Abstract

This study examines the metaphorical insights into a multi-modal writing intervention among EFL learners in an English Language Teaching program, using Conceptual Metaphor Theory from cultural linguistics as its theoretical framework. Adopting intervention-based explanatory mixed method design, the study aims to explain the multimodal writing intervention aimed at improving writing performance in descriptive, example, narrative, process, and opinion writing modes on the basis of the metaphors EFL learners provided. After intervention, 68 participants completed metaphor prompts designed to encourage imaginative engagement and reflection. For quantitative data, paired sample t test was followed, and the analysis yielded statistically significant improvements in students’ writing performance as a result of multi-modal writing intervention. On the other hand, qualitative data were analyzed using MAXQDA, uncovering a variety of metaphorical phrases that captured students’ cognitive and emotional relationships to writing. Key themes included personal connections, challenges, and aspirations tied to specific writing modes. Results demonstrated a notable shift in metaphor use, reflecting a transition toward more positive and constructive representations of their writing experiences. This evolution highlighted both enhanced technical skills and increased confidence because of the intervention. The findings suggest that addressing cognitive and emotional barriers, as reflected in metaphorical expressions, enables learners to achieve higher-quality writing. Overall, the study underscores the effectiveness of multi-modal writing interventions in fostering cognitive, psychological, and performance-based growth in EFL writing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of metaphors within the realm of cultural linguistics is a compelling avenue for understanding the nuanced conceptualizations of students’ writing experiences in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) contexts. Writing in a foreign language demands a complex interplay of cognitive and linguistic skills, as articulated by Nunan (1999), and psychosocial dimensions that are often deeply rooted in cultural contexts. By employing metaphors, which are inherently tied to cultural conceptualizations, we can uncover the cognitive and emotional landscapes of EFL learners’ writing processes. This exploration is particularly vital given the global significance of English and its role as a medium in neoliberal educational environments.

As a theoretical framework, cultural linguistics provides a robust guidance for this investigation, positing that language and culture are intertwined rather than independent entities (Sharifian, 2017; Polzenhagen & Wolf, 2007; Wolf & Polzenhagen, 2009). Cultural Linguistics is an interdisciplinary field that examines the dynamic interplay between language and culture, positing that language is a primary medium through which cultural meanings are constructed, shared, and negotiated (Lu, 2017). It is grounded in anthropological traditions, emphasizing that culture comprises an intersubjectively shared and often implicit matrix of meanings that structures individuals’ perceptions of themselves and the world around them (Reif & Polzenhagen, 2023). Specifically, from the perspective of Cultural Linguistics, culture is not merely an external influence on linguistic studies; rather, it is an essential component of those studies (Wolf & Polzenhagen, 2009, p. 19). Cultural conceptualizations can be expressed through various forms of language, including metaphors, metonymies, and literal language (Polzenhagen & Wolf, 2007). The manifestation of these forms in discourse related to specific subjects can offer valuable insights into the cultural models that are collectively held within a group (Polzenhagen & Dirven, 2008). The metaphors students utilize to describe their writing experiences may reveal underlying cultural models and beliefs that influence their perceptions and attitudes toward language learning. By examining these metaphors, we not only gain insight into individual cognitive processes, but we can also reflect on broader cultural narratives that shape language use and education practices.

Furthermore, the specific focus on EFL within distinct cultural contexts, particularly Turkiye, allows for an analysis of both shared global conceptualizations and their local inflections (Watts, 2011). In this regard, the study offers a novel contribution to EFL contexts by demonstrating the effectiveness of multi-modal interventions in enhancing writing skills and fostering learner confidence. It highlights the role of metaphor analysis in understanding the cognitive and emotional landscapes of students, enabling educators to tailor their teaching strategies more effectively. Furthermore, the emphasis on culturally responsive teaching practices addresses the unique cultural narratives that shape learners’ experiences, promoting a more holistic approach to language instruction. Ultimately, the insights gained from this research provide valuable guidance for creating supportive and engaging learning environments that consider both linguistic and cultural dimensions. As students navigate the challenges of writing in English, the metaphoric language they employ can serve as a lens through which we can understand their experiences, struggles, and successes. Accordingly, this research aims to illuminate the writing experiences of EFL learners and to inform pedagogical strategies that are attuned to their cultural and conceptual frameworks. Ultimately, the goal is to enhance the effectiveness and receptiveness of educational interventions—particularly those that are multi-modal—in diverse contexts. In addressing the research questions of this study, we aim to bridge the gap between metaphorical language and the lived experiences of EFL students, contributing to a richer understanding of the writing process in the context of cultural linguistics.

Literature review

Historical background and impact of multi-modal intervention in EFL writing

Writing intervention study needs to be multi-modal based on the 21st-century literacy landscape. According to the context, 21st-century literacy is no longer located exclusively in language or mono-cultural scripts; instead, it traverses a myriad of relations between different forms of communication, including visual, gestural, spatial, and linguistic semiotic resources (Cope, Kalantzis (2021); Cope & Kalantzis, 2009, 2015; New London Group, 1996). This change requires educators to rethink and redesign pedagogical approaches so that they can equip students with the skills necessary to utilize this increasingly complex, multimodal communications space.

The recognition of social diversity and the particular need for inclusive pedagogies acknowledging multicultural and transcultural classrooms is one of the most important reasons for multi-modal-based writing intervention (de Souza, 2017; Mizusawa & Kiss, 2020; Morita-Mullaney, 2021; Palsa & Mertala, 2019; van Leeuwen, 2017). It often omits other modes of meaning-making that are vital to students’ holistic understanding of their world and expression throughout different contexts (Kress & Selander, 2012; New London Group, 1996). This involves moving towards a pedagogical approach that is multimodal, which enables students to use their funds of knowledge, so that the curriculum draws on their lived experiences and identities in ways that connect meaningfully with them (New London Group, 1996).

Additionally, the prevalence of these forms in this increasingly multimodal digital world—from social media and websites to interactive presentations—calls for students to not simply make sense of them, but critically and creatively engage with them as well (Lim, Towndrow & Tan, 2021). The capacity to generate and analyze multimodal texts proficiently becomes an essential skill in both educational and occupational contexts, where employers are ever more in search of professionals who can communicate effectively across diverse modes and media (Jewitt & Kress, 2003; Kress, 2009; Lim, 2021; van Leeuwen, 2017). In this regard, research indicates that a multi-modal writing intervention equips students with essential, ongoing writing skills that align with educational syllabi and prepare them for future training or entry into a dynamic industry; moreover, this approach enhances students’ overall communication abilities, contributing to their positive professional growth (Archer, 2022; George, 2022; Hasbullah et al., 2023; Jeanjaroonsri, 2023; Jiang et al., 2022; Navila et al. 2023; Rahmanu & Molnár, 2024).

The need for a multi-modal-based writing intervention study is backed by the gap in pedagogical frameworks that allow students to explore and perform their ideas in their chosen meaning-making resources. All these benefits not only rebuild students' literacy experiences but also develop creativity, critical thinking, and communication skills in the 21st century. Multi-modal-based writing intervention is not just a creative teaching technique, but an essential approach to literacy instruction that helps prepare students for the complexities and expectations of an interconnected, multicultural, multimodal world.

Metaphors in EFL writing: insights into learner perspectives

While often regarded as mere literary devices, metaphors are framed as foundational components of communication and thought, facilitating the interpretation of complex ideas (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). The necessity of metaphorical constructs arises from the inherent difficulty in articulating abstract concepts, allowing individuals to relate one cognitive domain to another (Lakoff, 1993; Veliz & Véliz-Campos, 2022). In educational contexts, metaphors are particularly valuable as they provide insights into the beliefs and attitudes of both learners and educators. Encouraging students to create metaphors about their learning experiences fosters self-reflection and enhances personal growth (Levin & Wagner, 2006).

Significant research has been conducted in EFL contexts to examine how metaphors can elucidate the attitudes and conceptual frameworks of students and educators. Numerous scholars, such as Ahkemoğlu (2011), Akbari (2013), and Farrell (2016), have highlighted the potential of metaphorical analysis to reveal underlying beliefs and perceptions within language education, as evidenced by findings from Eren, Tekinarslan (2012), İnceçay (2015), Farías and Véliz (2016), Palinkašević (2021), and Bessette and Paris (2020).

Accordingly, the exploration of metaphors in understanding students’ attitudes towards English writing is not just an academic exercise; it serves as an essential pedagogical tool that can significantly enhance writing education. By employing metaphors such as drawing, journeys, and even nightmares, educators can uncover the complexities of students’ perceptions and experiences with writing. Previous studies have shown that students often articulate their struggles and progress through these vivid linguistic frameworks, which reflect their emotional landscapes and cognitive processes (Aydın & Baysan, 2018; Hamouda, 2018; Öztürk, 2022; Paulson & Armstrong, 2011; Pavesi, 2020; Phyo et al., 2023; Wan, 2014). For instance, metaphors like “toddler” emphasize the developmental effort required in writing, while negative metaphors, such as “nightmare,” highlight the common anxieties faced by learners. Importantly, as students progress through different writing modes, the decrease in negative metaphors indicates a shift toward greater understanding and confidence (Hamouda, 2018; Wan, 2014). Furthermore, interventions emphasizing metaphor usage have been demonstrated to foster critical thinking and promote positive changes in students’ beliefs about writing (Wan, 2014). Therefore, integrating metaphor analysis into writing instruction not only deepens students’ engagement with the writing process but also equips educators with valuable insights to tailor their teaching strategies, ultimately leading to more effective and enriching writing experiences.

Rationale

The rationale for investigating multi-modal interventions in the context of EFL instruction is closely tied to the transformation of communication practices in the digital era. As language consumption and production evolve, it becomes essential for educational methodologies to reflect these changes, particularly through the incorporation of diverse semiotic modes—visual, gestural, and spatial—alongside traditional language skills. This study emphasizes that modern literacy transcends mere language proficiency, necessitating multifaceted pedagogical approaches that prepare learners for dynamic communicative environments.

Through multi-modal writing strategies, the research claims that students can achieve heightened writing proficiency and deeper cognitive and emotional connections to their work. By implementing varied communication modes, educators can engage learners more wholly, fostering a rich interplay between their cultural contexts and emotional responses to language. Additionally, metaphors are highlighted as critical tools for revealing students’ cognitive frameworks and attitudes toward writing, allowing for more tailored instructional strategies.

The holistic approach adopted in this study, which integrates cultural linguistics and metaphor analysis, underscores the intertwined relationships among language, culture, and cognition. By embracing these elements, the rationale posits that multi-modal interventions can effectively address the complexities of modern literacy, making language education more competent, inclusive, and engaging for diverse learners in the EFL landscape. This calls for educators and policymakers to embrace such methodologies for enriching language instruction.

Methodology

Research design

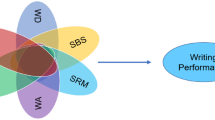

Based on fully integrated mixed-method paradigm, this study followed explanatory study to explain the multi-modal writing intervention through the metaphor analysis to reconstruct the spectrum of all metaphors, in EFL students’ reflective journals, to generate a “cognitive map” of the perception of the Multi Modal intervention for five different writing modes - descriptive, example, process, narrative, and opinion mode. In the process, the data integration based on the collation, association, or cross-case comparison of two different types of data is crucial (Fraenkel et al., 2012; Johnson & Christensen, 2020). In the context of this study, a fully integrated mixed method paradigm was adopted to provide a comprehensive exploration of the research problem, leveraging the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative approaches. In this regard, the complexity of educational phenomena, particularly in the realm of language education, requires a nuanced understanding that single-method studies may not fully capture. A mixed method paradigm allows for the triangulation of data, where qualitative insights from student reflections can validate and enrich quantitative findings from performance metrics. This complementary relationship fosters a more holistic interpretation of how students experience multi-modal writing interventions. Besides, employing an explanatory framework within the mixed methods design is particularly beneficial for elucidating the relationships underlying students’ perceptions of the intervention. By not only identifying performance through quantitative data but also seeking to understand the ‘why’ behind the performance through qualitative analysis, the study aims to provide richer, contextually grounded insights. This explanatory nature is crucial for uncovering the mechanisms influencing student engagement and understanding. Also, language learning and writing are inherently complex processes influenced by various cognitive, emotional, and social factors. A fully integrated mixed-method approach allows researchers to capture this complexity by examining both statistical trends and personal narratives. This methodological stance not only enhances the rigor of the current study but also contributes to a growing body of scholarship that supports multi-faceted research designs. The integration of qualitative and quantitative data also equips educators with a robust framework to inform instructional strategies. By understanding students’ perceptions alongside measurable outcomes, educators can make data-driven decisions that reflect the nuanced realities of their students’ experiences. This provides evidence of the practical implications of the research, showcasing how the results can inform pedagogy and improve student engagement in writing. In this regard, multi-modal framework provided the foundation to explore whether the writing intervention based on multi-modality would have an impact on the writing performance of university students in EFL contexts, while cultural linguistics and Lakoff and Johnson’s metaphor framework (1980) guided the study in terms of how and why multi-modal intervention should be effective through further explanation on the basis of cognitive and cultural scheme the students had regarding the process. Figure 1 illustrates how cultural linguistics, Lakoff and Johnson’s metaphor framework (1980), and multi-modality informed the design, data collection and analysis tools of the current study.

On this basis, this study employed a single-group pre-test-post-test design with a single group of prep-class students through the pre-test to assess the writing performances of students before intervention, followingly a multi-modal writing intervention, and then the post-test to assess the probable effect of the intervention (McMillan & Schumacher, 2014). Following the quantitative data as results of intervention, metaphor analysis, based on the reflective journals of students as qualitative data, would act as a framework for clarifying cognitive structures through linguistic models, thus enabling the recognition of both individual and collective patterns of thought and behavior of EFL students in intervention. (Carpenter, 2008). In this regard, the study firstly addressed the following research questions:

-

1.

Is there a significant difference in the pre-test and post-test performance scores of EFL students for each writing mode?

-

2.

What metaphors do EFL students use to describe their writing experiences for each writing mode in the multi-modal intervention?

Then, for the meta-inference as a result of data integration to explain the intervention on the basis of metaphorical conceptualizations of students, the following question will be discussed in detail:

In what ways do these metaphors inform their insights into the multi-modal intervention?

Participants

Sixty-eight (41 females and 37 males) university students enrolled in a bachelor's ELT program - prep class at a state university in Turkiye participated in both quantitative (intervention) and qualitative (metaphor) phases of the present study. Participants (Table 1) had an estimated intermediate (B.1.1 level - 8.6%) to higher-intermediate proficiency (B1.2 English level −91.4%), based on their writing scores. They were chosen due to their pivotal position in their academic progression with experiencing extensive writing intervention with 5 h session each week, and multi-cultural backgrounds they have. Besides, for prep-class students, the language labs with various modes including visual, gestural, spatial, and linguistic semiotic resources/ tools were used for writing instruction.

Data collection and analysis

Before the study, the ethical considerations were addressed through the application of two fundamental principles: confidentiality and anonymity. So, first of all, the approval from the university’s Ethics Committee was secured for the study. Then, participants were assured that all recordings and identifying information would be kept confidential. Informed consent forms were collected prior to their involvement in the intervention process, ensuring that participants understood their rights and the scope of the study. Also, to uphold the principle of anonymity, pseudonyms were assigned to all participants, effectively safeguarding their identities and ensuring that data could not be linked back to any individual. These measures were implemented to protect participant privacy and uphold the integrity of the research process.

The multi-modal intervention for this study was organized on the basis of the classes, during which the students engaged in tasks that utilize various modes, including sample texts, images, graphics, animation, audio, and video for each writing mode (descriptive, example, process, narrative, and opinion modes. Basically, the classes were planned to provide opportunities for processing information via listening, speaking, reading, writing, and visual representation, alongside avenues for demonstrating knowledge through oral discussions and videos. Before writing, the students were expected to present their arguments through text, images, and video, and engaged in class discussions both orally and online. Then, they produced their written products. After the 14-week intervention (approximately 2 or 3 week- for each paragraph mode), the participants were requested to develop a metaphor that encapsulated the mode they had explored by completing the prompt: “Writing in … writing mode is akin to… because ….”. After intervention, this prompt was reiterated, modified to align with the respective writing mode. In this process, the participants’ responses were gathered anonymously to ensure confidentiality.

Central to the study is the deployment of an analytic rubric (see Appendix) that evaluates key writing components, including content, organization, cohesion, accuracy, appropriateness of language conventions, and register (Weigle, 2002). This rubric was selected for its effectiveness in providing focused feedback and enhancing the reliability and validity of scoring among different raters (East & Young, 2007; Knoch, 2009; Weigle, 2002). The rating process involved a two-phase analysis wherein the products of the participants before and after intervention were scored by the two independent raters: one of the researchers and an experienced English writing instructor. They evaluated each writing mode separately before convening to discuss discrepancies in their assessments, ultimately arriving at a consensus on the final scores. This collaborative scoring approach enhances the robustness of the evaluation process. Then, the scores of pre-test and post-test were computed to IBMSPSS software. The quantitative data obtained from pre, and post-test paragraphs were analyzed with paired samples t test. This approach directly addresses the first research question by providing statistical data that can show the effects of the multi-modal writing intervention. The use of a scoring rubric to assess various writing components ensures that the evaluation of student performance before and after the intervention is systematic and reliable.

The metaphors were analyzed as conceptual domains using the framework established by Lakoff and Johnson (1980). This study focused on writing as conceptual domain within a particular writing mode. The analysis employed MAXQDA 2022 software, enabling a systematic approach for data organization and coding. The analysis process follows a structured six-stage approach based on Braun and Clarke’s framework (2006). Initially, metaphors were compiled as raw data through quantification, and preliminary impressions were documented on the basis of noted occurrences of multiple metaphors, utilizing pseudonyms for anonymity. Subsequently, related features across the data set were systematically identified and compiled according to its corresponding writing mode. Next, codes were generated through interpretive in-context coding, which enhances the understanding of qualitative and quantitative variables by considering the discourse used in the data (Creamer, 2018/2020, p. 108). A cognition-based map was then constructed to visually represent the relationship between the coded data. Finally, relevant citation examples were chosen to illustrate the metaphors, linking them to the research question and existing literature while employing qualitative discourse language for reporting. To ensure consistency and reliability in the categorization process, the dataset was analyzed iteratively by both researchers This method enabled researchers to accurately capture students’ perceptions of writing in various rhetorical contexts, ultimately uncovering the nuanced ways they articulated their experiences through metaphors. The researchers conducted this analysis independently and subsequently refined the metaphors through discussions regarding the differences observed. Then, the inter-coder reliability was checked through percentage agreement, and the absolute agreement level were close to 85% (Hartmann, 1977; Stemler, 2004). Thus, the metaphors as data source and the coding process, structured around the belief that language and thought are interconnected plays a crucial role in how the metaphors elucidate students’ cognitive engagement in writing (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980), directly addressed the second research question of the study. Utilizing metaphor analysis allowed the study to delve into the cognitive frameworks students use, which is crucial for understanding their writing processes.

In this process, the role of the researchers is characterized by an integrative approach that blends participant observation with active engagement in the students’ writing processes. Emphasizing the interpretive paradigm, the researchers not only observe but also actively interact with participants, facilitating a friendly and intimate learning environment that encourages the sharing of individual experiences. This engagement is critical in highlighting the socially constructed nature of reality, as the researchers seek to understand the meanings and knowledge that students construct within their specific sociocultural contexts. Besides, by maintaining an unbiased stance, the researchers ensure a balanced and reflective inquiry process. Ultimately, the researchers serve as a conduit for understanding and documenting the complex dynamics of the learning environment, fostering a participatory atmosphere that contributes to a deeper understanding of the students’ experiences and learning processes.

Findings

Research question 1- Is there a significant difference in the pre-test and post-test performance scores of EFL students for each writing mode?

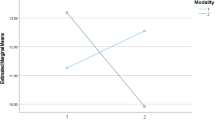

The results from the paired samples t-tests indicate significant improvements in EFL students’ paragraph performances across five writing modes after multi-modal intervention. Specifically, in descriptive paragraph writing, the pre-test mean score of x̄ = 8.23 was significantly lower than the post-test mean of x̄ = 11.59 (t = −8.23, p < 0.001). This significant improvement suggests that the multi-modal intervention effectively facilitated the students’ ability to describe objects, events, or ideas in a structured and coherent manner, enriching their descriptive language skills. Similarly, for example paragraph writing, the pre-test mean was x̄ = 8.71, which rose to x̄ = 12.00 in the post-test (t = −7.98, p < 0.001). This finding reflects the students’ enhanced capacity to articulate examples that underpin broader claims or arguments, indicating a greater ability to utilize illustrative language in their writing. The intervention was particularly effective in process paragraph writing, as evidenced by the pre-test mean of x̄ = 9.01 increasing to x̄ = 12.35 (t = −9.92, p < 0.001). This substantial improvement is indicative of the students’ heightened proficiency in outlining procedures or processes logically and clearly, suggesting that the intervention effectively supported the development of analytical and organizational skills critical for this writing modality. Narrative paragraph writing also showed improvement, with the pre-test mean of x̄ = 9.78 elevating to x̄ = 12.94 (t = −7.36, p < 0.001). The ability to construct narratives with a coherent structure and engaging content appears to have significantly improved, providing evidence that experiential learning facilitated through the multi-modal approach can effectively enhance narrative writing skills. Finally, in opinion paragraph writing, the students scored a mean of x̄ = 11.92 on the pre-test, which grew to x̄ = 13.75 on the post-test (t = −4.71, p < 0.001). Although this increase was the least robust compared to other writing categories, it remains statistically significant. This suggests that the participants are better equipped to articulate and justify their personal opinions, enhancing their persuasive writing capabilities. Collectively, these findings robustly support the assertion that a multi-modal intervention can lead to meaningful advancements in EFL students’ paragraph writing abilities across diverse formats. The consistent positive outcomes across all writing modes indicate not only the effectiveness of the intervention but also highlight the necessity for such approaches in EFL contexts.

Research question 2 - What metaphors do EFL students use to describe their writing experiences for each writing mode in multi-modal intervention?

In the following parts, based on the content analysis, the metaphors frequently used by the participants regarding the multi-modal intervention for each paragraph have been organized and presented as a word cloud, respectively.

The word cloud in Fig. 2 displays the most frequently used metaphors for descriptive paragraph writing. The participants wrote various metaphors representing their perceptions of the intervention for the descriptive paragraph mode. Painting and the painter were mostly emphasized metaphors. The following statement clearly shows that the participants use this metaphor inspired by the nature of the descriptive paragraph: “Writing a descriptive paragraph resembles the painting a person or an object. And the writer of descriptive paragraph is a painter exhibiting the person or the object in detail” (P21). This metaphor suggests that the student perceives descriptive writing as an artistic process that requires careful observation, imagination, and vivid depiction—attributes central to both painting and descriptive writing. The comparison highlights the emphasis on detail, precision, and creativity. Similarly, another participant also regarded the descriptive paragraph writing as a painting: “A very harmonious painting with mixed colors because I need to write many different ideas in a descriptive paragraph in a short, meaningful and coherent way” (P48). This reflection goes beyond surface-level imagery and implies an awareness of structural harmony and coherence. The participant appears to value not only the inclusion of multiple ideas but also their integration into a unified and aesthetically pleasing whole—mirroring the compositional balance in painting. Likewise, the metaphors such as photo, lens, glasses, telling a dream/tale, story, and watching a movie further illuminate the participants’ conceptualizations. For example, comparing writing to watching a movie suggests a dynamic, scene-by-scene unfolding of imagery, while the use of glasses or lens points to the importance of focus and perspective in capturing details. These metaphors collectively reflect participants’ growing awareness of audience, detail, and visualization in descriptive writing, reinforcing the effectiveness of the intervention in reshaping their cognitive and emotional engagement with the mode. Moreover, several participants drew on sensory and emotional metaphors to represent the multi-modal nature of the descriptive paragraph. Metaphors such as gourmet, colorful houses, strong feelings, perfume, and candy jar emphasize how descriptive writing engages multiple senses beyond the visual. The following statement exemplifies this vivid sensory engagement as: “Gourmet. Because a successful descriptive paragraph provides the reader taste and feel everything when she reads” (P32). This metaphor implies that the participant sees descriptive writing as a richly layered experience -one that should evoke not just imagery but also taste, touch, and emotion. The use of gourmet suggests a high level of sophistication and intentional crafting of the paragraph, underscoring the participant’s recognition of sensory precision and reader-centered writing.

Besides, several participants also stated that writing a descriptive paragraph is like a jigsaw-puzzle referring to the importance of unity in a paragraph. One of them:

“It’s like a 1000 pieces-puzzle because you try to find harmony by bringing the right pieces together (coherence) and if you put the wrong pieces together, you’re off topic (not following brainstorming and outlining). Finally, you ruin the picture (missing the unity of paragraph)” (P18).

This rich metaphor demonstrates metacognitive awareness of the writing process -from brainstorming to outlining - and shows how disorganization can compromise the paragraph’s intended meaning. The mention of “ruin[ing] the picture” suggests an emotional investment in achieving unity and coherence. One of the similar metaphors with an emphasis on unity was the Russian dolls that imply a nested and interconnected structure, reinforcing the idea that each sentence or detail must fit logically within the paragraph. These metaphors show students’ emerging understanding of paragraph structure as a cohesive and hierarchical construct. While the majority of metaphors conveyed positive and creative associations, some highlighted challenges and emotional strain, reflecting the cognitive demands of descriptive writing. A few participants also perceived the relevant paragraph as a long journey that reflects the perception of time-consuming effort and emotional fatigue: “While writing the descriptive paragraph, I felt like I was on a long journey. It seemed like the journey would never end” (P44). This sense of prolonged struggle reveals the cognitive load and possible frustration encountered during the writing process. Other relevant metaphors that the participants associated with the difficulties they had experienced are incomplete dialog, keyboard with missing keys, nightmare, and indescribable feelings. These metaphors further underscore the participants’ difficulties, suggesting feelings of inadequacy, disorientation, and expressive limitations.

The findings from the analysis of metaphors articulated by the participants reveal a cohesive understanding of the intervention for the descriptive mode, emphasizing the critical role of vivid imagery and sensory details. The frequent use of metaphors such as painting, jigsaw puzzle, and Russian dolls underscores the necessity for unity and coherence in constructing effective descriptive paragraphs. Although some metaphors illustrate the challenges faced during the writing process, the predominant expressions indicate that the participants successfully comprehended the fundamental characteristics of descriptive writing as a result of the intervention. This insight not only reflects their cognitive engagement with the writing task but also highlights the potential for metaphor analysis to inform pedagogical strategies in enhancing students’ writing proficiency.

The participants employed a variety of metaphors to express their perceptions and experiences related to the multi-modal intervention process for the example paragraph writing mode (see Fig. 3). Among the most frequently used were cooking and tree-branch metaphors, which vividly illustrate how students conceptualize unity, structure, and progression in their writing. The metaphor of cooking was repeatedly used to emphasize the importance of combining compatible elements to create a meaningful and cohesive paragraph. One participant explained: “The example paragraph is like doing ‘cooking’ because it will be nice if we put compatible ingredients and flavors into the meal we cook. But, if we don’t, it won’t” (P5). Another participant extended this metaphor further, likening the process of paragraph development to the gradual construction of a dish. This reflection highlights the developmental nature of writing and how meaning and structure emerge through the strategic addition of examples:

“Cooking, because the meal doesn’t have any form when we start to cook but it forms and tastes delicious when putting the ingredients into. Likewise, the example paragraph hasn’t any form when starting to write. But it takes forms and meaning as we write examples” (P23).

They also frequently likened the trunk and branch to the structure and parts of the example paragraph. While some of the participants described the trunk itself as the writing topic and its branches as examples supporting the topic, others associated the trunk with the topic sentence. This metaphor demonstrates the student’s structural awareness, emphasizing the dependency of coherence on properly aligned supporting details. One of them:

“A tree and its branches. Topic sentence in an example paragraph is like a trunk. First of all, topic sentence as a trunk must be strong for its branches which are the supporting details including examples. But if we cut one of the branches or it is not well-structured, it won’t be a part of the tree. In other words, our paragraph will be deficient and unsuccessful if we don’t support the topic sentence with the correct examples” (P17).

Besides, another metaphor submitted with emphasis on unity was furniture. The participant expressed her perspective as: “It is like furniture in a home because a house has unity with furniture in it and the furniture makes home good” (P39). This metaphor reinforces the idea that examples are not ornamental but essential components that shape the overall structure and clarity of writing.

Similarly, the metaphors such as salad, teacher, Japanese plum, snowflake, and fractal in geometry are also ones associated with the necessity of giving examples to support the main idea as the key characteristic of the example writing mode. Moreover, the metaphors, including dressmaking and knitting, were represented as the ones describing the process of constructing an example paragraph. In both metaphors, there is an emphasis on the necessity of giving examples and their details, but dressmaking is particularly rich, as it addresses both the procedural and cognitive demands of writing, highlighting the necessity of both resources and knowledge to produce an effective text:

“I think it is like dressmaking. To sew a dress, we need fabric, thread, needle, sewing machine. It isn’t easy to sew clothe without one of these. Moreover, we need to have knowledge to do it as well as sufficient materials such as fabric, thread etc. The example paragraph is something like that. We must have sufficient content knowledge about the topic that we write so that we can present enough examples as supporting details” (P36).

Conversely, some participants expressed their struggles with the example paragraph mode through more negative metaphors. These include walking blindingly, hose, and jigsaw puzzle, all pointing to disorientation, pressure, and perceived incompleteness. One participant, reflecting on teacher feedback received, noted: “Like a jigsaw-puzzle. Actually, it is like a jigsaw puzzle with missing piece because I had also some drawbacks in my example paragraph” (P8). Another relevant metaphor that one of the participants associated with the difficulties he had experienced is hose that indicates a sense of being overwhelmed and constrained by the expectations or demands of example mode writing: “A hose because it draws people in and suffocates them” (P11).

The analysis of the metaphors generated by the participants reveals a shared understanding of the example writing mode, emphasizing the significance of unity and the necessity of supporting details. The participants illustrated their comprehension of the structural elements of an example paragraph through various metaphors, such as cooking and tree branches, which highlight the importance of cohesive components. They not only reflect the complexity of the writing process but also underscore the value of metaphorical expression in uncovering internalized understandings, challenges, and developmental shifts stimulated by the multi-modal intervention.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, participants generated a wide range of metaphors to articulate their perceptions and experiences related to the multi-modal intervention for the process paragraph mode. Among these, the most frequently used metaphor was stairs, a clear reflection of students’ awareness of the sequential and hierarchical structure that defines this paragraph type. One participant stated: “Process paragraph is definitely like stairs. Each phase we write for supporting details in the process paragraph definitely represents a stair” (P39). This metaphor suggests a strong conceptual grasp of progression—each step (or sentence) must logically follow the previous one to lead the reader through a coherent process. The vertical movement implied in “stairs” also hints at the cumulative development of ideas, where skipping a step can lead to failure in both meaning and structure. Likewise, recipe and life were the second most frequently emphasized metaphors, further reinforcing this emphasis on ordered stages. For example, one of the participants using the metaphor recipe stated: “It is like a recipe because the recipe also tells you how to make it step by step” (P15). This metaphor reinforces the instructional function of process writing and the necessity of clarity and logical sequencing. Similarly, another participant used life, indicating that she views process writing as not only linear but also reflective of real-life logic, where experiences unfold in structured and meaningful sequences: “I think it is like human life. Events are hierarchical and follow each other” (P20). Other metaphors such as diet, climbing, water flow in heating pipe, digestive system also centered around the idea of flow, movement, and physiological or mechanical processes. These metaphors imply not just stages, but also internal consistency and direction, suggesting that the process paragraph is understood as a system that must operate smoothly for successful communication. Besides, some participants also stated that writing a process paragraph is like growing plant, cooking, making a cake referring the importance of unity, cohesion, and coherence by using transition signals in a paragraph as well as its feature related time and process. Following statement presents the explanation of the metaphor growing plant as: “Like growing plants. It contains stages to be followed. When you use transition expressions correctly while writing these stages, you will be successful in your process paragraph in terms of both meaning and unity as well as coherence” (P47). The metaphor connects natural development with the mechanics of writing, indicating a deeper appreciation of how linguistic connectors contribute to the clarity and unity of the paragraph. Moreover, some metaphors generated by the participants such as dibbling, constructing a building, chess, and walking were associated with the knowledge on the organization of the process paragraph and paragraph writing process. Following statement on dibbling reveals a procedural understanding and the need for strategic planning: “It is like dibbling because you need to know the rules and steps while dibbling. We need to know how to do while writing a process paragraph” (P11). Constructing a building was used to emphasize foundational knowledge and structural integrity as well as cumulative and integrative nature of process writing:

“Constructing a building. The foundation of the construction must be durable, and each floor must be done carefully so that the building can look strong and esthetic when the construction is finished as in process paragraph. The process paragraph is like it; you need to have content knowledge on the writing topic and support your steps with appropriate and well-structured examples and explanations” (P42).

Some metaphors brought in a more affective or motivational dimension. Two participants used toddler as a metaphor, but with different perspectives. As one of them associated toddler as a metaphor for the nature of process paragraph containing phases, the other one associated it with having success with perseverance despite the difficulties as the following: “Toddler because it goes through hell or high water” (P10). This metaphor reflects the psychological challenge and determination often experienced during the writing process.

Finally, a few metaphors reflected negative experiences or emotional strain. These included endless way and missing-page book, which suggest feelings of frustration, cognitive overload, or a lack of unity. One student remarked: “Like an endless way. There are many details to explain the steps. It seemed like the journey would never end” (P26), revealing the perception of overwhelming complexity. Another participant referring to the unity problem in her paragraph regarded the process paragraph as a missing page book: “I think, like a missing-page book because I failed in paragraph unity” (P67).

Overall, the metaphor analysis demonstrates that participants developed a conceptually accurate understanding of the process paragraph, recognizing its hierarchical structure, stepwise development, and the importance of coherence. However, the presence of emotionally charged metaphors indicates that while the intervention enhanced their cognitive grasp of the writing process, it also surfaced the emotional and psychological challenges they encountered.

Figure 5 displays the word cloud of metaphors generated by participants for the narrative paragraph writing mode. Among these, life and storyteller emerged as the most frequently emphasized metaphors, primarily due to the rhetorical characteristics of narrative writing-namely its reliance on time, sequence, and emotional engagement. That is, the narrative writing mode consists of a sequence of events much like life itself, with its natural flow of occurrences and time. One participant noted: “It is like a life because in human life, events occur according to a certain flow and time” (P6), directly aligning the structure of narrative paragraphs with the temporal flow of real-life events. Another elaborated on this by emphasizing the chronological dimension: “I liken it to a person’s life from birth to death. Everything is in order and chronological” (P18). These metaphors reveal participants’ understanding of narrative coherence through a sequence of actions and developments over time. Similarly, various metaphors such as memory, one’s life flashes before his eyes, diary underscore the sequential and experiential quality of narrative writing. These conceptualizations reflect the students’ growing awareness that effective narratives are constructed through temporally ordered experiences that evoke memory and introspection.

Likewise, the storyteller is another metaphor frequently emphasized. This metaphor centers on the expressive and emotive qualities of narrative writing, particularly the use of sensory and affective language. One participant explained: “I think it is like those who told us fairy tales when we were little. Because in this type of paragraph, we describe the emotions we felt at that moment and what happened, as they did” (P33). This statement underscores the participant’s recognition that narratives require not only a sequence of actions but also emotional resonance to engage the reader. Moreover, documentary narrator and commentator highlight the performative and emotional aspects of storytelling. While the participant using the metaphor documentary narrator stated: “Like a documentary narrator. Because it makes us feel excitement and emotion” (P51), another participant about commentator as a metaphor said: “It is like a commentator because it tells the events excitedly and emotionally” (P27). These metaphors suggest that participants are attuned to the narrative mode’s demand for both structured content and expressive delivery. The metaphor novel was used to emphasize the fictional and imaginative potential of narrative writing. In parallel, metaphors such as laying flagstone, computer games, and universe addressed the procedural and organizational dimensions of this writing mode. Following statement presents the explanation the metaphor computer games as: “Like computer games such as Candy Crush and Super Mario. At each stage, there are rules and things to be done to move to the next level. When you do these, you move to the next stage” (P11). This metaphor reflects an understanding of writing as a progressive task, requiring mastery of conventions and logical sequencing. One of the participants underlined the paragraph organization with the metaphor universe as: “I think it is like universe. Because it must have an organization for a universe to be a universe. An organization is also required when writing this paragraph type” (P31). Both metaphors illustrate how students associate narrative writing with complexity, structure, and internal logic.

Two participants drew comparisons between narrative and other paragraph types, specifically descriptive and process paragraphs. This observation likely stems from the shared characteristics of these modes—sensory detail and chronological order. One participant, for instance, described the narrative paragraph as an extensive process paragraph, noting that the narrative builds on the process mode by integrating detailed sequences with descriptive elaboration. This reflection demonstrates students’ developing metalinguistic awareness and ability to differentiate between rhetorical functions.

In addition to positively framed metaphors, some participants expressed emotional or cognitive struggles through negatively framed ones. For example, using life as a metaphor, the participant likely references difficulty with initiating the narrative structure, despite having sufficient content to share: “Like life, especially my own life. There is so much to tell but I don’t know where to start” (P1). Likewise, another participant regarded the narrative paragraph as an unfinished story revealing a self-aware acknowledgment of incomplete mastery and continued challenges with narrative cohesion: “It is like an unfinished story because I still have my shortcomings and haven’t grasped it completely” (P60).

Taken together, these metaphors demonstrate a rich understanding of narrative writing as both structured and emotionally engaging. The participants’ conceptualizations capture both the logical structure and creative engagement required by this rhetorical mode. The frequent reference to metaphors of time, sequence, emotion, and structure suggests that the multi-modal intervention enhanced students’ awareness of the narrative genre’s defining characteristics, while also revealing their affective responses and personal learning trajectories.

As demonstrated in Fig. 6, participants generated a range of metaphors to express their perceptions and experiences regarding the opinion writing mode. The most emphasized metaphors, job interview, 3D painting, looking at scenery, discussion, and dressmaking, collectively reflect a strong awareness of the rhetorical characteristics of opinion writing, particularly persuasion, evidence-based reasoning, and individual expression. One participant who use job interview as metaphor explained it as the following: “I think it is like a job interview because I need to convince the boss and prove myself. While doing this, I need to use my experiences to support my opinions and convince him” (P35). This metaphor highlights the writer’s perceived need to construct a convincing and credible argument, much like a job candidate who must present themselves persuasively to an employer. The emphasis on using personal experience as supporting evidence also aligns with the rhetorical strategies commonly employed in effective opinion writing.

Similarly, 3D painting and looking at scenery both reflect the idea that opinions are inherently subjective and shaped by individual perspective. For example, while one of them using 3D painting stated, “Everyone can look at 3D painting from a different angle because everyone’s opinion, and approach can be different” (P48), one of the participants using looking at the scenery remarked as: “Like looking at the scenery. Everyone has a different perspective on the landscape” (P27). These metaphors reveal an understanding that opinion writing accommodates multiple viewpoints and that articulating a personal stance involves acknowledging diversity in interpretation and perspective. The metaphor discussion reinforces this dialogic nature of opinion writing. As one participant put it: “I think it is like a discussion. Two groups with different opinions try to convince each other by presenting certain facts and explanations” (P38). This suggests that the participants not only recognize the persuasive intent of the genre but also understand the need for factual backing and respectful engagement with opposing views. Other metaphors in this category, such as salesman, article, jury, commenting, and counterview, further underscore the argumentative structure of opinion writing, where evidence, clarity, and persuasive language are crucial to credibility. Besides, as mentioned above, dressmaking is among the most frequently mentioned and serves as a powerful illustration of the compositional elements required in an opinion paragraph. One of the participants using this metaphor said, referring to the components that constitute the opinion paragraph, the following: “Like dressmaking. When sewing a dress, you need needle, thread, sewing machine, scissors, and fabric. In the same way, there are things you need when writing an opinion paragraph such as appropriate words, conjunctions, facts, or explanations to support your opinions” (P29). It draws attention to the interdependence of different components in crafting a coherent argument, where each rhetorical device contributes to the final product’s functionality and effectiveness. A similar perspective is evident in the 3 in 1 coffee metaphor, which emphasizes the integrated nature of opinion writing: “An opinion paragraph is like 3 in 1 coffee. It contains opinions, facts, and explanations” (P2). This metaphor captures the essential ingredients of an effective opinion paragraph and reflects students’ grasp of structural unity and argumentative support.

Besides, metaphors such as my garden and drawing foreground the expressive and individualistic dimension of opinion writing. One participant stated: “My garden, because we can use the garden as we want, because it belongs to us. Since the opinion paragraph belongs to us in the same way, we can freely express our opinions we want” (P18), emphasizing the writer’s agency and ownership of their ideas. Another echoed this sentiment: “Like drawing because I had the brush” (P39), suggesting that opinion writing enables the writer to construct and shape meaning with creativity and autonomy.

From a slightly different angle, one participant introduced the metaphor endless road, reflecting an awareness of the importance of focus and limitation in argumentative writing: “Like an endless road. Because you have to use only one idea in a paragraph. If you have a lot of knowledge about it, there is no limit to what you can write, but then it won’t be a paragraph” (P66). This metaphor demonstrates metacognitive reflection on coherence and unity—core components of well-structured academic writing. The student appears to acknowledge the challenge of narrowing content while still maintaining depth and clarity.

These metaphors reveal a nuanced understanding of the opinion writing mode emphasizing, persuasion, evidence-based reasoning, and personal expression. The frequent use of metaphors, such as job interview, 3D painting, and discussion demonstrates students’ awareness of perspective-taking and argumentative structure. Unlike other writing modes, no negative metaphors were reported, suggesting that the multi-modal intervention was particularly effective in fostering clarity and confidence. The richness of the metaphors highlights the participants’ internalization of key rhetorical principles and underscores the pedagogical value of metaphor elicitation as a tool for assessing both cognitive and affective dimensions of learning.

Discussion

In what ways do these metaphors inform their insights into the multi-modal intervention?

This paper sheds light on EFL learners’ metaphorical conceptualizations of writing during a multi-modal writing intervention, in an attempt to explore the cognitive as well as emotional dimensions of EFL learners’ writing experience. Not only does the investigation responded to a pedagogical need of employing multi-modal intervention that are necessary in today’s literacy context but serves to manifest the power of metaphors in cognizing what constitutes learners’ perceptions and attitudes regarding various writing modes.

The shift towards multi-modal interventions in education, especially in EFL contexts, reflects an urgent need to cater to the diverse modes of communication prevalent in the 21st century. As supported by the findings of this study, such interventions have statistically significant positive effects on student performance in a variety of modes, including descriptive, narrative, process, and opinion writing (Archer, 2022; George, 2022; Hasbullah et al., 2023; Jeanjaroonsri, 2023; Jiang et al., 2022; Navila et al. 2023; Rahmanu & Molnár, 2024). This is consistent with calls for a more inclusive pedagogy - one that acknowledges the realities of diverse social space and the challenges of 21st century digital communication (Cope & Kalantzis, 2009; New London Group, 1996). The increases in student writing ability highlight the potential of multi-modal approaches, both to develop writing ability, as well as equip learners to communicate effectively across a wider range of modes of communication in increasingly diverse and interconnected contexts. This mirrors the findings from the metaphor analysis, highlighting that as emotional and cognitive barriers represented through metaphors are tackled up front, learners are empowered to produce better writing. The performance gains’ statistical significance serves to validate that metaphorical language and self-concept drive writing experiences—when students write through the frame of metaphor, they do so more positively, and their skills reflect this qualitatively.

To this end, metaphors are used as tools to recognize learners’ responses towards beliefs, feelings, and attitudes towards multi-modal writing intervention. Findings show that metaphors known as “cooking” and “tree-branch” represent the learners’ perspectives regarding the structure and unity in their writing. These creative analogies shed light on the mental processes involved as students work through the complex elements of writing. More significantly, the recurrent invocation of such metaphors suggests that they may be somewhat more emotionally invested, as such references express writers’ social and emotional relation to writing, as well as perceived barriers and ambitions, which is in line with the previous research (e.g., Aydın & Baysan, 2018; Hamouda, 2018; Phyo et al., 2023). In contrast to previous studies that noted a prevalence of negative metaphors among students (Hamouda, 2018; Wan, 2014), the data in this report indicates a shift towards more constructive and affirmative representations of their writing journeys. This shift highlights not only improved abilities in writing but also a confidence booster stemming from the multi-modal intervention.

Implications and conclusion

Addressing the contemporary educational needs and practices, especially in the EFL context, the study offers several noteworthy implications. First, the significant improvements observed in writing performance across five different modes-descriptive, example, narrative, process, and opinion- indicate that multi-modal interventions have to potential to effectively enhance learners’ writing skills. This finding supports the integration of such interventions into the curricula to foster comprehensive writing skills among EFL learners. Besides, the study emphasizes the value of adopting multi-modal and inclusive pedagogical approaches aligned with 21st-century educational priorities. The shift from predominantly negative to more positive metaphors illustrates the potential of multi-modal interventions to not only improve writing performance but also enhance students’ confidence and emotional engagement with the writing process. Thirdly, the findings from metaphor analysis can provide educators with insights into students’ cognitive and emotional perspectives (Halliday, 1978; Oxford et al., 1998). Integrating metaphor analysis into pedagogical practices can help educators design more tailored and empathetic teaching strategies that resonate with students’ learning experiences, ultimately leading to better engagement and improved outcomes (Aydın & Baysan, 2018; Hamouda, 2018; Öztürk, 2022; Paulson & Armstrong, 2011; Pavesi, 2020; Phyo et al., 2023; Wan, 2014). Moreover, students’ metaphorical conceptualizations shed light on the broader cultural narratives influencing learners’ experiences, which underscores the importance of culturally responsive teaching that considers both linguistic proficiency and cultural contexts. Last, the integration of quantitative performance data and qualitative metaphor analysis strengthens our understanding of writing instruction by offering both measurable outcomes and nuanced insights into learners’ experiences. This dual approach provides educators with a richer foundation for developing supportive, engaging, and culturally sensitive learning environments in EFL settings. Overall, the study reinforces the idea that effective writing instruction in EFL contexts should be multi-modal, responsive to students’ individual needs, and cognizant of the cultural dimensions of language learning.

However, there are some limitations of the study. The study used a single group of prep-class students, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. A larger and varied sample of EFL students from different cultural and educational contexts could provide a broader understanding of the impact of multi-modal intervention on EFL learners. Moreover, the intervention’s duration may not have been long enough to observe enduring effects on writing performance and learner perceptions. At this point, researchers may consider conducting longitudinal studies to evaluate the long-term impact of multi-modal intervention. Besides, in reflective journals, students might express what they perceive as acceptable or desirable responses, which may be subject to bias. To mitigate such biases, future research could employ mixed methods designs, incorporating in-depth interviews, focus groups, and triangulation with quantitative data to obtain a more holistic understanding of learners’ writing experiences. Although both quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed, additional triangulation methods (e.g., peer feedback or teacher evaluations) could have provided a richer and more reliable understanding of students’ writing experiences. While the focus on EFL in Turkiye offers valuable insights, the cultural context may not fully represent the experiences of EFL learners in other regions or backgrounds. Further research should explore EFL writing experiences across different cultural contexts, allowing for a comparison of metaphor usage and perceptions to identify globally relevant pedagogical strategies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahkemoglu H (2011) A Study on metaphorical perceptions of EFL learners regarding foreign language teacher. [Unpublished master dissertation]. University of Cukurova

Akbari M (2013) Metaphors about EFL teachers’ roles: a case of Iranian non-English major students. Int J Engl Lang Transl Stud 1(2):100–112

Archer A (2022) A multimodal approach to English for academic purposes in contexts of diversity. World Englishes Spec Ed ‘World Englishes Engl Specif Purp’ 41(4):545–553

Aydın S, Baysan S (2018) Metaphors used by Turkish EFL learners to describe their writing processes. J Lang Linguistic Stud 14(3):116–131

Bessette H, Paris N (2020) Using visual and textual metaphors to explore teachers’ professional roles and identities. Int J Res Method Educ 43(2):173–188

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Carpenter J (2008) Metaphors in qualitative research: shedding light or casting shadows? Res Nurs Health 31(3):274–282

Cope B, Kalantzis M (2021) Pedagogies for digital learning: From transposi- tional grammar to the literacies of education. In M. G. Sindoni, & I. Moschini (Eds.), Multimodal literacies across digital learning contexts (pp. 34–53). Routledge

Cope W, Kalantzis M (2009) Multiliteracies”: new literacies, new learning. Ped- Agogies 4(3):164–195

Creamer EG (2020) Tamamen bütünleştirilmiş karma yöntem araştırmalarına giriş [An introduction to fully integrated mixed methods research]. (I. Seçer & S. Ulaş, Çev. Ed.). Vizetek. (Original work published in 2018)

de Souza LMTM (2017) Multiliteracies and Transcultural Educa- tion. In O. Garcia, N. Flores & M. Spotti (Eds.), The Oxford Hand- Book of Language and Society (pp. 261–281). Oxford University Press

East M, Young D (2007) Scoring L2 writing samples: exploring the relative effectiveness of two different diagnostic methods. N. Z Stud Appl Linguist 13(1):1–21

Eren A, Tekinarslan E (2012) Prospective teachers’ metaphors: teacher, teaching, learning, ınstructional material and evaluation concepts. Int J Soc Sci Educ 3(2):435–445

Farías M, Veliz L(2016) EFL students metaphorical conceptualizations of language learning. Trabalhos em Lingüística Aplicada 55(3):833–850

Farrell TSC (2016) The teacher is a facilitator: reflecting on ESL teacher beliefs through metaphor analysis. Iran J Lang Teach Res 4:1–10

Fraenkel JR, Wallen NE, Hyun HH (2012) How to design and evaluate research in education (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill

George P (2022) The rhetorical value of multimodal composition. Int TESOL J 20:1177

Halliday MAK (1978) Language as social semiotic: the social interpretation of language and meaning. Arnold Edward, London

Hamouda A (2018) An Investigation of the concept of learning essay writing among Saudi English majors through metaphor analysis. Veda’s J Eng Langu Lit -JOELL 5(1):338–361

Hartmann DP (1977) Considerations in the choice of interobserver reliability measures. J Appl Behav Anal 10:103–116

Hasbullah H, Wahidah N, Nanning N (2023) Integrating multiple intelligence learning approach to upgrade students’ English writing skills. Int J Lang Educ 7(2):34383

İnceçay V (2015) The foreign language classroom is like an airplane” metaphorical conceptualizations of teachers’ beliefs. Turkish Online J Qual Inq 6(2):74–96

Jeanjaroonsri R (2023) Thai EFL learners’ use and perceptions of mobile technologies for writing. LEARN J Lang Educ Acquis Res Netw 16(1):169–193

Jewitt C, Kress G (Eds.). (2003) Multimodal literacy. Peter Lang

Jiang L, Yu, S, Lee I (2022) Developing a genre-based model for assessing digital multimodal composing in second language writing: Integrating theory with practice. J Second Lang Writing 57:100869

Johnson RB, Christensen LB (2020) Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (7th ed.). Sage

Knoch U (2009) Diagnostic assessment of writing: a comparison of two rating scales. Lang Test 26(2):275–304

Kress, G (2009). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge

Kress G, Selander S (2012) Multimodal design, learning and cultures of recognition. Internet High Educ 15(4):265–268

Lakoff G, Johnson M (1980) Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Lakoff G (1993) The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (2nd ed., pp. 203-204). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

Levin T, Wagner T (2006) In their own words: understanding student conceptions of writing through their spontaneous metaphors in the science classroom. Instruct Sci 34:227–278

Lim FV (2021) Towards Education 4. 0: An agenda for teaching multiliteracies in the English language classroom. In F. A. Hamied (Ed.), Literacies, culture, and society towards industrial revolution 4.0: Reviewing policies, expanding research, enriching practices in Asia (pp. 11–30). New York: Nova Science

Lim FV, Towndrow PA, Tan JM (2021) Unpacking the teachers’ multimodal pedagogies in the Singapore primary English language classroom. RELC Journal. Advance online publication

Lu Y (2017) Cultural conceptualisations of collective self-representation among Chinese immigrants. In F. Sharifian (Ed.) Advances in cultural linguistics (pp. 89–110). Springer

McMillan JH, Schumacher S (2014) Research in education: Evidence based inquiry (7th ed.) Pearson International Edition

Mizusawa K, Kiss T (2020) Connecting multiliteracies and writing pedagogy for 21st century english language classrooms: key considerations for teacher education in Singapore and beyond. J Nusant Stud 5(2):192–214

Morita-Mullaney T (2021) Multilingual multiliteracies of emergent bilingual families: transforming teachers’ perspectives on the ‘literacies’ of family engagement. Theory into Pract 60(1):83–93

Navila A, Rochsantiningsih D, Drajati NA (2023) EFL pre-service teachers’ experiences using a digital multimodal composing framework to design digital storytelling books. IJELTAL (Indonesian J Engl Lang Teach Appl Linguist) 8(2):217–217

New London Group (1996) A pedagogy of multiliteracies: designing social futures. Harv Educ Rev 66(1):60–92

Nunan D (1999) Second Language Teaching & Learning. Heinle & Heinle Publishers

Oxford RL, Tomlinson S, Barcelos A, Harrington C, Lavine RZ, Saleh A, Longhini A (1998) Clashing metaphors about classroom teachers: toward a systematic typology for the language teaching field. System 26(1):3–50

Öztürk G (2022) Exploring metaphorical representations of language learning among Turkish university students. TESOL J 12(1):45–60

Palinkašević RD (2021) English language learning from the perspective of students—Pre-service preschool teachers. Teach Innov 34(1):123–134

Palsa L, Mertala P (2019) Multiliteracies in local curricula: conceptual contextualizations of transversal competence in the Finnish curricular framework. Nord J Stud Educ Policy 5(2):114–126

Paulson EJ, Armstrong SL (2011) Mountains and pit bulls: students’ metaphors for college transitional reading and writing. J Adolesc Adult Lit 54(7):494–503

Pavesi GS (2020) Writing is a journey: a study of post-graduate students\‘perceptions of academic writing in English [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of São Paulo

Phyo WM, Nikolov M, & Hódi Á (2023) Doctoral students’ English academic writing experiences through metaphor analysis. Heliyon, 9(2):e13293

Polzenhagen F, Dirven R (2008) Rationalist or romantic model in globalisation? In G. Kristiansen & R. Dirven (Eds.),Cognitive sociolinguistics: Language variation, culturalmodels, social systems (pp. 237–300). De GruyterMouton

Polzenhagen F, Wolf H-G (2007) Culture-specific conceptualizations of corruption in African English: Linguistic analyses and pragmatic applications. In F. Sharifian & G. Palmer (Eds.), Applied cultural linguistics: Implications for second language learning and intercultural communication (pp. 125–168). John Benjamins

Reif M, Polzenhagen F (2023) Introduction. In M. Reif&F. Polzenhagen (Eds.), Cultural linguistics and critical discourse studies (pp. 1–14). John Benjamins

Rahmanu E, Molnár G (2024) Multimodal immersion in english language learning in higher education: a systematic review. Heliyon 10(19):38357

Sharifian F (2017) Cultural linguistics: Cultural conceptualizations and language. John Benjamins

Stemler SE (2004) A comparison of consensus, consistency, and measurement approaches to estimating interrater reliability. Pract Assess Res Eval 9:4

van Leeuwen T (2017) Multimodal literacy. Metaphor 4:17–23

Veliz L, Véliz-Campos M (2022) A socio-semiotic analysis of latino migrants’ metaphorical conceptualizations of language learning. J Lat Educ 21(2):142–156

Wan W (2014) Constructing and developing ESL students’ beliefs about writing through metaphor: an exploratory study. J Second Lang Writ 23:53–73

Watts R (2011) Language myths and the history of English. Oxford University Press

Weigle SC (2002) Assessing writing. Ernst Klett Sprachen

Wolf HG, Polzenhagen F (2009) World Englishes: A cognitive sociolinguistic approach. Mouton de Gruyter

Acknowledgements

This study is based on Ph.D. dissertation of the first/corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G.: Conceptualization. H.Ç.: Conceptualization, Methodology H.Ç.: Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation. H.Ç.: Visualization, Investigation, Software, Validation. M.G.: Supervision. M.G.: Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in line with all ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was received from the Educational Sciences Ethics Committee at Ataturk University in Turkiye (Date: 30.03.2023/Approval number: 16).

Informed consent

The participants were Turkish EFL students enrolled in a preparatory classroom at Atatürk University. All participants provided written informed consent between April and June 2023. The scope of the consent included their voluntary participation in the study, the use of their written products as research data, the use of their reflection papers (including metaphor prompts), and the publication of their data as part of academic research outputs. Participants’ confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained throughout the study, and all data were used solely for research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

ÇEŞME, H., GEÇİKLİ, M. EFL learners’ metaphorical insights into multi-modal writing intervention. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1377 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05710-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05710-1