Abstract

Online cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT)-based interventions have shown the potential to improve the mental health of university students. However, their impact on West Asian cultures and educational achievement has yet to be fully investigated. This study explores the feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of a self-directed, internet-delivered, cognitive–behavioural skills training programme (MoodGYM) in reducing depression and improving academic performance among university students in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This exploratory pre- and postintervention study with a historical control group recruited 50 students, having a GPA <2 and self-reporting at least one of two key depressive symptoms, from one UAE university. The results demonstrated that the total Hospital Depression and Anxiety Scale (HADS) depression score (HADS-D) decreased after the intervention (P = 0.004), and the proportion of participants scoring above the cutoff for depression (HADS-D ≥8) decreased from 77.2 to 27.3% (p < 0.001). There was also a significant reduction in HADS-anxiety scores (p < 0.001), and the proportion of participants above the cut-off for anxiety (HADS-A ≥8) decreased from 50% to 11.4% (p = 0.001). GPA improved significantly over time (p < 0.001, d = 1.3), and attendance warnings decreased (p = 0.008, d = 0.6). Most students (79.6%) evaluated MoodGYM as useful, and all students completed at least two MoodGYM modules. This study shows that MoodGYM, a web-based mental health promotion intervention, improves academic achievement in university students with depressive symptoms. Further research is needed to explore how MoodGYM can be best implemented within university settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Empirical evidence suggests a high prevalence of mental health problems, such as depression, among university students compared with their nonstudent peers (Ibrahim et al., 2013). This is concerning, as depression has been shown to impact all aspects of student well-being, including academic achievement. Students with depressive symptoms tend to have poor classroom engagement, peer interactions, and attendance (Abu Ruz et al., 2018). Thus, depression negatively influences academic performance and fosters underachievement among university students.

A recent representative survey (Awadalla et al., 2020) reported that over one-third of university students at a university in the UAE scored above the threshold for major depressive disorder. Depressive symptoms at baseline—but not anxiety symptoms—predicted academic performance (grade point average [GPA]) at follow-up. This finding supports previous evidence that depression negatively impacts university students’ academic performance (Deroma et al., 2009) and suggests that an intervention to help students manage their low mood could reduce this educational disadvantage. However, while these studies provide valuable insights, they often fail to account for other contributing factors, such as learning difficulties, socioeconomic status, and external stressors, that may also impact academic performance (Richardson et al., 2012). Furthermore, existing studies rely primarily on self-reported data, which may introduce bias in the assessment of both depressive symptoms and academic outcomes (Auerbach et al., 2016).

Mental health resources in many Arab countries are limited, and negative societal attitudes toward mental health care create significant barriers to seeking help (Dardas and Simmons, 2015). Research in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region and the broader Middle East suggests that university students experience high levels of psychological distress, often intensified by academic pressures, cultural expectations, and stigma associated with mental illness (Al-Gelban, 2009; Dardas and Simmons, 2015). These challenges contribute to reduced mental health support utilisation, leaving many students without adequate psychological care.

In addition to stigma and limited resources, other factors uniquely impact the mental health of university students in the UAE. These include family expectations, financial stress, academic competition, and limited access to culturally tailored mental health services (Al-Darmaki, 2003). Moreover, the competitive nature of higher education in the UAE places immense pressure on students to excel, leading to increased academic-related stress and burnout (Eapen et al., 2021). These factors further reduce mental health support utilisation, leaving many students without adequate psychological care.

In this context, online therapeutic interventions can offer considerable advantages in terms of access and privacy. Technology-based interventions could fill the gap between the need for and access to mental health services among university students (Harrer et al., 2018). There is a growing need to create supportive environments for students who may experience emotional difficulties during university life (January et al., 2018). ‘Internet-delivered technology’ in counselling refers to psychological online interventions utilising various multimedia formats and interactive features to engage users and promote intervention effectiveness (Grist et al., 2019). Customisation to meet student needs, anonymous access, and a more comfortable setting to access sensitive information are advantages of internet-delivered interventions (Harrer et al., 2018). These advantages have increased attention to online interventions, with several studies examining such programmes (Farrer et al., 2013).

Online interventions can effectively improve university students’ mental health (Barrable et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2014). However, their impact on educational attainment has yet to be fully explored. Bolinski et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review of the impact of online mental health interventions on academic performance. A meta-analysis of the six randomised–controlled trials that included academic performance as an outcome revealed beneficial effects for depression, while only a small, nonsignificant effect was found for academic achievement. However, none of the six studies targeted students who had symptoms of depression and struggled academically at baseline.

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is a collaborative therapy that focuses on how a person’s thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes affect their emotions and behaviours (Gaudiano, 2008). CBT is the recommended treatment for mild to moderate depression and has been proven effective (Lopez and Basco, 2015). However, limited access—particularly in middle- and low-income countries—and the stigma associated with poor mental health may hinder access to physical treatment resources (Sweetland et al., 2014). Thus, cost-effective and widely accessible alternatives to in-person treatment are needed. Adolescents use technology at high rates (Anderson et al., 2017), yet innovative online treatment methods have not fully exploited student proficiency. For example, despite evidence confirming the effectiveness of computerised CBT for reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms, to our knowledge, no study has evaluated a CBT-based online intervention targeting students with depressive symptoms who are struggling academically.

Academic struggles can manifest in various forms, including low GPA, frequent absenteeism, difficulty concentrating, procrastination, reduced class participation, and failure to complete coursework on time (Conley et al., 2014). These challenges often heighten academic stress, diminish motivation, and lower self-confidence, which can further contribute to mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety (Beiter et al., 2015). Given the close relationship between mental health and academic performance, it is crucial to develop targeted interventions that address both psychological well-being and educational challenges to effectively support struggling students.

MoodGYM (https://moodgym.anu.edu.au/welcome/faq) is an online CBT-based programme designed to prevent symptoms of emotional distress and various mental health disorders in adolescents and has shown promise in Australian studies (Gratzer and Khalid-Khan, 2016). MoodGYM comprises five modules involving written information, animations, interactive exercises, and quizzes designed to teach skills known to prevent depression and anxiety among young people (Christensen et al., 2006; Farrer et al., 2012).

Research has investigated the effects of MoodGYM across various settings and using different study designs. Twomey and O’Reilly (2016) conducted a systematic review of 11 studies to evaluate the effectiveness of MoodGYM in reducing depressive symptoms and general psychological distress in adults. They reported that studies with no treatment controls, face-to-face guidance, and high adherence to MoodGYM modules revealed a more positive effect on depression symptoms and other forms of psychological stress. Furthermore, a stronger effect was found in studies conducted in Australia than in those conducted in Europe. The authors concluded that MoodGYM could provide primary support to participants with mental health issues. However, it should be noted that adherence rates and cross-cultural factors may affect the influence of CBT web-based programmes. Furthermore, more studies are needed to investigate the impact of MoodGYM and other CBT web-based interventions in West Asian cultures, including Arab communities.

In addition to MoodGYM, several other digital mental health programmes may effectively address students’ mental health challenges. For example, SilverCloud is a widely utilised online platform that provides structured CBT modules along with therapist support, which has been shown to alleviate depressive and anxiety symptoms in university students (Richards et al., 2020). Similarly, Beating the Blues is a computer-based intervention designed for self-guided CBT, with research demonstrating its effectiveness in reducing depressive symptoms (Proudfoot et al., 2011). There is some evidence that MoodGYM may be more effective in targeted interventions. Christensen et al. (2002) reported that for people with baseline levels of anxiety and depression who accessed MoodGYM, symptoms significantly decreased after programme completion. Furthermore, at a four-month follow-up, Canadian university students at risk of depression randomly assigned to MoodGYM experienced a greater reduction in depressive symptoms and were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with major depressive disorder than attentional control (McDermott and Dozois, 2019). This study aims to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of MoodGYM for academically struggling Emirati students with symptoms of depression.

Objectives

The objectives of the present study were as follows:

-

To explore the acceptability and feasibility of using MoodGYM to improve academic achievement in university students with low moods and poor academic performance in the UAE.

-

To investigate the potential effectiveness of self-directed, internet-delivered cognitive–behavioural skills therapy (MoodGYM) in improving academic performance (GPA) and mood in university students with poor academic performance in the UAE.

-

To investigate the relationship between MoodGYM uptake and improvement in GPA postintervention.

We hypothesise that students using MoodGYM will have a higher GPA at follow-up than the control group of students not using MoodGYM.

Methods

Design

This study used a pre–post pilot, nonrandomised trial design with a historical control group to evaluate changes in GPA. Data were collected via online surveys administered at baseline and follow-up two months after using MoodGYM.

Participants and recruitment

The participants were undergraduate students aged 18 years and above at a public university in the UAE. Students were selected from two campuses (Dubai and Abu-Dhabi) and recruited through their academic advisors. The recruitment target was 50 participants.

The target sample size was 50 male and female undergraduate students who met the following inclusion criteria:

-

Undergraduate students in their second, third, or fourth year of study at a university in the UAE.

-

Scheduled to attend an academic advisory seminar to address poor academic performance (GPA less than 2.0).

-

18 years of age or older.

-

Self-identified as having at least one of two key symptoms of low mood (Kroenke et al., 2009).

Historical control group

Students from a previous longitudinal cohort study of UAE university students (Awadalla et al., 2020) were selected as the comparison group if they had a GPA <2.0 at baseline and a GPA reported at the two-month follow-up. The control group of students (n = 19) had similar GPAs, attendance warnings, and demographic characteristics at baseline as the intervention group (n = 44). This group (no intervention) was used as a comparison group to evaluate academic improvement in the group receiving the intervention.

Power calculation

With a historical control group of n = 19 and assuming a 70% response rate at follow-up in the intervention group (35/50), it was estimated that the study would have 90% power to detect a 1 SD difference (d = 1) in GPA between groups at follow-up, with a probability of a type 1 error <0.05 (Faul et al., 2007).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Division of Psychiatry and Applied Psychology Ethics Subcommittee (reference number: 0397) and the Research Ethics Committee at Zayed University (ref ZU19_46_F). Participation was voluntary. The students completed an online written consent form to participate in the two anonymous online surveys. These surveys were linked through self-generated identifiers.

Measures

Mental health

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a self-assessment tool developed to detect states of depression and anxiety in nonpsychiatric settings (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983). The HADS comprises 14 items, with seven assessing anxiety (HADS-A) and seven assessing depression (HADS-D). For both subscales, scores of ≤7 indicate noncases, whereas scores of 8–10, 11−14, and 15−21 indicate mild, moderate, and severe depression and anxiety, respectively (Stern, 2014). Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.68 to 0.93 (mean = 0.83) for the HADS-A and from 0.67 to 0.90 (mean = 0.82) for the HADS-D (Bjelland et al., 2002). For anxiety and depression, the optimal cut-off values are HADS-A ≥8 (sensitivity 0.89, specificity 0.78) and HADS-D ≥8 (sensitivity 0.83 and specificity 0.79), respectively (Bjelland et al., 2002). The HADS has been validated in many languages, countries, and settings, including with university students (Andrews et al., 2006). An Arabic version of the HADS has been validated in Saudi Arabia (El-Rufaie and Absood, 1987), Kuwait (Malasi et al., 1991), and the UAE (El-Rufaie and Absood, 1995) in primary-care settings and, recently, among hospitalised patients (Terkawi et al., 2017).

Because all courses at the university are taught in English and the students are proficient in the English language, the HADS was provided in English. There were no missing HADS values, and the alpha values for the HADS-D (α = 0.61) and HADS-A (α = 0.77) indicated acceptable internal consistency.

Academic performance

The participants reported their most recent GPA, and the number of poor attendance academic warnings received during the previous semester. The GPA scores range from 04, with higher scores indicating better academic performance. In the present study, a GPA less than 2.0 was considered a sign of academic difficulty.

Intervention

MoodGYM is an internet-based CBT programme designed to prevent depression and teach coping skills and can be provided with or without clinician guidance. It was developed by researchers at the Australian National University in 2013 (www.moodgym.anu.edu.au). In this study, MoodGYM was entirely self-directed. The programme teaches key components of CBT for depression in five modules—feelings, thoughts, unwrapping, destressing, and relationships—as shown in Table 1. Each module contains exercises to be completed during the module, homework to be completed during the week, and a workbook to record progress throughout the programme. The modules are completed sequentially, with each estimated to take 30–45 min to complete and a total of 28 exercises and 13 across all modules (Christensen et al., 2004).

Procedure

Academic advisors send invitation emails and participant information sheets to all academically failing students, explaining the study to those students scheduled to attend a seminar addressing their poor academic performance in the previous semester (GPA <2.0). Students who reported feeling down, depressed, or hopeless, or who had little interest or pleasure in doing things in the previous 2 weeks, were invited to participate in the study by emailing the researcher. The academic advisor reminded students about the study invitation during the scheduled remedial class. All participants who contacted the researcher within the study timeframe (September 2019) were sent the baseline survey link. All parts of this study were conducted online, and data at baseline and 8-week follow-up were collected via anonymous surveys hosted by the Joint Information Systems Committee Online Surveys (JISC). The students were able to reread the participant information sheet before completing the online consent form. The participants created a unique study ID code by providing their birthday and the last three digits of their mobile phone number, which was used to link baseline and follow-up data. The participants then completed the baseline survey, which included demographic information, GPA, number of attendance warnings in the previous semester, previously seeking help for mental health problems, and the HADS. At the end of the survey, the students were thanked for their time and asked to click on a second survey link, which allowed them to enter their email address to receive a link and user code for MoodGYM. They were also provided with information about the University Counselling Centre for further support. The researcher sent an email with instructions and a user code for accessing MoodGYM to those who provided their emails. All participants received a reminder about using MoodGYM four weeks after entering the study. Eight weeks after the baseline survey, they were emailed a link to the follow-up survey, which collected data on their GPA, number of attendance warnings in the current semester, and the HADS. The follow-up survey also included text boxes to allow participants to comment on the positive and negative aspects of MoodGYM. A reminder email was sent to all participants two weeks after the follow-up survey email.

Data analysis

Data from the baseline and follow-up surveys were imported into SPSS (version 26). After the data were cleaned and checked, HADS and GPA scores were compared pre- and postintervention via appropriate paired statistics. Univariate correlations and regression analyses were used to explore the relationship between self-reported MoodGYM use and changes in GPA. A repeated-measures ANOVA with group (historical control/intervention) as the independent factor, time of testing as the within-subjects factor, and GPA score as the dependent variable was conducted to analyse group-by-time interactions. Descriptive statistics were used to explore the acceptability and usability of MoodGYM. Content analysis was used to classify and group participants’ responses to the open-ended question for evaluating MoodGYM.

Results

Fifty respondents (36 women and 14 men) completed the baseline survey and received access to the MoodGYM programme. Among the 50 students, 47 accessed the programme, and 44 completed the postintervention survey, forming the study sample (88.0% follow-up). The mean age was 20.7 years (SD = 1.55; range 18–24), and the majority were women (72%) (Table 2). At baseline, there were no detectable differences in demographic characteristics, baseline GPA, depressive symptoms, or the number of attendance warnings between respondents (intervention group, n = 44) and nonresponders at follow-up (n = 6) or between the intervention group respondents at follow-up and the historical control group (n = 19) (all p = >0.05). However, nonrespondents were significantly more anxious than respondents at baseline (M = 11.00, SD = 3.63, n = 6, vs. M = 7.61, SD = 2.57, n = 44, p = 0.006, d = 1.2). There was no difference in baseline anxiety between the intervention and historical control groups.

Help-seeking

Before using MoodGYM, nearly half the students reported seeking help for their mental health from friends (n = 19, 43.2%), followed by internet sources (n = 11, 25.0%). Two participants (4.5%) sought help from family, four (9.1%) from university tutors, and only three (6.8%) from university counselling services. Five students (11.4%) had not sought any help with their mental health.

Depression and anxiety before and after MoodGYM

A paired-sample t test revealed a significant reduction in HADS-D (t (43) = 3.07, p = 0.004, d = 0.5) and HADS-A scores (t (43) = 5.67, p ≤ 0.001, d = 1.1) postintervention compared with baseline, indicating a significant reduction in depressive and anxiety symptoms (Table 3). The proportion of participants scoring above the cut-off for depression caseness decreased from 77.2 to 27.3% (n = 34 to n = 12; McNemar = p < 0.001), and for anxiety caseness, it decreased from 50 to 11.4% (n = 22 to n = 5; McNemar = p < 0.001).

Academic performance before and after MoodGYM

The preintervention student GPA ranged from 0.331.90, with a mean of 1.55 (SD = 0.32), and increased significantly postintervention (t (43) = −9.26, p ≤ 0.001, d = 1.3), indicating significant improvement in academic performance after using MoodGYM (Table 4). At baseline, all students in the intervention group had a GPA below 2.0, indicating academic weakness. After using MoodGYM, 19 (43.2%) students had a GPA of 2.0 or above, indicating they had moved out of the academic warning zone.

At baseline, half of the sample had received at least one attendance warning (n = 22, 50.0%); however, this number decreased by nearly half after using the MoodGYM programme (8-week intervention) (n = 11, 22.0%), with a significant reduction in the number of attendance warnings between pre- and postintervention (Z = −2.66, p = 0.008, d = 0.6) (Table 4).

Academic performance outcomes compared with those of the control group

At baseline, the intervention (n = 44) and comparison groups (n = 19) had similar GPAs and number of attendance warnings. A repeated-measures ANOVA with group (intervention/historical control) as the between-subjects factor and time found a significant time-by-group interaction (F = 5.96, df = 1.61, p = 0.018). At follow-up, students in the intervention group had significantly higher GPAs than those in the historical control group (t (61) = 2.22, p = 0.030, d = 0.6) and fewer attendance warnings (Z = −2.10, p = 0.036, d = 0.7) (Table 4).

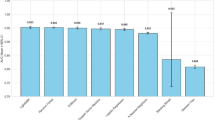

Completed MoodGYM modules and outcome improvements

All the students in the intervention group reported completing at least two modules, with nearly half reporting completing all five modules (mean number of completed modules = 3.75, SD = 1.52, n = 44). Almost all participants completed the feelings module (n = 42, 95.5%), followed by thoughts (36, 81.8%), unwrapping (34, 77.3%), destressing (29, 65.0%), and relationships (24, 54.0%). A significant positive correlation was found between GPA improvement and the number of modules completed (rs = 0.388, n = 44, p = 0.009). Completing more modules was also associated with a greater reduction in anxiety scores (rs = 0.348, n = 44, p = 0.020); however, no relationship was found between changes in depression scores and the number of completed modules.

Regression analysis (entry method) with the difference between pre- and postintervention GPAs as the dependent variable (higher scores indicating a greater GPA improvement) and baseline anxiety and depression scores, completed MoodGYM modules, and improved attendance as the independent variables revealed that a more significant GPA improvement was associated with completing more MoodGYM modules (β = 0.392, p = 0.005) and improved attendance (β = 0.388, p = 0.007; total adjusted r2 = 0.35) (Table 5).

Evaluation of MoodGYM

The participants used MoodGYM for 2– 8 weeks; however, the highest proportion of students used the programme for more than 4 weeks (n = 16, 36.4%) (Table 6).

The participant ratings of MoodGYM were generally either overwhelmingly positive or neutral. Most students (n = 31, 70.5%) rated MoodGYM as good or very good, and 35 (79.6%) reported that it was very or slightly helpful. More than half (n = 26, 59.1%) found MoodGYM easy or very easy to use, and 33 (75.0%) stated they would recommend it to a friend or family member.

The students were asked an open-ended question about how MoodGYM was helpful to them, and 70.5% (n = 31) responded. Content analysis revealed that 20 (45.5%).

students found that MoodGYM helped reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms by teaching them different coping skills and strategies to address their negative thoughts. Among the 20 students, four mentioned that the programme helped them reflect on themselves more by completing different exercises and conducting self-assessments at the end of each module; five stated that MoodGYM increased their knowledge of mental health; one suggested it was an excellent tool to address self-criticism; and ten indicated that MoodGYM helped them acquire new self-help techniques and strategies to address their negative thoughts and change their daily routines by implementing some of the exercises. For example, one student stated, ‘MoodGYM helped me to deal with my worrying thoughts and to understand why I get them very often’.

Eight (18.2%) students found MoodGYM helpful but felt that the modules were too long and time-consuming, while two (4.6%) felt that MoodGYM was unhelpful because of its lack of clarity and complexity. For example, one student could not understand the purpose of some assessments, stating, ‘In all, I do not think it was clear enough’.

Discussion

In the present study, students with poor academic achievement who self-reported symptoms of low mood demonstrated significant improvements in GPA (d = 1.3) and attendance (d = 0.6) after using the online CBT-based intervention MoodGYM. A comparison with a previous cohort of students with low GPAs revealed a significant time-by-group interaction, with the MoodGYM group having very similar GPA scores to the historical control group at baseline but significantly higher GPA scores at the equivalent follow-up point. Compared with that of the control group, the adherence of the experimental group also improved. GPA improvement was independently predicted by MoodGYM usage and improved attendance. MoodGYM was also associated with significant reductions in depressive and anxiety symptoms, and there were substantial reductions in the proportion of students scoring above the cut-off for anxiety and depression. Most participants positively evaluated MoodGYM and said they would recommend the programme to friends or family members.

Although this study lacked a control group for evaluating the substantial improvement in depressive and anxiety symptoms, the findings align with previous research using the MoodGYM programme with student populations. A study comparing MoodGYM with the school’s standard development activities for female secondary school students (n = 157) reported that MoodGYM usage significantly decreased the rate of self‐reported depressive symptoms compared with the usual curriculum and that the effect of MoodGYM was more significant after 20 weeks (O’Kearney et al., 2009). A recent study compared MoodGYM to two other internet-based preventive activities, attentional bias modification and an active attentional condition, in the prevention and treatment of major depressive disorder among high-risk first- and second-year university students (McDermott and Dozois, 2019). Depressive symptoms were assessed at three points, baseline, postintervention, and four-month follow-up, using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) depression scale and the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II). The results indicated that MoodGYM was a more effective intervention at the diagnostic and symptom levels, with effect sizes for changes in the BDI-II and DASS-21 depression scales of d = 0.40 and 0.51, respectively, at the 4-month follow-up. These effects were similar to the effect size (d = 0.5) for the change in the HADS-D score observed in the current study at 8 weeks postintervention. Conversely, Twomey et al. (2014) reported no significant improvements in anxiety or depressive symptoms in a clinical sample group with reported mental health issues using MoodGYM compared with a waitlist control group, despite showing some decrease in general psychological distress. However, the mean age of 35 years in the intervention group was substantially older than that in the present sample, and the follow-up rate was only 18%.

In the present sample, 70.5% (n = 31) considered MoodGYM an effective programme for reducing depressive and anxiety symptoms and felt that it enhanced their knowledge of mental health. This finding is consistent with a study by Farrer et al. (2012), which found that CBT interventions can effectively reduce depressive symptoms and promote knowledge about effective strategies for dealing with depression and self-management. Lintvedt et al. (2013) reported that an unguided intervention (MoodGYM) effectively improved depressive symptoms and negative automatic thoughts in a university population. The study had a high dropout rate (62% of the participants responded postintervention). In their study of university students experiencing depressive symptoms, they also reported that participants who used the MoodGYM programme were very satisfied and that 90% stated they would recommend the programme to others.

The results of the present study indicate a significant improvement in academic performance and a significant reduction in attendance warnings after using MoodGYM. To our knowledge, this is the first study that explores the potential of a CBT-based online intervention for improving academic outcomes. However, previous studies on different online interventions have reported some improvements in academic achievement. For example, Viskovich and Pakenham (2020) explored the effectiveness of web-based acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) in promoting mental health in university students and reported pre- to postintervention improvements in the study’s primary outcomes—including academic performance—which were maintained throughout the follow-up period. The study used a four-week web-based ACT mental health promotion intervention called ‘YOLO’. Academic performance was measured using a brief, 12-item self-report scale measuring facets of academic performance, including study habits, study motivation, and overall grades. It was unknown which items contributed to the score, as the study used a factor analysis method; however, the results indicated that the intervention improved participants’ perceived performance, although objective performance was not assessed.

In the present sample, the comparison group (n = 19) was from a recent cohort study conducted by Awadalla et al. (2020) that explored the effects of depression and anxiety on academic performance among university students. Essentially, the historical control group was from the same sample population as the current study (i.e., the same university and very similar sample characteristics). Like the intervention group, the students in this group had GPAs below 2.0 at recruitment and were considered to be in the academic warning (failing) category. Compared with the intervention group (n = 44), they had similar GPAs and attendance warnings at baseline; however, the comparison group (no intervention) had significantly lower GPAs and more attendance warnings at follow-up, demonstrating that the intervention group had better academic outcomes over a similar period.

There are many societal, attitudinal, and cultural reasons why university students with emotional difficulties may not seek professional help (Heath et al., 2016). The present study results demonstrate a gap in the proportion of students experiencing emotional difficulties and those who have sought professional help. For example, although 77% of the participants scored above the cut-off for depression caseness and nearly half of the intervention group had sought help from their friends, only three students had sought professional help.

These data are particularly valuable in highlighting the poor uptake of professional support, as there is a lack of data, including reliable records, for the number of people seeking mental health help in the UAE. Overall, the lack of awareness of the availability of mental health services and the stigma of seeking psychological help in the UAE may affect the help-seeking behaviour of several university students (Sayed, 2013). MoodGYM appears to offer an effective and acceptable method of increasing access to evidence-based therapies. The fact that 88% of the students responded to the postintervention survey shows that MoodGYM might be culturally and socially acceptable.

In this study, of the 47 students who accessed MoodGYM, half completed all five modules. The results indicated that the students who completed more MoodGYM modules performed better academically than those who completed fewer modules. These findings support the importance of the intervention dose. However, the bias of self-report measures and the need to assess the fidelity of MoodGYM use should also be considered. These findings are consistent with those of Calear et al. (2013), who investigated the effects of adolescent adherence to MoodGYM in schools. They reported that participants who maintained high intervention adherence reported greater intervention effects six months postintervention than those with low adherence. In their qualitative feasibility study, Ncheka et al. (2024) examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the feasibility of implementing MoodGYM among Zambian university students experiencing symptoms of low mood. The findings indicate that the MoodGYM programme contributed to enhanced academic resilience, with approximately a quarter of the participants attributing their academic improvement to using the programme. Additionally, MoodGYM supported students in maintaining social relationships, fostering a better understanding of negative thought patterns, and enhancing their overall mental well-being.

In the present study, more than half (59.1%) of the students found MoodGYM easy to use, and three-quarters of the students would recommend it to a family member or friend. This finding is consistent with another study that evaluated MoodGYM in primary-care patients with mild to moderate depression. The study reported that MoodGYM was rated positively by more than half of the participants and suggested that low nonadherence rates were a sign of positive evaluation, indicating the intervention’s acceptability (Høifødt et al., 2013). The study concluded that significant improvements were found at the 2-month follow-up. Additionally, the level of satisfaction among the participants was high, as 90% reported that they would recommend MoodGYM to others.

Although most students in the present study found MoodGYM helpful and easy to access, some found the modules very long and time-consuming. These students may require additional therapy support. A systematic review by Knowles et al. (2014) investigated qualitative studies exploring user experience with web-based therapies for anxiety and depression. Of the eight included studies, six used CBT and were found to be more concerned with improving access to therapy than with the patient experience. The review suggested that considering the sensitivity and personalisation of the programme’s content to be more relevant to users could increase engagement and adherence. Furthermore, Neil et al. (2009) proposed that internet-based interventions should precisely record user activity to measure adherence accurately. Estimating the time spent on modules is important, given that a user could also spend considerable time reading the modules but not completing the exercises, and yet still display some benefits from the programme.

Educational implications

The findings of this study suggest that online CBT-based interventions, such as MoodGYM, can play a valuable role in supporting students facing academic challenges and mental health difficulties. The notable increases in GPA and attendance among MoodGYM users show that participating in MoodGYM helps alleviate mental health problems, which improves academic performance. This highlights the importance of integrating mental health support into academic institutions as a means of fostering student success (Auerbach et al., 2016; Viskovich and Pakenham, 2020). Additionally, the study’s findings reinforce the need for academic institutions to recognise the link between mental health and learning outcomes. Structured mental health programmes allow colleges to assist students in developing resilience, coping mechanisms, and emotional control skills—qualities necessary for academic performance and personal development (Richardson et al., 2012).

Strengths and limitations of the study

To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluates an online CBT-based intervention to support students in the UAE experiencing low mood and academic difficulties. The study used a pre- and postintervention design, which can be valuable for providing preliminary evidence for intervention effectiveness. The fact that 88% of the students responded to the postintervention survey indicates the credibility of the study and its subsequent results. Furthermore, the scale used in this study for anxiety and depression (HADS) has been validated and shows good sensitivity and specificity. The HADS questionnaire has been validated in many languages, countries, and settings, including in the UAE (O’Kearney et al., 2009). Another strength of this study was the use of a historical control group for GPAs recruited from the same university, which showed data at the same time points during the previous year. The results of this pilot study constitute an important step towards further longitudinal studies that explore the effectiveness of online interventions in improving academic progress for university students with mental health issues.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. Owing to the small sample size and short follow-up period, the results reflect only a short ‘window of time’ and a limited university population. Thus, with more students and an extended follow-up period, the results might be more accurate and less biased, thereby providing more reliable estimates of the intervention’s benefits. Other limitations are that this study was not a randomised trial, had no control group for depressive and anxiety symptoms, and used self-reported GPAs. Another notable limitation is that some students found the MoodGYM modules to be lengthy, which may have affected adherence rates. Future studies should consider providing more time for module completion and adapting the intervention to enhance engagement by scheduling it during periods when students are less busy, ensuring better participation and retention. Finally, the qualitative data to support the quantitative findings are limited, and the bias from being in a study and the expectation of completing the survey can produce inauthentic answers.

Conclusions

The results indicate that MoodGYM is a convenient, acceptable, and effective therapeutic intervention when targeted at academically struggling students experiencing low mood. The observed improvements in mood, GPA, and attendance suggest that MoodGYM may be a cost-effective way to overcome obstacles to mental health support for academically struggling students. However, more research is needed to explore whether improvements are sustained and how MoodGYM can be best implemented within the curriculum.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Abu Ruz ME, Al-Akash HY, Jarrah S (2018) Persistent (anxiety and depression) affected academic achievement and absenteeism in nursing students. Open Nurs J 12:171–179

Al-Darmaki FR (2003) Attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help: what really counts for United Arab Emirates University students? Soc Behav Pers Int J 31(5):497–508

Al-Gelban KS (2009) Depression, anxiety and stress among Saudi adolescent school boys. J R Soc Promot Health 127(1):33–37

Anderson JK, Howarth E, Vainre M, Jones PB, Humphrey A (2017) A scoping literature review of service-level barriers for access and engagement with mental health services for children and young people. Child Youth Serv. Rev 77:164–176

Andrews B, Hejdenberg J, Wilding J (2006) Student anxiety and depression: comparison of questionnaire and interview assessments. J Affect Disord 95(1-3):29–34

Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R et al. (2016) WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 127(7):985–999

Awadalla S, Davies EB, Glazebrook C (2020) A longitudinal cohort study to explore the relationship between depression, anxiety and academic performance among Emirati university students. BMC Psychiatry 20(1):448

Barrable A, Papadatou-Pastou M, Tzotzoli P (2018) Supporting mental health, wellbeing and study skills in higher education: an online intervention system. Int J Ment Health Syst 12:54

Beiter R, Nash R, McCrady M, Rhoades D, Linscomb M, Clarahan M, Sammut S (2015) The prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and stress in a sample of college students. J Affect Disord 173:90–96

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52(2):69–77

Bolinski F, Boumparis N, Kleiboer A, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Riper H (2020) The effect of e-mental health interventions on academic performance in university and college students: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Internet Inter 20:100321

Calear AL, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM (2013) Adherence to the MoodGYM program: outcomes and predictors for an adolescent school-based population. J Affect Disord. 147(1-3):338–344

Christensen H, Griffiths K, Groves C, Korten A (2006) Free range users and one hit wonders: community users of an Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy program. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 40(1):59–62

Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF (2004) Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 328(7434):265

Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Korten A (2002) Web-based cognitive behavior therapy: analysis of site usage and changes in depression and anxiety scores. J Med Internet Res 4(1):e3

Conley CS, Travers LV, Bryant FB (2014) Promoting psychosocial adjustment and stress management in first-year college students: the role of resilience and coping. J Am Coll Health 63(2):92–101

Dardas LA, Simmons LA (2015) The stigma of mental illness in Arab families: a concept analysis. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 22(9):668–679

Davies EB, Morriss R, Glazebrook C (2014) Computer-delivered and web-based interventions to improve depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being of university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 16(5):e130

Deroma VM, Leach JB, Leverett JP (2009) The relationship between depression and college academic performance. Coll Stud J 43(2):325–335

Eapen V, Ghubash R, Sabri S (2021) Mental health problems among university students in the UAE. Asian J Psychiatry 56:102545

El-Rufaie OEF, Absood GH (1995) Retesting the validity of the Arabic version of the hospital anxiety and depression (HAD) scale in primary health care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 30(1):26–31

El-Rufaie OEFA, Absood G (1987) Validity study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale among a group of Saudi patients. Br J Psychiatry 151(5):687–688

Farrer L, Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Mackinnon A (2012) Web-based cognitive behavior therapy for depression with and without telephone tracking in a national helpline: secondary outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 14(3):e68

Farrer L, Gulliver A, Chan JKY, Batterham PJ, Reynolds J, Calear A, Tait R, Bennett K, Griffiths KM (2013) Technology-based interventions for mental health in tertiary students: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 15(5):e101

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39(2):175–191

Gaudiano BA (2008) Cognitive-behavioural therapies: achievements and challenges. Evid Based Ment Health 11(1):5–7

Gratzer D, Khalid-Khan F (2016) Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of psychiatric illness. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J 188(4):263–272

Grist R, Croker A, Denne M, Stallard P (2019) Technology delivered interventions for depression and anxiety in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 22(2):147–171

Harrer M, Adam SH, Baumeister H, Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Auerbach RP, Kessler RC, Bruffaerts R, Berking M, Ebert DD (2018) Internet interventions for mental health in university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 28(2):e1759

Heath PJ, Vogel DL, Al-Darmaki FR (2016) Help-seeking attitudes of United Arab Emirates students. Couns Psychol. 44(3):331–352

Høifødt RS, Lillevoll KR, Griffiths KM, Wilsgaard T, Eisemann M, Waterloo K, Kolstrup N (2013) The clinical effectiveness of web-based cognitive behavioral therapy with face-to-face therapist support for depressed primary care patients: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 15(8):e153

Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C (2013) A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res 47(3):391–400

January J, Madhombiro M, Chipamaunga S, Ray S, Chingono A, Abas M (2018) Prevalence of depression and anxiety among undergraduate university students in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 7(1):57

Knowles SE, Toms G, Sanders C, Bee P, Lovell K, Rennick-Egglestone S, Coyle D, Kennedy CM, Littlewood E, Kessler D, Gilbody S, Bower P (2014) Qualitative meta-synthesis of user experience of computerised therapy for depression and anxiety. PLoS ONE 9(1):e84323

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B (2009) An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ–4. Psychosomatics 50(6):613–621

Lintvedt OK, Griffiths KM, Sørensen K, Østvik AR, Wang CEA, Eisemann M, Waterloo K (2013) Evaluating the effectiveness and efficacy of unguided internet‐based self‐help intervention for the prevention of depression: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Psychol Psychother 20(1):10–27

Lopez MA, Basco MA (2015) Effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy in public mental health: comparison to treatment as usual for treatment-resistant depression. Adm Policy Ment Health 42(1):87–98

Malasi TH, Mirza IA, El‐Islam MF (1991) Validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in Arab patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 84(4):323–326

McDermott R, Dozois DJA (2019) A randomized controlled trial of Internet-delivered CBT and attention bias modification for early intervention of depression. J Exp Psychopathol 10(2):2043808719842502

Ncheka JM, Menon JA, Davies EB, Paul R, Mwaba SOC, Mudenda J, Wharrad H, Tak H, Glazebrook C (2024) Implementing internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (moodgym) for African students with symptoms of low mood during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative feasibility study. BMC Psychiatry 24(1):92

Neil AL, Batterham P, Christensen H, Bennett K, Griffiths KM (2009) Predictors of adherence by adolescents to a cognitive behavior therapy website in school and community-based settings. J Med Internet Res 11(1):e6

O’Kearney R, Kang K, Christensen H, Griffiths K (2009) A controlled trial of a school-based Internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depress Anxiety 26(1):65–72

Proudfoot J, Goldberg D, Mann A, Everitt B, Marks I, Gray JA (2011) Computerized, interactive, multimedia cognitive-behavioural program for anxiety and depression in general practice. Psychol Med 33(2):217–227

Richards D, Timulak L, Vigano N, O’Brien E, Doherty G, Sharry J, Hayes C (2020) A randomized controlled trial of an internet-delivered treatment: its impact on college students’ mental health. Internet Inter 19:100294

Richardson M, Abraham C, Bond R (2012) Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 138(2):353–387

Sayed MA (2013) Mental health services in the United Arab Emirates: challenges and opportunities. Int J Emerg. Ment Health Hum Resil 17(3):661–663

Stern AF (2014) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup Med 64(5):393–394

Sweetland AC, Oquendo MA, Sidat M, Santos PF, Vermund SH, Duarte CS, Arbuckle M, Wainberg ML (2014) Closing the mental health gap in low-income settings by building research capacity: perspectives from Mozambique. Ann Glob Health 80(2):126–133

Terkawi AS, Tsang S, AlKahtani GJ, Al-Mousa SH, Al Musaed S, AlZoraigi US, Alasfar EM, Doais KS, Abdulrahman A, Altirkawi KA (2017) Development and validation of Arabic version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Saudi J Anaesth 11(Suppl 1):S11–S18

Twomey C, O’Reilly G, Byrne M, Bury M, White A, Kissane S, McMahon A, Clancy N (2014) A randomized controlled trial of the computerized CBT programme, MoodGYM, for public mental health service users waiting for interventions. Br J Clin Psychol 53(4):433–450

Twomey C, O’Reilly G (2016) Meta-analysis looks at effectiveness of MoodGYM programme in computerised cognitive behavioural therapy. BMJ 354:i4221

Viskovich S, Pakenham KI (2020) Randomized controlled trial of a web‐based acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) program to promote mental health in university students. J Clin Psychol 76(6):929–951

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SA, CG, and EBD designed the study protocol and surveys. SA analysed the data under CG’s supervision. SA prepared the first draft of the paper and CG and EBD reviewed the subsequent drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Name of the approval body: Research Ethics Committee at Zayed University. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Research Ethics Committee at Zayed University and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Approval number or ID: (ZU19_46_F). Date of approval: May 13, 2019. Scope of approval: Participants were undergraduate students aged 18 and older at a public university in the UAE.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The participants were informed of the following: the purpose and nature of the study the procedures involved their right to withdraw at any time without penalty the confidentiality of their responses how their data would be stored, used, and protected (e.g., anonymized, stored securely, used only for research purposes) the potential risks and benefits of participating in the study contact information for the research team and ethics committee in case of any concerns. Consent was obtained in written form on September 10, 2019, and participants were provided with a copy of the consent form for their records.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Awadalla, S., Davies, E.B. & Glazebrook, C. A pre–post study evaluating an online CBT-based intervention to improve academic performance in students with low mood. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 763 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05037-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05037-x