Abstract

With technological and economic developments, several Chinese migrant families have returned to China from the West to China. Families with multilingual and multicultural backgrounds might experience more challenges in child-rearing than the locals. Drawing on a life-course perspective, we used a qualitative research method to investigate 18 Chinese returned migrant families with young children to enhance our understanding of the complex cultural and contextual issues in modern Chinese parenting. Findings reveal that individual experiences and family development are contextualised culturally and historically. The results highlight two contemporary Chinese socio-cultural factors, Tiger Mum and Lying Flat, which may influence Chinese parenting among the younger generation. Parenting is a complex, multidimensional, dynamic phenomenon. This study proposes that family migration experiences, family relationships, parents’ careers, and parenting styles should be considered to understand parental challenges better before resettlement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Culture is an integral part of our society and family. Parenting is a social activity that cannot be separated from individual family contexts and comprises different beliefs and value systems (Le et al. 2008). Parents’ behaviours, parenting styles, and family relationships can vary in different life stages and socio-cultural contexts. This results in an urgent need to explore their cultural adaption, culturally specific beliefs, and parental practices, which will help these families improve their child-rearing skills and knowledge in the new enrionment (Bornstein, 2012).

After the open-door policy was implemented, Chinese students were encouraged to receive advanced technology and elite education in the West. Between 1978 and 2019, 6,560,600 Chinese nationals studied abroad. By the end of 2019, 4,904,400 participants had completed the studies. Of this number, 4,231,700 students (86.28%) chose to return to China after completing their studies. In 2019, approximately 580,300 Chinese international students returned to their homeland, a 12% increase from 2018 (MOE, 2019). Over the last 30 years, many international students have obtained work permits and worked in the West. The number of Chinese returned migrants has increased over the previous decade. With technological development, the government has focused on academics. Different levels of the Chinese government have implemented various strategies to attract overseas talent to return to work, which could lead to a surge in the number of returnees (L. Ma et al. 2023). Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Beijing, and Chengdu have been identified as the most popular cities in China for attracting both Chinese returnees and workers from overseas (Centre for China and Globalization, 2019).

Parents from different cultures often adopt different parenting approaches. Parent-child relationships, parenting style, parental expectations, childrearing patterns, and trends differ when families are resettled in other social-cultural contexts (e.g. Bornstein, 2012; Selin, 2022). In the 21st century, Chinese return-migrant families are small cohorts that experience a cultural shock when they return to China. In addition, this cohort transitions from one country to another with their families, and their life events might have been unique. In their life trajectories, their perspectives on the turning point might differ from those without prior experience. However, to the best of our knowledge, few researchers have focused on this field. As the number of Chinese migrants from overseas increases, examining their parenting experiences is necessary. This enables researchers and policymakers to obtain first-hand parental perspectives on the cultural norms that shape parenting. Also, their child-rearing experiences are important for decision-makers to inform social policies and provide appropriate support for these families.

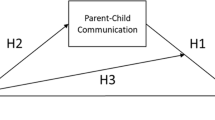

This study adopts a qualitative research method to explore Chinese return-migrant parents’ perspectives on the cultural norms that shape their parenting and consequent parental experiences after settling in an international community. A multidimensional theoretical framework that shows perspectives on parenting and culture, as well as the literature on Chinese parents and migration, underpins this study. The study highlights that the unique ‘Tiger Mum’ and ‘Lying Flat’ cultures influence young parents’ child-rearing. Complex socio-cultural factors must be considered when relocating to different social contexts.

Theoretical framework

This study is underpinned by life course theory (LCT), which views returned Chinese migrants as an inherently dynamic phenomenon. They are considered an integral part of the life course where individuals live in social contexts. The LCT provides a coherent tool to examine Chinese returned migrants and their family members’ life trajectories and events during transformation (Elder, 1985, 1994; Kulu and Milewsk, 2007). Life-course transitions are regarded as important factors for Chinese returnees who view their life experiences and parenting differently (Bernard et al. 2014). Previsous studies mainly had two trends by using LCT in the migration research, which have not connected strands along the question regarding the “determinants and the consequences of migration” (Erlinghagen, 2021, p 1339). In this research, we used the principles in a more comprehensive way. The focus is to understand returnees’ transitions (or life events) and trajectories (or changes in careers) in the key domains of participannts’ previous migration experience, the reverse return to a new invrionment, professions, and childhood experience. Trajectories or careers can be in parallel and often depend on one another. Van Wissen and Dykstra (1999) believed that individuals’ life events could be intercorrelated and interdependent on their life course trajectories; an event in one trajectory can bring about status changes in other trajectories.

Literature review

This part explores the key concepts of Chinese returned migrants’ parenting that are interdependent on life course trajectory and life events in their migration experience.

Chinese returned migrant families

The return of migrant families to China is closely correlated with those of migrant workers. Migration is closely related to economic and cultural development in both developed and developing countries, such as Canada (Vanderkamp, 1972), the USA (Lee, 1974; Warren, 2024), Japan (Achenbach, 2017; Suzuki, 1995) and Mexico (Orrenius, 1999). China is no exception. Hays reported that “China’s overseas returnee population has been growing in the last five years. Statistics from 2019 show that in the 40 years since China’s economy started opening up, more than 3.13 million of the Chinese students who graduated abroad have returned home” (2021, p 1). China’s culture and stable political environment are essential factors in drawing Chinese immigrants back to China (Miao and Wang, 2017). However, life stress, loneliness, and cultural shock were not the reasons for their return to China. This finding reflects the fact that patience and perseverance are important cultural traits in China. For most Chinese returnees, it is a virtue to try to adapt to new learning and living environments.

Skilled migrant workers and elite Chinese returnees account for a large proportion of the total number of migrants. When they return to China, children and family members come along with them, resulting in cultural shock (Lu, 2018), confusion and stress (Ai, 2019), and social reintegration (Lu, 2020). These returned children and parents face more challenges, such as language adaptation, schooling, and cross-cultural adjustment. Previous studies evidenced that migrant children may be less successful academically if their social resilience is low (e.g. Li et al. 2020; Mu, 2023). Research (e.g. Palaiologou, 2007) shows that migrant children could have school adjustment problems and identified as low achievers, troublemakers, aggressive, undisciplined, disrespectful, and lacking identity, at least in the early stages of their return. Difficulties and challenges may result in negative life experiences from childhood to adulthood.

Returned parents’ career

Inspired by China’s Open Door Policy, Chinese students and families moved to developed countries, such as the USA, the UK, and Germany, to study and work, which was a way to improve their quality of life (Hai, 2010; Miao and Wang, 2017). In recent years, however, the number of Chinese returnees from overseas has increased owing to the rapid development of the Chinese economy and a safer and more comfortable socio-cultural environment (Miao and Wang, 2017). In 2021, approximately 1.05 million Chinese graduates returned to the mainland for work, an almost twofold rise from 2020, when 580,300 returned to seek employment, according to the Ministry of Education. Moreover, the Centre for China and Globalisation (CCG) surveyed Chinese returnees; 42 percent chose to return to China for work because they had a positive attitude toward the nation’s future economic development. Approximately 60 per cent said they had returned to reunite with their families. Among the factors affecting overseas Chinese returnees’ decisions to return to China, career choices and family bonds were ranked as the top factors. Among them, more than half chose to work in IT, universities, and inter-element manufacturing, with an average salary of 350,000 RMB/year (Ran, 2023). Most returnees feel that their homeland offers promising job prospects and a sense of belonging.

Individual life trajectories change as they move from one country to another. When Chinese migrant parents change their careers, their families’ economic and social statuses change accordingly. This influences family relationships and parenting in the new environment (e.g. Salaff and Greve, 2013; Yidan Zhu, 2020). For example, Zhu (2020) emphasised that good motherhood learning can be acquired and learned over time, identity, and transnational space. Chinese migrant mothers can reconstruct their identities and enhance their lifelong learning skills. Similar results were found by Salaff and Greve (2013); they showed that children’s education and family relationships were decisive factors in returned migrant families. Therefore, Chinese returnees should be careful when adapting to a new working environment.

Family relationships

Chinese people have focused on family and intergenerational ties. Confucianism emphasises (xue 学) and (xiao filial piety), which is rooted in the traditional Chinese culture (Tan, 2017). Chinese people value their strong kidship, and ties with generations. Also, confician ideal of learning is to encourage individuals to exter their effort to question themselves, reflect, and continuously practice with the purpose of self-transformation. This cultural foundation has been rooted in many immigrant families and their child rearing as well (Huang and Gove, 2015). Santos (2021) describes piety has been emphasised as an important element in perceiving Chinese moral values. Although Chinese family structures have changed in the last several decades, the basis of society has been traditionally recognised as a “multigenerational family” (Jankowiak and Moore, 2017, p 17). Miao and Wang (2017) found that one key factor for returning migrant families in China was that they wanted to stay close to their families, enjoy a more comfortable cultural environment, and feel a strong sense of belonging. Chinese one-child families may be more concerned about their elderly parents if they live in China (Lu, 2020). Previous studies have shown similar reasons for Polish migration to the United Kingdom (Kealy and Devaney, 2023). Polish ladies had to travel between the UK and their home counties to look after their elderly parents (Krzyżowski and Mucha, 2014). Maintaining good family relationships is a pivotal obligation for migrants despite their different cultural backgrounds.

Chinese parenting styles

Over the last several decades, Chinese parenting styles have been the subject of popular discussion among immigrant families (Xu et al. 2005). LeVine’s early parenting model (LeVine, 1980, 1988) found that parents’ responsibilities are to provide children’s basic needs, as well as love and care. The model suggests that differences in parenting behaviours could be explained by using different methods to realise these hierarchical goals when supporting families to minimise children’s risks and maximise their welfare. These strategies are passed on from one generation to another and are seen as common-sense child-rearing formulas in a particular culture. From an ecological perspective, parenting styles are a core element in a wide social context. Parents’ behaviour and parent-child interaction are influenced by their social and cultural values and other factors associated with family settings (Xu et al. 2005). Chinese migrant families have experienced more moves and changes in family settings, which might result in different parenting styles for returnees. Researchers believe that Chinese parents are more likely to adopt an authoritative parenting style when they have high living standards. This is particularly common in families which meet basic needs and receive education in the Western context (Xu et al. 2005). Similarly, the parent-child relationship is influenced by how parents and children behave and interact with each other. When parents feel depressed, they face challenges in fulfilling child-rearing goals, resulting in family dysfunction (Ma, 2020).

The gender roles and the responsibilities of males and females are closely related to Chinese trational culture and social expectiations. Normally, Chinese females are expected to be the primary caregivers of children in the family, and males are to lead the family and educate their children properly (Chen et al. 2017). In this review, Chinese people usually believe that “Zi Bujiao Fu zhiguo”, which emphzses that father should be stricter and take more respobility to look after the children (Dou et al. 2020). However, with the development of Chinese society, Chinese women have started to work and gradually played an important role in their professions and home. The new shared parenting style provides female an opportunity to have a stronger bond with their children, and as a consequence, they might spend more time to look after their children and families Researchers observed new charateriscs of the parenting style among these Chinese mothers such as ‘helicopter parenting’ and ‘tiger mother’ (Katz, 2018). Tigher mum is also found in Chinese migrants which described in Amy Chua’s book (2011), in which she presents harsh parental control. Chua (2011) provided many examples of her involvement in her children’s education and the strict rules she implemented in her daughters’ daily lives. Chua states several people wonder how Chinese parents raise such stereotypically successful kids. They wonder how Chinese parents produce so many math whizzes and music prodigies, what it is like inside the family, and whether they can do so, too. Well, I can tell them because I have done it’ (Chua, 2011, p 1). After the publication of this book, Chua’s immigrant parenting style stirred up wide discussions on whether Chinese mothers were supervisors (Leese, 2011 Febuary 21), and Callick in The Australian Opinion (2011 Febuary 22) questioned whether educational standards could be raised in the ideas of the Tiger Mum. Scholars have long debated parenting style and its consequences. Western scholars have primarily focused on exploring whether children would be more successful using this unique Chinese parenting style (e.g. Field, 2015; Lichtman, 2011; Yeh, Agarwal-Rangnath et al. 2022). However, Chinese scholars have criticised Tiger Mum as not mainstream parenting in mainland China, and it is more likely to be stereotyped by most migrant families (Zhu, 2011). Although the debate on this social issue has never ended, both Western and Chinese scholars believe that the reason for the ‘Tiger Mum’ phenomenon is that Chinese families generally have high expectations of their children’s academic development and future careers (Lu, 2018, 2020). Children and their parents experience significant stress, pressure, and a high level of competition.

However, parenting styles were unstable. In recent years, Chinese youth, particularly those born between 1995 and 2000, have adopted a ‘Lying Flat’ (tangping) pattern. Lying-flatism represents Chinese youth against official norms and social constraints, which further leads them to behave negatively in the Chinese context of ‘involution’ (neijuan). In comparison with revolution, the social phenomenon of ‘involution’ refers to a ‘regressive tendency of China’s entire system and the intensified malicious competition occurring at every level of society’ (Su, 2023: 6). Su (2023) argued that ‘involution’ indicates that society does not progress to a more efficient and advanced stage, so that people may have more malicious competition and social conflicts. As a negative consequence, several ‘middle-income’ families and their children experience frustration, pressure, and youth pessimism (Yao, 2020). The unique culture indicates that the immense pressure from students’ coursework, school competition, and employment constantly increases youth anxiety; anxiety further extends their uncertainty about careers, income, and future life. Their fear of the future may lead them to have a negative attitude to eventually ‘Lying Flat’ (Su, 2023). In this view, the ‘Lying Flat’ culture may push Chinese parents, particularly Tiger Mums, to have more concerns, such as school admission, academic performance, and graduation.

In summary, parents’ migration experience, childhood experience, family relationships, and parenting styles interplay in LCT, influencing parenting in the local social context. With the development of society, children’s behaviours may exhibit different patterns when they adapt to a new environment. However, to the best of our knowledge, little is known about Chinese returned migrants’s parenting experiences and challenges when they return to China, particularly how culture shapes their parenting styles. This study addresses this gap.

Research method

Sample

Sample recruitment was conducted between February 2023 and August 2023. After obtaining ethical approval, the researcher sent the research project information package to international communities in Shanghai (East China), Guangzhou (South China), and Shenzhen (South China) to inform local Chinese returnees. Supported by local social workers and community officers, 18 Chinese migrant families volunteered to participate. Most parents had completed their doctoral studies, and the majority worked in academia. Families were identified as young couples under 35 years old and were the only children in the family. Their children were between five and seven years old and were recognised as both mentally and physically healthy (Table 1). Following ethical practices, appropriate steps were adopted to safeguard participants’ anonymity, obtain informed consent, and maintain the confidentiality of the interviews. Semi-structured interviews were conducted according to individual time schedules. Finally, ten face-to-face and eight online interviews of 45 min each were recorded, transcribed, and analysed using NVivo 13.

Data analysis

The principal researcher undertook a thematic analysis (Herzog et al. 2019) and identified and analysed themes of the meaning of the qualitative data for exploratory research. The coding process included a close, in-depth reading of the context, searching for meaningful concepts, and focusing on the relationships between the different layers of code. During comparison, higher levels of codes and categories were formed. Informed by both the data content and theoretical framework of this study, three themes were identified and presented in the following sections. Participants were not reported with respect to confidentiality, and a few posts were slightly edited to ensure intelligibility.

Findings

The study found that most participants felt that their migration and professional experiences in the country were closely related to their decisions to return to China. They reflected on the nature of the family relationships and parenting skills they experienced in childhood, which influenced how they perceived their skills towards their children and family in the reversed return to China. Parents described the importance of putting themselves in their children’s shoes, particularly regarding cultural conflicts between parents and children. This was coupled with contextual factors’ impact on and influence of cultural norms, such as ‘Tiger Mum’ and ‘Lying Flat,’ which were emphasised by the parents.

Theme 1: Transition: migration experience

In this theme, participants reflected on how their own early migration experiences shaped and reshaped their parenting experiences when they returned to China with their children. This transition process is a life cycle comprising childhood, adulthood, and parenthood, which is highly related to the life course perspective. The factors decisive for returning to China are categorised as follows: (1) Chinese returned migrant parents’ early learning experiences and (2) how they perceived their children’s traditional cultural assimilation.

Chinese returned migrant parents’ early learning experience

Most parents believed that their lengths of stay overseas helped them use various perspectives to see how the world was constructed and culturally adapted when they decided to return to China. The participants sincerely thanked their parents for supporting them in their long-term studies and working overseas, which assisted them in their parenting. This is seen in the choices of schools dealing with family conflicts and parent-child relationships. Most parents believed that they would hold a more positive attitude towards disputes with their children and spouses, which helps ensure harmony in the family. However, some parents reflected that the longer they stayed overseas, the more difficult it was for their children to adapt to the new environment. One parent stated that her son felt challenged by changing to a Chinese school.

My husband and I stayed in Australia for a long time. Both of us finished Master’s Degrees there. Right after graduation, I was offered as a part-time preschool teacher in a nearby childcare. My son was sent to the same childcare centre when I worked. He enjoyed playing with teachers and made lots of friends in the centre. But after coming back to China, he seemed very challenging to adapt to the new environment. Even though he was sent to an international preschool, he still felt lonely and he always asked me when he could go back to Australia. (Family #1)

This mother (Family #1) further listed several parenting strategies she used to help her son quickly integrate into the new environment, such as listening patiently, cuddling and hugging, showing rewards, and trips together. The couple still maintains family traditions, as they used to in Australia. “All these could help the boy feel more welcomed and comfortable when he comes back home”. The couple added.

Children’s traditional cultural assimilation

In the interviews, a child’s favour of Chinese culture was another important factor for Chinese migrant parents to return. One father (Family#14) commented, “I helped his daughter to emerge in a Chinese community after she was born. The first reason for their consideration of moving back was his daughter’s strong interest in learning Chinese music”. Compared with other families, the couple had stable jobs in the West, but their only daughter favoured traditional Chinese music. They mentioned that their daughter had always watched Chinese singers on TV and learned from them. Once they heard about a traditional Chinese music festival in Shanghai, they took her daughter back to China to participate in the activities, and she enjoyed it. Since then, their daughter missed her Chinese peers. Finally, the family returned to China for the sake of her daughter’s dreams.

Most parents believed that if they migrated to the West when they were young students, it would be more difficult for them to help their children adapt to the Chinese social context. One couple stated that they returned to China because his parents wanted to set up the family business in China. In the first year, they experienced a reverse cultural shock, as their son was a naughty child in preschool. The mother (Family #18) commented that her son liked playing with other peers. During the play, it was unavoidable that peers would pounce on each other. For her, it was normal for boys to play with toys, but the Chinese teachers always called on her to visit the childcare centre. She was confused and did not know how to explain or communicate with teachers.

Theme 2: Professional experience

Chinese returnees’ professional experiences and career choices are key factors influencing their quality of life. Two sub-themes were grouped: (1) returning for a better job and (2) overseas profession helps to reshape parenting.

Returning for a better job

Most participants in this study were well educated; more stable, secure, and friendly employment opportunities are considered key motivators for returning to China. This was attributed to more secure positions and a better working climate. Parents generally believe that they return for employment reasons, which brings them higher social status and enables their children to have a ‘better life’. These findings suggest that the participants were reared in environments that reinforced the culture of a decent job while also being concerned with a functioning family life.

Many academics had the following experiences reflected by a male participant in their previous workplace issues, which influenced family relationships. The following example was provided by a male academic:

I believed that I could be promoted this summer [A big sigh here]. I have been working very hard and finished tasks as required. Before submitting the application for my promotion, I had a long discussion with my head and he also believes that I am qualified. However, I was turned down by the university academic committee as they wanted to promote a female professor in the faculty. My head and colleagues felt pity but they could not do anything about it. I felt stressed, concerned and uneased which influenced my family harmony. (Family #17).

This professor continued to reflect that his insecure job brought uncertainties to his child and wife. His spouse added, “His negative experience pushed us to make a quick decision to seek opportunities in China. Stress and work pressure will negatively influence child-parent relationships and family interactions’ (Family #17). After returning to China, he obtained a more secure position, which relieved his burden.

Overseas profession helps reshape parenting

In China, well-educated parents usually have high expectations for their children’s academic records. However, the participants in the study normally agreed that physical and mental health were far more important than academic achievement. The stereotype of ‘Tiger Mum’ could not be found among Chinese mothers in contemporary China. They were more inclined to be patient, warm, and supportive at home. Compared with local parents, returned parents mentioned that their professional experience could help them understand their children’s challenges. Meanwhile, it improved their rearing skills in the adaptive environment. Their similar life experiences allow them to talk about their children’s challenges, which can help them go smoothly.

Theme 3: Returnees’ experience in their childhood

For most Chinese parents who return during their parenthood, early life experiences are an important part of their life journey. It was categorised into four subthemes to indicate how Chinese returnees’ early childhood experiences influenced their adjustment to the new enrionment while meeting difficulties. These are (1) positive childhood experience, (2) strict parents, (3) family members’ impact, and (4) the generation gap.

Positive childhood experience

Most participants commented that their childhood experiences were important for them to contribute as caregivers. The participants mentioned that their positive childhood experiences, being loved, cared for, and feeling safe, would last as long-term memories in a reversed migrant. Even with conflicts, parents and children find it easier to communicate and develop a mutual understanding. However, if the migrant parents did not have an excellent childhood, their families would experience more challenges after they returned to the Chinese context. An example of those who had positive experiences in their early years is as follows:

I remember that I loved skating when I was little. But my grandparents expected me to be a quiet girl so they persuaded my parents to take me to learn musical instruments. Rather than urging me to learn any music instruments, they patiently asked my opinions. Thank goddess, they did not push me to do it…These positive experience seemed very common for all. Bur for a returnee, when I felt dpressed to adjust to the new enrionment, I would be strongly motivated to calmly seek for solutions (Family #5).

…I was supported by my parents when I was little. My parents always encouraged me to challenge myself and solve the problems actively. This experience extremely helped me when I was an international student oversea. Also, the experience assisted me in rearing my son. He was just a school student who turned to be six. A new enrionment seemed very challenging for him. The independence that I formed pushed myself to be quickly to get invovloed in the fight. In the first year of our return, my husband had to work for extra hours so I have to spend more time in lokking after my son… all the difficulties such has called out by teachers, picking-up my son, and visiting doctors were managed by myself. (Family #7).

To help my son quickly adapt to the Chinese context, I tried my best to spend my spare time with him after work.

…When I came back to China, I actively joined an online parental class to learn how to nurture and care for children, how to play with them, and how to learn with them. Most of the participants in the class were those as me who had a smilar background so I felt warm there. My son and I enjoyed it tremendously. My son recently completed preschool education and will soon be entering primary school. At home, I show my care and love to him, and I believe that I cannot use traditional methods to teach young children as they are more ‘digital’, ‘global’, and ‘inclusive’ than me. (Family #9).

Strict parents

In comparison to a warm family, a male participant described his mother as likely to be a “Tiger Mum’, who had a strong authority. These negative experience also brought more conflicts and barriers while the family returned to China.

…My mother always had a high expectation on me while I was studying at school. I was not allowed to play computer games, read novels, and make friends at school. It is restricted and stuffy to stay at home. I did not find any interest or motivation to learn. Gradually, I refused to talk to her…(Family #15).

To satisfy his parents, he had to behave obediently, which resulted in socially withdrawn behaviours. This personality trait created tension between him and his child when they returned to China. For example, he understood that it might be more difficult for his child to be involved in a new environment, but he could not help himself blaming his son for not finishing his homework.

Family members’ impact

Besides parents, most participants reflected on grandparents, neighbours, and peers as important persons in their childhood. Their personalities and values influence how they communicate with their children. A supportive, open, and inclusive family environment will help children with multicultural backgrounds adapt quickly to a new environment.

I am glad to see that our way of being a parent is good for her … She is brave to talk about everything with family members. She is not scared even if she has made mistakes. (Family #14).

Generation gap

Moreover, many migrant parents viewed hard work as a strong ethic in Chinese communities. However, when they returned to China, they found that young children favoured the youth culture of ‘Lying Flat’, which they had never heard in the West. One participant emphasised the following:

This sub-culture makes children to be pessimistic towards their future and involves social and economic factors in the social issues. However, parents need to learn how to identify positive qualities of children rather than only paying attention to their academic performance. Children need to know effort is still important in their life. (Family #3).

Chinese returned parents’ parenting

Most participants reflected that differences in cultural values and social norms might change their parenting ways and increase their child-rearing skills. These two subthemes are categorised to show the influence of different cultures: 1) the influence of culture in the migration host country, and 2) pop culture in contemporary China.

Influence of the culture in the migration host country

In most cases, investing time in their children was emphasised. Although most parents had to work more hours than they did in the West, they identified being together and happy as important elements for a close family bond. In their spare time, they would like to spend time with their children, which means getting to know them better. Most parents take responsibility for teaching their children and spending time with them. Feelings of love and affection were the most positive aspects of parenting.

The beautiful thing is just watching them grow and staying with my daughter. As long, I love her, as long as she is healthy with us (Family #5).

Some parents revealed how parenting has changed over time, with a move towards high competition, restriction and exam orientation.

Most participants illustrated their attempts to depart from their parents’ parenting methods; however, this seems difficult in the local context. This finding was also observed when exploring the transmission of values.

I often talked with other parents in the community and they pushed their children very hard to learn Olympiad Mathematics. …If my child did not go with them, he will leave far behind them. …Distress and worries made me difficult to sleep…(Family #4).

Many families echoed these concerns during the interviews. They did not want to drive their children to be wildly busy. However, children had to follow instructions to some extent. Participants highlighted that local parents prefer to be authoritative and hold a hierarchical family position. However, they did not expect their children to be equal. This parental pattern was observed when they supported their children in finishing their homework.

…You should listen to my suggestions so that you should have finished it an hour ago. Now, it is late for dinner. (Family #10).

Influence of pop culture in contemporary China

‘Lying Flat’ is a buzzword that the participants have popularly discussed. Most parents described its significance in the local cultural context. Both migrant parents and young children felt challenged by this contextual factor. The participants spoke about the impact of ‘neijuan’ on their wellbeing, using expressions like stressed, always tired and out of energy.

We have to work extra hours without any payment. It is tired. I have to say that it is not a good working environment. But I was persuaded by my local friends to consider the wealth annual income. Compared with others, I am lucky. (Family #9).

This value is reflected by participants in the industry and higher education. One mother believes that her stress is for her career and her son’s poor academic performance at school.

Mum, I think that it was too difficult and I could not pass. Crying and yelling during the arguments made me a headache and out of energy. (Family #16).

Discussion

The results showed that migrant parents returned to China mainly because of stable employment and family ties. Even facing challenges, they tried to foster a strong and positive parent-child relationship by being supportive and warm while simultaneously being a strict and harsh parent to transmit the traditional culture. Parental challenges arose in an attempt to balance family time to maintain a close bond with employment obligations. Chinese returned migrants experience different lives during the transition. The returned migrant families are well-educated couples, and with recognition of their previous work experience and education, so many parents do not find themselves struggling financially. However, they continue to try to ensure security. This was despite economic opportunities in China and parental perceptions that employment was easier in China than in the West. This result echoes a previous study (Miao and Wang, 2017), which argued that Chinese reverse migration is mainly due to China’s rapid development and that returnees could find themselves in a more secure society.

This study indicates that parents’ previous migration experiences are essential for valuing their culture and identity. Individuals’ valuable experiences explain that their views on parenting could change at different stages of their life trajectory (Elder, 1994). A positive experience will help children construct a Chinese cultural identity. Children’s cultural identities begin in their families and communities (Rogoff, 2014). A positive cultural identity is believed to be beneficial for personal, social, and educational development (Tualaulelei and Taylor-Leech, 2021). Long-term migration indicates that parents and children face more challenges when they return to China. This result is in agreement with previous studies (Ai, 2019; Lu, 2020) that described how Chinese scholars suffered after returning to China.

Childhood experiences are important for individuals who become parents. This is described in the LCT (Elder, 1994), which highlights that early learning experiences can influence adulthood and prenatalhood. Positive childhood experiences reduce the likelihood of risky behaviours, which are more important in shift settings. Parents who grew up in warm and supportive families followed a rearing approach involving parental affection, communication, and time commitment. However, the struggle between the traditional rearing approach (Tiger Mum) is notable in more negative childhood experiences; they spoke about the negative impacts on their mental health. This result indicates that parents’ psychological and genetic factors are key to child development during the transmission process (Belsky, 1984). Most parents highlighted that previous childhood experience might not support their children in knowledge construction as new concepts such as ‘Lying Flat’ are rising. This study also suggests that Chinese migrant parents must understand their children’s socio-cultural transmission.

Moreover, we found that most young parents had received a traditional Chinese moral education at school. They were taught to be ‘hard-working, humble, and obedient’ (Lu, 2018, 2020; Tan, 2017). With the dynamic development of society, they cannot understand the social problems underlying youth anxiety. This result is similar to those of previous studies (Lu, 2018; Su, 2023), which argued that young students should face challenges rather than being stormed and opting to be pessimistic in academic learning. Further, we determined that young parents were influenced by social norms, such as ‘Modesty helps one progress’, ‘the importance of self-reliance’, and ‘living in harmony with others’. These results are consistent with previous studies that reflected that the value of collectivism is very important at schools, and this is also emphasised by conficianism (Tan, 2017). However, their perceptions of parenting are much more open, easy-going, and supportive than their parents. This could be due to the increased number of parental training sessions and scientific workshops conducted to help young couples improve their parental skills and knowledge in communities (Lu et al. 2023).

Evidence of the interplay between migration experience, childhood experience, employment, and parenting styles, all of which impact child rearing, suggests that parenting occurred within the parent-child relationship and a broader context (Jack, 2000). Therefore, the results support the LCT (Elder, 1994), which explains that life events and trajectories can be paralleled. Additionally, the study supports Belsky’s (Belsky, 1984) argument that childhood has an impact on parenting. This could be viewed from parents’ preferences for their upbringing when describing their approach to child-rearing. Furthermore, the results support the study undertaken by Mistry et al. (2002), who argued that culture and context cannot be treated as synonymous and have a culture situated in the macrosystem. The study found that cultural norms are an essential factor that impacts the parent-child relationship, as well as parenting in different social contexts.

Conclusion

Cultural norms shape how Chinese migrant parents from overseas perceive their roles as parents, initially based on their childhood experiences. In reversed migration, practices are mediated by beliefs and values within the family as well as those of their immigrant countries. Cultural norms are unstable, suggesting that parents and children must discuss and adapt to new environments. The different situations among families result from different circumstances, which determine their adaptation to the returnees’ current social environment and their social settings before migration. This study supports the notion that the parenting practices of Chinese return-migrant parents are multidimensional and dynamic constructs shaped within the social context. It also highlighted that there are challenges to adaptation, as parents are not only bound by their previous migration experience but also by the subculture and new staff in their home country. Furthermore, migrant returnees’ parental practices can be considered complex and adaptive processes influenced by a series of contextual factors. Differences in parenting are not only found between Chinese returned migrant families and local groups but also within local families, highlighting that there is no easy and mature path.

This study had two limitations which require future research. First, most participants were migrants who worked and studied in Europe, North America, and Australia, with few in Asia. Their migration experiences are homogeneous. Future research should explore this cultural norm in the global context. Second, the participants were well-educated, and most of them completed doctoral and master degrees, which might have similar educational and professional experience. In future, researchers could investigate Chinese returnees with diverse academic and employment backgrounds, which may yield interesting results.

Data availability

The data will be made available by the author on a reasonable request.

References

Achenbach R (2017) Return migration decisions. Springer VS Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden Germany

Ai B (2019) Pains and gains of working in Chinese universities: an academic returnee’s journey. High Educ Res Dev 38(4):661–673

Belsky J (1984) The determinants of parenting: a process model. Child Dev 55(1):83–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x

Bernard A, Bell M, Charles-Edwards E (2014) Life-course transitions and the age profile of internal migration. Popul Dev Rev 40(2):213–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2014.00671.x

Bornstein MH (2012) Cultural approaches to parenting. Parent 12(2-3):212–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2012.683359

Callick R (2011) Tiger mum the key to Chinese results. The Australian Opinion. Retrieved from http://www.theaustralian.com.au/opinion/columnists/tiger-mums-the-key-to-chinese-results/story-e6frg7e6-1226277566587

Center for China and Globalization (2019) Report on employment and entrepreneurship of Chinese returnees in 2019. Retrieved from http://www.ccg.org.cn/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CCG&tnqh_x62A5;&tnqh_x544A;-2019&tnqh_x4E2D;&tnqh_x56FD;&tnqh_x6D77;&tnqh_x5F52;&tnqh_x5C31;&tnqh_x4E1A;&tnqh_x521B;&tnqh_x4E1A;&tnqh_x8C03;&tnqh_x67E5;&tnqh_x62A5;&tnqh_x544A;(2019.11).pdf

Chen J, Sun P, Yu Z (2017) A comparative study on parenting of preschool children between the Chinese in China and Chinese immigrants in the United States. J Fam Issues 38:1262–1287

Chua A (2011) Battle hymn of the tiger mother. United States Penguin Press HC

Dou D, Shek D, Kwok K (2020) Perceived paternal and maternal parenting attributes among Chinese adolescents: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(23):8741

Elder, GH Jr (1985) Perspectives on the Life Course. In: GH Elder, Jr ed, Life Course Dynamics: Trajectories and Transitions, 1968–1980. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, pp 23–49

Elder Jr GH (1994) Time, human agency, and social-change: perspectives on the lifecourse. Soc Psychol Q 57(1):4–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786971

Erlinghagen M (2021) The transnational life course: an integrated and unified theoretical concept for migration research. Ethn Racial Stud 44(8):1337–1364

Field L (2015) Whither teaching? Academics’ informal learning about teaching in the ‘tiger mother’ university. Int J Acad Dev 20(2):113–125

Hai R (2010) The neoliberal state and risk society: the Chinese state and the middle class. Telos 151:105–128

Hays (2021) Hays South China Overseas Returnees report. Retrieved from https://www.hays-china.cn/en/hays-south-china-overseas-returnees-report

Herzog C, Handke C, Hitters E (2019) Analyzing talk and text II: Thematic analysis. In: HVD Bulck, M Puppis, K Donders, & LV Audenhove eds, The Palgrave handbook of methods for media policy research. United Kingdom Palgrave Macmillan, pp 385–401

Huang GH, Gove M (2015) Confucianism, Chinese families, and academic achievement: exploring how confucianism and Asian descendant parenting practices influence children’s academic achievement. In: M Khine ed, Science Education in East Asia. Springer, Cham

Jack G (2000) Ecological influences on parenting and child development. Br J Soc Work 30(6):703–720. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/30.6.703. Retrieved from

Jankowiak WR, Moore RL (2017) Family Life in China Cambridge. Polity Press, UK

Katz C (2018) The angel of geography: superman, tiger mother, aspiration management, and the child as waste. Prog Hum Geogr 42(5):723–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517708844

Kealy C, Devaney C (2023) Culture and parenting: Polish migrant parents’ perspectives on how culture shapes their parenting in a culturally diverse Irish neighbourhood. J Family Stud 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2023.2216184

Krzyżowski Ł, Mucha J (2014) Transnational caregiving in turbulent times: Polish migrants in Iceland and their elderly parents in Poland. Int Sociol 29(1):22–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580913515287

Kulu H, Milewsk N (2007) Family change and migration in the life course: an introduction. Demogr Res 17:567–590. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2007.17.19

Le H, Ceballo R, Chao R, Hill N, Murry V, Pinderhughes E (2008) Excavating culture: detangling ethnic differences from contextual influences in parenting. Appl Dev Sci 12(4):163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888690802387880

Lee AS (1974) Return migration in the United States. Int Migr Rev 8(2):283–300

Leese S (2011) A ‘Tiger mother’ rebuttal from across the ocean. Retrieved from http://www.cnngo.com/hong-kong/life/samantha-leese-138468

LeVine RA (1980) Anthropology and child development. In: C Super & S Harkness eds, Anthropological perspectives on child development. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

LeVine RA (1988) Human parental care: Universal goals, cultural strategies, and individual behavior. In: RA LeVine, PM Miller, & M Maxwell eds, Parental behavior in diverse societies. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA

Li Y, Wang U, Luo L (2020) Family migration and educational outcomes of migrant children in China: the roles of family investments and school quality. Asia Pacifc Educ Rev 21:505–521

Lichtman LJ (2011) A practical guide for raising a self-directed and caring child: an alternative to the tiger mother parenting style. iUniverse, Bloomington, IN

Lu J (2018) Of Roses and Jasmine—auto-ethnographic reflections on my early bilingual life through China’s Open-Door Policy. Reflective Pract 19(5):690–706

Lu J (2020) Cinderella and Pandora’s box—autoethnographic Reflections on My Early Career Research Trajectory between Australia and China. Interlitteraria 25(1):96–109

Lu J, Huang Y, Chen J (2023) Parental knowledge, preference and needs of child-rearing family programmes: a case in Chinese Inner Mongolia minority region. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(1):434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010434

Ma J (2020) Parenting in Chinese immigrant families: a critical review of consistent and inconsistent findings. J Child Fam Stud 29:831–844

Ma L, Tan Y, Li W (2023) Identity (re)construction, return destination selection and place attachment among Chinese academic returnees: a case study of Guangzhou, China. Cities. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104563

Miao L, Wang H (2017) Reverse migration in China: contemporary Chinese returnees. In: International Migration of China. Springer, Singapore

Mistry RS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, McLoyd VC (2002) Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Dev 73(3):935–951. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00448

MOE (2019) Statistics on Chinese learners studying overseas in 2019 [2019年度我国出国留学人员情况统计]. Retrieved from http://en.moe.gov.cn/news/press_releases/202012/t20201224_507474.html

Mu GM (2023) Language-in-education and sociology of resilience for child (Im)migrants: the cases of India, China, and Australia. In: WO Lee, P Brown, AL Goodwin, & A Green eds, International Handbook on Education Development in the Asia-Pacific. Springer, Singapore

Orrenius PM (1999) Return migration from Mexico: theory and evidence. (PhD). University of California, Los Angeles

Palaiologou N (2007) School adjustment difficulties of immigrant children in Greece. Intercult Educ 18(2):99–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675980701327205

Ran, Y (2023) Talented returnees benefit from new lives In China. China Daily

Rogoff B (2014) Learning by observing and pitching in to family and community endeavors: an orientation. Hum Dev 57(2-3):69–81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356757

Salaff JW, Greve A (2013) Social networks and family relations in return migration. In: C Kwok-bun ed, International Handbook of Chinese Families. Springer, New York, USA

Santos G (2021) Chinese village life today. building families in an age of transition. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington

Selin H (2022) Parenting across cultures (2nd ed). Springer Nature, Switzerland

Su W (2023) “Lie Flat”—Chinese youth subculture in the context of the pandemic and national rejuvenation. J Media Cult Stud org/10.1080/10304312.2023.2190059

Suzuki M (1995) Success story? Japanese immigrant economic achievement and return migration,1920-1930. J Econ Hist 55(4):889–901

Tan C (2017) Confucianism and education. In: G Walford ed, Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 1–18

Tualaulelei E, Taylor-Leech K (2021) Building positive identities in a culturally safe space: an ethnographic case study from Queensland, Australia. Diaspora, Indigenous. Minor Educ 15(2):137–149

Vanderkamp J (1972) Return migration: its significance and behavior. West Econ J 10(4):460–465

van Wissen LJG, Dykstra P (1999) Epilogue: New directions in population studies. In: LJG van Wissen & PA Dykstra eds, Population issues: An interdisciplinary focus (pp. 265-275). New York: Springer

Warren R (2024) After a decade of decline, the US undocumented population increased by 650,000 in 2022. J Migr Human Secur 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331502424122662

Xu Y, Farver JAM, Zhang Z, Zeng Q, Yu L, Cai B (2005) Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent–child interaction. Int J Behav Dev 29(6):524–531. http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/pp/01650254.html

Yao K (2020) What We know about China’s ‘Dual circulation’ economic strategy. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/china-economy-transformation-explainer/

Yeh C, Agarwal-Rangnath R, Hsieh B, Yu J (2022) The wisdom in our stories: Asian American motherscholar voices. Int J Qual Stud Educ 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2022.2127010

Zhu Y (2011) “虎妈”不代表中国教育方式. Tiger mother does not represent Chinese education. 北京晚报 [Beijing Evenings]. Retrieved from http://www.edu.cn/zong_he_news_465/20110309/t20110309_585584.shtml

Zhu Y (2020) Transnationalizing lifelong learning: taking the standpoint of Chinese immigrant mothers. Glob Soc Educ 18(4):406–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2020.1762168

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This is a single-author paper. The named author has planned and undertaken the research and written all sections of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The ethical application was approved by the research ethics committeeXi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University. It adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the University’s principles and research guidelines. The Institutional Ethical Review Board of the university approved the project, granting it the reference number 1000036320220824173834. Name of the approval body (e.g. institutional review board (IRB) or national r, or similar). Date of approval: 29/09/2022. Scope of approval: Humanity and Social Sciences.

Informed consent

Written informed consent forms were obtained from all the participants. All the participant volutairly joined in the research. The consent describe the purpose of the research, participation, potential risk, data use, and consent to publih. All the participants undertood that the research results were only used for research purpose. No vulnerable individuals in this study. The consent forms were obtained on July 10, 2023.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, J. China’s returned migrant parents’ perspectives on how culture shapes their parenting in a culturally diverse community. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 769 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05170-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05170-7