Abstract

This study aims to understand how teleworking practices are implemented and developed in a Portuguese company after the COVID-19 pandemic, seeking to assess their gender dimension when balancing professional and family dynamics. Based on a case study, including 11 semi-structured interviews with the institution’s managers, four themes emerged: The company’s approach to telework; Telework: From COVID-19 to the ‘new normal’; The cultural conservatism of mistrust; Hybrid regime, matching interests. These results are accompanied by gender inequalities with impacts on women’s well-being due to the added tasks of housework or caregiving. To conclude, telework is here to stay with improvements towards flexwork.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To restrain the spread of COVID-19 and avoid the collapse of health services, in 2020, the world was forced to adopt isolation measures, including staying at home, restricting travel, and distancing between people (Wenham et al., 2020). In this context, professional work at home, frequently called telework, has become a reality (Arntz et al., 2020). Although it was already common practice in some activities, for many occupations, the adoption of teleworking from home became necessary and (in some cases) compulsory without any prior preparation or warning (Santos et al., 2023). Thus, people had to cope with new work-life balance needs that involved working often in adverse ergonomic conditions while simultaneously taking care of their children and household, managing multiple sources of distraction, and losing interaction with work colleagues (Arntz et al., 2020). Therefore, several studies have shown that working from home has both positive and negative consequences, depending on the demands of the job, the family set-up, or the conditions at home in which it is carried out, for instance (Fan & Moen, 2023; Majumdar et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2021).

The evolving landscape of the workplace demands a comprehensive understanding of employees’ current experiences in their work-life balance, as well as the challenges faced by the companies themselves. This exploratory study aims to understand how teleworking practices are implemented and developed in a national company after the pandemic. Specifically, this study adopts a lens informed by the work-family interface, exploring the tensions and negotiations that arise as individuals and organizations navigate the complexities of integrating work and family life within the context of telework (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Wharton, 2012). We will examine how organizational policies and practices shape the subjective experience of work and family, and how these experiences, in turn, influence individual well-being and organizational outcomes (Eby et al., 2005; Gareis et al., 2009). Particularly, this study aims to (i) characterize the organizational experience in implementing teleworking; (ii) access teleworking practices, dynamics, and measures implemented by a company in terms of time and work organization, performance and productivity management, communication, safety and health at work, and balancing professional and personal life; (iii) access the gender dimension in the company’s teleworking practices and the conciliation of professional and personal life.

Teleworking in organizations: tensions, transformations, and impact on Work-Life Interface

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly accelerated the adoption of teleworking, forcing organizations to adapt rapidly (Santos et al., 2023). Despite the pandemic’s decline, teleworking remains a prevalent work arrangement (Caraiani et al., 2023). This shift has prompted significant transformations in human resources management (Crawford, 2022; Ding, Ploeg, & Williams, 2024), with potential benefits including cost savings for both companies and workers, enhanced job satisfaction, reduced commuting stress, and increased productivity (Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Tavares, 2017). Studies have also demonstrated improved employee well-being and performance during teleworking days (Delanoeije & Verbruggen, 2020).

However, the transition to teleworking is not without its challenges. Organizations faced major challenges abruptly assimilating a new working routine without prior choice or preparation (Santos et al., 2023). Organizations must develop comprehensive plans to guide this work arrangement, addressing key tensions and providing necessary resources (Hamouche, 2020). This includes providing adequate information technology, quality equipment, and suitable conditions for their employees (Greer & Payne, 2014). Comprehensive training on technology usage, data protection regulations, and teleworking expectations is also crucial, not only to alleviate stress and anxiety among employees but also to enhance overall productivity (Mutiganda et al., 2022). Furthermore, traditional productivity assessment methods must be reevaluated, shifting towards results-based performance metrics (Athanasiadou & Theriou, 2021; Crawford, 2022). Assessing workers and productivity in the teleworking environment also requires significant transformations (Greer & Payne, 2014).

In addition to the advantages and disadvantages of teleworking on an organizational level, it is also important to highlight its impact on the individual dimension. Teleworking can blur the boundaries between work and personal life, leading to increased working hours and potential challenges to mental health (Tavares, 2017; Nijp et al., 2016; Toniolo-Barrios & Pitt 2021; Zołnierczyk-Zreda et al., 2012). Studies on the impact of teleworking on mental health have yielded mixed results, with some highlighting the benefits of autonomy and others emphasizing the negative effects of increased workload (Niebuhr et al., 2022). It has also been noted that telework can increase the number of hours employees dedicate to working. Difficulties in establishing clear boundaries between work and personal life have been highlighted as a disadvantage of working from home (Tavares, 2017).

The shift towards telework necessitates a careful examination of the interplay between work and family life, requiring a defined theoretical framework to guide the analysis (Wharton, 2012). Traditional views often treat work and family as separate spheres, requiring distinct skills and responsibilities (Wharton, 2012). However, the rise of teleworking blurs these boundaries, necessitating a re-evaluation of how individuals manage their participation in both domains (Moen & Roehling, 2005; Wharton, 2012). This study will be guided by an understanding of the work-family interface, recognizing the dynamic and often conflicting relationship between work and family roles (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985).

Within the work-family literature, two dominant perspectives emerge: one focusing on achieving work-life balance, and the other emphasizing the work-family conflict arising from the competing demands of these spheres (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). While the concept of work-life balance often implies a state of equilibrium, the reality of teleworking frequently involves navigating complex trade-offs and tensions (Kirchmeyer, 2000; Marks & MacDermid, 1996).

Teleworking has been found to both alleviate and intensify work-life conflict (Byron, 2005; Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2005; Wharton, 2012). Greater flexibility can enhance integration between work and personal life, yet it can also blur boundaries, increasing the risk of overwork and role strain. This phenomenon, termed the ‘flexibility paradox’, suggests that while employees have more control over their schedules, they often experience heightened organizational oversight and work intensification (Athanasiadou & Theriou, 2021). When experiencing the ‘flexibility paradox’ (Athanasiadou & Theriou, 2021), workers have more flexibility but often feel controlled by the organization. Still, the increased flexibility to organize priorities, workflow, and even work schedules are highlighted as advantages by the workers (Crawford, 2022). The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) can be used to analyze how job demands and resources impact employee well-being and work-life balance in the context of teleworking, considering the role of organizational practices in shaping these demands and resources. Organizational priorities when promoting teleworking should include team-building activities, the provision of social support, and employee assistance (Hamouche, 2020). These need to involve all workers, including managers (González-González et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2023).

Moreover, teleworking has exacerbated gender inequalities, with women often bearing a disproportionate burden of family care work (Otonkorpi-Lehtoranta et al., 2022; Wenham et al., 2020). Qualitative studies have indicated that teleworking can simultaneously contribute to enhancing work-life balance by providing more independence, autonomy, and flexibility. However, it can also perpetuate traditional family roles at home, such as gender constructions of time, reinforcing greater responsibilities for women in domestic settings (Costoya et al., 2022; Laat, 2023; Sullivan & Lewis, 2001). Research consistently indicates that the impact of teleworking is not gender-neutral, potentially reinforcing traditional gender roles (Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Emslie & Hunt, 2009; Fan & Moen, 2022). Thus, a comprehensive understanding of work-family dynamics in the context of teleworking must consider the gendered nature of these experiences and the ways in which organizational policies and practices may inadvertently perpetuate inequalities.

Methods

Study design

This study employs a qualitative approach, utilizing an exploratory case study design to investigate the implementation of telework within a Portuguese company following the COVID-19 pandemic (Ding et al., 2024; Gerring, 2004). The choice of a case study design is justified by its capacity to provide an in-depth understanding of a complex phenomenon within its real-world context, allowing for the exploration of the “how” and “why” of telework implementation (Gerring, 2004). The unit of analysis is the company, enabling the examination of the dynamics and perspectives of its members regarding telework. We carried out semi-structured interviews, performed non-participant observation, and collected data from the institution’s human resources (HR) department, thus understanding the participating company’s functioning and a general perception of its external and internal performance.

Participants

The participating company, referred to as “The Company” to ensure anonymity, is a medium-sized Portuguese organization with over two decades of experience in national and international markets. The Company operates in the infrastructure sector, focusing on the management and optimization of operations. With an approach driven by innovation and efficiency, it integrates technological and sustainable solutions into its processes. Details about its business activity will not be provided to preserve the company’s anonymity.

During data collection, The Company had around 800 employees, mostly men (66%). There were around 380 people in positions eligible for teleworking, but only 156 were effectively teleworking (88 women, 68 men). Of these, 47 women and 33 men had children. Most teleworkers had a degree (n = 78), followed by complete secondary education (n = 44), a Master’s degree (n = 25), a Postgraduate degree (n = 8), and a Ph.D (n = 1).

Specifically, this study involved 11 participants interviewed, encompassing individuals in diverse administrative positions, including directors and team managers. This selection reflects the organizational perspective these individuals can provide and the integrative knowledge of the experiences of employees they manage, thus meeting the aims of our research (Bañón & Sánchez, 2008). Most of the 11 interviewees have a bachelor’s or master’s degree, five women and six men, and their ages range from 38 to 61, with an average age of 50. Their positions range from team managers, heads of service, heads of specific departments, and service directors to general managers. All participants work directly with or manage teleworking teams. Participants self-identified ethnicity as: “White person/ Caucasian/ European.” No further socio-demographic data on the participants is disclosed to guarantee confidentiality and anonymity.

Data collection

The recruitment took place in a two-stage process. First, we looked for a national company, regardless of the area of business or activity where teleworking was considered. We used the digital channels of the project, the project promoter, partners, the funding organization, and the project manager to do so. Second, once the company has been set, we have recruited the participants to be interviewed. All participants received detailed information about the research and its objectives before explicitly agreeing to participate. Informed consent was obtained on the day of each participant’s interview and was reciprocally signed. As per ethical considerations, specific interview dates will not be disclosed. However, all consents were obtained between July and September 2023, the same period during which the interviews took place. Participant recruitment concluded upon reaching theoretical saturation (Van Rijnsoever, 2017).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by a team member, with an average duration of two hours. The interview protocol was developed based on a review of the literature on telework, work-life interface, and gender dynamics, and was designed to explore participants’ experiences and perspectives on these topics. The interview guide consisted of open-ended questions organized into four main sections: (1) Introduction and background information, (2) Characterization of the telework experience in the company, (3) Telework practices and well-being, and (4) Closing. Key questions included: “How would you describe your personal experience with telework?”, “What are the main advantages and disadvantages of telework from your perspective?”, and “How does the company address work-life balance for teleworking employees?”. All interviews were recorded in an audio format and later transcribed verbatim. All transcribed data was securely stored online on an encrypted drive accessed only through a registered, authorized log-in.

In addition to the semi-structured interviews, this study incorporated non-participant observation and data collected from the Human Resources (HR) department to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the organizational context. Non-participant observation involved observing the work environment and employee interactions at the company’s premises to contextualize the information obtained from the interviews. HR department data included demographic and statistical information on employees and the company’s telework practices. These data sources were integrated into the analysis to complement and enrich the interview data, providing a multifaceted view of telework implementation at the company. HR data collection occurred before and during the interview period, while non-participant observation was conducted concurrently with the interviews, allowing for a continuous and evolving understanding of the work environment.

Data analysis

We used Reflexive Thematic Analysis (TA) (Braun & Clarke, 2021) as an analytic strategy due to its potential to understand the explicit and implicit meanings of participant narratives, thus aligning with the epistemological positioning of the study as social constructionist (Burr, 1995), and with a broad gender perspective (e.g., Acker, 2006; Walby, 2020). The analysis process was developed by three researchers and followed the six-stage process for data engagement, coding, and theme development proposed by Braun and Clarke (2021). The authors translated excerpts from the interviews from Portuguese to English.

To provide clarity on the recursive process, we detail each stage as follows: (i) Familiarizing with Data: Researchers immersed in transcripts, recordings, field notes, and HR documents to deeply understand the data and identify initial patterns. (ii) Generating Initial Codes: Significant data features were systematically identified and inductively coded, with researchers independently coding and then comparing their findings. (iii) Searching for Themes: Initial codes were examined to find broader meaning patterns, clustering related codes to form overarching thematic concepts. (iv) Reviewing Themes: Candidate themes were rigorously reviewed against the data set, collaboratively refining, merging, or discarding themes as needed. (v) Defining and Naming Themes: Satisfactory themes were clearly defined and named, capturing their essence with informative and evocative labels. (vi) Producing the Report: Researchers integrated narrative, data extracts, and context to present themes coherently, contextualizing the analysis within existing literature.

Throughout these six phases, the researchers engaged in a reflexive dialog, regularly discussing their interpretations and decisions to ensure a rigorous and transparent analytic process. Consensus was reached through collaborative discussion and review, ensuring that the themes accurately reflected the participants’ experiences and perspectives.

Ethical consideration

All participants provided informed consent, and the confidentiality and anonymity of the collected data were ensured. All participants have been given fictitious names, and all interviews have been anonymized during the transcription.

Data analysis and discussion

Four main themes emerged from the analysis, interrelating with each other in a thematic network presented in Fig. 1. These themes will be individually and critically discussed below.

The Company’s approach to telework

Regarding implementing The Company’s telework, we highlight the meticulous formalization with no effective commitment. The Company ensures hygiene and safety while teleworking and complies with all legal requirements (Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Greer & Payne, 2014). The Company ensures that the employee has working conditions at home, uses surveys and photographic records to perform this verification, and invests in electronic equipment for remote working (Mutiganda et al., 2022). Regarding the formal officialization of teleworking, it is optional, and the renewable nature of the contract makes it ineffective, denouncing The Company’s restrained attitude towards teleworking, as Ivo explains: “Each person who joins The Company gets an addendum to the employment contract, (…) and it’s for periods of six months, so it’s renewable, there’s no obligation on The Company to keep doing it”.

In addition to the standard teleworking measures presented previously, The Company only pays full food allowance if people choose to telework for just one or two days a week, depending on the type of activity and the team the person is assigned to (Mutiganda et al., 2022). Edgar explains further on teleworking: “The Company doesn’t promote it, doesn’t encourage it, but it doesn’t inhibit it either. (…) For instance, (…) if a person asks for three teleworking days, The Company doesn’t pay full food allowance”.

Thus, we understand that The Company does not inhibit or encourage telework, as explained by Edgar. Furthermore, teleworking arrangements at The Company are also ‘An issue of matching interests’ because people who work at The Company are very interested in teleworking, highlighting the advantages of working remotely, and expressing their intention to continue and, if possible, extend the period of teleworking, while managers are less in favor of teleworking:

I would say that the rules that are in place, I think they will be in place for some time. Of course, I won’t hide from you the fact that (…) the enthusiasm of managers for teleworking is not… It’s not extraordinary. (…) On the other hand, people from… who work in, let’s say, less qualified areas, see enormous advantages, both in terms of savings and in terms of managing family life… and so there is an issue here, at the end of the day, of matching interests, isn’t there? (Ivo)

At The Company, telework implementation enables an issue of matching interests (employer vs. employees) and presents a solution to market competitiveness (Morris et al., 2023; Mutiganda et al., 2022; Raišienė et al., 2021), as André explains, referring to the implementation of teleworking by The Company: “I think that this situation of The Company is more about not losing competitiveness because, in fact, it’s something that people value a lot nowadays”.

Therefore, in The Company, telework is neither inhibited nor encouraged; it is a way of matching employees’ and employers’ interests, perceived as an added value provided by The Company. Telework has emerged as a measure to respond to some employees’ expectations, as it is highly valued, making them more satisfied and motivated, thus functioning as a tool to retain staff. However, from The Company’s perspective, telework should be restrained. Thus, reducing food allowance for those who telework more than two days a week or establishing a temporary teleworking contract represents those restraint measures. Nonetheless, by accessing The Company’s approach to teleworking, we understand that telework is here to stay (Ameen et al., 2023; Caraiani et al., 2023; Raišienė et al., 2021).

Telework: from COVID-19 to the ‘new normal’

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to lockdowns, thus requiring teleworking (Arntz et al., 2020; Athanasiadou & Theriou, 2021; Caraiani et al., 2023). Many firms, such as The Company, have massively embraced teleworking during the pandemic.

Nowadays, teleworking is no longer mandatory. However, many people continue to choose to work from home (Ameen et al., 2023). Telework is here to stay (Arntz et al., 2020; Caraiani et al., 2023), but in a fluid way, as Ivo explains:

I would say that teleworking, (…) I’m convinced that it’s here to stay in very fluid ways. It must be very well adapted…(…) So today, what would be my epidermal reaction to telework isn’t anymore because I’m aware that’s also the way forward. I think the way forward is through very diverse working schemes, both in terms of physical location and teleworking. The world is changing so much that I think everything will be much more fluid. (Ivo)

This fluidity refers to the flexibility of working formats, which we will discuss further (Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Mutiganda et al., 2022), but also refers to the volatility of working conditions, recognizing it as changeable. Ivo explains that initially, he personally had some resistance to telework, but today he recognizes the working formats changed, and now telework is part of it.

In addition to the fact that teleworking is here to stay, we realize that this ‘new reality’ (Arntz et al., 2020; Caraiani et al., 2023) is likely to happen due to experience with the COVID-19 pandemic, despite being hopeless, showed very positive results in terms of its viability (Santos et al., 2023). On the success of the teleworking experience in pandemic times, Gisela adds:

There were people who said: ‘I’ve discovered a new reality, I never imagined that working from home would make me a better person, more productive… feeling better personally because I have more time for my family (…) Those two hours a day I used to spend in traffic, now I have time to spend with my children. (Gisela)

Gisela illustrates telework as the ‘new normal’, enabled by the experience of teleworking during the pandemic, and announces the subtheme: The reasons why employees choose to telework. These reasons can be found in The Company’s internal surveys and were also shared directly by the employees with their team leaders. Balancing work with cohabitation/family, saving time and money on commuting, and gaining time to promote personal well-being through sports and leisure are the main reasons for choosing teleworking (Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Sullivan & Lewis, 2001; Tavares, 2017):

It has to do with cost issues so that people can reduce their travel costs in time and money… It has to do with issues of balancing personal life on some days, issues with children, issues with dependent family members… (…) And then a bit of that quality-of-life rationale. (João)

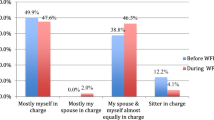

These reasons have, however, implicit gender differences. On the one hand, women request telework for reasons linked to family balance: caring for children and dependent adults (Çoban, 2022; Crawford, 2022), while men tend to request telework to invest in quality of life and more time for sport and leisure (Sullivan & Lewis, 2001):

From the requests we’ve had for flexibilization (…) it’s always the woman who is responsible for the child, who is responsible for the school (…) and, therefore, usually the request always comes from the woman and never from the man. (…) In my 20-something years of experience, (…) I don’t remember a request from a man saying: ‘Look, I need to make my working hours more flexible because I have to pick up my son from school (…)’. No. And I have dozens of examples of… women who have made this request to me, so it shows there is still an imbalance here. (João)

These gender differences reveal that gender inequality persists, with the burden of domestic chores and family care more often assigned to women (e.g., Atkinson, 2022; Otonkorpi-Lehtoranta et al., 2022). With teleworking, gender differences might become visible and accentuated (Arntz et al., 2020; Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Rinaldo & Whalen, 2023):

Women, who already have a heavier workload, when they’re working remotely, this is accentuated… (…) one of these days, I don’t know who was saying this to me: ‘Oh I can even do the laundry between meetings… I can even bring dinner forward before lunchtime’, and I don’t hear men using that language. I don’t realize that, on the men’s side, the advantages they point out for teleworking translate into what in gender terms have been the great dissonances. (Gisela)

As Gisela points out, teleworking from home makes it possible to get ahead on household chores and allows greater flexibility and conciliation when caring for others (Sullivan & Lewis, 2001). However, by doing the laundry or bringing dinner forward, women are targeting their time gains externally, overriding their own personal and individual priorities, and not investing in their well-being. Our results follow Çoban’s study (2022) in which women, who save time by teleworking and not having to commute to the office, transfer this time to caring for their home and children and take it away from personal investment and their career.

Therefore, it is also significant to emphasize the consequences of teleworking presented by The Company’s managers giving voice to employees’ experiences but also to their own. These consequences follow the reasons previously presented: teleworking might promote greater well-being since it reduces commuting, provides greater flexibility and availability for leisure, family and/or friends, to household issues, thus increases motivation and productivity (e.g., Atkinson, 2022; Lange & Kayser, 2022; Magalhães et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2021), as “the employees are undoubtedly more satisfied” (André). The participants also warn of the dangers to teleworkers’ mental health (Majumdar et al., 2020; Toniolo-Barrios & Pitt, 2021). Teleworking might increase stress, anxiety, and fatigue through presenteeism and social isolation and could also promote declining physical activity, whereas working in virtual environments can be a source of stress or result in the increased number of (tele)working hours (e.g., Atkinson, 2022; Lange & Kayser, 2022; Magalhães et al., 2020; Niebuhr et al., 2022; Nijp et al., 2016):

When a person is at home, sometimes they tend to work more, work longer hours, why? Because they’re at home, because they don’t have to go out to catch the bus to go home, and when they're here [at The Company’s premises], they leave at 6 pm and get home at 8 pm. At home, they’re still working from 6 to 8 pm, and it goes unnoticed… They don’t have the stress of the traffic, that tiredness of commuting, but they do have the physical and psychological strain of a job that, instead of being 8 h a day, translates into 10, 12, or 14 (Catarina).

The two faces of telework can both benefit and harm the worker (e.g., Atkinson, 2022; Lange & Kayser, 2022; Magalhães et al., 2020). Thus, we realize the subjectivity of this content and that it depends on personal characteristics, the context in which they work, and the type of job and tasks, so it can work for some and be challenging for others, as telework doesn’t suit everyone similarly.

On an individual level, teleworking can have two sides, but for The Company, the consequences seem mostly beneficial. The participants in this study consensually revealed that: ‘In terms of performance, telework is transparent’. The employee’s performance is not dependent on their workplace or, to explore a later theme, it is not dependent on the control and surveillance that a company may place on them (Athanasiadou & Theriou, 2021; Crawford, 2022). The participants revealed that:

Today we know (…) there is no loss of productivity due to people teleworking. (…) So we haven’t encountered any case that makes us doubt this conclusion. We’ve never had anyone who performs well here and then goes home and performs badly, nor has there ever been a miracle of someone performing badly here and then performing well at home. (…) Therefore, in terms of performance, teleworking is transparent. (André)

These results are consistent with Martin and MacDonnell (2012) meta-analysis, which shows a positive relationship between telework, performance, and productivity. They highlight the advantages of this modality and the risks to productivity seem to be more linked to the management challenge (González-González et al., 2022).

With this thematic exploration, we have also realized there are challenges for remote team management. Managing teams in hybrid teleworking schemes involves additional challenges for conciliating those at The Company and those working remotely (Dambrin, 2004; González-González et al., 2022; Greer & Payne, 2014; Karia & Asaari, 2016; Türkeș & Vuță, 2022). Consequently, these arise in communication, especially with teleworkers, as communication is more restricted, time-consuming if written, prone to failures and misinterpretations, and dependent on the availability for calls. On the other hand, it seems that there are gains in communication and face-to-face work, with practical results and more direct ways of solving problems:

There isn’t a day when they [employees] don’t come here (…) ‘Oh Filipa, this, this and this’, it’s much quicker than typing on Teams (…) Then the written is different from the spoken because (…) A comma, or the lack of one, can be… perceived differently, isn’t it? So, I just call them. (…) And… and sometimes people aren’t available, (…) and the work is left hanging. Yes, and the contact with the other teams… Solving situations, going upstairs and sitting down with the other person and saying ‘look, I’ve got this, this, this’, is much more agile, much more efficient than doing it via Teams. (Filipa)

Following the challenges presented previously, we emphasize the risk of interpersonal (team) disconnection (Stoian et al., 2022) and of forgetting people not in the workplace. ‘Who is not seen is forgotten’ refers not only to the greater difficulty of personal relationships between team members but also the creation of a greater distance between the manager and the team, penalizing those who are not present in the workplace:

People teleworking (…) they lose the connection with the people they work with, or rather, they don’t even gain it. It’s more difficult, with this idea of teleworking, to keep people connected to each other and connected to The Company. This happens organically. And even we, the team managers, aren’t exactly prepared for this reality of having people working remotely, (…) we forget about them very easily (…). There are even situations in which we hold meetings and forget to call the person working from home. We don’t yet have a mindset evolved enough to escape the slogan: ‘Who is not seen is forgotten’. And so, we tend to forget about the people at home. (André)

The need lies in the preparation and training of team leaders to know how to manage both on-site and remote work, how to articulate these independently and collectively, and thus prevent teleworkers from being forgotten (González-González et al., 2022; Karia & Asaari, 2016; Türkeș & Vuță, 2022).

If we go back to the gender dimension and bear in mind that gender inequalities persist and are manifested through balancing teleworking and family/cohabitation (Rinaldo & Whalen, 2023), with women being more burdened with domestic chores or child care, for instance (e.g., Arntz et al., 2020; Atkinson, 2022; Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Otonkorpi-Lehtoranta et al., 2022), we can then ask ourselves how risky teleworking can be for women taking into account the potential impact on their careers. If ‘who is not seen is forgotten’, and if women take care of children the most and stay at home the most to balance work, family, and cohabitation arrangements, could telework have any long-term impact on women’s career progression? As Çoban (2022) concluded, telework carries the risk of detaching women from professional work, making their labor precarious, and consolidating their roles as traditional housewives, thus illustrating the gender differences because of teleworking.

The cultural conservatism of mistrust

With the results discussed so far, we have introduced the subject of flexibility, to which we will return when exploring the central organizer of the analysis. This flexible working form implies trusting employees. However, we realize that in Portugal, in the employer-employee relationship, there may be a cultural belief that begins with employee mistrust until proven otherwise, following the ‘flexibility paradox’ (Athanasiadou & Theriou, 2021). Thus, faced with an attachment to The Company’s premises, many companies might resist working away from their facilities, or, as in the case of The Company, they find a way of matching interests and allowing telework, but with restraints and to a small extent as described. It seems to us that this resistance to telework happens because many companies start from a position of distrust of the employee and invest heavily in surveillance and control mechanisms that work best in person (Dambrin, 2004; González-González et al., 2022; Karia & Asaari, 2016):

There is still an entrepreneurial perspective that, while teleworking, people will not actually be working. They’re going to be watching TV, they’re going to be watching a series, and then they’re going to work just a bit on something. (…) There’s a lot of fear, worries, like ‘no…’, that’s it. (Bruno)

Monitoring employees from a distance brings added challenges. Not only the challenges of working with hybrid teams, as previously outlined, in this thematic exploration, the challenges of “remote control” seem to be the organizational disincentives for bolder teleworking and flexibility schemes. Since it is difficult to control whether a person is working or watching TV at home, many companies may be reluctant to advance with bolder teleworking approaches (González-González et al., 2022; Raišienė et al., 2021). It should be noted that this cultural thinking also casts doubt on productivity, which, on the contrary, according to the team leaders interviewed, is not affected by remote work because, in terms of performance, as previously stated, teleworking is transparent.

And about people’s productivity, whether they’re teleworking or not, (…) if they’re motivated and they like it, it seems to me that they’ll be good professionals here or at home, (…) this isn’t a question, maybe there’s some conservatism here, a kind of collective cultural thinking. (Diana)

In this excerpt, Diana also illustrated the subtheme that is configured as workplace presentism, the act of physically showing up at the workplace while not being in the physical and/or psychological health conditions necessary for the performance of their work activity (Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Tavares, 2017):

Companies globally (…) still think that presentism is work, and it’s not. I see people here until 9 pm, and they’re not working. And I see people who leave at 5 pm to pick up the kids, and (…) they did… miracles that day! I don’t know how they did so much! We must not continue to evaluate by ‘the person is here, they’re not here, they smile, they don’t smile’, we must evaluate by the result. (Diana)

This discussion on presentism leads us to invite companies to evaluate work by goals and not by working hours (Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Tavares, 2017). And when teleworking, if employees stay at home because they’re sick, it doesn’t mean they’re not working. It is important to consider the risk of exhaustion for employees when faced with corporate values that emphasize quantity rather than quality (Tavares, 2017; Toniolo-Barrios & Pitt, 2021). And taking up Bruno’s example about watching television while working, we would even go so far as to say that watching some TV or other recreational activity during the working period could have enormous benefits for personal well-being and consequently for employees’ motivation and thus business success.

Hybrid regime, matching interests

As reported in the literature, hybrid teleworking seems to be preferred (e.g., Stoian et al., 2022) by both The Company and its employees, according to their team leaders:

And I can also tell you that all of them [employees] think that 100% teleworking would be bad. They think that the hybrid system is the best because they also like to be with their colleagues, they like to come into the office, they like to socialize, they also think it’s good to get out of home (…), and they think that this mixed dynamic, the hybrid, ends up being a suitable system. (Catarina)

Catarina’s description shows that workers also find advantages in working in The Company’s facilities due to the more significant consolidation and promotion of interpersonal relationships (Stoian et al., 2022), thus mitigating the negative impacts of teleworking on an individual level (Hamouche, 2020; Toniolo-Barrios & Pitt, 2021). It is also clear to The Company that working permanently remotely has some disadvantages:

The hybrid system (…) It’s the preferred one, it works best… even from a company perspective (…) although you can maintain some teamwork dynamics remotely, as we had, for example, during the pandemic period, but you realize that you lose something in terms of relationships, in terms of teamwork, okay? (Bruno)

These disadvantages are expressed by The Company’s management in the form of concerns when people are absent from the workplace. In Helena’s team, for example, where they’ve adopted one teleworking day a week, she explains:

If you’re teleworking on Tuesday, but on Monday and Wednesday you’re working in the field, and then you come here on Thursday and Friday. When you go into the overview… You see a lot of empty chairs. And then: ‘Hey, where are they? What’s up? (…) Where is he/she?’ (…) and they [the administration] start to get nervous, so to speak… (Helena)

In Helena’s excerpt, the administration’s concerns about staff absences are clear, reinforcing The Company’s concerns and resistance to teleworking. However, it also brings about The Company’s specificities.

In addition to the variability among teams, some teams may opt for teleworking one day a week, and others two; there are exceptions under the law. People with children up to the age of one can, in The Company, telework in full without penalizing their income. The Company also contemplates “exceptional situations, even under the law, which allow for longer periods of teleworking (…) situations of children with… with disabilities, for instance” (João). There are also some very exceptional cases due to geographical distance that have been authorized for permanent teleworking.

However, there is another exception to assumed privilege: the Information Technology (IT) team. The IT privilege refers to people in the IT team who can telework exclusively or almost exclusively without loss of income due to the competitiveness of this area. Considering the difficulty in hiring and retaining IT staff, teleworking, in this case, is a tool that makes The Company appealing (Morris et al., 2023; Mutiganda et al., 2022), as Bruno explains, referring to IT: “I need to hire someone with a certain profile, otherwise I can’t, okay? So, I use total teleworking (…) And since there’s a shortage of resources in technology, (…) it ends up being trivial”.

Furthermore, in this company, people in management positions are not encouraged to telework, but they do have the possibility to make it more flexible. When necessary, they can work from home to meet any personal, family, or other balancing needs. Leonardo explains this flexibility: “Teleworking at management level (…) it doesn’t make any sense (…) it’s not productive, it’s not… it doesn’t account for what’s best for the organization (…). That’s not to say there isn’t flexibility, and there is…”.

Filipa explains that for most employees, it is possible to formally add an addendum to the contract and implement a hybrid teleworking system, as previously mentioned; however,

At The Company, managers are not supposed to telework. There is, albeit, a flexible regime. If I want to, for example, stay at home today, obviously, nobody will tell me no, and I would stay, but I don’t have that telework formalism like they [other employees] have in their employment contract. (Filipa)

The description of this hybrid model announces the central organizer of this analysis. The Company presents an approach close to flexibility (Morris et al., 2023; Stoian et al., 2022; Sullivan & Lewis, 2001), not only for employees who can make their working hours or place of work more flexible, occasionally, exceptionally, if duly justified, and to avoid missing work and allow the work to continue, but also for team managers who take on the self-management and flexibility of their work. However, this flexibility is contained as follows.

‘It’s all about flexibility’

‘It’s all about flexibility’ is the central organizer of the analysis. The analytical explorations take us to Flexwork: a way of working focusing on flexible practices that suit the employee’s needs (De Menezes & Kelliher, 2011). Flexwork allows employees to adjust their schedule, working hours, workplace, way of working, or vacations (e.g., De Menezes & Kelliher, 2011; Richardson, 2010). Flexwork enables employees to have flexible start/finish times or work from home using information and communication technologies. Through this flexible practice, employees can adjust their work to daily needs.

For instance, flexwork means choosing which days someone wants to work longer and which days less, where to work, and the possibility of working on projects or goals and not for days or hours. Considering the objective-based work format would solve the challenge presented by The Company when discussing the cultural conservatism of mistrust and the difficulty of monitoring teleworkers. Working towards goals would mean checking work targets, not the employee’s posture, the time spent at the computer, or the number of breaks, for instance, with an impact on presentism.

Participants and the majority of teleworkers in The Company, through the voice of their managers, recognize the advantages of flexwork. These advantages focus mainly on gains in ‘work-life-family balance’, well-being, job satisfaction, and productivity (e.g., Atkinson, 2022; Martin & MacDonnell, 2012; Xiao et al., 2021).

Despite the resistances and challenges of flexworking, such as reduced sociability, greater individualization, loss of cohesion between teams, and even the control of teams challenge (e.g., Atkinson, 2022; Magalhães et al., 2020; Niebuhr et al., 2022; Wharton, 2012), we can say that The Company gets closer to this model when bringing flexibility to work management, especially for managers and, to a certain extent, for the employees.

One of these days, I said to my boss (…) ‘Look engineer, tomorrow I need to stay home because the gas guy is coming’ (…), and then I stayed home teleworking. For example, yesterday I went to a meeting at the City Council… I left there, it was almost 5.30 pm, and it no longer paid off to return to The Company. Therefore, I went straight home. I made a few phone calls along the way, took care of other things, and then went to my pilates class calmly and serenely… Today I’m here at 8.30 in the morning, that’s it… That’s all about flexibility! (Helena)

More than having an addendum to the contract indicating the days Helena will be working from home, she highlights the possibility of flexwork, of making things more flexible according to her needs. André also demonstrates these dynamics and the advantages for both The Company and the employees:

Imagine that on a Friday, a person suddenly has an appointment at the health center near their home. On that day, they go to the health center, and then they stay at home teleworking to be more practical and quicker (…), so we facilitate these situations. We also use teleworking a lot to manage these situations. It’s good for him/her [the employee], it’s good for us [The Company]. (André)

From André's excerpt, we understand The Company is ensuring the work continues uninterrupted, avoiding an employee’s absence from work, but it is also showing some concerns with employees’ well-being and work-life balance (Kirchmeyer, 2000; Wharton, 2012), thus coming closer to the flexwork model we are proposing:

create our own, the best possible conditions that don’t impact on the operation, but allows our people to come, to have life quality, to manage their personal issues in the best way, (…) with a policy of flexible working hours, (…) of changing shifts… that are spread across all operational areas. Therefore, I think, from this point of view, we are a company that is concerned with…, of course, within the limits, and the limits are always the quality of the operation, (…) being able to balance the personal and professional lives of our employees. (João)

This study shows us that teleworking is here to stay, in a fluid way, adapting to the needs of employees in the form of flexwork, although with restraint and caution, since flexwork also has its two faces: if on the one hand, it can be beneficial, on the other it can also bring challenges and harmful implications with many processes of adaptation and re-regulation (Ajzen & Taskin, 2021). In addition, we realize that the implications of telework can stand out on an individual/personal level (Ajzen & Taskin, 2021), while in The Company, a positive impact on organizational performance and a negative impact on organizational behavior stand out (Caraiani et al., 2023).

Conclusion

This study examined teleworking practices in a large Portuguese company. The participants group consisted exclusively of managers from various departments, including HR, IT, and operations. These participants ranged from team leaders to senior executives, providing a multi-level managerial perspective on telework implementation. Starting from a social constructionist and questioning gender/equality perspective (e.g., Acker, 2006; Burr, 1995; Walby, 2020), we had access to a collectively interconnected thematic network regarding The Company’s approach to telework, which is not to inhibit nor to encourage, exposing the concerns and resistances of a company that has come to realize that cannot remain trapped in the traditional preference of working exclusively in their facilities (Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Mutiganda et al., 2022; Tavares, 2017). These concerns and resistance denote cultural conservatism about how the employees’ performance should be monitored remotely, with employers’ mistrust of their employees being one of the biggest challenges. However, as confirmed here, from the managerial perspective, in terms of productivity, telework is transparent. However, it’s important to note that this perception may differ at the subordinate level or across different departments. Therefore, we invite companies to counter the ‘flexibility paradox’, where employees require some flexibility and autonomy in spatial and temporal working terms, but the employer simultaneously establishes rigid procedures to ensure work efficiency, inhibiting flexibility (Athanasiadou & Theriou, 2021).

Proof of the increasing interest in teleworking in The Company is the fact that it has been considered a solution to respond to the competitiveness of the human resources recruitment market (Morris et al., 2023; Mutiganda et al., 2022; Raišienė et al., 2021), as well as a way of matching the interests of employees, despite the employer’s less favorable opinion. Nevertheless, teleworking is part of the ‘new normal’ (Ameen et al., 2023; Caraiani et al., 2023; Raišienė et al., 2021). Employees are expressing their preference for maintaining a hybrid remote working regime that has proven to be viable in times of the COVID-19 pandemic (Ameen et al., 2023).

Reasons and consequences include balancing cohabitation or family life (Beckel & Fisher, 2022; Sullivan & Lewis, 2001; Tavares, 2017), realizing that telework can be both advantageous and harmful at an individual level, displaying its two faces, with no impact on The Company performance (e.g. Atkinson, 2022; Lange & Kayser, 2022; Magalhães et al., 2020; Majumdar et al., 2020; Toniolo-Barrios & Pitt, 2021) and adding challenges for remote team management (Dambrin, 2004; González-González et al., 2022; Greer & Payne, 2014; Karia & Asaari, 2016; Türkeș & Vuță, 2022) that make managers forget who’s working from home.

It is important to highlight the resulting gender differences affecting women, overlooked by their managers for a more attractive project or career progression (Çoban, 2022; Crawford, 2022). Gender inequalities might be accentuated with teleworking (Arntz et al., 2020; Beckel & Fisher, 2022), replicating double standards in domestic and caring tasks (e.g., Atkinson, 2022; Costoya et al., 2022; Otonkorpi-Lehtoranta et al., 2022). This study raises concerns about the impact of teleworking on women in a gender-unequal society (Çoban, 2022).

The hybrid regime makes it possible to balance interests, mitigating some negative impacts on a personal level, and with a set of specificities that characterize hybrid teleworking at The Company with hints of fluidity and flexibility (Stoian et al., 2022). Therefore, this study invites us to consider this new reality: teleworking is here to stay, and its hints of fluidity come through in a constant optimization format that keeps pace with work and people dynamics change. This study leads us forward towards flexwork (e.g., De Menezes & Kelliher, 2011; Richardson, 2010).

The whole teleworking experience is inherently subjective, a consequence of human diversity. Every human being is different and unique; they work and focus in a variety of ways and need to work-life balance in different ways (Kirchmeyer, 2000; Marks & MacDermid, 1996; Wharton, 2012). Thus, the teleworking experience is diverse and dependent on multiple variables. Flexibility meets this diversity as it adapts to each employee’s individual needs as well as The Company’s needs. To reinforce this flexibility, telework must be optional because it can fit some but not others. Therefore, we propose a flexible, tailored-to-each-person, formally designed type of work with the necessary structural and organizational framework but permeable barriers.

It is crucial to acknowledge that the composition of our participant group, composed exclusively of managers, shapes the analytical lens and implications of this case study. Managers’ perspectives offer unique insights into the implementation and regulation of telework policies (Yukl, 2013), and this study highlights how varying managerial roles and departmental demands influence teleworking experiences (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006).

We consider this an innovative work that focuses on teleworking in Portugal, in a post-pandemic period, and from an organizational perspective through a case study. We have achieved significant results about telework marked by gender that can become valuable information for both employers and policymakers.

However, the study also has some limitations. We recognize the possible social desirability in the participants’ answers. We also recognize that they have given a voice to the company’s employees, but in an indirect way. The translation of the participants’ narratives, given the difficulty of capturing the exact characteristic expressions of the language, could be constraining. Nonetheless, this work has also revealed the importance of preparing and training companies and managers to lead teams in hybrid and flexible teleworking settings. The mental health of teleworkers is also a major issue worth focusing on. Regarding gender inequality, attention should be paid to women to counteract the asymmetries that are still tougher on them.

Future research directions could explore several key areas. Firstly, longitudinal studies examining the long-term effects of telework on organizational culture, employee well-being, and productivity would provide valuable insights as telework becomes more established. Secondly, investigating the impact of different telework policies and practices on employee satisfaction and future teleworking preferences could help organizations optimize their approaches. Thirdly, research into the relationship between telework and work intensity, particularly in the context of boundary conditions and multidimensional analysis, would enhance our understanding of telework’s effects on work-life balance. Finally, studies focusing on the challenges and opportunities of hybrid work arrangements, which combine telework with on-site work, could inform future workplace policies and practices.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available. However, data can be available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of FPCEUP.

References

Acker J (2006) Inequality regimes: gender, class, and race in organizations. Gend Soc 20(4):441–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243206289499

Ajzen M, Taskin L (2021) The re-regulation of working communities and relationships in the context of flexwork: a spacing identity approach. Inf Organ 31(4):100364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2021.100364

Ameen N, Papagiannidis S, Hosany ARS, Gentina E (2023) It’s part of the “new normal”: does a global pandemic change employees’ perception of teleworking? J Bus Res 164:113956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113956

Arntz M, Yahmed SB, Berlingieri F (2020) Working from home and COVID-19: the chances and risks for gender gaps. Intereconomics 55(6):381–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-020-0938-5

Athanasiadou C, Theriou G (2021) Telework: systematic literature review and future research agenda. Heliyon 7(10):e08165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08165

Atkinson CL (2022) A review of telework in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned for work-life balance? COVID 2(10):1405–1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/covid2100101

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2007) The job demands‐resources model: state of the art. J Manag Psychol 22(3):309–328

Bañón AM, Sánchez RL (2008). El estudio de caso: una estrategia para la investigación en dirección de empresas. Cuadernos de economía y dirección de la empresa 35:113–124

Beckel JLO, Fisher GG (2022) Telework and worker health and well-being: a review and recommendations for research and practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(7):3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19073879

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol 18(3):328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Burr V (1995) An introduction to social constructionism. Routledge

Byron K (2005) A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. J Vocat Behav 67(2):169–198

Caraiani C, Lungu CI, Dascalu C, Stoian C-A (2023) The impact of telework on organisational performance, behaviour, and culture: Evidence from business services industry based on employees’ perceptions. Econ Res-Ekonomska Istraživanja 36(2):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2142815

Çoban S (2022) Gender and telework: work and family experiences of teleworking professional, middle-class, married women with children during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Gend Work Organ 29(1):241–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12684

Costoya V, Echeverría L, Edo M, Rocha A, Thailinger A (2022) Gender gaps within couples: evidence of time reallocations during COVID-19 in Argentina. J Fam Econ Issues 43:213–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-021-09770-8

Crawford J (2022) Working from home, telework, and psychological well-being: a systematic review. Sustainability 14(19):11874. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141911874

Dambrin C (2004) How does telework influence the manager-employee relationship? Int J Hum Resour Dev Manag 4(4):358–374. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHRDM.2004.005044

De Menezes LM, Kelliher C (2011) Flexible working and performance: a systematic review of the evidence for a business case. Int J Manag Rev 13(4):452–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00301.x

Delanoeije J, Verbruggen M (2020) Between-person and within-person effects of telework: a quasi-field experiment. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 29(6):795–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2020.1774557

Ding X, Ploeg J, Williams A (2024) Telework and work-life balance among older adults: a scoping review. J Occup Health 66(1):e12461

Eby LT, Casper WJ, Lockwood A, Bordeaux C, Brinley A (2005) Work and family research in IO/OB: content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002). J Vocat Behav 66(1):124–197

Emslie C, Hunt K (2009) Live to work’ or ‘work to live’? A qualitative study of gender and work–life balance among men and women in mid-life. Gend Work Organ 16(1):151–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00434.x

Fan W, Moen P (2022) Working more, less or the same during COVID-19? A mixed-method, intersectional analysis of remote workers. Work Occup 49(2):143–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/07308884211047208

Fan W, Moen P (2023) The future(s) of work? Disparities around changing job conditions when remote/hybrid or returning to working at work. Work Occup. https://doi.org/10.1177/07308884231203668

Gareis KC, Barnett RC, Ertel KA, Berkman LF (2009) Work–family enrichment and physical health: a preliminary study of women in the healthcare industry. Work Stress 23(3):215–228

Gerring J (2004) What is a case study and what is it good for? Am Polit Sci Rev 98(2):341–354

González-González I, Martínez-Ruiz MP, Clemente-Almendros JA (2022) Does employee management influence the continued use of telework after the COVID-19 pandemic? Small Bus Int Rev 6(2):e537. https://doi.org/10.26784/sbir.v6i2.537

Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ (1985) Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manag Rev 10:76–88

Greer TW, Payne SC (2014) Overcoming telework challenges: outcomes of successful telework strategies. Psychol Manag J 17(2):87–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/mgr0000014

Hamouche S (2020) COVID-19 and employees’ mental health: stressors, moderators, and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Res 2(15):1–15. https://doi.org/10.35241/emeraldopenres.13550.1

Karia N, Asaari MHAH (2016) Innovation capability: the impact of teleworking on sustainable competitive advantage. Int J Technol Policy Manag 16(2):181–194. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTPM.2016.076318

Kirchmeyer C (2000) Work-life initiatives: Greed or benevolence regarding workers’ time?. In: C.L. Cooper CL, Rousseau DM (eds.). Trends in organizational behavior. vol. 7. Wiley, Chichester. pp. 79–93

Laat K (2023) Living to work (from home): Overwork, remote work, and gendered dual devotion to work and family. Work Occup 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/07308884231207772

Lange M, Kayser I (2022) The role of self-efficacy, work-related autonomy and work-family conflict on employee’s stress level during home-based remote work in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(9):4955. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19094955

Magalhães PC, Gouveia R, Costa-Lopes R, Silva PA (2020) O Impacto Social da Pandemia. Estudo ICS/ISCTE Covid-19. Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa e Instituto Universitário de Lisboa. http://hdl.handle.net/10451/42911

Majumdar P, Biswas A, Sahu S (2020) COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: cause of sleep disruption, depression, somatic pain, and increased screen exposure of office workers and students of India. Chronobiol Int 37(8):1191–1200. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2020.1786107

Martin BH, MacDonnell R (2012) Is telework effective for organizations? A meta-analysis of empirical researchon perceptions of telework and organizational outcomes. Manage Res Rev 35(7):602–616. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409171211238820

Marks SR, MacDermid SM (1996) Multiple roles and the self: a theory of role balance. J Marriage Fam 58(2):417–432

Mesmer-Magnus JR, Viswesvaran C (2005) Convergence between measures of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: a meta-analytic examination. J Vocat Behav 67(2):215–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.05.004

Moen P, Roehling P (2005) The career mystique: dilemmas of work and identity. Sociol Spectr 25(5):559–576

Morgeson FP, Humphrey SE (2006) The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J Appl Psychol 91(6):1321–1339

Morris SN, Burak E, Hammer LB (2023) Telework and mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol 28(4):365

Mutiganda JC, Wiitavaara B, Heiden M, Svensson S, Fagerström A, Bergström G, Aboagye E (2022) A systematic review of the research on telework and organizational economic performance indicators. Front Psychol 13:1035310. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1035310

Niebuhr F, Ropeter J, Anders L (2022) Healthy and happy working from home? Effects of working from home on employee health and job satisfaction. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(3):1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031122

Nijp HH, Beckers DG, van de Voorde K, Geurts SA, Kompier MA (2016) Effects of electronic remote working on employee job demands and resources: a systematic review. J Occup Organ Psychol 89(4):612–634

Otonkorpi-Lehtoranta O, Nätti J, Kinnunen U, Vänni K (2022) Gendered experiences of remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gend Work Organ 29(4):1193–1210

Raišienė AG, Rapuano V, Dőry T, Varkulevičiūtė K (2021) Does telework work? Gauging challenges of telecommuting to adapt to a “New Normal”. Hum Technol 17(2):126–144. https://doi.org/10.14254/1795-6889.2021.17-2.3

Richardson J (2010) Managing flexworkers: holding on and letting go. J Manag Dev 29(2):137–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011019279

Rinaldo S, Whalen A (2023) Digital collaboration in hybrid work environments: Challenges and strategies. J Organ Behav 44(2):123–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2567

Santos AMBTV, Rita LPS, Levino NA (2023) Teletrabalho em tempos de pandemia de COVID-19: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura internacional. Rev Interdiscip Científica Aplicada 17(1):62–81. https://portaldeperiodicos.animaeducacao.com.br/index.php/rica/article/view/18142

Stoian C-A, Caraiani C, Anica-Popa IF, Dascălu C, Lungu CI (2022) Telework systematic model design for the future of work. Sustainability 14(12):7146. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127146

Sullivan C, Lewis S (2001) Home-based telework, gender, and the synchronization of work and family: Perspectives of teleworkers and their co-residents. Gend Work Organ 8(2):123–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00125

Tavares AI (2017) Telework and health effects review. Int J Healthc 3(2):30–36. https://doi.org/10.5430/IJH.V3N2P30

Toniolo-Barrios M, Pitt L (2021) Teleworking and well-being: exploring the dark side. Manag Res J Iberoam Acad Manag 19(2):148–163

Türkeș MC, Vuță DR (2022) Telework: before and after COVID-19. Encyclopedia 2(3):1370–1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia2030092

Van Rijnsoever FJ (2017) I can’t get no saturation: a simulation and guidelines for sample sizes in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 12(7):e0181689

Walby S (2020) Varieties of gender regimes. Soc Polit Int Stud Gend State Soc 27(3):414–431. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxaa018

Wenham C, Smith J, Morgan R (2020) Gender and COVID-19 Working Group. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet 395(10227):846–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2

Wharton AS (2012) Work and family in the 21st century: four research domains. Sociol Compass 6(3):219–235

Xiao Y, Becerik-Gerber B, Lucas G, Roll SC (2021) Impacts of working from home during COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of office workstation users. J Occup Environ Med 63(3):181–190. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000002097

Yukl G (2013) Leadership in organizations (8th edn.). Pearson

Zołnierczyk-Zreda D, Pieńkowski P, Sobocka M, Krzyżak A (2012) Mental health of teleworkers—a systematic review. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 25(5-6):469–481

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. The contributions to this research were allocated as follows: Conceptualization was carried out by RG, SIM, CP, ALP, and CN. Formal analysis was conducted by RG, SIM, LR, and CN. The investigation was led by RG, LR, and CN. Methodology was developed by RG, SIM, and ALP. Validation of results was performed by RG, ALP, and LR. The original draft of the manuscript was written collaboratively by RG, SIM, CP, ALP, ARP, LR, and CN. The review and editing process was conducted by RG and SIM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical clearance from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences of the University of Porto, in Portugal (Approval Number: 2023/07-06c). The ethics application was submitted on July 14, 2023, and conditional approval was granted on July 28, 2023, prior to the beginning of data collection. This conditional approval allowed the research team to proceed with data collection, while being subject to minor revisions. The Ethics Committee accompanied the entire process and subsequently issued the final approval on November 8, 2023. All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

In adherence to the Helsinki Declaration, all participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study. They were given detailed information about the purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits involved. Consent was considered given when participants chose to proceed with the recorded interview after reading and signing the consent form. The research team obtained consent on the day of each participant’s interview. To ensure confidentiality, specific dates will not be disclosed, but all consents were obtained between July and September 2023, during which the interviews took place. Participants were fully informed that their participation was entirely voluntary and that they could terminate the interview at any stage without suffering any negative consequences.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grave, R., Magalhães, S.I., Pontedeira, C. et al. ‘It’s all about flexibility!’ A case study on telework in a Portuguese company after the COVID-19 pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 730 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05013-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05013-5