Abstract

India, a developing country heavily reliant on the agricultural sector, has witnessed the emergence of farmer producer organizations (FPOs) as a transformative collective model for farmers as an alternative to traditional cooperatives. The FPOs aim to solve the problems encountered by small and marginal farmers, especially those about better access to capital, technical improvements, and efficient inputs and markets. A comprehensive review of the literature in this field is essential because of the rapid advancement of FPO research articles. Scholars have published several review articles on FPO from different perspectives to tackle this issue. However, there is not a considerable number of published studies on FPO that incorporate bibliometric analysis. In the present study, an attempt is made to investigate the FPO publications with bibliometric analysis. This study employs a systematic literature review methodology, focusing on research published between 2002 and 2023. From an initial pool of 3796 research articles, 64 relevant studies from the Scopus database were identified for the study. These papers were analyzed using publication, journal, country, and author productivity, as well as the highest cited documents, co-citation analysis, bibliographic coupling analysis, and cluster analysis. The findings reveal that most studies focus on assessing the performance of FPOs, with limited attention to critical areas like institutional support, leadership, and policy execution. The cluster analysis results revealed that agricultural marketing, sustainable agriculture, the impact of membership on performance, women in agriculture, manufacturing, sustainability driving innovation, and technological efficiency of the food supply chain are the emerging themes in the literature. This paper provides policy recommendations on some significant challenges FPOs face, such as streamlining documentation, enhancing market access, ensuring fair tax treatment, allowing fertilizer distribution rights, and promoting farmer-led leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the current era, Agri-business is one of the fastest-growing industries. As per Provisional Estimates of National Income, 2022–23, released by the Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, during the last six years, the Indian agriculture and allied sector has been growing at 4.4% per annum. In addition, according to World Bank statistics from 2023, the agricultural sector, which accounts for 4% of global GDP and up to 25% in the least developed nations, is crucial to economic growth. Agriculture ultimately helps achieve sustainable development goals such as no poverty, zero hunger, good health and wellbeing, and decent economic growth.

However, despite agriculture playing a vital role in countries’ overall development, small and marginal farmers face various challenges in the agricultural sector, including climate change, inadequate financial support, ineffective marketing systems, and difficulties in securing a fair price for their produce. All these issues continue to limit agricultural productivity and farmer incomes and, therefore, require institutional mechanisms that empower farmers and improve their access to resources and markets.

In response to the challenges faced by small and marginal farmers, the Indian government has implemented several innovative initiatives. The main one is “Agricultural cooperatives,” which have long dominated farmer collectives and were founded by the Cooperative Credit Societies Act of 1904. However, the history of cooperatives exposes several barriers that prevent effective group action. In India, cooperatives did not have as much success due to their organizations’ weak administration and organizational internal corruption, financial problems, and political meddling (Abraham et al., 2022). Then, the Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) Act was modified in 2003. The APMC model is initiated to strengthen the marketing channels for farmers. However, it became an instrument for political traders’ or mediators’ monopolistic practices over time. This led to high marketing charges and poor market infrastructure. Excessive state control on APMCs discouraged free trade and private investment, creating long value chains and intermediaries (Saha et al., 2024). Since then, self-help groups, contract farming, and procurement sheds have all become widespread. However, these interventions did not fully deliver the expected benefits to farmers.

Recognizing the need for a more efficient collective model, the Indian government introduced a new kind of collective called FPO as an alternative to traditional cooperatives. The FPOs aim to solve the problems encountered by small and marginal farmers, especially those about better access to capital, technical improvements, and efficient inputs and markets (Bikkina et al., 2018; Government of India, 2013; Hellin et al., 2009). A key milestone in this effort was that the Government of India amended the Companies Act 1956 in 2002 by introducing section IX A, establishing producer companies managed by primary producers that would function similarly to corporate organizations, following the recommendations of the Y. K. Alagh Committee. Further, the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation published a policy paper in 2013 called “Policy and Process Guidelines for FPOs” to encourage the development of FPOs and to offer clear instructions for the establishment and administration of these organizations (Bikkina et al., 2018; Government of India, 2013).

FPOs are among the most critical constitutional reforms for farmers and rural people’s advancement, poverty alleviation, and empowerment (Nikam et al., 2019). While several FPOs were registered and operating effectively in their locality. Only a few have fully met their objectives (Bikkina et al., 2018). In recent years, several studies have examined different aspects of FPOs. The role of FPOs in facilitating smallholder farmers’ access to market, finance, and technology has been thoroughly studied in the literature (Singh & Sharma, 2021). Governance mechanisms (Patil & Meena, 2020), financial transaction sustainability (Reddy et al., 2021), and the impact of government policies on FPO promotion (Sharma & Rao, 2019) have been the research focus. Academic studies have also investigated the impact of FPOs on income generation and rural livelihood enhancement (Gupta & Verma, 2020).

Despite the increasing number of FPOs in India, their effectiveness in achieving their key goals, such as financial sustainability, market participation, and leadership, remains unclear. Earlier studies have explored different facets of FPOs, but there is a notable absence of comprehensive systematic reviews that integrate historical trends, current challenges, and future policy directions. This gap hinders a holistic understanding of FPO dynamics and the development of effective strategies for their sustainability. As a result, this study aims to offer a structured understanding of existing knowledge and emerging themes on FPO, analyzing status in terms of trends, gaps, thematic focus areas, challenges, and future directions. The study’s implications will offer a more practical perspective on public policies.

The paper is divided into various sections. Firstly, the literature on FPO sets the theoretical background of the research, with research questions followed by the methodology. Additionally, it continues with data collection and analysis procedures, followed by findings and results. Further, it elaborates on findings through discussion and discusses limitations and future research directions. Finally, the study sheds some light on policy implications and conclusions.

Literature review

FPO formation aims to mobilize farmers, strengthen capacity through agricultural best practices, ensure access to quality inputs and services, enhance cluster competitiveness, and facilitate access to fair markets. The study by Bikkina et al. (2018) suggests that FPOs have the potential to provide benefits through effective collective action. FPOs aid farmers in saving on input purchases and cropping patterns, increasing productivity, reducing transaction costs, and increasing production and technical efficiency. Farmers benefit from FPOs in terms of increased employment opportunities inside the community, which has improved family financial conditions and decreased labor migration (Trebbin & Hassler, 2012). FPOs positively impact farmers’ socioeconomic conditions by enhancing their skill development, psychological well-being, and social and economic aspects (Srinithi, 2022). The study by Trivedi et al. (2023) revealed that FPO members, especially small and marginal farmers, experienced a positive socioeconomic impact due to exposure to new techniques and increased bargaining power through collectivization. FPO provides institutional support to farmers, including information on input availability, subsidiary activities, state department schemes, technical support on crop production, and credit support when needed (Cherukuri & Reddy, 2014).

The study by Kumari et al. (2021) reveals that the FPO model effectively manages and sustains the Agri Value Chain. Numerous studies have assessed the impact of FPO on farmers’ livelihoods, revealing that producer companies enhance their members’ security in social, human, economic, and political capital (Mukherjee et al., 2020; Mukherjee et al., 2019). As marketing of agri produce of the farmers is the primary concern of FPO, the studies revealed that FPO members outperform non-FPO members in market efficiency, price spread, and producer share in the consumer’s rupee, with lower market margin and marketing cost compared to non-FPO marketing channels (Kumar, 2021). The study by Kumar et al. (2023) revealed that untreated farmers have a higher poverty incidence and severity than treated farmers. FPO membership positively impacts price realization and poverty alleviation, with farmers experiencing higher prices and annual agricultural income. The study’s findings by (Gurung et al., 2024) confirm that FPO membership positively and significantly impacts net returns, return on investment, and profit margin.

Despite the benefits that farmers receive from FPOs, there are several obstacles that FPOs must overcome. These include limited cash availability, difficulty linking farmers to markets, and a need for managerial expertise (Nikam et al., 2019). Additionally, Modern retailers frequently have bad experiences with producer firms because they have low standards for timely delivery, low expectations for product quality, and low quantity needs for fresh goods. Not much data was available on these new forms of FPOs, making it difficult for FPOs to assess, learn from, and collaborate. Subsequent investigations into the financial performance of FPOs have revealed that these entities are experiencing poor economic outcomes, raising concerns about solvency, financial sustainability, and overall financial health (Roy, 2023). As the newest type of collective in India, FPOs do have the potential to help and speed up the nation’s progress towards sustainable development. However, the issues with working capital, financial sustainability, complex compliance systems, lack of data, lack of professionalization, and skilled staff require immediate attention and, if left unattended, could harm the highly positive perception of FPOs (Mourya & Mehta, 2021). Assessing FPOs’ long-term sustainability and influence is made more difficult by the lack of longitudinal data and real-time performance tracking (Kumar & Reddy, 2023). No empirical study highlighted professionalization’s impact on FPO performance (Rao & Verma, 2021). Several studies revealed that financial constraints mainly limited working capital, and access to credit restricted FPOs' growth (Reddy et al., 2021; Gupta & Verma, 2020).

Team building and leadership development are the first steps in overcoming these obstacles and advancing towards successful FPOs (Patil & Mehta, 2024). The extension system must play a significant role in helping farmers become competent producers, leaders, and businesspeople to help them enhance their skills and capacities. It is necessary to cultivate awareness, foster entrepreneurship, and create sector-specific models, strategies through linkage and convergence, effective conflict resolution mechanisms, collaboration in decision-making, and a strong rapport with resource centers (Mukherjee et al., 2018). The studies related to the Sustainability of FPOs by (Thamban et al., 2020; and Shah, 2016) suggest a few steps to sustain FPOs’ activities, which include restructuring the value chain, assigning specific roles to stakeholders, creating functional linkages, professional managers run businesses in the members’ interest, frequent meetings, continuous training, and performance linked compensation.

While there is consensus across studies that FPOs enhance farmers’ socioeconomic conditions, increase efficiency, and contribute to poverty alleviation, recurring gaps remain. There is a lack of comprehensive financial performance assessments, and more research is needed to explore innovative strategies for enhancing solvency and managerial efficiency. The studies vary in focus, with some emphasizing productivity and price realization, while others highlight institutional support and structural challenges. Future research should integrate these perspectives to develop holistic policy recommendations. The literature review reveals that quantitative research methodology is used in most research, with limited qualitative studies and a thorough analysis of particular phenomena and cases. Figure 1 shows the exact categorization of the papers based on research methodology.

FPOs hold immense potential for transforming India’s agricultural landscape, but their sustainability depends on addressing financial, managerial, and market-related challenges through strategic interventions. Research concurs on the positive implications of FPOs regarding socioeconomic improvements, higher productivity, and poverty reduction; however, the gaps continue to be pronounced. A proper, comprehensive financial performance review is also inadequate, and it needs more analysis for innovative interventions towards the effectiveness of management and solvency. The study approach is diversified by focus. Price realization and productivity form one dimension, and issues related to structural aspects and institutional support for FPOs are on another dimension. These views should be integrated into future studies to offer complete policy recommendations. In conclusion, FPOs have the potential to revolutionize the Indian agricultural scenario. However, their viability depends on the strategic solutions that can be derived for financial, managerial, and market-related problems.

Hence, building on these insights and identifying the diversity in the focus of the studies in the literature, the present study seeks to address the following research questions.

Research questions

The current research aims to contribute significantly to the subject area of FPOs in India by addressing the gaps and answering the underlying questions. The absence of a literature review on this subject area is evident in existing research. Therefore:

RQ1: What are the main trends in the literature on FPOs regarding productivity, countries, authors, sources, and influential articles?

RQ2: What are the key themes identified in the literature on FPOs, and what areas show convergence and divergence?

RQ3: What research gaps are identified in the literature on FPOs, and what opportunities exist for future research?

Research methodology

This study uses the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) procedure to conduct a Systematic Literature Review (SLR). The PRISMA approach identifies and selects scientific publications of outstanding quality and impact. It is divided into four stages: (1) identification, (2) screening, (3) eligibility, and (4) inclusion (Moher et al., 2009). As shown in Fig. 2, the PRISMA flow diagram was strictly followed and applied in this SLR. As a result, the technique included four significant processes: procedure description analysis (Identification), article selection (Screening), finding FPO-related publications (Eligibility), and finally, selecting papers (Inclusion). The incorporation of quality assessment and risk of bias is significant for the reliability of the systematic literature review. The initial stage was a keyword search. Although the study is not free from biases, the Scopus database was used to compile significant literature sources on FPO, which led to overlooking the studies that might be valuable for the study. The extracted papers were carefully reviewed and examined in detail, and only the papers that were relevant to the study were considered. The quality assessment is based on credibility, transferability, and reliability. A systematic keyword search was first used to find 3796 articles on FPO from Scopus. The Scopus database has been considered for data extraction due to its organized and structured databases, reliability in citation metrics, and constant updates of new articles. Scopus provides 20% more coverage than Web of Science and gives results with consistent accuracy than Google Scholar (Falagas et al., 2008). For conducting the literature search, the following keywords were used: “Producer Company,” “Farmer Producer Organization,” “Farmer Producer Company,” “Farmer” AND “Producer” AND “agriculture,” “FPO” OR “FPC” AND “agriculture.” The following exclusion criteria were used to remove articles on FPO: (1) Year, (2) Document type (editorial, erratum, etc.), (3) Publication stage (Article in press) (4) Language (other than English) and the inclusion criteria were used to pick articles on FPO: (1) the keywords mentioned above; (2) publications between 2002 and 2023; (3) articles, reviews, and conference papers; (4) English language; (5) Publication stage; and (6) only papers pertinent to the topic of FPO.

After eliminating the duplications from the retrieved data, 3796 and 3773 papers remained. Of 3773 papers, 3677 did not fit the inclusion criteria. Hence, 96 viable papers were found, and 27 articles were excluded due to irrelevance, unclear methodologies, and not meeting thematic relevance. Hence, 64 papers from the final sample were selected to conduct the Bibliometric analysis of the topic of FPO in greater detail for qualitative and quantitative analysis. Quantitative bibliometric analysis concentrates on objective and numerical data such as productivity patterns, citations, and co-authorship by incorporating statistical measures and metrics.

In contrast, qualitative bibliometric analysis comprises deciphering the meaning and deeper insights into the content and impact of the research area. The two approaches of bibliometric analysis have been considered: performance analysis and science mapping. In performance mapping, the evaluation of the impact of authors, affiliations, and countries is identified using publications and citation indicators. The publication indicator is related to determining the quantity and affiliated aspect, while the citation indicator is about recognizing the significance and influence of the study through citations. Science mapping is the quantitative analysis, visualization, and classification of the dynamics of available literature. The cited work analysis helps identify the scholarly literature’s highest impact; co-citation analysis shows the correlation between references; co-occurrences of the words represent the links between keywords; co-authorship represents the collaboration between authors; and bibliographic coupling measures the similarity between articles through citation analysis. The present study uses VOSviewer for science mapping techniques to construct and visualize scientific landscapes, as it is user-friendly and provides a map of clusters and links in citation, co-citation, and bibliographic coupling while supporting different databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and Medline (Klarin, 2024). Bibliometrics, an R package, is also used for creating visualizations such as a word cloud, which shows the frequency of each keyword, determining its size.

Through this analysis, we can address the research questions by examining several previously published pieces of literature, including trends, country productivity, authors, sources, and top-cited articles. Furthermore, the findings from the analysis are structured in a comprehensive framework for getting clear insights into the themes in the existing literature and identifying unexplored areas.

Results and discussion

In this section, we outline the findings from bibliometric analysis using performance analysis and science mapping techniques through VOSviewer and Biblioshiny. In addition to the quantitative bibliometric analysis, the study presents qualitative analysis, such as content analysis of the curated studies, stating the systematic literature review (SLR). With the help of categorization and exploration of the content of selected articles, this study has identified key themes, trends, and unexplored research areas. Leveraging SLR with bibliometric analysis enables a more comprehensive understanding of the research field.

Publication productivity

The Government of India changed the Firms Act 1956 in 2002 by adopting section IX A, establishing producer firms managed by primary producers. This is why the studies from 2000 have been chosen for analysis. However, it has been revealed that no pertinent study on FPO was found between 2002 and 2007.

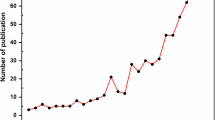

As Fig. 3 illustrates, there has been an overall upward trend in publications from 2008 to 2023. The articles from the year 2024 have also been considered for the study. Furthermore, many published papers have been disqualified for further review because of the SLR’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. The pattern indicates that, despite the Producer Company Act being passed in 2002, there were few publications between 2002 and 2013. Following the 2013 introduction of the FPO policy guidelines, FPOs began to operate actively, and the new scheme to establish 10,000 FPOs was introduced in 2022, which can be the reason for the rising trend in FPO research that has been seen since 2022.

Journal productivity

Figure 4 represents the journal-wise productivity in the subject area, highlighting the contributions from different journals. Although FPO is related to the Indian Agricultural sector, several journals have published related articles. The Indian Journal of Extension Education has the highest number of publications, with seven documents, while the Indian Journal of Agricultural Science follows with four papers. Of the top 10 journals, Millennial Asia and other journals have two published documents each.

Country productivity

Figure 5 represents the country’s productivity in terms of research publications conducted for farmer-producer organizations. Although FPO is primarily related to India, many countries have still shown interest in research in this area. India dominates the research, with 154 countries, while the rest are far behind. The second and third highest countries, Germany and the UK, have 8 and 6 publications, highlighting the vast gap in publications. It is imperative to note that even though FPO is India’s most recent form of farmer’s collective, several developed nations are considering working on it.

Authors productivity

Figure 6 illustrates the Author-wise productivity in publications and citations of the top 10 authors of the subject area. Of them, Kumar S has the highest number of publications and citations: five documents and 39 citations, followed by Mukherjee, A. with four papers and 16 citations. Singh, P., Nikam, V., and Gurung, R. also have three documents each, while Bijman, J. has only two publications but has garnered 39 citations.

Top 10 highest-cited documents

The documents with the most citations show their significant influence within the subject area. The number of times other scholars have referenced a document in their research work is analyzed by citation count. Table 1 shows the article with the highest citations. The document “Linking small farmers to modern retail through producer organizations—Experiences with producer companies in India” has the highest number of citations, which is 113; this paper has the highest citations as it demonstrates the significance of producer organizations in upholding farmers’ status in the supermarket supply chain. The article “Collaborative innovation and sustainability in the food supply chain—evidence from FPOs” has the second highest number of 76 citations, which has led to stress on the investigation of adopting innovative practices for sustainability in food supply chains. The article is followed by “Which type of producer organization is (more) inclusive? Dynamics of farmers’ membership and participation in the decision‐making process,” which has 30 citations, highlighting the impact of producer organizations on farmers’ membership and decision-making processes. The findings from these articles are beneficial for inclusive development strategies. The citation analysis reflects that many studies have been conducted in the FPO, as substantial citations have been received.

Co-citation analysis

Co-citation analysis is an approach that helps track down interconnected research items and understand interdisciplinary connections from different disciplines. It assumes that the cited documents have a common theme among them. It works on the principle that if two Journals (X1 and X2) cited other standard documents (Y1, Y2, Y3), then the documents Y1, Y2 and Y3 will have some interlink among them.

For this study, the minimum citation threshold of 4 was established; out of 2046, only 75 met the criterion. For the authors, the minimum threshold of 10 was established; out of 3206 authors, only 96 met the criterion.

For further analysis, Table 1 represents the documents and authors with the most citations recognized to determine a framework for farmer-producer organizations. The analysis (Trebbin, 2014) is rooted in thoroughly investigating the Indian market for producer companies and opportunities for foreign entrants to integrate into supply chains. (Krishnan et al., 2021) have shed light on the significance of collaboration within the FPO, which can lead to innovation and improve sustainability. The compilation of co-citation analysis shows the importance of FPO not only for the agricultural sector but also for Business Management and Economics. The co-citation analysis is shown in Figs. 7 and 8, and the analysis is shown in Table 2.

The study has elaborated on five different themes from co-citation patterns and clarified the significance to the broader context of the study. The yellow items represent farmer organizations’ roles, collective actions, and market reach for cross-border contexts. The growing rural producer organizations highlight the importance of the agricultural value chain and economic development. Contract farming is also explored as a potential mechanism for providing opportunities to small-scale farmers in developing countries. The items in purple underscore the prospects of organized farmer groups for reducing poverty by improving incomes, enhancing market supply chains, and facilitating changes in agricultural landscapes. The items in the blue centre around the significance of farmer producer organizations for providing support to smallholder farmers by working as a pathway of empowering market linkages and facilitating bargaining power and access to resources. This leads to the enhancement of the economic viability of smallholder farmers. The item in red reveals the significance of FPOs in enabling farmers to pool resources, make collaborative decisions, reduce dependency on intermediaries, and give them a platform for direct selling by sharing associated risks. The items in green focus on addressing the challenge of market fragmentation and unequal bargaining power, where the smallholders can participate in modern agricultural markets to improve their financial stability.

Co-occurrence of keywords

The co-occurrence of keywords is another science mapping technique where the keywords with the highest number of occurrences are represented in clusters. The co-word analysis assumes that the primary keywords used in the research words reflect the core context of scholarly literature—the keywords with higher occurrence are said to have similar themes, which later on can form clusters. The keyword with the highest number of occurrences appears bigger. Figure 9 represents a word cloud where “India,” “Agricultural worker,” “Agriculture,” and “smallholder” have the highest occurrences.

Bibliographic coupling

Bibliographic coupling is another science mapping technique that finds the theoretical similarity in documents through citation analysis. When two documents (A & B) have a standard third document (C) in their bibliography, A & B are said to be bibliographically coupled. The coupling strength increases with more shared citations. The bibliographic coupling facilitates easier retrieval of the latest data and scientific development from scholarly literature. For this analysis, the minimum threshold is established at 3, and in the unit analysis of articles among 64 articles, only 45 met the criterion, while for authors, only 45 met the criterion. The Bibliographic coupling visualization from VOSviewer is represented in Figs. 10 and 11, and the analysis is shown in Table 3.

Cluster analysis

It is based on the Cluster Analysis using VOSviewer, which showcases the in-depth overview of the nodes connected in networks, closely forming clusters. A different color represents every cluster. Figure 12 represents seven clusters, each represented by different colors such as red, green, blue, purple, teal, orange, and yellow. Cluster 1 in red colors consists of keywords such as “Agricultural Marketing, Farmers Knowledge, Sustainable Agriculture, Supply Chain Management, Dairy farming, Farmers, Marketing, etc.,” which represents the theme of Enhancement of Sustainable Agricultural Marketing in the supply chain management of Dairy farming by motivating stakeholders and farmers’ perception in producer organizations. Cluster 2, in green, consists of keywords such as “Agricultural Production, Collective Action, Small and Marginal Farmers, etc.,” which represents the enhancement of earnings of small and marginal farmers in India by strengthening agricultural production through collective action. Cluster 3, in yellow color, has keywords such as “FPC, FPO, Membership, Performance, Producer Organization, Profitability, Rajasthan, etc.,” each representing the theme of assessment of the impact of membership in FPOs for high performance and profitability, specifically referencing Rajasthan. A recent study by Bharti & Kumari (2024) developed a performance evaluation matrix for farmer-producer organizations in India. Cluster 4, in purple color, has keywords such as “Agri-business, Agriculture, Farmers, Income Enhancement, Madhya Pradesh, Women Empowerment, etc., which captures the theme of empowering women farmers and income through agri-businesses and FPOs with special reference to Madhya Pradesh. Cluster 5, which is represented in blue color, consists of keywords like Agricultural Technology, Crop Production, Empowerment, Livelihood, Participation, Rural Development, Organic Farming, Sikkim, etc., representing the theme of the growing participation of farmers in agricultural technology and organic farming in the improvement Crop Production and Livelihoods. Cluster 6 shows the keywords Coconut Sector, Farmer Producer Organization, Market Efficiency, and Sustainability in orange, representing FPOs’ role in market efficiency and sustainability in the coconut farming sector. Finally, cluster 7 in turquoise color shows the keywords Agricultural workers, Food Supply Chain, Innovation, Sustainable Development, Technical Efficiency, etc., which reflect the role of agricultural workers in driving innovation and achieving sustainable development in the food supply chain.

Based on the literature review and results of the cluster analysis, it is observed that though the GoI amended the Companies Act 1956 in 2002 by introducing section IX A, establishing producer companies managed by primary producers, before the releasing of policy guidelines in 2013, there was no much literature available on FPO; instead, it is an emphasis on cooperative models and producer cooperatives. After the release of policy guidelines for FPO, research on FPO’s institutional capacities, governance, financial sustainability, and market linkages has been conducted. After 2022, the literature trend is more focused on FPOs’ challenges, impact assessment, digitization, and sustainability of FPOs (Tables 4–6).

Discussion

The research’s quantitative analysis was based on the research questions’ foundation. To address RQ1, the author extracted the articles on FPO from 2008 to 2023, where the publication has grown steadily. Furthermore, 2022 and 2023 show the highest number of publications, which is 14, followed by 2021, with 11 publications. The trend represents the growing popularity of FPOs in the agricultural sectors, and it calls for identifying the underlying opportunities and challenges. Authors have found that India has the highest number of publications in country productivity. In contrast, the International Journal of Extension Education has the highest number of articles published in journal productivity, and Kumar, S., has published the highest number of articles in the subject area with five documents and 39 citations. Furthermore, the article titled “Linking Small Farmers to Modern Retail Through Producer Organizations—Experiences with Producer Companies in India,” authored by (Trebbin, 2014), has garnered the highest number of citations, followed by “Collaborative Innovation and Sustainability in the food supply chain—evidence from FPOs” authored by (Krishnan et al., 2021) and “Which type of producer organization is (more) inclusive? Dynamics of farmers’ membership and participation in the decision‐making process” authored by (Mwambi et al., 2020).

Producer companies in India provide an opportunity to be integrated into the value chains of modern retailers. However, several have failed to do so because they need more capabilities and support at the right time and in proper quantities. The Indian government should continue supporting producer companies financially to ensure that welfare and business orientation are not unbalanced (Trebbin, 2014). The article by Krishnan et al. (2021) examines how collaboration within FPOs drives innovative practices and improves sustainable outcomes across the FSC. The paper recommends policies that include motivating collaborative network formation, supporting infrastructure development and technology assistance, providing education, and fostering collaboration between industry, government, and research institutions. Though development agencies and policymakers support producer organizations to enhance smallholder participation in the agri-food value chain, interest in vertical integration may disintegrate poor farmers. Hence, there is a need to focus on bargaining power for all farmers involved in decision-making processes to cut costs and enhance women’s participation rates (Mwambi et al., 2020). The authors (Rani et al., 2023) analyzed the main drivers of FPOs in terms of their operations, financials, and outreach, and common performance metrics were established. The results show that a strong institution with strategically placed internal committees will significantly improve them. The only way to achieve this aim is to continuously increase the capability of all stakeholders involved.

In response to RQ2, the FPOs are driven by the fuel of assisting in the farmer’s bottom line. Therefore, it is important to formulate a heterogeneous narrative emerging from seven distinct yet interconnected clusters within the agricultural landscape. The authors have identified various themes, each representing the core aspect of the subject area of Farmers’ Producer Organizations.

Theme 1: Empowering dairy farming: enhancing perception, motivation, and sustainable supply chain collaboration. (Cluster 1)

Cluster one represents developing dairy farming through farmers’ and stakeholders’ perception, motivation, and knowledge for agricultural marketing by collaborating on sustainable agriculture and supply chain management. Sustainable agriculture and dairy policies aid small and marginal farmers who do not have more than 2 hectares of farming land. Such farmers do not have perception, motivation, and access to financial assistance due to high interest rates, transaction costs, and associated risks (Chaturvedi et al., 2024). Collaboration has been recognized as the key strategy for sustainable agriculture, which, one way or another, contributes to the effective management of natural resources and farming practices and provides financial assistance (Velten et al., 2021). There is a notable example of Brazil’s pork industry where the streamlined collaboration between producer organizations, small farmers, and other private firms ignited new waves of transformations in the industry (Vilas-Boas et al., 2022). However, a conflict of interest arises among the stakeholders due to limited resources, where the collaborators stress income generation for high-return crops, while in the case of staple crops, they tend to concentrate on advancing household food resilience (Mishra et al., 2024). Implementing sustainability schemes requires technical support from the supply chain leaders to enable farmers to survive in a competitive environment.

Theme 2: Boosting small farmers’ income through collective agricultural action in India. (Cluster 2)

Cluster two highlights the increment in the income of small and marginal farmers by strengthening agricultural production through collective actions in the Indian context. The Indian agricultural market has struggled chiefly to yield high returns due to a compromised supply chain, limited access to the market for farmers, etc. Farmer Producer Companies’ association with producer companies has been a helping hand for farmers. The collective actions of the association have not only strengthened agricultural production but also resulted in a reduction in cost and revenue generation (Kumari et al., 2021). Baruah et al. (2022) have piloted a collective action model, “Small Farmers Large Fields (SFLF),” to minimize the disadvantages of diseconomies of scale and garner bargaining power by consolidating the resources and connecting them with the market. Some farmers join the Farmer Association initially but are later unable to continue there, which impacts their financial outcomes (Kakati & Roy, 2022).

Theme 3: Impact of farmer producer organization membership on productivity, income, and profitability (Cluster 3)

Cluster three represents the benefits of membership in farmer-producing organizations on farmers’ productivity, income generation performance, and profitability. Farmer Producing Organizations significantly harmonize agricultural production and marketing (Prabhavathi et al., 2023). Small and Marginal Farmers face challenges such as high finance costs, access barriers to input and output markets, access constraints to new technology, reliance on outdated technology, poor harvest, high supply chain costs, and insufficient profits resulting in economic stagnation (Meemken & Bellemare, 2020). Muniyoor & Pandey (2024) have shown that the business skills and fiscal viability of market-driven FPOs tend to be higher than those of Production-driven FPOs. Where there is a high correlation between skills and performance. The analysis of Gurung et al. (2024) found that affiliation with FPO positively impacted their net profit and return on investment and increased their earnings margin, while non-affiliation resulted in lower net profit, return on investment, and reduced earnings margin. The studies (Mukherjee et al., 2020; Singh, 2022) have stated a positive impact of FPO on farmers in enhancing livelihood security in social, human, economic, and political capital.

Theme 4: Empowering women in agriculture: the role of FPOs and agri-businesses in enhancing income (Cluster 4)

Cluster four showcases the role of FPOs and agri-businesses in empowering women-led agricultural income. Women’s involvement in agricultural practices not only underscores the significance of gender equality but also their influence in augmenting productivity and food security (Prithika et al., 2024). Even though women have made significant contributions to cultivation, due to prolonged inequality, there is a lack of participation in FPO activities. Only 3% of operating FPOs in India are led by women entrepreneurs (Harrington et al., 2024). FPOs initially emphasized upholding the position of male agricultural workers, but due to the current era of empowerment, women are also participating in farming activities to ensure inclusive agricultural development. The women are actively participating in farm businesses, and they are increasing their sources of revenue. However, FPOs are facilitating women farmers in improving decision-making skills, bargaining power, market accessibility, and garnering support for collective procurement of inputs and financial services (Anand et al., 2025). In India, women farmers face a few challenges, such as a lack of knowledge and land title, which makes it difficult to get bank loans and credit (Singh et al., 2022). Meanwhile, the north-eastern women’s participation in collective organic agricultural groups shows the prospects of organic farming to strengthen females economically and socially (Abdullah & Parvin, 2024).

Theme 5: Boosting rural agriculture: crop production and livelihood through technology and organic farming. (Cluster 5)

Cluster five represents the theme of the development of rural agricultural areas through the participation of farmers in increasing crop production and livelihood through the adoption of agricultural technology and organic farming. Adopting technology has led to a significant increase in agricultural production, which helps promote economic growth with scarce resources and erratic climatic conditions in underdeveloped countries like Nepal (Evenson & Gollin, 2003). The technological adoption and diffusion in farm practices are encouraged through enhanced market accessibility, reduced transportation and transaction costs, lowered production costs, higher profit margins, and exposure to new technologies (Kumar et al., 2020). FPOs can facilitate a blend of organic farming, and modern technologies can pave the way towards sustainability, boost agricultural productivity, and increase profitability for farmers (Gamage et al., 2023). However, Consumers are less likely to prefer sustainable practices if they do not fall under the widely accepted organic farming framework (Naspetti et al., 2021). FPOs’ progress depends on the smallholder farmers’ empowerment through self-efficacy and on developing substantial, cooperative social capital for value addition and improved performance (Pant et al., 2024). This will facilitate income generation in rural areas, and adopting organic agriculture will benefit society. The study (Suresh & Ss, 2024) identified FPOs’ sustainability factors, driven by economic, social, and environmental factors. Economically, increased farm income is an enabler, while inadequate capital is a disabler. Socially, bargaining power and opportunities for capacity building are enablers. However, farmers contend that sustainability is a mirage without effective leadership approaches and upskilling. Environmentally, practical organizational activities such as branding and capacity building are enablers, while poor infrastructure, poor structure, and climate change are disablers.

Theme 6: Enhancing market efficiency and sustainability in the coconut sector through farmer producer organizations (Cluster 6)

Cluster six illustrates the significance of the Farmer Producers organization in increasing market efficiency and sustainability in the coconut sector. FPOs facilitate farmers by enhancing their accessibility to the market, adding value, improving their farming practices, and improving their livelihood. The coconuts are generally grown by small and marginal holders, who are at higher risk due to economic risk and uncertainties leading to market price fluctuations (Thamban et al., 2020). FPOs have shown their significance in continuous revenue generation and other benefits in the coconut sector through practical collective actions. However, parameters beyond profit should also be considered, such as providing resilience to farmers against uncertainties, procuring higher prices than prevailing market prices, and providing technological assistance (Jayashekhar et al., 2024).

Theme 7: Role of agricultural workers in innovation and sustainability in food supply chains (Cluster 7)

Cluster seven represents the theme of the significance of agricultural workers for innovation and technological competence in the food supply chain for sustainable development. The involvement of agricultural workers provides practical insights, ensures technical efficiency aligned with practical needs, and promotes sustainability. In Nigeria, the Agricultural Development Facilitator supports production and sustainability through the adoption of technologically advanced tools such as artificial intelligence, deep learning, mobile-based information systems, and precision agricultural and climate-smart practices, which boost production, decrease the chance of post-harvest loss, and ensure equitable market accessibility (Oluwakemi Betty Arowosegbe et al., 2024). Sustainable Supply chain Management fosters the agricultural sector by managing raw material flow to reduce food wastage while maintaining economic viability (Ahi & Searcy, 2013).

Based on the present findings and discussion, the Theory of Change (ToC) framework is proposed to improve FPO effectiveness. Following Reddy (2019), we outline a structured pathway linking key challenges, required interventions, and expected outcomes. We propose this TOC based on the challenges identified and discussed in the earlier sections.

Figure 13 mentions the flow chart of TOC tailored to the specific context of FPO adoption from Reddy (2019). The subsequent section highlights the policy implications that discuss Fig. 13 on an extended basis.

Limitations and future research direction

This is a systematic literature review; hence, it is possible that some critical research was skipped. Additionally, since this study is based on secondary data, the ability to confirm results using primary evidence is restricted. Future research should use a mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative and qualitative analysis to capture the subtleties of FPO operations and their long-term sustainability. A more in-depth understanding of the sustainability of FPOs can be achieved through longitudinal studies that assess their governance and financial health over time. Comparative case studies between successful and unsuccessful FPOs help find a scalable model and good practices for FPOs. Deeper insights into market connections, financial sustainability, and governance issues may also be obtained using specialized research tools such as network analysis, econometric modeling, and participatory rural evaluation techniques. Filling in these research gaps would aid in creating focused legislative initiatives and workable plans for bolstering FPOs in India.

Policy implications

Policymaking would be essential to address the problems of FPOs by devising interventions to enhance their operational efficiency. Among other issues, one of the primary challenges relates to the complicated procedure for documentation that burdens the Board of Directors, who are farmers. The lengthy formalities and the distance of the offices of the regulatory bodies from villages make it a cumbersome task. The highest priority recommendation is to make these procedures easier by digitizing documentation, decentralizing facilitation centers, and training programs for BoDs on how to get through the paperwork quickly. This would enable FPOs to spend more time on their core activities than on bureaucratic red tape.

Another critical challenge is the lack of market linkage, which is still the most significant hurdle despite being the core objective of FPOs. The study by Prabhavathi et al. (2024) underscores the potential benefits of adopting a market-centric approach for upcoming and existing production-centric FPOs. Policies should focus on capacity-building initiatives that provide FPOs with market intelligence, value-addition strategies, and business planning skills. Partnerships with agribusiness firms, promotion of digital market platforms, and integration of FPOs into e-commerce and government procurement schemes should be given priority. These measures allow FPOs to understand consumer demand better and receive better returns for their produce.

Taxation policies also need an immediate focus. Though cooperatives are exempted from taxes, FPOs were initially liable to corporate taxation under Section 35CCC of the Income Tax Act, 1961. Though partial tax relief was brought in 2017, inconsistencies in tax treatment continue to mar the growth of FPOs. A uniform tax-exemption policy for FPOs, like cooperatives, should be implemented to make them viable. Furthermore, a simplified regulatory framework should ensure tax benefits reach the intended beneficiaries without administrative complexities.

Another issue that requires a rethink of policy is FPO’s inability to provide subsidized fertilizers. Fertilizer subsidies are allowed by cooperatives. However, FPOs are not allowed to market fertilizer under the Fertilizer Control Order, 1957/1985, implemented by the state governments and is part of the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, Government of India’s licensing policy. Due to the bureaucratic process, FPOs stated that obtaining an Agricultural Produce Marketing Committee (APMC) mandi license is too much work. Since delivering inputs is a primary function of FPOs, one of their key concerns is their inability to supply subsidized fertilizer. Therefore, it is necessary to re-examine this issue; reforms should be undertaken to allow FPOs to access subsidized fertilizers as cooperatives have. A transparent licensing framework, with state-level facilitation for FPOs, would help overcome bureaucratic delays and improve farmers’ access to affordable inputs.

The lack of professional leadership in FPOs is another significant issue, and many FPCs are not owned and operated by farmer producers but by prominent business people and professionals. Many people in business and professions have taken on the role of FPO leader to bridge the gap left by incompetent leadership. Farmers lack the skills necessary to lead a business; therefore, they will require professional assistance or training to become qualified to handle FPO business. However, there are instances where wealthy individuals and experts take over FPO businesses, and as a result, there needs to be regulations prohibiting outside parties from interfering with FPO. Otherwise, there is a possibility that farmer producers will lose authority over FPO.

By focusing on these policy recommendations, streamlining documentation, enhancing market access, ensuring fair tax treatment, allowing fertilizer distribution rights, and promoting farmer-led leadership, FPOs can be better equipped to operate effectively and achieve their goal of boosting farmers’ economic well-being. It will be crucial to implement these reforms through collaborative efforts among government agencies, policymakers, and FPO networks to ensure sustainable growth in the sector.

Conclusion

The study intends to present a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of FPO research, addressing a critical gap in the existing literature by systematically mapping publication trends (2002–2023) and emerging themes that facilitate future research. We provided a structured overview of the FPO landscape based on 64 relevant studies and identified a critical area that requires further exploration. This comprehensive synthesis of research on FPO contributes to the ongoing discourse on their role in Indian agricultural development. The findings highlight the need for targeted policy interventions (Fig. 13) and further empirical research to support FPOs as viable models for improving farmer livelihoods. Future studies should focus on institutional mechanisms, digital transformation, and long-term sustainability to enhance the impact of FPOs in India and beyond. By addressing these gaps, academia and policymakers can contribute to more effective and resilient FPO models, ensuring inclusive growth in the agricultural sector. We suggest supporting Govt. policies, including simplifying the documentation process, ensuring fair tax treatment, and allowing FPOs to distribute essential agricultural inputs such as fertilizers, enhancing their market competitiveness. We also propose building a government or FPO-led capacity development program to strengthen the decision-making process in the long run. The TOC model also proposes adopting digital tools by Indian FPOs that would facilitate FinTech solutions that can bridge the gap between farmers and markets with improved transparency. Finally, we propose some specific policies that promote gender diversity through inclusive leadership that recognizes the role of women in the agriculture sector.

Data availability

The corresponding author holds the VOSviewer data and all 64 papers included in the analysis. These can be made available upon request.

References

Abdullah M, Parvin SS (2024) Organic farming through sustainable production, its socioeconomic impacts in rural livelihood and for community development. Appl Agri Sci 2(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.25163/agriculture.2110017

Abraham M, Verteramo Chiu L, Joshi E, Ali Ilahi M, Pingali P (2022) Aggregation models and small farm commercialization—a scoping global literature review. Food Policy 110(102299):102299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102299

Ahi P, Searcy C (2013) A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J Clean Prod 52:329–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.02.018

Anand G, Kalaiselvi P, Sebastian SP, Kumar MS, Amuthaselvi G, Porkodi G, Suganya K, Malathi G (2025) Role of farmer producer organizations in promoting women empowerment in agriculture. Int J Agri Ext Soc Dev 8(1):453–464. https://doi.org/10.33545/26180723.2025.v8.i1g.1568

Anand S, Ghosh S, Mukherjee A (2023) Effectiveness of farmer producer organizations (FPOs) at different growth stages in transitioning to secondary agriculture. Indian J Ext Educ 59(3):90–96. https://doi.org/10.48165/ijee.2023.59317

Baruah S, Mohanty S, Rola AC (2022) Small Farmers Large Field (SFLF): a synchronized collective action model for improving the livelihood of small farmers in India. Food Security 14(2):323–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01236-x

Bernard T, Spielman DJ (2009) Reaching the rural poor through rural producer organizations? A study of agricultural marketing cooperatives in Ethiopia. Food Policy 34(1):60–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.08.001

Bharti N, Kumari S (2024) Development of performance evaluation matrix for farmer producer organizations in India. Int J Prod Perform Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijppm-09-2023-0460

Bikkina N, Turaga RMR, Bhamoriya V (2018) Farmer producer organizations as farmer collectives: a case study from India. Dev policy Rev J Overseas Dev Inst 36(6):669–687. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12274

Boskova I, Ahado S, Ratinger T (2020) The effects of the participation in producer organizations on the performance of dairy farmers in the Czech Republic and future challenges. Agric Econ 66(8):345–354. https://doi.org/10.17221/2/2020-agricecon

Chaturvedi AKR, Singh R, Tewari CKR (2024) A qualitative analysis of dairy farming policies and its stakeholder’s perspective in the Indian dairy sector. Model Assist Stat Appl 19(3):293–299. https://doi.org/10.3233/MAS-241936

Chauhan S (2016) Luvkush crop producer company: a farmer’s organization. Decision 43(1):93–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40622-015-0121-1

Cherukuri RR, Reddy AA (2014) Producer organizations in Indian agriculture: their role in improving services and intermediation. South Asia Res 34(3):209–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0262728014544931

C Penrose-Buckley (2007) Producer organizations: a guide to developing collective rural enterprises, Oxfam

Evenson RE, Gollin D (2003) Assessing the Impact of the Green Revolution, 1960 to 2000. Science 300(5620):758–762. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1078710

Fischer E, Qaim M (2012) Linking smallholders to markets: determinants and impacts of farmer collective action in Kenya. World Dev 40(6):1255–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.11.018

Gamage A, Gangahagedara R, Gamage J, Jayasinghe N, Kodikara N, Suraweera P, Merah O (2023) Role of organic farming for achieving sustainability in agriculture. Farming Syst 1(1):100005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.farsys.2023.100005

Government of India (2013) Policy and process guidelines for farmer producer organizations. Ministry of Agriculture, p. 95

Gupta P, Verma S (2020) Farmer producer organizations and rural livelihoods: a review. J Rural Stud 35(2):75–89

Gurung R, Choubey M, Rai R (2024) Economic impact of farmer producer organization (FPO) membership: empirical evidence from India. Int J Soc Econ 51(8):1015–1028. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-06-2023-0451

Gyau A, Mbugua M, Oduol J (2016) Determinants of participation and intensity of participation in collective action: evidence from smallholder avocado farmers in Kenya. J Chain Netw Sci 16(2):147–156. https://doi.org/10.3920/jcns2015.0011

Harrington T, Narain N, Rao N, Rengalakshmi R, Sogani R, Chakraborty S, Upadhyay A (2024) A needs-based approach to promoting gender equity and inclusivity: insights from participatory research with farmer-producer organizations (FPOs). J Soc Econ Dev 26(2):409–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-023-00280-x

Hellin J, Lundy M, Meijer M (2009) Farmer organization, collective action and market access in Meso-America. Food Policy 34(1):16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.10.003

Hussein K (2001) Producer organizations and agricultural technology in West Africa: institutions that give farmers a voice. Dev (Soc Int Dev) 44(4):61–66. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1110294

Jayashekhar S, Thamban C, Chandran KP, Thomas L, Thomas RJ (2024) Analysis of farmer producer organizations in the coconut sector: current scenario, limitations, and policy outlook. J Plant Crops 52(1):1–9

Kakati S, Roy A (2022) Financial performance of farmer producer companies of India: a study from 2013–2014 to 2018–2019. Int J Rural Manag 18(3):410–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/09730052211034700

Klarin, A (2024) How to conduct a bibliometric content analysis: Guidelines and contributions of content co‐occurrence or co‐word literature reviews. Int J Consum Stud 48(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.13031

Krishnan R, Yen P, Agarwal R, Arshinder K, Bajada C (2021) Collaborative innovation and sustainability in the food supply chain—evidence from farmer producer organizations. Resour Conserv Recycl 168(105253):105253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105253

Kumar A, Takeshima H, Thapa G, Adhikari N, Saroj S, Karkee M, Joshi PK (2020) Adoption and diffusion of improved agricultural technologies and production practices: Insights from a donor-led intervention in Nepal. Land Use Policy 95:104621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104621

Kumar M (2021) Marketing efficiency of different marketing channel of the mustard crop in SwaI Madhopur district of Rajasthan. Economics Affairs (Calcutta). 66(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.46852/0424-2513.1.2021.18

Kumar NKS, Reddy SR (2023) Assessing the long-term viability of farmers’ collectives in South India. J Rural Stud 94:346–357

Kumar S et al. (2023) Determinants of performance and constraints faced by farmer producer organizations (FPOs) in India. Indian J Ext Educ 59(2):1–5. https://doi.org/10.48165/ijee.2023.59201

Kumari N, Malik JS, Arun DP, Nain MS (2022) Farmer Producer organizations (FPOS) for linking farmers to market. J Extension Syst 37(1):1–6

Kumari S, Bharti N, Tripathy KK (2021) Strengthening agriculture value chain through collectives: Comparative case analysis. Int J Rural Manag 17(1_suppl):40S–68S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973005221991438

Lalitha N, Viswanathan PK, Vinayan S (2024) Institutional strengthening of farmer producer organizations and empowerment of small farmers in India: evidence from a case study in Maharashtra. Millennial Asia 15(2):278–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/09763996221098216

Malik S, Kajale D (2024) Empowering small and marginal farmers: Unveiling the potential and addressing obstacles of farmer producer organizations in India. Res World Agric Econ 5(1):32–47. https://doi.org/10.36956/rwae.v5i1.994

Manaswi B, Pramod P, Venu L (2020) Impact of farmer producer organization on organic chilli production in Telangana, India. Indian J Traditional Knowl 19:33–43

Meemken E-M, Bellemare MF (2020) Smallholder farmers and contract farming in developing countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117(1):259–264. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1909501116

Moher D et al. (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mojo D, Fischer C, Degefa T (2017) The determinants and economic impacts of membership in coffee farmer cooperatives: recent evidence from rural Ethiopia. J Rural Stud 50:84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.12.010

Mourya M, Mehta M (2021) Farmer producer company: India’s magic bullet to realize select SDGs? Int J Rural Manag 17(1_suppl):115S–147S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973005221991660

Mukherjee A et al. (2018) Enhancing farmer’s income through farmers’ producer’s companies in India: Status and roadmap. Indian J Agric Sci 88(8):1151–1161. https://doi.org/10.56093/ijas.v88i8.82441

Mukherjee A et al. (2019) Effectiveness of poultry-based Farmers’ Producer Organization and its impact on livelihood enhancement of rural women. Indian J Anim Sci 89(10). https://doi.org/10.56093/ijans.v89i10.95024

Mukherjee A et al. (2020) Assessment of livelihood wellbeing and empowerment of hill women through Farmers Producer Organization: a case of women based Producer Company in Uttarakhand. Indian J Agric Sci 90(8):1474–1481. https://doi.org/10.56093/ijas.v90i8.105945

Mwambi M, Bijman J, Mshenga P (2020) Which type of producer organization is (more) inclusive? Dynamics of farmers’ membership and participation in the decision‐making process. Ann Public Cooperative Econ 91(2):213–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/apce.12269

Nikam V, Singh P, Ashok A, Kumar S (2019) Farmer producer organizations: Innovative institutions for the upliftment of small farmers. Indian J Agri Sci 89(9). https://doi.org/10.56093/ijas.v89i9.93451

Patil R, Meena H (2020) Governance structures and decision-making in Farmer Producer Organizations. Indian J Agric Res 54(1):45–60

Patil S, Mehta M (2024) Ploughing new ground: Exploring the critical traits of leaders of farmer producer organizations. Indian J Ext Educ 60(4):67–72. https://doi.org/10.48165/ijee.2024.60412

Prabhavathi Y, Siddayya S, Ganapathy MS, Girish MR (2024) An economic analysis of FPOs in Andhra Pradesh: a comparative study based on business strategy. Indian J Agric Econ 79(2):187–197. https://doi.org/10.63040/25827510.2024.02.001

Prasad CS, Kanitkar A, Dutta D (2023) Producer organizations as 21st-century farmer institutions. London: Routledge, London, India. pp. 1–26

Rani CR, Reddy AA, Mohan G (2023) From formation to transformation of FPOs. Econ Polit Wkly 58(36):15

Rao EV, Verma S (2021) Professionalisation of farmer producer organizations: impact on performance and sustainability. J Agribus Dev Emerg Econ 11(3):241–256

Reddy S, Kumar V, Sharma R (2021) Financial sustainability of FPOs: Challenges and opportunities. Econ Polit Wkly 56:120–138

Reddy AA (2019) The soil health card scheme in India: lessons learned and challenges for replication in other developing countries. J Nat Resour Policy Res 9(2):124–156. https://doi.org/10.5325/naturesopolirese.9.2.0124

Roy H (2023) Comparative financial performance analysis of Farmer Producer Companies in Eastern Uttar Pradesh. Econ Affairs (Calcutta). 68(1). https://doi.org/10.46852/0424-2513.1.2023.17

Saha S, Sinha C, Saha S (2024) Agricultural marketing in India: challenges, policies and politics. South Asian J Macroecon Public Financ 13(1):39–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/22779787231209169

Shah T (2016) Farmer Producer Companies: Fermenting New Wine for New Bottles. Econom Econ Pol Wkly 51(8):15–20. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44004406

Sharma V, Rao D (2019) The role of government policies in strengthening FPOs: a policy analysis. Agric Policy J 22(4):95–110

Singh A, Sharma P (2021) Smallholder farmers and the impact of FPOs on market linkages and technology adoption. J Agribus Stud 40(2):65–82

Singh S (2008) Producer companies as new generation cooperatives. Econ Polit Weekly 22–24

Singh S (2016) Smallholder organization through farmer (producer) companies for modern markets: experiences of Sri Lanka and India,” in Cooperatives, Economic Democratization and Rural Development. Edward Elgar Publishing

Singh S (2022) Gender and producer organizations: case studies of performance and impact of all-women member PCs in Central India. Indian J Agric Econ 73:431–447. https://doi.org/10.63040/25827510.2022.03.005

Sirdey N, Lallau B (2020) How do producer organizations enhance farmers’ empowerment in the context of fair trade certification? Oxf Dev Stud 48(2):166–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2020.1725962

Srinithi (2022) Study of the impact of the members of Tamil Nadu banana producer company (TNBPC) in Tiruchirappalli district—a socioeconomic analysis. Econ Affairs (Calcutta). 67(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.46852/0424-2513.2.2022.21

Suresh V, Ss S (2024) Enabling and inhibiting factors of sustainability of Farmer’s Producers Organizations in India. Discover Sustain 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00527-5

Teresa H et al. (2018) Cooperation among Irish beef farmers: current perspectives and prospects in the context of new producer organization (PO) legislation. Sustainability 10(11):4085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114085

Thamban C, Jayasekhar S, Chandran KP, Rajesh MK (2020) Sustainability of Farmer Producer Organizations—the case of producer organizations involved in the production and marketing of ‘neera’ in the coconut sector. J Plant Crops 150–158. https://doi.org/10.25081/jpc.2020.v48.i2.6376

Trebbin A (2014) Linking small farmers to modern retail through producer organizations—experiences with producer companies in India. Food Policy 45:35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.12.007

Trebbin A, Hassler M (2012) Farmers’ producer companies in India: a new concept for collective action? Environ Plan A 44(2):411–427. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44143

Trivedi PK, Ali M, Satpal (2023) Farmer producer organizations in north India: potentials and challenges. Int J Rural Manag 19(3):379–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/09730052221107730

Mishra V, Ishdorj A, Tabares Villarreal E, Norton R (2024) Collaboration in agricultural value chains: a scoping review of the evidence from developing countries. J Agri Dev Emerg Econ. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-12-2023-0311

Muniyoor K, Pandey R (2024) Measuring the performance of farmer producer organizations using data envelopment analysis. J Glob Oper Strateg Sourc 17(1):74–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGOSS-05-2023-0049

Naspetti S, Mandolesi S, Buysse J, Latvala T, Nicholas P, Padel S, Van Loo EJ, Zanoli R (2021) Consumer perception of sustainable practices in dairy production. Agric Food Econ 9(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-020-00175-z

Arowosegbe OB, Alomaja OA, Tiamiyu BB (2024) The role of agricultural extension workers in transforming agricultural supply chains: enhancing innovation, technology adoption, and ethical practices in Nigeria. World J Adv Res Rev 23(3):2585–2602. https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2024.23.3.2962

Pant SC, Kumar S, Joshi SK (2024) Social capital and performance of farmers’ groups in producer organizations in India: examining the mediating role of self-efficacy. J Agribus Devg Emerg Econ 14(3):519–535. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-07-2022-0155

Prabhavathi Y, Kishore NTK, Siddaya, Ramachandra CT (2023) An analytical study on managerial competencies and business performance of Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs): a value chain perspective from India. Millennial Asia. https://doi.org/10.1177/09763996231200180

Prithika C, Anjugam M, Sivasankari B (2024) Deciphering the crux of women’s empowerment in agricultural value chains—a scoping review. Outlook Agri 53(4):302–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/00307270241267787

Singh S, Rana A, Sharma N, Kumar M (2022) A review on women agri-entrepreneurship: roles and opportunities in agriculture for sustainable growth in India. Shanlax Int J Arts Sci Humanit 10(2):56–67. https://doi.org/10.34293/sijash.v10i2.5117

Velten S, Jager NW, Newig J (2021) The success of collaboration for sustainable agriculture: a case study meta-analysis. Environ Dev Sustain 23(10):14619–14641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01261-y

Vilas-Boas J, Klerkx L, Lie R (2022) Connecting science, policy, and practice in agri-food system transformation: the role of boundary infrastructures in the evolution of Brazilian pig production. J Rural Stud 89:171–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.11.025

Falagas ME, Pitsouni EI, Malietzis GA, Pappas G (2008) Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J Publ Federation Am Soc Exp Biol 22(2):338–342. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF

Manaswi BH, Kumar P, Kar A, Perumal A, Jha G, Rao M, Prakash P (2019) Impact of Farmer Producer Organizations on organic chilli (Capsicum frutescens) production in Telangana. Indian J Agric Sci 89:1850–1854. https://doi.org/10.56093/ijas.v89i11.95313

Vijaya M, Kalaivani S (2021) Institutional support for tribal farmer interest groups in Erode district of Tamil Nadu, India J Appl Nat Sci 13:167–171. https://doi.org/10.31018/jans.v13iSI.2823

Funding

Open access funding provided by Symbiosis International (Deemed University).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SP—Idea generation of research, research design, Data collection and analysis, MM—content writing, interpretation, literature review, GP—data analysis, introduction, AS—data analysis, data analysis, interpretation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patil, S., Mehta, M., Pancholi, G. et al. Unveiling the dynamics of farmer producer organizations in India: a systematic review of status, challenges, and future directions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 758 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05063-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05063-9

This article is cited by

-

Transforming the Food System Through PACS: A Policy-Driven Path Toward Sustainable and Fair Value Chains

International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness (2025)