Abstract

In the face of increasing global pressure for sustainable business practices, the adoption of Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) has emerged as a critical tool for enhancing Environmental Social Governance (ESG) performance. However, there remains a research gap in understanding the specific impact of EMA practices on ESG outcomes, particularly in the context of Bangladesh’s manufacturing sector. This study aims to fill this gap by examining the direct and moderating effects of EMA practices—namely Eco-Efficiency Improvement (EEI), Environmental Cost Tracking (ECT), Life Cycle Assessment Integration (LCAI), and Environmental Reporting Transparency (ERT)—on ESG performance, as well as the role of Carbon Emission Management (CEM) in influencing these relationships. Using a sample of 238 manufacturing firms, the study employs Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) for measurement and structural modeling, along with fsQCA to assess necessity conditions and perform configurational analysis. The findings reveal that EMA practices significantly impact ESG performance, with direct positive effects from EEI, ECT, LCAI, and ERT. CEM also has a direct positive effect on ESG performance and moderates the relationship between EMA practices and ESG outcomes. Additionally, fsQCA analysis identifies synergistic effects of EMA and CEM, revealing configurations that contribute to high ESG performance. The study highlights the importance of integrating EMA practices into corporate strategies for enhancing ESG outcomes. For policymakers, the results provide valuable insights into designing regulations that encourage firms to adopt and strengthen EMA practices, ultimately promoting sustainable business practices. The study suggests that policymakers should focus on creating frameworks that incentivize the adoption of comprehensive EMA strategies and support the integration of CEM, facilitating the transition to more sustainable and responsible business practices within the manufacturing sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’s era of sustainable development, businesses are becoming increasingly aware of the environmental impact of their operations. As a result, there is a growing focus on incorporating sustainable practices into their processes and reporting systems. At the core of these efforts is EMA, a framework designed to improve the management and reporting of environmental costs (Schaltegger et al. 2013). EMA encompasses a range of tools and practices that help organizations track and manage environmental costs and performance effectively. One key practice within EMA is EEI, which emphasizes achieving a balance between economic and environmental efficiency. This approach allows businesses to optimize the use of resources while minimizing waste and environmental harm (Burritt et al. 2009). Another essential component of EMA is ECT, a method for monitoring and managing costs associated with environmental impacts. ECT provides valuable insights that support informed decision-making and the development of sustainable strategies (Christ and Burritt, 2013).

In industries with significant carbon footprints, managing carbon emissions has become a critical priority. As the pressure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions intensifies, companies are allocating substantial resources to develop and implement effective CEM strategies (Qian et al. 2018). Alongside these efforts, LCAI has emerged as a key practice within EMA. LCAI provides businesses with a detailed understanding of the environmental impacts of their products at every stage of their lifecycle, enabling more sustainable decision-making (Latif et al. 2020). Transparency in environmental reporting has also taken center stage. Stakeholders increasingly demand clear and reliable information about a company’s environmental efforts, making ERT a vital aspect of corporate sustainability. Transparent reporting builds trust and ensures accountability for environmental initiatives (Camilleri, 2015; Brooks and Oikonomou, 2018). In addition, the broader framework of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance has become a key benchmark for evaluating a company’s commitment to sustainability. ESG metrics not only include environmental factors tied to EMA but also consider social and governance dimensions, making them critical for investors, stakeholders, and regulators (Lokuwaduge and Heenetigala, 2017). These metrics serve as a comprehensive indicator of a firm’s dedication to sustainable practices and long-term value creation (Ali et al. 2022).

In the quest for sustainable growth, developing countries like Bangladesh must recognize the importance of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance (Shaikh, 2022; Rahman and Islam, 2023). In today’s highly competitive global market, strong ESG performance not only reflects ethical business practices but also provides a competitive edge, particularly for nations striving to strengthen export-driven industries like Bangladesh’s manufacturing sector (Camilleri, 2015). The garment industry, a major contributor to the country’s economy, has faced international criticism over environmental and sustainability issues (Brooks and Oikonomou, 2018). In this context, EMA serves as a vital tool for fostering sustainable practices. By identifying and managing environmental costs, EMA empowers manufacturers to adopt resource-efficient strategies and make informed decisions that balance economic and environmental goals (Jalaludin et al. 2010; Qian et al. 2018). Specific EMA practices, such as EEI and ECT offer potential solutions to address the environmental inefficiencies plaguing the sector. However, their role and impact on ESG performance within Bangladesh’s manufacturing industry remain underexplored (Burritt et al. 2019). Moreover, with the pressing global challenge of climate change, CEM has become particularly critical for a low-lying, climate-vulnerable country like Bangladesh (Rahman and Islam, 2023). Additionally, integrating Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) into manufacturing practices is essential, as it provides a comprehensive understanding of the environmental impacts of products from production to disposal, helping manufacturers align with global sustainability goals (Christine et al. 2019).

This study aims to explore the synergy between EMA and CEM in enhancing Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance, particularly within the context of Bangladesh’s manufacturing sector. The primary research question guiding this investigation is: How do factors of EMA and CEM synergize for ESG performance? The significance of this inquiry stems from the fact that the Bangladeshi manufacturing sector is a major contributor to the country’s economic growth but also a significant source of environmental degradation and carbon emissions. Despite growing global and national pressure to align with sustainability standards, many firms in this sector still lack robust mechanisms for environmental accountability and carbon management. In this regard, EMA offers a systematic approach to identifying and managing environmental costs and improving resource efficiency, while CEM targets the pressing need to monitor and reduce carbon emissions in industrial operations. Addressing these gaps, the study sets out three specific objectives. First, it investigates the effects of key EMA practices—EEI, ECT, LCAI, and ERT—on ESG performance. Second, it examines the direct influence of CEM on ESG outcomes. Third, it explores the moderating role of CEM in the relationship between EMA practices and ESG performance. By focusing on the manufacturing sector in Bangladesh, the study offers timely and context-specific insights into how firms can leverage EMA and CEM to meet sustainability expectations and improve governance accountability.

While the study is contextually grounded in the Bangladeshi garment sector due to its significant environmental footprint and regulatory exposure. As such, although sectoral distinctions may vary, the findings offer transferable insights for other industrial contexts, particularly in developing economies with parallel sustainability imperatives. This is because the EMA practices examined—such as eco-efficiency improvement, life cycle assessment, and environmental cost tracking—are foundational tools for managing environmental performance, regardless of industry type. Similarly, the role of Carbon Emission Management as a moderating force on ESG performance is relevant for any sector subject to environmental regulations or stakeholder pressure for decarbonization. These shared structural and institutional drivers enhance the relevance and applicability of the study’s conclusions beyond the garment industry.

Focusing on Bangladeshi manufacturing firms is critical due to the country’s rapidly growing economy and the significant environmental challenges faced by its manufacturing sector, particularly in industries like textiles and garments. These industries are major contributors to environmental degradation, with issues such as excessive water consumption, high carbon emissions, and inefficient waste management. At the same time, Bangladesh is highly vulnerable to climate change, which intensifies the need for sustainable practices. By examining how EMA and CEM can enhance Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance in these firms, this study addresses both local sustainability challenges and global industry demands. As many Bangladeshi manufacturers are integral to international supply chains, understanding how to align local practices with global sustainability expectations is crucial for improving both environmental outcomes and global competitiveness. Therefore, this research is essential for exploring how EMA and CEM can drive sustainable growth, reduce environmental impacts, and contribute to the broader goal of global sustainability in emerging economies like Bangladesh.

Literature review

Environmental management accounting and sustainability performance

EMA plays a pivotal role in enhancing sustainability practices across various industries by integrating environmental costs, resource efficiency, and eco-efficiency measures into business operations. Asiaei et al. (2022) introduce a natural resource orchestration approach that links green intellectual capital, EMA, and environmental performance, showing how EMA mediates the relationship between intellectual capital and improved environmental outcomes. Qian et al. (2018) examine EMA’s effects on carbon management and disclosure quality, finding a positive impact on both areas. Latif et al. (2020) highlight the role of coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures in driving the adoption of EMA within Pakistan’s manufacturing sector. In Malaysia, Mohd Khalid et al. (2012) reveal that EMA implementation in environmentally sensitive industries is influenced by both cost-conscious motivations and customer pressures. Ferreira et al. (2010) establish a favorable association between EMA and process innovation in large Australian businesses, emphasizing EMA’s role in fostering innovation while improving environmental performance. Collectively, these studies underscore EMA’s critical function in orchestrating environmental performance, bridging intellectual capital, and driving innovation within sustainability practices.

In a series of studies examining the influence of sustainability performance, that is, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) disclosures on firm value, Zaneta (2021) found a negative impact of environmental and social disclosures on firms in the Indonesian manufacturing and mining sectors. This result was echoed in a subsequent study by Zaneta et al. (2023). Meanwhile, Ali et al. (2022) demonstrated a positive effect of environmental management practices on both environmental performance and financial outcomes in Malaysian firms, with ESG disclosure mediating this relationship. Kumar and Firoz (2022) explored the Indian context, establishing a positive relationship between comprehensive ESG disclosure and Corporate Financial Performance, though the social aspect was an exception. Lastly, Maama (2021) examined banks in West Africa, revealing that a country’s political environment significantly influences ESG accounting practices, while the economy’s size was deemed less relevant.

Brooks and Oikonomou (2018) reviewed the extensive literature on ESG disclosures, highlighting fresh perspectives and identifying gaps in understanding the effects of these disclosures on firm value, while introducing a special issue of the British Accounting Review. Deb et al. (2022) focused on Bangladesh’s manufacturing sector, finding a positive link between EMA and both environmental and financial performance, emphasizing the role of stakeholders and institutions in promoting EMA. Camilleri (2015) discussed the European Union’s regulations on ESG disclosures, revealing a mix of voluntary and mandatory measures among member states and stressing the need for further empirical research. Aziz and Chariri (2023) studied Indonesian non-financial companies and found that while environmental performance boosted stock returns, ESG disclosures had an insignificant adverse impact. Fithriyana et al. (2022) conducted a systematic literature review discussing the relationship between ESG and financial performance, grounded in stakeholder and agency theories.

Shaikh (2022) quantitatively examined firms’ sustainability reporting, noting that European companies exhibit more ESG compliance, with differences observed in accounting and market-based performance metrics. Lokuwaduge and Heenetigala (2017) focused on the ESG reporting of Australian metal and mining sector companies, suggesting that stakeholder engagement is vital for sustainable development and that there’s a need for an ESG disclosure index. Burritt et al. (2019) explored the diffusion of environmental management accounting in Asian countries, emphasizing the value of external support and interdisciplinary approaches. Christine et al. (2019) analyzed the relationship between environmental management accounting, environmental strategies, and managerial commitment in Indonesian SMEs, discovering that these factors significantly impact environmental and economic performance. Lastly, Fuzi et al. (2019) evaluated the relationship between environmental management accounting practices, environmental management systems, and environmental performance in the Malaysian manufacturing sector, underscoring the strategic importance of such accounting practices in improving environmental outcomes.

Despite a growing body of literature on Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance, a comprehensive synthesis of their interrelationship remains underdeveloped. Much of the extant scholarship has approached EMA and ESG as distinct theoretical and operational domains. For instance, studies such as Camilleri (2015) and Shaikh (2022) have emphasized the strategic dimensions of ESG integration or the managerial utility of EMA, but have rarely explored how these two constructs interact to influence sustainable performance outcomes in an integrated manner. Although Burritt and colleagues (Burritt and Saka, 2006; Burritt et al. 2019) have provided seminal contributions through case-based analyses on the role of EMA in promoting cleaner production, these studies largely stop short of empirically linking EMA implementation to ESG metrics in a structured and measurable way. Moreover, existing research has been heavily concentrated in advanced industrialized contexts, where regulatory frameworks, institutional capacities, and resource availability significantly differ from those in developing countries. This creates a contextual void in understanding how EMA practices function within the institutional and operational constraints of emerging economies. Bangladesh, and particularly its garment manufacturing sector, presents a pertinent case for addressing this gap. As one of the world’s largest textile exporters, the sector grapples with acute sustainability challenges—ranging from hazardous waste discharge and high water consumption to escalating carbon emissions. However, despite these environmental burdens, the sector has received limited empirical attention regarding the effectiveness of EMA practices in improving ESG performance. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are developed to guide the empirical investigation.

H1: Sustainability performance is positively influenced by EMA through eco-efficiency improvement.

H2. Sustainability performance is positively influenced by EMA through environmental cost tracking.

H3. Sustainability performance is positively influenced by EMA through life cycle assessment integration.

H4. Sustainability performance is positively influenced by EMA through environmental reporting transparency.

Carbon emission management and sustainability performance

Recent research on carbon emissions and sustainability performance (ESG) has highlighted the critical role of environmental management and disclosure practices in driving business sustainability. Almeyda and Darmansya (2019) demonstrated a positive correlation between ESG disclosures and financial outcomes, such as Return on Assets (ROA) and Return on Capital (ROC), particularly within G7 real estate firms, where carbon reduction initiatives play a significant role. Ng et al. (2020) emphasized the role of financial development in Asia, asserting its positive influence on ESG performance, including carbon emission reductions across rapidly industrializing economies. Cicchiello et al. (2023) analyzed the impact of the European Non-Financial Reporting Directive, which has significantly enhanced carbon accountability and ESG commitment among EU firms compared to their US counterparts. Meanwhile, Burritt and Saka (2006) and Burritt et al. (2009) explored the role of EMA in facilitating carbon emission reductions and promoting cleaner production practices, as evidenced by case studies from Japan and the Philippines. Christ and Burritt (2013) further emphasized the importance of EMA in reducing carbon footprints, noting that factors such as environmental strategies, organizational size, and industry type strongly influence its adoption within Australian businesses.

Zaneta et al. (2023) investigated the relationship between ESG disclosures, green product innovation, and EMA in driving firm value, highlighting the strategic significance of integrating ESG and EMA practices. Ali, Salman, and Parveen (2022), along with Kumar and Firoz (2022), explored the mediating role of ESG disclosures in linking environmental management practices with improved financial performance, underscoring the transformative potential of ESG transparency. Similarly, Maama (2021) emphasized the critical interplay between institutional environments and ESG accounting practices, focusing on banks in West Africa. Brooks and Oikonomou (2018) provided a comprehensive review of ESG disclosures and their impact on firm value, paving the way for further empirical exploration. In the context of Bangladesh, Deb, Rahman, and Rahman (2022) highlighted the pivotal role of EMA in enhancing environmental and financial outcomes, drawing attention to its potential in emerging markets. Other studies, such as those by Jalaludin et al. (2010) and Fuzi et al. (2019), emphasized EMA’s role in fostering environmental performance. Additionally, research by Aziz and Chariri (2023) and Fithriyana et al. (2022) revealed ESG’s significant influence on financial performance and stock returns, further solidifying its importance in modern corporate strategies.

While previous studies have acknowledged the importance of ESG disclosures in enhancing both financial and environmental outcomes (Ali et al., 2022; Kumar and Firoz, 2022), they have largely concentrated on broad sustainability reporting and environmental practices, rather than on the targeted role of carbon-specific strategies. Research by Deb et al. (2022) and Fuzi et al. (2019) has examined the broader implications of environmental management systems, yet these studies seldom isolate carbon emission initiatives as distinct drivers of sustainability performance. Burritt and Saka (2006), along with Christ and Burritt (2013), underscored the significance of environmental accounting in fostering eco-efficiency, but did not specifically evaluate CEM within ESG frameworks. This lack of granularity creates a significant knowledge gap—particularly in developing economies like Bangladesh—where high-emission sectors such as manufacturing and textiles are both environmentally impactful and economically vital. Given that carbon emissions are a core environmental challenge in these sectors, overlooking the direct role of CEM limits the strategic guidance available for improving ESG outcomes. Therefore, this study aims to advance the literature by empirically examining how CEM contributes specifically to sustainability performance in the manufacturing context. To that end, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5. Carbon emission management positively affects sustainability performance.

Moderating effect of carbon emission management

Linnenluecke (2022) highlights the complexities of applying ESG frameworks across diverse contexts, emphasizing the importance of incorporating local stakeholder perspectives, particularly for multinational enterprises (MNEs) and emerging market multinationals (EMNEs). Gillan et al. (2010) suggest that stronger ESG initiatives can enhance firms’ operating performance and value, showcasing the potential of ESG policies in driving sustainability outcomes. Huang (2021) reviews the broader motivations behind ESG engagement, revealing its impact extends beyond financial performance. Harjoto and Wang (2020) find that board network centrality positively influences ESG performance, particularly in sectors characterized by high product market concentration. Mooneeapen et al. (2022) examine governance factors like democracy, political stability, and regulatory quality, demonstrating their significant influence on corporate ESG performance. Shaikh (2022) underscores the role of non-financial voluntary disclosures in linking ESG practices to firm performance. Lokuwaduge and Heenetigala (2017) and Almeyda and Darmansya (2019) emphasize the role of ESG reporting and disclosure in advancing sustainable development and improving financial performance. Ng et al. (2020) identify a positive relationship between financial development and ESG success in Asia, while Cicchiello et al. (2023) demonstrate how non-financial disclosure regulations in Europe enhance ESG performance through improved disclosure commitment and effectiveness. Despite these advancements, the moderating role of CEM within the ESG framework remains underexplored. CEM may amplify the effectiveness of ESG practices by addressing environmental impacts more directly, thereby strengthening the relationship between ESG initiatives and sustainability performance.

Studies across regions and industries highlight the diverse impacts of EMA on sustainability practices. Qian, Burritt, and Monroe (2011) examined the role of EMA in waste management within local government entities in New South Wales, Australia, identifying social structural influences and organizational dynamics as key drivers in the increasing use of EMA information. Burritt and Saka (2006) investigated the link between EMA and eco-efficiency in Japan, emphasizing the untapped potential of integrating eco-efficiency measurements with EMA data. Burritt, Herzig, and Tadeo (2009) analyzed EMA’s influence on environmental investment decisions within a Philippine rice mill, offering valuable insights for corporate and policy-level decision-making. Christ and Burritt (2013), applying a contingency theory perspective, explored EMA adoption in Australian organizations, linking it to environmental strategy, organizational size, and industry sensitivity.

Further research by Burritt et al. (2019) examined the diffusion of EMA innovations through case studies in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, revealing diverse approaches to EMA adoption in Southeast Asia. Christine et al. (2019) explored how EMA, combined with environmental strategy and managerial commitment, impacts both environmental and economic performance in Indonesian SMEs. Fuzi et al. (2019) studied the integration of EMA with environmental management systems in Malaysia’s manufacturing sector, highlighting its positive effects on environmental performance. Similarly, Jalaludin et al. (2010) found a strong link between EMA, environmental performance, and economic performance in Malaysian manufacturing firms. Ahmad et al. (2018) examined the relationship between environmental accounting and corporate performance in Pakistan’s non-financial firms, while Solovida and Latan (2017) analyzed the role of environmental management systems and green reporting in driving sustainability in Indonesian businesses. In Bangladesh, Rahman and Islam (2023) investigated the role of energy efficiency in improving environmental outcomes in the pharmaceutical and chemical sectors. Rahman and Rahman (2020) highlighted the significance of green reporting in optimizing resource utilization and reducing pollution.

Although a growing body of research has explored the relationship between EMA and sustainability performance, the potential moderating influence of CEM within this nexus has been largely overlooked. Foundational studies by Burritt and Saka (2006) and Burritt et al. (2009) primarily focus on how EMA supports eco-efficiency and guides environmental investment, yet they do not investigate whether or how CEM might strengthen or weaken these effects. Similarly, while Christine et al. (2019) and Fuzi et al. (2019) demonstrate that EMA can improve both environmental and economic outcomes, their analyses remain limited to direct effects and do not examine CEM as a contextual factor influencing these outcomes. More recent contributions, such as Jalaludin et al. (2010) and Ahmad et al. (2018), reiterate the effectiveness of EMA in environmental performance enhancement, but they treat CEM either superficially or not at all. This omission is particularly salient in the context of emerging economies like Bangladesh, where manufacturing sectors contribute significantly to carbon emissions and where regulatory frameworks around carbon management are still developing. Unlike prior research that treats EMA in isolation, the current study offers a more integrated perspective by considering how CEM can act as a moderating mechanism—potentially enhancing or constraining the effectiveness of EMA in achieving sustainability outcomes. Addressing this gap is crucial for understanding how organizations can align environmental accounting practices with carbon mitigation strategies to meet global ESG expectations. Therefore, the study proposes the following hypothesis:

H6. Carbon emission management moderates the relationship between EMA and sustainability performance.

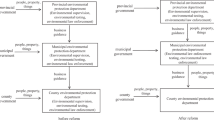

Based on the existing studies, the study developed the following Fig. 1 as a conceptual framework.

Methodology

Data and sample

The research adopted a quantitative design, which emphasizes objective measurements and numerical analysis of data. This design was chosen as it provides a systematic and empirical investigation into the relationships between EMA practices and the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance of manufacturing firms (Garments exporters) in Bangladesh. The quantitative nature of the study ensures that the results are based on numerical data, which can be statistically tested to draw definitive conclusions. For this study, primary data was collected using structured questionnaires. These were designed after a comprehensive literature review and consisted of questions that revolved around the adoption and impacts of EMA practices on ESG performance. The questions were close-ended, allowing respondents to select from a range of predetermined answers. This format ensured the ease of data analysis, given the quantitative nature of the research.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, a comprehensive pre-testing and piloting process was conducted. Initially, the questionnaire was pre-tested with a group of five experts in the fields of EMA and ESG performance to evaluate the clarity, relevance, and comprehensiveness of the questions. Feedback from the pre-testing phase was used to refine the questionnaire, ensuring that the language was clear and the questions were aligned with the research objectives. Subsequently, a pilot study was conducted with 20 garment firms that were not part of the main sample. This pilot testing phase aimed to identify any potential issues with the questionnaire structure, question interpretation, or response options. Responses from the pilot study were analyzed to assess the reliability of the survey instrument using Cronbach’s alpha, which demonstrated a satisfactory level of internal consistency ( > 0.7). Based on the results of the pilot study, minor adjustments were made to the questionnaire before final deployment.

The research employed a simple random sampling technique to ensure that every eligible participant had an equal probability of selection, thereby reducing selection bias and enhancing the credibility and generalizability of the results. The initial sampling frame was derived from the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), focusing on the top 10 garment exporters in 2021—firms recognized for their leadership in the country’s export-driven manufacturing sector. Fifteen questionnaires were distributed to each of these firms, resulting in 150 responses collected between July and September 2023. After excluding 32 incomplete and 18 blank questionnaires, 100 valid responses were retained for the first stage of analysis.

To broaden the representativeness of the findings and account for potential heterogeneity within the garment sector, a second round of data collection was conducted. This stage targeted an additional 50 garment firms of varying sizes—including mid-sized and smaller enterprises not featured in the top 10—selected through simple random sampling from the broader BGMEA registry. Three questionnaires were sent to each firm, yielding 150 additional responses between November 10 and December 15, 2024. After data cleaning, 138 valid responses were retained, bringing the total number of usable responses to 238. This two-stage approach allowed for a more comprehensive coverage of the garment sector, improving the generalizability of the study’s conclusions beyond the top-tier exporters.

The decision to focus on garment manufacturers is grounded in the industry’s critical role in Bangladesh’s economy, where it accounts for more than 80% of total export earnings and remains one of the largest sources of industrial employment. Furthermore, the sector is highly relevant to the study’s objectives, as it is a major contributor to environmental challenges such as carbon emissions, water pollution, and resource inefficiency—issues directly linked to EMA and CEM practices. By including both large exporters and smaller firms, the study captures a broad spectrum of operational practices and environmental strategies. However, the industry-specific focus may limit the direct applicability of the findings to other sectors with different environmental profiles or regulatory pressures. This limitation is acknowledged, but the insights derived from the garment industry—due to its size, visibility, and environmental footprint—offer valuable implications for the wider manufacturing sector in Bangladesh.

Operationalization of the constructs

The constructs for this study are operationalized using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree. The first construct, EEI, is measured using five indicators adapted from Qian et al. (2018). These indicators assess an organization’s commitment to enhancing resource efficiency, improving energy use, reducing its environmental footprint, integrating waste reduction initiatives, and promoting sustainable resource utilization. Similarly, ECT, based on Kuzey and Uyar (2017), includes indicators that evaluate the organization’s ability to track and allocate environmental costs, maintain a system for recording and reporting these costs, allocate financial resources for environmental initiatives, and consider environmental costs in decision-making processes.

The construct of CEM is measured using indicators from Khan (2019). These assess the organization’s efforts to monitor and manage carbon emissions, establish carbon reduction goals, focus on reducing emissions, mitigate climate change impacts, and align initiatives with industry standards. LCAI, drawn from Adediran and Alade (2013), evaluates the extent to which organizations conduct comprehensive assessments of environmental impacts across product lifecycles, integrate environmental considerations into product development stages, and use lifecycle assessments to identify sustainable improvement opportunities. Additionally, ERT, adapted from Qian et al. (2018), is assessed through indicators that measure the accessibility, accuracy, and transparency of environmental performance reporting, as well as the organization’s commitment to sharing progress and challenges with stakeholders.

Finally, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance is operationalized using indicators from Xue et al. (2023) and Zheng et al. (2021). These focus on the organization’s commitment to environmental sustainability, the positive impact of its social initiatives, transparency and ethics in governance practices, alignment with industry-leading ESG standards, and the overall contribution of ESG efforts to organizational success.

Data analysis procedures

The use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) is well-suited for this study due to their ability to address complex relationships and capture synergistic effects. PLS-SEM is particularly appropriate as it can handle small sample sizes and analyze relationships between latent constructs with multiple indicators. This method is also ideal for predictive modeling and theory development, as it focuses on maximizing the explained variance of dependent variables. Furthermore, PLS-SEM is robust in addressing non-normal data distributions, which is often the case in behavioral and sustainability studies. By using PLS-SEM, this study can effectively test both direct and moderating relationships, such as the moderating effect of CEM on the link between EMA and sustainability performance.

In contrast, fsQCA complements PLS-SEM by offering a configurational perspective that identifies causal conditions leading to a specific outcome. Unlike conventional variable-centered methods, fsQCA allows for the exploration of multiple pathways to an outcome, acknowledging the potential for equifinality where different combinations of variables may lead to similar results. This is particularly relevant in sustainability studies, where diverse organizational strategies and contexts interact in complex ways. FsQCA also incorporates both qualitative and quantitative data, making it suitable for exploring heterogeneity in the dataset. By combining PLS-SEM with fsQCA, this study leverages the strengths of both methods, providing a holistic understanding of the relationships between EMA, CEM, and sustainability performance.

Analysis and findings

Demographic profile analysis

The demographic profile analysis (n = 238) reveals a balanced gender distribution, with 54% male and 46% female respondents. In terms of age, the majority of participants fall within the 26–30 age group (29%), followed by 18–25 (19%), 38–44 (19%), and 45–50 (15%), while only 12% and 6% belong to the 31–37 and above 50 age groups, respectively. Regarding professional roles, the largest groups include Senior Officers (29%) and Managers (28%), followed by Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) (16%), Management Accountants (15%), and Finance Controllers (12%). In terms of professional experience, the majority of respondents have 11–20 years of experience (37%), followed by those with 5–10 years (30%), below 5 years (19%), and above 20 years (14%). This diverse demographic profile in Fig. 2 ensures a wide range of perspectives and experiences, contributing to the robustness of the study’s findings.

Analysis of PLS-SEM

Measurement model analysis

Table 1 presents the measurement model summary, which evaluates the reliability and validity of the constructs used in the study. The table includes outer loadings, Cronbach’s Alpha (CA), Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each variable and its associated indicators. The outer loadings for all indicators are above the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating that the indicators strongly represent their respective constructs. For example, in the case of EEI, all five indicators have loadings between 0.740 and 0.810, demonstrating their adequacy in explaining the construct. Similarly, the other variables, including ECT, CEM, LCAI, ERT, and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG), also have indicator loadings exceeding the acceptable threshold.

The CA values for all variables range from 0.800 to 0.920, reflecting internal consistency among the indicators for each construct. This is further supported by the Composite Reliability (CR) values, which are above 0.870 for all variables, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70, ensuring that the constructs are reliable. Lastly, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values, which measure the amount of variance captured by the construct relative to measurement error, are above 0.50 for all variables, confirming convergent validity. For instance, ERT has an AVE of 0.750, indicating that 75% of the variance in this construct is explained by its indicators. The VIF values are less than 3, indicating the absence of a multicollinearity issue.

Table 2 showcases the results of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, essential prerequisites for factor analysis. The KMO value of 0.912, substantially above the acceptable threshold of 0.60, suggests excellent sampling adequacy, confirming that the dataset is well-suited for factor analysis. Concurrently, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, with an Approximate Chi-Square value of 4928.008 and a significance level of 0.000 (well below the 0.05 threshold), indicates that the observed variables are interrelated and not independent. Therefore, both metrics solidly endorse the appropriateness of this dataset for factor analysis.

In this study, the assessment of discriminant validity emerged as a critical component in evaluating the distinctiveness of our constructs, ensuring that each variable measures a unique underlying concept. To achieve this, we employed the heterotrait–monotrait correlation ratio (HTMT) criterion, a well-established method for estimating discriminant validity. The HTMT values, ranging from 0 to 1, were meticulously scrutinized and compared against a predefined threshold of 0.90, as prescribed by Hair et al. (2019). This threshold serves as a litmus test, where values approaching 1 indicate a potential lack of distinction between constructs. The results of our analysis unveiled that our measurement model indeed exhibited significant discriminant validity, with the maximum HTMT score reaching 0.960. These findings robustly support the distinctiveness of the constructs under investigation, as meticulously presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Cross-loading, which refers to the extent to which an item in a measurement instrument loads on constructs other than its intended one, was scrutinized closely in our analysis. As elucidated in Sarstedt et al. (2022), our findings unequivocally demonstrate that there are no discernible issues with discriminant validity. This underscores the precision and effectiveness of our measurement instruments in accurately capturing the unique essence of each construct. In essence, our study’s meticulous attention to discriminant validity, as demonstrated by the HTMT criterion and confirmed through cross-loading analysis, lends further credibility to the distinctiveness and reliability of our measurement model.

Structural model analysis

Table 5 presents the results from a regression analysis focused on the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance as the dependent variable. The R-square (R^2) value of 0.829 indicates that approximately 82.9% of the variance in ESG performance can be explained by the independent variables included in the model. This suggests that the model has a reasonably strong predictive capability. However, considering the potential for overfitting, Table 5 also provides the R-square adjusted value, which takes into account the number of predictors in the model. With an adjusted R^2 value of 0.825, or 82.5%, the model remains robust, indicating only a slight decrease when adjusting for the number of predictors. This means that even after accounting for the complexity of the model, a significant proportion of the variation in ESG performance is explained by the model’s variables.

Table 6 Model Fit presents the key metrics to evaluate the fit of the estimated model. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value of 0.082 is below the acceptable threshold of 0.10, indicating a good fit between the hypothesized model and the observed data. The d_ULS (Unweighted Least Squares) value of 3.092 and d_G (Geodesic Distance) value of 2.802 further support the adequacy of the model fit. The Chi-square value of 2920.755, while dependent on sample size, aligns with an acceptable fit when considered with other metrics. Finally, the Normed Fit Index (NFI) of 0.623, which is close to the ideal value of 1, demonstrates an excellent model fit. Based on these results, the estimated model is well-fitted and can be considered robust for further analysis.

The structural equation modeling analysis reveals a mixed impact of Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) factors on Sustainability Performance (see Fig. 3). Among the four EMA dimensions, Environmental Cost Tracking (ECT) demonstrates the most substantial positive influence on sustainability performance, with a coefficient of 0.411 and a T-statistic of 4.483 (p = 0.000), thereby supporting H2. This result underscores the vital role of systematically monitoring and allocating environmental costs in enhancing sustainability outcomes. Life Cycle Assessment Integration (LCAI) also shows a significant positive effect on sustainability performance, with a coefficient of 0.196, a T-statistic of 2.395, and a p-value of 0.009, thus supporting H3. This suggests that embedding environmental considerations throughout the product lifecycle contributes meaningfully to sustainable development efforts.

The impact of Eco-Efficiency Improvement (EEI) on sustainability performance is positive yet relatively modest, with a coefficient of 0.128, a T-statistic of 1.864, and a p-value of 0.031. Despite its lower magnitude, the relationship is statistically significant, thereby supporting H1 and indicating that improvements in resource efficiency still play a noteworthy role in promoting sustainability. In contrast, Environmental Reporting Transparency (ERT) does not exhibit a significant impact on sustainability performance. With a coefficient of 0.012, a T-statistic of 0.156, and a p-value of 0.438, the hypothesis (H4) is not supported, suggesting that transparent environmental reporting alone may be insufficient to drive sustainability outcomes unless paired with more actionable initiatives. These findings provide nuanced insights into the effectiveness of different EMA strategies. They indicate that while certain practices like ECT and LCAI are strongly associated with better sustainability performance, others, such as ERT, may require complementary mechanisms—such as stakeholder engagement or regulatory support—to yield tangible results.

The path coefficient of β = 0.220 for CEM indicates a strong and meaningful impact on sustainability performance, suggesting that firms with robust carbon management practices are significantly better positioned to achieve superior ESG outcomes (see Table 7). For managers, this underscores the strategic value of integrating carbon reduction initiatives—such as emissions tracking, cleaner production technologies, and reporting mechanisms—into core operational processes. This finding aligns with resource-based and institutional theories, which emphasize that proactive environmental capabilities not only enhance compliance but also build reputational capital and competitive advantage, particularly in environmentally sensitive sectors like garment manufacturing.

Analysis of fsQCA

The fsQCA analysis in this study unfolds in three sequential steps. The first step involves calibration, where latent scores derived from the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) serve as input for fsQCA. This calibration ensures that the quantitative insights obtained from PLS-SEM are translated into fuzzy set values suitable for the subsequent qualitative comparative analysis.

The second step of the analysis delves into the identification of necessary conditions for achieving high Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance, employing fsQCA methodology. The results of this analysis are detailed in Table 8, providing insight into the consistency and coverage values for each identified condition. Following Ragins (2006) criteria, a consistency value of 90% or above indicates the presence of necessary conditions for high ESG performance.

The results highlight the significance of Carbon Emission Management, Environmental Cost Tracking, and Environmental Reporting Transparency as necessary conditions for achieving high ESG performance. First, Carbon Emission Management emerges as a critical factor, as reflected by its high consistency value of 0.922 and coverage of 0.906. These values exceed the 90% threshold for both consistency and coverage, indicating a strong and consistent link between managing carbon emissions and attaining superior ESG outcomes. This emphasizes the importance of carbon management strategies in firms’ efforts to enhance their ESG performance, as they directly contribute to reducing environmental impacts and aligning with global sustainability goals.

Similarly, Environmental Cost Tracking proves to be another essential condition for high ESG performance. With a consistency value of 0.915 and coverage of 0.914, it demonstrates a significant relationship between effective tracking and management of environmental costs and favorable ESG outcomes. This suggests that firms focusing on accurately monitoring and managing their environmental expenditures are more likely to achieve high ESG scores, reinforcing the need for systematic cost tracking in sustainability practices. Finally, Environmental Reporting Transparency is also highlighted as a necessary condition for high ESG performance, with a consistency value of 0.901 and coverage of 0.899. These values reinforce the vital role of transparent environmental reporting in facilitating high ESG performance. Organizations that emphasize clarity and comprehensiveness in communicating their environmental actions and outcomes tend to perform better in ESG assessments, meeting the expectations of investors, regulators, and other stakeholders who prioritize transparency.

Table 9 presents the results of a configuration analysis aimed at identifying combinations of factors that contribute to high ESG performance. The analysis used the Quine-McCluskey algorithm and includes eight potential solutions (S1 to S8), each representing a different configuration of conditions required to achieve high ESG performance. The conditions considered in the analysis include CEM, ECT, EEI, ERT, and LCAI. The presence or absence of each condition in a solution is marked by a black circle (“●”) for presence and a white circle (“○”) for absence, with blank cells indicating that the condition does not affect the solution.

The raw coverage values indicate the proportion of high ESG performance cases explained by each solution. Solutions like S1 (with a raw coverage of 0.837) cover a significant portion of high ESG performance cases, suggesting that these combinations of factors are highly relevant in explaining ESG outcomes. The unique coverage values are generally low, meaning that most of the high ESG performance cases are explained by more than one solution. For example, S1 has a unique coverage of 0.021, indicating that only a small portion of the high ESG performance cases is exclusively explained by this solution.

Consistency values reflect the reliability of each solution in leading to high ESG performance, with higher values indicating stronger reliability. Solutions such as S1 (with a consistency of 0.965) show very high consistency, meaning they consistently lead to high ESG performance. The overall solution coverage is 0.925, meaning that the solutions together explain 92.5% of the high ESG performance cases, while the overall solution consistency is 0.932, indicating that the solutions are highly reliable in predicting high ESG performance.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that all four EMA practices—EEI, ECT, LCAI, and ERT—positively and significantly influence sustainability (ESG) performance in the Bangladeshi manufacturing sector. Among them, ECT and LCAI appear to exert particularly strong effects. ECT enables firms to better understand and internalize the financial consequences of their environmental activities, which is especially valuable in Bangladesh, where environmental costs are often overlooked in decision-making. LCAI, with its comprehensive assessment of environmental impact across the product life cycle, helps firms identify sustainability opportunities at every production stage, a critical need in a resource-intensive industrial environment. ERT also plays a significant role by fostering transparency, which enhances stakeholder trust and aligns firms with international sustainability expectations, crucial for export-oriented sectors.

CEM also shows a significant positive effect on ESG performance, highlighting its critical role in the sustainability strategies of manufacturing firms. In Bangladesh’s rapidly industrializing economy, where carbon emissions are a mounting concern, CEM offers firms an avenue to not only comply with international environmental standards but also reduce operational inefficiencies and improve reputational standing. The findings suggest that firms that actively measure, manage, and reduce their emissions tend to perform better in ESG evaluations. This is likely due to the growing pressure from global markets and stakeholders for transparent and verifiable climate action, which positions CEM as both an environmental and strategic business imperative.

Importantly, the study finds that CEM moderates the relationship between EMA practices and ESG performance, amplifying their impact. This suggests that the presence of strong CEM practices strengthens the effectiveness of EEI, ECT, LCAI, and ERT by integrating emissions management into broader environmental strategies. For instance, firms that track emissions closely are more likely to derive greater benefits from efficiency improvements and life cycle assessments, as these practices contribute directly to measurable emissions reductions. The fsQCA results further confirm that high ESG performance is most often achieved when CEM is combined with multiple EMA practices, emphasizing the value of a synergistic and holistic environmental management approach. For the Bangladeshi manufacturing sector, this integrated strategy offers a pathway to enhanced sustainability performance while meeting global environmental and economic expectations.

The varying influence of individual EMA practices and CEM on ESG performance can be explained through both theoretical and practical frameworks. The Resource-Based View (RBV) of the firm posits that internal capabilities, such as effective cost tracking (ECT) and life cycle assessment (LCAI), provide sustainable competitive advantages when they are valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate (Barney, 1991). These capabilities help firms optimize resource use, reduce waste, and manage risks more effectively, directly contributing to superior ESG outcomes. Industry evidence supports these claims; for instance, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO, 2021) reported that Bangladeshi firms participating in environmental cost management initiatives achieved up to 20% reductions in production waste and enhanced cost efficiency. Similarly, the World Bank (2022) emphasized the growing pressure on suppliers in global value chains to provide life cycle impact data, making LCAI essential not only for sustainability but also for continued market access. In contrast, while EEI and ERT are essential components of EMA, their influence may be less pronounced if they are implemented in isolation or without strategic integration. ERT’s effectiveness, for example, often hinges on the credibility of disclosures and stakeholder responsiveness, which are still evolving in many Bangladeshi firms. Hence, the stronger effects observed for ECT, LCAI, and CEM likely stem from their deeper operational integration and alignment with both international sustainability demands and firm-level strategic goals.

The finding that CEM amplifies the effect of EMA on ESG performance aligns with and extends prior studies emphasizing the strategic integration of environmental management practices in sustainability performance outcomes. For instance, Ali et al. (2022) and Deb et al. (2022) demonstrated that the adoption of EMA positively influences both environmental and financial performance, especially when paired with transparent ESG disclosures. Burritt et al. (2019) and Christ and Burritt (2013) further supported the notion that EMA adoption is context-sensitive and most effective when integrated with environmental strategies and regulatory pressures—conditions often embedded within CEM frameworks. CEM provides structured emissions reduction targets, carbon accounting metrics, and compliance mechanisms that complement EMA tools, thereby institutionalizing environmental data into broader ESG reporting and strategy (Qian et al. 2018; Asiaei et al. 2022). This synergy enhances firms’ capabilities to not only track but act on environmental externalities, resulting in more robust ESG outcomes (Husted and de Sousa-Filho, 2017; Harjoto and Wang, 2020). Compared to prior studies that examine EMA or ESG performance in isolation, our research contributes by empirically validating the moderating effect of CEM as a mechanism that aligns EMA practices with strategic sustainability goals, improving both process efficiency and ESG transparency (Camilleri, 2015; Lee et al. 2016).

Conclusions, implications, and limitations

This study provides empirically grounded evidence on the critical role of EMA practices and CEM in enhancing sustainability (ESG) performance within the Bangladeshi manufacturing sector. The results from the PLS-SEM analysis reveal that all four EMA dimensions—EEI, ECT, LCAI, and ERT—exert statistically significant positive effects on ESG performance. This supports existing literature emphasizing the importance of proactive environmental accounting in achieving sustainable business outcomes (Qian et al. 2011). Additionally, CEM was found to have a strong direct positive impact on ESG performance, aligning with studies that highlight carbon management as a critical driver of corporate environmental responsibility.

Importantly, the interaction analysis revealed that CEM significantly moderates the relationship between EMA practices and ESG performance, suggesting that firms adopting both strategies experience amplified sustainability benefits. This finding underscores the synergistic relationship between carbon-focused and accounting-based environmental practices. Moreover, the fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) demonstrated that high ESG performance is not driven by isolated factors, but rather by specific configurations—particularly the co-presence of strong EMA practices and effective CEM. This configurational insight supports the notion of equifinality in sustainability performance.

Practical implications

The findings of this study provide some actionable insights for policymakers aiming to enhance environmental sustainability in Bangladesh’s manufacturing sector. Firstly, there is a need to financially incentivize the adoption of EMA practices. Policymakers can introduce tax benefits, subsidies, or low-interest green loans for firms that implement eco-efficiency improvements (EEI), ECT, LCAI, and ERT. Secondly, mandatory environmental reporting standards should be introduced to institutionalize accountability and transparency. Regulatory bodies can require manufacturing firms to submit annual ESG disclosures that align with global sustainability frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) or the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). Such mandates would not only ensure consistent data for monitoring but also drive improvements in environmental practices.

Thirdly, considering the moderating role of CEM in enhancing the effectiveness of EMA practices, policymakers should integrate CEM into the existing environmental compliance structures. This could involve setting sector-specific carbon reduction targets or introducing national carbon trading mechanisms. Encouraging firms to develop internal carbon management strategies will create synergistic benefits when combined with EMA efforts. Fourthly, the government should develop and disseminate national guidelines on implementing EMA and CEM practices. These guidelines should include standardized procedures, performance indicators, and sector-specific templates to aid firms in practical implementation. Clear guidance will reduce uncertainty and enhance the ease of adoption, especially for small and medium enterprises. Fifthly, capacity-building initiatives are crucial. Policymakers should invest in training programs, workshops, and certification courses in partnership with academic institutions and environmental consultants. These initiatives will build technical expertise within firms and enhance their readiness to integrate environmental practices into core operations. Sixthly, a national recognition scheme such as a “Sustainable Industry Award” should be introduced to publicly reward firms that demonstrate excellence in EMA and CEM. Such non-monetary incentives can enhance reputational value and encourage peer firms to adopt similar practices. Lastly, fostering public–private partnerships (PPPs) is essential for promoting green technology adoption. Policymakers should facilitate collaborations between government agencies, research institutions, and industries to support the transfer and development of cost-effective technologies that aid in EMA and carbon emission control.

Theoretical implications

The findings of this study contribute significantly to the theoretical discourse on sustainability accounting and performance by integrating insights from both the Resource-Based View (RBV) and Institutional Theory. From the RBV perspective, the strong and consistent impact of Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) practices—such as Eco-Efficiency Improvement (EEI), Environmental Cost Tracking (ECT), Life Cycle Assessment Integration (LCAI), and Environmental Reporting Transparency (ERT)—on ESG performance suggests that these capabilities function as valuable, rare, and inimitable resources that enhance a firm’s ability to respond strategically to environmental challenges. These internal competencies are not merely operational tools but serve as strategic levers that enable firms to achieve a competitive advantage through superior sustainability performance. Furthermore, the significant moderating role of Carbon Emission Management (CEM) provides robust support for Institutional Theory, which argues that firms are influenced by external institutional pressures—including regulatory mandates, stakeholder expectations, and industry norms—to conform to socially and environmentally acceptable practices. The amplification of EMA’s effects through CEM suggests that firms operating in environmentally exposed sectors, such as garment manufacturing, are increasingly embedding carbon-related considerations into their strategic frameworks not just for compliance, but as a means of institutional legitimacy and long-term viability.

In addition, the dual-method approach of employing both Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) adds a novel methodological dimension to the theoretical conversation. While PLS-SEM validates the hypothesized linear relationships, fsQCA uncovers the configurational equifinality—showing that multiple combinations of EMA and CEM practices can lead to high ESG performance. This methodological pluralism reflects the complexity of real-world organizational behavior, offering a more nuanced understanding that goes beyond traditional cause-effect assumptions. It emphasizes that sustainability performance is not achieved through isolated practices but through the alignment of multiple, context-specific strategies.

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between EMA practices and sustainability performance in Bangladesh’s manufacturing sector, it has some limitations that offer directions for future research. One limitation is the focus on a single country, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions or industrial contexts. Future studies could expand the geographical scope by examining the impact of EMA practices across different countries or regions with varying levels of industrial development, policy frameworks, and environmental challenges. Another limitation of this study is its sector-specific sampling frame, which focused exclusively on the garment manufacturing industry; this was a deliberate design choice due to the sector’s significant environmental exposure and regulatory relevance. Additionally, future research could explore the effectiveness of specific EMA components, such as EEI or ECT, in different industries (e.g., textiles, automotive, etc.), as the environmental and operational challenges vary. Another potential avenue for research could involve investigating the long-term effects of EMA practices on sustainability performance, incorporating longitudinal data to assess the sustainability outcomes over time. Furthermore, examining the influence of external factors, such as government policies, international environmental agreements, or market forces, could provide a more holistic understanding of how EMA practices interact with broader sustainability initiatives.

Data availability

Dataset is attached.

References

Adediran SA, Alade SO (2013) The impact of environmental accounting on corporate performance in Nigeria Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 5:141–151

Ahmad M, Waseer WA, Hussain S, Ammara U (2018) Relationship between environmental accounting and non-financial firms performance: An empirical analysis of selected firms listed in Pakistan Stock Exchange, Pakistan. Adv Soc Sci Res J 5(1)

Ali Q, Salman A, Parveen S (2022) Evaluating the effects of environmental management practices on environmental and financial performance of firms in Malaysia: the mediating role of ESG disclosure. Heliyon, 8(12)

Almeyda R, Darmansya A (2019) The influence of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure on firm financial performance. IPTEK J Proc Ser (5), 278–290

Asiaei K, Bontis N, Alizadeh R, Yaghoubi M (2022) Green intellectual capital and environmental management accounting: Natural resource orchestration in favor of environmental performance. Bus Strategy Environ 31(1):76–93

Aziz F, Chariri A (2023) The effect of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure and environmental performance on stock return. Diponegoro J Account 12(3)

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17(1):99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Brooks C, Oikonomou I (2018) The effects of environmental, social and governance disclosures and performance on firm value: A review of the literature in accounting and finance. Br Account Rev 50(1):1–15

Burritt RL, Saka C (2006) Environmental management accounting applications and eco-efficiency: case studies from Japan. J Clean Prod 14(14):1262–1275

Burritt RL, Herzig C, Tadeo BD (2009) Environmental management accounting for cleaner production: The case of a Philippine rice mill. J Clean Prod 17(4):431–439

Burritt RL, Herzig C, Schaltegger S, Viere T (2019) Diffusion of environmental management accounting for cleaner production: Evidence from some case studies. J Clean Prod 224:479–491

Camilleri MA (2015) Environmental, social and governance disclosures in Europe. Sustain Account, Manag Policy J 6(2):224–242

Christ KL, Burritt RL (2013) Environmental management accounting: the significance of contingent variables for adoption. J Clean Prod 41:163–173

Christine D, Yadiati W, Afiah NN, Fitrijanti T (2019) The relationship of environmental management accounting, environmental strategy and managerial commitment with environmental performance and economic performance. Int J Energy Econ Policy 9(5):458–464

Cicchiello AF, Marrazza F, Perdichizzi S (2023) Non‐financial disclosure regulation and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance: The case of EU and US firms. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 30(3):1121–1128

Deb BC, Rahman MM, Rahman MS (2022) The impact of environmental management accounting on environmental and financial performance: empirical evidence from Bangladesh. J Account Organ Change 19(3):420–446

Ferreira A, Moulang C, Hendro B (2010) Environmental management accounting and innovation: an exploratory analysis. Account Audit Account J 23(7):920–948

Fithriyana R, Adrianto F, Rahim R (2022) Literature review: relationship between environmental, social and governance (ESG) on financial performance (FP). Int J Econ, Bus Account Res (IJEBAR) 6(3):2540–2549

Fuzi NM, Habidin NF, Janudin SE, Ong SYY (2019) Environmental management accounting practices, environmental management system and environmental performance for the Malaysian manufacturing industry. Int J Bus Excell 18(1):120–136

Gillan S, Hartzell JC, Koch A, Starks LT (2010) Firms’ environmental, social and governance (ESG) choices, performance and managerial motivation. Unpublished working paper, 10

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM Eur. Bus. Rev 31:2–24

Harjoto MA, Wang Y (2020) Board of directors network centrality and environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance. Corp Gov: Int J Bus Soc 20(6):965–985

Huang DZ (2021) Environmental, social and governance (ESG) activity and firm performance: A review and consolidation. Account Financ 61(1):335–360

Husted BW, de Sousa-Filho JM (2017) The impact of sustainability governance, country stakeholder orientation, and country risk on environmental, social, and governance performance. J Clean Prod 155:93–102

Jalaludin D, Sulaiman M, Ahmad NNN, Nazli N (2010) Environmental management accounting: an empirical investigation of manufacturing companies in Malaysia. J Asia-Pac Cent Environ Account 16(3):31–45

Khan SAR (2019) The nexus between carbon emissions, poverty, economic growth, and logistics operations-empirical evidence from southeast Asian countries Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26:13210–13220

Kumar P, Firoz M (2022) Does accounting-based financial performance value Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) disclosures? A detailed note on a corporate sustainability perspective. Australas Account, Bus Financ J 16(1):41–72

Kuzey C, Uyar A (2017) Determinants of sustainability reporting and its impact on firm value: Evidence from the emerging market of Turkey J. Clean. Prod. 143:27–39

Latif B, Mahmood Z, Tze San O, Mohd Said R, Bakhsh A (2020) Coercive, normative and mimetic pressures as drivers of environmental management accounting adoption. Sustainability 12(11):4506

Lee KH, Cin BC, Lee EY (2016) Environmental responsibility and firm performance: The application of an environmental, social and governance model. Bus Strategy Environ 25(1):40–53

Linnenluecke MK (2022) Environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance in the context of multinational business research. Multinatl Bus Rev 30(1):1–16

Lokuwaduge CSDS, Heenetigala K (2017) Integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure for a sustainable development: An Australian study. Bus Strategy Environ 26(4):438–450

Maama H (2021) Institutional environment and environmental, social and governance accounting among banks in West Africa. Meditari Account Res 29(6):1314–1336

Mohd Khalid F, Lord BR, Dixon K (2012) Environmental management accounting implementation in environmentally sensitive industries in Malaysia. 6th NZ Management Accounting Conference, Palmerston North. 1-31

Mooneeapen O, Abhayawansa S, Mamode Khan N (2022) The influence of the country governance environment on corporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance. Sustain. Account Manag Policy J 13(4):953–985

Ng TH, Lye CT, Chan KH, Lim YZ, Lim YS (2020) Sustainability in Asia: The roles of financial development in environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance. Soc Indic Res 150:17–44

Qian W, Burritt R, Monroe G (2011) Environmental management accounting in local government: A case of waste management. Account Audit Account J 24(1):93–128

Qian W, Hörisch J, Schaltegger S (2018) Environmental management accounting and its effects on carbon management and disclosure quality. J Clean Prod 174:1608–1619

Ragin CC (2006) Set relations in social research: Evaluating their consistency and coverage Political analysis 14(3):291–310

Rahman MM, Rahman MS (2020) Green reporting as a tool of environmental sustainability: some observations in the context of Bangladesh. Int J Manag Acc 2(2):31–37

Rahman MM, Islam ME (2023) The impact of green accounting on environmental performance: mediating effects of energy efficiency. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30(26):69431–69452

Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Pick M, Liengaard BD, Radomir L, Ringle CM (2022) Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade Psychology & Marketing 39(5):1035–1064

Schaltegger S, Gibassier D, Zvezdov D (2013) Is environmental management accounting a discipline? A bibliometric literature review. Meditari Account Res 21(1):4–31

Shaikh I (2022) Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practice and firm performance: an international evidence. J Bus Econ Manag 23(1):218–237

Solovida GT, Latan H (2017) Linking environmental strategy to environmental performance: Mediation role of environmental management accounting. Sustain Account, Manag Policy J 8(5):595–619

UNIDO (2021) Resource Efficient and Cleaner Production (RECP) in Bangladesh: Final Report. United Nations Industrial Development Organization. https://www.unido.org/our-focus-safeguarding-environment-resource-efficient-and-low-carbon-industrial-production/resource-efficient-and-cleaner-production-recp

World Bank (2022) Greening Global Value Chains: How the Private Sector Can Help Deliver Sustainable Development Goals. World Bank Group. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/global-value-chains

Xue Q, Wang H, Bai C (2023) Local green finance policies and corporate ESG performance Int Rev. Financ. 23:721–749

Zaneta F, Ermaya HNL, Nugraheni R (2023) Hubungan environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure, green product innovation, environmental management accounting terhadap firm value JIAFE (Jurnal Ilmiah Akuntansi Fakultas Ekonomi). 9(1):97–114

Zaneta F (2021) Hubungan environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure, green product innovation, dan environmental management accounting terhadap firm value (Doctoral dissertation, Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran Jakarta)

Zheng GW, Siddik AB, Masukujjaman M, Fatema N (2021) Factors affecting the sustainability performance of financial institutions in Bangladesh: The role of green finance. Sustainability, 13, 10165

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liu Xia: Writing—original draft, Validation, Supervision. Nazneen Fatema: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Md. Mominur Rahman: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. Arman Hossain: Literature review, Writing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethically approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Northern University Bangladesh (Approval Number: 2023-005-028) on 15 April 2023. The ethical approval specifically covers the research procedures and data collection activities conducted for this study.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Consent was obtained using a standardized written form, signed by each participant before participation in the survey. Consent was collected between 25 June and 10 July 2023 by the corresponding author. Each participant was clearly informed, in writing, about the objectives and scope of the study, their voluntary participation, their right to withdraw from the study at any stage without any consequences, and the measures taken to ensure anonymity and confidentiality. The consent covered participation in the survey, the use of data for academic research purposes, and the publication of aggregated findings. No vulnerable individuals (such as minors or legally protected groups) were involved in this study. All procedures were conducted in accordance with ethical research principles for non-interventional social science studies.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, L., Fatema, N., Rahman, M.M. et al. Nexus of environmental management accounting, and carbon emission management on environmental, social, and governance performance: evidence from symmetrical and asymmetrical approach. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1073 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05465-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05465-9

This article is cited by

-

Advancing agro-environmental sustainability in developing economies: the moderating role of governance in aligning inclusive justice and financial inclusion

Discover Sustainability (2025)

-

Assessing the role of green finance in enhancing sustainability performance of financial institutions in Nepal using two stage PLS SEM and ANN approach

Discover Sustainability (2025)

-

Financial development shapes CO2 emissions by enhancing technology and industrial structure in Bangladesh

Discover Sustainability (2025)