Abstract

Many victims in Southeast Asia have been trapped in pig-butchering schemes in Cambodia during and after the pandemic. As new forms of scam-forced criminality via trafficking in persons operated by Chinese-related syndicates, traffickers use social platforms to pose as job recruiters and post fraudulent employment opportunities in cyberspace. Unlike other traffickers, however, scam operations target educated victims with exploitable skills and promise attractive salaries for positions in customer service, IT, computer programming, and related industries. Combining content analysis of 10 selected cases (2018–2023) and interviews with 12 police officers in Vietnam, this first mixed-methods qualitative study unveils the nature of scam-forced Vietnamese labour (SFVL) operated by Chinese cyber-enabled crimes (CCEC). Findings demonstrate the existence of structured networks with multiple layers within a single scam syndicate, with the Chinese leading their accomplices, who are either Vietnamese or from other nationalities. There are complex scenarios in the nexus of cyber-trafficking victims and many scam-forced criminality, known as overlap victim-and-offender scams. From Vietnam’s example, this study also calls for further research to focus on the nexus of (1) offenders and victims, (2) human trafficking and scam-forced criminality, and (3) technology and crime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: cyber-trafficking nexus as old bottle and new wine

Traditionally, fraud encompasses a wide range of crimes, including financial crimes such as lottery fraud, investment fraud, and romance fraud. To date, there are several crimes linked to fraud or financial offences with diverse scams via phishing emails, malware, and identity theft in cyberspace. Although cyber frauds and scams are not a new phenomenon in the long-term revolution of the information and communications technology (ICT) era, the dark side of these crimes has largely been ‘ignored and excluded from mainstream reporting’ (Button and Cross, 2017, p. 1). However, booming ICT and social media platforms have ‘encouraged’ offenders to target much larger pools of victims. Also, whenever they took advantage of high levels of anonymity to commit their criminal activities in cyberspace, it became difficult for law enforcement to monitor. Both organisational structures and modus operandi present more complex perspectives, making cyber-enabled fraud one of the most prevalent crimes globally (Cross, 2024; Garba et al. 2024). Particularly, numerous instances illustrate the practical realities of human trafficking, where individuals are lured by false online recruitment and subsequently coerced into participating in fraudulent activities after being confined within a high-security compound, enduring physical threats and torture at the hands of criminal syndicates. Consequently, it is creating ‘victim-offender overlaps’ in cyber-trafficking, as part of the non-ideal victim’s typologies (Franceschini et al. 2023; Hock and Button, 2023; Sarkar and Shukla, 2024; Wang, 2024; Wang and Topalli, 2023).

Regarding ‘victim-offender overlaps’, under the criminological lens, it reflects on the relationship between victimisation and offending (Fagan et al. 1987; Gottfredson, 1984). Although the majority of individuals who are victims of crime do not go on to commit offences, a significant number of offenders have experienced victimisation at some point (Hock and Button, 2023; Jennings et al. 2012). Accordingly, the precise count of victim offenders—those who have faced victimisation—is not clearly established, but it is evident that victimisation is widespread within the general populace. Looking for ‘victim-offender overlaps’ in cyber-enabled fraud, it is therefore necessary to review carefully in order to respond to the question: ‘non-ideal victims or offenders’ when analysing the pyramid scheme participants from different perspectives (Hock and Button, 2023). Recently, in the special issue—Relationship Fraud: Romance, Friendship and Family Frauds (Journal of Economic Criminology), guest editors temporarily categorised it into seven specific types with their relevant context, including relationship-based investment frauds, which have emergent concerns (Button and Carter, 2024; Carter, 2024). This one is referred to as ‘pig butchering’ by its perpetrators, who use intricate scripts to ‘fatten up’ the victim (gaining their trust over a time-by-time process) before taking them for all of their money - the ‘slaughter’ (Whittaker et al. 2024). Accordingly, in building a trustworthy process between the victim and the fraudster, individuals fabricate a romantic or platonic relationship, which subsequently evolves into collaborative, entrepreneurial ventures encompassing investments and gambling. The primary objective is to inflate the victim’s investments to a point at which the fraudster can withdraw significant profits as part of ending the game (Franceschini et al. 2023; Sarkar and Shukla, 2024; Wang, 2024; Wang and Topalli, 2023). This form of fraud is distinguished from traditional romance scams by the increasing evidence that many operatives involved, particularly in human trafficking, are often compelled to engage in these deceitful practices against their will (Cross, 2024; Garba et al. 2024).

As a new and complex type of cyber-enabled fraud, it is still ‘under research and is yet so essential amidst the backdrop of an escalating crime rate’ (Button and Carter, 2024, p. 1) and need to take further considerations with different approaches. Almost all recent studies in cyber-enable frauds have often been conducted with the Global North, such as Australia, Canada, the UK, and the US (Button and Carter, 2024; Button and Cross, 2017; Carter, 2024), rather than Southern perspectives, such as Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Philippines, and Vietnam. In reality, the cyber-scam industry’s shift toward human trafficking began when Cambodia’s ban on online gambling in 2019 significantly limited casinos’ and hotels’ revenues and decreased real estate prices in Southeast Asian casino towns (GITOC, 2025; OHCHR, 2023; UNODC, 2024a). In 2020, the Chinese Government’s COVID-19 response forced many Southeast Asian Chinese to return home and prevented its citizens from travelling abroad for work or vacation (GITOC, 2025; OHCHR, 2023; UNODC, 2023, 2024b). With normal revenue streams stemming, owners of hotels and casinos colluded with criminal groups to convert unused space into scamming compounds; meanwhile, the mass exit of individuals who had voluntarily participated in cyber scams led cybercriminals to begin to staff their operations with trafficked foreign nationals instead (Franceschini et al. 2023). However, while the online scam industry and ‘pig-butchering’ operations began to ‘relocate servers and officers’ to these Southeast Asian countries in the 2010s (Franceschini et al. 2023, p. 575), its perceptions and records only ‘delivered a thought-provoking presentation’ with the Western countries in the recent events (Whittaker et al. 2024, p. 1). Therefore, assessing the prevalence, nature, and trends, in combination with documenting best practices in combating and preventing these crimes from these Southeast Asia countries’ scam-online compounds, should be considered as two out of the five salient and pertinent areas of enquiry that can advance our knowledge and scholarship in this field (Ngo and Jaishankar, 2017). This article will use Vietnam as a case study to contribute to filling these research gaps in the field.

The rapid growth of ICT and the Internet has been challenging the threat of cybercrime in Vietnam. According to the Digital 2024 Global Overview Report, Vietnam had more than 78 million Internet users and at least 72 million social media accounts at the start of 2024, ranked 12th of 20 countries with the world’s highest number of Internet users (Kemp, 2024). During the current period of promoting and accelerating digital transformation, negative actors have taken advantage of the explosion in information technology to commit many online frauds (Luong et al. 2019; Nguyen and Luong, 2021). According to records from the Vietnam Information Security Warning Portal, in 2022, more than 12,935 cases of online fraud were recorded, with 2 main types, including stealing personal information and financial fraud, between 24.4% and 75.6%, respectively (Van Anh, 2023). Alongside Vietnamese offenders disrupted and arrested in almost all cases, Vietnam’s authority warned that criminal groups created by Chinese colluding with Vietnamese offenders involved in bank card data fraud and phone scams have become the most challenging (Lusthaus, 2020a, 2020b). When new technologies emerge, cyber attackers and scammers also find ways to exploit social engineering mechanisms, targeting potential victims’ psychological factors to gain their trust before committing fraud. Forms of online fraud are constantly increasing, ranging from stealing personal information to love scams and investment fraud, but the ultimate goal of these subjects is financial gain. They all target the mentality of gullibility, lack of access to information, unemployment or low income, and the greed that lies deep within each person.

Also, Vietnam has witnessed an increase in (transnational) fraud online, particularly scam-forced criminality, with the collusion between Vietnamese criminals and Chinese cyber-enable crimes (CCEC). However, the official statistics for CCEC in Vietnam have yet to be released publicly, except for some cases detected successfully by law enforcement agencies (LEA). It will likely reflect on the “iceberg” of hidden crimes relating to CCEC in/out of Vietnam. It may result from the fact that victims seldom recognise cybercrime; meanwhile, cybercrime victims do not often detect it, particularly with recent scam-forced Vietnamese labour (SFVL) cases. Some case studies in these Southeast Asian countries have been conducted by journalists, non-governmental organisations, civil society organisations, and UN bodies to examine financial losses, human rights violations, and the influence of political economy. However, there is still a lack of a criminological lens to analyse specific characteristics of ‘bi-directional victims’ or ‘victim-offender overlaps’ in cyber-trafficking. To fill this gap, focusing on Vietnam as a specific example, this is the first research to analyse the SFVL operated by the CCEC.

Methods

This study examines the nature of scam-forced criminality perpetrated by CCEC on behalf of SFVL to clarify the connection between human trafficking and cybercrime before, during, and after the pandemic. To understand these points, this research identifies three main research questions (RQs) that it deems necessary to address. They include

-

RQ1: What are the patterns of scam-forced criminality in Vietnam?

-

RQ2: What is the nexus of cybercrime and human trafficking in the Vietnam context?

-

RQ3: How does CCEC operate to exploit the SFVL?

To address the above questions, the study used mixed qualitative approaches. Firstly, concerning the case study, ten case studies from the past five years (2018–2023) have been collected based on suitable points of contact (snowballing). The author established the relevant criteria for geography-based identification to select cases that balance the distributed locations. In Vietnam, there are six main regions with multiple sub-regions in 63 provinces and metropolises, namely the Northern region (14 provinces), the Red Delta region (Hanoi and 10 provinces), the Northern Central Coast region (14 provinces and cities), the Highland region (5 provinces), South-eastern region (Ho Chi Minh City and 5 provinces), and the Mekong Delta region (13 provinces and cities).Footnote 1 However, not all SFVL occurred in every region or sub-region, and therefore, the selected cases will not be representative (see Table 1). Using content analysis, secondly, the study reviews these cases with their related scripts, which are provided as a supplementary document alongside this article. And then, some main themes with their relevant sub-themes (e.g., ‘offenders and victims’, ‘locations and distributions’, ‘human trafficking and scam’, and so on) were coded to unpack the three above RQs. Thirdly, to pinpoint the specific modus operandi and structure of these cases, the author created an initial list of key institutions and individuals to interview, including participants from law enforcement. Selection of key interviewees will follow four main criteria: (1) geographical distribution (focusing on neighbouring areas between Vietnam and its borders with China, Cambodia, and Laos), (2) ranking and role of key institutions (from headquarters to local communes with varying ranks among law enforcement agencies); (3) relevant experience (over five years in duty, prioritising officials involved in CCEC profiles); and (4) balancing the roles of key institutions, whether policymakers, practitioners, or academics. Twelve key participants from the local and national levels of LEA were interviewed. Their ranks range from captain to lieutenant colonel, with an average of eight years of service in the field. Some were investigated directly in those ten selected cases. All interviewees received the personal contact information of the researchers, including both mobile phone numbers and email addresses, to send back their signed consent forms before the interview. These interviews were conducted in Vietnamese, lasting approximately 35–55 min each, before being translated into English for analysis based on specific themes that aligned with the research questions. Here are some exampled questions applied for interviews, such as

-

What are the trends and patterns of CCEC in the pre-, during, and post-COVID-19?

-

Can you describe key Chinese personalities in any case studies you investigated relating to CCEC?

-

Can you assess how the organisational structure of syndicate members of CCEC was established and what level you think (loose, hierarchy, and/or adaptable) is in SFVL cases?

-

What and how did CCEC apply their methods in Vietnam to overcome LEA’s monitoring to commit a crime? Give an example, if applicable.

The ethics application has been supported by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Transnational Crime and Conflict Programme (Southeast Asia) of the United States Institute of Peace following review (Number #95314423P1QA00824, dated July 23, 2023).

Findings

This section combined the content analysis from the selected cases and interview perspectives. By utilising thematic analysis to identify and gather specific themes, it will illustrate the nature of Chinese cyber-enabled crimes (CCEC) that exploit scam-forced Vietnamese labour (SFVL) and related operations. Thus, the next sections cover three main subheadings to respond directly to three research questions.

Patterns of the SFVL run by the CCEC (responding to the RQ1)

This section covers two main sub-sections to respond to RQ1 (What are the patterns of scam-forced criminality in Vietnam?). The first one looks at the basic demographic characteristics of offenders and victims and clarifies their nexuses based on 10 case studies and interviewee analyses. The findings particularly point out the ‘victim-offender overlaps’ in Vietnam’s scenarios. The second one presents some specific points of relation distributions and locations regarding victims and offenders in the Vietnam context.

Offenders and Victims

From the official investigation reports of LEAs and/or court judgements, we can identify 49 Vietnamese offenders directly or indirectly involved in 10 selected cases in 2019–2023 (see Table 1). Victims are also identified in almost all cases, except for two complicated cases (CS4 and CS6) with hundreds of victims, which are difficult to count exactly from LEAs. All offenders have been prosecuted for different offences under the Vietnam Criminal Code, including human trafficking Article 150, trafficking of a person under 16 (Article 151), organising, brokering illegal emigration (Article 349), and/or extortion (Article 170); however, they are individuals or co-offenders to collude directly or indirectly with CCEC through connecting and cooperating with Cambodian counterparts without structured models such organised crime and/or mafia. No evidence confirms that any Vietnamese offenders in 10 cases belong to CCEC’s groups, although their final target is to sell Vietnamese victims to Chinese online companies in Cambodia. Only one case (CS9) reflects clearly on the victim-and-offender overlap in that the offender was a victim of SFVL operated by CCEC in Cambodia before colluding with them to recruit other Vietnamese victims to join the trap.

However, the rest of the cases also reflect the blurred coexistence between former victims and current offenders through the third person, who is often at large when investigating and prosecuting. Additionally, these cases are recorded: either the offender worked in Cambodia in different roles or did not work/come to Cambodia while committing a crime. For the former, they include translators in CS2, master chefs in CS3, and unstable jobs in CS5. “Those subjects were experienced living and working with Chinese counterparts in Cambodia in their gambling compounds, and thus, of course, they understand what CCEC needs and requires of new victims from Vietnam and how much commission they can collect from selling those victims’ (Interviewee# 6). However, in some cases, although the offender has not yet been recognised as the victim of CCEC via third-party information (e.g., friends), they knew CCEC’s company’s requirements to look for SFVL. For example, in CS1 and CS7, LEAs found it difficult to recognise offenders as the previous victims of CCEC because they had actively joined and offered their jobs in these illegal gambling groups of CCEC in Cambodia. It is a different point to distinguish between the victim-and-offender overlap and others. As a headquarters anti-cybercrime police officer added

The recent practice of fighting crime shows that many Vietnamese people have voluntarily gone to Cambodia to work in disguised companies owned by foreigners in Cambodia, particularly for Chinese groups, to commit fraud through organising online gambling and/or cryptocurrency investments (Interviewee# 2)

On the other hand, offenders in three cases (CS4, CS6, and CS8) are based in Vietnam and do not yet work and/or come to Cambodia with any CCEC groups. However, they followed the common trends—light work, high salary, to build up a ‘stunning script with honey words to focus on the honest people with poor knowledge’ (Interviewee# 5). It illustrates that geographical factors are not compulsory requirements for cybercrime, yet locations and related movements have not directly impacted their operations in cyberspace. Additionally, among leaders, sub-managers, and soldiers (the lowest rank) in CCEC, both Cambodian, Vietnamese and Chinese subjects are not necessary to meet and/or conspire in person before conducting the SFVL’s cases, which is very similar in many Chinese-related transnational computer frauds in Vietnam researched and released by others recently.

Regarding the relations between offenders, based on the current data, we can recognise that there are different scenarios for colluding and cooperating between CCEC and their accomplices, either Cambodia or Vietnam or both. The first scenario is the absence of direct relations between Vietnamese and Chinese subjects before setting the SFVL, which is very different from the ‘bureaucratic’, corporate’, or ‘organisational’ model of organised crime consisting of bosses, brothers, and relatives in the Mafia families in Italy. For example, in three cases (CS4, CS6, and CS8), all Vietnamese offenders have not established official ties with their Chinese counterparts before pushing victims into the Cambodia compounds. As one interview at China’s shared border province in the Southern province (Lao Cai) explained.

In many cases, when interrogating the Vietnamese accused to demonstrate their cohesive networks with Chinese subjects, we often failed to collect strong evidence for expanding our further actions (e.g., arrest and prosecute) for those Chinese guys. Because most Vietnamese offenders did not provide specific evidence to show when and how they connected with Chinese criminals in their cases. Instead, some of them admitted contacting via their Vietnamese relations in Cambodia, while the others contacted directly with Cambodian accomplices before and after recruiting the victims (Interviewee# 9).

As Table 1 illustrates, in all cases, Vietnamese offenders often set up or contact directly with Cambodian partners to exchange and integrate their plans to transport Vietnamese victims to Cambodia. Except for three cases (CS4, CS6, and CS8), the rest were conducted in their connective format, as similar pathways as possible with Cambodian subjects, without Chinese interventions. However, those Vietnamese criminals have also cooperated with Cambodian subjects to sell the victims into the Chinese big-butchering traps. In other words, although all cases were recorded either directly or indirectly to set up the relations between Vietnamese and CCEC’s groups, contacting/connecting with Cambodia’s counterparts (almost all cases are Cambodian, except for cases of CS4 and CS7 are Vietnamese who are permanently living and working in Cambodia) are considered as the most common pathway to maintain their SFVL’s networks.

In the second situation, several Vietnamese offenders were connected to CCEC’s subjects before, during, and after recruiting and selling the victims. The first way is direct contact with CCEC’s dots via Cambodian accomplices (CS1, CS2, CS3, CS5, and CS10). “Many offenders in our investigations confessed that although they have never met in person with Chinese counterparts, they understand what and how their accomplices need to look for when chatting via social media such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Telegram, and Weibo (for those who are Chinese language)”, as one police in headquartered level analysed (Interviewee #2). The second way is indirect contact with CCEC’s groups via Cambodia’s introductions/connections (CS7 and CS9), who are Vietnamese in Cambodia. “We are often struggling to identify exactly who are the main players to connect those Vietnamese guys to CCEC’s groups in Cambodia, as you may know, to demonstrate the accurate statements from Vietnamese offenders about their Cambodian and Chinese accomplices, we need to further confirmations which belong to our foreigner law enforcement partnerships” (Interviewee# 10). Also, those Vietnamese, who are likely to identify as one of the main players to connect and operate with the CCEC in Cambodia, are often still at large in Cambodia areas and ‘we are very difficult to track on the exact address/locations for further investigations, and thus, we could not apply any actions to arrest and prosecute unless Cambodia’s authorities help’ (Interviewee# 1).

For those victims in our current data, although we could not collect the details of the date of birth of each victim due to confidential data protection, their ages range from teenager to adult based on the final judgement’s records. Particularly, in the case of CS9, one of the victims is still under 16 years old and is classified as a child under the Vietnam Criminal Code. “Almost our database reflected on the labour ages who are young people with strong health conditions and doable capacities in the workplace environment” (Interviewee #12). Some of them (CS4 and CS9) came from the rural areas with lower living expenditures. In contrast, the others belonged to the ethnic minority group in the remote zones shared border with Laos, Cambodia, and China. The question of ‘Are those ethnic groups vulnerable targets by SFVL’s groups, either Vietnamese or Chinese subjects?’ had received unofficial confirmations from interviews:

In my case (CS4), we only identified exactly four ethnic people out of the 200 different victims when their parents contacted them directly to request help to rescue them. I do not think the offenders, either Vietnamese, Cambodian or Chinese, targeted specifically for those minorities. During interrogation, the offenders stated that they do not care where the victim comes from (ethnicity or not) because they only focus on seducing and selling them whenever collected (Interviewee# 4).

In my case (CS9), they (victims) are all ethnic groups. However, interrogating the main accused, he confirmed that his accomplice in Cambodia (a Vietnamese offender) refused those victims at the first exchange due to their original background (ethnic minorities) without an IT background. Thus, he contacted another Vietnamese accomplice in Cambodia to receive them for selling to the Chinese gambling company (Interviewee# 9).

Locations and distributions

The current data shows different locations in various regions in Vietnam, becoming the potential hotspots of CCEC in all SFVL cases. For legal techniques, we use the final locations where LEAs are officially identified with full evidence under the Vietnam criminal law and criminal procedure law to investigate and prosecute traffickers. Accordingly, there are no clear influences of geography to reflect on the recruitment of the victims to join the SFVL by CCEC because of (1) unofficial targets of specific areas/regions in our selected cases, (2) between offender and victim may never meet in person at their original destinations before connecting via social media and move/transfer in third points where differ to their hometown, and (3) lacking evidence to confirm where and why a victim of this areas much than others.

Both offenders and victims come from any commune, district, and province among Vietnam’s 63 cities/provinces. Although the current study only collected ten cases, most of our interviewers, who directly investigated these cases or were not but were working permanently in their duties to prevent and combat human trafficking and cybercrime in Vietnam’s police forces, confirmed this fluidity, adaptability and flexibility. Our database reflects the variety of geographical distributions with various regions, either metropolitan cities or remote areas (see Fig. 1). They include multiple regional locations in Vietnam, namely the northern region (Tuyen Quang and Thai Nguyen), northern central region (Nghe An and Ha Tinh), central highlands region (Gia Lai, Dak Lak, and Lam Dong), southern region (Dong Nai and Ho Chi Minh City), and southern east region (Tay Ninh).Footnote 2 These locations cover offenders and victims from rural provinces and high ethnic minority populations, except for the two industrial zones (Dong Nai and Ho Chi Minh City). As the above section analysed (offenders and victims), there is insufficient evidence to confirm ethnic-based focusing from offenders in almost all SCVL’s cases involving indirect (rather than direct) CCEC groups. Although there are two out of ten cases of victims who come from ethnic minorities, it is an unofficial demonstration of the trafficker’s aims in seeking and selling the victims. However, many of our interviewees argue that ethnic minorities are the least at risk of being trafficked because they live in remote areas where the geographical isolation along with the underdeveloped socio-economic conditions led to low levels of education, limited awareness, and easy-to-trust people, which increases the risk of becoming trafficking victims for ethnic minorities (Interviewee# 1,2, 5, and 11). In addition, unemployment and lack of stable employment in rural areas are also a risk factor that causes many people to become victims of SFVL’s trafficking (Interviewees # 6,10 and 12). On the other hand, some interview reflections based on their direct investigation in case studies show that most of the teenage victims living in rural areas with limited knowledge/information to update the SFVL’s operations are often likely to be enticed by unverified online information with sweet words. At the same time, they cannot distinguish between truth and falsehood (Interviewees # 3,4,7,8 and 9).

Human trafficking and scam online (responding to the RQ2)

The current findings stand for the previous studies regarding the ‘victim-offender overlaps’ in cyber-trafficking (Franceschini et al. 2023; Sarkar and Shukla, 2024; Wang, 2024; Wang and Topalli, 2023). Social media and its application have been recorded as the most popular pathways to connect offenders and victims in scam-forced criminalities in Vietnam. Table 1 shows that offenders used social media as the dominant tool to look for, recruit, and exchange with potential victims, accounting for 100% of all selected cases in Vietnam. They are contacted and discussed via social media in almost all situations to bring those trafficked victims to join their scam compounds. Vietnamese groups predominate on Zalo and Facebook, while Weibo is often prioritised to connect offenders who can speak Chinese (CS2) with their CCEC managers.

This study reflects some specific factors on the relations between human trafficking and scam-forced criminality. Firstly, the pandemic and its related issues are one of the specific factors impacting the trend of this concern. Among the several negative influences of the pandemic, unemployment with low rates of job opportunities has been considered the main factor leading to local people facing economic conditions in Vietnam. As a usual cycle, they must look for their potential chances to get a job and secure their normal life while the state is facing a dilemma situation to recover society. Traffickers often take these disadvantageous issues to set up and look for their potential victims. In one interview, a leader in a headquartered agency analysed:

Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in our country over the past 2 or 3 years, domestic human trafficking crimes have tended to increase, become complex, and operate across lines and provinces with sophisticated methods. Particularly, they design and use social media platforms to attract and recruit workers in many regions with job advertisements: Simple job, High salary! (Interviewee #1).

It is also common in many remote areas and/or poor economic zones across the borderland’s communes between Vietnam and its shared neighbours, including Cambodia, China, and Laos. One police officer at the Vietnam-Laos border highlighted

According to several victims, finding jobs in their hometowns has become difficult due to the COVID-19 pandemic. While struggling to make a living, workers took to social networks to find a job and were introduced to Cambodia to work with offers – ‘simple job, high salary’. Therefore, in our area, many cases have been recorded in which people followed the invitation and instructions of the subjects to cross the border to Cambodia to look for jobs illegally. However, when they arrived, they recognised that they had been deceived. In some cases, they asked their relatives for help and had to accept having to spend a large sum of money to ransom them back home (Interviewee# 11).

Alongside the pandemic’s influences, secondly, there are also questions about the impacts of export labour or labour migration through official programmes between Vietnam and Cambodia under their bilateral partnership or the Mekong dialogue in economic development. There is unclear evidence to demonstrate connections between scam locations and places through official programmes of the export labour, where most victims come from rural areas with lower living standards, such as Nghe An, Ha Tinh, Dak Lak, Gia Lai and Tuyen Quang. However, there are three specific points to need notes for this one. First, almost all those labourers often have insufficient economic conditions to apply for regular/official migration through registered recruitment agencies, which is time-consuming and expensive. Second, they also have poor education and professional skills with limited knowledge of the risks of exploitation involved in labour migration, which stems from the inadequate dissemination of information from both migration agencies and local authorities when recruiting. Third, during the pandemic, with the restricted movements, they are often looking for job vacancies on social media rather than publishing the official reports of the state authority. “I think it is considered as the potential targets for cybercriminals to design and release their fake adverts to hook those victims to join their SCVL’s operations, although they (offenders) do not know where the victims come from” (Interviewee# 12), as one police officer explained.

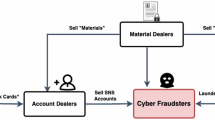

The scam-forced Vietnamese labour network run by Chinese Cyber-enabled crimes (responding to the RQ3)

This section will borrow the SmartArt graphic in Microsoft Office, a visual representation of information and ideas, to present the detailed structure of SFVL operated by CCEC. Accordingly, some layouts (such as organisational chart Venn diagrams) portray specific kinds of information to show overlapping relationships among Chinese leaders/bosses and their coordinators (mostly Vietnamese offenders) in each SFVL case (see Fig. 2).

Our current data has not officially reflected any Chinese offenders being arrested and prosecuted under the Vietnam criminal code, either human trafficking (Article 150) or organising or brokering illegal emigration (Article 349), as of conducting this study (Aug-Nov 2023). Thus, we cannot confirm the specific role of the high-ranking organisers (level 1 – big boss) and how they control and manage their networks and operations, including SCVF. However, we drew those people at the central point in the relationship of the organisational chart Venn diagram. However, Table 1 demonstrated that Vietnamese offenders in Vietnam or Cambodia in all case studies have been connected indirectly to Chinese accomplices who are often identified as managers (level 2) or sub-managers (level 3) rather than the top-ranking organisers. As one police officer at the headquartered level analysed

Under the regulations of criminal procedure law and policing rules, we are the principal investigator in complicated cases with transnational scope among multiple countries in the region. Accordingly, in some recent cases relating to SFVL in Cambodia, we had strong evidence to identify the Chinese involvers in this case. However, the nature of these CCEC groups with structured networks through hosting the leaders/organisers (big bosses) as organised crime/mafia is necessary for more evidence to be shares and provided from our LEA’s counterparts in Cambodia and China. Only on Vietnam’s side can we not confirm this point officially (Interview #1).

Therefore, as an alternative option to replace analysing all six levels in CCEC’s network without legal evidence and persuasive documents, in this study, we used one typical case (CS6) to illustrate the organisational structure of SFVL syndicates leading from CCEC (see Fig. 3). Five main reasons chose this case, including (1) the most offenders arrested and prosecuted among ten selected cases, (2) the nature of the complicated cases with the largest cyberspace across almost all provinces/cities in Vietnam that were identified and confirmed by the highest LEA bodies in Vietnam (ministry of public security), (3) involving all offenders come from Vietnam, Cambodia and Chinese (although Chinese leaders are still at large at the completed investigation from Vietnam’s LEA), (4) the most crowded victims counted (over 1000) but unknown identifications, and (5) the highest profitable costs were fraudulent from criminals (over VND67 billions or around USD3 millions).

According to the police document, from March 2022 to January 2023, two subjects commonly known as “Dwarf” and “White” (unknown identity, Chinese background), as the managers (level 2), colluded with Vietnamese subjects to establish a disguised company, run by Chinese subjects. To some extent, thus, “our hypothesis is the real big boss (level 1) may be neither Dwarf nor White; alternatively, their higher-ranking accomplices can still be behind the scenes if our anticipation were correct” (Interviewee# 2). This company is located at the B7, Venus’s area (Svay Rieng province, Cambodia; from October 2022, moving headquarters to H’s Block, the King Crow area, and Svay Rieng province); the organisation uses cyberspace to seize the property of many Vietnamese citizens fraudulently. “Dwarf” and “White” have recruited nearly 100 Vietnamese (victims first, fraudsters late) to Cambodia to work through social networking sites, posted articles promising high salaries, attractive incentives to recruit employees or encourage working employees to attract more friends and relatives (victim’s second version) went to Cambodia to work together.

After recruiting employees to take them to Cambodia, “Dwarf” and “White” agreed to pay USD800/person/month in the agreement. Also, each member will receive an extra commission on the money misappropriated from the victims whose accomplices (Chinese, level 3—sub-managers) have designed the integrated format with those victims. While “Dwarf” and “While” cover the recruitment duties, including arranging for employees to eat, live, and work together in one building, the others (Chinese, level 3–sub-managers) will deploy the training of trainer (ToT) model which they focus on training and instructions those victims on committing fraud, such as having employees read documents, “scripts”, and fraudulent dialogue. “Seemingly, they have already tested scripts carefully before instructing us because all dialogue, conversation, greeting, and negotiation are very formative and constructive processes” (Interviewee #2). Again, they will request those Vietnamese victims to work with employees who are also Vietnamese and have worked with these scripts to double-check the newbie’s skills and knowledge. After that, their “Dwarf” and “White” colleagues (Chinese, level 4 – supervisors/leaders) managed and divided those new employees into teams and groups to commit fraud and appropriation of property.

In particular, under at least two supervisors’ groups, there are two main sub-groups, known as “telesales” and “sales”, which are established with support from captains (level 5) who are either Chinese or Vietnamese (who are experienced in working with Chinese groups). Accordingly, about 20 “telesales” employees were assigned to call and text via Facebook to lure and entice victims to participate in online work. Those employees will be paid from VND 100,000 to 300,000/day (around USD 5-15). If the victim agrees, their personal information, such as phone number and Facebook account address, will be transferred to the “sales” staff for the next step. The “sales” staff group of about 80 people is divided into 3 groups: A, B, and C. Each group is divided into different teams, in which each team has 3 employees assigned to manage one computer and one phone. “Under their code of conduct, they called machines 1, 2, and 3 to easily manage and control their soldiers (level 6 – victims)”, as an investigator explained (Interviewee#2). Every day, group leaders (level 5 – captains), including Vietnamese offenders, directly assign work to employees to carry out fraud tasks. Specifically, machine 1 (employee) received information about the victim from the “telesales” group, called and texted via the social network Facebook to entice and entice the victim to follow and click favourites (also known as “like” or “heart”) on the TikTok application, Facebook network, listen to MP3 music to get paid. When the victim agrees to participate, the information will be transferred to machine 2, instructing the victim to click favourite on TikTok or listen to MP3 music. By doing this, those victims could be paid VND10,000 to 50,000/time (under USD3). Then, they called those victims to transfer money to charity for the SOS Children’s Village by setting up an account on the Corona website with an interface like online gambling websites on the Internet, a server located in Cambodia. When the victim transfers money to a bank account, the subjects send a contract from a financial company (fake contract) via the Telegram application, pledging to ensure 100% of their capital. After that, the subjects instructed the victim to contact via the Telegram application to meet the “expert” (machine 3). Machine 3 (employee) instructed the victim to transfer money to the bank account to get points in the account established on the Corona website (one-point equals VND1,000), then read the over-under or even-odd betting order for the victim to place a bet. By doing this, victims will be promised to enjoy commissions between 30 and 60%.

Lastly, under the Chinese supervisor’s team, a group of employees (Chinese only) is set up to serve all administrative duties. Our current data shows at least four main duties for those groups. First, they are assigned the task of providing bank account numbers to employees of groups A, B, and C for victims to transfer money. They also manage bank accounts to transfer money to victims who have completed their initial tasks. “They requested Vietnamese accomplices to open at least 18 different bank accounts in Vietnam’s territory to transfer money from their victims”, as the investigator analysed. Second, they manage the Corona “app” and its related website’s domain to transfer points to victims’ accounts. Yet, web administrators have the right to intervene and/or edit password information, open bank account numbers or lock the account. They can even prevent the victim from withdrawing money by creating technical errors. Third, in timekeeping, they will follow up on the timeline and schedule of employees (machines and others). Fourth, they also handle salary calculation and its related distribution to employees at all stages.

Discussions

Regarding trend and pattern (RQ1), Vietnam has been considered both a source and a transit for human trafficking in the region for many years (Nguyen et al. 2020; Nguyen and Luong, 2023). Particularly, detecting this type of crime in the country has received much attention since the Essex tragedy in 2019, when all 39 Vietnamese victims died in the lorry after being trafficking by organised crime groups (Luong, 2021). Regarding domestic routes, the situation of human trafficking among regional areas, from rural and/or remote locations, including ethnic groups to urban and/or industrial zones to transfer the third countries in Asian, Europe, and beyond has been considered as one of the challenged concerns for Vietnam authorities (Nguyen et al. 2020). Recently, many forms of human trafficking connected/swapped with scam forced labour have occurred in Southeast Asian and Mekong countries, including Vietnam (GITOC, 2025; U.S. Department of State, 2024; UNODC, 2024a, 2024b). However, when interviewing, many officials from LEA’s provincial levels assessed that the phenomenon of domestic trafficking for purposing SFVL existed before COVID-19. Recently, the increase in SFVL cases is mainly due to those victims who organised actively to escape from CCEC’s groups in Cambodia to return to Vietnam or LEAs rescued them in some cases. Explaining the reason for this increased trend in cases of human trafficking crimes relating to SFVL, most of the interviewed officials argued that the impact of COVID-19 (e.g., limited employment, restricted movement, and online environment) on a change in structure, operation, and pattern. Consequently, the COVID-19 pandemic fuelled economic desperation, making people more susceptible to trafficking, as recent reports from the United Nations and the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime (GITOC, 2025; UNODC, 2024a, 2024b) have indicated. Although it is difficult to know for certain how many people have been trafficked into scamming, the United Nations estimated that over 100,000 victims are being held in compounds in Sihanoukville City, Cambodia, alone, as of September 2022, including hundreds of Vietnamese (OHCHR, 2023).

In terms of the RQ2 (human trafficking and scam activities), as with many forms of human trafficking and/or scam-forced criminality via trafficking in persons operated by Chinese syndicates, traffickers posing as job recruiters post fraudulent employment opportunities on Facebook, Telegram, and job descriptions (Franceschini et al. 2023; Sarkar and Shukla, 2024; Wang, 2024; Wang and Topalli, 2023). These reflect in almost all selected cases in this current study, when most victims reported to the police that they had been forced to engage in scam activities under the Chinese syndicates’ monitoring. Unlike other traffickers, however, scam operations target educated victims with exploitable skills, like English or Chinese proficiency or a technological background, and promise attractive salaries for customer service jobs, IT, computer programming, and related industries (GITOC, 2025; UNODC, 2023, 2024a, 2024b). Scam operators usually cover workers’ travel, but upon arrival in Cambodia, they confiscate the victims’ passports and demand that the victims pay back their “debt” (Domingo et al. 2023; OHCHR, 2023). This coercion is often accompanied by physical and sexual abuse, restrictions on movement, and starvation; meanwhile, some female victims are also made to serve as models in video chats with prospective scam victims or forced into sex work if unable to meet their scamming quotas (Domingo et al. 2023; USIP, 2024). Although the current findings have not yet confirmed officially the ‘victim-offender overlaps’ in all ten cases (Franceschini et al. 2023; Sarkar and Shukla, 2024; Wang, 2024; Wang and Topalli, 2023), almost all interviewees acknowledged this specific trend of cyber-trafficking in Vietnam. However, to clearly answer the questions of ‘non-ideal victim or offender’ (Hock and Button, 2023), empirical studies from different studies should be encouraged and conducted in the future.

Discussing the role and influence of Chinese syndicates for scam-trafficking nexus (RQ3), based on the current database and in-depth interviews, the nexus of human trafficking in domestic regions and SFVL run by CCEC has increased considerably in recent years. These cyber-enabled scam networks are often operated and hosted by powerful master Chinese syndicates who are located in various geographies across the region, with many operations based just over the border areas among Cambodia, Thailand, Laos and Myanmar (Wang, 2024; Wang and Topalli, 2023). Many of these Chinese criminal networks are steered by organised crime groups through using “cryptocurrencies, the dark web, and other technologies” to deploy other criminal activities, “including drug trafficking, money laundering, kidnapping, and unlawful detention” (UNODC, 2024a, pp. 20–21). These groups were founded by Chinese individuals or a few couples, including Taiwanese, with help from Vietnamese and others to recruit, manage, and direct hundreds of Vietnamese employees working in Cambodia to commit fraud on mainly Vietnamese targets (OHCHR, 2023; U.S. Department of State, 2024; UNODC, 2023, 2024a). The current data (ten selected cases) has not yet confirmed any single organisation or multiple organisations run by the Chinese to conduct their cyber-enabled offences in Vietnam’s internal territories, like an organised crime group with clear structures and a hierarchical model. However, the example of the complex case (CS6) should realise the diversity of modus operandi of those cybercrimes to deploy their criminal activities, as “featuring highly organised structures and open crime systems with the main purpose of procuring economic interests” (re-quoted by official communication from the Ministry of Public Security of China, UNODC, 2024a, p. 20). Our current findings illustrated that among four specific roles in cybercrime organisations, namely “core members”, “professional enablers”, “recruited enablers”, and “money mules” (Leukfeldt et al. 2017), those Vietnamese subjects (almost) and/or Cambodian (few) should be pencilled as the “recruited enablers” who provide core members (Chinese groups) by looking for potential victims and recruiting them into the network. However, to confirm the level of these CCEC operations (loose, hierarchy, or adaptable), we need furthermore larger database from different countries in the region, particularly in Cambodia and China, to ensure reliable and transparent outcomes.

Alongside three RQs discussions, based on the current findings, there are some main barriers to lead to limited reflections and even hidden situations on the nature of CCEC in Vietnam. First, most criminal justice agencies (court, procedural, and police) have not yet established their unit/branch separately to combat CCEC offences/offenders. In Vietnam, nationality-based identification is not applied to offenders; instead, they will be coded automatically as ‘foreigner’ offenders. In other words, these records are often not saved as independent classifications, making it difficult to collect data. Alternatively, the author must manipulate it with his specific criteria listing (e.g., Chinese-related offences, cybercrime, human trafficking and so on). Second, the demographics of Chinese suspects/offenders in these SFVL cases have not been detailed in their records due to slow/limited feedback from Chinese counterparts to respond to Vietnamese LEAs. Most Chinese relations in this report are still at large at the final investigations (by police) and/or the trial stages (by court). Third, all those Chinese ‘big’ bosses in this study are still at large and have not yet been arrested and prosecuted under Vietnamese laws, which led to difficult confirmation of the whole of the ring. Post-pandemic, several crackdowns in/out of China territories have shown the complications of the trends and patterns of Chinese-related offences regarding cybercrime, particularly online scams and forced criminality across Southeast Asia and the Mekong (GITOC, 2025; OHCHR, 2023; UNODC, 2023, 2024a). Fourth, the limited mutual legal assistance among countries to handle timely SFVL led to the slow process of identifying the Chinese roles, and even, they escaped before LEA began. These campaigns have been only operated through bilateral/multilateral cooperation between the Chinese and their counterparts LEA when preferring to rescue Chinese victims, apart from the rest (Franceschini et al. 2023; Wang and Topalli, 2023). Finally, the lack of the voices of victims and/or offenders in all ten selected cases is another limitation that needs to be addressed to improve the objective and sufficiency of further research. In other words, if available, the triangulated voices among victims, offenders, and police should be paralleled in the future. These five points are considered the limitations of the current research, and we call for further consideration in other studies.

Conclusions

While economic growth and regional integration have created many positives since implementing the Renovation Period in the 1990s, Vietnam has faced transnational crime threats. Further, the region’s geographic nature and the process of improving infrastructure, communication and transportation have increased opportunities for traffickers to operate transnationally. Moreover, the booming of information technology with its applications in cyberspace has been challenging, with potential cybercrime threats in Vietnam. Notably, Vietnam has witnessed the growth of cybercrimes, particularly scam-forced criminality with collusion from outsiders, including Chinese cyber-enabled crimes (CCEC). The current findings pointed out that CCEC is not a new phenomenon and has occurred and operated in Vietnam since the 2010s, when Vietnam’s LEAs detected and successfully investigated several CCEC syndicates. However, the use of SFVL in Cambodia facilitated by CCEC is new. Accordingly, several cyber-enabled crimes were committed by the Chinese and their accomplices (Vietnamese or non-Vietnamese) pre-, during and post-pandemic period that reflected many Vietnamese victims in the pig butchering scam or forced scam labour in Cambodia. As one of the primary tools, those scams have appeared on social networking sites about sending workers abroad to work with promises of “simple job, high salary”, rather than applying social media grooming or other tactics. Many victims have been tricked into going to Cambodia, and then they are sold to CCEC’s entities. This extremely dangerous crime has been an alarming situation recently, affecting the security, social order, and safety in localities. Many subjects have been prosecuted for human trafficking and/or organising and brokering for others to flee abroad or stay abroad illegally under Vietnam’s laws. However, as of the writing of this article, the situation and developments of this type of crime have not shown specific signs of improvement and are becoming increasingly sophisticated and complex, with many victims still being “trapped”. It is considered an emergent situation with unpredictable trends in mainland Southeast Asia in general and Vietnam in particular. Still, it also poses great challenges for authorities and society to prevent and fight. In the future, applying the criminology lens, such as crime script analysis and 25 techniques in crime prevention, should be encouraged to fully understand the specific activities of cyber-trafficking connections and to identify the relevant interventions to detect these threats.

Data availability

The datasets, including ten case studies, used in this article are available in the Supplementary File.

Notes

Currently, Vietnam’s administrative geography has changed, reducing the number of cities/provinces to 34 as of 1 July 2025, in which some locations in this study have been merged with others under new names.

Our data collection excluded the Mekong and Red River Delta provinces.

References

Button M, Carter E (2024) Relationship fraud: Romance, friendship and family frauds. J Econ Criminol 4(100069):1–3

Button M, Cross C (2017) Cyber Frauds, Scams and Their Victims. Routledge

Carter E (2024) The Language of Romance Crimes: Interactions of Love, Money, and Threat. Cambridge University Press

Cross C (2024) Romance baiting, cryptorom and ‘Pig Butchering’: An evolutionary step in romance fraud. Curr Issues Crim Justice 36(3):334–346

Domingo P, Denney L, Alffram H, Jesperson, S (2023) Trafficking for Forced Criminality: The Rise of Exploitation in Scam Centres in Southeast Asia. ODI Global Advisory. https://cisp.cachefly.net/assets/articles/attachments/92159_the_rise_of_exploitation_in_scam_centres_in_southeast_asia_hammbwe.pdf

Fagan J, Piper E, Cheng Y-T (1987) Contributions of Victimisation to Delinquency in Inner Cities. J Crim Law Criminol 78(3):586–613

Franceschini I, Li L, Bo M (2023) Compound Capitalism: A Political Economy of Southeast Asia’s Online Scam Operations. Crit Asian Stud 55(4):575–603

Garba K, Lazarus S, Button M (2024) An Assessment of Convicted Cryptocurrency Frauders. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 1-18

GITOC (2025) Compound Crime: Cyber Scam Operations in Southeast Asia. Global Iniative against Transnational Organized Crime (GI TOC). https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/GI-TOC-Compound-crime-Cyber-scam-operations-in-Southeast-Asia-May-2025.pdf

Gottfredson M (1984) Victims of Crime: The Dimensions of Risk. H.M. Stationary Office

Hock B, Button M (2023) Non-ideal victims or offenders? the curious case of pyramid scheme participants. Vict Offenders 18(7):1311–1334

Jennings W, Piquero A, Reingle J (2012) On the overlap between victimization and offending: A review of the literature. Aggression Violent Behav 17:16–26

Kemp S (2024) Digital 2024: Vietnam. Data Reportal. Retrieved 10 June from https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-vietnam?rq=Vietnam

Leukfeldt R, Lavorgna A, Kleemans E (2017) Organised cybercrime or cybercrime that is organised? an assessment of the conceptualisation of financial cybercrime as organised crime. Eur J Crime Policy Res 23:287–300

Luong HT (2021) Undocumented Vietnamese Migrants: What Is Going On Since the Essex Tragedy? Institute for Asian Crime and Security (IACS). Retrieved 7 October from https://theiacs.org/undocumented-vietnamese-migrants-what-is-going-on-since-the-essex-tragedy/?print-posts=pdf

Luong HT, Phan DH, Chu VD, Nguyen QV, Le TK, Hoang TL (2019) Understanding Cybercrimes in Vietnam: From Leading-Point Provisions to Legislative System and Law Enforcement. Int J Cyber Criminol 13(2):290–308

Lusthaus J (2020a) Cybercrime in Southeast Asia: Combating a Global Threat Locally. Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). https://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/ad-aspi/2020-05/Cybercrime%20in%20Southeast%20Asia.pdf?naTsKQp2jtSPYsWpSo4YmE1sVBNv_exJ

Lusthaus J (2020b) Modelling cybercrime development: The Case of Vietnam. In R. Leukfeldt & T. Holt (Eds.), The Human Factor of Cybercrime (pp. 240-257). Routledge

Ngo F, Jaishankar K (2017) Commemorating a decade in existence of the international journal of cyber criminology: A research agenda to advance the scholarship on cyber crime. Int J Cyber Criminol 11(1):1–9

Nguyen VO, Le QT, Luong HT (2020) Police failure in identifying victims of human trafficking for sexual exploitation: An empirical study in Vietnam. J Crime Justice 43(4):502–517

Nguyen VO, Luong HT (2023) Assessing the hotline services on child trafficking victims: An analysis of Vietnam. J Police Crim Psychol 38(4):1–13

Nguyen VT, Luong HT (2021) The structure of cybercrime networks: Transnational computer fraud in Vietnam. J Crime Justice 44(4):419–440

OHCHR (2023) Online Scam Operations and Trafficking into Forced Criminality in Southeast Asia: Recommendations for a Human Rights Response. Office for the United Nations Human Rights High Commissioner (OHCHR). https://bangkok.ohchr.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/ONLINE-SCAM-OPERATIONS-2582023.pdf

Sarkar G, Shukla S (2024) Bi-directional exploitation of human trafficking victims: both targets and perpetrators in cybercrime. J Human Trafficking, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2024.2353015

U.S. Department of State (2024) 2024 Trafficking in Persons Report: Vietnam. https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/vietnam/#:~:text=Authorities%20repatriated%20more%20than%204%2C100,citizens%20and%20several%20third%20country

UNODC (2023) Casinos, Cyber Fraud and Trafficking in Persons for Forced Criminality in Southeast Asia. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/documents/Publications/2023/TiP_for_FC_Summary_Policy_Brief.pdf

UNODC (2024a) Casinos, Money Laundering, Underground Banking, and Transnational Organized Crime in East and Southeast Asia: A Hidden and Accelerating Threat. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/documents/Publications/2024/Casino_Underground_Banking_Report_2024.pdf

UNODC (2024b) Transnational Organised Crime and the Convergence of Cyber-Enabled Fraud, Underground Banking and Technological Innovation in Southeast Asia: A Shifting Threat Landscape. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). https://www.unodc.org/roseap/uploads/documents/Publications/2024/TOC_Convergence_Report_2024.pdf

USIP (2024) Transnational Crime in Southeast Asia: A Growing Threat to Global Peace and Security. United States Institute of Peace (USIP). https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2024-05/ssg_transnational-crime-southeast-asia.pdf

Van Anh (2023) The Most Common Types of Scams on Vietnam’s Cyberspace. Vietnamnet. Retrieved 2 February from https://vietnamnet.vn/en/the-most-common-types-of-scams-on-vietnam-s-cyberspace-2100300.html#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20the%20Vietnam%20Information,personal%20information%20and%20financial%20fraud

Wang, F (2024). Victim-offender overlap: the identity transformations experienced by trafficked Chinese workers escaping from pig-butchering scam syndicate. Trends Organized Crime, 1-32

Wang F, Topalli V (2023) Persuasive schemes for financial exploitation in online romance scam: An anatomy on Sha Zhu Pan (杀猪盘) in. China Vict Offenders 18(5):915–942

Whittaker J, Lazarus S, Corcoran T (2024) Are fraud victims nothing more than animals? Critiquing the propagation of “pig butchering” (Sha Zhu Pan, 杀猪盘). J Econ Criminol 3(100052):1–8

Acknowledgements

The author would like to sincerely thank the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) for its financial support in conducting this independent study on the topic. I especially appreciate the helpful recommendations from Jason Tower, Aizat Shamsuddin, and various participants who shared their views during the USIP’s latest dialogues in Bangkok, Thailand, for reviewing and contributing to my USIP report and this early manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author’s participation in a wider project on transnational crime in Southeast Asia, spearheaded by the United States Institute of Peace (USIP), benefited this study. The author declares no potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the USIP (Number #95314423P1QA00824, dated July 23, 2023). The ethical approval permits the researcher to conduct fieldwork and interviews, collect and analysis data.

Informed consent

All participants were adults, and no vulnerable individuals were involved. By contacting participants through personal introductions, informed consent was obtained verbally prior to the interview in August 2023. Interview participants were fully informed of their right to withdraw from the interview at any time, after the researcher had explained this option. They answered our questions voluntarily and without any obligation. While the anonymity of participants was assured, they were not offered to record; instead, the researcher took notes. Additionally, to ensure privacy and confidentiality, this study excluded identifying details of offenders, victims, and officers (including names, dates of birth, identity numbers, and biometric characteristics) from the interviews with participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luong, H.T. “Simple job, high salary”: unveiling the complexity of scam-forced criminality in Southeast Asia. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1305 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05605-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05605-1

This article is cited by

-

An Artificial Intelligence-Driven Temporal Network Analysis of Myanmar’s Cyber Scam Ecosystem

Asian Journal of Criminology (2026)