Abstract

Sustainable rural tourism (SRT) balances economic development, environmental management, and cultural preservation in rural areas, making it a hot topic. The research on SRT has evolved and covers a wide range of themes; however, comprehensive studies are limited. This paper conducts a bibliometric analysis of SRT research over the past 25 years (2000–2024) using literature in the Web of Science Core Collection and CiteSpace software for visualization, revealing the current state, evolving hotspots, and future trends in SRT research. The results indicate a significant increase in publication numbers in recent years, with notable collaboration between Asian and European institutions. Besides, SRT encompasses diverse topics with strong interdisciplinary connections; the authoritative research dynamics cover SRT resources, stakeholders’ participation, mechanisms and models, and specific SRT types. Furthermore, there is ongoing interest in the correlations between SRT and rural revitalization, tourist satisfaction, and ecosystem services. Additionally, this paper constructs a comprehensive knowledge framework suggesting that future research will further explore SRT resource utilization and interactions between stakeholders and SRT and enrich theories and methods while focusing more on “sustainable rural tourism.” These findings advance both the study and practice of SRT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rural tourism is a distinctive form of tourism in rural areas, attracting visitors seeking authentic experiences, nature, and culture. It revitalizes the rural economy, restores traditional villages, and promotes social development (Jin et al. 2021; Ion and Petre, 2024; Li et al. 2024a, 2024b, 2024c, 2024d). However, rapid growth in this sector presents sustainability challenges; it can strain local environmental protection efforts, harm ecosystems, and escalate conflicts between residents and tourists (Yang et al. 2024; Geng et al. 2024a). Thus, ensuring the sustainability of rural tourism is essential for balancing industrial development with social growth and ecological preservation (Yang et al. 2021). Sustainability has become a key topic in nature-society studies and is increasingly prioritized by global stakeholders. It plays a central role in rural tourism strategies aimed at harmonizing economic growth with environmental management and cultural conservation (Zang et al. 2020; Geng et al. 2021; Singhal, 2023; Dobre et al. 2024). Consequently, sustainable rural tourism (SRT) has become an irreversible trend crucial in research and practice.

In recent years, global stakeholders have increasingly focused on SRT to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. In particular, the United Nations unveiled the 2030 Global Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015, providing a framework for sustainable practices (Khizar et al. 2023). The UN’s Future Pact, introduced at the 2024 Future Summit, further advances sustainability initiatives within rural tourism (United Nations, 2024). In China, the Rural Revitalization Strategy was launched in 2017 to integrate rural tourism into this broader initiative effectively (Liu et al. 2020a, 2020b; Wang et al. 2022). South Africa has enhanced community participation and empowerment within SRT by advocating for locally adapted strategies that harmonize tourism growth with preserving rural cultural heritage (Phori et al. 2024). Meanwhile, Turkey is fostering its SRT through conserving and utilizing its architectural heritage (Kurnaz and Aniktar, 2024). These diverse approaches offer valuable case studies for research on SRT.

Existing research on SRT is thriving, delving into various dimensions such as sustainability, rural development, and tourism. Several studies highlight the importance of sustainability in SRT. Firstly, the research emphasizes the critical sustainable resources needed for SRT; rural tourism often faces challenges due to limited local resources; villages should utilize more local natural resources properly while preserving cultural heritage to promote SRT (Yang et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2024a, 2024b, 2024c). Secondly, some research identifies strategies for enhancing sustainability. Rural tourism can negatively impact the environment; thus, effective SRT policies from governments are essential; villagers should also adopt eco-friendly marketing strategies, and tourists are encouraged to engage in responsible behaviors that protect local ecosystems (Chen et al. 2022; Shen et al. 2022; Hueso-Kortekaas and Carrasco-Vaya, 2024). Furthermore, several studies explore the role of sustainability in SRT. Effective infrastructure, such as green buildings and clean energy solutions, is vital for fostering SRT that benefits both environmental health and villagers’ economic prosperity (Koliopoulos et al. 2021; Nistoreanu et al. 2024).

Some studies examine SRT from a rural perspective. Firstly, several studies emphasize the benefits villages can gain from SRT; by integrating local culture and traditions, SRT can promote socio-economic development in underdeveloped areas while revitalizing traditional villages (Dragan et al. 2024a, 2024b). Secondly, some research focuses on enhancing SRT pathways; improving rural characteristics through tourism facilities can support SRT (Zhang and Okamura, 2024). Furthermore, establishing local regulations is crucial for securing the long-term benefits of SRT (Jin et al. 2022). Additionally, other studies investigate interactions between rural residents and SRT; rural tourism can improve farmers’ livelihoods, support vulnerable groups’ interests, and enhance villagers’ overall well-being (Li et al. 2024a, 2024b, 2024c, 2024d; Wu et al. 2024a, 2024b).

Some studies adopt a tourism perspective to explore SRT. First, several studies examine tourists’ emotions and behaviors, emphasizing how intrinsic motivation, travel behavior, and experience perceptions influence their willingness to revisit and recommend destinations. That approach can enhance SRT (Baby and Kim, 2024). Second, some research investigates interactions between tourists and villagers. Differences in perceptions may lead to conflicts or foster mutual understanding; improving these two groups’ interactions can mitigate the homogenization of rural tourism and boost destination competitiveness (Wang et al. 2024a, 2024b). Additionally, some studies analyze how tourists contribute to SRT through online reviews, revealing landscape planning and resource management issues while suggesting strategies for SRT.

Some studies focus on the relationship between SRT and other factors. Firstly, some research highlights SRT’s relationship with climate change, highlighting that tourism destinations can make great efforts and be monitored to reduce their climate impact and to obtain better climate change mitigation performances (Streimikiene and Kyriakopoulos, 2024). Some studies examine the link between SRT and the environment, highlighting that SRT’s pressure on local environmental protection efforts and that environmental issues, policy plans, regulations, and measures contribute to better SRT development (Geng et al. 2020; Kyriakopoulos, 2021). Some studies examine the link between SRT and society, indicating that utilizing unique rural resources and geographical advantages for tourism can enhance resource efficiency and foster social development, thus aiding rural revitalization (Geng et al. 2023a).

Bibliometric methods use quantitative analysis, making research reviews more scientific and rigorous. With the emergence of various bibliometric software, this approach has become vital for analyzing large datasets in specific knowledge areas, revealing research evolution and identifying emerging directions (Zupic and Cater, 2015; Pessin et al. 2022). Recently, bibliometric analyses of rural tourism have emerged. While covering various topics, these studies usually focus on specific SRT forms. Some examine forms of sustainable rural tourism, such as mountain tourism, forest bathing tourism, and olive oil tourism (Shekhar, 2023; Pato, 2024; Pérez-Calderón et al. 2024); some review different stakeholders’ perspectives on SRT, including residents’ views, entrepreneurship spirits, and tourist satisfaction (Jiménez et al. 2022; Lulu et al. 2024; Zhou et al. 2024). Additionally, some studies review the relationship between rural tourism and other factors, such as sustainable development, marketing, and urban tourism (Li et al. 2024a, 2024b, 2024c, 2024d; Geng et al. 2024b; Geng et al. 2024c). While previous explorations of SRT have addressed various topics, they often concentrate on specific aspects, resulting in fewer comprehensive studies. Besides, relevant bibliometric analyses of rural tourism exist but are limited by the niche perspectives, insufficient focus on sustainability, and an inadequate data period (Su et al. 2022; Ndhlovu and Dube, 2024).

Given the complex evolution and rapid development of SRT research, there is an urgent need for a detailed and comprehensive summary of its progress and future research directions. In other words, the key research questions still to explore are:

-

(1)

How much attention has the SRT field received?

-

(2)

What is the state of collaborative research in this field?

-

(3)

What are the current research dynamics in this area?

-

(4)

What are the main research hotspots in this field?

This paper conducts a bibliometric analysis of SRT research from 2000 to 2024 to address the gaps in previous studies and resolve four identified issues. Using visualization software CiteSpace, we perform a multi-dimensional visual analysis covering statistical features, collaborative state, current research status, and trends in literature, journals, authors, regions, and institutions. We discuss the results comprehensively and integrate them into a knowledge framework that illustrates the macro-level structure of this study while predicting future research trends to help scholars understand key characteristics and potential directions more efficiently.

Materials and methods

Data

This paper used the Web of Science Core Collection (WOS) as our data source. We searched the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), and Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI) for relevant articles. Several datasets are available, including Scopus, Engineering Village, and Index to Scientific & Technical Proceedings. We selected WOS as our only data source for the following reasons:

-

(1)

WOS is a comprehensive knowledge base that rigorously selects academic journals globally, enhancing the understanding of SRT research. It features high-quality, authoritative journals to ensure data reliability (Liu et al. 2022; Dibbern et al. 2023).

-

(2)

WOS offers superior interdisciplinary indexing and a more refined subject classification system than databases like Scopus. This enhances multi-dimensional research analysis in the SRT field and fosters interdisciplinary studies. Compared to other databases, WOS offers broader subject coverage. For example, Engineering Village focuses primarily on engineering, while Index to Scientific & Technical Proceedings emphasizes science and technology; WOS covers various disciplines such as science, engineering, social sciences, and humanities.

-

(3)

Many WOS papers are also indexed in other databases. Some papers may be indexed by WOS and other databases (e.g., Scopus); we choose a single database to avoid data duplication.

-

(4)

The bibliometric software, CiteSpace, does not support cross-dataset analysis; therefore, if we have to choose between WOS and other databases, we prefer WOS for its greater authority and representativeness, which is supported in similar studies (Geng et al. 2024d).

The publication dates range from “January 1, 2000” to “August 21, 2024.” The document types are limited to “Article” and “Review,” with topics including “rural* NEAR tour*” OR “agri-tour*” OR “agri* NEAR tour*” OR “agro* NEAR tour*” OR “countryside NEAR tour*” OR “agritour*” OR “village* NEAR tour*” OR “county NEAR tour*” OR “counties NEAR tour*” AND “sustainab*” Only English articles are included.

We want to highlight why our study started in 2000; this year coincides with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) launch, which heightened global attention on sustainable development issues (such as sustainable rural tourism) and the Sustainable Development Goals (Hickmann et al. 2023; Greig and Turner, 2024).

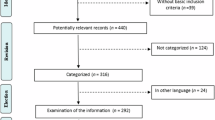

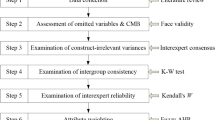

We manually review the data to filter out irrelevant literature and ensure data accuracy and relevance across diverse disciplines. We used a back-to-back screening method: two members evaluated titles, abstracts, keywords, and content; if their assessments differed, a third person made an independent judgment. Our initial dataset included 1,933 records. After the search and screening process, we identified 1,762 valid documents for analysis. The data were exported as a plain text file containing “complete records and cited references.”

Methods

Bibliometric analysis is an objective and quantitative statistical method. It examines research evolutions to understand knowledge structures in a field and explores the correlations and influence of authors, journals, institutions, and other objects (Chen et al. 2024a; Chen et al. 2024b).

CiteSpace effectively addresses limitations found in other bibliometric software, such as VOSviewer’s lack of clustering and temporal analysis, HistCite’s co-citation analysis restrictions, SATI’s absence of temporal characterization, and RefViz’s unsuitability for integrated analysis (Geng et al. 2023b). Its visual mapping presents analyses as node-link graphs, with nodes representing different elements. The size and color of the nodes indicate frequency and year, respectively, illustrating the research field’s development history. Links between nodes represent collaboration, co-occurrence, or co-citation, aiding researchers in identifying thematic clusters and understanding dynamic relationships within the field (Zheng et al. 2022; Zhao et al. 2023). Despite its powerful features, CiteSpace has limitations, including potential biases in keyword clustering. This study employs CiteSpace 6.3.R3 (64-bit) to visualize and analyze the collected literature; it also uses the Youdao Dict to translate and polish languages; authors have reviewed the contents as needed, and no new contents are generated by the language translation tool. Parameters are shown in Fig. A1.

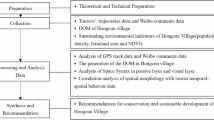

The research framework, shown in Fig. 1, comprises three main parts: WOS analysis, CiteSpace analysis, and theoretical summaries. The detailed steps are as follows:

WOS statistical analysis offers a solid data foundation for future research, boosting the credibility of findings and highlighting research popularity in the SRT field. The data and methods section outlines the WOS-sourced data and details the retrieval and filtering methods used to ensure accuracy. The statistical results from WOS assessed the attention paid to SRT research through annual publication counts and identified core journals and key disciplines via journal and subject category analysis.

CiteSpace analysis enables researchers to grasp a field’s current state and dynamic progress efficiently. It uses CiteSpace for data visualization, clearly illustrating collaboration networks, co-citation focuses, and themes’ evolutions. Specifically, collaboration analysis assesses cooperation among authors, institutions, and regions, highlighting the cooperation states; co-citation analysis examines co-citation networks of authors, journals, and literature to identify the knowledge base and focus status; co-occurrence analysis tracks the evolution of research hotspots through category co-occurrence, keyword co-occurrence, and keyword bursts.

Theoretical summaries enable researchers to understand key points and offer guidance for future research quickly. This step establishes a theoretical framework based on prior analyses, summarizes tourism destination cases in SRT, and outlines future SRT research directions. It also emphasizes the study’s new findings and novelty by comparing its results with previous relevant studies.

Results

Publication statistics

Statistical data on publications indicates the popularity of the field and scholars’ research interests, helping researchers identify key journals and relevant disciplines (Wang et al. 2023). This section examines how much attention SRT research has received.

Annual publication number analysis

Figure 2 shows the annual number of publications on SRT from 2000 to 2024, revealing a general increase divided into three stages. Stage 1: From 2000 to 2013, publication numbers were low, not exceeding 50 annually, indicating limited academic interest in this field. That was due to weak research foundations, a lack of systematic theoretical frameworks, and efficient data-processing software. Despite the scarcity of literature, several key models and frameworks were applied to SRT during this period. For example, a highly cited 2003 paper (125 citations) analyzed rural tourism trends using a lifecycle model (Hovinen, 2002). Another notable 2004 paper (181 citations) employed value-focused thinking and the A’WOT hybrid method for strategic planning in rural tourism (Kajanus et al. 2004). These studies lay the foundation for future research, providing a comprehensive perspective on the development of SRT since its early stages. Stage 2: Between 2014 and 2019, there was steady but slow growth in papers, reflecting an increasing scholarly focus on SRT as a key driver for rural development. Since 2014, publications on SRT have surged due to several factors. First, the United Nations’ adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 raised global awareness of sustainable development, leading academia to recognize SRT as vital for achieving these goals (Gupta and Vegelin, 2016). Second, rural tourism is acknowledged as a practical approach for promoting sustainable rural development, poverty alleviation, and environmental protection (Wang et al. 2013), leading to increasing attention. Third, many mega and open-access journals have emerged at a scientific level, providing abundant platforms to publish SRT research. Stage 3: A significant surge began in 2020, peaking in 2022, with a slight decline expected for 2023–2024. Recently, scholars have emphasized sustainable practices for long-term success in SRT; particularly driven by rural revitalization strategies, the integration of agriculture and tourism has significantly influenced economic, social, and ecological dimensions, fostering synergistic growth between SRT and sustainability efforts (Ma et al. 2024a, 2024b). Note that data for 2024 only includes figures up to August; hence, the lower count. Overall, SRT has gained increasing academic attention over the past quarter-century. SRT offers opportunities for social and economic advancement while minimizing negative environmental impacts; thus, it presents substantial research potential (Ndhlovu and Dube, 2024).

The dotted line in the graph illustrates the trend from 2000 to 2023, based on data collected until August 21, 2024. The trend line formula is y = 0.8079x²–10.898x + 37.244; R² = 0.937, where x represents the year and y denotes the number of publications. R² indicates how well the trend line fits; values closer to 1 signify better reliability. This trend supports our prediction of a steady and accelerating increase in publications in this field, attracting more scholarly attention.

The above conclusions imply that external factors, such as the rise in mega journal publications, the Sustainable Development Goals, and the promotion of rural revitalization, influence the rapid growth of SRT research. Along with the emergence of more incentives, scholars can confidently dedicate more effort to SRT and anticipate increased research outputs to accelerate SRT practice.

Annual publication journal analysis

Annual publications in journals assist researchers in identifying influential journals and clarifying the research scope. A journal’s academic impact is typically associated with its higher impact factor (IF). Additionally, more published articles enhance its contribution to the field (Shao et al. 2021).

The WOS database indicates that over the past 25 years, 367 journals have published 1762 articles on SRT. Table 1 lists the top 10 journals by article count in this field, highlighting their influence and relevance.

-

(1)

Thematically, three of the top four journals include “sustainable” in their titles, emphasizing sustainability’s importance for rural tourism. Other relevant topics include tourism, environmental ecology, agriculture, and natural resource management, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of SRT research.

-

(2)

“Sustainability” alone contributes to 24.404% (430 articles), underscoring its significant role in SRT research. Besides, the top ten journals account for 45.175% of all articles in this area, highlighting their significance and popularity in SRT research.

-

(3)

Regarding impact factors, the “Journal of Sustainable Tourism,” closely linked to SRT research, has the highest score at 9.5, indicating substantial academic influence. Additionally, “Land Use Policy,” “Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research,” “Agriculture,” and “Current Issues in Tourism” have high impact factors: 6.5, 4.4, 3.5, and 6.7, respectively, showcasing their influence in SRT.

-

(4)

From the quartile perspective, nine out of ten journals are classified as Quartile 2 or higher; this suggests that SRT is a prominent topic within academia, with many impactful studies produced at a high academic level.

The above analysis aids future researchers in selecting appropriate journals for their work. Besides, the above results imply that SRT research can focus on both “sustainability” and “tourism,” and authors need to improve the quality of their research to successfully publish SRT research papers (after all, most journals that publish SRT research have relatively high quartiles).

Annual publication category analysis

Analyzing publication categories helps researchers understand the field’s focus and conduct effective research (Geng et al. 2024e). Table 2 lists the top 10 categories with the most publications on SRT, showcasing a diverse range of areas covered.

-

(1)

The most significant number of articles relates to the environment, underscoring its importance in this field. The “Environmental Sciences” category published 763 articles (43.303%), while “Environmental Studies” contributed 612 articles (34.733%), highlighting a strong connection between SRT and environmental development.

-

(2)

“Green Sustainable Science Technology” is also significant, with 630 articles published (35.755%), indicating that green technology plays a crucial role in SRT.

-

(3)

Additionally, SRT intersects with “Hospitality Leisure Sport Tourism” (353 articles, 20.034%), “Management” (91 articles, 5.165%), “Geography” (68 articles, 3.859%), and Ecology (65 articles, 3.689%).

Various disciplines influence policy formulation and tourism practices through their outcomes. For instance, research in the “Environmental Sciences” category has provided data support for SRT; it uses spatial data to identify tourism areas that harmonize natural and cultural landscapes, balancing ecological development and protection. That aids policymakers in formulating SRT policies and ensures stakeholder support for SRT development (Guerbuez and Batman, 2025). Besides, research in the “Green Sustainable Science Technology” category provided practical support for SRT; Kazakhstan’s Aksu-Zhabagly has developed large-scale clean energy infrastructure and ensured access to clean resources, which created favorable conditions for local SRT (Abbas et al. 2025).

In summary, these findings imply the comprehensive and interdisciplinary nature of SRT. Scholars can conduct SRT research from a multidisciplinary perspective using different methods; policymakers can use concepts and methods from various disciplines to investigate and formulate policies that meet the needs of different industries.

Collaboration analysis

Collaboration analysis answers research question 2, helping researchers understand relationships among authors, institutions, and regions in their field and the focus of collaborative research. It also identifies potential collaboration opportunities. Visualized networks provide an intuitive view of group connections, collaboration scope, and current topics (Gao et al. 2024a).

Author collaboration

Table 3 lists the top 15 authors with the highest collaboration counts, highlighting their collaboration influences in the field (Geng et al. 2024c). Only the top three authors had over ten collaborations with zero centrality, indicating limited collaboration and relatively independent research. This aligns with previous “urban tourism” research, in which author collaboration centralities are zero, likely due to individual research interests and resources limiting broader author collaborations (Geng et al. 2024c). We hereby want to highlight the centrality, which reflects an author’s academic influence. A centrality above 0.1 indicates that the node is essential and plays a vital role in connecting other nodes; zero centrality signifies low connectivity within the network. For example, authors with zero centrality in the collaboration network demonstrate low collaboration intensity in connecting different authors, indicating relatively independent or isolated research teams compared to those involving various researchers (Li et al. 2022; Geng et al. 2024a). Besides, author collaborations have surged in the past five years; 11 out of 15 authors initiated their first collaboration after 2019, reflecting enhanced collaborative enthusiasm alongside increased publications. The specific findings are as follows:

-

(1)

The most active collaborator is Gualter Couto (11 counts), who published 51 articles on SRT over the last five years. His work focuses on effective SRT strategies that improve communication infrastructure, land resource management, and cultural tourism (Castanho et al. 2023; Couto et al. 2023; Sousa et al. 2023). This author’s two recent collaboration papers analyze how inter-island transportation affects SRT, concluding that maritime and air transport can enhance social mobility and boost SRT (Castanho et al. 2024; Luis et al. 2024).

-

(2)

Authors Iancu Tiberiu (10 counts), Tabita Adamov (10 counts), and Ramona Ciolac (8 counts) rank second to fourth. Their latest co-authored paper discusses SRT strategies for mountainous communities while advocating innovative approaches to leverage local high-value resources (Popescu et al. 2024).

-

(3)

Fifth place goes to Rui Alexandre Castanho, who has participated in eight collaborations, six with Gualter Couto. This underscores Couto’s significant influence and indicates a stable network among leading authors.

The above findings imply that authors may collaborate on various topics. These insights can help researchers find suitable collaborators; we encourage more academic exchanges and frequent collaborations since current interactions in this field remain insufficient.

Figure 3 illustrates the author collaboration network, comprising 659 nodes and 469 links, with a density of 0.0022. Density indicates the closeness of connections among nodes in a network. Lower density means fewer links, suggesting more dispersed cooperation and less frequent or stable connections (Chen and Zhao, 2024). Distinct collaborative clusters were identified, where scholars primarily interacted within them. The ten prominent clusters can be categorized into five main research directions:

-

(1)

Some clusters examine the relationship between the environment and SRT, such as #2 (rural environments sustainability, focusing on SRT’s impacts in rural areas) and #3 (sustainable forest management, emphasizing policies for sustainable tourism). In cluster 2, co-authors Iancu Tiberiu and Adamov Tabita suggest that rural tourism enhances environmental sustainability (Adamov et al. 2020; Ciolac et al. 2020). Cluster 3’s key author, Lim Ho Sub, advocates prioritizing forest management to develop practical models for sustainably operating forest attractions (Kang et al. 2007).

-

(2)

Other clusters explore the connection between culture and SRT, including #1 (sustainable creative tourism, promoting new rural tourism models blending culture with natural heritage) and #9 (culture, highlighting how cultural resources enhance tourist site sustainability). Key collaborator Cuoto Gualter in cluster #1 indicates that creative tourism boosts local vitality and destination resilience (Baixinho et al. 2023).

-

(3)

Some clusters focus on the link between urbanization and SRT, such as #5 (urbanization) and #6 (planned sustainable urban development project). Cluster #5 features collaborator Su Ming Ming advocating for integrating tourism with agricultural heritage during rapid urbanization to support rural community livelihoods (Su et al. 2020). Research in cluster #6 emphasizes incorporating SRT into urban planning (Aldossary et al. 2023).

-

(4)

Some clusters focus on specific case studies of SRT, such as #4 (Yunnan, China) and #8 (snow-covered areas). For instance, Boudhar, A., a co-author from cluster #8, showed that sustainable management of natural resources can enhance rural tourism benefits in snowy regions (Boudhar et al. 2010).

-

(5)

Other clusters examine behavioral models of SRT, including #0 (modeling sustainability) and #7 (community citizenship behavior). Cluster #0’s collaborative study integrates sustainability into its analytical model and highlights the need for research frameworks that fully consider sustainability dimensions in SRT analysis. It finds that tourism can provide a viable economic foundation for sustainable development in rural communities (Kruse et al. 2004). The representative authors of cluster #7 analyzed how community citizenship behavior for the environment impacts the sustainable development of rural tourism communities (Wu et al. 2023).

The analysis implies that researchers engaged in collaborative SRT studies address diverse social, economic, cultural, and ecological topics. Their collaborative research may focus on modeling and factor correlations, which is important for promoting SRT research. To foster broader cooperation and advance this field collectively, we recommend strengthening interactions among authors.

Institutional collaboration

The top 15 most collaborative institutions are listed in Table 4, primarily from Asia (10/15) and Europe (4/15), with one from Oceania. That indicates strong institutional cooperation regarding SRT research in these continents. The detailed findings are as follows:

-

(1)

All 10 Asian institutions are from China, highlighting significant collaboration interest in SRT among Chinese institutions. The Chinese Academy of Sciences leads Chinese institutions’ collaboration with 65 collaborations, mainly with the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences. They focus on sustainable rural heritage tourism, finding that tourism can provide alternative livelihoods for residents at heritage sites and generate positive economic impacts (Su et al. 2018). They also propose strategies for developing agricultural heritages within tourism contexts to enhance protection and sustainability (Yang et al. 2018).

-

(2)

European institutions are also active in this field. For example, Universidad de Extremadura in Spain (26 counts) collaborates to explore rural residents’ and tourists’ attitudes towards local SRT and tourist loyalty (Campón-Cerro et al. 2017a; Campón-Cerro et al. 2017b).

-

(3)

Griffith University in Australia is the only institution from Oceania on the list, having collaborated 16 times, mainly with Edith Cowan University and Bond University, to tackle rural tourism challenges and explore solutions for achieving SRT (Saufi et al. 2014; Lasso and Dahles, 2018).

-

(4)

The University of Chinese Academy of Sciences and Griffith University have the highest centrality (0.05) in institutional cooperation, indicating their significant influence. Although the Chinese Academy of Sciences began collaborating earliest (in 2009), it shows lower centrality than others, suggesting a need for a more significant impact despite ongoing research efforts.

In summary, institutions prioritize different collaborative research directions; higher collaboration may lead to lower centrality. Therefore, while promoting cooperation, institutions should enhance the quality and impact of their research to strengthen academic partnerships and achieve better outcomes.

The visualization of institutional collaboration clusters in Fig. 4 shows 514 nodes and 397 links. The 11 clusters can be categorized into six groups:

-

(1)

The first category discusses the case of SRT, specifically cluster #0 (case study) and cluster #9 (case studies). In cluster #0, key collaborators are the Chinese Academy of Sciences (65 times) and the Institute of Geographic Sciences & Natural Resources Research (37 times), whose joint papers on Guizhou (China) explore interactions among tourism, community economy, environment, and cultural sustainability (Li et al. 2016; Song et al. 2022). Cluster #9 features the University of Bari Aldo Moro (5 times) and the University of Salento (5 times), which analyze rural resilience and SRT paths by comparing towns in the “Monti Dauni” sub-region to highlight innovative approaches for leveraging environmental and cultural heritage for economic viability (Ivona et al. 2021).

-

(2)

The second category is represented by cluster #1 (social capital). Key institutions defined as resources gained through social relationships—including trust, belonging, and participation—include Griffith University (16 times) and Universidad de Extremadura (26 times). They focus on developing social capital within community tourism and its impact on community belonging (Zhang et al. 2021). Additionally, a collaboration between the University of Central Florida and the University of Greenwich indicates that factors like interpersonal trust positively influence visitors’ intentions to sort waste at rural tourism destinations (Cao et al. 2022).

-

(3)

The third category focuses on SRT’s natural planning and management. Cluster #2 (landscape planning) emphasizes the importance of landscape management for SRT in specific areas. Cluster #7 (coastal aquifer) addresses SRT’s water resource pressure, climate change, and environmental damage. Cluster #8 (sustainable management) highlights the rational use of natural resources. Cluster #2 includes Nanjing University and Sun Yat-Sen University, which collaborate on research demonstrating that landscape is vital for SRT and analyze integrated landscape planning that combines natural and cultural elements (Li et al. 2021). Cluster #7 features the Complutense University of Madrid and Autonoma University of Madrid, working together to manage coastal water resources to meet SRT demands (Koussis et al. 2010). In cluster #8, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha and Universitat de Girona conduct joint research on the overuse of natural resources in tourism, proposing practical measures for resource utilization and management strategies to foster SRT (Peñuelas et al. 2021).

-

(4)

Cluster #5 (sustainable development) examines tourism’s role in rural sustainable development. Led by Tongji University, this collaboration investigates how tourists and tour operators foster economic growth and sustainability in rural mountain areas through social media (Hussain et al. 2019). Zhejiang University focuses on SRT in developing economies, emphasizing that public interventions and consistent policies can boost rural tourism’s competitiveness and sustainability (Khan et al. 2020).

-

(5)

Some clusters assess the status and challenges of SRT at key heritage sites, including cluster #3 (Sanqingshan World Heritage Site, China) and cluster #4 (Spanish Central Pyrenees). Research from Renmin University of China and China University of Geosciences in cluster #3 shows that rural tourism may disrupt livelihoods, social structures, and cultural traditions. They recommend improving livelihood sustainability in rural heritage tourism areas (Su et al. 2016). In cluster #4, Instituto Pirenaico de Ecologia (IPE) studies livestock cooperative networks within various tourism systems. Their findings indicate that economic trends have affected cooperative networks and suggest strengthening collaboration among livestock farmers within tourism systems (Saiz et al. 2017). Based on this research, we advocate for tailored management systems that consider each region’s unique natural, economic, and cultural contexts to promote SRT.

-

(6)

Some clusters explore the connections between SRT and its stakeholders, such as #6 (local knowledge holder, focusing on how SRT fosters interdisciplinary collaboration among knowledge holders) and #10 (small enterprise participation, highlighting how such participation in SRT diversifies income). Research from institutions in cluster #6, including Environment & Climate Change Canada, indicates that studying village sustainability strengthens ties between scientists and communities, which is conducive to SRT (Kruse et al. 2004). In cluster #10, Nanjing Forestry University and Griffith University found that value co-creation among operators, tourists, and government is essential for revitalizing rural homestays and promoting SRT (Li et al. 2024a, 2024b, 2024c, 2024d).

In summary, collaboration among institutions in SRT varies by theme, focusing on ecological management at tourist destinations, economic benefits, and stakeholders. Different topics are interconnected through institutional cooperation to influence SRT research, policy development, and practice. Connections within clusters are stable and frequent, and we recommend enhancing cooperation on similar issues while broadening the research scope through multidisciplinary partnerships.

Region collaboration

Table 5 lists the top 15 most active regions in collaboration, with primarily developed areas (10/15) due to their technology, economy, education, and policy advantages that foster SRT (Radovic et al. 2020).

-

(1)

Specifically, Europe (7/15) and Asia (5/15) lead in cooperation, with 612 collaborations (37.09%) for Europe and 733 collaborations (44.42%) for Asia. North America contributes two regions while Oceania adds one, indicating global interest in this research topic. The absence of African representation highlights a need for increased focus and collaboration in this field.

-

(2)

Regarding quantity and centrality of collaborations, China leads with 524 partnerships but has a low centrality score of 0.07, suggesting frequent cooperation yet potential for improved quality and impact. The United States (172 counts, 0.11), Spain (160 counts, 0.07), Italy (126 counts, 0.11), and Australia (91 counts, 0.17) also rank among the top five but exhibit relatively low centrality scores below 0.2. Conversely, the United Kingdom (87 counts, 0.28), Germany (54 counts, 0.39), Iran (46 counts, 0.27), and Poland (45 counts, 0.27) show lower collaboration numbers but higher centrality scores above 0.2, proving that despite low publication volume, they have effective collaborative leadership in connecting other partners, and notable impacts—indicating stronger academic ability and connection status (Geng et al. 2024e). In addition, it is noteworthy that most regions began their collaborations before 2010 (14/15), reflecting an ongoing commitment to SRT research across various fields during earlier years.

The above findings imply that collaboration frequency is not necessarily positively correlated with impact. Therefore, policymakers should formulate research policies that encourage both the frequency and the impact of collaboration and consider both quantity and quality when assessing collaborative research performance. Besides, to improve cooperation effectiveness, we recommend that regions with weaker collaborative influence enhance communication with those with higher centrality, like Germany and the UK.

The regional cooperation visualization cluster, illustrated in Fig. 5, includes 113 nodes and 148 links. Collaboration among regional clusters is broader and more frequent than that of authors and institutions, with all the top 10 representative clusters involved in external partnerships. These clusters can be further explored in four directions:

-

(1)

Some clusters examine the impact of SRT on rural communities. For instance, cluster #0 (community development) explores how SRT influences community growth; cluster #6 (rural area) focuses on local resource-based tourism development and its sustainability implications; while cluster #9 (small-scale agriculture) evaluates the contributions of SRT and small-scale farming to regional progress. Specifically, cluster #0’s representative node discusses integrating tourism into rural communities, indicating that residents gain better job opportunities by connecting with external tourism stakeholders. The study recommends enhancing ties between villagers and travel agencies to foster SRT and rural development (Dinh et al. 2023). In cluster #6, the representative region, China, assesses rural tourism sites’ social values, arguing that social values like esthetic and recreational benefits can support SRT, aiding ecological protection and rural development (Duan and Xu, 2022). In Cluster #9, the representative region, Brazil, highlights that strengthening links between tourism and small-scale agriculture fosters local sustainable development (Sanches-Pereira et al. 2017).

-

(2)

Some clusters examine the impacts of natural resources on SRT, particularly cluster #1 (groundwater resource) and cluster #7 (transboundary approaches). Cluster #1 emphasizes sustainable water management in SRT, exemplified by Turkey’s analysis of water issues, which addresses shortages due to agriculture and tourism activities (Harmancioglu et al. 2008). In contrast, representatives in cluster #7 focus on alleviating natural resource scarcity and promoting SRT through transboundary approaches that consider pressures from tourism (Scott et al. 2003). Recent studies from the representative region, India, highlight the importance of sustainable water management for coastal communities; findings indicate that integrated water resource management can improve freshwater availability while supporting SRT, thus reducing costs associated with water management (Abd-Elaty et al. 2022).

-

(3)

Some clusters focus on “sustainable development” in SRT. For example, cluster #2 (sustainable ecotourism development) assesses the sustainability feasibility of rural ecotourism; cluster #3 (sustainable tourism development) examines sustainable factors driving SRT growth; and cluster #4 (regional sustainable development) highlights creative tourism’s role in regional sustainability. In cluster #2, Iran tackles environmental issues from tourism, industry, and agriculture growth and promotes a comprehensive ecological restoration and balance plan (Pourebrahim et al. 2023). Cluster #3 features Russia’s evaluation of rural tourism as a key activity that enhances rural sustainability by utilizing natural and cultural resources (Curcic et al. 2021). In cluster #4, Portugal investigates how creative tourism supports sustainable island development, showing that rural creative tourism can promote local sustainability (Couto et al. 2023).

-

(4)

The fourth cluster examines specific rural tourism destinations, such as cluster #5 (Inner Mongolia) and cluster #8 (Okavango Delta, Botswana), focusing on how destination-specific characteristics affect SRT. Representing cluster #5, Spain analyzes Inner Mongolia from a tourist’s viewpoint and finds that local rural culture and nature significantly enhance visitor engagement (Han et al. 2021). Cluster #8’s representative node, Botswana, investigates the socio-economic effects of enclave tourism in the Okavango Delta. It suggests cultural tourism can diversify rural livelihoods in developing countries while promoting policies to sustain tourism revenue and address livelihood challenges (Mbaiwa and Sakuze, 2009).

The above findings imply that SRT research emphasizes diverse collaboration themes shaped by natural, social, and cultural factors. Researchers should consider geographical aspects when choosing partners and select regions that align with their research themes for collaboration.

Co-citation analysis

Co-citation analysis identifies influential authors, journals, and literature in the field, their interrelationships, and current research focuses (Geng et al. 2024b). This section aims to address the current dynamics of research in this field.

Author co-citation

Table 6 lists the top 10 authors with over 100 co-citations, highlighting their significant contributions to the field (Gao et al. 2024b). Specifically:

-

(1)

The most co-cited authors are Sharpley R (236 times), Hall CM (187 times), and Lane B (179 times). Sharpley R focuses on SRT consumption (Schweinsberg and Sharpley, 2024); Hall CM demonstrates that strategic planning aligned with local characteristics enhances rural ecotourism sustainability (Torabi et al. 2024); Lane B addresses spatial inequality in rural tourism, noting that affluent areas receive more attention than underdeveloped regions, which leads to unsustainability (Jin et al. 2024).

-

(2)

The top five authors were co-cited relatively early (all before 2010), underscoring their leading roles in this field. However, analysis of author collaboration and co-citation networks shows minimal overlap among the top ten authors, suggesting that high collaborative publication volumes do not guarantee high co-citation rates. Only Su MM ranks in the top 10 for both lists, emphasizing this author’s role in fostering cooperation while gaining recognition. It is also found that despite high co-citation counts, all top ten co-cited authors have a centrality score of 0, indicating limited influence in SRT.

The above findings imply that in SRT research, “the early bird catches the worm.” Those who start their research earlier are more likely to be identified and recognized by their peers (high number of co-citations), although they may tend to work alone or in small groups. Besides, the impact of these co-cited authors is still limited. Therefore, we suggest that the authors enhance their influence and authority in SRT research.

The author’s co-citation network in Fig. 6 includes 1001 nodes and 3033 links, revealing 10 key clusters. Key findings include:

-

(1)

Some clusters focus on specific tourism destinations: cluster #0 (upper reaches), cluster #5 (southwest Portugal), cluster #6 (Cornwall, South West England), and cluster #7 (Okavango Delta, Botswana). Research from cluster #0 indicates that SRT presents opportunities and challenges for villagers in upstream river areas. Co-cited author Su MM notes that rural tourism can enhance local economies, though weak rural tourism performances limit benefit distribution (Su et al. 2018). Cluster #5 highlights southwestern Portugal’s potential to leverage local resources for SRT. Co-cited authors Park DB and Kastenholz E emphasize that enhancing visitors’ social and emotional experiences can boost satisfaction and promote SRT (Carvalho et al. 2021). Cluster #6 explores the link between SRT and local socio-culture in England. Co-cited author Hall CM underscores the importance of rural food tourism for sustainable landscapes and regenerative agriculture practices (Pearson et al. 2024). Cluster #7 examines the relationship between agriculture and SRT using Botswana as a case study. The representative co-cited institution, the European Commission, points out that local multi-functional agriculture overlooks connections to rural tourism, suggesting policies to make multi-functional agriculture a valuable tool to enhance SRT (Knickel et al. 2009).

-

(2)

Some clusters focus on specific factors and their effects, such as cluster #9 (success factor), which analyzes factors for SRT success, and cluster #1 (mediating role), examining the mediating role of elements in the SRT process. In cluster #9, co-cited author Getz D emphasizes that tourism is a vital factor for sustainable rural development by creating stable jobs and generating profits; these successes are determined by the factor that SRT activities are stable and prosperous throughout the year (Martínez et al. 2019). Additionally, the representative author in cluster #1, Lee TH, notes that community participation and attachment are moderating factors influencing SRT (Lee, 2013).

-

(3)

Some clusters address rural development: cluster #2 (farm diversification) and cluster #8 (sustainable rural development). Cluster #2 highlights agricultural diversification’s role in enhancing SRT; co-cited author Sharpley R argues that diverse agriculture supports traditional villages’ sustainable development through tourism (Li et al. 2024a, 2024b, 2024c, 2024d). Meanwhile, cluster #8 explores how rural tourism can promote sustainable rural development; co-cited author Lew AA stresses the need to integrate tourists, businesses, governments, and destinations to enhance sustainability (Zhang et al. 2024a, 2024b, 2024c).

-

(4)

Some clusters focus on the evolving dynamics of SRT, particularly cluster #3 (formation mechanism) and cluster #4 (business outcome). Cluster #3 examines SRT’s spatial patterns and formation mechanisms, suggesting that optimizing village structures and rural tourism can promote sustainable development. Co-cited author Liu YS highlights significant differences in rural settlement distribution during urbanization, arguing that enhancing rural tourism and restructuring village layouts support sustainability (Yang et al. 2015). Cluster #4 discusses the business benefits of SRT activities. Co-cited author Bramwell B emphasizes that assessing rural tourism products’ commercial viability and sustainability clarifies their advantages, aiding strategies to improve visitor access and increase revenue (Ma et al. 2024a, 2024b).

In summary, the author co-citation analysis reveals diverse research interests among authoritative authors in SRT research, such as tourism destinations, factor correlations, rural development, and evolving dynamics. These findings imply that researchers and practitioners can focus on SRT development mechanisms from different perspectives, based on specific cases, and develop locally adapted industry standards and policies.

Journal Co-citation

Table 7 lists the top 10 journals with the highest co-citation counts. Tourism journals lead the field, with six of the top 10 being tourism-related, showing that most authoritative SRT articles are published in these journals. This result is similar to previous studies; a bibliometric analysis of “sustainable tourism” demonstrates that authoritative journals are tourism-related (Journal of Sustainable Tourism, Annals of Tourism Research, and Tourism Management) (Geng et al. 2024a). The finding highlights that authoritative SRT research tends to focus more on T (tourism). Details are as follows:

-

(1)

The top 10 co-cited journals exhibit high co-citation counts and impact factors, reflecting their quality. Notably, “Tourism Management” (1047 co-citations, Quartile 1, impact factor 11.5, centrality 0.05) and “Annals of Tourism Research” (888 citations, Quartile 1, impact factor 11.2, centrality 0.13) have the highest co-citation counts, impact factors, and centrality, underscoring their academic prestige and foundational status in connecting various journals. “Journal of Sustainable Tourism” (908 co-citations, centrality 0.02) and “Sustainability” (805 co-citations, centrality 0.01) also have high co-citation counts but low centralities. Additionally, “Sustainability” has a lower impact factor of only 3.6 in Q2, indicating its relatively lower recognition in SRT research.

-

(2)

Co-citation times span from 2000 to 2016; The earliest co-citation of “Annals of Tourism Research” in 2000 emphasizes its early focus on this research area. Its latest article discusses income distribution in poverty alleviation tourism, showing that community-led approaches can enhance visitor numbers compared to government or enterprise-led methods (Pang et al. 2024). Other earlier influential journals include “Tourism Management” (2002) and “Journal of Sustainable Tourism” (2004), all receiving first co-citations by 2005, indicating sustained interest in this field. Additionally, two journals began focusing on this topic post-2015: “Sustainability” (2016) and “Tourism Management Perspectives” (2015), likely due to their later founding dates (2009 and 2012).

The above findings imply that authoritative journals usually have a clear advantage regarding the number of co-citations and impact factors from an earlier period. Therefore, journal editors are recommended to promote their journals through international conferences and advertisements to attract more readers’ attention and increase their impact. Researchers, on the other hand, should explore articles from these co-cited journals and expand their knowledge base to gain insights into the field.

Figure 7 shows a visual cluster of journal co-citations featuring 1036 nodes and 3479 links. In summary, SRT research in highly co-cited journals can be divided into three themes:

-

(1)

Some clusters address SRT-related resource issues, including natural, demographic, policy, and economic resources. Notable examples are cluster #0 (environmental conservation), cluster #2 (sustainable rural development), cluster #3 (groundwater resource), cluster #5 (nature-based adventure tourism), and cluster #6 (Italian agritourism). Research in cluster #0 examines SRT benefits from ecological protection (Bohnett and An, 2023); the representative co-cited journal “Ecological Economics” defines the “ecosystem service units” based on economic principles to measure nature’s contributions to local communities (Díaz et al. 2018). Its citing literature analyzes land use changes in Hungarian rural tourism sites, indicating that increased forest area has protected the ecosystem while promoting SRT (Almeida-Gomes et al. 2022). In cluster #2, a co-cited study in “Tourism Management” found that rural community tourism sustainability varies in different stages, proposing policies as resources to enhance SRT and recommending policymakers and managers adopt appropriate policies and strategies for each stage (Lee and Jan, 2019). Cluster #3 investigates water resource sustainability and its management effects on tourism. A co-cited article from “Science of the Total Environment” notes that excessive groundwater extraction leads to various challenges, advocating for a shift in water usage to support SRT (Custodio et al. 2016). Cluster #5 explores the significance of natural resources in SRT. Research from the representative co-cited journal Agriculture and Human Values proposes that rural and natural resources are diversified and valuable, and it is essential to incorporate their multiple values into decision-making to achieve sustainable changes (Fuente-Cid et al. 2024). The citing research in this cluster proposes that nature adventure tourism can be introduced in rural areas, which deepens villagers’ understanding and support for SRT (Tirasattayapitak et al. 2015). Cluster #6 explores how SRT influences local population resources. The co-cited journal “European Countryside” studied the decline of the European population and found that SRT helps mitigate local population loss (Viñas, 2019).

-

(2)

Some clusters that focus on SRT theory and mechanisms include cluster #1 (mediating role, focusing on factors influencing sustainable tourism), cluster #4 (traditional village, examining traditional villages’ transformation mechanism in SRT), and cluster #9 (tourism development). Cluster #1 involves residents, tourists, communities, businesses, and the environment. The co-cited journal “Journal of Travel Research” highlights that residents’ perceptions significantly mediate the relationships among community attachment, environmental attitudes, and SRT’s economic benefits (Gannon et al. 2021). Cluster #4 focuses on optimization strategies for traditional villages to enhance rural tourism sustainability and commercial value. For instance, a recent article in “Land Use Policy” discusses how rural homestay decreases villagers’ living spaces while advocating rational rural homestay planning, transformation, and sustainable governance to enhance SRT (Bi and Yang, 2023). Cluster #9 examines how economic conditions, social relationships, land use, and other factors influence SRT. The co-cited journal “Sustainability” presents a model based on SRT, showing that effective land resource utilization fosters sustainable growth in tourism-oriented villages (Gao et al. 2019).

-

(3)

Some clusters focus on SRT types, including cluster #7 (sustainable nature tourism) and cluster #8 (sustainable creative tourism). Cluster #7 explores the potential and challenges of sustainable nature tourism. A co-cited article in “Environment” highlights that well-managed nature reserves can protect biodiversity while providing ecosystem services like tourism (Canney, 2021). Cluster #8 emphasizes that sustainable creative tourism stimulates the village economy, enhancing competitiveness. The co-cited journal “Tourism Review International” discusses developing textile-related cultural tourism in impoverished European regions, stressing the need for products showcasing local cultural uniqueness to attract tourists (Richards, 2005).

The findings imply that authoritative journals emphasize different aspects of SRT research. Some focus on theoretical frameworks and policies, while others address the practical challenges of SRT. These conclusions will significantly influence future research, policy development, and practice. For instance, some journals examine the mediating mechanisms between factors, encouraging researchers to develop new theoretical models for SRT and clarify the roles of various elements; others investigate rural transformation mechanisms, inspiring scholars to explore viable paths for rural tourism to facilitate this transformation. On the other hand, other journals concentrate on resource issues in SRT practice, prompting practitioners to consider efficient resource use in rural tourism to minimize waste and environmental impact; meanwhile, some journals focus on specific practical types of SRT, guiding practitioners to use local resources and create distinctive tourism products with precise market positioning for sustainable rural tourism development.

Reference co-citation

Table 8 lists the top 11 most frequently co-cited references, mainly from tourism journals like “Tourism Management,” “Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management,” and “Journal of Sustainable Tourism,” highlighting their likelihood to publish authoritative papers in the field. Some detailed findings:

-

(1)

Five studies emphasize rural tourism’s positive impact on local sustainability. The most co-cited works by Su MM (71 times) and Gao J (53 times) show that SRT enhances livelihoods (Gao and Wu, 2017; Su et al. 2019), underscoring its role in sustainability for rural economies. Ciolac R (33 times) notes its support for environmental sustainability (Ciolac et al. 2019). Ammirato S argues it balances tourist and community needs while promoting economic growth and minimizing adverse ecological effects (Ammirato et al. 2020). Martínez JMG (27 times) finds that SRT creates stable employment and enhances incomes (Martínez et al. 2019).

-

(2)

Three studies highlight challenges in SRT. Rosalina PD identifies internal resource issues as a key challenge to promote SRT (Rosalina et al. 2021); Gössling S identifies COVID-19 as a key challenge to SRT (Gössling et al. 2021); Wang LG notes conflicts over land expropriation, tourism management rights, and house demolition are key factors challenging SRT development (Wang and Yotsumoto, 2019).

-

(3)

Three studies explored the government’s role in SRT. Yang J, the third most co-cited author (41 times), suggests that local governments should implement tourism projects to enhance SRT activities and boost the local economy (Yang et al. 2021). Liu CY argues that collaboration between national and regional governments can accelerate SRT in developing countries (Liu et al. 2020a, 2020b). Lee TH recommends that policymakers consider development opportunities and adopt strategies suited to different SRT communities (Lee and Jan, 2019).

-

(4)

Regarding time and centrality, the most frequently co-cited literature emerged after 2017, indicating rapid growth in this field and increased scholarly attention in recent years. However, these documents generally have low centralities (less than 0.02), suggesting no single document holds significant influence; this may be due to diverse research topics leading to a lack of highly central works.

This analysis implies that rural tourism has promising local, sustainable growth potential, but also faces challenges requiring government coordination and management. Research on SRT covers various aspects (economic, environmental, management), so analyzing this field should include multiple perspectives.

The reference co-citation clusters in Fig. 8 comprise 1,036 nodes and 3,479 links, leading to several findings:

-

(1)

Two clusters focus on tourism forms: cluster #0 (sustainable creative tourism) and cluster #1 (rural tourism). Cluster #0 emphasizes the role of creative tourism in sustainable regional development; rural areas can provide various cultural services and resources, enhancing villages’ values and developing SRT (Santos et al. 2022; Jiang et al. 2023). Yang J’s co-cited literature finds that rural tourism’s cultural forms have changed village spatial structure while boosting rural outputs, suggesting implementing projects to enhance creative tourism activities and promote sustainable economic growth (Yang et al. 2021). Cluster #1 (rural tourism) evaluates rural tourism’s sustainability and impact mechanisms. Key co-cited references include Su, MM 2019, and Gao, J 2017. Su argues that rural tourism enhances livelihood sustainability and diversity (Su et al. 2019), while Gao highlights its significance in rural poverty alleviation by addressing material, social, and spiritual aspects (Gao and Wu, 2017). Notably, cluster #0 (sustainable creative tourism) is featured in Fig. 8 (author collaboration) and 13 (journal co-citation), marking it as a key form of SRT.

-

(2)

Two clusters analyze geographical factors related to SRT: cluster #2 (agricultural landscape) and cluster #4 (Carpathian). Cluster #2 highlights rural mountainous areas as key factors for SRT, suggesting sustainable human-environment interactions via mountainous agricultural tourism (Chen et al. 2024a, 2024b). Cluster #4 focuses on the Carpathian Mountains in Europe, addressing their environmental issues from tourism and emphasizing the need for comprehensive protection of these regions’ scenic, biodiversity, and cultural resources (Turnock, 2002).

-

(3)

Two clusters focus on SRT development: cluster #3 (sustainable tourism development) and cluster #5 (future). Cluster #3 emphasizes residents’ perspectives on sustainable tourism, evaluating SRT indicators. Agyeiwaah E’s research identifies key indicators such as job creation, business viability, waste management, and energy efficiency to foster enterprise-level SRT (Agyeiwaah et al. 2017). Cluster #5 emphasizes principles or approaches to improve future SRT. Co-cited studies show that “industrial ecology” effectively enhances SRT because rural tourism is a part of the industrial system and depends on ecological resources (Erkman, 2001).

-

(4)

Cluster #6 (comprehensive literature review) examines the theoretical research of sustainable tourism. This cluster analyzes academic papers to assess progress in sustainable tourism, identifying key disciplines, journals, articles, and authors (Hashemkhani Zolfani et al. 2015). The co-cited work by Idziak W, stemming from a five-year participatory action research project in Poland, explores the definition, origin, implementation, and problems of themed villages as rural tourism destinations and proposes a seven-step community-based SRT development model (Idziak et al. 2015).

The co-cited literature on SRT covers various themes, implying that SRT research can be conducted through a literature review. Various literature review methods include bibliometrics, meta-analysis, and inductive summarization; they can interconnect SRT studies under different disciplines, impacting policy-making or tourism practice. In addition, literature reviews can help readers understand the current research status, progress, and trends more comprehensively and quickly, helping accelerate this field’s advancement. Therefore, researchers are encouraged to broaden their reading to understand processes and focus areas.

Co-occurrence analysis

Co-occurrence analysis enables scholars to identify evolving research hotspots and clarify emerging directions by examining frequently co-occurring subject categories and keywords and their relationships (Gao et al. 2024c); it answers the research question 3: “What are the main research hotspots in this field?”

Category co-occurrence

Table 9 shows the top 10 co-occurrence categories of SRT. Research on SRT spans various disciplines, including “Environmental Sciences,” “Hospitality,” “Leisure,” “Sport & Tourism,” “Management,” and “Ecology.” Key findings include:

-

(1)

Most categories fall under the natural sciences (7/10), including “Geography” (68 times), “Ecology” (65 times), and “Water Resources” (58 times). That underscores a strong connection between SRT, natural resource management, and environmental protection. Additionally, three categories belong to social sciences (3/10): “Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism” (353 times), “Management” (91 times), and “Regional & Urban Planning” (60 times). That focuses on leisure activities, sports, education, practice, and industrial planning. In summary, research on SRT stakeholders’ activities is also significant.

-

(2)

The category’s high co-occurrence does not equate to a more significant influence. For example, “Green & Sustainable Science & Technology” (630 counts) has a higher co-occurrence but a lower centrality of 0.07. In contrast, “Environmental Studies” (612 counts) and “Water Resources” (58 counts) show lower co-occurrence yet significantly higher centrality at 0.47 and 0.25, respectively. That underscores the importance of environmental and resource issues in SRT research, highlighting that multidisciplinary research is much more influential.

-

(3)

Most categories co-occurred before 2005 (9/10), indicating early scholarly interest and significant influence on later research. The earliest categories, such as “Environmental Sciences,” “Green & Sustainable Science & Technology,” “Environmental Studies,” and “Ecology,” emerged in 2000, reflecting a focus on ecological protection and energy conservation. The latest top co-occurred category is “Regional & Urban Planning” (2006), highlighting an increasing emphasis on SRT’s planning in subsequent studies.

The above findings show that different disciplines are connected through their results and affect policy formulation or tourism practices. For instance, the “Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism” discipline affects SRT policies; a study indicates that policymakers should increase interactions with villagers, create participation mechanisms, and foster cooperation to enhance social welfare. The conclusions provide a basis for formulating SRT policies (Cammarota et al. 2025). Besides, the “Regional & Urban Planning” discipline affects SRT practice; a study highlights the role of collaborative governance in SRT practice, emphasizing that multiple stakeholders, including the local community and the tourism sector, must be involved in SRT decision-making, and SRT practices should be adjusted based on stakeholder perspectives (Valderrama et al. 2025).

The results imply that SRT research is interdisciplinary, encompassing both natural and social aspects. It encourages scholars and practitioners from various fields to contribute to SRT policy formulation and practice with results from their disciplines.

Figure 9 presents the top 7 clusters of co-occurring categories, highlighting hot topics in this field. The details are as follows:

-

(1)

Cluster #0 (case study) and cluster #4 (comparative study) focus on specific SRT cases. Cluster #0 includes “Multidisciplinary Earth Sciences” and “Physical Geography,” examining the interaction between SRT activities and local geographical environments with specific cases. For example, a co-occurring study, with the case in Turkey, demonstrates how geological tourism utilizes unique local features to enhance SRT (Ates and Ates, 2019). Cluster #4 compares cases to evaluate the impact of SRT on villages and ecology, featuring categories like “Agriculture” and “Water Resources.” A significant co-occurring article in this cluster analyzed water resource management in three selected tourism villages, highlighting that effective water allocation is crucial for the sustainable ecology of rural tourism (Zhang et al. 2023a, 2023b).

-

(2)

Cluster #1 (rural tourism) and Cluster #6 (community-based tourism) focus on factors influencing specific tourism types and rural communities. Cluster #1 includes categories like “Hospitality (Leisure)” and “Environmental Studies,” highlighting local industry and the environment’s effects on SRT. Recent co-occurring research has proposed a new model for assessing SRT, highlighting key ecological and environmental factors for improved SRT performances (Huang et al. 2023). Cluster #6, represented by “Green & Sustainable Science & Technology” and “Energy & Fuels,” explores how sustainable science, technology, and energy infrastructure influence SRT. Co-occurring literature in this cluster notes that renewable energy transitions may hinder rural communities, living conditions, tourism potential, and agriculture; therefore, establishing a transparent policy framework and employing modern decision-making models is crucial to tackle these challenges and enhance community-based rural tourism (Pavlakovic et al. 2022).

-

(3)

Cluster #2 (Taunsa Barrage wildlife sanctuary) and cluster #3 (Karst World Heritage Site) emphasize sustainable resource use in rural tourism. Cluster #2 includes “Regional & Urban Planning” and “Development Studies,” highlighting the significance of sustainable tourism planning and wildlife protection. A recent study shows that animals can attract tourists and enhance villagers’ economic returns, indicating their potential as tourist attractions. Providing financial support and maintaining biodiversity is necessary (Jeczmyk et al. 2021). Cluster #3 focuses on sustainable rural heritage tourism, exploring the relationship between cultural/natural heritage and rural tourism. Key categories include “Interdisciplinary Social Sciences” and “Multidisciplinary Humanities.” For instance, recent co-occurring research on the Libo-Huanjiang Karst case in China investigates how ecological, policy, economic, and social resources promote collaboration between heritage conservation and SRT (Zhang et al. 2023a, 2023b).

-

(4)

Cluster #5 (sustainable development) includes “Economics” and “Environmental Sciences,” which focus on SRT’s impacts on local economies, environments, and societies and emphasize the need for effective strategies and policies to promote SRT. For example, while rural tourism can boost local economies, it may threaten wildlife habitats. Therefore, enhancing stakeholder communication, sharing knowledge, collaborating on projects, and strengthening local institutional involvement are essential for promoting SRT’s impacts on the environment and social sustainability (Wezel and Weizenegger, 2016).

The results imply that SRT research has achieved notable outcomes in interdisciplinary fields; Cluster #6 provides theoretical support for the community to introduce SRT development policies; Cluster #0 offers practical guidance for villagers to develop SRT using geological resources; Cluster #5 emphasizes the comprehensiveness and integration of SRT, providing strategic support for sustainable development goals via SRT. These findings emphasize the need for specific and multidisciplinary policies to enable SRT to achieve coupled environmental, economic, and social coordination.

Keyword co-occurrence

The top 10 co-occurring keywords in SRT are presented in Table 10; five keywords directly related to this paper’s theme include “rural tourism” (403 times), “sustainable development” (226 times), “sustainable tourism” (194 times), “tourism” (139 times), and “sustainability” (126 times). Details are as follows:

-

(1)

A keyword’s high co-occurrence does not necessarily indicate a more significant influence. The keyword “rural tourism” is co-occurring most frequently (403 times) but has a low centrality of 0.08. In contrast, “sustainable development” (226 times) and “conservation” (112 times) rank second and eighth, respectively, with higher centralities (0.11). That suggests that while “rural tourism” is popular, its influence is limited. That may be because many studies emphasize “sustainable development” in “rural tourism” rather than “rural tourism” itself, where conservation measures are essential for achieving sustainability.

-

(2)

“Management” (214 co-occurrences) ranks third in co-occurrence frequency. Recent studies highlight ineffective management and improper marketing as significant barriers to SRT in Iran; effective tourism management can enhance rural ecological tourism project performances, which support environmental protection, improve rural livelihoods, and promote rural tourism sustainability (Ghorbani et al. 2021).

-

(3)

The co-occurring keyword “model” (107 co-occurrences) appears later (2012) with a low centrality (0.04), indicating limited influence. However, integrating data into statistical models has shown significant potential in SRT studies. For instance, recent research uses the structural equation model to analyze intangible cultural heritage tourism in villages in China, revealing that familiarity with the destination and perceptions of authenticity boost tourist loyalty, such as revisiting or recommending, thereby promoting sustainable rural intangible cultural heritage tourism (Zuo et al. 2024).

In summary, co-occurring keywords highlight key themes in SRT research and provide insights into evolving trends, aiding researchers in identifying hot topics. A high co-occurrence count does not necessarily indicate a more significant impact; it may reflect a tendency to “chase research trends.” Therefore, scholars require long-term and in-depth tracking of this field.

The keyword co-occurrence timeline cluster in Fig. 10 comprises 690 nodes and 2409 links. Key findings are as follows:

-

(1)

Some clusters, such as #0 (rural revitalization), #4 (satisfaction), and #5 (ecosystem services), are relatively new yet continue to influence current research. For instance, #0 has been gaining recent attention with emerging keywords. Early studies (2005–2015) examined the relationship between rural tourism, like rural food tourism, and sustainable growth in economies, societies, and environments. For instance, research emphasizes cuisine as a vital tourism asset; combining food tourism with agriculture can protect ecologically fragile areas while promoting local sustainability (Montanari and Staniscia, 2009). Subsequent studies (2015–2024) identify rural tourism as essential for sustainable rural revitalization; a representative study found that the rural tourism industry in Beautiful Leisure villages in China helps achieve rural revitalization and sustainability (Xie et al. 2022). Regarding #4 (satisfaction), early research (2004–2010) explored how rural-related consumption affects visitor satisfaction; for example, studies found that rural green energy consumption improves rural environments, positively impacting tourist satisfaction (Li et al. 2005). Later research (2010–2024) analyzed visitor satisfaction using modeling methods, finding that rural tourism providers’ activities enhanced visitor satisfaction (Polo Pena et al. 2012). Recent studies show that place attachment mediates rural community SRT participation and residents’ satisfaction (Jia et al. 2023). #5 (ecosystem services) highlighted SRT strategies in its early stage (2004–2010), showing that value-oriented decisions impact SRT management (Kajanus et al. 2004). The mid-term period (2010–2018) examined factors affecting ecosystem services in SRT, including sustainable landscape management and rural community capital (Stone and Nyaupane, 2016). Recently (2018–2024), there has been an increased focus on the resilience of SRT destinations; densely populated agricultural areas are less resilient and require tailored strategies (Chand et al. 2024).

-

(2)