Abstract

The US withdrawal from the World Health Organization involves the country ceasing its membership and financial contributions to the World Health Organization (WHO). This decision has several implications: The U.S. would save the funds it contributes to the global health body, which could be redirected to domestic health initiatives. It could also have more control over its health policies and responses without needing to align with the WHO guidelines. Nevertheless, the action may weaken the WHO’s ability to respond to global health crises. The US would lose its leadership role in global health, potentially diminishing its influence in international health policy. U.S. researchers and institutions might face reduced opportunities for international collaboration on health research and data sharing. Finally, Without WHO coordination, the U.S. might be less prepared for global health threats, potentially making Americans less safe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

President Donald Trump’s executive order, signed on January 20, 2025, to withdraw the United States (U.S.) from the World Health Organization (WHO) has sparked significant global debate and concern. This marks the president’s second attempt to sever ties with WHO (The White House 2025). The first attempt occurred in 2020 during his previous term but was reversed by President Biden upon taking office in 2021 (Gearan 2020). The decision has elicited mostly negative reactions. Many countries stressed the importance of international collaboration, and the WHO’s role, while raising concerns about the global ability to respond to future health crises effectively, calling for continued partnership, and urged the U.S. to reconsider (Ott 2025). The WHO has expressed regret over the decision, emphasizing the importance of continued collaboration for the health and well-being of millions of people worldwide (World Health Organization (2025a)).

Historical background and reasons for withdrawal

Historically, no other country has officially left the WHO, even though some countries have temporarily suspended their participation in the past. The expulsion of Taiwan (Republic of China) from the United Nations (UN) and its affiliated organizations, including the WHO, is a notable instance of the UN yielding to the demands of an assertive nation on October 25, 1971 (Chen and Cohen 2020). The People’s Republic of China (PRC) insisted on, not only joining the UN and the Security Council but also expelling the Republic of China. The UN adopted the ‘One China’ policy, deviating from its Charter, which otherwise could have allowed both nations to remain in the UN, similar to the situation with North and South Korea (Chen and Cohen 2020).

President Trump’s decision to withdraw the U.S. from the WHO is rooted in several key factors and historical context. During his first term, President Trump announced plans to withdraw from the WHO in 2020, citing dissatisfaction with the organization’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, its perceived lack of independence from political influences, particularly from China, and the financial burden placed on the U.S. as the largest contributor to the organization’s budget (The White House 2025; World Health Organization (2024a)). President Trump signed an executive order to withdraw the U.S. from the WHO on the first day of his second term. The decision was based on his earlier claims regarding the WHO’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, its failure to implement necessary reforms, and perceived political influence from member states. The order revokes previous actions to remain in the WHO and directs the cessation of U.S. funding and personnel involvement with the organization. The U.S. will also halt negotiations on the WHO Pandemic Agreement and related amendments (The House 2025).

The WHO funding and the U.S. economic burden

The WHO is funded through two main sources: 1) assessed contributions and 2) voluntary contributions. Assessed Contributions are mandatory dues paid by member states, calculated based on each country’s wealth and population. They provide predictable funding but cover less than 20% of WHO’s budget. Voluntary Contributions come from member states, other UN organizations, intergovernmental organizations, philanthropic foundations, the private sector, and other sources. They constitute most of WHO’s funding, categorized into a) Core Voluntary Contributions, fully flexible funds that WHO can allocate as needed, or b) Thematic and Strategic Engagement Funds, partially flexible funds that align with specific donors (World Health Organization (2024b)).

The U.S. share of mandatory contributions to the WHO during the two years from 2024 to 2025, was 22% with China coming in second at about 16%. The U.S. has historically been the top contributor to the WHO, contributing $1.284 billion during the 2022–2023 biennium (McCormick Hibbert (2025)). This funding supports WHO’s efforts to respond to emergencies, prevent the spread of diseases, address global health priorities, and help protect both the U.S. and the world from health threats, improving health and well-being, especially for vulnerable populations (World Health Organization (2024b); McCormick Hibbert (2025)).

The U.S. has been a crucial partner to the WHO, significantly contributing to global health security (World Health Organization (2024a)). This partnership includes efforts to eradicate polio, deliver humanitarian aid, and advance health surveillance and biolab security. The U.S. also supports WHO reforms to enhance efficiency and capacity-building in other countries. Additionally, the U.S. maintains a strong presence in WHO collaborating centers, providing expertise in various health fields, and reinforcing its commitment to global health leadership (World Health Organization (2024b); McCormick Hibbert (2025)). The absence of the U.S. may create an opportunity for other countries to step in and advance their own agendas.

The Impacts of China on the WHO

Although the politically driven impediment of Taiwan’s engagement in WHO, exemplified by the withdrawal of its temporary observer status after a Taiwanese governmental shift deemed politically unfavorable by Beijing serves as a salient case study of this broader influence, the China’s influence on the WHO has garnered considerable scholarly attention, especially within the discourse surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic (Mazumdaru 2020; Collins 2020; Chen and Cohen 2020). The critics highlight that the WHO has been too deferential to Beijing, especially regarding the initial handling of the COVID-19 outbreak. The WHO’s Director-General praised China’s efforts and transparency, despite reports of Chinese authorities suppressing information early on. They also mention that the WHO initially advised against travel restrictions to China, which some experts believe was to avoid antagonizing Beijing (Mazumdaru 2020).

Furthermore, the perceived shortcomings of the WHO in its response to China’s handling of the COVID-19 outbreak have allegedly compromised the organization’s credibility (Collins 2020). The credibility of the WHO is crucial for its effectiveness in global health (World Health Organization (2025b)). When its credibility is questioned, several consequences can arise. Firstly, if member states and the public lose trust in the WHO, they may be less likely to follow its guidance and recommendations. This can hinder the organization’s ability to manage health crises effectively. Moreover, credibility issues can result in reduced financial support from member states and other donors. This can affect the WHO’s ability to accomplish its programs and initiatives. Perceived bias or undue influence from powerful member states, such as China, can damage the WHO’s reputation as an impartial global health authority. This can lead to skepticism about its decisions and actions. In addition, a loss of credibility can result in operational challenges, as countries may be less willing to cooperate with the WHO. This can slow down the implementation of health interventions and responses to emergencies. Ultimately, the effectiveness of global health initiatives can be compromised. If the WHO’s credibility is undermined, it can affect the overall health outcomes and the ability to address global health threats (Collins 2020; World Health Organization (2025b); Larson 2022). Ensuring credibility is crucial for the WHO to achieve its goals, promoting health, safeguarding global safety, and supporting vulnerable populations.

This paper aims to investigate the national and global consequences of the U.S. withdrawal from the WHO.

Method

Study design

Using a systematic search combined with Action Research (Grant and Booth 2009; Ivankova and Johnson 2022), we conducted a narrative review focused on the relationship between the U.S. and the WHO and the positive and negative consequences the U.S. withdrawal may have on both organizations. Given the emerging status of the topic and its scarcity in peer-reviewed publications, a narrative review was deemed the most appropriate methodological choice. This qualitative synthesis strategy affords a less constrained framework for the evaluation of pertinent studies, thereby accommodating research endeavors with expansive, exploratory objectives. Such an approach is instrumental in furnishing a thorough overview, a nuanced interpretation, or a critical assessment of the subject, in lieu of addressing a tightly delimited research inquiry (Grant and Booth 2009). These reviews illustrate what knowledge and ideas have been established since the first U.S. attempt to leave the WHO, the strengths and weaknesses of these ideas, and identify controversies in the literature to formulate further research and inquiry questions.

Action Research (AR) is a well-established methodological approach with a long history of cross-disciplinary applications. It aims to address practical issues and foster positive change. The core principles of AR include generating evidence-based knowledge to enhance practice and empowering participants to drive change. It involves problem-solving and reflection. It follows four stages: reflecting, planning, acting, and observing. The process includes six steps: problem identification, fact-finding, planning, acting, evaluating, and monitoring. The core is the action or intervention, which involves development, implementation, and evaluation cycles, to answer arising questions during narrative review (Ivankova and Johnson 2022).

Combining the systematic search in this narrative review with AR offers a robust methodology for studying the topic. The combination enhances research value and academic contribution, especially when the subject matter is nascent, practice-oriented, or aims for practical change. The systematic search provides a rigorous, comprehensive foundation of existing knowledge, helping to identify known impacts, map the complex landscape of consequences, and pinpoint gaps in current understanding. This evidence-based approach minimizes bias and establishes a crucial baseline for the subsequent action. AR then builds on this foundation by engaging directly with the dynamic, multi-stakeholder context of global health policy. Its iterative “learn by doing” cycle allows for real-time observation, and intervention, enabling the identification and testing of practical solutions to mitigate the withdrawal’s effects. This participatory approach, not only fosters ownership and builds capacity among stakeholders, but also generates actionable knowledge that is highly relevant to policymakers, ensuring the study moves beyond theoretical analysis to practical impact, and system improvement (Toledano, Anderson (2020); Heikkinen et al., (2007); Clandinin and Connelly 2000).

Search strategy, engines, and databases

A systematic search using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS) scientific databases was performed to obtain related scientific publications. Google search engine was used to capture any other papers as part of the Action Research to answer any questions, raised during the investigation. Since the question of the U.S. leaving the WHO was raised in 2020, the search was limited to publications between 2020 and 2025 (as of February 16, 2025).

Search strings

The following keywords were used in combination or isolated; World Health Organization; United States; Withdrawal. Other keywords such as Collaboration, Global Health, and Consequences were added. Moreover, replacing withdrawal with synonyms such as disengagement, departure, and exit were tested. The final strings in all searches were World Health Organization AND United States AND Withdrawal. This is a good starting point for this systematic search. It’s concise and hits the core concepts.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All papers in English, scientific, or gray literature, published between 2020–2025, discussing both the pros and cons of the U.S. withdrawal from the world organization were included for review.

Results

Adding Global Health (n = 0) and Consequences (n = 0) did not result in eligible hits. Replacing withdrawal with synonyms such as disengagement (n = 218), departure (n = 263), and exit (n = 763) returned several hits that were found to be unrelated or out of the scope of this paper.

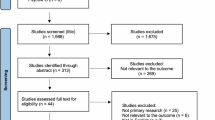

The first search using the final string: World Health Organization AND United States AND Withdrawal resulted in 64 articles: PubMed (n = 5), Scopus (n = 37), and WoS (n = 22). In the first review, titles and abstracts were carefully studied. One paper was a letter and was not included, 11 were duplicates, and 48 studies did not match the aims of this study. In the final step of literature selection, four studies were included (Table 1, and Fig. 1). All authors unanimously approved the included studies.

Synthesis of findings

All included articles were published before January 2025 when President Trump’s second term started. They reflect the reactions after President Trump’s first attempt to leave the WHO and provide a comprehensive view of the U.S. withdrawal from international organizations, its impacts, and the subsequent re-engagement under President Biden’s administration.

Although the executive order for withdrawal in 2020 cited the WHO’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic and financial concerns, some legal experts argued that the process of withdrawal, requiring a one-year notice, may not have been fully adhered to (Gostin 2021).

Several researchers believed the withdrawal could significantly affect global health initiatives, including funding, research collaborations, and training programs. Similarly, it could weaken the U.S.‘s ability to respond to global health threats and maintain health security (Gostin 2021).

Eichensehr (2021) described Biden administration’s re-engagement by rejoining the Paris Agreement to combat climate change, halting the U.S. withdrawal and re-engaging with the organization to address global health challenges, participating in the initiative to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines, seeking re-engagement and election to promote global human rights, and extending the arms control agreement with Russia, as a proof of the U.S. commitment to renewing American leadership and elevating diplomacy in U.S. foreign policy (Eichensehr 2021).

In their study investigating public opinion on International Organizations (IO), Borzyskowski and Vabulas (2024) showed that support for IO withdrawals was divided along party lines, with Republicans more likely to support them and Democrats generally opposing them. Public opinion was shown to be influenced by how the withdrawal is framed, with more support when framed as benefiting U.S. national interests. Announcements of IO withdrawals could influence candidate choice and policy support, suggesting their use in rallying domestic electoral support (Borzyskowski and Vabulas 2024).

Finally, Dijkstra and Ghassim (2024) explored why some international organizations (IOs) face more challenges from member states than others and could not provide any strong evidence of more authoritative IOs being more frequently challenged by member states. Instead, factors like preference heterogeneity, the existence of alternative IOs, and the democratic composition of membership are more influential. More authoritative IOs may experience fewer withdrawals, indicating a higher investment in resolving conflicts internally (Dijkstra and Ghassim 2024).

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the consequences of the U.S. withdrawal from the WHO. The outcomes of the included studies conducted after President Trump’s first effort to leave the WHO indicate the legal and practical consequences of such a decision and how public opinion can be affected by how such a withdrawal can be framed to achieve political gains. After the first term of President Trump in the White House, the Lancet Commission’s report evaluated the impact of President Trump’s health policies and the societal divides that led to his election (Woolhandler et al. 2021). It argues that President Trump exploited economic frustrations to fuel racial and xenophobic sentiments, benefiting the wealthy and corporations while harming public health. His policies included significant tax cuts, reduced healthcare access, environmental deregulation, and weakened public health responses, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. The report also noted that Trump’s actions accelerated long-standing neoliberal policies, increasing inequality and reversing progress in economic and racial justice, highlighting the need for comprehensive reforms, including raising taxes on the wealthy, implementing single-payer healthcare, and adopting anti-racist policies. Additionally, the report called for significant investments in public health infrastructure, environmental protection, and global health initiatives to mitigate the damage caused and prevent future crises (Woolhandler et al. 2021).

President Trump’s first, as well as his second term, were echoed by one slogan of making ‘America Great Again’. Several factors make the U.S. great; however, the principles of democracy, freedom, and human rights are foundational. The country’s democratic system is built on values like liberty, equality, and justice, deeply embedded in its political and social fabric (Khorram-Manesh 2023a). Table 2 shows the U.S. strengths and comparative advantages and potential repercussions of the U.S. leaving WHO and international collaboration.

Nevertheless, the Trump administration is currently engaged in an aggressive conflict with Harvard University, implementing federal funding cuts reportedly in the billions and issuing a proclamation banning new foreign students from entering the U.S. to attend the institution, citing national security and alleged non-compliance with White House demands. These actions risk severely damaging American academia by undermining research capacity, curtailing academic freedom, and deterring international talent, while simultaneously weakening global health efforts by disrupting critical research, training, and collaborative networks essential for addressing worldwide health challenges (Blue Sky Thinking 2025).

The immediate consequences of the U.S. withdrawal

The U.S. withdrawal from the WHO is expected to have significant consequences, potentially weakening global health security and efforts to combat infectious diseases (World Health Organization (2022); World Health Organization (2024c)). The loss of U.S. financial support will create funding gaps, affecting the WHO’s ability to execute its programs and initiatives. The U.S. withdrawal of financial support from the WHO, particularly regarding assessed contributions, is only part of the concern. A potentially more severe consequence for low- and middle-income countries would be the U.S. scaling back or ending its funding for crucial global health initiatives like the Global Fund and Gavi. The WHO’s financial stability could be significantly jeopardized by the Trump administration’s recent threat to revoke the Gates Foundation’s tax-exempt status, as the Foundation is one of its largest contributors. Should this threat extend to other philanthropic organizations and charities, the repercussions for global health funding would be even more severe.

Furthermore, the U.S. has historically strengthened the WHO’s technical capacity for emergency response through the deployment of experts, including those from the CDC. The WHO’s global network for disease surveillance and response will be weakened. This could hinder the organization’s ability to detect and respond to health emergencies. Regions that depend on WHO support, such as Africa, may face significant challenges. The Africa Center for Disease Control has already expressed concerns about the pressure this withdrawal will put on health initiatives in the continent (Nyabiage 2025). The U.S.‘s role in shaping global health policies and priorities has been crucial. Its withdrawal may lead to a leadership vacuum, affecting international cooperation and coordination in addressing health crises (World Health Organization (2024a); McCormick Hibbert (2025); Liu et al. 2024).

The long-term implications of the U.S. withdrawal

The long-term implications of the U.S. withdrawal from the WHO could be profound. One of the most significant concerns is the potential impact on global health security (World Health Organization (2025c)). The WHO’s role in coordinating international responses to health emergencies, such as pandemics, and providing guidance and support to countries in managing public health threats is critical. Without U.S. involvement, the effectiveness of these efforts could be compromised (World Health Organization (2024a); McCormick Hibbert (2025); Hamzelou 2025; Park 2025).

Furthermore, the withdrawal could undermine progress in combating diseases like HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis, which have seen considerable advancements due to WHO-led initiatives (World Health Organization (2024a); McCormick Hibbert (2025); WHO 2022; WHO 2024c; Nyabiage 2025). These initiatives reflect WHO’s commitment to addressing critical health challenges and improving health outcomes worldwide and include the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), which aims to eradicate polio worldwide through vaccination and surveillance efforts (Aylward and Tangermann 2011); Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator that focuses on accelerating the development, production, and equitable access to COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines (Moon et al. 2022); The Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), aiming to strengthen global capacities to prevent, detect, and respond to infectious disease threats (Hinjoy et al. 2023); The Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative which focuses on eliminating cervical cancer as a public health problem through vaccination, screening, and treatment (Singh et al. 2023); and Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All (SDG3 GAP), which aims to accelerate progress towards the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by enhancing collaboration among global health organizations (Linnerud et al. 2021; Khorram-Manesh 2023b). The loss of U.S. funding and support may result in setbacks for these programs, potentially leading to increased morbidity and mortality rates in affected regions.

Moreover, A future pandemic necessitating expedited vaccine authorization could be complicated by the U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization, potentially impeding American access to vaccines approved under the WHO’s Emergency Use Listing procedure and delaying their deployment. This vulnerability is compounded by any efforts by the administration to diminish the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s capacity to evaluate and approve novel vaccines through reductions in staffing or operational capabilities.

Impact on U.S. Public Health

The U.S. withdrawal from the WHO could have significant domestic public health implications. The WHO provides vital data, research, and guidelines that shape U.S. public health policies. Without this information, the U.S. may struggle to address health threats and maintain standards (McCormick Hibbert (2025); Larson 2022; Hamzelou 2025; Park 2025; Kritz 2025; Shattuck 2020; Burkle et al. 2021).

The WHO’s role in global disease surveillance and early warning systems is essential. Without participation, the U.S. may experience delays in receiving critical information about emerging health threats. The WHO also coordinates international responses to pandemics and health emergencies. The U.S. withdrawal could hinder its ability to respond effectively to future pandemics, potentially leading to higher infection rates and mortality (Ott 2025; McCormick Hibbert (2025); Larson 2022; Hamzelou 2025; Park 2025; Kritz 2025; Shattuck 2020; Burkle et al. 2021).

Many U.S.-funded global health programs, such as those targeting HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, rely on WHO coordination. The withdrawal may disrupt these programs, affecting both global and domestic health outcomes. The U.S. benefits from the WHO’s expertise in vaccine development, health guidelines, and research. Losing this partnership could slow progress in addressing public health challenges. Vulnerable populations in the U.S. may be disproportionately affected, as reduced international cooperation can exacerbate health disparities and limit access to essential health services (Hamzelou 2025; Park 2025; Kritz 2025; Shattuck 2020). Additionally, the withdrawal could strain relationships with other countries and international organizations, potentially isolating the U.S. in the global health arena. This isolation could hinder collaborative efforts to address transnational health issues, such as infectious disease outbreaks and antimicrobial resistance (Gearan 2020). The overall impact will make the U.S. weaker (Shattuck 2020).

The benefits for the U.S

While the concerns regarding the U.S. withdrawal from the WHO are substantial, some argue that this decision could yield certain benefits, including broader strategic and geopolitical ramifications (McCormick Hibbert (2025); Hamzelou 2025; Park 2025; Maxmen 2025). One of the primary advantages is financial: the significant funds previously allocated to WHO contributions could now be redirected towards domestic health initiatives, potentially strengthening the U.S. healthcare system and ensuring more targeted investments in national public health priorities. This financial reallocation could support disease prevention programs, medical research, and infrastructure improvements, addressing specific domestic health needs with greater flexibility. Moreover, the repurposed funding could enhance preparedness for future public health emergencies, allowing for quicker mobilization of resources in times of crisis (McCormick Hibbert (2025); Hamzelou 2025; Park 2025; Maxmen 2025).

Additionally, proponents of the withdrawal argue that leaving the WHO grants the U.S. greater autonomy in defining and implementing its health policies. Freed from the necessity of aligning with international guidelines that may not always reflect its priorities, the U.S. could adopt a more independent approach to tackling public health challenges. This shift could allow for more rapid responses to emerging threats and the ability to structure health interventions based on national assessments rather than global frameworks. Some also suggest that the withdrawal may open avenues for the U.S. to engage in direct bilateral health partnerships, facilitating more targeted and efficient collaboration on key global health issues. Furthermore, this approach could foster a competitive model where the U.S. independently sets health policy benchmarks that other nations may seek to follow, reinforcing its role as a global leader in health innovation and medical research (McCormick Hibbert (2025); Hamzelou 2025; Park 2025; Maxmen 2025).

This strategic autonomy may however face several challenges. Van den Abeele’s (2021) working paper, “Towards a New Paradigm in Open Strategic Autonomy,” explores the evolving concept of strategic autonomy within the European Union (EU). Originally linked to security and defense, strategic autonomy now encompasses broader economic and industrial dimensions. The paper discusses the EU’s dependence on major powers like the United States, China, and Russia, and examines the political rise of strategic autonomy in the European context. It highlights the challenges and opportunities for the EU to achieve strategic autonomy while balancing openness and competitiveness (Van den Abeele 2021).

Weighing risk vs benefits

While these perspectives highlight potential benefits, they remain subject to considerable debate, given the broader consequences of disengagement from the WHO. Critics argue that the potential benefits of a withdrawal must be weighed against the risks of diminished cooperation in global health crises, particularly in areas where the WHO plays a crucial role, such as pandemic preparedness, disease surveillance, and coordinated emergency responses. They contend that withdrawing could limit the U.S.‘s ability to influence global health standards and weaken international collaboration, ultimately affecting both domestic and global health outcomes. limited access to WHO research networks, and possible isolation from coordinated international response efforts. More importantly, this move raises critical questions about the long-term implications for global health security and the extent to which the U.S. can maintain leadership in international health policy outside established multilateral frameworks (McCormick Hibbert (2025); Gostin 2021; Nyabiage 2025; Liu et al. 2024; Berttozzi 2025; Maxmen 2025; Kritz 2025; Shattuck 2020).

Starting his second term, President Trump’s decision for the United States to withdraw from the WHO was a significant and controversial move, with far-reaching positive and negative implications domestically and globally (The White House 2025). Nevertheless, the disadvantages of this decision are profound. The WHO, heavily reliant on U.S. funding, faces a significant financial shortfall. This resource reduction threatens to weaken the organization’s ability to respond effectively to global health crises (World Health Organization (2024a); McCormick Hibbert (2025); Nyabiage 2025; Liu et al. 2024). The potential for slower responses to pandemics and other health emergencies poses a risk not only to global health security but also to the health and safety of Americans, as infectious diseases know no borders (Khorram-Manesh et al. 2024; Khorram-Manesh et al. 2022). The WHO’s role in managing global health crises, which can drive migration is crucial (Baggaley et al. 2023). Without U.S. support, the WHO’s ability to respond to health emergencies may be weakened, potentially leading to increased migration from affected regions. The WHO provides essential health services to refugees and migrants. U.S. withdrawal could reduce funding and support for these programs, impacting the health and well-being of displaced populations.

Globalization brings international collaboration and economic impact (Khorram-Manesh 2023b). The WHO facilitates global cooperation on health issues. U.S. withdrawal could hinder international collaboration, affect global health initiatives and potentially lead to fragmented responses to health crises. Global health is closely tied to economic stability (Khorram-Manesh 2023b; Khorram-Manesh et al. 2024). A weakened WHO could lead to more frequent and severe health crises, disrupting global trade and financial activities.

Moreover, the U.S.‘s withdrawal means a loss of leadership in global health. The country’s influence in shaping international health policy and standards is diminished, potentially leading to less favorable outcomes for global health initiatives (Gostin 2021; Eichensehr 2021; Liu et al. 2024). Concurrent with this, China has proactively expanded its “health diplomacy” through initiatives such as the Belt and Road, potentially positioning itself as a preeminent force in shaping global health governance (Minghui R. 2018) This reduced U.S. engagement could also lead to the fragmentation of international health efforts, resulting in divergent national strategies and a general weakening of global coordination.

The loss of the U.S. leadership and influence extends to the realm of research and collaboration. U.S. researchers and institutions that benefit from partnerships with the WHO will face reduced opportunities for international collaboration and access to valuable global health data (Hamzelou 2025; Menasce Horowitz (2019); Bertozzi (2024); Kritz 2025). The decision also carries significant public health risks. Without the coordination and support of the WHO, the U.S. might find itself less prepared for global health threats. This lack of preparedness could make Americans more vulnerable to infectious diseases and other health risks that require international cooperation to manage effectively (Kritz 2025; Shattuck 2020; Khorram-Manesh et al. 2024).

Finally, the WHO addresses the health impacts of climate change, such as heat-related illnesses and vector-borne diseases. U.S. withdrawal could reduce the effectiveness of these efforts, exacerbating health issues related to climate change. The U.S. has been a key player in global health and climate initiatives. Its withdrawal from the WHO, and its exit from the Paris Climate Agreement, signals a retreat from international leadership on these critical issues, potentially slowing global progress on climate change mitigation (Goniewicz et al. 2024).

Despite all the positive impacts and activities of the WHO, aligning with President Trump, scientists, and public health experts emphasize the need to reform the WHO. They call for enhanced transparency and accountability to build trust and improve effectiveness. Stable and increased funding is crucial for the WHO to respond effectively to global health crises and maintain readiness. Experts also suggest strengthening the WHO’s ability to detect and respond to health threats swiftly, requiring better coordination and quicker action. Collaboration with member states is essential for a unified global health response, and prioritizing equity and inclusivity is vital to addressing health disparities and supporting vulnerable populations. These reforms aim to bolster the WHO’s role in global health governance and enhance its capacity to tackle future health challenges (Sridhar and Gostin 2011; Burkle 2015).

Responding to these claims, in a recent move, the Director-General of the WHO has enacted a major organizational overhaul, drastically reducing the number of senior leaders and consolidating departments. This “reset” aims to boost efficiency, cut costs amidst significant budget shortfalls, and improve the agency’s public image, post-COVID-19, notably by excluding US and Chinese nationals from the core leadership to enhance impartiality and promoting greater diversity. However, this significant shake-up carries risks, primarily the loss of invaluable institutional knowledge and experience with the departure of long-serving experts, potentially disrupting critical global health initiatives. While promising greater agility, and renewed trust, the changes also pose a learning curve for new leadership and could cause internal uncertainty, with the ultimate effectiveness of the reorganization remaining to be seen. (Health Policy Watch 2025).

In another move, On May 20, 2025, the World Health Assembly formally adopted by consensus the world’s first Pandemic Agreement, a landmark decision following over three years of intensive negotiations. This historic accord aims to strengthen global collaboration for a more equitable and effective response to future pandemics, learning from the devastating impacts of COVID-19. Key components of the Agreement include a commitment to developing a Pathogen Access and Benefits Sharing (PABS) system to ensure equitable access to health products, the creation of a new financial mechanism for pandemic preparedness and response, and a Global Supply Chain and Logistics Network. Member States also approved a significant 20% increase in assessed contributions (membership fees) and a US$ 4.2 billion base program budget for 2026–2027, emphasizing health equity and resilient health systems, and reaffirming the critical role of multilateralism in global health challenges. The agreement explicitly states it does not infringe on national sovereignty, addressing concerns about WHO overreach (World Health Organization (2025d)).

Despite the executive order, the withdrawal process requires a one-year notice period and fulfillment of financial obligations before it becomes final. This provides an opportunity for reconsideration and potential reversal of the decision. The WHO has expressed hope the U.S. will reconsider and engage in constructive dialogue to maintain the partnership (World Health Organization (2025a)). Meanwhile, in Washington D.C., the Trump administration shut down USAID, citing corruption and inefficiency. Critics argued that USAID was vital for global aid and stability. Despite the backlash, the closure proceeded, leaving many projects and employees in limbo. The debate over the decision’s impact continues (Seddon 2025). Nevertheless, President Trump’s decision might be a political maneuver based on his extensive business background. During his first term, he approached global issues with a mindset shaped by his experience in the private sector. He emphasized negotiation, deal-making, and a results-oriented approach. President Trump’s administration focused on leveraging economic power to address global issues, often prioritizing American interests and seeking to renegotiate trade agreements to benefit the U.S. His business mindset also influenced his handling of international conflicts and alliances. He aimed to manage these relationships like business partnerships, emphasizing mutual benefits and accountability. This approach was evident in his dealings with countries like China, where he sought to address trade imbalances, and in his efforts to broker peace agreements in the Middle East (Larson 2022; Haar and Krebs 2021; Krasner 2021). This behavioral approach has a long-term impact on democracy, allowing the survival of autocratic nations. “If democracy fails in the U.S., it fails everywhere.” (Khorram-Manesh 2023a).

Strenghts and limitations of this study

In contrast to the prevailing narrative that largely details the adverse effects of the U.S.’ withdrawal from the WHO, this scholarly endeavor presents a systematic and exhaustive narrative review of its wider ramifications. Diverging from opinion-driven commentaries, this paper endeavors to impartially evaluate both the potential detriments and advantages of said withdrawal, a dimension frequently absent from contemporary discourse. Through this approach, we seek to proffer a balanced and empirically grounded perspective, thereby accentuating the inherent interconnectedness of global health and the indispensable function of international collaboration in safeguarding the health and welfare of all sovereign states.

While combining a systematic narrative review with AR has limitations like potential bias in narrative reviews and generalizability issues in AR, its pros significantly outweigh them for this study. The systematic review provides a rigorous, evidence-based foundation, identifying knowledge gaps and informing the AR, which then leverages this by engaging stakeholders to develop and test practical, context-specific solutions in real-time, offering actionable insights for global health policy and strengthening international collaboration, a uniquely impactful approach to understanding the withdrawal’s complex repercussions (Toledano, Anderson (2020); Heikkinen et al., (2007); Clandinin and Connelly 2000).

Conclusion

President Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the WHO has profound and extensive consequences. The immediate financial and operational impacts on the WHO, and the potential long-term implications for global health security, and U.S. public health underscore the critical importance of international collaboration in addressing health challenges. As the world continues to confront complex and interconnected health threats, the role of the WHO and the participation of major contributors like the U.S. are essential to ensuring a safer and healthier future for all. While the U.S.‘s withdrawal from the WHO offers potential financial and policy benefits, the disadvantages, particularly considering global health impact and reduced influence are significant, affecting migration patterns, global health collaboration, and efforts to combat climate change. These impacts highlight the interconnected nature of global health and the importance of international cooperation in safeguarding the health and well-being of all nations.

Data availability

All data obtained/generated has been provided and included in the manuscript.

References

American Government (2025) Democratic Values – Liberty, Equality, Justice. Available from: https://www.ushistory.org/gov/1d.asp

Atkinson RD (2020) Understanding the US National Innovation System. Available from: https://itif.org/publications/2020/11/02/understanding-us-national-innovation-system-2020/

Aylward B, Tangermann R (2011) The global polio eradication initiative: lessons learned and prospects for success. Vaccine 29:D80–D85

Baggaley RF, Nazareth J, Divall P, Pan D, Martin CA, Volik M et al. (2023) National policies for delivering tuberculosis, HIV and hepatitis B and C virus infection services for refugees and migrants among Member States of the WHO European Region. J Travel Med 30(1):taac136

Bertozzi S (2024) US withdrawal from WHO could bring tragedy at home and abroad. Available from: https://publichealth.berkeley.edu/news-media/opinion/withdrawal-from-who-could-bring-tragedy

Blue Sky Thinking (2025) Not Making America Great – What Trump Administration’s ban on Harvard’s international students means For the U.S. Available from: https://bluesky-thinking.com/not-making-america-great-what-trump-administrations-ban-on-harvards-international-students-means-for-the-u-s/#:~:text=The%20broader%20message%20sent%20by,for%20higher%20education%2C%20and%20persuade

Borzyskowski and Vabulas. Public support for withdrawal from international organizations: Experimental evidence from the US. Rev Int Org. 2024

Burkle Jr FM (2015) Global health security demands a strong international health regulations treaty and leadership from a highly resourced World Health Organization. Disaster Med public health preparedness 9(5):568–580

Burkle FM, Bradt DA, Ryan BJ (2021) Global public health database support to population-based management of pandemics and global public health crises, part I: The concept. Prehosp Disaster Med 36(1):95–104

Chen YJ, Cohen JA (2020) Why does the WHO exclude Taiwan. Available from: https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/why-does-who-exclude-taiwan

Clandinin DJ, Connelly FM (2000) Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass

Collins M (2020) The WHO and China: Dereliction of Duty. Available from: https://www.cfr.org/blog/who-and-china-dereliction-duty

Coudaha R, Hu D (2016) American higher education becomes more attractive to international students and global talent. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/rahuldi/2016/03/19/24month-stem-opt-extension-universities-colleges-students/

Cullinan K (2025) If the US pulls out of WHO, will other member states step up? Available from: https://healthpolicy-watch.news/if-us-pulls-out-of-who-will-other-member-states-step-up/

Dijkstra and Ghassim (2024) Are authoritative international organizations challenged more? A recurrent event analysis of member state criticisms and withdrawals. Rev Int Org 2024

Education USA (2025) The US Educational System. Available from: https://educationusa.state.gov/experience-studying-usa/us-educational-system

Eichensehr KE (2021) Biden Administration Reengages with International Institutions and Agreements Am J Int Law

Gearan A (2020) Trump announces cutoff of new funding for the World Health Organization over pandemic response. The Washington Post

Goniewicz K, Burkle FM, Khorram-Manesh A (2025) Transforming global public health: climate collaboration, political challenges, and systemic change. J Infect Public Health 18(1):102615

Gostin (2021) US withdrawal from WHO is unlawful and threatens global and US health and security The Lancet

Grant M, Booth A (2009) A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 26(2):91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Haar RN, Krebs LF (2021) The failure of foreign policy entrepreneurs in the Trump administration. Politics Policy 49(2):446–478

Hamzelou J (2025) The US withdrawal from the WHO will hurt us all. MIT Technol Rev 2025. Available from: https://www.technologyreview.com/2025/01/24/1110480/us-withdrawal-from-who-will-hurt-us-all/

Health Policy Watch (2025) WHO Director General skakes up agency with brand new leadership team. Available from: https://healthpolicy-watch.news/who-director-general-shakes-up-agency-with-brand-new-leadership-team/

Heikkinen HLT, Huttunen L, Syrjälä L (2007) Action research as narrative: five principles for validation. Edu Act Res 15(2):227–241

Hinjoy S, Tsukayama R, Sriwongsa J, Kingnate D, Damrongwatanapokin S, Masunglong W et al. (2023) Working beyond health: roles of global health security agenda, experiences of Thailand’s chairmanship amidst of the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob Secur Health Sci Policy 8(1):2213752

Ivankova NV, Johnson SL Designing integrated mixed methods action research studies. In: The Routledge Handbook for Advancing Integration in Mixed Methods Research. Routledge; 2022. p. 158-73

Khorram-Manesh A (2023a) If democracy fails in the United States, it fails everywhere. WMHP 15(4):319–323

Khorram-Manesh A (2023b) Global transition, global risks, and the UN’s sustainable development goals–A call for peace, justice, and political stability. Glob Transit 5:90–97

Khorram-Manesh A, Carlström E, Hertelendy AJ, Goniewicz K, Casady CB, Burkle Jr FM (2022) Does the prosperity of a country play a role in COVID-19 outcomes? Disaster Med Public Health Prep 16(1):177–186

Khorram-Manesh A, Goniewicz K, Burkle JrFM (2024) Unleashing the global potential of public health: a framework for future pandemic response. J Infect Public Health 17(1):82–95

Krasner MA (2021) Donald Trump: Dividing America through new-culture speech. In: When politicians talk: The cultural dynamics of public speaking. 257–274

Kritz F (2025) What leaving the WHO means for the US public health. Available from: https://www.msn.com/en-us/health/other/what-leaving-the-who-means-for-us-public-health/ar-AA1xGbG8

Larson M (2022) The World Health Organization, the Trump Administration, American Public Opinion, and China: A Principal-Agent Problem [Master’s thesis]. Loyola University Chicago

Linnerud K, Holden E, Simonsen M (2021) Closing the sustainable development gap: A global study of goal interactions. Sustain Dev 29(4):738–753

Liu Y, Hall BJ, Ren M (2024) How the U.S. presidential election impacts global health: governance, funding, and beyond. Glob Health Res Policy 9:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-024-00391-w

Maxmen A (2025) What a US exit from the WHO means for global health. Available from: https://www.politifact.com/article/2025/jan/27/what-a-us-exit-from-the-who-means-for-global-healt/

Mazumdaru S (2020) What influence does China have over the WHO? Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/what-influence-does-china-have-over-the-who/a-53161220

McCormick Hibbert C (2025) What the US exit from the WHO means for the global health and pandemic preparedness. Available from: https://news.northeastern.edu/2025/01/23/us-withdrawn-from-who/

Menasce Horowitz J 2019. Americans see advantages and challenges in the country’s growing racial and ethnic diversity. Pew Res Cent. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/05/08/americans-see-advantages-and-challenges-in-countrys-growing-racial-and-ethnic-diversity/

Minghui R (2018) Global health and the Belt and Road Initiative. Glob Health J 2(4):1−4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2414-6447(19)30176-9

Moon S, Armstrong J, Hutler B, Upshur R, Katz R, Atuire C et al. (2022) Governing the access to COVID-19 tools accelerator: towards greater participation, transparency, and accountability. Lancet 399(10323):487–494

Nash F How powerful is the US? A deep dive into the economic, cultural, and military power of the World’s Superpower. 2024. Available from: https://scientificorigin.com/how-powerful-is-the-united-states-a-deep-dive-into-the-economic-cultural-and-military-power-of-the-worlds-superpower

Nyabiage J (2025) Africa braces as Trump’s WHO withdrawal, aid freeze to ‘gut global public health’. South China Morning Post. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3296185/africa-braces-trumps-who-withdrawal-aid-freeze-set-gut-global-public-health

Ott H World leaders react as President Trump makes big moves on Day 1 of his second term. 2025. Available from: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-inauguration-world-reaction-paris-climate-who-withdrawal-day-1/-

Parekh A (2023) Optimizing US global health funding. JAMA 329(17):1447–1448

Park A (2025) What leaving the WHO means for the US and the world? Time. Available from: https://time.com/7208937/us-world-health-organization-trump-withdrawal/

Seddon S (2025) What is USAID and why is Trump poised to close it down? Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/clyezjwnx5ko

Senate Democrats (2025) Our Values. Available from: https://www.democrats.senate.gov/about-senate-dems/our-values

Shattuck TJ (2020) On the Sidelines: Trump Gives Up the WHO—and Makes America Weaker. Available from: https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/06/on-the-sidelines-trump-gives-up-the-who-and-makes-america-weaker/

Singh D, Vignat J, Lorenzoni V, Eslahi M, Ginsburg O, Lauby-Secretan B et al. (2023) Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: a baseline analysis of the WHO Global Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. Lancet Glob Health 11(2):e197–e206

Sridhar D, Gostin LO (2011) Reforming the World Health Organization. JAMA 305(15):1585–1586

The White House. Presidential actions. Withdrawing the United States from the World Health Organization. 2025. Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/withdrawing-the-united-states-from-the-worldhealth-organization/

Toledano N, Anderson AR (2020) Theoretical reflections on narrative in action research. Act Res 18(3):302–318

USAHello (2022) Understanding diversity in the United States. Available from: https://usahello.org/life-in-usa/culture/diversity/

Van den Abeele E Towards a new paradigm in open strategic autonomy? (No. 2021.03). Working Paper. 2021

Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Ahmed S, Bailey Z, Bassett MT, Bird M et al. (2021) Public policy and health in the Trump era. Lancet 397(10275):705–753

World Health Organization (2022) Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022-2030

World Health Organization (2024a) United States of America: Partner in global health. A global force for health. Available from: https://www.who.int/about/funding/contributors/usa

World Health Organization (2024b) How WHO is funded. Available from: https://www.who.int/about/funding

World Health Organization. (2024c). Working for a brighter, healthier future: how WHO improves health and promotes well-being for the world’s adolescents

World Health Organization. WHO comments on the United States’ announcement of intent to withdraw. 2025a. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/21-01-2025-who-comments-on-united-states--announcement-of-intent-to-withdraw

World Health Organization (2025b) Principle: Credible and trusted. Available from: https://www.who.int/about/communications/credible-and-trusted

World Health Organization (2025c) Health Security. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-security#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization (2025d) World Health Assembly adopts historic Pandemic Agreement to make the world more equitable and safer from future pandemics 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-05-2025-world-health-assembly-adopts-historic-pandemic-agreement-to-make-the-world-more-equitable-and-safer-from-future-pandemics

World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) (2024) The US remains the World’s most powerful travel and tourism market. Available from: https://wttc.org/news-article/us-remains-the-worlds-most-powerful-travel-and-tourism-market

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK conceptualized the study; AK compiled the data; AK and KG reviewed all studies and FB approved the result: AK drafted the manuscript; KG and FB read and edited the manuscript; all authors approved the final version and its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

AI disclosure

AI has not been used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Ethical approval

This article is a review of previously published literature and does not involve any new studies with human participants or animals performed by the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals by the authors, and no informed consent was required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khorram-Manesh, A., Burkle, F.M. & Goniewicz, K. Repercussions of a U.S. withdrawal from WHO will severely impact future global goals and performance. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1300 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05657-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05657-3