Abstract

This paper proposes an analytical framework to deconstruct the complexity of policy governance in globalization. Challenging traditional models’ static assumptions and linear diffusion narratives, it advances a dynamic perspective rooted in Deleuze’s rhizomatic theory and topological principles, conceptualizing policy formation as contingent intersections and topological emergence among cross-local knowledge nodes. Three analytical innovations transcend “global-local” binaries: (1) Rhizomatic evolution replaces linear transfer, emphasizing nonlinear knowledge connectivity and epistemic mutations across nodes; (2) Spatiotemporal folding reveals policy innovation emerge in the overlap of “near and far” policy references and historical sedimentation and future projections; (3) Topological power analysis uncovers entangled explicit/implicit power structures in global policy governance networks. By tracing policies’ processual emergence and the spatiotemporal dynamics behind it, the study clarifies the “geography of power relations” behind global knowledge production while offering a tool for navigating “global flows”—“local practices” dialectics. This broadens the analytical scope of policy mobility research and offers a alternative perspective for tackling policy governance challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of policy mobility research represents a significant development in human geography’s response to the complexities of governance in the globalized era. This field focuses on deconstructing the “deterritorialized” nature of policy phenomena, examining how policy initiatives transcend geographical boundaries and dynamically reconfigure within trans-scalar networks (McCann and Ward, 2012). The theoretical foundations of this research stem from a paradigm crisis in traditional policy diffusion models, which treat space as a static vessel for policy transplantation (Peck, 2011). By relying on linear transmission narratives, these studies attribute policy convergence to geographic proximity or institutional imitation (Baker et al., 2020). Such spatial instrumentalism obscures the topological complexity of policy flows and reduces uneven geographical development to a simplistic notion of “knowledge transfer failure” (Amin, 2002). As McCann (2011) astutely notes, the diffusion metaphor embodies a progressivist historical perspective, constructing an ideological myth of the “civilizational gradient” that positions policy innovation hubs (like Nordic welfare states) as beacons of rationality while relegating peripheral regions to the role of passive recipients.

A significant theoretical advancement in geographic policy mobility research is the reconstruction of the ontological status of policy as a “mobile event” (Peck and Theodore, 2012). By tracing the “translation-mutation” processes of policy components across transregional networks (Cohen, 2015), research demonstrates that policy innovation is not a mere technocratic transplant but a topological emergence resulting from the intersection of diverse knowledge at critical nodes (Prince, 2016). For instance, London’s carbon neutrality plan is not simply a replication of Nordic models nor a linear extension of local practices; instead, it is shaped by the interweaving of transregional nodes, including New York’s climate finance network and Berlin’s energy transition communities, creating a governance paradigm that engages multiple temporal and spatial scales (Tozer and Klenk, 2018). This dynamic construction mechanism challenges the binary opposition of “local adaptation/global template,” revealing the latent power geometries within policy mobility networks, where certain nodes become “hubs” of policy topology due to privileged knowledge production, while others are relegated to passive “terminals” (Allen, 2011).

Nevertheless, existing literature often falls into a dualistic trap: policy mobility is either oversimplified as a linear interaction between “global norms and local practices” or framed as an antagonistic narrative of “local resistance versus external penetration” (McCann and Ward, 2015). When policy mobility is viewed as a process of “local adoption of external solutions,” it overlooked the ontological complexity inherent in policy innovation—where policy is viewed not as a static object of transplantation but as a “processual entity” that is continuously reconfigured in motion (Robinson, 2015).

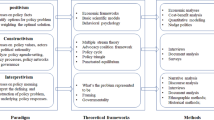

To address these issues, this study proposes leveraging Deleuzian rhizomatic thinking to overcome current limitations. This theoretical framework conceptualizes policy networks as non-hierarchical topological structures, positing that policy innovation arises not from a rational design of an “originating node” but from the accidental connections of dispersed knowledge fragments, resulting in rhizomatic growth (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987). This paradigmatic shift necessitates a three-dimensional transformation in research approaches: first, moving from linear trajectories of policy displacement to decoding the rhizomatic evolution of policy generation, emphasizing the non-linear characteristics and contingent logics of innovation emergence; second, breaking away from static spatial analysis frameworks to construct a “temporal-spatial folding” analytical paradigm that compresses temporal layers, overlays heterogeneous spaces, and recalibrates knowledge-power relations to elucidate the complex dynamics of policy “innovative emergence”; third, transcending the metaphor of geographical containers to establish a topological power analysis framework, which systematically deconstructs both explicit power constraints and implicit penetrations within global governance networks, thereby revealing the triadic interconstitution of power, knowledge, and space in global governance.

By integrating rhizomatic thought with topological theory, this study systematically deconstructs the nonlinear generative mechanisms of policy mobility and its global spatial attributes, achieving three significant theoretical breakthroughs in traditional policy research paradigms: first, breaking free from the cognitive limitations of the “global-local” binary opposition; second, transcending the constraints of static textual analysis by constructing a “process ontology” framework that clarifies the open and uncertain nature of policy evolution; third, deconstructing the metaphor of geographical containers to establish a topological power analysis paradigm that elucidates.

From policy transfer to policy mobility

Policy transfer research emerged in the mid-20th century, rooted in comparative political science’s quest to map how policies diffuse across jurisdictions (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996). Early studies, such as Seth Rogers’ (1962) work on diffusion, focused on temporal and spatial patterns—how policies spread over time, influenced by geographical proximity and institutional mimicry (Shipan and Volden, 2012). These frameworks, while useful for identifying broad trends, reduced policymaking to a technical exercise, treating policies as static commodities exchanged through rational actor networks. Dolowitz and Marsh’s (2000) seminal policy transfer model expanded this scope, probing the “who, what, and why” of cross-jurisdictional borrowing. Yet even this advancement retained a normative-rationalist bias, framing success or failure in terms of fidelity to an original model (Stone, 2012).

As prioritizing institutional convergence and “best practice” replication, policy transfer studies neglect the socio-political processes that transform policies as they travel. For instance, Knill’s (2005) analysis of policy convergence assumes a mechanistic alignment of objectives and tools across contexts, sidelining how local actors reinterpret, resist, or subvert imported models. Similarly, Bennett and Colin’s (1991) convergence dimensions—objectives, content, outcomes—fail to account for the mutations that arise when policies encounter divergent cultural, historical, or material conditions. These omissions reflect a deeper epistemological flaw: the treatment of policies as apolitical, pre-packaged solutions rather than socially constructed products whose content and form are mutable as they move (Peck and Theodore, 2001; McCann and Ward, 2011).

Policy as a product of social construction

As Peck (2011) critiques, such approaches perpetuate a “rational-formalist” tradition that obscures the messy realities of policymaking, including the power struggles, ideological contests, and improvisations that characterize policy journeys. Policies or best practices are neither spontaneous nor neutral imitations; rather, they are deliberate constructs forged through power-laden social interactions (Temenos and McCann, 2013). Subsequent case studies explore how policy reconfiguration is influenced by the complex interactions among formal institutional actors (e.g., local governments and international organizations) (Brenner et al., 2010), informal policy consultants (Borén and Young, 2021), and dynamic grassroots networks (Temenos and Baker, 2015). These interactions are shaped by their unpredictable behavioral patterns, discursive practices, and transient emotional dimensions (Ward, 2006; McKenzie, 2017). This body of work frames urban policies, models, and knowledge as dynamic social constructs that are continually shaped through iterative processes of innovation, promotion, and contestation (Peck and Theodore, 2001; Dussauge-Laguna, 2012).

This shift from a linear, rationalist perspective to a dynamic, relational one reflects a growing realization that policies are far from static; rather, they are artifacts shaped by the interplay of power dynamics, situational contexts, and unforeseen contingencies. These policies are constantly in flux, shaped by socio-material practices and power relations as they traverse different scales and places. By focusing on the competing interests and cross-contextual negotiations among actors from different places and scales, the mobilities framework dispels the notion of technical neutrality, exposing policymaking as a contested domain of power and creativity. Within this framework, policy models or “best practices” exhibit emergent properties and hold the potential for mutations (Peck and Theodore, 2001).

Policy mutations/variations in flow: when and how they occur

Scholarly debates on policy variation revolve around competing understandings of agency, power, and epistemic hierarchies in policy mobility. A key axis of divergence lies in scholars’ interpretations of how and why policies mutate across space and time. Jamie Peck and institutional path dependence theorists emphasize the mediating role of pre-existing socio-historical conditions in shaping policy localization. They argue that global models like neoliberalism rarely diffuse uniformly but undergo cyclical processes of decontextualization (stripping policies from their original contexts) and recontextualization (reconfiguring them to align with local political-economic specificities) (Peck, 2011; Brenner et al., 2010). This dynamic explains why structural adjustment programs in the Global South seldom replicate Euro-American prototypes; instead, they are recalibrated through local power struggles, colonial legacies, and resource disparities, manifesting as hybridized policy forms (Wood, 2016). Such findings challenge universalizing narratives by foregrounding how global models become entangled with place-specific institutional matrices and cultural practices.

In response to the institutionalist focus on path dependence, Temenos and McCann (2013) advocate a temporally expansive analytical framework that examines policy mutation across entire policy lifecycles. They critique narrow implementation-centric approaches, arguing that power dynamics and discursive contests—not merely bureaucratic adoption—fundamentally shape policy formation and adaptation. To unpack these processes, scholars have developed ethnographic methodologies that trace the embodied, performative, and material dimensions of policymaking. For instance, Andersson and Cook’s (2019) concept of “global-micro space” highlights informal encounter spaces—such as study tours, conferences, and multimedia platforms—as critical sites where policies gain new meanings through transnational interactions. Similarly, Ward (2006), Roy and Ong (2011) emphasize how cross-local social practices like comparison, imitation, and translation enable actors to selectively adapt global models to local governance challenges. These theoretical innovations reveal policy mobility as a contested process rather than a linear transfer, where actors negotiate the tension between external templates and endogenous socio-political realities (Temenos and McCann, 2013).

By integrating these perspectives, contemporary research challenges monolithic portrayals of neoliberalism and other “global” models as top-down impositions. Instead, it foregrounds the agency of local policymakers who strategically appropriate, resist, or subvert imported policies to address context-specific needs (Robinson, 2015). This paradigm shift—from structural determinism to relational understandings of policy mobilities—provides a multidimensional lens for analyzing how ideas, practices, and governance logics circulate, adapt, and stabilize across the space.

The topological turn in policy mobility research: beyond the global-local dichotomy

The relational perspective is designed to rectify the oversimplified understanding of global-local relations prevalent in prior mobility studies. It emphasizes the dynamic intertwining of the two, positing that mobility policies are global relational outcomes generated through the interaction of multiple local actors. However, these studies face methodological criticism for creating false divides like “global/local,” “here/there,” and “mobile/fixed” (McCann and Ward, 2015). For example, political economy research on mobile policy’s “embedding, disembedding, translation, and variation” dichotomizes global policy circulation and local policy formulation into two independent (McCann and Ward, 2015). This makes it difficult to fully capture the complexity of policy mobility (Prince, 2016). Similarly, postcolonial scholars, while advocating a decentralized perspective for examining how localities selectively adopt and reshape mobile policies sourced from diverse origins (Robinson, 2015). It often inadvertently succumb to the binary trap of conceptualizing policy movement as simply “from here to there” (Prince, 2016; Lane, 2022).

The above studies aim to examine local policy-making within the context of global policy circulation, aiming to investigate the “territoriality and relationality” of policy flow (Ward, 2012). However, they encounter a methodological quagmire. When researchers concentrate on the movement-variation trajectories of mobiling policies, they tend to gravitate toward one of two polarized perspectives: either emphasizing the territorial priority of localized practices, or prioritizing the relational dominance of transnational network connections (Peck and Theodore, 2001; Bulkeley, 2006). This binary choice undermines the spatial tension inherent in policy mobility (McCann, 2011). As Allen and Cochrane (2010) argue, policy making is not an isolated outcome but rather a process of “rendering near” the relationship between the local and the external through continuous interaction with external knowledge, resources, and practices.

Prince (2016) adopts a topological perspective to critically reexamine the traditional global-local binary framework. He posits that prior research has failed to adequately consider policy as an assemblage of both local and extra-local elements, along with the cognitive presumption of policy-making being confined within a geographical container. These studies tend to oversimplify each policy unit, reducing it to a “policy territory” characterized by distinct boundaries and spatial isolation from other units (Savage, 2020; Clarke, 2012; Peck and Theodore, 2001). This Cartesian conception of space misrepresents the inherent characteristics of policy governance fields. Far from being static geographical containers, these fields are, in fact, dynamic aggregates that are continuously co-constructed by multi-scale elements and diverse actors through intricate spatial practices (Jacobs, 2012). Prince’s (2016) theoretical breakthrough lies in the reflection on the spatial dimension of policy mobility. The “spatiality” of policy mobility should be understood as a topological projection of the dynamic evolution of relational networks (Lewis et al., 2016; Allen and Cochrane, 2010), rather than a mechanical mapping of physical space. This shift reveals that policy mobility is not merely the simple diffusion of policy elements across geographical space, but a continuous process deeply embedded in complex networked relations (Allen, 2011; Jacobs, 2012).

To break through the linear paradigm of mobility research, Searle and Darchen (2023) draw upon Deleuze’s concept of “rhizomatic” generation of new practices (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987; Rowe, 2009). The rhizome, as a network form with lattice-like properties but distinct from a tree-like hierarchical structure, offers a novel theoretical framework for understanding the development of local policies (Mocca, 2018). Unlike the traditional model, in which knowledge originates from a single source, rhizomatic information flow meanders more haphazardly across a network (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987).

The rhizomatic perspective, as applied to policy development, highlights the interconnected and dynamic nature of financial policies, which are influenced by a multitude of factors and stakeholders. The emergence of policies in one location may be directly tied to those in another, or they may be indirectly interconnected through intricate, multi-faceted relationships (Rowe, 2009; Searle and Darchen, 2023). The former refers to mobile policies that retain their core content while adapting to new environments, whereas the latter pertains to “new” policies that are generated on entirely novel conceptual foundations, exhibiting weaker ties to traditional policies (Mocca, 2018). The rhizomatic perspective imbues the generation of local policies with openness and generativity (McFarlane, 2011): policy innovation arises not only from the utilization of existing knowledge but also from fresh connections and innovations that emerge within translocal networks (Searle and Darchen, 2023). It inspires to focus on how policies “grow” based on emerging networks—Deleuze and Guattari’s (1987) so called rhizomatic emergence—rather than just “moving” from one location to another.

Adopting the Deleuzian notion of rhizome (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987; Rowe, 2009) augments our comprehension of policy adoption. It provides a framework for examining the genesis of new policies and their relationships with existing policies, practices, and knowledge. Policy formation can be viewed as a creative endeavor, rooted in local circumstances while judiciously incorporating knowledge from diverse global sources (Robinson, 2015; Savage, 2020). This suggests that all policies are co-created through dynamic interactions between local contexts and global knowledge (Collier and Ong, 2015; McCann and Ward, 2011). Therefore, rather than tracking policy “movements” across spaces, it is more important to understand how policies are “arrived at” (Robinson, 2015). By observing the process of policy “taking shape” and its interactions with local and external actors, knowledge, and other elements (McFarlane, 2011; Searle and Darchen, 2023), we can see how policy localization “renders near” the relationship between the external and the local through ongoing interactions with global knowledge, resources, and practices (Allen and Cochrane, 2010; Allen, 2011). Such an approach not only deepens our comprehension of policy generation, evolution, and impact within dynamic spatial networks but also helps capture the global relationality and spatiality inherent in policy formation.

Processuality and spatio-temporality of policy generation/evolution: a rhizomatic reinterpretation

The process-ontological turn in policy studies

Rhizomatic thinking offers crucial insights into the formation of local policies in the context of globalization. It acknowledges the need for policymakers to actively absorb external knowledge elements while emphasizing that the essence of innovation lies in the creative transformation of local practices. Its theoretical breakthrough resides in dismantling the traditional binary framework of “movement-reception” and “global-local” prevalent in mobility studies, adopting instead a dynamic, networked, and presents a generative perspective on policy formation. As Searle and Darchen (2023) metaphorically illustrates, policy innovation resembles the growth process of plant roots in soil: while maintaining the stability of core genes, it achieves self-renewal through continuous material exchange with the external heterogeneous environment. From this perspective, local policies are continually undergoing a cycle of deterritorialization and reterritorialization, evolving in a manner akin to ‘living organisms’ within the tension between openness and autonomy (see also Savage, 2020; McFarlane, 2011).

This necessitates the establishment of a ‘process ontology’ framework within mobility studies, involving the conceptualization of policies as progressively developing ‘organic systems’. Embracing such an approach necessitates moving beyond static textual analysis to meticulously examine the dynamic mechanisms at play within local contexts (Robinson, 2015; Temenos and McCann, 2013), alongside their evolving interconnections with external systems (Prince, 2016; Roy and Ong, 2011). For instance, South Arican’s BRT plan is not merely a straightforward replication of Nordic experiences. Instead, it represents a novel governance paradigm forged through localized experimentation (Wood, 2015). The localized policy experimentation has sometimes been crafted through continuous engagements with esteemed networks (Fricke, 2022; Pow, 2014). The open-ended characteristics of this “growing policy” intricately embed each stage of its development firmly within the politico-economic networks of specific spatiotemporal contexts (Fricke, 2022). It achieves evolution through ceaseless interactions with both internal and external elements (Robinson, 2015). From this point, the very essence of policy need to be redefined. Policy is not only a product resulting from the interplay between local contexts and global knowledge but also a “processual existence” that is continuously restructured via spatial practices.

Policy evolution through a process-ontological lens

In fact, policies are far from being ultimate “perfect solutions.” Instead, they are dynamic entities that are continuously evolving through processes such as interpretation, enactment, reform, and even termination (McFarlane, 2011; Savage, 2020). Right from their inception, they are deeply embedded in a complex network of fields characterized by multiple disruptions, interpretive tensions, and institutional contestations. For instance, legal norms and industry standards often find themselves in a state of coexistence and restructuring. During the formation of policies, they continuously absorb and assemble external knowledge. Their innovation and evolution display dual characteristics of predictability and uncertainty (Savage, 2020). Policies, despite their broad applicability in form and effect, are inherently products of their unique spatiotemporal contexts and are subject to ongoing adaptive evolution to meet the demands of changing environments (Wood, 2015; Lewis et al., 2016).

This does not negate the objective reality of policies; rather, it emphasizes their dynamic character as ‘processual entities.’ As Deleuze and Guattari’s (1994) philosophically insight, the key lies not in the static state of “what we are” but in the generative process of “what we are becoming.” Policies are not merely practices constituted within space; they are also the results of the unfolding of time (Hartong and Ubras, 2023; Kivimaan and Rogger, 2020). This epistemological advance calls for a shift in policy studies, namely from static textual analysis to the study of dynamic, generative, and evolutionary processes (Searle and Darchen, 2023; Fricke, 2022). In particular, it is necessary to focus on how local policies evolve in the context of the convergence of global mobile knowledge to local areas and on how innovation continuously emerges in the processes.

Reflecting on the essence of policy processes uncovers three pivotal understandings regarding “how policies come into being” (Robinson, 2015). First, knowledge is not bound by hierarchical “center-periphery” models, but instead flows effortlessly, akin to a liquid within a rhizomatic network (Savage, 2020; Searle and Darchen, 2023). Second, policy innovation transcends mere replication or “localized adaptation” of established knowledge. Instead, it emerges through new connections between translocal network nodes (Guggenheim and Söderström, 2010; Pow, 2014). It evolves gradually through mutual exchanges and inspirations among diverse locations and entities. Finally, policy formation exhibits a unique translocal characteristic. It is rooted in local contexts while continuously interacting with the global knowledge systems via a rhizomatic network (Prince, 2016; Searle and Darchen, 2023). This process encompasses the “folding” policy ideas and practical experiences, which are spatially scattered and temporally discontinuous, into local settings—a phenomenon known as spatiotemporal folding (Allen, 2011; Lewis et al., 2016). Within the context, adaptive modifications and creative reconfigurations of knowledge give rise to context-sensitive innovations (Fricke, 2022).

Rhizomatic evolution, spatio-teporal folding and power topology: an alternative framework

Building on process ontology, future research on policy mobility should address three core dimensions: first, analyze the rhizomatic evolution of policy, highlighting its non-linear and contingent innovation processes which resist being simplified to mere local adaptations of global models; second, adopt the “spatiotemporal folding” framework to explore how policies are reassembled and reorganized across space and time, revealing the dynamic mechanisms underlying the emergence of innovation; third, move beyond the confines of geographic containers to decode the power structures embedded in trans-spatiotemporal networks, revealing how power geometries shape policy mobility and its contextual outcomes.

The rhizomatic evolution of policies

Deleuze’s Rhizome Theory radically challenges the traditional framework in policy research, highlighting the non-hierarchical, diverse, and ever-evolving nature of policy development (Searle and Darchen, 2023; Savage, 2020). The concept of “nomadic connectivity” (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987) within rhizomatic networks illustrates that policy innovation does not stem from a centralized, rational blueprint but rather from the chance encounters and structural transformations of varied components within interconnected networks (Savage, 2020; Müller and Schurr, 2016). This theoretical shift urges us to move beyond rigid structuralist paradigms, conceptualizing policy instead as a ‘dynamic emergence’ occurring at key junctures within these networks (see also McFarlane, 2011). Such polices are not predetermined institutional artifacts but adaptive evolutionary systems, perpetually shaped through the interplay of local knowledge and extra-local flows.

It can be argued that policy is neither static nor monolithic, but rather, a dynamic interplay among diverse elements, continually undergoing a crucial process of reconstruction (McFarlane, 2011). As external knowledge increasingly converges at the local level, it necessitates interpretation and adaptation into a localized context (Enseñado, 2024; Stone, 2012; Hartong and Ubras, 2023). Throughout this process, various stakeholders facilitate the innovative fusion of diverse knowledge in the pursuit of understanding development reality of specific places, identifying governance issues and shaping shared visions (Savage, 2020; Cook and Ward, 2011). Ultimately, this results in the creation of innovative policy paradigms that exhibit unique local characteristics. This corroborates the argument of “the impurity of local knowledge” put forward by Hartong (2018) and also backs up Fricke’s (2022) claim that “knowledge production is essentially contextual practice.” Even widely disseminated knowledge systems are invariably rooted in local cultural semantic networks (Fricke, 2022).

This study proposes two critical research foci to decode the rhizomatic evolution and innovative emergence of local policies. First, by examining the dynamics of policy learning and knowledge translation among various stakeholders, we must assess how the mediation of foreign knowledge influences—and potentially disrupts—the development paths of local policy systems. Second, by dissecting the assembly mechanisms of policy components and their induced knowledge hybridization phenomena (McFarlane, 2011; Fricke, 2022), we aim to decode how tensions between competing knowledge paradigms generate transformative impulses, ultimately leading to innovations that transcend traditional linear policy iteration. This dual approach reveals how localized policy creation represents not mere adaptation but constitutive acts of transgressive innovation.

This process-oriented approach overcomes the spatial displacement paradigm of traditional mobility studies through its focus on the generative mechanisms of “policy ecologies” (Searle and Darchen, 2023; Deleuze and Guattari, 1987). It reveals how heterogeneous policy elements emerge through interactions within spatiotemporal networks (Müller and Schurr, 2016), undergo continuous reconfiguration, and achieve iterative refinement, ultimately leading to the creation of innovative and contextually appropriate policy forms. This, in turn, enables us to reinterpret local practices as active replicas of a dominant policy model, but as dynamic adaptations shaped by interconnected global-local dynamics.

The dynamics of spatiotemporal folding

Rhizomatic thinking has challenged the container metaphor of policy formation, highlighting the dynamic interconnections between policy fields (e.g., cities) and the external world. As Massey (1991) stated, locality, fundamentally, serves as a nodal point for the heterogeneous convergence of transregional elements, with its intrinsic attributes perpetually reshaped by fluid relational networks. In this sense, policy territories should not be reduced to isolated nodes within static networks but conceptualized as “networks of nodes”—heterogeneous networks woven by multiple relational flows (Allen, 2011; Pow, 2014). This insight resonates with McCann’s (2011) assertion that policy territories such as cities are open systems continuously restructured by translocal ties.

Viewing policy fields as a “network of nodes” eliminates the possibility of a binary opposition between local policy and external knowledge. Policy formation is a dynamic and iterative assemblage process, encompassing the nonlinear aggregation of both proximal and distal, historical and present policy elements, such as expert knowledge, regulatory systems, and technical standards, into policy fields or nodes (Savage, 2020). This process is akin to the structured approach outlined in policy development literature, which includes stages like problem identification, agenda setting, policy planning, and policy legitimation, each involving a range of actors and factors. The convergence of knowledge, which is spatially non-contiguous and temporally discontinuous, towards the nodes, can be designated as “spatiotemporal folding” (Fricke, 2022; Prince, 2016; Hartong and Ubras, 2023).

Amin’s (2002) topological framework posits that institutional logics, governance ideologies, and cultural norms drive “folding” by creating virtual connections amidst fragmented policy environments. Technocratic tools (e.g., rankings, benchmarking) linking dispersed territories into a trans-territorial framework of reference (Roy and Ong, 2011; Prince, 2016), while temporal grafting of colonial, authoritarian, or welfare legacies (Kivimaa and Rogge, 2020) collapses heterogeneous histories into hybrid policy narratives. These processes reconfigure spatiotemporal hierarchies by merging the dichotomies of past-present-future and local-global into a unified governance plane. Through repetitive comparison, such folding generates both continuity and rupture, producing decentralized, elastic policy networks (Hartong and Ubras, 2023).

The “folding imagination” reconfigures global governance connectivity by collapsing linear spatiotemporal hierarchies, creating a topological space that functions as a crucial arena for policy governance (Prince, 2016; Lewis et al., 2016). This leads to three crucial questions: First, how relational proximity, fueled by explicit power entities such as the WTO and implicit intermediaries like algorithmic standards, diminishes geographic constraints in policy learning and molds the topological policy space. Second, how discrete knowledge and experiences are systematically aligned through metricization, narrativization, and case-making, and what value screening and contextual adaptation they undergo in the process (McKenzie, 2017; Wood, 2015). Third, how actors forge decentralized, dynamic policy networks via cross-spatiotemporal interactions, transcending territorial constraints to shape a globally topological space.

Exploring the above questions helps to interpret the spatiotemporal folding dynamics of policy evolution and reveal the “folded” imaginary (topological) space that coexists in physical geography (Clarke, 2012; Prince, 2016). The study highlights the spatiality of policy evolution, emphasizing how policies adapt to new social environments, economic conditions, and the needs of the people, as seen in the spatial shifts and adaptations of policies over time (Kivimaan and Rogger, 2020; Wood, 2015), advancing our understanding of policy innovation as neither a local mutation of global paradigm nor a random combination of chance events. Instead, it emerges from a temporospatial nexus where local agency dynamically interacts with global forces and historical legacies converge with contemporary configurations,

Power structure of policy topological space

Rhizome thinking offers a paradigm that surpasses the dualistic “locality-globality” analytical framework. It draws parallels between policy areas, such as cities, and key nodes within rhizome networks; these nodes are embedded within local contexts while simultaneously being interconnected with global knowledge systems (Allen, 2011; Amin, 2002; Pow, 2014). This perspective frees policy fields from the cognitive constraints imposed by static geographical boundaries, conceptualizing them instead as dynamic networks that undergo continuous topological transformations (Prince, 2016; see also Allen and Cochrane, 2010). It breaks through the shackles of geographical boundaries on policy innovation and highlights the spatial topological structure of global policy governance (Lewis et al., 2016).

This spatial topology is evident in two interconnected dimensions: first, Global think tanks and international standard organizations, including the OECD, are increasingly influencing local governance through advanced mechanisms such as algorithmic standards and evaluation indicators (Prince, 2016). Second, local governance actors reshape the global governance landscape through the deterritorialization of knowledge (Amin, 2002). These interactions foster a resilient governance frameworkance space, in which the geographical landscape is shaped by networks of action rooted in specific topological proximities. It is a fluid (global) governance space characterized by “geographically distant but topologically adjacent” (Allen, 2011).

In view of this, this study argues for the need to develop a “power-sensitive” analytical framework to examine the power structure of (global) policy governance. First, it necessitates identifying the asymmetric power dynamics among policy nodes, such as international organizations, local governance actors, and their respective policy fields, in order to uncover the power structure within the policy governance space. Second, it calls for an exploration of how explicit disciplines (e.g., institutional constraints) and implicit factors interactetration (e.g., standards and evaluations) of power collectively construct a hierarchical knowledge order. These mechanisms directly or indirectly shape the ways global knowledge is collected, adapted, and implemented locally (Allen and Cohrance, 2010). Third, it is necessary to ask how the inequality of knowledge power among policy actors guides the rhizomatic expansion of policy in networks, illuminating the underlying power relations that dominate the production and circulation of global knowledge.

In this regard, the study proposes three methodological innovations: Firstly, by integrating social network analysis with institutional ethnography, we suggest to use quantitative methods to discern the power heterogeneity among policy nodes, followed by qualitative tracking to unveil negotiations between local and external actors, thereby illuminating the topological power relations within policy governance. Secondly, we propose to construct a power evaluation model and delve into how explicit power discipline, such as institutional constraints,) and implicit power (e.g., standard evaluation) drive both “knowledge domestication” and “creative resistance” (Clarke, 2012; Longhurst and McCann, 2016). It aims to understand how standardized knowledge reshapes local cognition through the process of domestication, and how “creative resistance” emerging from local practices challenges and disrupts global knowledge hegemony (Lane, 2022; Temenos and McCann, 2013). This helps to identify the power imprints embedded in the assembly of heterogeneous knowledge. Third, to integrate spatial narrative and digital mapping techniques and track the cross-node flow of heterogeneous knowledge. It helps to restore the topological spatial “picture” of policy mobility and uncover the power geography of global knowledge production and circulation.

Conclusion

This study introduces an alternative analytical framework to decipher the intricacies and fundamental logics governing policy mobility in the globalization epoch. Policy mobility is now recognized as a complex, networked process, shaped by the interplay of various actors, diverse knowledge systems, and power dynamics, rather than a straightforward process of geographical transplantation or linear diffusion. By incorporating Deleuze’s rhizomatic thinking, this research establishes a framework to transcend the linear paradigm of traditional policy studies.

First, policy generation is conceptualized as “rhizomatic evolution” within a non-hierarchical topological structure. Innovation emerges as a product of the serendipitous connections of fragmented knowledge across various localities, rather than being the result of a rational design by a single node. Second, a “temporal-spatial folding” analytical paradigm is introduced to illustrate how policy innovation creates a dynamic mechanism of space-time compression. This mechanism arises from the compression of temporal hierarchies, the superposition of heterogeneous spaces, and the recalibration of knowledge-power relations. Finally, the metaphor of the geographical container is deconstructed by establishing a “knowledge-power-space” framework. This elucidates the roles of explicit power constraints and implicit power penetrations that guide global knowledge production and mobility within governance networks.

By emphasizing the innovative emergence of policies and the dynamics of space-time, this study highlights the “process ontology” inherent in policy mobility. Local policies are formed through the ongoing incorporation and integration of diverse knowledge from various contexts, leading to governance strategies that are distinctive locally while adaptable globally. This scenario is neither a straightforward “localization of global models” nor a unidirectional “local resistance.” Instead, it signifies a creative reorganization of multidimensional forces within an intricate framework of space and time.

Through the construction of a temporal-spatial folding and power topology analytical framework, this study dismantles the metaphor of geographical space as a mere container for policy, offering new tools to unravel the epistemological myths and geographical paradoxes of policy innovation. On one hand, by analyzing space-time folding, this study transcends the simplistic binary opposition between “global diffusion” and “local adaptation” prevalent in traditional policy studies, thereby uncovering the intricate interplay between. On the other hand, the focus on power topology reveals the often-invisible power structures within global governance networks, illustrating how strategic compromises between international and local actors co-create the power map of policy mobility, reflecting the geographical dynamics of power relations that underlie global knowledge production.

This alternative analytical framework not only broadens the research perspective on policy mobility but also offers methodological support for reconstructing the dialectical relationship between “global governance” and “local action.” Future research might benefit from incorporating social network analysis and digital humanities techniques, thereby enabling a deeper exploration of the dynamic trajectories of policy components within global topological networks and a more nuanced analysis of the micro-mechanisms underlying the interaction between power, knowledge, and space, and deepen our understanding of the complexities of policy evolution in the era of digital transformation.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study

References

Amin A (2002) Spatialities of globalisation. Environ Plan A 34(3):385–399

Allen J (2011) Topological twists: power’s shifting geographies. Dialogues Hum Geogr 1:283–298

Allen J, Cochrane A (2010) Assemblages of state power: topological shifts in the organization of government and politics. Antipode 42(5):1071–1089

Andersson I, Cook I (2019) Conferences, award ceremonies and the showcasing of ‘best practice’: a case study of the annual European week of regions and cities in Brussels. Environ Plan C Politics Space 39(8):1361–1379

Baker T, McCann, Temenos C (2020) Into the ordinary: non-elite actors and the mobility of harm reduction policies. Policy Soc 39(1):129–145

Bennett CJ (1991) What is policy convergence and what causes it? Br J Political Sci 21(2):215–33

Borén T, Young C (2021) Policy mobilities as informal processes: evidence from “creative city” policy-making in Gdańsk and Stockholm. Urban Geogr 42(4):551–569

Brenner N, Peck J, Theodore N (2010) variegated neoliberalization: geographies, modalities, pathways. Glob Netw 10(2):182–222

Bulkeley H (2006) Urban sustainability: Learning from best practice? Environ Plan A 38(6):1029–1044

Clarke N (2012) Urban policy mobility, anti-politics, and histories of the transnational municipal movement. Prog Hum Geogr 36(1):25–4

Cohen D (2015) Grounding mobile policies: ad hoc networks and the creative city in Bandung. Indonesia. Singap J Trop Geogr 36(1):23–37

Collier S, Ong A (2015) Global assemblages, anthropological problems. In Ong A, Collier S (eds) Global assemblages: technology, politics, and ethics as anthropological problems. Blackwell, Malden, pp 3–2

Cook I, Ward K (2011) Trans-urban networks of learning, mega events and policy tourism: the case of Manchester’s commonwealth and Olympic Games projects. Urban Studies 48(12):2519–2535

Deleuze G, Guattari F (1987) Introduction: rhizome. In: Deleuze G, Guattari F. (eds.) A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press, Minnesota, p 2, 3–25

Deleuze G, Guattari F (eds.) (1994) What Is Philosophy? Verso, London

Dolowitz D, Marsh D (1996) Who learns what from whom? A review of the policy transfer literature. Political Studies 44(2):343–357

Dolowitz D, Marsh D (2000) Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance 13(1):5–23

Dussauge-Laguna M (2012) On the past and future of policy transfer research: Benson and Jordan revisited. Political Stud Rev 10(3):313–324

Enseñado E (2024) City-to-city learning: a synthesis and research agenda. J Environ Policy Plan 26(1):14–29

Frick C (2022) Cross-fertilizing knowledge, translation, and topologies: learning from urban housing policies for policy mobility studies. Geogr Helv 77:405–416

Guggenheim M, Söderström O (eds) (2010) Re-shaping cities. How global mobility transforms architecture and urban form. Routledge, Oxon

Hartong S (2018) Towards a topological re-assemblage of education policy? observing the implementation of performance data infrastructures and ‘centers of calculation’ in Germany. Glob Soc Educ 16(1):134–150

Hartong S, Ubras C (2023) Analyzing (and comparing) policy mobilities in Federal Education Systems: potentials of a topological lens. Educ Policy Anal Arch 31(71):1–21

Jacobs J (2012) Urban geographies I: still thinking cities relationally. Prog Hum Geogr 36(2012):412–422

Knill C (2005) Introduction: cross-national policy convergence: concepts, approaches and explanatory factors. J Eur Public Policy 12(5):764–774

Kivimaan P, Rogger KS (2020) Interplay of policy experimentation and institutional change in sustainability transitions policy mixes: the case ofmobility as a service in Finland. Policy Res 51(1):104412

Lane M (2022) Policy mobility and postcolonialism: the geographical production of urban policy territories in Lusaka and Sacramento. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 112(5):1350–1368

Lewis S, Sellar S, Lingard B (2016) PISA for schools: topological rationality and new spaces of the OECD’s global educational governance. Comp Educ Rev 60(1):27–57

Longhurst A, McCann E (2016) Political struggles on a frontier of harm reduction drug policy: geographies of constrained policy mobility. Space Polity 20(2016):109–123

Massey D (1991) A Global sense of place. Marxism Today, pp 24–29. https://banmarchive.org.uk/marxism-today/june-1991/a-global-sense-of-place/

McCann E (2011) Urban policy mobilities and global circuits of knowledge: toward a research agenda. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 101(1):107–130

McCann E, Ward K (eds) (2011) Mobile urbanism: cities and policymaking in the global age. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

McCann E, Ward K (2012) Policy assemblages, mobilities and mutations: toward a multidisciplinary conversation. Political Stud Rev 10(3):325–332

McCann E, Ward K (2015) Thinking through dualisms in urban policy mobilities. Int J Urban Reg Res 39(4):828–830

McFarlane C (2011) Learning the city knowledge and translocal assemblage. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester

McKenzie M (2017) Affect theory and policy mobility: challenges and possibilities for critical policy research. Crit Stud Educ 58(2):187–204

Mocca E (2018) ‘All cities are equal, but some are more equal than others’. Policy mobility and asymmetric relations in inter-urban networks for sustainability. Int J Urban Sustain Dev 10(2):139–151

Müller M, Schurr C (2016) Assemblage thinking and actor network theory: conjunctions, disjunctions, cross-fertilisations. Trans Inst Br Geogr 41(2016):217–229

Peck J (2011) Geographies of policy: from transfer-diffusion to mobility-mutation. Prog Hum Geogr 35(6):773–797

Peck J, Theodore N (2012) Follow the policy: a distended case approach. Environ Plan A 44(2012):21–30

Peck J, Theodore N (2001) Mobilising policy models, methods and mutations. Geoforum 41(3):169–174

Pow C (2014) License to travel: policy assemblage and the ‘Singapore model’. City 18(3):287–306

Prince R (2016) Local or global policy? Thinking about policy mobility with assemblage and topology. Area 49(3):335–341

Robinson J (2015) Arriving at urban policies: The topological spaces of urban policy mobility. Int J Urban Reg Res 39(4):831–834

Rogers EM (1962) Diffusion of innovation. The Free Press, New York

Rowe JE (2009) Towards an alternative theoretical framework for understanding local economic development. In: Rowe JE (ed) Theories of local economic development: linking theory to practice. Routledge, London, pp 329–354

Roy A, Ong A (eds.) (2011) Worlding Cities: Asian experiments and the art of being global. Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, Oxford

Savage (2020) What is policy assemblage? Territ Polic Gov 8(3):319–335

Shipan C, Volden C (2012) Policy diffusion: seven lessons for scholars and practitioners. Public Adm Rev 72(6):788–796

Searle G, Darchen S (2023) New urban sustainability policies: Deleuze and local innovation versus policy mobility. Plan Theory Pract 24(1):133–139

Stone D (2012) Transfer and translation of policy. Policy Stud 33(6):483–499

Temenos C, McCann E (2013) Geographies of policy mobilities. Geogr Compass 7(5):344–357

Temenos C, T Baker (2015) Enriching urban policy mobilities research. Int J Urban Reg Res 39(4):841–843

Tozer L, Klenk N (2018) Discourses of carbon neutrality and imaginaries of urban futures. Energy Research & Social Science 25:174–181

Ward K (2006) Policies in motion, urban management and state restructuring: the trans-local expansion of business improvement districts. Int J Urban Reg Res 30(1):54–75

Ward K (2012) Entrepreneurial urbanism, policy tourism, and the making mobile of policies. In Bridge G, Watson S. (eds.) The New Blackwell Companion to the City, Blackwell Publishing, New York

Wood A (2015) Multiple temporalities of policy circulation: gradual, repetitive and delayed processes of BRT adoption in South African cities. Int J Urban Reg Res 39(3):568–580

Wood A (2016) Tracing policy movements: methods for studying learning and policy circulation. Environ Plan A 48(2):391–406

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank those who helped in the field trip. All errors remain us.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JG was responsible for the entire process of the original and revised manuscripts, encompassing conceptualization, methodology design, analysis, drafting, and comprehensive revision based on reviewer feedback. HZ contributed sections on the conceptual framework and methodology. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This study does not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, J., Zhang, H. Decoding policy mobility through a rhizomatic lens: spatiotemporal folding and power topology in translocal governance. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1246 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05433-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05433-3