Abstract

Cultural evolution is driven by how we choose what to consume and share with others. A common belief is that the cultural artifacts that succeed are the ones that balance novelty and conventionality. This “balance theory” suggests that people prefer works that are familiar, but not so familiar as to be boring; novel, but not so novel as to violate the expectations of their genre. We test this idea using a large dataset of fanfiction, a unique data source that mitigates many common critical shortcomings in the study of creative works. We apply a multiple regression model and a generalized additive model to examine how the recognition a work receives varies with its novelty, estimated through a Latent Dirichlet Allocation topic model, in the context of existing works. We find the opposite pattern of what the balance theory predicts—overall success declines almost monotonically with novelty and exhibits a U-shaped instead of an inverse U-shaped curve. This puzzle is resolved by teasing out two competing forces: sameness attracts the masses whereas novelty provides enjoyment. Taken together, even though the balance theory holds in terms of expressed enjoyment, the overall success can show the opposite pattern due to the dominant role of familiarity to attract the audience. Under these two “forces”, cultural evolution may have to work against inertia—the appetite for consuming the familiar—and may resemble a punctuated equilibrium, marked by occasional leaps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The culture industry may strive constantly for the latest hit ("The culture industry: Enlightenment as mass deception”, 2007), but even with extensive research and strong financial incentives, it remains difficult to predict the success of a film, book, or television series (De Vany, 2003). A widely adopted hypothesis suggests that successful creative works are a combination of, or balance between, convention and innovation. According to this theory, popular works are different from previous works and their peers, but not too different. For example, songs with a non-zero, but non-extreme, level of differentiation are more likely to be on the top of the Billboard’s Hot 100 charts (Askin and Mauskapf, 2017; Hargreaves, 1984), movies balancing familiarity and novelty have higher revenues (Sreenivasan, 2013), and visual metaphors in ads work best when they have mild incongruity (Mohanty and Ratneshwar, 2016). In scientific publications, the highest-cited papers are argued to be grounded on mostly conventional, but partly novel combinations of previous works (Uzzi et al. 2013). However, a significant amount of this research deals with cultural products in environments where their reception is strongly influenced by factors beyond intrinsic ones such as content, style, subject, genre, or length. In this work, we identify an unusually rich dataset of fanfiction that allows us to isolate the effect of novelty, and test the balance theory while controlling for external effects.

Fanfiction draws on plots and characters from prior narratives to create new stories and alternate timelines. Generally considered to originate from zines created by Star Trek fans in the 1960s (Helmke Library, 2024), it is nowadays usually created by fans and published on the Internet (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2024). Fanfiction serves as a mediator for participatory sense-making within the bounds of a canon (the original work from which characters and plots are drawn) (Jaegher and Paolo, 2007). This participatory sense-making engenders a dynamic co-creative relationship between fans and transforms narratives in ways that reflect diverse interpretations, desires, and cultural or experiential contexts (Cheng and Frens, 2022; Popova, 2019; Thomas, 2011). Despite being based on a canonical work, fanfiction is one of the most innovative practices in contemporary culture, turning people who would, ordinarily, only be consumers, into creators (Thomas, 2011). It is playful, transformative, and transgressive (Barnes, 2015; Tosenberger, 2008). An enthusiast of the Harry Potter series may write a new adventure for Hermione and Harry; a fan of the television show Buffy the Vampire Slayer may write a story in which Willow’s girlfriend has a different fate. Fans of Sherlock Holmes, for example, have written stories in which Holmes and Dr. Watson fall in love, and Watson, by magical means, gestates the couple’s baby. Examples like these abound, and fanfiction communities (“fandoms”) are far from conservative, often subverting, as well as extending a canonical work. This production goes along with the interchangeability of the creator and consumer roles: an author also reads and comments on other fanfiction (Eiji and Steinberg, 2010). These interactions happen on time scales of hours, even minutes, and the rapidity of the feedback process allows for rapid change and selection, making them ideal laboratories for the study of cultural evolution.

The practice of fanfiction writing is global and brings together individuals from multiple countries and cultures (Vazquez-Calvo et al. 2019). People write fanfiction to express their passion for the canon, to find erotic engagement (Busse, 2017), to transform hetero-normative narratives (Floegel, 2020), and to seek and build communities. Since the 1990s, fan studies have delved into multiple, often contradicting aspects of fanfiction and fandom; for example, the foundational text by Jenkins (2012) advocated for fanfiction as a way for fans to subvert power and alter narratives created by large franchises. At the same time, Jones points out that the free labor of fans can also be exploited by large corporations when fan work is merchandised (Jones, 2014). Later studies (Chin and Morimoto, 2013) focused on the heterogeneity among fans and how their individual background, experiences, sexuality, etc., shape their activities in fandoms. Some scholars also paid attention to the “toxic” practices in fandoms, such as gender and racial discrimination, trolling and bullying, and anti-fandoms (Chin, 2018; Harman and Jones, 2013; Proctor et al. 2018). However, most of these works view fanfiction as an inseparable part of an individual’s overall fan activity, which allows researchers to gain insights into fan communities and fan culture, instead of looking at the literal value of any specific fanfiction on their own merits (Geraghty et al. 2022; Thomas, 2011).

A few existing studies have attempted to quantitatively characterize the relationship between the intrinsic quality of fanfiction and its reception. Jacobsen et al. have found that fanfiction has an overall different writing profile compared to published literature, but the more successful fanfiction shares similar qualities to published novels (Jacobsen et al. 2024). Nguyen et al. found that readers prefer longer sentences and a more diverse vocabulary, and a different genre than the canon in the Supernatural fandom (Nguyen et al. 2024). Sourati Hassan Zadeh et al. found that fanfiction with different character graphs and emotional arcs compared to the canon tends to be more popular (Sourati Hassan Zadeh et al. 2022). However, these works utilize relatively small datasets featuring only one or a few fandoms and examine multiple features that may influence a fanfiction’s reception at the same time.

Here we focus on how an isolated dimension—the novelty of fanfiction—affects its popularity. The nature of fanfiction allows us to mitigate a number of common confounds in the study of creativity and what people enjoy. First, as a “democratized” genre (Pugh, 2005), the entrance criteria for fanfiction are extremely low. Anyone with internet access can publish their fanfiction writing online without the need to go through editors or publishers, meaning that many works that would traditionally not be considered for publication can now be accessed by readers. Second, fanfiction is usually shared within a fandom’s community with no advertisement or promotions (Campbell et al. 2016; Wikipedia contributors, 2018); a work’s success is therefore largely uninfluenced by top-down interventions, such as advertising campaigns, which can distort its reception. In addition, most fanfiction works are freely available on the Internet, so the price is not a confounding factor. In fact, many fan communities such as AO3 (as we discuss below) are averted to commercial use of fan works, so creators often pursue recognition from readers as their motivation, instead of monetary rewards. Third, works in the same fandom are created within the same context, and have similar subjects, characters, and settings to each other. As in genres of literary production, variations between works occur in a recognizable space, allowing us to talk about their novelty while controlling for other factors. Because fanfiction is available in plain text and in remarkably large volumes, systematic, statistical approaches are possible. Finally, our data is rare in that it records both the viewership (number of hits) and the enjoyment (number of Kudos; see the “Methods” section), allowing a deep look into the complicated process of audience feedback.

Leveraging this unique data source, we explore how familiarity or novelty in a piece of writing is related to its reception. It has been widely accepted that people enjoy familiarity (Mull, 1957); This preference is found in a wide variety of domains. Humans, for example, find faces that are close to the average, and therefore more familiar and more attractive. The effect extends to images of birds and automobiles (Halberstadt and Rhodes, 2003), and even to arbitrary visual patterns: a classic psychological experiment by Zajonc (1968) showed that mere exposure to certain stimuli can increase people’s preference for it, even when they are not aware of the exposure (Bornstein, 1989; Kunst-Wilson and Zajonc, 1980).

These works lead naturally to the idea that successful cultural products leverage familiarity. Repetition has long been a central feature of music and poetry (Huron, 2013), and the trend persists in contemporary popular culture, where new releases are often adaptations, remakes, and remixes of existing works (Manovich, 2007). Marvel and DC Comics have successful movies based on familiar characters now decades old, including sequels, prequels, and reboots. The origin story of Spider-man provides an extreme case; this single narrative has been re-made, in slightly different forms, in three movies in the last eighteen years: Spider-Man (2002), The Amazing Spider-Man (2012) and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018), where all three movies achieved high recognition. This repetition of the “canon” became the main theme of the recent Spiderman movie Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. In 2021, eight of the ten highest-grossing movies were adaptions, sequels, remakes, or parts of a movie universe rather than de novo creations (IMDbPro, 2021); in 2022, nine of ten were (IMDbPro, 2022).

Repetition, however, is not all. Extremely novel cultural products, sometimes, also enjoy huge successes. Popular music in the 20th Century is characterized not only by the stability of genres but also by high rates of turnover and the emergence of new ones (Mauch et al. 2015). Widely imitated genres such as jazz and rock n’ roll music quickly grew into global dominance since their creation. In the film industry, successful but novel products include not just new characters and situations, but also new forms of cinematography, such as in Star Wars and Avatar. This poses a challenge for those who study cultural evolution, which must account at once for both the known psychological preferences for what is familiar, and the success of these famous counterexamples.

‘Balance’ theory of liking

To reconcile this apparent conflict, the balance theory proposes that creative works that combine the right amount of novelty and familiarity bring maximum enjoyment. In psychology, this idea is captured in the Wundt–Berlyne curve, an inverted-U curve with an optimal amount of novelty for hedonic values at an intermediate position (Berlyne, 1970); similar accounts are found in the business and marketing literature where it is known as Mandler’s hypothesis (Meyers-Levy and Tybout, 1989), and in organizational theories as the optimal distinctiveness hypothesis (Zuckerman, 2016).

Although much research has attempted to verify this theory using cultural data (Askin and Mauskapf, 2017; Hargreaves, 1984; Mohanty and Ratneshwar, 2016; Sreenivasan, 2013; Uzzi et al. 2013), they are often complicated by external factors including price, advertisement, and media coverage. It has been shown that in an artificial environment, social influence can often override a song’s quality and make it popular (Salganik et al. 2006; Salganik and Watts, 2008). Indeed, belief in an inverted U can be self-fulfilling: a scientific funding agency or a film company may choose to give critical funding to a work of incremental novelty in the expectation that it will succeed. In addition, the modern culture industry is concerned with multiple metrics for success; a movie that begins with a high box office may not earn a good rating among its audience, and a highly celebrated work may not have an equally successful sequel. The complex interactions between consumers, cultural products, and the market are difficult to disentangle.

Using our unique data source of fanfiction, we attempt to address this question while avoiding many such confounding factors as we discuss above. We use a topic model (latent Dirichlet allocation; LDA) to characterize the novelty of fanfiction (a term-level novelty measurement showed similar results; see Supplementary Information). A work is evaluated with respect to the existing work in the same fandom; we consider it to be more novel if it is more distinct from the other fiction published during the previous time period in the feature space (see the “Methods” section). The success of fanfiction is measured by four variables: hits (number of views), “Kudos” (similar to a “like” on social media), comments, and bookmarks. Further metadata allows us to control for other effects.

Our results show an almost monotonically decreasing relationship between a fiction’s novelty and its success. Furthermore, our regression models suggest that the relationship between success and novelty is U-shaped, rather than inverted-U-shaped. Readers seem to prefer fanfiction that gives them a sense of familiarity, and we find no limit to their appetite for “more of the same”; at the same time, high-novelty seems to have some chance to achieve success. However, combining novelty and familiarity is rarely rewarding. As we will explain below, this result that seemingly contradicts the balance theory can be, however, resolved by teasing our two factors in play: even if the novelty–enjoyment relationship may still follow the balance theory, the familiarity’s attractiveness dominates the overall success. Taken together, the relationship between novelty and enjoyment follows the traditional “inverted U-shape” account, but the relationship between novelty and attraction reverses it.

Data and methods

We draw our data from the online fanfiction archive Archive of Our Own (AO3; http://archiveofourown.org/). AO3 is an online archive that allows users to upload their fanfiction and organize them based on fandoms and tags. Unlike many smaller fanfiction websites that focus on specific fandoms, AO3 is open to any fandom and allows another fanfiction website to migrate its data entirely to the platform. Established in 2009, it has become one of the largest fan communities, with more than 7.5 million users and 13.8 million works at its 15th anniversary in November 2024 (AO3News, 2024). According to a survey published in 2023 (Rouse and Stanfill, 2023), 53.8% of users on AO3 identify themselves as women. Notably, over 40% of users identify themselves as non-cisgender and over 86% as non-straight.

As an open-source website maintained by the nonprofit organization Organization for Transformative Works, AO3 states its purpose as to preserve and provide access to fanworks and is defensive against commercial exploitation of them (Organization for Transformative Works, 2024). Compared to another similar popular website, Fanfiction.net, which does not allow explicit material, real-person fiction, and other certain genres (FanFiction, 2008), AO3 has fewer restrictions and hosts a wider range of content. In addition, AO3’s moderators help with arranging tags and responding to users’ requests, but they do not screen for the quality of posts. A work will not be checked by a moderator unless it is reported by a user; and even in such cases, a work will only be removed if it contains a commercial promotion, plagiarism, harassment to other users, or violates AO3’s content policy in other ways (Archive of Our Own, 2024). As AO3 tries to include a maximum range of fanworks (Archive of Our Own, 2024), a work will not be censored only because someone finds it offensive, resulting in a wide range of topics and genres. Because of these advantages, AO3 has become the dominant venue to publish and read fanfiction works. While fan communities are also vibrant (or used to be vibrant) on other platforms such as LiveJournal, Tumblr, and Wattpad, the organized structure of AO3 makes it more accessible to collect data.

A Python script was used to download fanfictions and their metadata from AO3 in our selected fandoms (see below) in March 2016.Footnote 1 The works we collected span the time range from 2009 to 2016 (see Supplementary Information). However, as works are constantly added, removed, and edited on this platform, our data only serves as a then-snapshot of the evolving medium.

For a representative sample of fanfiction on AO3, we conducted the following steps for data collection: (1) Include all Mediums: AO3 classifies the fandoms based on the formats of the canons, such as movies, TV shows, books, anime & manga, and musicals. To allow representation of different mediums, we collect data from the top five fandoms with the highest number of works in each of these categories. While this choice leaves out the less popular fandoms, it ensures that we collect a large amount of data for analysis. As new works are constantly added to fandoms, the top five fandoms change over time. What we include only reflects the most popular fandoms at the time of our data collection. (2) Control for over-representation of fandoms: As fandoms on AO3 may have significant overlaps, to avoid over-representing certain fandoms, we only include the parent fandom and exclude their subset fandoms. For example, we keep Marvel but exclude The Avengers, because The Avengers is a part of the Marvel Universe. Works in the The Avengers fandom, as well as in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and Marvel comics that are not cinematized, are therefore all collected under the umbrella Marvel fandom. We also exclude broad fandoms that contain many separate subjects, as they may appear more popular because they include an entire genre instead of specific fandoms. For example, K-pop contains fanfiction about over 300 different Korean pop bands. For clarity, this would be similar to creating a fandom “Comic Books” which would include separate (and competing) Marvel and DC Comic fandoms. (3) Filter out fanfiction that fall under other certain criteria: We exclude cross-over fanfiction, which features characters or elements from more than one fandom. We only include fanfiction written in English. To control for the effects of very short works, we only analyze the subset of fiction with more than 500 words.

In total, we collected 671,908 pieces of fanfiction in 23 fandoms from 124,305 authors. Figure S1a shows the number of works in each of the 23 fandoms; Marvel, Supernatural, and Sherlock Holmes are the largest. Figure S1b shows the volume of works produced over time. AO3 was established in December 2009 and experienced rapid growth beginning in 2012. Because the works timestamped earlier than the start date might be migrated from other platforms, and may not correctly reflect the status of the archive, we only run our analysis using those published in January 2010 or later.

The success of fanfiction is measured by its hits, Kudos, comments, and bookmarks. While the number of hits is the most direct metric for popularity, the number of Kudos is a clearer signal that readers enjoy the fiction. A reader can also comment on a fiction or bookmark it to read later. The comments and bookmarks therefore signal the recognition or engagement from readers, although they depend on multiple motivations, and are less directly associated with popularity.

Figure S2 shows the distribution of the hits, Kudos, comments, and bookmarks on a logarithmic scale. Like many other measurements of popularity, they exhibit fat tails, with a small number of works receiving the majority of attention and most receiving little or none. Also note that there are outliers that achieved extreme recognition in terms of hits and Kudos. In the analysis, we log-transform the response values, a common practice for similar data such as citations (Thelwall and Wilson, 2014). This practice has been argued to reduce the potential bias when performing regression and other statistical analyses (Thelwall and Wilson, 2014). The metadata that we collected for each fanfiction is summarized in Table S1.

Quantifying novelty

The concept of novelty is multi-faceted and challenging to pinpoint. In the book Novelty: A History of the New, North describes novelty as “the state of being recent, unfamiliar, or different from the past” (North, 2013). In his pioneering research preceding the Wundt-Berlyne curve, Berlyne noted that the term is used widely, but “with scant attention to the need for specifying exactly what it denotes” (Berlyne and Parham, 1968), and designed experiments to characterize it empirically, finding that, e.g. a shape is considered less novel if it has been seen before; is more novel if it has many attributes different from previously seen shapes; and that novelty declines if the shape is displayed repetitively. Cognitive science emphasizes the role of memory in determining novelty; a stimulus is novel if it does not match anything in memory (Barto et al. 2013). In machine learning, novelty is recognized as an input that “differs in some respect from previous inputs” (Marsland, 2003). As it is not practical to capture all aspects of novelty in a single study, here we focus on the quality of novelty as being different from the past. Following previous studies (Askin and Mauskapf, 2017; De Vaan et al. 2015), we assess a work’s novelty in the context of other previously published works. A work is less novel if it is similar to many others published beforehand. Here we use the centroid, in feature space, of all past works in a fandom during a certain period as the guide for measuring novelty. A work is more novel the further it is from the center (see Supplementary Information for more details about our operationalization of novelty).

In line with existing research such as (Barron et al. 2018; Horvát et al. 2018; Klingenstein et al. 2014), we extract features from the works using the latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) (Blei et al. 2003), characterizing documents in terms of topics, or co-occuring word patterns. We construct document-term matrices with each fanfiction work as a row, and each term in the vocabulary as a column. For each work, we fit an LDA model on all fanfiction published in the same fandom within the past 6 months from when it was published (a model is only fitted if there are more than 20 works published during the current month, and more than 50 works in the previous 6 months). We therefore construct a feature space consisting of the topic distributions of all works from this time period. We then compute the centroid of the feature space as the average of all feature vectors. The novelty score si is defined as the Jensen–Shannon Distance (JSD; (Klingenstein et al. 2014)) between the fanfiction’s topic distribution and the center of the feature space:

where fi is the vector representation of fanfiction, and \({{\boldsymbol{f}}}_{{\boldsymbol{i}}}^{({\boldsymbol{c}})}\) is the centroid (see above). \({\boldsymbol{v}}=\frac{1}{2}({{\boldsymbol{f}}}_{{\boldsymbol{i}}}+{{\boldsymbol{f}}}_{{\boldsymbol{i}}}^{({\boldsymbol{c}})})\), and D is the Kullback–Leibler divergence between the two vectors.

The Python library gensim is used to fit LDA topic models on our data. The parameters are: number of topics = 100, α = 0.01, and iterations = 50. Our results do not significantly change even if we vary the number of topics to 20, 40, 60, 80, and 120 (results not shown). The number of topics indicates the granularity of topics extracted from our data using LDA. The α parameter controls the sparsity of topics distributions. Smaller values cause the model to associate fewer topics with the documents, which allows us to better differentiate documents. The number of iterations controls how many times the algorithm will run and update the model. Our value provided sufficient convergence on our data. The texts are preprocessed by removing the words that appear <5 times or appear in over 90% of documents; a common practice in fitting LDA models (Řehůřek, Radim, 2022). Additionally, we remove the punctuations, numbers, and convert all text to lowercase, but do not divide the documents into chunks. The data and code that we used are made availableFootnote 2.

Results

We first examine the soundness of our operationalization of novelty by qualitative checks and close-reading. Examining individual fanfiction with different novelty scores, we found that the fiction with the lowest novelty score (in the 95% percentile) tends to feature common character pairings and story settings, and more often contains explicit content. Meanwhile, fanfiction with the highest novelty score (in the top 5% percentile) often features unusual elements such as:

-

rare character pairings, e.g. Remus Lupin/Walden Macnair in the Harry Potter fandom.

-

rare world settings, e.g. an alternative universe where all characters are cave people (and have corresponding vocabularies).

-

uncommon writing style, e.g. in a text message or screenplay form.

-

unusual sexuality, e.g. bestiality.

We believe most readers will find such uncommon elements to be intuitively novel. In Supplementary Information, we list the titles and URLs for the 5 works with the highest and lowest novelty scores in each fandom; we encourage readers to explore these worksFootnote 3.

Correlation between novelty and success

Figure 1 shows the interaction between the novelty score and hits, Kudos, comments, and bookmarks (see the “Methods” section). Hits measure the number of times the link to the work was clicked on; Kudos is similar to a “like” in social media, while there is no option to dislike; and comments and bookmarks measure the total number of comments and bookmarks received by each work. We show the average and variance of these metrics, aggregated across fandoms, as novelty increases (see Fig. S3 for term-level measurement). Because of the wide dynamic range and fat-tailed distributions (see Supplementary Information), we compute the logarithm of the success metrics; since the fandoms differ in size and amount of fan activity, we present the z-scores of these values. Here the mean for the z-score is the mean response in each fandom, and expectation is all works in the fandom. As the topic novelty score increases, the average z-scores of responses in the form of hits, Kudos, comments, and bookmarks decrease across the board, displaying a negative correlation. The more novel a work becomes, in short, the less likely readers read, engage, or express enjoyment of it.

The engagement metrics (hits, Kudos, comments, and bookmarks) and its variance tend to decline although the variance of Kudos does not decline (or even slightly increase) for high-novelty works. The horizontal axes are the novelty scores divided into percentiles. The left column shows the corresponding average of the z-score of Kudos, hits, comments, and bookmarks, and the right column shows the variance. 95% confidence intervals obtained from bootstrap resampling are shown.

Because engagement (e.g., comments and Kudos) is conditional upon the reading of the piece, we also examine the ratio between Kudos and hits, which captures the likelihood of expressing enjoyment, conditioned upon the reading of the pieceFootnote 4. For instance, it is possible that high-novelty works receive more enthusiastic responses but only from a small niche audience. To test this, we compare the ratio between Kudos and hits for fanfiction in the low novelty range (bottom 25%) and high novelty (top 25%). A higher ratio indicates that a larger percentage of people who read the work have left Kudos on it. Figure 2 shows the kernel density estimation of the distribution of the Kudos-to-hits ratio for the low and high novelty works. We found that the high novelty works have a significantly higher Kudos-to-hits ratio. This pattern holds for most fandoms when they are analyzed separately (see Fig. S12), although not observed in our term-level novelty measurement. In other words, although high-novelty works tend to be read by fewer people, those who read are more likely to express their enjoyment. This observation motivates us to consider the Kudos-to-hits ratio as another key metric that captures the expression of enjoyment. In order to better isolate the relationship between novelty and success, we conduct a regression analysis in the next section.

High-novelty fanfiction are observed to receive more kudos with respect to the number of hits they receive, although having fewer hits overall. This pattern can also be observed for every fandom individually (see Supplementary Information).

Regression analysis

We consider the same five response variables (log of Kudos, hits, comments, bookmarks, and Kudos-to-hits ratio) in our regression models.

Independent variables

The topic novelty score is the predictor variable in all models. To account for possible non-linear relationships such as the inverted U-shape curve, we also use the square value of the score as an additional predictor variable. We mean-center the topic novelty score before computing the square value.

Control variables

We consider the following control variables. (1) fandom fixed effects: we also perform multiple regression on individual fandoms separately (see Supplementary Information). (2) number of chapters: multi-chapter works have additional chances for exposure, and higher metrics may stimulate an author to write more chapters. (3) number of words. (4) time of publication: AO3’s user base has been increasing and one may expect either newer works to receive higher metrics than older ones because they are visible to a larger audience, or that older works may perform better because they had more time to accumulate readers. We use the number of days since a work was completed (for finished works) or was last edited (for incomplete works). (5) total number of works by the author in question: authors may accumulate fame which may bias readership and success. (6) average Kudos of author’s works; The amount of Kudos that an author received in their previous work may be highly correlated with the amount of Kudos for their current work. (7) author history: the number of days since the author’s first publication. (8) character-pairing: the relationship between characters is one of the main reasons that many fans read fanfiction, and some relationship pairings have larger fan bases than others. To account for this effect, we control for a binary variable, “frequent relationship”, to indicate whether a work features a relationship that is among the top five most frequent relationships in its fandom. Finally, (9) the “archive warnings” indicate that the fanfictions contain sensitive elements such as graphic violence or major character death, and may influence the readers’ choice to read them; the age ratings restrict some fictions to adults only; the types of character relationships may also influence the readers’ choices. Categorical variables are created to capture their effects.

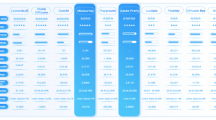

The correlations between the numerical variables are shown in Fig. 3. We noticed weak negative correlations between the novelty score and hits, Kudos, comments, and bookmarks; however, the novelty score is positively correlated with Kudos-to-hits ratio. The number of words is moderately correlated with success. Average number of Kudos of an author’s work is strongly correlated with Kudos. Moderate to strong positive correlations exist between the number of chapters and bookmarks/comments. However, no strong pairwise correlation is found between the predictor and the numerical control variables. We also examined the Variation Inflation Factor (VIF) and removed two variables that cause strong collinearity (the age of the work and days since the author’s first publication), although keeping it does not qualitatively influence the results. The variables that each model contains are summarized in Table 1.

Strong positive correlation is found between the response variables except for the Kudos-to-hits ratio. Topic novelty is weakly positively correlated with Kudos-to-hits ratio, but negatively correlated with the other response variables. Additionally, the number of chapters, number of words, and average Kudos of an author’s work are moderately positively correlated with success.

Because there are many zero values in the response variables (many works receive no comments at all, for example), we use a two-part model (Humphreys, 2013; Jones, 2000) (we do not use zero-inflated Poisson or negative binomial regression models because our outcomes are the average of log-counts data). A logistic regression is first performed on the predictor and control variables to predict the probability of each sample having a non-zero outcome. This probability is then used as an additional predictor variable in a pooled OLS regression on the samples with non-zero outcomeFootnote 5. We use the Python library statsmodels (Seabold and Perktold, 2010) to perform the analysis.

Selected OLS coefficient estimates of the models are shown in Fig. 4. We consider the control variables first. A work featuring frequent relationships is slightly more likely to receive more Kudos. Contrary to our initial assumptions, the number of chapters and the author’s fame do not have a significant influence on success. While the coefficients of the categorical control variables are not shown here, we found that work published in newer and more popular fandoms such as Star Wars and MarvelFootnote 6 tend to be more successful. Elements such as character death and violence are associated with poorer recognition. For full results with all coefficients (see Fig. S9).

N = 520, 730. a Does not include the square value of the novelty score, while b does. 95% confidence intervals are shown. The coefficients of the categorical variables are omitted (see Supplementary Information for the full coefficients). Among the control variables, the number of chapters and the author’s fame do not have an effect on the outcome, while featuring a frequent relationship has a slightly positive effect. In both a and b, novelty has negative effects for hits, Kudos, comments, and bookmarks; however, b shows that the squared value of novelty has a large positive effect on these outcomes. The effect on Kudos-to-hits ratio exhibits the opposite pattern.

We then examine models 1–4, which do not include the square value of the novelty score (Fig. 4a). Upon controlling our control variables, we find that novelty has a negative effect on Kudos, hits, comments, and bookmarks. For example, increasing novelty by 0.1 (cf. Fig. 4) is associated with a decrease in Kudos by ~3.49. However, a positive effect on Kudos-to-hits ratio supports our previous observation that higher novelty is linked to lower success but more enjoyment.

When we add the squared values of novelty scores in models 5–8 (Fig. 4b), the coefficients of the novelty score are similar to that in models 1–4, suggesting the robustness of our models. At the same time, we find that the effect sizes of the squared novelty score are all positive and large for Kudos, hits, comments, and bookmarks. Both fanfiction with low and high novelty are therefore associated with better reception, suggesting not the inverted U-shaped curves, but U-shaped curves. Meanwhile, the coefficient for Kudos-to-hits ratio suggests an inverted U-shaped curve. We observe similar results with our term-level novelty measurement (see Fig. S5).

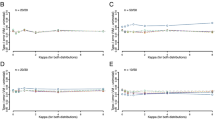

GAM

Our regression results suggest a nonlinear relationship between novelty and success. To examine this further, we turn to generalized additive models (GAM) (Hastie, 2017), which allows us to study non-linear relationships in complex data more directly (e.g. (Horvát et al. 2018)). We use the non-zero subset of the response variables now without log transformation and use the same predictor and control variables as in the linear regression models (see Table 1). The models are fit using the mgcv library in R, with the following parameters: k = 5 and sp = 0.1. The parameter k controls the smoothness of the model and specifies the maximum degrees of freedom used to approximate the smooth term. A higher k allows for a more complex model (i.e. more jagged in appearance) but risks overfitting. The sp parameter controls regularization applied to the smooth term. Through experimentation, we tuned the parameters and found these values allow a descriptive model without overfitting our data.

The partial dependence plots of the models are shown in Fig. 5. Results show an overall decreasing relationship between novelty and the response values, but also suggest a higher uncertainty with the large confidence intervals, with upticks for very high novelty. These plots present a U-shaped curve, confirming our observation from the previous section. At the same time, the results for Kudos-to-hits ratio suggest an inverted U-shaped curve, where moderate novelty is associated with the highest outcome. In other words, conditioned upon the reading, fanfiction is more likely to receive Kudos if it has a moderate amount of novelty, which concurs with the balance theory. Although we find similar patterns for Kudos, hits, comments, and bookmarks with our term-level novelty measurement (see Fig. S6), the inverted U-shaped curve for Kudos-to-hits ratio is only observed with topic-level novelty.

Together, our results capture distinct dynamics across the two stages of recognition. The first stage is about readers’ choice to click and read. Our results suggest that familiarity drives engagement—the more familiar a work sounds, the more likely people would read it. While this effect dominates, extreme novelty may also drive engagement as a U-shaped curve is suggested by the models. This selection dynamic largely drives other engagement metrics as well. The more people read it, the more Kudos, bookmarks, and comments it will likely receive. However, there may be another important process in play: novelty drives enjoyment, although too much novelty may reduce the enjoyment (inverted U-shape suggested by the regression models). The final outcome of audience appreciation is the result of these two processes that are working in the opposite direction—sameness entices, but novelty enchants.

Discussion

Traditional theories suggest that people like things with a balance of familiarity and surprise. Our findings from the fanfiction community add nuances to these theories by disentangling two metrics for success: attraction and enjoyment. Attraction is found to follow a U-shaped curve (with an overall decreasing trend) while enjoyment follows an inverted U-shaped curve (with an overall increasing trend). That is, people tend to choose to consume cultural products that they are familiar with; but when they consume highly novel material, they are more likely to express their enjoyment.

Our characterization of novelty captures word usage and topic variations; while we find similar patterns for attraction with our term-level and topic-level novelty measurement, the optimal differentiation phenomena is much stronger with topic-level novelty measurement. Although both methods mainly assess novelty based on content, unusual rhetorical and stylistic features are often accompanied by word usage, and can be captured by our method to a certain degree. This has been demonstrated by previous studies; for instance, the voice used in the text can be reflected in word usage (e.g., the over-representation of certain pronouns and verbs) (Argamon et al. 2003). Rhody demonstrated that topic modeling can be applied to figurative language such as poetry, and extract esthetic themes (Rhody, 2012). In a study on debates during the French Revolution (Barron et al. 2018), a similar method was used to model each document with a distribution over topics and to define the novelty of each speech. This study validated this operationalization with close reading, showing that topic modeling does not only capture semantic topics but also rhetorical moves by the speakers. In our work, we have found similar patterns; for example, the most significant topic of fanfiction written as a series of text messages includes topic words “sent”, “file”, and “replied”, implying the unique style of the writing.

Our methods, however, neglect the semantic information contained in word orderings. In literary theories, the arrangement of events plays an essential role in stories. Our methods capture the “material” of stories but are unable to evaluate the way it is arranged. Other features such as sentence length and punctuation usage are also neglected by our methods. This treatment of stylometric features may bias our evaluation of novelty.

Intuitively, one may believe that fans in fandom are drawn to material derived from the canon that they enjoyed because it reinforces the narrative and character elements they already appreciate. However, existing works such as Sourati Hassan Zadeh et al. have found the opposite (Sourati Hassan Zadeh et al. 2022), suggesting that fanfiction readers may not be attached to all elements of the canon. For example, in the Harry Potter fandom, among the 25% of works with the lowest novelty, we found that 15.8% include the “Alternative Universe" or equivalent tags; among the 25% of works with the highest novelty, only 6.9% do, indicating that Alternative Universe is in fact a common trope in this fandom. Canonical fanfiction offers a sense of continuity and comfort, which may explain its broad appeal compared to more novel works; however, familiarity in fanfiction may not be necessarily tied to the canon but can be through established tropes in the community (Busse, 2017).

The boundaries that fandoms impose on themselves provide a natural control for the variation in subjects, characters and settings, allowing us to better isolate the influence of novelty, and avoiding the confounding factors that may have contributed to the single inverted U-shape curve found by previous studies. However, our study has its limitations. First, our study design does not allow us to draw causal relationships between our variables. Our results are based on observational data analysis and thus correlational. Our study is also focused on a specific genre of cultural products that are produced and consumed as a subculture. Although online fandoms are well-isolated and better-controlled systems, both the authors and the consumers of the works are drawn from a particular sub-population skewed towards young females, and largely from English-speaking countries. Most importantly, we do not fully understand the characteristics of the fan subpopulation that is gathered around fanfiction culture. When we collect data, we also only sample from the current dominant platform, AO3, and from popular fandoms. Our data therefore contain works that are, on average, more popular than works from minor fandoms or venues. We leave it to future works to collect data from such platforms.

Fanfiction is usually the domain of amateur writers whose training, socialization, and incentives may differ from the “professional” producers of cultural products in other domains. In addition, although fandoms are often celebrated as democratic and without a top-down hierarchy, fanfiction writers can still accumulate cultural capital by interacting with other fans and promoting their own works on social media platforms, and become “celebrities” in their fandoms (Chin, 2018). While our study controls for authors’ fame within AO3, we are not able to account for such effects from external platforms.

We leverage established definitions of novelty from existing literature to operationalize novelty computationally; however, because of resource limitations, we do not systematically examine works with different novelty scores to check if they align with human readers’ expectations of novelty. We leave it to future work to gather human annotation of the dataset and gain insight from a manual rating of novelty.

Our results may also diverge from previous research because of the methods we used. In the early experiments by Berlyne (1970), they controlled the novelty of geometric shapes by having the subjects exposed to them, and then evaluated the success by asking the subjects to report their “interestingness”. Similarly, Zajonc’s experiments exposed subjects to groups of words (Zajonc, 1968). Such different data and setup can be one reason for the different outcomes. However, we also note that our results diverge from some recent research that measures novelty and success similar to our study (Askin and Mauskapf, 2017; Horvát et al. 2018), suggesting that our findings are not merely caused by the different experimental setups.

One potential explanation for this divergence is that we may be looking at a different cultural market from existing works. Paid cultural products have already passed some quality threshold to be published and enter the consumer market, where high novelty may be more likely to find enjoyment; while familiarity may be much more prevalent among works that did not clear this threshold. Framing the consumption of cultural products as a two-stage process (Zuckerman, 2016), our findings about familiarity may explain the first stage (conformity) and the optimal differentiation phenomena may be stronger in the second stage (differentiation).

Even with the aforementioned limitations, our study may have important contributions and implications. First, our analysis teases out two competing forces—attraction vs. enjoyment—and the contrasting roles played by familiarity and novelty, thereby providing a useful framework to investigate enjoyment, success, and evolution in culture. Second, as mentioned earlier, fanfiction is a well-controlled ecosystem that is free from many confounding factors that make studying mainstream cultural products tricky. Third, our analytic strategies may be broadly applicable to other types of text narrative data. Future work may identify causal inference study designs to establish the link between novelty and the success of cultural products or investigate other ways to quantitatively estimate novelty in cultural products.

Data availability

The code we use to generate all data and results is available at https://github.com/yzjing/ao3. The URLs to the fanfiction we downloaded and our derived data are available at https://zenodo.org/records/15330747.

Notes

With the changes in the AO3 website, we were not able to re-collect the data at a later time. We leave it to future works to focus on the fandoms popular in recent years.

Some of these works contain explicit material.

While the expressed enjoyment may not accurately reflect actual enjoyment (e.g. it is possible that a reader enjoyed a fiction, but did not leave a Kudos), it is our best proxy in the data to gauge the actual enjoyment.

Simply discarding or keeping all zero responses does not qualitatively change our model outcomes (results not shown).

These fandoms may have long histories, but recent installments such as Star Wars’ new trilogy and the Marvel movies are associated with the influx of new fans.

References

Horkheimer M, Adorno TW (2007) The culture industry: enlightenment as mass deception. In: Ollman B (ed) Dialectic of enlightenment Ch 4, vol 94. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA, USA

AO3News (2024) Celebrating AO3’s 15th anniversary https://archiveofourown.org/admin_posts/30463. Accessed 1 Dec 2024

Archive of Our Own (2024) Content policy https://archiveofourown.org/content#II.C. Accessed 3 Jan 2025

Argamon S, Koppel M, Fine J, Shimoni AR (2003) Gender, genre, and writing style in formal written texts. Text talk 23:321–346

Askin N, Mauskapf M (2017) What makes popular culture popular? product features and optimal differentiation in music. Am Sociol Rev 82:910–944

Barnes JL (2015) Fanfiction as imaginary play: what fan-written stories can tell us about the cognitive science of fiction. Poetics 48:69–82

Barron AT, Huang J, Spang RL, DeDeo S (2018) Individuals, institutions, and innovation in the debates of the French revolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:4607–4612

Barto A, Mirolli M, Baldassarre G (2013) Novelty or surprise? Front Psychol 4:907

Berlyne DE (1970) Novelty, complexity, and hedonic value. Atten Percept Psychophys 8:279–286

Berlyne DE, Parham L (1968) Determinants of subjective novelty. Percept Psychophys 3:415–423

Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI (2003) Latent Dirichlet allocation. J Mach Learn Res 3:993–1022

Bornstein RF (1989) Exposure and affect: overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968–1987. Psychol Bull 106:265

Busse K (2017) Framing fan fiction: literary and social practices in fan fiction communities. University of Iowa Press

Campbell J, Aragon C, Davis K, Evans S, Evans A, Randall D (2016) Thousands of positive reviews: distributed mentoring in online fan communities. In: Proceedings of the 19th ACM conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, CSCW ’16, 691–704 (ACM, New York, NY, USA

Cheng R, Frens J (2022) Feedback exchange and online affinity: a case study of online fanfiction writers. Proc ACM Hum–Comput Interact 6:Article 402. https://doi.org/10.1145/3555127

Chin B, Morimoto LH (2013) Towards a theory of transcultural fandom. Participations 10:92–108

Chin B (2018) It’s about who you know: social capital, hierarchies and fandom. In: Booth P (ed) A companion to media fandom and fan studies. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 243–255

De Vaan M, Stark D, Vedres B (2015) Game changer: the topology of creativity. Am J Sociol 120:1144–1194

De Vany A (2003) Hollywood economics: how extreme uncertainty shapes the film industry. Routledge

Eiji Ō, Steinberg M (2010) World and variation: the reproduction and consumption of narrative. Mechademia 5:99–116

FanFiction (2008) Fanfiction content guidelines https://www.fanfiction.net/guidelines/. Accessed 1 Dec 2024

Floegel D (2020) "Write the story you want to read”: world-queering through slash fanfiction creation. J Doc 76:785–805

Geraghty L, Chin B, Morimoto L, Jones B, Busse K, Coppa F, Santos KMK, Stein LE (2022) Roundtable: the past, present and future of fan fiction. Humanities 11(5):120

Halberstadt J, Rhodes G (2003) It’s not just average faces that are attractive: computer-manipulated averageness makes birds, fish, and automobiles attractive. Psychon Bull Rev 10:149–156

Hargreaves DJ (1984) The effects of repetition on liking for music. J Res Music Educ 32:35–47

Harman S, Jones B (2013) Fifty shades of grey: snark fandom and the figure of the anti-fan. Sexualities 16:951–968

Hastie TJ (2017) Generalized additive models. In: Hastie T. J (ed) Statistical models in S. Routledge, pp 249–307

Helmke Library Overview (2024) Fanfiction 101: Customizing Your Superheroes / History https://library.pfw.edu/c.php?g=16316&p=89234#:~:text=The%20growing%20popularity%20of%20fanzines,Star%20Trek%20franchise%20in%201966. Accessed 3 Jan 2025

Horvát E-A, Wachs J, Wang R, Hannák A (2018) The role of novelty in securing investors for equity crowdfunding campaigns. In: Chen Y, Kazai G (eds) Proceedings of the AAAI conference on human computation and crowdsourcing, vol 6(1). AAAI Press, pp 50–59

Humphreys BR (2013) Dealing with zeros in economic data. Department of Economics, University of Alberta, Alberta

Huron D (2013) A psychological approach to musical form: the habituation-fluency theory of repetition. Curr Musicol 7:7–35

IMDbPro (2021) 2021 worldwide box office https://www.boxofficemojo.com/year/world/2021/. Accessed 26 Sept 2023

IMDbPro (2022) 2022 worldwide box office https://www.boxofficemojo.com/year/world/2022/. Accessed 26 Sept 2023

Jacobsen M, Bizzoni Y, Moreira PF, Nielbo KL (2024) Patterns of quality: comparing reader reception across fanfiction and commercially published literature. In: Haverals W, Koolen M, Thompson L (eds) Proceedings of the Computational Humanities Research Conference 2024 (CEUR workshop proceedings), vol 3834. Computational Humanities Research, pp 718–739

Jaegher HD, Paolo ED (2007) Participatory sense-making: an enactive approach to social cognition. Phenomenol Cogn Sci 6:485–507

Jenkins H (2012) Textual poachers: television fans and participatory culture. Routledge

Jones B (2014) Fifty shades of exploitation: fan labor and fifty shades of grey. Transform Works Cult 15:115–123

Jones AM (2000) Health econometrics. In: Handbook of health economics, vol 1. Elsevier, pp. 265–344

Klingenstein S, Hitchcock T, DeDeo S (2014) The civilizing process in London’s Old Bailey. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:9419–9424

Kunst-Wilson WR, Zajonc RB (1980) Affective discrimination of stimuli that cannot be recognized. Science 207:557–558

Manovich L (2007) What comes after remix. Remix Theory 10:2013

Marsland S (2003) Novelty detection in learning systems. Neural Comput Surv 3:157–195

Mauch M, MacCallum RM, Levy M, Leroi AM (2015) The evolution of popular music: USA 1960–2010. R Soc Open Sci 2:150081

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2024) fan fiction. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fan%20fiction. Accessed 8 Nov 2024

Meyers-Levy J, Tybout AM (1989) Schema congruity as a basis for product evaluation. J Consum Res 16:39–54

Mohanty P, Ratneshwar S (2016) Visual metaphors in ads: the inverted-u effects of incongruity on processing pleasure and ad effectiveness. J Promot Manag 22:443–460

Mull HK (1957) The effect of repetition upon the enjoyment of modern music. J Psychol: Interdiscipl Appl 43(1):155–162

Nguyen D, Zigmond S, Glassco S, Tran B, Giabbanelli PJ (2024) Big data meets storytelling: using machine learning to predict popular fanfiction. Soc Netw Anal Min 14:58

North M (2013) Novelty: a history of the new. University of Chicago Press

Organization for Transformative Works (2024) Welcome! https://www.transformativeworks.org/. Accessed 15 Nov 2024

Popova YB (2019) Participatory sense-making in narrative experience. In: Beach R, Bloome D (eds) Languaging relations for transforming the literacy and language arts classroom, Ch 8. Routledge, pp 153–169

Proctor W, Kies B, Chin B, Larsen K, McCulloch R, Pande R, Stanfill M (2018) On toxic fan practices: a round-table. Participations 15:24

Pugh S (2005) The democratic genre: fan fiction in a literary context. Seren

Řehůřek R (2022) Core concepts–gensim. https://radimrehurek.com/gensim/auto_examples/core/run_core_concepts.html Accessed 13 Aug 2023

Rhody LM (2012) Topic modeling and figurative language, CUNY Graduate Center

Rouse L, Stanfill M (2023) Over* flow: fan demographics on archive of our own. Flow J

Salganik MJ, Watts DJ (2008) Leading the herd astray: an experimental study of self-fulfilling prophecies in an artificial cultural market. Soc Psychol Q 71:338–355

Salganik MJ, Dodds PS, Watts DJ (2006) Experimental study of inequality and unpredictability in an artificial cultural market. Science 311:854–856

Seabold S, Perktold J (2010) Statsmodels: econometric and statistical modeling with Python. In: Walt SJ Van Der, Millman J (eds) Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, scipy.org

Sourati Hassan Zadeh Z, Sabri N, Chamani H, Bahrak B (2022) Quantitative analysis of fanfictions’ popularity. Soc Netw Anal Min 12:42

Sreenivasan S (2013) Quantitative analysis of the evolution of novelty in cinema through crowdsourced keywords. Sci Rep 3:2758

Thelwall M, Wilson P (2014) Regression for citation data: an evaluation of different methods. J Informetr 8:963–971

Thomas B (2011) What is fanfiction and why are people saying such nice things about it? Storyworlds 3:1–24

Tosenberger C (2008) Homosexuality at the online Hogwarts: Harry Potter slash fanfiction. Child’s Lit 36:185–207

Uzzi B, Mukherjee S, Stringer M, Jones B (2013) Atypical combinations and scientific impact. Science 342:468–472

Vazquez-Calvo B, Zhang LT, Pascual M, Cassany D (2019) Fan translation of games, anime, and fanfiction. Lang Learn Technol 23(1):49–71

Wikipedia contributors (2018) Fandom—Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fandom&oldid=875627543. Accessed 15 Jan 2019

Zajonc RB (1968) Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. J Personal Soc Psychol 9:1

Zuckerman EW (2016) Optimal distinctiveness revisited. In: Ashforth BE, Ravasi D, Schultz M, Pratt MG (eds) The Oxford handbook of organizational identity, vol 183. Oxford University Press

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EJ and SD conceived the study; EJ collected the data; EJ, SD, and YYA contributed analytic tools; EJ, SD, DRW, and YYA performed the analysis; and EJ, SD, DRW, and YYA wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies that require informed consent from participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jing, E., DeDeo, S., Wright, D.R. et al. Sameness entices, but novelty enchants in fanfiction online. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1018 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05166-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05166-3