Abstract

The advent of digitization of financial transactions has positioned the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) as a transformative, paperless and cashless digital payment system for consumers in India. Its user-friendly design, robust security features, and broad adoption across small businesses, roadside vendors, and unorganized sectors have established its dominance in facilitating daily digital payments in the Indian market. Over recent years, UPI usage has experienced exponential growth across India. This study examines the factors influencing the intention to adopt UPI with a focus on add-on services, perceived promotional benefits, and perceived trust with the integration of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). Employing the survey responses of 416 UPI users, this research applies partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to validate the hypothesized model developed for this study. The findings revealed that facilitating conditions, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, perceived promotional benefits, and perceived trust significantly influence the users’ intention to adopt UPI, which further influences its usage behavior. Interestingly, add-on services by UPI did not affect the intention of users to adopt UPI, questioning its role in UPI adoption. However, add-on services had a significant impact on performance expectancy and effort expectancy. Additionally, perceived promotional benefits impacted facilitating conditions for UPI usage. Demographic attributes further moderated these relationships: age and occupation significantly moderated the impact of performance expectancy on the intention to adopt UPI, while gender and income did not exhibit any profound moderating effects. The findings offer valuable insights for service providers and policymakers aiming to improve UPI adoption among consumers. Customized strategies considering demographic variations can optimize the platform’s accessibility and appeal to a broader audience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Post-COVID-19 pandemic, the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) has emerged as an innovative real-time digital payment system characterized by it “paperless and cashless” nature. This platform facilitates the instant transfer of funds between bank accounts, not only for peer-to-peer transactions but also for bill payments and merchant transactions conducted through smartphone devices (Jena, 2023; Jha & Kumar, 2020). UPI integrates multiple bank accounts under a single application using virtual payment addresses (VPA) as unique identifiers (Ranpariya et al., 2021; Tungare, 2019). This system is based on a “disruptive technology” framework (Vivek & Selvan, 2021) and has become a significant component of the Indian fintech industry (Rajeswari & Vijai, 2021). Such a ground-breaking approach was developed by the not-for-profit “National Payments Corporation of India” (NPCI) in 2016 and is regulated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) (Chawla et al., 2019). UPI has revolutionized the scenario of financial services in India (Priya & Anusha, 2019; Raghavendra & Veeresha, 2023), and it has positioned India as a global leader in digital payments by reshaping conventional payment systems (Dhivya et al., 2023). Its widespread adoption can be attributed to its user-friendly interface, robust security features, and widespread acceptance across various sectors, including small retailers, roadside vendors, and unorganized sectors (Chawla et al., 2019; Ligon et al., 2019; Sinha & Singh, 2023). However, certain prerequisites are essential for its adoption, such as having a bank account, a smartphone, access to the Internet, and technological literacy (Ligon et al., 2019). Key unique characteristics of UPI include seamless money transfer via mobile devices, initiation of payment by both payees and payers, and one-click, two-factor authentication (Gochhwal, 2017; Tungare, 2019). Unlike traditional Internet banking, UPI transactions are free for personal use, regardless of the transaction amount (Pal et al., 2023). Various applications support UPI transactions, with prominent players including Bharat Interface for Money (BHIM), CRED, PhonePe, Google Pay, MobiKwik, Paytm, etc. (Neema & Neema, 2018; Vivek & Selvan, 2021). Among these, Google Pay has emerged as the most preferred platform, followed by PhonePe, Paytm, and BHIM, reflecting a rapid expansion in UPI’s consumer base (Jakhiya et al., 2020). In the latest estimate from Statista, about 84 billion UPI transactions worth 139 trillion Indian rupees were made throughout India in the fiscal year 2023, almost doubling up from 2022, when the number of UPI transactions across India was just 46 billion (Keelery, 2024). Projections indicate that UPI transactions may exceed 456 billion by the fiscal year 2028. The highest UPI usage has been recorded in the states of Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka, while Hyderabad, Bengaluru, and Chennai lead among cities (Dhivya et al., 2023). The key drivers for the adoption of digital payments among merchants include demonetization, customer demand, and ease of use (Ligon et al., 2019). Among consumers, UPI usage has witnessed exponential growth (Singh & Singh, 2022) due to the rapid Internet expansion and high mobile penetration rates in India (Jena, 2023). Moreover, UPI is a highly “safe and secure payment option” for conducting transactions at any time of the day throughout the year (Chaudhari & Chaudhari, 2019; Neema & Neema, 2018; Vivek & Selvan, 2021). Other influential factors are the absence of fund transfer fees, compatibility with small transactions, cashback offers, privacy protection, secured payments, instant transfers, multi-account linkage, options of choosing apps, and widespread bank support (Jha & Sharma, 2022; Vivek & Selvan, 2021). Addtionally, considerations such as perceived risks, compatibility of applications and operating systems, comparative advantages over other payment platforms, and digital financial literacy (knowledge, awareness, skills, and experience) significantly impact UPI usage, along with concerns over external threats (Patel & Datta, 2020; Shehadeh et al., 2024). Promoting cashless transactions through UPI has furthered participation in the formal economy, reducing tax evasion, increasing financial savings, and facilitating equitable conditions for both individuals and businesses (Nigam & Kumari, 2018).

Despite its rapid adoption, the usage of UPI has not been uniform across various population segments (Ligon et al., 2019), and its adoption is yet to reach “full scale” due to consumers’ preference for cash (Nigam & Kumari, 2018; Ranpariya et al., 2021). Other challenges include inadequate internet infrastructure, technological limitations, low levels of digital literacy, limited awareness, operational complexities, and concerns related to trust and privacy (Gupta et al., 2022; Nigam & Kumari, 2018). In an effort to expand adoption, UPI applications offer various supplementary services and functionalities apart from basic money transfers, such as access to bank account statements, transaction records, expenditure history, and balance inquiries (Kuriakose et al., 2022a). In addition, promotional incentives, including rewards, coupons, cashback offers, loyalty programs, and discounts, are offered to enhance consumers’ engagement (Kapoor et al., 2022; Madan & Yadav, 2016). However, despite these efforts, consumer awareness and willingness to adopt UPI applications at a broader scale remain limited (Rana et al., 2023). Therefore, it is important to understand how UPI users perceive the add-on services or promotional benefits in an emerging digital economy like India. Existing studies have not explored the effect of add-on services or promotional strategies on consumers’ adoption intentions in the Indian context. Besides, demographic profiles such as age, gender, education, income, and occupation significantly influence UPI adoption and active usage (Patel & Datta, 2020). Research indicates that younger individuals are more inclined to use UPI compared to senior citizens (Jena, 2023; Saini & Khasa, 2023). Understanding these demographic determinants is essential for stakeholders, including retailers, entrepreneurs, policymakers, financial institutions, and technology providers, to develop more inclusive and effective digital financial solutions (Gupta et al., 2023; Raghavendra & Veeresha, 2023).

This study seeks to examine the adoption and usage of UPI through the framework of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model. The UTAUT framework identifies four key determinants of technology adoption: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, facilitating conditions, and social influence (Venkatesh et al., 2003). These factors are critical in shaping users’ behavioral intentions towards adopting UPI (Jena, 2023; Ranpariya et al., 2021). Additionally, this study extends the UTAUT model by incorporating additional factors, such as perceived trust (Joshi & Chawla, 2023; Saha & Kiran, 2022), perceived promotional benefits, and add-on services, which are highly relevant in the context of digital payments in the contemporary technological scenario.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Previous research on the adoption of mobile payment systems

Previous studies have extensively examined the factors influencing the adoption of mobile-based payment services (Chakraborty et al., 2022; Singu & Chakraborty, 2022). Various information system theories and models are introduced to explain the behavioral intention of consumers to adopt new technologies (Chakraborty et al., 2023; Chakraborty, 2023; Verma et al., 2023), especially with respect to digital payment apps (Aliu, 2024; Belmonte et al., 2024). By applying the technology acceptance model (TAM), previous studies have suggested that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness significantly influence customers’ intention (Hasan et al., 2021; Nelwan et al., 2021; Norng, 2022). However, TAM was limited in certain aspects, and more factors had to be added to explain the adoption behavior thoroughly (Belmonte et al., 2024; Putri et al., 2023). Some studies used an extended version of the TAM model by including factors, such as trust and perceived enjoyment (To & Trinh, 2021), data security and privacy (Putri et al., 2023), subjective norms (Gumussoy et al., 2018), observability and social image (Yang et al., 2023). These additional factors demonstrated a significant effect on the intention to adopt technological advancements. The UTAUT model was introduced by Venkatesh et al. (2003) to understand the adoption intention factors. The UTAUT model and its variants are most frequently employed to examine the intention and behavior toward UPI adoption (Kuriakose et al., 2022a; Ranpariya et al., 2021; Saha & Kiran, 2022; Shah, 2021; Sinha & Singh, 2023) and e-money services (Giri et al., 2019). The UTAUT model has 70% more prediction efficacy than the TAM (Gupta et al., 2023). The outcome variables are behavioral intention and continuous use of the technology being adopted. Under the UTAUT model, existing studies showed that performance expectancy (Oliveira et al., 2016; Patil et al., 2020a; Shaikh & Amin, 2023), effort expectancy (Khalilzadeh et al., 2017; Upadhyay et al., 2022), social influence (Hamzah et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2023) and facilitating conditions (Hassan et al., 2023) significantly influence adoption intention of mobile payments. However, contradictory studies showed no influence of these variables on consumer intention (Alkhwaldi et al., 2022; Bajunaied et al., 2023; Kurniasari et al., 2022). Recent studies have utilized the UTAUT 2 model by including factors, such as price value, hedonic motivation, and habit (Migliore et al., 2022; Tang & Tsai, 2024; Wu & Liu, 2023). Empirical studies extended the UTAUT and UTAUT 2 models to comprehend the significant drivers impacting the behavioral intention to adopt mobile payment systems by adding factors and theories, such as avoidance and ownership (Yang et al., 2023), awareness, security, and privacy (Al-Okaily et al., 2024), perceived trust (Gupta et al., 2023), perceived enjoyment (Nur & Panggabean, 2021), and uncertainty avoidance (Alkhwaldi et al., 2022). Apart from using TAM and UTAUT models in explaining the intention of adopting mobile payment systems, few studies have used the theory of consumption values (Chakraborty et al., 2022; Karjaluoto et al., 2021), which has depicted a significant influence on mobile payment adoption. Although the UTAUT model has been extensively used to explain mobile payment adoption behavior, it is criticized for not including variables addressing individual differences (Patil et al., 2020b; Razi-ur-Rahim et al., 2024). In addition, the impact of factors such as add-on services or promotional benefits provided by the service providers is not studied in the context of Indian UPI users (Kuriakose et al., 2022b). Besides, the true effect of promotional benefits on consumers’ behavior often remains unnoticed, as it is not observed from the consumers’ perspective. Furthermore, studies on the role of demographic factors in UPI adoption are less studied and are contradictory (Banerjee & Pradhan, 2024; Chauhan et al., 2022).

Conceptual model and hypotheses development

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework for the study. This study is based on the UTAUT model to examine the factors influencing adoption intention. The model is expanded to include perceived trust, perceived promotional benefits, and add-on services provided by UPI to consumers. The UTAUT theory, as suggested by Venkatesh et al. (2003) and its variants, behavioral intention refers to the psychological state that indicates one’s readiness or plan to engage in a specific behavior (in this case, using UPI). This intention serves as a precursor to actual behavior, whereas UPI usage behavior pertains to the tangible adoption and incorporation of the technology into routine financial transactions (Jha & Kumar, 2020; Shah, 2021). Furthermore, the theory proposes the moderating role of demographics on the impact of the UTAUT factors on the behavioral intention to adopt. When applied in the context of UPI, it was found that facilitating conditions imply the degree to which an individual user believes that organizational and technical infrastructure will support the usage of UPI, while performance expectancy is the degree to which the consumer believes that the use of UPI will help in enhancing their performance (Jena, 2023; Kuriakose et al., 2022a). Effort expectancy refers to the perceived ease of using UPI, while social influence pertains to the extent to which individuals believe that significant others expect them to adopt UPI. All four factors are expected to have a significant positive impact on the consumers’ behavioral intention of adopting UPI (Gulia & Singh, 2023; Kuriakose et al., 2022a). On the contrary, facilitating conditions (Ranpariya et al., 2021; Saha & Kiran, 2022) along with effort expectancy (Gulia & Singh, 2023; Saha & Kiran, 2022) or social influence (Gulia & Singh, 2023; Jha & Kumar, 2020), were found to be insignificant for the consumers’ intention to adopt UPI. In the study of Gupta et al. (2022), none of the four factors were found to be statistically impacting behavioral intention. Therefore, with such varying responses, it becomes critical to validate each factor in the current context. Based on this, the first hypothesis, H1: The factors of the UTAUT model (facilitating conditions, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence) significantly influence the intention to adopt UPI, constituting several sub-hypotheses individually testing their adoption intention, was proposed.

H1a: Facilitating conditions substantially boost UPI adoption by consumers.

H1b: Performance expectancy positively influences UPI adoption.

H1c: Effort expectancy leads to enhanced UPI adoption by consumers.

H1d: Social influence significantly dictates the adoption of UPI by consumers.

The UTAUT theory also implies that the behavioral intention towards the adopted technology will directly impact the actual usage and adoption. This has been reported to be true in the context of UPI, where intention has been found to drive the usage behavior of UPI users (Gupta et al., 2022; Saha & Kiran, 2022). A strong intention will most likely lead to the actual usage of the UPI mode of payment. Moreover, the prior experience of UPI usage positively influences the usage of Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) (Gupta et al., 2023). Therefore, to validate the impact of the behavioral intention of UPI adoption on actual usage in the current context, the next hypothesis was formulated as follows:

H2: The intention to adopt UPI dictates the UPI usage behavior.

According to Kuriakose et al. (2022b), the add-on services imply the supplementary services and functionalities that are provided alongside the core UPI payment services. In the current context, these services extend beyond basic money transfers, improving users’ experience and providing added value to them. Such services include bill payments, mobile and direct-to-home TV services, QR code payments, loans and credit facilities, investment and financial services, subscriptions, auto payment, account balance checks, account history, mini statements, merchant offers, cashback, split bills, etc. Based on this, the next hypotheses intend to validate the following.

H3a: The add-on services provided by UPI directly influence the intention to adopt UPI among consumers.

It is believed that add-on services provided by UPI improve performance expectancy by expanding the platform’s utility beyond the simple payment functions by increasing utility and versatility, saving time, facilitating convenience, rendering promotional offers, and offering cashback benefits (Dhivya et al., 2023; Kuriakose et al., 2022a). Thus, it can be expected that add-on services will have a certain impact on the performance expectancy of UPI (Kuriakose et al., 2022a). To test this, the following hypothesis was formulated,

H3b: The add-on services provided by the UPI significantly enhance the performance expectancy of UPI.

Apart from improving performance, add-on services may improve effort expectancy by simplifying multiple functions and making the platform more user-friendly through centralized platforms, seamless integration, user-friendly features, intuitive design, and support (Kuriakose et al., 2022a). Providing incentives and automating tasks can increase perceived value and ease of use. Based on this, the next hypothesis was proposed,

H3c: The add-on services also improve the effort expectancy of UPI.

Promotional benefits can be described as the “financial incentives” provided to attract potential users and retain them (Kuriakose et al., 2022a). Such benefits include cashback, coupons, discounts, and rewards, which are offered to users (Khanra et al., 2020). These perks can motivate users to ensure the availability of the necessary conditions at both technical and operational levels and enable compatibility of their devices. The perceived availability of support and assistance will strengthen the perceived facilitating conditions. Therefore, the next hypothesis validates this relationship.

H4a: The perceived promotional benefits provided by UPI have a significant impact on the facilitating conditions.

Promotional benefits tend to increase the perceived financial value to users, reduce perceived risks, induce positive reinforcement, encourage social influence, boost trust, and incentivize repeat usage. All of these factors collectively make mobile payment adoption more attractive and economically efficient, thereby providing a competitive edge to users and capturing their attention (Al-Saedi et al., 2019; Kukreja et al., 2020). It has been proposed that promotional benefits may positively influence the intention of UPI adoption (Jha & Kumar, 2020; Kuriakose et al., 2022b; Shah, 2021). To validate that in the current context, the next hypothesis was proposed.

H4b: The perceived promotional benefits provided by UPI significantly lead to the intention to adopt UPI.

Perceived trust seems to have a direct influence on the willingness of users to adopt digital payments, as it tends to reduce perceived risks, decrease transaction anxieties, and increase confidence in the reliability of transaction systems, banks, regulatory framework, and app providers (Khan & Abideen, 2023; Manrai & Gupta, 2020). Perceived trust was found to influence the adoption of e-banking among the aged population (Jena, 2023). This leads to the cultivation of positive experiences, which would gradually result in sustainable usage (Al-Saedi et al., 2020). Hence, we hypothesized that:

H5: Perceived trust in UPI tends to significantly influence the adoption intention of consumers.

One of the major factors that influences the usage of UPI among users is demographics (Patel & Datta, 2020). Significant differences have been observed in the adoption of UPI based on demographics, such as age, gender, monthly income, and occupation (Tungare, 2019). The adoption of UPI was much higher in males compared to females and adults over young adults. As a part of the UTAUT theory, as suggested by Venkatesh et al. (2003), demographic factors such as age, gender, education, experience, and voluntariness have been proposed to influence adoption and subsequent usage. However, it was found that neither age nor gender moderated the impact of performance expectancy on behavioral intention to adopt e-money services in Indonesia (Giri et al., 2019) or e-banking services, including UPI in India (Ranpariya et al., 2021). Therefore, for the present study, age, gender, income, and occupation were considered under demographics.

H6: Demographic factors considerably moderate the impact of UTAUT factors on the adoption of UPI.

Research methods

A quantitative research design, based on the positivistic research philosophy and employing a deductive research approach, was adopted for this study, wherein a survey was used as the primary research instrument.

Research instrument

A closed, structured questionnaire comprising four sections was developed. Section I enquired about the demographics of respondents, such as gender, age, occupation, and monthly income. Section II focused on understanding the sustained UPI usage by consumers through six items (Khan & Abideen, 2023; Patil et al., 2020b; Sharma & Sharma, 2019). Section III investigated the four factors influencing UPI usage based on the UTAUT model, such as facilitating conditions, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence. Facilitating conditions comprised four subfactors, namely Customer support (Barbu et al., 2021; Miadinovic & Xiang, 2016), Speed (Barbu et al., 2021), Assurance (Barbu et al., 2021), and Redressal of grievances (Chawla et al., 2019; Narayan & Prasadi, 2023), with five items each. Performance expectancy was measured through subfactors such as Monetary savings (Ryu, 2018b) with four items, Economic efficiency (Bajunaied et al., 2023; Ryu, 2018b) with five items, and Seamless transactions (Chao, 2019; Ryu, 2018b) with four items. Effort expectancy comprises Ease of use (Hu et al., 2019; Nigam & Kumari, 2018; Sarmah et al., 2020), Convenience (Pal et al., 2023; Ryu, 2018b; Tungare, 2019), and Complexity (Fahad, 2022; Thompson et al., 1991) with four items each. Social influence comprised two subfactors: Interpersonal influence with five items and External influence with three items (Nur & Panggabean, 2021; Tungare, 2019). Other variables, such as Perceived trust (Amnas et al., 2023; Khan & Abideen, 2023; Manrai & Gupta, 2020; Patil et al., 2020a; Roh et al., 2022), perceived promotional benefits (Kuriakose et al., 2022a), and Add-on services (Kuriakose et al., 2022a), were evaluated using five items each. Finally, Section “Results” comprised five items assessing the intention to use UPI among consumers (Amnas et al., 2023; Khan & Abideen, 2023; Manrai & Gupta, 2020; Sharma & Sharma, 2019). All items were designed as a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5), which was further used to evaluate the construct items. The questionnaire was presented in English and administered online via platforms like Google Forms.

Sample population and sample size

The study adopted a cross-sectional survey period to gather data at a specific point in time from UPI users across diverse demographic backgrounds. The target population for this study consisted of individuals in India who are current or potential users of UPI for digital payments, selected via random sampling. The sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula for large populations, ensuring statistical power and generalizability of the results. The estimated sample size was calculated to be 385 respondents, which will allow for meaningful subgroup analyses. The questionnaire was distributed to 450 consumers, out of which 416 responses were found to be valid, with a response rate of 92%.

Data analysis

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was chosen to employ SmartPLS software (version 3.3.3), as it is a robust method suitable for predictive modeling when dealing with complex models and small sample sizes (Ringle et al., 2015), as also highlighted by Jena (2023) in the context of digital payments in India. Subsequently, measurement models and structural models were estimated, leading to a comprehensive evaluation of the hypothesized relationships. The measurement model assessed the reliability and validity of the constructs used in the study, ensuring that the items appropriately measured the theoretical constructs. The structural model used path coefficients for hypotheses testing, wherein 5000 bootstrapped resamples were applied to obtain the standard errors and t-statistics (Hair et al., 2014). Moreover, the study adhered to ethical guidelines for research involving human participants. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents, assuring them of the voluntary nature of participation, anonymity, and confidentiality of their data. Respondents had the right to withdraw from the study at any stage without penalty.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic features of the study population for the current study. More than half (56.7%) of the users considered in this study were females aged 25 years or younger (60.6%) who were either employed in private organizations (39.4%) or were self-employed and had a monthly income of Rs. 750,000 and above (56.3%).

Measurement model

The measurement model was assessed using construct reliability, internal consistency, and convergent validity (Table 2, Fig. 2). Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability (CR) were used to evaluate the internal consistency of the latent variables. All the values exceeded the threshold of 0.70 to indicate satisfactory reliability. Average variance extracted (AVE) was computed to assess convergent validity, ensuring that each construct explained more than 50% of the variance in its indicators. An AVE value of 0.50 or higher was deemed to be acceptable (Hair et al., 2017). Moreover, each indicator’s loading on its respective construct was 0.70 or higher, which confirmed convergent validity, though loadings between 0.50 and 0.70 are acceptable if AVE is above the required threshold.

The discriminant validity was studied using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) elaborated in Supplementary Table A3 and Supplementary Table A4, respectively. For the discriminant validity, it was ensured that the square root of the AVE for each construct was higher than the correlation of that construct with any other construct in the model. In the case of the HTMT values, values were less than 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015), which indicated good discriminant validity.

Assessment of structural model

The evaluation of model fitness was conducted using the goodness of fit for the model, coefficient of determination (Supplementary Table A5), effect size (Supplementary Table A6), predictive relevance (Supplementary Table A7), and collinearity assessment (Supplementary Table A8). The goodness of fit for the model was estimated, and it was found that the fit indices such as standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.083, squared Euclidean distance (d_ULS) = 7.067, geodesic distance (d_G) = 93.727, chi-square (χ2) = 16588.683, and normed fit index (NFI) = 0.114 were found to be within the stipulated values indicating that the proposed measurement model had a good fit. The R2 values are crucial in PLS-SEM to assess the model’s explanatory power, which indicates the proportion of variance in the endogenous constructs explained by the exogenous constructs. It varied from 7.1% (Performance expectancy) to 44.3% (Intention to adopt UPI). As suggested by Hair et al. (2017), the effect size (f2) shows the relative impact of each independent or exogenous construct on dependent or endogenous constructs (Supplementary Table A6). According to the estimation given by Cohen (1992), the impact sizes of the associations ranged from medium to large. The blindfolding procedure was used to calculate Stone–Geisser’s Q2 to assess the predictive relevance of the model, presented in Supplementary Table A7 (Geisser, 2012; Stone, 1974). A Q2 value greater than zero indicates that the model has predictive relevance for the dependent variable (Richter et al., 2016). All the variables had the Q2 value more than zero. Therefore, it can be implied that these values were quite satisfactory.

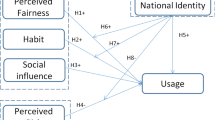

Hypothesis testing

The structural model (Fig. 3) was estimated using the bootstrapping method, which is a resampling approach in which several subsamples, such as 1000 or 5000, are obtained from the original data (Vinzi et al., 2010). The route coefficients and their significance were therefore evaluated. To validate the hypotheses, the p-value must be less than 0.05, while the t-standard statistic must be more than 1.96 (Hair et al., 2021). The results of direct and indirect effects between the constructs are presented in Table 3. It was observed that there is a statistically significant positive effect of the factors of UTAUT, such as facilitating conditions, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence, thus supporting H1. Along with this, the intention to adopt UPI among users had a positive impact on the usage behavior, thereby supporting H2. Even though add-on services significantly impacted performance expectancy and effort expectancy, they did not have any impact on the intent to adopt UPI. Thus, it can be derived that only H3b and H3c are supported. Coming to the impact of perceived promotional benefits of UPI on facilitating conditions and intention to adopt UPI, both the relationships were found to be significant, thereby suggesting that H4a and H4b both stand accepted. Further, the perceived trust was found to significantly influence the intent of UPI adoption, thereby suggesting the acceptance of H5. The direct effect of demographics on intention to adopt UPI showed that age, gender, and occupation had a direct impact on intention to adopt UPI, while income did not have any role. The indirect effects of each of the demographics showed that it was a mixed bag for age and occupation of users, with only age and occupation showing a moderating impact on the impact of performance expectancy on intention to adopt UPI, and occupation also playing a moderating role on the influence of occupation on facilitating conditions. Moreover, the gender and income of the users had no moderating role on the impact of any of the factors of UTAUT on the intention to adopt UPI. Overall, it can be construed that H6 was partially accepted.

Discussion

The rapid adoption of the UPI in India has revolutionized the digital payments landscape, establishing it as one of the most prominent modes of transactions for individuals and businesses alike. This study adopted the UTAUT theory to examine the adoption and utilization of UPI among users in India, with demographic factors serving as moderating variables. The analysis revealed that performance expectancy significantly influenced behavioral intention to adopt UPI among Indian consumers. Specifically, when individuals perceive UPI applications as highly efficient—offering user-friendly interfaces, financial savings, enhanced payment efficiency, improved financial management, and seamless transaction experiences—they are more inclined to adopt UPI. These findings are in agreement with previous studies (Gupta, 2022; Hanafiah et al., 2024; Martinez & McAndrews, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2022). Furthermore, the present study demonstrated that effort expectancy positively influenced the intention to adopt UPI apps and eventually increased usage behavior. This suggests that when consumers find the application easy to use, intuitive, and free from complexity, they are more likely to adopt it. This finding corroborates with prior studies (Hussain et al., 2019; Upadhyay et al., 2022). Furthermore, the present study identified that facilitating conditions significantly influence consumers’ intention to adopt UPI. Factors, such as a responsive customer support system, service speed and accessibility, UPI app reliability, and efficient grievance redressal mechanisms, contribute to increased adoption behavior, corroborating previous findings (Alswaigh & Aloud, 2021; Bailey et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2025). Furthermore, social influence positively influences consumer behavior. This signifies that individuals are more likely to adopt UPI when family members, friends, or influential figures, such as celebrities, endorse or actively use the platform. This observation is in line with previous research (Hamzah et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2021). Apart from validating the factors in the UTAUT model, the study showed that the add-on services of UPI did not influence the adoption intention; however, it influenced the performance expectancy and effort expectancy of UPI. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to study the effect of add-on services, such as bill payment service and credit service provided by UPI apps, on their adoption intention in India. The limited influence of add-on services on UPI adoption can be explained by the fact that Indian consumers are not used to handling different add-on services, such as online payment of utility bills, managing multiple bank accounts digitally, or using UPI for loan EMI payments. More studies are needed to understand the effectiveness of these services. The present study also depicted a significant effect of perceived promotional benefits on the adoption intention of UPI consumers. Prior research has similarly established the impact of promotional strategies on consumer adoption and switching behavior in mobile payment applications (Wang et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2021). The findings suggest that when consumers perceive promotional incentives positively, their likelihood of adopting UPI increases. With respect to the moderating role of demographic factors, the study found that gender, income, and occupation did not moderate the relationship between UTAUT model variables and adoption intention. This is in contrast to the earlier findings by Banerjee and Pradhan (2024), where consumers’ mobile adoption was found to be varied based on gender and educational qualification.

Implications of the study

The study offers significant theoretical and managerial implications concerning the adoption of mobile payment systems. The study validated the applicability of the UTAUT model in comprehending consumers’ adoption behavior. Along with this, the study introduced critical variables, such as perceived promotional benefits and add-on services, which were not studied in the context of Indian UPI adoption. Moreover, the findings of this study indicate the non-moderating role of demographics and oppose previous studies, opening further avenues in research. Apart from theoretical implications, the study provides several implications from a managerial perspective. The integration of loyalty programs, payment reminders, and multi-bank account management emerged as pivotal factors in enhancing the overall utility of UPI. Consumers who perceived UPI as offering a comprehensive suite of value-added services demonstrated a higher likelihood of adoption and continued usage. Furthermore, promotional benefits, such as cashback offers, discounts, and rewards, were found to significantly boost UPI adoption, as they provided immediate financial incentives and mitigated perceived risks associated with transitioning to a digital payment system. Trust was found to be a critical factor in determining UPI adoption, especially in terms of perceived security and privacy. Consumers who trusted UPI as a secure payment method were more likely to adopt it. Ensuring robust security measures and transparent communication about data protection can therefore enhance trust and encourage wider adoption across demographic segments. These results highlight how essential it is for UPI service providers to provide user-friendly interfaces that appeal to a variety of demographic groups, particularly older and less tech-savvy customers. Adoption of UPI among these groups can be accelerated by providing individualized help and streamlining onboarding procedures. Additionally, sustaining promotional incentives may prove effective in attracting new users, particularly from lower-income segments. To ensure equitable access to UPI, policymakers should concentrate on enhancing digital literacy and on increasing the availability of smartphones and internet connectivity.

Conclusion

All the studied UTAUT factors such as facilitating conditions, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence directly influence intention to adopt UPI, which in turn significantly affects actual UPI usage, thereby validating the model. These factors emerged as crucial predictors of UPI adoption intention. Moreover, perceived promotional benefits and trust in UPI were identified as key enablers in its adoption as a routine medium for financial transactions. However, the influence of add-on services on the intention to adopt remained inconclusive in the present study.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the valuable insights derived from this study, certain limitations must be acknowledged, particularly those associated with its cross-sectional research design. These constraints form the basis for future research to improve the robustness and generalizability of findings. The reliance on self-reported data presents potential biases, such as social desirability bias or recall inaccuracies, which may have led respondents to overestimate or underestimate their experiences with UPI or their willingness to adopt it. Future research could integrate objective data, such as transaction histories, to corroborate self-reported intentions and behaviors. In addition, future research can extend the UTAUT model by addressing variables related to specific fears, such as data breaches or misuse of personal information or technical barriers, such as low internet infrastructure and limited smartphone access, which will help to understand privacy concerns related to UPI adoption. Furthermore, factors such as local cultural norms, diverse regional economies, and varying levels of digital literacy can be investigated from the perspective of Indian consumers. Longitudinal studies could also be conducted to examine shifts in UPI adoption and usage patterns over time, thereby capturing the evolving behaviors of users in the dynamic digital payment ecosystem.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. For the transparency and accessibility of our research findings, the dataset utilized in this research paper could be accessed via a secure drive link upon request.

Change history

11 August 2025

In this article, the citation metadata for the author Padma Kiran K. was listed as “K, P.K.” , this has been updated to reflect the correct name as “Padma Kiran, K.” to ensure accurate indexing and citation. The original article has been corrected.

References

Al-Okaily M, Alalwan AA, Al-Fraihat D, Alkhwaldi AF, Rehman SU, Al-Okaily A (2024) Investigating antecedents of mobile payment systems’ decision-making: a mediated model. Glob Knowl Mem Commun 73(1/2):45–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/GKMC-10-2021-0171

Al-Saedi K, Al-Emran M, Abusham E, El-Rahman SA (2019) Mobile payment adoption: a systematic review of the UTAUT model. Int Conf Fourth Ind Revolut 2019:4–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICFIR.2019.8894794

Al-Saedi K, Al-Emran M, Ramayah T & Abusham E (2020) Developing a general extended UTAUT model for M-payment adoption. Technol Soc 62(September). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101293

Aliu F (2024) Usage and adoption intent of NFC payment methods: an investigation based on the UTAUT-3 model and perceived risk theory. J Sci Technol Policy Manag https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTPM-01-2024-0013

Alkhwaldi AF, Alharasis EE, Shehadeh M, Abu-AlSondos IA, Oudat MS, Bani Atta AA (2022) Towards an understanding of FinTech users’ adoption: intention and e-loyalty post-COVID-19 from a developing country perspective. Sustainability 14(19):1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912616

Alswaigh NY, Aloud ME (2021) Factors affecting user adoption of E-payment services available in mobile wallets in Saudi Arabia. Int J Comput. Sci Netw Secur 21(6):222. https://doi.org/10.22937/IJCSNS.2021.21.6.29

Amnas MB, Selvam M, Raja M, Santhoshkumar S & Parayitam S (2023) Understanding the determinants of FinTech adoption: integrating UTAUT2 with trust theoretic model. J Risk Financ Manag 16(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16120505

Bailey AA, Bonifield CM, Arias A, Villegas J (2022) Mobile payment adoption in Latin America. J Serv Mark 36(8):1058–1075. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-04-2021-0130

Bajunaied K, Hussin N & Kamarudin S (2023) Behavioral intention to adopt FinTech services: an extension of unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. J Open Innov 9(100010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joitmc.2023.100010

Banerjee AK, Pradhan HK (2024) Influence of demographic profiles in adoption of digital payment system in India: a multigroup invariance analysis. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 36(10):2285–2301. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2022.2132928

Barbu CM, Florea DL, Dabija DC, Barbu MCR (2021) Customer experience in fintech. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res 16(5):1415–1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16050080

Belmonte ZJA, Prasetyo YT, Cahigas MML, Nadlifatin R, Gumasing MJJ (2024) Factors influencing the intention to use e-wallet among generation Z and millennials in the Philippines: an extended technology acceptance model (TAM) approach. Acta Psychol 250:104526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104526

Chakraborty D, Siddiqui M, Siddiqui A, Paul J, Dash G, Dal Mas F (2023) Watching is valuable: consumer views—content consumption on OTT platforms. J Retail Consum Serv 70:103148

Chakraborty D (2023) Purchase behavior of consumers toward GSAs: a longitudinal assessment. J Comput Inf Syst 63(5):1031–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2022.2123065

Chakraborty D, Siddiqui A, Siddiqui M, Rana NP, Dash G (2022) Mobile payment apps filling value gaps: integrating consumption values with initial trust and customer involvement. J Retail Consum Serv 66:102946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102946

Chao CM (2019) Factors determining the behavioral intention to use mobile learning: an application and extension of the UTAUT model. Front Psychol 10(JULY):1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01652

Chaudhari A, Chaudhari D (2019) To study the consumer satisfaction on UPI (Unified Payments Interface) with special reference to Hyderabad and Suburbs. Int Multidiscip E- Res J 207:231–233

Chauhan S, Kumar P, Gajpal Y, Motiwalla L (2022) Investigating trust in mobile payment services in india: the moderating role of gender. J Theor Appl Inf Technol 100(20):6049–6060

Chawla P, Singhal A, Bajaj P (2019) A study on awareness and adoption of Unified Payments Interface (UPI) for digital payments. A J Compos Theory XII(XI):1396–1404

Cohen J (1992) Statistical Power Analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed). Lawrebce ELbaum Associates

Dhivya M, Balamourougane R, Nithin J, Raj RV (2023) Unified payment interface: a Unique Payment Interface in the Universe—secondary data analysis. Eur Econ Lett 13(3):1259–1267

Fahad, MS (2022). Exploring the determinants of adoption of Unified Payment Interface (UPI) in India: a study based on diffusion of innovation theory. Digit Bus 2(100040). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.digbus.2022.100040

Geisser S (2012) The predictive sample reuse method with applications. J Am Stat Assoc 70(350):320–328

Giri RRW, Apriliani D, Sofia A (2019) Behav Intent Anal E-Money Serv Indonesia: Using modified UTAUT Model 65(Icebef 2018):73–76. https://doi.org/10.2991/icebef-18.2019.17

Gochhwal R (2017) Unified Payment Interface—an advancement in payment systems. Am J Ind Bus Manag 07(10):1174–1191. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2017.710084

Gulia A, Singh L (2023) Adoption of UPI (Unified Payments Interface) by rural people: an empirical investigation. IITM J Bus Stud 11(1):23–41

Gumussoy CA, Kaya A & Ozlu E (2018) Determinants of mobile banking use: an extended TAM with perceived risk, mobility access, compatibility, perceived self-efficacy and subjective norms. In: Industrial Engineering in the Industry 4.0 Era, pp. 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71225-3_20

Gupta M, Taneja S, Sharma V, Singh A, Rupeika-Apoga R, Jangir K (2023) Does previous experience with the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) affect the usage of central bank digital currency (CBDC)? J Risk Financ Manag 16(6):286. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16060286

Gupta P, Kapoor K, Bharadwaj S, Singh R (2022) Behavioural intention and user contentment towards digital payment—a study on UPI amongst Indian Masses. Cent Eur Manag J 30:1921–1933. https://doi.org/10.57030/23364890.cemj.30.4.195

Gupta RK (2022) Adoption of mobile wallet services: an empirical analysis. Int J Intellect Prop Manag 12(3):341. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIPM.2022.124634

Gupta S, Kiran R & Sharma RK (2023) Embedding technology interface and digital payment drivers in the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology 2 model: transforming behavioral intention to sustained intention. Sustainability (Switzerland), 15(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713018

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP & Ray S (2021) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R. In: Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation (21, Issue 1)

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L, Kuppelwieser VG (2014) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur Bus Rev 26(2):106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Hair J, Hollingsworth CL, Randolph AB, Chong AYL (2017) An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind Manag Data Syst 117(3):442–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-04-2016-0130/FULL/XML

Hamzah MI, Ramli FAA, Shaw N (2023) The moderating influence of brand image on consumers’ adoption of QR-code e-wallets. J Retail Consum Serv 73:103326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103326

Hanafiah MH, Asyraff MA, Ismail MNI, Sjukriana J (2024) Understanding the key drivers in using mobile payment (M-Payment) among Generation Z travellers. Young Consum 25(5):645–664. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-08-2023-1835

Hasan R, Ashfaq M & Shao L (2021) Evaluating drivers of fintech adoption in the Netherlands. Glob Bus Rev https://doi.org/10.1177/09721509211027402

Hassan MS, Islam MA, Yusof MF bin, Nasir H & Huda N (2023) Investigating the determinants of Islamic Mobile FinTech service acceptance: a modified UTAUT2 approach. Risks 11(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/risks11020040

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43:115–135

Hu Z, Ding S, Li S, Chen L & Yang S (2019) Adoption intention of fintech services for bank users: An empirical examination with an extended technology acceptance model. Symmetry 11(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11030340

Hussain M, Mollik AT, Johns R, Rahman MS (2019) M-payment adoption for bottom of pyramid segment: an empirical investigation. Int J Bank Mark 37(1):362–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-01-2018-0013

Jakhiya M, Mittal Bishnoi M & Purohit H (2020) Emergence and growth of mobile money in modern India: a study on the effect of mobile money. 2020 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences, ASET 2020, pp 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/ASET48392.2020.9118375

Jena R (2023) Factors impacting senior citizens ’ adoption of E-banking post COVID-19 pandemic: an empirical study from India. J Risk Financ Manag 16(380). https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16090380

Jha A & Sharma R (2022) Unified Payment Interface (UPI)—India’s next transformation. In: Developments and Trends in the Banking and Finance Sector. Empyreal Publishing House, pp 49–57

Jha R, Kumar R (2020) UPI—an innovative step for making digital payment effective and consumer perception on Unified Payment Interface. Int J Anal Exp Modal Anal 8(7):f698–f705

Joshi H, Chawla D (2023) Identifying unobserved heterogeneity in mobile wallet adoption—a FIMIX-PLS approach for user segmentation. Int J Bank Mark 41(1):210–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-03-2022-0132

Kapoor A, Sindwani R, Goel M, Shankar A (2022) Mobile wallet adoption intention amid COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: a novel conceptual framework. Comput Ind Eng 172(PB):108646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2022.108646

Karjaluoto H, Glavee-Geo R, Ramdhony D, Shaikh AA, Hurpaul A (2021) Consumption values and mobile banking services: understanding the urban–rural dichotomy in a developing economy. Int J Bank Mark 39(2):272–293. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-03-2020-0129

Keelery S (2024) Number of Unified Payments Interface transactions across India from financial year 2019 to 2023, with estimates until 2028. Statista https://www.statista.com/statistics/1247111/india-number-of-upi-transactions/

Khalilzadeh J, Ozturk AB, Bilgihan A (2017) Security-related factors in extended UTAUT model for NFC based mobile payment in the restaurant industry. Comput Hum Behav 70(2017):460–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.001

Khan WA & Abideen ZU (2023) Effects of behavioural intention on usage behaviour of digital wallet: the mediating role of perceived risk and moderating role of perceived service quality and perceived trust. Future Bus J 9(73). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-023-00242-z

Khanra S, Joseph RP, Dhir A, Kaur P (2020) Antecedents of the barriers toward the adoption of Unified Payment Interface. IFIP Adv Inf Commun Technol 618:608–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64861-9_53

Kukreja G, Bahl D & Gupta R (2020) The impact of FinTech on financial services in India: past, present, and future trends. In: Innovative Strategies for Implementing FinTech in Banking. IGI Global pp 191–200 https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-3257-7.ch012

Kuriakose A, Sajoy PB & George E (2022a) Modelling the Consumer Adoption Intention towards Unified Payment Interface (UPI): an extended UTAUT2 model with relative advantage, add-on services and promotional benefits. In: 2022 International Conference on Interdisciplinary Research in Technology and Management, IRTM 2022—Proceedings, pp 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/IRTM54583.2022.9791524

Kuriakose A, Sajoy PB & George E (2022b) Modelling the consumer adoption intention towards Unified Payment Interface (UPI): an extended UTAUT2 model with relative advantage, add-on services and promotional benefits. In: 2022 International Conference on Interdisciplinary Research in Technology and Management, IRTM 2022—Proceedings, February 2023, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/IRTM54583.2022.9791524

Kurniasari F, Tajul Urus S, Utomo P, Abd Hamid N, Jimmy SY, Othman IW (2022) Determinant factors of adoption of Fintech payment services in Indonesia using The UTAUT approach. Asia-Pac Manag Account J 17(1):97–125. https://doi.org/10.24191/apmaj.v17i1-04

Ligon E, Malick B, Sheth K, Trachtman C (2019) What explains low adoption of digital payment technologies? Evidence from small-scale merchants in Jaipur, India. PLoS ONE 14(7):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219450

Madan K, Yadav R (2016) Behavioural intention to adopt mobile wallet: a developing country perspective. J Indian Bus Res 8(3):227–244. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-10-2015-0112

Manrai R & Gupta KR (2020) Integrating UTAUT with trust and perceived benefits to explain user adoption of mobile payments. In: PK Kapur & O Sigh (eds), Strategic System Assurance and Business Analytics, pp 109–121

Martinez BM, McAndrews LE (2021) The influence of mobile application design features on users’ stickiness intentions as mediated by emotional response. Int J Retail Distrib Manag 49(11):1497–1511. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-06-2020-0232

Miadinovic J & Xiang H (2016) A Study on Factors Affecting the Behavioral Intention to use Mobile Shopping Fashion Apps in Sweden. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:933382/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Migliore G, Wagner R, Cechella FS, Liébana-Cabanillas F (2022) Antecedents to the Adoption of Mobile Payment in China and Italy: an Integration of UTAUT2 and Innovation Resistance Theory. Inf Syst Front 24(6):2099–2122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-021-10237-2

Narayan A & Prasadi S (2023) Do UPI In-App Grievance Redress Mechanisms work for constrained users? https://blog.dvararesearch.com/2023/03/31/do-upi-in-app-grievance-redress-mechanisms-work-for-constrained-users/

Neema K, Neema A (2018) UPI (Unified Payment Interface)-A new technique of digital payment: an explorative study. Int J Curr Res Multidiscip 3(10):1–10. https://www.india-briefing.com/news/growth-of-digital-payments-systems-in-india-

Nelwan JZC, Yasa NNK, Sukaatmadja IPG, Ekawati NW (2021) Antecedent behaviour and its implication on the intention to reuse the internet banking and mobile services. Int J Data Netw Sci 5(3):451–464. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.ijdns.2021.4.003

Nguyen TA, Dick M, Nguyen BTT, Le Quynh, Vu G, Nguyen LTB, Le HD (2022) The effect of culture on performance expectancy, intention, and trust in mobile payment adoption. Int J E-Serv Mob Appl 14(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJESMA.285546

Nigam A, Kumari S (2018) Adoption of United Payment Interface application: an empirical investigation using TAM framework. CPJ Glob Rev 10(2):29–36. https://www.cpj.edu.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/CPJ-Global-Review-July-2018-dt.-29-08-2018-Final-min.pdf#page=11

Norng S (2022) Factors influencing mobile banking adoption in Cambodia: the structuring of TAM, DIT, and trust with TPB. Asian J Bus Res 12(3):21–42. https://doi.org/10.14707/ajbr.220133

Nur T, Panggabean RR (2021) Factors Influencing the adoption of mobile payment method among generation Z: the extended UTAUT Approach. J Account Res Organ Econ 4(1):14–28. https://doi.org/10.24815/jaroe.v4i1.19644

Oliveira T, Thomas M, Baptista G, Campos F (2016) Mobile payment: understanding the determinants of customer adoption and intention to recommend the technology. Comput Hum Behav 61:404–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.030

Pal, A, De, R, & Rao, HR (2023). Why would microentrepreneurs continue using mobile payments? An entrepreneurial perspective with evidence from India. ECIS 2023 Research Papers, 374. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2023_rp/374

Patel NL, Datta JS (2020) Factors influencing the usage of UPI among customers. Int J Creative Res Thoughts 8(9):1589–1596

Patil P, Tamilmani K, Rana NP & Raghavan V (2020a) Understanding consumer adoption of mobile payment in India: Extending Meta-UTAUT model with personal innovativeness, anxiety, trust, and grievance redressal. Int J Inf Manag 54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102144

Patil P, Tamilmani K, Rana NP, Raghavan V (2020b) Understanding consumer adoption of mobile payment in India: extending Meta-UTAUT model with personal innovativeness, anxiety, trust, and grievance redressal. Int J Inf Manag 54(February):102144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102144

Priya PK, Anusha K (2019) Fintech issues and challenges in India. Int J Recent Technol Eng 8(3):904–908. https://doi.org/10.35940/ijrte.C4087.098319

Putri GA, Widagdo AK & Setiawan D (2023) Analysis of financial technology acceptance of peer to peer lending (P2P lending) using extended technology acceptance model (TAM). J Open Innov 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joitmc.2023.100027

Raghavendra V, Veeresha P (2023) Analysing the market for digital payments in India using the predator-prey mode. l Int J Optim Control 13(1):104–115. https://doi.org/10.11121/ijocta.2023.1306

Rajeswari P, Vijai C (2021) Fintech industry in India: the revolutionized finance sector. Eur J Mol Clin Med 8(11):4300–4306. https://www.investindia.gov.in

Rana NP, Luthra S, Rao HR (2023) Assessing challenges to the mobile wallet usage in India: an interpretive structural modelling approach. Inf Technol People 36(4):1533–1554. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-07-2021-0535

Ranpariya T, Joshi A & Rajdev A (2021) Factors driving the adoption of E-banking services based on the UTAUT model. Sustain Dev 5–11. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v14n6p43

Razi-ur-Rahim M, Rabbani MR, Uddin F, Shaikh ZH (2024) Adoption of UPI among Indian users: using extended meta-UTAUT model. Digital Bus 4(2):100093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.digbus.2024.100093

Richter NF, Sinkovics RR, Ringle CM, Schlägel C (2016) A critical look at the use of SEM in international business research. Int Mark Rev 33(3):376–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-04-2014-0148

Ringle CM, Wende S & Becker JM (2015) SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt

Roh T, Yang YS, Xiao S & Park BI (2022) What makes consumers trust and adopt fintech? An empirical investigation in China. Electron Commerce Res 1–33

Ryu HS (2018b) What makes users willing or hesitant to use Fintech?: the moderating effect of user type. Ind Manag Data Syst 118(3):541–569. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2017-0325

Saha P, Kiran KB (2022) An exploration of trust as an antecedent of Unified Payment Interface Usage: a SEM-neural network approach. Int J Electron Gov Res 18(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJEGR.298627

Saini L, Khasa S (2023) Behavioural intention to use mobile payments in the light of the UTAUT2 model. Eduzone 12(1):219–230. www.allcommercejournal.com

Sarmah R, Dhiman N, Kanojia H (2020) Understanding intentions and actual use of mobile wallets by millennial: an extended TAM model perspective. J Indian Bus Res 13(3):361–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-06-2020-0214

Shah V (2021) Adoption Intention of UPI Payment Method Using Unified Theory. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol 9(12):1456–1460. https://doi.org/10.22214/ijraset.2021.39544

Shaikh IM & Amin H (2023) Consumers’ innovativeness and acceptance towards use of financial technology in Pakistan: extension of the UTAUT model. Inf Discov Deliv (ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1108/IDD-08-2022-0080

Sharma SK, Sharma M (2019) Examining the role of trust and quality dimensions in the actual usage of mobile banking services: an empirical investigation. Int J Inf Manag 44:65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.09.013

Shehadeh M, Ajouz M, Abu-AlSondos IA, Alkhwaldi AF & Jaber JJ (2024) Exploring the path from digital financial literacy to QR payment adoption. In: Artificial Intelligence, Digitalization and Regulation pp 153–166 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-67531-7_14

Singh NK, Singh P (2022) Identifying consumer resistance of mobile payment during Covid-19: an interpretive structural modeling (ISM) approach. Bus Manag Econ Eng 20(2):258–285. https://doi.org/10.3846/bmee.2022.16905

Singu HB & Chakraborty D (2022) I have the bank in my pocket: theoretical evidence and perspectives. J Public Affairs 22(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2568

Sinha N, Singh N (2023) Moderating and mediating effect of perceived experience on merchant’s behavioral intention to use mobile payments services. J Financ Serv Mark 28:448–465. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41264-022-00163-y

Stone M (1974) Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J R Stat Soc 36(2):111–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1976.tb01573.x

Tang J-W, Tsai P-H (2024) Exploring critical determinants influencing businesses’ continuous usage of mobile payment in post-pandemic era: based on the UTAUT2 perspective. Technol Soc 77:102554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102554

Thompson RL, Higgins CA, Howell JM (1991) Personal computing: toward a conceptual model of utilization. MIS Q 15(1):125–143

To AT & Trinh THM (2021) Understanding behavioral intention to use mobile wallets in Vietnam: extending the TAM model with trust and enjoyment. Cogent Bus Manag 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1891661

Tungare V (2019) A study on customer insight towards UPI (Unified Payment Interface)—an advancement of mobile payment system. Int J Sci Res 8(4):1408–1412

Upadhyay N, Upadhyay S, Abed SS & Dwivedi YK (2022) Consumer adoption of mobile payment services during COVID-19: extending meta-UTAUT with perceived severity and self-efficacy. Int J Bank Market https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-06-2021-0262

Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD (2003) User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q 27(3):425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

Verma A, Chakraborty D, Verma M (2023) Barriers of food delivery applications: a perspective from innovation resistance theory using mixed method. J Retail Consum Serv 73:103369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103369

Vinzi VE, Chin WW, Henseler J & Wang H (2010) Handbook of partial least squares. Springer, Berlin

Vivek N, Selvan SA (2021) Factors Influencing the Users of Unified Payments Interface in India. Utkal Hist Res J 34(1):165–167

Wang L, Luo X(Robert), Yang X, Qiao Z (2019) Easy come or easy go? Empirical evidence on switching behaviors in mobile payment applications. Inf Manag 56(7):103150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.02.005

Wei MF, Luh YH, Huang YH, Chang YC (2021) Young generation’s mobile payment adoption behavior: analysis based on an extended utaut model. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res 16(4):1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16040037

Wu Z, Liu Y (2023) Exploring country differences in the adoption of mobile payment service: the surprising robustness of the UTAUT2 model. Int J Bank Mark 41(2):237–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-02-2022-0052

Xu P, Kim CS, Bai B, Kim PB (2025) Determinants of Chinese travellers’ use of mobile payment applications when staying at an overseas hotel. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour 26(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2023.2196036

Yan C, Siddik AB, Akter N, Dong Q (2021) Factors influencing the adoption intention of using mobile financial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of FinTech. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(22):61271–61289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17437-y

Yan C, Siddik AB, Akter N, Dong Q (2023) Factors influencing the adoption intention of using mobile financial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of FinTech. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(22):61271–61289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17437-y

Yang, CC, Yang, SY, & Chang, YC (2023) Predicting older adults’ mobile payment adoption: an extended TAM model. Int J Env Res Public Health 20(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021391

Yang X, Yang J, Hou Y, Li S, Sun S (2023) Gamification of mobile wallet as an unconventional innovation for promoting Fintech: an fsQCA approach. J Bus Res 155(PA):113406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113406

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: KPK; Literature review: KPK and VNS; Methodology: KPK; Data Collection: KPK and VNS; Analysis: KPK; Writing—Original Draft: KPK; Writing—Review and Editing: KPK and VNS; Supervision: VNS. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study is a non-interventional, survey-based research project involving adult human participants. It complies with institutional ethical standards and internationally recognized ethical guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Research Progress and Assessment Committee (R-PAC) of KLEF Deemed to be university on 17 August 2023 (Approval Code: RPAC/PhD/2023/1029) where Padma Kiran K is pursuing a PhD. Additionally, as part of the author’s PhD research, the study received ethical approval from the university.

Informed consent

This study involved adult human participants who completed a questionnaire as part of the research. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants between 22 August 2023 and 20 February 2024 who were involved in the study. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and were assured that their personal details would be kept confidential. They were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time without any consequences. The questionnaire included questions designed to assess participants’ opinions on the (UPI) Unified Payments Interface usage for digital payments. This allowed the researchers to gather insights into participants’ perspectives on these matters.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Padma Kiran, K., Vedala, N.S. Assessing Unified Payments Interface (UPI) adoption and usage through the interplay of UTAUT factors. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1060 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05313-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05313-w