Abstract

The flourishing of health care relies on not only the quality of medical infrastructure but also legal and ethical frameworks, as well as the extent to which these are followed by physicians and nurses. This study aimed to evaluate the perceptions and practices of medical ethics and laws among healthcare professionals in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. A cross‐sectional study was conducted between May 10, 2023, and August 22, 2023, at five medical centres in Abu Dhabi. During the study period, self-administered surveys consisting of three sections were distributed to a random sample of physicians and nurses. The first section of the questionnaire included questions addressing the respondents’ demographic data, and the second and third sections assessed the respondents’ perceptions of and practices regarding adherence to the regulations governing healthcare providers. A total of 438 healthcare professionals participated in the study. Their mean age was 55.6 ± 11.3 years. Overall, the levels of perception and practice concerning medical ethics and healthcare laws were good. Specialist and junior physicians demonstrated higher levels of perception compared to junior nurses, with scores of 88.54% versus 65.25% and 78.85% versus 65.25%, respectively. The study reveals the need to revise the curricula of medical institutions to enhance health practitioners’ legal knowledge, attitudes and practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The law differs from ethics in terms of its origin and enforceability. Whereas laws consist of binding written rules enforced by governments or authorities, ethics are a set of unwritten principles and values developed by society over time and passed through generations. Another key difference between ethics and the law relates to the consequences of noncompliance: breaking laws can result in fines and sanctions, whereas ethics breaches do not attract fines or physical punishment (Nora, 2013; Bhattacharyya et al., (2022)). Despite such differences, a noticeable overlap exists between them, especially in the healthcare sector. Most legal rules began as moral codes before becoming binding written codes in society. The failure to observe ethical and legal rules can sometimes produce the same results because both involve the principles of confidentiality, veracity, fidelity, nonmaleficence and autonomy. Additionally, many cases raise serious legal and ethical questions about beneficence, conflicts of interest, quality of life, appropriate use of resources, the wishes of patients and professional responsibilities. Examples are plenty, such as asking patients to undergo unnecessary therapeutic procedures, ignoring the patient’s consent before non-emergency treatment and disclosing the patient’s data for the sole purpose of financial gain.

Compliance with ethical and legal rules is a vital issue in the healthcare context. It cannot be pinned down or reduced to a single form to be signed by the patient as a hospital formality (Trihastuti et al., (2020)). Compliance with codes of ethics and professional conduct is a comprehensive process that begins from the moment of entering the medical facility and continues throughout the whole treatment period in a way that ensures the patient’s involvement in the treatment plan. Such involvement cannot take place without the patient’s full consent, which is needed as an ethical and legal instrument demonstrating the right of the patient to receive an understandable explanation about the nature and consequences of treatment options so that they enjoy the right to accept or refuse any proposed treatment. Patients shall also have the right to retain reasonable control over who has access to their health records. Medical or biometric data of all patients must remain confidential unless expressly or impliedly authorised by the patient (Demirsoy & Kirimlioglu, 2016).

Effective communication between healthcare professionals and patients is also essential for ethical medical practice. Several studies have explored the impact of physician–patient communication on the quality and cost of medical care (Moslehpour et al., 2022; Świątoniowska-Lonc et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). These studies have found that stronger relationships between physicians and patients are associated with better patient outcomes. Physicians are thus advised to interact with their patients and offer them the necessary information for making informed decisions (Dahiyat et al., 2023). The extent to which physicians have a legal duty to provide clear and understandable instructions to their patients is yet undefined. What exactly would constitute mandatory disclosure remains unclear in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) healthcare setting. The UAE has recently undergone a significant legislative reform to ensure the continuous development of health care and provide high-quality care and treatment in line with international best practices. The most important initiatives governing the general UAE’s health sector are Federal Law No. 13 of 2020 on Public Health, Federal Law No. 5 of 2019 on the Regulation of the Practice of the Human Medicine Profession and Federal Decree-Law No. 4 of 2016 on Medical Liability. This does not comprise the entire UAE framework affecting healthcare providers. Other laws and regulations play a vital role in this field, such as Federal Law No. 2 of 2019 on the Use of Information and Communications Technology in Healthcare, Ministerial Resolution No. (1448) of 2017 concerning the Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct for Health Professionals and Ministerial Resolution No. 14 of 2021 on the Patient’s Rights and Responsibilities Charter. According to these laws and regulations, healthcare providers must treat patients with respect and dignity and preserve the confidentiality of all patients’ records. Healthcare providers must also prioritise their patients’ interests over their own and limit their procedures and prescriptions to the extent necessary for healing.

This study aimed to assess healthcare professionals’ understanding, attitudes and behaviours concerning medical ethics and laws in the UAE.

Materials and methods

Study settings and design

This cross-sectional observational study measured the perception and practices of healthcare ethics and laws among doctors and nurses practising in Abu Dhabi, UAE. The research tool for data collection was a self-administered questionnaire, divided into three parts. The first part included questions about the respondents’ demographic data, such as age, gender, years of experience, level of education and position in the hospital. The second and third parts contained questions that assessed the respondents’ attitudes and practices concerning medical ethics and laws, respectively.

Study participants and eligibility criteria

The study population comprised physicians from all specialties and nurses working in the five selected private-sector centres and hospitals, with at least 6 months of professional experience. The study excluded health professionals with less than 6 months of experience, those who were absent from work at the hospital for various reasons, and those who held managerial or administrative positions at the centres and hospitals.

Research instrument development and validation

The questionnaires used in this study were developed based on a review of the literature related to patients’ rights and health professionals’ perceptions, attitudes and practices concerning ethics and laws governing healthcare settings (Karasneh et al., 2021; Adhikari et al., 2016; Anup et al., 2014; Tegegne et al., 2022). The researchers used existing questionnaires from the relevant literature and modified them to fit the UAE context and comply with the study objectives. Subsequently, three experts specialising in health law and ethics meticulously evaluated the draft, providing valuable insights into the applicability and thoroughness of its items. Their recommendations were incorporated to enhance the questionnaire’s accuracy and alignment with the research objectives.

Pilot testing

The questionnaire was pilot-tested by 43 healthcare professionals between January 15, 2023, and February 26, 2023. The data generated by participants in the pilot test was not included in the final analysis. Out of the 43 respondents, 21 completed the survey satisfactorily, and no significant issues were reported. The pilot test results were used to assess the questionnaire’s validity and reliability and determine the appropriate sample size for the final questionnaire.

Research instrument sections

The questionnaire for this study was divided into three sections.

-

Demographic information: This section comprised five questions aimed at gathering details about respondents’ demographics: age, gender, professional role (such as specialist physician, junior physician or junior nurse), educational background and years of professional experience.

-

Perceptions of medical ethics and laws: This section consisted of eight questions designed to assess the perceptions of healthcare professionals concerning medical ethics and laws.

-

Practices concerning medical ethics and laws: The third part encompassed 14 questions focused on investigating the real-life practices of healthcare professionals regarding medical ethics and laws.

The assessment of perceptions of medical ethics and laws was based on an eight-item 3-point Likert scale (1 for Disagree, 2 for Neutral and 3 for Agree). The Agree response was considered optimal, receiving a single score, and the perception score was determined by summing all points. Similarly, practices concerning medical ethics and laws were assessed using a fourteen-item 5-point Likert scale (1 for Never, 2 for Rarely, 3 for Sometimes, 4 for Often and 5 for Always). The raw scores of 1 to 5 were computed for each respondent by summing the grading of the 14 items.

Questionnaire scoring

Positive perception and practice scores for medical ethics and laws were defined by calculating the median scores. The established threshold for a positive perception was a median score of 6 or above. A practice median score of 58 or above identified individuals with commendable practices, whereas those scoring less than 58 did not meet the criterion for good practices.

Sample size calculation

The pilot study provided crucial insights into determining the sample size for the primary research. Eighty-eight per cent of the pilot study’s questions were returned, with the pivotal item being, 'I frequently comply with legal regulations governing healthcare practices in my jurisdiction.' Approximately 80% of participants responded affirmatively. Employing a 5% alpha level, the study aimed for a 95% confidence interval (CI), with a maximum CI width of 10% and precision (D) set at 5%. Considering a potential non-response rate of around 20%, the optimal sample size was determined to be 431 subjects.

Data confidentiality

We implemented several measures to safeguard participant privacy throughout our study. The survey responses were collected anonymously, with no requirement for participants to provide personal information. Access to the data was restricted to the study team, who maintained exclusive access to password-protected files. Physical copies of the data were securely stored in a locked cabinet.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26. Frequencies and percentages were used to summarise qualitative factors, and ± standard deviation (±SD) was employed to analyse quantitative variables. To explore cross-group differences for the quantitative variables, one-way ANOVA, non-parametric tests and unpaired student t-tests were employed. Normality assumptions for continuous variables were assessed through visual inspection of typical Q-Q plots or by conducting the Shapiro–Wilk test, considering a normally distributed continuous variable if P > 0.05. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to determine the factors influencing the perceptions and practices of healthcare professionals regarding medical ethics and laws. Statistical significance was set at P-values less than 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

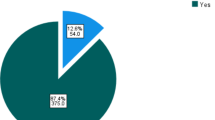

A total of 438 healthcare professionals participated in the study. Their mean age was 32.5 ± 8.2 years. Among the participants, 37% (n = 162) were male, and 63% (n = 276) were female. In terms of professional roles, 16.4% were specialist physicians, 60.7% were junior physicians and 22.8% were junior nurses. For more details, see Table 1.

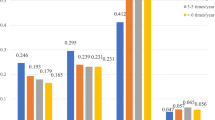

Healthcare professionals’ perceptions and practices concerning medical ethics and laws

The average perception score for medical ethics and laws was 77.3% (95% CI 75.6%, 79%). The average practice score for medical ethics and laws was 81.5% (95% CI 80.4%, 82.5%). In general, the level of perception and practice regarding medical ethics and laws was good. Specialist physicians and junior physicians had higher scores in the perception of medical ethics and laws compared to junior nurses: 88.54% versus 65.25% and 78.85% versus 65.25%, respectively. Additionally, participants with more years of experience demonstrated better scores in the perception of medical ethics and laws compared to those with less experience (P = 0.001). Statistically significant associations were found between the practice of medical ethics and laws and various factors. Higher scores were observed among women (P = 0.007). Specialist physicians and junior physicians scored higher compared to junior nurses (P < 0.001). Additionally, participants with more years of experience scored higher than those with less experience (P = 0.002; Table 2). The results for each item related to perception and practice are shown in Tables 3, 4.

Factors associated with perception and practice concerning medical ethics and laws

Table 5 presents the results of the multivariate regression analysis of the factors associated with perceptions and practice regarding medical ethics and laws.

Better perception scores were observed in older participants (OR 1.127; 95% CI 1.03, 1.23), specialist physicians (OR 28.21; 95% CI 8.94, 33.02), junior physicians (OR 3.18; 95% CI 1.80, 5.63) and those with 6–10 years of experience (OR 2.20; 95% CI 1.11, 4.39), 11–20 years of experience (OR 2.22; 95% CI 1.07, 4.58) and more than 30 years of experience (OR 12.46; 95% CI 2.66, 58.45).

Better practice scores were observed in women (OR 2.52; 95% CI 1.33, 4.76), specialist physicians (OR 2.54; 95% CI 1.76, 4.73), junior physicians (OR 1.69; 95% CI 1.30, 3.37), and those with 20–30 years of experience (OR 9.95; 95% CI 1.30, 22.12) and more than 30 years of experience (OR 4.36; 95% CI 1.21, 15.84).

Discussion

This study examined the knowledge and attitudes of health professionals regarding patients’ confidentiality, wishes, consent and other legal aspects of healthcare in the UAE. Most respondents had sound knowledge and positive attitudes concerning medical ethics and laws governing patients’ care autonomy and decision-making. Despite the significant differences between physicians and nurses in knowledge and practice concerning patient confidentiality, the results of this study are still slightly better than those reported in some others (Adeleke et al., 2011; Bhardwaj et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2008; Beltran-Aroca et al., 2016), where only a small percentage of healthcare professionals were aware of their confidentiality duty and its role in the healthcare context. Such promising results might be due to a reasonable number of patient visits at the UAE hospitals compared with that in resource-limited countries, where many healthcare professionals suffer from job-related challenges such as low salaries, inadequate facilities, staff shortages, poor management, deficiencies in internal control and long working hours. These results could also be because confidentiality is considered a basic human right and constitutes a fundamental part of the UAE legislation.

The fact that most participants strongly disagreed that the patient’s wishes should always be adhered to should come as no surprise since UAE law prevents abortion, suicide and euthanasia and encourages a physician’s duty to protect human life from the time of conception. Despite the significant differences in the knowledge of laws and ethics between senior physicians on the one hand and junior nurses and resident physicians on the other, the results of this study are still more positive than those observed in another study in Barbados (Hariharan et al., 2006), where 52% of senior medical staff knew little or nothing of the laws pertinent to their work. Similarly, the result of this study is better than those recorded in others conducted in India (Akoijam et al., (2009)) and Pakistan (Nazish et al., 2014), where a significant number of physicians lacked in-depth knowledge of medical ethics and had no knowledge of laws relating to their medical work.

In contrast to previous studies conducted in Korean and Jordanian hospitals (Kim et al., 2002; Abdulrazeq et al., 2019), where only a small proportion of healthcare professionals were familiar with informed consent as a legal and ethical requirement, this study demonstrates that most healthcare professionals in the UAE were well-informed about patients’ rights to autonomy and informed consent. This may be because UAE legal frameworks have early codified the ethical principles relating to informed consent in detail so that such principles have formed the basis for a suite of policies, codes and procedures that guide and inform healthcare workers at UAE hospitals. Notably, however, significant differences were observed between senior physicians and other healthcare practitioners concerning their legal and ethical knowledge and practices. This highlights the need to implement better training and education programs to fill these gaps and improve the overall quality of healthcare services provided at hospitals in the UAE. Maybe it is time to review and develop the curricula of medical colleges at the undergraduate level to focus more on healthcare ethics and laws.

Maybe, too, the time has come to establish ethical guidelines for regulating the relationship between healthcare providers and the pharmaceutical industry. This is particularly needed in the context of the UAE health setting where no clear policy regulates the ethical appropriateness of accepting gifts from the pharmaceutical industry. Not all hospitals and medical centres have implemented or updated their internal policies to comply with the 2017 federal Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct for Health Professionals, which strictly prohibits health professionals from accepting any gifts, advantages or financial benefits from any party for providing health services or prescriptions or using medical products in treatment. Despite the proportion of physicians who had received gifts from the pharmaceutical industry, the results of this study are still much better than those reported in another conducted in Saudi Arabia, where more physicians (66–80%) declared that they received gifts from pharmaceutical companies (Alosaimi et al., 2013). The results of our study are also better than those recorded in another in Lebanon, where 70.4% of respondents reported receiving gifts from representatives of pharmaceutical companies. Only 40.0% of those who accepted gifts believed that it was unethical, and about half were uncertain whether the Lebanese Code of Medical Ethics permitted gift acceptance (Shaarani et al., 2024).

Two probable scenarios can construe and explain the results of this study regarding receiving gifts from industry. Either UAE law leaves this issue to the medical centres and hospitals to make or update their own policies concerning this issue, or it intentionally ignores establishing guidelines or standards for ethical relationships between medical practitioners and industry, preferring to leave this to the physician’s discretion. A specific percentage of the physicians who were surveyed seemed to believe that receiving gifts from industry is ethically acceptable as long as it does not negatively affect patients’ interests.

An interesting finding of our study was that years of experience could substantially influence nurses’ and physicians’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding ethics in their professional duties. The physicians’ and nurses’ attitudes towards medical ethics became more positive with increased years of experience. This result corroborates those of other studies (Elger, 2009; Asare et al., 2022) showing how personal variables such as length of experience, level of education and professional qualification tend to be associated with the knowledge and attitude of nurses and physicians regarding medical ethics and laws.

Limitations and future research directions

The study has some limitations. First, self-administered questionnaires inherently come with limitations, notably the risk of social desirability bias, which could potentially impact the accuracy of data concerning ethical behaviours. To mitigate this concern, we took several measures. We assured participants of anonymity and confidentiality, meticulously crafted the questionnaire to minimise bias, subjected it to evaluation by experts in health law and ethics, and conducted pilot testing to enhance its effectiveness and reliability. Second, achieving a sample that accurately mirrors the diverse composition of healthcare workers poses challenges due to various factors, such as sampling issues and dynamic differences within this community. To address this challenge, we employed random participant selection, enabling us to include a wide-ranging sample of patients from five distinct private-sector hospitals and medical institutions in Abu Dhabi. Although we recognise the complexities involved, including the inherent heterogeneity in healthcare worker professional roles and demographics, we made concerted efforts to ensure the representativeness of our sample.

The scope of the study was confined to the questions that were part of the questionnaire, which may not encompass all ethical or legal scenarios. Other related factors were not considered. Another limitation of the study is its small sample size, which was not sufficiently representative. The research focused on five medical centres in Abu Dhabi, which may not accurately reflect the healthcare situation in other Emirates of the UAE. Consequently, the findings cannot be generalised to the broader UAE healthcare context, and no conclusions can be drawn regarding the entire population. Furthermore, this study was limited to physicians and nurses in a single geographic area. As a result, the outcomes may not be applicable to other regions or countries. Therefore, we recommend conducting further research on this topic, involving participants from other regions, and identifying the most effective ethics education programmes or training to help healthcare professionals better address ethical challenges in clinical settings. Additionally, expanding the research to include the perspectives of other healthcare professionals—such as pharmacists and medical laboratory technicians—would provide a more holistic view of health care.

Another promising avenue for future research is exploring healthcare professionals’ perceptions of ethical and legal challenges related to emerging medical technologies, such as artificial intelligence robotics, stem-cell therapy, in vitro fertilisation, egg and sperm donation, remote patient monitoring and telemedicine, in the UAE. Investigating these areas could help healthcare systems proactively address new ethical dilemmas and develop appropriate guidelines to manage these evolving technologies.

Conclusion

The study found that healthcare practices in the UAE honoured patients’ rights to informed consent, autonomy and confidentiality. It also revealed that the experience level of medical staff had a significant impact on their legal awareness and ability to address ethical dilemmas in the healthcare context. Although most physicians and nurses exhibited adequate legal and ethical awareness and attitudes related to healthcare, a small proportion showed deficiencies in certain aspects of their practice, particularly those with fewer years of experience. If maximising utility is our primary concern, providing more training to address these deficiencies is essential to better prepare medical staff for managing ethical dilemmas and enhancing transparency and accountability in clinical practice. Additionally, requiring healthcare professionals to complete ongoing medical education in medical law is essential as part of the licensing and renewal process. This would equip them to better handle ethical and legal challenges.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

References

Abdulrazeq F, Al-Maamari A, Ameen W, Ameen A (2019) Knowledge, attitudes and practices of medical residents towards healthcare ethics in the Islamic Hospital, Jordan. Yemen J Med Sci 13(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.20428/yjms.13.1.a1

Adeleke IT, Adekanye AO, Adefemi SA et al. (2011) Knowledge, attitudes and practice of confidentiality of patients’ health records among health care professionals at Federal Medical Centre, Bida. Niger J Med 20(2):228–235. PMID:21970234

Adhikari S, Paudel K, Aro AR et al. (2016) Knowledge, attitude and practice of healthcare ethics among resident doctors and ward nurses from a resource poor setting, Nepal. BMC Med Ethics 17:68–76

Akoijam BS, Rajkumari B, Laishram J, Joy A (2009) Knowledge and attitudes of doctors on medical ethics in a teaching hospital, Manipur. Indian J Med Ethics 4:7

Alosaimi F, Alkaabba A, Qadi M et al. (2013) Acceptance of pharmaceutical gifts. Variability by specialty and job rank in a Saudi healthcare setting. Saudi Med J 34(8):854–860

Anup N, Kumawat H, Biswas G et al. (2014) Knowledge, attitude & practices regarding ethics & law amongst medical and dental professionals in Rajasthan – a questionnaire study. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 13(5):102–109

Asare P, Ansah EW, Sambah F (2022) Ethics in healthcare: knowledge, attitude and practices of nurses in the Cape Coast Metropolis of Ghana. PLoS One 17(2):e0263557. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263557

Beltran-Aroca CM, Girela-Lopez E, Collazo-Chao E et al. (2016) Confidentiality breaches in clinical practice: What happens in hospitals? BMC Med Ethics 17(1):52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-016-0136-y

Bhardwaj A, Chopra M, Mithra P, et al. (2014) Current status of knowledge, attitudes and practices towards healthcare ethics among doctors and nurses from Northern India—a multicentre study. Pravara Med Rev 6(2)

Bhattacharyya R, Gundugurti P, Kondepi S et al. (2022) Ethics and law. Indian J Psychiatry 64(7):7. https://doi.org/10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_726_21

Dahiyat E et al. (2023) Exploring the factors impacting physicians’ attitudes toward health information exchange with patients in Jordanian hospitals. J Pharm Policy Pr 16:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-023-00514-7

Demirsoy N, Kirimlioglu N (2016) Protection of privacy and confidentiality as a patient right: physicians’ and nurses’ viewpoints. Biomed Res 27:1437–1448

Elger BS (2009) Factors influencing attitudes towards medical confidentiality among Swiss physicians. J Med Ethics 35(8):517–524. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2009.029546. PMID:19644012

Hariharan S, Jonnalagadda R, Walrond E et al. (2006) Knowledge, attitudes and practice of healthcare ethics and law among doctors and nurses in Barbados. BMC Med Ethics 7:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-7-7

Karasneh R et al. (2021) Physicians’ knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes related to patient confidentiality and data sharing. Int J Gen Med 14:721

Kim DS et al. (2002) Patient–nurse collaboration in nursing practice: a Korean study. J Korean Acad Nurs 32(7):1054–1062

Kim YS, Yoo MS, Park JH (2008) Korean nurses’ awareness of patients’ rights in hospitals. Korean J Med Ethics 11(2):191–200. https://doi.org/10.35301/ksme.2008.11.2.191

Moslehpour M, Shalehah A, Rahman FF, Lin KH (2022) The effect of physician communication on inpatient satisfaction. Healthcare 10(3):463. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030463

Nazish I, Imran I, Masood J et al. (2014) Health ethics education: knowledge, attitudes and practice of healthcare ethics among interns and residents in Pakistan. J Postgrad Med Inst 28(4):383–389

Nora LM (2013) Law, ethics and the clinical neurologist. In: Bernat JL, Beresford HR, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol 118, Amsterdam: Elsevier p 63–78

Shaarani I, Hasbini J, Farhat R et al. (2024) Beliefs and practices of physicians in Lebanon regarding promotional gifts and interactions with pharmaceutical companies. East Mediterr Health J 30(2):116–124. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.24.027. PMID:38491897

Świątoniowska-Lonc N, Polański J, Tański W et al. (2020) Impact of satisfaction with physician–patient communication on self-care and adherence in patients with hypertension: cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 20:1046. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05912-0

Tegegne MD, Melaku MS, Shimie AW et al. (2022) Health professionals’ knowledge and attitude towards patient confidentiality and associated factors in a resource-limited setting: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Ethics 23:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-022-00765-0

Trihastuti N, Putri S, Widjanarko B (2020) The impact of asymmetric information in medical services: a study in progressive law. Syst Rev Pharm 11(12):850–855

Wang YF, Lee YH, Lee CW et al. (2022) Patient–physician communication in the emergency department in Taiwan: physicians’ perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res 22:152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07533-1

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the participants who took part in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EAD and FE designed and conceptualised the study. AAJ and FE were responsible for data collection. AAJ and EAD were responsible for data entry, analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed to manuscript development. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Research Ethics Committee of Al Ain University, United Arab Emirates (Approval No: COP/2023/24) on 7 January 2023. All procedures involving human participants were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees, and with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study protocol, including data confidentiality, anonymity, and informed consent procedures, was thoroughly reviewed and approved prior to commencement of data collection.

Informed consent

The cover page of the questionnaire clearly outlined the study’s objectives and assured participants of confidentiality. By voluntarily completing the survey, participants provided their informed consent. The online survey was administered between January 10 and January 31, 2023, and consent was obtained at the time of survey access through an online information sheet embedded on the first page of the questionnaire. Participants were informed that completion of the questionnaire indicated their agreement to participate, and that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential, to be used solely for research and publication in aggregated form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dahiyat, E.A.R., Jairoun, A.A. & El-Dahiyat, F. Perceptions and practices of medical ethics and laws among health professionals in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 804 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05125-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05125-y