Abstract

As the era of mandatory telework ends, managers face decisions on maintaining telework options. This study investigates the psychological impact of choice in telework on employee performance and life satisfaction based on self-determination theory. Analysis using PLS-SEM (N = 809, Hungarian sample) reveals that autonomy-supportive leadership in telework settings significantly enhances employee performance and overall life satisfaction, supporting the mutual gains theory. The research discloses the relationship between autonomy-supportive leadership, the practice of giving freedom for employees to work from anywhere, control over the work environment, autonomy, and the indicators of personal performance and satisfaction with life in an organisational context. The study contributes to understanding the direct and indirect mechanisms through which leadership and human resource management practices influence personal performance and satisfaction with life. The research findings provide practical guidance for managers to reduce “productivity paranoia” in the hybrid work context and confirm that not only do happier employees perform better, but better performance can also contribute to life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Digital transformation has profoundly impacted organisational structures, driving a shift towards post-bureaucratic models characterised by low formalisation, networked collaboration, and decision-making autonomy (Mustafa et al., 2022). In this context, the transition to telework, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has highlighted the importance of psychological factors such as autonomy in influencing employee outcomes (Huang, 2024). This study explores how autonomy-supportive leadership in telework settings affects employee performance and life satisfaction, addressing critical gaps in understanding the psychological underpinnings of effective telework practices. Technological advances give organisations more flexibility than ever to allow employees to choose where they work. However, this is an option that companies can choose depending on several organisational features, including the leadership culture, which is characterised by the aspects of control and trust. A popular, consistent, and widely accepted leadership objective is enhancing performance and related indicators, such as shareholder financial returns. Researchers have answered the question of whether there is another purpose, another way of creating value, in diverse ways over time. Although authors have come a long way, at least in the literature, from defining leadership as the centralisation of control, dominance, and power (Moore, 1927); however, the role of followers as important stakeholders has taken a long time to be recognised. Amid several forces like the newest technological progress, the entry of new generations into the labour market, the talent shortage, and the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, managing the employee experience is becoming increasingly important (Singh et al., 2024). While there is an emerging demand for understanding the soft factors of the work from employers and employees (Chen et al., 2024), there is rarely a practical research-based response in the literature.

Borrowing the concept of “mutual gain” from the HRM literature (Voorde et al., 2012), the question can also be formulated as to whether the results of management and leadership practices can be positive for both employers and employees, and it specifically applies to a telework context.

The mutual gains perspective stipulates shared benefits for the organisation and employees (Voorde et al., 2012). The framework of the mutual gain approach examines the feasibility of a win-win leadership practice, where high performance is accompanied by employee satisfaction with life (Minz, 2024). The key assumption is that HRM systems (highly influenced by leadership practice) must create a win-win situation in which positive employee attitudes are critical for achieving performance improvements (Appelbaum et al., 2000).

Amidst the described evolving human-centred leadership paradigm, the advent of widespread telework (Itam and Warrier, 2024), accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has introduced new dynamics in organisational leadership. Research on the pandemic-driven transition to mandatory telework demonstrated that support emerges as the critical factor driving positive work outcomes, while control can be beneficial only if balanced by sufficient support. This challenges the idea that leaders must rely heavily on controlling their teams to be effective (Gan et al., 2022; Bilodeau et al., 2024) and underscores the importance of managerial support in telework settings, which has become more prevalent post-crisis (A. L. Allen and Birrell, 2024).

However, this transition has also given rise to “productivity paranoia,” a phenomenon where leaders, unable to observe their employees directly, express doubts about their productivity in remote settings (Hirsch, 2023). This paranoia is further compounded by a phenomenon known as the “productivity paradox”, revealed by a large global sample of Microsoft research, which found that 87% of employees think they are productive in hybrid work, compared to only 12% of managers who believe the productivity of their teams (Microsoft, 2022). Meyer (2023) considered the reason behind the problem that employees sense the paranoia of the managers and mirror it themselves to create the virtuous circle of mutual distrust. Zheng et al. (2023) found that daily monitoring of employees by supervisors negatively impacts employees’ well-being. These research reports highlighted a critical gap in trust, emphasising the need for a shift in leadership focus from oversight to outcome-based performance assessment. Such a transition needs more preparation and specific knowledge on how trust, control mechanisms, flexible work arrangements, workers’ basic psychological needs, and experiences interplay (Pianese et al., 2023; Ficapal-Cusí et al., 2024).

The share of teleworking in Hungary peaked in May 2020, when it jumped fivefold from a year earlier to 17% of the total employed population, and has been slowly but steadily declining since then, but was still at 7.3% in 2023 (KSH, 2024). However, according to Randstad’s research (Baja, 2024), 91% of Hungarian employers no longer plan to change the number of days spent with telework. Still, where changes are planned, further slight reductions are expected. However, hybrid work serves as a significant attraction and retention factor in the labour market, and leaders play a crucial role in maintaining an appropriate organizational climate within this context. When fuelled by fear and paranoia, practices tend to focus more on exercising control over employees by requiring physical presence and frequent reporting. Now, especially those practices that promote work-life balance, employee well-being, and a positive work environment, contribute to higher employee engagement and performance by providing flexibility in work arrangements and fostering a supportive climate (Jiang et al., 2012; Kehoe and Wright, 2013; Aprilina and Martdianty, 2023). In this new era, flexible work arrangements gain a distinguished interest as there are few empirical findings on what practices work with mutual gain in this context (Jain et al., 2024).

When approaching autonomy in a contextual sense (Racine et al., 2021), an important question is what value it represents for workers. Addressing the question, Pianese, Errichello, and Vieira (2023) found that although remote workers value autonomy, it needs to be balanced with effective control systems and management practices that support trust and organisational identification. This balance is key to ensuring that the autonomy granted to remote workers leads to positive outcomes for both the employees and the organisation (Tsang et al., 2023). Our research highlights the crucial role of managerial support in the context of telework, which is more widely enabled than before the crisis.

This paper explores the relationship between the autonomy-supportive leadership practice of creating a trustful social context, giving employees the choice to work from anywhere, control over the work environment, perceived managerial autonomy support, and indicators of personal performance and satisfaction with life in an organisational context. By examining existing literature and empirical evidence, this study seeks to contribute to understanding the mechanisms of trust and control among leaders, followers, and their environment, as well as how these influence employee outcomes, ultimately providing valuable insights for organisational leaders and HR professionals.

Theoretical background

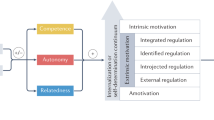

Theory of self-determination in the workplace

Self-determination theory (SDT) is a well-established framework that focuses on individuals’ motivation and psychological needs in various contexts, including the workplace (Deci et al., 1989). In essence, the theory identifies psychological needs that should be satisfied for people to thrive, grow, and develop. These basic needs are autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci and Ryan, 2000). SDT refers to having a sense of choice in initiating and regulating one’s actions (Deci et al., 1989). In the work context, it emphasizes leadership approaches that prioritize understanding and addressing employees’ motivations by providing them with the support they need to thrive. The authors of the theory, Deci et al., found the antecedents of their ideas in approaches that reinforce in employees a sense of being valuable (Bowers and Seashore, 1966), deserving of attention (Halpin and Winer, 1957), and worthy of supportive relationships (Likert, 1961). Deci et al. (1989) have developed these ideas further, providing more specific guidance to managers regarding the factors they should consider when providing leadership support.

Early research in SDT emphasised the significance of the need for autonomy, particularly in explaining the detrimental effects of extrinsic incentives on intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 1999). It was observed that when individuals feel externally coerced or controlled, their intrinsic motivation to engage in activity diminishes. In contrast, when individuals experience autonomy in their actions, their intrinsic motivation is more likely to thrive.

SDT research within the workplace context has addressed the dual concerns of organisations, namely, being profitable and promoting employee motivation and wellness (Deci et al., 2017). Most often, various contextual factors (e.g., leadership style, job design) and their relationship with motivation, psychological need satisfaction, and outcomes have been examined. More complex research has also included the narrower concept of autonomy support, and has shown that psychological need support and autonomy support are very closely related and have remarkably similar consequences (ibid.). Deci, Olafsen, and Ryan (2017) have developed a self-determination theory model for the workplace in which they have outlined three sets of variables: (1) the first set of independent variables typically comprise social context variables (e.g. need supporting, need thwarting) and individual differences variables (e.g. aspirations and goals); (2) the second set includes two types of mediating variables, namely the satisfaction of basic psychological needs and the type of motivation; (3) and the third set of dependent variables are concerning performance (e.g. quality or quantity of performance) and well-being (e.g. life satisfaction, job satisfaction, etc.).

Gillet et al. (2012) have already proven the mediating function of need satisfaction and found that aspects of workers’ well-being were predicted by the perceptions of their supervisor’s autonomy support and the satisfaction of their basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Recent research shows that autonomy satisfaction is influenced by the social context (Lauring and Kubovcikova, 2022). Therefore, the involvement of the trust-based work climate is an adequate choice. Although the specific job design issues raised by changing workplace conditions have rarely been examined from the perspective of SDT, the possibility of working from home raises critical issues for employee motivation, engagement, performance, and well-being. The authors would like to fill this gap with this research, in which the Hungarian population was surveyed with an interest in the relationships of variables that can be placed alongside the model of Deci, Olafsen, and Ryan (2017). The variables are shown in Table 1.

Work contextual factors as independent variables included the choice of work-from-home and autonomy-supportive climate, which the authors hypothesised would affect basic psychological need satisfaction, measured by autonomy, and a closely related but distinct control construct, measuring workers’ perceptions of how much control they have over their work environment. Among the output variables, both work behaviour and wellness variables were examined along the lines of mutual gain theory. Along with current SDT research, this study operationalises psychological well-being through the indicator of life satisfaction measurement, considering that this output variable may help capture an individual’s subjective well-being and overall functioning.

Research constructs and hypotheses development

Choice of work-from-home

The concept of choice in the context of working from home (WFH) addresses a key practical concern within hybrid work environments. Specifically, we examine how the possibility to select one’s work environment influences employee motivation, focusing on its relationship with perceived autonomy and control. Choice refers here specifically to the choice of location and space of the physical working environment, i.e., the freedom for workers to choose whether they work from home (WFH) or any remote location, or from their place of work. Such freedom also involves a more personalised work schedule. Conceptually, choice is treated as an idealized construct, serving both as a model for rational decision-making and as a mechanism that fosters freedom and autonomy (Dan-Cohen, 1992).

The practice of giving the freedom to choose the physical environment (work from home) has been shown to have an impact on labour flows (Earle, 2003). Organisations that prioritise perks and benefits that contribute to a better quality of life for their employees tend to create a more positive and engaging work environment. One type of benefit that can significantly enhance employees’ quality of life is flexible work arrangements. Flexible work arrangements like flex-time or flex-space, like the choice of working-from-home are associated with control in various studies (Hill et al., 2001; Halpern, 2005; Jeffrey Hill et al., 2008) moreover, it is defined as a concept that leads to perceived control in employees through the possibility of choices (Gašić and Berber, 2023). As defined by Fisher (1990), the concept of personal control emphasises mastery over the environment, where individuals with control can change or reverse situations they find unfavourable. Allen and Greenberger (1980) further elaborate that, in the context of the built environment, an individual’s sense of control increases by altering or modifying their surroundings. This can include personalising individual workspaces or changing the physical structure of a building. Lee and Brand (2005) hypothesised that the flexibility to choose or change aspects of one’s workspace according to individual or group needs will enhance perceptions of personal control and levels of interpersonal communication, potentially leading to greater group cohesion.

The process of choice-making facilitates the ability of individuals to exert control over their environment. Leotti et al. (2010) explain that such decisions span a broad spectrum, ranging from complex and emotionally significant choices that occur infrequently, such as selecting a university, to fundamental perceptual choices that arise numerous times each day, such as deciding where to work. While environmental cues may drive a substantial portion of behaviour and occur below the level of conscious awareness, all voluntary actions are inherently tied to the act of choice-making. Consequently, the authors suggest that choice serves as a fundamental mechanism for satisfying the basic need for autonomy (ibid.).

H1: Choice of WFH has a positive effect on control over the work environment.

H2: Choice of WFH has a positive effect on autonomy.

Perceived managerial autonomy support

Building on the notion that choice-making underpins autonomy, as outlined by Leotti et al. (2010), we extend this perspective by incorporating Deci, Olafsen, and Ryan’s (2017) SDT framework, which emphasizes the role of an autonomy-supportive organizational climate. In this context, we examined how such a climate, characterized by trust in employees, enhances their motivation by fostering a greater sense of autonomy and control. This dynamic, we posit, not only improves employees’ well-being but also enhances their performance. Managerial autonomy support refers to a set of supervisory behaviours that are postulated to enhance employees’ self-determined motivation, thereby indirectly fostering their well-being and performance (Slemp et al., 2018). Given the emphasis in SDT research on the study of workplace contextual factors and their interaction, the influence of managerial behaviour has also been repeatedly shown to be a factor in the sense of autonomy, which can also result from the individual motivational style of managers (Reeve, 2015). Notably, autonomy support primarily pertains to the interpersonal climate created by managers in their interactions with subordinates and the execution of managerial functions such as goal setting, decision-making, and work planning. In this study, perceived managerial autonomy support is defined as a facet of the workplace climate in which managers create a trusting and supportive atmosphere in the organisation in terms of leader-follower relationships (Reeve, 2015).

A substantial body of research in the field of management studies has consistently demonstrated that fostering autonomy-supportive environments leads to significant positive outcomes, including enhanced self-motivation, increased satisfaction, and improved performance across various contexts. (Deci et al., 1981). For instance, Deci et al. (1989) observed that higher levels of managerial autonomy support, which included informational feedback and encouraging “self-initiation”, led to increased trust, overall job satisfaction, and positive work attitudes among work-group members. Trust is crucial in remote work arrangements. Remote workers who feel trusted report higher satisfaction and alignment with organisational objectives (Pianese et al., 2023).

Ravenelle (2019) examined the practical implementation of the managerial mindset derived from autonomy-supportive Y theory and found a direct link between the impact of control and the work environment of employees. The findings of Rathi and Lee (2017) demonstrate a positive correlation between supervisor support and quality of work life. Additionally, they have observed that the quality of work life exhibits a positive association with both organisational commitment and life satisfaction, which might indicate a direct link between autonomy support and life satisfaction. Spillover theory also assumes a link between a supportive work environment and the overall life satisfaction of employees. Trust-based supervisor-employee relationships may also reduce workplace uncertainty by fostering self-determination (e.g., autonomy) that might predict employee performance (Skiba and Wildman, 2019):

H3: Perceived managerial autonomy support positively affects autonomy.

H4: Perceived managerial autonomy support has a positive effect on control over the work environment.

H5: Perceived managerial autonomy support positively affects perceived performance.

H6: Perceived managerial autonomy support has a positive effect on satisfaction with life.

Control over the work environment

Extending the discussion on autonomy-supportive environments, we explored the role of perceived control as a central element of intrinsic motivation, aiming to understand how employees’ sense of agency over their working environment impacts both their well-being and overall satisfaction. Much of the early work in management psychology centres on the study of personal control over the work environment. In an attempt to provide a synthesis of the literature, Greenberger and Strasser (1986) defined personal control as “an individual’s beliefs, at a given point in time, in his or her ability to effect a change, in a desired direction, on the environment” (p.165). Sutton and Kahn (1986) proposed a model in which they identified antidotes to the stress-strain relationship in organisational life. These antidotes were understanding, prediction, and control over events, among which control refers to “control the outcomes desired by effectively influencing the events, things, or others in the work environment” (Tetrick and LaRocco, 1987, 538).

Control, however, comprises several constructs in an organisational setting and has been associated with job satisfaction, autonomy satisfaction, self-determination in general, and performance outcomes (Skinner, 1996). For example, as a result of research conducted in a smart home-office context, Marykian et al. (2024) found that control over environmental conditions positively affects perceived well-being. Another study on open-plan offices (Samani et al., 2015) found that while open-plan offices offer greater flexibility and more options than fully enclosed and private offices, they can negatively affect employee satisfaction and performance due to a lack of personal control over the work environment.

Several studies have explored a positive relationship between higher levels of control, performance, and well-being (Mc Laney and Hurrell, 1988; Greenberger et al., 1989). Peterson (1999) wrote about the ‘age of control’ when it is becoming even more important for individuals to exercise control over even more areas, and by achieving greater control, they are heading towards a higher level of life satisfaction. In addition, Near et al. (1984) noted how perceived working conditions and the degree to which employees influence them significantly impact overall life satisfaction.

The concept of perceived control suggests that control is fundamentally a subjective experience shaped by a series of cognitive processes. These processes enable individuals to organize, interpret, and make sense of complex environmental information in a coherent manner. As Skinner (1996) stated, “perceived control constructs are frequently confused with belief systems that result from experiences of autonomy” (p. 557); however, control and autonomy are different constructs. According to Deci and Ryan (1985), there exist noteworthy distinctions between the constructs of control and self-determination: control delineates the presence of a causal relationship between one’s conduct and the outcomes garnered, whereas autonomy encapsulates the sensation of unrestrained initiation of one’s conduct. Accordingly, such differentiation stems from differences in the need for autonomy and the need for competence. Hereby, the authors suppose that the control construct, according to which employees have perceived control over their work environment factors, affects their sense of autonomy satisfaction. Relatedly, the authors found some other studies arriving at very similar results. For example, in their qualitative study, Ravenelle (2019) explored gig economy workers according to X and Y theory and found that entrepreneurs, when treated according to the inherent theory X, experience less control over their physical work conditions and report a violation of their sense of autonomy satisfaction.

H7: Control over the work environment has a positive effect on autonomy (satisfaction).

H8: Control over the work environment has a positive effect on perceived performance.

H9: Control over the work environment has a positive effect on satisfaction with life.

Autonomy satisfaction

Building on our exploration of perceived control as a key component of intrinsic motivation, we further addressed the dilemma of work environment choice by examining workers’ motivation, specifically focusing on their satisfaction with autonomy. Grounded in the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), autonomy is recognized as a fundamental psychological need that must be fulfilled to foster relatedness, promote well-being, and support personal growth and integrity. (Trougakos et al., 2014). Following the definition of SDT theory, the authors consider autonomy as the need for individuals to experience a sense of ownership and psychological freedom in their actions (Deci and Ryan, 2000). This need is rooted in the concept of locus of causality, which pertains to individuals being the origin of their behaviour rather than being controlled by external forces (Charms, 1968).

According to self-determination theory, extrinsic and intrinsic motivations can be ordered on a scale, where extrinsic motivation is the more externally controlled type and intrinsic motivation is the more autonomous or volitional type. However, these have different effects on employee outcomes (Deci and Ryan, 2000). Several studies have explored the numerous positive effects of autonomy on the outcomes of individuals and their organisations. Employees who were autonomously motivated experienced greater well-being, happiness, and energy while demonstrating greater focus, perseverance, and effort in their work, leading to higher overall performance and productivity (Gagné and Deci, 2005).

H10: Autonomy has a positive effect on perceived performance.

H11: Autonomy has a positive effect on satisfaction with life.

Perceived performance

Building on the relationship between autonomy and well-being, we extended our analysis to consider the employees’ perceived performance, drawing on insights from mutual gain theory. Specifically, we hypothesize that the possibility of choosing the work environment, such as working from home within a hybrid model, positively influences motivation. This enhanced motivation, in turn, is expected to improve performance and contribute to overall life satisfaction. Employee performance is defined as the accomplishment of work after acting by their authority and responsibility and making the necessary efforts on the relevant work (Hellriegel et al., 1999). Siengthai and Pila-Ngarm (2016) defined employee performance as the ability to perform work and found that satisfaction with performance increases as this ability grows. Individual performance highly depends on organisational and environmental settings. Managers need to build an environment that allows them to measure and monitor employees ‘ attitudes, motivation, and opinions (Fatima et al., 2020). The majority of empirical studies that have been conducted and published on this subject support the idea that there is, at best, a tenuous connection between performance and satisfaction (Jones, 2006).

H12: Perceived performance has a positive effect on satisfaction with life.

Satisfaction with life

Building further on the mutual gain framework, our analysis examined employees’ satisfaction with life as one of the key outcomes of, focusing on how it is influenced by the freedom to choose remote work arrangements and the presence of a trust-based climate in hybrid organizations. According to the thematic OECD report by Smith and Exton (2013, 29), subjective well-being means a “good mental state including all of the various evaluations, positive and negative, that people make of their lives and the affective reactions of people to their experiences.” It is an umbrella term that includes different valuations of people’s lives, which are experienced internally. A large body of research in this area made a distinction between three concepts of well-being: (a) life evaluation as a whole; (b) the measures of effect, which capture the feelings experienced by the respondent at a particular point of time; (c) the eudemonic aspect expressing the sense of engagement and purpose of people (Peterson, 1999). There is a clear dearth of consensus among researchers that life evaluation means an overall assessment of satisfaction with life across its various domains.

Methodology

Sample and data collection procedure

Primary data collection and database compilation were conducted by an external, contracted Hungarian market research company within the framework of the Corvinus University of Budapest omnibus survey. The data were collected between November and December 2022 on Hungary’s largest market research panel, which provides access to approximately 203,000 potential Hungarian respondents.

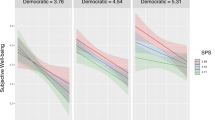

Data collection was conducted by a representative online survey of 18-59-year-old internet users in Hungary. It used quota sampling to form a representative dataset in terms of age (18-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59), gender, type of municipality (capital, county seat, town, village), education (primary, lower secondary, upper secondary, tertiary), and region (Central Hungary, Northern Hungary, Central Transdanubia, Northern Great Plain, Southern Transdanubia, Southern Great Plain and Western Transdanubia). The quota of demographic data on age, gender, type of municipality, education, and region are recorded based on the national demographic distributions (in 2022) published by the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH). The data collection output included SPSS and Excel databases. The original sample included 1,000 respondents, but there was a need to remove some respondents without active jobs. The finalised number dataset included evaluable data of 809 participants.

The demographic characteristics of 809 respondents are presented in Table 2. The sample is ensured to be representative of the total population by the first three criteria (sex, age, and municipality). Some other descriptive statistics about the sample (different employment data and parent status) were not part of the criteria for representativeness, however, they are also relevant to the study analysis.

Data analysis

The research data analysis used the partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) by ADANCO software (version 2.3.1) and SPSS (Version 27). Hair et al. (2017) suggest that PLS-SEM is particularly suitable compared to CB-SEM when the research objective is to better understand increasing complexity by exploring theoretical extensions of established theories, making it ideal for exploratory research aimed at theory development.

The aim of using the PLS-SEM method here was to test predefined hypotheses among six constructs (Choice of Work-from-Home, Autonomy support, Control over the Work Environment, Autonomy, Job Performance and Satisfaction with life) but also to develop managerial recommendations in a predictive way (Dijkstra and Henseler, 2015). Each construct was measured on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Measures

The measures of this study were mainly adopted from validated scales, besides self-developed ones. Table 3 summarizes the indicator items for all constructs, the basic descriptive statistics (mean, variance), and the factor loading for each item. Items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale, and the variance of the statements was concentrated around a moderate value (see Table 3).

Choice of Work-from-Home is a self-developed one-item scale measuring the degree of freedom to work from anywhere. Interestingly, respondents assigned a relatively lower value to this item (2.75), indicating they experienced a low level of freedom of choice. Perceived Managerial Autonomy Support was measured with the Work Climate Questionnaire (WCQ), which is a 15-item scale adapted from two comparable questionnaires (Williams et al., 1996) by Baard, Deci, and Ryan (2004). The authors have used the short form of the Work Climate Questionnaire, containing six of the items. The questionnaire was used concerning specific work settings. In these cases, the questions pertained to the autonomy support of the respondents’ manager. For these statements, the means typically clustered around the neutral value. To measure Control over the Work Environment, the authors used the scale of Tetrick and LaRocco (1987) to study the extent to which employees perceive their control over their work environment. For these statements, the means remained somewhat below the neutral value. Autonomy satisfaction was measured by the subscale of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Need Frustration at Work Scale validated by Olafsen & Deci (2020). Performance was measured on a three-item self-developed scale, comprising one item concerning perceived productivity, effectiveness, and quality of the job, resulting in means somewhat above the neutral value. Initially, Satisfaction with life was measured using the validated Hungarian version (Martos et al., 2014) of the satisfaction with life scale (Diener et al., 1985). The mean values for the related statements are located around or slightly below the neutral point.

Empirical results

The first stage in evaluating PLS-SEM results is to examine the required criteria of the measurement models, the second is to assess the structural model (Hair et al., 2017).

Measurement model assessment

Assessing reflective measurement models begins with indicator loadings. Standardised factor loadings should exceed 0.5 and ideally 0.7 (Hair et al., 2012). Table 4. indicates Dijkstra–Henseler’s rho values - the index of internal consistency reliability measure of constructs—which is well above the favourable 0.7 value in each case (Dijkstra and Henseler, 2015). Each construct meets the Cronbach’s requirement of 0.7 or higher. Convergent validity was measured using average variance extracted (AVE) values greater than 0.5 in each construct (Hair et al., 2012). The data meet the required criteria (Table 4).

Discriminant validity was measured by the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT2). All HTMT2 ratios were far below 0.85, with the highest 0.69, providing evidence of good discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2017).

In sum, sufficient statistical evidence was found to verify six constructs that the measured variables are appropriate indicators of the related factors and that the constructs are distinct.

Structural equation model and results

Only the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) model fit measure meets the criterion in PLS modelling with a cut-off value of 0.08 (Hu and Bentler, 1999). The model delineated in this study has an appropriate model fit as SRMR = 0.51. Table 5 and Fig. 1 demonstrate that every hypothesis was accepted (p < 0.05). In Fig. 1, R2 values are shown, ranging from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater explanatory power. R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 can be considered substantial, moderate, and weak (Hair et al., 2017), so Control over WE (R2 = 0.43), Autonomy (R2 = 0.27) and SWLS (R2 = 0.29) have a moderate, and Performance (R2 = 0.18) has a weak explanatory power.

Choice of work-from-home has a direct positive impact on control over the work environment (ß = 0.16; t-value = 5.94, p-value < 0.001) and on autonomy (ß = 0.07; t-value = 1.97, p-value = 0.024), resulting in the acceptance of hypotheses H1 and H2 (see Table 5).

Perceived managerial autonomy support has a direct positive impact on control over the work environment (ß=0.59; t-value = 20.31, p-value < 0.001), on autonomy satisfaction (ß = 0.23; t-value = 5.17, p-value < 0.001), on performance (ß = 0.25; t-value = 5.14, p-value < 0.001), and on SWLS (ß = 0.09; t-value = 1.98, p-value < 0.001), meaning the hypotheses H3, H4, H5 and H6 are accepted.

In line with the expectations, control over the work environment has a direct positive effect on autonomy satisfaction (ß = 0.31; t-value = 7.12, p-value < 0.001), on performance (ß = 0.17; t-value = 3.34, p-value < 0.001), and on SWLS (ß = 0.36; t-value = 7.60, p-value < 0.001), resulting in accepting H7, H8 and H9.

Autonomy has a direct positive impact on performance (ß = 0.08; t-value = 2.09, p-value = 0.018) and SWLS (ß = 0.11; t-value = 2.87, p-value = 0.002), meaning that H10 and H11 are accepted.

Finally, performance has a positive impact on SWLS (ß = 0.10; t-value = 2.60, p-value = 0.005), resulting in acceptance of H12.

Mediation effect analysis

Deci et al.‘s (2000) model of self-determination theory in the workplace considers the workplace context as an independent variable, performance and well-being as dependent variables, and the psychological needs between them (e.g., autonomy and competence) as mediators. Following this logic, we can ask the question: Does control over the work environment and autonomy satisfaction mediate the link between performance and SWLS?

The hypotheses on the mediation effects in this model are the following:

H13a: Control over the work environment mediates the relationship between perceived managerial autonomy support and performance.

H13b: Autonomy satisfaction mediates the relationship between perceived managerial autonomy support and performance.

H14a: Control over the work environment mediates the relationship between perceived managerial autonomy support and SWLS.

H14b: Autonomy satisfaction mediates the relationship between perceived managerial autonomy support and SWLS.

Mediation effect analysis was conducted using the logic of Zhao et al. (2010) and Hair et al. (2017). Table 6 shows that all mediating effects are complementary (partial mediation) and point in the same direction (Zhao et al., 2010). The indirect to total effect, the Variance Accounted For (VAF), was also calculated to analyse the complementary mediation.

As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 6, there are three indirect paths from perceived managerial autonomy support to performance (AS → CoWE → P, AS → A → P, AS→ CoWE → A → P), resulting in a complete indirect effect of 0.1348 [0.0760; 0.2004]. Based on the total indirect effect, VAF = 35.5%, and as this value is larger than 20 percent and less than 80 percent, it is characterised as a partial mediation (Nitzl et al., 2016). Hypotheses were developed for the first two paths.

First, control over the work environment mediates the relationship between perceived managerial autonomy support and performance. Table 6 demonstrates a significant indirect path from perceived managerial autonomy support through control over the work environment to performance, as 95% BPCI for the mediating effect does not straddle zero. The direct path from autonomy to performance was also significant, indicating that control over the work environment partially mediates (i.e., complementary mediates) the relationship between autonomy support and performance (H13a supported). Perceived managerial autonomy support directly increases performance, but CoWE additionally contributes to the explanation of performance, meaning the AS effect on performance was partially explained by CoWE (VAF = 26.2%).

The specific indirect path from AS through autonomy to performance (β = 0.0197 [0.0015; 0.0425]) indicates the complementary mediating effect of the CoWE on the relationship between autonomy support and performance (H13b supported), but with a marginal mediating effect (VAF = 5.2%). Higher autonomy support increases performance directly, and autonomy, which in turn leads to performance. Hence, AS on performance was slightly explained by autonomy.

Seven indirect paths lead from AS to SWLS as shown in Fig. 1. (AS→CoWE→SWLS, AS → A → SWLS, AS → P → SWLS, AS→CoWE→A → SWLS, AS → CoWE → P → SWLS, AS → A → P → SWLS, AS → CoWE → A → P → SWLS) resulting in a complete indirect effect of 0.1348 [0.0760; 0.2004]. The VAF based on the total indirect effects equals 76.2%; however, the authors described hypotheses using the two paths.

On the AS → CoWE → SWLS pathway, a stronger complementary mediation (VAF = 54.4%) can be observed (β = 0.2141 [0.1569; 0.2740]), while on the AS → A → SWLS path, a significant but weaker mediation (VAF = 6.7%) is observed (β = 0.0262 [0.0078; 0.0489]), resulting in the acceptance of H14a and H14b.

Discussion

In this analysis, the authors have explored the links between the climate of trust that supports autonomy, the choice of work location, the control and autonomy experienced by employees, and performance and well-being outcomes. The research results show that, while freedom of choice contributes to workers’ sense of control and self-determination, efforts to create a climate of trust in the Hungarian work environment have much greater influential power. Presumably, in the freedom of choice of location, employees are able to maintain a balance through the control systems established by the climate of trust.

Along with the research goal of examining mutual gain leadership practice in the new era of a hybrid work environment, we found several encouraging results for letting employees choose whether to work from anywhere. This is particularly true for countries with labour markets such as Hungary, which is characterised by a shortage of skilled labour and low geographical mobility of employees. In such circumstances, employees and employers can benefit from hybrid or fully remote working. The spread of telework and flexible work arrangements has brought significant changes in employees’ control over their work environment. Although the working environment is still primarily determined by the employers, the option of telework allows employees to influence it according to their preferences. There may be some elements of the telework environment that are predefined and provided by the employers (e.g., laptop, software, etc.); however, other elements may be freely chosen by the employees. This freedom gives the employee more control, which in turn contributes positively to the psychological need of autonomy, leading to both higher perceived performance and overall satisfaction with life at the same time. This finding substantiates the dual contribution of the studied leadership practice, both at the organisational and the individual level; thus, our findings support by Minz (2024) and Voorde et al. (2012), which underpin the theory of mutual gains.

Previous research studies confirmed that higher job autonomy improves employees’ work motivation and work effort (Huang, 2024) and higher empowering of employees improves the organisational outcomes (Ghimire et al., 2024). A key finding of this study indicates that when employees perceive a trust-based organisational climate coupled with opportunities for flexible work arrangements, both their performance and life satisfaction tend to improve within the emerging post-pandemic norms of work. The findings confirm that mutual gain is achievable and that leadership that supports autonomy plays a crucial role in this, which is in line with other streams of leadership research, e.g., the integration of transformational leadership with SDT in Kanat-Maymon et al. (2020).

Based mainly on the assumptions of Deci et al. (1981) and Deci, Olafsen, and Ryan (2017), the authors predicted that perceived managerial autonomy support increases the two output constructs not only directly but also indirectly. As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 6, there are three indirect paths from perceived managerial autonomy support to performance and seven indirect paths from perceived managerial autonomy support to satisfaction with life. These complementary mediating paths highlight the complex positive interrelation of components indicated by the SDT model. These links suggest that leaders who want to positively impact both performance and personal well-being may use telework opportunities to achieve their goals, alongside creating a workplace climate based on trust, considered as the foundation of autonomy support.

In this model, perceived managerial autonomy support increases not only performance directly but also through control over the work environment. In addition to that, managers who actively support employees’ autonomy not only contribute to better performance directly but also do so indirectly by cultivating an environment in which employees experience greater self-direction.

The model has seven indirect paths from perceived managerial autonomy support to satisfaction with life. A stronger complementary mediation is observed on the pathway of perceived managerial autonomy support, control over the work environment, and satisfaction with life. On the one hand, through autonomy, the mediation is weaker but still significant, meaning that higher levels of effective influence on the events, things, or others in the work environment result in higher levels of performance and well-being than experiencing a sense of ownership and psychological freedom in their actions.

Choice of work-from-home has a significant but weakly positive impact on control over the work environment and autonomy. This result differs from previous research, suggesting a stronger link. The weaker link indicated by this model underlines the importance of leadership that supports autonomy. This raises the possibility that the significance of the benefits of teleworking is highly dependent on the organisational culture and the level of managerial support.

Theoretical implications, limitations, and implications for management

Theoretical implications

The research extends the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by showing how autonomy-supportive leadership and choice of work environment affect control, autonomy satisfaction, performance, and life satisfaction. While SDT is well established in the workplace motivation research stream, its application in telework environments is underdeveloped.

The results contribute to the theory of mutual gains by showing how telework autonomy can be used to simultaneously increase workers’ welfare and performance. In contrast to previous research, which focuses primarily on the employer perspective, this study shows that employers’ support for workers’ choice of work-from-anywhere fosters greater control over the working environment. The fact that performance directly and positively influences life satisfaction is a new finding compared to previous studies, where the relationship between the two factors has generally been found to be in the opposite direction. The majority of empirical studies that have been conducted and published on this subject seem to support the idea that there is, at best, a tenuous connection between performance and satisfaction (Jones, 2006). While it is widely accepted that life satisfaction increases performance (Bosua et al., 2017), the opposite effect has not been extensively studied. The study challenges traditional assumptions that a high level of control is necessary for productivity, instead advocating a trust-based management approach.

The novel finding that a higher performance leads to higher life satisfaction could be rooted in the fact that high performance is often a sign of competence, which is another psychological need, not only in self-determination theory but also as “mastery” in Daniel Pink’s Motivation 3.0 (Pink, 2011). Autonomy often plays a facilitative role in the satisfaction of the other two basic psychological needs, particularly competence (Deci et al., 2017). When individuals act under external pressure or lack volitional engagement, they may not subjectively experience a sense of competence—even if they perform competently by objective standards. This implies that the experience of autonomy may be a prerequisite for the subjective realisation of competence. Our study contributes to this theoretical proposition by approaching and empirically testing the experience of competence in terms of perception of performance, thereby extending the understanding of how need satisfaction operates within telework contexts.

The research introduces control over the work environment as a mediating factor linking autonomy-enhancing leadership to both performance and satisfaction. Previous studies have examined autonomy broadly, but this research operationalizes control as a separate construct that allows employees to structure their remote work environment for optimal performance. This nuanced approach helps explain why some workers thrive in remote work settings while others struggle, emphasizing the importance of both autonomy and perceived control.

Previous research has shown that managers often exhibit “productivity paranoia” in hybrid work environments, doubting workers’ productivity when working remotely. This study provides empirical evidence that perceived autonomy support directly improves performance, alleviating managerial concerns about the effectiveness of telecommuting.

In addition, the research shows that employees who experience greater autonomy also report higher job and life satisfaction, reinforcing the argument that well-being and performance are linked rather than competing goals, empirically explaining and underpinning mutual gains theory.

The options of choice alone, without managerial support, have a less significant impact. This finding is consistent with research that has highlighted that an unsupportive ‘ideal worker’ culture can be a barrier to the uptake of teleworking (Lott and Abendroth, 2020). However, the authors also observed that both control over the work environment and autonomy satisfaction play an important mediating role in the case of autonomy-supportive leadership. Its findings are in line with existing research on leadership styles (e.g., transformational leadership, servant leadership) and their role in promoting employee motivation while extending this knowledge to the field of telework.

Limitations and potential research directions for the future

As with any research, the current study also has some limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. Although the sample was representative based on several aspects, it included only 809 respondents’ self-reports and was exclusively from Hungary. As the results are based solely on respondents’ self-assessment and did not include managerial or organisational perspectives, although the role of autonomy-supportive leadership was found to have a positive impact on performance and life satisfaction, the research did not examine the extent to which respondents’ answers were influenced by the extent to which their leaders supported or hindered their practice. Therefore, the study’s generalisability might be limited. Sampling from other countries could ensure a more comprehensive understanding of the association among the analysed constructs. The sample encompasses respondents aged between 18 and 59 years; however, there is also a population in Hungary that works beyond the age of 59. A broader survey of data would allow further investigation. It could, for example, cover not only age differences but also shed light on the gender context of the issue or industrial differences.

The study collected answers solely from the respondents as they reflected on themselves or the work environment and did not involve other opinions or evidence from managerial or organisational levels. Therefore, the study could analyse only perceived performance and managerial autonomy support by the respondents, which are not the same as performance measured by the organisation or managerial support validated by the managers. Research focusing on individual organisations can analyse performance by considering managerial performance appraisals.

The research did not look at the exact location of telework, although there may be a significant difference in the control over the work environment depending on whether telework occurs at the company client’s premises, in a coworking place, or perhaps at the employee’s home. These telework opportunities could change depending on whether the employee works in the capital or the countryside. Future research could also fill these research gaps.

Although the SDT framework consists of three elements—autonomy, competence, and relatedness - the scholarly discussion on SDT in workplace decisions is primarily concerned with autonomy, and this research continues the contribution along this path. Further research studies can involve the other two elements of basic psychological needs - competence and relatedness—which could further enrich the scientific explanation of this scholarly discourse.

This research studied only the existence of freedom in choosing the workplace. However, future research could extend these results by looking at questions such as what decisional options the employees have, how far in advance they can make these decisions, and how often they can make them. A key factor is asynchronicity, i.e., the freedom for employees to choose their schedules. However, it could not be independent of several factors, such as the company’s industry and profile, the family status of the employee, or the distance between work and home.

Another exciting line of research could be to incorporate elements of the SDT framework into the analysis of different managerial styles and behavioural decisions related to telework.

Managerial implications

The research findings have practical implications for leaders and management. The results of this research can support managers in making strategic and policy decisions about telework.

First, it is worth considering employees’ motivations and preferences when deciding on management style and practices. The results of this research highlight the benefits of leadership that build on these factors and support implementation.

Second, considering the results, a top-down approach to organizational policies on telework is less advantageous than one that takes into account workers’ preferences and allows freedom to choose the work environment to achieve mutual benefits. The results suggest that companies seeking to optimise hybrid work models need to balance autonomy with structured managerial support to increase productivity and well-being. This offers a data-driven response to debates about the effectiveness of hybrid work models in sustaining employee engagement and organisational performance.

Third, if organisational leaders increase their support for employee autonomy, this can improve employee and ultimately organisational performance, which in turn has a positive impact on employee life satisfaction. It is useful to treat teleworking as a positive element in the management toolbox and to take advantage of its benefits. It is, therefore, worth creating the necessary technical conditions, developing supportive management methods, and conducting appropriate performance appraisals.

Finally, the research provides answers for managers who would prefer direct control of employees. This suggests that organisations need to focus not only on telework policies but also on training managers to adopt leadership practices, mindset, and behaviour that support autonomy. Indeed, if both employee performance and well-being are based on trust, and performance can be high even when working remotely, the role of the office working environment can be tailored to the local needs (e.g., the office can be more about building relationships). Such practices can build trust between employees and their managers, further enhance performance, and could also reduce “productivity paranoia”.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Allen AL, Birrell L (2024) Rethinking how we build communities: the future of flexible work. Coll Res Libr 85(3):399–422. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.85.3.399

Allen VL, Greenberger DB (1980) Destruction and perceived control. In: A Baum, JE Singer, JLS (ed.) Adv Environ Psychol, 1st ed.2. Psychology Press, New York, pp. 85–110. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203780800-4

Appelbaum E, Bailey T, Berg P et al. (2000) Manufacturing advantage: why high-performance work systems pay off. First. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Aprilina R, Martdianty F (2023) The role of hybrid-working in improving employees’ satisfaction, perceived productivity, and organizations’ capabilities. J Manaj Teor dan Terap | J Theory Appl Manag 16(2):206–222. https://doi.org/10.20473/jmtt.v16i2.45632

Baard PP, Deci EL, Ryan RM (2004) Intrinsic need satisfaction: a motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. J Appl Soc Psychol 34(10):2045–2068. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1559-1816.2004.TB02690.X

Baja S (2024) Randstad HR trends 2024. Budapest

Bilodeau G, Austin S, Fernet C et al. (2024) Recognition from the immediate supervisor and perceived organizational support in the context of forced telework: the mediating role of psychological need satisfaction’. Psychol du Trav des Organ 30(1):15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PTO.2023.10.003

Bosua R, Kurnia S, Gloet M et al. (2017) Telework impact on productivity and well-being: an Australian study. In: Choudrie, J, Kurnia, S, Tsatsou, P (eds.) Soc. Incl. Usability ICT-Enabled Serv., 1st ed. Routledge, New York, pp. 1–21. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315677316

Bowers DG, Seashore SE (1966) Predicting organizational effectiveness with a four-factor theory of leadership. Adm Sci Q 11(2):238–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391247

Charms R De (1968) Personal causation: The internal affective determinants of behavior. Pers. Causation Intern. Affect. Determ. Behav. First. Academic Press, New York

Chen C, Wang B, An H et al. (2024) Organizational justice perception and employees’ social loafing in the context of the covid-19 epidemic: the mediating role of organizational commitment. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/S41599-024-02612-6

Dan-Cohen M (1992) Conceptions of choice and conceptions of autonomy. Ethics 102(2):221–243. https://doi.org/10.1086/293394

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2000) The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq 11(4):227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci EL, Schwartz AJ, Sheinman L et al. (1981) An instrument to assess adults’ orientations toward control versus autonomy with children: reflections on intrinsic motivation and perceived competence. J Educ Psychol 73(5):642–650. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.73.5.642

Deci EL, Connell JP, Ryan RM (1989) Self-determination in a work organization. J Appl Psychol 74(4):580–590. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.4.580

Deci EL, Ryan RM, Koestner R (1999) A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol Bull 125(6):627–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

Deci EL, Olafsen AH, Ryan RM (2017) Self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 4:19–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

Deci EL, Ryan RM (1985) Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. 1st ed. Springer, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsem RJ et al. (1985) The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 49(1):71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Dijkstra TK, Henseler J (2015) Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q 39(2):297–316. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

Earle HA (2003) Building a workplace of choice: using the work environment to attract and retain top talent. J Facil Manag 2(3):244–257. https://doi.org/10.1108/14725960410808230

Fatima T, Raja U, Malik MAR et al. (2020) Leader–member exchange quality and employees job outcomes: a parallel mediation model. Eurasia Bus Rev 10(2):309–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-020-00158-6

Ficapal-Cusí P, Torrent-Sellens J, Palos-Sanchez P et al. (2024) The telework performance dilemma: exploring the role of trust, social isolation and fatigue. Int J Manpow 45(1):155–168. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-08-2022-0363

Fisher S (1990) Environmental change, control and vulnerability. In: Shirley Fisher, CLC (ed.) Move Psychol Chang Transit, 1st ed. J. Wiley, Michigan, pp 53–65

Gagné M, Deci EL (2005) Self-determination theory and work motivation. J Organ Behav 26(4):331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

Gan J, Zhou ZE, Tang H et al. (2022) What it takes to be an effective “remote leader” during covid-19 crisis: the combined effects of supervisor control and support behaviors. Int J Hum Resour Manag https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.2079953

Gašić D, Berber N (2023) The mediating role of employee engagement in the relationship between flexible work arrangements and turnover intentions among highly educated employees in the Republic of Serbia. Behav Sci 13(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020131

Ghimire B, Dahal RK, Joshi SP et al. (2024) Factors affecting virtual work arrangements and organizational performance: assessed within the context of Nepalese organizations. Intang Cap 20(1):89–102. https://doi.org/10.3926/IC.2513

Gillet N, Fouquereau E, Forest J et al. (2012) The impact of organizational factors on psychological needs and their relations with well-being. J Bus Psychol 27(4):437–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9253-2

Greenberger DB, Strasser S (1986) Development and application of a model of personal control in organizations. Acad Manag Rev 11(1):164–177. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1986.4282657

Greenberger DB, Strasser S, Cummings LL et al. (1989) The impact of personal control on performance and satisfaction. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 43(1):29–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(89)90056-3

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM et al. (2012) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Mark Sci 40(3):414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM et al. (2017) Mirror, mirror on the wall: a comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J Acad Mark Sci 45(5):616–632. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0517-x

Halpern DF (2005) How time-flexible work policies can reduce stress, improve health, and save money. Stress Heal 21(3):157–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1049

Halpin AW, Winer BJ (1957) A factorial study of leader behaviour description. In: Stodgill, RM, Coons, AE (eds.) Lead Behav Descr Meas Bureau of Business Research, Ohio State University, Columbus,

Hellriegel D, Jackson SE, Slocum JW (1999) Management. 8th ed. South-Western College Pub

Hill EJ, Hawkins AJ, Ferris M et al. (2001) Finding an extra day a week: the positive influence of perceived job flexibility on work and family life balance. Fam Relat 50(1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2001.00049.x

Hirsch PB (2023) The hippogryphs on the 14th floor: the future of hybrid work. J Bus Strategy 44(1):50–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-11-2022-0191

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang Y (2024) Work from home (wfh) changes the value of autonomy. Organ Dev J 42(2):91–101

Itam UJ, Warrier U (2024) Future of work from everywhere: a systematic review. Int J Manpow 45(1):12–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-06-2022-0288

Jain S, Devi S, Kumar V (2024) Remote working and its facilitative nuances: visualizing the intellectual structure and setting future research agenda. Manag Res Rev 47(5):689–707. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-01-2022-0057

Jeffrey Hill E, Grzywacz JG, Allen S et al. (2008) Defining and conceptualizing workplace flexibility. Community, Work Fam 11(2):149–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800802024678

Jiang K, Lepak DP, Hu J et al. (2012) How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Acad Manag J 55(6):1264–1294. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0088

Jones MD (2006) Which is a better predictor of job performance: job satisfaction or life satisfaction? J Behav Appl Manag 8(1):20–42. https://doi.org/10.21818/001C.16696

Kanat-Maymon Y, Elimelech M, Roth G (2020) Work motivations as antecedents and outcomes of leadership: integrating self-determination theory and the full range leadership theory. Eur Manag J 38(4):555–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.01.003

Kehoe RR, Wright PM (2013) The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. J Manag 39(2):366–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310365901

KSH (2024) Trends in teleworking employment 2019-2023 (a foglalkoztatottak távmunkavégzésének alakulása 2019-2023). Hungarian Cent Stat Off

Lauring J, Kubovcikova A (2022) Delegating or failing to care: does relationship with the supervisor change how job autonomy affect work outcomes? Eur Manag Rev 19(4):549–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12499

Lee SY, Brand JL (2005) Effects of control over office workspace on perceptions of the work environment and work outcomes. J Environ Psychol 25(3):323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.08.001

Leotti LA, Iyengar SS, Ochsner KN (2010) Born to choose: the origins and value of the need for control. Trends Cogn Sci 14(10):457–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.08.001

Likert R (1961) New Patterns of Management. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York

Lott Y, Abendroth AK (2020) The non-use of telework in an ideal worker culture: why women perceive more cultural barriers. Community Work Fam 23(5):593–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2020.1817726

Marikyan D, Papagiannidis S, Rana OF, Ranjan O (2024) Working in a smart home environment: examining the impact on productivity, well-being and future use intention. Internet Res 34(2):447–473

Martos T, Sallay V, Désfalvi J et al. (2014) Psychometric characteristics of the Hungarian version of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS-H). Ment álhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika 15(3):289–303. https://doi.org/10.1556/mental.15.2014.3.9

Mc LaneyMA, Hurrell JJ (1988) Control, stress, and job satisfaction in Canadian nurses. Work Stress 2(3):217–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678378808259169

Meyer P (2023) Four ways to build a culture of honesty and avoid ‘productivity paranoia. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 64(3):1–3

Microsoft (2022) Hybrid Work Is Just Work. Are We Doing It Wrong? Redmont

Minz NK (2024) Fostering manager-employee relationships in the era of remote work: a literature review. In: Impact Telework. Remote Work Bus. Product. Retention, Adv. Bottom Line IGI Global pp 208–228. https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-1314-5.CH009

Moore BV (1927) The May conference on leadership. Pers J 6(1):5–29

Mustafa G, Solli-Sæther H, Bodolica V et al. (2022) Digitalization trends and organizational structure: bureaucracy, ambidexterity or post-bureaucracy? Eurasia Bus Rev 12(4):671–694. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40821-021-00196-8

Near JP, Smith CA, Rice RW et al. (1984) A comparison of work and nonwork predictors of life satisfaction. Acad Manag J 27(1):184–190. https://doi.org/10.5465/255966

Nitzl C, Roldan JL, Cepeda G (2016) Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modelling, helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Ind Manag Data Syst 116(9):1849–1864. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

Olafsen AH, Deci EL (2020) Self-determination theory and its relation to organizations. In: Oxford Res. Encycl. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.112

Peterson C (1999) Personal control and well-being. In: Kahneman, D, Diener, E, Schwarz, N (eds.) Well-being Found. hedonic Psychol. Russel Sage Foundation p. 288

Pianese T, Errichiello L, da Cunha JV (2023) Organizational control in the context of remote working: a synthesis of empirical findings and a research agenda. Eur Manag Rev 20(2):327–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12515

Pink DH (2011) Drive: the surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books, New York

Racine E, Kusch S, Cascio MA et al. (2021) Making autonomy an instrument: a pragmatist account of contextualized autonomy. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00811-z

Rathi N, Lee K (2017) Understanding the role of supervisor support in retaining employees and enhancing their satisfaction with life. Pers Rev 46(8):1605–1619. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2015-0287

Ravenelle AJ (2019) We’re not uber:” control, autonomy, and entrepreneurship in the gig economy. J Manag Psychol 34(4):269–285. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2018-0256

Reeve J (2015) Giving and summoning autonomy support in hierarchical relationships. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 9(8):406–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12189

Samani SA, Rasid SZA, Sofian S (2015) Perceived level of personal control over the work environment and employee satisfaction and work performance. Perform Improv 54(9):28–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/PFI.21499

Siengthai S, Pila-Ngarm P (2016) The interaction effect of job redesign and job satisfaction on employee performance. Evid Based HRM 4(2):162–180. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-01-2015-0001

Singh B, Kaunert C, Vig K (2024) Enhancing work-life balance in remote working via good health to enhance organizational performance. In: Impact Telework. Remote Work Bus. Product. Retention, Adv. Bottom Line IGI Global pp 1–31.https://doi.org/10.4018/979-8-3693-1314-5.CH001

Skiba T, Wildman JL (2019) Uncertainty reducer, exchange deepener, or self-determination enhancer? Feeling trust versus feeling trusted in supervisor-subordinate relationships. J Bus Psychol 34(2):219–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9537-x

Skinner EA (1996) A guide to constructs of control. J Pers Soc Psychol 71(3):549–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.549

Slemp GR, Kern ML, Patrick KJ et al. (2018) Leader autonomy support in the workplace: a meta-analytic review. Motiv Emot 42(5):706–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-018-9698-y

Smith C, Exton C (2013) OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being. OECD Guidelines Meas Subj Well-being. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264191655-EN

Sutton RI, Kahn RL (1986) Prediction, understanding, and control as antidotes to organizational stress. In: Lorsch, J (ed.) Handb Organ Behav Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, pp 272–285

Tetrick LE, LaRocco JM (1987) Understanding, prediction, and control as moderators of the relationships between perceived stress, satisfaction, and psychological well-being. J Appl Psychol 72(4):538–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.72.4.538

Trougakos JP, Hideg I, Cheng BH et al. (2014) Lunch breaks unpacked: the role of autonomy as a moderator of recovery during lunch. Acad Manag J 57(2):405–421. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.1072

Tsang SS, Liu ZL, Nguyen TVT (2023) Family–work conflict and work-from-home productivity: do work engagement and self-efficacy mediate? Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01929-y

Van De Voorde K, Paauwe J, Van Veldhoven M (2012) Employee well-being and the HRM-organizational performance relationship: a review of quantitative studies. Int J Manag Rev 14(4):391–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00322.x

Williams GC, Grow VM, Freedman ZR et al. (1996) Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. J Pers Soc Psychol 70(1):115–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.115

Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q (2010) Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res 37(2):197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257

Zheng X, Nieberle KW, Braun S et al. (2023) Is someone looking over my shoulder? An investigation into supervisor monitoring variability, subordinates’ daily felt trust, and well-being. J Organ Behav 44(5):818–837. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2699

Acknowledgements

The authors received financial support for the data collection of this research from the Research Fund of Corvinus University of Budapest.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Corvinus University of Budapest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

We also confirm that all authors have approved the manuscript for submission. All authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The execution of the research to examine issues of trust and motivation in hybrid work environment was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Corvinus University of Budapest in line with the Declaration of Helsinki on 14th October 2022. Approval number of the document is KRH/223/2022.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants prior to their inclusion in the study. Consent was collected before November 2022 by NRC Ltd. (www.nrc.hu), the market research company contracted to support participant recruitment and data collection. Participants were recruited via NRC’s research panel (www.netpanel.hu), a database comprising individuals who have voluntarily registered to take part in market and social research. Upon registration, individuals provide consent for the use of their anonymous data in such research contexts and are informed of the data protection policies in place.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

TÓTH, R., DUNAVÖLGYI, M., MITEV, A.Z. et al. Exploring the psychological impact of choice in telework: enhancing employee performance and life satisfaction. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1330 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05449-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05449-9