Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed significant constraints to healthcare professionals in accessing evidence-based and certified education. This has highlighted the need for massive open online courses (MOOCs), considering their flexibility in digital access and time management. This study aimed to assess the intention of healthcare professionals to use a MOOC in lifelong learning during a pandemic outbreak and its effectiveness in knowledge retention. A descriptive study was conducted involving 2629 participants enrolled in a COVID-19-related open-access MOOC who agreed to participate in this study. A validated questionnaire was applied to collect the data. Data were processed and analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The study revealed the existence of certified trainees and non-certified explorers. The MOOC was useful to the healthcare professionals’ lifelong training (mean of 4.4 in 5) and perceived ease of use (mean of 4.4 in 5), with most professionals intending to continue using lifelong training (mean of 4.4 in 5). Moreover, participants reported high levels of satisfaction (4.5 in 5). The analysis of the mean score of the initial and final assessment per participant showed statistically significant differences (t795 = 58.5; P < 0.001; d = 0.19), confirming the programme’s effectiveness in knowledge retention. Findings also reveal higher completion rates (32.2%) compared to the literature (~12%), emphasising the importance of implementing a learning experience tailored to reskilling based on practical, collaborative, and dynamic content. These study results underscore the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention of healthcare professionals to use MOOCs in lifelong learning and demonstrate their effectiveness in knowledge retention. Results emphasise the need for developing modular, practical, interactive, collaborative and immersive learning experiences to increase completion rates and meet the needs of professionals in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, declared by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in March 2020, has posed unparalleled challenges leading to a period of uncertainty alongside accelerated scientific advancements related to the disease, its treatment, and the lack of comprehensive information on the best available evidence for healthcare professionals (Goossens et al., 2021). In 2020, these professionals were confronted with the imperative to update their knowledge and training to guarantee the best quality and safety of their interventions. However, researchers and healthcare professionals had to overcome the lack of previous knowledge on how to manage these novel healthcare demands. Thus, as newly developed knowledge was made available, dissemination was fundamental to guarantee its effective application in patient treatment worldwide, prompting the introduction of digital lifelong learning courses designed with open and asynchronous properties and tailored to large audiences, such as Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), considered the ‘forefront of education’ (Li et al., 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with excessive workloads and confinement restrictions has drastically transformed healthcare professionals’ access to lifelong learning. As a result, digital technologies emerged as effective tools for knowledge dissemination, updating and upskilling. During the pandemic, healthcare professionals’ time constraints and the imperative to access evidence-based and certified education shifted their attention and interest to e-learning courses, such as MOOCs.

With the pandemic outbreak, the number of registered users and courses on these international platforms has grown exponentially, from 91 million users before the pandemic to 178 million (Shah, 2021). In parallel, the body of available evidence was also increasing before the pandemic (Liu et al., 2021), likely predicting the forthcoming events in the field of education and training amidst the pandemic.

In the healthcare area, the World Health Organization (WHO) made the ‘COVID-19 Vaccination’ MOOC available in the OpenWHO platform directed to healthcare professionals (Goldin et al., 2021). However, despite this initiative, there was a lack of advanced upskilling courses related to the diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

In this context, a group of tertiary education teachers and healthcare professionals in nursing, medicine, and allied health areas collectively developed new educational and simulation contents, addressing the need for specialised training and evidence-based curriculum for the diagnosis and treatment of the COVID-19 disease. This endeavour culminated in the creation of a single MOOC, presented in Portuguese, directed at clinical diagnosis and treatment.

This study aimed (i) to assess the intention of healthcare professionals to use a MOOC in lifelong learning during a pandemic outbreak by analysing the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use this massive course in continuing training; (ii) to assess knowledge retention by comparing knowledge before and after the course; and (iii) to analyse the characteristics of participants who did not request a certificate.

Literature review

The evidence about the integration of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) into educational and training processes in a pandemic context has primarily focused on five major dimensions related to (1) the motivations for digital transformation, particularly concerning the use of MOOCs, (2) the perceived benefits of integrating MOOCs into education and training, (3) the challenges and implementation strategies, (4) efficacy and perceived perception of massive learning, and (5) envisioning future developments of this technology and their impact on education and training.

Regarding the first dimension, literature is dedicated to adapting learning methodologies to the outbreak context and the need for digital resources for students and trainees’ reskilling and upskilling (Almufarreh and Arshad, 2023; Despujol et al., 2022). This dimension focuses on the transition to online learning, reflecting on adaptation and digital transformation in organisations and its relevance for academic continuity through MOOCs and other online learning courses (Arima et al., 2021; Mejia et al., 2020).

Regarding the second dimension, the literature emphasises academic, professional, and personal gains, reinforcing the role of MOOCs in promoting flexibility, internationalization, and ensuring academic continuity (Arima et al., 2021; Almufarreh and Arshad, 2023; Despujol et al., 2022).

When examining the challenges and implementation strategies, the third dimension, evidence shows the existence of technological barriers to MOOC implementation due to inadequate infrastructure and limited internet access in various global contexts, posing a significant challenge to digital learning in several regions (Amit et al., 2022; Mejia et al., 2020).

Regarding the fourth dimension, online learning efficacy and perception are addressed mainly at the level of perceived perceptions. Overall, students/trainees and teachers/trainers reported positive perceptions of MOOCs’ efficacy, expressing satisfaction with their learning experiences (Arima et al., 2021; Ceballos and Mexía, 2021; Jivet and Saunders-Smits, 2021).

Thus, beyond offering flexibility, MOOCs were perceived as significant contributors to career development and continuing education, particularly within the pandemic outbreak context (Almufarreh and Arshad, 2023).

In the context of online education, the fifth dimension emphasises the integration of MOOCs into the regular learning process, suggesting that institutions start integrating MOOCs and online learning strategies into their academic curricula, leveraging lessons learned during the pandemic (Despujol et al., 2022).

Lastly, evidence highlights MOOCs’ role in continuing professional development, emphasizing the importance of trainers and teachers’ continuous training in digital and pedagogical skills to maximize the benefits of MOOCs and online learning (Mejia et al., 2020).

However, the literature on the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use this type of course in the COVID-19 context remains less explored. Nevertheless, some studies focus on specific topics, evidencing two different dimensions: adoption and continuity and pedagogical and instructional quality.

Regarding adoption and continuity, the literature highlights the perceived usefulness of the contents addressed, ease of access and platform usage (Padilha et al., 2021; Daneji et al., 2018; Gómez Gómez and Munuera Gómez, 2021), the institutional reputation of the creators (Tella et al., 2021), and satisfaction with previous experiences and confirmation of expectations (Daneji et al., 2019) as key drivers for students and trainees’ engagement and completion of MOOCs.

Regarding the pedagogical and instructional quality, the curriculum and the programme layout are relevant for retention, perceived utility, motivation, and trainee experience, adding to other add-ons and tools for an immersive learning experience, along with intuitive and responsive design for the seamless digital experience of users (Chan et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2015).

Methodology

A descriptive study was carried out to assess the MOOC for perceived ease of use, usefulness, intention to use and effectiveness in knowledge retention in lifelong learning.

Study design

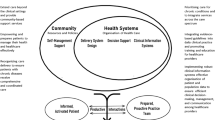

In the initial phase, a collaborative and interprofessional updating course aimed at healthcare professionals was developed on the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19. This process involved healthcare professionals from different areas and higher education teachers from an HEI, who jointly contributed to the design and development of the MOOC throughout all the development and assessment phases (Fig. 1).

The study was conducted in two phases: (1) Development of the COVID-19 MOOC, including interprofessional collaboration, design and development, and implementation; (2) MOOC assessment, focused on user acceptance (ease of use, usefulness, intention to use) and knowledge retention before and after course completion.

After the drawing of a catalogue of technical and pedagogical tools to be embedded in the e-learning platform based on educational needs and the thematic state of the art, the developed MOOC was designed based on a modular structure using video, text, and a virtual patient simulator, directed to the development of clinical decision-making skills.

This MOOC was structured into ten learning modules (Table 1). Each module fulfilled specific objectives materialized in lessons supported by text, multimedia documents, and a digital immersive simulation scenario for clinical reasoning training using virtual patients.

The MOOC offered 39 lessons with ~5 h of video content, each lasting an average of 7.5 min. Participants had an estimated workload of 35 h to complete this MOOC. Participants who completed the MOOC and achieved a minimum score of 70% on the final assessment were eligible to issue a certificate of completion.

Following a one-month period of beta-testing for usability, functionality, and performance assessment, the updating and validation of readiness the COVID-19 MOOC was made available between March and October 2021. It was hosted by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) on an OpenEDX open-source learning management system platform, supported by high-performance storage technology (CEPH), in full open-source. The second phase of the study aimed to assess the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use the MOOC for lifelong education and the participants’ level of knowledge.

At the end of the course, participants were surveyed about their perception of ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use this massive course in continuing training. Additionally, before starting and after completing the course, participants completed a questionnaire to assess their level of knowledge.

Sampling process

A non-probabilistic convenience sample of Portuguese healthcare professionals was used, with those voluntarily enrolled in the MOOC, made available in the OpenEDX open-source learning management system platform.

Of the 2629 participants enrolled in the MOOC between March and October 2021, 66.6% were female, and participants were aged, on average, 36.7 years (SD ± 11.5).

Data collection

In the data collection process, two questionnaires were applied: one to assess the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use a MOOC, and another with true-false questions to assess the initial and final level of knowledge.

The assessment questionnaire used for data collection was based on the ‘Davis Technology Acceptance Model’ (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh and Davis, 1996) and the ‘Determinants of Perceived Ease of Use’ of Venkatesh (2000).

The ‘Davis Technology Acceptance Model’ offers a framework for evaluating the use of information systems based on three main variables: perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use the technology. Additionally, the quality and satisfaction with the MOOC experience were also assessed.

The ‘Determinants of Perceived Ease of Use’ focuses on the perceived ease of use and behaviour towards technology, proposing a theoretical model based on self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, and emotional dimensions to understand the individual’s perceptions of ease of use of a system.

Based on these premises and dimensions, the questionnaire used in this study has been previously validated by other published studies (Padilha et al., 2012; 2018; 2020; 2021). The questionnaire was organised into two sections: the first section addressed the sociodemographic characterization, and the second section included 12 items (Table 2). Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (worst possible opinion) to 5 (best possible opinion).

The questionnaire assessing the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and intention to use this type of resource in lifelong training reached a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient value of 0.96 (n = 12 items) and item-total correlations ranging between 0.54 and 0.81.

A questionnaire with a set of 31 true or false questions was delivered to assess the level of knowledge. These questions were identified by the developers of MOOC content and were based on the best available evidence.

Data was collected by automated processes within the platform and exported in CSV format for subsequent normalization and redundancies elimination. The collected data encompassed sociodemographic characteristics, issuance of certificates, completeness, and initial and final questionnaire results.

Data analysis

Content validity was established by the research team. Following data collection, the second part of the questionnaire was tested for reliability by analysing internal consistency using exploratory factorial analysis and Cronbach’s Alpha. Student’s t-test was utilised for inferential analysis of the variables under study. Data analysis was performed by IBM SPSS Statistics – v.27 (IBM, 2020). Results are reported following the APA standards, indicating effect size measurements of the Cohen’s d (0.2 low; 0.5 medium, and 0.8 high) and considering a significance level of P < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

Authorization was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Nursing School of Porto with the reference ADHOC_907/2021.

Results

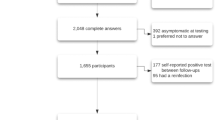

In this study, of the 2629 participants enrolled in the MOOC, 32.2% (n = 847) completed the course and issued a certificate. Of these, 97.9% (n = 830) completed the questionnaire assessing the dimensions ‘Ease of use’, ‘Usefulness’, and the ‘Intention to use’. Regarding the level of knowledge, 93.9% (n = 795) completed the initial and final assessment.

The sample included 847 certified individuals and 1782 (67.8%) who did not completed the course nor issued a certificate upon completion of the course.

Among non-certified and non-completers, a detailed characterisation by age, gender, profession, and academic qualifications was not feasible since 1527 participants did not answer these questions, corresponding to 85.7% of the participants without certification and those who did not complete the course. However, no statistically significant differences were found in the socio-demographic characterisation between certified and non-certified respondents who completed the questionnaire.

The average age of respondents was 36.9 years (SD ± 11.5), most were female (63.5%). Regarding academic background, 77.8% had stated their educational qualifications, with 60.4% (n = 502) holding at least a higher education degree (Bachelor's/Licentiate's, Master's, or Doctorate Degrees). Additionally, 18.1% of individuals interested in the MOOC subject were operative and technical health professionals.

Concerning the respondents’ professional characterisation, 64.7% had disclosed their occupation. Among the overall sample, 34.1% were nursing professionals, 19.8% were physicians and other health professionals with higher education degrees, and 3.8% were health students.

Table 3 shows the sociodemographic and professional characterization of the participants.

Evaluation of the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use this resource in lifelong training

Table 4 provides descriptive statistics on the assessment of the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use this type of resource in lifelong training.

The exploratory factor analysis (KMO = 0.96, Bartlett’s sphericity test = 0), using the principal components extraction method with Varimax rotation and Kaiser criteria for the extraction of the components that explain the maximum variance, allowed identifying a factor explaining 69.4% of data variance, which aggregates all 12 items.

In the evaluation of the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use this type of resource in lifelong training in the future and satisfaction with the course, global average values of 4.4 (SD ± 0.7) were observed, consistent with the score attained by participants ineligible for a certificate (4.3 SD ± 0.75). Inferential analysis of the data did not reveal any other statistically significant relationships between the variables under analysis for participants who completed the course and were issued a certificate.

In addition to assessing the perceived ease of use, usefulness, the intention to use, and satisfaction, other dimensions were assessed related to the learning experience (‘Content quality’, ‘Adequacy to the needs’, ‘Learning’ and ‘Overall assessment’) and the e-learning relevance and impact (‘E-learning relevance’, ‘E-learning professional updating’, ‘E-learning vs face-to-face’, and ‘Recommends the course to another person’). In these two groups, the overall values were also high, 4.3 (SD ± 0.7) for the learning experience evaluation category and 4.5 (SD ± 0.7) for the e-learning relevance and impact group.

Knowledge retention

Of the certified participants, 93.9% (n = 795) completed an initial knowledge assessment questionnaire, reaching an average score of 50% (SD ± 0.2; Max. = 84%; Min. = 0%). These participants obtained an average score of 88.8% (SD ± 0.9; Max. = 100%; Min. = 70) in all the evaluation tests of the course. The analysis of the average score of the initial and final assessment, per participant, revealed statistically significant differences (t795 = 58.5; P < 0.001; d = 0.19), confirming the effectiveness of the programme for knowledge retention.

Analysis of the participants who did not issue a certificate

Of the 67.8% (n = 1782) participants that did not issue a certificate nor completed the course, 2.8% (n = 50) obtained an average assessment of 80.40% (SD = ± 8.5%; Max. = 100%; Min. = 70%), which ultimately would allow them to issue a certificate of completion.

Among these non-certified participants, 70% were women, 78% held a Master’s or Bachelor’s degree, and had a mean age of 36 years (SD = ± 11.15). Additionally, 54% of those participants were nurses, 20% worked in other non-related health professions, 10% were senior health technicians, and 2% were physicians. The remaining 14% of the non-certified participants did not specify their profession.

This group of participants scored overall mean values of 4.5 (SD ± 0.72) on the evaluation of the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use this type of resource in lifelong training in the future, indicating satisfaction with the programme.

Regarding the participants who did not meet the criteria to issue the MOOC certificate (65% of the sample), 10.4% (n = 185) reached an assessment between 50 and 69% and a mean of 61% (SD = ± 5.8%; Max. = 69%; Min. = 50%).

No statistically significant differences in age, training, and profession were found among non-certified participants compared to the participants eligible to issue the certificate of completion of the programme. In this group of participants, the evaluation of the dimensions perceived ease of use, usefulness, the intention to use, and satisfaction with the programme reached global average values of 4.3 (SD = ± 0.72).

Of the participants who did not issue a certificate, 86.9% (n = 1550) obtained a classification below 50%. Table 5 shows the distribution of assessments per module and the number of participants who completed each module of the training programme.

Discussion

This study encompasses two major areas of analysis. The first focuses on formal aspects, namely certification, dropout rates, completion rates, and their relationship with sociodemographic characterisation. The second addresses knowledge retention and related trainees’ perceptions.

Albeit the scattered evidence on completion rates, data produced within the pandemic context suggests a decrease in certification rates (Yee et al., 2022). The study presents a completion rate of 32.2%, surpassing the rates typically reported in the literature ~12% (Roy et al., 2022). This highlights the importance of integrating practical and interdisciplinary content into MOOC programmes, e.g., collaborative, to improve completion rates, as stated by Guest et al. (2021).

Notably, the high completion rate observed in this study can be attributed to the increased need perceived by healthcare professionals rather than by students, as indicated by the low representation of nursing and medical scholars compared to the overall professions stated in the sample. This suggests an organic completion rate rather than a biased one by integrating MOOCs into formal learning embedded within academic curricula (Cha and So, 2020).

Given that the results did not show statistically significant differences between the variables and the demographic and professional profiles of the participants, these study findings suggest other explanations for the use of MOOCs in the lifelong training of healthcare professionals.

The participants who did not issue a certificate despite meeting the criteria may have been primarily interested in acquiring information applicable to clinical practice rather than obtaining a certificate. These participants reported significant satisfaction levels with the programme and high overall mean values in the evaluation of the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use MOOCs in the future. Milligan and Littlejohn (2016) describe scenarios in which participants may attribute less emphasis on certification but remain engaged and complete their training based on personal indicators of success, demonstrating intrinsic motivation and the ability to self-regulate learning.

The diverse professional backgrounds and qualifications of this group of participants (nurses, physicians, and senior technicians) may explain this behavioural pattern. According to Zeng et al. (2015), this behaviour is presented in three of the four typified motivations for participating in a MOOC: meeting current needs, preparing for the future, and satisfying curiosity, all within the scope of a personal pursuit of knowledge.

Notably, participants with a greater capacity for self-regulation adopt a strategic approach and decide not to attend modules they consider less interesting because completing the course is not crucial for their success (Milligan and Littlejohn, 2016).

This evidence supported the existence of two major groups of participants in MOOCs: certificate achievers, those who issued a certificate, and explorers, those who did not issue a certificate, albeit meeting the criteria, as stated by Bowen et al. (2021).

In this sense, a self-directed learning behaviour emerges, aligning with Li's (2019) assertion that individuals with high qualifications, clear objectives, and a recognition of effective learning outcomes tend to report higher satisfaction levels with their learning journey. This finding is also corroborated by Alamri (2022), suggesting that MOOCs should adopt a learning-oriented structure and allow the assessment of acquired skills and competencies.

Participants who did not meet the conditions to issue a certificate illustrate the two groups of less productive participants, namely ‘Only registered’ and ‘Only viewed’ (Ho et al., 2014), accounting for 65% of all users.

These less prolific participants seem to struggle with meaningful self-regulation of their learning process. Despite regular engagement with the course material, they may find it too challenging and lack the ability or readiness to change their approach (Milligan and Littlejohn, 2016). These difficulties can be related to the complex network of internal factors (personal-psychological) and contextual factors (environmental) that interact in self-regulated learning (Littlejohn et al., 2015; Pintrich, 2020; Hendriks et al., 2020). Evidence suggests completion rates averaging below 10% (Huang et al., 2023).

The second dimension of analysis, related to knowledge retention, e.g., the effectiveness of the MOOC for upskilling or reskilling, is addressed by comparing the average completion score with the initial average score. This suggests a high level of active learners, as evidenced by a higher completion rate and improved course grades (Tseng et al., 2016) compared to the diagnostic assessment.

When assessing the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and the intention to use the MOOC for lifelong education in the future, the findings revealed high overall values (M = 4.4; SD ± 0.7) and similar values in satisfaction (M = 4.5; SD ± 0.7), in line with satisfaction levels evidenced in recent studies (Amit et al., 2022; Despujol et al., 2022; Gómez Gómez and Munuera Gómez, 2021; Martín-Valero et al., 2021; Yilmaz et al., 2021).

In this study, ‘Perceived ease of use’ scored higher, which is a crucial characteristic in the acceptance process of information technology (Davies, 1989), such as MOOC (Cabral et al., 2023). ‘Ease of use’ supports trainees, retention, and engagement with the content, ultimately influencing perceived usefulness (Kim and Song, 2022; Padilha et al., 2024).

Similarly, perceived usefulness is bidirected since it relates to improving both professional and knowledge retention. In sum, usefulness in MOOC context refers to the utility of these programmes to gaining or upgrading skills (Mohan et al., 2020), leading to greater satisfaction with the learning experience (Despujol et al., 2022).

The intention to use the knowledge addressed in the future also scored high. Evidence has shown the motivations for future intention to use (Kim and Song, 2022) with significant relation to the perceived need for reskilling, habitual engagement with technology, hedonic motivations, experimental value, and interest in digital self-learning (Mohan et al., 2020).

The context and the contents have encouraged trainees to reuse those contents in the future. The context of individual distancing and the challenges faced by health professionals in managing high workloads during this period prompted the use of digital technologies for training.

On the other hand, the content focused on the reskilling of professional abilities to combat the new disease, and the integration of an immersive simulator introduced elements of fun and amusement, typically of hedonic stimuli, along with the experimental value.

The dimension ‘Satisfaction’ scored the highest. Considering its critical role in trainees’ engagement, retention, and future use (Almufarreh and Arshad, 2023), it brings together a set of previous dimensions, driven by the ease of use of the platform, usefulness for reskilling, and intention to use in the future.

The dimensions addressed in the ‘learning experience evaluation’ and ‘e-learning relevance and impact’ groups reflected the overall quality and effectiveness perceived by trainees, further reinforcing the perceived satisfaction with their learning experience.

Limitations

The main limitations of this study were (1) the impossibility of making a prospective assessment of knowledge retention and (2) the participants’ inability to access the certificate by module, which would provide further data to assess the compelling interest in the modular contents provided.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the intention of healthcare professionals to use MOOCs in lifelong learning since they are easy to use and useful in keeping professionals updated on advances in medical areas and thus ensure the safety and quality of healthcare delivery.

This study brings significant contributions to the state of the art in two major dimensions: new contributions and the reinforcement of knowledge already acquired.

Regarding new contributions, the paper shows the effectiveness of this MOOC for the promotion of knowledge retention amid a pandemic, demonstrating significant differences between the scores of knowledge before and after the completion of the course’s modules (50% to 88.8%).

Additionally, despite the typically high dropout rates influenced by the difficulty of self-regulation of learning, this MOOC exhibited a notably higher completion rate compared to those reported in the literature. This highlights the importance of implementing a learning experience tailored to reskilling based on practical, collaborative, and dynamic content.

This study contributes to the existing literature by demonstrating that MOOCs developed collaboratively by higher education institutions and leading healthcare professionals in the field, designed with a modular, practical, and interactive approach, and incorporating immersive learning experiences such as virtual patient simulators, can enhance completion rates, learner satisfaction and knowledge retention.

Moreover, this study contributes to supporting existing knowledge since it unveiled significant levels of perceived usefulness and ease, reinforcing the importance of these courses for the continuous update of health professionals.

Furthermore, the findings underscore the high levels of satisfaction with the perceived ease of use, usefulness, and intention to use content; therefore, suggesting the crucial contribution of these dimensions to learners’ retention and engagement.

In sum, the findings demonstrate that MOOCs are useful in the lifelong training of health professionals and are easy to use. They also highlight the professionals’ intention to pursue this training in lifelong learning and its effectiveness for knowledge retention, irrespective of whether participants completed the entire course or only attended it partially. This may be explained by the fact that not all participants sought to obtain all the content available in the course, but only the topics of the lessons that were more relevant to them professionally.

In future similar programmes, it would be interesting to evaluate the opportunity and effectiveness of offering participants modules perceived as interesting. This approach could facilitate the creation of modular certificates since the flexibility of MOOCs may be particularly advantageous for participants with conscientious learning practices.

In the development of MOOCs for lifelong training of healthcare professionals, some recommendations based on the current findings are highlighted: courses should include a (1) modular structure using both (2) practical content and interactive resources, and (3) digital immersive simulators for development of clinical decision-making based on digital patients.

Additionally, (4) contents must be presented by leading professionals with different clinical backgrounds, (5) certified by institutions valued by participants, and (6) enabling professional and academic accreditation, namely in a micro-credential format.

The acceptance and success of the learning experience should be supported by the (7) easiness of use of the technological tool and by a (8) personalised experience considering the different participants´ motivations and interests, supported by (9) guided self-learning tools for supporting participant’s self-regulation during the course.

Data availability

Additional data files in Portuguese are available upon request to the corresponding authors.

References

Alamri MM (2022) Investigating students’ adoption of MOOCs during COVID-19 pandemic: students’ academic self-efficacy, learning engagement, and learning persistence. Sustain 14:714. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020714

Almufarreh A, Arshad M (2023) Exploratory students’ behavior towards massive open online courses: a structural equation modeling approach. Systems 11(5):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems11050223

Amit S, Karim R, Kafy A (2022) Mapping emerging massive open online course (MOOC) markets before and after COVID-19: a comparative perspective from Bangladesh and India. Spat Inf Res 30:655–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41324-022-00463-4

Arima et al. (2021) Re-design classroom into MOOC-like content with remote face-to-face sessions during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study in graduate school. In: L@S ‘21: Proceedings of the Eighth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale, Virtual Event, Germany, 22-25 June 2021. https://doi.org/10.1145/3430895.3460163

Bowen L et al. (2021) Exploring behavioural differences between certificate achievers and explorers in MOOCs. Asia Pac J Educ 42(4):802–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2020.1868974

Cabral PB et al. (2023) Case study of two higher education institutions in the use of a National MOOC platform toward sustainable development. In: Tavares F., Pitarma R., Zdravevski E. (eds) Digital transition in education and smart learning. CRC Press, Boca Raton, p 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003424543-12

Ceballos S, Mexía P (2021) MOOC’s benefits for higher education students during the academic emergency due to Covid-19. Prax Educ 16:e2118097. https://doi.org/10.5212/praxeduc.v.16.18097.072

Cha H, So HJ (2020) Integration of formal, non-formal and informal learning through MOOCs. In: Burgos D. (eds) Radical Solutions and Open Science. Lecture Notes in Educational Technology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4276-3_9

Chan M, et al. (2017) Perceived usefulness and motivation students towards the use of a cloud-based tool to support the learning process in a Java MOOC. 2017 International Conference MOOC-MAKER, 73-82

Daneji A, Ayub A, Jaafar W (2018) Influence of students’ perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and time spent towards students’ continuance intention using MOOC among public university students. In ICCE 2018 - 26th International Conference on Computers in Education, Workshop Proceedings, 576–581. https://doi.org/10.2991/icems-17.2018.50

Daneji A, Ayub A, Khambari M (2019) The effects of perceived usefulness, confirmation and satisfaction on continuance intention in using massive open online course (MOOC). Knowl Manag E-Learn 11(2):201–214. https://doi.org/10.34105/j.kmel.2019.11.010

Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 13(3):319–340. http://www.jstor.org/stable/249008

Despujol I, Castañeda L, Turró C (2022) What does the data say about effective university online internships? The Universitat Politècnica de València experience using MOOC during COVID-19 lockdown. Sustain 14(1):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010520

Goldin S et al. (2021) Learning from a massive open online COVID-19 vaccination training experience: survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 7(12):e33455. https://doi.org/10.2196/33455

Gómez Gómez F, Munuera Gómez P (2021) Use of MOOCs in health care training: a descriptive-exploratory case study in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain 13(19):10657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910657

Goossens H et al. (2021) European clinical research response to optimise treatment of patients with COVID-19: lessons learned, future perspective, and recommendations. Lancet Infec Dis 22(5):e153–e158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00705-2

Guest C et al. (2021) Driving quality improvement with a massive open online course (MOOC). BMJ Open Qual 10:e000781. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000781

Hendriks RA et al. (2020) Uncovering motivation and self-regulated learning skills in integrated medical MOOC learning: a mixed methods research protocol. BMJ Open 10:e038235. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038235

Ho AD et al. (2014) HarvardX and MITx: the first year of open online courses (HarvardX and MITx Working Paper No. 1). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2381263

Huang H, Jew L, Qi D (2023) Take a MOOC and then drop: a systematic review of MOOC engagement pattern and dropout factor. Heliyon 9(4):e15220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15220

IBM Corp (2020) IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 27) [Computer software]. IBM Corp, New York

Jivet I, Saunders-Smits G (2021) The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on a MOOC in Aerospace Structures and Materials. In Heiß HU, Järvinen HM, Mayer A et al. (eds.) Blended learning in engineering education: challenging, enlightening – and lasting? SEFI, Brussels, p 258–267

Kim R, Song HD (2022) Examining the influence of teaching presence and task-technology fit on continuance intention to use MOOCs. Asia Pac Edu Res 31:395–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00581-x

Li K (2019) MOOC learners’ demographics, self-regulated learning strategy, perceived learning and satisfaction: a structural equation modeling approach. Comput Educ 132(1):16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.003

Li L et al. (2022) Key factors in MOOC pedagogy based on NLP sentiment analysis of learner reviews: What makes a hit. Comput Educ 176:104354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104354

Littlejohn A et al. (2015) Learning in MOOCs: motivations and self-regulated learning in MOOCs. Internet High Educ 29:40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.12.003

Liu C et al. (2021) A bibliometric review on latent topics and trends of the empirical MOOC literature (2008–2019). Asia Pacific Educ Rev 22:515–534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-021-09692-y

Liu M, Kang J, McKelroy E (2015) Examining learners’ perspective of taking a MOOC: Reasons, excitement, and perception of usefulness. Educ Media Int 52(2):129–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2015.1053289

Martín-Valero R et al. (2021) The usefulness of a massive open online course about postural and technological adaptations to enhance academic performance and empathy in health sciences undergraduates. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(20):10672. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010672

Mejía K et al. (2020) Designing a MOOC to prepare faculty members to teach on virtual learning environments in the time of COVID-19. In: 2020 IEEE Learning With MOOCS (LWMOOCS), 30 Sept- 2 Oct 2020. IEEE, Antigua Guatemala, p 96–99, https://doi.org/10.1109/LWMOOCS50143.2020.9234381

Milligan C, Littlejohn A (2016) How health professionals regulate their learning in massive open online courses. Internet High Educ 31:113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2016.07.005

Mohan MM, Upadhyaya P, Pillai KR (2020) Intention and barriers to use MOOCs: An investigation among the postgraduate students in India. Educ Inf Technol 25:5017–5031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10215-2

Padilha JM et al. (2024) Clinical virtual simulation: predictors of user acceptance in nursing education. BMC Med Educ 24:299. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05154-2

Padilha JM et al. (2020) ECare-COPD – a massive open online course to empower nurses to promote self-management in COPD patients. Eur Respir J 56(Suppl 64):5172. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.congress-2020.5172

Padilha JM et al. (2018) Clinical virtual simulation in nursing education. Clin Simul Nurs 15(C):13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2017.09.005

Padilha JM et al. (2021) Easiness, usefulness and intention to use a MOOC in nursing. Nurse Educ Today 97:104705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104705

Padilha JM, Sousa P, Pereira F (2012) Analysis of use of technological support and information content by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Acta Paul Enferm 25(spe1):60–66. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-21002012000800010

Pintrich PR (2000) An achievement goal theory perspective on issues in motivation terminology, theory, and research. Contemp Educ Psychol 25(1):92–104. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1017

Roy et al. (2022) How COVID-19 affected computer science MOOC learner behavior and achievements: A demographic study. In: L@S'22 - Proceedings of the Ninth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale, 1–3 June 2022, Association of Computing Machinery, New York, p 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491140.3528328

Shah D (2021) A decade of MOOCs: A review of MOOC stats and trends in 2021. Retrieved from https://www.classcentral.com/report/moocs-stats-and-trends-2021/. Accessed 7 Apr 2025

Tella A et al. (2021) Perceived usefulness, reputation, and tutors’ advocate as predictors of MOOC utilization by distance learners: Implication on library services in distance learning in Eswatini. J Libr Inf Serv Distance Learn 15(1):41–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2020.1828218

Tseng SF et al. (2016) Who will pass? Analyzing learner behaviors in MOOCs. Res Pr Technol Enhanc Learn 11:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-016-0033-5

Venkatesh V (2000) Determinants of perceived ease of use: integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into in the technology acceptance model. Inf. Syst Res 11(4):342–365. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4062395

Venkatesh V, Davis FD (1996) A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: development and test. Decis Sci 27(3):451–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.1996.tb00860.x

Yee et al. (2022) The relationship between COVID-19 severity and computer science MOOC learner achievement: a preliminary analysis. In: L@S'22 - Proceedings of the Ninth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale, 1-3 June 2022, Association of Computing Machinery, New York, p 431–435. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491140.3528325

Yilmaz Y et al. (2021) RE-AIMing COVID-19 online learning for medical students: a massive open online course evaluation. BMC Med Educ 21:303. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02751-3

Zheng S et al. (2105) Understanding student motivation, behaviors and perceptions in MOOCs. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Association of Computing Machinery, Vancouver, p 1882-1895. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675217

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the editor and the reviewers for the valuable insights into the manuscript. The authors also wish to acknowledge the professional translator Maria do Amparo Alves in the editing of this article. This article was supported by National Funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within CINTESIS, R&D Unit (reference UIDB/4255/2020 and reference UIDP/4255/2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. JMP—conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, writing original draft and review and editing. CB—conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, writing original draft and review and editing. FV—conceptualization, methodology, project administration, writing original draft and review and editing. PM—conceptualization, methodology, project administration, review and editing. ALR—conceptualization, methodology, project administration and review and editing. PC— conceptualization, data curation, methodology, project administration, review and editing. MA—conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, writing original draft and review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Nursing School of Porto, the institutional body responsible for reviewing research involving human participants. All procedures involving human subjects were carried out in line with the ethical standards established by the committee, the relevant national regulations, and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Approval was formally granted on 16 July 2021, under the reference number ADHOC_907/2021. Importantly, while the questionnaire was made available earlier as part of the course’s pedagogical and evaluation components, this occurred in the context of the public health emergency caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which required the urgent deployment of the training programme to support healthcare professionals. No data were accessed, processed, or analysed for research purposes prior to receiving formal approval from the Ethics Committee of the Nursing School of Porto. The approval covered the analysis of anonymized data provided voluntarily by participants enrolled in a massive open online course (MOOC) on healthcare practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ethical review specifically assessed the validity of the informed consent process, the adequacy of data protection measures, and the non-interventional nature of the study. The committee granted approval with full knowledge of the data collection timeline and confirmed that all procedures conformed to the ethical standards required for research involving human participants. Following the ethics committee approval, all participants were recontacted and explicitly invited to confirm their authorization for the use of their responses in the context of the approved research study. This additional step reinforced the validity of the consent obtained and ensured continued adherence to the principles of autonomy and transparency.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants prior to data collection. The process took place between 1 March and 31 October 2021, during enrolment in the MOOC. Before accessing the questionnaire, participants were required to read an information sheet and actively confirm their agreement by selecting a checkbox on the online consent form. This step was mandatory and integrated into the course platform, ensuring that no responses were collected without prior consent. The process was overseen by the principal investigator at the Nursing School of Porto, and consent was obtained exclusively from adult participants who had voluntarily registered for the course. Participants were clearly informed, both in the consent form and again at the start of the questionnaire, that their survey responses would be processed anonymously. Identifiable data were not linked to the questionnaire at any stage, and the research team ensured that all responses were stored and analysed independently of personal information, thereby preserving full anonymity at the level of data analysis. Participants were also informed of the study’s aims, the voluntary nature of participation, the procedures involved, and the intended use of the data for research and publication. They were advised of their right to withdraw from the study at any point, without any disadvantage or penalty. Confidentiality was guaranteed, and all data handling was carried out in accordance with applicable data protection legislation. Following ethics committee approval, all participants were recontacted and invited to reaffirm their authorization for the inclusion of their responses in the ethically approved research. This additional step reinforced the transparency of the consent process and ensured continued respect for participants’ autonomy. Given the non-interventional nature of the study and the clear assurance of anonymity and voluntary participation, no risks were foreseen for those who took part. The procedures for obtaining consent were carried out in line with the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki, which highlights the participant’s right to be fully informed and to provide voluntary, informed consent prior to inclusion in any research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Padilha, J.M., Bastos, C., Vieira, F. et al. Perceived usefulness and effectiveness of a MOOC on healthcare during the pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 773 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05057-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05057-7