Abstract

Judicial development (JD) is a crucial factor influencing regional economic growth. This study delves into the non-linear relationship between JD and regional economic performance. Focusing on China, we propose an inverted U-shaped hypothesis based on a path analysis of influencing mechanisms. This hypothesis is empirically tested using non-linear regression and threshold regression models. The findings reveal that: (1) In both the baseline regression and the System Generalized Method of Moments (SYS-GMM) model, the linear term of judicial development level (JDL) is significantly positive, while the quadratic term is significantly negative, indicating an inverted U-shaped impact of JD on China’s economic growth. (2) The threshold regression model confirms this hypothesis, as the threshold variable passes the single-threshold test, and the coefficients shift from positive to negative. (3) Employment, gross capital formation, and the marketization index positively contribute to China’s economic growth, while the full-time equivalent of R&D personnel shows no significant effect. (4) Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the inverted U-shaped structure is most pronounced in the eastern region, suggesting that its JD has entered a phase of institutional marginal inhibition. The central region also exhibits a non-linear pattern, though its boundary remains ambiguous. In contrast, the western region is still in a phase where JD continues to release institutional dividends that drive growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Research on factors influencing economic growth has always been a focal point for scholars from various fields. The Cobb-Douglas production function categorizes factors affecting regional economic growth into labor input, capital input, and production efficiency. With the continuous development of the economy, neither labor supply nor investable capital remains infinite; both face binding constraints. Promoting stable economic growth can only be achieved through sustained improvement in production efficiency. As a cornerstone of regional economic development, judicial development (JD) profoundly influences the quality of life for residents and the production efficiency of enterprises. Therefore, JD has a significant impact on the stable economic growth of a region (Dong and Voigt, 2022). Advancing regional JD improves the legal system, deepens market-oriented reforms, clarifies property rights definitions and protections, and ensures contract implementation. Additionally, promoting the level of JD can also restrict excessive government intervention, strengthen the construction of a fair law enforcement team, and enhance fair competition. Furthermore, the efficient and transparent judicial system can construct a stable and predictable business environment, creating favorable conditions for regional economic growth. Finally, with the acceleration of the globalization process, JD not only profoundly influences the lives of residents and enterprise production within a region but also has far-reaching effects on international interactions and foreign investment.

Within China’s “new normal” economic phase—characterized by moderated growth—identifying new productivity-led drivers has become a strategic imperative. From the perspective of the JD, the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) introduced the comprehensive promotion of the rule of law as a guiding principle, providing a legal framework for the economy (Ip, 2012). The 19th National Congress of the CPC underscored that judicial construction constitutes a profound revolution in national governance and represents a key element in ensuring stable and sustained economic growth (Chang and Ren, 2018). The 20th National Congress of the CPC further deepened the support of JD for the economy, emphasizing the complementary relationship between the judiciary and economic development (Zheng, 2023). This series of judicial development strategies has guided the establishment of a fair and transparent judicial environment and cultivated new drivers of economic growth. It has reinforced the pivotal role of the judiciary in promoting economic development.

This paper focuses on the relationship between JD and economic growth in China and forms the following research framework. First, by leveraging existing research outcomes and analytical approaches, targeted research hypotheses are proposed. Second, an assessment of the current state of JD in China is conducted by constructing a comprehensive evaluation indicator system. Third, an econometric model is meticulously built to rigorously examine the potential impact of JD on China’s economic growth. Fourth, based on empirical analysis, specific recommendations are put forth to facilitate stable economic growth in China.

Literature review

Through a review of existing economic growth literature, this study classifies growth determinants into two core categories: (1) production factors encompassing factor inputs and efficiency metrics, and (2) demand factors. Narrowly defined production factors mainly encompass capital, labor, land, and other natural resources. However, land and other natural resources are often considered a form of capital. Consequently, numerous scholars have extensively researched the impact of capital (Coşkun et al., 2017) and labor (Obere et al., 2013) on economic growth. Secondly, production efficiency is a key driver of economic growth. Many scholars, focusing on perspectives such as technological level (Vitenu-Sackey et al., 2022), supply chain management (Khan et al., 2018), and business environment (Vitenu-Sackey and Barfi, 2021), have studied the impact of production efficiency on regional economic growth. On the other hand, some scholars, based on a demand perspective, further investigated the influence of consumption (Wang and Li, 2024), investment (Xinying et al., 2019), and foreign trade (Nguyen, 2020) on economic growth.

JD constitutes a vital component of the institutional environment and exerts a profound influence on productive efficiency. Scholars across the globe have conducted extensive research on the economic implications of judicial advancement. Firstly, numerous studies indicate that JD has a significant stimulating effect on the growth of regional economies. Research by scholars such as Jappelli suggests that a higher level of the judicial environment contributes to boosting investor confidence, promoting local and external investments, thereby stimulating production, creating employment opportunities, and driving regional economic growth (Jappelli et al., 2005). Chemin, focusing on India, found that a robust judicial system typically implies more effective protection of intellectual property rights, fostering innovation, promoting technological progress, and driving economic growth (Chemin, 2012). Ippoliti et a, through international comparative studies, discovered that regions with well-developed judicial systems are more likely to attract foreign direct investment, thereby driving economic activities within the region, promoting industrial upgrading, and introducing new technologies (Ippoliti et al., 2015). Melcarne’s research indicates that advancing JD helps enhance corporate compliance management and market transparency, t enhancing the business environment and boosting confidence among investors and consumers (Melcarne and Ramello, 2015).

Furthermore, as research progresses, some scholars have found that an excessively high level of JD can negatively impact economic growth. Research by Messick et al. demonstrates that judicial over-institutionalization invites political interference, distorting market principles and thereby undermining business activity while constraining economic growth (Messick, 1999). Chemin et al. found that excessively high JD can result in an overemphasis on legal procedures. Businesses may face excessive legal constraints in economic activities, making business operations overly cautious and conservative, hindering business flexibility and innovation (Chemin et al., 2009). Research by Di et al. suggests that excessively high JD can lead to high costs for legal services, including lawyer fees and court costs, adding to the economic burden of businesses and residents (Di Vita et al., 2019). Martínez-Alier found that an excessively high level of JD seriously reduces investments and capital flows that do not conform to sustainable growth in regional economies (Martínez-Alier, 2012).

In conclusion, the positive impact of JD on economic growth during its process has garnered widespread support from numerous scholars. However, its negative effects on the economy during the process should not be overlooked, though existing research results in this regard are relatively limited. Evidently, the relationship between JD and economic growth is not merely linear; a more complex, non-linear relationship may exist. As such, this paper focuses on China’s economy, aiming to conduct an in-depth analysis of the non-linear impact of JD on China’s economic growth by constructing an evaluation index system suitable for China’s JD.

Influencing mechanism and hypothesis

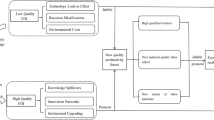

JD plays a crucial role in promoting regional economic growth, and its impact on regional economic growth varies at different stages. This paper conducts a path analysis of the relationship between JD and China’s economic growth by building upon a review of existing research results to formulate this research’s hypotheses, as shown in Fig. 1.

The first stage is the initiation of the promoting effect. In this stage, the level of JD is relatively low, and various issues in JD become evident. These issues include an incomplete legal framework, difficulties in contract enforcement, inadequate property rights protection, and low efficiency in resolving commercial disputes. Against this backdrop, investors and businesses face significant judicial uncertainty, leading to a decline in confidence in the economic environment. Consequently, their willingness to engage in economic activities decreases, imposing constraints on economic growth (Samuels, 1971).

The second stage is the expansion of the promoting effect. In this stage, rapid advancement in JD effectively safeguards regional enterprises’ and residents’ legitimate interests. This manifests through three key mechanisms: (1) Enhanced Institutional Efficiency: JD improvements strengthen judicial systems (Lu & Yao, 2009), enabling expedited commercial dispute resolution, robust contract and property rights, reduced transaction costs and constrained arbitrary government intervention. These institutional gains boost business operational efficiency and confidence, spurring investment, innovation, and production expansion—ultimately strengthening regional economic vitality. (2) The elevation of the JD level contributes to strengthening China’s economic competitiveness on the international stage. This, in turn, attracts more international investors, injecting new vitality into China’s economic growth (Kaplow, 1986). (3) The improvement in the level of JD helps to maintain social stability. A fair judicial system enhances the sense of social justice and reduces social conflicts and dissatisfaction, thereby increasing the production efficiency of enterprises and individuals and driving economic growth (Butkiewicz and Yanikkaya, 2006).

The third stage is the deceleration of the effect. In this stage, when the level of JD reaches a certain point, certain factors cause the economic promotion effects of JD to gradually slow down. This is because, at this stage, the judicial system is relatively sound, contract enforcement and property rights protection are well-established, and government restrictions on business activities have significantly decreased (Ginsburg, 2000). Therefore, the positive impact of the elevation of the level of JD on economic growth gradually weakens. Economic growth is increasingly influenced by other factors, such as macroeconomic policies and market demand.

The fourth stage is the inhibition effect stage. In this stage, when the level of JD reaches saturation, the economic promotion effects of JD gradually transform into inhibition effects (Haidar, 2012). The primary reasons are as follows: (1) An excessively high level of JD may lead to an overemphasis on legal procedures, imposing numerous legal constraints on enterprises. This can render business operations overly cautious and conservative, hindering flexibility and innovation. For instance, high-tech startups in Beijing’s Zhongguancun face delays or suspensions in innovation activities due to complex judicial procedures surrounding financing and intellectual property. (2) An advanced level of JD may also result in prohibitively high legal service costs, including attorney fees and court expenses, increasing the financial burden on businesses and individuals and thus impeding economic growth. For example, in Shanghai’s Pudong New Area, the high legal costs and lengthy processes involved in foreign-related commercial litigation significantly raise the cost of rights protection and operations, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises. (3) As JD progresses, governments increasingly emphasize legal frameworks related to environmental protection, intellectual property rights, and personal privacy, prioritizing sustainable economic growth. For instance, in the Taicang Port Economic Development Zone in Jiangsu, stricter environmental judicial reviews have led to the suspension or withdrawal of multiple investment projects, illustrating how high judicial standards may suppress unsustainable investment flows. As a result, regional JD at this stage may hinder the inflow of investments that do not align with the principles of sustainable economic growth.

In summary, maintaining an appropriate level of JD is crucial for promoting economic growth. A rational JD can safeguard the legal order without constraining the vitality of economic entities, thereby promoting economic growth. Based on the above theoretical research, this paper proposes the following research hypothesis: The impact of JD on China’s economic growth follows an inverted U-shape. That is, there is a positive relationship within a certain range, but with the comprehensive impact of a series of factors, this relationship may reverse.

Research design

China’s JD evaluation

China’s JD evaluation index system

Assessing the level of China’s JD is a key aspect of quantitatively studying the impact of JD on economic growth. The evaluation of regional JD includes assessments of the regional legal system, access to judicial services, civic legal awareness, case processing efficiency, and other various aspects (Marciano et al., 2019). However, there is currently no widely accepted set of indicators and publicly available authoritative statistical data for measuring the level of JD. Therefore, most scholars use related indicators as proxies for the level of JD (Kaufmann et al., 1999). Drawing on Voigt’s research, this paper selects 11 indicators from four dimensions—legal framework, judicial services, case volume, and case processing—to construct the evaluation index system for China’s JD, as detailed in Table 1 (Voigt, 2012; Voigt, 2013; Voigt, 2016).

Evaluation method for China’s JD

The aforementioned four dimensions and 11 specific indicators reflect different facets and levels of China’s JD. To enhance the objectivity, accuracy, and comprehensiveness in gauging the level of JD in China, this paper integrates the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Entropy Method (EM). The AHP is employed to determine the weights of the criteria at the top level, while the EM is utilized to ascertain the weights of the indicators at the lower level (Xiao et al., 2022).

The comprehensive use of AHP and the EM leverages the strengths of each method, enhancing the comprehensiveness and robustness of the evaluation model (Shen and Liao, 2022). AHP, characterized by a clear structure and subjective involvement, is more suitable for small-scale problems. The EM proves more efficient in handling large-scale problems by considering information entropy to mitigate subjective influences. AHP considers interdependencies between indicators through pairwise comparisons but is sensitive to correlation. In contrast, the EM is relatively independent of indicator relationships. Additionally, AHP introduces decision-makers through the hierarchy structure and comparisons, while the EM reduces reliance on pairwise comparisons through computation. Therefore, integrating both methods maintains clarity in problem structure, improves computational efficiency, balances subjective and objective factors, and enhances the robustness of the evaluation model.

Model construction

This research explores whether an inverted U-shaped relationship exists between JD and economic growth in China. To achieve this objective, the study focuses on the 30 provinces in China from 2000 to 2019. This timeframe is chosen considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on China’s economy in 2020 and 2021, as well as data gaps in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Furthermore, by carefully selecting the study subjects and considering external factors, this research establishes non-linear panel regression models and threshold regression models to unveil the non-linear impact of JD on China’s economic growth (Chen and Lee, 2005).

Variables selection

The selection of variables in an econometric model requires a thorough consideration of their complex relationships (Glaeser et al., 2004). Consequently, we systematically reviewed existing research findings on the impact of JD on economic growth. Combining these findings with the results of the earlier analysis regarding the pathways through which JD influences regional economic growth, we ultimately determined six model variables from key dimensions: economic growth, JD, labor force, capital, technology, and marketization, as illustrated in Table 2. These six variables span critical aspects of the economic growth research domain, aiming to accurately reflect the impact of JD on China’s economic growth.

Dependent variable

The GDP growth rate is selected to represent the level of economic growth across China’s provinces.

Core explanatory variable: JD levels for the 30 provinces in China are calculated from 2000 to 2019 based on the JD evaluation index system constructed in the previous section.

Control variables

According to the Cobb-Douglas production function, labor, capital, and technology are important variables that affect economic growth (F Reynès, 2019). Sufficient high-quality labor enhances human capital, driving enterprise productivity, innovation, and regional economic growth (Wijaya et al., 2021). Capital investment stimulates business expansion and infrastructure development, elevating regional output while boosting investment attractiveness (Pelinescu, 2015). Technological adoption accelerates production efficiency and industrial upgrading, strengthening global competitiveness and economic resilience (Asongu & Odhiambo, 2020). Collectively, these factors constitute fundamental drivers of regional economic advancement. Hence, this paper selects employment, total capital formation, and R&D personnel full-time equivalent as indicators for labor, capital, and technology. Currently, there is no authoritative data on capital stock indicators for various provinces in China. Existing research often uses the perpetual inventory method to estimate physical capital stock. However, different studies use different base periods for capital stock and depreciation rates, leading to significant differences in data (Kataoka and Mitsuhiko, 2013). Therefore, this paper uses total capital formation as the indicator for capital stock. On the other hand, when studying the specific situation in China, it is necessary to consider the impact of China’s market-oriented reforms on economic growth. The improvement in the level of marketization is usually accompanied by a freer, more open, and competitive market environment, promoting enhanced resource allocation efficiency, stimulating entrepreneurial and innovative vitality, enhancing enterprise competitiveness, and promoting regional economic growth (Chen et al., 2021). This paper draws on Xin’s research and selects the marketization index as the indicator to measure the level of marketization in China (Xin and Xin, 2017).

Baseline regression model construction

To empirically test whether JD has a non-linear impact on China’s economic growth, we first constructed a baseline regression model, as shown in Formula (1).

In this model, \({{\rm{GDP}}{\rm{GR}}}_{{\rm{it}}}\) denotes the GDP growth rate of province i in year t, serving as the dependent variable. \({{\rm{J}}{\rm{D}}{\rm{L}}}_{{\rm{it}}}\) is the core explanatory variable, capturing the level of JD in each region. \({{\rm{NEP}}}_{{\rm{it}}}\), \({{\rm{GCF}}}_{{\rm{it}}}\), \({{\rm{FERDF}}}_{{\rm{it}}}\) and \({{\rm{MI}}}_{{\rm{it}}}\) are control variables representing the number of employed persons, gross capital formation, full-time equivalent of R&D personnel, and the marketization index, respectively. The constant term is denoted by \(\alpha\). To account for unobservable time-invariant factors across provinces (e.g., institutional foundations, geographic conditions) and common shocks in specific years (e.g., national policies, macroeconomic fluctuations), we incorporate both province fixed effects \(({\mu }_{i})\) and year fixed effects \(({\lambda }_{t})\). The term \({\varepsilon }_{{it}}\) represents the idiosyncratic error. This model aims to identify the fundamental direction of the impact of JD on China’s economic growth, as well as to explore the potential existence of an inverted U-shaped relationship.

SYS-GMM model construction

Considering the potential bidirectional causal relationship between JD and economic growth—where robust judicial systems stimulate growth, while economic advancement enables greater investment in judicial capacity—the baseline empirical model likely suffers from endogeneity issues. Estimating this relationship using OLS or fixed effects methods may lead to biased coefficient estimates. To address this problem, we adopt the System Generalized Method of Moments (SYS-GMM) approach, which was proposed by Blundell and Bond. This method extends the Difference GMM by combining the level equation with the first-differenced equation, using lagged levels and lagged differences of the variables as instruments. SYS-GMM is particularly suitable for short panel data with dynamic structures, as it effectively mitigates the correlation between explanatory variables and the error term (Vitenu-Sackey and Acheampong, 2022). By introducing a lagged dependent variable, the SYS-GMM model is set as shown in Formula (2).

Here, \({{\rm{GDP}}{\rm{GR}}}_{{\rm{it}}}\) represents the one-period lag of the GDP growth rate, which captures the dynamic persistence of economic growth. The other variables retain the same definitions as in Eq. (1). The model continues to include province fixed effects and year fixed effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity and time-specific shocks. The introduction of the SYS-GMM approach enhances the causal inference of the regression analysis and serves as a robustness check against potential endogeneity, thereby improving the credibility and reliability of the estimation results.

Threshold regression model construction

To further examine whether JD exerts a significant non-linear threshold effect on economic growth—and to validate the robustness of the conclusions derived from the baseline and SYS-GMM models—this study introduces a threshold regression model proposed by Hansen, as shown in Formula (3) and (4) (Huang et al., 2018) .

In these formulas, \({\rm{JDL}}\) represents the threshold variable, and \({\rm{\eta }}\) denotes the threshold value. The threshold regression model is a statistical method used to study non-linear relationships between variables. The flexibility of the threshold regression model allows it to adapt to complex data structures. This model permits researchers to explore whether there is a threshold effect between variables. This is crucial for understanding situations where the relationship may change within a specific range of values. To ensure the robustness of threshold estimation, this study applies a non-parametric bootstrap method, repeating the sampling procedure 10,000 times to obtain an empirical distribution of the threshold and to test the statistical significance of the threshold effect. Through the construction and estimation of the threshold regression model, we can rigorously examine whether the relationship between JD and economic growth varies by stage, enhancing the credibility of the empirical findings and strengthening the study’s policy implications.

Data interpretation

Due to significant fluctuations in the economic growth of various provinces in China in 2020 and 2021, influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the substantial lack of data for the Tibet Autonomous Region, this paper focuses on the period from 2000 to 2019 and includes 30 provinces in China to investigate the impact of JD on economic growth. The data is sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook and the statistical yearbooks of each province, as well as the China National Legal Database. For missing data, interpolation and moving average methods were employed for supplementation. Adjustments for GDP and total capital formation were made using the Consumer Price Index. The data on the level of marketization is derived from the annual reports of the China Marketization Index, compiled by the Institute of National Economy Research of the China Economic Reform Research Foundation.

Results

Descriptive statistical analysis

This paper conducted descriptive statistical analysis on the six variables involved in the model, and the results are shown in Table 3. The difference between the maximum and minimum values of the six variables is relatively small. The skewness value is small, while the kurtosis value is large. This suggests that the distribution of the sampled data is relatively symmetric but has heavy tails. Additionally, the p-values for the JB (Jarque-Bera) statistics are all less than 0.05, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis. Thus, it can be concluded that none of the six variables follows a normal distribution.

Results of baseline regression model

Before conducting the baseline regression analysis, it is essential to determine whether a fixed effects model (FE) or a random effects model (RE) is more appropriate. The two models make different assumptions regarding individual heterogeneity in panel data; hence, a formal statistical test is necessary for model selection. This study applies the Hausman test to make this determination. As shown in Table 4, the Chi-square statistic is 67.32 with a corresponding p-value of 0.000, which strongly rejects the null hypothesis that the random effects estimator is consistent and efficient. Therefore, the fixed effects model is deemed superior, and all subsequent regressions are estimated accordingly.

The estimation results based on the fixed effects model are presented in Table 5. The R-squared value of 0.885 suggests that the selected explanatory variables explain a substantial proportion of the variation in economic growth rate, indicating a good overall fit.

From the perspective of the core explanatory variables, the coefficient of \({{\rm{J}}{\rm{D}}{\rm{L}}}_{{\rm{it}}}\) is positive, while that of \({{\rm{JD}}{\rm{L}}}_{{\rm{it}}}^{2}\) is negative, both significant at 5%. This indicates a significant inverted U-shaped relationship between the level of JD and economic growth. In the early stages of JD, the gradual improvement of the judicial system leads to more efficient resolution of commercial disputes, more effective enforcement of contracts, and stronger protection of property rights. These enhancements safeguard the legitimate interests of enterprises and residents, improving economic efficiency, boosting business confidence, and encouraging increased investment, innovation, and production expansion, which together enhance regional economic dynamism. Moreover, improvements in JD strengthen China’s competitiveness in the global economic landscape by attracting more foreign investors, thereby injecting new momentum into the country’s economic growth. In addition, a more developed judicial system contributes to social stability by reducing conflict and dissatisfaction, thus fostering a more productive environment for both businesses and individuals. However, when the level of JD surpasses a certain threshold, its positive effect on economic growth begins to diminish and may even become negative. This turning point can be attributed to several factors. First, an excessively developed judicial system may place undue emphasis on legal procedures, creating rigidities that constrain business flexibility and innovation. Second, the costs associated with legal services may rise sharply, increasing the financial burden on firms and households. Lastly, as judicial institutions mature, the government may shift its focus toward sustainable development, which can lead to the curtailment of investments and capital flows that do not align with long-term sustainability goals, thereby reducing the growth momentum of the regional economy.

Further analysis reveals that the turning point in the relationship between JDL and GDPGR occurs when JDL reaches 0.684. That is, when JDL exceeds 0.684, the marginal impact of JD on economic growth turns negative—indicating diminishing returns or even inhibitory effects of excessive JD. A spatiotemporal analysis of 30 Chinese provinces shows that the top five provinces in terms of JDL are Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, Guangdong, and Jiangsu. These regions are also among the most economically developed areas in China, having achieved rapid growth by leveraging policy advantages, geographical positioning, and early-stage reform initiatives. However, with the side effects of early growth—such as environmental degradation and emerging property rights disputes—these provinces have shifted their judicial focus toward protecting regional environments, intellectual property rights, and personal privacy. As JDL exceeds the threshold of 0.684, the GDPGR in these regions has shown a notable decline. Taking Jiangsu Province as a case study, in 2000, Jiangsu’s JDL stood at 0.414 with a GDPGR of 0.106. As JD improved, GDPGR also rose, peaking in 2008 when JDL reached 0.556 and GDPGR hit 0.149. However, beyond this point, further increases in JDL were associated with declining GDPGR. By 2019, JDL had risen to 0.726, while GDPGR dropped to 0.059. This declining trend may stem from institutional friction and rising governance costs associated with excessive judicialization. On one hand, as the rule of law is strengthened, legal procedures have become increasingly complex, and compliance requirements have become more stringent. This has imposed greater institutional constraints on firms’ financing, expansion, and innovation activities. In Jiangsu, for instance, enterprises seeking to engage in land transfers, environmental approvals, or IP-related expansions often face multiple layers of judicial review and burdensome document verification processes, which significantly lengthen investment cycles and raise transaction costs. According to the China SME Development Report (2022), about 62% of manufacturing SMEs in Jiangsu cited legal and regulatory requirements as a major obstacle to their expansion. On the other hand, the market mismatch between the supply and demand of legal services has become increasingly pronounced. High-quality legal resources tend to be concentrated in large enterprises, while SMEs face high service costs and access barriers. In cities like Nanjing and Suzhou, the rising fees of well-established law firms have compelled ordinary enterprises to allocate substantial financial and human resources to legal compliance, contracts, and arbitration, undermining their operational flexibility and capital efficiency. Furthermore, there is evidence of diminishing marginal returns on judicial resource allocation. That is, increased judicial investment has not always translated into proportional improvements in judicial performance. Although Jiangsu has advanced initiatives such as smart courts and one-stop diversified dispute resolution platforms, persistent challenges—such as a shortage of grassroots judges and poor interdepartmental system interoperability—have led to slower case processing and redundant workloads, creating a paradox of high quality but low efficiency. In regions with advanced judicial systems, these institutional frictions are particularly evident. They not only raise the cost of institutional operation but also erode the marginal momentum of economic growth, signaling the need for greater moderation, coordination, and efficiency in the future development of the rule-of-law environment.

Regarding the control variables, the coefficient of NEP is significantly positive, indicating that an expansion in employment scale contributes to economic growth. The increase in labor supply directly enhances regional production efficiency and output levels. Similarly, GCF exhibits a significantly positive coefficient, suggesting that capital accumulation remains a key driver of China’s economic growth, as it provides sufficient production funds for enterprises, improves infrastructure, and enhances investment attractiveness. The coefficient of MI is also significantly positive, implying that a higher degree of marketization facilitates more efficient resource allocation, promotes the rational flow of production factors, and thus stimulates economic growth. In contrast, the coefficient of FERDP is negative and significant at the 10% level, suggesting that technological input in some regions has not yet translated effectively into economic output, indicating a mismatch between input and output. This reflects the fact that the effectiveness of innovation-driven growth still needs further improvement.

In summary, the baseline regression model not only confirms a significant non-linear inverted U-shaped relationship between JD and economic growth, but also highlights multiple structural drivers of economic growth. These findings provide a robust empirical foundation for the subsequent use of the SYS-GMM model and threshold regression to conduct robustness and heterogeneity checks.

Endogeneity test

Considering the potential bidirectional causality between JD and economic growth—where economic growth may also drive judicial resource allocation and institutional reforms—this study addresses endogeneity concerns by employing the SYS-GMM based on the baseline model. The regression results are presented in Table 6.

From the perspective of model validity, firstly, the coefficient of the dynamic term \({{\rm{GDPGR}}}_{{\rm{it}}-1}\) is 0.163 and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating the presence of inertia in economic growth and thus justifying the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable in the model. Secondly, the SYS-GMM estimation passes relevant diagnostic tests: the AR(1) test yields a p-value less than 0.05, indicating first-order serial correlation in the residuals, which is a common and acceptable feature in dynamic panel models. The AR(2) test has a p-value greater than 0.1, suggesting no evidence of second-order serial correlation, thereby satisfying a key assumption for the validity of the SYS-GMM approach. Additionally, the Hansen test for overidentifying restrictions yields a p-value greater than 0.1, indicating that the instruments used are valid and there is no issue of overidentification, thus supporting the reliability of the SYS-GMM estimates.

Regarding the regression results, the coefficient on JDL is positive while its squared term is negative, both significant at the 5% level. This again confirms the significant non-linear inverted U-shaped relationship between JD and economic growth. It suggests that JD has a positive and significant promoting effect on economic growth at early stages, but when JD surpasses a certain threshold, its marginal effect on growth diminishes and eventually turns negative, consistent with the conclusions of the baseline regression model. Among the control variables, the coefficients of NEP and GCF are positive and significant at the 5% and 10% levels, respectively, further affirming the critical roles of labor and capital inputs in driving economic growth. The coefficient on MI is also positive and highly significant at the 1% level, indicating that improved market mechanisms substantially enhance resource allocation efficiency and economic dynamism. Notably, the coefficient on FERDP is negative but statistically insignificant, reflecting potential inefficiencies in the input-output conversion of technological investments in some regions of China. This highlights the need for further policy measures aimed at optimizing innovation resource allocation and improving technology commercialization efficiency.

In summary, the SYS-GMM estimation results maintain the robustness of the core findings after addressing endogeneity, fixed effects, and dynamic characteristics, strengthening the causal inference of the empirical analysis in this study.

Robustness test

To further verify the non-linear effects of JD on economic growth in China and to examine the robustness of the inverted U-shaped relationship obtained from the baseline regression and SYS-GMM models, this study introduces a threshold regression model for extended analysis. The threshold regression model effectively captures non-linear mechanisms by identifying structural breaks in the explanatory variable at specific threshold values, serving as an important supplement and validation to the previous models. A critical step in the threshold model setup is the selection of the optimal number of thresholds, which directly affects the model’s fit and explanatory power. Following Hansen’s bootstrap methodology, this study tests single, double, and triple-threshold specifications for the threshold variable JDL, conducting significance tests for each case. The bootstrap procedure is repeated 10,000 times to ensure the robustness of the test results. The relevant test outcomes are summarized in Table 7.

As shown in Table 7, the single-threshold model for JDL yields a highly significant F-statistic of 92.34 (p = 0.000), confirming a structural break in JD’s economic impact at a critical threshold. Conversely, double- and triple-threshold specifications show statistically insignificant results (p = 0.269 and p = 0.563, respectively), strongly rejecting the need for additional thresholds. Therefore, this study adopts the single-threshold model as the final threshold specification. The threshold value is further estimated using the bootstrap method, and the results are presented in Table 8.

According to the estimation results, the threshold value for JDL is 0.645, with a relatively narrow confidence interval, indicating a precise estimate and good statistical properties. The detailed regression results of the threshold model are shown in Table 9.

According to the regression results, when the JDL is below the threshold value of 0.645, the coefficient is 1.027 and statistically significant at the 1% level. This indicates that JD significantly stimulates economic growth during its early stages. However, once the JDL exceeds the threshold of 0.645, the relationship reverses—the coefficient becomes −0.637 (significant at 1%), suggesting excessive institutionalization imposes net economic costs. This inflection point confirms an inverted U-shaped relationship between JD and economic growth. These findings provide further evidence of the inverted U-shaped relationship between JD and economic growth. As for the control variables, both NEP and GCF continue to exert positive effects on economic growth, reaffirming the critical role of labor and capital in supporting China’s economic expansion. MI, however, exhibits a negative coefficient, which may imply a potential tension between market mechanisms and institutional constraints in regions with higher levels of the rule of law. Although the coefficient for FERDP is negative and not statistically significant, it may reflect the limited short-term economic returns of technological investment. In summary, the results of the threshold regression are highly consistent with those of the baseline and SYS-GMM models, further confirming the non-linear inverted U-shaped impact of JD on economic growth. This consistency strengthens the robustness and credibility of the empirical findings presented in this study.

Heterogeneity analysis

To further investigate whether the impact of JD on economic growth varies across regions, this study considers China’s significant regional disparities. Based on the classification criteria of the National Bureau of Statistics, the 30 provinces in mainland China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) are divided into three major regions: Eastern, Central, and Western. Fixed effects models are constructed separately for each region to examine the heterogeneity in the relationship between JD and economic growth. Building upon the baseline model, we estimate the effects of both the linear and quadratic terms of JDL on regional economic growth within each region, comparing the degree of nonlinearity, marginal effects, and statistical significance. The regression results are presented in Table 10.

Based on the regression results, an inverted U-shaped relationship between JD and economic growth is observed across all three regions, though the shape of the curve and the level of statistical significance differ notably.

First, in the Eastern region of China, the coefficient of JDL is 1.103 and significant at the 1% level, while the coefficient of its squared term is −0.841, significant at the 5% level. This indicates that the non-linear effect of JD on economic growth is most pronounced in the East, forming a typical and highly significant inverted U-shaped relationship. This suggests that in the early stages, judicial reform and institutional development in the East provided strong legal support for economic activities, significantly improving the business environment and the efficiency of resource allocation. However, as the judicial system reaches a higher level of development, excessive judicial intervention and rising enforcement costs may begin to suppress enterprise innovation and investment enthusiasm, leading to a decline in marginal benefits. Second, in the Central region, the coefficients of JDL and its squared term are significant at the 5% and 10% levels, respectively, also showing a clear inverted U-shaped structure. This implies that the JD in the Central region similarly exhibits a non-linear mechanism in promoting economic growth. However, the marginal effects are relatively weaker compared to the East. This may be due to the less mature market mechanisms and relatively lagging institutional environments in the Central region, which limit the full realization of institutional dividends from JD. Lastly, in the Western region, the coefficient of JDL is 0.592 and significant at the 10% level, while its squared term, although negative, is not statistically significant. This indicates that JD in the West still exerts a positive effect on economic growth, and no significant diminishing or restraining effect is observed yet. This may reflect the underdeveloped judicial foundation and the ongoing catch-up in legal infrastructure in the Western region, where improvements in the legal system are still a driving force for growth rather than a constraining factor.

As for the control variables, both NEP and GCF show consistently positive and significant effects across all three regions, confirming that labor input and capital accumulation remain fundamental drivers of regional economic growth. The MI variable is significantly positive in both the Eastern and Central regions, indicating that deeper marketization enhances resource allocation efficiency and strengthens economic performance. However, MI is not significant in the Western region, possibly because market mechanisms there have not yet assumed a dominant role. The FERDP variable shows mixed results, with a negative and marginally significant coefficient in the East, suggesting that the short-term returns on technological investment remain limited even in more developed regions.

In summary, the relationship between JD and economic growth exhibits significant regional heterogeneity. The Eastern region demonstrates a completely inverted U-shaped curve, characterized by the phases of JD, promotion, excess, and suppression. The Central region also displays a non-linear pattern, though its inflection point is less clearly defined. In contrast, the Western region is still in a phase of reaping the growth dividends of JD, without evident signs of institutional constraints. These heterogeneous outcomes highlight that the impact of JD on economic growth is not uniform across regions. Therefore, judicial reform and institutional strategies should be tailored to local conditions. In the East, efforts should focus on balancing judicial intensity with legal efficiency. In the Central region, improving the allocation of judicial resources and optimizing institutional environments are essential. Finally, the Western region should prioritize the strengthening of judicial infrastructure and legal safeguards to fully unleash institutional dividends and support the realization of regional coordination and development goals.

Discussion

This study employs a range of econometric techniques—fixed effects models, system GMM (SYS-GMM), and threshold regression—to establish robust evidence of an inverted U-shaped relationship between judicial development and economic growth. The consistent results across methodologies collectively confirm this non-linear pattern is not an artifact of model specification or sampling bias, but rather an inherent characteristic of China’s institutional-economic evolution. Moreover, the threshold regression model identifies a critical turning point in JD at a value of 0.645, providing empirical support for the theoretical notion of “moderate judicial intervention.” The regional heterogeneity analysis further reveals that the inverted U-shaped structure is most pronounced in the eastern region, followed by the central region, while the western region has yet to exhibit any marginal inhibitory effects. This indicates that the impact of JD on economic growth is both stage-dependent and region-specific. The institutional dividends associated with JD are not released simultaneously across regions; instead, they are constrained by factors such as economic foundations, market maturity, and legal infrastructure. These findings underscore the asymmetric and lagging nature of institutional effects, enriching the theoretical landscape of institutional economics by offering insights into how institutional quality influences economic growth. They also provide an empirical basis for regionally differentiated institutional supply strategies.

Compared with existing research, this study contributes meaningfully—and even breaks new ground—in the current literature. Prior studies generally emphasize the positive effects of judicial improvement on economic growth. For instance, Albanese et al. highlight the role of sound legal environments in fostering capital formation and economic prosperity, while Busch and Pelc, from a political economy perspective, stress the foundational importance of the rule of law in sustaining long-term growth (Albanese and Sorge, 2011; Busch and Pelc, 2010). However, these studies typically rest on a monotonic linear assumption that greater institutional development leads to higher growth. By contrast, this paper is among the first to systematically identify an inverted U-shaped effect of JD—a specific subdimension of institutions—on economic growth. This demonstrates an optimal institutional development threshold beyond which excessive legalization induces efficiency losses and suppresses market vitality—a significant advancement in institutional theory. Furthermore, this study extends the discourse on non-linear governance effects (Haans et al., 2015) by applying a judicial lens. Its variable construction and mechanism interpretation explicitly align with China’s institutional reform trajectory, offering context-specific theoretical grounding. Furthermore, echoing the findings of Zhu et al. regarding the differentiated release of market reform dividends across regions, this study argues that institutional dividends from the judicial system are likewise phased and regionally progressive (Zhu et al., 2018). This perspective further enriches the analytical framework on the relationship between institutional development and economic performance in China. In summary, this study not only achieves multidimensional validation in terms of methodology but also puts forward a novel theoretical proposition of “institutional moderation,” challenging the conventional view that more institutionalization always equates to better outcomes. It offers a new analytical perspective and policy reference point for understanding the tension and balance between high-quality rule-of-law construction and high-quality economic development.

Conclusions and suggestions

Conclusions

This paper systematically evaluates the impact of JD on China’s economic growth by integrating fixed effects models, SYS-GMM estimation, and threshold regression models. The empirical findings demonstrate a high degree of consistency and robustness. The analysis reveals a significant non-linear inverted U-shaped relationship between JD and economic growth: while JD initially promotes economic expansion, its marginal benefits diminish beyond a certain point and eventually become counterproductive. The threshold regression model identifies this critical turning point at a JD index value of 0.645, which passes statistical significance at the 1% level. When the level of JD falls below this threshold, it has a strong positive effect on GDP growth, reflecting the beneficial role of institutional optimization in improving the business environment, protecting property rights, and enhancing market confidence. However, once JD exceeds the threshold, the estimated coefficient turns negative (−0.637), indicating that excessive legalization—characterized by procedural rigidity, rising transaction costs, and market constraints—may weaken economic vitality. The estimated coefficients of control variables also align with theoretical expectations: NEP, GCF, and MI all exert significant positive effects, while the FERDP shows a negative effect in some regions, likely due to low conversion efficiency. Furthermore, regional heterogeneity analysis reveals that the inverted U-shaped structure is most pronounced in the eastern region, indicating that JD has entered a phase of marginal institutional suppression. The central region also exhibits a non-linear pattern, though the threshold is less clearly defined, while the western region remains in the early stage where judicial improvements continue to release institutional dividends and foster economic growth. Additionally, the SYS-GMM model effectively addresses potential endogeneity concerns, with diagnostic tests supporting model validity. The threshold regression, estimated via the Bootstrap method, further confirms the robustness of the model specification. These results collectively validate the reliability of the paper’s core conclusions. Overall, this study provides new empirical evidence on the complex mechanisms through which JD influences economic growth. It offers valuable insights for policymakers seeking to strike a balance between advancing the rule of law and sustaining economic dynamism in the context of high-quality development.

Policy recommendations

Based on the empirical findings of this study—specifically the inverted U-shaped non-linear relationship between JD and economic growth, along with pronounced regional heterogeneity and stage-specific characteristics—this section proposes six targeted and actionable policy recommendations. These aim to support localized judicial reform efforts across China and foster a more optimized, law-based business environment.

First, developed provinces should shift from expansion-oriented judicial construction to quality-oriented governance. For regions such as Jiangsu, Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangdong—where JD has surpassed the optimal threshold—there is a need to guard against the risks of over-judicialization, including procedural rigidity, redundant resource allocation, and rising compliance costs. These areas should prioritize procedural streamlining and the digital transformation of the judiciary by promoting smart courts, electronic service of process, and online adjudication to reduce litigation costs. Additionally, structural improvements in judicial services are crucial, such as establishing judicial risk assessment mechanisms for enterprises, providing tailored compliance guidance for SMEs and foreign-invested firms, and enhancing policy transparency and predictability. Cities like Beijing and Shanghai could further expand the role of intellectual property (IP) courts and develop indicator systems to evaluate judicial independence, credibility, and public trust, thereby advancing from institutional expansion to refined governance.

Second, regions at the judicial threshold should strengthen institutional enforcement and governance efficiency. Provinces in central China, such as Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, and Chongqing, are approaching the identified JD threshold but still face constraints in institutional capacity and grassroots governance. These regions should focus on capability-driven reforms by refining judge selection and training mechanisms and improving the professional competencies of local judicial personnel. Moreover, investments in judicial informatization should be enhanced to increase trial transparency. In line with regional industrial strategies, specialized commercial courts or enterprise service centers can be established in industrial parks and high-tech zones. For example, Wuhan’s East Lake High-Tech Zone may consider developing fast-track IP courts or mediation centers for technology contract disputes, thereby supporting the growth of tech-driven enterprises and upgrading the regional legal-business ecosystem.

Third, underdeveloped regions should focus on foundational legal infrastructure and capacity support. Western provinces such as Gansu, Qinghai, Guizhou, Yunnan, and Tibet remain in the early stages of JD, with institutional dividends yet to be fully realized. These regions should prioritize resource equalization and foundational capacity-building. Policy support could include increased central government fiscal transfers and innovative systems such as remote trials, circuit courts, and centralized cross-regional case adjudication to address the uneven distribution of judicial resources. A cross-regional support mechanism pairing eastern, central, and western judicial institutions should be established to promote regularized judge training, case-sharing, and professional exchange, thus strengthening legal safeguards in frontier areas and better serving rural revitalization and regional coordinated development strategies.

Fourth, strengthen regionalized development of IP judicial systems to enhance legal support for innovation-driven economies. Eastern innovation hubs such as Shenzhen and Hangzhou should further professionalize and internationalize IP adjudication. For instance, Shanghai could establish collegial panels for foreign-related IP cases, while manufacturing hubs like Suzhou and Ningbo might set up fast-track arbitration systems and IP mediation centers to provide efficient judicial responses to emerging industries. In central and western regions, efforts should be made to build IP judicial capacity through mechanisms such as technical expert advisory systems, cross-regional case databases, and specialized judicial training programs, addressing institutional weaknesses and improving overall IP protection efficiency.

Fifth, establish enterprise-oriented judicial service matching mechanisms to mitigate institutional transaction costs. To avoid the negative externalities of judicial complexity on business operations, a low-threshold, low-cost, and high-efficiency judicial service system should be developed. Courts at all levels should establish legal service windows and compliance advisory offices for enterprises, offering integrated services such as pre-litigation consultation, compliance counseling, and expedited mediation. Judicial service stations may also be piloted in key industrial zones, free trade zones, and innovation parks. For instance, Guangzhou could explore establishing a “technology court” in its Knowledge City to serve AI and pharmaceutical clusters, while Chengdu could develop a smart compliance platform in Tianfu New Area to align precision judicial services with enterprise needs.

Sixth, develop a regionally differentiated JD appropriateness assessment mechanism to guide adaptive institutional evolution. Given the threshold effects identified in the empirical analysis, it is recommended that a national-level index system be established to evaluate the appropriateness of JD. This system should include indicators such as the JD index, case enforcement rates, public satisfaction levels, and institutional compliance costs, with regular publications of provincial judicial efficiency and economic coordination indices. Such an index could serve as a reference for resource allocation and reform pacing. For example, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), in collaboration with the Supreme People’s Court and the Ministry of Justice, could issue a regional JD green paper. The report would offer development strategies for sub-threshold regions and optimization paths for over-threshold regions, enabling differentiated governance through strengthening fundamentals, adjusting structures, and managing boundaries, ultimately promoting a dynamic equilibrium between JD and economic growth.

Limitations and future recommendations

Despite systematically investigating the non-linear impact of JD on economic growth from both theoretical and empirical perspectives, and enhancing the robustness of the results through various econometric methods—including fixed effects models, SYS-GMM models, and threshold regression models—this study still has several limitations. First, regarding variable selection, although the JDL was constructed based on dimensions such as the number of judicial personnel, resource allocation, and case-handling efficiency, it remains insufficient to fully capture the actual operational quality and underlying institutional environment of the judiciary. Critical but difficult-to-quantify aspects such as judicial transparency, independence, impartiality, and public trust have not been included, which may lead to omitted variable bias. Second, this study relies on province-level panel data. While it reveals the overall relationship between JD and economic growth across regions, it does not cover more granular administrative units such as municipalities or counties. This limits the ability to deeply analyze the local heterogeneity of institutional effects and underlying mechanisms. Furthermore, the averaging nature of provincial data may obscure the true impact of judicial policies. Third, although the dataset spans a relatively long period from 2000 to 2019—facilitating the analysis of general trends—the study does not explicitly account for critical policy shifts, such as the comprehensive deepening of reforms in 2013 or the reform of the judicial accountability system in 2018, which may introduce potential policy interference.

Future research can further expand and refine this topic in several directions. On the one hand, more granular and dynamic indicators of judicial performance—such as trial duration, the composition of judicial expenditures, or case enforcement rates—can be introduced to better characterize the functioning of judicial institutions. Additionally, natural language processing (NLP) techniques can be employed to extract semantic features from court rulings and other legal texts, offering deeper insights into actual judicial behavior. On the other hand, empirical analyses can be conducted at the municipal or county level, incorporating enterprise-level survey data or publicly available judicial datasets. This would facilitate the examination of how judicial institutions influence regional economic performance through micro-level behavioral mechanisms such as investor expectations and corporate decision-making. Moreover, future studies may explore the interaction between JD and other institutional variables (e.g., regulatory strength, corruption control), as well as the heterogeneous mechanisms through which the judiciary impacts economic growth under different stages of development or industrial structures. These efforts would contribute more actionable policy recommendations for advancing rule-of-law-based high-quality development.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Albanese G, Sorge MM (2011) The role of the judiciary in the public decision-making process. Econ Polit 24(1):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0343.2011.00390.x

Asongu SA, Odhiambo NM (2020) Foreign direct investment, information technology and economic growth dynamics in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommun Policy 44(1):101838. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00258-0

Busch ML, Pelc KJ (2010) The politics of judicial economy at the World Trade Organization. Int Organ 64(2):257–279. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818310000020

Butkiewicz JL, Yanikkaya H (2006) Institutional quality and economic growth: maintenance of the rule of law or democratic institutions, or both? Econ Model 23(4):648–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2006.03.004

Chang J, Ren H (2018) The powerful image and the imagination of power: the ‘new visual turn of the CPC’s propaganda strategy since its 18th National Congress in 2012. Asian J Commun 28(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2017.1320682

Chemin M (2009) The impact of the judiciary on entrepreneurship: evaluation of Pakistan’s “Access to Justice Programme. J Public Econ 93(1-2):114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.05.005

Chemin M (2012) Does court speed shape economic activity? Evidence from a court reform in India. J Law Econ Organ 28(3):460–485. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewq014

Chen ST, Lee CC (2005) Government size and economic growth in Taiwan: a threshold regression approach. J Policy Model 27(9):1051–1066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2005.06.006

Chen T, Lu H, Chen R et al. (2021) The impact of marketization on sustainable economic growth—evidence from West China. Sustainability 13(7):3745. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073745

Coşkun Y, Seven Ü, Ertuğrul HM et al. (2017) Capital market and economic growth nexus: evidence from Turkey. Cent Bank Rev 17(1):19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbrev.2017.02.003

Di Vita G, Di Vita F, Cafiso G(2019) The economic impact of legislation and litigation on growth: a historical analysis of Italy from its unification to World War II J Institut Econ 15(1):121–141. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137417000583

Dong X, Voigt S (2022) Courts as monitoring agents: the case of China. Int Rev Law Econ 69:106046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2022.106046

Ginsburg T (2000) Does law matter for economic development? Evidence from East Asia. Law Soc Rev 34(3):829–856. https://doi.org/10.2307/3115145

Glaeser EL, La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F et al. (2004) Do institutions cause growth? J Econ Growth 9:271–303. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEG.0000038933.16398.ed

Haans RFJ, Pieters C, He ZL (2015) Thinking about U: theorizing and testing U- and inverted U-shaped relationships in strategy research. Strateg Manag J 37(7):1177–1195. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2399

Haidar JI (2012) The impact of business regulatory reforms on economic growth. J Jpn Int Econ 26(3):285–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2012.05.004

Huang J, Qiang L, Cai X et al. (2018) The effect of technological factors on China’s carbon intensity: New evidence from a panel threshold model. Energy Policy 115:32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.12.008

Ip EC (2012) Judicial review in China: a positive political economy analysis. Rev Law Econ 8(2):331–366. https://doi.org/10.1515/1555-5879.1598

Ippoliti R, Melcarne A, Ramello GB (2015) Judicial efficiency and entrepreneurs’ expectations on the reliability of European legal systems. Eur J Law Econ 40:75–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-014-9456-x

Jappelli T, Pagano M, Bianco M (2005) Courts and banks: effects of judicial enforcement on credit markets. J Money Credit Bank 223–244. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3838925

Kaplow L (1986) An economic analysis of legal transitions. Harvard Law Rev 509–617. https://doi.org/10.2307/1341148

Kataoka Mitsuhiko (2013) Capital stock estimates by province and interprovincial distribution in Indonesia. Asian Econ J 27(4):409–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/asej.12021

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Zoido P (1999) Aggregating governance indicators. Soc Sci Electron Publ 87(2):2195. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.188548

Khan SAR, Zhang Y, Anees M et al. (2018) Green supply chain management, economic growth and environment: a GMM based evidence. J Clean Prod 185:588–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.226

Lu SF, Yao Y (2009) The effectiveness of law, financial development, and economic growth in an economy of financial repression: evidence from China. World Dev 37(4):763–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.07.018

Marciano A, Melcarne A, Ramello GB (2019) The economic importance of judicial institutions, their performance and the proper way to measure them. J Institut Econ 15(1):81–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137418000292

Martínez-Alier J (2012) Environmental justice and economic degrowth: an alliance between two movements. Capital Nat Social 23(1):51–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2011.648839

Melcarne A, Ramello GB (2015) Judicial independence, judges’ incentives and efficiency. Rev Law Econ 11(2):149–169. https://doi.org/10.1515/rle-2015-0024

Messick RE (1999) Judicial reform and economic development: a survey of the issues. World Bank Res Observ 14(1):117–136. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/14.1.117

Nguyen HH (2020) Impact of foreign direct investment and international trade on economic growth: empirical study in Vietnam. J Asian Financ Econ Bus 7(3):323–331. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no3.323

Obere A, Thuku GK, Gachanja P (2013) The impact of population change on economic growth in Kenya. 2013. http://Hdl.Handle.Net/123456789/2234

Pelinescu E (2015) The impact of human capital on economic growth. Procedia Econ Financ 22:184–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00258-0

Reynès F (2019) The Cobb–Douglas function as a flexible function. Math Soc Sci 97:11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mathsocsci.2018.10.002

Samuels WJ (1971) Interrelations between legal and economic processes. J Law Econ 14(2):435–450. https://doi.org/10.1086/466717

Shen Y, Liao K (2022) An application of analytic hierarchy process and entropy weight method in food cold chain risk evaluation model. Front Psychol 13:825696. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.825696

Vitenu-Sackey PA, Barfi R (2021) The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the global economy: emphasis on poverty alleviation and economic growth. Econ Financ Lett 8(1):32–43. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.29.2021.81.32.43

Vitenu-Sackey PA, Acheampong T (2022) Impact of economic policy uncertainty, energy intensity, technological innovation and R&D on CO2 emissions: evidence from a panel of 18 developed economies. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(58):87426–87445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-21729-2

Vitenu-Sackey PA, Oppong S, Bathuure IA (2022) The impact of green fiscal policy on green technology investment: evidence from China. Int J Manag Excell 16(3):2348–2358. https://doi.org/10.17722/ijme.v16i3.1251

Voigt S (2012) How to measure the rule of law. Kyklos 65(2):262–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2012.00538.x

Voigt S (2013) How (not) to measure institutions: a reply to Robinson and Shirley. J Institut Econ 9(1):35–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137412000240

Voigt S (2016) Determinants of judicial efficiency: a survey. Eur J Law Econ 42:183–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-016-9531-6

Wang Y, Li L (2024) Digital economy, industrial structure upgrading, and residents’ consumption: Empirical evidence from prefecture-level cities in China. Int Rev Econ Financ 92:1045–1058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2024.02.069

Wijaya A, Kasuma J, Darma DC (2021) Labor force and economic growth based on demographic pressures, happiness, and human development: Empirical from Romania. J East Eur Cent Asian Res. JEECAR) 8(1):40–50

Xiao K, Tamborski J, Wang X et al. (2022) A coupling methodology of the analytic hierarchy process and entropy weight theory for assessing coastal water quality. Environ Sci Pollut Res 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17247-2

Xin Z, Xin S (2017) Marketization process predicts trust decline in China. J Econ Psychol 62(oct.):120–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2017.07.001

Xinying J, Oppong S, Vitenu-Sackey PA (2019) The impact of personal remittances, FDI and exports on economic growth: evidence from West Africa. Eur J Bus Manag 11(23):24–32. https://doi.org/10.7176/EJBM

Zheng M (2023) China plans to strike a balance between socio-economic development and anti-COVID-19 policy: Report from the 20th National Congress of China. J Infect 86(2):154–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(22)00142-4

Zhu J, Fan C, Shi H, Shi L (2018) Efforts for a circular economy in China: a comprehensive review of policies. J Ind Ecol 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12754

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the General Project of Philosophy and Social Science Research in Jiangsu Universities in 2024, Project Name: Research on the Efficiency of New Quality Productivity for the Transformation and Upgrading of Jiangsu Manufacturing Industry under the Perspective of Total Factors (No. 2024SJYB1083).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, XZ and DT; methodology, XZ and XC; software, XZ; validation, XZ and XC; formal analysis, XZ, DT, and XC; investigation, XZ and XC; resources, XZ and DT; data curation, XZ, DT, and XC; writing—original draft preparation, XZ and XC; writing—review and editing, DT and XC; visualization, DT; supervision, DT; project administration, DT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Tang, D. & Cheng, X. The inverted U-shaped relationship between judicial development and economic growth: evidence from China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 948 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05338-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05338-1