Abstract

Research on ethical leadership predominantly emphasizes value-based virtues and value-driven behaviors; however, these aspects have not yet be adequately integrated. This paper aims to construct dimensions that enable a comprehensive and integrated understanding of ethical leadership. Drawing inspiration from Confucianism, which advocated ethical leadership, we propose the ‘Five Constant Virtues’ (Wuchang) as a framework for developing dimensions of ethical leadership. The Five Constant Virtues encompass both value-based virtues, (benevolence [Ren], righteousness [Yi], wisdom [Zhi], and integrity [Xin]), and value-driven behavior (ritual [Li]). These five dimensions interact synergistically, collectively empowering leaders to act ethically in a contextually appropriate manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leadership is defined as the process of inspiring and guiding individuals or organizations towards a common vision through influence, motivation, and ethical responsibility, serving as a key driving force for organizational success and social progress (Hogan and Kaiser 2005; Kouzes and Posner 2006; Dinh et al. 2014). In contrast to management, which primarily focuses on operational efficiency and task execution (Kotterman 2006), leadership emphasizes the integration of vision, motivation, and moral responsibility. The essence of effective leadership lies in virtues such as integrity, empathy, and justice, which enable leaders to build rust, foster ethical behavior, and navigate complex social dynamic (Palmer et al. 2001; Yukl 2013). In an era where governments, businesses, non-profit organizations, and religious institutions face increasing several moral crisis, the significance of ethical leadership becomes ever more pronounced (Brown et al. 2005; Webley and Werner 2008; Zhu et al. 2019). Numerous scholars have explored ethical leadership from behavior and virtue dimensions, (Brown and Trevino 2006; Kalshoven et al. 2011; Lawton and Paez 2015). However, the majority of current research on ethical leadership suffers from a redundancy of theory and empirical evidence, with few studies providing effective integration. Confucianism, as a philosophical system centered on ethics, primarily aimed at moral education, and oriented towards the construction of social order, offers a novel perspective on ethical leadership (Yuan et al. 2023). Therefore, the aim of this paper is to construct a comprehensive framework that integrates the various dimensions of ethical leadership, thereby providing a more holistic understanding of ethical leadership.

Ethical leadership encompasses the demonstration of moral behaviors and the establishment of a moral example by leaders, guided by ethical principles and values, while also involving the making of ethically sound decisions and inspiring team members to engage in ethical conduct, all accompanied by a strong sense of responsibility towers others and society, thereby fostering a more just and sustainable work environment (Brown and Trevino 2006). Existing research has focused on the conceptualization and measurement of ethical leadership (Trevino et al. 2000; Yukl et al. 2013). Recent empirical studies tend to examine the impact of ethical leadership on outcomes, such as employees job performance (Piccolo et al. 2010), innovation (Tu and Lu 2013), and subordinate behavior (Stouten et al. 2010). While Western leadership theories, such as servant leadership, moral leadership, and spiritual leadership (van Dierendonck 2011; Liden et al. 2014; Newstead et al. 2019) have enhanced the understanding of ethical leadership, they often lack a comprehensive integration of virtues and behaviors, particularly in corss-cultural contexts. For instance, ethical leadership emphasizes care and support for subordinates; however, the understanding of these concepts varies across cultures. In Western cultures, the emphasis may be on promoting individual development and the protection of rights, while in Eastern cultures, these notions also encompass moral guidance for subordinates and the instillation of collectivist values. In the era of globalization, scholars increasingly recognize the importance of cross-cultural understanding of ethical leadership (Chen et al. 2009; Resick et al. 2011; Zhu et al. 2019). Consequently, it is essential to explore ethical leadership from an Eastern cultural perspective that differs from Western leadership theories.

In China, the profound influence of Confucian culture renders ethical leadership particularly significant, with related concepts permeating all facets of leadership thought and practice (Chen et al. 2014; Ma and Tsui 2015). Rooted in the teachings of Confucius, Confucianism establishes a theoretical framework that emphasizes personal moral cultivation, social harmony, and benevolent governance (Woods and Lamond 2011). It posits that societal stability and development depend on individuals’ moral integrity and the quality of their social relationships. Within this ethical framework, “ren” (benevolence) is regarded as a core value, advocating that leaders should demonstrate genuine care and support for their subordinates to enhance team cohesion (Yuan et al. 2023). Concurrently, “yi” (righteousness) underscores the importance of justice and a sense of responsibility, requiring leaders to consider fairness and morality in their decision-making process to ensure that all decisions align with organizational interests while respecting employees’ fundamental rights and values (Tan 2024). The emphasis on moral and ethical considerations has permeated families, societies, and economic organizations, further reinforcing the public’s identification with Confucian culture. Additionally, Confucianism introduces the concept of “li” (ritual), which refers to appropriate behaviors and etiquette that promote harmony in interpersonal relationships (Yuan et al. 2023). Leaders who adhere to these rituals effectively demonstrate respect for their subordinates and their contributions, thereby enhancing loyalty and a sense of belonging within the team. In modern corporate management, leadership styles influenced by Confucian ethics have been widely practiced, with organizations incorporating insights from Confucian classics into employee training programs to cultivate moral character (McDonald 2012; Tan 2024). In terms of motivation, there is a strong emphasis on combining spiritual and material incentives. Furthermore, efforts are made to create a workplace culture characterized by harmony, respect, and mutual assistance, aligning with the values advocated by Confucianism (Wang et al. 2005; Schenck and Waddey 2017). Notably, the moral leadership concepts inherent in Confucian thought are also critically reflected in national governance, exemplified by the principle of “governing the nation with virtue” (Moore 2012). In the processes of public administration and corporate governance, leaders employ moral guidance and exemplary behavior to achieve effective governance outcomes. In the context of globalization, Confucian ethics provide a unique cultural perspective on modern leadership, enriching its conceptual framework and developmental pathways.

Some Western scholars have acknowledged the unique contributions of Confucian ethics to the study of ethical leadership that may be drawn from traditional Chinese culture (Riggio et al. 2010). However, ether has been limited effort to develop or extend mainstream Western perspectives on ethical leadership through the lens of Chinese culture (Hackett and Wang 2012). Therefore, this paper aims to construct dimensions of ethical leadership rooted in the principles of Chinese cultural thought. More specifically, we intend to articulate detailed dimensions of ethical leadership informed by values derived from Confucian philosophy.

Literature review

Conceptualization of ethical leadership

Since 2005, numerous studies on ethical leadership have emerged, conceptualizing it from various perspectives. Banks et al. (2021) categorized these conceptualizations into two main types: (a) behaviors that are both morally appropriate and effective leadership practices, as discussed by Wang and Hackett (2020), with relevant examples provided by Craig and Gustafson (1998), Brown et al. (2005), and Yukl et al. (2013); and (b) leadership behaviors that are virtue-based and well-intended, with examples from Riggio et al. (2010), Kalshoven et al. (2011), Newstead et al. (2019).

The most prevalent conceptualization of ethical leadership is defined by Brown and colleagues as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal action and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al. 2005, p.120). This definition highlights two critical dimensions of ethical leadership: the ethical leader’s identity as a ‘moral person’ and as a ‘moral manager’ (Brown and Trevion 2006). The moral person dimension refers to the ethical leader’s embodiment of and modeling ‘normatively appropriate’ behavior, characterized by fairness and honesty in relationships with others (Brown et al. 2005). Trevino et al. (2000) describe a ‘moral person’ as fair, ethically principled, caring and altruistic in decision-making. Brown and Trevino (2006) portray the moral person in terms of traits, attributes, and personal characteristics. Meanwhile, Brown et al. (2005) conceptualized the moral manager as a role model for ethical conduct - a leader who discusses ethical standards, values and principles with followers to encourage ethical behavior. Therefore, the notions of moral person and moral manager are each articulated through the lenses both virtue and ethical behavior.

Virtue in ethical leadership

The concept of virtue has become a central element in the understanding of ethical leadership (Hackett and Wang 2012; Storr 2004). Generally, virtue encompasses both moral and practical aspects, where the latter represents the behavioral manifestations of the former (Newstead et al. 2019). As a result, practical aspects of virtue can be developed (Peterson and Seligman 2004). Within ethical leadership studies, virtue has been examined from various angles, including character trait (Fry 2003; Hanbury 2004), personal values (Sama and Shoaf 2008), personality (Brown and Trevino 2006), and competencies (Bass 1990). For example, Arjoon (2000) defined virtue as a personal quality that motivates individuals to act for the common good, while Coloma (2009) described it as the norms or customary conduct guiding behavior.

Brown et al. (2005) indicated that ethical leader are expected to uphold the right actions. Newstead et al. (2019) characterized a virtuous leader as someone who consciously engages in doing what is right, for the right reasons and in the right manner. This illustrates that the ethical leader’s virtue comprises multiple characteristics. Furthermore, virtue serves as a moral foundation for the actions of a ‘good person’ and can often predict behavior in specific contexts (Broadie and Rowe 2002). Additionally, a leader’s virtue expressed spontaneously, independent of personal interests or external controls (Whetstone 2001). Moreover, a virtuous leader integrates knowledge and practice, not only understanding the right course of action but also implementing it (Ciulla 2004; Newstead et al. 2019). Ciulla (2004) emphasized that while values can exist without practical application, virtues must be concurrently expressed through both ideology and action. Philosophers like Confucius and Aristotle advocated for the development and maintenance of virtues through sustained learning and practice (Hackett and Wang 2012), leading a habitual actions that reflect virtue when circumstances arise (Bragues 2006).

The concept of the ‘right thing’ is context-dependent, meaning a leader’s virtue should be assessed according to specific situations. Context determines the prerequisites for each event-effective leadership characteristics may vary across organizations, and the interpretation and impact of a given behavior can differ depending on the circumstances (Johnson 2001). Thus, virtue can only be fully understood by considering the context in which actions are deemed virtuous (Whetstone 2001).

It is often stated that virtues guide ethical behavior (Hackett and Wang 2012). Yet, scholars have also identified more nuanced aspects of virtue, asserting that virtuous individuals consistently act rightly and find fulfillment in their ethical conduct (Irwin 1999; Cavanagh and Bandsuch 2002). Bright et al. (2014) suggested that cultivating and emphasizing the leader’s virtues can benefit team and organizational development. The role of leaders as key sources of ethical guidance for employees is another significant theme in ethical leadership studies (Brown et al. 2005). Trevino (1986) asserted that many employees seek moral guidance from their leaders, who often serve as a pivotal ethical references in the workplace (Brown et al. 2005).

Scholars have discussed specific virtues influencing ethical leadership, including trustworthiness, integrity, justice, temperance, courage, prudence, honesty, truthfulness, love, faithfulness, responsibility, authenticity, care and compassion (Gonzalez and Cuillen 2002; McCoy 2007; Walker et al. 2007). However, these studies lack integration. Integrity, a virtue prominently highlighted in the literature, is fundamental to ethical leadership (Keating et al. 2007). Badaracco and Ellsworth (1991) defined integrity as wholeness, coherence, and moral soundness, centering on honesty and justice. It encompasses both character traits and behaviors (Lawton and Paez 2015) and is central to ethical leadership practices (Den Hartog and De Hoogh 2009). Behavioral integrity is described as “the perceived pattern of alignment between an actor’s works and deeds” (Simons 2002, p.19). Palanski and Yammarino (2007) noted that integrity is typically accompanied by additional virtues, including fairness, trustworthiness, compassion and authenticity.

Measurement of ethical leadership

Another way to understand ethical leadership is through measurement of its manifestations. Ethical leadership theory emphasizes ethical leaders as role models who demonstrate behaviors that regulate the ethical conduct of their followers (Brown and Trevino 2006). To effectively explore the impact of ethical leadership, scholars have developed several instruments to capture its dimensions (Langlois et al. 2014; Riggio et al. 2010; Spangenberg and Theron 2005). For instance, Brown et al. (2005) created the Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS) to encompass the breadth of ethical leadership. Similarly, Spangenberg and Theron (2005) established the Ethical Leadership Inventory (ELI), which focuses on the creation and sharing of ethical vision. Additionally, Kalshoven et al. (2011) proposed the Ethical Leadership at work questionnaire (ELW) to measure ethical leadership behaviors, including power sharing, role clarification, ethical guidance and concern for sustainability.

Despite these efforts, existing studies on measuring ethical leadership are limited and often lack integration with one another. Researchers tend to construct scales based on their individual research interests and interpretations of ethical leadership, leading to the measurement of certain aspects while neglecting others. For example, the ELS, the most widely used measure of ethical leadership in empirical studies, was developed from a preliminary pool of 48 items selected by the authors (Brown et al. 2005). This lack of standardization can result in overlap and potential confusion among different scales. While many instruments assess integrity as a component of ethical leadership, they often employ varying definitions, which increases the likelihood of survey bias.

Confucianism and Confucian ethics

Confucianism, as one of the foundational traditions of Chinese philosophy, originated during the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period (~770–221 BCE). It was established by Confucius (551–479 BCE) and further developed by prominent thinkers such as Mencius, Xunzi, and later scholars during the Song and Ming dynasties (Yao 2000). This philosophical system is characterized by its ethical focus, placing significant emphasis on personal moral cultivation and social harmony, which extend to familial responsibilities and political governance (Hill 2006). Confucianism has profoundly influenced East Asian culture, shaping social norms, educational practices, and governance models (Weiming 2017). At the core of Confucian ethics is principle of “Ren”, often translated as benevolence or humaneness (Tan 2024). Ren symbolizes love, care, and compassion in human relationships, serving as the foundation for both personal moral refinement and societal harmony. Confucian ethics is further supplemented by “Yi” (righteousness), “Li” (Ritual), “Zhi” (wisdom), and “Xin” (Integrity), collectively forming a comprehensive moral framework that guides individual behavior and social interactions (Woods and Lamond 2011).

The influence of Confucian ethics spans various dimensions, including personal, familial, organizational, and societal, each interrelated and collectively reinforcing the ethical foundation of Chinese culture (Lin et al. 2013). Specifically, on an individual level, Confucian ethics advocates for the principles of self-cultivation and moral behavior, urging individuals to actively embody the virtue of ren in their daily lives (Ding et al. 2024). This emphasis on empathy not only facilitates a deeper understanding of others’ feelings and experiences but also empowers individuals to make more conscientious and ethically sound decisions, thus contributing to foster a positive societal impact. At the familial level, Confucianism steadfastly upholds the principles of filial piety and familial responsibility, thereby emphasizing the critical importance of mutual affection and respect among family members (Gu and Li 2023). The practice of filial piety compels individuals to exhibit a profound sense of care for their elders, serving as a foundational mechanism for preserving family harmony and continuity across generations. Additionally, Confucian doctrine accentuates the essential role of parents as moral exemplars, a dimension that is instrumental in fostering ethical awareness and cultivating a sense of responsibility in their children (Sheng 2019). Within organizational contexts, Confucian ethics advocates for a governance paradigm that is fundamentally anchored in virtue, emphasizing the imperative for leaders to embody noble moral qualities coupled with a profound sense of responsibility (Cottine 2016). It is crucial to recognize that employees are driven not solely by material incentives, but also by an intrinsic aspiration for respect and self-actualization, which are essential for holistic engagement in their roles (Liu and Ji 2019). Therefore, ethical leaders, who adeptly balance the dual objectives of fostering high performance and attending to employee well-being, play a pivotal role in enhancing both motivation and organizational cohesion. On a societal level, Confucian ethics establishes a framework centered on harmony and stability (Li 2006). It advocates for compromise and understanding in interpersonal relations and social conflicts. By promoting these values, Confucian ethics reinforces trust and cooperation among community members, contributing to societal cohesion and overall stability (Yuan et al. 2023). The holistic nature of Confucian ethics not only strengthens personal and social relationships but also cultivates a culture of ethical awareness that is deeply rooted in Chinese tradition, offering valuable insights applicable to modern leadership and organizational practices.

The Confucian ethics system and ethical leadership

To elucidate how Confucian ethics can enhance modern leadership, this paper proposes that Confucianism’s value system, particularly the “Five Constant Virtues”, provides a practical framework for ethical leadership. Confucianism envisions an ideal leader as a sage or a gentleman (chun tzu), embodying both virtue and competence. The Five Constant Values - ren (benevolence), yi (righteousness), li (ritual), zhi (wisdom), and xin (integrity) - from the core of Confucian ethics and remain relevant as a code of conduct for contemporary leaders (Wang and Chee 2011). Developed by Dong Zhongshu based on the teachings of Confucius and Mencius, these virtues encapsulate natural law and moral categorization widely recognized in Chinese culture (Huang 1997). The following sections explain each virtue, illustrating their practical application in modern leadership through concrete examples and in-depth analysis.

Ren (benevolence)

Ren (benevolence), the cornerstone of the Five Constants, embodies the principle of ‘loving your people’ (The Analects, Watson 2007). It aligns with Aristotelian notions of friendliness and the ethics of care (Hackett and Wang, 2012), emphasizing kindness, empathy, and interpersonal harmony. Grounded in loyalty (chung) and magnanimity (shu), benevolence guides leaders to treat others with sincerity and reciprocity, as reflected in the Confucian maxim: “Do not do to others what you would not have others do to you” (Lin et al. 2013).

In modern leadership, benevolence foster supportive work environment and societal impact. For instance, consider a technology firm’s CEO who implements flexible work policies to support employees’ mental health during a crisis. By prioritizing employee well-being over immediate productivity, the leader embodies ren, fostering loyalty and job satisfaction. Research by Chan (2008) supports this, showing that benevolent leaders create supportive climates, leading to higher employee satisfaction and organizational loyalty. Wang and Hackett (2016) further demonstrate that ren-inspired leadership predicts enhanced employee performance and organizational citizenship behaviors.

Externally, benevolence drives corporate social responsibility (CSR). A notable example is Zhang Yin, founder of Nine Dragons Paper, who integrated ren by investing in community welfare programs, such as education for underprivileged children. This not only enhanced the company’s reputation but also instilled employee pride, aligning with Ip’s (2009) findings that ren-driven leaders improve community development and estakeholder trust. Zhu et al. (2015) corroborate that benevolent leaders foster a culture of social responsibility, increasing employee engagement. These examples illustrate how ren enables leaders to balance organizational goals with societal needs, creating shared value through empathy and care.

Yi (righteousness)

Yi (righteousness) emphasizes morally appropriate actions over profit, as Confucius states, ‘A gentleman does not set his heart for or against anything in the world. He only does what is right.’ (The Analects, 4.10). Mencius reinforces this, prioritizing yi over gain: ‘Why must your Majesty use that word, “profit”? What I am provided with are counsels to benevolence and righteousness’ (Mencius, Book I, Part I, Chapter I). This virtue aligns with Aristotle’s justice and temperance (Hackett and Wang 2012), guiding leaders to uphold fairness and ethical boundaries.

In modern organizations, yi informs ethical decision-making. For example, a pharmaceutical company leader might refuse to inflate drug prices despite market pressures, prioritizing patient access over profit. This reflects yi by placing justice above financial gain, enhancing employee morale and public trust. Low and Ang (2013) found that yi-guided leaders prioritize employee welfare and environmental sustainability, fostering organizational cohesion and sustainable development. Brown et al. (2005) align yi with ethical leadership, noting that such leaders consistently ask, “what is the right thing to do, in terms of ethics?” (Mayer et al. 2010, p.8).

A real-world case is Paul Polman, former CEO of Unilever, who championed sustainability by reducing environmental impact despite short-term profit challenges. Polman’s commitment to yi inspired employees and strengthened Unilever’s reputation, as Lin et al. (2018) suggest that yi-driven leadership cultivates integrity and accountability. By prioritizing justice, leaders practicing yi motivate teams and align organizational goals with societal good, ensuring long-term viability.

Li (ritual)

Li (ritual) in Confucianism represents codes of appropriate behavior, serving as an external expression of inner virtue. Confucius stated, ‘A benevolent man will control himself in conformity with the rules of propriety. Once every man can control himself in conformity with the rules of propriety, the world will be in good order. Benevolence depends on oneself, not on others’ (The Analects 12.1). In modern contexts, li manifests as ethical norms that regulate leader-subordinate relationships, fostering respect and trust.

In practice, li guides leaders to model contextually appropriate behaviors that reflect ethical norms and foster organizational harmony. For example, a company CEO might institute regular “values alignment workshops” where employees collaboratively discuss and reinforce the organization’s ethical principles, such as fairness and mutual respect. This ritual embodies li by creating a structured platform for open dialog, demonstrating the leader’s commitment to transparency and inclusivity. By actively listening to employees’ perspectives and ensuring equitable participation, the leader strengthens employees’ sense of belonging and reinforces a culture of mutual respect. Islam and Zyphur (2009) found that such ethically grounded rituals enhance employees’ emotional attachment to the organization, fostering a sense of inclusion and community. Similarly, Brown et al. (2005) emphasize that behaviors rooted in li inspire trust and position leaders as role models, encouraging employees to emulate ethical conduct. These rituals reinforced ethical conduct, boosting employee engagement, as Khuntia and Suar (2004) note that li-related virtues (e.g., humility, respect) enhance team cohesion. By embedding li in organizational practices, leaders creat cultures of accountability and mutual respect, directly enhancing leadership effectiveness.

Zhi (wisdom)

Zhi (wisdom) involves knowledge accumulation and sound decision-making, as Confucius notes: ‘to admit what you know and what you do not know, that is knowledge’ (The Analects 2.17). Mencius adds that wisdom discerns right from wrong, guiding ethical choices. In leadership, zhi encompasses not only self-awareness and strategic insight but also continuous learning, exploration, and extensive practical experience necessary to make sound decisions and provide valuable guidance, ultimately enhancing workforce efficiency and fostering healthy interpersonal relationships (Liu and Ji 2019).

Wisdom stands as one of the core dimensions of ethical leadership, emphasising knowledge – of good and wrong, self-awareness, and understanding others. Ethical leaders leverage their wisdom to take initiative and express a genuine eagerness to learn, including humility in learning from other subordinates. They recognize their limitations and do not pretend to possess knowledge they lack. This competence enables ethical leaders to understand their subordinates’ strengths and weaknesses, thereby encouraging their development effectively. Practically, zhi enables leaders to navigate complex challenges. For example, a retail chain leader facing supply chain disruptions might use zhi to analyze market trends and employee capabilities, devising innovative solutions like local sourcing. Newstead et al. (2019) emphasize that zhi-driven leaders apply virtues contextually, enhancing decision-making efficacy.

Xin (integrity)

Xin (integrity), the alignment of actions with values, is central to Confucianism. Confucius question, ‘How can an untrustworthy man be employed?’ (The Analects 2.22), and further advises:, ‘[if you are] sincere in what you say and trustworthy in what you do, you would behave well even among uncivilized tribes. Insincere in word and untrustworthy in deed, could you behave well in your native village?’ (The Analects 15.6). xin, encompassing honesty and trustworthiness (Bauman 2013), is vital for fostering trust in leadership.

In modern contexts, xin serves as a pivotal attribute of ethical leadership. Ethical leaders demonstrate xin in their interactions with subordinates and when making decisions on their behalf. Keeping promises is crucial for building trust and establishing healthy interpersonal relationships, which consequently create an environment rich in integrity. Furthermore, ethical leaders empower their subordinates by granting them with autonomy and supporting their professional growth, thereby cultivating a more engaged and committed workforce.

Additionally, xin requires self-honesty. Ethical leaders naturally embody automatically, acting transparently in alignment with their beliefs and values, as noted by Avolio et al. (2004). This authenticity goes beyond merely possessing values; it involves actively enacting them in daily practices. An ethical leader earns trust not only by fulfilling promises but also by consistently upholding values, regardless of personal costs. By embodying xin, leaders foster an environment of autonomy and support, significantly enhancing employee commitment and improving the organization’s reputation. These practices highlight the practical value of xin in modern leadership, demonstrating that xin is essential for creating a positive organizational culture.

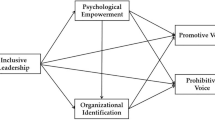

Integration of the Five Constants to generate ethical leadership

The Confucian Five Constants offer a robust framework for ethical leadership, guiding leaders to foster trust, cohesion, and societal impact. Figure 1 presents a general visual representation of the dimensions of ethical leadership as perceived by the authors in a Confucian context. The outer ring identifies four dimensions of ethical leadership related to leaders’ virtues: ren (benevolence), yi (righteousness), zhi (wisdom) and xin (integrity). These virtues are essential for ethical leadership. The inner ring emphasizes the dimension of behavior, or li (ritual), which serves as a crucial determinant of ethical leadership. It is through virtue that leaders are guides to behave ethically; therefore, the dimensions of ethical leadership should encompass both virtue and behavior. The five dimensions are interconnected. As suggested by Cavanagh and Bandsuch (2002), the cardinal virtues are intimately related, and their collective presence enables leaders to act ethically in a contextually appropriate manner, thereby demonstrating ritual behavior. Through this integrated approach, the Confucian framework for ethical leadership not only highlights the importance of individual virtues but also emphasizes the significance of ethical behavior in leadership practice.

Discussion

This study advances the theoretical and practical understanding of ethical leadership by proposing a comprehensive framework grounded in the Confucian Five Constant Virtues. By integrating diverse literature and addressing the under-researched integration of ethical leadership dimensions, this paper offers a multifaceted framework that unifies virtues and behaviors, internal attributes and external actions, and contextual adaptability. The conceptual and ethical implications of this framework are profound, providing a robust lens for understanding and cultivating ethical leadership in modern organizational contexts, particularly in bridging Western and Chinese leadership conceptions. Below, we elaborate on the theoretical contributions, practical implications, and directions for future research, emphasizing the framework’s significance in addressing contemporary leadership challenges.

Existing leadership theories are predominantly based on Western concepts, and while there is merit in applying these theories to a Chinese context, it is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of Western theory in comprehensively capturing Chinese leadership paradigms, particularly those grounded in the Five Constant Virtues. First, Western ethical leadership frameworks, such as those proposed by Brown and Treviño (2006), tend to focus on observable ethical behaviors, such as fairness and transparency, while often neglecting the internal moral development of the leader. In contrast, Confucian leadership is deeply rooted in the philosophy of “inner sage, outer king” (内圣外王) (Woods and Lamond 2011), which posits that ethical behavior is an extension of cultivated virtues like ren and yi. This emphasis on self-cultivation challenges Western models that overlook the introspective processes critical to ethical leadership in Chinese contexts. Second, Western leadership theories frequently prescribe rigid behavioral norms, such as the idealized influence characteristic of transformational leadership (Bass and Riggio 2006), which may lack the contextual adaptability essential in Chinese culture. The Confucian virtue of li, on the other hand, underscores the importance of contextually appropriate behaviors, enabling leaders to effectively navigate complex social dynamics, including the maintenance of harmony in high power distance settings. For instance, a Western leader’s tendency to provide direct feedback may be perceived as disruptive in a Chinese team, where li would advocate for indirect, relationship-preserving communication.

Theoretical implications

The Confucian Five Constant Virtues offer a novel conceptual framework that addresses critical gaps in ethical leadership research, particularly the lack of integration across existing studies. While prior research has predominantly focused on either value-driven behaviors (Riggio et al. 2010) or value-based virtues (Brown et al. 2005), often emphasizing virtues that prioritize others’ interests over those of the leader (Banks et al. 2021), our framework proposes a broader, more inclusive set of dimensions. By encompassing both virtues (ren, yi, zhi, xin) and virtue-based behaviors (li), the Confucian model provides a holistic approach that captures the dynamic interplay between a leader’s internal moral attributes and their external actions.

A key conceptual contribution lies in the Confucian emphasis on the unity of ren and li, where li serves as the external embodiment of ren, and ren provides the internal moral foundation for li. This unity challenges the fragmented approach in ethical leadership studies, which often treat virtues and behaviors as separate constructs. For instance, ren’s focus on empathy and care aligns with servant leadership’s emphasis on follower development, while yi’s commitment to justice complements ethical leadership’s fairness principles. Zhi and xin further enhance this framework by integrating rational decision-making and trust-building, respectively, which are critical for navigating complex, trust-deficient environments. Unlike Western models that may prioritize one or two virtues, the Confucian framework’s five dimensions offer a comprehensive taxonomy that captures the multifaceted nature of ethical leadership.

Moreover, this framework advances cross-cultural leadership theory by bridging Eastern and Western perspectives. This universal applicability of virtues like ren and xin makes the framework adaptable to diverse cultural contexts, while li’s contextual flexibility allows leaders to tailor behaviors to specific cultural norms. This cross-cultural integration not only enriches ethical leadership theory but also positions the Confucian framework as a foundation for developing global leadership models that balance universal ethics with cultural specificity. By operationalizing these dimensions, researchers can develop measurement scales that assess ethical leadership across contexts, addressing the need for a more integrated and empirically testable model.

Ethical implications

The ethical implications of applying the Confucian Five Constant Virtues to modern leadership are far-reaching, particularly in addressing pressing ethical challenges such as sustainability and diversity. This framework’s emphasis on ren encourages leaders to prioritize stakeholder well-being, fostering inclusive workplaces that value diversity and equity. For example, a leader practicing ren might implement policies to support underrepresented groups, aligning with organizational diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) goals. Similarly, yi’s focus on justice guides leaders in making fair decisions in resource allocation, such as prioritizing sustainable suppliers in global supply chains to mitigate environmental impact.

The framework also addresses the ethical risks of neglecting internal-external unity. Leaders who focus solely on external behaviors without internal virtues risk hypocrisy, eroding trust and legitimacy. Conversely, those with strong virtues but inconsistent behaviors fail to operationalize their ethics effectively. The Confucian model mitigates these risks by requiring leaders to align their moral character (ren, yi, zhi, xin) with their actions (li), fostering authenticity and accountability. This alignment is critical in high-stakes contexts, such as corporate governance, where ethical lapses can lead to reputational and legal consequences.

Practical implications for organizations and individuals

The Confucian framework offers significant practical implications seeking to cultivate ethical leadership and mitigate unethical behaviors. By integrating the Five Constant Virtues into organizational values, leadership teams can foster a culture of ethics that permeates decision-making and operations. For example, organizations can translate ren into employee wellness programs, yi into transparent performance evaluations, zhi into strategic foresight training, xin into accountability mechanisms, and li into standardized ethical protocols. Such initiatives not only reduce the risk of reputational damage but also enhance employee engagement and organizational resilience.

In terms of personnel management, the framework provides a buleprint for leadership development and assessment. Organization can design selection criteria and training programs based on the Five Constant Virtues to identify and nurture ethically fit leaders. For instance, assessment tools could evaluate candidates’ ren through empathy-based scenarios, yi through ethical dilemma simulations, and xin through trust-building exercises. Training programs might include workshop on li, teaching leaders to adapt behaviors to diverse cultural and organizational contexts. These efforts ensure that ethical leadership is systematically embedded in organizational practices, aligning with the growing trend of ethics-driven management.

For individuals, the framework severs as a guide for personal development. Aspiring and incumbent leaders can use the Five Constant Virtues as a self-assessment framework to evaluate their ethical competencies. For example, a manager aiming to transition into a leadership role might focus on developing ren bu practicing active listening or xin by consistently honoring commitments. By internalizing these virtues and aligning them with behaviors, individuals can enhance their ethical leadership skills, positioning themselves as credible and inspiring leaders.

Implications for further research

We have provided the dimensions essential for the formation of ethical leadership, utilizing the Five Constant Virtues to address gaps in ethical leadership research and practice. However, the integration of virtues and ethical behavior warrants further discussion in future studies. Consequently, we provide suggestions to inform and inspire future research based on our presentation of these dimensions. While we do not assert that our ideas are universally applicable to all organizations or scholars, we believe they serve as a valuable starting point.

First, researchers should conduct detailed investigations into the constituent elements of each virtue (ren, yi, zhi and xin) and their behavioral manifestations (li). For example, what specific behaviors reflect ren in task-oriented versus relations-oriented leadership roles? Developing measurement scales based on these dimensions is critical next step. Such scales could include items assessing ren through empathy and care, yi through fairness, zhi through strategic decision-making, xin through trust, and li through contextually appropriate actions.

Second, studies should explore how the Confucian framework interacts with existing leadership taxonomies, such as Yukl’s (2012) hierarchical model of task-oriented, relations-oriented, change-oriented, and external leadership. For example, does ethical leadership in task-oriented roles prioritize yi (justice in resource allocation) over ren (relationships)? Empirical studies could examine whether the relative importance of each virtue varies by leadership context, providing nuanced insights into the framework’s applicability.

Third, cross-cultural research is essential to test the framework’s universality and adaptability. Comparative studies could assess how the Five Constant Virtues are perceived and enacted in Eastern versus Western organizations, addressing potential tensions. Additionally, integrating the framework with emerging fields like digital leadership could yield valuable insights.

Finally, longitudinal studies are needed to identify the antecedents, processes, and outcomes of ethical leadership with the Confucian framework. Research could explore how organizational culture shapes the adoption of the Five Constant Virtues, how these virtues influence employee outcomes, and how they contribute to long-term organizational performance.

Conclusion

In this paper, we aimed to construct dimensions through which to integrate ethical leadership development. The Confucian Five Constant Virtues provide comprehensive and integrative framework for ethical leadership, addressing critical gaps in theory and practice. Conceptually, the framework enriches leadership scholarship by unifying virtues and behaviors, offering a holistic model that bridges Eastern and Western perspectives. Ethically, it equips leaders to navigate contemporary challenges, such as sustainability and diversity, by fostering authenticity, fairness, and trust. Practically, it offers actionable strategies for organizations to embed ethics in culture, training, and assessment, while empowering individuals to develop ethical leadership skills. By proposing a multi-faceted set of dimensions, this study lays the groundwork for future research to operationlize and validate the framework, ultimately contributing to development of ethical inclusive, and sustainable leadership in a globalized world.

References

Arjoon S (2000) Virtue theory as a dynamic theory of business. J Bus Ethics 28(2):159–178

Avolio BJ, Gardner WL, Walumbwa FO, Lithans F, May DR (2004) Unlocking the mask: a look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviours. Leadersh Quart 15:801–823

Badaracco JL, Ellsworth RR (1991) Leadership, integrity and conflict. J Organ Change Manag 4(4):46–55

Banks GC, Fischer T, Gooty J, Stock G (2021) Ethical leadership: mapping the terrain for concept cleanup and a future research agenda. Leadersh Quart 32:101471

Bass BM (1990) Handbook of leadership: a survey of theory and research. Free Press, New York

Bass BM, Riggio RE (2006) Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Bauman DC (2013) Leadership and the three faces of integrity. Leadersh Quart 24(3):414–426

Bragues G (2006) Seek the good life, not money: the Aristotelian approach to business ethics. J Bus Ethics 78(3):341–357

Bright D, Winn B, Kanov J (2014) Reconsidering virtue: differences of perspective in virtue ethics and the positive social sciences. J Bus Ethics 119(4):445–460

Broadie S, Rowe C (2002) Aristotle nicomachean ethics. Oxford University Press, New York

Brown M, Trevino LK (2006) Ethical leadership: a review and future directions. Leadersh Quart 17(6):596–616

Brown ME, Trevino LK, Harrison DA (2005) Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ Behav Hum Dec 97(2):117–134

Cavanagh GF, Bandsuch MR (2002) Virtue as benchmark for spirituality in business. J Bus Ethics 38(1):109–117

Chan GKY (2008) The relevance and value of Confucianism in contemporary business ethics. J Bus Ethics 77:347–360

Chen XP, Eberly MB, Chiang TJ, Farh JL, Cheng BS (2014) Affective trust in Chinese leaders: linking paternalistic leadership to employee performance. J Manag 40(3):796–819

Chen YR, Leung K, Chen CC (2009) Bringing national culture to the table: making a difference with cross-cultural differences and perspectives. Acad Manag Ann 3(1):217–249

Ciulla JB (2004) Ethics and leadership effectiveness. In: Antonakis J, Cianciolo AT, Sternberg RJ eds, The nature of leadership. Sage Publications, CA, pp. 302–327

Coloma S (2009) Vector. Bus World 17(4):16

Cottine C (2016) Role modeling in an early Confucian context. J Value Inq 50(4):797–819

Craig SB, Gustafson SB (1998) Perceived leader integrity scale: an instrument for assessing employee perceptions of leader integrity. Leadersh Quart 9(2):127–145

Den Hartog DN, De Hoogh AHB (2009) Empowering behaviour and leader fairness and integrity: studying perceptions of ethical leader behaviour from a levels-or-analysis perspective. Eur J Work Organ Psy 18(2):199–230

Dinh JE, Lord RG, Gardner WL, Meuser JD, Liden RC, Hu J (2014) Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. Leadersh Quart 25(1):36–62

Ding X, Fu S, Jiao C, Yu F (2024) Chinese philosophical practice toward self-cultivation: integrating Confucian wisdom into philosophical counseling. Religions 15(1):69

Fry LM (2003) Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. Leadersh Quart 14(6):693–727

Gonzalez T, Guillen M (2002) Leadership ethical dimension: a requirement in TQM implementation. TQM Mag 14(3):150–164

Gu C, Li Z (2023) The Confucian ideal of filial piety and its impact on Chinese family governance. J Sociol Ethnol 5(2):45–52

Hackett RD, Wang G (2012) Virtues and leadership: an integration conceptual framework founded in Aristotelian and Confucian perspectives on virtues. Manag Decis 50(5):868–899

Hanbury GL (2004) A ‘pracademic’s’ perspective of ethics and honor: imperatives for public service in the 21st century. Public Organ Rev 4(3):187–204

Hill JS (2006) Confucianism and the art of Chinese management. J Asia Bus Stud 1(1):1–9

Hogan R, Kaiser RB (2005) What we know about leadership. Rev Gen Psychol 9(2):169–180

Huang C (1997) The Analects of Confucius. Oxford University Press, New York

Ip PK (2009) Is Confucianism good for business ethics in China? J Bus Ethics 88:463–476

Irwin T (1999) Nicomachean ethics/Aristotle: translated with introduction, notes, and glossary. Hackett Publishing, IN

Islam G, Zyphur MJ (2009) Rituals in organizations: a review and expansion of current theory. Group Organ Manag 34(1):114–139

Johnson C (2001) Meeting the ethical challenges of leadership. Sage Publications, CA

Kalshoven K, Den Hartog DN, De Hoogh AH (2011) Ethical Leadership at Work questionnaire (ELW): development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Leadersh Quart 22(1):51–60

Keating M, Martin GS, Resick CJ, Dickson MW (2007) A comparative study of the endorsement of ethical leadership in Ireland and the United States. Ir J Manag 28(1):5–30

Khuntia R, Suar D (2004) A scale to assess ethical leadership of Indian private and public sector managers. J Bus Ethics 49(1):13–26

Kotterman J (2006) Leadership versus management: what’s the difference? J Qual Particip 29(2):13

Kouzes JM, Posner BZ (2006) The leadership challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Langlois L, Lapointe C, Valois P, de Leeuw A (2014) Development and validity of the ethical leadership questionnaire. J Educ Admin 52(3):310–331

Lawton A, Paez I (2015) Developing a framework for ethical leadership. J Bus Ethics 130(3):639–649

Li C (2006) The Confucian ideal of harmony. Philos East West 56:583–603

Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Liao C, Meuser JD (2014) Servant leadership and serving culture: influence on individual and unit performance. Acad Manag J 57(5):1343–1452

Lin LS, Li PP, Roelfsema H (2018) The traditional Chinese philosophies in inter-cultural leadership: the case of Chinese expatriate managers in the Dutch context. Cross Cult Strateg M 25(2):299–336

Lin L, Ho Y, Lin WE (2013) Confucian and Taoist work values: an exploratory study of the Chinese transformational leadership behavior. J Bus Ethics 113(1):91–103

Liu YQ, Ji SW (2019) A research on leadership structure from the Confucianism perspective. Int J Chin Cul Manag 1:96–106

Low PKC, Ang SL (2013) Confucian ethics, governance and corporate social responsibility. Int J Bus Manag 8(4):30

Ma L, Tsui AS (2015) Traditional Chinese philosophies and contemporary leadership. Leadersh Quart 26(1):13–24

Mayer DM, Kuenzi M, Greenbaum R (2010) Examining the link between ethical leadership and employee misconduct: the mediating role of ethical climate. J Bus Ethics 95:7–16

McCoy BH (2007) Governing values: the essence of great leadership. Leadersh Excell 24(5):11

McDonald P (2012) Confucian foundations to leadership: a study of Chinese business leaders across Greater China and South-East Asia. Asia Pac Bus Rev 18(4):465–487

Moore G (2012) The virtue of governance, the governance of virtue. Bus Ethics Q 22(2):293–318

Newstead T, Dawkins S, Macklin R, Martin A (2019) The virtues project: an approach to developing good leaders. J Bus Ethics 167:605–622

Palanski ME, Yammarino FJ (2007) Integrity and leadership: clearing the conceptual confusion. Eur Manag J 25(3):171–184

Palmer B, Walls M, Burgess Z, Stough C (2001) Emotional intelligence and effective leadership. Leadersh Org Dev J 22(1):5–10

Peterson C, Seligman MEP (2004) Character strengths and virtues: a handbook and classification. Anmerican Psychological Association, Washington, D.C

Piccolo RF, Greenbaum R, Den Hartog DN, Folger R (2010) The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. J Organ Beha 31(2/3):259–278

Resick C, Martin GS, Keating M, Dickson MW, Kwan HK, Peng AC (2011) What ethical leadership means to me: Asian, American, and European perspectives. J Bus Ethics 101(3):435–457

Riggo RE, Zhu W, Reina C, Maroosis JA (2010) Virtue-based measurement of ethical leadership: the leadership virtues questionnaire. Consult Psych J 2(4):235–250

Sama LM, Shoaf V (2008) Ethical leadership for the professions: fostering a moral community. J Bus Ethics 78(1):39–46

Schenck A, Waddey M (2017) Examining the impact of Confucian values on leadership preferences. J Org Educ Leadersh 3(1):n1

Sheng X (2019) Confucian home education in China. Educ Rev 71(6):712–729

Simons T (2002) Behavioral integrity: the perceived alignment between manager’s words and deeds as a research focus. Organ Sci 13(1):18–35

Spangenberg H, Theron CC (2005) Promoting ethical follower behaviour through leadership of ethics: the development of the Ethical Leadership Inventory (ELI). S Afr J Bus Manag 36(2):1–18

Storr L (2004) Leading with integrity: a qualitative research study. J Health Organ Manag 18(6):415–433

Stouten J, Baillien E, Broeck A, Camps J, Witte HD, Euwema M (2010) Discouraging bullying: the role of ethical leadership and its effects on the work environment. J Bus Ethics 95(1):17–27

Tan C (2024) Integrating moral personhood and moral management: a Confucian approach to ethical leadership. J Bus Ethics 191(1):167–177

Trevino LK (1986) Ethical decision making in organizations: a person-situation interactionist model. Acad Manag Rev 11:601–617

Trevino LK, Hartman LP, Brown M (2000) Moral person and moral manager: how executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. Calif Manag Rev 42(4):128–142

Tu Y, Lu X (2013) How ethical leadership influence employees’ innovation work behavior: a perspective of intrinsic motivation. J Bus Ethics 116:441–455

van Dierendonck D (2011) Servant leadership: a review and synthesis. J Manag 37(4):1228–1261

Walker A, Haiyan Q, Shuangye C (2007) Leadership and moral literacy in intercultural schools. J Educ Admin 45(4):379–397

Wang BX, Chee H (2011) Chinese leadership. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Wang G, Hackett RD (2020) Virtues-centered moral identity: an identity-based explanation of the functioning of virtuous leadership. Leadersh Quart 31(5):101421

Wang G, Hackett RD (2016) Conceptualization and measurement of virtuous leadership: doing well by doing good. J Bus Ethics 137:321–345

Wang J, Wang GG, Ruona WEA, Rojewski JW (2005) Confucian values and the implications for international HRD. Hum Resour Dev Int 8(3):311–326

Watson B (2007) The Analects of Confucius. Columbia University Press, New York

Webley S, Werner A (2008) Corporate codes of ethics: Necessary but not sufficient. Bus Ethics 17(4):405–415

Weiming T (2017) Implications of the rise of “Confucian” East Asia. In Multiple Modernities. New York: Routledge, pp. 195–218

Whetstone JT (2001) How virtue fits within business ethics. J Bus Ethics 33(2):101–114

Woods PR, Lamond DA (2011) What would Confucius do?–Confucian ethics and self-regulation in management. J Bus Ethics 102:669–683

Yao X (2000) An introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Yuan L, Chia R, Gosling J (2023) Confucian virtue ethics and ethical leadership in modern China. J Bus Ethics 182(1):119–133

Yukl G (2012) Effective leadership behavior: what we know and what questions need more attention. Acad Manag Perspect 26(4):66–85

Yukl G, Mahsud R, Hassan S, Prussia GE (2013) An improved measure of ethical leadership. J Leadersh Org Stud 20(1):38–48

Zhu W, Zheng X, He H, Wang G, Zhang X (2019) Ethical leadership with both ‘moral person’ and ‘moral manager’ aspects: scale development and cross-cultural validation. J Bus Ethics 158:547–565

Zhu W, Zheng X, Riggio RE, Zhang X (2015) A critical review of theories and measures of ethics‐related leadership. New Dir Stud Leadersh 146:81–96

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HW wrote and critical reviewed the manuscript, analyzed and interpreted the results. XX conceptualized the study, wrote and critical reviewed the manuscript, and interpreted the results. HW and XX equally contributed to the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Xiang, X. The construction of ethical leadership from a Chinese cultural perspective. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 957 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05360-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05360-3