Abstract

Do national economic, social, and institutional conditions shape country-level entrepreneurship? While previous studies have explored this question, their findings remain inconsistent. Grounded in the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Transaction Cost Economics (TCE), this study examines the influence of 10 macro factors on entrepreneurship. Using panel data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor and the World Bank (2003–2019), covering 605 observations across 70 countries, the analysis employs a dynamic system GMM model. The results indicate that only four macro factors significantly affect country-level entrepreneurship, including: Economic Growth, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Economic Openness and Final Consumption Expenditure. This study contributes to entrepreneurship research by integrating RBV and TCE perspectives, demonstrating that economic resources strongly shape entrepreneurial activity at the macro level, while transaction costs associated with institutional barriers should be carefully considered by entrepreneurs in their decision-making. Additionally, the findings suggest policy implications for enhancing resource availability through promoting GDP growth, attracting FDI, selectively engaging in international trade, and implementing consumption-driven policies that benefit entrepreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amidst the backdrop of global integration and intensifying economic competition among nations, the field of entrepreneurship has gained considerable prominence. This area, intrinsically tied to innovation and enterprise formation, has attracted extensive scholarly attention in recent decades. A substantial body of literature focusing on individual-level entrepreneurship exists, as highlighted by scholars such as Hamdan et al. (2022) and Pfeifer et al. (2021) in their comprehensive literature reviews. Nonetheless, there is a growing scholarly and policy interest in exploring and delineating the macro socio-economic determinants of country-level entrepreneurship (Thai and Turkina, 2014; Castaño et al., 2015; Amorós et al., 2016). This exploration aims to elucidate the disparities in overall entrepreneurial activity among different nations, as noted by Urbano et al. (2019). While individual-level factors, including entrepreneur characteristics and resource availability, contribute to these disparities, country-level entrepreneurship encompasses national-specific conditions that require a macro-level analysis for comprehensive understanding.

In particular, examining the variations in national entrepreneurial activity is crucial for scholars and policymakers. This analysis provides deeper insights into the economic and social progression of each country, as Wennekers (2006) observed. Such variations are indicative of the overarching business environmental factors within each nation, offering a lens to assess their influence on entrepreneurial activities. Furthermore, this comparative study of national entrepreneurial rates is instrumental in identifying underlying causes and drawing valuable lessons from the successes and failures of different countries in fostering entrepreneurship. These insights are foundational for governments in formulating policies and strategies that are conducive to nurturing a business climate that not only accelerates economic growth but also cultivates opportunities for aspiring entrepreneurs.

In examining entrepreneurship from a national perspective, researchers widely acknowledge the critical role of country-level entrepreneurship. This concept is defined by the cumulative rate of new business formations within a nation over a specified period, typically measured annually (Wennekers, 2006). It represents the aggregate level of entrepreneurial activity, encompassing the rate of new business creation, the prevalence of early-stage entrepreneurial ventures, and the sustainability of enterprises. Furthermore, it reflects the broader national environment that either fosters or constrains entrepreneurship (Bosma and Schutjens, 2011; Ndofirepi and Steyn, 2023).

Country-level entrepreneurship serves as a catalyst for economic growth, innovation, enhancing competitiveness at both firm and national levels, job creation, and poverty alleviation, particularly in emerging and developing economies, as evidenced by Bruton et al. (2021) and Hamdan et al. (2022). New enterprises are pivotal as agents of structural transformation and as catalysts for economic expansion, notwithstanding the challenges they encounter, as noted by Naudé (2010).

Although the contribution of entrepreneurship to a nation’s socio-economic development is well-established in scholarly discourse, the exploration of macro-level factors and their influence on national entrepreneurship is relatively nascent. Urbano et al. (2019) in their literature review, observed that most empirical research has applied institutional theory, concentrating on the institutional precursors to national entrepreneurship. Both formal institutions (such as government-enacted policies, laws, and regulations) and informal institutions (including societal beliefs, norms, cultural, and cognitive elements that shape individual behavior and decisions) have been identified as significantly affecting national entrepreneurship (Kalisz et al., 2021; Pfeifer et al., 2021; Solomon et al., 2021). While the institutional approach to studying national entrepreneurship is valuable, highlighting the role of governmental entities and public administration, it tends to obscure other socio-economic factors that also contribute to a country’s business environment.

Previous research has emphasized the critical roles of cultural attributes, economic conditions, technological advancements, and educational levels in shaping entrepreneurship (Kalisz et al., 2021; Castaño et al., 2015). Although there is broad agreement among scholars in the field of entrepreneurship on the categories of factors influencing entrepreneurial activity, empirical studies have yielded divergent results concerning the relative significance of each factor and, in some cases, contradictory indications of their impact. For instance, certain research (e.g., Nyström, 2008) has evidenced a positive correlation between the strength of institutions, higher levels of economic development, and technological innovation with the rates of national entrepreneurship. In contrast, other studies have highlighted a negative relationship (e.g., Naudé, 2010) or failed to find any significant linkage (Van Stel et al., 2007) between these same variables and entrepreneurship. Furthermore, regarding the influence of factors such as economic growth and unemployment, Sharma et al. (2023) emphasize the role of per capita GDP in fostering entrepreneurship by increasing savings and investment capacity. However, Autio et al. (2014) caution that in developed economies, rapid GDP expansion may lead to market saturation, thereby limiting entrepreneurial opportunities. Similarly, Thurik et al. (2008) argue that higher unemployment may encourage necessity-driven entrepreneurship, whereas other studies suggest that persistent unemployment can hinder entrepreneurial activity by reducing overall economic stability and consumer demand (Audretsch et al., 2001). These inconsistencies underscore the need for a more nuanced investigation into how different macro-level factors interact to shape entrepreneurial activity.

Although prior research has explored country-level entrepreneurship, significant gaps remain in understanding temporal variations across nations and the interplay of institutional, economic, and social determinants. Most studies, such as those by Bosma and Schutjens (2011), have been regionally constrained, focusing predominantly on Europe. Similarly, Ndofirepi and Steyn (2023) relied exclusively on Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) data, limiting the scope of generalizability. This study extends the literature by employing a panel data approach to analyze long-term trends in national entrepreneurship, integrating datasets from both GEM and the World Bank.

Macro-level determinants have been categorized differently in the literature. Thai and Turkina (2014) classify these factors into four groups: demand-side, supply-side, cultural influences, and governance quality. In contrast, Castaño et al. (2015) propose a tripartite framework consisting of social, economic, and cultural factors. However, prior research has primarily examined the combined effects of these factors rather than evaluating the specific contributions of individual indicators, such as economic openness, expenditure on education, or the unemployment rate, to national entrepreneurship.

This study contributes to the field by integrating two influential theoretical perspectives: the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Transaction Cost Economics (TCE). Prior research has explored the application of these frameworks in entrepreneurship studies (Alvarez and Busenitz, 2001; Kellermanns et al., 2016; Foss and Foss, 2006). RBV highlights the significance of national resources, including human capital, technological infrastructure, and financial systems, whereas TCE emphasizes institutional efficiency, transaction costs, and economic integration as key drivers of entrepreneurial activity.

Furthermore, to address existing research gaps, this study empirically examines the distinct contributions of individual indicators (e.g., economic openness, expenditure on education, and the unemployment rate) within economic, social, and institutional factors to national entrepreneurship rates. Unlike previous research that primarily assessed their combined impact (Thai and Turkina, 2014; Castaño et al., 2015), our approach isolates the specific influence of each indicator within a structured macro-level framework.

By adopting this multidimensional approach, we aim to provide a more comprehensive socio-economic perspective on cross-country variations in entrepreneurship, moving beyond a state-centric governance model. This analysis will generate more tailored and effective policy recommendations for fostering national entrepreneurship. Given the current global landscape -marked by intensifying competition, rapid technological advancements, and post-pandemic economic recovery - understanding national entrepreneurship has become increasingly crucial for shaping policies that support sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: “Theoretical framework and hypothesis developments” reviews the existing literature on macro-level entrepreneurship, the study’s theoretical foundations, and hypothesis development. “Research Methodology” outlines the research methodology, including data collection, variable measurement, and panel data analysis techniques. “Research Findings and Discussions” presents and discusses the empirical findings, while “Conclusion and Policy Implications” concludes with key findings, theoretical and policy implications, limitations, and future research directions.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis developments

Theoretical background

Concepts of country-level entrepreneurship

The concept of entrepreneurship is multifaceted, with diverse definitions provided by various scholars. At the individual and firm levels, entrepreneurship is conceptualized as the process of initiating a business venture. This process encompasses the establishment, organization, and administration of a nascent enterprise, often a small business in its early stages, as delineated by Katila et al. (2012). Entrepreneurs, the individuals who embark on these ventures, are not only business proprietors but also key agents of innovation and change, embodying roles beyond mere management to include production and innovation, as Schumpeter (1934) elucidated. Furthermore, entrepreneurship is regarded as a decision-making process involving a choice between self-employment and wage employment. This perspective posits that individuals opt for entrepreneurial activities when the combined non-monetary and monetary rewards of self-employment surpass those of traditional employment, as argued by Murphy et al. (1991).

On a broader scale, country-level entrepreneurship is characterized by the cumulative rate of new business formations over a specified period, typically annually, within a given nation, as described by Wennekers (2006). This macro-level conceptualization of entrepreneurship is intrinsically linked to and contingent upon the entrepreneurial capabilities at the individual and firm levels. These capabilities include expertise in areas such as knowledge, economics, science and technology, market dynamics, and proficiency in devising and administering economic strategies at a macro scale.

From these various conceptions of entrepreneurship at different analytical levels, it becomes apparent that research focusing on the individual level concentrates on the attributes and contextual factors surrounding entrepreneurs. Consequently, this necessitates a consideration of country-level entrepreneurship as a research focus, adopting economic and management perspectives to elucidate the influence and significance of macro-level factors. This approach is pivotal for developing relevant policy recommendations for governments. Therefore, this research constructs its theoretical framework based on established theories in management science, specifically the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Transaction Cost Economics (TCE).

The country-level entrepreneurship in Resource-Based View

In Resource-Based View (RBV), the genesis of a firm’s competitive advantage is identified as stemming from its unique resources. Success in business is contingent upon the acquisition and effective combination of resources in a manner superior to competitors (Barney, 1991). Within this framework, Alvarez and Busenitz (2001) explored individual-level entrepreneurship, asserting that entrepreneurs possess distinctive resources, enabling them to identify new opportunities and assemble resources for ventures, thereby generating outputs that surpass market standards.

Extending the RBV to a national context, this study proposes that the collective entrepreneurial rate among countries hinges on their macro-level factors, which serve as vital inputs shaped by entrepreneurial vision and intuition. For the advancement of national entrepreneurship, a conducive and stable business environment is essential. This encompasses a transparent and equitable legal framework, political stability for investment predictability, advanced infrastructure, and education and training systems that equip entrepreneurs with necessary skills. Additionally, access to capital and resources is crucial for fostering national entrepreneurship. In essence, favorable macro conditions are imperative for the robust development and significant contribution of country-level entrepreneurship to a country’s economic and social progress.

Country-level entrepreneurship in transaction cost economics

The concept of transaction costs, introduced by Coase (1937) and elaborated in the Transaction Cost Economics (TCE) theory by Williamson (1981), posits that an economic entity is efficient when it minimizes the operational costs of the economic system, referred to as transaction costs. Dahlman (1979) categorizes these costs into three groups: search and information costs, bargaining and decision costs, and policing and enforcement costs. In the context of individual-level entrepreneurship, Michael (2007) and Stieglitz and Foss (2009) argue that an entrepreneur’s decision-making is influenced by their capacity to manage entrepreneurial costs. High entrepreneurial costs pose significant challenges for potential entrepreneurs, especially those with limited resources. Entrepreneurs, therefore, must judiciously assess these costs against prospective profits and strategize to minimize unnecessary expenditures while maximizing resource utilization.

Expanding TCE to encompass national entrepreneurship, this study posits that transaction costs in this context include the expenses from idea generation to new venture establishment (ex-ante costs) and the operational costs of a newly formed business (ex-post costs). These costs are pivotal in influencing entrepreneurial decision-making. The study suggests that facilitating entrepreneurial transactions can boost entrepreneurial motivation. Moreover, the interplay between transaction costs and national entrepreneurship is observable in the economic market equilibrium. Disturbances in this equilibrium necessitate adjustments in the price and quantity of entrepreneurial activities, leading to market entry by new businesses aiming to restore balance and pursue profitability.

The choice of determinant of macro-level entrepreneurship

The integration of the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Transaction Cost Economics (TCE) provides a robust theoretical foundation for selecting the key variables in this study. RBV emphasizes the strategic importance of national resources, such as human capital, technological infrastructure, and financial systems, in fostering entrepreneurial activity (Barney, 1991). In contrast, TCE focuses on the role of institutional efficiency, transaction costs, and economic integration in shaping business environments and reducing barriers to market entry (Williamson, 1981). By combining these perspectives, the study aims to offer a more comprehensive understanding of how macro-level determinants influence national entrepreneurship.

Economic factors, including GDP growth, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Economic Openness, and the Consumer Price Index (CPI), are crucial from both theoretical standpoints. From an RBV perspective, economic growth and FDI represent essential resources that enhance entrepreneurial opportunities by increasing capital availability, technological spillovers, and market expansion (Acs et al., 2013). TCE complements this view by highlighting how economic openness reduces transaction costs and fosters competition, making market entry more feasible for entrepreneurs. Additionally, CPI serves as an indicator of price stability, which can influence investment decisions and business sustainability (Baumol, 1990).

Social factors, such as education expenditures and unemployment rates, align closely with RBV’s emphasis on resource accumulation. Human capital, as reflected in education investment, is a key resource that enhances entrepreneurial capabilities, innovation, and productivity. Unemployment, on the other hand, may act as both a push and pull factor for entrepreneurship, as individuals seek alternative income sources in response to labor market conditions. TCE further informs these relationships by suggesting that social structures influence transaction costs, particularly in labor markets, where education levels and unemployment rates affect workforce efficiency and business viability (Djankov et al., 2002).

Institutional factors - including the cost of business start-up procedures, the number of procedures required to register a business, and the time needed to start a business - are central to TCE. These variables capture the regulatory and administrative barriers that affect entrepreneurs’ ability to enter markets efficiently. High transaction costs, stemming from excessive regulatory burdens, discourage entrepreneurship by increasing operational risks and initial capital requirements. Meanwhile, RBV complements this perspective by emphasizing that an efficient institutional framework can be viewed as a national resource that fosters innovation and economic dynamism (Audretsch and Keilbach, 2004).

The selection of the above variables is also based on a review of previous studies on important determinants of national entrepreneurship, as shown in Table 1 below.

By integrating RBV and TCE, this study systematically examines the distinct contributions of economic, social, and institutional variables to national entrepreneurship. Unlike prior research that primarily assessed their aggregate effects, this approach disentangles the specific influence of each indicator within a structured macro-level framework, providing a more nuanced understanding of cross-country variations in entrepreneurial activity.

Hypothesis developments on the relationship between macro factors and country-level entrepreneurship

Impact of economic factors on country-level entrepreneurship

From the perspective of the Resource-Based View, economic growth and foreign direct investment (FDI) play a crucial role in fostering entrepreneurial opportunities by enhancing access to capital, facilitating technology transfer, and supporting market expansion (Acs et al., 2013). Entrepreneurial initiatives often commence from a foundation of resources analyzed through macro-level logical assessments. Entrepreneurs typically begin by scrutinizing controllable macroeconomic conditions, which then inform the development of their entrepreneurial strategy, vision, and mission, ultimately laying the groundwork for future business successes. Consequently, advantageous macroeconomic conditions are instrumental in attracting both domestic and international investment, facilitating international trade, expanding production and business operations, and drawing entrepreneurial ventures (Castaño et al., 2015; Awoa Awoa et al., 2022).

Empirical research consistently affirms the influence of macroeconomic factors on national entrepreneurship. Castaño et al. (2015) emphasize that economic development fosters entrepreneurial activity, while Carree et al. (2002) note variations in entrepreneurship rates across different stages of economic growth. In general, strong economic growth - characterized by structural transitions from agriculture to industry and services - boosts investment, employment, and business creation. This shift lowers entry barriers, improves resource allocation, and enhances entrepreneurial opportunities.

Numerous studies confirm a positive link between GDP growth and entrepreneurship. Amorós et al. (2016) argue that sustained GDP growth fuels innovation and business formation. Sharma et al. (2023) further highlight the role of per capita GDP in fostering entrepreneurship by increasing savings and investment capacity. However, the direct impact of GDP remains debated. While economic growth generally signals a favorable business environment, Autio et al. (2014) caution that in developed economies, rapid GDP expansion may lead to market saturation, limiting entrepreneurial opportunities. These mixed findings suggest that the relationship between GDP and entrepreneurship depends on broader institutional and market conditions.

Moreover, policies on international trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) significantly and positively influence country-level entrepreneurship. Empirical studies indicate that when governments blend centralized planning and market policies with free market approaches, it stimulates imports and exports and attracts FDI, thereby encouraging domestic and international individuals to commence business ventures. Specifically, Shane and Venkataraman (2000) and Purkayastha et al. (2021) argue that economic openness fosters economic relations between countries, creating new business opportunities, where imports enhance domestic production capacity and product quality, while exports expand consumer markets, increase production activities, and generate financial rewards that encourage entrepreneurship. Additionally, Zhao (2022), Afi et al. (2022) and Sharma et al. (2023) found that FDI enhances a country’s income, improves the state budget, and enables financial accumulation, while also introducing advanced technologies, management practices, and expertise that enhance domestic technological and managerial capabilities, fostering entrepreneurship through learning and imitation.

Inflation is a key macroeconomic factor influencing country-level entrepreneurship. Moderate and well-managed inflation, reflecting a stable and growing economy, can foster a favorable entrepreneurial environment by ensuring predictable costs and investment returns. Román (1991) emphasizes the importance of government policies in maintaining price stability, which enhances business confidence and encourages new venture creation. The Consumer Price Index (CPI), a key measure of inflation, directly affects investment decisions and business sustainability (Baumol, 1990). A rising CPI, indicative of increasing inflation and currency depreciation, imposes financial burdens on entrepreneurs by escalating input costs, reducing purchasing power, and increasing market uncertainties. Persistently high inflation raises business expenses, including raw materials and wages, making it difficult for startups to manage costs and plan long-term growth. Moreover, inflation erodes consumers’ purchasing power, reducing demand for non-essential goods and services, which directly affects small businesses. Inflation also impacts access to credit, as higher CPI often leads to increased interest rates, making it more challenging for entrepreneurs to secure funding. Empirical studies support these findings, with Bjørnskov and Foss (2016) demonstrating that stable price levels and economic freedom positively influence entrepreneurship, while Li and Wu (2014) report a negative impact of high housing prices in Chinese cities on urban entrepreneurs. Although moderate inflation may stimulate economic activity, excessive CPI volatility undermines business confidence and hampers entrepreneurial growth at the national level.

From these analyses, it is posited that favorable economic factors, providing adequate resources and opportunities, will enhance country-level entrepreneurship. As outlined above, the economic factors considered in this study will include economic growth, foreign direct investment, economic openness, and consumer price index. We assume that each of these factors influences country-level entrepreneurship. Consequently, we posit the first set of the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: Economic growth significantly and positively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 1b: Foreign direct investment significantly and positively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 1c: Economic openness significantly and positively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 1d: A higher Consumer Price Index (CPI) significantly and negatively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

Impact of social factors on country-level entrepreneurship

While economic factors are instrumental in generating economic resources and market opportunities for prospective entrepreneurs, social factors equally play a crucial role in fostering entrepreneurship by creating a supportive environment conducive to economic and business development. This analysis delves into several key social factors.

Education and investment in educational initiatives are paramount in elevating the skill level of the population, a critical consideration for potential entrepreneurs contemplating business initiation. Education and training are pivotal in cultivating high-quality human resources for country-level entrepreneurship, equipping individuals with the necessary skills and knowledge for employment and entrepreneurial ventures. The positive correlation between education, training, and country-level entrepreneurship has been elucidated by Valerio et al. (2014). Additionally, Jiménez et al. (2015) examined the influence of education on entrepreneurship, finding that varying levels of education have different effects on formal and informal entrepreneurial activities.

The consumption level within a society is another factor that entrepreneurs consider alongside education when evaluating resources and conditions for starting a business. A rise in social consumption and growing domestic demand positively influence the consumer market and country-level entrepreneurship. Wennekers et al. (2005), in their study of 36 countries, demonstrated that an increase in population size and consumer market size, coupled with enhanced purchasing power, positively affects the rate of country-level entrepreneurship. Conversely, regions with low population density and weaker purchasing power face challenges in attracting investment and new business ventures compared to more populous and affluent areas. Policies aimed at stimulating consumer demand and promoting household spending can propel economic growth and influence business startup decisions (Matsuyama, 1992).

Unemployment rates and labor market conditions are additional social factors impacting entrepreneurial decisions. A low rate of unemployment positively influences economic growth, serving as a crucial metric for evaluating the effectiveness of economic policies, the quality of human resources, and national labor productivity. Stable employment and labor conditions can stimulate consumer expenditure and promote investment in economic development, thereby encouraging entrepreneurship. Research focusing on labor and unemployment policies to enhance country-level entrepreneurship (Amorós et al., 2016) suggests that policies fostering employment and wage incentives, or those aimed at increasing the rate of trained labor, positively impact investment activities and the establishment of new businesses. Furthermore, policies designed to attract labor in specific industries and regions, addressing labor shortages and the scarcity of high-quality labor in critical economic sectors, are essential and significantly influence country-level entrepreneurship.

While some studies argue that higher unemployment may encourage necessity-driven entrepreneurship, where individuals turn to self-employment due to a lack of job opportunities (Thurik et al., 2008), others indicate that persistent unemployment can hinder entrepreneurial activity by reducing overall economic stability and consumer demand (Audretsch et al., 2001). Moreover, unemployment-induced uncertainty weakens credit access, making it harder for potential entrepreneurs to secure funding for business ventures (Caliendo and Kritikos, 2010).

This study aligns with the perspective that high unemployment negatively impacts country-level entrepreneurship by limiting financial resources, increasing economic uncertainty, and reducing overall market opportunities for new businesses. Therefore, policies aimed at reducing unemployment and fostering a stable labor market are critical for sustaining entrepreneurial growth.

From these analyses, the positive impact of favorable social conditions in promoting country-level entrepreneurship is affirmed. We assume that each of these factors influences country-level entrepreneurship. Consequently, the second set of hypotheses are formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 2a: Government expenditure on education significantly and positively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 2b: Final consumption expenditure significantly and positively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 2c: Unemployment rate significantly and negatively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

Impact of institutional factors on country-level entrepreneurship

Institutional conditions play a crucial role in shaping country-level entrepreneurial activity, complementing economic and social dimensions. Key factors such as the cost of business start-up procedures, the number of registration steps, and the time required to establish a business are central to Transaction Cost Economics (TCE). These elements reflect regulatory and administrative barriers that influence entrepreneurs’ ability to enter markets efficiently. Excessive regulatory burdens and high transaction costs discourage entrepreneurship by increasing operational risks and initial capital requirements. From the Resource-Based View (RBV), an efficient institutional framework serves as a national resource that fosters innovation and economic dynamism (Audretsch and Keilbach, 2004).

Extensive research demonstrates that the prevalence of national entrepreneurship is intricately linked to the institutional frameworks governing business operations, including factors such as the costs associated with business establishment, regulatory procedures for setting up a business, and the time required for business registration (Acs and Szerb, 2007; Pfeifer et al., 2021). Regulations concerning corporate income tax, entrepreneurial expenses, and transaction costs for new businesses (including information costs, property rights protection costs, operational costs, etc.), when stringently and judiciously delineated, can foster innovation and country-level entrepreneurship.

Among these factors, the cost of registering a new business plays a pivotal role in an entrepreneur’s decision to start a venture. Policies reducing corporate income taxes and other start-up fees attract new enterprises, while stringent regulations and high tax burdens can discourage entrepreneurship (Fonseca et al., 2001; Van Stel et al., 2007).

Efficient institutional frameworks also significantly impact entrepreneurial intentions. Simplified registration procedures, supported by administrative guidance, can streamline the process and encourage business creation (Sharma et al., 2023). Empirical evidence suggests that financial support policies, including investment incentives and government subsidies for operational costs, reduce barriers to entry and stimulate entrepreneurship. Additionally, non-monetary measures, such as administrative reforms, intensive training, and market linkage support, further enhance business viability and market penetration.

The speed and simplicity of business registration are also crucial. A streamlined process reduces unofficial costs, facilitates market entry, and attracts both domestic and international investment. Transparent economic policies encourage formal business registration while minimizing informal expenses. Furthermore, access to timely and comprehensive information, market research facilitation, and registration assistance empower entrepreneurs to maximize opportunities for growth (Nyström, 2008).

The total time required to establish a business - from initiation to operational readiness - is another critical consideration. Shorter, more efficient processes encourage entrepreneurship, while prolonged and costly registration deters it. This duration is largely influenced by national policies and support mechanisms, including financial and administrative assistance, which directly impact entrepreneurial activity (Van Stel et al., 2007).

These insights reaffirm the significant role of institutional factors in shaping country-level entrepreneurship. This study examines three key factors: business start-up costs, the number of required registration procedures, and the time needed to start a business, each of which is hypothesized to influence national entrepreneurship. Accordingly, the third set of hypotheses is formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 3a: The cost of business start-up procedures significantly and negatively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 3b: The number of start-up procedures required to register a business significantly and negatively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

Hypothesis 3c: The time required to start a business significantly and negatively impacts country-level entrepreneurship.

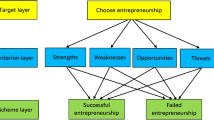

Based on the development of the above hypotheses, we have constructed the research model as follows (Fig. 1).

Research methodology

Data collection and research sample

Data pertaining to country-level entrepreneurship was sourced from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), a widely recognized open database and international organization dedicated to researching the evolution and activities of entrepreneurs and nascent enterprises. GEM stands as a reputable resource for scholars, governmental bodies, and non-profit organizations, facilitating the monitoring and evaluation of entrepreneurial development across various nations.

Additionally, data concerning the macro factors of countries were obtained from the open database of the World Bank. As a prominent international organization, the World Bank’s core focus is on fostering economic development and mitigating poverty globally. Its database presents comprehensive and reliable information on diverse facets of national economies. Key macro factors, including economic and social conditions, public finance, international trade, and other socio-economic indicators, are consistently gathered and updated by the World Bank.

In this study, data from these two sources were meticulously compiled and organized by year and respective country. The data underwent a rigorous cleaning process, followed by a careful selection of pertinent economic and social indicators to align with the research objectives, prioritizing the comprehensiveness of macro factors. The resultant research sample encompasses data from 70 countries spanning the years 2003 to 2019, culminating in 605 year-observations (Table 2). Notably, within the 70-country sample, nations such as the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Slovenia and Spain provided complete data spanning 17 years, while the remaining countries contributed data for a minimum of one year or more. The sample’s composition, categorized by development level, includes 2 least-developed countries (constituting 2.86% of the sample), 34 developing countries (48.57%), and 34 developed countries (48.57%). This diversity resulted in an unbalanced panel dataset for this study, as the data sourced from the GEM database are not continuously available for every country across all years.

Variable Measurement

The dependent variable is Total early-stage Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA), collected from GEM data. This variable measures the proportion of businesses in the early stages of entrepreneurial activities. TEA assesses the percentage of the working-age population owning a newly established business (owner-manager of a new business up to 3.5 years) or actively and diligently starting a business (nascent entrepreneur). Therefore, TEA represents the aggregate rate of newly established businesses and business owners (without double counting). This indicator is used as the dependent variable in the study due to its high reliability from GEM data and its extensive use in research (Solomon et al., 2021; Kalisz et al., 2021; Afi et al., 2022).

The independent variables related to the macro factors of countries in this study were collected from the World Bank’s open-access database. The selection of these variables was based on the theoretical framework, as presented in “The choice of determinant of macro-level entrepreneurship”. Additionally, these variables were considered based on data availability according to the following three key criteria (i) Data availability - ensuring that the selected variables had minimal missing values to allow comprehensive coverage across countries and years; (ii) Relevance - selecting variables that effectively capture the economic, social, and institutional conditions influencing entrepreneurship at the national level; (iii) Minimal correlation - avoiding potential multicollinearity issues to ensure the robustness of the regression model. By adhering to these criteria, the selected variables provide a well-balanced representation of macroeconomic conditions while maintaining statistical reliability. These variables include:

-

Economic Growth (ECO), as utilized in prior studies by Afi et al. (2022) and Awoa Awoa et al. (2022), is the annual percentage growth rate of GDP, calculated in constant 2015 USD. GDP, the gross domestic product, includes the value of all final goods and services produced within a country’s territory over a specified time period. From a consumption perspective, GDP also reflects the total demand of the economy, including final consumption by households, final consumption by the state, investment, and international trade. In terms of income, GDP includes labor income, production taxes, fixed asset depreciation, and production surplus. From a production perspective, GDP is calculated by subtracting intermediate consumption costs. Thus, GDP is an important macroeconomic indicator assessing economic development and is expected to have a positive impact on country-level entrepreneurship.

-

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is a form of long-term investment by an individual or company from one country into another through establishing business operations and companies. Foreign investment is often encouraged through preferential policies and tax support from governments; other policies such as improving the business environment, upgrading infrastructure, enhancing human resource quality, and expanding raw material sources, directly and indirectly stimulate various economic and social aspects, thereby positively impacting country-level entrepreneurship.

This indicator is measured by the ratio of inflow foreign direct investment to the target country’s GDP. FDI, as referenced in the studies of Awoa Awoa et al. (2022), is expected to positively influence country-level entrepreneurship.

-

Economic Openness (OPE) - The degree of openness of an economy is the extent to which external entities can participate in the domestic economy. Economic openness is measured by the ratio of total international trade (exports and imports) to the target country’s GDP (Awoa Awoa et al., 2022). The openness of an economy reflects a country’s ability to participate in the global market, thereby directly and indirectly creating business opportunities for potential entrepreneurs. Therefore, economic openness is expected to have a positive impact on country-level entrepreneurship.

-

Consumer Price Index (CPI) reflects changes and fluctuations in prices that consumers must pay to purchase a basket of goods, based on periodic consumer price surveys, comparing the current period with the base year of 2010. Continuous general price increases over time and the depreciation of a currency in macroeconomic terms are inflation. A higher CPI indicates currency depreciation, creating financial pressure for potential entrepreneurs, reducing the ability to start a business, and thus negatively impacting country-level entrepreneurship.

-

Government Expenditure on Education (GEE) is calculated as a percentage of GDP, for comparison between countries (Dheer, 2017; Harraf et al., 2021). A high government expenditure rate on education indicates priority investment in education and human resource training, a crucial resource and driver for economic development. Moreover, investment in education is a crucial condition and prerequisite for innovation and positively influences country-level entrepreneurship.

-

Final Consumption Expenditure (FCE) as referenced in the studies of Solomon et al. (2021), is the total expenditure of households and government consumption, measured by calculating the proportion of expenditure relative to GDP. Final consumption is determined based on the principle that the user of goods and services is the final consumer. The total market expenditure is important information reflecting the market size where high consumer demand for goods creates a potential market that attracts investment, product development, and new business establishment. To ensure comparability between countries of different economic sizes, this index is calculated as a percentage of GDP.

-

Unemployment Rate (UEM) is the proportion of the labor force (% of total labor force) unemployed but ready and searching for work, with specific definitions varying by country. The unemployment rate is an important measure for evaluating the effectiveness of socio-economic development strategies; assessing the achievement of sustainable economic and social growth and development goals. A high unemployment rate is also a barrier to innovation and business expansion, negatively impacting the assessment of resources and business opportunities for potential entrepreneurs to decide to start a business. Therefore, this indicator is expected to have a negative relationship with country-level entrepreneurship (Amorós et al., 2016).

-

Cost of Business Start-up Procedures (COS) is measured as a percentage of GNI per capita. This indicator represents the official cost of starting a new business as defined in the institutions of each country (Acs and Szerb, 2007; Van Stel et al., 2007). At the same time, policies related to reducing, exempting, and supporting taxes and fees for newly registered businesses help reduce start-up costs and encourage entrepreneurship. Although the cost of starting a business is a small part of the expenses from the initial idea to the decision to establish and operate a new business, it is also considered to have a negative relationship with country-level entrepreneurship.

-

Start-up Procedure Number to Register a Business (PRO) represents the formal procedures necessary to start a business, measured by the number of procedures required to register a business.

This indicator, as utilized in prior studies by Dheer (2017) and Harraf et al. (2021), includes completing regulated forms, verifying information, decision-making, and notifications for business operations. Some data and information related to newly established businesses such as capital size and labor, business type, ownership form, operational industries, etc., will be verified and announced on the national business registration system. Reducing the number of procedures and simplifying the registration process cuts costs, time, and other potential informal costs for potential entrepreneurs. Policies that simplify establishment procedures for business registration create more favorable conditions for business founders, improve the business environment, and promote country-level entrepreneurship.

-

Time Required to Start a Business (TIM) is calculated as the number of days required to complete business establishment procedures and for a newly established business to begin legal operations (Van Stel et al., 2007). Policies that simplify establishment procedures and new registration forms (online declarations, online registrations, etc.) contribute to shortening business registration time, reducing costs compared to traditional methods. Policies and solutions to shorten time help create conditions that encourage potential entrepreneurs in particular and country-level entrepreneurship in general.

The descriptive statistics of the variables are presented in Table 3 below.

The Pearson correlation matrix (Table 4) indicates that multicollinearity is not a major concern, as none of the independent variables exhibit excessively high correlation coefficients. The highest significant ones (e.g., PRO and TIM: 0.569; PRO and COS: 0.542; FCE and OPE: −0.507) remain within an acceptable range. Additionally, all VIF values of the independent research variables are below 2. These results suggest that the model estimates should not be significantly affected by collinearity issues.

Panel data analysis

In this study, we employ the panel data analysis approach, incorporating time effects. This regression method allows us to control for unobserved heterogeneity across countries while capturing temporal dynamics that may influence entrepreneurship levels. Given our unbalanced dataset, spanning 70 countries from 2003 to 2019 with 605 year-observations, time effects are incorporated to control for unobserved time-specific factors that may influence all observations in the given period. This adjustment helps address omitted variable bias, improve instrument validity in panel data estimation, and reduce serial correlation in the error terms, ensuring more reliable coefficient estimates.

Specifically, to determine the appropriate regression model, we first check for endogeneity among the independent variables, using the Durbin (Score) and Wu-Hausman tests (Durbin, 1954; Wu, 1973). Endogeneity arises when explanatory variables are correlated with the error term, leading to biased and inconsistent estimates. This issue is particularly pertinent in macroeconomic studies, where reverse causality and omitted variables often pose significant threats to inference. Given our unbalanced panel dataset, which spans multiple countries over an extended time period, addressing endogeneity at the outset ensures that our econometric analysis produces reliable and interpretable results.

If no evidence of endogeneity is detected among the research variables, we proceed with the model selection process outlined by Dougherty (2011), considering three pertinent models: (i) the pooled Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model with time dummies, (ii) the time random-effects model (REM), and (iii) the time fixed-effects model (FEM). Accordingly, the Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test is utilized to compare time REM with the pooled OLS model with time dummies, evaluating the presence of random effects. If random effects are detected, time REM is chosen; otherwise, the pooled OLS model is adopted. Additionally, the Hausman test is applied to determine whether time REM or time FEM is appropriate. This test is instrumental in ascertaining whether there is a notable discrepancy between the estimates derived from these two models, thereby guiding the selection of the most fitting model for the panel data under consideration. Then, depending on the chosen model, whether issues such as heteroscedasticity, serial correlation, or cross-sectional dependence are present, we utilize techniques such as PCSE (Panel-Corrected Standard Errors), FGLS (Feasible Generalized Least Squares), or MLE Random-Effects with Multiplicative Heteroscedasticity to address these concerns and ensure the validity of the estimates (Wooldridge, 2002).

If endogeneity is detected among the research variables, we employ the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) (Arellano and Bond, 1991; Blundell and Bond, 1998), specifically the system GMM, to properly analyze the impact of macro factors on country-level entrepreneurship. System GMM improves efficiency by using both level and first-difference equations, reducing the weak instrument problem and providing more robust estimates. It is particularly suitable for studying macro determinants of country-level entrepreneurship, as it accounts for dynamic relationships and captures both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends.

Regarding our dataset, the significant Durbin (Score) and Wu-Hausman tests for endogeneity (Durbin, 1954; Wu, 1973) reveal that the variables OPE, CPI, UEM, and PRO, as shown in Table 5, exhibit endogeneity. Additionally, the significant Wooldridge test for autocorrelation in panel data indicates the presence of serial correlation (Wooldridge, 2002). These findings imply that dynamic GMM with time dummies is the most appropriate model for our study in addressing these issues. GMM, once the validity tests (such as the Arellano-Bond test, Sargan test, Hansen test and difference-in-Hansen tests) are ensured (Arellano and Bond, 1991; Sargan, 1958; Hansen, 1982; Roodman, 2009), is well-suited for addressing not only endogeneity but also issues of heteroscedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-sectional dependence, making it a robust choice for our unbalanced dataset, which spans 70 countries over 17 years with a relatively large cross-section and a moderate time frame.

In the chosen system GMM model, the two-step GMM estimator was employed because it provides robust standard errors and corrects for heteroskedasticity, making it more efficient than the one-step estimator (Roodman, 2009). Time effects were incorporated to control for unobserved time-specific influences that could bias the estimates. Lagged variables ranging from t-2 to t-4 were used as instruments to mitigate endogeneity concerns and ensure the validity of the model. These lag lengths were chosen because using t−1 lags may still introduce endogeneity due to potential correlation with the error term, whereas lags from t−2 to t−4 are more likely to be exogenous while still containing useful information about the dependent variable. Because the two-step GMM estimator can suffer from overfitting of instruments when the number of instruments is too large, potentially weakening the reliability of the estimates; we apply the collapse option to limit instrument proliferation and enhance the robustness of the estimation. The final GMM results are presented in Table 5.

Research findings and discussions

The validity of our system GMM model with time dummies is confirmed through diagnostic tests in Table 5, that assess instrument validity and the presence of autocorrelation. A crucial requirement for the GMM estimator is that while first-order serial correlation (AR(1)) is expected due to the nature of the differencing process, second-order serial correlation (AR(2)) should not be present to ensure valid moment conditions. The Arellano-Bond test results in Table 5 align with these expectations: the test for AR(1) is statistically significant (p = 0.008), indicating a negative first-order correlation, which is an inherent feature of the system GMM approach. More importantly, the AR(2) test is not significant (p = 0.484), confirming the absence of second-order correlation and ensuring that the lagged variables used as instruments are not endogenous.

Furthermore, the validity of the instrument set is supported by the Sargan and Hansen tests for overidentifying restrictions. With 38 instruments (<70 country groups), our system GMM model remains within an acceptable range, mitigating the risk of instrument proliferation and ensuring the reliability of the Hansen test. The Sargan test (p = 0.378) and Hansen test (p = 0.524) both fail to reject the null hypothesis that the instruments are valid, suggesting that the model does not suffer from instrument proliferation or endogeneity issues. The Difference-in-Hansen test for the GMM instruments in levels further reinforces this conclusion (p = 0.706 for the exclusion test and p = 0.244 for the difference test), confirming that the instrument set used in levels does not introduce bias.

Overall, the regression results suggest that our system GMM estimation is valid, with no strong evidence of instrument proliferation, second-order serial correlation, or overidentification problems. Additionally, the significant Wald chi-squared test statistic (p = 0.000) strongly rejects the null hypothesis that all coefficients are jointly zero, indicating that the independent variables collectively have significant predictive power. Consequently, the model’s estimated coefficients can be considered robust and reliable for interpretation in our panel data context.

The regression results indicate that country-level entrepreneurship (TEA) exhibits a degree of persistence over time, as suggested by the insignificant coefficient of the lagged dependent variable (L1 = 0.322 and p = 0.115). Regarding temporal variations, the coefficients for the years 2004 to 2010 suggest a downward trend in entrepreneurship in countries, with statistically significant declines in most years. However, the results for the later years (2011–2019) are largely insignificant, indicating a potential rebound. Regarding independent variables, while economic growth (ECO) and foreign direct investment (FDI) exert a positive impact, economic openness (OPE) and final consumption expenditure (FCE) negatively influence the country-level entrepreneurship. In contrast, government expenditure on education (GEE), unemployment rate (UEM), cost of starting a business (COS), Start-up procedure number to register a business (PRO), and time required to start a business (TIM) do not exhibit statistically significant impact on the country-level entrepreneurship. These findings allow us to further analyze the proposed research hypotheses in the following subsections

Economic factors and country-level entrepreneurship

The results from the GMM model (Table 5) provide insights into the relationship between economic factors and country-level entrepreneurship.

The impact of Economic Growth

The analysis indicates that economic growth (ECO) significantly and positively influences country-level entrepreneurship at 95% confidence-level, with a coefficient of 0.167 and a p-value of 0.020. Consequently, hypothesis H1a is supported. The coefficient of 0.167 suggests that a 1% increase in economic growth is associated with a 16.7% increase in country-level entrepreneurship, holding other factors constant. Notably, economic growth exhibits the strongest effect among all independent variables examined. This highlights the practical significance of the relationship and underscores the role of economic growth in fostering entrepreneurial activity at the national level.

This finding provides strong empirical support for the Resource-Based View (RBV), which posits that access to economic resources is essential for entrepreneurial activity as it increases financial capital, enhances innovation potential, and improves overall market conditions. Economic expansion facilitates both the supply and demand sides of entrepreneurship: greater financial resources and institutional support lower entry barriers, while rising GDP boosts consumer purchasing power and market opportunities. Our result aligns with prior research demonstrating the positive relationship between economic growth and country-level entrepreneurship. Amorós et al. (2016) emphasize that consistent GDP growth stimulates innovation and encourages the establishment of new businesses. Similarly, Sharma et al. (2023) highlight that higher per capita GDP enhances savings and investment capacity, which in turn supports entrepreneurial at the country level.

The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

The GMM regression results indicate that FDI significantly and positively affect country-level entrepreneurship at the 95% confidence level, with a coefficient of 0.026 and a p-value of 0.002. Thus, hypothesis H1b is supported. Specifically, the coefficient of 0.026 suggests that a 1% increase in FDI is associated with a 2.6% increase in country-level entrepreneurship, holding other factors constant. In RBV perspective, this interpretation underscores the importance of FDI in promoting entrepreneurial activity, highlighting its role in providing financial and managerial resources, business opportunities in participating in global supply chains that support entrepreneurial ventures.

This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that FDI has a positive impact on country-level entrepreneurship. Specifically, Zhao (2022) highlights that FDI not only boosts a country’s income but also improves government revenues, which facilitates financial accumulation and increases savings. These enhanced financial resources create a more favorable environment for entrepreneurial ventures, providing the necessary capital to foster new businesses. Furthermore, FDI introduces advanced technologies, management practices, and expertise, as noted by Afi et al. (2022), which are essential for enhancing domestic technological and managerial capabilities. Through learning and imitation processes, these external knowledge transfers improve local firms’ competitiveness and innovation capacity. Consequently, FDI contributes not only by providing financial resources but also by improving the overall business ecosystem, making it more conducive to entrepreneurship in countries.

The Impact of Economic Openness (OPE)

Economic openness (OPE) is the only economic factor found to significantly and negatively influence country-level entrepreneurship, with a coefficient of -0.050 and a p-value of 0.000. Thus, hypothesis H1c is not supported. This suggests that a 1% increase in economic openness is associated with a 5% decrease in country-level entrepreneurship, holding other factors constant, indicating that greater exposure to global competition may create barriers for new domestic ventures in countries.

Contrary to prior research (Shane and Venkataraman, 2000; Purkayastha et al., 2021), our result reveals the negative relationship between international trade and country-level entrepreneurship. This unexpected finding may be explained by the structural effects of international trade on domestic entrepreneurship. Greater economic openness intensifies competition from established foreign firms, making it more difficult for local entrepreneurs to enter and sustain businesses (Solomon et al., 2021). Export-oriented growth often favors larger, well-established firms, limiting opportunities for smaller enterprises and reducing the incentives for new business creation. Additionally, increased reliance on imports can suppress domestic innovation and reduce demand for local products and services, as consumers and businesses opt for higher-quality or lower-cost foreign alternatives. Over time, these pressures may weaken the entrepreneurial ecosystem, discouraging risk-taking and innovation, particularly in industries where imported goods dominate the market. These dynamics suggest that, under certain conditions, international trade may hinder rather than foster entrepreneurial activity.

The Impact of Inflation (CPI)

Results from the GMM model show that the independent variable CPI does not significantly impact national entrepreneurship at the 95% confidence level, with a coefficient of −0.011 and p-value of 0.096. Thus, hypothesis H1d is not supported.

While some studies, such as Li and Wu (2014) found that high inflation negatively affects entrepreneurship in China, our results suggest that inflation does not directly stimulate or hinder entrepreneurship. This finding aligns with Sutter et al. (2019), who argued that although inflation influences macroeconomic stability, its direct impact on entrepreneurship is often mitigated by factors such as credit availability and policy interventions.

Conclusion on economic factors

Among the examined economic factors, economic growth and FDI positively influence country-level entrepreneurship, whereas only economic openness has a negative impact. In contrast, inflation do not demonstrate significant direct effect. These findings suggest that while inflation alone may not directly drive entrepreneurship; GDP growth, FDI and economic openness plays a crucial role in fostering entrepreneurial activity by expanding market opportunities, facilitating knowledge exchange, and enhancing access to foreign capital and global supply chains.

Social factors and country-level entrepreneurship

The results of the GMM model in Table 5 reveal the relationship between social factors and country-level entrepreneurship as follows:

The effect of Government Expenditure on Education (GEE)

According to the GMM model, government expenditure on education (GEE) has an insignificant impact on national entrepreneurship at the 95% confidence level (coefficient = −0.255 and p-value = 0.402). Thus, hypothesis H2a is not supported. This finding does not align with the previous research of Jiménez et al. (2015) and Valerio et al. (2014) who emphasize the role of education in enhancing entrepreneurial skills, fostering innovation, and supporting business creation.

In reality, investing in education may not always lead to positive outcomes for country-level entrepreneurship, as the relationship between education and entrepreneurship can be complex. Indeed, Jiménez et al. (2015) indicate that while tertiary education positively influences formal entrepreneurship, it negatively affects informal entrepreneurship, as individuals with higher education may prefer formal business activities. Also, secondary education has a positive impact on formal entrepreneurship but has little to no effect on informal entrepreneurship. Dheer (2017) even identifies a negative relationship between educational investment and country-level entrepreneurship, suggesting that higher levels of education might discourage entrepreneurship. This could be because educated individuals often opt for stable, salaried employment over starting a business, especially in economies with limited entrepreneurial support. These findings suggest that the impact of education on country-level entrepreneurship varies based on education level and type of entrepreneurship, challenging the assumption that educational investment universally promotes entrepreneurial activity in countries.

The impact of Final Consumption Expenditure (FCE)

Final consumption expenditure (FCE) is the only social factor found to significantly but negatively influence country-level entrepreneurship, with a coefficient of −0.152 and a p-value of 0.018, thus failing to support hypothesis H2b. Specifically, a 1% increase in FCE is associated with a 0.152% decrease in country-level entrepreneurship, suggesting that higher consumption spending may reduce resources available for entrepreneurial activities or shift economic incentives away from business creation.

The inverse relationship between consumption expenditure and entrepreneurship can be explained through personal finance and labor market conditions. Higher consumption reduces individual savings, limiting financial resources for potential entrepreneurs, especially those with restricted access to credit. Additionally, a strong labor market with abundant job opportunities and attractive wages may discourage individuals from pursuing entrepreneurship due to the stability of salaried employment. Conversely, during periods of lower consumption, individuals tend to save more, increasing the availability of personal capital for entrepreneurial activities, highlighting the significant influence of economic cycles on business creation in countries.

The impact of Unemployment Rate (UEM)

CPI does not significantly impact business entrepreneurship

The results from the GMM regression indicate that the unemployment rate (UEM) does not significantly impact country-level entrepreneurship at the 95% confidence level, with a coefficient of 0.079 and a p-value of 0.467. Thus, hypothesis H2c is not supported.

The absence of a significant relationship between unemployment and entrepreneurship contradicts conventional expectations but is consistent with the mixed findings of prior empirical studies. While some researchers argue that higher unemployment fosters necessity-driven entrepreneurship (Thurik et al., 2008), others emphasize its detrimental effects on entrepreneurial activity due to economic instability and weakened consumer demand (Audretsch et al., 2001; Galindo da Fonseca, 2022). From the perspective of the Theory of Bounded Variability (TBV) and transaction cost economics, unemployed individuals face a dilemma: on one hand, they may be motivated to seek new income sources through entrepreneurship; on the other hand, limited financial resources and the high opportunity costs associated with entrepreneurial risks constrain their ability to start a business. This trade-off may explain the lack of a clear relationship between unemployment and country-level entrepreneurship.

Conclusion on Social Factors

Among the three social factors examined, only final consumption expenditure has a direct but negative impact on country-level entrepreneurship, whereas government expenditure on education and unemployment do not influence the entrepreneurial activity. These findings suggest that while household spending patterns can influence business creation, public investments in social sectors may not directly contribute to higher entrepreneurial activity, possibly due to structural inefficiencies or the inertia of social factors.

The institutional factors and country-level entrepreneurship

According to the results of the GMM model in Table 5, the relationship between institutional factors and country-level entrepreneurship is as follows:

The impact of costs for business start-up procedures (COS)

The regression results reveal that the independent variable COS does not have a statistically significant effect on country-level entrepreneurship at the 95% confidence level, with a coefficient of 0.079 and a p-value of 0.172. Consequently, hypothesis H3a is not supported. This finding challenges our initial hypothesis and deviates from previous studies, such as Fonseca et al. (2001), which argued that higher start-up costs discourage entrepreneurial activity. The discrepancy highlights the varying effects of start-up costs across different economic contexts and underscores the necessity for further empirical research.

A possible explanation is that, in many countries, the financial burden of business start-up costs is relatively minor compared to the broader costs associated with conceptualizing a business idea and sustaining operational expenditures. Furthermore, a global trend has emerged in which governments are actively reducing bureaucratic hurdles and streamlining business registration procedures. These efforts help mitigate both official and unofficial costs, minimizing their potential deterrent effect on entrepreneurship.

The impact of the number of procedures required to register a business (PRO)

The analysis indicates that the independent variable PRO does not have a significant impact on country-level entrepreneurship at the 95% confidence level, with a coefficient of 0.404 and a p-value of 0.232. Thus, hypothesis H3b is not supported. This finding contradicts prior research by Van Stel et al. (2007), Pfeifer et al. (2021), and Sharma et al. (2023) who highlight that regulatory complexity hinders entrepreneurship, while administrative simplifications promote business creation.

The lack of a significant relationship between the number of procedures required to register a business and country-level entrepreneurship suggests that administrative complexity alone may not be a decisive factor in entrepreneurial activity. While streamlined registration processes can reduce bureaucratic burdens, other structural conditions (such as access to finance, market opportunities, and regulatory stability) may play a more influential role in shaping entrepreneurial decisions. Moreover, in many countries, entrepreneurs adapt to complex registration systems through informal networks, legal intermediaries, or digital solutions, mitigating the direct impact of procedural requirements. Additionally, the perceived benefits of formalization, such as legal protection and market access, may outweigh the costs associated with registration complexity, leading entrepreneurs to proceed with business creation regardless of administrative hurdles.

The impact of time required to start a business (TIM)

The regression results indicate that the independent variable TIM does not significantly affect national entrepreneurship at the 95% confidence level, with a coefficient of −0.014 and a p-value of 0.652. Consequently, hypothesis H3c is not supported.

This suggests that the duration of business registration, when considered in isolation, does not exert a direct influence on entrepreneurial activity. This finding diverges from previous research, which suggested that prolonged registration timelines could discourage business formation (Van Stel et al., 2007; Pfeifer et al., 2021). However, the time required to start a business is closely associated with bureaucratic inefficiencies, which were identified by Pfeifer et al. (2021) as influencing entrepreneurship. Nonetheless, similar to the cost factor, time alone does not have a statistically significant impact on country-level entrepreneurship.

Conclusion on Institutional Factors

None of the three institutional factors examined (including: cost of business start-up procedures, number of start-up procedures required to register a business, and time required to start a business) show a significant impact on country-level entrepreneurship. These surprising findings suggest that either countries have made substantial efforts to improve institutional quality; advancements in modern technology have mitigated the influence of institutional barriers; or such barriers are relatively insignificant and ignorable compared to entrepreneurial motivation.

Conclusion and policy implications

Main findings

Grounded in the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Transaction Cost Economics (TCE), this study examines the influence of three groups of macroeconomic factors on country-level entrepreneurship, encompassing ten variables related to economic, social, and institutional factors. The analysis utilizes panel data collected from two key sources - the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor and the World Bank—covering the period from 2003 to 2019, with a dataset comprising 605 observations across 70 countries. The empirical results indicate that four out of ten research hypotheses are supported, as summarized in Table 6.

The study identifies four key independent variables that significantly influence country-level entrepreneurship, including economic growth, FDI, economic openness and consumption expenditure. Conversely, contrary to initial expectations, several individual factors—including: inflation (CPI), investment in education, unemployment, start-up costs, start-up procedures and the time required to start a business—do not exhibit a statistically significant impact on national entrepreneurship.

Notably, our findings underscore that economic growth and FDI foster entrepreneurship at the country level, whereas higher economic openness and consumption expenditure act as barriers. Among these, consumption expenditure is the most crucial determinant, followed by economic growth, economic openness, and FDI.

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the existing literature on entrepreneurship by providing empirical evidence on the macro-level determinants of country-level entrepreneurship through the theoretical lenses of the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Transaction Cost Economics (TCE). The findings reinforce and extend these theories by demonstrating how macro factors shape entrepreneurial activity at the national level.

From the RBV perspective, our findings strongly reaffirm the critical role of resource availability and sufficiency, particularly economic resources, in fostering country-level entrepreneurship. Specifically, economic growth exhibits the most substantial positive effect, highlighting that an expanding economy provides greater access to financial capital, improved market conditions, and institutional support that collectively lower entry barriers for new ventures. This supports the RBV argument that resource availability determines entrepreneurial success, as a thriving economy not only enhances financial security but also boosts consumer purchasing power, thereby increasing demand for new businesses. Similarly, FDI plays a crucial role in providing both financial and managerial resources, as well as access to global supply chains, thereby strengthening entrepreneurial opportunities. These results reinforce RBV’s assertion that access to critical resources is a prerequisite for sustained entrepreneurial activity, emphasizing that economic expansion and international investment flows are essential for stimulating business creation and innovation.

Furthermore, the positive impact of FDI on entrepreneurship aligns with RBV’s emphasis on knowledge transfer and capability development. FDI facilitates the inflow of advanced technologies, managerial expertise, and financial resources that enhance domestic firms’ competitiveness. Through learning and imitation, local entrepreneurs can leverage these external resources to improve efficiency and develop innovative business models. This reinforces the theoretical proposition that economic resources, both domestic (economic growth) and foreign (FDI), serve as key enablers of entrepreneurship by providing the necessary resource infrastructure to support new venture creation.

From the TCE perspective, our findings highlight the opportunity costs and adverse selection problems that entrepreneurs face when deciding to start a business. The negative impact of final consumption expenditure suggests that higher consumer spending may reduce the resources available for entrepreneurial activities, either by limiting personal savings or by creating more attractive alternative career options in the labor market. This aligns with TCT’s argument that individuals weigh the costs and benefits of entrepreneurial entry, and when consumption-driven economic environments offer stable employment opportunities, the opportunity cost of starting a business increases. Consequently, fewer individuals are incentivized to engage in entrepreneurship due to the higher perceived risk and lower expected returns.

Similarly, the negative impact of economic openness on entrepreneurship underscores the role of transaction costs in shaping business entry decisions. Increased international competition raises market entry barriers for domestic entrepreneurs, making it more costly and riskier to establish new ventures. This supports TCT’s argument that higher transaction costs - arising from intensified foreign competition, regulatory challenges, or shifting market dynamics - can discourage entrepreneurial activity. Entrepreneurs must navigate these uncertainties while managing resource allocation, further validating TCT’s proposition that market structures and external competitive pressures significantly influence business formation. These findings reinforce the theoretical premise that the costs associated with entrepreneurship, including opportunity costs and external market uncertainties, play a crucial role in shaping country-level entrepreneurial dynamics.

Policy implications

The findings of this study offer important policy implications for fostering country-level entrepreneurship. The strong impact of economic factors suggests that policymakers should prioritize resource availability over cost-reduction strategies to stimulate entrepreneurship. While institutional quality remains important, its unexpected and insignificant impact implies that entrepreneurs may not yet face significant institutional barriers or may not fully account for institutional costs in their decision-making. This indicates that instead of focusing solely on reducing regulatory burdens, policies should emphasize enhancing access to financial capital, technology, and market opportunities. By adopting a resource-centric approach, governments can ensure that aspiring entrepreneurs have the necessary means to establish and sustain their ventures, fostering a more dynamic and resilient entrepreneurial ecosystem.