Abstract

The analysis of scientific policies on rare diseases provides insights into the evolving dynamics in health systems. This study aims to understand the growing importance of societal influence in the development of policy standards, particularly those related to rare diseases. Adopting a socio-historical approach, the research will examine the various processes of institutionalization in rare disease research. The objective is to gain an in-depth understanding of the institutionalization of rare diseases as a socio-biomedical phenomenon. From this perspective, this study will analyze the main actors involved in this process, along with paradigmatic regulatory examples in Europe and Spain. The research will take an interdisciplinary approach, addressing the social, historical and biomedical aspects as a whole, with a focus on key stakeholders. Identifying these stakeholders is of paramount importance to understanding how the health system is currently being transformed by associationism and the influence of these organizations on political forces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When discussing rare diseases, we refer to a complex concept that is difficult to define. The term “rare” highlights the only common feature shared among all conditions under this category: their epidemiological infrequency. The concept of rare disease in Europe is defined mainly by the European Commission based on the prevalence of the disease in the population. According to Regulation (EC) No. 141/2000 of the European Parliament and of the Council, a rare disease is one that affects fewer than 5 in 10,000 people in the general population (Regulation (EC) No. 141/2000).

In recent years, biomedical knowledge about some of these conditions has advanced, while social and human research is still relatively limited. The concept of rare diseases was clearly and concisely introduced by Holtzman (1978) when he coined this term in an article on inherited metabolic disease. However, the concept was already in use within the scientific community. In fact, Fry (1962), had already highlighted unusual elements in his work “Presenting Symptoms in Childhood”, when referring to the symptoms of diseases. Likewise, Schwarz-Tiene (1960) published an article entitled “Rare metabolic diseases” in the journal Minerva pediatrica. However, he did not achieve the same consolidation of the concept as Holtzman (1978), who successfully recognized the epistemological challenges associated with this type of conditions and began to demand a modification in the teaching processes of physicians, which, in his opinion, were insufficient in relation to such diseases. Until then, the term “rare” was linked to specific cases, and few known, rather than conditions with low prevalence. Knox (1971), in this sense, published an article analyzing the prevalence of various diseases as a function of space, time and space-time interaction. He concludes that diseases with sporadic epidemic properties are considered rare.

Until the late seventies and early eighties, the concept of RD did not have a specific place in the world of knowledge as we understand it today. Until then, there was only a previous biomedical correlation. It was necessary to wait a few years for a political correlation to gradually emerge. This process led to the generation of political and social institutions, thanks in part to the social communities formed around this issue and the existing biomedical knowledge.

Research on Rare Disease policies presents a high degree of complexity, as it involves multiple stakeholders, conflicting interests, and structural challenges in policy formulation and implementation. Given this complexity, it is essential to adopt an integrative theoretical approach that enables a comprehensive analysis of the phenomenon from multiple complementary perspectives. For this reason, it is necessary to introduce various perspectives that have emerged in recent history—advances that allow for a better understanding of how the current conception of society has been shaped, particularly regarding the significant impact of participation and social mobilization on policymaking. In our case, we will analyze this in relation to rare diseases (RDs). As we will see in this article, the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) is relevant for understanding how various interest groups—including patients, civil society organizations, researchers, and policymakers—form strategic alliances to influence decision-making, particularly in a context where scientific knowledge is limited and policies must adapt to evolving demands. In this sense, the importance of associationism will be evident throughout the text. This refers to the practice of forming associations for individuals affected by various RDs. These organizations are established with the objective of advocating for rights that they frequently perceive as being restricted.

At the same time, Ronald Inglehart’s (1977) value change theory provides a broader societal perspective, explaining how the shift toward post-materialist values has fostered increased concern for health equity and patient rights, thereby facilitating the inclusion of RDs in the public agenda. These post-materialist values are related to the well-known sociological phenomenon of reflexivity. This phenomenon refers to the increase in reflection and self-questioning on the part of citizens in more advanced societies. This increased reflexivity has contributed to the growth of social movements and associations, which are a hallmark of modernity.

However, beyond institutional design, co-production highlights the need to actively involving patients and their families in knowledge production and policymaking to ensure that the measures adopted are both effective and responsive to their actual needs.

We will see that during the 20th century this participation was not as relevant as it is today, but it marked a before and after in the generation of health policies. This participatory dimension not only reinforces policy legitimacy but also intersects with social movement theory, which elucidates how advocacy groups have successfully framed RDs as a social justice issue, mobilizing resources and pressuring governments to improve access to diagnosis, treatment, and funding. Finally, to address fragmentation in decision-making and ensure that policies are both inclusive and sustainable, it is imperative to incorporate democratic innovation mechanisms, such as deliberative forums, citizen consultations, and participatory governance models, which help balance stakeholder interests and strengthen the legitimacy of the policy process. Taken together, these theoretical perspectives not only provide a robust analytical framework for understanding the complexity of rare disease policymaking but also underscore the importance of integrating participatory approaches and social transformations to develop more equitable and sustainable policy solutions. At this point, sociology has provided indirect knowledge that is useful for clarifying some aspects related to this socio-historical evolution. Hence, in this initial approach, some insights determined by Ferdinand Tönnies (2012) resonate. This author showed us how consensus occurred within communities, some of which we might classify as social groups. Such consensus implied a common understanding of reality and took shape in a common language. For this reason, it is essential that in a sociohistorical analysis such as this one, we consider these social communities, which today could be identified with associations of those affected. From there, various strategies for institutionalizing these consensuses would gradually emerge. These generic ideas from Tönnies help us interpret the importance of community in institutionalization, but they do not allow us to fully understand all the elements involved in this phenomenon of RD institutionalization. In line with this, we can also mention the relationship between institutional analysis and social change. In fact, social change is concretized in the phenomenon of institutionalization (Tönnies, 2021).

For his part, Ronald Inglehart (1977) studies how changes in values affect policy formulation and how generational factors, in relation to the context of socialization, plays a decisive role in the values that underlie the institutional level. Ronald Inglehart’s work provides a critical perspective on how changes in social values impact public policy making. Inglehart’s (1977) theory of value change is key to understanding how societies evolve in their priorities and values, which has a direct implication on how health issues, including RDs, are addressed. Ronald Inglehart, in his work on value change in modern societies, identifies a transition from materialist values (focused on economic survival and security) to postmaterialist values (focused on quality of life, well-being, human rights, and social justice). This transformation has a significant impact on public policies, including how health issues are prioritized. These values emphasize quality of life, self-determination, and civic participation over traditional materialistic concerns, such as economic security. This shift in values, as described by Inglehart in Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society (1990), is central to understanding policy evolution.

Institutionalization concept offers a framework for understanding how the social and structural reality are internalized by individuals and social groups. In fact, according Ostrom (2007) “institution” refers to shared concepts by individuals or, in our perspective, by a society. Obviously, a legal norm is a materialized form of that shared view. Then, we consider that data contains in legal norm are very relevant to comprehend social phenomena of institutionalization but in not the unique. In any case this social and structural reality imply inequality (Crane and Pascoe, 2021), a phenomenon similar to what Fassin (2003) refers to in a different context as the “embodiment of inequality.” The institutionalization of rare disease policies clearly reflects this shift in values. Over the past few decades, there has been an increased attention to the quality of life and rights of patients with RDs. This phenomenon aligns with the theories of Inglehart, who argues that societies embracing postmaterialist values are more inclined to address issues of social justice. In Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies, Inglehart (1977a) explains how public policy priorities change as societies adopt these new values. The implementation of inclusive policies for patients with RD serves as an example of this transformation. Thus, Inglehart points out that the context in which young people socialize certain values will subsequently influence the institutional politics of a country, considering that positions of power are predominantly held by people of adult age.

In this context, people who socialized in Spain during significant events of their youth, such as the rapeseed oil crisis or the democratic transition, have introduced the debate on RDs and disability into the political arena of the twentieth century. This has led to the internationalization of a social awareness around these issues, they have led to the formulation of increasingly inclusive policies and advocated for diversity. This theory helps us understand the rise and implementation of the discussed policies and the proliferation of political discourses addressing RDs. On the other hand, and linked to this, it is important to include an approach that allows us to analyze the social values involved in policies related to RDs. This perspective will be provided by the so-called ACF.

In this research, we will analyze the process of institutionalization related to RDs. To this end, we will conduct a socio-historical study of the policies implemented in Spain. We will carry out a systematic analysis of the socio-historical and socio-political phenomenon of the process of institutionalization of Spanish and European policies on RDs. Our approach will be both general and specific, so we will study the broad process of institutionalization by linking it with specific case of study.

The Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) and their socio-historical usefulness

ACF is a tool for scientists to better understand coalition formation and behavior, agent learning processes, and policy transformations (Henry et al., 2014). This interpretive perspective was developed by Paul A. Sabatier in the 1990s (1988, 1993, 1998). From this perspective, the process of policy generation, development, and modification results from competition among agents who form coalitions to promote these policy transformations. In our opinion, this perspective is closely related to Erving Goffman's (1974) frame analysis, who proposes to analyze reality as if he were using camera. In this sense, Sabatier (1998) seems to have a similar idea, but he delves into political conflict and its resolution through the establishment of coalitions to favor the interests of the agents.

Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1993) focus their interest on a subsystem, the political subsystem, which is one of the most relevant in democratic societies. In this subsystem, we find different actors and agents who seek to intervene, in one way or another, in the decision-making processes. These processes move between the macro and the micro, since they may start from specific problems in particular contexts and end up modifying general policies. The example we will analyze here of policies related to RD can be a clear example of this. This is because legislation on RDs is based on specific problems: access to drugs, toxicity problems, etc.

In the socio-historical case of RDs, we are in the process of beginning this institutionalization process. Indeed, political transformations are currently taking place in Europe and, more specifically, in Spain. For this reason, it is likely that our research results will need to be revised in the future. Now, as the ACF proposes, the hermeneutic framework promoted by this approach aims to make explicit the belief systems operating in the case under study. The hierarchy of beliefs, according to Sabatier (1998), consists of three levels: deep core beliefs that include normative and ontological axioms; core beliefs of the policies that include beliefs that support the achievement of the deep core beliefs; and, finally, secondary, and instrumental aspects. In our analysis of relevant legislation, we apply this hierarchical framework to identify and categorize the underlying beliefs that drive policy decisions. This process involves examining existing laws and regulations for explicit and implicit beliefs, tracing these beliefs in the discourse used to develop policy. Specifically, we analyze how the belief systems of different policy actors are reflected in legal texts, considering how these beliefs guide their actions within the policy subsystem. As suggested by the ACF, understanding these belief systems is essential, as policy-relevant beliefs are the main motivators of actors’ behaviors and decisions within the subsystem (1988). By mapping the beliefs present in the legal framework, we aim to uncover the ways in which these beliefs have shaped the institutionalization of rare disease-related policies.

We should clarify that the ACF considers, in one way or another, that norms stabilize society and, therefore, establish a conservative resistance to policy change. This idea is not novel, as authors such as Durkheim (1982), Luhmann (2008) or Radcliffe-Brown (2002) defended this in one way or another. For this reason, Sabatier and Jenkins (1993) assert that the most frequent policy changes are often minor adjustments to previously established policies or to the belief systems related to them. In contrast, major transformations are less frequent and, therefore, their scientific analysis and understanding are important.

Our previous hypotheses are the following:

H1: Promoting coalitions are modified according to the unmet needs and the social impact of the problem.

H2: Legislation on rare diseases does not usually take society into account since it is based on an individualistic paradigm.

To address these initial questions, we set ourselves the following objective:

O: To analyze the evolution of legal regulations on rare diseases in the Spanish case and their relation to European legislation.

Methods

This research is framed within a socio-historical analysis of RDs legislation. We will focus on legislative norms as a tool for understanding institutionalized social values and beliefs. Likewise, we will conduct a contrastive analysis of the instituting values and beliefs. To this end, we will combine the documentary analysis of legal norms with previous theoretical and empirical research on the object of study. For this purpose, we have compiled different legal norms related to the field of RDs. These norms were analyzed to determine their relevance or not in the process under study. The generic inclusion criteria focused on the epistemological relevance of the legal norm in relation to the process under analysis, always from a diachronic and comprehensive perspective. We selected norms that explained the socio-historical evolution, whose preambles allowed us to understand the values, intentions and, if possible, the intervening agents (promoting coalitions). The inclusion criteria that were applied were as follows: comprehensibility of the socio-historical phenomenon, epistemological relevance, determination of values and intentions, and the possibility of identifying the intervening agents. It should be noted that legal norms of a descriptive nature are very focused on developing a specific aspect that legislators consider important. However, it should be noted that such rules may not always provide the desired level of relevant information. In this research, it was decided not to study these rules. The exclusion criteria were therefore determined as follows: lack of epistemological relevance, descriptive nature and excessive normative detail. For this reason, we excluded from this research both regulations and those parts that did not allow us to establish a comprehensive diachronic process. An example is the Resolution of July 17, 1982, of the General Coordinator of the National Plan for the Toxic Syndrome, which determines the amount of the complementary family economic aid.

Our analysis was conducted from the perspective of the advocacy coalitions proposed by Sabatier (1987, 1988, 1991, 1998, 2007), and Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1993). To this end, we reviewed the values and beliefs that could be inferred from the study of legislation. These legislative norms will help us to see the strategies and influences among the agents. In turn, the analysis of values and beliefs will also help us to establish whether actors establish coalitions as a collective political entity (Nohrstedt and Heinmiller, 2024). We will focus on three dimensions: the identification of values and beliefs established in norms, the potential influences of the agents detected through legal norms and, finally, the awareness (perceptual elements) of the social agents involved.

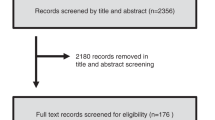

The process is shown schematically in the following flow chart (Fig. 1).

Results

The associationism and the emergence of policies related to RDs, both in the international context and in Spain, are related to and influenced by a multiplicity of social factors and cultural changes that have been taking place since the 1980s. In fact, the social and health problems caused by the Toxic Oil Syndrome (TOS) also led to the creation of associations of those affected, whose main objective was to create public opinion and pressure political groups to achieve their goals. In this sense, the process of social reflexivity and personal self-determination, together with the proliferation of diverse political discourses, as well as the elaboration of legislative norms show the transformation of values and beliefs. In the case of Spain, the transition from Franco’s dictatorship to democracy brought with it a significant social transformation.

An interesting approach that has helped to understand this type of phenomenon of convergence of interests and coalitions is the ACF (Nohrstedt and Heinmiller, 2024). Coalitions between associations of people affected by RD, either among themselves or with political agents, have gradually reshaped elements of the health system, as well as the social perception of social reality. These changes can be exemplified by the health policies implemented in recent years. These policies clearly show the transformation of values and beliefs about.

In the late seventies and early eighties of the twentieth century, there was a significant transformation in the health systems of the so-called “West”. The first paradigmatic example can be found in the United States of America, where Abbey S. Meyers (2016) shows how she fought for people with RD to have more possibilities of access to medications. This social struggle led President Reagan to sign the first law promoting orphan drugs on January 4, 1983. This law, known as the “Orphan Drug Act”, already makes clear reference to orphan drugs. This law makes clear reference to so-called RDs and conditions and the orphan drugs needed for those affected. Subsequently, Meyers with other affected people set up the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) in the region as the first organization for people affected by RDs.

The affected associations, in this case NORD, used media support to put pressure on the political authorities and achieve their objectives (Cheung et al., 2004). This strategy was also used as a model in other countries. The second country to implement legislative measures in this regard was Japan in 1993 (Song et al., 2013). Australia was another region that developed, a regulation in the 20th century: Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Act of 1990 (Gammie et al., 2015).

Spain is a particular case because, as we shall see, it generated regulations related to a rare disease, but this did not materialize in any global legislative action. We are referring to the well-known case of TOS with the first cases occurring in early 1981. Now is not the time to go into detail about this event, which was so relevant to the transformation of the health system in Spain, although we mention it to show the temporal coincidence of both sociohistorical events. On the other hand, the 1980s also saw the HIV pandemic, the discovery and cases of hepatitis C infections, as well as a substantial increase in the use of injectable drugs. These biosocial examples are also related to the social concern about health and changes in the political system in the region under study. At that time, there was a transition from dictatorship to democracy in which the perception of freedom was exacerbated, and various structural maladjustments became evident, bringing with them social protests, associationism and volunteerism. As Avellaneda et al. (2007) put it: An unprecedented interest in volunteering and associationism appeared in society in general, which together with the “media boom” made it possible for civil society to become aware of its importance and considerably increased the appearance of the associative movement in the media (Avellaneda et al., 2007: 181).

Before analyzing the SAT case, it is worth noting that we consider that there have been three non-linear phases in the process. In each of them, importance was given to a significant element: health (bio-health perspective); control (political perspective) and money/work (economic and social perspective). As we have just mentioned, these phases do not occur one after the other in a linear fashion. The first one had a more biomedical focus, due to the urgent need to address the problem. Subsequent phases, to be executed concurrently, were designed to prioritize both social and economic considerations, specifically Phase II and Phase III. However, the commencement of both phases was contingent upon the attainment of a certain level of bio-health control over the health crisis.

First episode: The toxic oil syndrome

Phase I—Bio-sanitary perspective

In 1981 a new syndrome of an acquired nature appeared in Spain. The socio-health problem caused by the TOS showed the stubborn corruption and shortcomings in health surveillance processes. The health problem was related to the adulteration of rapeseed oil that was sold in impoverished areas and outside the existing regulations at the time. After the consumption of this oil, various types of pathologies and deaths began to occur, which alerted the population, political agents and the media.

As a result of media and social concern, the Spanish government at the time took the measure of creating a national program for the care and follow-up of people affected by toxic syndrome (Royal Decree, 1839/1981). This political measure could be considered regulatory, as it modeled the behavior of health institutions by introducing specific measures for the care of affected persons and responding to the need to deal with the epidemic. This policy (developed by the Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Security) aims to “build a coordinating and monitoring body for all issues related to assistance for those affected”. In addition, it establishes a mechanism for relations between health professionals and hospitals that will operate both in and out of hospital. Hence, it institutionalizes an extension of the health system towards society (out-patient care).

The legal norm is structured at three levels (Hernández Martín and Martínez-Pérez, 2011)—national, intermediate and local. In this program, four main agents are fundamentally related−ministry, hospitals, physicians and patients. Its main values were related to control, surveillance, care and attention both inside and outside hospitals. In addition, it had a marked contingent and provisional character which, together with the urgency of the situation, formed a value framework based on immediacy and rapid response to a complex problem. This temporary nature had a specific “date of completion” related to overcoming of the epidemic. On the other hand, although it could be affirmed that a first step has been taken in the formation of social care for those affected, this cannot be within the spirit of the regulation. So much so that, in its first paragraph, it is literally stated:

“To the appearance of the toxic outbreak currently existing in our country, the Health Administration has responded with a set of measures of all kinds: epidemiological, etiological research, clinical action, assistance and inspections, through the ordinary administrative organization of the State” (Royal Decree, 1839/1981: 19695).

Therefore, it would be more appropriate to indicate that the motivation for this program is fundamentally biosanitary and, secondarily, political in nature. This fact makes sense due to the health urgency and the need for political control inherent to these types of measures. A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown below (Fig. 2).

Source: own elaboration according to Royal Decrete 1839/1981 (Royal Decree, 1839/1981).

Phase II—Political perspective

In the first phase, we found that the regulation was focused on the biosanitary perspective. Subsequently, it was necessary to restructure the measures adopted. In this sense, R.D. 783/1982 (Royal Decree, 789/1982), determines “an administrative body under the Ministry of Health and Consumption, which is entrusted with ensuring the unity of direction of services, coordination and strengthening in all its aspects the action of the Administration in favor of the affected population group”. In this sense, the measure in question gives greater importance to the political element and its link with the citizens. Likewise, a few months later, Royal Decree (R.D.) 1405/1982, was approved, creating the National Plan for the Toxic Syndrome. The latter establishes the creation of a General Coordinator, with the rank of General Director. The person in this position should control and coordinate the activities of the State in relation to the SAT and “particularly in its health and social aspects, to enhance in all its dimensions the action of the Administration in favor of those affected”.

The National Plan raised the political importance of regulation, as the Plan was part of the Presidency of the Government. In R.D. 1839/1981, the political entity was the Ministry, but now it is the Presidency of the Government. The general coordinator of the plan controlled several general sub-directorates and a specific technical office. In turn, the Plan was structured in Provincial Programs that followed the instructions of the general coordinator. Undoubtedly, the importance of political control and coordination is high. Finally, this plan (Article 8) introduced research entities as intervening agents by allowing the general coordinator the possibility of approving the implementation of research projects and research contracts.

This new R.D. increased political control over the problem and had as its main values those related to governmental action. One of the changes, not strictly related to politics, involved the incorporation of research as a potential element to help those affected, as well as the improvement in the functionality of the political process. However, as was the case with the previous Royal Decree, social agents and the social perspective itself did not have a prominent place. We can affirm that it is plausible to think that the government considered that political action sufficient to meet the social needs of those affected. However, Article 1 of this R.D. mentions actions involving social and educational services, which means a closer approach to society than R.D. 1839/1981. Likewise, in the same month of June, R.D. 1276/1982, was approved, creating economic aid for those affected, which undoubtedly increases support through non-sanitary channels for those affected.

The reason for this shift could lie in the gradual importance of social issues in the political debate. In fact, Hernández Martín and Martínez-Pérez (2011) showed that the session journal from September 15, 1981, included debate on those affected. Especially about their labor, educational, social problems and about the problems generated by the disability produced by the condition. Among the measures discussed were the creation of a census (an aspect that will be maintained for R.D.), the importance of mental health and the attempt to institutionalize concrete and specific measures. All these aspects open the door to a reconfiguration of the conception of the “sanitary system” into a “health system” (Royal Decree 783/1982). A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown in next image (Fig. 3).

Phase III—Economic and social perspective

This third phase would be related to the entry into force of R.D. 1276/1982, which complements the aid to those affected by the toxic syndrome. This R.D. establishes various economic and social measures. On the one hand, there is a “complementary family economic aid” with the aim of guaranteeing a minimum income. On the other hand, it is established that children under 14 years of age can also receive another economic aid for “nutritional dietary purposes”. Thirdly, collaboration measures are established among agents to achieve the social and labor reinsertion of those affected. Additionally, measures are also taken in relation to the schooling process of those affected, as well as aid for school canteens, school supplies, etc.

In this new R.D., the National Institute of Social Services (INSERSO) acquires greater relevance as an agent of social protection. In fact, the fourth article of this regulation indicates that those affected will be included in collaboration programs (existing or promoted by the National Plan) with this entity. This fact is of crucial socio-historical importance as it establishes a more defining process of institutionalization. In fact, as we will see later, this institution will end up containing an organization of great relevance for RDs (we are referring to the State Reference Center for the Care of People with Rare Diseases and their Families).

Another important aspect promoted by this R.D., which had not appeared until then, is the involvement of the Ministry of Education and Science and, therefore, the educational system. In this regulation, explicit reference is made to a Schooling Plan that would implemented through the Order of development issued by the Ministry of Education and Science (1982). This Plan is aware that the schooled and affected persons could be in four situations: regularly attending class, having irregular attendance, they could be unable to attend class or be hospitalized. For each of them, measures were taken to provide care, compatibility and contact between teachers and students in case of hospitalization. At the same time, other mechanisms for travel assistance, educational assistance, development of individualized programs, etc., were established.

R.D. 1276/1982, shows clear values of economic, social, and educational reinsertion and integration. The National Plan for the Toxic Syndrome, on the other hand, shows marked values of political control and organization. Thus, two paths are established that feedback on each other and that will mark, in a decisive way, the definitive management of health in the field of RDs. In this sense, the most social pathway is prior to the National Plan, although after its entry into force, all actions end up being subsumed by this Plan. In fact, the Order of February 15, 1984, which establishes certain measures for the social reinsertion of people affected by toxic syndrome, materializes some beliefs and values present in the R.D. 1276/1982 such as labor promotion and economic autonomy.

In this sense, the Order of February 15 aims to promote cooperatives, labor companies, as well as self-employment. For this purpose, it establishes economic aids. This aspect has a marked labor and educational promotion character. However, we still do not find clear measures that we can determine as strictly social and community measures.

The aforementioned regulations had a high normative importance until the entry into force of R.D. 415/1985, according to which the Ministry of the Presidency was restructured and the competences related to the National Plan for the Toxic Syndrome passed, on the one hand, to the Ministry of Health and Consumption, and, on the other hand, continued in the Ministry of the Presidency. In this case, only the economic and social aspects remain in the Ministry of the Presidency, which implies a greater importance of these aspects as opposed to the biomedical ones. Nevertheless, and in spite of this, this legislative norm means de facto the end of the National Plan for the Toxic Syndrome.

The importance of the social aspect was again emphasized in the Report of the special report on the toxic oil syndrome (Congreso de los diputados, 1995). In it, the social aspects generated by the previous measures (as we indicated before, they also presented this character) are discussed. In the conclusions, it is proposed—(1) to increase coordination, (2) to speed up, the procedures (files and applications) through coordination, (3) to promote and improve collaboration between institutions, and (4) to increase the participation of those affected. This last aspect is noteworthy as it is a political document that clearly establishes the importance of empowering those affected. However, this dialog or participation was not clearly detected in the Spanish regulations of the 20th century, until the impulse promoted by the European institutions. A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown in image below (Fig. 4).

Second episode: The institutionalization of rare diseases

The democratization that took place in Europe in the 20th century, and more specifically in Spain, led to major changes in the healthcare system. The SAT tragedy also promoted the acceleration of these modifications. In this sense, the SAT is an outstanding example of how citizen and media pressure promoted political measures. In 1986, the National Health System, was created from the General Health Law, introducing structural changes that affected the approach to RDs, especially in terms of decentralization, research, specialization, primary care, coordination between administrations and the development of early care and diagnosis programs.

The transformation of the Spanish health system was regulated by Law 14/1986, known as the General Health Law. This law was born due to the stagnation of “public organization in the service of healthcare”, as it states. Currently, equity and democratization operate as values which have materialized in the social coverage and health care explicitly present in the preamble of the aforementioned Law. In turn, the value of the patient’s social reintegration is also found as the main motivating element (Art. 6), similar to that established for the SAT phenomenon. This same idea is also found in Article 20 in relation to mental health (another element that is again reminiscent of the rules on EWS). In this sense, the conception of mental health that the norm seems to suggest is broader than the strictly biomedical one, assuming a relationship with the existing social context. This aspect is novel in the political sphere.

It was necessary to wait 10 years before we could truly speak of a clear process of institutionalization of the social phenomenon of RD. This happened after the enactment of Royal Decree 1893/1996, when the CISAT (Centro de Investigación del Síndrome del Aceite Tóxico) was created within the Carlos III Institute and coordinated by the Subdirección General de Epidemiología e Información Sanitaria (General Subdirectorate of Epidemiology and Health Information). This gave it a certain descriptive and monitoring character of the SAT. This gives the idea that politically it is conceived as an issue that has been overcome and simply needs epidemiological follow-up. After all, what was learned from the EWS was incorporated into the General Health Law of 1986 (Ley 14/1986). This idea of monitoring and evaluation materialized, once again, in the creation of the Interministerial Commission for monitoring measures in favor of people affected by Toxic Syndrome.

This process of institutionalization seems to imply a concentration of resources and control in a single institution, which will be responsible for advancing research and trying to anticipate any problems that may arise. Hence, epidemiological follow-up and health surveillance acquire a hitherto unprecedented importance. In addition, the individualistic paradigm is of great importance, since there is a special focus on the patient, something that was not so marked before (see “Phase III—Economic and social perspective”). A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown in next image (Fig. 5).

Third episode: The European Union as a new intervening actor

The entry of Spain into the European Economic Community (EEC) brought with it the gradual intervention of this institution as an important external agent. This annexation operates as an essential factor to understand the promotion of policies on RDs and national plans within the framework of the EU in the 90’s and in the following years. This fact is very evident in the influence that the decisions of the institutions. The pursuit of coherence and coordination in policies led Spain and other member states to adopt European legislation adopting the national plans to specific regional needs. The year 1999 becomes, at the European level, a special year because of the numerous rules and regulations that were enacted. However, European institutions were aware of the need to address these lesser-known diseases.

The Council of the European Union established the Council Decision of 15 December 1994 adopting a specific program for research and technological development, including demonstration, in the field of biomedicine and health (1994–1998). Article 4.6 of the program indicated the challenges in carrying out fundamental and clinical research on a national scale in the field of RD. In addition, it also indicated that it is possible to develop joint research and experimentation among the member states. It also explicitly promoted the development of an inventory of RDs and the constitution of a bank of “orphan” drugs for clinical research. Once again, the belief in monitoring as a preventive factor was embodied in this regulation. This Decision showed the beginnings of the relevance that RD was going to acquire. So much so that, within 5 years, RD went from being part of an item to having a specific program.

In this regard, Decision No. 1295/1999/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 1999 adopting a program of Community action on RDs within the framework for action in the field of public health (1999–2003). This standard refers to prevalence as a defining element of RDs and to the lack of information on them. Likewise, “RDs are considered to have little impact on society”, which, together with the problems inherent to this type of condition, implies that it is necessary to make progress in understanding them. Another relevant aspect of this decision is the explicit relationship between health, quality of life and community action. Hence, the promotion of a European information network is urged, as well as the promotion of inter-institutional cooperation. With these and other aspects as motivating elements, beliefs and values, the European Parliament creates a specific and innovative Community action program. This program aims to foster cooperation, with a strong community and transnational character, promoting research, as well as relations between health professionals and those affected. We can clearly see that this community action is related to the impact that the EURORDIS association has had since its foundation in 1997. This organization will be crucial in the development of future EU regulations.

Subsequently, on December 16, 1999, the Council of the European Union established a series of incentives for the pharmaceutical industry to develop and market drugs to treat serious and RDs. This Council decision became Regulation (EC) 141/2000, which aims to improve access to treatment, promote research into these drugs and establish European coordination regarding their regulation. According to this regulation, an orphan drug is considered to be as a drug intended to prevent or treat rare or serious diseases which are more common, but making them difficult to market due to the lack of sales prospects. Particularly striking is point two of the previous considerations, where explicit mention is made of patients and of the values of equity in access to treatment. This regulation follows in the footsteps of the standards established in the United States of America in 1983 and, subsequently, in Japan in 1993. Thanks to this regulation, the EU supports the Orphanet initiative, created by the INSERM (French National Institute of Health and Medical Research) in 1997.

On this occasion, we detected a substantial difference between the European and Spanish perspectives. The former emphasizes the importance of the community, whereas the Spanish case, there has been a shift from a social perspective to a more institutional and individual one. A scheme illustrating all the elements of analysis we are using is shown below (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Policies on RDs began to proliferate from the 1990s, linked to a process of reconfiguration and adaptation of health systems, creating social policies to address new challenges emphasizing social inclusion and citizen participation.

Furthermore, the focus on citizen participation and empowerment of patients’ associations can be understood within the theoretical framework of established by Ronald Inglehart. The growing influence of these associations on RDs policymaking shows how the values of self-determination and participation have been integrated into institutional structures. Inglehart (1990) discusses how these emerging values encourage greater citizen participation in politics. Patient associations become key players, promoting legislative changes and the creation of policies that are more inclusive and sensitive to the needs of minorities affected by RDs.

Similarly, Spain’s democratization and economic openness have facilitated the adoption of post-materialist values, leading to a more inclusive and participatory approach to health policy. Thus, in Cultural Evolution: People’s Motivations are Changing, and Reshaping the World, Inglehart (2018) explores how changes in people’s motivations and values influence cultural and political evolution. Spanish and European policies on RDs are a manifestation of these cultural shifts.

The evolution of rare disease policy has also been significantly influenced by the concept of “democratic innovation” as discussed by Archon Fung and Wright (2001). They argue that the incorporation of new forms of citizen participation can transform governance. In the context of RDs, this perspective suggests that the most effective policies are those that actively integrate patient associations and other non-traditional stakeholders into the policy formulation and implementation process, thus facilitating a more holistic approach to addressing the needs of RDs patient communities.

The integration of diverse stakeholders in health policy, especially in the field of RDs, can also be understood through the work of Sheila Jasanoff (2004), who introduces the idea of co-production, where scientific knowledge and social values develop together, mutually affecting their forms and contents. In this sense, rare disease policies benefit not only from biomedical advances, but also from the interaction among scientists, legislators, patients and society in general. This interaction results in a framework that is more adaptable to the specific needs of those affected by RDs.

In addition, the influence of social movements in shaping health policies should be highlighted. Tarrow (2011) explains how social movements can generate significant changes in public policies through mobilization and social pressure. Applied to the field of RDs, this approach highlights the importance of activism and mobilization of patients and their families, who, through protests, campaigns and collaboration with the media and other organizations, have managed to put RDs on the political agenda, promoting legislation and strategies that can respond to their needs.

As we have indicated in the introduction, all of this is related to the various biomedical events in recent years, including HIV, hemophilia or SAT, among others. All these aspects have intervened in different ways to achieve the recognition of access to biomedical health as a fundamental right (Lopes-Júnior et al., 2022). However, we also detected in our research a constant political control over institutions and the absence of references to the associative sphere. Akrich et al. (2008) have indicated that associative networks, alliances and collectives of affected people have the capacity and intention to define and implement health policies. This reality is more noticeable at the present era compared to the end of the last century. Baggott and Forster (2008) have shown that in the United Kingdom, the participation of users of health services were promoted when a certain democratic deficiency in the functioning of the national health system was detected. Our analysis shows that, precisely in the transition from the 20th to the 21st century, a certain modification in this sense was generated in Spain in the case of RDs.

During these years, the foundations for training, social awareness and information on RD were laid. Our results show that the associative movement began to stand out in the shaping of legislative regulations and, gradually, the foundations were laid to develop the Rare Diseases Strategy of the National Health System, approved in 2009. The importance of the associative movement was materialized in the European documents, which expressly indicate the need to attend to the affected community. In Spain, on the other hand, this fact is not reflected in the regulations that have been drafted. Hence, for the Spanish context, we could affirm that, according to classification established by Lowi (1971), we are facing with a phenomenon of fundamentally constitutive policymaking. This is so since the creation of new governmental institutions dedicated to the health research, such as CISAT. This institutionalization process was centered on political and biosanitary control. Furthermore, it can be deduced from the legislation analyzed that there was a marked belief in the provisional nature of political action. After all, the SAT disease was caused by a toxic agent and, rather than a transmitting biological agent capable of causing an epidemic. It is therefore reasonable to think that the policy-makers considered that the institutions and processes generated would not last over time. The creation of CISAT, precisely, shows the importance of epidemiological monitoring but suggests a reluctance to consider actions different from those carried out previously. This aspect may explain why in Spain no legal norms related to RDs were promoted and it was necessary to wait for the impulse of the EU for this to happen.

The various policies promoted during the 20th century are situated in a context of welfare state reforms associated with new challenges, such as the case of RDs. However, this implementation of the welfare state in this regard is still scarce. Currently, only a few countries consider a broader set of dimensions that are relevant from a health policy perspective, capturing aspects of vulnerability and socioeconomic impact (Adachi et al., 2023). After all, developing policies, action plans and national strategies on RDs involves a multitude of stakeholders and must consider different facets to ensure prevention, treatment, research, access to treatment, information management, education, economic aspects and social support (Li et al., 2023). Throughout our research we have seen that Spain has already started to take steps in this direction concerning the issue of EWS, although this was done in different steps and at different times.

Throughout this incipient process of institutionalization of the social phenomenon of RDs, we see that different stakeholder have been incorporated according to existing interests and beliefs. According to Patel et al. (2011), in the current U.S. healthcare system it is possible to find a series of intervening key actors− Industry, payers, researchers, professional organizations, government, and patient groups. These stakeholders have gradually established, their role in the generation of standards for RDs. However, during the 20th century the identified stakeholders were more limited. Evidently, in the USA and Japan, the pharmaceutical industry was already intervening in this process, whereas in Spain, took longer to come into play. Once again, the European Union promoted the incorporation of this stakeholder into the organization of the process of institutionalization of RD, something that Spain had not previously contemplated in any case.

The organizations representing those affected, along with patients themselves, were able to secure their dedicated space as a result of the media pressure, similar to what happened in other regions. The example of SAT, in Spain, shows this clearly. In fact, in the famous debate on the TV program “La Clave” (No. 260 entitled “The Mysterious Syndrome”), a representative of those affected appears. For this reason, it is necessary to modify the list of Patel et al. (2011) and add the media as agents of great relevance for the current shaping of health systems. Evidently, their action is not direct, but their ability to shape public opinion and control can bring about (and did so in the 20th century) modifications and adjustments to legal norms.

Another interesting aspect of the institutionalization process is the initial belief that only political and biosanitary entities (hospitals and research entities) would be capable of managing and controlling the problem. With the passage of time, it became clear that this was not entirely the case. In fact, Martin (2022) states that currently, in the UK, there have been several major institutional changes and the emergence of the “impact agenda”. A consequence of this is a much greater emphasis on interdisciplinarity and a multifocal strategy (Hermida-Ameijeiras, 2024). In this regard, social scientists are being encouraged to work closely with stakeholders and users of their research.

The analysis of the institutionalization of rare disease policies in Spain and Europe shows a complex process influenced by both historical factors and the evolution of power dynamics within the healthcare sector. Globalization and European integration have been determining factors in the evolution of healthcare policies. In Europe, the creation of European Reference Networks, supported by the European Commission, has allowed member countries to coordinate efforts to improve diagnosis, treatment, and access to therapies for RDs. This transnational cooperation approach is key to understanding how RDs policies have been institutionalized within the European context, contributing to a more coherent and accessible framework for patients (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2023).

This process of integration has had its effects in Spain. In this case, by aligning with European regulations, Spain has modified its approach towards RDs. The Rare Disease Strategy of the National Health System (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2023), launched in 2009, reflects this push towards greater European collaboration and sets out guidelines to improve access to healthcare services and support research into these conditions. However, as pointed out throughout the text, the implementation of these policies in Spain has been slower compared to the European community framework, due to a more centralized and politically driven approach to managing these health issues (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2023).

This shift in healthcare sector policy—especially regarding RDs—is understood through certain frameworks, such as the “Advocacy Coalition Framework” (ACF) proposed by Sabatier (1988) and later updated (1998). This framework underscores how different groups of actors—including patients, healthcare professionals, and policymakers—form strategic coalitions to influence policy-making. However, we must note that Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith’s theory, although useful, does not fully incorporate the impact of contemporary power dynamics and the growing participation of civil society in health policy.

The democratic innovation framework of Archon Fung (2001) can provide a broader vision of how citizen participation and the inclusion of previously excluded groups, such as patient associations, have gained prominence in the formulation of healthcare policies. Fung (2001) argues that active citizen participation, through open and fair deliberations, is crucial for achieving more inclusive and legitimate political decisions. The democratization of healthcare policy, evident in the growing influence of patient associations, has been key in giving voice to those affected by RDs and ensuring that their needs are considered in public policies. The proposed approach highlights a shift towards inclusive governance and the need to incorporate the voices of those historically excluded from the decision-making process (Inglehart, 2018).

As participatory openness within healthcare systems has advanced, social mobilization around RDs, particularly in the Spanish context, has been essential for increasing the visibility and recognition of these conditions on the political agenda. Since the case of TOS in the 1980s, patient associations have functioned as pressure groups, urging governments to implement legislative measures and allocate resources for the treatment of RDs. As noted in the literature, such mobilization has been pivotal in transforming the approach to these diseases, initially seen as a marginal issue, into a public health problem of national and international priority (Zanello et al., 2024). Over the past 40 years, RDs have gained special prominence in public health (Chung et al., 2022), with attention given to their associated socio-economic costs (Chung et al., 2023, Nguengang Wakap et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022), as well as the quality of life of patients and their caregivers (Do Valle et al., 2024). In terms of scientific development, this has led to increased attention on the so-called ultra-RDs over the past two decades (Baldovino et al., 2025).

As demonstrated by recent reports, such as the ReeR 2023 (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2023), the situation of RDs in Spain remains a significant challenge, although significant progress has been made in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and public policies (Ministerio de Sanidad, 2024). A comparison with treatment in other countries (e.g., the USA, Japan, and Australia) highlights how the influence of patient associations has been a key element in the implementation of laws like the Orphan Drug Act in the USA, or the Initiative on Rare and Undiagnosed Diseases (IRUD) in Japan (Takahashi and Mizusawa, 2021), which promote access to medicines, diagnosis, and research for RDs. Unlike Spain, where RD policies have focused primarily on healthcare management, these countries have placed considerable emphasis on creating legislative frameworks and fostering cross-sector collaboration to ensure treatments are accessible and patients have an active role in policy formulation (Avellaneda, 2007).

Thus, internationally, collaboration networks have increased (Lumsden and Urv, 2023), enabling better coordination in the diagnosis and treatment of RDs. These networks facilitate the exchange of knowledge, experiences, and resources, which is particularly valuable for diseases affecting a small proportion of the population (Degraeuwe et al., 2024). In Europe, initiatives like the European Reference Networks (ERNs) have contributed to improving healthcare by allowing patients to access specialized centers for various rare conditions, regardless of their geographical location.

Conclusions

The institutionalization of rare disease policies in Spain, within a broader European context, has been a complex process. Through this sociohistorical study, it has become clear how political, social and economic changes have influenced the formulation of RDs policies. Spain’s transition to a democratic system saw a major transformation in the health care system, driven by the growing influence of patient associations.

The Toxic Oil Syndrome (SAT) in the 1980s exemplifies this process of change. This syndrome not only highlighted deficiencies in health surveillance and corruption, but also catalyzed the creation of new health structures and regulations. The initial government response was primarily biosanitary and political, but over time, policies evolved to include economic and social perspectives, marking an important step toward the institutionalization of rare disease care.

One of the key findings of this study is the growing importance of patient associations in policy formulation. Akrich et al. (2008) and Baggott and Forster (2008) have highlighted how associative networks and patient alliances can define and implement health policies. In Spain, although regulations in the 20th century did not clearly reflect this empowerment, the pressure from associations of people affected by SAT and other RDs was fundamental in driving legislative and policy changes.

Spain’s entry into the EEC and subsequent integration into the European Union (EU) played a crucial role in promoting RDs policies. EU decisions and regulations, such as the Community Action Program on Rare Diseases (1999–2003) and Regulation No. 141/2000 on orphan drugs, boosted transnational cooperation and research in this field.

These European initiatives promoted information networking and collaboration among member states, facilitating the adoption of more coherent and effective regulations at the national level. The implementation of the Orphanet initiative, supported by the EU, is an example of how European collaboration can improve access to treatment and research on RDs.

The evolution of Spanish RDs policies reflects a process of learning and adaptation. The SAT acted as an initial catalyst, but it was European influence and changes in social values that led to a more formal and structured institutionalization of RD policies. The General Health Law of 1986 and Royal Decree 1893/1996, which created the CISAT, are important milestones in this process.

However, this study also reveals that Spanish policies have tended to focus on political and biosanitary control, paying less initial attention to the participation of those affected and to social and community aspects. It took a push from the EU for more inclusive approaches to be adopted and the importance of empowering patients and their associations to be recognized.

Likewise, the analysis of advocacy coalitions, based on Sabatier’s Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) (1988, 1998), has proven to be a valuable tool for understanding the dynamics of RD policies. Coalitions between patient associations, health professionals, and political actors have been instrumental in promoting legislative and policy changes.

In this regard, Henry et al. (2014) have shown how ACF can help understand the formation and behavior of these coalitions, as well as the learning processes and policy transformations involved. In the case of RDs, these coalitions have facilitated the introduction of more inclusive policies and the creation of institutions dedicated to research and care for these diseases.

Despite the progress made, this work has highlighted several areas that are still pending. Funding of RDs research and equitable access to treatments remain significant problems. Adachi et al. (2023) and Li et al. (2023) point to the need for more robust policies. International cooperation and the integration of different stakeholders, such as the media, pharmaceutical industry, and patient organizations, will be crucial overcoming these challenges. Patel et al. (2011) and Martin (2022) emphasize the importance of a multifocal strategy to improve RD management and promote policies that gain effectiveness.

The institutionalization of RDs policies in Spain and Europe reflects a process of social and political change influenced by citizen pressure, the evolution of social values (post-materialist), and international cooperation. The transition from a biosanitary and political perspective to a more participatory approach has been fundamental in improving the care and rights of patients with RDs.

The role of patient associations, the influence of the EU, and the ACF have been key elements in this process. As societies continue to evolve, there is a need to further promote participatory policies that address the policy and health gaps associated with RDs, ensuring equitable access to treatment and improving patients’ quality of life.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Adachi T, El-Hattab AW, Jain R, Nogales Crespo KA, Quirland Lazo CI, Scarpa M, Summar M, Wattanasirichaigoon D (2023) Enhancing equitable access to rare disease diagnosis and treatment around the world: a review of evidence, policies, and challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(6):4732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20064732

Akrich M, Nunes J, Paterson F, Rabeharisoa V (2008) The dynamics of patient organizations in Europe. Presses des Mines, Paris

Avellaneda A, Izquierdo M, Torrent-Farnell J, Ramón JR (2007) Enfermedades raras: enfermedades crónicas que requieren un nuevo enfoque sociosanitario. del Sist Sanit de Navar 30(2):177–190. http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1137-66272007000300002&lng=es&tlng=es Avaliabre online [28 may 2024]

Baggott R, Forster R (2008) Health consumer and patients’ organizations in Europe: towards a comparative analysis. Health Expect 11(1):85–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00472.x

Baldovino S, Sciascia S, Carta C, Salvatore M, Cellai LL, Ferrari G, Taruscio D (2025) A global survey about undiagnosed rare diseases: perspectives, challenges, and solutions. Front Public Health 13:1510818. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1510818

Cheung RY, Cohen JC, Illingworth P (2004) Orphan drug policies: implications for the United States, Canada, and developing countries. Health law J 12:183–200

Chung CCY, Hong Kong Genome Project, Chu ATW, Chung BHY (2022) Rare disease emerging as a global public health priority. Front Public Health 10:1028545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1028545

Chung CCY, Ng NYT, Ng YNC, Lui ACY, Fung JLF, Chan MCY, Wong WHS, Lee SL, Knapp M, Chung BHY (2023) Socio-economic costs of rare diseases and the risk of financial hardship: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 34:100711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100711

Congreso de los diputados. Informe de la ponencia especial en relacion con el síndrome del aceite toxico, BOE 1995, 18 december 1995, 184, Serie E. Available online: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L5/CONG/BOCG/E/E_184.PDF

Crane JT, Pascoe K (2021) Becoming institutionalized: incarceration as a chronic health condition. Med Anthropol Q 35(3):307–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12621

Degraeuwe E, Hovinga C, De Maré A, Fernandes RM, Heaton C, Nuytinck L, Persijn L, Raes A, Vande Walle J, Turner MA (2024) Partnership of I-ACT for children (US) and European pediatric clinical trial networks to facilitate pediatric clinical trials. Front Pediatr 12:1388170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2024.1388170

Do Valle DA, Bara TDS, Furlin V, Santos MLSF, Cordeiro ML (2024) Psychobehavioral factors and family functioning in mucopolysaccharidosis: preliminary studies. Front Public Health 12:1305878. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1305878

Durkheim E (1982) The rules of sociological method. Palgrave MacMillan, New York

European Commission. Rare diseases and European Reference Networks. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/rare-diseases-and-european-reference-networks/european-reference-networks

European Parliament and Council of the European Union (1999) Decision No 1295/1999/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 1999 adopting a programme of Community action on rare diseases within the framework for action in the field of public health (1999 to 2003). Official Journal of the European Communities. 22, 6. Ref.: L155/6. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dec/1999/1295/oj

European Parliament and Council of the European Union (2000) Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 1999 on orphan medicinal products. Official Journal of the European Communities. 22 January 2000, 0001-0005. Ref.: L018/1. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2000:018:0001:0005:en:PDF

Fassin D (2003) The embodiment of inequality. AIDS as a social condition and the historical experience in South Africa. EMBO Rep. 4:S4–S9

Fry J (1962) Presenting symptoms in childhood. Butterworths, London

Fung A (2001) Deliberative democracy and the real world: the dynamics of expertise. Public Policy 22(2):135–159

Fung A, Wright EO (2001) Deepening democracy: institutional innovations in empowered participatory governance. Verso, Brooklyn, New York

Gammie T, Lu CY, Babar ZU (2015) Access to Orphan drugs: a comprehensive review of legislations, regulations and policies in 35 countries. PLoS ONE 10(10):e0140002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0140002

Goffman E (1974) Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press, London, England

Henry AD, Ingold K, Nohrstedt D, Weible CM (2014) Policy change in comparative contexts: applying the advocacy coalition framework outside of Western Europe and North America. J Comp Policy Anal Res Pract 16(4):299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2014.941200

Hermida-Ameijeiras Á (2024) Special issue “diagnosis and treatment of rare diseases”. J Clin Med 13(9):2574. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13092574

Hernández Martín G, Martínez-Pérez J (2011) Cambio político, enfermedad y reforma sanitaria: la respuesta asistencial al Síndrome del Aceite Tóxico (España, 1981–1998). Asclepio 63(2):521–544. https://doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2011.v63.i2.504

Holtzman NA (1978) Rare diseases, common problems: recognition and management. Pediatrics 62(6):1056–1060

Inglehart R (2018) Cultural evolution: people’s motivations are changing and reshaping the World. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom

Inglehart R (1990) Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton University Press: Princeton, United States

Inglehart R (1977) Modernization and postmodernization: cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, United States

Inglehart R (1977) The silent revolution: changing values and political styles among western publics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, United States

Jasanoff S (2004) States of knowledge: the co-production of science and social order. Routledge, Oxford, United Kingdom

Knox EG (1971) Epidemics of rare diseases. Br Med Bull 27(1):43–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a070813

Ley 14/1986, de 25 de abril, General de Sanidad, BOE 1986, 102, 29 April 1986, Ref.: BOE-A-1986-10499. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/1986/04/25/14/con

Li X, Wu L, Yu L, He Y, Wang M, Mu Y (2023) Policy analysis in the field of rare diseases in China: a combined study of content analysis and Bibliometrics analysis. Front Med 10:1180550. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1180550

Lopes-Júnior LC, Ferraz VEF, Lima RAG, Schuab SIPC, Pessanha RM, Luz GS, Laignier MR, Nunes KZ, Lopes AB, Grassi J, Moreira JA, Jardim FA, Leite FMC, Freitas PSS, Bertolini SR (2022) Health policies for rare disease patients: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(22):15174. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192215174

Lowi TJ (1971) The politics of disorders. Basic Books, New York

Luhmann N (2008) Are there still indispensable norms in our society? Soz Syst 14(1):18–37. S

Lumsden JM, Urv TK (2023) The rare disease clinical research network: a model for the preparation of clinical trials. Ther Adv Rare Dis 4:26330040231219272. https://doi.org/10.1177/26330040231219272

Martin PA (2022) The challenge of institutionalised complicity: researching the pharmaceutical industry in the era of impact and engagement. Sociol health Illn 44(Suppl 1):158–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13536. (Suppl 1)

Meyers A (2016) Orphan drugs: a global crusade. Hippo Books, Hammonds, USA

Ministerio de Sanidad (2024) Estrategia en Enfermedades Raras del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/calidadAsistencial/estrategias/enfermedadesRaras/docs/Informe_EERR_pendiente_de_NIPO.pdf

Ministerio de Sanidad. Informe ReeR 2023: Situación de las Enfermedades Raras en España. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/alertasEmergenciasSanitarias/vigilancia/docs/InformeEpidemiologicoAnual_2023_ACCESIBLE.pdf

Nguengang Wakap S, Lambert DM, Olry A, Rodwell C, Gueydan C, Lanneau V, Murphy D, Le Cam Y, Rath A (2020) Estimating cumulative point prevalence of rare diseases: analysis of the Orphanet database. Eur J Hum Genet: EJHG 28(2):165–173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0508-0

Nohrstedt D, Heinmiller T (2024) Advocacy coalitions as political organizations. Policy Soc puae005, https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puae005

Orden de 15 de febrero de 1984 por la que se establecen determinadas medidas para la reinserción social de afectados por síndrome tóxico, BOE 1984, 40, 16 february 1984, 4158-4159. Ref.: BOE-A-1984-4022. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/1984/02/15/(1)

Order of development of the Ministry of Education and Science, of September 14, 1982. Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Orden de 14 de septiembre de 1982 por la que se establece el plan de escolarización de los alumnos afectados por el síndrome tóxico, BOE 1982, 221, 15 september 1982, 24894-24895. Ref.: BOE-A-1982-23305. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/1982/09/14/(2)

Ostrom E (2007) Institutional rational choice. As assessment of the institutional analysis and development framework. In: Sabatier PA (ed) Theories of the policy process. Westview Press, Cambridge, pp 21–64

Patel KK, Selker HP, Selker HP (2011) Building partnerships and coalition advocacy. In: Sessums L, Dennis L, Liebow M, Moran W, Rich E (eds) Health care advocacy. Springer, New York, NY, pp 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6914-9_8

Radcliffe-Brown AR (2002) Structure and function in primitive society, essays and addresses. Free Press, Glencoe, Illinois

Roya Decree 1893/1996, de 2 de agosto, de estructura orgánica básica del Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, de sus organismos autónomos y del Instituto Nacional de la Salud, BOE 1996, 189, 6 august 1996, 24304-24313. Ref.: BOE-A-1996-18083. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/1996/08/02/1893

Royal Decree 1276/1982, of June 18. Presidencia del Gobierno, Real Decreto 1276/1982, de 18 de junio, por el que se complementan las ayudas a los afectados por el síndrome tóxico, BOE 1982, 146, 19 june 1982, 16766-16768. Ref.: BOE-A-1982-15034. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/1982/06/18/1276

Royal Decree 1405/1982 of June 25, 1982. Presidencia del Gobierno, Real Decreto 1405/1982, de 25 de junio, por el que se crea en la Presidencia del Gobierno el Plan Nacional para el Síndrome Tóxico, BOE 1982, 152, 26 june 1982. BOE-A-1982-16122 Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/1982/06/25/1405/con

Royal Decree 1839/1981. Ministerio de Trabajo, Sanidad y Seguridad Social, Real Decreto 1839/1981, de 20 de agosto, por el que se crea un Programa Nacional de atención y seguimiento de los afectados por el «síndrome tóxico», BOE 1981, 205, 27 August 1981, 19695 a 19695. Ref.: BOE-A-1981-19244. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/1981/08/20/1839

Royal Decree 415/1985, de 27 de marzo, por el que se reestructura el Ministerio de la Presidencia, BOE 1985, 78, 1 april 1985, 8657-8662. Ref.: BOE-A-1985-5216. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/1985/03/27/415

Royal Decree 783/1982, of April 19, 1982. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Real Decreto 783/1982, de 19 de abril, por el que se reordenan los órganos administrativos con competencia relacionadas con el síndrome tóxico, BOE 1982, 96, 22 April 1982. Ref.: BOE-A-1982-9446. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/1982/04/19/783/con

Sabatier PA (1988) An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sci 21:129–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00136406

Sabatier PA (1987) Knowledge, policy-oriented learning, and policy change: an advocacy coalition framework. Knowl Creat Diffus, Utilization 8(4):649–692

Sabatier PA (1998) The advocacy coalition framework: revisions and relevance for Europe. J Eur Public Policy 5(1):98–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501768880000051

Sabatier PA (2007) Theories of the policy process. Westview Press, Boulder, United States

Sabatier PA (1991) Toward better theories of the policy process. PS Polit Sci Polit 24(2):147–156

Sabatier PA, Jenkins-Smith H (1993) Policy change and learning: an advocacy coalition approach. Westview Press, Boulder, United States

Schwarz-Tiene E (1960) Rare metabolic diseases. Minerva Pediatr 12:901–907

Song P, Tang W, Kokudo N (2013) Rare diseases and orphan drugs in Japan: developing multiple strategies of regulation and research. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 1(9):681–683. https://doi.org/10.1517/21678707.2013.832201

Takahashi Y, Mizusawa H (2021) Initiative on rare and undiagnosed disease in Japan. JMA J 4(2):112–118. https://doi.org/10.31662/jmaj.2021-0003

Tarrow SG (2011) Power in movement: social movements and contentious politics, 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

The Council of the European Union. Council decision of 15 December 1994 adopting a specific programme of research and technological development, including demonstration, in the field of training and mobility of researchers (1994 to 1998). Official Journal of the European Communities 1994, 31 december 1994, 0090–0100. Ref.: 94/916/EC. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31994D0916

Tönnies F (2012) Community and civil society. Cambridge University Press, London

Yang G, Cintina I, Pariser A, Oehrlein E, Sullivan J, Kennedy A (2022) The national economic burden of rare disease in the United States in 2019. Orphanet J Rare Dis 17(1):163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02299-5

Zanello G, Chan CH, Parker S, Julkowska D, Pearce DA (2024) Fostering the international interoperability of clinical research networks to tackle undiagnosed and under-researched rare diseases. Front Med 11:1415963. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1415963

Acknowledgements

Funding: This paper has been supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities through the following research project: ‘El sistema de salud español ante las enfermedades raras (1950–2019): profesionales y pacientes, investigación y asistencia’ PID2021-126019NB-I00. Proyectos de Generación de Conocimiento 2021. Non-Oriented Research Type B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, JRC, NPG, AP, and JARS. Methodology, JRC, EFV, AP, and NPG; Data curation, JRC, NPG, AP, EFV, and JARS. Writing—original draft preparation, JRC, NPG, NCV, and SGR. Writing—review and editing, all authors. Funding acquisition, JARS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. The article has not been produced using artificial intelligence. All contributions were made by the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Was not required as the study did not involve human participants.