Abstract

Affirmative action in China’s selective examinations arises from the pursuit of educational equity and recognition of challenges faced by disadvantaged examinees. Selective examinations, exemplified by the imperial examination (Keju) and the National College Entrance Examination (Gaokao), serve as mechanisms for social mobility. This study employs historical and policy research methods, integrating theoretical analysis with historical investigation. By integrating historical and modern contexts, the research explores how affirmative action measures have been supporting disadvantaged examinees, hoping to provide the international community with a broader understanding of over a millennium of China’s efforts to support vulnerable examinees in the examination system. Affirmative action in the imperial examination is characterized by its long duration and limited effectiveness. In the case of the Gaokao, affirmative action plays a positive role, but there is a lack of precise identification of disadvantaged candidate groups. Therefore, efforts should continue across multiple dimensions, including institutional guarantees, policy support, and resource assistance, to promote fairness in examinations and safeguard educational equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Competitive examinations stand as one of society’s most crucial cultural activities, bearing not only the significant responsibility of talent selection but also the societal duty to promote vertical social mobility. They play a vital role in upholding social fairness and justice. (Liu and Li, 2024) Peter K. Bol notes that Princeton University Professor Elman’s research on China’s imperial examination is “A very important study of one of the most important institutions in Chinese history, one without which the China we have today would certainly be a vastly different place” (Elman, 2000). The imperial examination system was established in the year 605 ce. During the Song Dynasty, the imperial examination system developed rapidly in China, and during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the imperial examination system reached its peak (Yuan and Lin, 2023). However, whether in the imperial examinations or the college entrance examinations, the impartiality of the competitive mechanism does not necessarily translate into equal opportunities for exam results. Persistent disparities exist, leaving marginalized groups in society unable or struggling to achieve social advancement through these examinations. Therefore, the pursuit of educational equity places a strong emphasis on “disadvantaged examinees,” with both the nation and society hoping that affirmative action can aid in changing their destinies. This not only holds positive implications for the reform of higher education entrance examinations in China but also carries significant value for understanding how to address the needs of disadvantaged examinees in university entrance examinations globally.

The promotion of social mobility by the imperial examination system is widely recognized by scholars. Kracke (1947) argued that the imperial examination was an important pathway for talented individuals to enter the bureaucratic class and a significant factor in promoting social mobility. Ho (1962) believed that the imperial examination played a crucial role in promoting social mobility and maintaining the stability of the bureaucratic class during the imperial period, with the composition of the bureaucratic class being in a state of flux and new blood continuously being infused into the ruling class. In the past 20 years, numerous studies have discussed the degree of this mobility, including works by scholars such as Elman (2000); Ren et al. (2020); Bai and Jia (2016). There are also too many scholars. However, the extent of mobility is not the focus of this paper, so this article will not list them one by one. This study is based on the consensus among scholars that the imperial examination facilitated social mobility and aims to explore supportive policies related to the imperial examination that assisted disadvantaged examinees, beyond the examination itself. The purpose is to introduce these previously undiscussed supportive policies to the international community.

From an international perspective on disadvantaged examinees and college entrance examinations, in earlier research, Heyneman and Ransom (1990) gave policy recommendations on examination policies and students’ economic conditions. Charles et al. (2007) studied African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics, finding that these disadvantaged groups faced significant economic and cultural disadvantages in educational investment, which profoundly impacted their college access opportunities. In a recent study, John Jerrim et al. (2015) analyzed university entrance examination scores and families in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States, and also believed that disadvantaged family backgrounds affected students’ entrance examinations. In response to these problems, Page and Scott-Clayton (2016) called for financial assistance to disadvantaged examinees. Ayushi Narayan (2020) believes that improving affirmative action policies can help relevant groups, which also confirms the argument of this study calling for affirmative action for disadvantaged examinees.

National examinations hold unique significance for China and the broader world. Historically, China’s imperial examination system (Keju) was implemented for 1300 years, significantly expanding upward social mobility for commoners and enabling virtual universal participation. This system profoundly influenced neighboring countries; Korea followed China’s model, maintaining its own imperial examination system for over 900 years, while Japan and Vietnam also introduced similar systems. By contrast, during the same historical period, Europe largely relied on hereditary aristocracy, while many other societies maintained lineage-based systems, which restricted educational opportunities for the common population and lacked competitive examination structures altogether. The imperial examination system deeply embedded the concepts of educational and examination fairness in Chinese culture and gradually evolved into a sophisticated and equitable selection mechanism over centuries. In modern times, this traditional practice transformed into the current College Entrance Examination. Despite superficial differences, particularly regarding updated examination content reflecting contemporary civilization, both systems share a continuous core: both are nationwide, government-administered, large-scale competitive examinations featuring many similar fairness-oriented policies. Thus, this study adopts a historical perspective, not only analyzing more than 70 years of Gaokao policy but also broadening its analytical scope to include the ancient imperial examination system. The objective is to provide a comprehensive picture of nearly 1400 years of Chinese competitive examinations, specifically focusing on policies aimed at ensuring fairness and supporting disadvantaged groups.

Research on the fairness of examination systems in both Eastern and Western contexts requires a bridge for dialogue. The examination systems in China, whether in the form of the imperial exams or the contemporary Gaokao, should distill generalizable principles and engage in dialogue with international peers. Currently, such research lacks this kind of cross-cultural engagement, as scholars studying ancient examinations are often unaware of contemporary systems, while those researching modern exams tend to overlook the historical experiences and lessons from past examination systems. Moreover, scholars focusing on a single country’s exam system frequently fail to understand similar theories on remedying disadvantages for marginalized candidates in other countries.

Therefore, the innovation and goal of this study lie in adopting an internationally recognized perspective on affirmative action. Additionally, the study provides an in-depth historical analysis and comparative international perspective, positioning itself at the intersection of historical reflection and contemporary insight, while simultaneously bridging Eastern and Western scholarly traditions. It also embodies cross-disciplinary dialogue by integrating social sciences and humanities. This study employs historical and policy research methods. By integrating historical and modern contexts, it addresses the following research questions: 1. How have affirmative action measures supported disadvantaged examinees within China’s examination systems (Keju and Gaokao) over the past millennium? 2. In what ways can these historical affirmative action measures inform contemporary policies and practices aimed at supporting vulnerable examinees?

Conceptual definition

The mechanism of affirmative action policies in China’s selective examinations

Affirmative action is a concept originating in the United States (Sterba, 2009). It broadly refers to a common policy phenomenon implemented across different countries to address issues of fairness. Existing research has provided extensive definitions of this concept, though scholarly interpretations vary. Some scholars define affirmative action as special preferences or privileges granted to specific disadvantaged groups (Swain, 1996), aiming to mitigate their disadvantages in the distribution of certain benefits or opportunities (Faundez, 1994). Others argue that affirmative action does not necessarily entail preferential treatment (Rosenfeld, 1991). Some scholars have also paid attention to different types of affirmative action (Bengtson, 2025). Overall, affirmative action can be defined as a set of public policy measures implemented by the state to support specific disadvantaged groups, encompassing but not limited to preferential treatment and targeted assistance.

Affirmative action in China’s selective examinations arises from the pursuit of educational equity and the recognition of the challenges faced by disadvantaged examinees. Selective examinations, exemplified by the imperial examination and the National College Entrance Examination, serve as mechanisms for social mobility. Given their significant societal implications and the wide range of individuals they impact, any unfairness in policy design or implementation could directly undermine the credibility of both the state and its governing authorities.

In the context of selective examinations, the prevailing fairness principle in China emphasizes that personal effort should correspond to examination outcomes—suggesting that individuals can overcome inherent disadvantages, including socio-economic background, through diligence. However, equality in rights does not necessarily equate to equality of opportunity. Structural disparities, such as those stemming from family resources and external socioeconomic factors, create competitive gaps that are difficult to bridge through personal effort alone. Consequently, substantial differences in the success rates of different social groups emerge in selective examinations. Therefore, implementing policies that provide preferential support or targeted assistance to disadvantaged examinees becomes crucial in addressing these disparities.

Disadvantaged examinees in China’s selective examinations

Disadvantaged examinees refer to students who participate in selective examinations while facing adverse circumstances (disadvantage), sharing characteristics with economically and socially disadvantaged children in a broader sense. Existing research offers diverse definitions of disadvantaged children, generally referring to those from impoverished families or economically and culturally marginalized backgrounds (e.g., economically disadvantaged children, underprivileged children). Some scholars define disadvantaged children as those facing challenges in their upbringing or personal development, including children from low-income families, ethnic minority backgrounds, single-parent households, or with physical and mental disabilities (Frost and Hawkes, 1966). Other studies consider indicators such as aristocratic lineage (Sohani,1994) or parental social status (Chalifoux and Fagan, 1997) to assess social disadvantage. Despite differences in classification criteria, these studies highlight the economic and social disadvantages faced by these children. When such individuals reach the appropriate age and compete in selective examinations alongside other examinees, they are categorized as disadvantaged examinees.

Affirmative action in China’s selective examinations primarily targets disadvantaged examinees. Although official policies lack a precise definition of this group and employ various terminologies to describe them, family background remains the fundamental criterion for identification. In ancient China, the narrow definition of disadvantaged examinees referred to “students from impoverished families and lower-class backgrounds with low paternal or ancestral status,” while the broader definition encompassed all children from commoner backgrounds (Lin and Liu, 2021). In modern China, disadvantaged examinees typically refer to students from rural backgrounds with limited financial resources (Xu, 2017), including but not limited to ethnic minority students (Fan, 2020).

The challenges faced by disadvantaged examinees stem not only from material and cultural deficiencies but also from the lack of alternative social mobility pathways and their lower capacity to mitigate risks in selective examinations. Aside from these examinations, such examinees have limited alternative routes for upward social mobility. If they fail in the selection process, they often struggle to find alternative opportunities, frequently resorting to repeated attempts in order to secure access to higher education. Affirmative action in China’s selective examinations primarily aims to safeguard the effectiveness of the limited social mobility channels available to disadvantaged examinees.

The framework of affirmative action policies in China’s selective examinations

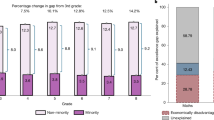

Affirmative action in China’s selective examinations has a long history and encompasses various initiatives. Drawing on Douglas Rae’s analytical framework on equal opportunity, relevant measures can be categorized into three dimensions: institutional guarantees, policy preferences, and resource assistance. This study uses these three dimensions as a tool to analyze different manifestations of affirmative action across different periods of selective testing in China (see Fig. 1).

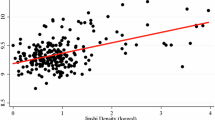

Douglas Rae introduced two concepts: “prospect-regarding equality” and “means-regarding equality” to explain the concept of equal opportunities. The former represents the concept that different groups should have an equal probability of success, while the latter emphasizes procedural equality, where all groups are treated equally in the selection process. He further illustrated the practical relationship and contradictions between these two fairness perspectives using a diagram (see Fig. 2).

The horizontal axis in the figure represents different procedures, while the vertical axis represents the probability of success. A and B represent two distinct groups. In any procedure, the probability of success for A is always greater than that of B (at any level of means, A has a better prospect for success than B). This figure illustrates that, in cases where there is an absolute difference in talent between groups A and B, it is impossible to achieve equal success probabilities for both groups when subjected to the same means (Rae et al., 1983). Therefore, this study aims to emphasize achieving fairness in the probability of success for all examinees, namely, emphasizing “prospect-regarding equality”.

Based on this theory, three methods for achieving Prospect-regarding equal opportunity in selective examinations can be derived. These three methods are widely observed in the history of selective examinations in China. Using Douglas Rae et al. (1983) framework, a figure can be constructed to depict equal opportunity in China’s selective examinations, where the horizontal axis represents the examination procedures, and the vertical axis represents the probability of achieving the same result in the exam. The curves represent the abilities (talent/competitiveness) of different groups in the examination. The lower curve represents disadvantaged examinees.

To achieve prospect-regarding equality in selective examinations, three approaches can be identified, each representing a distinct affirmative action measure. This classification framework is also applicable to affirmative action policies worldwide.

Institutional guarantees

“Institutional guarantees” refer to the maintenance of fairness in examination procedures, preventing external powers from interfering with fair competition and eliminating illegal differential treatment between different groups in selective examinations. Given that there are also internal differences within each group, in practice, situations may arise where A and B have comparable examination abilities. In such cases, ensuring equal treatment in the examination procedures guarantees equivalent probabilities of success. In other words, the destruction of procedural fairness (means-regarding equality) means that groups A and B are, in fact, facing different examination procedures (as shown in Fig. 3, where MA and MB represent two different exam procedures). Even if their ability curves are identical, the probabilities of success (as represented by Prospect for exam success in Group A and Prospect for exam success in Group B in Fig. 3) will not be equal.

Merit-based selection is one of the fundamental principles of selective examinations. In a fair examination process, disadvantaged examinees generally have lower odds of achieving excellent results. However, if the examination process is interfered with by external powers, even the limited opportunities will be completely eroded. The basic fairness of the selective examination process is also the foundation for the effectiveness of other affirmative action measures. Since selective examinations are inherently a mechanism for social mobility, ensuring the fair operation of this macro system is the greatest guarantee of opportunity for disadvantaged examinees. Some early U.S. legislative acts or executive orders based on the principle of “eliminating discrimination” can be viewed as falling under this category.

In the imperial examination era, “institutional guarantees” primarily focused on curbing bureaucratic interference in the examination process. As part of the bureaucratic system, the imperial examination still adhered to the principle of rule by man. During certain phases of the feudal bureaucratic system, senior officials often found it feasible to manipulate examination outcomes. Bureaucratic offspring not only enjoyed educational advantages stemming from political and economic privileges but also gained unfair advantages through bureaucratic interference in the examination process. The latter severely undermined the value of the imperial examination as a system accessible to commoners. During the feudal period, the public was highly sensitive to the likelihood of bureaucratic offspring succeeding in the exams, which could threaten the fairness of the imperial examination. This required significant institutional design to maintain equal treatment in the competitive mechanism.

Policy favoritism

“Policy favoritism” refers to special provisions made in the examination process for specific groups, including aspects such as the content of the examination, the format of the examination, and the methods of admission. In reality, it is almost impossible for the examination abilities of groups A and B to be identical. Treating individuals from different circumstances equally can only perpetuate injustice, rather than eliminate it. To achieve fairness in the probability of success for both groups, different examination procedures should be implemented for different groups (see Fig. 4). Policy favoritism, which proactively modifies the system to benefit disadvantaged examinees, represents a form of affirmative action.

The measures of policy favoritism in the imperial examination and the National College Entrance Examination differ. During the imperial examination period, “policy favoritism” was primarily reflected in the active preferential treatment given to disadvantaged examinees in both the selection process and the result determination. This included accommodating disadvantaged examinees’ abilities through adjustments to examination content or format and intentionally promoting disadvantaged examinees in the admissions process. Compared to the imperial examination, the Gaokao not only focuses on talent selection but also emphasizes the protection of the educational rights of different groups, which requires a more specialized system design. Therefore, policy favoritism measures are more prevalent in the Gaokao era.

Policy favoritism has clear requirements for its target groups and directly alters the disadvantaged examinees’ disadvantaged position through changes in the examination process or results. Policy favoritism can be viewed as a direct method of affirmative action. The UK’s Contextualised Admissions, as well as special admissions policies for minority groups at institutions such as Harvard University (Karabel, 2005), the University of Michigan (Hirschman et al., 2016), and Cornell University (Downs, 2012), can all be viewed as examples of this approach.

Resource assistance

Resource assistance refers to the provision of material and cultural resources for disadvantaged examinees, with the aim of improving their examination abilities. In practice, the difference in the probability of success between groups A and B arises from the distinction in their examination abilities. John E. Roemer classified the factors affecting competitive outcomes into two aspects: effort and circumstances (Roemer and Trannoy, 2016). Relevant systems can alter the environmental factors for disadvantaged examinees, such as supplementing their economic and cultural capital, which brings their examination abilities closer to those of non-disadvantaged examinees (as shown in Fig. 5, the shift of Group B’s curve represents the improvement of their examination capability). This approach is similar to the perspective proposed by U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson in his speech at Howard University, where he advocated for enhancing the abilities of disadvantaged groups to achieve fairness in outcomes (Johnson, 1966).

The preparation before and the admissions process after the Gaokao both impact the actual outcomes of the examination. For instance, a considerable number of disadvantaged examinees may abandon their pursuit of higher education due to the financial pressure of attending university. In this sense, addressing their financial burdens also serves to improve their chances of success in competitive exams.

During the imperial examination period, “resource assistance” encompassed both financial and cultural dimensions. Financial assistance focused on alleviating economic burdens of exam participation. Disadvantaged examinees were often confronted with the challenge of traveling long distances to reach exam venues. Without adequate financial support to reach the examination venue, any affirmative action within the imperial examination system would be ineffective. The cultural aspect primarily involved providing educational resources to disadvantaged examinees. In an era when the right to education was not widespread, the emergence of public education targeting disadvantaged examinees, while not eliminating the cultural gap between students of different backgrounds, provided opportunities for disadvantaged examinees to acquire knowledge and potentially alter their life trajectories.

Affirmative action in the imperial examination system across different dynasties

Currently, there are an increasing number of researchers studying the imperial civil service examination system, and the exploration of the Keju system has become progressively clearer (Feng, 2021; Yuan, 2022). Even in the strictly hierarchical feudal era, the imperial examination system exhibited a tendency to favor disadvantaged examinees. “The imperial examination prioritized the selection of talented individuals from impoverished backgrounds” (Ding, 2003). The notion that the imperial examination should favor disadvantaged examinees gradually became a consensus. With this value in mind, both the government and the public paid close attention to the success of impoverished rural children in the imperial examination, leading to various affirmative action measures designed to help them achieve their examination aspirations. During the imperial examination period, affirmative action was already divided into three types: institutional guarantees, policy favoritism, and resource assistance, but their implementation was more scattered and varied across different dynasties (as shown in Fig. 6).

Regarding the objectivity in selecting historical sources, it should be clarified that, in exploring supportive policies for disadvantaged examinees within the imperial examination system, this study endeavors to objectively and comprehensively characterize various policy categories across historical periods. The historical sources selected have essentially encompassed all known policies directed toward disadvantaged examinees throughout the history of the examination system. However, due to constraints on space, only two or three representative cases have been presented for certain policy types for specific dynasties.

Imperial examination initial and institutional guarantee period(Sui and Tang dynasties)

The Sui and Tang Dynasties marked the initial period of the imperial examination, during which affirmative measures in the exam were limited to “institutional guarantees.” The imperial examination system during the Sui and Tang dynasties was still in its early stages and had not yet been fully opened to the commoners, with limited attention given to disadvantaged examinees. Despite being influenced by practical experiences and the “recommendation system” (Chaju) tradition, the imperial examination during this period saw few affirmative measures, yet the challenges it posed significantly influenced later systems. Some of these issues even shaped the fundamental structure of the imperial examination system in subsequent dynasties. The affirmative action of this period was primarily reflected in the aspect of “institutional guarantees” while documented evidence of policy favoritism and resource assistance remains scarce.

Institutional guarantees in the imperial examination of the Sui and Tang dynasties mainly focused on reducing the influence of the “recommendation system” on the examination process, with the goal of diminishing the weight of bureaucratic favoritism in determining examination results. For example, during this period, a two-tier examination system was gradually established, under which local recommendations could only affect eligibility for the examination, not the examination results. Regarding the examination institutions and examiners, the Tang dynasty raised the rank of examiners and placed the Ministry of Rites in charge of the imperial examination, thereby reducing the overreach of higher bureaucrats into the examination process. Because the imperial examination in the early Tang dynasty was influenced by the recommendation system, evaluations by officials and aristocrats had a significant impact on the examinees’ success. “Examiners judged examinees based on their personal preferences or biases” (Han, 1986). Therefore, examinees often “sought the patronage of powerful families and aristocratic families with high status and influence” (Feng, 2005), utilizing various means to obtain recommendations from the elites. During the early Tang dynasty, examiners were of lower rank and could not resist the illegal interventions from the elite, so they had to accept their arrangements. To prevent such interference, in the 24th year of the Kaiyuan era (736), after a false accusation against an exam official, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang raised the rank of the chief examiner from the “Sixth Rank” to the “Fourth Rank” (Wang, 1960). The palace examination system introduced by Empress Wu Zetian, in which the emperor personally presided over the highest-level examinations, further centralized the examination process under imperial authority. These measures significantly reduced the space for bureaucratic intervention and laid the foundation for the fairness of the imperial examination in subsequent dynasties.

During the Sui and Tang dynasties, “policy favoritism” and “resource assistance” were not as prominent. The policy favoritism during this period was relatively limited, with a notable example being Empress Wu Zetian’s efforts to open the imperial examination to commoner families. In terms of exam content, she actively reduced the dominance of Confucian knowledge, controlled by the aristocracy, in the examinations (Liu, 1975). Although this approach led to the neglect of school education, often described as “the flourishing of the imperial examination caused the decline of schools” (Lv, 2005), it lowered the threshold for participating in the examinations, allowing disadvantaged examinees with little access to formal education to take part. In terms of examination eligibility, Empress Wu Zetian introduced the system of “self-registration,” which allowed examinees to apply for the imperial examination without local officials’ recommendations. This move not only curbed local officials’ interference in the examination but also enabled more disadvantaged examinees to participate in the imperial examination. These efforts were motivated by the pursuit of fairness in the imperial examination system and had a lasting influence on its design in later periods. As for resource assistance, although some central and local government-run schools were opened to disadvantaged examinees, there were no specific policies offering them preferential treatment. Disadvantaged examinees did not receive special financial or cultural support. Overall, the focus of examination fairness during this period was primarily on maintaining procedural justice.

Multiple affirmative action appeared period (Song and Yuan Dynasties)

The Song and Yuan Dynasties were the stage of the diversification of affirmative action in the imperial examinations, and three different kinds of affirmative action began to emerge at this time. With the increasing influence of the imperial examination system on the selection of officials during the Song and Yuan dynasties, issues of examination fairness received significant attention. During this period, many historical records explicitly referenced disadvantaged examinees, reflecting various forms of affirmative action directed at this group. The Song dynasty, in particular, placed considerable emphasis on the success of disadvantaged examinees, as the bureaucratic governance model required the imperial examination to facilitate social mobility for maintaining autocratic rule. Against this backdrop, the Song dynasty attached great importance to the success of disadvantaged examinees in the imperial examination. The Yuan dynasty held a relatively indifferent attitude toward the imperial examination, and the court suspended it on multiple occasions. However, this does not imply that the guiding role of the examination system in Yuan-era education should be overlooked. On the contrary, the repeated suspension and subsequent reinstatement of the imperial examination during the Yuan dynasty serves as indirect evidence of its continued and irreplaceable influence.

Institutional guarantees primarily focused on maintaining the selection standard of merit-based recruitment and reducing discrimination against disadvantaged examinees in the selection and admission processes. Throughout the Song dynasty, the imperial examination system aimed to minimize interference from bureaucratic elites and create pathways for social mobility for disadvantaged examinees. In the early Song period, the scholar-official Xia Song once warned, “Officials overseeing the imperial examination may act with integrity by admitting disadvantaged examinees, but they risk offending the powerful and bringing trouble upon themselves. Meanwhile, those who favor aristocrats and act unfairly face no consequences” (Huang and Yang, 2012). To correct this trend, the imperial examination had to maintain the personal talent as the central criterion in admissions. In the first year of the Xianping era (998), Emperor Zhenzong of the Song emphasized, “The imperial examination is of utmost importance, and its purpose must be to select outstanding talents from impoverished backgrounds, rigorously assessing their true knowledge and skills” (Chen, 2006). Nevertheless, aristocratic dominance in the examination system persisted in reality. During Emperor Renzong’s reign, an official memorialized: “Government positions and prestigious ranks are meant to encourage scholarly pursuits. But if these positions are monopolized by aristocrats and granted through personal connections, how can impoverished scholars be motivated to study? We must reinforce previous edicts, implement strict laws, and eliminate those who fraudulently obtain official positions, ensuring a just selection process” (Li, 2004). In the Southern Song, Emperor Gaozong similarly stressed that “the primary value of the imperial examination is fairness. Examiners must reach collective decisions, and personal preferences must not influence results” (Tuo et al. 1985). This principle was widely praised by court officials, who believed that “selecting talented individuals from impoverished backgrounds while curbing aristocratic influence ensures the integrity of the official selection process” (Li, 1988). To implement this vision, Emperor Gaozong actively cracked down on examination fraud. Scholars noted that “from this point onward, those with true talent were selected, impoverished but capable scholars had opportunities, fraudulent practices were eliminated, and the culture of relying on illicit means for official status was curbed” (Li, 1988).

During the Song and Yuan periods, policy favoritism focused on providing preferential treatment to disadvantaged examinees in the examination format and selection process. A later evaluation of the Song imperial examination noted that “in the Song dynasty, the selection of the Zhuangyuan (top-ranking candidate) prioritized disadvantaged examinees” (Huang, 1999), highlighting the era’s concern for these examinees. Emperor Taizu of the Song once argued that “powerful families should not compete with those from impoverished backgrounds for opportunities in the imperial examination” (Huang et al. 2004). Based on this principle, he disqualified the sons of officials and those who already held government positions from taking the exam. Similarly, Emperor Zhenzong repeatedly emphasized that the primary function of the examination was to select talent from disadvantaged backgrounds. He even reprimanded local officials and demanded an increase in the admission rate of disadvantaged examinees: “Have the officials in various prefectures failed to grasp my intent? If they can select impoverished but talented individuals, what harm would there be in admitting more of them?” (Li, 2004). When appointing examiners, Zhenzong encouraged them to “uphold fairness in the imperial examination and prioritize selecting disadvantaged yet exceptionally talented examinees” (Li, 2004). Furthermore, some chief examiners demonstrated individual preferences in favor of disadvantaged examinees, though such actions were not officially codified. Nonetheless, these efforts were frequently praised in personal biographies. For example, Jia Huangzhong was commended by the emperor for “admitting many impoverished scholars” while overseeing the examination (Dong and Yan, 2013). Similarly, Li Zhongyan was praised for “recommending and selecting over four hundred impoverished scholars across multiple examination sessions” (Wang and Feng, 2012).

In the Song and Yuan periods, resource assistance mainly consisted of efforts to reduce economic hardship. Economic difficulties affected disadvantaged examinees’ mindset and performance: “They had no savings, lacked food while traveling, and their families suffered from hunger and cold at home. Their servants, horses, and carriages struggled along the road. In such conditions, examinees were anxious and unable to concentrate on the imperial examination” (Chen and Peng, 2002). To support these examinees, the Song government provided free lodging and transportation for students from remote areas. In the Southern Song, official charitable organizations such as Gongshizhuang and Gongshiku were established to subsidize examination travel expenses. Additionally, the rise of private academies provided food and lodging, creating learning environments that gave disadvantaged scholars better opportunities to change their social status.

Multiple affirmative action mature period (Ming and Qing Dynasties)

The period of Ming and Qing dynasties was a mature stage for the development of multiple affirmative action in the imperial examination, and the three affirmative action all had richer connotations and systematization. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the concept of preferential treatment for disadvantaged examinees in the imperial examination system became more deeply ingrained. Not only did institutional guarantees and policy favoritism remain stable, but measures related to resource assistance also became more widespread. The implementation of affirmative action during the Ming and Qing dynasties demonstrated the inertia of institutional development, as the specific measures remained similar to those of previous periods, and the related systems followed the established models of the Ming dynasty.

The “institutional guarantees” in the Ming and Qing dynasties were primarily reflected in comprehensive anti-fraud measures. As the imperial examination system matured and developed, the discriminatory status of disadvantaged examinees in the examination process gradually diminished. The selection of examinees in the imperial examination, particularly, placed emphasis on promoting talented individuals from impoverished backgrounds, recognizing that they might abandon their studies or give up on the examination due to difficult circumstances (Li, 1974). Meanwhile, under the influence of public opinion and other factors, the illegal interference of bureaucratic power in the imperial examination began to decrease. During the Ming and Qing periods, the “institutional guarantees” primarily focused on preventing examinees from circumventing established procedures, i.e., preventing examination fraud. Anti-fraud measures in the imperial examination system included the confidentiality of exam papers, examiner avoidance, entrance inspections, monitoring of examiners, and sealing of exam scripts, among other aspects. These measures formed a relatively comprehensive anti-cheating system, effectively reducing the interference of illegal methods and ensuring procedural fairness.

The “policy favoritism” in the Ming and Qing dynasties was particularly evident in the examination admissions process, where special quotas for disadvantaged examinees were established. For example, during the Guangxu era, the court set up “special admission quotas for disadvantaged examinees from remote regions” (Zhu et al., 1960). Additionally, illegal occupation of these quotas was strictly prohibited, and cases of examinees impersonating others from the same region to participate in the examination were forbidden. Disadvantaged examinees who had failed in previous examinations were also appointed to lower-ranking bureaucratic positions to placate them after competitive failures. Moreover, preferential treatment for disadvantaged examinees continued during this period and remained widely praised. For instance, Zhang Lin, who served as a scholar-official in Fujian, was praised for his efforts in promoting talented yet impoverished scholars and refusing to adhere to unreasonable customs (Zhao et al., 1977). Similarly, Lao Zhibian, when overseeing the imperial examinations in Jiangnan, was praised for maintaining integrity and selecting talented scholars from impoverished backgrounds (Qian, 1993). Additionally, Wang Shan, who served as the scholar-official in Zhejiang, was acknowledged for reforming the long-standing issues in the examination system and selecting talented individuals from impoverished families (Zhao et al., 1977). In comparison to the admissions process, fewer affirmative action policies were implemented in exam content and format during this period. For instance, in the 27th year of the Guangxu era, a minister suggested merging the annual and imperial examinations in seven counties of Hengzhou to reduce the commuting time and costs for examinees from remote areas (The Palace Museum, 1959). This suggestion, which facilitated disadvantaged examinees’ participation, came relatively late and near the abolition of the imperial examination.

Resource assistance during the Ming and Qing periods primarily involved public investment, addressing both the economic and cultural needs of examinees. For instance, in the Guangxu era, the Liuba region in Hanzhong Prefecture was extremely impoverished, and “whenever the imperial examination was held, impoverished scholars often found it difficult to raise the necessary funds for travel, sighing silently in despair” (Zhu et al., 1960). To address this, local official Chen Wenfu advocated establishing schools to improve these students’ cultural proficiency and provided them with living allowances to cover their daily expenses. Furthermore, some officials personally sponsored disadvantaged examinees to support their participation in the imperial examination. For example, Cui Ji helped impoverished scholars with financial difficulties (Qian, 1993), and Wang Zhichun, despite his own financial limitations, was “generous and supportive of the education and cultivation of disadvantaged examinees” (The Palace Museum, 1958). In addition to financial assistance, cultural support for disadvantaged examinees also grew. “Most of those who diligently pursued learning were from impoverished backgrounds. They wished to buy books but lacked the funds, and finding someone to borrow books was difficult. As a result, their knowledge was shallow and their horizons narrow, leading to unfulfilled potential. Emperor Qianlong understood this situation” (Zhu et al., 1960). This statement highlights Emperor Qianlong’s recognition of the cultural disadvantages faced by impoverished examinees, which contributed to their lower success rates in the imperial examination. In response, he established three public libraries in Jiangnan to allow all students to borrow books and study. Apart from official investments, there were also local charitable efforts, such as the widespread “Binxing Li” (scholarship charity activities) organized by local gentry to provide assistance for examination-related expenses. These charitable initiatives, along with government measures, supported disadvantaged examinees on their path to success in the imperial examination.

Affirmative action in the reform of the college entrance examination

Similarly serving the function of promoting social mobility, the college entrance examination also encompasses affirmative action for disadvantaged examinees. The forms of affirmative action in the college entrance examination system are fundamentally similar to those during the imperial examination system, with the presence of institutional guarantees, policy favoritism, and resource assistance. Moreover, it plays a crucial role in facilitating the path of academic advancement for disadvantaged examinees. Like the imperial examination system, the affirmative action within the college entrance examination system undergoes variations in emphasis during different stages of its reform, exhibiting distinct characteristics in each phase (as shown in Fig. 7).

Stage of emphasizing equality in rights (1949–1966)

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the emergence of affirmative action in the college entrance examination was a historical inevitability. On the one hand, under the planned economic system, China implemented a system of employment allocation for university graduates for a considerable period. For disadvantaged examinees, succeeding in college entrance examination meant escaping the fate of agricultural labor. In public perception, the college entrance examination, beyond being an entrance test for higher education, was also seen as a modern imperial examination capable of altering the destiny of disadvantaged examinees. On the other hand, the college entrance examination represented the right to education. In the design and implementation of the system, support for disadvantaged groups, including disadvantaged examinees, was deemed necessary to safeguard their educational rights. To preserve upward mobility pathways and educational rights for disadvantaged examinees, affirmative action in the college entrance examination emerged during this period.

During this phase, the earliest form of support was policy favoritism in affirmative action. Relevant enrollment regulations for colleges and universities before the formal establishment of the college entrance examination system already included provisions to favor disadvantaged examinees. In these regulations, disadvantaged examinees were categorized as part of the “workers and peasants students” group. For instance, the enrollment regulations in 1951 stated that students from working-class and rural families, as well as those engaged in related industries, should be supported, taking their actual situations into account. Admission standards could be lowered, and with “slightly lower scores,” applicants could still be admitted with leniency (Ministry of Education, 1951). Although execution standards were not explicitly stated, it indicated the early policy notion of favoring disadvantaged examinees in the spirit of the policy.

After the formal establishment of the college entrance examination system in 1952, policy favoritism primarily manifested through adjusting admission standards, providing support to disadvantaged examinees through score reductions and priority admissions. For instance, the supplementary regulations in 1954 regarding university admissions proposed special considerations and additional score allocations for rapid workers’ and peasants’ secondary school exam takers, further implementing the “opening doors to workers and peasants” policy (Ministry of Education, 1954).

Given the limited educational quality available to disadvantaged examinees, adjustments to the examination content were implemented. For instance, students with insufficient foreign language education could apply for exemption from the foreign language exam. Graduates from crash middle school for workers and peasants could have “separately formulated examination papers” (Ministry of Higher Education, 1955). The examination methods gradually evolved into a nationally unified enrollment system. In terms of examination venue arrangements, considerations were given to disadvantaged examinees in remote areas, facilitating them in saving travel expenses and avoiding accommodation issues, thereby reducing their economic burden (Ministry of Higher Education, 1956).

Due to overall shortages in educational resources, resource assistance constituted a crucial aspect of affirmative action during this stage. In terms of cultural resources, disadvantaged examinees could enter crash middle school for workers and peasants. These schools served as preparatory institutions for higher education, including affiliated schools and other types. Graduates meeting the requirements could directly enter corresponding universities for further studies. Even for those participating in the college entrance examination, there were policies supporting priority admissions. However, these schools had limited enrollment, existed for a short time, and therefore had limited impact. Economically, the state assumed the cost of higher education for disadvantaged examinees, alleviating their financial burdens. In 1952, two documents, “Notice on Adjusting People’s Aid Scholarships for National Higher Education Institutions and Secondary Schools” and “Notice on Adjusting Salary and People’s Aid Scholarship Standards for Educational Staff at All Levels Nationwide,” established the People’s Aid Scholarship system. The government provided financial aid to students to cover their living expenses during their studies (Sun, 2021). Through resource assistance measures, national policies sought to alleviate economic pressures for disadvantaged examinees, encouraging them to enter the examination hall and change their destinies.

During this period, affirmative action policies faced several challenges. For instance, the criteria for support were extremely vague, emphasizing the need to take care of workers and peasants. However, specific regulations regarding the extent of support, criteria for selecting beneficiaries, and similar matters were not clearly defined. This led to difficulties for relevant entities in implementing the support, making it challenging to grasp the standards and resulting in a one-sided emphasis on admitting workers and peasants. Moreover, the academic performance of disadvantaged examinees entering universities through methods like score reductions was generally lower. Consequently, there were issues with the improper distribution of majors during the voluntary allocation process (Ministry of Education, 1953).

The contradiction between the inadequate educational background of workers’ and peasants’ offspring and the quality of university enrollment was a challenge that affirmative action attempted to address during this period. The emphasis on supporting the exam enrollment of workers and peasants students to a certain extent resulted in substandard enrollment quality. Therefore, after the formulation of the policy of “ensuring quality while taking care of quantity,” national policies gradually attempted to create some tension in supporting workers and peasants students. For instance, in 1955, opinions on enrollment issues, regulations were added, stipulating that graduates of workers’ and peasants’ speed-up secondary schools who did not meet admission conditions should not be forcibly admitted. Moreover, the previous “lenient admission” for relevant examinees was changed to “priority admission” under equal performance conditions (Ministry of Higher Education Personnel Second Division, 1955). The policy design of affirmative action sought to strike a balance between safeguarding the educational rights of disadvantaged examinees and maintaining university enrollment quality. However, in the implementation process, this balance was challenging to maintain, especially at the institutional level, where enrollment quality was a primary concern. Therefore, after the introduction of the quality assurance policy, there were instances where some institutions used it as an excuse to reject qualified workers and peasant examinees (Ministry of Higher Education, 1956), hindering the implementation of affirmative action policies. On the other hand, due to the overall low level of basic education, the overall number of college graduates during this period was insufficient, and by 1956, there were only five university students per ten thousand residents. Despite various efforts to increase the proportion of workers and peasants in higher education, many disadvantaged examinees were unable to complete compulsory education, let alone meet the conditions for participating in the college entrance examination. Consequently, the impact of relevant policy support was limited on a large scale.

The affirmative action initiatives from 1949 to 1966 laid the foundation for the subsequent forms of affirmative action and accumulated practical policy experience. Although affirmative action during this period was not fully mature, it objectively enabled disadvantaged examinees to transform their fates through the college entrance examination. However, in the following decade, the college entrance examination was abolished, and a policy of university recommendation was adopted. During this time, the enrollment policy for the workers and peasants student population cannot be considered a form of affirmative action. Affirmative action serves as a further supplement to the fairness mechanism of examinations. With the cancellation of the college entrance examination system, there was no mechanism for fair competition in the recommendation-based enrollment system.

Stage of emphasizing fairness guarantee (1977–2011)

After the end of the “Ten Years of Turmoil,” the system of recommended university admission was abolished. The initial purpose of the recommended university admission system was to facilitate the enrollment of workers and peasants in universities. However, in practice, it gradually transformed into a system where admission was influenced by personal connections, prompting public dissatisfaction. There were reports of sentiments such as “before liberation, admission to university depended on money, during the seventeen years it depended on scores, and now it depends on connections… if you don’t have connections now, you can still get a place with scores” (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Ministry of Education, 1977).

In the reform and opening up, to rectify the unfair university admission practices, break down the class-based admissions, restore the credibility of the college entrance examination, and mobilize the enthusiasm of the masses, the post-reform college entrance examination first abolished all identity privileges. Simultaneously, it temporarily suspended some affirmative action policies for disadvantaged examinees. This approach faced criticism in the short term. For instance, at the 1978 National College Admissions Conference, debates arose over whether children of workers, peasants, and poor peasants should continue to receive special consideration, with this issue even being elevated to the level of national ideology (Ministry of Education, 1978). However, these voices were soon overshadowed by the fact that the proportion of disadvantaged examinees increased after the restoration of the college entrance examination.

During this phase, the policies for affirmative action did not exhibit explicit bias. After the reform and opening-up, with economic development taking precedence and the core values of the college entrance examination leaning towards efficiency due to national talent needs, the primary task of relevant reforms was to enhance the quality of admissions. Therefore, until the 1983 enrollment work report, there were no specific provisions for disadvantaged examinees at the national level. In the 1983 report, the Central Government suggested the promotion of “targeted enrollment and allocation” as a method to address the shortage of disadvantaged examinees (Ministry of Education,1983), enabling in-situ enrollment and allocation in rural areas. The regulations issued the same year provided more detailed provisions. For examinees under targeted enrollment, the score requirements could be lowered, and some students could be exempted from the foreign language exam (Ministry of Education, 1983). However, the limitation was that “targeted enrollment” was highly restricted in terms of majors, mainly focused on agriculture and forestry, and the enrolled students were required to return to rural areas. The early targeted enrollment did not emphasize the issue of admission identity significantly; it was relatively vague. Additionally, there was almost no specific policy support for impoverished or disadvantaged examinees during this phase.

The emphasis in this phase was on enhancing institutional guarantees. Efforts were made to rectify irregularities like using connections to secure admission and standardize the procedure of the college entrance examination. While examinees faced the same papers and scores for a time, artificial interventions in admission criteria, such as the practice of submitting notes or using connections, undermined the fairness of the college entrance examination. The central government not only repeatedly addressed these issues but also, from 1991 to 1995, promulgated a series of regulations, including the “National Uniform Examination Rules for Ordinary and Adult Higher Education Institutions,” the “Interim Regulations on Penalties for the Management of the National Uniform Examination for Admission to Ordinary and Adult Higher Education Institutions,” and the “Opinions on Further Strengthening the Management of the National Uniform Examination for Admission to Ordinary and Adult Higher Education Institutions.” These regulations strictly controlled various aspects of the college entrance examination, vigorously rectifying irregularities to create a fair environment for the examination. Similar to the control of bureaucratic interference in the imperial examination system during the examination system era, addressing irregularities in the college entrance examination was a crucial measure to combat illegal interference in the examination process, ensuring the legitimate examination rights of disadvantaged examinees.

During this period, the relatively limited scope of affirmative action for disadvantaged examinees can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the output of talent from rural education struggled to meet the nation’s selection needs. In the prolonged period after the initiation of reform and opening-up, basic education in many remote rural areas did not see substantial development until the 1990s. Ensuring universal nine-year compulsory education in rural areas became a primary task for educational development (Qu and Fan, 2011). The quality of talent output from rural areas needed improvement. However, the nation urgently required a rapid influx of talent to support its development. In such a situation, the fairness of the college entrance examination inevitably had to be compromised. Secondly, the task of the college entrance examination to select outstanding talent for the nation was clarified further. The outdated view that the college entrance examination was solely to ensure the right to education for the children of workers and farmers no longer held. The college entrance examination serves both as a university admission test and a mechanism for screening future talent reserves. Emphasizing its screening function is reasonable when there is an urgent need for talent supplementation. However, as the college entrance examination is also a vital mechanism for social mobility, with the expansion of university enrollment and the public’s increasing pursuit of educational quality, the focus on the efficiency-oriented nature of the college entrance examination is not expected to persist indefinitely. The issue of fairness in the college entrance examination will eventually become a core concern.

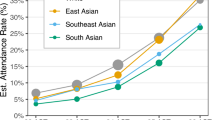

Stage of deepening equality of opportunity (2012–Present)

During this period, the connection between equal opportunities for admission and policy favoritism became more apparent. Affirmative action policies focused on addressing the enrollment issues of students in the central and western regions and vulnerable groups in rural areas. In this phase, the policy favoritism in affirmative action was mainly manifested through innovative enrollment policies designed to compensate and support disadvantaged examinees, with the most notable being the implementation of the “Three Major Special Plans.” The “Three Major Special Plans” refer to a new enrollment policy system composed of national special plans, local special plans, and university special plans. The national special plan is outlined in the “Notice on Implementing Special Plans for Targeted Enrollment in Poor Areas,” which independently sets admission criteria for examinees from 680 counties in 14 severely impoverished areas across 21 provinces (Ministry of Education et al., 2012). The university special plan refers to independent enrollment programs initiated by certain universities, such as Tsinghua University. These programs are primarily targeted at disadvantaged examinees from “old revolutionary base areas, ethnic minority regions, remote areas, and poor areas,” offering enrollment preferences in the form of score reductions. However, this policy is only applicable to a few universities and lacks universality. The local special plan is predominantly led by local universities at or above the first-tier level. These plans primarily serve local rural household registration examinees, and while specific regulations vary across regions, they generally include conditions like returning to the original residence for employment after graduation, reflecting a close relationship with the local economy. Except for the university special plan, which requires separate registration, the other two plans are implemented during the post-examination voluntary application stage.

Compared to previous targeted admissions, the “Three Major Special Plans” exhibit new characteristics in the development of policy favoritism within affirmative action. Firstly, the targeting of beneficiaries is more precise. In terms of identity verification, the “Three Major Special Plans” integrate with the national poverty alleviation criteria, allowing for precise identification down to the county level in administrative units. Rigorous proof of enrollment and other documents are required during the application process for identity verification, aiming to provide more opportunities for genuine disadvantaged examinees to access higher-quality education. Secondly, the goals of support encompass the quality of disadvantaged examinees’ university education. As the quantity of higher education institutions grows, aspirations for university education have shifted toward pursuing admission to prestigious universities. Therefore, the “Three Major Special Plans” do not provide additional points but directly ensure that qualified disadvantaged examinees can enter key universities through separate enrollment processes and opportunities for admission to prestigious institutions. This approach avoids the confusion caused by additional points.

Based on specific data, since the implementation of the special enrollment plan, the scale of admissions has continuously expanded, increasing from 10,000 students in 2012 to 122,000 students in 2021, with a total of over 820,000 students admitted. This has significantly increased access to quality higher education for students from rural and former poverty-stricken areas, with remarkable policy outcomes (Ding, 2022). At the provincial level, regions with lower economic and educational development have received more quotas. At the secondary school level, the distribution of quotas across high schools within counties has remained relatively balanced (with a Gini coefficient of less than 0.3). At the student level, nearly all admitted students have Gaokao scores below the general admission threshold, with disadvantaged examinees from impoverished backgrounds making up a significantly higher proportion (36.7–52.4%) compared to other admission types (10–15%). (Ma et al., 2021) However, the precision in awarding National Special Enrollment Plan quotas is not high; over 50% of students admitted under this plan come from families with relatively better economic and cultural capital, and urban household registrations. (Wen et al., 2018)

In recent years, some provinces have seen a significant increase in the number of students admitted under local special enrollment plans compared to other special plans. For example, in 2022, Hunan’s local special enrollment plan admitted 10,005 students, ten times the number of students admitted through its higher education special plan, and 7675 more than the national special plan, showing a 3055-student increase compared to the previous year, far exceeding the growth of other special plans. (Hunan Provincial Education Examination Authority, 2022) This number stabilized in subsequent years, with 9571 students admitted through Hunan’s higher education special plan, 7701 students admitted through the national special plan, and 9882 students admitted through the local special plan in 2023 (Hunan Provincial Education Examination Authority, 2023). Regionally, Shandong increased the number of counties implementing local special plans from 40 in 2021 to 63 in 2022, maintaining this number in 2024 (Shandong Provincial Department of Education, 2022 & 2024). From 2014 to 2022, Guangdong increased the number of counties implementing the special plan from 21 to 30, Shanxi from 22 to 26, and Shaanxi from 56 to 73. These figures remained stable in 2024. (Guangdong Provincial Department of Education, 2022), (Shanxi Enrollment Examination Management Center, 2022), (Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education, Shaanxi Provincial Education Examination Authority and Shaanxi Provincial Enrollment Committee Office, 2022). These figures largely remained stable in 2024.

In summary, the “Three Major Special Plans” represent a significant initiative in China’s educational equity efforts, marking a focus in the new era on developing education that is both more equitable and of higher quality (Li and Wu, 2020). This shift also signifies a critical development in China’s affirmative action, transitioning from enhancing competitiveness to improving actual outcomes.

Problems with current affirmative action in college entrance examinations

The college entrance examination has a history of over 70 years, and the framework for examination fairness has been substantially developed. However, in the context of China’s future promotion of equalizing the country’s basic public services and building a high-quality and balanced basic public education service system, the college entrance examination, as the “baton”, still needs to further play a supporting role in supporting disadvantaged examinees. In current practice, the relevant policy design of the college entrance examination has some problems that still need to be improved in terms of supporting disadvantaged examinees in the examination.

Decline in recognition of the existence of affirmative action

The imperial examination was regarded as one of the “key ways” for disadvantaged examinees to change their destiny. Although the children of the rich and powerful could participate in the imperial examinations, everyone from the emperor, the highest authority, to the common people was opposed to their admission, believing that it blocked the path for disadvantaged examinees to change their destiny. It was a common understanding that selective examinations should provide support to disadvantaged examinees, and no power could interfere with its legitimacy. At the same time, it also shows that during the imperial examination period, disadvantaged examinees had a higher status in the selective examinations, and people had high expectations for them to win the gold medal in the imperial examination.

At present, it is well known that disadvantaged examinees are in a disadvantaged position in the college entrance examination. It is increasingly difficult for children from poor families to enter high-quality universities, and the opportunities to change their destinies through education are gradually diminishing. However, while the public is still opposed to the huge pressure that educational involution has brought to students and parents, at the same time they are eager to participate in the involution, investing excessive resources in their children to achieve better results in a viciously competitive manner. It has become a widespread consensus that advantaged groups gradually gain a dominant position in the college entrance examination. The public sympathizes with the difficulties faced by disadvantaged examinees in getting into higher education, but they also believe that providing more support to them would run the risk of reverse discrimination. Disadvantaged examinees are no longer the “focal point” of selective examination services. The legitimacy of their support to improve examination results has been challenged, and deep examination fairness has been impacted. Currently, we should remain cautious about the tendency to overly focus on “top-performing students,” and instead pay greater attention to disadvantaged examinees, amplifying their voices.

Affirmative action lacks top-level design

The lack of top-level design means that in the design of the core system of the college entrance examination, less attention is paid to disadvantaged groups. Therefore, the dilemma of disadvantaged groups in the college entrance examination is only regarded as a phenomenon rather than a systemic flaw. The absence of top-level design in affirmative action has given rise to two key issues. One is that the integration of affirmative action and the exam system is low, and the other is that the sustainability of affirmative action is difficult to guarantee.

In the current context, higher education resources are increasingly intertwined with social mobility, placing a significant responsibility on the Gaokao to promote upward mobility. The Gaokao must undergo self-reform from the standpoint of social equity—specifically, it must embed fairness, particularly outcome fairness, as the core guiding principle in its institutional design. However, the current affirmative action measures are basically separated from the examination system. Whether it is financial subsidies or preferential treatment in terms of admission quotas, they are more of an assistance to the college entrance examination system. In other words, even if all relevant affirmative action is cancelled, the college entrance examination system can still operate normally and will still be regarded as “fair”. This is because there are differences in the top-level design between the imperial examination and the college entrance examination. When the imperial examination was first formed, it was to serve the disadvantaged examinees and take care of the interests of poor families in terms of core value orientation. However, the college entrance examination is essentially an enrollment system, and its social mobility function is related to subsequent higher education. The college entrance examination itself does not have social circulation attributes. Therefore, the original design of the college entrance examination was more inclined to achieve unified standards for all citizens, and less consideration was given to special care for a certain group of people. Even in the early days of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, there was special preferential treatment for workers and peasants’ children in the college entrance examination, but it was mostly due to political factors and did not go into the core of the college entrance examination system.

The sustainability of affirmative action refers to whether affirmative action can continue to improve and continue to exist after changes in the internal and external environment. This problem is caused by the high degree of change in modern society. In the feudal dynasty period when the social structure hardly changed, a single mechanism was enough to cope with a long period of time, so there was less need to consider these issues. As long as there are differences in social class, there will be disadvantaged groups in the college entrance examination. With societal development, the scope of the concept “vulnerable groups in the college entrance examination” will continue to evolve, and affirmative action based on identifying disadvantaged groups in the college entrance examination may face many problems. One of them is the “disappearance” of target beneficiaries. For example, the current “three major special plans” rely heavily on the state’s identification of poverty-stricken areas in the identification of support objects. After alleviating poverty, poor areas may disappear, but relatively disadvantaged student groups will still exist. How relevant affirmative action initiatives will continue to work may be a question. Due to the lack of top-level design planning, the current affirmative action lacks a long-term mechanism and can only passively respond to practical problems. There is a risk that new affirmative measures will often serve only as supplements to educational equity and struggle to actively influence it.

Affirmative action has uneven effects

The unequal effect of affirmative action means that due to factors such as regional differences, the same affirmative action measure has inconsistent effects on different individuals within disadvantaged examinees, that is, it has different levels of influence in different provinces or regions.

Take the “Three Major Special Plans” as an example. Different provinces have different implementation conditions and their effects are uneven. Although disadvantage students from different regions are eligible for this track, relatively advantaged groups still have an advantage. It can be seen that this design still follows the old logic of the ordinary college entrance examination. In fact, it has run counter to the original purpose and no longer aligns with the examination’s role of supporting and compensating the most vulnerable groups. It can only be regarded as a continuation of the ordinary college entrance examination.

On the other hand, due to the uneven distribution of higher education resources across provinces, there are also large differences in the specific implementation of local special plans. In provinces with scarce higher education resources, enrollment quotas often fail to meet local educational needs, forcing partial allocation to special program candidates. Overall higher education resources are stretched thin. Disadvantaged examinees in different provinces have different benefits from the three major special projects. It can even be called a large gap.

Conclusion and discussion

In recent years, affirmative action in global education has gradually diminished, and the challenges faced in achieving educational equity have become more complex. In contrast, affirmative action in China’s selective examinations has persisted for over a thousand years and continues to play a significant role in advancing educational fairness. In this context, analyzing the successes, shortcomings, motivations for continuation, and reform approaches of affirmative action in China’s selective examinations can help summarize the development patterns of related policies. Additionally, looking ahead to the future of compensatory and preferential distribution policies for higher education resources holds positive implications for achieving educational fairness for disadvantaged examinees worldwide.

Characteristics and impact of affirmative action in the imperial examination system

Affirmative action in the imperial examination system is characterized by its long duration and limited implementation effects. With the primary goal of maintaining a promotion pathway for disadvantaged examinees, affirmative action in the imperial examination system was continuously enriched and improved, completing a relay of examination fairness across multiple dynasties. However, these measures were also constrained by the political system of virtue-based governance. In terms of design, these measures were rarely systematized, creating contradictions with the efficiency of the selection process. For example, during the Song dynasty, the pursuit of fairness in the examination led to a narrowing of the subjects and content of the exams. While this benefited disadvantaged examinees by allowing them to rely on their talents to achieve success, it also diverged from the goal of selecting well-rounded individuals capable of governing the country. In contrast, the imperial examinations in the Ming and Qing dynasties were more balanced in ensuring fairness and guiding the holistic development of students (Yuan and Zhang, 2025).

There is a need to attend to the impact of power intervention on examination fairness. In terms of implementation, these measures were frequently influenced by bureaucratic power, limiting their effectiveness. The ongoing emphasis on the issue of fairness for disadvantaged examinees in historical records reveals that bureaucratic interference in the fairness of the imperial examination persisted despite repeated efforts to curb it. Although a variety of affirmative action measures existed, they were seldom formalized into fixed policy provisions, with their implementation left to the discretion of examiners and other officials. Moreover, due to the lack of robust supervision mechanisms, the actual impact of these measures was difficult to assess. Despite these challenges, affirmative action in the imperial examination system persisted and evolved across dynastic transitions. This endurance stemmed from the rulers’ needs and the disadvantaged examinees’ striving for equal access. The gradual shift of the examination system to favor disadvantaged examinees became a cultural norm. The initial purpose of establishing the imperial examination was to reduce the influence of aristocratic families on bureaucratic appointments and strengthen central authority. This goal led to the establishment and reinforcement of the dominant position of disadvantaged examinees within the imperial examination system. By allowing disadvantaged, lower-class examinees to change their social status through the imperial examination, the system promoted social mobility and worked to prevent the formation of new bureaucratic monopolies. This dynamic meant that any dynasty seeking to strengthen central authority via the imperial examination system had to prioritize fairness for disadvantaged examinees.