Abstract

This study focuses on Chinese female artists, exploring how they express specific female viewpoints through fibre artworks. Discussions on gender roles have long been contentious among researchers. Due to historical roots, thought patterns, and power structures, males have historically dominated, resulting in relatively less attention to females. Such topics are unavoidable in artistic creation. This empirical study adopts a qualitative research methodology, conducting 20 semi-structured interviews with 11 freelance artists and 9 college art teachers. It emphasises women’s ethical concerns in establishing moral relationships, shifting from core moral concepts centered on caregiving to those influenced by interpersonal relationships. Qualitative research combined with thematic analysis was employed, gathering data through semi-structured interviews, coding, and categorising interview content using NVivo software to present three final themes: women’s concern, social concern, and nature concern. Under the care and guidance, this study explores how Chinese female artists utilise fibre materials to convey specific viewpoints and thoughts. It offers a new perspective on understanding the emotional expressions of female artists, contributing to advancements in contemporary art and women’s practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Feminist fibre art is more than just textiles and threads, according to Brinkman (2024).

It’s a movement that challenges traditional perceptions of textile art. Female artists have been at the forefront of this revolution, using their work to question societal norms and elevate what was once considered women’s work into the realm of fine art (Brinkman, 2024). In textiles and fabrics, modern people have created a form to express human emotions, known as the field of fibre art. It attracts people’s attention with a completely new appearance and inspires their thoughts (Xu, 2010). Similarly, Wang (2011) states that today’s fibre art is no longer limited to singular forms and media but continuously imitates and integrates various expressive techniques towards a complex diversity. Fibre art, as a special cultural symbol, has embodied a humanistic spirit primarily centered around women for centuries. It narrates the life experiences, aspirations and pursuits of humanities disciplines, especially women, and their expectations for self-transformation, societal and global changes.

In the evolution of fibre art, female artists have significantly outnumbered males in participation (Liu, 2019). This is mainly due to the close association of fibre art materials and techniques with traditional women’s handicrafts. In this interview, Chinese female artists express materials such as cotton, yarn and silk, like women, exhibit qualities of softness, delicacy and comfort. Materials like hemp and iron wire seem to showcase women’s toughness and indomitable spirit. Women have a profound understanding of fibre materials, perfectly expressing the emotional world of women. Additionally, women are more easily attracted to the process of using fibre materials.

In the field of fibre arts research, most scholars conduct their studies within the domain of art itself. Specific topics include the analysis of fibre materials used by artists, such as comprehensive discussions on soft and hard materials, the continued use of traditional materials in contemporary art, and the adaptation of new materials in current contexts. Some researchers focus on patterns in fibre arts, depicting the evolution of these patterns symbolically and exploring the continuity and development of traditional patterns from Chinese ethnic minorities. Others examine the manifestation of concepts in contemporary fibre arts, often exploring development through postmodernism and feminism. Lastly, some scholars discuss the intersection of women and fibre arts, exploring topics from textiles to feminine perspectives, integrating ethics and discussing female artworks. This study aims to offer a more nuanced perspective, focusing on women’s viewpoints and ethical considerations. Like previous research, this study aims to better assist the development of Chinese fibre arts. What sets it apart is the integration of interdisciplinary analysis and discussion of research outcomes, providing a more profound examination using case studies of Chinese female artists’ fibre artworks.

Scholars of care ethics agree that the prevailing individualistic, rationalist and instrumentalist mindset, coupled with anthropocentrism, has led to a moral deficit in contemporary Western societies (Haraway 2008, 2016; Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017). Historically, women have continuously been in a submissive position to men, who have controlled society for a significant amount of time under the conditions of private ownership throughout the long history of development. In that case, almost all authoritative positions in various fields of society are occupied by men, and a set of male standards has been established to measure and evaluate women (Liu, 2012). The male identity represents the core values of society, and the idea of male superiority and female inferiority has become a fact deeply ingrained in the public consciousness.

In the process of social science’s continuous pursuit of social equality, justice and its active promotion of the dissolution of sexism. Traditional ethics has rediscovered the deep embeddedness of sexism in the system of knowledge production and research paradigm (Liu, 2012). For a long time, the dominant cognitive framework has habitually viewed the world from a male perspective, thus obscuring the uniqueness of the female subject’s experience, as Chodorow (1995) points out, ‘Girls emerge from this period with a basis for empathy built into their primary definition of self in a way that boys do not’. (p. 167). This argument suggests that girls, as opposed to boys, internalise empathy as an important part of their self-identity during their early development. They are more consistently connected to the external object world in the process of self-construction and accordingly develop internal psychological structures that distinguish them from men. As a result, women’s moral judgements display an ethical orientation centred on empathy and caring (Xiao, 1999), in contrast to men’s judgemental patterns, which are more oriented towards justice and rules.

In the study of fibre arts, discussions on female artistic works are somewhat limited. Contemporary Chinese female artists, when engaging with linear materials, find many existing experiences inadequate as references (Yuan, 2021). This is because contemporary artists prioritise the experiential aspects of the process and emotional connections with materials. Unlike before, the intrinsic beauty of various materials is what researchers today need to discover, explore and expand through artists’ works (Yuan, 2021). Yuan further adds that what the material itself gives is not important; what matters is what artists do during the creation of their artworks, whether they inspire deeper artistic feelings and associations in people, provide hints to viewers and interpret patterns (Yuan, 2021). This echoes Liang’s (2021) assertion that under the influence of contemporary art, fibre artists mostly focus on exploring the formal language of fibre art while neglecting its cultural characteristics. In today’s diverse art landscape, views on fibre art should consider interdisciplinary perspectives more broadly. Thus, this study begins with two questions: (1) What leads Chinese female artists to choose fibre materials to express their ideas? (2) From the perspective of feminist care ethics, what specific thematic concepts do Chinese female artists express?

Johnson and Christensen (2012) state that qualitative data collection methods are designed to gather authentic and insightful information that aids in comprehending and evaluating the extent of involvement and behaviour patterns. Therefore, the method of collecting data is a semi-structured interview, and the method of analysing data is thematic analysis.

Semi-structured interviews are well known for being highly effective in qualitative research because they allow researchers to obtain extremely personal information directly from respondents. Because people are generally more forthcoming in a private, one-on-one context than in a group setting, these interviews are crucial for examining the opinions, motivations, beliefs and experiences of participants. They also prove to be extremely advantageous for gathering data on sensitive issues.

Thematic analysis is chosen to analyse data in the present research. To apply this method, recorded interviews were first transcribed verbatim because no set of rules exists, and no specific method is prescribed for generating a transcript. Nonetheless, having a precise and perfect orthographic transcript at a minimum is necessary (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Furthermore, the vital issue is to ensure that the requisite information is preserved. The transcribed data are typed and read several times to guarantee accuracy and to enable the researcher to become familiarised with the content’s depth and breadth (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

This study aims to identify the care style of Chinese female artists in their fibre art, providing a multi-perspective approach to studying female artists and deepening the understanding of women’s emotions, as well as offering more research support for the development of Chinese female artists in the field of fibre art. Research on women’s fibre artworks in the field of fibre art is an important topic in contemporary art. The objective of this study is to explore the conceptual expression of Chinese female artists’ fibre artworks from the perspective of feminist care ethics. By examining the meanings behind their works, this study seeks to reveal the care practices of Chinese female artists and the theoretical validity of interpreting fibre artworks.

This study is divided into six parts. The first part discusses the main content, research questions, research methods and significance of the study. The second part provides a literature review, focusing primarily on the origins and development of feminist care ethics. The third part explains the methodology, including how to conduct semi-structured interviews and analyse the data collected. The fourth part involves coding and summarising themes from the interview content using NVivo software. The fifth part analyses the coding results in the context of feminist care ethics. The final part presents the findings of this study.

Literature review

Feminist art history, fibre art and feminist care ethics intersect in several profound ways. Historically, fibre art has been marginalised as mere craft due to its associations with domesticity and femininity. However, feminist art historians have challenged these distinctions, recognising fibre art as a medium rich with personal and political narratives. From the perspective of feminist care ethics, fibre art gains additional significance. The ethics of care is a moral framework that emphasises interpersonal relationships, empathy, compassion and responsiveness to the needs of others as central to ethical decision-making (Foster and Ojanen, 2025).

Feminist care ethics is a new ethical theory that arose in the West in the 1970s. It not only affirms the unique moral experience of women but also emphasises a kind of moral care between people (Chen, 2013). Originally proposed by feminists, the theory of care ethics is the result of the development of the second feminist thought. According to Xiao (1999), unlike the first wave of feminism, which emphasised the equal right of both sexes to peace in all spheres of society, politics and economy, the second wave of feminism began to pay attention to the differences between men and women, reflect on the uniqueness of women and their own values, criticise sexism in all fields of ideology and construct feminist theory.

Regarding the study of care ethics, foreign research appears more systematic and comprehensive. Currently, most literature on care ethics is concentrated in Western countries. In the field of academic research and journals, notable works include Carol Gilligan’s ‘In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development’ (1982), Nel Noddings’ ‘Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education’ (1984), ‘Women and Evil’ (1989), ‘Starting at Home: Caring and Social Policy’ (2002), ‘Maternal Factors: Two Paths to Morality’ (2010), Virginia Held’s ‘The Ethics of Care’ and ‘The Routledge Companion to Feminist Philosophy’ by Millana Frick and Jennifer Hornsby, among others. The development of care ethics is for better responding to moral issues. According to Foster and Ojanen (2025), different from consequentialism and deontology, care ethics pays attention to the background and relationships where moral decisions are made, rather than the logic and rationality in moral judgments.

As the first female scholar to propose the concept of the ‘ethics of care’, Carol Gilligan’s theory was later widely accepted by most female researchers. Gilligan (1982) stresses that practical ethics should be grounded in understanding these dynamics and addressing everyday life’s realities rather than relying solely on abstract moral principles or idealised ethical scenarios. Noddings delved deeper into her research topic and expanded the application of the ethics of care from a practical perspective, also exploring its practical value. On this basis, Noddings extended the ethics of care to the social and cultural levels, arguing for its legitimacy through a series of analyses and discussions. Subsequent female scholars have explored the ethics of care from multiple angles, but in this paper, their research mainly references the care theories of Gilligan, Noddings, Tronto and Ruddick.

Following Gilligan (1982), Tronto (1993), Held (2006) and others, a ‘feminist’ ethic-of-care speaks to the value of relational and personal interactions that are traditionally associated with women’s work (Powell, 2020). In this study, women’s work takes the creation of fibre art as an example to seek the embodiment of female value displayed in art. Feminist researchers have seen care as ‘a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible’ (Fisher and Tronto, 1990, p. 40). Regarding this theory, Chen (2013) further explains that feminist care ethics reinterprets traditional ethics, extends its boundaries to the field of female theoretical research. It aims to supplement traditional just and legitimate ethics with care and responsibility, adopting a non-binary worldview. In a world where rationality and emotion, self and others, nature and culture are not divided, new ethical explorations replace traditional ethics. For this statement, Mu (2017) also indicates that women’s caring ethics reflect the inevitable trend in the era and historical development. It re-examines traditional ethical theories from a female perspective, calls for women’s awakening, reshapes their moral image and recovers their due value and status.

In the history of feminist art, fibre has long been seen as an important medium for challenging patriarchal artistic norms because of its deep association with women’s crafts. The 1970s saw the second wave of the feminist art movement. Artists consciously reassessed the cultural value of traditional women’s techniques such as embroidery, sewing and quilting. They transformed them into a politically charged artistic language (Parker, 1984). The representative of this period, Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago, among others, have contributed to the aesthetic transformation of fibre art through the re-creation of decorative arts and domestic crafts. Through the re-creation of decorative arts and domestic crafts, the aesthetic transformation of fibre art and the intervention of identity politics have been promoted (Nochlin, 1971; Reckitt, 2001). <The Dinner Party>, for example, uses embroidery and ceramics to construct a critique and restoration of women’s historical oblivion in a combination of materials and symbols based on the theme of women’s historical figures (Chicago, 1996).

At the same time, in the Chinese context, fibre has become an important site for women’s artistic practice. Liao (1995) proposes the theory of Beijing Weaving, which stresses that women artists create unique and internalised sensual spaces from their physical experience using labour-intensive mediums, such as weaving and sewing. This way of creation not only reflects a reflection on industrialisation and patriarchal logic, but also expands the perceptual boundaries of the material itself, making fibre an important medium for carrying emotions, memories and gender consciousness.

In this context, Tianmiao Lin’s artistic practice is particularly representative. In her artworks <Bound> and <Individual Space>, she makes extensive use of materials such as silk thread, cotton thread and hair to perform repetitive twisting and sewing actions, as a metaphor for women’s constraints and repression in the social structure (Yang, 2021). This intensive manual labour not only reveals a deep involvement in bodily experience, but also embodies a visual response to women’s ‘emotional labour’ in the ethic of care. Through the layering of fibre materials, Lin’s art becomes a narrative medium of emotional and historical indentations (Gao, 2011).

Additionally, research shows that most of the research conducted on creativity and productivity in adult life has concentrated on men (Diamond, 1986; Lindauer, 1992; McLeish, 1976; Schneidman, 1989; Sears, 1977; Simonton, 1989). Other research shows ‘studies have tended to focus on men because most creative achievements have been from men’ (Nicol and Long, 1996, p. 2). A few researchers have questioned why so few eminent female creators exist (Ochse, 1991; Piirto, 1991). Regarding the interpretation of this issue, Steele and Ambady (2006) argue that female stereotypes define the situation women find themselves in: most people position women’s professions in the humanities rather than in engineering and technology fields. And some even restrict women to the family, considering it their ultimate destination rather than work and career (Wu et al. 2017). The idea that women are responsible for care and men for provision exists in any cultural context (Hoyt and Murphy, 2016). Empirical studies have confirmed that gender stereotypes can lead to poor performance by women in important negotiations, decision-making or creative work, causing a lack of self-confidence, self-denial and even a tendency to quit (Bell et al., 2003; Logel et al., 2009; Schmader, 2002). Once women also develop stereotypical and self-negating psychological states, they tend to increase tentative behaviour and language at work (McGlone and Pfiester, 2015), which ultimately leads to poor results.

An ethical orientation based on care is linked to the human capacity for empathy (Slote, 2007). Although empathy involves cognitive dimensions, embodied empathy plays a particularly crucial role in understanding others, avoiding harm and awakening to helping others (Aaltola, 2018). Therefore, to solidify women’s standing in fibre arts, it is essential to develop a distinctive artistic discourse and set of values that diverge from the traditional male perspective. Analysis of existing research reveals a significant gap in studies focused on women’s artistic care and creativity, particularly within the domain of fibre art. Amplifying the voices of female artists in this field is a key goal of this research.

Theoretical framework

For research, a theoretical framework serves as a foundational ‘blueprint’ or guide (Grant and Osanloo, 2015). It defines the relevant objectives for the research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions. In this research, the theoretical framework is based on feminist ethics of care, which provides important support for the forthcoming data collection and interview analysis.

In this study, Chinese female artists are the subject of care, and feminist care ethics guide the content of the subject of care and how to care. Xiao (1999) argues that the ethics of caring tries to identify with the self through connection, care and relationships. Ethics of care is about weaving a horizontal, flat web of relationships in which the self is at the centre of the network and diffuses around, and the larger the network, the more valuable the ego is. The ontological explanation of this theory is that there are two main sources of female observation: female self-awareness, that is, awareness of herself and herself, and an autonomous awareness of the world, which includes society and nature.

Besides, artists present fibre artwork in specific situations to build and sustain caring relationships. Care, as a virtue, is established and derived from human emotions (Li, 2006). Xu (2013) emphasises that caring is a kind of emphasis on relationships, and through communication and dialogue, it helps to realise the harmony between people, nature and society. Mu (2016) argues that the situational principle of care ethics involves enacting caring behaviour according to the needs of actual situations. This explains how Chinese female artists make subjective connections between experiences and emotions. Care ethics regards morality as a caring action and emphasises the practice of morality.

As the world changes, so do caring relationships, which increasingly include ‘distant strangers’ (Lawson, 2007) and future generations (Adam and Groves, 2011). In the entire human community, the importance of care and concern is undeniable. As independent individuals, we always need to care for and be cared for in our lives. From the perspective of human history, if people lack mutual care and concern, the survival and continuous development of humanity will be threatened. Therefore, caring for oneself, others and the entire world constitutes the core goal of moral life and theoretical research. Care and concern form the central theme of human daily life. The core of care ethics is virtue, which is explored from the perspectives of relationships and actions, as shown in the diagram below:

Figure 1, show the trend of the theory, from the generation of the thinking of the caring subject, the establishment of appropriate caring relationships and the behaviour of caring virtue. In the behaviour, two aspects are mainly expounded: on the one hand, the care for women themselves, and on the other hand, the caring memory generated after feeling something, which is the theme analysis after guidance. Specific identification and coding are based on virtuous behaviour.

According to Xu (2013), care and empathy are theoretically consistent. Empathy first appeared in the field of aesthetics, where the observer projects their feelings onto the observed object, enabling the object to also have human feelings and resonate, as Liang (2021) notes. Ideational empathy is the most important ethical concept, according to Qi (2012), since it directly corresponds to the form of empathy that can motivate action and result in altruistic behaviour. The emotionalism line of feminist care ethics holds that morality, such as care, comes from experiences and emotions generated in daily life, and empathy is also concerned with emotions (Xu, 2013). Chinese female artists empathise with fibre artworks, and thus establish the relationship network between self and others, forming a caring relationship.

Methodology

Semi-structured interviews as research methods

Creswell (2011) states that we conduct qualitative research because a problem or issue needs to be explored. This exploration is necessary. For exploring the issues, rather than using predetermined information in the literature or relying on the results of other studies, (Creswell, 2011). According to Butina (2015), researchers doing qualitative research are interested in collecting and understanding the way in which people interpret their individual experiences, construct ideas and beliefs, and what meanings they attach, attribute, or construe to their experiences of a particular phenomenon. Qualitative research can be further explicated as the research approach that relies on the experiential knowledge and perspectives of individuals (Creswell et al. 2011). The details of qualitative research can only be established by directly talking to people, going to their homes or workplaces, and letting them tell stories without being hindered by what we expect to find or what we read in literary works (Chen, 2000). One of the main purposes of this study is to delve into and capture the concepts of fibre artworks by Chinese female artists. According to Evans and Lewis (2018), feedback and opinions are expressed information that broadens, refines, confirms, or, in certain cases, changes the perspectives that are held by the public.

According to the research needs, this study adopts structured interviews. For a qualitative research project, semi-structured interviews are often the only source of data, and questions about the interview schedule and location are usually arranged within a specified time (DiCicco‐Bloom and Crabtree, 2006). Gill et al. (2008) have also argued that the purpose of the research interview is to explore the views, experiences, beliefs and/or motivations of individuals on specific matters. Qualitative methods, such as interviews, are believed to provide a ‘deeper’ understanding of social phenomena than would be obtained from purely quantitative methods, such as questionnaires (Silverman, 2013). Interviews are, therefore, most appropriate where little is already known about the study phenomenon or where detailed insights are required from individual participants. They are also particularly appropriate for exploring sensitive topics, where participants may not want to talk about such issues in a group environment.

The research examples of Chinese female artists’ fibre artworks collected through these structured interviews mainly include why Chinese female artists choose fibre materials and why they use fibre materials to express their themes. The researcher was prepared with subsequent questions and prompts to encourage the respondents to talk more. Using the semi-structured interview method, the research questions raised are exploratory. This technique has the following advantages: (A) New ideas and topics may emerge during the data collection process, which contributes to the perception of the research and improves the interview agenda. (B) This method ensures that the data is highly valid because the interviewer can guarantee that participants understood the questions correctly through phrasing and worked to elicit more in-depth information (Jordan et al., 2004). Fundamentally speaking, qualitative interviews are a kind of social interaction, and information, understanding, and education are the roots of participation in qualitative interviews. There are several reasons to guide the application of this technique. As mentioned earlier, the interviewer should first have a generalist schema that focuses on the key issues, has some control over the debate and inspires the interviewer to discuss the hidden issues in detail.

Qualitative methods often rely on interviews with relatively few individuals with special characteristics (Patton, 2002). These characteristics depend on researchers’ pre-defined selection criteria, which may span traditional categories such as gender, age, nationality, or sexual orientation, or more specific attributes and experiences pertinent to individuals’ personal or professional lives (Morse and Niehaus, 2009). Generally, selection criteria are made according to what researchers believe will best accommodate their study. Therefore, the selected interview subjects are assumed to be those who are most suited to shed light on the research questions. According to Kristensen and Ravn (2015), the ways in which we as researchers recruit our informants influence who we end up interviewing and, hence, the knowledge we can produce.

This study chooses a purposeful sampling method. This is used to identify and select information-rich cases to make the most effective use of limited resources (Patton, 2002). This includes identifying and selecting individuals or groups of individuals who are particularly knowledgeable or experienced in the phenomena of interest (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2011). In addition to knowledge and experience, Spradley (1979) and Bernard (2002) point to the importance of availability and willingness to participate, and the ability to communicate experiences and perspectives in a clear, expressive and reflective manner. The study included 20 Chinese female artists specialising in fibre art. These artists must have expertise in fibre art and related fields. Qualified candidates may include full-time fibre artists and people who do that work part-time while doing other work, possibly in academia. Contact participants with potential through the personal email they provide on their website or social media platforms.

In this study, Chinese female artists were selected as study participants. Artists are in good physical and mental health. Because of the sensitive backgrounds of study participants, researchers will be very careful about the wording of interview questions. The researchers will note that the inquiry will relieve the respondent’s nervousness with gentle language. Interview questions are asked in a non-indicative and direct manner, which avoids any unpleasantness during the interview. This data is not disclosed to management for evaluation and decision-making due to any work-related performance. Participants’ vulnerability was not compromised during any of the study phases. Considering the backgrounds of the participants, the author is more careful in the wording of the research questions, which will involve the choice of materials in the fibre artworks and the exploration of the conceptual expression of the works. Table 1 below summarises the demographic details of the respondents of the individual interviews.

The artworks covered in this research have been explicitly authorised by the artists concerned and included in this research with their consent. The interviewed artists confirmed and agreed to the presentation of their names, creative concepts and related artworks to ensure the accuracy of the content and respect for their creative rights. During the research, the researcher strictly followed academic ethics, respected the intellectual property rights of the artists, and ensured that all artworks were cited and presented in accordance with their wishes.

Thematic analysis

In alignment with the qualitative essence of this study, a thematic analysis methodological approach was employed. The researcher intends to utilise NVivo, software designed specifically for qualitative data analysis. This software facilitates the organisation, coding and theme development processes inherent to thematic analysis, thereby allowing for a more nuanced and in-depth examination of the data.

According to the nature of this qualitative study, the thematic analysis method has been adopted, and the researcher will use NVivo data analysis software for data analysis. This technique is defined as ‘a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data’ (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 80). The goal of thematic analysis is to identify themes within qualitative data that can be used to interpret and understand the data (Maguire and Delahunt, 2017). This approach allows the researcher to examine the underlying motivations, ideas and assumptions within the spoken content. Another reason for adopting this approach is that, according to Chen (2000), it allows the management of qualitative data analysis through interviews, field notes, policy documents, photographs, footage, etc. Chen (2022) argues that the flexibility of the parameters in this method helps researchers conduct in-depth data collection, as well as explore, identify and report new concepts and ideas.

According to Braun and Clarke (2006), thematic analysis grants a reachable and theoretically versatile approach to analyse qualitative data. Through this technique, interview transcriptions were studied by the researcher to obtain the essence and extract the content. The data from across the entire dataset is then systematically coded for its salient features. Additionally, all interview transcripts were checked several times to ensure that each topic was considered. According to Braun and Clarke (2006), researchers must read the entire dataset at least once before coding because ideas and patterns can be generated through active and in-depth reading.

Primary codes were developed at this stage by generating relevant ideas from previous interview data. According to Boyatzis (1998), a code refers to ‘the most fundamental part or element of the original data or information that can be evaluated in a meaningful way for that phenomenon’. (p. 63). Some of the codes come from the theoretical framework of the study, while some come from the data (Boyatzis, 1998). At this stage, all probable themes and patterns are coded because the researcher cannot guess which part of the data would be interesting and which ones would be employed in the following steps (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

After all data have been coded and compiled, the subsequent step is to classify the codes into potential themes and include the entire excerpt of linked coded data within the identified themes. These topics are initially classified according to original and subtopics. The original themes should be rethought, and those with repeated meanings should be merged to form sub-themes related to the main theme. In this step, if the author comes across several pieces of code that cannot be judged or placed, a new category needs to be created to make it easier to repeat the observation when reviewing the code later. Significantly, the emergent themes must have a clear distinction from one another, and data within the themes must have meaningful coherence (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

The researcher cross-checked the dataset several times to ensure that the identified topics are relevant to the entire dataset and encode new data in the topics that may have been overlooked in the previous coding phase. Given that there is no specific process or rule for when to stop coding (Braun and Clarke, 2006), the procedure stopped when the researcher observed that the purification was no longer adding anything important. Another important step in topic research is to define and name each detail that has been refined (Whittaker, 2012). To identify the proper names of the subjects, these names are to reveal the essence of the research and must be combined with the theory in the research, which is the feminist ethics of care. The final step is to create an analysis report, which aims to present the data effectively to better present the results and findings.

Results

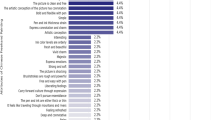

This part is coded and classified according to the interview content of female artists, and finally forms the corresponding theme (Fig. 2). Each topic will be analysed in depth in the following chapters.

Thematic analysis results 1

The first research content is to analyse the reasons that lead female artists to use fibre materials to express their ideas. This step is aimed at their creative motivation. Two obvious reasons are summarised in this part (Fig. 3): one is the femininity contained in fibre materials, and the other is the emotional metaphor brought by fibre materials. These two contents will be further explained in the following studies.

-

Femininity

Femininity has a profound relationship with the creation of fibre art (Fig. 4). The flexibility of fibre materials, the diversity of craft forms such as weaving, and their complex structures and pattern designs provide artists with a rich medium of expression (Corso-Esquivel, 2019; Zhao, 2021). The structural and repetitive manipulation of weaving not only demonstrates the malleability of the material but also symbolically reflects the complex roles and multi-layered identities that women play in social networks (Chen, 2022). The repetition and variation of motifs further reflect the dynamic nature of female subjectivity, challenging traditional fixed and homogenised understandings of gender identity (Corso-Esquivel, 2019).

-

a.

Technique

The flexibility and malleability of the fibre material map the woman’s ability to maintain continuity and diversity in her multiple roles. The woven structure symbolises a resilient network of care and collaboration through the interplay of veins and nodes. The delicate texture and tactile temperature of the fibres emphasise the physicality of the body and encourage the viewer’s empathetic experience. The fibre material transcends its role as a medium and becomes an important symbol that carries the narrative of women’s subjectivity and the remaking of memory.

‘The relationship between fibre media and women, I think, is more reflected as resonance, which is no longer passive, but the relationship of women’s active choice’. (F4).

Female artists experiment with non-traditional materials such as plastics, metals, and recyclables, pushing the boundaries of knitting.

‘Interest in knitting and embroidery’. (F12).

And, often, they combine traditional weaving techniques with other textile techniques, such as embroidery, knitting and felt, to create hybrid pieces that challenge traditional categories and generate new interpretations. Moreover, it can also be found in the artworks of the artists interviewed in this interview that, for weaving techniques, artists are more willing to create interactive weaving installations, where viewers can participate in the weaving process, cultivate a deeper connection with the art, and appreciate the skills involved.

In the current era, weaving methods in fibre art vary due to the diversity of techniques and various applications such as weaving, winding and stacking. The experiences brought by different materials also differ. As an art form that closely combines emotion and technique, the uniqueness of fibre in the art field primarily stems from the simplicity and authenticity of fibre material technology. Fibre artworks, with their various visual effects in texture, hollowing, depth, distance, contrast and more, exhibit forms and craftsmanship that endow them with unique aesthetic value and rich connotations, prompting deep sensory reflection on the artworks.

-

b.

Pattern

The weaving structure of the fabric is formed by the interlacing of warp and weft yarns, which provides the material basis for the pattern. Differences in colour, yarn thickness and weave density, through changes in nodes and tension, lead to repetitions and variations in the pattern. Artists can deconstruct and reorganise the pattern locally by adjusting the local weave density or changing the winding method, so that the whole can be coherent and at the same time show dynamic tension.

‘…when it comes to women, the characteristics of softness, affinity, flexibility and so on that everyone instinctively thinks of are easily associated with some fibre materials’. (F8).

‘As a woman, I am genuinely fascinated by the variety of textures that the embroidery machine can produce’. (F18).

Through the organisational structures of weaving, embroidery and other techniques by female artists, fibre lines outline the beauty of flexible power. In each piece of fibre art created by female artists, although the weaving structure cannot fully demonstrate the appeal of flexible mechanics, it becomes a crucial pillar for expressing their personal spirit during the creative process.

‘Today’s creation is not only about the continuation of tradition, but also about how to create contemporary fibre patterns’. (F7).

In contemporary fibre art design, how to convey the deeper meaning through patterns and how to balance the relationships between various patterns are crucial issues in fibre art creation. In fibre artworks, patterns and designs constantly change within complex environments, with each fibre pattern forming the core elements of innovation. Only when the relationships between the main pattern and other patterns within the fibre pattern system are properly handled can the core meaning of the primary pattern be effectively conveyed.

-

Emotional metaphor

Emotion is the word most frequently mentioned by interviewees. This is not only because women themselves are symbols of sensibility and emotional experience plays a dominant role in women. Some female artists also point out that their emotional experience is not only a personal experience but extends fibre art works to social groups and connects individual points into a line. Eventually, covering a wide area. However, like other artists, their original intention is still to see fibre as an emotional bond to inspire a group effect. By sorting out the interview content, two key codes are generated, one is emotional connection and the other is emotional healing (Fig. 5).

-

a.

Emotional connection

Many female artists long for fibre art to become an emotional bridge. It is not just a bond between them and the audience, but also a source of warmth for their families and hearts. The deep affection many female artists have for fibre is largely shaped by their family environment; these artistic activities are often passed down from one generation of women to the next. From a traditional perspective, the craft of weaving can silently connect women closely with their surroundings and things. Whether it pertains to the artist themselves or their surroundings, this coherence merges female memories, emotions and identity. Some artists point out that their fibre art creations aim to showcase the deep emotions between women and their mothers, using this art form to display traditional family crafts related to mothers. For example, such content appears in the interview content:

‘This behaviour is no longer cheap manual work, which actually makes the subtle relationship between women and the fabric, across the traditional femininity, the natural form of women’. (F1).

‘Fibre art brings people not only the temperature of the hand, but also the temperature of the heart, which is what we lack in interpersonal communication now’. (F7).

‘I would use the words ‘love’ and ‘faith’’. (F16).

This study found that in artistic creation, the emotional connection is concrete. An artist would depict a piece of fibre art as an important female organ, the uterus. The fibre seems to have a close connection with the mother and herself, and the fabric shows the deep emotional connection between the mother and the child, providing the viewer with a rich emotional experience.

‘My creative inspiration comes from real life’. (F8).

‘Fibre art achieve my own spiritual experience and opinion expression’. (F12).

-

b.

Emotional healing

Fibre art mainly focuses on three core areas: memory, personal growth and self-awareness. Another reason for choosing fibre is that some respondents believe it provides psychological healing.

‘Fibre art brings people not only the temperature of the hand, but also the temperature of the heart, which is what we lack in interpersonal communication now’. (F7).

‘Choosing fibre language to create is not a choice, but a love with a sense of mission’. (F9).

‘For me, it’s healing’. (F11).

Due to the historical background of fibre materials and their unique properties, people have rich emotional impressions in the memory of fibre materials and textiles. Artists transform fibre from a simple utilitarian material into an object that carries emotions. In the process of creation, when the soft fibre materials meet the body, they are easily attracted by the warm and soft touch of the fabric, being healed by the warm fabric.

From a material perspective, it differs from other art forms. Fibre materials have unique properties that can heal the human spirit. Fibre art is closely linked to our lifestyle, constantly intertwined with our daily lives. In an interview, the researcher observed that most women face many potential pressures. This is not only due to the physical impact of family life on women but also, more significantly, due to psychological pressure. An artist used the term ‘emotional labour’, pointing out that,

‘Compared to the physical care of the elderly and children, the psychological pain is something female cannot recover from on their own’. (F10).

This pain is often something that most men cannot understand. Women’s dissatisfaction with life and society is often eroded by broader social criticism, affecting their feelings. Women tend to transform their perspectives into a different form of expression, conveying an intangible voice through fibre artworks. The warmth characteristic of fibre artworks not only inspires women but also brings healing, mending the wounds of their souls.

‘I think many parts of the women’s own healing effect’. (F1).

Artists cleverly use the temperature changes of fibre materials to evoke their psychological responses, leading them from visual to tactile sensations, ultimately guiding them to a deeper psychological understanding. This healing of the artists’ souls also reaches the audience’s hearts, allowing them to perceive the emotional warmth within the materials.

Thematic analysis results 2

The content of this section is mainly aimed at how female artists express ideas in fibre works from the perspective of female care ethics (Fig. 6).

-

Female concern

In the fibre practice of contemporary women artists, caring is no longer just a gentle response to the other, but also a deep listening and repair of the self. Many artists emphasise that true female caring begins with understanding and taking care of oneself. This self-care is a rediscovery of the long-neglected inner experience of women. The artists’ creations, opened up through fibre materials, are an act of repair from the inside out. They care for themselves first and foremost, which in turn radiates a more powerful and conscious practice of caring.

For this issue, artists believe that their first concern is themselves, and they generally believe that Women have a deeper understanding of themselves, as one of the interviewees said,

‘Women’s use of fibre is flowing in the blood’. (F2).

In women’s daily life, emotion often surpasses rationality and is often filled with joy, anger, sadness, sorrow, separation and other emotions. In the creation of female artists, their consciousness and ideas often occupy a priority position. Life provides women with rich emotional experiences, and women choose emotion as the entry point for artistic creation and expression. For example:

‘I think we can also take our time to speak up and express how we feel about this whole gender thing’. (F3).

‘Subjectively, the delicate, sensitive and sweet nature of women is more likely to produce artistic collision with the softness and kaleidoscopic nature of fibre media’. (F7).

When artists speak about this issue, many feel that traditional social views and family moral values impose excessive rules and expectations on women. Most artists believe that fibre art has a unique quality that can perceive maternal love. Women artists’ love of fibre is not only because their deep connection with textiles continues to this day, but also because their love of fibre is inspired by their mothers. This kind of maternal creativity endowed by nature has promoted the progress of human civilisation, and profoundly affected the way of thinking and perspective of artists.

The artist’s use of hair as an important medium for the expression of ideas not only reflects the deeper personal (Fig. 7), cultural and conceptual significance of the artwork, but also embodies a caring practice. As a highly intimate and physical material that carries multiple symbols of individual identity, memory and social relationships, the artist constructs a way of expression that is both personal and collective using hair.

This shift emphasises an evolving approach to materiality, as the artist incorporates hair, a material rich in life and bodily perception, into his creations to enhance the depth and emotional resonance of his subject matter. From the perspective of care theory, artmaking becomes a process that embodies ‘caring labour’: the artist handles and weaves these materials with delicacy, patience and emotional commitment, as if engaging in a process of caring for and repairing bodies, memories and identities (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017).

These specially selected materials not only enrich the form and texture of the artworks, but also convey a sense of privacy and vulnerability within the conceptual framework, reinforcing the female subject’s agency and emotional experience. The theory of feminine care, on the other hand, equally emphasises the value of emotional connection, relational ethics and bodily experience, (Held, 2014). Using hair as a medium, the artist embodies respect and care for women’s bodily experience, reflecting the complexity of women’s situation and resistance in cultural and social structures.

‘Hair serves as a connection, carrying the shared DNA between mother and daughter. Amplifying this hidden attribute highlights that the female role encompasses not only personal growth but also the warmth and bond between mother and child’. (F1).

‘In recent years, more and more attention has been paid to the theme of ‘women’’. (F8).

In the process of artistic creation, artists often take maternal love as the central theme, deeply explore the experience of women, the relationship between women and family, and emphasise the transmission of emotions. Some interviewees stated,

‘I obviously felt that I was growing up, and growing up requires a lot of responsibility and pressure’. (F15).

Textile art has a close connection with women and their fields of life, and the fibre artworks created by female artists bring warmth and care to women and those around them. It is no exaggeration to say that in the creation process of fibre art, the concern for women is undoubtedly the most profound expression of emotion. Through weaving techniques and women’s simple forms of expression, a gradually deepening emotional experience is presented.

-

Public concern

This study also found that, apart from expressing women’s own identities, artists are also directing their attention and thoughts towards relationships between people and between individuals and society. The close connection between textiles and social context is one of the continuously explored topics in contemporary fibre art, and the reflection of societal concepts through women’s emotions in fibre artworks brings limitless possibilities for artists.

‘Women are under too much pressure in society and need to have a voice’. (f18).

In China’s feudal history, women have always been a marginalised group, restricted by social gender expectations that limited their path. A person’s gender role is often defined by society from birth, shapes a girl’s worldview and values within the constraints of her surroundings, and is easily accepted by society as female. As one of the interviewees said,

‘… my cognition of the role of women beyond personal experience, projected to the social scope’. (F1).

‘I try to awaken people’s basic respect with my artworks’. (F15).

Among the female artists interviewed, their concern and expression of social issues are not uncommon. Each artist has a unique understanding and insight into society, and the values reflected in their work vary widely. Artists focus on their own experiences and gradually expand outward to the external society. Through the connection of points and lines, and the extension of lines and surfaces, they gradually build a space of common understanding. One artist said,

‘Some social problems cannot be described in words, and works are the best words’. (F20).

<Women Series: IUD> (Fig. 8) not only deeply reflects the artist’s critical thinking about the transformation of women’s bodies by modern medicine, but also reveals the important issues of power relations and bodily autonomy in the ethics of social care. Taking the IUD as an entry point, the artwork reveals how modern medicine exerts institutional and structural control over women’s bodies through a ‘scientific’ discourse system, which is not only limited to the physiological level, but also extends to the social norms and interventions on women’s roles and reproductive rights.

Fig. 8 From the perspective of social care, the artwork calls for multi-dimensional care for women’s bodies and health, emphasising that care is not only emotional support at the individual level, but also a social responsibility and political practice. The artwork reveals the latent power structure in the medical system, challenges the objectification and normalisation of women’s bodies in the medical discourse, and reminds us to pay attention to women’s physical labour and psychological burdens under this system.

Through this artwork, the artist calls on society to re-examine the rights and autonomy of women’s bodies, and to promote a more inclusive and ethical medical and social support system based on respect for individual experience and bodily integrity. This kind of social care centred on the female body expands the understanding beyond the traditional medical framework, highlighting the importance of empowerment, respect and ethical responsibility in modern society.

Figure 9 shows a virtualisation of the female body organ (uterus) by the artist through the use of thread and yarn materials, directly presenting it to the public in space, breaking the boundaries of bodily privacy. This form of expression is not only a visualisation of women’s bodily experience, but also a profound reflection on how society understands and cares for women’s bodies.

This artwork not only carries the space for the accumulation of the artist’s inner emotions, but also emphasises the importance of care as a social relationship and emotional practice. The interaction between the fabric and the sense of touch evokes the viewer’s intuitive feelings, and the tenderness and unique texture of the fabric not only brings physical comfort, but also touches the heart on an emotional level, embodying a warm and delicate way of caring.

This care through material media not only makes women’s bodily experiences acceptable and visible in public space, but also promotes social respect and support for women’s bodily rights and emotional needs (Valtonen and Närvänen, 2022). The artwork reveals that caring not only exists in the private emotional realm but is also a broader responsibility that involves social ethics, politics and culture, calling for the public to pay attention to and participate in the practice of caring for women’s bodily rights and health in society.

Society is increasingly concerned about the close connection between works of art and the experience of public life. Core work in this field tends to ask questions rather than trying to provide definitive answers to specific questions. Even those that relate to personal life experiences and experiences are real, profound and thought-provoking.

-

Natural concern

The core of environmental concern is the ecosystem, which not only refers to nature itself but more to the physical environment, including the plants, water sources, atmosphere, and land around us. Artists have a wide range of focus, organically integrating the natural ecology and biological communities within the ecosystem.

Nature is also an important focus in the search for life. According to the artists interviewed, their understanding of nature provides them with a wealth of creative inspiration. For example,

‘I’m particularly interested in the details of nature, and I like the feeling of being close to nature’. (F9).

‘My artworks have changed with the changes of my living environment’. (F17).

‘I want to use some natural materials with traditional techniques to record and feel the infinite possibilities in nature’. (F19).

<Solvable>, a large-scale installation made of wet felted wool, reproduces the toughness and strangeness of stalactites as a natural landscape through 403 hanging monolithic forms. Through careful observation and scientific documentation of cave stalactites, the artist has internalised their morphological characteristics into the material language of wool fibres, thus presenting a visual tension between hardness and organicity.

From the perspective of caring theory, the artist’s choice of wool as a natural material and the use of the wet felting process reflect the respect and reproduction of the natural material. The interaction between water and wool fibres during the wet felting process is a metaphor for the interdependence and cyclical flow of elements in nature, highlighting the intrinsic connectivity and symbiotic relationship of the ecosystem. Through the detailed portrayal of texture and form, the work triggers the viewer to reflect on the perception of the natural environment and awakens an ethical concern for ecological fragility and its protection.

Further, nature care not only emphasises the external practice of environmental protection, but also focuses on the establishment of an ethical bond and sense of responsibility between human beings and nature. Figure 10 advocates a reflective ecological ethics through its material aesthetic presentation, prompting viewers to re-examine the symbiotic relationship between humans and nature, and to respect the intrinsic value and autonomy of nature, thus promoting the extension of the caring paradigm in contemporary art and society.

Therefore, their works of art often reflect an insight into nature and embody the delicacy and tenderness of women. From the perspective of women’s care and care, they show deep concern for nature. The daily life of human beings is closely connected with nature, and each part of nature has its own unique meaning and value. This attention to nature is precisely a record of the artists’ lives, showing the harmonious relationship between man and nature.

‘I want to appeal and voice through a realistic work’. (F2).

Each artist has a different interpretation of life, and these concepts provide creative guidelines for female artists and profoundly shape their artistic style. Although the environment provides a haven for human beings, with the progress of The Times, the creation of female fibre artists increasingly reflects the concern and thinking about the environment and ecology. Some interviewees said,

‘It’s when it becomes apparent that people don’t seem to have much sense of the landscape around them anymore and pay little attention to their own inner self’. (F11).

The artist regards fibre as a ‘second skin’ and uses it to remind people to maintain the balance of natural ecosystems and reflect on the destruction of ecosystems by humans.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study is to analyse the specific views expressed by Chinese female artists in fibre artworks based on feminist care ethics. In view of the theoretical framework, the researcher designs another question to help understand the research purpose before this question, which is the reason why Chinese female artists choose fibre materials to express their ideas. The results show that, firstly, the reason why they choose fibre art to express their ideas lies in the embodiment of femininity and emotional metaphor of fibre materials; Secondly, through thematic analysis, the concept of Chinese female artists in fibre artworks mainly focuses on three aspects: female concern, social concern and natural concern.

‘The ethical system established by men in order to benefit themselves is not perfect, so they build their unique moral emotional experience from women’s unique mental, physical, and unique family social activities’. (Held, 2014). In her research, Liu (2012) emphasised that care ethics not only gives a mode of review of moral issues related to women, but also applies to all areas of society, far beyond the life experience specific to women.

As clearly described in the above research report, when women, as subjects, express their emotional concepts, they can interpret the caring practice activities of Chinese female artists through care ethics as a guiding method, so that the emotions in their fibre artworks can be subject to moral thinking and correctly evaluated. The researcher also makes the following table according to the rationality of the combination of the two:

As shown in Fig. 11, the researcher observes that feminist care ethics provides a highly relevant framework for interpreting the creation of female fibre art. There is a strong continuity between the two, as demonstrated in the thematic discussions of the previous chapter. Before beginning their creative process, female artists often engage in deep reflection, drawing from their personal experiences. This introspective process is inherently infused with the femininity described in ethical care theories.

Through this profound understanding, women tend to channel their unique emotions into specific artistic scenes. This gender-based emotional approach to thinking allows them to express care and concern for a particular person, issue, or broader societal theme embedded within their work. Female artists conduct in-depth analyses of specific challenges and articulate their empathy and awareness through fibre art, transforming their artistic practice into a means of engagement and advocacy.

By creating fibre art, these artists extend women’s perspectives and ways of thinking into diverse fields, including culture, politics and economics. Their artworks serve as a medium through which emotional depth and ethical considerations are woven into visual and tactile forms. Through this process, they hope to inspire meaningful discourse and instil a deeper sense of care within society. Ultimately, the fusion of feminist care ethics and fibre art not only highlights the personal narratives of women but also contributes to reshaping societal values and fostering a more compassionate and inclusive world.

Therefore, the researcher has constructed a model to illustrate how care can be transformed both formally and processual in the process of creating fibre art, and thus extended to a wider art field (Fig. 12). Firstly, in the private sphere, the tactile nature of the material and the rhythmic sense of hand-woven texture of fibre art reflect the sensitive response of female artists to their own experience and the situation of others. Care is presented in the form of interweaving of yarns and accumulation of texture. Secondly, through public display and audience participation in the context of the exhibition, the surge of personal emotions can be spread outwards: when the audience touches or looks at the fabrics embedded with fragments of stories, emotions are transferred in perception and imagination, prompting them to empathise with the needs and concerns of others. At the same time, the artist’s choice of materials is reflective: the alternation of fibre, colour and traditional painting mediums responds to emerging values of care and gives the work a different narrative tension. As this cycle progresses, the newly generated caring concepts are in turn reflected in the creative practice, guiding the artists to continue exploring the formal construction and material practice, so that the caring can dynamically evolve in fibre art and in the broader art discourse.

In the creative practice of female artists, fibre artworks not only highlight women’s sense of empathy with their silent care and shouts, but also reveal the moral power contained in the fibre material itself. Taking <Women’s Series: Intrauterine Devices> by Wenjing Zhou as an example, the artist weaves and reorganises the elements of intrauterine devices with the metallic texture of copper wire, the industrial texture of PVC, and the soft touch of silicone. Each installation has a physical reference to memory, but also a metaphor of care and vulnerability under the intervention of technology in the conflict of material tensions. Through tactile association and visual interpretation, the viewer is introduced to the private realm of women’s bodily experience, and in the public exhibition, the viewer enters a dialogue with the artworks, completing the emotional transfer from private predicament to public concern.

In the artistic creations of female artists, fibre artworks can be seen not only as a silent expression of care and outcry, but they also highlight the empathetic consciousness of women and demonstrate the moral power that women create through fibre. They view people and society from a perspective filled with care, concretising moral issues and creating under the drive of women’s emotions and social needs. This perfectly embodies the emotion-driven approach to behaviour advocated by feminist care ethics, aligning with the core moral principles promoted by the ethics of care. The moral model of feminist care ethics is specific; it focuses on individual emotions, universal experiences and strives to find solutions to moral dilemmas. Fibre art creation can be seen as the most intuitive way for female artists to address issues of care. They influence others through emotions rather than verbal criticism, and this behaviour of caring for others is beneficial for the development of relationships between people and society.

Conclusion

Feminist care ethics focuses on caring and emphasises the moral core of relationship, situation and emotion. Care ethics is a caring principle applicable to all levels. When people are driven by a caring tendency, they care sincerely, perceive the needs of others with mature moral understanding ability, evaluate and practice caring with the caring principle, and then get responses.

This study reveals that Chinese female artists have consciously constructed a cycle system with ‘care’ as the core in their fibre art creations: individual experiences are delicately presented through the medium of fibre, and through the spatial expression of the artworks, they open a dialogue with the social group, which then feeds back to the main body of the creations, forming a dynamic care system that extends from the individual to the group, and then back to the individual again. This practice not only verifies the principles of relationship and reciprocity emphasised by the ethics of care, but also highlights the unique potential of fibre materials in the connection between art and society.

Based on this research, it can provide a basis for further interdisciplinary exploration: future research can combine material science to explore the impact of new fibres and sustainable processes on caring narratives; incorporate digital humanities and interactive design to broaden the perceptual experience and social participation of fibre art. Through the integration of these multiple perspectives, the study of fibre art and the ethics of care will be further deepened, injecting new vitality and imagination into contemporary art and social practice.

However, the data collected in this study are limited. To bring care ethics into the art field from a broader perspective, more artists need to participate. This is a long-term research work and substantial data material analysis, which can build a caring model with women as the main body. This model can guide future researchers to have a clearer understanding of artists’ caring motives and behaviours during creation.

At present, society needs such caring behaviour to warm the human heart. Women convey love and a sense of belonging with more delicate emotions, making people aware of neglected moral issues. However, the author should emphasise that caring behaviour does not exist only among women but provides more possibilities for human beings to think about ethics and morals and brings moral emotions into a wider world.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Materials availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

Adam B, Groves C (2011) Futures tended: care and future-oriented responsibility. Bull Sci Technol Soc 31(1):17–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467610391237

Aaltola E (2018) Varieties of empathy: Moral psychology and animal ethics. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD

Bell AE, Spencer SJ, Iserman E, Logel CER (2003) Stereotype threat and women's performance in engineering. J Eng Educ 92(4):307–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2003.tb00774.x

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Bernard HR (2002) Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). AltaMira Press, Walnut Creek, CA

Boyatzis RE (1998) Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. SAGE, London

Butina M (2015) A narrative approach to qualitative inquiry. Clin Lab Sci 28(3):190–196

Brinkman M (2024) Feminist themes and styles: feminist fibre art. Feminist Art, September 2. https://www.feministart.ca/learn-more/feminist-fiber-art

Creswell JW (2011) Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed.). Pearson, Boston

Chen X (2000) Qualitative research methods and social science research. Education Science Press, Beijing

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2011) Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Chicago J (1996) The dinner party: From creation to preservation. Merrell Publishers, London, UK

Chen L (2022) Threading Identity: contemporary Chinese women artists and textile labor. J Contemp Art Stud 14(2):34–49

Chodorow N (1995) The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the sociology of gender (2nd ed., p. 167). University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

Chen L (2013) Research on ideological and political education for women (Doctoral dissertation, China University of Mining and Technology, Beijing). CNKI. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=

Corso-Esquivel J (2019) Feminist subjectivities in fiber art and craft: Shadows of affect. Routledge, New York, NY

Diamond AM (1986) The life-cycle research productivity of mathematicians and scientists. J Gerontol 41:520–525

DiCicco‐Bloom B, Crabtree BF (2006) The qualitative research interview. Med Educ 40(4):314–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x

Evans C, Lewis J (2018) Analyzing semi-structured interviews using thematic analysis: Exploring voluntary civic participation among adults (pp. 1–6). SAGE Publications Limited, London, UK

Foster R, Ojanen W (2025) Ecosocial care ethics in and through dance education. J Dance Educ 25(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2024.2423230

Fisher B, Tronto J (1990) Toward a feminist theory of caring. In Abel EK, Nelson MK (Eds.), Circles of care: Work and identity in women’s lives (pp. 36–54). State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

Gilligan C (1982) In a different voice. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B (2008) Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204(6):291–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.192

Gao M (2011) Total modernity and the avant-garde in twentieth-century Chinese art. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Grant C, Osanloo A (2015) Understanding, selecting, and integrating a theoretical framework in dissertation research: developing a ‘blueprint’ for your “house”. Adm Issues J Educ Pract Res 4(2). https://doi.org/10.5929/2014.4.2.9

Held V (2006) The ethics of care: personal, political, and global. Oxford University Press

Held V (2014) The ethics of care (L. Li, Trans.). The Commercial Press, Beijing, China. (Original work published 2006)

Hoyt CL, Murphy SE (2016) Managing to clear the air: stereotype threat, women, and leadership. Leadersh Q, 27 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.11.002

Haraway D (2008) When species meet. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN

Haraway D (2016) Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, Durham, NC

Johnson B, Christensen L (2012) Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Jordan F, Gibson H, Goodson L, Phillimore J (2004) Let your data do the talking: Researching the solo travel experiences of British and American women. In Phillimore J, Goodson L (Eds.), Qualitative research in tourism: Ontologies, epistemologies, and methodologies (pp. 215–235). Routledge, London

Kristensen GK, Ravn MN (2015) The voices heard and the voices silenced: recruitment processes in qualitative interview studies. Qual Res 15(6):722–737. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794114567496

Liu H (2012) Female growth and caring ethics: On Gilligan’s theory of female psychology. J Northwest Norm Univ Soc Sci Ed 2012(3):25–30. https://doi.org/10.16783/j.cnki.nwnus.2012.03.006

Liang K (2021) Caring narrative of fibre art. China Architecture & Building Press, Beijing, China

Liao W (1995) Beijing weaving: a Chinese practice of feminist art. Chin Contemp Art Rev 2:23–30

Lindauer MS (1992) Creativity in aging artists: contributions from the humanities to the psychology of old age. Creat Res J 5:211–231

Logel C, Walton GM, Spencer SJ, Iserman EC, von Hippel W, Bell AE (2009) Interacting with sexist men triggers social identity threat among female engineers. J Pers Soc Psychol 96(6):1089

Li L (2006) A study of care ethics (Master’s thesis, Huazhong University of Science and Technology). CNKI. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=RyE_S26iMhU

Lawson V (2007) Geographies of care and responsibility. Ann Assoc Am Geographer 97(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00520.x

Liu J (2019) Textile women, mothers, goddesses (Doctoral dissertation, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China). https://doi.org/10.27626/d.cnki.gzmsc.2019.000361

Liu XH (2012) The rediscovery of gender discrimination in social sciences. Shehui Kexue Yanjiu (Social Science Research), 4:45–52

McLeish JAB (1976) The Ulyssean adult: creativity in the middle and later years. McGraw-Hill/Ryerson, New York

Maguire M, Delahunt B (2017) Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISHE-J: The All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.62707/aishej.v9i3.335

McGlone MS, Pfiester RA (2015) Stereotype threat and the evaluative context of communication. J Lang Soc Psychol 34(2):111–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X14562609

Morse JM, Niehaus L (2009) Mixed method design: Principles and procedures. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA

Mu S (2016) An analysis of the second-child policy from the perspective of feminist ethics of care. Yinshan Acad J 29(2):88–92. https://doi.org/10.13388/j.cnki.ysaj.2016.02.017

Mu S (2017) The dilemma and development path of feminist care ethics (Master’s thesis, Sichuan Normal University). CNKI. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=RyE_S26iMhWS

Nicol JJ, Long BC (1996) Creativity and perceived stress of female music therapists and hobbyists. Creat Res J 9(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj0901_1

Nochlin L (1971) Why have there been no great women artists? Art News, 69(9):22–39, 67–71

Ochse R (1991) Why there were relatively few eminent women creators. J Creat Behav 25(4):334–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.1991.tb01146.x

Piirto J (1991) Why are there so few? Creative women: Visual artists, mathematicians, musicians. Roeper Review, 13(3):142–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783199109553340

Patton MQ (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Parker R (1984) The subversive stitch: Embroidery and the making of the feminine. Routledge, London, UK

Powell G (2020) Gender and leadership. Sage Swifts, London, UK

Puig de la Bellacasa M (2017) Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more-than-human worlds. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN

Qi G (2012) Ethics of empathic concern: a new approach to Schloter’s emotionalism virtue ethics. Search (2):114–116. https://doi.org/10.16059/j.cnki.cn43-1008/c.2012.02.039

Reckitt H (Ed.) (2001) Art and feminism. Phaidon Press, London, UK

Schneidman E (1989) The Indian summer of life: a preliminary study of septuagenarians. Am Psychol 44:684–694

Sears R (1977) Sources of satisfactions of Terman’s gifted men. Am Psychol 32:719–728

Silverman D (2013) Doing qualitative research (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd, London, UK

Simonton DK (1989) The swan-song phenomenon: last-work effects for 172 classical composers. Psychol Aging 4:42–47

Spradley JP (1979) The ethnographic interview. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York

Schmader T (2002) Gender identification moderates stereotype threat effects on women’s math performance. J Exp Soc Psychol 38(2):194–201

Slote M (2007) The ethics of care and empathy. Routledge, New York, NY

Steele JR, Ambady N (2006) “Math is hard!” The effect of gender priming on women’s attitudes. J Exp Soc Psychol 42(4):428–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.06.003

Tronto JC (1993) Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge, New York

Valtonen A, Närvänen E (2022) Materializing the body: A feminist perspective. In Maclaran P, Stevens L, Kravets O (Eds.), The Routledge companion to marketing and feminism (1st ed., pp. 159–170). Routledge, London, UK. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003042587

Whittaker A (2012) Research skills for social work. SAGE Publications, London, UK

Wang X (2011) Colour study of fibre art deco materials (Master’s thesis, Xi’an Polytechnic University). [CNKI]. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=IKKGlZ0AkeW85YTbhiej9IlZO-Rtk4JDiX9s2YSIkz4ttwZSnSqnB7PFUu0KiC2aip2hQ3U-DsIgG7GHAAD8u2ybAcmK4qLVSH6tVsiRy5rqEESs3x0CBS62VjMQg02B3tFUww2U3VSxWCcaowbx3XXY0CIbRn6Sb4O0J0mzeuKmLpgTMZioLQ==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS