Abstract

Entrepreneurial venture growth is viewed as crucial to economic growth and development and is aggressively promoted by governments, often accompanied by strong policies. Despite the availability of resources and assistance, many small businesses stay small and do not grow. Over many decades, entrepreneurship scholars have examined this phenomenon, acknowledging its peculiarity in many developing countries. However, there has been no detailed investigation into why this is so in developed economies. This study examines obstacles to SME growth in a study of 307 Small and Medium Enterprises in Australasia. The study finds that, among other factors that inhibit venture growth, the unwillingness of owners to grow is very significant, and these findings have implications for theory and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Growth continues to be a central focus in entrepreneurship research, as evidenced by the ongoing fascination with high-growth companies throughout the last few decades. Initial investigations established fundamental understandings (Delmar et al., 2003; Lee, 2014; Demir et al., 2017). However, the ongoing dialog has progressed, emphasizing sustainable expansion and systemic obstacles that hinder small and medium-sized enterprises (Cunningham et al., 2017; Hughes et al., 2012). Policymakers strive to create favorable conditions for their expansion in light of the considerable economic impact that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) make (Autio et al., 2018).

Although ample resources and support are available, numerous small enterprises in industrialized nations need to attain substantial growth. The investigation of obstacles impeding the expansion of entrepreneurial ventures has gained significant prominence. Krueger (2008) emphasized a portion of the need for more thorough research into these challenges. The intricacy of these obstacles, particularly within diverse economic environments like Australasia, needs to be better comprehended and lends itself to facile extrapolation from research conducted in other Western economies (Loane & Bell, 2006). This study explores the unique obstacles small and medium-sized businesses encounter in Australasia. Given this context, a crucial research question emerges: “To what extent do particular government policies in Australasia enable or impede the expansion of small and medium-sized enterprises, and what impact do institutional support and financial accessibility have on these results?”

SMEs are indispensable to economic development; their expansion is proportional to revenue growth and job creation. However, the journey towards progress is replete with a multitude of challenges. According to recent research, barriers such as regulatory frameworks, market access, and finance vary substantially across regions and economic statuses (Achtenhagen et al., 2020; Brown & Mawson, 2019). Romero-Jordán et al. (2020) discovered that, relative to larger firms, Spain’s tax policies stifle SMEs’ development potential disproportionately. Australasian contexts exhibit comparable obstacles to growth stemming from restricted aspirations and financial accessibility concerns, thereby underscoring the distinctive entrepreneurial challenges that characterize the area (Hughes et al., 2012).

Transitioning economies encounter distinct and unnecessary obstacles. Research has indicated that entrepreneurs in these contexts face challenges directly attributable to institutional and governmental structures. Fiscal policies, for instance, significantly hinder the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Albania (Krasniqi, 2007). According to a recent global assessment by Achtenhagen et al. (2020), small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face the most significant challenge in various economic environments.

This more comprehensive viewpoint is consistent with results from various economic scenarios in which obstacles to growth, such as capital, regulations, and market entry, consistently arise (Brown & Mawson, 2019; Coad & Tamvada, 2012). The recurrent themes observed in various studies emphasize the significant impact financial resources and institutional backing have on expanding small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This further supports the need for focused policy interventions (Beck & Demirguc-Kunt, 2006; Hughes et al., 2012). The expansion of SMEs is essential to the entrepreneurial ecosystem since it promotes job creation, innovation, and market diversity.

This study aims to analyze the impact of government interventions on the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Australasia. It examines various policies, institutional structures, and regulatory environments to understand their direct and indirect effects on SMEs. By addressing existing gaps in the literature, this research identifies both the obstacles and facilitators of SME growth within the region’s unique economic and regulatory context. The ultimate goal is to provide practical insights that can guide the development of effective policies and strong support systems for SMEs in Australasia. The paper’s structure comprises an introduction, a review of the literature, research methods, findings, and conclusions.

Background literature

Government policies promoting the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are not just crucial for national economies. They are also a beacon of hope. With their substantial contribution to creating jobs, innovation, and economic variety, SMEs hold immense potential. The current literature highlights the influence of several policy features, such as financial laws and innovation assistance, on the development of SMEs (Autio et al., 2018). A comprehensive understanding of these effects is crucial for formulating policies that efficiently bolster SMEs, and this understanding should inspire us all.

Expanding on this fundamental understanding, the lack of financial access arises as one of the foremost obstacles to the growth of SMEs. According to Beck and Demirguc-Kunt (2006), financial resources are a significant limitation for SMEs, impacting their capacity to grow, innovate, and even stay in business. Enabling policies, such as government-supported loans, tax benefits for investors, and simplified banking processes, can significantly improve the growth potential of SMEs. SMEs frequently encounter difficulties with bank financing, access to private capital, and reliance on public support. However, it is crucial to remember that rigorous fiscal measures such as elevated corporate taxes might negatively impact SMEs more than larger corporations because of their limited financial resources and more restricted cash flow (Romero-Jordán et al., 2020).

The shift from financial policies to regulatory frameworks can positively or negatively impact the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The intricate and onerous regulatory system can pose significant difficulties for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), as they usually have limited resources to allocate towards ensuring compliance compared to larger organizations. Achtenhagen et al. (2020) contend that rules should balance safeguarding consumers and businesses while providing the essential leeway for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to foster innovation and expansion. Implementing efficient administrative procedures and minimizing excessive bureaucracy can greatly alleviate the workload on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), enabling them to reallocate resources to more productive endeavors.

Innovation is vital for the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and it manifests in various forms, including both incremental and radical innovation. The impact of these innovation types on company growth can differ significantly based on the firm’s size and the industry in which it operates (Cunningham et al., 2017). To harness innovation effectively, it is essential to implement policies that encourage technological advancement and the adoption of new technologies. Autio et al. (2018) analyzed how leveraging digital and spatial opportunities can enhance entrepreneurial ecosystems, thereby supporting the growth of SMEs. Policies that provide financial backing for research and development, incentives for technology utilization, and support for collaborative efforts between academic institutions and businesses can significantly accelerate SME expansion by enhancing their innovative capabilities (Cunningham et al., 2017).

Government policies are vital for the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), particularly through measures that promote market expansion and internationalization. Trade agreements can reduce tariffs and barriers, giving SMEs access to new markets. Fiscal policies, including tax incentives, lessen financial burdens, enabling reinvestment in innovation. Innovation grants support product development, helping SMEs compete with larger firms. Additionally, streamlining regulations eliminates bureaucratic hurdles, fostering easier business growth. A favorable regulatory framework protects SMEs from unfair competition while encouraging fair practices. Overall, a combination of strategic policies can create a supportive environment for SMEs in both local and international markets. Loane and Bell (2006) emphasized the significance of networks and relationships in aiding the worldwide expansion of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). They proposed that policies promoting networking opportunities may help SMEs enter global markets more easily.

The impact of policy on SME growth is now evident, considering its diverse nature. Although the requirement for favorable financial and regulatory conditions is well-documented, the significance of innovation and market access should not be underestimated. Policymakers should consider the distinct difficulties and requirements of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) when formulating and executing policies. By cultivating a conducive climate that promotes convenient financial access, reduces regulatory obstacles, stimulates innovation, and allows market expansion, governments may greatly amplify the growth prospects of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Brown & Mawson, 2019).

An effective policy for promoting the growth of SMEs necessitates a comprehensive approach that tackles various obstacles simultaneously. Ongoing research and communication among policymakers, academic researchers, and SME stakeholders are not just crucial; they are the backbone of our work. This continuous interaction facilitates the improvement and adjustment of policies to more effectively address the changing requirements of the SME sector (Hughes et al., 2012).

Research method

This part of our study approach concentrated on gathering the viewpoints and experiences of SME owners in New Zealand and Australia concerning growth barriers, which is intentionally broad to facilitate thorough investigation using open-ended inquiries.

Utilizing open-ended questions enables us to thoroughly investigate the individual motives and perceived obstacles encountered by small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) owners, directly addressing the study issue. 307 small company owners participated in the study, contributing qualitative data that sheds light on the challenges, opportunities, and dynamics experienced by small enterprises in growth. A summary of the characteristics is presented in Table 1.

The participants were carefully chosen to encompass various industries and business sizes, guaranteeing that the results are strong and can be applied to the larger population of small and medium-sized enterprises in Australasia.

We used purposeful selection to select small business owners who could offer varied and pertinent insights for our research inquiries. This method guaranteed that we addressed various industries, company sizes, and backgrounds.

Participants were enlisted via professional networks, social media sites for small company groups, and New Zealand and Australian industry associations. We did an initial screening to confirm that participants were current small company owners actively engaged in their organization’s daily operations, meeting our criteria.

A questionnaire with open-ended questions was created to obtain thorough replies from participants. Because the open-ended questions had no predetermined answer options, participants were free to express their viewpoints, experiences, and perspectives. The questions were designed to explore participants’ perceptions of growth motivation and barriers. Questions such as ‘What factors could motivate you to grow your business into a large company?’ and What could you say is fueling your passion if you are passionate about turning your business into a large company?’ were custom-developed and tailored to the Australasian context.

The data collection was conducted online using Qualtrics to guarantee confidentiality and convenient access for New Zealand and Australian participants. Participants were briefed on the research’s objectives and the utilization of their data, and anonymity was guaranteed.

The open-ended questions were evaluated by thematic analysis, a method ideal for detecting, evaluating, and reporting patterns (themes) in qualitative data. This entailed a repetitive process of reviewing the answers, coding the data, and organizing codes into themes.

NVivo was utilized to organize and analyze themes emerging from the data. NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software, was utilized to streamline the organization and analysis of extensive qualitative data. This tool facilitated the effective management of data, classification of responses, and identification of emergent themes. Steps were implemented to guarantee the accuracy and consistency of the analysis. This involved peer debriefing meetings to discuss initial findings with research colleagues.

Participants were given comprehensive details regarding the study, including its objectives, the extent of their involvement, and the utilization of their data. Before completing the questionnaire, all participants provided informed consent. Stringent confidentiality protocols were put in place to safeguard the anonymity and answers of participants. The data were anonymized before analysis, and any potentially identifying information was either deleted or modified in the presentation of findings.

Data analysis

Our analysis underwent many changes within and between the data and the literature. This process started when we collected data (Charmaz, 2021). However, as time went on, we focused more and more on figuring out how policies meant to incentivize entrepreneurship eventually became a barrier.

Beginning our analysis with open coding

Initially, we utilized an open coding approach guided by modern qualitative research methodology (Saldaña, 2021). This allowed us to thoroughly examine our dataset and discover the terms, thoughts, and patterns expressed by the participants. This initial phase was centered on capturing the fundamental nature of the narratives conveyed during the interviews. Our methodology consisted of meticulously examining every transcript and identifying particular text passages with a “code” that condensed their fundamental significance. This approach, which aligns with the evolving nature of qualitative analysis described by Braun and Clarke (2021), consisted of several iterations of reviewing, coding, and recoding our data. We followed a recursive method to ensure that all concepts in the dataset were thoroughly covered (Nowell et al., 2017). During our initial coding project, we found unique concepts to comprehensively map the range of emergent ideas. These concepts encompass many themes, such as “resistance to growth” and “frequent shifts in government policies.” These first codes played a crucial role in our analytical framework, laying the foundation for deeper research. This repeated procedure refined our analysis and facilitated the identification of the fundamental themes that define our dataset.

Developing second-order theoretical themes

During our analysis, we carefully examined the concepts we discovered and looked for patterns and subtle differences beyond just language variances. This procedure, known as “axial coding,” allowed us to find overarching themes. This stage was crucial in our effort to group concepts into theoretical categories while preserving the participants’ original language—a crucial step in connecting the collected empirical data with the desired theoretical understanding (Flick, 2018). By engaging in a back-and-forth observation between our analytical observations and existing theoretical frameworks, we were able to identify and examine important obstacles that entrepreneurs encounter. These barriers may be categorized into three separate but interconnected levels: governmental, individual, and firm.

Entrepreneurs consistently emphasized the difficulties presented by government policies, which, instead of promoting expansion, frequently seemed like significant obstacles. Their concerns mainly focused on the unpredictable changes in regulatory and compliance requirements, which created an image of a volatile and unpredictable business environment. The prevailing agreement among business proprietors was evident: the dynamic character of governmental policies, particularly about regulation and compliance, greatly complicated the operational environment. Different interpretations of the scope and efficacy of government assistance, particularly in areas like financial support, further complicated this and worsened the external difficulties these businesses faced.

At the individual level, personal motives and circumstances influence business growth decisions. Many entrepreneurs expressed hesitance to seek growth due to their age and satisfaction with their current situation. This indicates a more profound concern about the uncertainties of business growth. Worries about how work-life balance could be affected were widespread, indicating a notable conflict between personal welfare and the need for company growth. The narrative then broadened to encompass the internal obstacles within the firms, especially as they grappled with the intricacies of expanding in size. Many founders, who were cautious about the potential changes that development could bring, strongly identified with the dread of losing control. Significant barriers to expansion were discovered, including the constraints of the local market, such as its limited size and high level of competition. These hurdles underscore the practical difficulties of scaling in a restricted setting.

This thorough analysis enabled us to seamlessly move from raw data to intricate theoretical conclusions by utilizing axial coding. Additionally, it thoroughly explored the complex nature of the obstacles to entrepreneurial growth. Through carefully analyzing and categorizing ideas into broader themes, we were able to portray the diverse and intricate nature of the entrepreneurial journey. The interaction between external policies, personal goals and limitations, and the internal workings of organizations shapes this journey. A thorough understanding of the political, individual, and organizational barriers illustrates the complex context in which enterprises’ growth routes are influenced and navigated.

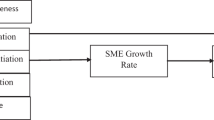

Aggregate dimensions and theoretical model formulation

In the last stage of our analysis, we condensed these secondary themes into overall dimensions, creating a theoretical model that demonstrates the dynamic connections between the emerging concepts and their link to wider theoretical frameworks (Gioia et al., 2013). This procedure involved the identification of event sequences and the systematic comparison of examples based on shared dimensions in order to clarify variations in trajectories. By repeatedly refining our emerging model and considering the theoretical framework, drawing on current scholarly debates (Eisenhardt et al., 2016), we developed many functional concepts that let us navigate back and forth between data and theory, strengthening our conceptual understanding. Figure one presents a simplified visual depiction of the analytical process, illustrating a clear and organized approach from raw data to theoretical abstractions. This representation showcases our methodological rigor and the development of our theoretical understanding.

Findings

The classification of findings into individual, institutional, and firm levels (see Fig. 1) thoroughly comprehends the complex nature of entrepreneurial expansion choices. Every phase of business growth presents unique problems and factors impacting how entrepreneurs expand their business. Efficient strategies to stimulate firm expansion should tackle issues at all three tiers, guaranteeing that individual incentives align with institutional backing and firm capacities. This comprehensive approach can enable the development of more sustainable business growth strategies adaptable to entrepreneurs’ demands and circumstances.

Individual level

At the individual level, the analysis focuses on personal characteristics and internal motivations that impact the decision-making processes of entrepreneurs.

Age

Older entrepreneurs frequently exhibit reduced enthusiasm for business growth, usually due to nearing retirement or shifting personal priorities. Their lifecycle stage influences their decision-making, which affects their risk tolerance and long-term planning. Examples of responses coded in this category were:

Because I am at retirement age, I am not looking to grow the business larger (PNZ111).

If I was 30 years younger (now nearly 60) (PNZ71).

When I would be younger (PAUS2).

Satisfaction with the current state

Many business owners are content with the existing scale of their business. The gratification arises from attaining a desirable condition of operations that individuals perceive as most suitable for their personal and professional objectives. Examples of responses under this category include:

Nothing I am happy as a sole trader (PAUS57).

None, prefer to keep it as is, it works well, so leave it alone (PAUS67).

NOTHING. I am financially successful. I don’t need a few extra zeros on net worth (i.e. I have enough already). Time for family and non-business activities is important (i.e. Business is priority, but it does not take second, third, fourth, etc. place as well) (PNZ33).

Dealing with uncertainty

Personal aversion to risk has a substantial effect. Entrepreneurs who perceive significant amounts of uncertainty and risk linked to growth are less inclined to pursue expansion, instead favoring the predictability of their current status. Responses illustrating this coding are as follows:

We are not prepared to take risks to grow the business (PNZ3).

Certainty over regional … futures. Current coalition seems hell-bent on reducing reliance on primary industry. It is the loss of primary industry growth that most affects regional economies. Uncertainty around this means businesses are less likely to take any risk that need matching growth to sustain them (PNZ108).

Capital without large risk (PNZ109).

Work-life balance

One important component is the wish to balance the demands of work and personal life. Growth is frequently viewed as a danger to this equilibrium, with possible increases in time commitment and responsibility being viewed as undesirable. Their comments included:

There are now no factors which could motivate me to grow my business into a “large company”. I do not have the time to do so, given my personal health, family health and caring commitments outside my business (PAUS13).

NOTHING. I am financially successful. I don’t need a few extra zeros on net worth (i.e. I have enough already). Time for family and non-business activities is important (i.e. Business is priority, but it does not take second, third, fourth, etc. place as well) (PNZ33).

Firm level

This level focuses on the business’s internal dynamics and strategic decisions that impact its ability and willingness to expand.

Fear of losing control

As firms expand, owners frequently fear relinquishing direct oversight of operations and decision-making. This concern can hinder them from pursuing growth opportunities. Examples of responses under this are:

None, prefer to keep it as is, it works well, so leave it alone (PAUS67).

Small is better. Can control if it is like this (PNZ21).

Difficulties of managing a growing business

Managing the growth of a firm may be challenging and overwhelming. Concerns encompass the difficulty of upholding standards, overseeing a larger workforce, and addressing heightened operational requirements. Examples of such responses are:

None. I don’t want to be a big business, too many headaches. Small is good and manageable (PNZ40).

Initially, I envisaged growing my professional services company to include several business partners and employees and started down that track. I found I spent most of my time on business development rather than delivering services to customers. I made a conscious decision to change direction. I now work on my own which gives me more flexibility, lifestyle balance and the chance to focus on solving problems for my clients (PNZ59).

Compromising product integrity

Business owners are worried that growth may compromise the quality of their products or services. Ensuring strict adherence to high standards is of utmost importance, and any potential danger to these standards can discourage the pursuit of expansion plans. Examples of responses under this category include:

Needing to be convinced the effort required would be beneficial and the integrity of product maintained (PNZ5).

The challenge of growing the business and providing a good service to customers (PNZ11).

Not now-I prefer a small company providing an excellent and niche service (PNZ37).

Size of the local market

The size of the local market can also impose limitations. In less populous or saturated markets, the firm’s strategic decisions about expansion may be influenced by the restricted growth options available. Responses illustrating this coding are as follows:

We are limited by the size of the NZ industry in this sector to grow much larger (PNZ4).

I have a niche business and have survived when others did not. Will stay at the level I am currently (PNZ78)

Institutional level

This level emphasizes the exogenous elements, such as policies and societal standards, that establish the structure in which enterprises function.

Government policies

Restrictive laws, taxation, and intricate regulatory systems are perceived as significant impediments to expansion. Entrepreneurs perceive these policies as burdensome and frequently contradictory to the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Responses illustrating this coding are as follows:

Reduced taxes, remove provisional tax (PNZ25).

If the government … nurtured businesses instead of seeing them as cash cows to be sucked dry. If … local endeavor was respected and favored over overseas sourced products and services … where industry was seen as beneficial to its citizens rather than a burden on the environment. If … favored quality over price (PNZ68).

Lack of support

The lack of perceived proactive assistance from governmental bodies and other establishments, including financial incentives and advisory services, impedes the expansion aspirations of entrepreneurs. Examples of responses under this theme are:

Well, to establish a large company is not possible without the government’s support. Present situation is very much negative in the market to survive, especially small business owners (PAUS4).

Not really. With the current government, I am about to either sell the business or close it down after 29 years (PNZ35).

Access to capital. Banks are very restrictive, and the alternatives are very expensive (PNZ115).

Compliance

The issues of compliance expenses and administrative burden in meeting regulatory standards are often mentioned. These issues require substantial resources and can shift focus away from primary company tasks. Some examples of responses placed in this theme were:

Less compliance, particularly in employment (PNZ15).

Less compliance and red tape (PNZ58).

Discussions and conclusions

The study offers significant insights into entrepreneurs’ obstacles to venture expansion. These observations are consistent with the concept by Hansen and Hamilton (2011), which recognizes the “controlled ambition of the owner-manager to grow” as a major obstacle to venture expansion. This tendency, marked by a purposeful restriction of aspirations for growth, is especially widespread in this area, indicating larger patterns in the entrepreneurial environment. The influence of an entrepreneur’s age on their aspirations for growth is a significant component of this deliberate ambition. As entrepreneurs near retirement age, their focus shifts from growing their enterprises to ensuring stability and effectively mitigating risk. The shift in emphasis with age results in a gradual decrease in risk tolerance, causing older business owners to become more cautious when taking on additional duties that could disturb their established equilibrium between their personal lives and business. The study conducted by Kautonen, Tornikoski, and Kibler (2011) supports this conclusion, indicating that older entrepreneurs prioritize the preservation of their lifestyle rather than pursuing the uncertain benefits of expanding their business. This demonstrates a distinct preference for stability over growth. Ultimately, the hesitancy of older entrepreneurs to pursue ambitious expansion plans can be seen as a logical reaction to the shifting personal and professional goals that come with being older. This observation emphasizes the importance of implementing governmental measures and business plans that acknowledge and tackle older entrepreneurs’ distinct difficulties and viewpoints. This will enable them to pursue growth opportunities that align with their risk preferences and life circumstances.

While the above allude to personal reasons, some of the factors identified are outside of the entrepreneur's control but worth noting as these impact their decision to grow or not. Of particular interest is the participants’ concerns over government policies that affect their profitability, and any policy or regulation that affects them will be perceived negatively. Issues such as compliance costs, taxes, health and safety, as well as policies on labor, are seen as burdensome. Operating in difficult environments, as perceived by these entrepreneurs, opportunities will not necessarily translate into growth because some would rather quit than continue. These findings are similar to other studies that have highlighted regulatory issues and a lack of government support as barriers to SMEs' growth (e.g., Gill & Biger, 2012; Gill & Mand, 2013; Lee, 2014; Lee & Cowling, 2015).

They are additionally apprehensive about the ambiguity resulting from government policies, such as alterations in tax laws, trade policies, and regulatory changes in specific industries. Government policies significantly impact the business climate, resulting in a landscape that presents both favorable prospects and difficulties for entrepreneurs. The volatility resulting from fluctuating government policies frequently triggers environmental changes, significantly impacting the financial and capital markets necessary for entrepreneurial expansion. The fluctuating nature of the environment leads to instability in the financial and capital markets, which in turn impacts the capacity of entrepreneurs to obtain funds for their desired expansion. Therefore, they must accept their resources as a substitute for finance. For instance, individuals within their network may be inclined to collaborate to generate value together by providing necessary resources and distributing the associated risk. The inherent unpredictability of this volatility leads to a lack of certainty, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) cannot rely on achieving improved performance through their planned expansion. When faced with failure, business owners should only take on risks within their financial means, ensuring they have the necessary resources to explore alternative ideas in the future. If individuals face failure, they should be adaptable to accept alternative approaches or concepts. Thus, entrepreneurs must utilize effectuation principles to stimulate growth in an ever-changing environment. They must prioritize being goal-oriented, emphasizing manageable losses, and displaying adaptability to overcome the specific risks and uncertainties they face. Illustrate policies and their impact on environmental dynamism.

Emphasized partnerships with stakeholders could help eliminate or reduce uncertainty. Solving sustainability problems in business is complicated because, often, business owners put profit before the planet, and any attempt to change the order is met with outright resistance. A partnership between policymakers and business owners can bring commitment from both sides toward achieving sustainable business practices. Partnering with entrepreneurs in sustainability brings a sense of responsibility, and policymakers can use this strategy to evoke commitment to their roles and responsibilities to society. This is important as most entrepreneurs pursue profit as their ultimate aim, neglecting society and the environment. Suppose they understand the merit of these regulations and policies. In that case, they will see them as manageable and be more than willing to comply and be sustainable in their business practices.

This study highlights barriers to SME growth at individual, organizational, and institutional levels. Key findings include the impact of policy volatility and entrepreneurs’ risk aversion. The study contributes to theory by elucidating the interplay between individual motivations and systemic constraints. Practical implications include the need for policies that address SMEs’ unique challenges, such as streamlined compliance processes. Future research should explore mixed-method approaches to provide deeper insights.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions regarding participant privacy. Still, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Achtenhagen L (2020) Entrepreneurial orientation-An overlooked theoretical concept for studying media firms. Nordic J Media Manag 1(1):7–21

Autio E, Nambisan S, Thomas LDW, Wright M (2018) Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg Entrepreneurship J 12(1):72–95

Beck T, Demirguc-Kunt A (2006) Small and medium-size enterprises: access to finance as a growth constraint. J Bank Financ 30(11):2931–2943

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) Thematic analysis: a practical guide. SAGE

Brown R, Mawson S (2019) Trigger points and high-growth firms: a conceptualization and review of public policy implications. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 26(1):158–179

Charmaz K (2021) The genesis, grounds, and growth of constructivist grounded theory. In: Developing grounded theory. Routledge. pp. 153–187

Coad A, Tamvada JP (2012) Firm growth and barriers to growth among small firms in India. Small Bus Econ 39:383–400

Cunningham JA, Menter M, Young C (2017) A review of qualitative case methods trends and themes used in technology transfer research. J Technol Transf 42:923–956

Delmar F, Davidsson P, Gartner WB (2003) Arriving at the high-growth firm. J Bus Venturing 18:189–216

Demir R, Wennberg K, McKelvie A (2017) The strategic management of high-growth firms: a review and theoretical conceptualization. Long Range Plan 50:431–456

Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME, Sonenshein S (2016) Grand challenges and inductive methods: Rigor without rigor mortis. Acad Manag J 59(4):1113–1123

Flick U (2018) An introduction to qualitative research (6th edn.). SAGE

Gill A, Biger N (2012) Barriers to small business growth in Canada. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 19:656–668

Gill A, Mand HS (2013) Barriers to the growth of small business firms in India. Int J Bus Glob 10:1–13

Gioia DA, Corley KG, Hamilton AL (2013) Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the gioia methodology. Organ Res Methods 16(1):15–31

Hansen B, Hamilton RT (2011) Factors distinguishing small firm growers and non-growers. Int Small Bus J 29:278–294

Hughes KD, Jennings JE, Brush C, Carter S, Welter F (2012) Extending women’s entrepreneurship research in new directions. Entrepreneurship theory Pract 36(3):429–442

Kautonen T, Tornikoski ET, Kibler E (2011) Entrepreneurial intentions in the third age: the impact of perceived age norms. Small Bus Econ 37:219–234

Krasniqi BA (2007) Barriers to entrepreneurship and SME growth in transition: the case of Kosova. J Dev Entrepreneurship 12:71–94

Krueger NF (2008) Entrepreneurial resilience: real & perceived barriers to implementing entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory Pract 36:1019–1051

Lee N (2014) What holds back high-growth firms? Evidence from UK SMEs. Small Bus Econ 43:183–195

Lee N, Cowling M (2015) Do rural firms perceive different problems? Geography, sorting, and barriers to growth in UK SMEs. Environ Plan C Gov Policy 33:25–42

Loane S, Bell J (2006) Rapid internationalisation among entrepreneurial firms in Australia, Canada, Ireland and New Zealand: An extension to the network approach. Int Mark Rev 23(5):467–485

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ (2017) Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods 16:1–13

Romero-Jordán D, Sanz-Labrador I, Sanz-Sanz JF (2020) Is the corporation tax a barrier to productivity growth? Small Bus Econ 55(1):23–38

Saldaña J (2021) The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was a collaborative effort among all authors, each making significant contributions to its conceptualization, methodology, analysis, and manuscript preparation. Abayomi K. Akinboye led the research project by conceptualizing the study, designing the methodology, conducting data collection and analysis, and writing the manuscript's initial draft. Sussie Celna Morrish was instrumental in developing methodologies, ensuring the rigor of qualitative analyses, and provided significant editorial input to enhance the manuscript’s clarity and coherence. Jamie D. Collins provided essential supervision and guidance throughout the research, offering theoretical insights, refining the study design, and contributing to the discussion and interpretation of the findings. All authors contributed to the intellectual development and approved the final manuscript, ensuring its academic integrity.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors confidently assert that they have no competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper. All authors unequivocally declare that this research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study, titled “Entrepreneurial Growth Intention: The Role of Cognitive Logic,” was positively approved by the Human Ethics Committee at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand (Ref: HEC 2017/60/LR-PS) on January 22, 2018. We ensured that all research procedures adhered to the relevant institutional guidelines and followed the principles outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. This approval facilitated the recruitment of participants, the administration of surveys, and the thorough analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data related to entrepreneurial growth intentions, contributing valuable insights to the field.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained in writing before data collection began. Participants received details on research objectives, procedures, and their rights, including voluntary participation, withdrawal without penalty, assurance of anonymity and confidentiality, and consent for the use of anonymized findings. New Zealand participants:In New Zealand, potential participants were identified through the NZBWW, which publishes the New Zealand Business Who's Who database. On August 1, 2018, an email invitation was sent to 7475 individuals, with 4617 successfully delivered and 365 affirmatively responding. Each participant received a soft copy of the questionnaire via Qualtrics, which included a consent form detailing the study's purpose, the voluntary nature of participation, the use of data, and the confidentiality of personal information. Australian participants: In Australia, participants were recruited from Survey Sampling International's business database. On August 20, 2018, 4536 individuals were invited, resulting in 406 starting the study and 311 completing the survey within two weeks. SSI provided written information about the study and required digital informed consent, ensuring participants understood the research's nature, voluntary participation, and confidentiality assurances. In both countries, the consent process covered the following: (1) Agreement to participate in a non-interventional research study involving a structured online questionnaire. (2) Consent to the confidential use of their anonymized responses for research publication and dissemination. (3) Confirmation that all responses would be treated with strict confidentiality, stored securely, and only accessible to the research team. (4) Assurance that no identifying personal or organizational information would be published or shared. (5)Clarification that there were no foreseeable risks associated with participation and that the survey could be discontinued at any point. As no vulnerable populations or minors were involved in the study, additional protections specific to those groups were not required. The consent protocol adhered to the ethical standards for social science research, ensuring that participants were fully informed of their rights, the purpose of the research, and the use of their data before consenting to participate.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akinboye, A.K., Morrish, S.C. & Collins, J.D. Policy pathways and barriers: examining the effects on SME growth in Australasia. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1379 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05422-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05422-6