Abstract

Nudges are behavioral interventions to subtly steer citizen choices by making desirable options easier or more attractive. More than 15 years of research and practice have revealed that such gentle encouragements are effective policy instruments in directing personal decisions without violating the principles of good governance. However, with a focus on individual behavior, there has been less attention to nudges as a policy device for promoting decisions that are good for all of us and tackle societal challenges that require collective effort. In the present review, I address this knowledge gap by introducing the novel concept of community nudges. I discuss a new outlook that seeks to understand how nudges may support communities in making decisions to shape desirable outcomes for the benefit of all. I suggest two avenues for designing community nudges that support people in committing to a common cause. One way is the creation of nudges that call for considering other people’s concerns by speaking to their ability to empathize. Another way is to facilitate people to act together as a group to contribute to a common cause, resonating with recent calls for collective action in addressing critical societal problems. I present initial evidence that community nudges have the potential to increase collective commitment by avoiding an excessive focus on individual responsibility for problems that demand collaborative action. In the final section, I describe the opportunities and challenges for the implementation of community nudges in public policy by connecting the emerging evidence on community nudges with the literature on collaborative governance as an alternative for attempts to secure acceptance of top-down generated solutions for important problems that affect us all.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nudges, defined as an instrument to steer citizen choices in a gentle way (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008), have been around in public policy for more than 15 years. Taking a middle position between free choice versus paternalistic guidance in a wide variety of policy issues (e.g., the energy transition or the obesity epidemic), these soft paternalistic tools (but see e.g., Gigerenzer, 2015; Grüne-Yanoff, 2012; McCrudden and King, 2016 for different views) have generated both enthusiasm and criticism in academic and societal circles. The enthusiasm often relates to the subtle hints for doing the right thing, which make nudges a compelling instrument for policymakers who can then influence citizen choices without coercion (Benartzi et al., 2017). Criticism lies in worries about governments taking advantage of cognitive ‘flaws’ in human decision making as identified by behavioral scientists, which would threaten the standards of fair and just governance (Bovens, 2009). To be sure, the very notion of nudges as policy instruments relying on psychological techniques has generated much debate on nudging ethics (e.g., Tannenbaum et al., 2017; Wilkinson, 2013), in particular concerning the risk of violating citizen autonomy in decision making (Wachner et al., 2020). Relatedly, there has been debate about issues associated with possibilities for implementation in existing policy arrangements (De Ridder et al., 2024a).

Yet, there is another matter inherent to nudges as a policy device that has often been overlooked: there may be some tension in nudges supporting individuals to make better choices without explicitly communicating that such choices serve policy objectives relating to the common good rather than the personal benefit of the nudged individuals only. Nudges that encourage vaccination, for example, may contribute to the protection of one’s own health but are at the same time (and maybe even primarily) essential instruments for protecting population health from the spreading of infectious diseases (Dai et al., 2021; De Ridder et al., 2023a); a well-known paradox that has been already noted decades ago by epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose (1981). In some cases, individual benefit is even less apparent such as when people are nudged to reduce single-use plastic cutlery, which may contribute to a greener environment but not necessarily result in (immediate) improvements in one’s own life (He et al., 2023). Here, I argue that acknowledging this seeming incongruity does not impose limitations upon the potential of nudges as a policy instrument but rather enhances it. Explicit communication that certain choices concern society as a whole may provide a more compelling argument to change one’s behavior than just doing it for oneself. Telling people that nudges aim to address the benefit of all may even increase their willingness to make behavioral changes that are required in view of problems such as climate change, pandemic threat or any other complex issue that requires massive engagement.

In case of the climate crisis, for example, people report having a hard time in considering their own behavior as being part of a bigger system, either because they feel overwhelmed by the futility of their behaviors in view of the scope of problem (Gifford, 2011) or because they think that it is beyond their own personal responsibility (Obradovich and Guenther, 2016). Speaking to a broader community effort could resolve these experiences of helplessness and powerlessness by making a call on people’s inherent aptitude for caring about others (Keysers and Gazzola, 2014). There is ample evidence from fundamental research demonstrating that the ability to empathize critically impacts prosocial behavior (Batson et al., 2015). However, research has also shown that it may not be so easy to turn on this ability by whatever kind of behavioral intervention (e.g., Batson & Ahmad, 2009; Weisz et al., 2021). Here, I propose a novel understanding of nudges that may empower people to contribute as a collective. I make a case for a new type of nudges that unlock the power of the community by making a call on what people can do together for the sake of communal benefit, which I label community nudges. I suggest that the sense of community in community nudges is twofold, as it refers both to the process (people acting together) and the outcome (benefit for all), which I will explain in detail in the following. In doing so, I realize that many proposals for novel nudge types have been made, such as, for example, hypernudges (Yeung, 2016) or self-nudges (Reijula and Hertwig, 2020). However, by introducing the concept of community nudges, I call for an explicit and fundamental consideration of a neglected aspect of nudging that spotlights people as social beings. Rather than adding a new type of nudge to the existing repertoire, our primary aim is to reconsider what nudges are (or should be) about.

Our proposal rests on the notion that people are responsive to appeals that accentuate the common good because of embodied mechanisms that enable them to empathize with other people’s needs and concerns. Research on empathic processes, based in the brain’s mirroring systems, provides robust evidence that people are able to directly perceive, understand, simulate and predict the goals, actions and emotions of others, as well as to evaluate the consequences of their own actions for others as if they concerned themselves (e.g., Keysers and Gazzola, 2014). Empathy is strongly associated with altruism (Batson et al., 2015) and reciprocity (Von Bieberstein et al., 2021). Together, these insights provide the psychological foundation for the design of policy arrangements that prompt (groups of) individuals to consider the concerns of others rather than assuming that self-regarding motives are the primary drivers of human behavior (Oliver, 2018a).

Our proposal also corresponds with recent criticism suggesting that nudges focus too much on behavior change by individuals, where system revisions in legislation, regulation, and taxation would be more appropriate to generate societal change (Chater and Loewenstein, 2022). I very much agree with the notion that nudges, as we know them, may inadvertently hold individuals responsible for things way beyond their influence. However, rather than altogether banning behavior change from public policy making, I suggest that shifting the focus from individual behavior to community behavior may significantly contribute to system transformations. System change and behavior change are not separate entities but fundamentally co-dependent and have the potential to reinforce each other (De Ridder et al., 2023b).

In the following, I advance a community approach to nudges that addresses the shortcomings of the present individual focus in classic nudging. First, I review existing research showing that nudges, as we know them, neglect the necessity of speaking to communities for solving important societal issues. Next, I introduce a new outlook that seeks to understand how nudges may support communities in making decisions to shape desirable outcomes for the benefit of all. I suggest two avenues for designing community nudges that support people in committing to a common cause. One way is the creation of nudges that call for considering other people’s needs by speaking to their ability to empathize. Another way is to facilitate people to act together as a group to contribute to a common cause, resonating with recent calls for collective action in addressing important societal challenges. In the final section, I describe the opportunities and challenges for nudging policies inspired by this broader view on nudges.

Nudges for improving personal decision making

Nudging as a strategy for improving decisions ‘about health, wealth and happiness’ (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008) or ‘the environment’ (instead of happiness; Thaler and Sunstein, 2021) has great advantages compared to more traditional interventions for influencing citizen behavior such as educational public campaigns (Benartzi et al., 2017). Nudges respect that people do not always prioritize the right choice due to ignorance, inertia or lack of willpower (Bovens, 2009). As such, they are an indispensable addition to the policymaker’s toolbox for helping people to decide in their own best interest at moments when they are distracted or forgetful. In this section, I review research from the past decade that has shown a strong focus on nudges as a policy instrument for improving choices made by individuals that are good for themselves. I argue that the individual approach to nudging ignores that people belong to communities, which hampers its prospects as a strategy to tackle issues that are relevant to all of us.

More than fifteen years of nudge research and practice have shown that nudges come in a wide variety of psychological concepts that can be used for their design, including incentives, norms, defaults, salience, priming, affect or commitment (Dolan et al., 2012). As a result, there has been much debate about what nudges are, how they should be defined, and how they should be sorted (e.g., Hollands et al., 2017; Marchiori et al., 2017; Münscher et al., 2015). Multiple attempts have been made to classify this variety into comprehensive categories, such as the TIPPME typology comprising a matrix classification of six intervention types and three different spatial foci (Hollands et al., 2017).

Here, I suggest that—in line with the definition of nudges as a policy instrument for helping people to make better decisions rather than a regular psychological intervention—nudges can rely on any psychological technique that seems appropriate as long as people are given a fair chance to decide otherwise. Whereas earlier work has contested whether nudges allow for doing so (e.g., Bovens, 2009; Wilkinson, 2013), recent research on nudgeability (susceptibility to being affected by a nudge) has demonstrated that concerns about the legitimacy of nudges as a policy instrument should be softened (De Ridder et al., 2022b). It has been proposed that nudges may be ineffective when they are not concordant with people’s pre-existing preferences and goals, suggesting that people cannot be nudged into a choice they don’t endorse (Venema et al., 2019). There is also evidence that people are equally responsive to nudges regardless of whether their presence, purpose, or working mechanisms are revealed, showing that transparency does not compromise nudge effects (e.g., Bruns et al., 2018; Loewenstein et al., 2015; Paunov et al., 2018). Finally, and in contrast with the understanding that nudges would only work ‘in the dark’ (when people are unaware of their presence; Bovens, 2009), multiple studies have now shown that nudges are still effective when people are prompted to critically reflect on their choice (Steffel et al., 2016; Van Gestel et al., 2020). Van Gestel et al. (2020), for example, demonstrated in a series of preregistered and high-powered studies that a default nudge for promoting green choices was equally effective regardless of whether people were encouraged to think carefully about their decision or not, showing that reasoning does not compromise nudge effects.

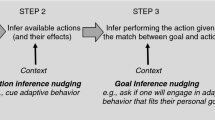

These nudgeability insights have spurred reconsideration of the working mechanism underlying nudge effectiveness. In contrast with early work emphasizing that nudge success would rely on automatic processing (i.e., when people are in a ‘system 1’ mode of thinking), there is now consensus that nudges are also effective when people are in a deliberative (‘system 2’) mindset (De Ridder et al., 2022b). As a result, recent years have witnessed growing attention to a new generation of nudges that explicitly stimulate active decision making rather than simply making desired choices easier or more attractive. These novel nudges hold different labels, such as system 2 or educative nudges (Sunstein, 2016) or nudge+ (Banerjee and John, 2024; Banerjee et al., 2023)—which I will group by using the overall term ‘think’ nudges (John et al., 2009; cf. Keller et al., 2011) in the following. Whereas their theoretical underpinnings may slightly differ, these nudges have in common that they aim to enhance agency and empower people in making the right decision. To stimulate deliberative reasoning, these nudges are accompanied by mere information provision (reminders and warnings) or hints to think carefully about one’s choices, either or not in combination with transparency about nudge presence or purpose (nudge+; Banerjee et al., 2023). In a similar vein, while conceptually different from nudges, it also boosts aim to encourage reflection on choices by improving decision-making skills (Hertwig, 2017; Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff, 2017). It is believed that these new types of nudges allow for more citizen engagement with public polices because they invite people to make active decisions, which in turn could increase support for these policies (Banerjee and John, 2023; Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff, 2017). Encouraging people to think about their choices in combination with an explanation of the nudge, as in nudge+, might even help to involve people with the design and implementation of public policies as an alternative to them being mere passive recipients of policies (Banerjee and John, 2023).

Together, the new generation of think nudges may take away concerns about the legitimacy of nudging as a policy instrument—even though legitimacy issues with classic nudges have already proven less severe than initially thought. However, one may wonder to what extent nudges really allow for more active citizen involvement with critical policy issues that require collective effort. Despite their promise to do so more than ‘type 1’ nudges, think nudges still maintain an individual focus by speaking to people as individuals who are making decisions by themselves without realizing how their choices may (or may not) contribute to the benefit of all. Similar to regular nudges, then, think nudges typically ignore the social dimension of the problem that they are trying to address. By giving people an opportunity to reflect on their decision to eat more healthily or opt for green energy, they may become more aware of the relevance of these policy issues, but they may still look on it as something they must deal with on their own and for their own benefit. I propose that adding a social component to nudges may critically enlarge their effectiveness by making explicit that desirable choices serve society as a whole, resulting in, for example, lower health care costs (in case of adopting a healthy diet) or a sustainable planet (in case of green energy choices).

Simply inviting people to reflect on their decisions will not automatically resolve this problem of collective action that is required for tackling the societal challenges that nudges promise to address (OECD, 2017; World Bank, 2015). More deliberation may even cause people to prioritize their own interests rather than care about the common good (Banerjee and John, 2023). Rather than thinking, highlighting the social nature of desired choices may better support people in doing the right thing, as has been suggested previously (Mols et al., 2015; Van der Linden, 2018). Mols and colleagues (2015), for example, argue that nudge effectiveness rests on the extent that people feel part of a group whose norms they internalize and enact because they tend to look at others whom they perceive as similar to themselves for meaningful forms of guidance.

In a way, existing social norms that draw attention to what others do or consider the right thing to do already address the social dimension of personal decisions. Social norm nudges are a well-established way to regulate individual behavior because they raise normative expectations about what is desirable and provide guidance when someone is uncertain about what to do (Cialdini and Trost, 1998), even when the desired behavior is not yet the norm (Sparkman and Walton, 2017). Still, social norm nudges tend to employ statistics on the behavior of others as a technique to influence individual decision making rather than as a strategy to inspire collective action. The prevailing practice is that social norms are used as information that can be communicated in simple messages to motivate behavior change, ignoring the necessity of grounding social norm interventions in group practices to encourage collective effort (Prentice and Paluck, 2020).

Next to social norms, the concept of community nudges bears similarities with pro-social nudges (focusing on social welfare) as distinct from pro-self nudges (focusing on private welfare; Hagman et al., 2015). However, in this approach, it is emphasized that people are naturally inclined to prioritize their own welfare and, for that reason, may be reluctant to engage in prosocial behavior that would be required to achieve a common societal goal. Similarly, behavioral economists believe that nudges may focus on positive externalities (behavior that may bring benefit to others as a result of one’s own actions), but again cast doubt on whether people are willing to do so because they are preoccupied with their own immediate interest (Oliver, 2018b). Indeed, the focus of classic nudges strongly lies on benefits ‘as judged by themselves’ (Sunstein, 2018), which can be interpreted as by and for themselves. However, one can imagine that this could be extended to ‘as judged by (and for) themselves as a community’ (cf., Gold et al., 2023).

When the policy objective is to create true engagement with societal challenges and encourage collective action, conveying social norms or other types of prosocial nudges may thus not be sufficient to tackle the social dimension of behaviors that nudges aim to influence. A more powerful manner for engaging people with public policies lies in speaking to them as members of a community, either by giving them prompts that explicitly call for the consideration of others or by straightforwardly inviting cooperation with others. In the next section, I will discuss emerging research on nudging as a device to engage communities with such prosocial choices. This new approach also goes beyond nudges as a mere top down instrument aiming to engage people with pre-existing policy goals and gives more room to communities to find their own ways to contribute to societal issues as a sign of true engagement—thus advancing notions on collaborative governance (Ostrom, 2009).

Community nudges

In recent years, the role of groups of people or collectives in addressing societal challenges has become an increasingly popular approach in public policy (Amel et al., 2017; Fritsche and Masson, 2021). In view of the scale of problems such as climate change or public health matters (e.g., obesity, vaccination), collective effort is required for securing large-scale contributions. However, in spite of its popularity, it is not so clear how collective action could be accommodated. Most of the research on collective action, generally understood as action taken together by a group of people whose goal is to achieve a common objective (Wright, 2009), favors a competitive approach and highlights perceived injustice as the main driver of getting together. This perspective typically emphasizes clear boundaries between ingroup and outgroup members with a strong focus on social identity as the main mechanism to act together against a common outsider, such as in protest groups standing out against the fossil industry for addressing climate change (Agostini and Van Zomeren, 2021; Van Zomeren et al., 2008). In contrast, a cooperative approach to collective action highlights inclusivity and compassion towards outsiders (Bamberg et al., 2015; Wright, 2009) but has received less attention.

In view of free rider issues that may emerge when large groups of people who may not know each other personally are supposed to contribute to the common good (Olson, 1965), typical for a competitive understanding of collective action, the cooperative approach lends itself well for nudging collective action (Sarabi et al., 2024). However, this approach has thus far not been recognized as a promising avenue for implementation in public policy settings. In this section, I review emerging research that has begun to identify and acknowledge the potential of nudges to turn on the we mode by speaking to people as being part of a community. This research involves ecologically valid field studies observing how prompts to consider the benefit of others may help people to transcend their own personal interest and highlights the relevance of communal benefit when making personal decisions. Another line of research examines the consequences of giving people the opportunity to get together and work on a shared objective in coordinated effort, which may enhance collective efficacy and commitment to a common cause.

Nudging people to consider the benefit of others

The COVID-19 pandemic required behavioral scientists to think of creative solutions and design nudges that would support people in changing their behavior to curb the spread of the virus (Van Bavel et al., 2020). Whereas most nudge interventions were geared at making desired personal decisions about distancing, vaccination or wearing mouth masks more salient, the pandemic also inspired research on ‘protect each other’ nudges by encouraging people to change their behavior for the benefit of others rather than themselves only (e.g., Pfattheicher et al., 2020). These kinds of prosocial nudges are thought to be effective because they increase empathy for people vulnerable to the virus. Concrete images and the actual voices of those in need of protection may help people to act in the collective interest during times of crisis. In a field experiment at a university campus, it was tested whether empathy nudges calling for the consideration of vulnerable others (see Fig. 1) would support actual distancing behavior (beyond the mere intention to do so; Pfattheicher et al., 2020) when there was a high probability of getting too close to each other. Using camera registrations of distances between people (both students and staff) at three hot spots where there was a possibility of crowding, significant positive effects of empathy nudges were found with people standing up to 35 cm farther away from each other (a distance that is relevant for reducing the risk of infection) while accounting for the number of people present as compared with a condition when empathy nudges were absent (De Ridder et al., 2022a). Critically different from a classic social norm nudge that would suggest that people change their behavior because it is expected of them, our experiment tested whether inviting people to consider other people’s concerns did increase their prosocial distancing behavior, thereby minimizing the risk of reactance because of calling on their aptitude for empathy. Similar results of referring to communal benefit were found in a study aiming to reduce garbage in urban neighborhoods by making a call on the consideration of other people’s needs (‘I keep our street clean—outdoors belongs to us all’; Merkelbach et al., 2021).

These findings align well with the notion of social affordances as an alternative for classic system 1 & 2 theorizing about nudges. Rather than making the option of physical distancing more salient by putting arrows on the floor as the majority of COVID-19 nudges did, the concept of social affordances posits that features of a social situation (i.e., empathy prompts) may invite a natural response that involves caring about others (Valenti and Gold, 1991). Similar to classic affordances that signal the relevance of a particular action goal in the situation at hand (Gibson, 1977), such as grasping for a mug when the handle is pointed towards one’s dominant hand, social affordances call for the consideration of other people’s needs on the spot. To date, an affordance-based understanding of nudges has yielded promising results in encouraging personal healthy dietary choices—for example, by putting unhealthy food at a larger distance (De Ridder, 2023; Gillebaart et al., 2023; Junghans et al., 2013; Maas et al., 2012; see Van Dessel et al., 2022 for another example)—but there is much more to gain from research investigating when and how affordances may engender ‘wise’ choices (Walton and Yeager, 2020) that open up prospects for non-paternalistic form of choice architecture (Sher et al., 2022). The social affordance concept with its emphasis on ‘invitingness’ to consider other people’s benefit, may provide a unique avenue for prosocial nudge design by making this option more relevant. This may not only concern the health and well-being of other people but extend to more abstract common causes (e.g., climate change) as well.

Nudging people to act together

Another way of engendering prosocial choices is to nudge people to get together to make group contributions to a problem. People are uniquely able and motivated to collaborate and experience inherent pleasure from working together, even when it is less efficient than working alone (Curioni et al., 2022). Working on a collaborative task has been shown to promote intrinsic motivation and personal commitment (Michael et al., 2016) as well as prosocial attitudes and behaviors, including stronger social bonds, trust, and helping behavior (Atherton et al., 2019; Carr and Walton, 2014; Cojuharenco et al., 2016; Sarabi et al., 2024). Inviting people as a group to provide their input for the resolution of societal challenges is important for a number of reasons (Fiorino, 1990). Community involvement not only helps to secure support for governments in achieving their policy objectives, but it is also ‘the right thing to do’ in a democracy because citizens should have a say in governmental decisions that will deeply affect their lives. Importantly, community involvement may even improve the quality of policy decisions because citizens ideas are not constrained by legalistic or bureaucratic considerations and have the potential to be a source of collective wisdom to solve problems. The integration of collective views from the public may thus contribute to innovative, higher-quality policies that are tailored to meet the full range of perspectives present within a community. How can nudges be employed to facilitate communities in getting together to contribute to public policy issues? In a study on collective engagement with pandemic management at a university campus, small groups of students and staff were invited to work together in constructive dialog and generate context-specific solutions as if they were responsible for implementing COVID-19 policies in the university setting (Gootjes et al., 2024). To unleash the power of the academic community, they were provided with the opportunity to design measures that addressed their own needs and priorities, rather than merely expressing their preferences for a given set of scenarios (Marston et al., 2020). Multiple groups of about 5–10 participants proved able to jointly compose a set of measures meeting the criterion of a safe educational environment that reduced the risk of infection while at the same time allowing for some form of social interaction. Importantly, all participants felt responsible and appreciated that they were given a say in campus COVID-19 policies. This research demonstrates the relevance of nudging collective action in cooperation as a promising but underexplored pathway to promote engagement with public policies beyond mere persuasion of individuals. Nudging community action may thus simply take the form of providing people with the opportunity to get together and discuss their contributions to a joint cause. Similar observations have been made when giving groups of people the opportunity to design a sustainable food environment in their immediate neighborhood surroundings (Moojen et al., 2024).

Coordinated action

Another approach for facilitating cooperative collective action lies in creating favorable conditions for working together by giving people the opportunity to coordinate their behavior. Drawing on notions from social neuroscience showing that acting in coordination promotes prosocial behavior (Michael et al., 2020; Sebanz and Knoblich, 2021; Sebanz et al., 2006), nudges might be employed to encourage such coordination. In a series of field experiments, it was shown that potting plants in coordination (i.e., groups of five people potting plants in one big pot) increased prosocial behavior as compared with potting plants individually (i.e., groups of five people potting a plant in their individual pot each on their own) in energy cooperatives who were recruiting residents to contribute to the energy transition in their neighborhood (De Ridder et al., 2024b). While accounting for the mere company of others, which was similar in both conditions, the coordination of actions in communal plant potting generated medium to large effects on connectedness with other group members, collective efficacy, and commitment to the task. Moreover, people in the coordination condition expressed greater willingness to engage in future group activities related to the energy transition. These findings align well with the results from fundamental lab research (Sarabi et al., 2024) but for the first time these field studies demonstrated that nudging coordinated action is also feasible and effective in the more noisy real life setting of citizen initiatives. Importantly, the outcomes of this research are impressive in view of previous failed attempts to bring people together in energy communities to work on their common interest in energy reduction (Bal et al., 2021; Blasch et al., 2021). It may thus well be that the simple act of coordination is a critical driver of prosocial behavior that lends itself well to nudge collective action for communal benefit. The power of coordination is also acknowledged in research on coordination games, stating that players will get the best possible payoff by choosing strategies that serve their common interest (Cooper, 1999)—implicating that thinking beyond the impact of one’s own actions and considering what happens when people act as part of group is the key to major changes on a societal level.

This shift in thinking about how individuals might contribute to the common good holds important consequences and may transcend the ‘disputable duality’ (Bandura, 2000, p. 77) that pits individual behavior against institutional structures as representing different levels of influence. More than twenty years ago, Bandura (2000; see Hamann et al. (2023) for a recent review) noted that social structures and the behavior of (groups of) individuals are not independent but are deeply intertwined. To better integrate both levels, he introduced the concept of ‘collective agency’, defined as people’s shared beliefs in their collective power to produce desired results. At the time, Bandura emphasized that collective agency does not so much result from the sum of knowledge or skills of a group of people but rather emerges from their interactive, coordinative and synergistic transactions—thus already then noting that coordinated action in groups may be a critical driver of collective contributions. Viewed from this perspective, reservations about the role of behavior in public policy (Chater and Loewenstein, 2022) may not so much lie in the role of behavior itself but rather in the focus on individual behavior, neglecting the power of collective behavior of an entire social group.

Leveling up: linking microlevel to macrolevel

To explore the scaling potential of this approach, it is urgent to link micro-level insights into the group dynamics of coordination to a macro-level perspective that allows for the promotion of collective action by nudging interventions. Before we can do so, we need to know more about the contextual factors that allow for nudging coordinated action in real-life settings. This requires an answer to questions such as: How well should people know each other (should they even know each other)? Should they have an opportunity to look each other in the eye and physically meet, or could they also work together in virtual settings?’Do people have to engage in coordinated action themselves, or can they also become engaged by observing other people working together? Should they share a common background, or will working together compensate for the lack of having something in common from the start? In finding answers to these and other pressing questions, psychological science could build on what is already known about the ‘grammar’ of institutions for collective action (Ostrom, 2009). There is a wealth of research demonstrating that people choose for collective benefit instead of prioritizing their own needs when they meet in citizen collectives for the provision of energy, food and other goods and services (Farjam et al., 2020). It has been argued that constructive citizen involvement should be a critical feature of policy design. Policies co-produced by communities better reflect local needs and are more effective in dealing with complex problems (Durose and Richardson, 2015). In view of the revamp of the Ostromian perspective, it is important the we back up this authoritative approach with quantifiable elements that lend themselves for application in public policy arrangements to accommodate the contribution of people to policy issues that require effort of all of us.

Discussion

Nudges have been around in research and policy settings for almost two decades. In spite of early reservations about their legitimacy, they have shown great potential to influence personal decisions about health, finance, and sustainability matters without violating the ethical principles of public policy in terms of transparency and freedom of choice (De Ridder et al., 2022b). Still, as a policy instrument, nudges have failed to engage people with societal challenges that require widespread involvement. Reflections on nudging ‘for good’ (Lades and Delaney, 2022), emphasizing that nudges should improve the welfare of those being nudged, do not mention anything about contributing to the common good as a key principle of public policy. Also the new generation of think nudges will probably not automatically invite caring about collective benefit. Despite the recognition that we need nudges that give individuals the opportunity to act together in reaching collective outcomes (Banerjee and John, 2023; Van der Linden, 2018), few attempts have been made to design and test nudges that encourage people to act in support of common interest. I have introduced the novel concept of community nudges to address this gap. Whereas empirical evidence is still scarce, initial findings are promising. Nudges calling for the consideration of other people’s needs engender empathizing with others and behavior change to their benefit (De Ridder et al., 2022a). Moreover, we can nudge people to get together and act as a community to contribute to problems that transcend their own individual needs (Gootjes et al., 2024; De Ridder et al., 2024b). The concept of community nudges is rooted in solid theoretical and empirical evidence on cooperative collective action principles that foreground coordination between people in achieving a shared goal, giving credit to its potential as a new policy instrument. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that it may be challenging to design (or co-create) community nudges that go well beyond the explicit mentioning of the needs and concerns of other people, as has been done in most research so far (De Ridder et al., 2022a; Merkelbach et al., 2021; Pfattheicher et al., 2020).

Here, I made a first attempt to connect insights on cooperative collective action with the nudge literature. Future research should create stronger links between these two lines of research by investigating how cooperative collective action in community settings can be facilitated (nudged) in policy arrangements. Different from the competitive collection action approach that lends itself less well for implementation in public policies (because it highlights citizen initiatives acting against a common outsider), the cooperative collective action paradigm holds great promise to accommodate collaboration between people in neighborhoods and other (local) settings and engage them with societal challenges that affect all of us. In view of the need to accelerate collective action beyond existing cooperatives and other kinds of citizen initiatives who are willing and able to organize themselves (Farjam et al., 2020), there lies an important task for public policy officers to nudge collaboration in groups who do not naturally get together to work on a common cause (De Ridder et al., 2023b). While recognizing that some citizens don’t need policy support to care for their mutual interest, it should be acknowledged that other people and especially those from underprivileged groups, may need some assistance to get organized and create a setting for better mutual support.

Interestingly, the seminal work of Ostrom (2009; Poteete et al., 2010; Durose and Richardson, 2015) on collective action governance has noteworthy parallels with elements that I identified in cooperative collective action research. Creating opportunities for the collective design of nudges allows for tailoring a nudge to community needs, highlighting that acting together is a crucial ingredient of collective engagement and caring about communal needs. This perspective aligns well with recent models of multilevel governance (Ansell and Gash, 2008), positing that collaboration between citizens, community initiatives, service organizations, and governmental agencies allows for experiencing closeness, cultivating trust, and building a shared perspective in such a way that these outcomes may mutually reinforce each other. Community nudges may bridge the gap that is currently existing between the body of knowledge on collaborative governance on the one hand and psychological insights into collaborative collective action on the other. In that way, nudges can fulfill their promise as a policy instrument to ignite collective engagement with societal challenges. Community nudges may create the conditions that provide members of a community with opportunities to contribute to the design of innovative solutions to pressing societal challenges by presenting them with settings where they can experience that partners will act cooperatively. By doing so, fostering engagement goes well beyond securing support for policies that have been designed top down (Grelle, Hofmann, 2024) without active involvement of citizens to co-create and integrate their views on societal challenges. Moreover, a stronger focus on people as members of a community may critically take away concerns about an excessive individual frame that holds individuals responsible, where system changes would be more appropriate (Chater and Loewenstein, 2022).

I conclude that community nudges that speak to people as members of a community may help them care about others and the public good. Moreover, community nudges provide a much-needed policy instrument to support collective action that has been proposed as a promising strategy for addressing societal challenges that concern all of us. Importantly, community nudges may soften concerns about the emphasis on individual responsibility that characterizes classic nudges by speaking to people as being part of a collective. Future research should examine whether community nudges that have already been shown to promote prosocial behavior are helpful for people to understand their own role in the bigger system and give them the motivation and the opportunity to contribute to the common good. Finally, community nudges may also empower people and give them more grip on their lives because they have more say about what’s going on in their environment (De Ridder, 2024; Hofmann, 2024).

Data availability

No data were collected for this study.

References

Agostini M, Van Zomeren M (2021) Toward a comprehensive and potentially cross-cultural model of why people engage in collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of four motivations and structural constraints. Psychol Bull 147:667–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/BUL0000256

Amel E, Manning C, Scott B, Koger S (2017) Beyond the roots of human inaction: fostering collective effort toward ecosystem conservation. Science 356:275–278. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal1931

Ansell C, Gash A (2008) Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J Publ Adm Res Theory 18:543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

Atherton G, Sebanz N, Cross L (2019) Imagine all the synchrony: the effects of actual and imagined synchronous walking on attitudes towards marginalised groups. PLoS One 14:e0216585. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216585

Bal M, Stok FM, Van Hemel C, De Wit JBF (2021) Including social housing residents in the energy transition: a mixed-method case study on residents’ beliefs, attitudes, and motivation toward sustainable energy use in a zero-energy building renovation in the Netherlands. Front Sustain Cit 3:656781. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.656781

Bamberg S, Rees J, Seebauer S (2015) Collective climate action: determinants of participation intention in community-based pro-environmental initiatives. J Env Psychol 43:155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.06.006

Bandura A (2000) Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 9:75–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00064

Banerjee S, Galizzi MM, John P, Mourato S (2023) Sustainable dietary choices improved by reflection before a nudge in an online experiment. Nat Sustain 6:1632–1642. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01235-0

Banerjee S, John P (2023) Nudge+: putting citizens at the heart of behavioral public policy. In: Research Handbook on Nudges and Society. Elgar Publishing. pp. 227–241

Banerjee S, John P (2024) Nudge Plus: incorporating reflection into behavioral public policy. Behav Publ Policy 8:69–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2021.6

Batson CD, Ahmad NY (2009) Using empathy to improve intergroup attitudes and relations. Soc Issues Policy Rev 3:141–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2009.01013.x

Batson CD, Lishner DA, Stocks EL (2015) The empathy—Altruism hypothesis. In: The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial Behavior. Oxford University Press. pp. 259–281

Benartzi S, Beshears J, Milkman KL, Sunstein CR, Thaler RH, Shankar M, Tucker-Ray W, Congdon WJ, Galing S (2017) Should governments invest more in nudging? Psychol Sci 28:1041–1055. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617702501

Blasch J, Van der Grijp NM, Petrovic D, Palm J, Bocken N, Mlinaric M (2021) New clean energy communities in polycentric settings: Four avenues for future research. Energ Res Soc Sci 82:102276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102276

Bovens L (2009) The ethics of nudge. In: Preference change: approaches from philosophy, economics and psychology. Springer. pp. 207–220

Bruns H, Kantorowicz-Reznichenko E, Klement K, Jonsson ML, Rahali B (2018) Can nudges be transparent and yet effective? J Econ Psychol 65:41–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2018.02.002

Carr PB, Walton GM (2014) Cues of working together fuel intrinsic motivation. J Exp Soc Psychol 53:169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.03.015

Chater N, Loewenstein GF (2022) The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Behav Brain Sci 1–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X22002023

Cialdini RB, Trost MR (1998) Social influence: social norms, conformity and compliance. In: The Handbook of Social Psychology. McGraw-Hill. pp. 151–192

Cojuharenco I, Cornelissen G, Karelaia N (2016) Yes, I can: feeling connected to others increases perceived effectiveness and socially responsible behavior. J Env Psychol 48:75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.09.002

Cooper RW (1999) Coordination games. Cambridge University Press

Curioni A, Voinov P, Allritz M, Wolf T, Call J, Knoblich G (2022) Human adults prefer to cooperate even when it is costly. Proc R Soc B 289:20220128. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0128

Dai H, Saccardo S, Han MA, Roh L, Raja N, Vangala S, Modi H, Pandya S, Sloyan M, Croymans DM (2021) Behavioral nudges increase COVID-19 vaccinations. Nature 597(7876):404–409. 41586-021-03843-2

De Ridder DTD (2023) Nudgeability and beyond: Affording people with opportunities to make the right choice. In: Research Handbook on Nudges and Society. Elgar Publishing. pp. 17–33

De Ridder DTD (2024) Getting a grip on yourself or your environment: creating opportunities for strategic self-control in behavioral public policy. Soc Pers Psychol Comp 18:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12952

De Ridder DTD, Aarts H, Benjamin JS, Glebbeek M, Leplaa H, Leseman PPM, Potgieter R, Tummers LG, Zondervan-Zwijnenburg M (2022a) Keep your distance for me: a field experiment on empathy prompts to promote distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Comm Appl Psychol 32:755–766. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2593

De Ridder DTD, Aarts H, Ettema D, Giesen I, Leseman PPM, Tummers LG, De Wit J (2023b) Behavioral insights on governing social transitions. Utrecht University Institutions for Open Societies Think Paper Series, no. 5. https://doi.org/10.23668/psycharchives.13228

De Ridder DTD, Adriaanse MA, Van Gestel LC, Wachner J (2023a) How does nudging the COVID-19 vaccine play out in people who are in doubt about vaccination? Health Policy 134:104858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2023.104858

De Ridder DTD, Feitsma J, Van den Hoven M, Kroese FM, Schillemans T, Verweij M, Venema AG, Vugts A, De Vet E (2024a) Simple nudges that are not so easy. Behav Publ Policy 8:154–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.36

De Ridder DTD, Kroese FM, Van Gestel L (2022b) Nudgeability: mapping conditions of susceptibility to nudge influence. Persp Psychol Sci 17:346–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691621995183

De Ridder DTD, Verweij R, Gootjes F, Gillebaart M, Sarabi S (2024b) Planting the future: fostering collective engagement with the energy transition by coordinated action. https://osf.io/8qtge/?view_only=1cf712cc9237454ead83a7c9dfbc04ae

Dolan P, Hallsworth M, Halpern D, King D, Metcalfe R, Vlaev I (2012) Influencing behaviour: The Mindspace way. J Econ Psychol 33:264–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.10.009

Durose C, Richardson L (2015) Designing public policy for co-production: theory, practice and change. Bristol University Press

Farjam M, De Moor T, Van Weeren R, Forsman A, Dehkordi MAE, Ghorbani A, Bravo G (2020) Shared patterns in long-term dynamics of commons as institutions for collective action. Int J Commons 14:78–90. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijc.959

Fiorino JD (1990) Citizen participation and environmental risk: a survey of institutional mechanisms. Sci Techn Hum Val 15:226–243. https://www.jstor.org/stable/689860

Fritsche I, Masson T (2021) Collective climate action: when do people turn into collective environmental agents? Curr Opin Psychol 42:114–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.05.001

Gibson JJ (1977) The theory of affordances. Hilldale

Gifford R (2011) The dragons of inaction: psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am Psychol 66:290–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023566

Gigerenzer G (2015) On the supposed evidence for libertarian paternalism. Rev Philos Psychol 6:361–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-015-0248-1

Gillebaart M, Blom S, De Boer F, De Ridder DTD (2023) Prompting vegetable purchases in the supermarket by an affordance nudge: examining effectiveness and appreciation in a set of field experiments. Appetite 184:106526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.106526

Gold N, Lin Y, Ashcroft R, Osman M (2023) Better off, as judged by themselves’: do people support nudges as a method to change their own behavior? Behav Publ Policy 7:25–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.6

Gootjes F, De Wit J, Kroese FM, Stok FM, De Ridder DTD (2024) Collective decision making and support for COVID-19 measures at campus: two studies examining community engagement with mitigation policies. https://osf.io/95vrb/?view_only=a72931a2192346929282ea82ae36e681

Grelle S, Hofmann W (2024) When and why do people accept public-policy interventions? An integrative public-policy-acceptance framework. Persp Psychol Sci 19:258–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231180580

Grüne-Yanoff T (2012) Old wine in new casks: libertarian paternalism still violates liberal principles. Soc Choice Welf 38:635–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-011-0636-0

Hagman W, Andersson D, Västfjäll D, Tinghög G (2015) Public views on policies involving nudges. Rev Philos Psych 6:439–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-015-0263-2

Hamann KRS, Wullenkord M, Reese G, Van Zomeren M (2023) Believing that we can change our world for the better: a triple-A (Agent-Action-Aim) framework of self-efficacy beliefs in the context of collective social and ecological aims. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 28:11–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/10888683231178056

He G, Pan Y, Park A, Sawada Y, Tan ES (2023) Reducing single-use cutlery with green nudges: evidence from China’s food-delivery industry. Science 381:6662. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.add9884

Hertwig R (2017) When to consider boosting: some rules for policy-makers. Behav Publ Policy 1:143–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2016.14

Hertwig R, Grüne-Yanoff T (2017) Nudging and boosting: steering or empowering good decisions. Persp Psychol Sci 12:973–986. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617702496

Hofmann W (2024) Going beyond the individual level in self-control research. Nat Rev Psychol 3:56–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00256-y

Hollands G, Bignardi G, Johnston M, Kelly M, Ogilvie D, Petticrew M, Prestwich A, Shemilt I, Sutton S, Marteau T (2017) The TIPPME intervention typology for changing environments to change behaviour. Nat Hum Behav 1:0140. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0140

Junghans AF, Evers C, De Ridder DTD (2013) Eat me if you can: cognitive mechanisms underlying the distance effect. PLoS One 8:e84643. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084643

John P, Smith G, Stoker G (2009) Nudge nudge, think think. two strategies for changing civic behavior. Polit Quart 80:361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2009.02001.x

Keller PA, Harlam B, Loewenstein G, Volpp KG (2011) Enhanced active choice: a new method to motivate behavior change. J Cons Psychol 21:376–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.06.003

Keysers C, Gazzola V (2014) Dissociating the ability and propensity for empathy. Trends Cogn Sci 18:163–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.12.011

Lades LK, Delaney L (2022) Nudge FORGOOD. Behav Publ Policy 6:75–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2019.53

Loewenstein G, Bryce C, Hagmann D, Rajpal S (2015) Warning: you are about to be nudged. Behav Sci Policy 1:35–42. https://doi.org/10.1353/bsp.2015.0000

Maas J, De Ridder DTD, De Vet E, De Wit JBF (2012) Do distant foods decrease intake? The effect of food accessibility on consumption. Psychol Hlth 27(S2):59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.565341

Marchiori DR, Adriaanse MA, De Ridder DTD (2017) Unresolved questions in nudging research: putting the psychology back in nudging. Soc Pers Psychol Comp 11:e12297. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12297

Marston C, Renedo A, Miles S (2020) Community participation is crucial in a pandemic. Lancet 395:1676–1678. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31054-0

McCrudden C, King J (2016) The dark side of nudging: The ethics, political economy, and law of libertarian paternalism. In: Choice architecture in democracies. Exploring the legitimacy of nudging. Nomos Publishing. pp. 75–139

Merkelbach I, Dewies M, Denktas S (2021) Committing to keep clean: Nudging complements standard policy measures to reduce illegal urban garbage disposal in a neighborhood with high levels of social cohesion. Front Psychol 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660410

Michael J, McEllin L, Felbe A (2020) Prosocial effects of coordination—what, how and why? Acta Psychol 207:103083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2020.103083

Michael J, Sebanz N, Knoblich G (2016) Observing joint action: coordination creates commitment. Cognition 157:106–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2016.08.024

Mols F, Haslam SA, Jetten J, Steffens NK (2015) Why a nudge is not enough: a social identity critique of governance by stealth. Eur J Polit Res 54:81–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12073

Moojen R, Gillebaart M, De Ridder DTD (2024) Co-creation through collaborative governance: realizing healthier and more sustainable neighborhood food environments. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FCWZU

Münscher R, Vetter M, Scheuerle T (2015) A review and taxonomy of choice architecture techniques. J Behav Dec Mak 29:511–524. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1897

Obradovich N, Guenther SM (2016) Collective responsibility amplifies mitigation behaviors. Clim Change 137:307–319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1670-9

OECD (2017) Behavioral insights and public policy. Lessons from around the world. OECD Publishing

Oliver A (2018a) Do unto others: on the importance of reciprocity in public administration. Am Rev Publ Admin 48:279–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074016686826

Oliver A (2018b) Nudges, shoves and budges: behavioural economic policy frameworks. Int J Health Plan Manag 33:272–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2419

Olson M (1965) The logic of collective action. Public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press

Ostrom E (2009) A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325:419–422. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172133

Paunov Y, Wänke M, Vogel T (2018) Transparency effects on policy compliance: Disclosing how defaults work can enhance their effectiveness. Behav Publ Policy 2:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2018.40

Pfattheicher S, Nockur L, Böhm R, Sassenrath C, Petersen M (2020) The emotional path to action: empathy promotes physical distancing and wearing of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Sci 31:1363–1373. 0.1177/0956797620964422

Poteete AR, Janssen M, Ostrom E (2010) Working together: collective action, the commons, and multiple methods in practice. Princeton University Press

Prentice D, Paluck EL (2020) Engineering social change using social norms: Lessons from the study of collective action. Curr Opin Psychol 35:138–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.06.012

Reijula S, Hertwig R (2020) Self-nudging and the citizen choice architect. Behav Publ Policy. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2020.5

Rose G (1981) Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. BMJ 282:1847–1851. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847

Sarabi S, Gillebaart M, De Ridder DTD (2024) Turning on the we-mode: a systematic review on joint action principles for promoting collective pro-environmental engagement. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/t6mjw

Sebanz N, Bekkering H, Knoblich G (2006) Joint action: bodies and minds moving together. Trends Cogn Sci 10:70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.009

Sebanz N, Knoblich G (2021) Progress in joint-action research. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 30:138–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420984425

Sher S, McKenzie CRM, Müller-Trede J, Leong L (2022) Rational choice in context. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 31:518–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214221120387

Sparkman G, Walton GM (2017) Dynamic norms promote sustainable behavior, even if it is counternormative. Psychol Sci 28:1663–1674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617719950

Steffel M, Williams EF, Pogacar R (2016) Ethically deployed defaults: transparency and consumer protection through disclosure and preference articulation. J Mark Res 53:865–880. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0421

Sunstein CR (2016) People prefer System 2 nudges (kind of). Duke Law J 66:121–168. https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/dlj/vol66/iss1/3

Sunstein CR (2018) Better off, as judged by themselves’: a comment on evaluating nudges. Int Rev Econ 65:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-017-0280-9

Tannenbaum D, Fox CR, Rogers T (2017) On the misplaced politics of behavioral policy interventions. Nat Hum Behav 1:0130. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0130

Thaler RH, Sunstein CS (2008) Nudge. Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin Books

Thaler RH, Sunstein CS (2021) Nudge: The final edition. Improving decisions about money, health, and the environment. Penguin Books

Valenti SS, Gold JMM (1991) Social affordances and interaction I: Introduction. Ecol Psychol 3:77–98. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326969eco0302_2

Van Bavel JJ, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M, Willer R (2020) Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav 4:460–471. 0.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

Van der Linden S (2018) The future of behavioral insights: on the importance of socially situated nudges. Behav Publ Policy 2:207–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2018.22

Van Dessel P, Boddez Y, Hughes S (2022) Nudging societally relevant behavior by promoting cognitive inferences. Sci Rep. 12:9201. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12964-1

Van Gestel LC, Adriaanse MA, De Ridder DTD (2020) Do nudges make use of automatic processing? Unraveling the effects of a default nudge under type 1 and type 2 processing. Compr Res Soc Psychol 5:4–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743603.2020.1808456

Van Zomeren M, Postmes T, Spears R (2008) Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol Bull 134:504–535. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

Venema AG, Kroese FM, De Vet E, De Ridder DTD (2019) The one that I want: strong personal preferences render the center-stage nudge redundant. Food Qual Prefer 78:103744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.103744

Von Bieberstein F, Essl A, Friedrich K (2021) Empathy: a clue for prosocialty and driver of indirect reciprocity. PLoS One 16:e0255071. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255071

Wachner J, Adriaanse MA, De Ridder DTD (2020) The influence of nudge transparency on the experience of autonomy. Compr Res Soc Psychol 5:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743603.2020.1808782

Walton GM, Yeager DS (2020) Seed and soil: psychological affordances in contexts help to explain where wise interventions succeed or fail. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 29:219–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420904453

Weisz E, Ong DC, Carlson RW, Zaki J (2021) Building empathy through motivation-based interventions. Emotion 21:990–999. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000929

Wilkinson P (2013) Nudging and manipulation. Polit Stud 61:341–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00974.x

World Bank (2015) Mind, society and behavior. World Bank Group, Washington

Wright SC (2009) The next generation of collective action research. J Soc Issues 65:859–879. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-4560.2009.01628.X

Yeung K (2016) Hypernudge’: big data as a mode of regulation by design. Inf Commun Soc 20:118–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1186713

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DdR is the sole author of this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Ridder, D. Community nudges: why we need tools for turning on the we-mode to tackle problems that concern all of us. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 837 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05244-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05244-6