Abstract

Extant studies on wellness tourism have focused on tourists’ motivations and current economic circumstances, while less attention has been given to the impact of childhood socio-economic status on wellness tourism intention. Under the theoretical lens of life history theory, this study examined the influence of tourists’ childhood socio-economic status on their wellness tourism intention via questionnaire surveys (N1 = 530, N2 = 524) using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and necessary condition analysis (NCA). The PLS-SEM result attested that tourists’ life history strategy and perceived value of wellness tourism serially mediate the relationship between their childhood socio-economic status and wellness tourism intention. The NCA results showed that the perceived value is a necessary condition for wellness tourism intention. The results provide an additional explanation to the tourists’ consumption behavior in wellness tourism, which bears practical implications for marketers and operators in this industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wellness tourism is renowned for its capacity to enhance overall personal well-being (Kim et al. 2024). According to Global Wellness Institute (2023), the global wellness tourism industry has reached a value of $651 billion by 2022 and is expected to grow at an average rate of 16.6% per year. The future growth potential of the wellness tourism is thus promising. Smith and Kelly (2006) emphasize that wellness tourism involves deliberate efforts to enhance one’s wellness. Specifically, traveling on a healing retreat to intentionally enhance one’s overall well-being is considered a form of wellness tourism (Dillette et al. 2021). The traditional definition of wellness tourism has evolved too from a focus on physical health to holistic wellness (Kazakov and Oyner, 2021). Although the global COVID-19 had a detrimental effect on the tourism industry as a whole, it has served as an impetus for a shift in focus to the importance of personal wellness (Yao et al. 2023). In addition, the increasing attention to the importance of adopting a healthy lifestyle leads to a burgeoning growth of the wellness tourism too (Yu et al. 2021). Some scholars have turned to positive psychology to understand how traveling can enhance an individual’s well-being (Filep and Laing, 2019). Research has shown that tourists who engaged in wellness tourism are motivated by a variety of factors, not only seeking happiness, but also relaxation, escaping stress, and importantly pursuing a healthy lifestyle in which changes are made physically and mentally after trips (Lee et al. 2020).

In recent years, wellness tourism in China has grown exponentially, becoming a significant contributor to the country’s tourism industry (Zhong et al. 2023). This expansion can be attributed to a number of factors, including increased individual affluence, people’s increased health awareness, and lifestyle changes (Li and Gao, 2024; Zhong et al. 2024). Prior research has demonstrated that variables such as tourists’ motivation to travel (Gan et al. 2023), tourists’ attitude (Zhou et al. 2023) and current economic circumstances (Li and Gao, 2024) exert a significant influence on individuals’ preferences for wellness tourism. However, these studies have largely overlooked some equally crucial factors that stem from an individual, such as their childhood experiences. Life history theory (LHT) in evolutionary psychology is an alternative lens to examine people’s intentions for engaging in wellness tourism. The theory emphasizes that an individual’s decision-making for growth, development, and sexual reproduction is influenced by the internal and external resources at the individual’s disposal (Giudice et al. 2015). To effectively adapt to the living environment, individuals rationally allocate their limited energy, resources, and time to optimize their physical and mental development (Kaplan and Gangestad, 2015). The LHT may help analyze how individuals make adaptive behavioral choices after weighing the tradeoffs of different developmental scenarios (Giudice et al. 2015). By the same token, LHT might lead tourists to have a predilection for wellness tourism. It is due to the fact that among the different forms of tourism, wellness tourism focuses more on increasing people’s awareness of their holistic wellness (Kazakov and Oyner, 2021). The post-travel impacts of wellness tourism include generating positive changes in one’s health lifestyle and better ability to cope with anxiety and prolonged illnesses (Heung and Kucukusta, 2013).

Surprisingly, little research has adopted LHT in understanding tourists’ motivation, especially on how LHT would influence tourists’ intention to engage in wellness tourism. The current study aims to address this gap by investigating the relationship between childhood socio-economic status (SES), life history strategies, and perceived value of wellness tourism on wellness tourism intention through the use of partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM). In addition, this study adopted necessary condition analysis (NCA) to complement as NCA can identify the extent of a necessary condition that needs to have for achieving an optimal outcome (Dul, 2016). It is also an effective way to explain the role of path analysis in the structure of the variables. Findings complement the existing literature by explaining the influences of tourists’ childhood SES on wellness tourism consumption (Li and Gao, 2024). Practical implications may shed light on the design of wellness tourism products and services.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Life history theory

One of the most influential theories in evolutionary psychology is life history theory (Sear, 2020). It provides a comprehensive framework for explaining how individuals allocate their limited resources to accomplish developmental tasks, enhance their adaptability for better survival (Belsky et al. 1991; Ellis et al. 2009; Kaplan and Gangestad, 2015). As individuals need to address the issue of how to survive better in their social environment, they may develop different life history strategies depending on how they allocate their resources and energy, in which a slow-to-fast continuum is proposed (Figueredo et al. 2006). Individuals make trade-offs among different intrinsic needs, which can be categorized into two groups: (1) for growth and development, including body repair and maintenance; and (2) for reproduction as a means to extend one’s life via DNA implantation (Ellis et al. 2009). Since people grow up in different environments, and those who grow up from scarce resource environments, they often encounter many life-threatening issues and therefore have a higher propensity to invest more resources in reproduction for extending their lives. Those individuals are known as fast strategists. In contrast, those who grow up in favorable environments and have more resources at their disposal can invest more effort and time in personal growth and development. Those individuals are known as slow strategists (Han and Chen, 2020). Individuals who adopt a fast strategy, tend to devote more time and energy to reproductive activities, favoring short-term gains. Conversely, individuals who adopt a slow strategy, tend to prioritize long-term gains over immediate and short-term gains (Chang et al. 2021; Figueredo et al. 2005). Life history theory has been widely applied in various psychological and behavioral studies, particularly in the context of individual decision-making and health-related outcomes (Fennis, 2022; Han and Chen, 2020). In the Chinese context, some studies have examined life history theory in relation to economic decision-making, social behaviors, and mental health (Gong et al. 2023; He et al. 2022; Li and Cao, 2023; Zhang and Wu, 2022). These studies provide valuable insights into how childhood and socio-economic factors in China shape individuals’ life history strategies, which in turn influence their behavioral patterns. Building on these insights, this study aims to extend the application of life history theory to the field of wellness tourism in China. In the context of wellness tourism, LHT may provide a compelling framework for understanding how different individuals’ life history strategies might influence their motivations and behaviors. Wellness tourism is a form of tourism which emphasizes the physical and mental health of tourists (Kazakov and Oyner, 2021), may appeal to individuals based on their life history strategies. For example, individuals from resource-rich environments (slow strategists) may place a higher value on long-term wellness, potentially leading to a greater interest in wellness tourism. In contrast, individuals from resource-poor environments (fast strategists) may prioritize more immediate and short-term benefits, which could also influence their engagement in wellness tourism. Therefore, LHT may support tourists’ preference for wellness tourism.

Childhood socio-economic status and wellness tourism intention

Socio-economic status (SES) refers to an individual’s social position based on income, education, and occupational prestige (Kraus et al. 2012). Childhood SES refers to an individual’s self-reported evaluation of their SES in their childhood period from 1 to 13 years old. Research has shown that a person’s childhood SES is typically a strong predictor of an adult’s behavior than the adult SES, particularly on those accumulated habitus behavior (Boylan et al. 2018). Bradshaw et al. (2017) reported that childhood SES has enduring consequences for an adult’s life outcomes and behavior, in particular some behavior and preferences that are formed since one’s early life stage, reflecting an individual’s accumulated behavioral pattern. Ellis et al. (2017) report that childhood stress has long-lasting, negative effects that would lead individuals to adopt a fast life history strategy during adulthood. This is because childhood experiences are consequential to individuals’ response patterns to their environment, which in turn affects adults’ behavior (Thompson et al. 2020). Studies have shown that individuals who have higher SES have a higher propensity to engage in tourism (Gu et al. 2016; Hryhorczuk et al. 2019). Wellness tourism, as a type of tourism that focuses on the holistic wellness of tourists, activities are meant to contribute to the tourists’ long-term wellness (Kazakov and Oyner, 2021). Therefore, people who are more concerned about their physical and mental health might care more for long-term benefits rather than instant awards. In other words, they are more likely to accept delayed gratification and engage in wellness tourism (Farkić and Taylor, 2019). Research has shown that tourism experiences are positively associated with better self-rated health among the Chinese (Gu et al. 2016), and childhood SES has been shown to predict a stronger willingness to adopt delay gratification than adult SES (Griskevicius et al. 2011). Wellness tourism promotes delayed rewards to tourists’ holistic wellness by inducing changes after a trip, rather than the immediate ones. Therefore, we posit that:

H1: Childhood SES positively impacts individuals’ intention to engage in wellness tourism.

Childhood socio-economic status and life history strategy

In the life history of an individual, childhood plays a crucial role. The SES is influential to an individual’s growth in his or her life history (Chang et al. 2021). Individual resources and energy allocation contribute to the diversity of life history strategies (Kaplan and Gangestad, 2015). The LHT suggests that individuals form and adjust their resources allocation strategies according to their early life circumstances and anticipate future growth conditions to adapt more effectively to their environment (Giudice, 2009). Individuals who grow up from poor environments and have insufficient resources, tend to emphasize short-term rewards and opportunities. Those individuals as such are known as “fast strategists” (Han and Chen, 2020); conversely, individuals who grow up from good environments tend to emphasize more on long-term development. Those individuals are often known as “slow strategists” (Belsky and Pluess, 2009a, 2009b). While most scholars measure life history strategy (LHS) as unidimensional, Sai et al. (2022) identified three dimensions of LHS, including intimate attention, social connectedness, and thoughtfulness. Thoughtfulness represents an individual’s ability to plan ahead and think about the future; intimate attention represents an individual’s ability to have a close and warm partnership and parent-child relationship; and social connectedness represents an individual’s level of closeness to family and friends (Sai et al. 2022). As a core variable of LHT, LHS is a stable pattern of psychological behavior formed by an individual’s childhood life experiences (childhood SES), and as Bradshaw et al. (2017) reported that childhood SES has enduring impacts on adults’ behavior. Based on those early experiences, the individual is experienced and knows how to achieve optimal trade-offs among various options of resource allocations (Wang and Hou, 2017). According to the above discussion, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H2: Childhood SES positively impacts individuals’ life history strategy.

Childhood socio-economic status and perceived value of wellness tourism

Tourist’s perceived value of wellness tourism refers to the result of measuring what benefits that the travelers would receive after traveling (Dai et al. 2022). The perceived value of tourists plays a significant role in their decision-making process when selecting a specific type of tourism or attractions to visit (Carvache-Franco et al. 2021). If tourists prioritize the long-term impact on their health, they are more likely to value the health-promoting benefits of wellness tourism. Moreover, it has been shown that individuals’ childhood SES influences their preferences. Individuals with higher childhood SES typically choose delayed rewards (Griskevicius et al. 2011). People’s awareness of holistic wellness does not happen overnight, and often the positive changes induced by wellness tourism would take some time to occur after the tours, for example, wellness tourism experiences may change tourists’ healthy lifestyles and habits after the tours (Moscardo, 2011). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H3: Childhood SES positively influences individuals’ perceived value of wellness tourism.

Mediating role of the life history strategy and perceived value of wellness tourism

Based on the LHT, we further hypothesize that childhood SES can influence people’s intention of engaging in wellness tourism, which is mediated by life history strategy and the perceived value of wellness tourism. Zhang and Wu (2022) report that smartphone addiction is an ensued outcome of applying fast strategy in which the relationships between childhood adversity and problem behaviors are mediated. People who adopt slow strategy often come from well-to-do families with better grow-up environments, they value more on getting long-term gains and self-development (Giudice et al. 2015). The health benefits induced by engaging in wellness tourism usually take time to be “effective” and influential to an individual’s long-term self-development (Dillette et al. 2021). Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H4: The positive impact of childhood SES on wellness tourism intention is mediated by individuals’ life history strategy.

Perceived value is an important mediating variable in tourism studies. Research has shown that perceived value is a mediator of tourist motivations and intentions in wellness tourism (Gan et al. 2023). Tourists may have higher wellness tourism intentions if they perceive the quality of wellness products and services as adequate (Carvache-Franco et al. 2021). Research shows that individuals with more travel experience tend to come from higher family SES (Gu et al. 2016; Hryhorczuk et al. 2019). If people perceive the cost of undertaking wellness tourism could help improve their health, they may perceive the value of wellness tourism highly, resulting in a higher intention to engage in wellness tourism (Elbaz et al. 2023; Liu et al. 2022). Thus, we posit that:

H5: The positive impact of childhood SES on wellness tourism intention is mediated by individuals’ perceived value of wellness tourism.

A serial multiple mediation model

This article further examines if the effect of childhood SES on wellness tourism intention will be mediated, in order, by life history strategy and perceived value of wellness tourism. Research shows that people who have higher childhood SES tend to put more emphasis on future gains and consider more about future outcomes (Chang et al. 2021; Griskevicius et al. 2011; Wang and Hou, 2017). According to the LHT, we hypothesize that an individual’s childhood SES positively predicts the development of a slow strategy (Belsky and Pluess, 2009b), because individuals who grow up in favorable environments face fewer threats, they are less likely to develop a scarcity mentality, and are more likely to develop a slow strategy (Giudice et al. 2014); It is reported that individuals who adopt a slow strategy can yield long-term gains and fitness rewards (Griskevicius et al. 2011). Wellness tourism emphasizes the ongoing impact on an individual’s health. In particular, those who value the benefits brought about by wellness tourism are the ones who prefer to adopt slow strategy in their life-health planning (Kazakov and Oyner, 2021). As a result, they may have a higher perceived value of wellness tourism and choose to engage in wellness tourism (Carvache-Franco et al. 2021). We thus propose:

H6: The positive impact of childhood SES on wellness tourism intention is sequentially mediated by individuals’ life history strategy and perceived value of wellness tourism.

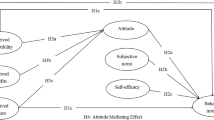

The conceptual model is presented in Fig. 1.

Methodology

Data collection

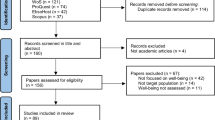

To study wellness tourism, we selected wellness hotels as the original context for our study. Wellness hotels, particularly those offering spa services, hot springs, and other health-related facilities, are a key component of the wellness tourism experience. These types of accommodations are often regarded as one of the main representatives of wellness tourism, as they provide services that promote relaxation and rejuvenation (Dini and Pencarelli, 2021; Han et al. 2020). This makes them an ideal setting for exploring the motivations and behaviors of wellness tourists. Some prior studies have employed wellness hotels, including those with spas and hot springs, as the primary research contexts for understanding wellness tourism (Chen et al. 2023; Han et al. 2020; Xia et al. 2024). Before the formal data collection, a pilot test was conducted in early November 2023 to evaluate the clarity and reliability of the survey instruments. Ten university students participated in this pilot test. Backward translation between English and Chinese was performed. A few words in Chinese were improved for better clarity. All scales demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.80, and over 90% of the items were rated as understandable. The pilot data were used exclusively to refine the questionnaire, and no responses from the pilot test were included in the main data analysis.

The formal survey (Study 1) was conducted between November 30 and December 29, 2023. According to Wang et al. (2019) about seasonality of hotel demands in China, November was regarded as low travel season while December in those first-tier cities were considered as high season. Travel China Guide (2023) states similarly that Chinese hotel rates are usually higher in the peak travel season from April to October, while November to March is in the low season, except December, due to international arrivals during Christmas. The questionnaires were distributed to tourists who stayed in 4 wellness hotels located in eastern, southwestern, southern, and northern China through an online survey. Respondents were those who had engaged in wellness tourism. A filtering question was set to ensure that all respondents had experienced wellness services at the hotels at least once. A total of 600 surveys were distributed, of which 530 were valid responses (88.33%).

However, recognizing the need for a more diverse sample, we expanded our data collection in Study 2. We further expanded our data collection by recruiting additional respondents through the Credamo (https://www.credamo.com/), a professional questionnaire collection platform. This sample included participants who had experienced wellness tourism in China. Data collection was conducted between November 29 and December 13, 2024, ensuring a more diverse and representative sample of wellness tourism experiences across China. The inclusion of this data allows us to strengthen the generalizability and robustness of our findings. A filter question was used to ensure that all respondents had experienced wellness tourism at least once. A total of 600 surveys were distributed, with 524 valid responses (87.33%).

Measurements

The Childhood SES section involved four items (Wang and Hou, 2017). The life history strategy section contained 17 items and was measured as a second-order formation structure: intimate attention (1–6 items), social connectedness (7–10 items), and thoughtfulness (11–17 items) based on previous research conceptualizations, with higher scores indicating that subjects tend to be slow strategists (Sai et al. 2022; Wang and Hou, 2017). The perceived value section included 12 items (Gan et al. 2023). The wellness tourism intention section consisted of 6 items (Gan et al. 2023). These constructs were measured on a seven-point Likert scale. Appendix provides details for the items and constructs.

Data analysis

There are two types of conditions: sufficient and necessary. Sufficient condition analysis means that the antecedents fully generate the result, while necessary condition analysis means that the result will not happen in the absence of the antecedent (Dul, 2016).

The regression analysis examines the sufficient conditions between the variables. The PLS-SEM was used to investigate complex connections among constructs and indicators in the current study (Hair et al. 2021). In addition, the LHT has been scantly applied in tourism research. The current paper is thus of an exploratory nature to test the theoretical framework from a predictive perspective, and PLS-SEM can deal with higher-order constructs (Hair et al. 2021). For those reasons, PLS-SEM is an appropriate method to use in our study (Becker et al. 2023; Hair et al. 2021).

The NCA analyzes the necessary conditions between the variables. The presence or absence of a necessary condition leads directly to the presence or absence of a result (Dul et al. 2020). This method is a good complement to the traditional regression method, which emphasizes sufficient conditions. Therefore, we employed PLS-SEM in combination with NCA (Dul, 2022). Data analysis was conducted using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al. 2024) and R 4.3.1 software.

Results

Descriptive analysis

The respondents’ profiles are presented in Table 1. Most of the respondents are young consumers, Generation Y and Z, who represent the powerful consumption force in China (Zhang et al. 2022). Regarding respondents’ income, there is a huge economic diversity in China. TimeCamp (2024) reported that Chinese people’s monthly salary as of 2023 ranged from 7410 CNY as the lowest average salary to a maximum average monthly salary of about 131,000 CNY. The figures reported are in general in line with the ones presented by the National Bureau of Statistics (2023) that the average monthly income was about CNY 7500. In this regard, our current sample represents Chinese people’s average income and their income tends to fall within the medium range.

Common method bias test

All questionnaires used in this study are subject self-reported, which may cause common method bias, and therefore, a common method bias testing was performed. Harman’s single-factor test was used to test the common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2012). The results showed that the variation explained by the first factor was 35.37% (Study 1) and 32.22% (Study 2), which was less than the threshold of 50%. Then, we conducted a full-collinearity test (Kock, 2015), which revealed that the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for all the latent constructs ranged from 1.01 to 1.21 (Study 1) and 1.01 to 1.33 (Study 2). These values were below the 3.3 threshold for pathological VIF. Therefore, the results indicated that there was no serious common method variance in our study.

Measurement model

The measurement model is evaluated through reliability and validity tests (see Table 2). The composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha measures were used for reliability verification, with values ≥ 0.70 (Hair et al. 2021). In terms of validity testing, the assessment of convergent and discriminant validity was implemented. For convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) and factor loadings were evaluated. The AVE values must be ≥0.50, while the factor loadings should show values ≥ 0.70. As long as AVE values were greater than 0.5, items with loadings between 0.5 and 0.7 were retained (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Table 2 shows that factor loadings and CR values were all within the acceptable range. All AVEs were above 0.5, indicating good construct reliability. Discriminant validity was also tested using the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). As indicated in Table 3, the square root of all AVE values exceeds 0.7, which is higher than all cross-correlation scores. The findings supported the earlier assessment that there is adequate discriminant validity. Table 4 illustrates the weight and significance of the formative indicators of LHS. To ascertain the significance of the weights of the formative indicators, a 5000 resample bootstrap was employed. The results demonstrate that all the weights of the indicators are significant at the p < 0.001 level (Hair et al. 2021), thereby illustrating the relative contribution of the formative indicators to the creation of a second-order construct. Furthermore, multicollinearity was not identified (VIF < 3.3) between variables (Hair et al. 2021). The model fit was evaluated through the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value, and the SRMR value obtained in this study was 0.05 (Study 1) and 0.06 (Study 2), which less than the cutoff value of 0.08 (Henseler et al. 2015), indicating that the model fit criterion was met.

Structural model test

Table 5 presents the path coefficients and t-values for each path in both Study 1 and Study 2. In Study 1, as hypothesized, CSES had a significant positive effect on LHS (β = 0.32, p < 0.001), confirming H2. Similarly, CSES was positively associated with PV (β = 0.13, p < 0.01), supporting H3. However, the direct relationship between CSES and WTI was not statistically significant (β = 0.06, p > 0.05), meaning that H1 was not supported in this sample. In Study 2, CSES also had a significant positive effect on LHS (β = 0.44, p < 0.001), supporting H2. Similarly, CSES was positively associated with PV (β = 0.11, p < 0.05), confirming H3. The direct effect of CSES on WTI in Study 2 was not statistically significant either (β = 0.04, p > 0.05), thus H1 was not supported in this sample as well.

Table 5 also shows the results of the mediation effects in both studies. In Study 1, the indirect effect of CSES on WTI through LHS was 0.05 (95% CI = 0.03, 0.08), supporting Hypothesis 4. The indirect effect through PV was 0.09 (95% CI = 0.03, 0.15), supporting Hypothesis 5. The combined indirect effect through LHS and PV was 0.08 (95% CI = 0.05, 0.11), confirming Hypothesis 6. In Study 2, the indirect effect of CSES on WTI through LHS was 0.09 (95% CI = 0.20, 0.34), supporting H4. The indirect effect through PV was 0.06 (95% CI = 0.01, 0.11), supporting H5. The combined indirect effect through LHS and PV was 0.15 (95% CI = 0.10, 0.21), supporting H6. Importantly, none of the 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects in either study included zero, indicating that all mediation effects were significant. These findings suggest that the relationship between CSES and WTI was fully mediated by LHS and PV in both studies. Specifically, childhood SES influenced wellness tourism intention primarily through the mediating variables of life history strategy and perceived value (see Figs. 2 and 3).

Necessity analysis results

In addition to determining whether a particular condition is necessary for a particular outcome, NCA can examine the effect size of the necessary condition. The effect size represents the strength of the relationship between the condition and the outcome, with a higher value indicating a greater effect. It ranges from 0 to 1, with values below 0.1 indicating a small effect (Dul, 2016). Both continuous and discrete variables can be handled by the NCA method. Moreover, recent research has proposed the use of PLS-SEM in conjunction with NCA for analytical purposes (Richter et al. 2020). In summary, the initial step was to utilize PLS-SEM to assess the data for reliability, validity, covariance, and hypothesis testing. This was done to initially confirm that the data are suitable for further analysis. The results of the aforementioned content demonstrate that our data is consistent with the requirements. Subsequently, an importance-performance map analysis was conducted, whereby the original variable scores are interpreted in the form of percentage values from 0 to 100. The newly generated data was then processed using R software to perform NCA (Hauff et al. 2024).

In NCA, the effect size is typically obtained through the Ceiling Regression - Free Disposal Hull (CE-FDH) and Ceiling Envelopment - Free Disposal Hull (CR-FDH) estimation methods. CE-FDH is the more prevalent method for NCA of Likert scales (Hauff et al. 2024). In the NCA approach, two essential conditions must be met: the effect size (d) should not be less than 0.1 (Dul, 2016), and the effect size must be significant (Dul et al. 2020). Table 6 presents the effect sizes and their associated significance levels for the necessary conditions affecting WTI in both Study 1 and Study 2. The results of Study 1 indicated that PV had a large effect size (d = 0.31, p < 0.001), thereby confirming that PV is a necessary condition for WTI. Similarly, in Study 2, PV also demonstrated a significant effect size (d = 0.27, p < 0.001), indicating that it is a necessary condition for WTI. LHS exhibited moderate effect sizes in both studies (d = 0.12 in Study 1, d = 0.15 in Study 2), though it was not a necessary condition in Study 1 (p > 0.05). In contrast, it was a significant factor in Study 2 (p < 0.001). Table 7 presents the bottleneck levels (based on the rescaled PLS-SEM variable scores from 0 to 100), indicating the minimum necessary levels of each variable to achieve a specified percentage of WTI. In Study 1, to achieve 80% of WTI, the LHS needs to reach 46.9% and the PV needs to reach 34.7%. In Study 2, to achieve 80% of WTI, LHS should be at 22.9%, and PV at 60.7%. Both LHS and PV are key to driving WTI, with the bottleneck levels highlighting their importance.

Discussion

General discussion

From the perspective of life history theory, this study presented a multiple mediation model with life history strategy and perceived value as the mediating variables. Moreover, this study used the NCA method to assess that the “perceived value” is a necessary condition for wellness tourism intention. The research results support the majority of the research hypotheses and have certain theoretical and practical implications for deepening research on the relationship between wellness tourism intention and childhood SES.

Life history strategy mediated the relationship between childhood SES and wellness tourism intention. Individuals who adopt a slow strategy tend to prioritize their long-term gains (Figueredo et al. 2006), and they prefer health-related services that have a long-lasting impact (Du et al. 2021). Research has shown that a family with limited financial resources would limit positive adolescent development (Ye et al. 2020) and make it difficult for adolescents to plan for the future (Chen et al. 2021). It is due to the fact that children and adolescents generally do not have their own financial resources, and the economic condition of their families is often used as an indicator of childhood SES (Belsky et al. 2012). Family environment is, therefore, consequential to the perception of long-term benefits (Moscardo, 2011). Our research found that people who adopt a slow strategy in their life planning had a higher intention to engage in wellness tourism and that thoughtfulness accounted for the largest weight of the life history strategy, which is consistent with the notion of considering long-term benefits (Sai et al. 2022). Having difficulties surviving well due to insufficient resources makes children from poor families have a weaker ability to resist the impulse for immediate rewards. Therefore, delayed gratification may not be adopted by those poor children, and likewise for wellness tourism. In the NCA analysis, the life history strategy demonstrated moderate effect sizes in both studies, thereby indicating its relevance across various contexts. The necessity condition for life history strategy was not a significant factor in Study 1; however, it was a significant factor in Study 2. The difference may be attributed to the broader scope and diversity of the sample in Study 2. Study 1 focused on wellness hotels in major cities, which primarily provide spa-like wellness experiences that can quickly alleviate physical and mental fatigue and provide immediate wellness benefits (Dini and Pencarelli, 2021; Han et al. 2020). In contrast, Study 2 recruited respondents from a national sample that may have included individuals engaged in diverse wellness activities, such as outdoor activities in rural or semi-rural areas. These types of activities often require more preparation and engagement on the part of visitors to obtain the long-term wellness benefits that are more closely associated with them (He et al. 2023; Liu et al. 2024), so “slow strategists” may be more relevant in this case. These findings underscore the importance of sample diversity and highlight how contextual differences in wellness tourism activities may influence the relevance of life history strategy.

This article found that perceived value has a positive effect on wellness tourism intention, which is in line with the findings of some previous research (Gan et al. 2023; Moscardo, 2011). Furthermore, the NCA results showed that perceived value is a necessary condition for wellness tourism intention. Research suggests that individuals are more likely to choose wellness tourism when they perceive positively its physical or psychological value (Dai et al. 2022; Habibi and Rasoolimanesh, 2021). Individuals with higher childhood SES tend to have higher adult SES (Sherman et al. 2013), and a well-to-do family background constitutes a better childhood environment, which can engender individuals’ appreciation and longing for long-term wellness benefits (Malmberg, 2001).

Childhood SES influences wellness tourism intention mainly through the mediating variables of life history strategies and perceived value. Findings as such corroborate some previous studies that childhood SES can influence an individual’s travel decisions (Kim et al. 2021). This is consistent with earlier studies that individuals who grow up with higher childhood SES face fewer threats, so they tend to have a less scarcity mindset and are more likely to adopt a slow strategy (Giudice et al. 2015). There is also research suggesting that individuals with lower childhood SES are more sensitive to scarce information in hotel reservations (Park et al. 2022). People as such, may therefore perceive a higher value in wellness tourism, resulting in higher wellness tourism intention (Carvache-Franco et al. 2021).

Theoretical implications

Based on the life history theory, this study developed a moderated multiple mediation model that elucidates the pathways between childhood SES and wellness tourism intention. In particular, our findings suggest that there is a positive impact of childhood SES on wellness tourism intention as it is sequentially mediated by individuals’ life history strategy and perceived value of wellness tourism. Previous studies have primarily investigated the impact of tourism motivation on wellness tourism (Gan et al. 2023; Lee et al. 2020). This study is one of the few attempts which explain how childhood SES affects tourists’ wellness tourism intention. While many researches have demonstrated that tourists’ current SES affects their travel behavior and consumption (Gu et al. 2016; Hryhorczuk et al. 2019), surprisingly very few studies examine the role of childhood SES as it is regarded as an effective predictor of adults’ behavior (Boylan et al. 2018; Thompson et al. 2020). The current study is also one of the few exceptions to apply LHT in tourism research, which extends the understanding regarding the impact of tourists’ childhood SES, life history strategies on wellness tourism intention. Findings show that childhood SES can influence tourists’ wellness tourism intention via two important mediating variables. It supported the indirect effects of childhood SES on wellness tourism intention via life history strategy and perceived value (CSES → LHS → PV → WTI). This mediating sequence provides insights into the underlying relationship between childhood SES and wellness tourism intention. Findings as such complement the existing literature and sheds light on the importance of childhood SES in wellness tourism literature. Moreover, this study utilized both PLS-SEM and NCA methods to provide a comprehensive and complementary perspective for getting a better theoretical understanding of the influence of childhood SES on wellness tourism intention. The NCA findings also highlight the importance of perceived value and life history strategy.

Practical implications

Understanding the mindset and needs of tourists can improve their patronage intention of wellness tourism. The research has reported that tourists who participate in wellness tourism often seek to enhance their physical and mental health (Dillette et al. 2021). The current research shows that individuals who adopt slow strategies value long-term gains and have a higher propensity to patronize wellness tourism products or services. Findings are in line with some previous research (Habibi and Rasoolimanesh, 2021; Wang and Leou, 2015). Promotional details should focus more on the perceived value induced by wellness tourism. While industry practitioners endeavor to design wellness tourism products and services that would ‘sound attractive’ to the targeted customers based on their current SES profiles, such as an individual’s career and income. The current research sheds light on the importance to collect more information on tourists’ childhood SES as it is influential to one’s life history strategies, which would affect tourists’ wellness tourism intention. While it is difficult to understand clients’ childhood SES in the short run, it is conducive for tourism operators who work in the front (e.g,. tour guide) and often have extended conversations with the clients to bear this knowledge in mind, and note down their observations of the clients’ childhood SES. This might be useful to the operators’ future deployment of marketing tactics toward this group of people. For hoteliers, when a traveler registers for a membership, additional demographic information that can reflect a tourist’s childhood SES data should be collected, such as the educational attainment and occupations of the traveler’s parents during their childhood (Link et al. 2017). Information as such can help industry practitioners to perform accurate assessments of their clients’ profiles in order to produce wellness tourism products that can better be in line with tourists’ life history strategies.

Limitations and future research directions

There are several limitations. First, this study only used the questionnaire survey method, which was a one-time event. Future research may wish to conduct a longitudinal mixed-methods study to examine how the impact of SES on tourists’ wellness tourism intention would morph over time. Second, the insignificant effect of childhood SES on wellness tourism intention may be due to the limitations of relying on retrospective reports. In this study, childhood SES was measured using Likert scales based on participants’ recollections of their early life experiences. This self-report method may not capture the full extent of childhood SES and its nuanced effects on outcomes such as wellness tourism intention. To improve the precision of future studies, it would be beneficial to include more objective indicators of childhood SES, such as parental occupation and educational attainment during participants’ childhood (Link et al. 2017). Third, our study primarily examines the economic situation of respondents during their childhood stage. Future studies might benefit by including other childhood factors in the research agenda. For instance, research has demonstrated that childhood adversity, including child abuse and emotional neglect, can be consequential to an individual’s life history strategy (Zhang and Wu, 2022). These factors might influence not only broader life outcomes but also specific behaviors, such as wellness tourism intention.

Data availability

The data analyzed in this study are not publicly available due to the confidentiality commitments made to survey participants. These data were collected under strict privacy agreements, as explicitly stated in the informed consent process, where we guaranteed the protection of respondents’ personal information. The anonymized data can be made available to qualified researchers upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to ethical review and compliance with our privacy commitments.

References

Becker J-M, Cheah J-H, Gholamzade R et al. (2023) PLS-SEM’s most wanted guidance. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 35(1):321–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2022-0474

Belsky J, Pluess M (2009a) Beyond diathesis stress: differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychol Bull 135(6):885–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017376

Belsky J, Pluess M (2009b) The nature (and nurture?) of plasticity in early human development. Perspect Psychol Sci 4(4):345–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01136.x

Belsky J, Schlomer GL, Ellis BJ (2012) Beyond cumulative risk: distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Dev Psychol 48(3):662–673. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024454

Belsky J, Steinberg L, Draper P (1991) Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Dev 62(4):647–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x

Boylan JM, Cundiff JM, Jakubowski KP et al. (2018) Pathways linking childhood SES and adult health behaviors and psychological resources in black and white men. Ann Behav Med 52(12):1023–1035. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kay006

Bradshaw M, Kent BV, Henderson WM et al. (2017) Subjective social status, life course SES, and BMI in young adulthood. Health Psychol 36(7):682–694. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000487

Carvache-Franco M, Carrascosa-López C, Carvache-Franco W (2021) The Perceived Value and Future Behavioral Intentions in Ecotourism: A Study in the Mediterranean Natural Parks from Spain. Land 10(11):1133. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10111133

Chang L, Liu YY, Lu HJ et al. (2021) Slow life history strategies and increases in externalizing and internalizing problems during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Res Adolesc 31(3):595–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12661

Chen JJ, Jiang TN, Liu MF (2021) Family socioeconomic status and learning engagement in Chinese adolescents: The multiple mediating roles of resilience and future orientation. Front Psychol 12:714346. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.714346

Chen K-H, Huang L, Ye Y (2023) Research on the relationship between wellness tourism experiencescape and revisit intention: A chain mediation model. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 35(3):893–918. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2022-0050

Dai J, Zhao L, Wang Q et al. (2022) Research on the impact of outlets’ experience marketing and customer perceived value on tourism consumption satisfaction and loyalty. Front Psychol 13:944070. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.944070

Dini M, Pencarelli T (2021) Wellness tourism and the components of its offer system: a holistic perspective. Tour Rev 77(2):394–412. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-08-2020-0373

Dillette AK, Douglas AC, Andrzejewski C (2021) Dimensions of holistic wellness as a result of international wellness tourism experiences. Curr Issues Tour 24(6):794–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1746247

Du M, Tao L, Liu M et al. (2021) Tourism experiences and the lower risk of mortality in the Chinese elderly: a national cohort study. BMC Public Health 21(1):996. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11099-8

Dul J (2016) Necessary condition analysis (NCA) logic and methodology of “necessary but not sufficient” causality. Organ Res Methods 19(1):10–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115584005

Dul J (2022) Problematic applications of Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) in tourism and hospitality research. Tour Manag 93:104616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104616

Dul J, Van der Laan E, Kuik R (2020) A statistical significance test for necessary condition analysis. Organ Res Methods 23(2):385–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118795272

Elbaz AM, Abou Kamar MS, Onjewu A-KE et al. (2023) Evaluating the antecedents of health destination loyalty: The moderating role of destination trust and tourists’ emotions. Int J Hosp Tour Adm 24(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2021.1935394

Ellis BJ, Bianchi J, Griskevicius V et al. (2017) Beyond risk and protective factors: An adaptation-based approach to resilience. Perspect Psychol Sci 12(4):561–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617693054

Ellis BJ, Figueredo AJ, Brumbach BH et al. (2009) Fundamental Dimensions of Environmental Risk: The Impact of Harsh versus Unpredictable Environments on the Evolution and Development of Life History Strategies. Hum Nat 20(2):204–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9063-7

Farkić J, Taylor S (2019) Rethinking tourist wellbeing through the concept of slow adventure. Sports 7(8):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7080190

Fennis BM (2022) Self-control, self-regulation, and consumer wellbeing: a life history perspective. Curr Opin Psychol 46:101344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101344

Figueredo AJ, Vásquez G, Brumbach BH et al. (2006) Consilience and life history theory: From genes to brain to reproductive strategy. Dev Rev 26(2):243–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.002

Figueredo AJ, Vásquez G, Brumbach BH et al. (2005) The K-factor: Individual differences in life history strategy. Personal Individ Differ 39(8):1349–1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.06.009

Filep S, Laing J (2019) Trends and directions in tourism and positive psychology. J Travel Res 58(3):343–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518759227

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Gan T, Zheng J, Li W et al. (2023) Health and wellness tourists’ motivation and behavior intention: the role of perceived value. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(5):4339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054339

Giudice D (2009) Sex, attachment, and the development of reproductive strategies. Behav Brain Sci 32(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X09000016

Giudice D, Gangestad S, Kaplan H et al (2015) Life history theory and evolutionary psychology. In: The handbook of evolutionary psychology–Vol 1: Foundations. Wiley, New York, p 88–114

Giudice D, Klimczuk AC, Traficonte DM et al. (2014) Autistic-like and schizotypal traits in a life history perspective: Diametrical associations with impulsivity, sensation seeking, and sociosexual behavior. Evol Hum Behav 35(5):415–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.05.007

Global Wellness Institute (2023) The 2023 Global Wellness Economy Monitor Data for 2019-2022. https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/the-2023-global-wellness-economy-monitor/. Accessed 09 Jan 2024

Gong Y, Li Q, Li J et al. (2023) Does early adversity predict aggression among Chinese male violent juvenile offenders? The mediating role of life history strategy and the moderating role of meaning in life. BMC Psychol 11(1):382. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01407-9

Griskevicius V, Tybur JM, Delton AW et al. (2011) The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on risk and delayed rewards: A life history theory approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 100(6):1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022403

Gu D, Zhu H, Brown T et al. (2016) Tourism experiences and self-rated health among older adults in China. J Aging Health 28(4):675–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315609906

Habibi A, Rasoolimanesh SM (2021) Experience and service quality on perceived value and behavioral intention: Moderating effect of perceived risk and fee. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour 22(6):711–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2020.1837050

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM et al (2021) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer, Heidelberg

Han H, Kiatkawsin K, Koo B et al. (2020) Thai wellness tourism and quality: comparison between Chinese and American visitors’ behaviors. Asia Pac J Tour Res 25(4):424–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2020.1737551

Han W, Chen BB (2020) An evolutionary life history approach to understanding mental health. Gen Psychiatr 33(6):e100113. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2019-100113

Hauff S, Richter NF, Sarstedt M et al. (2024) Importance and performance in PLS-SEM and NCA: Introducing the combined importance-performance map analysis (cIPMA). J Retail Consum Serv 78:103723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2024.103723

He M, Chen JH, Wu AM et al. (2022) Fast or slow: applying life history strategies to responsible gambling adherence. Int Gambl Stud 22(3):444–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2022.2035422

He M, Liu B, Li Y (2023) Tourist inspiration: How the wellness tourism experience inspires tourist engagement. J Hosp Tour Res 47(7):1115–1135. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480211026376

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43:115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Heung VC, Kucukusta D (2013) Wellness tourism in China: Resources, development and marketing. Int J Tour Res 15(4):346–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1880

Hryhorczuk N, Zvinchuk A, Shkiryak-Nyzhnyk Z et al. (2019) Engagement in tourism and personality traits among Ukrainian adolescents. J Multidiscip Acad Tour 4(2):71–76. https://doi.org/10.31822/jomat.580446

Kaplan HS, Gangestad SW (2015) Life history theory and evolutionary psychology. In: The handbook of evolutionary psychology. Wiley, New York, p 68–95

Kazakov S, Oyner O (2021) Wellness tourism: a perspective article. Tour Rev 76(1):58–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-05-2019-0154

Kim J, Giroux M, Park J et al. (2021) An evolutionary perspective in tourism: the role of socioeconomic status on extremeness aversion in travel decision making. J Travel Res 61(5):1187–1200. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211024738

Kim M, Moon H, Joo Y et al. (2024) Tourists’ perceived value and behavioral intentions based on the choice attributes of wellness tourism. Int J Tour Res 26(1):e2623. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2623

Kock N (2015) Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collab 11(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Kraus MW, Piff PK, Mendoza-Denton R et al. (2012) Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: how the rich are different from the poor. Psychol Rev 119(3):546–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028756

Lee LY-S, Lam KY-C, Lam MY (2020) Urban wellness: the space-out moment. J Tour Futures 6(3):247–250. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-10-2019-0111

Li H, Cao Y (2023) Facing the pandemic in the dark: Psychopathic personality traits and life history strategies during COVID-19 lockdown period in different areas of China. Curr Psychol 42(2):1299–1308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01549-2

Li Z, Gao Y (2024) Better wealth, better health: wellness hotel attributes and consumer preferences in China. J China Tour Res 20(2):333–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2023.2194698

Link BG, Susser ES, Factor-Litvak P et al. (2017) Disparities in self-rated health across generations and through the life course. Soc Sci Med 174:17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.035

Liu B, Kralj A, Moyle B et al. (2024) Perceived destination restorative qualities in wellness tourism: The role of ontological security and psychological resilience. J Travel Res 64(4):835–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875241230019

Liu B, Li Y, Kralj A et al. (2022) Inspiration and wellness tourism: The role of cognitive appraisal. J Travel Tour Mark 39(2):173–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2022.2061676

Malmberg L-E (2001) Future-orientation in educational and interpersonal contexts. In: Navigating Through Adolescence. Routledge, London, p 119–140

Moscardo G (2011) Searching for well-being: Exploring change in tourist motivation. Tour Recreat Res 36(1):15–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2011.11081656

National Bureau of Statistics (2023) Wage level of employed persons in urban units to maintain growth in 2022. https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/sjjd/202305/t20230509_1939288.html. Accessed 17 Apr 2024

Park J, Kim J, Kim S (2022) Evolutionary aspects of scarcity information with regard to travel options: The role of childhood socioeconomic status. J Travel Res 61(1):93–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520971040

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Richter NF, Schubring S, Hauff S et al. (2020) When predictors of outcomes are necessary: guidelines for the combined use of PLS-SEM and NCA. Ind Manag Data Syst 120(12):2243–2267. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-11-2019-0638

Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker J (2024) SmartPLS 4. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. https://www.smartpls.com. Accessed 09 Jan 2024

Sai X, Zhao Y, Geng Y et al. (2022) Revision of the Mini-K Scale in Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psychol 30(5):1160–1164

Sear R (2020) Do human ‘life history strategies’ exist? Evol Hum Behav 41(6):513–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.09.004

Sherman R, Figueredo A, Funder D (2013) The behavioral correlates of overall and distinctive life history strategy. J Pers Soc Psychol 105(5):873–888. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033772

Smith M, Kelly C (2006) Holistic tourism: Journeys of the self? Tour Recreat Res 31(1):15–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2006.11081243

Thompson DV, Hamilton RW, Banerji I (2020) The effect of childhood socioeconomic status on patience. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 157:85–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.01.004

TimeCamp (2024) Average Salary in China. https://www.timecamp.com/average-salary/china/. Accessed 11 Mar 2024

Travel China Guide (2023) Types of China Hotels. https://www.travelchinaguide.com/essential/hotel.htm. Accessed 11 Mar 2024

Wang L, Hou S (2017) The intrinsic mechanism of life history trade-offs: The mediating role of control striving. Acta Psychol Sin 49(6):783–793. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.00783

Wang X, Sun J, Wen H (2019) Tourism seasonality, online user rating and hotel price: A quantitative approach based on the hedonic price model. Int J Hosp Manag 79:140–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.01.007

Wang X, Leou CH (2015) A study of tourism motivation, perceived value and destination loyalty for Macao cultural and heritage tourists. Int J Mark Stud 7(6):83–91. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v7n6p83

Xia L, Lee TJ, Kim DK (2024) Relationships between motivation, service quality, tourist satisfaction, quality of life, and spa and wellness tourism. Int J Tour Res 26(1):e2624. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2624

Yao Y, Wang G, Ren L et al. (2023) Exploring tourist citizenship behavior in wellness tourism destinations: The role of recovery perception and psychological ownership. J Hosp Tour Manag 55:209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.03.008

Ye Z, Wen M, Wang W et al. (2020) Subjective family socio‐economic status, school social capital, and positive youth development among young adolescents in China: A multiple mediation model. Int J Psychol 55(2):173–181. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12583

Yu J, Lee K, Hyun SS (2021) Understanding the influence of the perceived risk of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) on the post-traumatic stress disorder and revisit intention of hotel guests. J Hosp Tour Manag 46:327–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.010

Zhang B, Mulhern FJ, Wu Y et al. (2022) Thirty years and “I’m still Lovin’it!”: brand perceptions of McDonald’s among generation Y and generation Z consumers in China. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 34(5):906–921. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-02-2021-0132

Zhang MX, Wu AM (2022) Effects of childhood adversity on smartphone addiction: The multiple mediation of life history strategies and smartphone use motivations. Comput Hum Behav 134:107298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107298

Zhong L, Sun S, Law R et al. (2023) Health tourism in China: a 40-year bibliometric analysis. Tour Rev 78(1):203–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2022-0112

Zhong L, Sun S, Law R et al. (2024) Tourists’ perception of health tourism before and after COVID‐19. Int J Tour Res 26(1):e2620. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2620

Zhou Y, Liu L, Han S et al. (2023) Comparative analysis of the behavioral intention of potential wellness tourists in China and South Korea. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:489. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01997-0

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by Macao Polytechnic University (RP/FCHS-05/2022) and (RP/FCHS-01/2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Junxian Shen: conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, software, writing - original draft. Hongfeng Zhang: methodology, validation, funding acquisition, supervision. Cora Un In Wong: conceptualization, writing - review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition, supervision. Jianhui Chen: investigation, resources, data curation. Lianping Ren: validation, writing - review and editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments, meeting the criteria for exemption from formal ethical review under China’s Measures for the Ethical Review of Life Science and Medical Research Involving Humans (National Health Commission, 2023; https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2023-02/28/content_5743658.htm) as it involved only anonymous questionnaire data collection without sensitive content or human experimentation. Following institutional research governance standards, the protocol received approval from the Research Committee of Macao Polytechnic University (RP/FCHS-01/2023/E01) on November 30, 2023. The study design ensured participant protection through comprehensive anonymization measures that minimized risks of physical or psychological harm, privacy breaches, or commercial conflicts.

Informed consent

This study employed the online survey platform for data collection. Before participation, all respondents received comprehensive information regarding the study’s objectives, their rights as research participants (including voluntary participation and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty), and the parameters of their informed consent. All participants acknowledged this information by selecting the consent option before gaining survey access. For Study 1, informed consent was obtained between November 30 and December 29, 2023. For Study 2, the informed consent process was conducted between November 29 and December 13, 2024. Rigorous confidentiality protocols were implemented throughout the study, including guarantees of complete anonymity, strict limitations on data usage for academic research purposes only, and explicit assurances that no participant information would be shared with third parties.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, J., Zhang, H., Wong, C.U.I. et al. Relationship between childhood socio-economic status and wellness tourism intention: a combined PLS-SEM and NCA methods. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 812 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05177-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05177-0