Abstract

The growth of financial markets has facilitated individuals to invest in a wide range of securities and financial assets. As a result, behavioral finance has provided insight into traits and psychological factors that influence investors’ intentions and decisions. This paper investigates the impact of attitudinal factors, financial self-efficacy, and financial literacy on individual equity investors’ decision-making by integrating the theory of planned behavior and social cognitive theory in comprehending these elements and their impact on investment intention using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). The study employed primary data by administering a questionnaire via in person and online to 430 Indian equity investors. To check the impact of gender variances, measurement invariance in composite models (MICOM) and multi-group analysis (MGA) was applied. The findings of the study suggested that two of the attitudinal constructs (Perception of Regulators and Perceived Benefit) had a substantial impact on the investment intention of equity investors. Financial self-efficacy significantly impacted equity investors’ investment intention. Further, the findings of MICOM and MGA showed that gender significantly moderates the relationship between subjective norms and financial literacy towards investment intention. The study emphasizes the significance of improving retail investors’ financial self-efficacy and literacy, collecting data from India and provides a comprehensive model to describe the intention of equity investors, contributing to overall investor behavior literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The quest for perpetual wealth creation has emerged as of the utmost importance for individuals, entities, and states alike in a time of changing financial paradigms and dynamic economic environments. The level of individual involvement in financial markets has experienced a significant increase in recent years (L. Calvet et al. 2016).

Equity markets occupy a significant portion of the global financial market, with a total market capitalization of ~$108.6 trillion as of the second quarter of 2023, representing a substantial share of the global financial market, underscoring their importance as a critical component of the global economy. The U.S. equity market is the largest, accounting for around 42.5% of the total global market capitalization, followed by the European Union at 11.1% and China at 10.6% (Neufeld, 2023). These figures highlight the dominance of equity markets in major economies, making them compelling investment options for wealth accumulation and capital growth, attracting investors with diverse motivations and goals.

The Indian equity market has grown significantly, reaching a market value of USD 4 trillion for the first time in November 2023, placing India among the world’s leading markets, emphasizing the crucial need of understanding investor intentions in this evolving financial landscape (PTI, 2023). Equity markets in developing nations are essential for financial inclusion and overall economic growth. Understanding individual investors’ objectives can aid governments, policymakers and financial institutions (Levine, 2021).

However, predicting their behavioral intention to invest, particularly in a specific asset class like equities, remains a multifaceted challenge (Almansour et al. 2023). Traditional studies of finance have addressed this topic by emphasizing economic perspectives that imply an individual as a rational decision-maker regarding the optimal path of action. While, several theoretical frameworks, “including bounded rationality” (Simon, 1955), “cognitive dissonance” (Hardyck, 1965), “prospect theory” (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979), and “heuristics” (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974) have demonstrated the inconsistency of these hypotheses and their inability to account for the unpredictable behavior of investors.

Behavioral finance investigates the psychological impact on investors and its implications on financial markets (J. Jain et al. 2020). Multiple studies have revealed that investors frequently deviate from rational behavior due to various behavioral factors that have a significant impact on their investment intentions (Adam and Elvia, 2014; R. Jain and Sharma, 2022; Nadeem et al. 2020).

Intentions are “referred to capture motivational factors that influence a behavior” (Ajzen, 1991). Investment intention refers to the decision to invest in a short or long-term asset. Previous studies (e.g., Christiansen et al. 2008; Grinblatt et al. 2011; Guiso and Jappelli, 2005) have demonstrated a strong association between an investor’s intention and factors like education, income, age, gender, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, financial literacy and risk tolerance. There are various prominent theories to study intention, like “Theory of Reasoned Action” (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), “Social Cognitive Theory” (Bandura, 1986), and “Theory of Planned Behavior” (Ajzen, 1991). TRA explains how attitude and subjective norms influence individual decisions and behavior. SCT underlines the importance of perpetual learning and factors like self-efficacy (Bandura, 2001). Theory of Planned Behavior (henceforth TPB) extends TRA by incorporating the concept of perceived behavioral control, thereby accounting for instances where individuals might intend to take action but lack the ability or opportunity to do so (Ajzen, 1991). This makes TPB more applicable to scenarios like investment, where external factors like hassles in investing, regulatory constraints can impact behavior.

Early studies (such as Akhtar and Das, 2019; Ali, 2011; Gopi and Ramayah, 2007) have shown the use of TPB to investigate investment intentions. TPB posits that behavioral intention is formed by three key factors: Attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

Despite its usefulness, TPB has been criticized (Demarque et al. 2015). While some researchers argue that TPB is a self-interest theory with rational predictors (Bertoldo and Castro, 2016; Toft et al. 2014), others suggest enhancing the model by incorporating context-specific variables to address its constraints (Graham-rowe et al. 2015; Jang et al. 2014; Yadav and Pathak, 2016). However, any additional variables must match certain criteria to enhance the model’s explanatory power, and they should be both significant and rational to account for after multitude of behaviors. Previously, Choi and Park (2020), in their study, had decomposed subjective norms, Akhter and Hoque (2022) studied various financial aspects combined with attitude to examine the determinants of investor’s intention while, Sivaramakrishnan et al. (2017), in their research, had decomposed attitude taking Hassle Factor, Risk Avoidance and Perception of Regulators as attitudinal factor. Existing literature consistently demonstrates that Attitude exerts a beneficial and substantial influence on intention (Cuong and Jian, 2014; Ramayah, Rouibah et al. 2009). However, limited research has decomposed attitudinal factors in the context of equity investments (e.g., Akhter and Hoque, 2022; Sivaramakrishnan et al. 2017). This study is an earnest attempt to fill this gap by schematizing attitudinal factors related to the investment intentions of equity investors. This study takes a novel approach by integrating specific attitudinal factors like Perceived Benefit, which is not considered in previous decompositions of attitude with other constructs of TPB and combining it with SCT, taking the construct of financial self-efficacy.

Research has demonstrated that people with a strong understanding of financial matters are more inclined to invest in the stock market and get greater returns on their investment portfolios (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2013). For this reason, financial literacy is included as an additional determinant of investment intention.

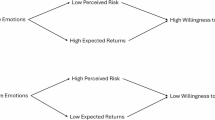

Thus, the key research question of this study is: How do decomposed attitudinal factors, financial self-efficacy, and financial literacy influence the investment intentions of equity investors? To address this, the study applied TPB by decomposing attitude into four context-specific constructs: Hassle Factor, Risk Avoidance, Perceived Benefit, and Perception of Regulators. Further, financial self-efficacy is being employed as a variable, integrating social cognitive theory with the theory of planned behavior.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: The next section provides theoretical background and hypotheses development, followed by research design, analysis and results. The study concludes with a discussion, implications, and future research agenda.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Behavioral finance serves as a link between conventional economic models and the actual decision-making processes of investors (Durand et al. 2008). It challenges the traditional assumptions of investor rationality, highlighting the influence of psychological effects, biases, fuelled by heuristics while taking investment decisions (Mahmood et al. 2024; Xia et al. 2024; Zulfiqar et al. 2018). These aspects are crucial as they significantly impact investment intentions and ultimately, investor behavior.

Intentions encompass the motivating variables that impact behavior, which is the planned action or plan to be executed. As Ajzen (1991) explains, intentions are shaped by attitudes, norms, and perceived behavioral control, making them a strong predictor of actual behavior. Multiple research investigations (e.g., Raut et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2021) have utilized investment intention as a dependent variable for assessing the inclination to invest in financial products.

Theory of Planned Behavior

Individual behavior is known to be the consequence of meticulous consideration of motivation and available information, from which two theoretical frameworks are developed: the theory of reasoned action (TRA) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The former model involves the influence of attitudes and subjective norms on behavioral intentions, with behavior being predominantly influenced by attitudes (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). The “Technology Acceptance Model” (TAM), conceptualised by Davis in 1986, is a well-recognised framework for comprehending users’ behavioural intentions about the adoption and use of information technology in various contexts (Hong et al. 2006). Driven by TRA (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975), TAM suggests that behavioral intention consists of two components: Attitude towards Behavior and Perceived Usefulness (Davis, 1989). TAM indicates that when individuals have a favorable attitude and higher perceived usefulness, they are more inclined to have a high intention to use a technology. TPB (Ajzen, 1991) expanded TRA to enhance its predictive capacity. The theory suggests that the positive attitude, together with ideal normative and volitional control beliefs, will lead to a positive behavioral intention (Ajzen, 2020). Venkatesh et al. (2003) proposed the “Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology” (UTAUT), which identifies four components of Behavioral Intention and Actual Behavior: “Performance Expectancy, Effort Expectancy, Social Influence, and Facilitating Conditions”. The TAM and UTAUT models have been extensively utilized to forecast intention in the context of technology (e.g., Abdulaziz et al. 2021; Dwivedi et al. 2019; Rahman et al. 2017).

“Self Determination Theory”, emphasizes upon intrinsic and extrinsic sources of motivation and focus on how social and cultural factors facilitate or impair individual’s choices (Deci and Ryan, 2008; Ryan and Deci, 2020). It does not focus directly on the transition from intention to behavior, while TPB explicitly posits that intentions are the primary predictors of behavior, making it a direct model for understanding how intentions translate into actions (Ajzen, 2020).

TPB has been extensively utilized in numerous studies, including food consumption behavior (Ajzen, 2015), green product purchase intention (Maichum et al. 2016), and digital coupon usage (Bakar et al. 2015), to address the intricacy of factors affecting behavioral decision-making.

TPB has been frequently used to analyze individuals’ risk adaptation intentions because of its ability to anticipate individuals’ behavior (Wang et al. 2020; Xu et al. 2021). Relatively few studies (e.g., Akhtar and Das, 2019; Cuong and Jian, 2014; Raut, 2018; Raut et al. 2021; Tamara, 2020) have applied the TPB framework to predict individuals’ intentions in the context of financial assets. These studies have established the suitability of the TPB in predicting investing intentions. Moreover, TPB has been extended by adding other factors that can enhance the model’s predictability (Savari and Gharechaee, 2020; Xu et al. 2021). The TPB was chosen for this study because it effectively captures the complexity of decision-making in equity investments by considering a broad range of factors, including individual attitudes, social pressures, and perceived control. Its flexibility and comprehensive approach make it more suitable than other theories in explaining the overall investment intentions (Ajzen, 2020).

Taylor and Todd (1995) contended that the decomposed TPB is more appropriate for comprehending variables that influence behavior. Moreover, in cases where explanatory power is unstable within a single dimension, it can be improved through decomposition (Choi and Park, 2020).

Thereby, the decomposed TPB is used in our study to forecast the intention of individual equity investors. Attitude can be highlighted by two major dimensions. Firstly, it serves as an indicator to determine the significance, detrimental effects, or worth of an action. Secondly, it establishes the nature of the behavior as agreeable or pleasurable (Fu, 2021). Existing research consistently demonstrates that Attitude exerts a beneficial and substantial influence on intention (Cuong and Jian, 2014; Ramayah, Yusoff et al. 2009). Thereby, in the scope of the present study, Attitude has been reformulated and explicitly decomposed in the context of investment into four variables: Hassle Factor, Risk Avoidance, Perception of Regulators, and Perceived Benefit.

Hassle factor

Hassle factor is defined as all the elements that may make someone uncomfortable and create barriers while engaging in a behavior (de Vries et al. 2020). It typically refers to the financial and temporal costs associated with investing and stock market participation (B.M. Barber and Odean, 2008; Grinblatt et al. 2011). In the context of equity investments, many elements exist as a hassle factor, such as incomplete information, difficulties in operating and trading, payment delays, unethical practices, market volatility, ignorance and pricing manipulations in the market.

The concept of “hassle factor” measures the perceived difficulty level in the equity investment process, as experienced by the investor. Bogan (2008) asserts that consideration of expensive information related to the financial market also influences individuals in developing the attitude not to invest in the stock markets. Therefore, it is evident that the hassle factor belongs in the same category as attitude. Thus, proposing the first hypothesis of this study as:

H1. Hassle factor negatively influences the investment intention of equity investors.

Risk avoidance

Risk avoidance is described as a consistent tendency to avoid risk; it is the opposite of risk tolerance. Because of their high price volatility and unpredictable rewards, equities have always been viewed as riskier securities than debt instruments. Because of this, equities are typically included in research that aims to understand the factors influencing investors’ investing behaviors.

The attitudes of risk held by investors play a crucial role in determining their processes of decision-making. There are three different types of attitudes towards risk: risk aversion, reflecting a tendency to avoid taking risks; risk neutrality, indicating a state of indifference towards risk; and risk-loving, indicating a preference for risk (Ricciardi and Rice, 2014). The majority of individual investors typically fit into the risk aversion group, defined by their tendency for lower-risk investments over higher risks (Dorn and Huberman, 2010). Although it is acknowledged that risk-neutral and risk-loving attitudes do have an impact on investment decisions, this study does not incorporate them as its main objective is to comprehend the emotional responses that are prevalent among general investors. Researchers studying subjective risk have observed that this aspect of risk is determined by evaluating the thoughts, beliefs, and emotions associated with risk in a particular context (Ricciardi, 2007). Risk avoidance can be classified as an emotional response, particularly when assessing investments.

People behave differently while making investing decisions due to their varying risk tolerance levels. Anantanasuwong et al. (2024) find that a higher risk aversion attitude is adversely associated with stock market participation. This suggests a lower likelihood of equity investments among investors with greater risk avoidance ratings, which makes risk avoidance as a factor to determine attitude. Hence, proposing the next hypothesis as:

H2: Risk Avoidance negatively influences investment intention of equity investors.

Perception of Regulator

A crucial part of the growth and impartial operation of the securities markets is rendered by the government. The investor’s affective responses would likewise be shaped by the regulation. According to Guiso and Sodini (2013), participation in financial markets requires investors to assess the risk-return trade-off and have trust in information sources, fund managers, and the overall financial system. As per Calvet and Campbell (2009), trust, being a consistent individual trait, accounts for the constant reluctance or tendency to develop the attitude of investing in high-risk assets like equities. The individual’s Perception of the regulator’s performance and trustworthiness can determine whether they experience comfort or discomfort (Chan and Chan, 2011). Therefore, the Perception of a Regulator would likewise be classified inside this category. We propose that confidence in the regulators would be reflected as faith in the capital market system. As a result, there should be a greater possibility that investors will engage in the capital market and increase their equity investments. From this reasoning, the next hypothesis of the study is:

H3: Perception of Regulators positively and significantly influences investment intention of equity investors.

Perceived Benefit

According to Kim et al. (2007), perceived benefits might be either intrinsic or extrinsic. The financial gains are ascribed to extrinsic incentives, whereby equity investors anticipate substantial gains, adding value to them. Individual investors, therefore, view their equity assets as valuable when they feel they can sell them at any time. Secondly, investors find equities enticing because of their potential to appreciate in value over time, providing a higher return on investment. As a result, equities have value because of their liquidity and growth potential, which supports the objectives of investment. Investor decision-making has been found to be significantly impacted by liquidity and the prospect of growth (Ng and Wu, 2006).

As attitudes are shaped by both advantages and disadvantages, Perceived Benefit serves as an additional means of assessing attitude. This is because the affect component of attitude is associated with the expected emotions during behavior execution (Kraft et al. 2005; Tingchi Liu et al. 2013). Therefore, proposing the next hypothesis as:

H4: Perceived Benefit positively influences investment intention of equity investors.

Subjective norm

According to Fong and Wong (2015), subjective norm is the idea that people should participate in a particular activity or refrain from performing a particular task based on the opinions of the majority of those around them. TPB research stated that individuals exhibit a greater propensity to participate in stock markets when they receive advice or recommendations from people in their immediate vicinity (Cuong and Jian, 2014). Thus, an individual may form the intention to partake in a certain action due to social pressure, regardless of what drives them to do that behaviour (Venkatesh and Davis, 2000). Thus, the next hypothesis of the study is proposed as:

H5: Subjective Norm positively influences investment intention of equity investors.

Social cognitive theory

Social cognitive theory (SCT) encompasses a comprehensive understanding of human behavior, highlighting how individuals engage in processes of self-reflection, self-regulation, and self-organization (Bandura, 1989). SCT posits that behavior is an observable action influenced by the anticipated outcomes of that behavior. Self-efficacy, which plays an important role in shaping an individual’s behavior and motivation, lies at the core of this theory. Individuals having high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in and successfully perform the desired behavior compared to those with low self-efficacy (Wu and Kuang, 2021).

Financial self-efficacy

According to Asebedo and Seay (2018), self-efficacy in finance is associated with favorable financial outcomes and behaviors. In financial decision-making, self-efficacy refers to one’s confidence in achieving financial objectives (Snyder and Lopez, 2012). These goals can range from long-term aspirations, such as retirement, to short-term needs, like covering monthly expenses (Lown, 2011). FSE has been found to mediate long-term investment decisions, driving individuals to make financial choices that enhance their long-term financial well-being (Husnain et al. 2019).

The existing literature pertaining to Indian stock markets suggests that FSE impacts financial knowledge, wealth accumulation, portfolio selection, investment behavior, savings, gender differences, and retirement saving strategies (Chatterjee et al. 2011; Forbes and Kara, 2010).

The construct of self-efficacy offers a more focused assessment of individuals’ belief in their capacity to successfully execute a particular behavior, thereby establishing a more immediate connection between their behavioral intentions and actions within a given context. For instance, previous research has investigated the impact of financial self-efficacy on stock market investment in India (Akhtar and Das, 2019) and financial services in Uganda (Mindra et al. 2017). Together, these findings support the idea that self-efficacy may be used to validate the relationship between FSE and investment intention. Hence, proposing the next hypothesis as:

H6: FSE positively and significantly influences the investment intention of equity investors.

Integration of financial literacy into the model

Prior studies have demonstrated that incorporating domain-specific elements in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) can enhance its predictive capability (Yadav and Pathak, 2016). Furthermore, the fundamental elements of the TPB have been expanded to include financial literacy in order to assess the intention to invest among potential investors. The significance of financial literacy was considered because of its substantial influence on financial action (Khan, 2016; Tauni et al. 2017).

Financial literacy is essential for making well-informed and efficient investing choices. Multiple theoretical frameworks substantiate this concept, highlighting the influence of financial knowledge and abilities on investor behavior and results. Studies have indicated that those possessing a robust comprehension of financial concerns are predisposed to making stock market investments and get greater returns on their investment portfolios (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2013). Greater levels of financial literacy are linked to reduced levels of household debt and lower rates of delinquency. Financial literacy programs can significantly influence financial behavior and outcomes, leading to enhanced savings rates and more informed investment decision-making.

This study has taken the Hassle factor as one of the attitudinal factors that influences investment behavior. Hassle factor and financial literacy are distinct in a way, as a person with high financial literacy may still find certain investment processes to be a hassle, just as a person who does not find investing to be a hassle might still struggle due to low financial literacy. Lusardi and Tufano (2015) further elaborate on the practical barriers that financial literacy cannot always overcome, emphasizing the role of perceived hassle in financial decision-making. In summary, while financial literacy provides investors with the requisite information to make informed choices, the hassle factor concerns the practical and psychological barriers that might prevent them from acting on that knowledge. The conceptual model becomes more robust by including both factors, as these two factors interact but remain distinct in influencing investor behavior.

Theoretical frameworks and empirical findings robustly support the inclusion of financial literacy within the framework of formulating investment choices. The infusion of financial literacy is posited to augment investment performance, elevate financial well-being, and contribute to the efficacy and stability of the financial system. Hence, we propose our last hypothesis as:

H7: Financial literacy positively influences investment intention of equity investors.

Implementing the theoretical model and hypotheses presented earlier, the proposed model is succinctly outlined in Fig. 1. The constructs, namely subjective norms, financial self-efficacy, financial literacy, Perceived Benefit, and Perception of Regulators, are hypothesized to positively influence the investment intention of equity investors. While constructs like Hassle Factor and Risk Avoidance are hypothesised to have a negative impact on the investment intention of equity investors.

Gender as a moderator

Prior studies have demonstrated that men and women have different kinds of socially constructed cognitive frameworks, which lead to different ways of decision-making (Bhardwaj, 2017; Luis et al. 2015). Consequently, multiple studies have investigated gender as a moderator across many fields. The impact of gender differences on stock market participation has seen a significant emphasis (Almenberg and Dreber, 2015; Feng and Seasholes, 2008).

B. Barber and Odean (2001) find that women as typically risk-averse and cautious while making investment choices, whereas men are at ease taking more risk to reach their investment objectives. Montford and Goldsmith (2016) stated that women preferred to allocate a lower proportion of their windfall to stocks compared to men. Lai (2019) found significant gender differences in the relationship between TPB factors and stock market participation. The following hypotheses are formulated based on the above discussion:

H8a–H8g: Gender moderates the relationship among TPB factors, financial self-efficacy, financial literacy, and investment intention of equity investors.

Research design

Data collection was organized in two phases: the first involved gathering contact information and responses through fund managers within India, while the second phase utilized online distribution of the questionnaire, verifying whether participants were equity investors. Data was collected from India as it has common characteristics like rapid economic growth, industrialization, and rising consumer demand with other developing countries, being a perfect representative in the context of developing nations. The survey consisted of items related to constructs and also included demographic questions such as age, income, and education. The standardized survey approach ensured consistency in data collection and analysis, making the results reliable and valid for further research and policy implications.

Variable construction

The survey employed a 5-point Likert scale to measure respondents’ agreement. Here, 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and 5 indicated “strongly agree”. The items to measure the constructs were adapted from previous literature as described in Table 1. The hassle factor and risk avoidance had three items each. While Perception of Regulators and Perceived Benefit had four items each. Subjective norms had three items; FSE was measured by five items, while Financial Literacy was measured by four items.

Sampling and data collection

In 1995, Barclay introduced the 10-times rule, subsequently acknowledged in PLS-SEM literature (Barclay et al., 1995), which recommends a minimum sample size of either ten times the maximum number of formative indicators for a construct or ten times the highest number of structural paths directed at a single variable (Hair et al. 2017, p 24).

However recent research (Hair et al. 2019; Kline, 2018; Ringle et al. 2020), advocates using power analysis to determine sample size more accurately. Power analysis identifies the minimum required sample size based on the model component with the most predictors (Roldán and Sánchez-Franco, 2012), with an accepted statistical power threshold of 80% or higher (Hair et al. 2017; Uttley, 2019).

The sample size was calculated by ensuring compliance with the minimal sample size standards. Through a convenient and snowball sampling method, 430 people who are actively involved in equity investments completed a self-administered questionnaire that served as the source of the data for this study. Ultimately, 418 respondents were included in the analysis after removing the outliers. The rationale for using these methods was twofold. First, the random probabilistic sampling ensured an unbiased representation of the population, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the findings (Xie et al. 2024). Second, convenience sampling facilitated access to equity investors who are otherwise challenging to reach, providing critical expert insights for the exploratory dimension of the study (Rana and Poudel, 2023).

Analysis and results

Demographic profiles

Table 2 presents an overview of the characteristics of the respondents who took part in this study. The table indicates that 63.16 per cent of the participants in the sample were male, 35.88 per cent were female, and 0.96 per cent chose not to disclose their gender. The age distribution was predominantly concentrated in the 21–30 years old age group. This percentage aligns with previous research that emphasized the importance of this particular age group. Metawa and Almossawi (1998) proposed that studying the perceptions of individuals and investors between the ages of 20 and 50 would have a greater influence on policies. This representative respondent offers insightful information about the factors that influence investors’ intention to invest in equities. Further, the reliability of items and collinearity are checked in the measurement model.

Measurement model

The present study utilised the partial least-squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) technique to analyze the survey data, using SmartPLS 4.0. PLS-SEM has seen extensive use in the fields of management and information systems, and has been well acknowledged for its ability to give reliable assessments in the domains of banking and finance (Avkiran and Ringle, 2018; Hair et al. 2019). PLS-SEM is a non-parametric technique that aims to maximize the variance explained in latent constructs. Avkiran and Ringle (2018) stated that behavioral finance offers enormous prospects for applying PLS-SEM techniques. PLS-SEM imposes fewer constraints on residual distributions, measuring scales, and sample sizes (Monecke and Leisch, 2012). Therefore, PLS-SEM is considered appropriate for examining an extensive research model that has emerged as an estimation model integrating theories and empirical investigations.

The present study looked at the measurement model approach to check the reliability of constructs, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). We employed Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability to evaluate the reliability. According to J.F. Hair et al. (2019), it is recommended that the threshold levels for these two criteria should exceed 0.70 and 0.60, respectively. Table 3 demonstrates that the reliability of constructs with multiple items is thoroughly established.

The assessment of validity is conducted by examination of convergent validity and discriminant validity. This was assessed by examining variable loadings and the AVE. The table presents the average variance extracted (AVE) values that surpass the suggested threshold of 0.50. Furthermore, all indicators’ loadings are higher than the predetermined cut-off value. Internal consistency provides the reliability of a construct by analyzing the intercorrelations of the observed variables. This is done using composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha.

“The degree to which a concept is unique and different from other constructs is referred to as discriminant validity”. Table 4 presents the use of the Fornell-Larcker criterion to assess the discriminant validity among constructs. In order to meet this requirement, the square root of the AVE by a construct must exceed the correlation it exhibits with the other constructs. The results indicate that discriminant validity has been successfully achieved. In order to further evaluate discriminant validity, the heterotrait-monotrait of correlations, as proposed by Henseler et al. (2015), is utilized. The purpose of the test is to determine whether the 95 per cent confidence interval of the HTMT excludes the value of 1. This was observed for all eight constructs in the study, namely HF, RA, RP, PB, SN, FSE, FL, and II. Table 5 demonstrates that all values are below one, thus confirming the presence of discriminant validity. Overall, it is evident that all requirements were satisfied, indicating the validity and reliability of the measurement model.

Structural model

The chosen method of SEM was based on two factors: first, it facilitates the evaluation of a number of independent multiple regression equations; second, it can include latent variables in the research and estimate measurement errors in the evaluation procedure (Hair et al. 2011; Sarstedt et al. 2021).

Prior to evaluating the structural model, we analyzed the collinearity among the latent variables by assessing the variance inflation factor (VIF) values. All VIF values were below 3, implying no signs of multi-collinearity concerns.

According to Ramayah et al. (2016), the R2 value is used to determine the quality of the structural model. According to Hair et al. (2019), the R2 can be used to measure the coefficient of determination and the significance level of the path coefficients (beta values). The R2 for the obtained data was 0.554, meaning that 55 per cent of the variability in investment intention among equity investors can be accounted for by factors such as the Hassle Factor, Risk Avoidance, Perception of Regulators, Perceived Benefit, Subjective Norms, Financial Self-efficacy, and Financial Literacy. The current study conducted a statistical analysis to determine the relevance of the path coefficients in the structural model and performed the bootstrap analysis using 5000 sub-samples. The structural model examined the relationship between indicators as shown in Fig. 2. The bootstrapping approach, implemented in accordance with the structural model, enables statistical testing of the hypothesis (Hair et al. 2011).

The results presented in Table 6, indicate that Subjective Norms (β = 0.428) are most significant with investment intention, followed by Perceived Benefit (β = 0.341) and subsequently financial self-efficacy (β = 0.096) and Perception of Regulators (β = 0.082).

This depicts that Perception of the regulator, perceived Benefit, subjective norms, and financial self-efficacy were found to have a statistical relationship with the investment intention of equity investors. All of these constructs had a positive association with the investment intention of equity investors. While, hassle factor (β = −0.059), risk avoidance (β = −0.053), and financial literacy (β = 0.036), identified to have no significant effect on the investment intention of equity investors. Therefore, hypothesis H3–H6 are accepted.

Measurement invariance for composite models

MICOM was utilized to find out if there was any identified heterogeneity in the study in through its three-stage process (Henseler et al. 2016). Step 1 involves ensuring that each group’s composites are defined uniformly, including equivalent indicators for each measurement model, equivalent data handling, and identical algorithm settings or optimization criteria. Thus, the current study establishes configural invariance.

To ensure that the initial correlation should be greater than or equal to the 5% quantile, the permutation technique was applied in Step 2. The major requirement of partial measurement invariance is established, and compositional invariance was attained, as Table 7 demonstrates that all of the initial correlation values are >5% quantile values (Matthews, 2017). Lastly, Step 3 was carried out in two sections, 3(a) and 3(b), to compare the variances and composite mean values. It will be regarded as full measurement invariance if the values of the two portions are equal (Henseler et al. 2016).

Table 7 indicates that the mean differences between males and females for all variables fall within the 2.5–97.5% range. Additionally, variance differences for both groups lie within the confidence intervals, except in the case of ESN. The MICOM results showed partial measurement invariance for ESN and full measurement for other variables, EHF, RA, RP, EPB, FSE, FL, and EINT.

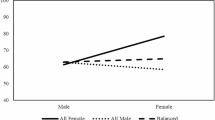

Multi-group analysis (gender moderation)

The moderating effect of gender was measured using the MGA technique with 5000 sub-samples, bootstrapping, and bias-corrected data (Mishra et al. 2018). The sample was split into two groups for the MGA: males (n = 254) and females (n = 164). Henseler’s MGA, a non-parametric method introduced by Henseler et al. (2009), was employed to investigate gender disparities. This method uses bootstrapping to directly assess the path coefficients between two groups, to demonstrate significant differences in the path coefficient (Hair et al. 2019).

As shown in Table 8, the p-value differences for hypotheses H8e and H8g are below 0.05, indicating a significant moderating effect of gender on the relationships between ESN and FL with EINT. However, the p-value differences for EHF, RA, RP, EPB, and FSE with EINT exceed 0.05, thus rejecting these hypotheses.

Discussion and implications

This research aims to comprehend an individual’s inclination to invest in equities by integrating the “Theory of Planned Behavior” (TPB) and “Social Cognitive Theory” (SCT). The statistical results of PLS-SEM demonstrated a substantial link between the Perception of regulators, perceived benefit, subjective norms, and financial self-efficacy with the investment intention of equity investors. In this study, within the framework of TPB, the construct of Attitude was divided into four distinct constructs: Hassle factor, Risk avoidance, Perception of regulators, and Perceived Benefit. Among these constructs, the Perception of regulators and perceived benefit exhibited a statistically significant relationship with the investment intention of equity investors.

The parameters of the hassle factor in our research included procedural complexity, expenses and time incurred to comprehend the product (Giné et al. 2008). While the path relationship between the Hassle Factor and the investment intention of equity investors in our study has a beta value (β = −0.059), which was inconsistent with the previous study done by Sivaramakrishnan et al. (2017). We hypothesized that Risk Avoidance negatively influences the investment intention of equity investors; results were insignificant to the same. Previous research on loss aversion (e.g., Ang et al. 2005; Benartzi and Thaler, 1995) shows that compared to households with traditional preferences, those who are loss-averse tend to avoid stock markets or invest less in equities.

For individual investors, the concept of “perception of regulator” is often interchangeable with “system trust,” indicating that it pertains to their opinions about the formal regulations of a certain system (Grayson et al. 2008). To lure additional investors to the financial markets, it is crucial that this level of trust in the system, also known as “broad scope trust,” is high to ensure investor protection and the successful delivery of financial services by providers (Hansen, 2012). This is corroborated by the current study as a proposed hypothesis that the perception of regulators positively influences the investment intention of equity investors, which is being accepted as per the analysis. This study depicts that Perceived Benefit has a significant relationship with investment intention, consistent with previous studies (Ng and Wu, 2006).

This study also found that subjective norms have a clear impact on investment intentions. This may be because when investors lack information about factors like privacy and security, they tend to rely on their social circles for guidance (Gopi and Ramayah, 2007).

Moreover, it was shown that there was a significant relationship between investment intention and FSE. This research supports Bandura’s (1978, 1986) clear assertion that, even in uncertain circumstances, an individual’s financial behavior is largely determined by their FSE (Amatucci and Crawley, 2011; Lown, 2011).

This paper also took into consideration Financial Literacy as an additional construct to study investment intention. Results show that Financial Literacy is not significantly associated with investment intention. The reasoning for the same can be that financial literacy is associated with stock market participation; in some cases, individuals with high financial literacy might be more aware of market risks, leading them to refrain from investing (van Rooij et al. 2011). Lusardi and Mitchell (2013) found that while financial literacy is crucial for making informed decisions, the intention to invest also depends on other factors such as trust in the financial system, past experiences, and personal financial goals. A person might be financially literate but still not intend to invest due to a lack of confidence in the market or fear of losses. The implications of these findings are discussed below.

Implications

This research has broadened our comprehension of the factors impacting investors’ intention to invest in equity products. With a scarcity of studies in this area, this investigation seeks to enrich the existing literature. The outcomes achieved are guided by the integration of the TPB and the SCT theoretical framework. While the TPB has been applied in various domains, including finance (e.g., Akhtar and Das, 2019; Raut, 2020; Roy et al. 2017), this study is unique in that it breaks down one of the theory’s constructs, Attitude, into four context-specific constructs, adding depth and value to the field. Furthermore, FSE is employed as a factor from SCT, and the significance of incorporating Financial Literacy as an additional construct is explored as well.

Prior research, such as the study conducted by Azarmi et al. (2011), has drawn comparisons between stock markets in India and casinos, highlighting the reluctance of individuals to engage in participation. In this study, we aim to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing human behavior in financial decision-making.

The present research emits a range of inputs that are advantageous for both financial experts and individuals in formulating strategies and making financial decisions pertaining to financial markets.

An economy’s development relies heavily on the presence of a robust financial market that encompasses a wide range of participants. In a rapidly growing economy, there is a significant requirement to generate funds that can support the financial needs and facilitate consistent expansion. The study helps banks and governments create programs like financial management courses to improve financial knowledge and encourage people to make wise financial decisions in the stock market. This would help boost the involvement of individual investors in developing countries with low financial literacy rates. Therefore, it is necessary to provide a thorough framework that can assess and support individuals in improving their financial literacy levels, thereby enhancing their self-efficacy (Perry and Morris, 2005).

Our research shows that better communication about regulations and simpler processes can help reduce the tendency to avoid risks when investing. This serves as an important guideline for policymakers. Governance should be transparent to ensure that market regulators are well aware of any restrictions or punitive actions they might impose. Moreover, financial institutions must make rigorous efforts to minimize obstacles such as documentation and procedural intricacy. Promoting the usage of digital accounts for mutual funds and implementing various strategies to save paperwork could be beneficial. Financial institutions could also use the “social proof” phenomena (Schneider, 2023), in their communication to persuade investors to raise their allocation to equities products.

Conclusion and future research agenda

This research has improved our understanding of the variables affecting an individual investor’s decision to engage in financial investing. We have presented findings demonstrating that individuals’ intent to invest in equities is impacted by many psychological aspects, including perceived benefits, perceptions of regulators, subjective norms, and financial self-efficacy (FSE). This study is highly intriguing since it seeks to elucidate not only the crucial aspects that drive investing intention but also the often-overlooked significance of additional psychological factors. This study addresses the gap in prior research by emphasizing the necessity to enhance the psychological factor in order to foster investing aspirations. Variables such as the hassle factor and the desire to minimize risk have a negative impact on the investor’s intention. Additionally, considerations such as the perceived benefits and the Perception of regulators are also taken into account. This paper challenges the common belief that only those with significant financial resources can build and manage growth-efficient portfolios. It highlights the significant role of intangible assets, such as FSE, subjective norms, and deconstructed attitudinal factors like the hassle faced by individual investors, Risk Avoidance, Perceived Benefit, Perception of Regulators, and resources like financial literacy. These factors are crucial for fostering investment intentions among non-investors.

This study has the potential to provide substantial value in related research areas concerning emerging markets. The framework has the potential to serve as a foundation for future studies on investor behavior and the marketing of financial products. Although the current study adds new insights to the existing literature, it has several limitations. For instance, predicting investors’ behavioral intention is a multifaceted challenge, and it should cover all the aspects related to unforeseen human-related factors like cognitive bias, heuristics, social and herd behavior while making investment decisions. Whereas, this study is more focussed on decomposition of attitudinal factors, which also encompasses unanticipated psychological factors such as hassle factor comprises of all the difficulties and constraints an individual faces while making investment decision, risk avoidance covers the bias aspect of investing towards the asset that is less risky in nature, perceived benefit shows the value an investor intends to get while choosing an investment alternative over other and perception of regulators depicts the level of trust and faith of an investor due to vigilance of an regulatory body. So, the future work should also cover the remaining aspects. The research was done in India, which is considered an emerging market and a developing economy. To draw broad and global conclusions applicable to various cultures and countries, it is recommended to examine the recent research in other advanced economies outside of Asia. Furthermore, comparing developed and developing nations can offer valuable insights into how behavioral aspects change investment patterns in equity investments.

Another constraint of this study is that it only examined individuals’ intentions regarding equity investments. As previous research has shown that the intention to buy financial assets varies across different types, limiting the generalizability of the findings of this study. Further, other constructs of the TPB can be decomposed by scholars in future work.

Data availability

The data will be made available on request from the corresponding author, Anurag Singh rsm2021010@iiita.ac.in.

References

Abdulaziz H, Hassan A, Mahdi S (2021) Measuring students’ use of zoom application in language course based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). J Psycholinguist Res 50(4):883–900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09752-1

Adam AA, Elvia R,S (2014) Socially responsible investment in Malaysia: behavioral framework in evaluating investors’ decision making process. J Clean Prod 80:224–240

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(2):179–211

Ajzen I (2015) Consumer attitudes and behavior: the theory of planned behavior applied to food consumption decisions. Ital Rev Agric Econ 70(2):121–138. https://doi.org/10.13128/REA-18003

Ajzen, I (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195

Akhtar F, Das N (2019) Predictors of investment intention in Indian stock markets. Int J Bank Mark 37(1):97–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-08-2017-0167

Akhter T, Hoque ME (2022) Moderating effects of financial cognitive abilities and considerations on the attitude–intentions nexus of stock market participation. Int J Financ Stud 10(1):5

Ali A (2011) Predicting individual investors’ intention to invest: an experimental analysis of attitude as a mediator. Int J Hum Soc Sci 6:876–883

Almansour BY, Elkrghli S, Almansour AY (2023) Behavioral finance factors and investment decisions: a mediating role of risk perception. Cogent Econ Financ 11(2):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2239032

Almenberg J, Dreber A (2015) Gender, stock market participation and financial literacy. Econ Lett 137:140–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2015.10.009

Amatucci FM, Crawley DC (2011) Financial self-efficacy among women entrepreneurs. Int J Gend Entrep 3(1):23–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566261111114962

Anantanasuwong K, Kouwenberg R, Mitchell OS, Peijnenburg K (2024) Ambiguity attitudes for real‑world sources: field evidence from a large sample of investors. Exp Econ 27(3):548–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-024-09825-1

Ang A, Bekaert G, Liu J (2005) Why stocks may disappoint. J Financ Econ 76(3):471–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.03.009

Asebedo SD, Seay MC (2018) Financial self-efficacy and the saving behavior of older pre-retirees. J Financ Cuns Plan 29(2):357–368

Avkiran NK, Ringle CM (2018) Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Springer International Publishing

Azarmi T, Lazar D, Jeyapaul J (2011) Is the Indian stock market a casino? J Bus Econ Res 3(4). https://doi.org/10.19030/jber.v3i4.2767

Bakar A, Yakasai M, Jamaliah W, Jusoh W (2015) Testing the Theory of Planned Behavior in determining intention to use digital coupon among university students. Procedia Econ Financ 31(15):186–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01145-4

Bandura A (1978) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Adv Behav Res Ther 1(4):139–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

Bandura A (1986) The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J Soc Clin Psychol 4(3):359–373. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Bandura A (1989) Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol 44(9):1175–1184

Bandura A (2001) Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):1–26

Barber BM, Odean T (2008) All that glitters: the effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Rev Financ Stud 21(2):785–818. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhm079

Barber B, Odean T (2001) Boys will be boys: gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment*. Q J Econ 116(1):261-292

Barclay D, Higgins C, Thomson R(1995) The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: personal computer adoption and use as an illustration Technol Stud 2(2):285–309

Benartzi S, Thaler RH (1995) Myopic loss aversion and the equity premium puzzle. Q J Econ 110(1):73–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118511

Bertoldo R, Castro P (2016) The outer influence inside us: exploring the relation between social and personal norms. Resour Conserv Recycl 112:45–53

Bhardwaj RK (2017) Gender perception in the development of online legal information system for the Indian environment. Bottom Line 30(2):90–119. https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-03-2017-0005

Bogan V (2008) Stock market participation and the internet. J Financ Quant Anal 43(1):191–211. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022109000002799

Calvet L, Celerier C, Sodini P, Vallee B (2016) Financial innovation and stock market participation. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2788897

Calvet LE, Campbell JY (2009) Measuring the financial sophistication of households. Am Econ Rev 99(2):393–398

Chan C, Chan A (2011) Attitude toward wealth management services: implications for international banks in China. Int J Bank Mark 29(4):272–292. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652321111145925

Chatterjee S, Finke M, Harness N (2011) The impact of self-efficacy on wealth accumulation and portfolio choice. Appl Econ Lett 18(7):627–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851003761830

Chen CF, Tsai DC (2007) How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour Manag 28(4):1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.07.007

Choi Y, Park J (2020) Investigating factors influencing the behavioral intention of online duty-free shop users. Sustainability 12(17):1–20

Christiansen C, Joensen JS, Rangvid J (2008) Are economists more likely to hold stocks? Rev Financ 12(3):465–496. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfm026

Cuong PK, Jian Z (2014) Factors influencing individual investor behavior: an empirical study of the Vietnamese stock market. Am J Bus Manag 3(2):77–94. https://doi.org/10.11634/216796061403527

Davis FD (1989) Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q: Manag Inf Syst 13(3):319–339. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

de Vries G, Rietkerk M, Kooger R (2020) The hassle factor as a psychological barrier to a green home. J Consum Policy 43(2):345–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-019-09410-7

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2008) Self-determination theory: a macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can Psychol 49(3):182–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801

Demarque C, Charalambides L, Hilton DJ, Waroquier L (2015) Nudging sustainable consumption: the use of descriptive norms to promote a minority behavior in a realistic online shopping environment. J Environ Psychol 43:166–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.06.008

Dorn D, Huberman G (2010) Preferred risk habitat of individual investors. J Financ Econ 97(1):155–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.03.013

Durand RB, Newby R, Sanghani J (2008) An intimate portrait of the individual investor. J Behav Financ 9(4):193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560802341020

Dwivedi YK, Rana NP, Jeyaraj A, Clement M, Williams MD (2019) Re-examining the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT): towards a revised theoretical model. Inf Syst Front 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-017-9774-y

Feng L, Seasholes MS (2008) Individual investors and gender similarities in an emerging stock market. Pac Basin Financ J 16:44–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2007.04.003

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Beliefs, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research, vol 27, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley

Fong KK-K, Wong SKS (2015) Factors influencing the behavior intention of mobile commerce service users: an exploratory study in Hong Kong. Int J Bus Manag 10(7). https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v10n7p39

Forbes J, Kara SM (2010) Confidence mediates how investment knowledge influences investing self-efficacy. J Econ Psychol 31(3):435–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2010.01.012

Fu X (2021) A novel perspective to enhance the role of TPB in predicting green travel: the moderation of affective–cognitive congruence of attitudes. Transportation 48(6):3013–3035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-020-10153-5

Giné X, Townsend R, Vickery J (2008) Patterns of rainfall insurance participation in rural India. World Bank Econ Rev 22(3):539–566. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhn015

Gopi M, Ramayah T (2007) Applicability of theory of planned behavior in predicting intention to trade online: some evidence from a developing country. Int J Emerg Mark 2(4):348–360. https://doi.org/10.1108/17468800710824509

Graham-rowe E, Jessop DC, Sparks P (2015) Resources, conservation and recycling predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Resour Conserv Recycl 101:194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.05.020

Grayson K, Johnson D, Chen DR, Grayson K, Johnson D, Chen DR(2008) Is firm trust essential in a trusted environment? How trust in the business context influences customers J Mark Res 45(2):241–256

Grinblatt M, Keloharju M, Linnainmaa J (2011) IQ and stock market participation. J Financ 66(6):2121–2164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01701.x

Guiso L, Jappelli T (2005) Awareness and stock market participation. Rev Financ 9(4):537–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10679-005-5000-8

Guiso L, Sodini P (2013) Household finance: an emerging field. In: Handbook of the economics of finance, (Harris GM, Stulz R. eds.) vol 2, Issue PB. Elsevier B.V

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Practice 37–41. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hansen T (2012) Understanding trust in financial services: the influence of financial healthiness, knowledge, and satisfaction. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670512439105

Hardyck JA (1965) Review reviewed work (s): when prophecy fails by Leon Festinger, Henry W. Riecken and Stanley Schachter. Review by: Jane Allyn Hardyck Published by: Religious Research Association, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3510184 JSTOR is a no. Rev Relig Res 6(2), 14–17

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2016) Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int Mark Rev 33(3):405-431

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR (2009) The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. N Chall Int Mark 20:277–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

Hong S, Thong JYL, Yan K (2006) Understanding continued information technology usage behavior: a comparison of three models in the context of mobile internet. Decis Support Syst 42:1819–1834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2006.03.009

Husnain B, Zulfiqar S, Shah A, Fatima T (2019) Effect of neuroticism, conscientiousness on investment decisions. Mediation analysis of financial self-efficacy. City Univ Res J 09(01):15–26

Jain J, Walia N, Gupta S (2020) Evaluation of behavioral biases affecting investment decision making of individual equity investors by fuzzy analytic hierarchy process. Rev Behav Financ 12(3):297–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-03-2019-0044

Jain R, Sharma D (2022) Investor personality as a predictor of investment intention—mediating role of overconfidence bias and financial literacy. Int J Emerg Mark 1979. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-12-2021-1885

Jang SY, Chung JY, Kim YG (2014) Effects of environmentally friendly perceptions on customers’ intentions to visit environmentally friendly restaurants: an extended theory of planned behavior. Asia Pac J Tour 2015:37–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2014.923923

Kahneman BYD, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. World Sci Handb Financ Econ Ser 47(2):263–291

Khan S (2016) Impact of financial literacy, financial knowledge, moderating role of risk perception on investment decision. Muhammad Ali Jinnah University Islamabad, Campus, pp 1–20

Kim HW, Chan HC, Gupta S (2007) Value-based adoption of mobile internet: an empirical investigation. Decis Support Syst 43(1):111–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2005.05.009

Kline RB (2018) Response to Leslie Hayduk’s review of principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th edition. Can Stud Popul 45(3–4):188–195. https://doi.org/10.25336/csp29418

Kraft P, Rise J, Sutton S, Røysamb E (2005) Perceived difficulty in the theory of planned behaviour: perceived behavioural control or affective attitude? Br J Soc Psychol 44(3):479–496. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466604X17533

Lai C (2019) Personality traits and stock investment of individuals. Sustainability 11(19):5474

Levine MR (2021) Finance, growth, and inequality. International Monetary Fund

Lown JM (2011) Development and validation of a financial self-efficacy scale. J Financ Couns Plan 22(2):54–63

Luis J, Robledo R, Arán MV (2015) The moderating role of gender on entrepreneurial intentions. Intang Cap 11(1):92–117

Lusardi A, Mitchell OS (2013) The economic importance of financial literacy. J Econ Lit 52(1):65

Lusardi A, Tufano P (2015) Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. J Pension—Econ Financ 14(4):332–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747215000232

Mahmood F, Arshad R, Khan S, Afzal A, Bashir M (2024) Impact of behavioral biases on investment decisions and the moderation effect of financial literacy: an evidence of Pakistan. Acta Psychol 247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104303

Maichum K, Parichatnon S, Peng K (2016) Application of the extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to investigate purchase intention of green products among Thai consumers. pp 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101077

Matthews L (2017) Applying multigroup analysis in PLS-SEM: a step-by-step process. In: Partial least squares path modeling: basic concepts, methodological issues and applications. (Hengky L., Richard N. eds.) Springer, pp 219–243

Metawa SA, Almossawi M (1998) Banking behavior of Islamic bank customers: perspectives and implications. Int J Bank Mark 16(7):299–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652329810246028

Mindra R, Moya M, Zuze LT, Kodongo O (2017) Financial self-efficacy: a determinant of financial inclusion. Int J Bank Mark 35(3):338–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-05-2016-0065

Mishra A, Maheswarappa SS, Maity M, Samu S (2018) Adolescent’s eWOM intentions: an investigation into the roles of peers, the Internet and gender. J Bus Res 86:394–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.04.005

Monecke A, Leisch F (2012) semPLS: structural equation modeling using partial least squares. J Stat Softw 48(3):1–32

Montford W, Goldsmith RE (2016) How gender and financial self-efficacy influence investment risk taking. Int J Consum Stud 40:101–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12219

Nadeem MA, Ali M, Qamar J, Nazir MS, Ahmad I, Timoshin A, Shehzad K (2020) How investors attitudes shape stock market participation in the presence of financial self-efficacy. Front Psychol 11:1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.553351

Neufeld D (2023) The $109 trillion global stock market in one chart. Visual Capital. https://advisor.visualcapitalist.com/the-109-trillion-global-stock-market-in-one-chart/

Ng L, Wu F (2006) Revealed stock preferences of individual investors: evidence from Chinese equity markets. Pac Basin Financ J 14(2):175–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2005.10.001

Perry VG, Morris MD (2005) Who is in control? The role of self-perception, knowledge, and income in explaining consumer financial behavior. J Consum Aff 39(2):299–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2005.00016.x

PTI (2023) Indian equity market enters coveted USD 4-trillion market cap club for first time. Econ Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/indian-equity-market-enters-coveted-usd-4-trillion-market-cap-club-for-first-time/articleshow/105582848.cms?from=mdr

Rahman M, Lesch MF, Horrey WJ, Strawderman L (2017) Assessing the utility of TAM, TPB, and UTAUT for advanced driver assistance systems. Accid Anal Prev 108(June):361–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2017.09.011

Raju PS (1980) Optimum stimulation level: its relationship to personality, demographics, and exploratory behavior. J Consum Res 7(3):272–282

Ramayah T, Cheah J-H, Chuah F, Ting H, Memon M (2016) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0: an updated and practical guide to statistical analysis, 1(1):1-72, Pearson

Ramayah T, Rouibah K, Gopi M, Rangel GJ (2009) A decomposed theory of reasoned action to explain intention to use Internet stock trading among Malaysian investors. Comput Hum Behav 25(6):1222–1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.06.007

Ramayah T, Yusoff YM, Jamaludin N, Ibrahim A (2009) Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to predict Internet tax filing intentions. Int J Manag 26(2):272–284

Rana K, Poudel P (2023) Qualitative methodology in translational health research: current practices and future directions. Healthcare 11(19):1–16

Raut RK (2018) Behaviour of individual investors in stock market trading: evidence from India. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150918778915

Raut RK (2020) Past behaviour, financial literacy and investment decision-making process of individual investors. Int J Emerg Mark 15(6):1243–1263. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-07-2018-0379

Raut RK, Kumar R, Das N (2021) Individual investors ’ intention towards SRI in India: an implementation of the theory of reasoned action. Soc Responsib J 17(7), 877–896. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-02-2018-0052

Ricciardi V (2007) A literature review of risk perception studies in behavioral finance: the emerging issues. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.988342

Ricciardi V, Rice D (2014) Risk perception and risk tolerance. In: Investor behavior: the psychology of financial planning and investing. (Kent Baker H., Victor R. eds.), wiley, pp 327–345

Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Mitchell R, Gudergan SP (2020) Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int J Hum Resour Manag 31(12):1617–1643. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1416655

Roldán JL, Sánchez-Franco MJ (2012) Variance-based structural equation modeling: guidelines for using partial least squares in information systems research. In: Research methodologies, innovations and philosophies in software systems engineering and information systems, Christian Homburg, Martin Klarmann, Arnd Vomberg, Springer IGI Global

Roy R, Akhtar F, Das N (2017) Entrepreneurial intention among science & technology students in India: extending the theory of planned behavior. Int Entrep Manag J 13(4):1013–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0434-y

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2020) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp Educ Psychol 61(April):101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Hair JF (2021) Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In: Handbook of market research, (Christian H, Martin K, Arnd V. eds.) pp. 587–632, Springer International Publishing

Savari M, Gharechaee H (2020) Utilizing the theory of planned behavior to predict Iranian farmers’ intention for safe use of chemical fertilizers. J Clean Prod 121512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121512

Schneider PT (2023) Social proof is ineffective at spurring costly pro-environmental household investments. Online J Commun Media Technol 13(4)

Simon HA (1955) A behavioral model of rational choice. Q J Econ 69(1):99–118. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1884852

Sivaramakrishnan S, Srivastava M, Rastogi A (2017) Attitudinal factors, financial literacy, and stock market participation. Int J Bank Mark 35(5):818–841. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-01-2016-0012

Snyder CR, Lopez SJ (2012) The Oxford handbook of positive psychology, 2nd edn, Oxford university press

Tamara D (2020) The intention to invest in retail bonds in Indonesia. IDX 9(5):188–205

Tauni MZ, Fang HX, Iqbal A (2017) The role of financial advice and word-of-mouth communication on the association between investor personality and stock trading behavior: evidence from Chinese stock market. Personal Individ Differ 108:55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.048

Taylor S, Todd PA (1995) Understanding information technology usage: a test of competing models. Inf Syst Res 6(2):144–176

Tingchi Liu M, Brock JL, Cheng Shi G, Chu R, Tseng TH (2013) Perceived benefits, perceived risk, and trust: influences on consumers’ group buying behaviour. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 25(2):225–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/13555851311314031

Toft MB, Schuitema G, Thøgersen J (2014) Responsible technology acceptance: model development and application to consumer acceptance of Smart Grid technology. Appl Energy 134:392–400

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1974) Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science 185(4157):1124–1131

Uttley J (2019) Power analysis, sample size, and assessment of statistical assumptions—improving the evidential value of lighting research. LEUKOS—J Illum Eng Soc North Am 15(2–3):143–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/15502724.2018.1533851

van Rooij M, Lusardi A, Alessie R (2011) Financial literacy and stock market participation. J Financ Econ 101(2):449–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.006

Venkatesh V, Davis FD (2000) Theoretical extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: four longitudinal field studies. Manag Sci 46(2):186–204. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926

Venkatesh V, Morris MG, Davis GB, Davis FD (2003) User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Q: Manag Inf Syst 27(3):425–478

Wang S, Jiang J, Zhou Y, Li J, Zhao D (2020) Climate-change information, health-risk perception and residents’ environmental complaint behavior: an empirical study in China. Environ Geochem Health 42(3):719–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-018-0235-4

Wu X, Kuang W (2021) Exploring influence factors of WeChat users’ health information sharing behavior: based on an integrated model of TPB, UGT and SCT. Int J Hum–Comput Interact 37(13):1243–1255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2021.1876358

Xia Y, Rasool G, Id M (2024) Unleashing the behavioral factors affecting the decision making of Chinese investors in stock markets. PLoS ONE 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298797

Xie K, Vongkulluksn VW, Heddy BC, Jiang Z (2024) Experience sampling methodology and technology: an approach for examining situational, longitudinal, and multi-dimensional characteristics of engagement. Educ Technol Res Dev 72(5):2585–2615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-023-10259-4

Xu Z, Li J, Shan J, Zhang W (2021) Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand residents ’ coping behaviors for reducing the health risks posed by haze pollution. Environ Dev Sustain 23(2):2122–2142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00666-5

Yadav R, Pathak GS (2016) Intention to purchase organic food among young consumers: evidences from a developing nation. Appetite 96:122–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.017

Yang M, Al Mamun A, Mohiuddin M, Al-shami SSA, Zainol NR (2021) Predicting stock market investment intention and behavior among Malaysian working adults using partial least squares structural equation modeling. Mathematics (2227–7390) 9(8):873

Zulfiqar S, Shah A, Ahmad M, Mahmood F (2018) Heuristic biases in investment decision-making and perceived market efficiency: a survey at the Pakistan stock exchange. Qual Res Financ Mark 10(1):85–110. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRFM-04-2017-0033

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. UG: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision. SK: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision. AJ: Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The survey questionnaire and methodology were examined, approved, and endorsed by the doctoral committee of the Department of Management Studies, Indian Institute of Information Technology, Allahabad, India, on 3 July 2024. The procedures used in this study adhere to the ethical standards set out in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study in August 2024. Participants were required to complete an online informed consent process. During this process, participants were clearly informed about the following key aspects: (i) confidentiality, wherein personal information provided by the participants would remain confidential and would not be published or disclosed, and (ii) use of data, wherein the data collected from the participants would be exclusively used for academic research purposes and not for any commercial activities. In order to continue to participate in the study, participants had to carefully read the instructions at the beginning and click the “agree and continue” button before formally filling out the questionnaire, an action that amounted to their agreeing to participate and allowing them to fill out the questionnaire.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, A., Goel, U., Kumar, S. et al. Unveiling the attitudinal factors: an integration of TPB and SCT in understanding investor intention towards equity investments. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1516 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05478-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05478-4