Abstract

This study examines the reintegration challenges faced by Malawian students who returned home without completing their higher education degrees abroad. Adopting a mixed-methods design, the study integrates quantitative data from structured surveys (n = 143) and qualitative insights from in-depth interviews (n = 30). The quantitative analysis employed descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, t-tests, multiple regression, and structural equation modelling (SEM) to explore the relationships among key variables, including social support, financial stability, and psychological well-being. Results indicate that returnees face significant social isolation (72%) and community judgement (63%), which, according to SEM, negatively impacts psychological well-being directly and indirectly through weakened social support. Economically, 69% reported underemployment or unemployment, with financial stability emerging as a critical predictor of successful reintegration. High levels of psychological distress were evident, with 65% experiencing depression and 71% reporting anxiety, compounded by limited mental health support. Qualitative interviews further revealed themes of identity confusion, stigma, and the need for tailored support services. These findings underscore the necessity for holistic reintegration programmes encompassing social, economic, psychological, and cultural support. Policy recommendations include community education to reduce stigma, targeted mental health resources, and economic empowerment initiatives to enhance the social and financial resilience of returnees. This study contributes to the broader discourse on international education, highlighting the complexities of reintegration for students returning without a degree.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malawi, a low-income country in southeastern Africa, has gradually recognised the significance of higher education for national development. The federal government has demonstrated a commitment to education sector development through policies aimed at increasing enrolment in higher education. Despite these efforts, domestic higher education institutions face significant challenges, including inadequate infrastructural facilities, severe resource limitations, and a high student–teacher ratio, which impedes their ability to accommodate the growing demand for tertiary education in Malawi (Bank and Malawi 2021; Mambo et al. 2016). Subsequently, the government and private investors initiate opportunities for Malawian students to pursue higher education at reputable universities in various countries.

Malawi’s sociocultural context is marked by collectivist norms, where community judgement is pivotal in shaping individual experiences. Social status is often tied to educational and economic achievements, with strong communal expectations to uphold family honour and reputation. Failure to meet these expectations—such as returning without a degree—can lead to public stigma, isolation, or perceived “shame” for the family (Mambo et al. 2016). Although Malawi is a collectivist society, its communal expectations around educational success may heighten reintegration stigma more acutely than in other collectivist cultures that place a broader emphasis on group harmony over individual performance. This particular cultural script intensifies personal shame and social alienation upon academic failure abroad. However, social support systems also draw from traditional community networks, including extended family structures and local leadership, which can offer practical and emotional assistance during crises. This tension between collective judgement and communal solidarity influences the challenges of returnees’ reintegration.

Numerous factors have motivated Malawian students to seek education in various countries and regions globally. Flanagan-Bórquez and Soriano-Soriano (2024) state that at the family level, higher education is perceived as enhancing the family’s social status. Parents and guardians invest significant financial resources in their children’s education, perceiving that studying abroad offers greater ease and prestige (Mambo et al. 2016). This investment is based on the premise that graduates from international institutions will secure superior employment opportunities, make positive contributions to national development, and support their families.

Students from Malawi aim to expand their knowledge and skills, gain exposure to diverse cultures, and establish professional networks that will benefit their future careers. The likelihood of enhancing job prospects and the chance to attend various educational institutions are primary motivations for students seeking education in the USA, Great Britain, Canada, and Australia (Research et al. 2014).

However, not all these students succeed in obtaining their education abroad. Identified deficiencies in the literature encompass the insufficient understanding of the experiences of returning students who lack a degree. The returnees face a poorly researched array of issues concerning their social, economic, psychological, and cultural rehabilitation. This study addresses the inadequate understanding of the experiences of Malawian returnees who did not finish their higher education degrees abroad. This study addresses the following research question: What sociocultural challenges do Malawian returnees encounter when reintegrating after failing to complete their degrees abroad? What are the economic consequences of returning without a degree for financial stability and employment? How does returning without a degree affect psychological well-being, and what stressors/supports shape these outcomes?

To measure financial stability, the investigators use objective and subjective indicators that evaluate the perceived economic security and financial management abilities of returnees. Items from the Financial Well-being Scale (FWB) help measure financial stability through assessments of returnees’ ability to pay living costs, handle unexpected financial problems, and maintain confidence in their financial future. The evaluation tools measure three key financial factors: income adequacy, savings sufficiency, and financial management confidence, which collectively determine someone’s financial stability level.

The research uses regression models to analyse how financial stability relates to employment status, job security, and other socioeconomic factors that affect personal financial well-being. The operationalisation method combines personal reports about financial security status with specific metrics, including employment status and income level. Financial stability emerges from a two-part evaluation system that combines personal economic security perceptions with tangible financial actions and conditions, which distinguishes it from other related measures, including job security and debt levels.

This significant study addresses a critical and underexplored issue: the reintegration of Malawian students who discontinue their studies and return home from international universities without obtaining their diplomas. Investigating their experiences aims to formulate targeted strategies and policies that facilitate their reintegration into society. This research aims to provide an understanding of the social, economic, psychological, and cultural dimensions of their experiences, and the proposed recommendations are expected to mitigate the issues confronting these returnees significantly. Moreover, the study’s findings will enhance the international education and student mobility research agenda, offering valuable insights for policymakers, educators, and support groups.

Existing research on overseas returnees and college dropouts highlights the social, economic, psychological, and cultural challenges they face. However, most studies focus on students from high-income countries (e.g., the U.S., Germany, and India) or global South contexts outside Malawi (Goffman 2022; Alhamad and Singh 2024; Hillmert et al. 2017; Nam and Marshall 2022). For instance, Goffman’s framework (2022), developed in the U.S. context, posits that returnees and dropouts experience social exclusion and diminished self-esteem, while Spady’s (1971) foundational work on social integration remains influential but may not account for recent shifts in migration and education trends. Notably, Malawian students are absent from these discussions despite the country’s unique socioeconomic landscape and increasing rates of educational migration.

Economically, returnees globally face underemployment and credential devaluation (Rosenzweig 2008; King and Raghuram 2013); however, research on low-income African nations, such as Malawi, is sparse. Similarly, psychological studies emphasise reverse culture shock and mental health risks (Adler 1981; Szkudlarek 2010), but culturally tailored interventions for Malawian returnees remain unexplored. For example, while Cage and Howes (2020) highlight neurodivergent students’ vulnerabilities in Western contexts, Malawi’s limited mental health infrastructure may exacerbate these challenges differently.

Culturally, returnees globally struggle with identity confusion (Sussman 2002; Dustmann and Görlach 2015), but prior work has focused on migrants moving between vastly dissimilar cultures (e.g., East-West dynamics), overlooking intra-African migration or the collectivist societal norms of Malawi. Similarly, policy recommendations for reintegration (e.g., Berry 1997; King and Raghuram 2013) derive from high-income settings and may not align with Malawi’s resource-constrained systems. To our knowledge, no studies to date have examined how Malawi’s cultural values, familial expectations, or informal support networks shape the experiences of returnees.

This gap is critical: Malawi’s rising educational migration rates and its distinct sociocultural and economic realities suggest that global findings may not apply. By centreing Malawian students, this study addresses three unresolved questions in the literature: (1) How do Malawi-specific cultural and economic structures mediate returnees’ reintegration? (2) What role do localised spiritual/community practices (e.g., Ubuntu frameworks) play in coping strategies? (3) How can policy interventions be adapted to low-resource contexts? Existing research, while foundational, lacks this contextual nuance, underscoring the need for the present inquiry.

Methods and materials

This study employs a convergent mixed methods design to provide complementary insights into the challenges faced by returnees. The quantitative analysis, including descriptive statistics, regression, and SEM, identifies broad patterns and relationships (Banda et al. 2023), while the qualitative data from in-depth interviews offer a deeper, contextual understanding (Banda et al. 2024) of these issues. The integration of both data sets through triangulation enhances the validity of the findings by cross-verifying results (Banda and Liu 2025) and providing a comprehensive view of the reintegration process, resulting in more robust and dependable conclusions.

While the quantitative research highlights key determinants such as community judgement and financial issues, the qualitative interviews explore the underlying narratives, revealing additional themes and issues not captured by the survey.

Sample size and recruitment for interviews

The study targeted Malawian students who returned from international higher education destinations after failing their degree programmes. The data was collected between June 10, 2022 and September 3, 2022. Given the challenges of accessing this specific population, snowball and purposive sampling techniques were employed to recruit 143 participants. Snowball sampling, where seed subjects recruit future subjects from among their acquaintances (Banda et al. 2024), was particularly effective for reaching distant or “hidden” populations (Heckathorn 1997).

The inherent limitations of snowballing, including homophily bias and restricted network reach, were mitigated through the recruitment of multiple seeds strategically selected to maximise demographic and geographic diversity (Banda and Liu 2025). Seeds were drawn from distinct subgroups to broaden referral chains and reduce the overrepresentation of homogeneous networks. This approach enhanced sample heterogeneity, ensuring the inclusion of perspectives from marginalised or socially isolated individuals often excluded in single-seed designs.

While residual bias remains inherent to the method, the use of diversified seeds strengthened the sample’s representativeness, aligning with best practices for studying hard-to-reach populations. This approach was complemented by purposive sampling to ensure the inclusion of participants who could provide rich, detailed insights into their experiences, thereby enhancing the depth and validity of the findings (Banda and Liu 2025; Palinkas et al. 2015). In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of 30 returnees. This sample size was deemed sufficient to achieve data saturation, where no new themes or insights emerged from additional interviews (Guest et al. 2006; Banda et al. 2024).

Instrument development, validation, and reliability

A structured questionnaire was developed to collect quantitative data, drawing on validated instruments from previous studies on international student experiences and academic failure (Bodycott 2009). To assess the post-return experiences of Malawian returnees, relevant items from Bodycott’s (2009) instrument were integrated with those from other validated scales. Specifically, items addressing psychological adjustment, such as feelings of emotional overwhelm and stress following return, were included to complement the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 in measuring anxiety and depression. Additionally, questions on identity loss and cultural reintegration were selected to capture the challenges of adjusting to home culture after studying abroad, aligning with the broader themes of social stigma and identity issues measured in other instruments. Social reintegration was assessed with items related to community isolation and relationship changes, which were combined with measures of social support from the SSQ-6 and FSS. This mixed approach ensures comprehensive measurement (Banda et al. 2025) of the psychosocial and cultural challenges returnees face, while seamlessly aligning with the economic and financial constructs captured in the study.

Item reduction rationale and criteria

Item reduction was undertaken to minimise respondent burden, mitigate survey fatigue, and enhance participation rates while preserving the psychometric integrity and theoretical coherence of the instrument. By streamlining scales, the study prioritises statistical power through higher response rates without compromising construct validity.

Items were removed based on redundancy (duplicate measurement of identical constructs), weak factor loadings in prior validation studies (e.g., items explaining <5% variance in exploratory factor analyses), and low contextual relevance to the study’s core focus on post-return reintegration. Clinically validated tools (e.g., PHQ-9, GAD-7) were retained in full to ensure diagnostic comparability, while multidimensional scales (e.g., Perceived Stigma Scale, Social Identity Scale) were truncated to retain items with the highest discriminant validity and alignment with the study’s theoretical framework. Cross-loading items were critically reviewed and excluded unless they contributed unique variance to overlapping constructs (e.g., cultural dissonance versus identity loss). This approach balanced brevity with methodological rigour, ensuring the instrument remained robust, culturally relevant, and statistically interpretable. Pretesting was conducted to ensure the reliability and validity of the study. The final set of items is in Table 1.

Social support

The study examines several types of support mechanisms that play distinct roles in the psychological well-being and successful reintegration of returnees, including familial support, institutional support, and community support. Familial support was measured using the Family Support Scale (FSS), which captures the emotional and practical assistance provided by family members. Institutional support was assessed through the Institutional Support Scale (ISS), which evaluates the effectiveness of government policies and programmes designed to support returnees. Community support was measured using the Community Integration Questionnaire (CIQ) and the Social Identity Scale (SIS), with a focus on community intervention and reintegration experiences. These instruments collectively define the operational concept of “support mechanisms” in this study, highlighting how each source contributes differently to the emotional resilience and overall well-being of the returnees.

The differentiation between these forms of support is essential to understanding their unique roles in shaping the returnees’ reintegration process. Familial support primarily addresses the emotional and logistical assistance offered by family members, while institutional support refers to the policies and interventions implemented by governments or organisations to facilitate reintegration. Furthermore, community support, assessed through the CIQ and SIS, emphasises the role of community participation and the sense of belonging that returnees experience upon re-entering their society.

To assess the psychological and emotional well-being of returnees, the study incorporated the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to measure anxiety and depression. These instruments were supplemented with items from Bodycott’s instrument to capture emotional distress, social alienation, and cultural dissonance, which may not be fully represented by the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 alone. These additional items, focusing on cultural reintegration and identity loss, were essential to understanding how returnees perceive their sense of belonging and cultural adjustment, complementing the insights gained from the SIS and CIQ.

In addition to these instruments, the study used the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ-6) to measure the basic perceptions of social support, addressing the first study question. The Perceived Stigma Scale was employed to capture social stigma, assessing key dimensions without overwhelming respondents. Finally, the use of these validated scales ensured that the data collected on financial stability, job insecurity, and economic hardship were robust, reliable, and relevant to the study’s focus on the economic dimensions of reintegration. These instruments, renowned for their brevity and high reliability, provided a comprehensive understanding of the psychosocial challenges faced by returnees during the reintegration process.

Financial well-being

To address the second research question, the Financial Well-being Scale (FWB) was employed to assess returnees’ perceptions of financial stability. The FWB evaluates individuals’ ability to meet their financial needs and their overall sense of financial security. Key items selected from the FWB, as indicated in Table 1 were included to capture participants’ sense of economic security and their confidence in managing daily financial demands. This scale was chosen for its brevity and strong reliability, offering a clear indicator of financial stability that aligns with the study’s focus on economic challenges.

To assess employment insecurity, the study incorporated the Job Insecurity Scale. This scale measures returnees’ perceptions of job stability, a crucial factor influencing economic reintegration. The Job Insecurity Scale was adopted for its established psychometric reliability and its relevance to understanding the employment-related struggles of returnees, particularly in the context of reintegration. In addition, the study utilised the Economic Hardship Index to evaluate the broader economic challenges returnees face, including financial strain, insufficient income, and debt. The Economic Hardship Index was chosen due to its well-documented validity in measuring financial difficulties, making it an ideal tool for understanding the economic exclusion experienced by returnees.

Psychological well-being

To effectively answer research question 3, the study utilised the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to assess the psychological well-being of returnees, specifically focusing on anxiety and depression. These instruments were chosen for their brevity, reliability, and strong psychometric properties, making them well-suited for large-scale surveys where efficiency and precision are critical. The GAD-7 is widely recognised for its effectiveness in measuring anxiety symptoms, with robust validation across diverse populations. The PHQ-9 is the gold standard for assessing depression severity and is widely used in clinical and research settings due to its strong diagnostic accuracy and ease of use. These scales were preferred over alternatives, such as the Beck Depression Inventory or the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), due to their shorter format, making them more feasible for survey-based research in a population of returnees, while still providing reliable and clinically meaningful assessments of mental health.

Instrument reliability

To ensure the reliability and validity of the survey instrument, Cronbach’s Alpha, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Measure of Sampling Adequacy, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were conducted. Cronbach’s Alpha demonstrated high internal consistency (α = 0.82), indicating the reliability of the measurement of the constructs (Cobern and Adams 2020). The KMO measure confirmed the sampling adequacy for factor analysis (KMO = 0.79) (Kaiser 1974), while Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity supported the suitability of the data for structure detection (χ2(105) = 652.34, p < 0.001) (Bartlett 1950).

An exploratory factor analysis with Varimax rotation was conducted to identify the latent constructs underlying the 43-item instrument. A four-factor solution emerged, explaining 62.4% of the total variance. Factor loadings ≥0.40 were retained, with cross-loadings ≤0.30 indicating discriminant validity (Tabachnick and Fidell 2019). Table 2 summarises the exploratory factor analysis.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the four-factor measurement model (Economic Exclusion, Psychological Distress, Support Deficits, Cultural Reintegration) identified during exploratory factor analysis. The model exhibited excellent fit to the data: χ2(224) = 278.15, p = 0.08; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI: 0.02–0.06); SRMR = 0.03 (Hu and Bentler 1999). All items loaded significantly (p < 0.001) on their respective factors, with standardised loadings ranging from 0.58 to 0.88. Composite reliability values (0.78–0.91) and average variance extracted (0.52–0.64) confirmed internal consistency and convergent validity. Discriminant validity was supported, as maximum shared variance (MSV < AVE) and interfactor correlations (r = |0.29–0.52|) did not exceed 0.70 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Economic Exclusion correlated moderately with Psychological Distress (r = 0.52, p < 0.01) and Support Deficits (r = 0.38, p < 0.01), while Cultural Reintegration showed inverse relationships with Psychological Distress (r = −0.34, p < 0.01) and Support Deficits (r = −0.41, p < 0.01). These results validate the structural coherence of the measurement model, warranting its use in advanced analyses.

The interview guide was designed procedurally to encompass several essential elements that guarantee the instrument’s durability and pertinence. A literature review was conducted on the experiences of overseas students, academic failures, and challenges of reintegration. This assessment provided an overview of the primary topics and issues faced by returnees, aiding in the development of the interview guide. Subsequently, experts in higher education, psychology, and qualitative research methods examined the draft of the interview guide. Their comments were utilised to enhance the questions, ensuring they were thorough, clear, and attuned to participant experiences.

The interview guide was pretested with several returnees who were not included in the study sample. The pilot phase was crucial in determining if the questions were confusing or challenging to answer, allowing for refinement. Participants in the pilot study were used to evaluate the clarity and coherence of the questions and to implement requisite modifications in the phrasing and sequence of the questions. The interview guide was modified iteratively based on the findings from pilot testing. This method involved multiple cycles of evaluation and adjustment of the instrument to reflect the complex nature of returnees’ experiences accurately.

Data collection and associated challenges

The survey link was disseminated through multiple channels, including emails, social media platforms, and community networks. To maximise accessibility and response rates, a bifurcated approach was utilised, combining online and offline distribution methods. Online responses were collected via an electronic survey platform optimised for accessibility on various devices. For participants with limited digital access, physical copies of the questionnaire were distributed in person.

This dual approach facilitated broad participation and minimised potential biases associated with a single mode of data collection (Creswell and Plano Clark 2017). The study achieved an overall response rate of 59.6% (N = 143/240), with offline surveys yielding a 66.7% response rate (80/120), aligning with AAPOR (American Association for Public Opinion Research) standards for face-to-face surveys, and online surveys a 52.5% rate (63/120). Participants in both modalities received standardised monetary incentives to bolster participation and mitigate non-response bias, a strategy aligned with best practices for enhancing engagement in mixed-method research. The higher offline response rate likely reflects the immediacy of incentive delivery and reduced attrition inherent to face-to-face administration, whereas the online cohort’s moderate rate aligns with typical digital survey trends despite incentivisation. Both rates exceed the thresholds for statistical power in hypothesis testing (α = 0.05, β = 0.80) with the final sample (N = 143). Post hoc representativeness checks confirmed minimal demographic disparities between modes.

Qualitative data was collected via structured interviews with purposefully selected returnees. This sampling strategy facilitated the inclusion of participants capable of providing more extensive descriptions of their experiences. The interview guide was designed to elicit detailed accounts of the participants’ educational experiences, challenges, coping techniques, and reintegration processes. Interviews were conducted in English and Chichewa to accommodate language preferences and to obtain more comprehensive responses. Each interview was done with the participant’s consent and recorded audibly for further transcription and analysis.

Acquiring data from this group presented specific problems, as detailed below. Their circumstances may be humiliating, stigmatising, and emotionally distressing, rendering the returnees a difficult-to-access and vulnerable demographic. Recruiting participants proved challenging due to the stigmatised nature of their experiences. Many returnees faced social rejection and shame in their communities, which led to a reluctance to openly discuss their academic setbacks. To address these issues, the study team implemented the following measures to foster trust and maintain confidentiality.

Initial participants were identified through collaborative partnerships with the international student offices of overseas universities, which maintain administrative records of all enrolled students (including non-graduates), as well as with Malawian institutions such as embassies, consulates, and the Ministry of Education’s scholarships and training division. These entities provided anonymised contact information—personal identifiers (e.g., names, national IDs) were removed or encrypted—for students who had enrolled in international programmes but did not graduate.

Complementing this, alumni networks of Malawian students abroad (including the Association of Malawian Students in China and the Association of Malawian Students in India) facilitated access to returnees through their membership registries. This dual approach balanced methodological rigour with ethical safeguards, as researchers could not link anonymised data (e.g., encrypted emails) to individual identities, thereby mitigating risks of unintended disclosure.

The key issue was establishing relationships with participants. The authors emphasised that the research was done anonymously, ensuring that participants’ identities and comments remain confidential. This confidence was crucial to motivating participants to articulate their experiences. Interviews were conducted in a secure and comfortable environment, utilising a peaceful location and/or the participants’ online platforms.

Moreover, researchers articulated the study’s objective and the potential benefits of volunteer engagement, including the development of enhanced support for future repatriates. This method effectively diminished the participants’ hesitance, resulting in more frank and cohesive comments.

Data validation

Reflexivity and intercoder reliability enhanced qualitative rigour. Two researchers independently coded 30% of transcripts, achieving 85% consensus. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and refining the codebook. Thick description and member checking were incorporated. Five participants reviewed the thematic summaries to validate the accuracy of the transcripts, while peer debriefing with external scholars critiqued the thematic interpretation. An audit trail tracked coding decisions, raw data, and analytical iterations. Table 2 summarises the validation techniques used in this study.

Data analysis

The knowledge produced and disseminated employed both quantitative and qualitative methodologies to elucidate the experiences of the returnees. Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS 26, employing descriptive statistics to examine demographic factors and critical variables. Chi-square tests, t-tests, and multiple regression analysis were used to determine the relationship between variables and the predictors of reintegration success (Field 2018).

T-tests are appropriate for comparing means between two distinct groups, such as employed versus unemployed returnees, to assess differences in psychological well-being. Multiple regression enables the examination of the influence of multiple independent variables on a dependent variable while controlling for confounding factors. Finally, SEM is ideal for testing complex relationships between latent variables, such as community integration and psychological well-being, and examining direct and indirect effects. Power analysis supports the use of SEM, ensuring valid results with medium effect sizes. These methods collectively provide a comprehensive analysis of the reintegration process among returnees.

The linearity assumption was confirmed through scatterplots showing a linear relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Homoscedasticity was validated with a residuals versus fitted plot, which displayed constant variance across all levels of fitted values. The normality of residuals was supported by a histogram and kernel density estimate (KDE), with a Shapiro–Wilk p value of 0.095, indicating normality. Outliers and influential points were assessed using Cook’s Distance, with all values remaining below the threshold of 1, suggesting no undue influence from individual data points, as shown in Fig. 1.

The multicollinearity assumption was checked by calculating the Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs), which showed values ranging from 3.2 to 5, indicating no significant multicollinearity between the independent variables. These results suggest that the data is suitable for regression analysis.

The qualitative data were examined by thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase process. The initial phase involved open coding to identify the principal themes within the data, followed by axial coding to examine the interrelationships among these themes. The final stage involved selective coding to construct a narrative elucidating the participants’ overall experiences. NVivo 12 facilitated the methodical and rigorous examination of the gathered qualitative data.

Handling missing data

To handle missing data in this study, we used the Full Information Maximum Likelihood method (FIML), which is particularly suited to the SEM framework employed in our CFA and latent variable analyses. FIML was selected for its capacity to utilise all available data without listwise deletion, thereby preserving statistical power and maintaining the integrity of complex models. This approach is robust under missing-at-random (MAR) assumptions, making it ideal for datasets with small to moderate missingness, even though survey items were designed as compulsory to minimise incomplete responses. A key strength of FIML lies in its avoidance of imputation biases, thereby preserving the relationships between latent constructs, such as Economic Exclusion and Psychological Distress. Its direct integration with SEM software aligns with the study’s CFA results, which demonstrate an excellent model fit (CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.04). Additionally, its efficiency in retaining observed data points supports the analysis of interconnected variables, such as social support, stigma, and financial stability.

While multiple imputation is widely recommended for general regression contexts, FIML is superior in this SEM-focused design due to its inherent compatibility with latent variable structures. SEM requires methods that respect the covariance matrix and theoretical coherence between measurement and structural models, both of which FIML inherently addresses. FIML reinforces the methodological rigour required to explore the study’s multidimensional constructs by ensuring consistency across the CFA validation process and subsequent structural analyses. This approach safeguards against biases introduced by ad hoc imputation and aligns with best practices for psychometric validation in mixed-methods research. Table 4 lists the variables to be measured.

Variable declaration

Findings

Table 2 summarises the key demographic characteristics and survey responses of the 143 returnees who participated in the study. The results highlight the social, economic, psychological, and cultural challenges these individuals face upon returning home without completing their higher education degrees abroad.

The thematic analysis identified four central themes that contextualise and expand upon the quantitative findings, revealing four central themes: Economic Exclusion and Credential Neglect, Psychological Distress and Social Stigma, Institutional and Communal Support Deficits, and Spiritual Coping and Communal Ambivalence. These themes are interrelated, with economic exclusion and credential neglect influencing psychological distress, which in turn was exacerbated by the lack of adequate support from institutional and communal sources. Spiritual coping, though beneficial, was often undermined by societal rejection and ambivalence toward returnees’ struggles. Below, these themes are presented with integrated quantitative and qualitative narratives.

The structural equation model evaluated relationships among financial stability, social support, community judgement, psychological well-being, and reintegration success. The model demonstrated an excellent fit to the data, as indicated by the fit indices (RMSEA = 0.045, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95; Table 3), meeting the conventional thresholds for acceptability. The structural equation model demonstrated robust psychometric properties, with composite reliability values ranging from 0.78 to 0.91, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Monte Carlo power analyses (1000 replications, α = 0.05) confirmed statistical power of 0.85 to detect medium effect sizes (β ≥ 0.30), aligning with benchmarks for SEM robustness (Muthén and Muthén 2002). Bootstrapped standard errors for all path coefficients (range: 0.05–0.11) affirmed the precision of estimates, with critical pathways such as Financial Stability → Reintegration Success (β = 0.45, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001) and Community Judgement → Psychological Well-being (β = −0.25, SE = 0.09, p < 0.01) demonstrating stability. While the sample size (N = 143) fell below the conventional “10 cases per parameter” heuristic, the model’s parsimony (43 parameters), strong factor loadings (range: 0.58–0.88), and discriminant validity (maximum shared variance < average variance extracted) mitigated overfitting risks (Kline 2016).

Path coefficients (Table 4) revealed that financial stability exerted the strongest direct effect on reintegration success (β = 0.45, p < 0.001), followed by social support (β = 0.32, p < 0.01).

Community judgement, conversely, directly reduced psychological well-being (β = −0.25, p < 0.01) and indirectly undermined it by eroding social support (β = −0.30, p < 0.01). Together, these pathways explained 58% of the variance in psychological well-being and 49% of the variance in reintegration success (Table 5), underscoring the model’s robust explanatory power.

Economic exclusion and credential neglect

Quantitative data revealed systemic labour market biases, with 69% of returnees reporting unemployment or underemployment (Table 2), compounded by employers’ dismissal of partial international credentials. Structural equation modelling (SEM) identified financial stability as the strongest predictor of reintegration success (β = 0.45, p < 0.001; Table 4), yet 76% cited diminished employment opportunities (Table 2). A regression model identified employment status (β = 0.52, p < 0.001) as the strongest predictor of financial stability (Table 6), accounting for 27% of its variance.

Quantitative analyses established employment status as a critical determinant of reintegration outcomes, with regression models identifying credential devaluation (β = 0.41, p < 0.01) and familial pressure (β = 0.33, p < 0.05) as primary mechanisms of financial instability.

These statistical trends find empirical grounding in Theme 3 narratives, which detail systemic labour market biases against partial international credentials. For instance, a returnee with two years of engineering coursework abroad explained, “Employers dismissed my technical training as ‘incomplete’—my skills were deemed invalid without a degree. I now repair phones in a market stall, earning a fraction of my expected salary.” Such accounts operationalise the quantitative findings, illustrating how structural credential neglect entrenches economic marginalisation. Familial repercussions further compound this exclusion, as exemplified by one participant’s account: “My parents liquidated assets to fund my education. My return triggered accusations of generational betrayal—‘You’ve ruined us,’ they said.” These narratives crystallise the regression coefficients, demonstrating how macroeconomic biases and intergenerational expectations synergistically mechanise financial precarity.

Psychological distress and social stigma

Community judgement emerged as a significant predictor of sense of failure (β = 0.24, p = 0.001; Table 5), amplifying the severity of depression (β = 0.44) and anxiety (β = 0.35). Qualitative accounts from Theme 1 elucidate the psychosocial mechanisms underlying these coefficients, revealing how stigma becomes internalised as shame. A participant’s reflection—“Community leaders labelled me a ‘lesson’ for others—a cautionary tale against ambition. Their lectures at community meetings framed my return as moral failure, not circumstance”—exemplifies the socio-cognitive processes that transform communal judgement into psychological harm. Similarly, another participant’s withdrawal from social spaces—“I stopped attending weddings. My presence invited whispers such as ‘There’s the one who wasted his chance’—demonstrating how external stigma metastasises into self-imposed isolation.

Besides all this, social support fragmentation was evident in institutional responses: “The clinic referred me to a church group… they offered prayers, not help.” Community stigma exacerbated isolation, with one returnee noting, “Neighbours called me a ‘wasted investment,’” illustrating stigma’s internalisation. Age-related pressures compounded distress, as a 30–34-year-old shared, “Returning without a degree felt like a younger person’s mistake.” Male returnees faced gendered expectations: “I was labelled a ‘failure’… without the degree, I was nothing.”

The reintegration struggles of Malawian students returning without degrees are profoundly mediated by gendered societal expectations, which shape the nature of stigma and its psychological repercussions. Male returnees frequently described stigma rooted in patriarchal norms that equate academic success with masculine responsibility. One participant articulated this pressure: “My uncles called me ‘mwana wa matsoka’ [a child of misfortune], accusing me of shaming our lineage. They said, ‘How will you lead a family without a degree?’ Even my younger cousins mock my ‘empty hands.’” Here, the failure to complete a degree is framed not merely as a personal shortcoming but as a collective familial disgrace, eroding the participant’s perceived capacity to fulfil culturally inscribed roles as a provider and leader.

In contrast, female returnees narrated stigma tied to disrupted marital prospects and moral censure. A young woman recounted the dissolution of her engagement following her return: “My fiancé’s family cancelled our marriage, claiming a woman who returns ‘incomplete’ brings matsoka [misfortune] to a household. Now, my mother calls me ‘mtundu womvetsa chisoni’ [a pitiful creature].” This narrative highlights how women’s social value is contingent upon educational attainment as a prerequisite for marriage, with failure abroad being interpreted as a moral flaw rather than a circumstantial adversity. The resultant exclusion amplifies anxiety, as women are relegated to the margins of socially sanctioned roles.

Age intersected with gender to compound stigma, particularly for older returnees. A 30-year-old man described being ostracised for defying age-graded expectations of stability: “At my age, people expect you to be a father, a homeowner. However, here I am, jobless, called ‘galu wa m’mudzi’ [the village fool]. My peers whisper, ‘He’s too old to start over.’” This infantilisation—framing his return as a “younger person’s mistake”—reflects a societal conflation of age with competence, where incomplete education destabilises one’s claim to adult legitimacy.

Institutional responses further entrenched these gendered dynamics. A 24-year-old woman reported dismissive counsel from a mental health professional: “The counsellor told me, ‘Pray for a husband instead of crying over degrees—that’s a woman’s true success.’” Such narratives reveal how systemic neglect reinforces cultural scripts, redirecting women’s aspirations toward marital fulfilment rather than addressing their psychological or economic needs.

These accounts collectively illustrate how stigma operates as a gendered mechanism of social control. For men, failure abroad destabilises their claim to patriarchal authority, while for women, it invalidates their eligibility for marriage, a cornerstone of feminine identity in many Malawian communities. Older returnees, irrespective of gender, face an additional layer of marginalisation, as their age renders their “incompleteness” incongruent with societal expectations of life-stage achievement. These qualitative patterns align with the study’s broader quantitative findings, where community judgement and eroded social support emerged as critical predictors of psychological distress. By centreing returnees’ voices, the analysis reveals how stigma is not a monolithic force but a culturally mediated process, demanding interventions that address the intersection of gender, age, and systemic neglect in shaping post-return trajectories.

Institutional and communal support deficits

While social support demonstrated a positive association with psychological well-being (β = 0.29, p < 0.001; Table 5), only 29% of returnees reported adequate mental health assistance (Table 1), exposing a critical policy-practice gap. Theme 2 narratives unpack this dissonance, revealing systemic inadequacies in institutional responsiveness. A participant’s account of fragmented care—“The district hospital’s psychologist redirected me to an NGO, which referred me back to the hospital. This cycle continued until I gave up”—epitomises the bureaucratic inertia that undermines quantitative associations between support and well-being. Familial dynamics further complicate this picture: though familial aid correlated with reduced distress (β = 0.18, p < 0.05), qualitative data reveal its conditional nature. One returnee noted, “My siblings helped financially but demanded silence about my struggles. ‘Don’t embarrass us further,’ they warned.” These accounts bridge the statistical and experiential, illustrating how pragmatic constraints and cultural taboos frequently negate the theoretical benefits of support.

Spiritual coping and communal ambivalence

Spiritual support exhibited a modest yet significant predictive value for well-being (β = 0.22, p = 0.001; Table 5), with 54% of returnees reporting that spiritual practices helped build their resilience (Table 1). However, Theme 4 narratives expose a paradox: while spirituality provided private solace, communal ambivalence often negated its benefits. A participant’s experience—“Prayer stabilised my mental state, but my denominational committee sidelined me in leadership roles. ‘Your failure reflects poor faith,’ they claimed”—highlights the tension between individual coping and collective judgement.

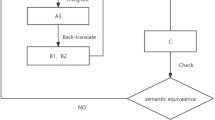

Similarly, familial scepticism toward spiritual practices—“I meditated daily, but my family mocked it as ‘escapism’”—reveals how communal norms mediate the efficacy of coping strategies. This dissonance between private solace and collective judgement reframes the quantitative significance of spiritual coping, illustrating how societal norms mediate its efficacy. Spiritual coping’s duality surfaced in narratives like “Prayer gave me hope, but my church group avoided me,” aligning with ambivalent quantitative trends. These qualitative insights reframe the quantitative findings, demonstrating that the statistical significance of spiritual support belies its sociocultural limitations as returnees navigate the dual burden of personal recovery and communal scrutiny. The findings of this study reveal the complex interplay between social, economic, psychological, and cultural challenges faced by these returnees as seen in Fig. 2.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the four key themes—Economic Exclusion and Credential Neglect, Psychological Distress and Social Stigma, Institutional and Communal Support Deficits, and Spiritual Coping and Communal Ambivalence—are interrelated, with economic exclusion exacerbating psychological distress, which in turn is intensified by a lack of adequate institutional and communal support. The mediation analysis shows how Community Judgement negatively impacts Psychological Well-being, directly and indirectly through the erosion of Social Support, highlighting the significant barriers returnees face.

Discussion

This discussion is organised to mirror the four core themes identified in the Results—Economic Exclusion and Credential Neglect; Psychological Distress and Social Stigma; Institutional and Communal Support Deficits; and Spiritual Coping and Communal Ambivalence—before considering policy implications and alternative directions. Each section integrates quantitative findings, qualitative narratives, and established theory to maintain analytic rigour and narrative clarity.

Economic exclusion and credential neglect

Quantitative data indicate that 69% of returnees faced unemployment or underemployment, and 76% reported experiencing diminished employment opportunities (Table 2). Structural equation modelling (SEM) confirms financial stability as the strongest predictor of reintegration success (β = 0.45, p < 0.001; Table 7). These patterns align with Rosenzweig’s (2008) work on financial precarity, albeit without full qualifications, and King and Raghuram’s (2013) observation that incomplete international credentials are often denominated in local currency. Qualitative accounts bring this to life:

Family expectations further compound exclusion, with one participant describing parental reproach—a moral indictment that echoes systemic neglect of credentials. Moreover, Malawi’s broader context—characterised by 40% youth unemployment and inflation exceeding 25%—intensifies these dynamics. Taken together, individual- and structural-level forces synergise to entrench economic marginalisation among non-graduating returnees.

Psychological distress and social stigma

Sixty-five per cent of returnees reported depressive symptoms and 71% anxiety, reflecting reverse culture shock (Adler 1981; Szkudlarek 2010). SEM reveals that community judgement both directly undermines psychological well-being (β = –0.25, p < 0.01) and indirectly erodes social support (β = –0.30, p < 0.01), accounting for 58% of the variance in well-being (Tables 8 and 9). Qualitative themes illustrate internalised stigma. Gender and age norms mediate this stigma. Male returnees describe patriarchal reproach, while female returnees face marital exclusion. Such accounts demonstrate that communal judgement operates as a culturally coded mechanism of control, compounding anxiety and depression beyond individual expectation management.

Institutional and communal support deficits

Although higher social support predicts better psychological outcomes (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), only 29% of returnees received adequate mental health care (Table 2). Participants recount bureaucratic fragmentation. These narratives highlight how nominal support frequently falls short of providing effective assistance, underscoring Cohen and Wills’ (1985) call for holistic, context-sensitive support mechanisms.

Spiritual coping and communal ambivalence

Spiritual practices offered modest buffering (β = 0.22, p = 0.001), and 54% of returnees reported finding solace through prayer (Table 2). Nevertheless, communal ambivalence frequently neutralised these benefits. Such dissonance between private resilience and public repudiation reveals that spiritual coping, while personally meaningful, remains vulnerable to social narratives of success and failure (Goffman 2022; Cultural Stress Theory).

Policy implications and the need for comprehensive support systems

These findings demand integrated interventions across social, economic, psychological, and cultural domains. Locally, economic empowerment—such as job placement and financial counselling—must dovetail with structural reforms to address market saturation and credential devaluation. Mental health services should combine individual counselling with community education to destigmatise non-degree returnees. Foreign universities share ethical responsibility: proactive advising, targeted financial aid, and ongoing mentorship can reduce attrition and downstream reintegration burdens.

Alternative views on policy directions

Some scholars advocate for strengthening domestic education and local job markets to reduce reliance on international pathways that often lead to unfulfilled expectations (Mambo et al. 2016). Bolstering Malawi’s higher education capacity and aligning curricula with local economic needs may preempt the economic and psychosocial fallout documented here. Addressing this requires nuanced, culturally grounded, and structurally informed policies that valorise partial international experiences and foster more inclusive definitions of success.

Limitations and directions for future research

This study is subject to several limitations that warrant consideration when interpreting its findings. First, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of recall bias and social desirability effects, particularly in sensitive domains such as post-return stigma, psychological distress, and employment challenges. While self-reporting captures subjective lived experiences, it may also lead to underreporting or distortion of socially undesirable realities.

Second, the modest sample size constrains the statistical power and limits the generalisability of the results, especially concerning the structural equation modelling (SEM) analyses. Although the study offers exploratory insights, its quantitative inferences should be viewed as indicative rather than definitive.

To address these limitations, future research should adopt longitudinal designs that track returnees across the migration trajectory—from pre-departure expectations through overseas experiences to post-return realities. This would enable a more robust analysis of reintegration patterns, evolving identity shifts, and labour market fit over time. Moreover, a mixed-methods approach integrating primary surveys with in-depth ethnographic interviews, employer assessments, and social network analyses would help triangulate findings and uncover contextual subtleties that escape standardised metrics.

Finally, cross-national collaboration on standardised returnee monitoring systems could enhance comparability across diverse migration regimes, while fostering evidence-informed and culturally responsive reintegration policies tailored to the needs of returnees from underrepresented regions such as Malawi.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Adler N. J (1981) Re-Entry: Managing Cross-Cultural Transitions Group & Organization Studies 6:341–356

Alhamad IA, Singh HP (2024) Predicting dropout at master level using educational data mining: a case of public health students in Saudi Arabia. Rev Amazon Investig 13(74):264–275. https://doi.org/10.34069/ai/2024.74.02.22

Banda L. O. L, Liu J, Banda J. T, Zhou W(2023) Impact of ethnic identity and geographical home location on student academic performance Heliyon 9:e16767

Banda LOL, Banda JT, Banda CV, Mwaene E, Munthali GN, Hlaing TT, Chiwosi B (2024) Unraveling agricultural water pollution despite an ecological policy in the Ayeyarwady Basin. BMC Public Health 24(1):14712458. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-14712-8

Banda LOL, Banda JT, Banda CV, Mwaene E, Msiska CH (2024) Unraveling substance abuse among Malawian street children: a qualitative exploration. PLoS ONE 19(5):e0304353. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304353

Banda LOL, Liu J (2025) Understanding international students’ academic performance in top-Chinese universities. Routledge, London and New York

Bank W, Malawi O (2021) Investing in digital transformation. www.worldbank.org/mw

Bartlett MS (1950) Tests of significance in factor analysis. Br J Stat Psychol 3(2):77–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1950.tb00285.x

Berry JW (1997) Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl Psychol 46(1):5–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Bodycott P (2009) Choosing a higher education study abroad destination: what mainland Chinese parents and students rate as important. J Res Int Educ 8(3):349–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240909345818

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cage E, Howes J (2020) Dropping out and moving on: a qualitative study of autistic people’s experiences of university. Autism 24(7):1664–1675. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320918750

Cobern W, Adams B (2020) Establishing survey validity: a practical guide. Int J Assess Tools Educ 7(3):404–419. https://doi.org/10.21449/ijate.781366

Cohen S, Wills T. A (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis Psychological Bulletin 98:310–357

Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2017) Designing and conducting mixed methods research, 3rd edn. SAGE Publications

Dustmann C, Görlach J-S (2015) Discussion paper series the economics of temporary migrations, Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration Department of Economics, University College London

Flanagan-Bórquez A, Soriano-Soriano G (2024) Family and higher education: developing a comprehensive framework of parents’ support and expectations of first-generation students. Front Educ 9:1416191. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1416191

Fornell C, Larcker D. F (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error J. Mark. Res 18:39–50

Field A (2018) Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics, 5th edn. Sage

Goffman E (2022) Stigma: notes on the management of spoilt identity. Prentice-Hall

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006) How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18(1):59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903

Heckathorn DD (1997) Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl 44(2):174–199. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096941

Hillmert S, Weber H, Groß M, Schmidt-Hertha B (2017) Informational environments and college student dropout. Springer, pp 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64274-1_2

Hu L.-t, Bentler P. M (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives Structural Equation Modeling 6:1–55

Kaiser HF (1974) An index of factorial simplicity Psychometrika 39:31–36

King R, Raghuram P (2013) International student migration: Mapping the field and new research agendas Population, Space and Place 19:127–137

Kline RB (2016) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 4th edn. Guilford Press

Mambo MM, Meky S, Tanaka N, Salmi J (2016) Improving higher education in Malawi for competitiveness in the global economy. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0798-5

Nam BH, Marshall RC (2022) Social cognitive career theory: the experiences of Korean college student-athletes on dropping out of male team sports and creating pathways to empowerment. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.937188

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K (2015) Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res 42(5):533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Research CFE, Enterprise LSE, & Council B (2014). Research and analysis on the benefits of international opportunities. British Council 1–107. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research_and_analysis_on_the_benefits_of_international_opportunities_cfe_research_and_lse_enterprise_report_0.pdf

Rosenzweig MR (2008) Higher education and international migration in Asia: brain circulation. [Special topic:] Higher education and development

Spady WG (1971) Dropouts from higher education: toward an empirical model. Interchange 2(3):38–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02282469

Szkudlarek B (2010) Reentry—a review of the literature. Int J Intercult Relat 34(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.06.006

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this manuscript, with the following specific roles: LOLB: conceptualisation, methodology design, data collection, data cleaning, formal analysis, supervision, and writing (both initial and final drafts). JB: conceptualisation, verification, data analysis, supervision, and writing of the final draft. CB: was responsible for data cleaning, data analysis, verification, and writing of the initial draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval from the Mzuzu University Research Ethics Committee (MZUNIREC). All research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Malawi’s National Research Ethics Guidelines, and other applicable regulatory standards governing research involving human participants. The committee issued approval number MZUNIREC/DOR/22/55 on June 2, 2022, formally authorising the commencement of the study. The scope of the approval permitted full implementation of the approved protocol, including a waiver of consent for minors, with the condition that any amendments to the protocol must be submitted for further approval prior to implementation. The approval was valid for 1 year and subject to renewal if the study was to be extended beyond that period. Since all data collection was finalised within the stipulated time, this study did not need any extension from the MZUNIREC.

Informed consent

Informed consent for this study was obtained in both written and oral formats, depending on participant accessibility. Written consent was acquired during face-to-face interviews, while oral consent was used for participants engaged remotely. Oral consent was necessary to ensure ethical participation of hard-to-reach individuals. In these cases, participants were read a standardised consent script, and their verbal agreement was audio-recorded in the presence of at least one colleague as a witness. A copy of the script used for oral consent has been included in the submission materials. Consent was obtained between June 10, 2022 and September 3, 2022, by trained members of the research team affiliated with Mzuzu University and the Beijing Institute of Technology, from Malawian students who had returned home without completing their higher education abroad. The scope of the consent included agreement to participate in the research, permission for data collection and analysis, and consent to publish anonymised findings in academic and policy-related outputs. Although the study did not involve minors directly, the Research Ethics Committee formally waived the requirement for parental or guardian consent, confirming that all participants were legal adults or emancipated individuals under the criteria of the study. Given participants’ potential vulnerability—due to social stigma, mental health distress, and community judgement—special care was taken to ensure that consent was freely given, fully informed, and uncoerced. As a non-interventional study involving questionnaires and interviews, all participants were fully informed that: Their anonymity would be strictly maintained; The purpose of the study was to explore reintegration challenges after returning from international education without a degree; Their data would be used solely for research, academic publication, and policy formulation; There were minimal risks, primarily emotional discomfort, for which referrals to support services were available if needed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Banda, L.O.L., Banda, J.T. & Banda, C.V. Dying in silence? Post-return challenges and unheard struggles of Malawian students who did not graduate abroad. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1274 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05651-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05651-9