Abstract

The development of digital technology and its potential influence on social capital has become a nascent research topic, but scholars have been focusing on the role of Internet use and presented inconsistent findings. Our study improved the social capital theory and focused on online social networks based on mobile social network sites (SNS) and their shifts to offline social networks in the accumulation of social capital. Using a nationally representative Chinese sample from the Chinese General Social Survey (N = 12,010), we examined the relationship between WeChat, the most popular mobile SNS in China, and social trust and explored the mediating effect of offline social networks in the above association. The results indicated that WeChat use positively influenced individuals’ social trust, but the positive effect was not distributed among individuals, i.e., young adults, high-education adults, and urban residents gained more benefits from WeChat use. Moreover, WeChat use could promote social trust by enhancing individuals’ offline social networks. These findings helped to elucidate the linkage between mobile SNS use and social trust and uncover the formation mechanisms of social capital in the digitalized era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social trust refers to the reliance on the kindness of human nature that individuals place on strangers or most people in society (Xu et al. 2023). Trust plays a pivotal role in human social life, and it enables the maintenance of sustained interpersonal relationships, enhancing the development of cooperative behaviors and the accumulation of social capital (Temple and Johnson, 1998). Face-to-face interactions have been traditionally a crucial contributor to social trust because trust is built on the information individuals receive from others (Singh, 2012). However, human beings are undergoing a rapid digitalization transformation where communications between individuals have increasingly depended on digital technology. Notably, the Internet, as a media based on digital technology, has become an important tool for citizens to search for information and maintain social contacts and has advantages over traditional media (e.g., newspaper, radio, and TV) in the scope and speed of transmitting information, leading to a more influential impact on individuals’ psychology and behaviors (McDool et al. 2020; Vannucci et al. 2020).

While the significance of the Internet has received scholarly attention, there is still no consensus in academia on the role of Internet use in social trust. On the one hand, the Internet could promote information exchange and foster social contact (Quan-Haase and Wellman, 2004; Hampton and Wellman, 1999), thus expanding users’ networks of relationships and increasing their social trust levels (Fisman and Khanna, 1999; Quan-Haase and Wellman, 2004). On the other hand, the Internet contains large volumes of false information, which could shape users’ negative social attitudes and a decline in social trust (Wang and Emurian, 2005). Research conducted in China has also presented inconsistent findings. Wang and Zhou (2019) found a positive relationship between the frequency of Internet usage and social trust. However, another study using the same data revealed a negative effect of Internet usage on social trust among the youth (Zhao and Li, 2017). Also, recent research indicated that Internet usage is significantly negatively related to individuals’ trust in certain occupation groups, such as doctors (Zhang and Liu, 2021).

The main reason for the discrepancies in the findings above may be measurement errors on the Internet. Existing studies generally used whether or not to use the Internet to measure individuals’ Internet usage behavior. Obviously, this measure does not identify the nature of the information that individuals receive from the Internet, making it difficult to establish a causal association of Internet use with social trust. Indeed, the Internet has spawned a variety of functions in practical applications, such as work, entertainment, communication, and social networking, which produce different effects on individuals’ daily lives. Recent studies have highlighted Internet application scenarios and focused on the Internet’s specific functions and their effects on users’ attitudes and behavior (Leng et al. 2022; Liang, 2020).

This study focuses on the social networking function of the Internet and its influence on individuals’ social trust. The development of the Internet has precipitated the rapid ascendance of social network sites (SNS) as a novel mode of communication and a fast-rising platform for social interaction. Particularly, Mobile Internet, as a digital technology that allows people to access the digitized contents of the Internet via mobile devices (e.g., tablets, smartphones, and smartwatches), is being employed almost anytime and anywhere without any physical constraints. Hence, SNS based on the mobile Internet could expand online social networks and offer users more opportunities to connect with others. Although previous studies have identified positive social capital outcomes of SNS use (Ellison et al. 2007; Manago et al. 2012; Johnston et al. 2013), little effort has been made to identify the impact of mobile SNS on social trust. Furthermore, little attention was paid to China with the highest number of Internet and SNS users globally. According to The 54th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China, China’s Internet penetration rate rose from 45.80% in 2013 to 78.0% in June 2024, and the number of Internet users increased from 618 million in 2013 to 1100 million in 2024 (China Internet Network Information Center, 2024). Digital 2022: Global Overview Report showed that there were 4.62 billion SNS users worldwide by January 2022, representing over 58% of the global population. In particular, SNS users in China reached 960 million, about 68% of the total population (Datareportal, 2022). Therefore, this study raised the following question: Was there a positive or negative effect of mobile SNS use on social trust in China? What is a mediating mechanism in the relationship between mobile SNS use and social trust?

In response, our study improved the social capital theory and highlighted the roles of online social networks based on mobile SNS and their shifts to offline social networks in the accumulation of social capital. Following this new theoretical framework, we examined the relationship between WeChat (微信), the most popular mobile SNS in China, and social trust and explored the mediating role of offline social interactions by the analysis of a nationally representative Chinese sample from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), in the hopes of deepening our understanding of the formation mechanisms of social capital in the digital era.

Literature review and hypothesis

Mobile SNS use and social trust

Social capital is generally referred to the “resources embedded in one’s social networks, resources that can be accessed or mobilized through ties in the network” (Lin, 1999: 51). As a set of resources embedded in networks of relationships, social capital can be distinguished between structural and cognitive dimensions (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Uphoff, 1999): structural social capital concerns individuals’ behaviors and mainly consists of social participation through various kinds of interpersonal interaction; cognitive social capital stems from individuals’ perceptions resulting in trust, values, and beliefs that promote pro-social behavior. Social trust, as the key element of cognitive social capital, has received theorists’ attention. For instance, (Putnam et al. 1993: 67) have viewed social capital as all “features of social life—networks, norms, and trust—that enable participants to act together more effectively to pursue shared objectives.” Portes (1998) has argued that when members in the same network of relationships hold mutual trust, they can be considered to have a form of social capital that can be used as a valuable resource in the pursuit of their life goals. Our study focused on the cognitive dimension of social capital and investigated whether and how SNS use relates to social trust.

Given that social networks based on interpersonal communication are a prerequisite for the emergence of social capital (Bourdieu, 1987), scholars have explored the formation mechanisms of social capital from the perspective of social networks and provided numerous empirical evidence. Using data from the British Household Tracking Survey, Li et al. (2005) compared the effects of formal social networks, measured by civic participation, and informal social networks, measured by neighborhood interactions, on social trust and found that the latter can produce a more positive impact on social trust. This finding was supported by studies conducted in the Chinese context. Using a sample from urban residents in Guangdong Province, Li et al. (2008) found that a social network based on neighborhood relationships significantly increases residents’ social trust level in communities. Another study using data from the job search and social network (JSNET) revealed that resources and interactions are the mechanisms through which social networks positively affect social trust (Zou and Zhao, 2017).

The resources embedded in social networks are essential for individuals to increase their social trust. Despite differences in the strength of ties between individuals, both strong and weak ties provide all members of one social network with material and non-material resources. Specifically, groups formed by strong ties could offer emotional support, while groups formed by weak ties could provide heterogeneous information and perspectives (Leonard, 2004). Putnam (2000) also suggested that both social networks based on strong and weak ties enhance social trust. As for the pattern of social networks, research on social capital originally focused on offline social networks formed by individuals’ face-to-face interactions (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998), where the interaction process is generally constrained by time and space, thus restricting the potential of social networks to improve social trust.

However, the limitations of offline social networks can be compensated by online social networks based on SNS. There has been a trend that social interactions increasingly rely on SNS, and online social networks have emerged with the rapid development of the Internet. SNS enormously expands the spatial and temporal boundaries of communications compared to offline social interactions, allowing individuals to maintain existing close ties with acquaintances and build new connections with strangers (Hogan, 2008). This means that online social networks based on SNS encompass strong and weak ties, and thus, the use of SNS can enhance social capital (Williams, 2006), including social trust. An ethnographic study of a new residential area (“Netville”) that was wired with high-speed Internet access has suggested that residents with access to the Internet positively participate in online communities and socialize more frequently with their neighbors (Hampton and Wellman, 1999). Ellison et al. (2007) found that the use of Facebook could enhance both weak and strong ties among undergraduate students, helping them maintain relationships with former friends and classmates. The follow-up studies have provided consistent findings: active SNS users exhibit higher social trust levels. Studies conducted in developed countries (i.e., the US and South Africa) indicated that new social connections formed by SNS could enhance users’ social trust (Quan-Haase and Wellman, 2004; Manago et al. 2012; Johnston et al. 2013). A recent study using data from Chinese Internet users revealed that individuals’ participation in SNS could contribute to connecting with others, sharing information, and seeking support during the COVID-19 pandemic, which helps them build social trust (Gong et al. 2025).

Mobile SNS has been a new communication channel with the development of mobile Internet and the popularity of s portable electronic devices, such as smartphones, smartwatches, and Tablets. Compared with using SNS on personal computers (PC), mobile SNS can increase the enjoyment and convenience of users by allowing them to connect with their relatives, friends, colleagues, and others at any time without physical constraints (Zheng and Lee, 2016). Thus, mobile SNS may have more influential impacts on the expansion of online social networks than SNS based on PC, but it remains unclear whether people’s social trust is connected to their use of mobile SNS.

The current study focused on WeChat to examine the impact of mobile SNS on social trust in the Chinese context. WeChat was launched in 2011 and has been the most popular mobile SNS in China. In the second quarter of 2024, the number of monthly active users of WeChat reached 1.37 billion (Tencent, 2024). During the same period, the usage rate of mobile SNSs, including WeChat, accounted for 98% of the Chinese netizens (China Internet Network Information Center, 2024). Indeed, WeChat is a messaging and calling app that includes a variety of social features, making it a full-fledged social media platform. Users can send voice and text messages, make voice or video calls, make payments, share photos, play mobile games, and connect with nearby strangers.

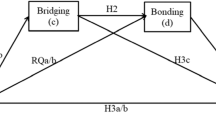

Unlike other mobile SNSs, such as Weibo (微博), WeChat has a unique approach to connecting relationships. Specifically, users on WeChat must connect with others by searching for specific identifiers (e.g., WeChat ID, QQ numbers, or mobile phone numbers), which are provided by others who have interacted with users. Hence, WeChat is treated as an online extension of existing social networks between acquaintances. Also, those connections with strangers formed by WeChat can turn into social networks between acquaintances through consistent online communication. In contrast, linkages formed by Weibo, as a public SNS, are more random and anonymous (Gan, 2018). Additionally, WeChat offers a more intimate social space and facilitates frequent interactions between users and expand their social networks (Zhao and Wang, 2013). Recent studies have validated the essential role of WeChat in strengthening social networks. A natural experiment conducted among college students revealed that both users’ social performance on WeChat groups and private interactions on WeChat are positively related to the assistance users receive from their WeChat friends (Li and Weng, 2022). Given that social networks are essential to the formation of social capital, including social trust, and WeChat can expand individuals’ social networks by fostering their weak and strong ties, we suggested that WeChat use could enhance individuals’ social trust. Thus, the following hypothesis could be proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). WeChat use was positively associated with individuals’ social trust in China.

The mediating role of offline social networks in the relationship between mobile SNS use and social trust

Social interaction is a classical perspective that examines the formation mechanism of social trust. Luhmann (1979) argued that trust is essentially a social relationship that stems from interactions and a mechanism for simplifying communication complexity. Barber (1983) also suggested that trust is an expectation that people develop through social interactions, which needs to be reinforced through continuous interactions. Some Chinese scholars, represented by Yang (2008), believed that social trust among Chinese is determined by the proximity of the relationship, i.e., the level of social trust would progressively decrease as the interaction boundary moves outward. In sum, both Western and Chinese scholars have acknowledged the significance of social interactions to the formation of social trust.

The development of digital technology has dramatically expanded the space of human activities, thus accelerating the integration of the absent cyberspace and the present geospace. Particularly, the emergence of SNS provides a platform for communication without time and space limitations, thus resulting in fundamental changes in the way individuals interact with others, i.e., a transformation from offline social interaction to online social interaction (Subrahmanyam et al. 2008). In such a context, the association between offline and online social networks has attracted theorists’ attention. According to the “social compensation” theory, online social interactions have the advantages of convenience and efficiency of communication over face-to-face interactions, thus expanding the scale of individuals’ offline social networks (Lin, 2001). This theory has been improved by the “network stimulation” theory, which suggests that online social networks can compensate for offline social networks that are constrained by physical limitations, thus maintaining strong relationships and converting weak ties into strong ones (Donath, 2007).

Empirical studies conducted in developed countries have provided consistent evidence, indicating that online social networks on SNS have the positive effect of maintaining and enhancing offline social networks. Wellman et al. (2001) found that online social interactions do not decrease the frequency of face-to-face or telephone communications but promote participation in community activities, such as voluntary and voting activities. Boneva et al. (2006) found that the use of instant messaging software can help college students maintain emotional linkages with their high school classmates and foster continued face-to-face interactions. Recent research using data from Facebook users revealed that computer-mediated communication (CMC) competence was associated with interpersonal competence, and interpersonal competence contributed back to CMC competence (Bouchillon, 2022).

In China, although little research examines the direct impact of online social networks based on SNS on offline social networks, there has been empirical evidence of the linkage between Internet use and offline social networks. Huang and Gui (2009) found that the Internet can help residents participate in the governance of public affairs in communities, and integrating online and offline social networks can mobilize collective action within communities. Zhou and Fu (2021) concluded that Internet use promotes face-to-face interactions between individuals and their neighbors. However, Liu and Keng (2016) found that Internet use has no significant role in community engagement in China. The reason for the inconsistent conclusions in existing studies may be that they have not distinguished between the specific functions of the Internet, leading to inconsistent findings across different datasets. It is worth noting that recent research has identified a shift between online and offline social networks. Using data from the JSNET, Bian and Miao (2019) found that about 25% of urban residents’ online social networks among friends could turn into offline social networks among friends by using SNS.

As online social networks based on WeChat are formed by relationships between acquaintances, the use of WeChat can facilitate face-to-face interactions between users and expand their offline social networks. In addition, given that offline social networks have been treated as a fundamental element of social trust (Lin, 2001), online social networks based on WeChat may enhance individuals’ social trust through their positive influence on offline social networks. Therefore, the following hypothesis could be proposed in this study:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The relationship between WeChat use and social trust was mediated by offline social networks in China.

Disparities in the social trust outcome of SNS use: the role of socio-demographic characteristics

Although digital technology could produce positive outcomes in economic, social, political, and institutional fields of activity (Van Deursen and Helsper, 2015), not all users benefit equally from digital technology due to digital inequalities, which is understood as “the disparities in the structure of access to and use of information and communications technology (ICT)” as well as “the ways in which longstanding social inequalities shape beliefs and expectations regarding ICT and its impact on life chances” (Kvasny, 2006: 160). Digital inequalities are generally described as three levels of digital divide in existing literature (Lutz, 2019). The first-level digital divide concerns differences in individuals’ access to digital technology, including such dimensions as autonomy and continuity of access (Van Dijk, 2005). As more and more people obtained access to digital technology, the second-level digital divide in skills and usage patterns became more evident and drew more attention from scholars (Zillien and Hargittai, 2009). Research on the second-level digital divide has focused strongly on individuals’ online activities for recreational purposes and outside of work (Lutz, 2019). The third-level divide, as an extension of first- and second-level divides, refers to disparities in the gains from digital technology use within populations of users who exhibit broadly similar usage profiles and enjoy relatively autonomous and unfettered access to digital technology (Van Deursen and Helsper, 2015).

Resource and appropriation theory provides a framework for analyzing the formation logic of three levels of digital divide (Van Dijk, 2005). The core argument of the theory is that personal (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, personality, and health) and positional (e.g., education, occupation, and geographic location) differences across people produce inequalities in the distribution of resources (e.g., intelligence, income, and social network) which cause inequalities in the appropriation of digital technology. Hence, digital inequalities mirror existing social inequalities. More specifically, traditionally disadvantaged individuals are similarly disadvantaged in the access and use of digital technology and do not reap the returns from digital technology to the same extent as more advantaged groups (Blank and Lutz, 2018; Van Deursen and Helsper, 2015).

Digital divide research has documented several socio-demographic variables related to differences in these offline resources, which are linked to differences in the access and use of digital technology; the ones most commonly examined are age, education, and geographic location (Van Deursen and Van Dijk, 2014). Age has proven to be a strong predictor of the use and skills of digital technology across many studies: younger users are typically more active and skillful (Bridges et al. 2012; Jugert et al. 2013). Education is the core measure of socio-economic status (SES). Previous literature has shown that individuals with high SES not only have more access to the Internet but also possess the necessary skills to use the Internet (Gui and Argentin, 2011). There is also a geographic pattern of the digital divide. For instance, the global divide is still very large, mirroring economic and social gaps between developed and undeveloped countries (Cruz-Jesus et al. 2018). Even in developed countries such as the US, people in rural areas have less access to high-quality Internet connections and show low levels of digital skills (Hale et al. 2010; Stern et al. 2009).

Distinct from the first and second-level digital divide, the third-level digital divide is associated with gaps in individuals’ capacity to translate their digital technology access and use into favorable offline outcomes. Research on the third-level divide, therefore, seeks to tackle the question of “Who benefits from using digital technology?” (Van Deursen and Helsper, 2015). Previous studies have suggested that advantaged users manage to use the Internet more productively and reap greater returns from its use than disadvantaged users (Bonfadelli, 2002; Zillien and Hargittai, 2009). For example, Van Deursen and Helsper (2015) found that younger and high SES users benefit more from using the Internet than older and low SES users in the Netherlands with near-universal Internet access. Blank and Lutz (2018) also found that highly educated users benefit most from using the Internet in the UK with a well-developed digital infrastructure. Moreover, those privileged individuals who profit disproportionately from digital technology can leverage these benefits to strengthen their SES, thus exacerbating existing social inequalities (Van Dijk, 2005).

In our study, individuals’ socio-demographic characteristics might shape social trust dynamics through WeChat use. Indeed, social trust, as the most economically relevant aspect of social capital, is the offline outcome of the access and use of digital technology in the social field. Studies of social outcomes have shown a range of returns accruing to the digitally advantaged, including increased contact with family and friends and the creation of new friendships or romantic relationships online that continue offline (Muscanell and Guadagno, 2012; Van Deursen and Helsper, 2015). It is noteworthy that the third-level digital divide has become increasingly salient in societies where access to digital technology is very widely diffused within the population because they enjoy unfettered access to the Internet and social media. (Lutz, 2019). Thus, there may be a new third-level divide concerning disparities in the returns, such as social trust, from WeChat use as the population has accessed and used WeChat in China. Given that digital inequalities, particularly the third-level divide, mirror offline social inequalities, the social trust outcomes of WeChat use may not be evenly distributed among individuals with different socio-demographic characteristics. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The effect of WeChat use and social trust was heterogeneous for groups with different socio-demographic characteristics.

Method

Data

The data employed in this paper came from the CGSS, one nationally representative continuous cross-sectional general survey designed and conducted by Renmin University of China. As the first national social survey project covering 31 provincial units in China, the CGSS was carried out in 2003, followed by eleven waves in 2005, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2018, and 2021. Using a multi-stage stratified national probability sampling method, each wave of the CGSS collects information on more than 10,000 sample households and family members in mainland China. In the current study, we used the 2018 wave of the CGSS containing 12,787 individuals to examine whether and how mobile SNS affects social trust because items on WeChat use are designed in the CGSS2018. After dropping missing values and outliers, a total sample of 12,010 individuals was obtained.

Measures

Dependent variables

The dependent variable was social trust. Following previous literature using the CGSS (Xu et al. 2023), social trust was measured by a question, i.e., “Do you agree with the following statement that almost all the people in society are trustworthy?” The responses to this item were rated on a five-point scale from strongly disagree, relatively disagree, neither agree nor disagree, relatively agree, and strongly agree, which were assigned a value of 1–5, respectively.

Independent variables

The independent variable was WeChat use. In the CGSS2018, WeChat use can be measured by this item, i.e., “Have you been using WeChat in the past year?” We assigned 0 to the answer “no” and 1 to the answer “yes.”

Mediating variables

The mediating variable was offline social networks. Referring to Zhao et al. (2024), offline social networks could be measured by the frequency of face-to-face interactions between respondents and others, and the measurement item was “In the past year, did you often socialize/visit people (relatives, friends, and colleagues, etc.) in your free time?” Responses to this item were ranked on a seven-point scale, from never, once a year, a few times a year, once a month, a few times a month, once or twice a week, and almost every day, which were assigned a value of 1–7, respectively.

Control variables

The following variables were controlled in the empirical analysis: gender (male = 1, female = 0), age, religious belief (have = 1, not have = 0), marital status (married = 1, not married = 0), Hukou status (urban = 1; rural = 0), education level (years of formal education), political status, employment status (employed = 1, unemployed = 0), occupational status, self-rated health, mental well-being, residence location (urban = 1; rural = 0), Internet use, and annual personal income. Political status was measured by whether respondents were members of the Communist Party of China (CPC) (CPC member = 1; non-CPC member = 0). Occupational status was measured by the International Socioeconomic Index. Self-rated health was measured by a five-point Likert scale coded from 1 (unhealthy) to 5 (very healthy). Mental well-being could be measured by the respondents’ self-reported depression levels following previous literature (Liu and Zhang, 2024). In the CGSS, the measurement item on depression was “How often have you felt depressed in the past four weeks?”, which had five ordered response categories: “Always”, “Often”, “Sometimes,” “Rarely,” and “Never” Internet use was measured by the item, i.e., “In the past year, how did you use the Internet?”, and the answers were “never, rarely, sometimes, often, very frequently,” assigned as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 in turn. Personal income was measured by the natural logarithm of the respondents’ total income in the last year. Province dummies were also included in the regression model to control for the regional effects. The descriptive statistics of the main variables were reported in Table 1.

Analytic strategies

First, given the ordinal nature of the dependent variable, the Ordered Probit (OProbit) model was employed to estimate the effect of WeChat use on social trust. The model was specified as follows:

Where \({{ST}}_{i}\) represented the social trust level of individual i; \({{WU}}_{i}\) represented whether individual i uses WeChat; \({X}_{i}\) represented a series of control variables; \({\varepsilon }_{i}\) was a normally distributed mean-zero error term. If \({\beta }_{1}\) was positive and statistically significant, there was a relationship between WeChat use and social trust. Furthermore, we tested the robustness of the influence of WeChat use on social trust by performing several approaches, including the instrumental variable (IV) method, propensity score matching (PSM) method, and the replacement of models and variables,

Second, we used the Baron and Kenny (BK) method to test the potential mediation effect in the relationship above (BK, 1986). The specific formula was as follows:

Where \({{OSI}}_{{it}}\) represented the measure of offline social networks. Following the previous research (Liu and Zhang, 2024), we tested the mediating effect of offline social networks according to the two principles: first, offline social networks should correlate with both WeChat use and social trust; second, the inclusion of offline social networks in the regression as an additional control should decrease the magnitude of the coefficient on WeChat use or render it statistically insignificant.

Furthermore, two other methods were used to test the mediating effect. On the one hand, the Sobel test was used to see if the reduction in coefficient is statistically significant and verify the mediating effect of offline social interactions (Sobel, 1986). On the other hand, the KHB method allowed us to unbiasedly decompose the direct and indirect (mediating) effects and test the significance of the effects (Kohler et al. 2011).

Results

Baseline regression results

The results using the OProbit model for the relationship between WeChat use and social trust were shown in Table 2. When there were no covariates in Model 1, the coefficient on WeChat use was 0.176 and statistically significant at the 1% level. We further added a series of control variables in Models 2 and 3 and found a significantly positive linkage between WeChat use and social trust. Taking the regression results in Model 3 as an example, the coefficient for WeChat use increased to 0.243 and was statistically significant at the 0.1% level. The results showed that WeChat use was positively and significantly associated with individuals’ social trust, indicating that WeChat users were more likely to trust almost all the people in societies than individuals without using WeChat. This finding provided support for H1.

The results for control variables were generally in line with existing literature (Huhe, 2014; Su et al. 2019). We observed that older respondents had higher levels of social trust. Those with religious beliefs have a higher social trust level than those without religious beliefs. There is a significant positive relationship between education levels and social trust. This may be because individuals with high human capital measured by education have an improved ability to screen information, which helps them avoid false information and trust others. CPC members exhibited higher levels of social trust compared to non-members. The higher the respondents’ self-rated health status and mental well-being were, the higher their social trust levels. The social trust level of urban residents was significantly lower than that of rural residents. It is worth noting that, distinct from existing literature (Ellison et al. 2007; Wang and Emurian, 2005; Wang and Zhou, 2019; Zhao and Li, 2017; Zhang and Liu, 2021), we did not find a significant influence of Internet use on social trust when concerning the effect of WeChat use, which implied that mobile SNS use had a closer relationship with social trust than Internet use.

Robustness test results

Addressing endogeneity concerns

The baseline regression results on the association between WeChat use and social trust may be biased due to the following two endogeneity problems. First, the reverse causality problem may arise: individuals with high levels of social trust are more willing to socialize with others and more frequently use WeChat. Second, multiple factors would influence social trust, and WeChat use could be associated with other unaccounted variables influencing social trust, thus resulting in the omitted variable bias. An IV method was used to solve the potential endogeneity issue. Following previous research (Zhang et al. 2023), the Internet penetration rate at the province level (IV_IPRC) was selected as an IV for WeChat use. This decision resulted from the fact that while respondents’ WeChat use would be related to the Internet development of a region where they live, individuals’ social trust would not be affected by one region’s Internet penetration rate. Consequently, the selected IV accorded with the relevance and validity criteria and has been employed in previous literature (Zhang et al. 2023).

Following prior studies (Deng and Yu, 2021), the method for estimating the IV model was a two-stage least squares (2SLS). The results using a Probit regression of the IV (i.e., IV_IPRC) and WeChat use were shown in Model 1 of Table 3. We observed that the coefficient for IV_IPRC was positive and statistically significant (p < 0.001), thus confirming the relevance criteria. According to the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test for endogeneity, the null hypothesis of the exogeneity of WeChat use was rejected at the 0.1% level at least, demonstrating that there may be an endogeneity problem in the baseline regression results (see Model 3 of Table 2). IV_IPRC was not a weak IV since the Wald F statistics in the first-stage regression were higher than the general standard of 10 for a weak instrument hypothesis. In Model 2 of Table 3, the coefficient on WeChat use was significantly positive at 0.1% level, indicating a positive effect of WeChat use on individuals’ social trust.

Addressing sample selection bias

There may be selection bias in the baseline regression results since individuals with and without the use of WeChat may differ systematically from each other. We performed a PSM approach to solve the problem above. According to the dependent variable (i.e., WeChat use), we treated individuals who were using WeChat as the treatment group and individuals who were not using WeChat as the control group. For each treatment sample, we employed four matching algorithms, i.e., nearest neighbor matching (NM), radius matching (RM), kernel matching (KM), and local linear matching (LM). These methods were used to select a matched sample with the closest propensity score, which was predicted using a Probit model assessing the likelihood of an individual using WeChat. Imposing the common support restriction to improve the quality of the matches, the ATT was shown in Table 4. It could be seen that ATT in all models was positive and statistically significant at the 0.1% level, indicating that the social trust level of individuals who use WeChat was higher than those without using WeChat.

Alternative models and measures

We conducted a battery of robustness tests by replacing models and variables. First, referring to existing literature that uses ordinal variables as the dependent variables (Xu et al. 2023), we replaced the OProbit model with the ordinary least Square model and re-ran the regression on the sample. The results in Model 1 of Table 5 showed that the coefficient of WeChat use remained positive and significant at the 0.1% level, which was in line with our baseline regression results (see Model 3 of Table 2).

Second, we used alternative measures of the independent and dependent variables. On the one hand, the use of WeChat can be measured by the number of WeChat friends, which could effectively reflect the status of individuals’ online social networks based on mobile SNS (Ju and Tao, 2017). Given that the maximum number of WeChat friends is limited to 5000, we excluded the observations that exceeded this limit. In addition, we winsorized the top and bottom 5% of WeChat friends, thus alleviating the influence of extreme values on estimations. Moreover, the natural logarithm of WeChat friends was used in regression models. It could be seen that the coefficient for WeChat friends was positive and statistically significant at the 0.1% level in Model 2 of Table 5.

On the other hand, following previous studies (Zhao et al. 2024), we converted social trust levels to social trust tendencies. Specifically, since the response of “neither agree nor disagree” does not reflect a tendency to trust, we assigned it a value of 0 along with those who answered “strongly disagree” and “relatively disagree” and a value of 1 for “relatively agree” and “strongly agree”, indicating whether the respondents have the tendency of social trust. We found that the coefficient for WeChat was positive and statistically significant at the 0.1% level in Model 3 of Table 5. Obviously, the results using alternative indicators for key variables in Table 5 were consistent with the results in Table 2.

Main effects test using new data

New data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) were employed to verify the main effects of WeChat use on social trust. The CFPS is a national longitudinal survey project conducted by the Institute of Social Science Survey of Peking University. The CFPS was officially launched in 2010 and is conducted every two years. We used data from CFPS2020 because the items on WeChat use were only designed for this wave of the CFPS, in which 44,000 individuals from about 15,000 families were interviewed successfully. Data from the CFPS2020 was not included in our analysis of the mediating role of offline social networking because there were no measures of the mediating variables in the 2020 wave of the CFPS.

The measures in the CFPS2020 were as follows: First, a dummy variable was constructed using the question, “Do you like to trust or doubt people?”, and respondents who chose “Most people can be trusted” had higher social trust and were assigned a value of 1, whereas respondents who chose “Be as careful as possible” had a lower social trust and were assigned a value of 0. Second, WeChat use could be measured by two indicators in the CFPS2020. One was whether to use WeChat, which is identical to the item of the CGSS2018, i.e., “Have you been using WeChat in the past year? (1 = yes, 0 = no)”. The other one was the frequency of using WeChat Moments (微信朋友圈), whose item was “How often did you share your work or life in Moments in the past year?”. The options ranged from “almost every day” to “never”. A higher score indicates higher sharing frequency in WeChat Moments. Third, we controlled for other variables that were identical to those in the CGSS2018.

After excluding individuals aged below 16 and dropping the samples with missing values (unknown) and abnormal values (inapplicable), 12,554 observations were obtained from the CFPS2020. Based on the sample, the results using the Probit model showed that the two indicators of WeChat use were significantly positive at the 1% level (see Table 6), which had a similar pattern to the baseline regression results from the CGSS2018 (see Table 2).

Mediation analysis results

We further examined the mechanisms through which WeChat use influences one’s social trust. In the section on theoretical analysis, we illustrated the logic of mobile SNS affecting social trust from the perspective of offline social interactions. First, the BK method was employed to examine the mediating effect of offline social interactions. The results were presented in panel A of Table 7. In Model 2, the estimated coefficient for WeChat use was significantly positive at the 0.1% significance level, indicating that the use of WeChat could promote individuals’ offline networks. Model 3 showed results that included the mediator as an additional covariate. We found that the coefficient for the mediating variable (i.e., offline social networks) was positive and significant at the 0.1% level, suggesting that it enabled individuals to trust the majority of people in a society. Notably, the inclusion of the mediator as an additional covariate reduced the magnitudes and significance levels of the coefficients for WeChat use, which was evident when we compared Models 1 and 3 of Table 7. The results demonstrated that WeChat use could increase individuals’ social trust levels through offline social networks.

Furthermore, the coefficients of Sobel in Panel B of Table 7 were significant at the 0.1% level, which means offline social networks were an effective mediator between WeChat use and social trust. According to the KHB estimation results in Panel C of Table 7, the total effect, direct effect, and indirect (mediating) effect were positive and significant at 0.1% level. The results also showed that the mediating effect of offline social networks accounts for 36.6% of the total effect of WeChat use on social trust levels. Therefore, we found supportive evidence for H2.

Heterogeneity analysis results

The above analysis has confirmed a significant positive effect of WeChat use on social trust, but it could not uncover differences between groups. Indeed, individuals with different socio-demographic characteristics have different opportunities to access and use digital technology, thus producing gaps in social outcomes of WeChat use among individuals with different characteristics. Consequently, following previous studies (Zhang et al. 2024), we conducted heterogeneity analysis on the three characteristic variables, i.e., individuals’ age, education level, and place of residence, and explored the structural differences in the impact of WeChat use on social trust.

First, we examined age heterogeneity. Consistent with the definition that is employed by the National Bureau of Statistics in previous studies (Liu and Zhong, 2023), the sample in our study was divided into three age subgroups: young adults whose age was below 36, middle-aged adults whose age was between 36 and 59, and older adults whose age was over 59. The results in Model 1 – 3 of Table 8 indicated that the coefficients for WeChat use were significant only in the young age group while insignificant in the middle-aged and older groups. Second, following existing literature (Wen et al. 2023), we represented the regression results of high- and low-education groups based on their median education levels to examine the influence of heterogeneous education levels. The results in Models 4 and 5 of Table 8 revealed that the positive effect of WeChat use on social trust only existed in high-education individuals. Third, we divided the sample into two groups, i.e., rural and urban subgroups, and looked at the heterogeneity of residence location. The results in Models 6 and 7 of Table 8 indicated that WeChat use positively affects social trust in the urban group but has no significant impact in the rural group. These results suggested that people with socio-demographic advantages have more access and use to digital technology and gain more social trust benefits by using WeChat than those with socio-demographic disadvantages. Thus, there is a new pattern of the third-level digital divide that is reflected by gaps in social trust returns from WeChat use. It supported H3.

Discussion

Given the trend of the digitalization transformation and the change in the way of communications due to the use of digital technology, exploring whether and how mobile SNS, a main social platform in a digitalized society, affects the accumulation of social capital is becoming increasingly important. Using a nationally representative Chinese sample from the CGSS, this study attempted to examine the relationship between WeChat, the most popular mobile SNS in China, and social trust and explore the mediating role of offline social networks in the relationship above. We obtained the following key findings based on empirical results.

First, the baseline regression results indicated that WeChat use has a significant positive relationship with social trust. The results of the robustness test using multiple approaches, including the IV method, PSM method, the replacement of models and variables, and using new data, also showed that WeChat use could promote social trust. This finding deepened the understanding of the linkage between digital technology and social capital. While scholars have paid a large amount of attention to the influential impact of digital technology on the accumulation of social capital, they only used Internet use as the measure of digital technology, thus making it difficult to identify the function of digital technology and resulting in inconsistent conclusions (Ellison et al. 2007; Wang and Emurian, 2005; Wang and Zhou, 2019; Zhao and Li, 2017; Zhang and Liu, 2021). In contrast, we measured digital technology from the perspective of the specific function of the Internet and examined the association between mobile SNS, an Internet application with the social networking function, and social trust. Hence, our study provided new evidence for the association between digital technology and social capital and demonstrated the key influence of mobile SNS on increasing individuals’ social capital. In addition, our findings showed the positive impact of SNS use on individuals’ social attitudes (Wang et al. 2014; Wen et al. 2016), thus not supporting the “time-displacement hypothesis” (Putnam, 2000) or the anxiety about “antisocial networking” (Brandtzæg, 2012), which is concerned that SNS users are more isolated and less connected than non-SNS users are.

Second, the results of using three mediation test methods, i.e., the BK method, the Sobel test, and the KHB method, showed that the use of WeChat promoted individuals’ offline social networks and further increased their social trust. In other words, WeChat use affects individuals’ social trust mainly through their offline social networks. While theorists within sociology and political science have acknowledged the key role of social interactions in the formation of personal trust (Luhmann, 1979; Barber, 1983; Yang, 2008; Putnam, 2000), there is little attention on the transformation of interaction channels from offline interactions to online interactions and its influence on social trust. However, our study revealed that virtual social platforms constructed by mobile SNS broaden the channels of social interactions, thus providing a real space for individuals to communicate through face-to-face interactions and increasing their trust in others in societies. In that sense, mobile SNS has the function of transforming online social networks into offline social networks based on face-to-face interactions, which is consistent with previous studies concerning the association between Internet use and offline social networks (Huang and Gui, 2009; Zhou and Fu, 2021). In sum, our study clarified the literature of social networks and simultaneously focused on online and offline social networks, thus uncovering the logic of the social trust effects of mobile SNS use and providing insights into the formation mechanism of social capital in the digitalized era.

Third, we observed meaningful differences between subgroups divided by individuals’ age, education level, and residence location. The heterogeneity results of age indicated that WeChat use was significantly associated with social trust among young adults. This may be due to the fact that the young are tech-savvy “digital natives” (Prensky, 2001), i.e., this group is more willing to access new digital technologies and communicate with others in virtual communities provided by mobile SNS than middle-aged and older adults (Zhang et al. 2024). The heterogeneity results of education level showed a positive impact of WeChat use on social trust among individuals with high education levels. Generally, a higher level of human capital can help individuals learn more digital skills (Pea et al. 2012), thus efficiently employing smartphones or tablets and communicating with others on social platforms based on mobile SNS. The heterogeneity results of residence location suggested that the social trust effect of using WeChat is significant for individuals who live in urban areas. This may be due to a huge “digital divide” between urban and rural residents. In China, the inequalities in economic and social resource distribution between urban and rural areas lead to the underdevelopment of Internet-related services and industries and a lower Internet penetration rate in rural areas (Zhang et al. 2023). Due to the insufficiency of a digitalized environment, rural residents exhibit a lower level of digital literacy and face greater challenges in using digital technology represented by mobile SNS. Combining all heterogeneity results, we believed that the differences in individual and regional characteristics could lead to an unbalanced distribution of the social trust effects, i.e., those with more opportunities to access digital technologies and higher levels of digital skills can enjoy the benefits of using mobile SNS and accumulate more social capital by promoting social trust. Indeed, previous studies conducted in developed countries have documented the third-level digital divide reflected by the gap in the returns of Internet use between advantaged and disadvantaged groups (Van Dijk, 2005; Van Deursen and Helsper, 2015; Blank and Lutz, 2018). In contrast, our study showed a new form of the third-level digital divide in China, where social trust outcomes of WeChat use were unequally distributed among individuals with different socio-demographic characteristics, thus indicating a salient digital inequality in developing societies.

Our study had several limitations. First, the results of the current study were based on a cross-sectional survey, making it difficult to examine a causal linkage between WeChat use and social trust. However, we employed some causal identification strategies, such as the IV and PSM methods, to ensure the robustness of the baseline regression results. Certainly, a longitudinal design in future research helps to make stronger causal inferences. Second, constrained by the availability of variables, our study only selected whether to use WeChat and the number of WeChat friends as the measure of WeChat use. However, previous studies have shown that both the intensity and motivations of WeChat use have impacts on individuals’ psychological well-being (Wen et al. 2016), which is a key influencing factor of social trust. Thus, a more nuanced measure of mobile SNS use should be included in future research. Third, we only examined the impact of WeChat use on social trust in China. Indeed, WeChat has more than 1 billion monthly active users worldwide and covers over 200 countries by 2022 (Datareportal, (2022)). However, it remains unclear whether the conclusions drawn from the analysis of WeChat can directly extend to research on other mobile SNSs, such as Twitter, WhatsApp, and Instagram. Moreover, as the findings in our study were derived from Chinese samples, it is necessary to conduct new research to identify their applicability to individuals in other developing or developed countries.

Despite these limitations, this study offered important policy implications for the increase in social trust and accumulation of social capital by promoting the digitalization transformation and narrowing the digital divide. First, given that mobile SNS have become a vital medium for social interactions and a source of information, policymakers should drive high involvement and extend the range of social features to attract additional users, thus promoting the integration of all individuals into the new digital life. Second, it is necessary to focus on the disadvantaged groups in the digitalization transformation, including older adults, low-education adults, and rural residents, so as to avoid social inequality related to the digital divide. For instance, the government should promote knowledge of digital technology to older and low-education adults and encourage them to use mobile SNS. Governments should also increase the Internet penetration rate in rural areas by promoting the construction of Internet infrastructure and reducing the costs of using the Internet. In addition, software companies can develop Internet services and applications with richer features to reflect the usage habits of individuals with low levels of digital literacy. Third, users should reduce their recreational dependence on mobile SNS and develop face-to-face interactions with other users of mobile SNS, thus increasing social trust levels and expanding social networks. Fourth, policymakers should be reminded to focus on the adverse outcomes of overusing mobile SNS, such as reduced productivity, increased work pressure, and induced personal and family conflicts (Gong et al. (2020)). Thus, the government should introduce policies to regulate the operation of mobile SNS. In addition, operators should provide alert services, such as an overuse reminder system in mobile SNS, which can help users pursue sustainable usage habits.

Conclusions

Our study improved the social capital theory by focusing on the roles of online social networks formulated by using mobile SNS and its shifts to offline social networks in the accumulation of social capital. Drawing on this new analytical framework, we examined the association between WeChat use and social trust and explored the mediating role of offline social networks. Based on a nationally representative Chinese sample from the CGSS, the results indicated that WeChat use had a positive effect on individuals’ social trust. However, those groups who can easily access digital technology and have high levels of digital skills, i.e., young adults, high-education adults, and urban residents, had more benefits from WeChat use. Moreover, the association between WeChat use and social trust was substantially mediated by offline social networks. These findings elucidated the association between mobile SNS use and social trust and highlighted the crucial role of digital technology in facilitating individuals’ social capital.

Data availability

The data is publicly available at http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Barber B (1983) The logic and limits of trust, Rutgers University Press, New Jersey

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51(6):1173–1182

Bian Y, Miao X (2019) Dual powers of virtual-real transformation in social networks. Chin J Socio 39(6):1–22. (in Chinese)

Blank G, Lutz C (2018) Benefits and harms from Internet use: a differentiated analysis of Great Britain. N Media Soc 20(2):618–640

Boneva, B, Quinn, A, Kraut, RE, Kiesler, SB, & Shklovski, I (2006) Teenage communication in the instant messaging era. In: Kraut R, Brynin M, Kiesler S (eds.) Human technology interaction series, computers, phones, and the Internet: domesticating information technology, Oxford University Press, New York, p 201-218

Bonfadelli H (2002) The Internet and knowledge gaps: a theoretical and empirical investigation. Eur J Commun 17(1):65–84

Bouchillon BC (2022) Social networking for interpersonal life: a competence-based approach to the rich get richer hypothesis. Soc Sci Comput Rev 40(2):309–327

Bourdieu P (1987) What makes a social class? On the theoretical and practical existence of groups. Berkeley J Socio 32:1–17

Brandtzæg PB (2012) Social networking sites: their users and social implications—A longitudinal study. J Comput-Mediat Comm 17(4):467–488

Bridges F, Appel L, Grossklags J (2012) Young adults’ online participation behaviors: an exploratory study of web 2.0 use for political engagement. Inform. Polity 17(2):163–176

China Internet Network Information Center. (2024) The 54th statistical report on Internet development in China. Available via https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2024/0829/c88-11065.html. Accessed 1 October 2024

Cruz-Jesus F, Oliveira T, Bacao F (2018) The global digital divide: evidence and drivers. J Glob Inf Manag 26(2):1–26

Datareportal (2022) Digital 2022: Global Overview Report. Available via https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report. Accessed 1 October 2024

Deng X, Yu M (2021) Scale of cities and social trust: evidence from China. Int Rev Econ Financ 76:215–228

Donath J (2007) Signals in social supernets. J Comput-Mediat Comm 13(1):231–251

Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C (2007) The benefits of Facebook “friends:” social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J Comput-Mediat Comm 12(4):1143–1168

Fisman R, Khanna T (1999) Is trust a historical residue? Information flows and trust levels. J Econ Behav Organ 38(1):79–92

Gan C (2018) Gratifications for using social media: a comparative analysis of Sina Weibo and WeChat in China. Inf Dev 34(2):139–147

Gong M, Yu L, Luqman A (2020) Understanding the formation mechanism of mobile social networking site addiction: evidence from WeChat users. Behav Inf Technol 39(11):1176–1191

Gong W, Li X, Zhang Y(2025) Unraveling the impact of social media involvement on public health participation in China: mediating roles of social support, social trust, and social responsibility. Hum Soc Sci Commun 12(1):1–12

Gui M, Argentin G (2011) Digital skills of internet natives: different forms of digital literacy in a random sample of northern Italian high school students. N Media Soc 13(6):963–980

Hale TM, Cotton SR, Drentea P et al. (2010) Rural-urban differences in general and health-related internet use. Am Behav Sci 53(9):1304–1325

Hampton KN, Wellman B (1999) Netville online and offline: observing and surveying a wired suburb. Am Behav Sci 43(3):475–492

Hogan B (2008). Analyzing social networks via the Internet. In: Fielding N, Lee R, Blank G (eds.) The handbook of online research methods, Sage, London, 141-162

Huang R, Gui Y (2009) The Internet and homeowners’ collective resistance: a qualitative comparative analysis. Socio Stud 24(5):29–56. (in Chinese)

Huhe N (2014) Understanding the multilevel foundation of social trust in rural China: evidence from the China General Social Survey. Soc Sci Quart 95(2):581–597

Johnston K, Tanner M, Lalla N et al. (2013) Social capital: the benefit of Facebook ‘friends’. Behav Inf Technol 32(1):24–36

Ju C, Tao W (2017) Relationship strength estimation based on Wechat friends circle. Neurocomputing 253:15–23

Jugert P, Eckstein K, Noack P et al. (2013) Offline and online civic engagement among adolescents and young adults from three ethnic groups. J Youth Adolesc 42:123–135

Kohler U, Karlson KB, Holm A (2011) Comparing coefficients of nested nonlinear probability models. Stata J 11(3):420–438

Kvasny L (2006) Cultural (re) production of digital inequality in a US community technology initiative. Inf Commun Soc 9(02):160–181

Leng C, Chen S, Zhu Z (2022) How does mobile payment affect rural residents ‘subjective well-being: evidence from Chinese General Social Survey. J Xi’an Jiaot. Univ (Soc Sci) 42(3):100–109. (in Chinese)

Leonard M (2004) Bonding and bridging social capital: reflections from Belfast. Sociol 38(5):927–944

Li B, Weng H (2022) Social capital accumulation on social network sites: a field experiment in WeChat groups. J World Econ 45(4):162–186. (in Chinese)

Li T, Huang C, He X et al. (2008) What affects people’s social trust? Evidence from Guangdong province. Econ Res J, (1):137-152. (in Chinese)

Li YJ, Pickles A, Savage M (2005) Social capital and social trust in Britain. Eur Socio Rev 21(2):109–123

Liang T (2020) Mechanisms of the impact of community smart service on residents’ well-being: empirical analysis based on the data of Survey of Resident Livelihood Security Needs in 2022. Urban Probl 10:72–81. (in Chinese)

Lin N (1999) Building a network theory of social capital. Connect 22(1):28–51

Lin N (2001) Social capital: a theory of social structure and action, Cambridge University Press, New York

Liu J, Zhang Y (2024) Entrepreneurship and mental well-being in China: the moderating roles of work autonomy and subjective socioeconomic status. Hum Soc. Sci Commun 11(1):1–10

Liu N, Zhong Q (2023) The impact of sports participation on individuals’ subjective well-being: the mediating role of class identity and health. Hum Soc. Sci Commun 10(1):1–9

Liu X, Keng S (2016) Internet surfing and political participation: a causal inference with instrumental variables. J Soc Dev 3(3):1–26. (in Chinese)

Luhmann N (1979) Trust and Power: Two works, John Wiley & Sons, New York

Lutz C(2019) Digital inequalities in the age of artificial intelligence and big data. Hum Behav Emerg Tech 1(2):141–148

Manago AM, Taylor T, Greenfield PM (2012) Me and my 400 friends: the anatomy of college students’ Facebook networks, their communication patterns, and well-Being. Dev Psychol 48(2):369–380

McDool E, Powell P, Roberts J et al. (2020) The internet and children’s psychological wellbeing. J Health Econ 69:102274

Muscanell NL, Guadagno RE (2012) Make new friends or keep the old: gender and personality differences in social networking use. Comput Hum Behav 28(1):107–112

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad Manag Rev 23(2):242–266

Pea R, Nass C, Meheula L et al. (2012) Media use, face-to-face communication, media multitasking, and social well-being among 8-to 12-year-old girls. Dev Psychol 48(2):327–336

Prensky M (2001) Digital Game-based Learning, McGraw-Hill, New York

Portes A (1998) Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Socio 24:1–24

Putnam RD, Nanetti RY, Leonardi R (1993) Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy, Princeton University Press, Princeton

Putnam RD (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community, Simon and Schuster, New York

Quan-Haase A, Wellman B (2004) How does the Internet affect social capital? In: Huysman M, Wulf V (eds) Social capital and information technology, MIT Press, Cambridge, p 113–131

Singh TB (2012) A social interactions perspective on trust and its determinants. J Trust Res 2(2):107–135

Sobel ME (1986) Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure models. Socio Methodol 16:159–186

Stern M, Adams A, Elsasser S (2009) How levels of Internet proficiency affect usefulness of access across rural, suburban, and urban communities. Socio Inq 79(4):391–417

Su Z, Ye Y, Wang P (2019) Social change and generalized anomie: why economic development has reduced social trust in China. Int Socio 34(1):58–82

Subrahmanyam K, Reich SM, Waechter N et al. (2008) Online and offline social networks: use of social networking sites by emerging adults. J Appl Dev Psychol 29(6):420–433

Temple J, Johnson PA (1998) Social capability and economic growth. Q J Econ 113(3):965–990

Tencent (2024) Tencent Announces Its Second Quarter and Interim Results for 2024. https://static.www.tencent.com/uploads/2024/08/14/424baf5fd758722f4d0c0c6362488b67.pdf. Accessed 1 October 2024

Uphoff N (1999) Understanding social capital: Learning from the analysis and experience of participation. In: Dasgupta P, Serageldin I (eds.) Social capital: A multifaceted perspective. The World Bank, Washington, D.C., p 145-249

Van Deursen AJ, Van Dijk JA (2014) The digital divide shifts to differences in usage. N. Media Soc 16(3):507–526

Van Deursen AJ, Helsper EJ (2015). The third-level digital divide: Who benefits most from being online? In: Communication and information technologies annual, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, p 29–52

Van Dijk JAGM (2005) The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society, Sage, London

Vannucci A, Simpson EG, Gagnon S et al. (2020) Social media use and risky behaviors in adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Adolesc 79:258–274

Wang JL, Jackson LA, Gaskin J et al. (2014) The effects of social networking site (SNS) use on college students’ friendship and well-being. Comput Hum Behav 37:229–236

Wang W, Zhou J (2019) Internet and social trust: micro evidences and impact mechanisms. Fin Trade Econ 40(10):111–125. (in Chinese)

Wang YD, Emurian HH (2005) An overview of online trust: concepts, elements, and implications. Comput Hum Behav 21(1):105–125

Wen Z, Geng X, Ye Y (2016) Does the use of WeChat lead to subjective well-being? The effect of use intensity and motivations. Cyberpsych Beh Soc N. 19(10):587–592

Wen C, Zhao X, Xu L et al. (2023) Military experience and household stock market participation: evidence from China. Int Rev Financ Anal 86:102519

Wellman B, Quan-Haase A, Witte J et al. (2001) Does the Internet increase, decrease, or supplement social capital? Social networks, participation, and community commitment. Am Behav Sci 45(3):436–455

Williams D (2006) On and off the’Net: scales for social capital in an online era. J Comput-Mediat Comm 11(2):593–628

Xu H, Zhang C, Huang Y (2023) Social trust, social capital, and subjective well-being of rural residents: micro-empirical evidence based on the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). Hum Soc. Sci Commun 10(1):1–13

Yang Y (2008) Categorization or guanxilization: the social psychology mechanism of the Chinese concept of “US”. Soc Sci China 4:148–159. (in Chinese)

Zhang Y, Liu J (2021) Internet use, social justice and doctor credibility: an empirical analysis of the 2013 China Social Survey. J Res 8:18–34. (in Chinese)

Zhang Y, Chen X, Shen Z (2023) Internet use, market transformation, and individual tolerance: evidence from China. Hum Soc. Sci Commun 10(1):1–12

Zhang C, Zhang Y, Wang Y (2024) A study on Internet use and subjective well-being among Chinese older adults: based on CGSS (2012-2018) five-wave mixed interface survey data. Front Public Health 11:1277789

Zhao X, Li J (2017) Contemporary youth’s Internet use and social trust. Youth Stud (1): 19-27. (in Chinese)

Zhao, Z, & Wang, J (2013). Weibo and WeChat: a comparative study based on media convergence. Editorial Friend, (12), 50-52. [in Chinese]

Zhao J, Zou Z, Chen J, Chen Y, Lin W, Pei X, Chen X (2024) Offline social capital, online social capital, and fertility intentions: evidence from China. Hum Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–13

Zheng X, Lee MK (2016) Excessive use of mobile social networking sites: negative consequences on individuals. Comput Hum Behav 65:65–76

Zhou J, Fu Y (2021) How does internet use affect the community integration of residents: analysis based on chinese urban residents’ living space survey. Sociol Rev China 9(5):105–121. [in Chinese]

Zillien N, Hargittai E (2009) Digital distinction: status‐specific types of internet usage. Soc Sci Q 90(2):274–291

Zou, Y, & Zhao, Y (2017). How do social networks affect trust? - Resource mechanism and exchange mechanism. Soc Sci Front, (5), 200-206. [in Chinese]

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Youth Program of the National Social Science Fund of China (Project No. 23CSH043).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiankun Liu conceived of the original idea, conducted all the formal analysis, acquired the funding, and wrote the original draft. Yueyun Zhang supervised Jiankun Liu and provided insightful feedback throughout the process. Both authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study does not contain any studies with human participants by any authors. Ethics approval was not required for this study.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Zhang, Y. The impact of mobile social network sites on social trust: evidence from the China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1041 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05408-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05408-4