climatic Change 121:595–608

Evans JH, Hargittai E (2020) Who doesn’t trust Fauci? The public’s belief in the expertise and shared values of scientists in the COVID-19 pandemic. Socius 6:2378023120947337

Fan H (2015) The “problem trajectory” of ethics and morality in China and its spiritual form. J Southeast Univ (Philos Soc Sci) 17(01):5–19

Flanagan SC, Lee AR (2003) The new politics, culture wars, and the authoritarian-libertarian value change in advanced industrial democracies. Comp political Stud 36(3):235–270

Fominaya CF (2022) Mobilizing during the Covid-19 pandemic: From democratic innovation to the political weaponization of disinformation. American Behavioral Scientist, 00027642221132178

Funk C, Tyson A, Kennedy B, Johnson C (2020) Science and scientists held in high esteem across global publics. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2020/09/29/science-and-scientists-held-in-high-esteem-across-global-publics/

Gao H, Wang P, Tan K (2022) Chinese social value change and its relevant factors: An age-period-cohort effect analysis. Sociolog Stud 37(01):156–178+229

Gauchat G (2011) The cultural authority of science: Public trust and acceptance of organized science. Public Underst Sci 20(6):751–770

Gauchat G (2012) Politicization of science in the public sphere: A study of public trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. Am sociolog Rev 77(2):167–187

Gauchat G (2015) The political context of science in the United States: Public acceptance of evidence-based policy and science funding. Soc Forces 94(2):723–746

Gerbaudo P (2018) Social media and populism: an elective affinity? Media, Cult Soc 40(5):745–753

Gramlich J (2019) Young Americans are less trusting of other people–and key institutions–than their elders. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/616667/young-americans-are-less-trusting-of-other-people/1597340/

Greely HT (2019) CRISPR’d babies: human germline genome editing in the ‘He Jiankui affair’. J Law Biosci 6(1):111–183

Guenther L, Weingart P, Meyer C (2018) Science is everywhere, but no one knows it”: assessing the cultural distance to science of rural South African publics. Environ Commun 12(8):1046–1061

Guo L (2010) Changes in Chinese public values in recent years: From “materialist values” to “post-materialist values. Trib Study 26(10):61–64

Hassid J (2020) Censorship, the Media, and the Market in China. J Chin Political Sci 25(2):285–309

He G, Wang F (2009) Public image of S&T professionals and its cognitive basis in China. China Soft Science, 83-93

Hmielowski JD, Feldman L, Myers TA, Leiserowitz A, Maibach E (2014) An attack on science? Media use, trust in scientists, and perceptions of global warming. Public Underst Sci 23(7):866–883

Hofstede G (1984) Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. sage

Hu L, Liu R, Zhang W, Zhang T (2020) The effects of epistemic trust and social trust on public acceptance of genetically modified food: An empirical study from China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(20):7700

Huang G (2015) PM2. 5 opened a door to public participation addressing environmental challenges in China. Environ Pollut 197:313–315

Inglehart R (1971) The silent revolution in Europe: Intergenerational change in post-industrial societies. Am political Sci Rev 65(4):991–1017

Inglehart R (1977) Values, objective needs, and subjective satisfaction among western publics. Comp Political Stud 9(4):429–458

Inglehart R (1981) Post-materialism in an environment of insecurity. Am political Sci Rev 75(4):880–900

Jia H, Shi L, Wang D (2018) Passive communicators: Chinese scientists’ interaction with the media. Sci Bull 63(7):402–404

Jia H, Wang D, Miao W, Zhu H (2017) Encountered but not engaged: Examining the use of social media for science communication by Chinese scientists. Sci Commun 39(5):646–672

Jin J, Chu Y (2015) Scientific literacy, media use and social networks: Understanding public trust towards scientists. Glob Media J 2(02):65–80

Johnson DR, Scheitle, CP, Ecklund EH (2015) Individual Religiosity and Orientation towards Science: Reformulating Relationships. Sociological Science, 2

Kahan DM, Peters E, Wittlin M, Slovic P, Ouellette LL, Braman D, Mandel G (2012) The polarizing impact of science literacy and numeracy on perceived climate change risks. Nat Clim Change 2(10):732–735

Kaltwasser CR, Van Hauwaert SM (2020) The populist citizen: Empirical evidence from Europe and Latin America. Eur Political Sci Rev 12(1):1–18

Kennedy B, Tyson A, Funk C (2022) Americans value U.S. role as scientific leader, but 38% say country is losing ground globally. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/10/25/americans-value-u-s-role-as-scientific-leader-but-38-say-country-is-losing-ground-globally/

Kim SJ, Lee MJ, Choi S (2017) A study on the authority and trust of experts in Korean society. Ewha J Soc Sci 33(2):177–215

Lasco G (2020) Medical populism and the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob Public Health 15(10):1417–1429

Lazányi K, (2019, April). Generation Z and Y–are they different, when it comes to trust in robots?. In 2019 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Engineering Systems (INES) (pp. 000191-000194). IEEE

Lee K, Ho MS (2014) The Maoming Anti-PX protest of 2014. An environmental movement in contemporary China. China Perspectives, 2014 (2014/3), 33-39

Li T, Fung H (2013) Age differences in trust: An investigation across 38 countries. J Gerontol Ser B: Psycholog Sci Soc Sci 68(3):347–355

Li W, Yang G, Li X (2021) Correlation between PM2. 5 pollution and its public concern in China: Evidence from Baidu Index. J Clean Prod 293:126091

Li X, Guo L (2015) Changes of language in describing Chinese scientists’ image in modern times—Based on word frequency analysis of long report of scientists’ image in People’s Daily within the last 66 years. Stud Philos Sci Technol 32(03):84–90

Li Y (2017) Post-materialism value and public political trust in contemporary China—A comparative analysis from intergeneration perspective. J Public Manag 14(03):60–72+156

Li Y, (2020) A realistic observation and theoretical interest in “Post-Materialist Values”. People’s Tribune, (04):132-135

Li Y, Liu D, Shao L (2024) Propaganda with Subculture: A Resource for Internet Control in China. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 1-25

Liu W, Xiao S, Peng Q (2021) Political trust, perception of government performance and political participation –Based on the data of the “Chinese People’s Political Mentality Survey” (2019). J Cent China Norm Univ(Humanities Soc Sci) 60:1–9

Lunz Trujillo K (2022) Rural identity as a contributing factor to anti-intellectualism in the US. Political Behav 44(3):1509–1532

Luo X, Jia H (2022) When scientific literacy meets nationalism: Exploring the underlying factors in the Chinese public’s belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Chin J Commun 15(2):227–249

Lü L, Chen H (2016) Chinese public’s risk perceptions of genetically modified food: From the 1990s to 2015. Science. Technol Soc 21(1):110–128

Lü S, Gao G (2024) “Advise the experts not to advise”: Research on “message fatigue” during public health emergencies. China. Public Adm Rev 6(01):5–25

Ma D, Yang F (2014) Authoritarian orientations and political trust in East Asian societies. East Asia 31:323–341

Mahl D, Schäfer MS, Zeng J (2023) Conspiracy theories in online environments: An interdisciplinary literature review and agenda for future research. N. Media Soc 25(7):1781–1801

Mede NG (2022) Legacy media as inhibitors and drivers of public reservations against science: Global survey evidence on the link between media use and anti-science attitudes. Humanities Soc Sci Commun 9(1):1–11

Mede NG, Schäfer MS (2020) Science-related populism: Conceptualizing populist demands toward science. Public Underst Sci 29(5):473–491

Mede NG, Schäfer MS, Füchslin T (2021) The SciPop Scale for measuring science-related populist attitudes in surveys: Development, test, and validation. Int J Public Opin Res 33(2):273–293

Mede NG, Schäfer MS, Metag J, Klinger K (2022) Who supports science-related populism? A nationally representative survey on the prevalence and explanatory factors of populist attitudes toward science in Switzerland. Plos one 17(8):e0271204

Mietzner M (2020) Rival populisms and the democratic crisis in Indonesia: Chauvinists, Islamists and technocrats. Aust J Int Aff 74(4):420–438

Mihelj S, Kondor K, Štětka V (2022) Establishing trust in experts during a crisis: Expert trustworthiness and media use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Commun 44(3):292–319

Morgan M, Collins WB, Sparks GG, Welch JR (2018) Identifying relevant anti-science perceptions to improve science-based communication: The negative perceptions of science scale. Soc Sci 7(4):64

Motta M (2018) The dynamics and political implications of anti-intellectualism in the United States. Am Politics Res 46:465–498

Mudde C (2004) The populist zeitgeist. Gov Oppos 39(4):541–563

Neureiter A, Stubenvoll M, Matthes J (2021) Trust in science, perceived media exaggeration about COVID-19, and social distancing behavior. Front Public Health 9:670485

Postill J (2018) Populism and social media: a global perspective. Media, Cult Soc 40(5):754–765

Poulin MJ, Haase CM (2015) Growing to trust: Evidence that trust increases and sustains well-being across the life span. Soc Psycholog Personal Sci 6(6):614–621

Price AM, Peterson L (2023) The health and environmental risks and rewards of modernity that shape scientific optimism. Public Underst Sci 32(6):781–797

Price AM, Peterson LP (2016) Scientific progress, risk, and development: Explaining attitudes toward science cross-nationally. Int Sociol 31(1):57–80

Qiu H, Huang J, Pray C, Rozelle S (2012) Consumers’ trust in government and their attitudes towards genetically modified food: empirical evidence from China. J Chin Econ Bus Stud 10(1):67–87

Ralph-Morrow E (2022) The right men: How masculinity explains the radical right gender gap. Political Stud 70(1):26–44

Rauchfleisch A, Tseng TH, Kao JJ, Liu YT (2023) Taiwan’s public discourse about disinformation: The role of journalism, academia, and politics. Journalism Pract 17(10):2197–2217

Rekker R (2021) The nature and origins of political polarization over science. Public Underst Sci 30(4):352–368

Romine W, Sadler TD, Presley M, Klosterman ML (2014) Student interest in technology and science (SITS) survey: Development, validation, and use of a new instrument. Int J Sci Math Educ 12:261–283

Scheufele DA, Hoffman AJ, Neeley L, Reid CM (2021) Misinformation about science in the public sphere. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(15):e2104068118

Schwartz SH (1992) Universals in the content and structure of values: theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 25:1–65

Si W, Jiang C, Meng L (2022) Leaving the homestead: examining the role of relative deprivation, social trust, and urban integration among rural farmers in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(19):12658

Sismondo S (2017) Post-truth? Soc Stud Sci 47(1):3–6

Spruyt B, Keppens G, Van Droogenbroeck F (2016) Who supports populism and what attracts people to it? Political Res Q 69(2):335–346

Spruyt B, Rooduijn M, Zaslove A (2023) Ideologically consistent, but for whom? An empirical assessment of the populism-elitism-pluralism set of attitudes and the moderating role of political sophistication. Politics 43(4):536–552

Staerklé C, Cavallaro M, Cortijos‐Bernabeu A, Bonny S (2022) Common sense as a political weapon: Populism, science skepticism, and global crisis‐solving motivations. Political Psychol 43(5):913–929

Stenmark M (1997) What is scientism? Religious Stud 33(1):15–32

Sun J, Wang X (2010) Value differences between generations in China: A study in Shanghai. J Youth Stud 13(1):65–81

Tan HH, Chee D (2005) Understanding interpersonal trust in a Confucian-influenced society: An exploratory study. Int J Cross Cultural Manag 5(2):197–212

Turner A (2015) Generation Z: Technology and social interest. J Individ Psychol 71(2):103–113

UZH News. (2022) 2022 Science Barometer Switzerland: Majority of Swiss trust science, some remain skeptical. https://www.news.uzh.ch/en/articles/media/2022/Science-Barometer.html

Van Dijck J, Alinejad D (2020) Social media and trust in scientific expertise: Debating the Covid-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. Soc Media+ Soc 6(4):2056305120981057

Wang C, Lu C, Zhan Y (2022) Research on the public trust in scientists on the media under social controversy: Take the “PX” series events in China as an example. Stud Dialectics Nat 38(06):71–75

Wang K, Xu S (2021) Research on the image of scientists in science communication: Based on the semantic network analysis of Chinese modern scientist biography. J Dialectics Nat 43(05):94–101

Wintterlin F, Hendriks F, Mede NG, Bromme R, Metag J, Schäfer MS (2022) Predicting public trust in science: The role of basic orientations toward science, perceived trustworthiness of scientists, and experiences with science. Front Commun 6:822757

Wissenschaft im Dialog. (2024). Science barometer 2023. https://www.wissenschaft-im-dialog.de/en/our-projects/science-barometer/science-barometer-2023/

Wu C (2021) Education and social trust in global perspective. Sociological Perspect 64(6):1166–1186

Xiang Q, Chu Y, Jin J (2015) Scientists in the public trust landscape: An empirical study. Mod Commun(J Commun Univ China) 37(06):46–50

Yang Z (2021) Deconstruction of the discourse authority of scientists in Chinese online science communication: Investigation of citizen science communicators on Chinese knowledge sharing networks. Public Underst Sci 30(8):993–1007

Yang Z (2022) The new stage of public engagement with science in the digital media environment: citizen science communicators in the discussion of GMOs on Zhihu. N. Genet Soc 41(2):116–135

Ye J, He G, Zhang W (2023) Research on the changes of Chinese people’s evaluation on scientists’ image (2007—2021). Forum on Science and Technology in China, (11), 120-128

Ylä-Anttila T (2018) Populist knowledge:‘Post-truth’repertoires of contesting epistemic authorities. Eur J Cultural Political Sociol 5(4):356–388

Yokoyama HM, Ikkatai Y (2022) Support and trust in the government and COVID-19 experts during the pandemic. Front Commun 7:940585

Yuan H, Long Q, Huang G, Huang L, Luo S (2022) Different roles of interpersonal trust and institutional trust in COVID-19 pandemic control. Soc Sci Med 293:114677

Yuan S, Rui J, Peng X (2023) Trust in scientists on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and vaccine intention in China and the US. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 86:103539

Zhai Y (2017) Values of deference to authority in Japan and China. Int J Comp Sociol 58(2):120–139

Zhai Y (2022) Values change and support for democracy in East Asia. Soc Indic Res 160(1):179–198

Zhang F (2016) Research on the images of scientists in the People’s Daily. Stud Dialectics Nat 32(11):66–70

Zhao Y, Ye J, He G (2021). Public trust in scientists during risk event and its influencing factors. China Soft Science, 40-51

Zhong H (2020) Shaping the image of scientists in the battle against the pandemic. Youth Journalist, (21), 61-62

Zhu Z (2017) Backfired government action and the spillover effect of contention: A case study of the anti-PX protests in Maoming, China. J Contemp China 26(106):521–535

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Major Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 21ZDA017). This work was also supported by World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), MEXT, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SW and TW; methodology: SW and TW; formal analysis: SW and TW; resources: ZL; writing—original draft preparation: SW; writing—review and editing: HMY and SK; supervision: HMY and ZL; funding acquisition: ZL. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire survey used in this study has been approved by the Tsinghua University Science and Technology Ethics Committee (Humanities, Social Sciences and Engineering) with approval number THU-12-2023-06. The approval date is December 10, 2023. All surveys were conducted in accordance with the relevant laws and regulations of the People’s Republic of China.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants through the online survey. At the beginning of the survey, participants were informed that they had the right to choose whether to participate, could stop at any time, and that their responses would be anonymized to protect their identities. They were also assured that their personal information would be strictly confidential in accordance with the Statistics Law of the People’s Republic of China and that the survey would not involve any sensitive information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, S., Wang, T., Yokoyama, H.M. et al. Beyond a single pole: exploring the nuanced coexistence of scientific elitism and populism in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 353 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04685-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04685-3