Abstract

Playfulness plays a pivotal role in fostering individual development across cognitive, emotional, and creative domains. This study aims to investigate parental playfulness and playfulness among 681 Chinese children aged 3–6 years, including 356 boys (52.3%) and 325 girls (47.7%), by utilizing the Adult Playfulness Scale, Child Playfulness Scale, and Chinese Parent-Child Interaction Scale via online parent-reported questionnaires. Hayes’ PROCESS (Model 4) with 5000 bootstrap samples was used to test the mediating role of parent-child interaction between parental playfulness and child playfulness. Findings indicated satisfactory levels of parental playfulness and child playfulness. Parental playfulness can significantly and positively predict the level of children’s playfulness, and concurrently, parent-child interaction serves as a partial mediator in the association between parental playfulness and children’s playfulness. The study underscores how parental playfulness not only directly influences child playfulness but also shapes it through parent-child interactions. Parents should adopt a scientific perspective and increase their understanding of playfulness. Improving the quality of parent-child interaction and creating playful interactive opportunities are crucial for fostering comprehensive child playfulness development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of playfulness, rooted in the term “play,” has been academically explored since the 1930s. Lieberman’s (2014) comprehensive and in-depth exploration of this concept in his work Playfulness: Its Relationship with Imagination and Creativity, initiated a wide research trend in the field. Playfulness is defined as the spontaneous personal traits or tendencies exhibited by individuals during play (Lieberman 2014). It is a positive psychological quality that not only brings joy to individuals but also stimulates flexible thinking, providing pleasurable experiences for oneself and others (Wu et al. 2019). Specifically, playfulness encompasses dimensions such as physical spontaneity, social spontaneity, cognitive spontaneity, explicit joy, and sense of humor, collectively forming the rich and complex essence of playfulness (Lieberman 1965).

Theoretical framework

In the broad landscape of individual development, playfulness plays a crucial role. It is a powerful psychological attribute that promotes cognitive, emotional, social, and physical development (Duss et al. 2023). The age bracket of 3–6 years is a critical period for children’s physical and mental development, during which their cognitive, emotional, social, and physical abilities are rapidly growing and changing. On the one hand, play, as their primary activity, brings them boundless joy and provides avenues for exploring the world and understanding themselves and others (Strasser et al. 2024). On the other hand, children of this age group exhibit higher levels of spontaneity and creativity through engaging in a wide range of play activities, such as imaginative play and role-playing games (Wu et al. 2024). They can mimic adult social behaviors through play, learning how to interact with others, resolve conflicts, and express their emotions and needs (Ata and Macun 2022; Fung and Chung 2023). These experiences invisibly exert significant influences on their social skills, emotional development, and cognitive abilities.

The microsystem theory emphasizes that the family environment is the most direct context for individual development and has profound effects on the development of children’s playfulness (Bureau et al. 2023). Within this theoretical framework, parents, as crucial environmental factors, not only provide a stage for children’s play through daily interactions but also implicitly convey the inherent value of playfulness through their own playful behaviors (Menashe-Grinberg and Atzaba-Poria 2017). Parent-child interaction, as a core pathway in this transmission process, not only has the potential to influence the level of children’s playfulness development but also shapes their long-term attitudes and behavioral patterns towards play.

This study focuses on children aged 3–6 years and aims to delve into the relationship between parental playfulness and children’s playfulness, as well as the underlying mechanisms influenced by parent-child interaction. The objective is to uncover how these factors jointly contribute to the development of children’s playfulness. Lastly, providing insightful guidance to enhance children’s playfulness.

Role of playfulness in individual development

Playfulness contributes significantly to individual development (Holmes and Hart 2022; Proyer et al. 2018). Firstly, playfulness is considered a personality trait closely associated with seeking pleasure, spontaneity, and uninhibitedness (Duss et al. 2023; Shen et al. 2014). Additionally, there is an overlap between playfulness and certain traits of the Big Five personality model, such as extraversion and emotional stability (Proyer 2017). Research also indicates a strong correlation between playfulness and specific personality traits, such as a sense of humor (Proyer 2014a). Secondly, playfulness plays multiple roles in individuals’ psychological well-being, including enhancing positive emotions, improving social interactions (Farley et al. 2021), increasing quality of life (Saliba and Barden 2021), regulating negative emotions (Chang et al. 2013), and alleviating stress (Magnuson and Barnett 2013; Proyer 2014b). As a positive psychological quality, playfulness can improve negative developmental outcomes, facilitate the formation of positive qualities, and achieve optimal functioning (Wu et al. 2019). Furthermore, playfulness has a positive impact on individuals’ cognitive styles and creativity (Duss et al. 2023; Prime et al. 2023). Studies demonstrate a positive relationship between playfulness and divergent thinking ability (Shen et al. 2014). Thus, playfulness has a positive influence on individuals’ personality traits, psychological well-being, and creativity.

The formation of playfulness in early childhood lays the foundation for future development. Firstly, the specific characteristics of concrete thinking and the predominant learning through play in early childhood determine its critical role in playfulness development (Delvecchio et al. 2016; Huang and He 2023; Vartiainen et al. 2024; Waldman-Levi et al. 2022). Secondly, research indicates that playfulness promotes the development of cognitive skills, social skills, and creativity in young children, making it an indispensable personality trait in their growth and development (Guadamud and Rosell 2024; Loukatari et al. 2019; Waldman-Levi et al. 2022). Children with a higher level of playfulness often exhibit extroverted personalities, positive attitudes, strong creativity, and good social skills, approaching life with a relaxed and enjoyable attitude (Chen and Fleer 2016; Singer 2013). Moreover, playfulness also has a protective function, helping children temporarily escape unpleasant environments and tense atmospheres, thus alleviating feelings of frustration and improving their current negative states to achieve optimal developmental outcomes (Della Rosa 2011). Even young children experiencing prolonged stress can enhance their resilience through increased playfulness, aiding in trauma recovery (Cohen et al. 2014). In conclusion, as a positive psychological quality that spans the entire lifespan, playfulness profoundly influences the early stages of individuals’ lives, teaching them how to live, experience life, and enjoy life (Guimarães and Ferreira 2022; Proyer 2013; Rossano et al. 2022). In this era filled with unknowns and challenges, there is a great need to cultivate and develop individuals with playfulness as a quality.

Relation between parental playfulness and child playfulness

Parental playfulness, as a positive inclination and attitude, influences the development of children’s playfulness (Choi and Young 2021; Shorer et al. 2021). A series of studies on child development have confirmed the significant impact of parental factors, such as parental playfulness, parental personality traits, and parenting styles, on the development of children’s playfulness (Cho and Ryu 2023; Fung and Chung 2022; Izzo et al. 2024; Kang and Lee 2011; Román-Oyola et al. 2018). Firstly, parental playfulness is characterized by active spontaneity, enjoyment, imaginative expression, and emotional richness displayed in work or daily life (Don et al. 2024; Lin and Li 2018; Shen et al. 2021). It not only reduces children’s negative emotions but also influences their behavior through various means, such as sensitivity, structure, and non-invasiveness (Menashe-Grinberg and Atzaba-Poria 2017; Oh and Lim 2018; Yılmaz and Erden 2022). Moreover, parents with higher levels of playfulness often exhibit high energy, and pleasant emotions, and can alleviate negative emotions such as boredom and tension in themselves and others (Proyer 2014c; Shorer et al. 2023; Tuber 2020). These parents perceive lower levels of stress and are inclined to adopt positive coping and proactive problem-solving strategies (Brauer et al. 2021; Magnuson and Barnett 2013). Although direct research on the relationship between parental playfulness and children’s playfulness is relatively limited, existing studies indirectly support the influence of parental playfulness on children’s playfulness. For instance, research indicates a positive correlation between parental playfulness and children’s adaptive behavior (Shen et al. 2017), and parental playfulness can alleviate children’s negative emotions (Shorer et al. 2023).

Relations among parent-child interaction, parental playfulness and child playfulness

Parent-child interaction is one of the primary ways through which young children engage in imitative learning (Bradley et al. 2015). On the one hand, according to the perspective of social learning theory, many of the behaviors acquired during the infancy and toddler stages result from observing and imitating parental behaviors (Csima et al. 2024; Guo and Zhang 2022; Gweon 2021; Over and Carpenter 2012). The playful ideas and behaviors of parents, through daily interactions and exchanges with their children, become incorporated into the children’s sense of self. In this way, children learn the behavioral attitudes and patterns of engagement in activities exhibited by their parents (Menashe-Grinberg and Atzaba-Poria 2017; Sitorus and Nurhafizah 2023). Additionally, based on the theory of self-expansion, individuals’ self-expansion is largely achieved through intimate relationships (Aron et al. 2022; Hughes et al. 2023). In the context of daily life and interactions, physical contact and emotional expressions such as hugging, kissing, and playing between parents and children are processes through which children incorporate their parents’ ideas and identifications into their own sense of self (Gao and Wang 2015; Pan 2023; Prime et al. 2023; Wong et al. 2022). The development of a strong parent-child relationship through ongoing interaction further promotes comprehensive development in various aspects of early childhood, including language, social skills, and cognition (Cao et al. 2023; Negrão et al. 2014; Rocha et al. 2020; Sitorus and Nurhafizah 2023; Stuart et al. 2021).

On the other hand, parental playfulness influences the quality of parent-child interaction (Lunkenheimer et al. 2020; Stafford et al. 2016). Research by Levavi et al. (2020) and other scholars indicates that parental playfulness is a key measure of the quality of parent-child play interaction. The higher the level of parental playfulness, the more frequent and higher quality the interactions between parents and children (Wu et al. 2024). Furthermore, the impact of parental playfulness on the quality of parent-child interaction extends to multiple dimensions, including children’s emotional regulation (Shorer et al. 2021), psychosocial adjustment (Shorer et al. 2023), playfulness, long-term happiness, and social adaptability (Choi and Young 2021). Although previous studies have recognized the role of parental playfulness as a critical influencing factor in parent-child interaction, few have considered family parent-child interaction as a process factor and explored its mediating role between parental playfulness and children’s playfulness.

The current study

In general, there is currently a considerable amount of research on the development of individual playfulness, but there is a relative lack of specific exploration into the development of playfulness during the crucial developmental stage of early childhood. The period from ages 3–6 is a critical time of rapid physical and mental development for individuals. Playfulness is not only a natural expression of children’s temperament during this age range but also an important avenue for their physical development, cognitive growth, and the cultivation of emotional and social skills (Ata and Macun 2022; Della Rosa 2011; Fung and Chung 2023). Therefore, it is necessary to conduct more in-depth research on the relevant variables and mechanisms that influence the development of playfulness in young children.

Based on this background, this study focuses on exploring the relationship between parental playfulness and children’s playfulness, with a particular emphasis on investigating the mediating role of parent-child interaction in this relationship, aiming to provide targeted educational recommendations and guidance strategies for the cultivation and enhancement of children’s playfulness. Therefore, this study proposes Hypothesis 1: Parental playfulness significantly and positively predicts children’s playfulness and Hypothesis 2: Parent-child interaction mediates the relationship between parental playfulness and children’s playfulness.

Methods

Participants and procedures

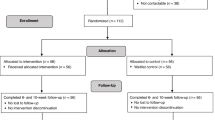

This study employed a convenience sampling method to select 3–6-year-old preschool children and their parents as participants within the geographical scope of China. Regarding sample characteristics, among the preschool children, there were 356 boys (52.3%) and 325 girls (47.7%). Table 1 provides detailed demographic information of the participants.

To ensure the ethical and legal aspects of the study, a series of ethical procedures were strictly adhered to during the questionnaire design and distribution process. Firstly, the researchers designed the research protocol and survey questionnaire according to the study’s objectives and submitted them for review to the institutional ethics committee, obtaining approval. Subsequently, data were collected mainly through online self-reporting by parents, based on the principles of convenience and wide accessibility. Parents assessed the children by following the guidelines and conducted other relevant assessments based on the children’s basic information. The questionnaire began with an instructive statement, clearly informing participants of the study’s purpose, content, data usage, and rights and obligations. Participants were required to fully understand and agree to these terms before proceeding with the questionnaire, thereby obtaining their informed consent.

A total of 836 questionnaires were collected in this study. Data security and confidentiality were ensured through encrypted transmission and storage, as well as strict limitations on the use of data. During the data collection phase, rigorous quality control measures were applied based on the following exclusion criteria: first, questionnaires with clearly patterned responses; second, total response time below 240 s (In the pre-test phase of the questionnaire, it was found that the fastest time to seriously complete all items in the questionnaire was 4 min); third, children outside the age range of 36–72 months; fourth, multiple responses from the same IP address. After screening, 681 valid questionnaires were obtained, resulting in an effective response rate of 81.46%.

Measures

Parental Playfulness Scale

The evaluation of parental playfulness in this study utilized the Adult Playfulness Scale (APS), developed by Yu et al. (2003), scholars from Taiwan, China. The short version of the scale consists of 29 items and encompasses six dimensions: enjoyment, creativity and problem-solving, relaxation and ease of expression, humor and amusement, childlike curiosity and fun, and perseverance and active engagement. The Likert five-point scoring system was employed, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” with values assigned from 1 to 5 accordingly. Higher scores indicate higher levels of playfulness in the participants. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.956, with alpha coefficients for each dimension ranging from 0.767 to 0.906, indicating good reliability. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) yielded satisfactory results, with the fit indices for the scale model as follows: χ²/df = 3.309, RMR = 0.041, NFI = 0.910, CFI = 0.935, IFI = 0.935, TLI = 0.925, and RMSEA = 0.059. These results demonstrate a good fit between the model and the observed data, indicating sound structural validity for the scale.

Child Playfulness Scale

The evaluation of child playfulness in this study utilized the Child Playfulness Scale (CPS) developed by Barnett (1990). The scale consists of 23 items encompassing five dimensions: physical spontaneity, social spontaneity, cognitive spontaneity, manifest pleasure, and a sense of humor. Scoring was conducted on a five-point scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” with values assigned from 1 to 5 accordingly. Higher scores indicate higher levels of playfulness in children. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.893, with alpha coefficients for each dimension ranging from 0.628 to 0.832, indicating reliable questionnaire reliability. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) yielded satisfactory results, with the fit indices for the three-factor model as follows: χ²/df = 5.186, GFI = 0.855, CFI = 0.880, IFI = 0.881, NFI = 0.856, TLI = 0.860, and RMSEA = 0.078. These results demonstrate good structural validity for the scale.

Chinese Parent-Child Interaction Scale

In this study, the evaluation of parent-child interaction levels drew upon the Chinese Parent-Child Interaction Scale (CPCIS), originally developed by Ip et al. (2018). The revised version of the scale, adjusted and modified by Chinese scholars Wu et al. (2020), was ultimately used to assess parent-child interaction. The revised scale consists of 12 items, encompassing four dimensions: knowledge learning, story reading, recreational activities, and environmental interaction. A five-point scoring system was employed, with increasing values from 1 to 5 indicating the frequency and level of parent-child interaction (1 representing “not at all,” 2 representing “once a week,” 3 representing “2–3 times a week,” 4 representing “4–5 times a week,” and 5 representing “6 times a week or more”). Higher scores indicate higher frequencies and levels of parent-child interaction. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale in this study was 0.881, with alpha coefficients for each dimension ranging from 0.612 to 0.838, indicating good reliability. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) yielded satisfactory results, with the fit indices for the three-factor model as follows: χ²/df = 3.588, RMR = 0.040, GFI = 959, NFI = 0.950, CFI = 0.963, TLI = 0.949, IFI = 0.963, and RMSEA = 0.062. These results demonstrate good structural validity for the scale.

Examination of common method bias

This study utilized convenience sampling and self-report measures to collect data, which may introduce common method biases. To mitigate this potential bias, the following methods were employed. Firstly, to avoid bias associated with convenience sampling, the questionnaires were distributed through multiple channels (e.g., social media platforms, and WeChat groups of parents from different provinces and cities) to ensure sample diversity and representativeness. Secondly, procedural controls were implemented to protect respondent anonymity and minimize guessing of measurement items, thus partially controlling for common method biases (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Participants were instructed to read the guidelines emphasizing the confidentiality of personal information and the academic research purpose of the survey before deciding whether to complete it, thus achieving procedural control. Additionally, during the data collection process, certain items were reverse-scored to control for measurement procedures (Zhou and Long 2004). Finally, Harman’s single-factor analysis was conducted as a statistical control to examine the presence of significant common method bias effects. The results revealed 11 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, with the largest factor explaining 27.79% of the variance. This value is below the critical threshold of 40%, indicating the absence of substantial common method bias in this study (Tang and Wen 2020).

Statistical analysis

This study employed AMOS software for conducting confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Descriptive statistical methods, including means and standard deviations, were utilized to analyze the overall characteristics of parental playfulness, child playfulness, and parent-child interaction. Independent samples t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to explore differences in core variable scores based on demographic variables. To ensure the validity and scientific rigor of the research findings, partial correlation analysis was performed, controlling for demographic variables such as child age and whether the child was an only child, to examine the relationships among the core variables. Finally, the mediation model was tested using the Bootstrap method in Hayes’ PROCESS in SPSS28.0 to validate Hypothesis 1 and 2 of this study, which posit a positive influence of parental playfulness on child playfulness and the mediating role of parent-child interaction between the two.

Results

Status of parental playfulness, child playfulness, and parent-child interaction and analysis of differences based on demographic variables

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the three core variables: parental playfulness, child playfulness, and parent-child interaction. The average score for parental playfulness was 3.279 (SD = 0.772), for parent-child interaction was 2.568 (SD = 0.670), and for child playfulness was 3.448 (SD = 0.586). Specifically, both parental playfulness and child playfulness scores were higher than the theoretical mean of 3, while the score for parent-child interaction was lower than the theoretical mean. These findings indicate that the parental and child playfulness levels in the sample population of this study were above average, while the parent-child interaction showed room for improvement. The specific scores for each dimension of child playfulness are shown in Table 2. The scores for physical spontaneity were 3.705 (SD = 0.748), social spontaneity was 3.481 (SD = 0.750), cognitive spontaneity was 3.202 (SD = 0.667), manifest pleasure was 3.809 (SD = 0.800), and humor was 3.046 (SD = 0.721). Among these, manifest pleasure, physical spontaneity, and social spontaneity had higher scores, while cognitive spontaneity and humor were relatively lower.

Independent samples t-tests and one-way ANOVA were conducted to examine the differences in demographic variables (child gender, age, and only child status) in relation to parental playfulness, child playfulness, and parent-child interaction (see Table 3). Based on child gender, there were no significant differences in parental playfulness, parent-child interaction, and child playfulness. However, significant differences emerged when considering the only child status. Specifically, only children scored significantly higher than non-only children in parental playfulness (p < 0.01), parent-child interaction (p < 0.05), and child playfulness (p < 0.01). This finding highlights the importance of the number of children in the family, which significantly influences the levels of parental and child playfulness and the level of parent-child interaction. Future research should further investigate the unique needs and dynamics of playfulness development in families with young siblings. Regarding child age, there were statistically significant differences in parental playfulness and parent-child interaction (p < 0.01). Post hoc comparisons revealed that parents of 3–4-year-old children scored significantly higher in parental playfulness and parent-child interaction compared to parents of 4–5-year-old children. This result reflects the influence of child developmental stages on parental playfulness and parent-child interaction, suggesting that as children grow older, parents may gradually reduce their play and interaction time with their children, and their level of playfulness may also decrease accordingly.

Correlation analysis of parental playfulness, child playfulness, and parent-child interaction

Based on the results of the difference analysis regarding demographic variables, a partial correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among parental playfulness, parent-child interaction, and child playfulness, while controlling for demographic variables such as child age and only child status. The specific results are presented in Table 4.

There was a significant positive correlation between parental playfulness and child playfulness at an overall level (r = 0.481, p < 0.001). Specifically, parental playfulness showed significant positive correlations with physical spontaneity (r = 0.320, p < 0.001), social spontaneity (r = 0.430, p < 0.001), cognitive spontaneity (r = 0.379, p < 0.001), manifest pleasure (r = 0.409, p < 0.001), and humor (r = 0.351, p < 0.001). Similarly, parent-child interaction exhibited a significant positive correlation with child playfulness at an overall level (r = 0.328, p < 0.001). Additionally, parent-child interaction showed significant positive correlations with physical spontaneity (r = 0.262, p < 0.001), social spontaneity (r = 0.282, p < 0.001), cognitive spontaneity (r = 0.285, p < 0.001), manifest pleasure (r = 0.235, p < 0.001), and humor (r = 0.240, p < 0.001). These findings provide a statistical basis for further exploration of the relationships among the three variables.

Mediation analysis of parent-child interaction between parental playfulness and child playfulness

Controlling for demographic variables such as child age and only child status, the mediating role of parent-child interaction in the relationship between parental playfulness and child playfulness was assessed using the Process software. The mediated model was examined using a bootstrapping method with 5000 samples. The results are presented in Table 5.

The mediation analysis revealed a significant positive effect of parental playfulness on child playfulness (β = 0.484, t = 14.284, p < 0.001). The effect size indicated that for every one-unit increase in parental playfulness, child playfulness would correspondingly increase by 0.484 units. This highlights the strong promoting effect of parental playfulness on child playfulness and supports hypothesis 1. Additionally, parental playfulness had a significant positive effect on parent-child interaction (β = 0.242, t = 6.449, p < 0.001), indicating that higher levels of parental playfulness were associated with more frequent and higher-quality parent-child interactions. Parent-child interaction also had a significant positive effect on child playfulness (β = 0.244, t = 6.673, p < 0.001), suggesting that higher levels of parent-child interaction were associated with better development of child playfulness. These findings underscore the important predictive roles of parental playfulness and parent-child interaction in child playfulness, emphasizing that parental playfulness and the interactive patterns between parents and children are key factors influencing the development of child playfulness. Furthermore, even after including parent-child interaction in the regression equation, the predictive effect of parental playfulness on child playfulness remained significant (β = 0.430, t = 12.697, p < 0.001), although the effect size was slightly reduced.

Specifically, the mediation analysis of parent-child interaction in the relationship between parental playfulness and child playfulness is presented in Table 6. The results indicated a mediation effect of 0.055 with a 95% confidence interval of [0.032, 0.081], excluding zero. This confirms the significant mediation effect (p < 0.05) of parent-child interaction in the relationship between parental playfulness and child playfulness, supporting research hypothesis 2. The direct effect of parental playfulness on child playfulness was 0.431 with a 95% confidence interval of [0.354, 0.506], excluding zero, indicating a significant direct effect (p < 0.001) that accounted for 88.68% of the total effect. The proportion of the mediation effect was 11.32%, suggesting that 11.32% of the influence of parental playfulness on child playfulness was achieved through the mediating variable of parent-child interaction. In conclusion, parent-child interaction partially mediates the relationship between parental playfulness and child playfulness, further revealing the mechanisms and pathways through which parental playfulness influences the level of child playfulness.

Discussion

Status of parental playfulness, parent-child interaction, and child playfulness

The results of this study indicate that the overall score of parental playfulness surpass the theoretical mean score of 3 points. This finding is consistent with Cao’s research (2010). In this study, the majority of parents demonstrated elevated levels of playfulness, exhibiting positive psychological states such as autonomy, emotional well-being, creativity, and imagination in their daily lives and work. Building upon such positive emotional foundations, parents could consistently engage with their children in playful ways, structuring everyday life situations and enjoying fun activities together (Stafford et al. 2016; Lunkenheimer et al. 2020). Moreover, when faced with challenges or conflicts in parent-child interactions, they displayed flexibility, humor, and creativity in problem-solving approaches (Shorer et al. 2021).

In this study, the overall score of parent-child interaction falls slightly below the theoretical mean of 3 points. It is evident that in this study, the majority of surveyed parent-child dyads exhibit low frequency and quality of interaction. This situation aligns with previous findings on parent-child interaction (Ding et al. 2021). As one of the key pathways to achieving early childhood education goals, parent-child interaction plays a crucial role in promoting the holistic development of children’s physical and mental well-being (Cao et al. 2023). Given the current status of parent-child interaction, the lack of frequent and high-quality interactions has become a prevalent issue in contemporary parenting practices (Griffith and Arnold 2019). This deficiency is influenced by various internal and external factors, such as the widespread use of touchscreen media in the digital age (Wong et al. 2020), parental educational beliefs, and parenting styles (Wu et al. 2020).

The results of this study indicate that the overall score and scores across various dimensions of the children’s playfulness are above the midpoint of 3, positioning them at a slightly above-average level. Particularly, scores for “physical spontaneity” and “manifest pleasure” are relatively high, while scores for “sense of humor” and “cognitive spontaneity” are lower. This can be primarily attributed to the fact that play, as the primary form of activity for preschoolers, often carries significant enjoyment characteristics, energizing children and making them feel happy and excited (Delvecchio et al. 2016). Moreover, during play, the diverse interactions with peers can bring about varied emotional changes in children (Chen and Fleer 2016; Diebold and Perren 2022). These dynamics are frequently observed in kindergarten activities, children consistently exhibit high energy levels and enthusiasm, engaging in continuous conversations, laughter, games, and sharing experiences with their peers (Rossano et al. 2022). On the other hand, the aspects of “cognitive spontaneity” and “sense of humor” within children’s playfulness are somewhat lacking. This deficiency may stem from children being in the later stages of the preoperational period, where they possess concrete operational thinking but have not yet fully developed the abstract, comprehensive, and logical aspects of thinking (Huang and He 2023; Prime et al. 2023). Consequently, the characteristics of cognitive spontaneity and sense of humor may not be as pronounced.

The influence of parental playfulness on child playfulness

The results of this study indicate that parental playfulness significantly and positively predicts the level of playfulness in young children, meaning that the higher the level of parental playfulness, the higher the level of children’s playfulness. This outcome confirms hypothesis 1 and is consistent with conclusions from existing related research (Bureau et al. 2023; Wu et al. 2024). Based on these findings, parental playfulness deserves attention.

According to social learning theory, individuals’ social behaviors stem from direct learning and imitation of individuals in their immediate environment (Gweon 2021; Over and Carpenter 2012). The behaviors and habits resulting from parents’ cognition of playfulness serve as examples and demonstrations for children, influencing the development of children’s playfulness (Román-Oyola et al. 2018). Adults’ playfulness extends beyond the realm of games into daily life, impacting how they perceive, evaluate, and handle situations (Guimarães and Ferreira 2022; Proyer 2013). Thus, parents who enjoy playing games not only have a liking for games but also actively perceive the significance of playfulness, making them more likely to encourage children to play. Additionally, playful parents are more likely to exhibit characteristics such as being entertaining, humorous, adventurous, and imaginative in their daily lives and play (Wu et al. 2024). These attributes have a positive impact on children’s spontaneous cognitive play and sense of humor (Oh and Lim 2018; Yılmaz and Erden 2022).

The mediating role of parent-child interaction in the relation between parental playfulness and child playfulness

The findings of this study further corroborate hypothesis 2, elucidating the dual pathways through which parental playfulness and parent-child interaction jointly influence children’s playfulness. Specifically, parental playfulness not only directly affects the development of children’s playfulness but also indirectly impacts it through the mediating role of parent-child interaction.

Firstly, parental playfulness significantly predicts the level of parent-child interaction, aligning with previous research findings (Menashe-Grinberg and Atzaba-Poria 2017). This result also confirms the spillover effect posited by family systems theory: higher levels of parental playfulness are often accompanied by more positive emotional experiences (Don et al. 2024). These experiences translate into greater positivity in interactions and interpersonal relationships, which, when transferred to the parent-child system, effectively enhance the frequency and quality of parent-child interactions (Bureau et al. 2023). Furthermore, parents with higher levels of playfulness tend to adopt a positive attitude towards their children’s behavior (Wu et al. 2024). Even when facing conflicts, they humorously resolve them, thereby fostering a healthy parent-child relationship (Brauer et al. 2021). Conversely, parents with lower levels of playfulness are less likely to respect their children’s opinions and more likely to handle issues negatively, often through criticism, leading to increased parent-child conflicts (Shorer et al. 2021).

Secondly, parent-child interaction positively predicts the level of children’s playfulness. This finding aligns with the research results of Hyun et al. (2020). According to ecological systems theory, parents are significant social figures in a child’s environment, and high-quality parent-child interactions positively impact various aspects of a child’s development (Negrão et al. 2014; Stuart et al. 2021). Attachment theory suggests that close parent-child relationships can enhance a child’s curiosity, confidence, and courage to explore new things (Rocha et al. 2020). Parents with high levels of playfulness often create a relaxed atmosphere and express positive emotions during interactions with their children, making the interaction process enjoyable. This environment is conducive to the child’s positive emotional regulation and the effective development of their socio-emotional skills (Bureau et al. 2023; Oh and Lim 2018). Additionally, the closer the parent-child relationship, the more support parents provide for their children’s physical activities, which helps in developing both gross and fine motor skills (Gao and Wang 2015; Wong et al. 2022). Playful parent-child interactions significantly promote the child’s physical coordination and balance (Pan 2023). Therefore, effective parent-child interactions contribute to various developmental areas in children, including social interactions, motor skills, communication, and emotional experiences (Cao et al. 2023). These developmental areas are closely associated with the social spontaneity, physical spontaneity, and manifest pleasure aspects of playfulness, ultimately enhancing the overall playfulness level of children (Duss et al. 2023).

Finally, parent-child interaction serves as a partial mediator between parental playfulness and children’s playfulness, indicating that parental playfulness indirectly affects the development of children’s playfulness through parent-child interaction. From a social-cognitive perspective, play serves as a schema for parent-child interaction, significantly influencing child development (Guadamud and Rosell 2024). Specifically, playful parents tend to create a safe and conducive play environment during interactions, providing continuous and varied stimuli to meet the developmental needs of children’s playfulness (Tuber 2020). On one hand, these parents often act as guides, offering support and encouragement to their children, fostering free exploration during play (Shorer et al. 2021, 2023). On the other hand, they also participate as co-players, helping children experience joy during play, and subtly teaching values such as fair competition and respect through collaborative play roles (Choi and Young 2021; Wu et al. 2024). Furthermore, in everyday life, such parents frequently design enjoyable and engaging scenarios to interact with their children (Lin and Li 2018; Sitorus and Nurhafizah 2023). This indicates that when parents incorporate high levels of playfulness into parent-child interactions, both parties can actively engage, fostering trust and emotional sharing. Parents can provide more security and confidence to their children through close parent-child relationships, enabling children to be more focused and enthusiastic about play activities, ultimately enhancing their level of playfulness (Izzo et al. 2024; Shorer et al. 2021).

Conclusions and practical implications

This study indicates that parental playfulness and children’s playfulness are generally in good condition, whereas the level of parent-child interaction is relatively low. A significant positive correlation exists between parental playfulness and children’s playfulness, suggesting that the higher the parental playfulness, the better the development of children’s playfulness. Furthermore, parent-child interaction serves as a partial mediator between parental playfulness and children’s playfulness, implying that parents’ playfulness not only directly influences children’s playfulness but also further affects the level of children’s playfulness through parent-child interaction. Considering the research outcomes, the following two suggestions are proposed.

Establishing a scientific perspective on play and recognizing the valuable role of playfulness

Playfulness, as a positive psychological quality, profoundly influences the comprehensive development of young children by encompassing elements such as emotional well-being, flexible thinking, and imaginative creativity. Actively nurturing children’s playfulness becomes particularly important in enabling them to enjoy life in a society filled with tension and pressure. This study highlights the significant role of parental playfulness in the development of children’s playfulness. Therefore, it is essential for parents to establish a correct and scientific understanding of playfulness, enhance their learning and comprehension of adult playfulness knowledge, develop an accurate self-awareness of their own personality traits and behavioral habits, and liberate their attitudes and behaviors towards playfulness to manifest its inherent value.

Furthermore, society can promote these efforts through channels such as social media, employing multiple approaches to help the parent community gain in-depth knowledge about playfulness-related topics. This active reinforcement of parents’ cognitive awareness of playfulness assists them in subjectively acknowledging and consciously cultivating their own playfulness. Consequently, this creates favorable conditions and a positive and enjoyable atmosphere for the development of children’s playfulness.

Improving the quality of family parent-child interaction to promote child playfulness

Active and frequent parent-child interaction is beneficial for promoting the early growth and development of children, and it serves as an important pathway through which parental playfulness influences children’s playfulness. On one hand, parents should engage in cooperative parenting and establish a close and harmonious parent-child relationship, jointly leveraging parent-child interaction to promote children’s playfulness. The cooperative parenting and parent-child relationship exhibit a spillover effect, whereby when parents receive support and assistance from their partners in the parenting process, they experience positive parenting emotions. These emotions transfer to the parent-child system, fostering warmth and intimacy between parents and children. The positive cooperation among parents not only provides a warm and harmonious family atmosphere for children but also offers opportunities for children to observe, learn, and internalize positive behavior.

On the other hand, parents should actively participate in interactions and create an environment conducive to the development of children’s playfulness. Children’s playfulness can be weakened or strengthened through social, cultural, and family environments, and parents play a crucial role in creating living and play environments. Therefore, parents should design family games and interactive activities that align with children’s interests, are imaginative, and have a strong sense of playfulness. These activities comprehensively stimulate children’s physiological senses, provide opportunities for firsthand experiences and sensations, and ignite and cultivate children’s playfulness. Additionally, parent-child interaction is mutually reinforcing, so parents should take the initiative in initiating parent-child interactions, manage their time spent with children effectively, and enhance the quality of parent-child interaction in terms of content and approach. This, in turn, supports the development of children’s playfulness.

Limitations and future prospects

This study has further revealed the influence of parental playfulness on children’s playfulness and the mediating role of parent-child interaction, providing empirical evidence for educators and parents to promote the development of children’s playfulness. However, several valuable issues require further exploration.

Firstly, this study employed a cross-sectional design, focusing mainly on parental playfulness, children’s playfulness, and parent-child interaction at a specific point in time, which cannot reveal the temporal trends of these variables. Future research could combine cross-sectional and longitudinal tracking studies of children’s playfulness to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the age characteristics and patterns of children’s playfulness development, thereby capturing the dynamic process of playfulness development more effectively.

Secondly, the investigation of playfulness in this study relied on self-report questionnaires completed by parents, which may introduce some biases in how parents perceive and report their children’s playfulness. Therefore, future research could consider developing and utilizing more precise tools for children’s self-report or direct measurement of their playfulness. Another approach could involve both mothers and fathers using a mutual evaluation method to assess each other’s playfulness, thus obtaining more accurate data.

Thirdly, there exist cultural differences between Eastern and Western societies in the study of playfulness. Variances in cultural values, educational philosophies, and family structures may lead to differences in parents’ understanding and attitudes toward children’s playfulness development. Therefore, future research could delve deeper into the mechanisms of children’s playfulness development in different cultural backgrounds to better comprehend the diversity and commonalities of playfulness on a global scale, ultimately promoting the healthy development of children’s playfulness in various cultural contexts.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aron A, Lewandowski G, Branand B, Mashek D, Aron E (2022) Self-expansion motivation and inclusion of others in self: an updated review. J Soc Personal Relatsh 39(12):3821–3852. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075221110630

Ata S, Macun B (2022) Play tendency and prosociality in early childhood. Early Child Dev Care 192(13):2087–2098. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2021.1988943

Barnett LA (1990) Playfulness: definition, design, and measurement. Play Cult 3(4):319–336

Bradley RH, Pennar A, Iida M (2015) Ebb and flow in parent-child interactions: shifts from early through middle childhood. Parent Sci Pract 15(4):295–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2015.1065120

Brauer K, Proyer RT, Chick G (2021) Adult playfulness: an update on an understudied individual differences variable and its role in romantic life. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 15(4):e12589. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12589

Bureau JF, Bandk K, Deneault AA, Turgeon J, Seal H, Brosseau-Liard P (2023) The PPSQ: assessing parental, child, and partner’s playfulness in the preschool and early school years. Front Psychol 14:1274160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1274160

Cao Q (2010) Research on the correlation between father’s playfulness and parent-child interaction. Dissertation, Nanjing Normal University. https://doi.org/10.7666/d.y1728110

Cao H, Yan SQ, Guan HY (2023) Influence of parent-child interaction on early childhood development outcome. Chin J Child Health Care 31(7):770–774. https://doi.org/10.11852/zgetbjzz2022-0811

Chang PJ, Qian X, Yarnal C (2013) Using playfulness to cope with psychological stress: taking into account both positive and negative emotions. Int J Play 2(3):273–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2013.855414

Chen F, Fleer M (2016) A cultural-historical reading of how play is used in families as a tool for supporting children’s emotional development in everyday life. Eur Early Child Educ Res J 24(2):305–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2016.1143268

Cho HY, Ryu J (2023) Effects of Korean fathers’ participation in parenting, parental role satisfaction, and parenting stress on their child’s playfulness. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 33(4):490–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2022.2072038

Choi Y, Young LJ (2021) Structural relationship among parent’s play participation, young children’s playfulness, self-regulation and happiness. Fam Environ Res 59(1):71–82. https://doi.org/10.6115/fer.2021.006

Cohen E, Pat-Horenczyk R, Haar-Shamir D (2014) Making room for play: an innovative intervention for toddlers and families under rocket fire. Clin Soc Work J 42(4):336–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-013-0439-0

Csima M, Podráczky J, Keresztes V, Soós E, Fináncz J (2024) The role of parental health literacy in establishing health-promoting habits in early childhood. Children 11(5):576. https://doi.org/10.3390/CHILDREN11050576

Della Rosa E (2011) The creative role of playfulness in development. Infant Observ 14(2):203–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698036.2011.583436

Delvecchio E, Li JB, Pazzagli C, Lis A, Mazzeschi C (2016) How do you play? A comparison among children aged 4-10. Front Psychol 7:1833. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01833

Diebold T, Perren S (2022) Toddlers’ peer engagement in Swiss childcare: contribution of individual and contextual characteristics. Eur J Psychol Educ 37(3):627–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10212-021-00552-2

Ding Q, Song ZM, Yuan XL (2021) A study on quality and influencing factors of parent-child interaction in rural infant families-based on observation and evaluation of 90 families. J Shaanxi Xueqian Norm Univ 37(9):1–6. [in Chinese]

Don BP, Simpson JA, Fredrickson BL, Algoe SB (2024) Interparental positivity spillover theory: how parents’ positive relational interactions influence children. Perspect Psychol Sci 17456916231220626. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231220626

Duss I, Rudisuli C, Wustmann Seiler C, Lannen P (2023) Playfulness from children’s perspectives: development and validation of the Children’s Playfulness Scale as a self-report instrument for children from 3 years of age. Front Psychol 14:1287274. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1287274

Farley A, Kennedy-Behr A, Brown T (2021) An investigation into the relationship between playfulness and well-being in Australian adults: an exploratory study. Occup Ther J Res 41(1):56–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449220945311

Fung WK, Chung KKH (2022) Parental play supportiveness and kindergartners’ peer problems: children’s playfulness as a potential mediator. Soc Dev 31(4):1126–1137. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12603

Fung WK, Chung KKH (2023) Playfulness as the antecedent of kindergarten children’s prosocial skills and school readiness. Eur Early Child Educ Res J 31(5):797–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2023.2200018

Gao Y, Wang XL (2015) Effects of parental support, peer friendship quality on sport motivation and behavior. J Tianjin Univ Sport 30(6):480–486+519. https://doi.org/10.13297/j.cnki.issn1005-0000.2015.06.004

Griffith SF, Arnold DH (2019) Home learning in the new mobile age: parent–child interactions during joint play with educational apps in the US. J Child Media 13(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2018.1489866

Guadamud LAL, Rosell RCA (2024) Sistema de actividades lúdicas para fortalecer el desarrollo socioemocional en niños y niñas. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar 8(4):5474–5492. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v8i4.12763

Guimarães RS, Ferreira LG (2022) Conceptions of playfulness. What do Teach present theme?. Times Spaces Educ J 15(34):4. https://doi.org/10.20952/revtee.v15i34.17446

Guo SP, Zhang XB (2022) Re-evaluation of Bandura’s social learning theory: from the perspective of cultural psychology. Psychol Res 15(2):99–104. https://doi.org/10.19988/j.cnki.issn.2095-1159.2022.02.001

Gweon H (2021) Inferential social learning: cognitive foundations of human social learning and teaching. Trends Cogn Sci 25(10):896–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.07.008

Holmes R, Hart T (2022) Exploring the connection between adult playfulness and emotional intelligence. J Play Adulthood 4(1):28–51. https://doi.org/10.5920/jpa.973

Hughes EK, Slotter EB, Emery LF (2023) Expanding me, loving us: self-expansion preferences, experiences, and romantic relationship commitment. Self Identity 22(2):227–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2022.2074092

Huang J, He G (2023) Theorizing children’s play and its fissure of meaning: an examination based on a conceptual history approach. Stud Early Child Educ 12:1–13. https://doi.org/10.13861/j.cnki.sece.2023.12.001

Hyun G, ShinHee P, JiSeong B (2020) Mediating effects of parent-child interaction on the relation between children’s playfulness and socioemotional development. J Soc Humanit Stud East Asia 53:325–353. https://doi.org/10.52639/JEAH.2020.12.53.325

Ip P, Tso W, Rao N, Ho FKW, Chan KL, Fu KW, Li SL, Goh W, Wong WH, Chow CB (2018) Rasch validation of the Chinese parent–child interaction scale (CPCIS). World J Pediatr 14(3):238–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-018-0132-z

Izzo F, Saija E, Pallini S, Ioverno S, Baiocco R, Pistella J (2024) Happy moments between children and their parents: a multi-method and multi-informant perspective. J Happiness Stud 25(3):31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00735-w

Kang JH, Lee KN (2011) Effects of children’s individual variables and maternal parenting on children’s playfulness. Korean J Childcare Educ 7(2):159–180

Levavi K, Menashe-Grinberg A, Barak-Levy Y, Atzaba-Poria N (2020) The role of parental playfulness as a moderator reducing child behavioural problems among children with intellectual disability in Israel. Res Dev Disabil 107:103793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103793

Lieberman JN (1965) Playfulness and divergent thinking: an investigation of their relationship at the kindergarten level. J Genet Psychol 107(2):219–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.1965.10533661

Lieberman JN (2014) Playfulness: its relationship to imagination and creativity. Academic Press

Lin X, Li H (2018) Parents’ play beliefs and engagement in young children’s play at home. Eur Early Child Educ Res J 26(2):161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1441979

Loukatari P, Matsouka O, Papadimitriou K, Nani S, Grammatikopoulos V (2019) The effect of a structured playfulness program on social skills in kindergarten children. Int J Instr 12(3):237–252. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2019.12315a

Lunkenheimer E, Hamby CM, Lobo FM, Cole PM, Olson SL (2020) The role of dynamic, dyadic parent-child processes in parental socialization of emotion. Dev Psychol 56(3):566–577. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000808

Magnuson CD, Barnett LA (2013) The playful advantage: how playfulness enhances coping with stress. Leis Sci 35(2):129–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.761905

Menashe-Grinberg A, Atzaba-Poria N (2017) Mother-child and father-child play interaction: the importance of parental playfulness as a moderator of the links between parental behavior and child negativity. Infant Ment Health J 38(6):772–784. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21678

Negrão M, Pereira M, Soares I, Mesman J (2014) Enhancing positive parent-child interactions and family functioning in a poverty sample: a randomized control trial. Attach Hum Dev 16(4):315–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2014.912485

Oh J-H, Lim SH (2018) Influence of father’s and mother’s playfulness, empathic emotional reaction, and the child’s playfulness on the child’s emotional regulation: examining the mediated moderation effect. Korean J Child Stud 39(6):113–130. https://doi.org/10.5723/kjcs.2018.39.6.113

Over H, Carpenter M (2012) The social side of imitation. Child Dev Perspect 7(1):6–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12006

Pan Q (2023) Research on the design and implementation strategies of parent-child play for infants and toddlers aged 2-3 years. J Educ Educ Res 3(3):65–71. https://doi.org/10.54097/jeer.v3i3.9553

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Prime H, Andrews K, Markwell A, Gonzalez A, Janus M, Tricco AC, Bennett T, Atkinson L (2023) Positive parenting and early childhood cognition: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 26(2):362–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-022-00423-2

Proyer RT (2013) The well-being of playful adults: adult playfulness, subjective well-being, physical well-being, and the pursuit of enjoyable activities. Eur J Humour Res 1(1):84–98. https://doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2013.1.1.PROYER

Proyer RT (2014a) A psycho-linguistic approach for studying adult playfulness: a replication and extension toward relations with humor. J Psychol 148(6):717–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2013.826165

Proyer RT (2014b) Perceived functions of playfulness in adults: does it mobilize you at work, rest, and when being with others? Eur Rev Appl Psychol 64(5):241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2014.06.001

Proyer RT (2014c) To love and play: testing the association of adult playfulness with the relationship personality and relationship satisfaction. Curr Psychol 33(4):501–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9225-6

Proyer RT (2017) A multidisciplinary perspective on adult play and playfulness. Int J Play 6(3):241–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2017.1384307

Proyer RT, Gander F, Bertenshaw EJ, Brauer K (2018) The positive relationships of playfulness with indicators of health, activity, and physical fitness. Front Psychol 9:1440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01440

Rocha NACF, dos Santos Silva FP, dos Santos MM, Dusing SC (2020) Impact of mother-infant interaction on development during the first year of life: a systematic review. J Child Health Care 24(3):365–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493519864742

Román-Oyola R, Figueroa-Feliciano V, Torres-Martínez Y, Torres-Vélez J, Encarnación-Pizarro K, Fragoso-Pagán S, Torres-Colón L (2018) Play, playfulness, and self-efficacy: parental experiences with children on the autism spectrum. Occup Ther Int 2018:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4636780

Rossano F, Terwilliger J, Bangerter A, Genty E, Heesen R, Zuberbühler K (2022) How 2-and 4-year-old children coordinate social interactions with peers. Philos Trans R Soc B 377(1859):20210100. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0100

Saliba YC, Barden SM (2021) Playfulness and older adults: implications for quality of life. J Ment Health Couns 43(2):157–171. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.43.2.05

Shen X, Chick G, Pitas NA (2017) From playful parents to adaptable children: a structural equation model of the relationships between playfulness and adaptability among young adults and their parents. Int J Play 6(3):244–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2017.1382983

Shen X, Liu H, Song R (2021) Toward a culture-sensitive approach to playfulness research: development of the Adult Playfulness Trait Scale-Chinese version and an alternative measurement model. J Leis Res 52(4):401–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2020.1850193

Shen XS, Chick G, Zinn H (2014) Playfulness in adulthood as a personality trai. J Leis Res 46(1):58–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2014.11950313

Shorer M, Swissa O, Levavi P, Swissa A (2021) Parental playfulness and children’s emotional regulation: the mediating role of parents’ emotional regulation and the parent–child relationship. Early Child Dev Care 191(2):210–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1612385

Shorer M, Zilker N, Salomon A, Spiegelman N (2023) Parental playfulness as a mediator of the association between parents’ emotional difficulties and children’s psychosocial adjustment. Early Child Dev Care 193(9–10):1173–1187. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2023.2243395

Singer E (2013) Play and playfulness, basic features of early childhood education. Eur Early Child Educ Res J 21(2):172–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2013.789198

Sitorus NS, Nurhafizah N (2023) The influence of parenting styles on early childhood social skills. AL-ISHLAH J Pendidik 15(2):2367–2374. https://doi.org/10.35445/alishlah.v15i2.3737

Stafford M, Kuh DL, Gale CR, Mishra G, Richards M (2016) Parent-child relationships and offspring’s positive mental wellbeing from adolescence to early older age. J Posit Psychol 11(3):326–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1081971

Strasser K, Balladares J, Grau V, Marín A, Preiss DD, Jadue D (2024) Playfulness and the quality of classroom interactions in preschool. Learn Instr 93:101941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2024.101941

Stuart A, Canário C, Cruz O (2021) An evaluation of the quality of parent-child interactions in vulnerable families that are followed by child protective services: a latent profile analysis. Children 8(10):906. https://doi.org/10.3390/CHILDREN8100906

Tang DD, Wen ZL (2020) Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: problems and suggestions. J Psychol Sci 43(1):215–223. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200130

Tuber S (2020) There’s a place: how parents help their children create a capacity for playfulness and can it be sustained across the lifespan. J Infant Child Adolesc Psychother 19(2):115–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2020.1755191

Vartiainen J, Sormunen K, Kangas J (2024) Relationality of play and playfulness in early childhood sustainability education. Learn Instr 93:101963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2024.101963

Waldman-Levi A, Bundy A, Shai D (2022) Cognition mediates playfulness development in early childhood: a longitudinal study of typically developing children. Am J Occup Ther 76(5):7605205020. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2022.049120

Wong RS, Tung KTS, Rao N, Leung C, Hui ANN, Tso WWY, Fu KW, Jiang F, Zhao J, Ip P (2020) Parent technology use, parent–child interaction, child screen time, and child psychosocial problems among disadvantaged families. J Pediatr 226:258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.07.006

Wong TKY, Konishi C, Kong X (2022) A longitudinal perspective on frequency of parent-child activities and social-emotional development. Early Child Dev Care 192(3):458–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1765773

Wu Y, Lin T, Li W, Wang GH, Zhang YT, Zhao J, Zhu Q, Jiang YR, Jiang F (2020) Parent-child interaction and early childhood development of newly enrolled preschoolers in Shanghai kindergartens: a cross-sectional survey. Chin J Evid Based Pediatr 15(6):406–410

Wu A, Tian Y, Chen S, Cui L (2024) Do playful parents raise playful children? A mixed methods study to explore the impact of parental playfulness on children’s playfulness. Early Educ Dev 35(2):283–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2022.2148072

Wu A, Xu SS, Li D (2019) Playfulness: a psychological character that promotes children’s positive development. Stud Early Child Educ 6:25–34. https://doi.org/10.13861/j.cnki.sece.2019.06.003

Yılmaz B, Erden FT (2022) Exploring humour within the early childhood period from children’s and teachers’ perspectives. J Child Educ Soc 3(2):151–167. https://doi.org/10.37291/2717638X.202232168

Yu P, Wu JJ, Lin WW, Yang CH (2003) The development of Adult Playfulness Scale and Organizational Playfulness Climate Questionnaire. J Test 50(1):73–110

Zhou H, Long LR (2004) Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol Sci 6:942–950

Acknowledgements

We are particularly grateful for the assistance given by the Chongqing Early Childhood Education Quality Monitoring and Evaluation Research Center of Chongqing Normal University. This study was funded by Chongqing University Outstanding Talents Support Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YW, YL, DZ, TZ and XL contributed equally to the conceptualization, investigation, data collection and analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript together. YL and YW jointly supervised this study. YW contributed to the project administration and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. A committee review board of School of Educational Sciences of Chongqing Normal University approved this study on July 15 in 2021. An approval code was assigned as ECE-CQNU-2021071503 for this study. The scope of the approval included the purpose and content of this study, the investigating procedure and participants.

Informed consent

In the instructions of the questionnaire for this study, while collecting data from July 21 to November 10 in 2021, we have explicitly informed all participants that: (1) The survey is anonymous, ensuring the confidentiality of each participant; (2) The purpose and value of this research; (3) The collected data will be used solely for research purposes and analyzed at an aggregate level, without individual analysis of any participant’s data; (4) Participation in this questionnaire survey is voluntary, and respondents may withdraw their consent at any time.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Y., Lei, Y., Zhou, D. et al. Relation between parental playfulness and child playfulness: mediating role of parent-child interaction. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 861 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05253-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05253-5