Abstract

This study aims to dynamically analyze changes in labor income in Argentina before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to characterize the economic trajectories of workers and assess their relationship with occupational inequality during such period. By employing panel data from a national urban survey, we implemented a novel methodological strategy that combines latent growth curve (LGC) models to define income trajectories and multinomial logistic regression analysis so as to evaluate the determinants of these trajectories. After extensive analysis, the results confirm the existence of divergent trajectories. On the one hand, downward trajectories primarily affect socially disadvantaged workers in the informal sector. On the other hand, stable or upward trajectories are observed mainly among individuals employed in formal economic units, particularly those with medium or high levels of education. These findings support the literature that highlights the regressive impact of labor market segmentation and social inequalities on income and employment opportunities for certain groups of workers in economies characterized by structural heterogeneities at both the productive and occupational levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, within the framework of significant transformations in production systems, work organization, and labor relations (Acemoglu and Autor 2011), interest has grown in examining the relationship between labor mobility, market segmentation, and their effects on income levels (Autor 2010; Del Rio-Chanona et al. 2021; International Labor Organization ILO 2024).

A labor market is considered segmented when a worker with the same productivity receives a different wage across occupations, or when two workers with identical human capital exhibit different present values of their future earnings. While it is natural for wage differences to arise from variations in productivity, segmentation implies that these disparities are not explained by productivity differences but rather by economic, institutional, social, or cultural factors.Footnote 1

Given the context of rapid technological advancements (Manyika et al. 2017), the proliferation of more flexible and precarious labor relations (Prieto 2002) and the increasing productive heterogeneity across sectors and firms on a global scale (Andersson and Palacio Chaverra 2016; Buera et al. 2015; Chong and Gradstein 2007; Abramo 2021), occupational transitions are being reconfigured, elevating the risks of labor exclusion. According to some specialists, the frequent occurrences of employment discontinuity and unemployment even challenge the very notion of a “labor trajectory” (Heinz and Krüger 2001).

Under these circumstances, the profound economic and labor crisis triggered by COVID-19, followed by a rapid economic recovery, accelerated substantial changes in the composition, organization, and functioning of labor markets worldwide (International Labor Organization ILO 2023, 2024). However, there are compelling reasons and significant evidence to suggest that these processes have followed distinct dynamics in developed economic systems compared to the segmented labor markets of underdeveloped economies, such as those in Latin America and the Caribbean (Weller 2020; Velasco 2021; Beccaria et al. 2022; Maurizio et al. 2023).Footnote 2 In Global North countries, labor demand increasingly favors highly skilled workers, resulting in wage stagnation for a significant segment of the workforce. Atypical forms of employment, labor market deregulation, and flexibility are on the rise, with substantial implications for living conditions and well-being (Clark et al. 2021). In the Global South, these global trends intersect with the pre-existing structural prevalence of large informal economic sectors, leading to segmented labor markets and, consequently, a predominance of highly precarious jobs (Weller 2022; Abramo 2021; Delaporte et al. 2021; International Labor Organization ILO 2024).

Latin America and the Caribbean was one of the most severely affected regions by the economic and health crisis triggered by the pandemic, leading to an abrupt contraction in employment levels, hours worked, and labor and household incomes, particularly during the first half of 2020 (Economic Commission for Latin America ECLAC/International Labor Organization ILO 2020). In this regard, several studies agree that the main regressive social effects during the pandemic were linked to the contraction of the informal sector (Weller 2020; Velazco 2021; Maurizio et al. 2023). Furthermore, it has been documented that the lockdowns imposed during the pandemic significantly increased unemployment and forced inactivity, affecting all economic sectors but with greater repercussions on informal employment due to the lack of access to unemployment insurance and other social protections. These impacts have exacerbated inequalities, and the path to recovery appears to be widening employment and income gaps among different population groups (Beccaria et al. 2022; Maurizio et al. 2023).

In this regard, Acevedo et al. (2023) analyzes the evolution of inequality in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic using household survey data collected in 2020 for 16 countries in the region. Employing a fixed-effects panel regression model, the results indicate an increase in inequality between 2019 and 2020 caused by the decline in employment. The results reveal significant heterogeneity when disaggregated by gender, urban/rural location, and economic activity sector. While remittances had a modest effect, government transfers played a key role in mitigating disparities.

The level of economic development, the prevalence of informality in labor markets, and the effectiveness of government policies are factors that tend to explain the observed heterogeneity across different economies. However, most of the variation in labor income losses observed among countries is attributable to the sectoral and occupational employment structure of their economies (Delaporte et al. 2021; International Labor Organization ILO 2023, 2024). In this regard, it is worth questioning whether labor market segmentation has been a key factor in explaining these divergences in the context of developing economies.Footnote 3 This study aims to identify income trajectories of workers in Argentina before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic and to evaluate their relationship with occupational inequality. Relying on a panel sample of workers from various occupational segments, the research examines, classifies, and describes the different income trajectories over the 2019–2023 period.

In general, studies on occupational mobility focus on panel designs that examine trajectories and thereafter assess their relationship with labor income. This study adopts a novel and different strategy. First, we employ latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM), an analytical technique that is relatively unexploited in this field, to define labor earnings trajectories. These trajectories are not defined a priori, but arise from the exploitation of a panel of observations. Then, we utilize multivariate logistic regression models to analyze the characteristics of the individuals who experienced such trajectories, considering their occupational, sectoral, and social characteristics.

This work discusses the Argentine case as significant for analyzing labor market dynamics, particularly amidst the COVID-19 crisis and recurring economic downturns marked by stagnation and inflation. It highlights the impact of crises on labor market organization, which can hinder unemployment and income opportunities for affected workers. The document underscores the importance of continuing research on this phenomenon, in contexts of economies with high informality and segmented labor markets to enhance the understanding of occupational mobility and to design more effective policies for such scenarios. In this regard, it is crucial to note that for most countries in the region, the creation of better-paying jobs remains the primary source of well-being (Azevedo 2013).

The study of wage segmentation processes associated with labor mobility dynamics during periods of crisis, reforms, or productive changes in economies with high informality rates has significant implications for public policy. The way these social dynamics are modeled is not merely an academic concern but carries critical implications for designing more effective poverty alleviation strategies in developing economies.

This paper is organized as follows. After this Introduction, the Literature Review analyzes the background on the relationship between labor mobility and income inequality. The Data and Methods section describes the source of information, and the methodology used. The Results section presents the statistic analysis that supports the study’s contributions, which are evaluated in the Discussion. Finally, the Conclusion summarizes the main findings of the paper.

Literature review

The contemporary literature continues to debate the impact of occupational mobility processes on labor earnings. Labor trajectories not only vary throughout the individual life cycle, but are also profoundly influenced by the economic, social, and institutional environment in which they develop (Heinz 2004). The concept of “occupational mobility” encompasses a series of changes and transitions in occupations that an individual may experience throughout their career. These changes can include upward and downward movements, as well as exits from the labor market.

Evidence shows that economic globalization, the decline of manufacturing jobs, the advances in information and communication technologies, and the waves of corporate restructuring have complex—and sometimes contradictory—effects on workers’ occupational stability and careers, although they have not generated a fall in the employment rate (Heinz 2004; Buera et al. 2015). For example, studies on the effects of digitalization and telework on labor markets report a decline in occupations with a high content of routine tasks, not always associated with wage improvements (Autor and Dorn 2013; Del Rio-Chanona et al. 2021).

However, the role of occupational transitions in employment quality and wages remains unclear. On the one hand, there is evidence suggesting that involuntary job changes lead to a loss of human capital invested in specific skills, negatively affecting career trajectories (Grand 2002; Nickell et al. 2002; Buchelli and Furtado 2002). On the other hand, some longitudinal studies indicate that in markets with high levels of labor informality, greater mobility between sectors can function as a pathway out of precarious work conditions and as a mechanism for wage equalization (Cunningham and Maloney 2000; Levy 2008). Conversely, other dynamic studies highlight that labor mobility driven by crises or reforms in highly precarious labor markets particularly undermines job stability and employment quality in informal sectors (Beccaria et al. 2022; Ruesga et al. 2014).

The different outcomes induced by occupational mobility could be explained by the control of the different modes of regulation and institutional quality of labor markets. Countries with a flexible labor market, such as the United Kingdom or the United States, seem to compensate for low labor or professional stability with considerable re-employment opportunities after episodes of short-term unemployment. Conversely, in highly regulated labor markets, a high level of occupational training and career continuity is maintained, but with a tendency to exclude low-skilled workers (Heinz 2004).

In this regard, in less developed economies with labor markets where regulatory power is also segmented, labor mobility processes tend to be more regressive and less elastic, as labor institutions operate in a partial or limited manner. Additionally, labor income inequalities are exacerbated by disparities in marginal productivity levels (Weller and Kaldewei 2014; Carbonero et al. 2020). In these markets, “formal” sectors—comprising private and public enterprises with medium to high productivity levels—coexist with widespread “informal” sectors, whose dynamics are largely driven by subsistence needs and the labor supply surpluses of low-income households (Mezzera 1987; Infante 2011; Salvia 2012).

A central feature influencing wage differentials in these markets, while simultaneously constraining labor mobility processes, is the productivity lag and sectoral heterogeneity in terms of technological assimilation (Weller and Kaldewei 2014). The inability of informal sectors to access new technologies due to financial barriers is reported as an additional mechanism that perpetuates a low-productivity informal sector (Amaral and Quinti 2006; Perry et al. 2007). These dynamics generate heterogeneous effects on labor demand, which impact labor transitions and income trajectories (Weller et al. 2019; Ciaschi et al. 2021). Similarly, other studies highlight a differential effect of mobility between formal and informal workers, exacerbated in contexts of low institutional quality in labor markets (Perry et al. 2007; Chong and Gradstein 2007).

In this context, the weak labor regulations that prevail primarily in the informal market can influence these outcomes. For example, greater contractual flexibility and the low coverage of unemployment insurance—almost non-existent in dual economies—tend to promote an increase in highly precarious jobs or a reduction in structural unemployment (ECLAC 2018; Tokman 1987). Accordingly, it can be assumed that labor mobility processes—even in the medium- or high -productivity segments—will not occur in the same way or direction, or at least not at the same speed, as in advanced economies.

On the other hand, although the unequal effects of organizational, technological, and productive changes on the earnings of salaried workers in developed economies are widely recognized (Acemoglu and Autor 2011; Autor 2010; Autor and Dorn 2013), studies addressing this issue dynamically in dual labor markets remain scarce. This gap became even more pronounced in the context of the economic and health crisis caused by COVID-19. Therefore, analyzing occupational mobility and its effects on labor income trajectories before, during, and after the pandemic in a segmented labor market such as Argentina’s represents an innovative contribution to the study of occupational mobility and its impact on economic inequality.

Indeed, the Argentine labor market is characterized by increasing segmentation, resulting from a combination of structural reforms, prolonged periods of low growth, and recurrent crises (Salvia et al. 2024; Vera 2015; Beccaria and Groisman 2016; Paz 2013). There is a strong regulation of salary relationships by means of protective norms that promote regular and permanent employment, together with active union mediation (Bertranou and Casanova 2015). This regime coexists with another fraction of the labor market that involves around 35% of the salaried labor force and operates around low-productivity value chains formed by small economic units with low profitability and irregular working conditions (i.e., outside formal regulations). In addition, there is a group of non-professional self-employed workers who are not registered in the social security system. Taking this into account, we can say that around 50% of those employed are part of an informal labor market (Donza 2023).

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous activities underwent processes of restructuring in terms of working conditions and labor relations (Bonacini et al. 2021; Clark et al. 2021; Maurizio et al. 2023). Similarly, as in the rest of the region, the greatest job losses in the Argentine labor market were concentrated in precarious labor relations, low-skilled jobs and low-wage employment (Donza et al. 2022; Beccaria et al. 2022; Maurizio et al. 2023; Fernández and Monsalvo 2023). However, due to the structural nature of the productive, social, and occupational segmentation of the Argentine economy—further influenced by the type of health policies implemented—informal employment did not serve as a refuge against job losses or reductions in the formal sector. On the contrary, informal employment experienced an even sharper contraction, leading to a decline in the informal employment rate across the region during the first half of 2020. However, in the subsequent phase, informal occupations accounted for the majority of job recovery from mid-2020 onward, causing the informal employment rate to return to—or even exceed—pre-pandemic levels in some countries (Beccaria et al. 2022; Maurizio et al. 2023; Velasco 2021).

The performance of the Argentine labor market during the pandemic was profoundly shaped by widespread business closures, mobility restrictions, and disruptions in supply chains. These conditions primarily impacted the informal sector and unregulated jobs, leading to a significant increase in labor inactivity among displaced workers (Donza et al. 2022; Beccaria et al. 2022). This trend reversed during the recovery phase of the health crisis, although such recovery was not uniform (Casarico and Lattanzio 2022; Cerqua and Letta 2022; Cortés and Forsythe 2023; Clark et al. 2021; Maurizio et al. 2023; Gil and Rougier 2023).

A distinctive aspect of the Argentine case is that the COVID-19 crisis was preceded by a period of high inflation and prolonged recession, which persisted into the post-pandemic period. In 2021, with most restrictions lifted, there was a rapid economic recovery, with GDP growing by over 10%. However, this recovery slowed in 2022, and in 2023, GDP contracted (−0.8%). Since 2021, employment rates have progressively recovered, and unemployment rates have declined. Nonetheless, inflation has exceeded 200% annually, and poverty has affected over 35% of the population (Donza 2023).

The present paper aims to contribute to labor mobility studies through a panel of earnings trajectories before, during, and after the pandemic for a sample of urban salaried and non-salaried workers with different educational and social attributes, inserted in both formal and informal units and subjected to different forms of labor regulation. In this regard, it is to be expected that earnings trajectories will take divergent and qualitatively different forms from those occurring in more developed and productively integrated economies, even if the level of protection or flexibility of the labor markets involved is controlled.

Data and methods

In general, panel studies on the labor market aim to identify individuals’ occupational mobility over time to eventually assess its impact on labor earnings trajectories. However, our study takes a different approach: first, we define the labor earnings trajectories of active workers between 2019 and 2022 using the latent growth curve (LGC) model; then, we explore the sociodemographic and occupational profiles associated with these trajectories, as well as a series of factors influencing these findings through descriptive statistics and logistic regression models.

This paper relies on five waves (2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023) of the Argentine Social Debt Survey (EDSA, for its acronym in Spanish) conducted before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. EDSA is a national multipurpose survey carried out between July and October on an annual basis by the Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina. This survey collects socioeconomic data on households and their members in urban areas with more than 80 thousand inhabitants, representing 60% of the total national population. The sample size includes 5700 households and respondents. EDSA uses a multistage probability sample design with non-proportional stratification and systematic household selection. The first stratification criterion is determined by the population size of the urban areas included in the sample. The second criterion is based on a socioeconomic index for each census radius, which is summarized in six strata. The third stage involves a systematic random sample of households within the census radius. The last phase consists of a random selection of the adults in the household to complete age and gender quotas corresponding to each residential radius.Footnote 4

The longitudinal design of the EDSA provides an annual follow-up panel for one-third of the households in the initial sample, which progressively reduces to half with each subsequent year of data collection. The selection of panel cases is based on a random rotation scheme, similar to those used in other household surveys. However, the survival of cases obtained through this procedure is not representative of the general sample. Since the EDSA panel design does not aim to represent the population, the longitudinal sample generated by this procedure is not subjected to recalibration or additional weighting.

Within the framework of this study, the panel case observations obtained from this survey generate a matrix of censored observations (Clark et al. 2003). Missing data for the censored observations are imputed with sequential multiple imputation methods, using as predictors the variables available both in the entire dataset and in previous datasets. This approach assumes that the missing data are missing at random (MAR) or missing completely at random (MCAR), meaning that the probability of their missingness depends only on observed values in the dataset.

The present paper analyzes the evolution of monthly labor income to evaluate the social composition of different economic trajectories and their associated factors. A person is considered employed if he/she has worked at least one hour during the week before the survey (this is the official definition of employment in Argentina, following ILO standards). The population of this study is defined as those individuals who are employed at t0 (i.e., 2019) and earn labor income, even if they leave the labor market after that time. The final sample size of the panel dataset consists of 2671 individuals. All the descriptions provided in the paper consider the variables at t0.Footnote 5

We fit the latent growth curve (LGC) model to estimate the intercepts and the random slopes describing the initial value and the rate of change of labor income. Since labor income is positively skewed, we use the square root of labor income to normalize the distribution. Following Vargas-Chanes and Valdés-Cruz (2019), the LGC model can be formally expressed as follows:

where

In (1), Yti is the square root of monthly labor income for the i-th individual at time t; λt is the effect of time, with error terms εti. Terms π0i and π1i are the intercept and the slope for each individual. Terms r0i and r1i are random errors of the corresponding intercepts and slopes for each income trajectory for each i-th individual.

In longitudinal data, a trajectory describes the evolution of some repeated measure of interest over time. The purpose of trajectory modeling is to classify individuals into distinct subgroups or classes based on personal response patterns (Nguena Nguefack et al. 2020). In this case, the classification is based on the current monthly income received by the individuals in the panel in each of the observations. Next, we use LGMM, which assumes a finite number of ‘latent classes’ with similar trajectories in the population. The method estimates an average growth curve for each group, considering variation between individuals of the same class. To capture this heterogeneity, the model introduces random effects to estimate the gap between the individuals’ growth and the estimated subpopulation curve. Parameters are estimated by maximizing the log-likelihood function, and the probability of belonging to each class is computed for each individual (Nguena Nguefack et al. 2020).

LGMM requires some criteria to define the number of classes. Following Vargas-Chanes and Valdés-Cruz (2019), we use five criteria: (1) the Bayes Information Criterion (BIC): the smaller the value, the better the model fit; (2) the entropy value: a value closer to the unit indicates a better fit; (3) all classes must have at least 5% of the total observations; (4) the probability of belonging to each group must be greater than or equal to 0.70; (5) the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test, which tests the null hypothesis that a higher number of classes is better than a lower number of classes. The classification variable was the monthly labor income at constant prices for the individuals in the panel at each of the points in time considered.

Once the latent classes are defined, we proceed to their description. This can be done with both descriptive statistics and multivariate techniques. In our case, in addition to a first descriptive approach, the probability of belonging to each class is modeled using multinomial logistic regressions. These regressions are appropriate because the dependent variable is polytomous.

Results

Results from the application of the latent class analysis model for labor earnings trajectories are first presented below. Classes of trajectories are identified by applying the LGMM model. The factors associated with belonging to each of the classes are analyzed in the second part of this section. This analysis allows characterizing the different groups.

The identification of economic trajectory classes

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for individuals’ labor income in 2019. This year represents the time before the outbreak of COVID-19, whereas the year 2020 represents the time of the greatest restrictions to mobility due to the pandemic. In contrast, the subsequent years represent a period of recovery in the level of activity, yet with an increasing rate of inflation. The highly inflationary economic context, beyond the initiatives of the government and union actors in terms of agreeing compensation policies, negatively affects the level of real remunerations (see Table 1), which is consistent with the information reported in the literature (Donza 2023).

To analyze the evolution of monthly labor income, we estimate an LGC model, as described above. This model, with fixed and random effects—Eq. (1)—, would be expressed as \({\hat{Y}}_{{ij}}=3.83+\left(-0.21\right)* {{\rm{time}}}\), implying that the square root of income decreases by 0.21 for each year. This model is depicted in Fig. 1. Gray lines represent the observed monthly income over time. The red line represents the line fitted by the above equation. Note that a single model would be insufficient to account for the observed trajectories: while income grows for some individuals, it decreases for others and at different rates. Therefore, it is appropriate to resort to the modeling of earnings trajectories (Vargas-Chanes and Valdés-Cruz 2019).

We use the LGMM model to identify clusters of earnings trajectories. A necessary step in moving forward in this regard is to select the number of latent classes considered appropriate. We resort here to the five criteria usually used in latent class analysis and indicated in the previous section. Table 2 shows the LGMM fit statistics. The two- and five-latent class solutions are easily rejected since they fail to meet most of the above criteria. In contrast, the three- and four-class solutions satisfy most of the criteria and have both advantages and limitations. Thus, for example, the four-class latent model does not meet the Lo-Mendel Rubin test, whereas the three-class model does so. Nonetheless, the three-class model has a lower entropy coefficient than that of the four-class model, suggesting poorer clustering. Taking these advantages and limitations into account, we select the three-class solution because it meets most of the criteria and provides greater explanatory parsimony.

As a result of the application of this procedure, three classes of trajectories can be identified among the employed population in 2019. For each of the classes, we fit an LGC model and evaluate its characteristics (see Table 3). As in any classification analysis, LGMM is a useful tool if it can generate analytically substantive groups. The analysis of the coefficients of the fitted models in Table 3 provides clues about the specificity of each class of trajectories.

The first class of trajectories is called “slightly upward” (n = 612). Individuals with increased labor income between 2019 and 2023 belong to this class. For this group, Eq. (1) would be expressed as \({\hat{Y}}_{{ij}}=4.78+0.24* {{\rm{time}}}\). When the intercept of the model is taken into account, it is evident that this group not only increases its income over time but also has a higher starting point than that of individuals in the rest of the classes. The second class of trajectories is called “slightly upward” (n = 1193) and corresponds to the equation \({\hat{Y}}_{{ij}}=3.64+(-0.07)* {{\rm{time}}}\). This group consists of individuals whose average income declines over time, but moderately. The third class of trajectories is called “sharply downward” (n = 866), and its general equation is \({\hat{Y}}_{{ij}}=3.40+(-0.72)* {{\rm{time}}}\).

The latent trajectory class analysis thus offers an important first conclusion about labor market dynamics and inequality. Although the post-pandemic years had a negative impact in terms of earnings, employed individuals experienced different types of trajectories. Some managed to have positive earnings trajectories, some maintained or slightly declined them, and some lost sharply. Figure 2 shows the different types of estimated trajectories.

Factors associated with belonging to the different classes

The descriptive evaluation of the three classes identified provides relevant clues to understanding the profile of workers who experienced diverse trajectories (Table 4).

The “slightly upward” trajectory is clearly identified with men. In contrast, women are much more likely to experience downward economic trajectories. Not surprisingly, 80.9% of those who experienced “slightly upward” trajectories are heads of households, compared to only 51.4% of those who experienced “sharply downward trajectories”. Age seems to play a less important role in the identification of trajectories.Footnote 6

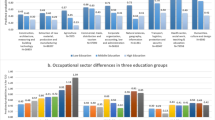

When considering the EDSA socioeconomic level index (Bonfiglio et al. 2023)—rescaled to vary between 0 and 1—, it is observed that the different trajectories could have strengthened previous inequalities. Indeed, individuals who had ascending economic trajectories have a difference of almost 20 p.p. in comparison to those who had descending trajectories. In this regard, individuals with higher educational qualifications had a greater chance of experiencing upward trajectories than less educated ones: 63.6% of those who completed university or more, compared to only 24.1% and 22.6% of those who had unchanged or declining experiences, respectively.

In occupational terms, these trajectories are also clearly identified. Even if individuals might have changed their occupational position during the whole period, upward trajectories are strongly referred to workers that in \({t}_{0}\) belonged to productive units in the formal sector (only 28.9% worked in small units in the informal sector). In contrast, only 37.5% of those with “sharply downward” trajectories had this occupational position in \({t}_{0}\). Likewise, individuals with upward trajectories had a higher probability of being fully employed and affiliated to social security in \({t}_{0}\). All the descriptions provided in this paper consider the variables at \({t}_{0}\).Footnote 7 than those who experienced downward trajectories. Finally, the occupational category in \({t}_{0}\) appears to imply no relevant differences in terms of the type of trajectory experienced.

The multinomial logistic regression analysis enables modeling the probability of belonging to each class and examining the weight of each of the variables considered. Table 5 shows the RRRs of two models. In the first one, variables are incorporated individually; in the second one, an interaction between the sector (formal/informal) and the occupational category (salaried/non-salaried) is presented. Independent variables are always referred to \({t}_{0}\).

This modeling allows indicating the relevance of some of the variables previously considered. Thus, for example, gender is a determining variable in the type of economic trajectory: men had significantly more opportunities to experience “upward” trajectories than “downward” ones (the comparison category in both models) compared to women. Something similar occurred among heads of household, as opposed to “secondary workers”. Age could have had an effect, although only observable among individuals aged 45 years or more: these employed individuals had significantly more opportunities to have “downward” trajectories compared to young people and middle-aged adults. This result suggests that an important part of the “downward” trajectories could be due to a process of exit from the labor market by older people, which translated into a reduction in their monthly income.

The most relevant variable in the model is education. Given the fact that highly educated individuals had the greatest opportunities to experience positive trajectories. In particular, those with an education level of high school or more were able to take advantage of the socioeconomic opportunities of the post pandemic to a large extent and saw their monthly labor income increase, though moderately. In contrast, the effect is much smaller when examining unchanged or “slightly downward” trajectories, suggesting that the latter were significantly more cross-sectional in the labor market.

The strictly occupational variables of the starting point appear to have less explanatory capacity than the sociodemographic variables. The only variable that remains relevant is belonging to the informal sector: informal workers were significantly more likely to experience downward rather than upward trajectories, experienced mainly by workers in the formal sector. In this sense, the second model, which presents the sector variable in interaction with the occupational category, highlights that salaried workers in the informal sector were the most likely to experience downward economic trajectories.

Discussion

To what extent is the forced interruption of a career trajectory, rather than labor mobility itself, what negatively impacts individuals’ well-being and increases their social vulnerability in regulated labor markets? As noted in the literature review, empirical evidence indicates that those who face episodes of unemployment in such markets tend to reintegrate into lower-quality jobs with reduced earnings (Nickell et al. 2002; Buchelli and Furtado 2002). Although career interruptions are not necessarily linked to recessions or economic crises, the economic cycle—whether during phases of crisis or expansion—influences the frequency of job changes, the types of transitions that occur and income trajectories (Levy 2008; Verd and López-Andreu 2012).

In integrated labor markets, beyond the collateral effects of regulations, productive and organizational changes or economic crises often lead to increased unemployment due to job losses. This immediately implies partial or total income loss. However, these scenarios can also create economic opportunities for individuals with the appropriate qualifications. During expansion phases, these markets not only tend to offer greater employment opportunities, but also widespread improvements in wages (Heinz 2004). However, how do these processes unfold in economies with heterogeneous productive structures, segmented labor markets and high levels of informality?

While many studies have explored these phenomena, empirical research analyzing the relationship between the economic cycle, labor mobility and income changes through longitudinal tracking of trajectories remains scarce. In this regard, analyzing income trajectories in the Argentine labor market during the COVID-19 health crisis—with its profound economic, social, and organizational implications—provides an exceptional case from which to draw key lessons.

Studies based on dynamic data show that, for most groups defined by gender, age, education level and occupational characteristics, employment levels 1 year after the onset of the pandemic were relatively similar to those of the pre-pandemic period. However, these studies also report an increase in precarious employment and a decline in wages, especially among young workers, women, and informal employees (Donza et al. 2022; Fernández and Maurizio 2022; Fernández and Monsalvo 2023). Self-employed workers, particularly those in the informal sector, were the first to return to the labor market, followed by formal wage earners. Nevertheless, this recovery was accompanied by a rise in precarious employment rates compared to the pre-pandemic period (Donza et al. 2022).Footnote 8

Despite these advances, few studies have addressed income trajectories in these contexts. Our findings show that, in contrast to the relative income stability experienced by workers in more productive formal segments, the income of informal workers followed a regressive trajectory both during the crisis and the recovery phase. Forced employment interruptions, combined with the greater instability and job turnover characteristic of the informal sector, negatively affected these workers’ incomes. These findings reaffirm that labor segmentation in heterogeneous markets is not inconsequential in terms of its effects on income trajectories.

Although outside the pandemic context, these results are consistent with previous research conducted in other countries in the region through trajectory analysis. For example, a longitudinal study in metropolitan areas of Brazil (Ruesga et al. 2014) found that labor instability among informal workers tends to result in prolonged income losses. Similarly, Pacheco and Parker (2001) analyzed labor market entry and exit dynamics during two crises in Mexico and concluded that transitions to informal salaried jobs and migration to poorer regions were associated with conditional mobility, which has regressive effects on income.

However, other studies in Mexico based on panel data have reached different conclusions. For instance, Duval Hernández (2007) found that, between 1987 and 2002, in a context of widespread crisis, formal sector workers experienced greater relative income losses. Similarly, Cunningham and Maloney (2000) did not identify significant income losses for workers transitioning to informality. Levy (2008) also concluded that, while average wages are higher in the formal sector, this does not necessarily imply that workers migrating to the informal sector experience income declines.

These findings challenge the existence of strict segmentation in labor markets, as they reveal a degree of fluidity between the formal and informal sectors, with neutral or even positive effects on income within the informal sector. However, our results strongly contradict these conclusions by showing divergent trajectories between the formal and informal sectors. This underscores the need for continued empirical evidence to obtain a better understanding of occupational dynamics in economies with high levels of informality, particularly in contexts of crisis, reforms or productive transformations.

Aligned with this, our findings also contradict part of the literature regarding the protective role of labor relations tied to social security systems in occupational and income trajectories. Although the absence of such protections tends to increase labor instability, as noted by Verd and López-Andreu (2012), our findings suggest that, in the studied context, social security affiliation did not have a significant role on preventing downward income trajectories. This may indicate that the economic downturn was pervasive across the labor structure and that the available social protections were insufficient to mitigate this impact.

Although further research is warranted, the evidence presented in this article supports the thesis of divergent economic trajectories based on educational qualifications (Autor and Dorn 2013). As a matter of fact, according to our findings, workers with higher qualifications were more likely to experience upward economic trajectories in a clearly regressive context. Conversely, we report that intermediate levels of qualification do not lead to upward trajectories but rather serve as protection against abrupt downward trajectories, consistent with previous research on labor quality in Spain (Verd and López-Andreu 2012).

Furthermore, the study provides relevant evidence on how occupational trajectories are influenced by gender inequalities. There is extensive literature documenting wage penalties faced by women (Blau and Kahn 2017). Trombetta and Cabezón Cruz (2020) report that in Argentina the gender wage gap is 14% in favor of men. From a dynamic perspective, our research shows that women are more likely to experience income losses than men. This result can be explained by occupational segregation—where women are more likely to be employed in lower-paying and less stable jobs—as well as by the discontinuity of their career paths (Marchionni et al. 2019).

On the other hand, the relationship between economic trajectories and socio-residential segregation shows ambiguous results. Descriptive analyses align with the literature on spatial segregation and “neighborhood effects” (Galster and Sharkey 2017), showing a strong association between low income, precarious working conditions and poverty based on social environment (Bonfiglio et al. 2023). However, when controlling for other factors in multivariate models, this variable was not significant, suggesting that its effects may be mediated by variables such as job type and education level.

Conclusion

The present paper aimed to contribute to the study of occupational mobility in segmented labor markets by examining earnings trajectories in a panel of urban workers in Argentina throughout the economic and health crises caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and its subsequent economic recovery. We thus sought to provide new empirical evidence to the still scarce literature addressing the role of structural productive heterogeneity—proper of dual economies—on income inequalities.

Using LGC models, it was possible to identify three types of dominant trajectories in real salaries for that period: downward, stable, and upward. Logistic regression models were used to characterize and identify the factors underlying these trajectories, taking into account sectoral and institutional variables as well as other variables related to the social profile of the labor supply (qualification, gender, age, etc.). This allowed assessing the conditional impact of such factors on the different types of trajectories identified.

Our findings support the empirical literature on mobility that highlights the regressive role of labor market segmentation on the income of certain groups of workers. In addition, they reinforce the idea that labor trajectories are not random, but rather respond to patterns of segmentation in terms of production, institutions and social profile. This paper confirms processes of linear transitions that can be described as divergent.

On the one hand, downward economic trajectories affect to a greater extent workers in the informal sector, low-skilled workers, workers with low or no social protection, and groups affected by social segregation processes (e.g., women, young people, and residents of segregated neighborhoods). In all cases, the described effect is one of an accumulation of disadvantages, which translates at the level of the labor structure a process of occupational hysteresis. On the other hand, stable and slightly upward trajectories can lead to a better socioeconomic level, especially among those who are employed in formal economic units, salaried or non-salaried, and affiliated with social security; this occurs particularly if they have medium or high educational qualifications, are men and middle-aged.

We conclude that further research on occupational mobility in general and earnings trajectories in particular is critical for assessing the impact of crises or accelerated technological changes in segmented labor markets. The lack of attention to these specific dynamics may restrict the effectiveness of policies designed to improve labor quality and reduce labor disparities in labor markets with marked structural heterogeneity. Therefore, our research provides not only insight into the complex interactions between individuals and the labor market, but also valuable information for policymakers.

Labor institutions based on permanent and stable jobs have been challenged for several decades by global trends such as productive reconversion, labor flexibility, and precariousness. The situation is aggravated in dual economies with segmented labor markets. In these societies, these facts support the need to reconfigure the social protection system to support individuals—regardless of their segment or occupational trajectory—when they face social risks and labor instability throughout their life cycle.

The theoretical debate on the existence of wage segmentation processes in economies with high informality rates, linked to labor mobility transitions and dynamics, carries significant implications for public policy. Broadly speaking, dualist models provide a rationale for policies aimed at allocating more resources to the formal sector to reduce informality and alleviate poverty. Neoclassical models, on the other hand, assume that institutional legality differences operate within integrated markets. If income disparities between sectors reflect productivity differences and labor markets are integrated, policies aimed at promoting formal employment are unlikely to yield substantial improvements in overall welfare (Amaral and Quinti 2006). However, if income gaps are indeed tied to productivity differentials but markets are segmented, efforts to liberalize formal sector employment and promote the informal economy are likely to result in greater labor mobility between sectors, while maintaining or even increasing poverty levels, alongside growing social inequalities.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Notes

An important implication of segmentation is its impact on economic efficiency: in a segmented economy, the allocation of the labor force is not Pareto-efficient, as redistribution across sectors could increase national output. Therefore, segmentation represents a market failure. The origins of this approach can be found in American institutionalists such as Doeringer and Piore (1971) and structuralists such as Reich et al. (1973). Latin American versions of this perspective can be found in Souza and Tokman (1976) and Tokman (1987).

The informal sector in the region is characterized by small-scale activities, intensive use of unskilled labor, and self-financing (Infante 2011; Abramo 2021). Currently, both neoclassical and structuralist literature tend to agree—albeit for different reasons—that the existence of extensive informal labor sectors is strongly correlated with the level of productive development, its internal heterogeneity, and the quality of its institutions (Weller and Kaldewei 2014; Abramo 2021; Amaral and Quinti 2006). However, a key difference between these approaches lies in whether labor markets are integrated or segmented (Amaral and Quinti 2006), and whether these conditions produce “escape” or “exclusion” effects (Perry et al. 2007).

This study follows the structural-institutionalist assumption formalized by ECLAC (2010, 2018), which posits that, in a dualistic context characterized by absolute labor surpluses, wage inequality and occupational formality gaps are fundamentally linked to productivity differentials, access to various markets, and specific forms of labor organization across firms and sectors. These inequalities are thus associated with a functional segmentation of labor markets and their institutions. Such systems tend to perpetuate labor markets segmented along social, occupational, and income lines (Salvia 2012).

The EDSA typically conducts interviews in person, except for 20% of households in the upper strata, where telephone interviews are used. The health restrictions imposed in 2020 required telephone interviews to be employed as the sole data collection method. This change, along with other challenges, resulted in a higher case attrition rate compared to previous years. As explained in Tinoboras and Donza (2024), the EDSA 2020 data should be considered with reservation due to methodological changes introduced in the context of the pandemic COVID-19.

Of these, 1957 were surveyed twice, 489 were surveyed three times, 164 were surveyed four times and 61 were surveyed more than for times. Cases with less than five records were imputed following the indicated procedure. A review of imputation methods for growth mixture models is available in Lee and Harring (2023).

The Socioeconomic Level Index is constructed from a principal components analysis with household goods and services and occupational and educational characteristics of the head (see Bonfiglio et al. 2023, 20–23 for more details). Table 4 shows the average as well as the upper and lower quartiles. The “informal sector” indicator includes all persons employed in micro-units (up to 5 persons, whether employees or employers), domestic service workers and non-professional self-employed. “Full employment” refers to employees working more than 35 h per week. Persons affiliated to social security are those who pay contributions both from their employer and from themselves. Finally, we present a neighborhood type indicator derived from a visual report (slums) and based on the socio-educational and infrastructural characteristics of the radius in which the household is located (Bonfiglio et al. 2023).

Of these, 1957 were surveyed twice, 489 were surveyed three times, 164 were surveyed four times and 61 were surveyed more than for times. Cases with less than five records were imputed following the indicated procedure. A review of imputation methods for growth mixture models is available in Lee and Harring (2023).

Similarly, Maurizio et al. (2023) examines, from a dynamic and comparative perspective, the labor transitions triggered by the pandemic in six Latin American countries, with a particular focus on movements related to labor informality during this period. Unlike previous crises, the decline in informal occupations exacerbated the overall contraction in employment. In contrast to this labor trend, transitions from informal to formal jobs dropped significantly during the most critical phase of the crisis. The partial recovery of employment from mid-2020 onward was driven by an increase in informal jobs.

References

Abramo L (2021) Políticas para enfrentar los desafíos de las antiguas y nuevas formas de informalidad en América Latina, serie Políticas Sociales, N° 240. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), Santiago. https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/9332d331-9c59-40c6-be67-18d3a3bcb769/content

Acemoglu D, Autor D (2011) Skills, tasks and technologies: implications for employment and earnings. In: Handbook of labour economics, vol 4. Amsterdam: Elsevier-North, pp 1043–1171. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-7218(11)02410-5

Acevedo I, Castellani F, Cota MJ, Lotti G, Székely M (2023) Higher inequality in Latin America: a collateral effect of the pandemic. Int Rev Appl Econ 38(3):280–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2023.2200993

Amaral PS, Quintin E (2006) A competitive model of the informal sector. J Monet Econ 53(7):1541–1553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2005.07.016epublications.vu.lt+2

Andersson M, Palacio Chaverra A (2016) Structural change and income inequality–agricultural development and inter-sectoral dualism in the developing world, 1960-2010. Oasis 23:99–122. https://doi.org/10.18601/16577558.n23.06

Autor D, Dorn D (2013) The growth of low-skill service jobs and the polarization of the US labor market. Am Econ Rev 103(5):1535–1597. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.5.1553

Autor D (2010) The polarization of job opportunities in the US labor market: implications for employment and earnings. Community Invest 23:11–16. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227437438_The_Polarization_of_Job_Opportunities_in_the_US_Labor_Market_Implications_for_Employment_and_Earnings

Azevedo JP, Dávalos ME, Díaz-Bonilla C, Atuesta B, Castañeda RA (2013) Fifteen years of inequality in Latin America: How have labor markets helped? (Policy Research Working Paper No. 6384). World Bank. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2233243

Beccaria L, Bertranou F, Maurizio R (2022) COVID‐19 in Latin America: the effects of an unprecedented crisis on employment and income. Int Labour Rev 161(1):83–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12361

Beccaria L, Groisman F (2016) Informalidad y segmentación del mercado laboral: El caso de la Argentina. Rev de la CEPAL 2015(117):127–143. https://doi.org/10.18356/4d859903-es

Bertranou F, Casanova L (2015) Las instituciones laborales y el desempeño del mercado de trabajo en la Argentina. OIT, Buenos Aires. https://www.ilo.org/es/publications/las-instituciones-laborales-y-desempeno-del-mercado-de-trabajo-en-argentina

Blau FD, Kahn LM (2017) The gender wage gap: extent, trends and explanations. J Econ Lit 55(3):789–930. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20160995

Bonacini L, Gallo G, Scicchitano S (2021) Working from home and income inequality: risks of a ‘new normal’ with COVID-19. J Popul Econ 34(1):303–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00800-7

Bonfiglio JI, Vera J, Salvia A (2023) Radiografía de la pobreza en Argentina: privaciones sociales y desigualdades estructurales. EDUCA, Buenos Aires. https://wadmin.uca.edu.ar/public/ckeditor/Observatorio%20Deuda%20Social/Documentos/2023/Observatorio_Documento%20Estadistico_Pobreza_2023.pdf

Bucheli M, Furtado M (2002) Impacto del desempleo sobre el salario: el caso de Uruguay. Desarro Econ 42(165):63–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/3455977

Buera F, Kaboski J, Rogerson R (2015) Skill biased structural change, Working Paper 21165, National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w21165/w21165.pdf

Carbonero F, Ernst E, Weber E (2020) Robots worldwide: the impact of automation on employment and trade. Leibniz Information Centre for Economics, Kiel, Hamburg. https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/vfsc20/224602.html

Casarico A, Lattanzio S (2022) The heterogeneous effects of COVID-19 on labor market flows: evidence from administrative data. J Econ Inequal 20:537–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-021-09522-6

Cerqua A, Letta M (2022) Local inequalities of the COVID-19 crisis. Reg Sci Urban Econ 92:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2021.103752

Chong A, Gradstein M (2007) Inequality and informality. J Public Econ 91(1-2):159–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2006.08.001

Ciaschi M, Galeano L, Gasparini L (2021) Estructura productiva y desigualdad salarial: Evidencia para América Latina. Documentos de trabajo del CEDLAS No. 250, septiembre 2019, Universidad Nacional de la Plata. https://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar/wp/wp-content/uploads/doc_cedlas250.pdf

Clark AE, D’Ambrosio C, Lepinteur A (2021) The fall in income inequality during COVID-19 in four European countries. J Econ Inequal 19:489–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-021-09499-2

Clark T, Bradburn M, Love S, Altman DG (2003) Survival analysis part I: basic concepts and first analyses. Br J Cancer 89:232–238. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601118

Cortes G, Forsythe E (2023) Heterogeneous labor market impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. ILR Rev 76(1):3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939221076856

Cunningham W, Maloney W (2000) Measuring vulnerability: who suffered in the 1995 Mexican crisis? Mimeo. https://ftp.itam.mx/pub/investigadores/delnegro/alcala/mal_p.pdf

Delaporte I, Escobar J, Peña W (2021) The distributional consequences of social distancing on poverty and labour income inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean. J Popul Econ 34:1.385–1.443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00854-1

Del Rio-Chanona RM, Mealy P, Beguerisse-Díaz M, Lafond F, Farmer JD (2021) Occupational mobility and automation: a data-driven network model. J R Soc Interface 18(174):20200898. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2020.0898

Doeringer P, Piore M (1971) Internal labor markets and manpower analysis. Mass-Healt, Lexington. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED048457.pdf

Donza E, Poy S, Salvia A (2022) Segmentación del mercado de trabajo y trayectorias laborales ante el impacto del COVID-19 en la Argentina urbana. Revista de la Carrera de Sociología 12(12):107–136. https://doi.org/10.62174/eyp.7865

Donza ER (2023) Escenario laboral en la Argentina del pos-covid-19: persistente heterogeneidad estructural en un contexto de leve recuperación del mercado de trabajo (2010-2022). EDUCA, Buenos Aires. https://wadmin.uca.edu.ar/public/ckeditor/Observatorio%20Deuda%20Social/Documentos/2023/Observatorio-DocumentoEstadistico_Trabajo_2023.pdf

Duval Hernández R (2007) Dynamics of labor market earnings in Urban Mexico, 1987-2002. Documentos de Trabajo, 401. CIDE, México. http://hdl.handle.net/11651/1183

Economic Commission for Latin America [ECLAC] (2010) La hora de la igualdad. Brechas por cerrar, caminos por abrir. ECLAC. https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/13309-la-hora-la-igualdad-brechas-cerrar-caminos-abrir-trigesimo-tercer-periodo

Economic Commission for Latin America [ECLAC] (2018) Eslabones de la desigualdad: heterogeneidad estructural, empleo y protección social. ECLAC. https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/27973-eslabones-la-desigualdad-heterogeneidad-estructural-empleo-proteccion-social

Economic Commission for Latin America [ECLAC]/International Labor Organization [ILO] (2020) El trabajo en tiempos de pandemia: desafíos frente a la enfermedad por coronavirus (COVID-19). ECLAC, Coyuntura Laboral en América Latina y el Caribe, No. 22 (LC/TS.2020/46). https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/45557-coyuntura-laboral-america-latina-caribe-trabajo-tiempos-pandemia-desafios-frente

Fernández AL, Monsalvo AP (2023) Crisis del covid-19 en Argentina: análisis de sus Implicancias heterogéneas sobre el empleo. Semestre Económico 26. http://hdl.handle.net/11407/8275

Fernández AL, Maurizio R (2022) A tres años de la irrupción de la pandemia por COVID-19 en América Latina y el Caribe. Un análisis de la dinámica laboral heterogénea entre hombres y mujeres. ´Desarrollo Económico Revista de Ciencias Sociales. https://revistas.ides.org.ar/desarrollo-economico/article/view/496

Galster G, Sharkey P (2017) Spatial foundations of inequality: a conceptual model and empirical overview. RSF Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci 3(2):1–33. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2017.3.2.01

Gil L, Rougier M (2023) El impacto del coronavirus en la industria manufacturera de la provincia de Buenos Aires. Documentos de trabajo del Instituto Interdisciplinario de Economía Política. (81):1–96. https://ojs.econ.uba.ar/index.php/DT-IIEP/issue/view/444

Heinz WR, Krüger H (2001) Life course: innovations and challenges for social research. Curr Sociol 49(2):29–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392101049002004

Heinz WR (2004) From work trajectories to negotiated careers: the contingent work life course. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ (eds) Handbook of the life course. Springer, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_9

Infante R (2011) Tendencias del grado de heterogeneidad estructural en América Latina, 1960-2008. In: Infante R (ed) El Desarrollo inclusivo en América Latina y El Caribe. CEPAL, Santiago de Chile, pp 65–94

International Labor Organization [ILO] (2023) Observatorio de la OIT sobre el mundo del trabajo. Undécima edición. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/briefingnote/wcms_883344.pdf

International Labor Organization [ILO] (2024) Perspectivas sociales y del empleo en el mundo. Tendencias 2024. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_908148.pdf

Grand CL (2002) Job mobility and earnings growth. Eur Sociol Rev 18(4):381–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/18.4.381

Lee DY, Harring JR (2023) Handling missing data in growth mixture models. J Educ Behav Stat 48(3):320–348. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986221149140

Levy S (2008) Buenas intenciones, malos resultados. Política social, informalidad y crecimiento económico en México. Océano, México. https://www.paginaspersonales.unam.mx/files/165/Buenas_intenciones_SLevy_Resumen.pdf

Manyika J, Lund S, Chui M, Bughin J, Woetzel J, Batra P, Sanghvi S (2017) Jobs lost, jobs gained: workforce transitions in a time of automation. McKinsey Glob Inst 150(1):1–148. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/public%20and%20social%20sector/our%20insights/what%20the%20future%20of%20work%20will%20mean%20for%20jobs%20skills%20and%20wages/mgi-jobs-lost-jobs-gained-executive-summary-december-6-2017.PDF

Marchionni M, Gasparini LC, Edo M (2019) Brechas de género en América Latina. Un estado de situación. https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/114192

Maurizio R, Monsalvo AP, Catania MS (2023) Short-term labour transitions and informality during the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America. J Labour Mark Res 57:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-023-00342-x

Mezzera J (1987) Abundancia como efecto de escasez. Oferta y demanda en el mercado laboral urbano. Nueva Sociedad No. 90. Julio-Agosto 1987. https://static.nuso.org/media/articles/downloads/1529_1.pdf

Nguena Nguefack HL, Pagé MG, Katz J, Choinière M, Vanasse A, Dorais M, Samb OM, Lacasse A (2020) Trajectory modelling techniques useful to epidemiological research: a comparative narrative review of approaches. Clin Epidemiol 1205–1222. https://doaj.org/article/cf0b087d0f3f45f8be233bd7653c9620

Nickell S, Jones P, Quintini G (2002) A picture of job insecurity facing British men. Econ J 112(476):1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.0j671

Pacheco E, Parker S (2001) Movilidad en el mercado de trabajo urbano: evidencias longitudinales para dos periodos de crisis en México. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 63(2):3–26. https://biblat.unam.mx/fr/revista/revista-mexicana-de-sociologia/articulo/movilidad-en-el-mercado-de-trabajo-urbano-evidencias-longitudinales-para-dos-periodos-de-crisis-en-mexico

Paz J (2013) Segmentación del mercado de trabajo en la Argentina. Rev Desarro Soc 72:105–156. https://doi.org/10.13043/dys.72.3

Perry G, Maloney W, Arias O, Fajnzylber P, Mason A, Saavedra-Chanduvi J, Bosch M (2007) Informalidad: escape y exclusión. Estudios del Banco Mundial sobre América Latina y el Caribe, 1. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/889371468313790669/pdf/400080PUB0SPAN101OFFICIAL0USE0ONLY1.pdf

Prieto C (2002) La degradación del empleo o la norma social del empleo flexibilizado. Sistema: Revista de Ciencias Sociales 168:89–106

Ruesga SM, Bicharra J, Monsueto SE (2014) Movilidad laboral, informalidad y desigualdad salarial en Brasil. Investig Econ 73:63–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0185-1667(14)70919-1

Reich M, Gordon DM, Edwards RC (1973) Dual labor markets: a theory of labor market segmentation. Am Econ Rev 63(2):359–365. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1817097

Salvia A (2012) La trampa neoliberal. Un estudio sobre los cambios en la heterogeneidad estructural y la distribución del ingreso en la Argentina: 1990-2003. EUDEBA, Buenos Aires. https://www.aacademica.org/agustin.salvia/109

Salvia A, Fachal MN, Robles R (2024) Desigualdades estructurales como límites a la equidad remunerativa. El caso de la principal región metropolitana de la Argentina (1974-2018). Rev Desarro Econ 64(242):1–29. https://doi.org/10.59339/de.v64i242.666

Souza PR, Tokman VE (1976) El sector informal urbano en América Latina. Rev Int Trab 94(3):385–397

Tinoboras C, Donza E (2024) Informe metodológico de la Encuesta de la Deuda Social Argentina. EDUCA, Buenos Aires. https://wadmin.uca.edu.ar/public/ckeditor/Observatorio%20Deuda%20Social/Documentos/2024/OBSERVATORIO-DOCUMENTO-METODOLOGICO-01_2024.pdf

Tokman VE (1987) El sector informal: quince años después. El Trimest Econ 54(3):513–536. http://aleph.academica.mx/jspui/handle/56789/5778

Trombetta M, Cabezón Cruz J (2020) Brecha salarial de género en la estructura productiva argentina. Documento de trabajo del CEP N°2. Centro de estudios para la producción—Ministerio de desarrollo productivo de la Nación. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/dt_2_-_brecha_salarial_de_genero.pdf

Vargas-Chanes D, Valdés-Cruz S (2019) A longitudinal study of social lag: regional inequalities of growth in Mexico 2000 to 2015. J Chin Sociol 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-019-0100-6

Velasco J (2021) Los impactos de la pandemia de la Covid-19 en los mercados laborales de América Latina. Compendium: Cuadernos de Economía y Administración. 8:99. https://doi.org/10.46677/compendium.v8i2.935; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354416020_Los_impactos_de_la_pandemia_de_la_Covid-19_en_los_mercados_laborales_de_America_Latina

Vera J (2015) Movilidad ocupacional en la Argentina en un contexto de heterogeneidad estructural. Cuad del CENDES 32(90):87–110. http://ve.scielo.org/pdf/cdc/v32n90/art05.pdf

Verd JM, López-Andreu M (2012) La inestabilidad del empleo en las trayectorias laborales. Un análisis cuantitativo. Reis 138:135–148. https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.138.135

Weller J (2020) La pandemia del COVID-19 y su efecto en las tendencias de los mercados laborales. Documentos de Proyectos (LC/TS.2020/67), Santiago, CEPAL. https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/26a2069d-f658-4727-89f4-02e4646750d2/content

Weller J (2022) Tendencias mundiales, pandemia de COVID-19 y desafíos de la inclusión laboral en América Latina y el Caribe. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366548536_Tendencias_mundiales_pandemia_de_COVID-19_y_desafios_de_la_inclusion_laboral_en_America_Latina_y_el_Caribe

Weller J, Kaldewei C (2014) Crecimiento económico, empleo, productividad e igualdad. Inestabilidad y desigualdad. La vulnerabilidad del crecimiento en América. Lat y el Caribe 128:61–103. https://doi.org/10.18356/9adc2806-es

Weller J, Gontero S, Campbell S (2019) Cambio tecnológico y empleo: una perspectiva latinoamericana. ECLAC, Santiago. https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/44637

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Fernando Gallegos for his outstanding research assistance, and Valentina Gonzalez Lodi for her thorough collaboration. This research was funded by Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS and SP equally contributed to the development and design of the study and interpretation of results. While AS developed the conceptual framework and gathered information on debates related to the topic, SP constructed the database and performed the statistical analysis of the data. Both authors analyzed the results, developed the manuscript and tables, in order to obtain the final version for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research did not involve human participants, their data, or any personal information. Therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Informed consent

As this study did not involve human participants or their data, informed consent was not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salvia, A., Poy, S. Earnings trajectories during a crisis in a segmented labor market: Argentina (2019–2023). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 700 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04968-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04968-9