Abstract

This study examined the correlation between using elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging in Chinese older adults, while also exploring the potential mediating effect of adult children’s support in this relationship. The analysis utilized data from the 2014 China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey, a comprehensive survey conducted nationwide among individuals aged 60+ years in China (N = 7102). Regressions were performed using PROCESS v3.3 for SPSS 20.0. Results showed that using elderly privilege program was significantly correlated with positive attitudes toward aging (b = 0.329, p < 0.05), and financial support (b = 0.024, BCa CI [0.005, 0.048]) from children mediated the relationship. The findings suggested that to maintain positive attitudes toward aging in Chinese older adults, both elderly privilege program and support from adult children are encouraged. Our findings may enhance existing theories and understanding, and have potential implications for policies and interventions in social work for Chinese older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

By the end of 2023, China had 216.76 million older adults who were 65 years old and above, making up 15.4% of the overall population (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2024). With the increasing elderly population, researchers have been more focused on successful aging, particularly the crucial role of older adults’ attitudes toward aging. Many studies have proved that more positive attitudes toward aging appear to serve as a safeguard for physical and mental health in late adulthood (Korkmaz Aslan et al., (2017); Martin et al., 2019). Therefore, positive attitudes toward aging are the crucial determinant that can help older adults adjust to aging and promote successful aging (Chang, et al., 2015).

Older adults’ attitudes toward aging are influenced by various personal and social factors. Personal factors, such as health status and personality traits, play a significant role (Park & Hess, 2020), while social factors, including social support and environmental influences, also contribute (Miche et al., 2014). In accordance with the stereotype embodiment theory, the cultural context and living environment of older adults shape their perceptions of aging (Levy, 2009). On the basis of the theory, getting more social support and having higher levels of satisfaction with social support may be important indicators for older adults having more positive attitudes toward aging (Park et al., 2015; Lamont et al., 2017). Elderly privilege program is an important component of social welfare for Chinese older adults as well as an important part of their rights. This government-sponsored program is designed to offer older adults free or prioritized access to public transportation, parks, tourist attractions, and various public facilities and services. Research has shown that participation in elderly privilege program and the leisure activities the program offers positively influence the life satisfaction of Chinese older adults (Tao & Li, 2016; Wang, 2011), while also lowering the risk of mental health issues (Yuan & Shen, 2016). However, as an important social support for older adults, its association on positive attitudes toward aging has received little attention. It also remains unknown through what mechanism that using elderly privilege program was associated with positive aging attitudes. Therefore, understanding how elderly privilege program affects positive aging attitudes among older adults and whether there are ways to strengthen the effect is essential for protecting older adults’ mental health and promoting successful aging.

Support from adult children primarily includes three dimensions: financial support, instrumental support, and emotional support (Peng et al., 2015). Support from adult children is also regarded as a key social support modality for older adults, and existing studies have revealed that support from children had a notably beneficial effect on positive attitudes toward aging among older adults (Sun, 2017; Wu & Li, 2019). Support from adult children is theoretically hypothesized to be a crucial factor in the relationship between elderly privilege program and older adults’ positive aging attitudes. However, few research tested the mediating mechanism of adult children’s support among Chinese older adults.

To address the research gap, this study had two primary objectives: (1) to assess whether using elderly privilege program was a positive predictor of positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults, and (2) to examine how adult children’s support mediated the link.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis

Theoretical framework

Social support theory posits that social networks can provide individuals with emotional, material, and informational support when facing pressure and challenges in life, enhancing mental well-being through both direct and buffering effects. Social support plays a crucial role in buffering individuals from the potentially harmful effects of stressful experiences (Cohen & Wills, 1985), including stress related to aging, such as declining physical health and a shrinking social network. It serves as a protective factor by mitigating stress-related threats to self-esteem and feelings of helplessness while also providing a compensatory function (Cohen & Wills, 1985). This indicates that social support can help older adults navigate uncertainty, achieve positive outcomes, and regain a sense of control and self-worth that may have been diminished with age (O’Brien & Sharifian, 2020). As a result, it can contribute to a more positive perception of themselves and the aging process.

The crowding-in versus crowding-out framework helps explain how participation in government-sponsored elderly privilege program affects support from adult children. The crowding-out perspective suggests that frequent use of the program reduces older adults’ reliance on their children, while the crowding-in perspective argues that such participation may actually encourage family involvement and support (He et al., 2021). Consequently, engaging in elderly privilege program can generate new emotional and financial needs, potentially influencing whether adult children increase or decrease their support for aging parents.

Using elderly privilege program and older adults’ positive attitudes toward aging

To ensure the basic living needs of older adults in China, the government has implemented various institutional arrangements to address the weakening of traditional family support caused by modernization and industrialization. These measures include social pension and medical insurance, community-based elderly care services, and elderly privilege program. The elderly privilege program is based on older adults’ actual needs. It aims to enhance overall well-being of older adults by improving living environment, increasing access to public services, and offering economic and emotional support in areas such as healthcare, transportation, and entertainment. Friendship networks help alleviate stress and depression (Bankoff, 1983; Litwin, 2001), benefiting older adults’ mental health. However, these networks are vulnerable to erosion by stressful late-life events like widowhood and retirement (Bao et al., 2021). Social support serves as a vital system for maintaining mental well-being in older adults, closely linked to their attitudes toward aging (Rashid et al., (2014)). Elderly privilege program promotes older adults’ social interaction outside the house, helping maintain and broaden their social networks and gain social support. This enhanced social connectivity and social support can improve emotional communication and instrumental support, potentially fostering positive aging attitudes (Lamont et al., 2017).

Attitudes toward aging (or self-perceptions of aging/satisfaction with aging) in older adults encompass their cognitions and expectations regarding the aging process (Jung & Siedlecki, 2018). Attitudes toward aging are generally classified into two dimensions: positive and negative (Laidlaw et al., 2007). A positive attitude toward one’s own aging can promote successful aging among older adults (Baltes & Smith, 2003), is a strong predictor of higher level of life satisfaction (Tao & Li, 2016; Wang, 2011) and is helpful in reducing mental illness among older adults (Yuan & Shen, 2016). Therefore, it is important to examine what factors contribute to older adults’ positive attitudes toward aging. However, few studies have specifically investigated the link between using elderly privilege program and positive aging attitudes in Chinese older adults. Based on the benefits of using elderly privilege program on other aspects of older adults’ life, we proposed the hypothesis:

H1: There would be a positive association between using elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults.

Support from adult children and older adults’ positive attitudes toward aging

Previous studies mainly examined how adult children’s support influenced older adults’ mental health. Substantial evidence indicates that financial support from children significantly enhances parental life satisfaction (Silverstein et al., 2006b; Lin et al., 2011). More emotional support from children could improve psychological well-being of older adults (Silverstein et al., 2006a), and instrumental support from children was helpful to mitigate depression among older parents (Cong & Silverstein, 2008). However, Abolfathi Momtaz et al. (2014) found that excessive support (financial, care, and concern) from adult children could compromise older adults’ self-esteem and well-being. Because it made older adults feel that they were useless and became a burden for their children.

Relatively limited research has explored the influence of support from adult children on older adults’ positive aging attitudes. One study showed that children’s support significantly enhanced positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults, with emotional support being strongest, followed by instrumental and financial support (Sun, 2017). Another study categorized older adults’ attitudes toward aging into three types (psychological loss, positive psychological acquisition, and coping with body changes with aging), and found that emotional and instrumental support from children were helpful to promote positive psychological acquisition among older adults, and emotional support also had a positive effect on coping with body changes with aging among older adults (Wu & Li, 2019). Therefore, researchers generally believe that adult children’s support enhances positive aging attitudes among older adults. This effect is largely rooted in filial piety—a traditional cultural obligation for Chinese children to respect and take care of their parents (Silverstein et al., 2006b)—and the institutional norm, legally mandated in China, of adult children supporting their older parents. Chinese older adults mainly rely on their children for old age support and usually hold high expectations on getting support from their children (Xu & Chi, 2016; Xu et al., 2017). Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H2a: Financial support from adult children would have a significant positive influence on positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults.

H2b: Instrumental support from adult children would have a significant positive influence on positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults.

H2c: Emotional support from adult children would have a significant positive influence on positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults.

The mediating role of support from adult children

Among the multiple factors that influence support from adult children, social welfare is considered as a critical factor. For example, one study showed that intergenerational support rate was lower in western countries with better social security and services for older adults (Katz, 2009). Reil-Held (2006) found that public financial transfers provided to older people in German might lead to a reduction in the private financial support they would have otherwise obtained. Jiao (2016) found that new rural social pension insurance in rural China had crowding-out effect on emotional and instrumental support from adult children. Chen and Zeng (2013) also found that the pension received by older adults increased by 1 RMB was associated with a 0.808 RMB decrease in adult children’s financial support. However, Chen et al. (2017) reported that greater social welfare provisions for older adults predicted greater financial transfers from adult children to older parents. This implies that there is a relationship between using elderly privilege program and adult children’s support. Based on the analysis, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H3a: Financial support from adult children would mediate the association between using elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults.

H3b: Instrumental support from adult children would mediate the association between using elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults.

H3c: Emotional support from adult children would mediate the correlation between using elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults.

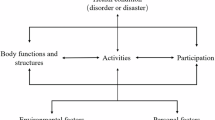

Building on hypotheses 1–3, we proposed a conceptual framework (Fig. 1) depicting the relationship between using elderly privilege program and positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults, along with the potential mediation by different forms of adult children’s support.

Methods

Sample

We used data selected from China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS), which was a nationally representative survey of older adults aged 60+ years in China. CLASS was conducted during 2014 in 29 provinces of China. The main purposes were to collect socioeconomic data on Chinese older adults by in-person interview, probe into difficulty and challenge during their aging process, and provide theoretical and practical advice in solving aging issues. CLASS was implemented by CLASS project office at Renmin University of China, regional project offices at other cooperative academical institutions and community-based graphic sampling teams and survey teams.

The CLASS employed a stratified multistage probability sampling design. The sampling procedure first selected county-level administrative divisions (counties, county-level cities, and districts), followed by village committees (rural) and residential committees (urban) as secondary sampling units. Finally, individuals aged 60 and above were chosen as survey respondents. The survey encompassed 29 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities, excluding Hong Kong, Taiwan, Macao, Hainan, Xinjiang, and Tibet, and covered 462 village or residential committees. Further details on the sampling process can be found elsewhere (He et al., 2021). The total sample consisted of 11,511 Chinese older adults. This study focused on 7102 participants who met the inclusion criteria: (1) no cognitive impairment, and (2) having at least one living adult child (age ≥18 years).

Measures

Dependent variable

The study’s dependent variable was positive attitudes toward aging. There were seven items about attitudes toward aging in CLASS questionnaire, rated on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Four items focusing on negative attitudes toward aging were first reversely recoded so that higher scores indicated more positive aging attitudes. The summative score of seven items ranged from 7 to 35, indicated an overall level of positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults, and a higher score reflected more positive attitudes.

Independent variable

The study’s independent variable was using elderly privilege program. It was measured by a question, “Have you ever used elderly privilege program in the local area? (for example, free access to public transportation and parks)” (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Mediation variable

The study’s mediation variable was support from children that included financial, instrumental, and emotional support. Financial support was measured by asking the respondents “In the past 12 months, did this child give you (or a living spouse who lives with you) cash, food or gifts, and how much was the property?” Each response was rated on a nine-point scale (1 = none, 2 = 1–199 RMB, 3 = 200–499 RMB, 4 = 500–999 RMB, 5 = 1000–1999 RMB, 6 = 2000–3999 RMB, 7 = 4000–6999 RMB, 8 = 7000–11999 RMB, and 9 = 12,000 RMB and more) (1 RMB ≈ 0.145 US dollars). Instrumental support was measured by a question, “How often did this child help you with housework in the past 12 months?” The item had a five-point scale (1 = None, 2 = A few times a year, 3 = At least once a month, 4 = At least once a week, and 5 = Almost every day). Two questions were used to measure emotional support from children: “From all aspects, do you feel emotionally close to your child?” (1 = not close, 2 = so so, 3 = close); “Do you think this child doesn’t care enough about you?” (1 = never, 2 = occasional, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often). After reversely recoded the second item, we added up the scores of two questions, and higher total score represented more emotional support from children (range = 2–7). Due to the skewness of the distribution of the sum score, it was recoded (1 to 5= not close, 6–7= close). These measures were assessed for each living child (up to five children per respondent). For respondents with multiple children, the maximum value across all children was used for each support.

Control variables

The study controlled for some demographic characteristics of older adults from CLASS, including gender (1 = male), age, marital status (1 = married with a spouse), education (0 = illiterate, 1 = primary school, 2 = junior middle school, 3 = senior high school or above), health (1 = healthy), satisfaction with life (1 = satisfied), whether had paid work at the time of survey (1 = yes), social network, total amount of alive children, whether the older adult living with family members (1 = yes), and area type of living (1 = urban area). In addition, social network was measured by standardized Lubben Social Network with 6 items (LSNS-6, Lubben et al., 2006). Total score of six questions reflected older adults’ social network, and a higher total score meant a stronger social network (range = 0–30).

Analyses

The analyses proceeded in three stages. First, descriptive statistics were conducted for all variables included in the study. Second, bivariate correlations were examined to assess significant relationships between all key variables. These initial analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0. Finally, multivariate regression analyses were conducted using PROCESS v3.3 for SPSS 20.0 (Hayes, 2012) to examine the potential mediating role of adult children’s support. To examine the mediating roles of adult children’s support, three indicators (financial, instrumental, and emotional support from children) acting as mediation variables were sequentially added into the model. This tested their potential mediation effects between using elderly privilege program and positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults. Indirect effects were estimated with 95% confidence intervals using 1000 bootstrap samples.

Results

Sample description

Sample characteristics were summarized in Table 1. Among 7102 respondents, mean age was 68.95 years (SD = 7.44, range = 60–113). Over half were men (55.15%). 72.61% of the respondents were married and living with a spouse at the time of the survey, and the rest were not married, divorced or widowed (27.39%). 17.27% of respondents were illiterate, 36.56% had attended primary school, 24.79% had attended junior middle school, and 21.38% had senior high school education or above. More than half reported that they were unhealthy (52.95%). Most respondents were satisfied with life (78.19%). A small number of respondents had paid work or activities (19.30%), or lived alone (12.10%). The mean score of older adults’ social network was 15.41 (SD = 6.44, range = 0–30). On average, the respondents had 2.72 alive children (SD = 1.40, range = 1–12). More than half lived in urban area (67.21%). 33.82% of the respondents had used elderly privilege program. The average score of positive attitudes toward aging in respondents was 19.66 (SD = 5.41, range = 7–35). The average score of financial support, instrumental support and emotional support respondents got from children was 4.62 (SD = 2.15, range = 1–9), 3.03 (SD = 1.64, range = 1–5), and 4.67 (SD = 0.83, range = 1–5), respectively.

Bivariate relationship among key variables

Bivariate correlations among key variables were presented in Table 2. Using elderly privilege program (r = 0.075, p < 0.01), financial support (r = 0.091, p < 0.01), and emotional support (r = 0.078, p < 0.01) from children were all significantly associated with more positive aging attitudes, except instrumental support from children. Using elderly privilege program was positively correlated with financial support (r = 0.094, p < 0.01) and instrumental support (r = 0.052, p < 0.01) from children, but not with emotional support from children. Financial support was positively correlated with instrumental support (r = 0.067, p < 0.01) as well as emotional support from children (r = 0.081, p < 0.01). Instrumental support and emotional support from children were significantly correlated (r = 0.135, p < 0.01).

Elderly privilege program, support from adult children and positive attitudes toward aging

Three separate regression models were estimated in PROCESS to examine the mediating roles of instrumental, financial and emotional support from adult children respectively on the relationship between using elderly privilege program and positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults. The results revealed that only adult children’s financial support significantly mediated the relationship. Based on the criteria (Hayes, 2017), the Bootstrap 95% CI contains 0 was considered as no significant mediation effects. Results of indirect effect showed that instrumental support (b = −0.0002, BCa CI [−0.0072, 0.0065]), and emotional support (b = 0.0051, BCa CI [−0.0087, 0.0215]) from adult children didn’t mediate the association. To be parsimonious, only financial support as the mediator in Table 3 was reported.

As presented in Table 3, model 1 (path c) revealed the significant association between using elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging among older adults, after controlling for sociodemographic variables (b = 0.329, p < 0.05). This indicated that using elderly privilege program was positively associated with positive aging attitudes. H1 was verified. Model 1 also reported that education (b = 0.473, p < 0.001) had a positive effect on positive aging attitudes among older adults. Model 2 (path a) examined the relationship between using elderly privilege program and adult children’s support after controlling for sociodemographic variables. It indicated that using elderly privilege program was significantly associated with more financial support from adult children (b = 0.329, p < 0.001). However, no significant associations were found between using elderly privilege program and instrumental or emotional support (not shown in Tables). Model 2 also reported that education (b = 0.230, p < 0.001) had a positive effect on adult children’s support, while income (b = −0.255, p < 0.001) exhibited a negative effect. Model 3 (path b and c’) tested the relationship among using elderly privilege program, support from adult children, and positive aging attitudes. Results revealed that adult children’s financial support (b = 0.072, p < 0.05) was positively associated with positive aging attitudes among older adults. H2a was verified. Emotional support from adult children (b = 0.287, p < 0.001) was also positively associated with positive aging attitudes among older adults (not shown in Table 3). H2c was verified. However, only after adding financial support from adult children, using elderly privilege program (b = 0.300, p < 0.05) was still significantly associated with positive aging attitudes among older adults, but was statistically reduced in size compared to the original values (b = 0.329, p < 0.05). The indirect effect also reported that adult children’s financial support (b = 0.024, BCa CI [0.005, 0.048]) mediated the association between using elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults. H3a was verified. After adding financial support from adult children, education (b = 0.457, p < 0.001) was still significantly correlated with positive aging attitudes, but was statistically reduced in size compared to original values (b = 0.473, p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study assessed the association between using elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults and investigated the mediating role of adult children’ s support in this association. We found that using elderly privilege program significantly predicted more positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults. This is consistent with the prior research that using elderly privilege program is a strong predictor of higher level of life satisfaction (Tao & Li, 2016; Wang, 2011) and is helpful in reducing mental illness among older adults (Yuan & Shen, 2016). Our findings provide empirical evidence that Chinese older adults would have more positive attitudes toward aging due to use of elderly privilege program.

We found that both adult children’s financial and emotional support were positively related to more positive aging attitudes among older adults, but instrumental support showed no significant association. This finding contrasts with some prior studies conducted in China (Sun, 2017; Wu & Li, 2019), which emphasized the importance of instrumental support from adult children in developing positive aging attitudes among older adults. The study revealed that emotional support given by adult children was positively related to higher levels of positive attitudes toward aging among older adults, which aligns with previous research (Silverstein et al., 2006a; Sun, 2017; Wu & Li, 2019). In China, filial piety represents the traditional culture that obliges children to respect and take care of their parents (Silverstein et al., 2006b). Adult children providing emotional support makes older parents feel that they are respected and concerned, which may assist them maintain positive aging attitudes. The findings help us figure out how various forms of support provided by children influence positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults.

This study further indicated that only adult children’s financial support significantly mediated the relationship between using elderly privilege program and positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults. It made contributions to the scarce research on positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults and enriched our knowledge about the mechanism of such association through adult children’s financial support. First, in line with the previous study (Chen et al., 2017), using elderly privilege program was positively correlated with financial support from adult children, which was supported by crowd-in theoretical assumption. Elderly privilege programs, which offer benefits like free access to public transportation, parks, and tourist attractions, may incentivize older adults to engage in more social activities. This increased participation could translate into greater expenditure on social entertainment, leisure tourism, and associated commercial domains. As a result, these emerging financial demands may prompt adult children to offer financial support to their aging parents. Second, adult children’s financial support was significantly associated with more positive aging attitudes among older adults, which has been found in one previous study (Sun, 2017). Adult children offering financial support to meet older parents’ needs can contribute to improving their psychological well-being (He et al., 2021), restore feelings of personal control (Krause, 1987), and fulfill older adults’ expectations for filial support. This enables older adults to perceive their children as dutiful, which may assist them maintain positive aging attitudes. Therefore, financial support from adult children becomes essential for developing positive aging attitudes among older adults.

However, neither children’s emotional support nor instrumental support mediated the relationship between the utilization of elderly privilege program and positive aging attitudes among Chinese older adults. The elderly privilege program grants older adults priority access to public facilities and services while reducing or waiving associated fees, providing them with economic benefits. As a result, participation in these programs is likely to primarily impact financial support from adult children, with minimal influence on children’s instrumental or emotional support.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. First, the analysis relied on cross-sectional data from CLASS 2014. With cross-sectional data, we can’t test true causality between using elderly privilege program, support from adult children, and positive aging attitudes among older adults. It’s possible that more positive attitudes toward aging leads to using more elderly privilege program, and there is also a chance that children’s support may affect whether older adults decide to use the elderly privilege program. Future study can use longitudinal data to investigate true causal relationship as well as track the changes of attitudes toward aging. Considering China’s vast territory, regional differences, and a large number of older adults, the sample cannot fully reflect the real situation. The results are for reference only. Second, the measurement of using elderly privilege program was quite simple. In this study, it was measured with a single question, from which we can’t get more information about the quality and quantity of elderly privilege program older adults used or their satisfaction with using this program. Similarly, measurements on support from adult children were also rough. Single question of financial or instrumental support from adult children can’t catch deep information about whether such support was needed, satisfied, etc. Lastly, endogeneity is a potential issue in this study and future study can use instrumental variables estimation or propensity score matching to detect potential endogeneity issues.

Theoretical contributions and practical implications

Despite those limitations, this study made some theoretical contributions. The conclusion of this study extends existing social support theory, revealing that using elderly privilege program can strengthen positive aging attitudes among older adults. This conclusion also enriches existing intergenerational relationship theory, revealing the association between adult children’s financial support, emotional support, and positive aging attitudes among older adults, and further revealing the mediating role of adult children’s financial support in the relationship between using the elderly privilege program and positive aging attitudes among older adults.

This study also had some implications for gerontological social workers and adult children in facilitating older adults’ maintenance of positive aging attitudes and achieving successful aging. As mentioned earlier, positive attitudes toward aging were the key factor in facilitating successful aging (Chang et al., 2015), which could be beneficial to keep older adults in good psychological and physical health (Bryant et al., 2012) and make them feel more satisfied with life (Suh et al., 2012). Therefore, promoting more positive attitudes toward aging is important for older adults. Encouraging Chinese older adults to use the elderly privilege program will be one of the effective strategies. As the aging population increases rapidly in China, gerontological social workers can advocate for more social services and supports for older adults and a more friendly society with older adults, which will make older adults feel respected, give them increased opportunities for social engagement, and assist them in keeping more positive aging attitudes.

In addition, promoting adult children’s financial support is another important strategy, as this study found that financial support mediated the relationship between using the elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults. Caring for older adults is one important part of Chinese tradition, as well as the legal duty of children. In general, providing financial support represents a direct and common way for children to fulfill caregiving responsibilities for older adults. It can fulfill older adults’ expectations of getting support from children and make them feel that their children respect them, which helps older adults maintain positive aging attitudes. Besides, financial support from children can also help older adults enhance their quality of life and take part in meaningful social interactions, which contributes to fostering more positive aging attitudes. So, gerontological social workers should continue to advocate and promote the tradition of filial piety and encourage adult children to give increased support to their older parents. Both society and adult children should cooperate to assist older adults in maintaining positive attitudes toward aging.

Data availability

The data underlying this study’s findings can be accessed on the China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS) website at http://class.ruc.edu.cn/. Researchers interested in using this survey data should contact the China Survey Data Center at Renmin University of China (email: class@nsrcruc.org). Additionally, the dataset generated and/or analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abolfathi Momtaz Y, Ibrahim R, Hamid TA (2014) The impact of giving support to others on older adults’ perceived health status. Psychogeriatrics 14(1):31–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12036

Baltes PB, Smith J (2003) New frontiers in the future of aging: from successful aging of the young old to the Dilemmas of the Fourth Age. Gerontology 49(2):123–135. https://doi.org/10.1159/000067946

Bankoff EA (1983) Social support and adaptation to Widowhood. J Marriage Fam 45(4):827–839. https://doi.org/10.2307/351795

Bao L, Li WT, Zhong BL (2021) Feelings of loneliness and mental health needs and services utilization among Chinese residents during the COVID-19 epidemic. Global Health 17(1):51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00704-5

Bryant C, Bei B, Gilson K, Komiti A, Jackson H, Judd F (2012) The relationship between attitudes to aging and physical and mental health in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 24:1674–1683. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610212000774

Chang W, Toh Y, Fan Q, Chan A (2015) Mind over body: positive attitude and flexible control beliefs on positive aging. Biophilia 3:253–261. https://doi.org/10.14813/ibra.2015.254

Chen, H, & Zeng, Y (2013). Who benefits more from the new rural society endowment insurance program in China: elderly or their adult children? Econ Res J, (8), 55–67. (In Chinese)

Chen J, Ren Q, Jordan L (2017) Motivational perspective and crowding-in effects of intergenerational financial support: data analysis for Guangdong, Liaoning and Gansu Provinces. J East China Univ Sci Technol 1:10–21. (In Chinese)

Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98:310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Cong Z, Silverstein M (2008) Intergenerational support and depression among elders in rural China: do daughters‐in‐law matter? J Marriage Fam 70:599–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00508.x

Hayes, AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford publications

Hayes, AF (2012). PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

He H, Xu L, Fields NL (2021) Pension and depressive symptoms of older adults in China: the mediating role of intergenerational support. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(7):3725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073725

Jiao N (2016) Does public pension affect intergenerational support in rural China? Popul Res 40:88–102. (In Chinese)

Jung S, Siedlecki KL (2018) Attitude toward own aging: age invariance and construct validity across middle-aged, young-old, and old-old adults. J Adult Dev 25(2):141–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-018-9283-3

Katz R (2009) Intergenerational family relations and subjective well-being in old age: a cross-national study. Eur J Ageing 6:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-009-0113-0

Korkmaz Aslan G, Kartal A, Özen Çınar İ, Koştu N (2017) The relationship between attitudes toward aging and health-promoting behaviours in older adults. Int J Nurs Pract 23:e12594. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12594

Krause N (1987) Understanding the stress process: linking social support with locus of control beliefs. J Gerontol 42:589–893. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/42.6.589

Laidlaw K, Power M, Schmidt S (2007) The attitudes to ageing questionnaire (AAQ): development and psychometric properties. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22:367–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1683

Lamont RA, Nelis SM, Quinn C, Clare L (2017) Social support and attitudes to aging in later life. Int J Aging Hum Dev 84:109–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415016668351

Levy B (2009) Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 18(6):332–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x

Lin JP, Chang TF, Huang CH (2011) Intergenerational relations and life satisfaction among older women in Taiwan. Int J Soc Welf 20:S47–S58

Litwin H (2001) Social network type and morale in old age. Gerontologist 41(4):516. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.4.516

Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, IIiffe S, von Renteln Kruse W, Beck JC, Stuck AE (2006) Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network scale among three European Community–dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 46(4):503–513

Martin A, Eglit MLG, Maldonado Y, Daly R, Liu J, Tu X, Jeste VD (2019) Attitude toward own aging among older adults: implications for cancer prevention. Gerontologist 59:S38–S49. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz039

Miche M, Elsässer VC, Schilling OK, Wahl HW (2014) Attitude toward own aging in midlife and early old age over a 12-year period: examination of measurement equivalence and developmental trajectories. Psychol Aging 29(3):588. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037259

National Bureau of Statistics. (2024). Available online at: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2024/indexch.htm (Accessed 20 September 2024)

Park J, Hess TM (2020) The effects of personality and aging attitudes on well-being in different life domains. Aging Ment health 24(12):2063–2072

Park NS, Jang Y, Lee BS, Chiriboga DA, Molinari V (2015) Correlates of attitudes toward personal aging in older assisted living residents. J Gerontol Soc Work 58:232–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2014.978926

Peng H, Mao X, Lai D (2015) East or West, home is the best: effect of intergenerational and social support on the subjective well-being of older adults: a comparison between migrants and local residents in Shenzhen, China. Ageing Int 40:376–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-015-9234-2

Rashid A, Azizah M, Rohana S (2014) The attitudes to ageing and the influence of social support on it. Br J Med Med Res 4:5462–5473. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJMMR/2014/10023

Reil-Held A (2006) Crowding out or crowding in? Public and private transfers in Germany. Eur J Popul 22:263–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-006-9001-x

Silverstein M, Cong Z, Li S (2006a) Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: consequences for psychological well-being. J Gerontology: Ser B 61:S256–S266. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.5.S256

Silverstein M, Gans D, Yang FM (2006b) Intergenerational support to aging parents: the role of norms and needs. J Fam Issues 27:1068–1084. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X06288120

Suh S, Choi H, Lee C, Cha M, Jo I (2012) Association between knowledge and attitude about aging and life satisfaction among older Koreans. Asian Nurs Res 6:96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2012.07.002

Sun J (2017) The influence of children’s intergenerational support on the attitudes toward personal aging of the elderly-an analysis based on the CLASS 2014. Popul Dev 23:86–95. (In Chinese)

Tao T, Li L (2016) Leisure time arrangement of urban elderly and its impact on health. Popul J 38:58–66. https://doi.org/10.16405/j.cnki.1004-129X.2016.03.006. (In Chinese)

Wang L (2011) Analysis on leisure activity participation of Chinese elderly people and its influencing factors. Northwest Popul J 32:35–42. https://doi.org/10.15884/j.cnki.issn.1007-0672.2011.03.004. (In Chinese)

Wu F, Li X (2019) Impact of intergenerational support and sociodemographic characteristics on attitudes toward aging in the urban community-dwelling elderly. J Nurs Sci 12:1–4. https://doi.org/10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2019.12.001. (In Chinese)

Xu L, Chi I (2016) Grandparenting caregiving and self-rated health: a longitudinal study using latent difference score analysis. J Gerontol Geriatr Res 5(5):1–7. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-7182.1000351

Xu L, Li Y, Min J, Chi I (2017) Worry about not having a caregiver and depressive symptoms among widowed older adults in China: the role of family support. Aging Ment Health 21(8):879–888. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1181708

Yuan T, Shen G (2016) The mental health effect of the reconstruction of the rural elderly welfare supply system. J Northwest Univ 46:126–134. https://doi.org/10.16152/j.cnki.xdxbsk.2016-06-017. (In Chinese)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LX designed and supervised the study. LZ performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors substantially contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

This study utilized a publicly available dataset and conducted a secondary data analysis. Therefore, informed consent from participants was not required, nor was approval from the Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent

In the data collection of the CLASS (China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey) survey, all participants signed the informed consent at the time of participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, L., Xu, L. Using elderly privilege program and positive attitudes toward aging among Chinese older adults: the mediating role of support from adult children. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1155 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05514-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05514-3