Abstract

It is widely known that partisan attitudes drive individuals to mistakenly believe misleading information is true, resulting in the spread of misleading information. It is also possible that partisan attitudes create a gap between belief and behavior. That is, partisan attitudes lead individuals to spread misleading information even if they know that it is unlikely to be true. However, the latter possibility has not been closely examined. This study aims to fill this lacuna. We find evidence that partisan attitudes hindered the correction of mistaken beliefs, which drove individuals to spread misleading information. However, there is no evidence that partisan attitudes contribute to the spread of misleading information by widening the gap between belief and behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

The proliferation of misleading information has become a significant threat to democracy, as it hampers voters’ ability to make informed decisions. Recent research indicates that while much scholarly attention has been directed toward outright falsehoods, the greatest risk may come from more nuanced content that is “factually accurate but nonetheless misleading” (Allen et al. 2024). Given the severity and immediacy of this issue, many researchers are seeking strategies to address the spread of such misleading information.

The debunking strategy, which aims to show a piece of information is misleading, has been shown effective for countering misleading information (Carnahan and Bergan, 2022; Walter and Murphy, 2018). Unfortunately, however, misleading information continues to spread despite the widespread use of debunking strategies, including fact-checking (e.g., Pereira et al. 2022) and balanced reporting (Merkley, 2020). This begs the question: what has gone wrong?

The mechanism underlying the debunking strategy is that factual information or balanced reporting can correct people’s beliefs about misleading information, thereby preventing it from spreading.Footnote 1 In this regard, many have examined potential barriers to belief correction, including the failure to deliver factual information to target audiences, cues from political elites, and partisan-motivated reasoning (Badrinathan, 2021; Ecker et al. 2022; Flynn et al. 2017; Lee and Jang, 2023; Nyhan, 2021; Peterson and Iyengar, 2021; Scheufele and Krause, 2019; Taber et al. 2009; Taber and Lodge, 2006). While previous studies have made important contributions to understanding the challenges of correcting beliefs, they have focused only on one of the mechanisms that cause the persistent spread of misleading information: the divergence between factual evidence and beliefs. It is important to note, however, that a gap between beliefs and behaviors can also contribute to the spread of misleading information (Osmundsen et al. 2021; Pennycook and Rand, 2021).

This paper studies the possible gap between beliefs and behaviors. This is a crucial area of research because such a gap implies that belief correction is insufficient to curb the spread of misleading information. Indeed, there is a long history of discussion on the belief-behavior gap across several disciplines in social sciences focusing on the discrepancy between some values regarded as correct and the actual behavior or the intention to behave, most notably in education, public policy, and consumer behavior. For example, Leonard and Scott-Jones (2010) explore the gap between perceptions of premarital sex and actual sexual behavior among high school students, while Echegaray and Hansstein (2017) highlight the discrepancy between recycling intentions and practices. A long-established body of literature has also demonstrated that ethically-minded consumers often fail to make ethical purchases (Alsaad, 2021; Dong et al. 2022; Khan and Abbas, 2023; Langenbach et al. 2020; Mahardika et al. 2020). However, despite the issue’s salience, there is no discussion about this gap concerning the potential contrast between the perceived accuracy of a piece of information and the intention to share it. This is a particularly important research question because the implicit assumption of the belief correction literature is that voters’ behavioral decisions are based solely on their beliefs and not on other factors, such as their partisan attitudes. However, if there is a gap between beliefs and behaviors, voters may engage in the dissemination of misleading information even after their mistaken beliefs about it have been successfully corrected.

In this context, it is important to distinguish between the different motivations behind sharing misleading information. On one hand, a person may share information under the mistaken belief. On the other hand, someone knowingly shares false information with the deliberate intent to mislead others, despite being aware of its potential to deceive. Narrowing the gap between factual evidence and belief correction may effectively address the spread of misleading information based on mistaken beliefs. However, such an approach would not be sufficient to curb the intentional spread of misleading information if behavioral decisions are made contrary to beliefs. Partisan attitudes can cause the divergence between belief and behavior. Partisan voters intentionally spread it for various purposes (e.g., to promote their partisan positions to out-partisans and/or to align their behaviors with their partisan values or norms) even if they know that the information is likely to be misleading.

To examine the potential gap between beliefs and behaviors driven by partisan attitudes, it is crucial to distinguish whether people spread misleading information because they genuinely believe it to be true or due to their partisan attitudes. This is a difficult task because people are unlikely to admit that they intentionally spread misleading information (Tandoc et al. 2018). Although several studies have reported the effect of partisan attitudes on sharing intentions or behaviors (Lee and Jang, 2023; Osmundsen et al. 2021), these findings do not speak to the motivation behind sharing behaviors. This is because the previous studies are potentially subject to omitted variable bias originating from not controlling for individuals’ beliefs about misleading information, which are also correlated with individuals’ partisan attitudes. That is, partisan attitudes may lead individuals not only to override their beliefs but also to be reluctant to correct beliefs. To address this issue, we conducted a survey experiment in which participants were asked to rate their perceptions of the truthfulness of misleading information about nuclear power policy in South Korea and indicate their intention to share it before and after debunking the misleading information. We then evaluate the influence of partisan attitudes on the correction of intentions to share misleading information while controlling for the effect of belief correction.

Since our research question is built upon the previous finding of the disrupting effect of partisan attitudes on belief correction, it is necessary to see if the effect is replicated in our data. Unsurprisingly, we confirmed that partisan voters are more likely to resist correcting their mistaken beliefs when the misleading information is consistent with their partisan attitudes. We then move to our main question about whether partisan attitudes widen the gap between belief and intention. We found evidence that correcting beliefs facilitates correcting intentions to spread misleading information, regardless of individuals’ partisan attitudes. However, we found no evidence that partisan motivations directly disrupt intention correction after belief correction. There is no evidence that partisan voters, compared to independent voters, are more reluctant to correct their intentions to share misleading information congruent with their partisan positions. Overall, our findings suggest there is no gap between beliefs and behaviors caused by partisan attitudes, although partisan attitudes exacerbate the spread of misleading information by hindering belief correction.

Hypotheses

Partisan attitudes and belief correction

The main purpose of this study is to examine whether individuals’ partisan attitudes lead them to share information despite knowing the information is misleading. To fulfill this goal, individuals’ prior and posterior beliefs about misleading information, which is correlated with both their partisan attitudes and sharing behaviors, need to be controlled. One way to do this is to measure changes in individuals’ beliefs after the debunking and use this measure as a control variable. Thus, although it is not the primary interest of our study, it is necessary to measure individuals’ belief changes, which also provides us an opportunity to add empirical evidence to the literature on partisan barriers to belief revision.

Numerous studies have documented that partisan attitudes hinder the correction of mistaken beliefs about misleading information. The following two theories about the mechanisms underlying this effect are particularly relevant to our study. The partisan-motivated reasoning theory argues that individuals’ directional partisan goals bias their evaluation of information to defend and support their pre-existing partisan beliefs and opinions (e.g., Flynn et al. 2017; Gaines et al. 2007; Kraft et al. 2015; Peterson and Iyengar, 2021; Taber et al. 2009; Taber and Lodge, 2006), or, at least, they tend to conform to the beliefs shared with their co-partisans (Cohen, 2003). This partisan-motivated reasoning leads individuals to discount corrective information and maintain beliefs in the information that is factually incorrect but congruent with their partisan attitudes (Lee and Jang, 2023; Walter and Murphy, 2018; Walter and Tukachinsky, 2020). In the partisan-motivated reasoning theory, partisan attitudes play an active role by causing confirmation bias that leads partisan-directional goals to outweigh individuals’ motivations to seek out the correct information.

However, partisan attitudes may play a passive role when individuals pursue the accuracy of information but are unable or can only fulfill this goal imperfectly due to the lack of relevant knowledge. In this case, they may rely on partisan cues, which can be their party’s position on the issue, to form their beliefs about information, because individuals trust in-group members more than out-group members (Mackie et al. 1990). When it is cognitively demanding to evaluate the accuracy of information, partisan identity can serve as a cognitive shortcut that reduces the uncertainty of the world, by which individuals form their beliefs regarding information (Turner, 1987). Partisan cues as credible information sources lead partisan attitudes to hinder belief revision. Given that individuals tend to trust information sources that share their values and worldviews (Briñol and Petty, 2009), they may regard cues sharing their partisanships more credible than exogenously given corrective information (see Shin and Thorson, 2017). They would thus disregard corrective information. Note that this theory suggests that partisan attitudes influence individuals’ beliefs when they make an uneducated evaluation of misleading information.

Although the foregoing two theories present different mechanisms, they both produce the same hypothesis as follows.Footnote 2

H1: Individuals are less likely to correct their beliefs when the debunked misleading information is congruent with their partisan positions.

H1 is not new and has already been verified in many studies. Nevertheless, we test the hypothesis as a building block for our main hypothesis of interest which will be introduced shortly. However, it is noteworthy that H1 suggests two directions of the effects. On the one hand, partisan voters are expected to correct their beliefs about the misleading statement less when the misleading information is consistent with their partisan positions, which we call “resistance effect.” On the other hand, it is also possible that partisan voters are expected to correct their beliefs more after debunking when misleading information contradicts their partisan positions, which we call “facilitation effect,” Therefore, we can divide H1 into the following sub-hypotheses H1a and H1b, where H1 holds if either H1a, H1b, or both are empirically verified.

H1a (resistance effect): Individuals are likely to resist correcting their beliefs when the debunked misleading information is congruent with their partisan positions.

H1b (facilitation effect): Individuals are more likely to correct their beliefs when the debunked misleading information is incongruent with their partisan positions.

It is necessary to note that personal traits unrelated to partisan identity can hinder belief revision. For example, Susmann and Wegener (2022) report that belief revision per se produces psychological discomfort, which motivates individuals to disregard correction in order to avoid negative feelings, in the absence of a partisan context. Since these personal traits are not partisan in nature, we can safely assume that they do not induce systematic bias in our estimates of the effect of partisan attitudes.

Partisan attitudes, belief correction, and sharing behaviors

Regarding the social sharing of misleading information, there are two distinct motivations. First, individuals’ beliefs about the truthfulness of misleading information lead individuals to share it (Lee and Jang, 2023; Pennycook et al. 2021; Su et al. 2019; Yaqub et al. 2020). Individuals may share information to establish social status or to socialize (Dunne et al. 2010; Lee and Ma, 2012; Park and Blenkinsopp, 2009). Individuals also may spread information for altruistic knowledge sharing (Apuke and Omar, 2021; Ma and Chan, 2014; Plume and Slade, 2018); that is, sharing information because they believe that the information would be helpful to others. In both scenarios, individuals are motivated to share what is perceived to be truthful because sharing information that later turns out to be misleading damages the sharer’s reputation or contradicts the altruistic purpose of helping others. If this is true, individuals are expected to correct their sharing intention once they are convinced that they have mistakenly believed in it. Thus, we test the following hypothesis.

H2: Belief correction is positively associated with the correction of the sharing of misleading information.

Partisan attitudes, however, may obstruct the correction of the sharing intention in both direct and indirect ways. Partisan attitudes may hinder belief correction, which, in turn, leads to a failure to motivate individuals to correct their sharing intention (Su et al. 2019). Of course, this indirect mechanism relies on the premise that both H1 and H2 are true.

The primary focus of our study is to investigate whether partisan attitudes directly wield a dominant influence on sharing behavior, potentially surpassing the impact of belief correction (see Pennycook and Rand, 2021). That is, individuals can resist correcting their sharing behaviors even after they have already corrected their mistaken beliefs because they place their preference for partisan identity above their beliefs about the truthfulness of misleading information. Since sharing information can shape the public agenda by enhancing the information’s visibility and influence (Bright, 2016; Singer, 2014), individuals may be motivated to intentionally share misleading information favorably toward their partisan positions to further their partisan agenda at the expense of risking their reputations (Van Bavel and Pereira, 2018). It is also possible that individuals intentionally share it to express loyalty to their parties to gain external trust from co-partisans (Hogg and Reid, 2006). In addition, individuals can gain expressive benefits by sharing it as partisan virtue signaling, even if such sharing fails to mislead others (Jordan and Rand, 2020). Note that both partisan agenda-setting and expressive motivations imply that individuals can be motivated to intentionally share information even though they do not believe in its truthfulness and, therefore, know it can mislead others. Thus, we test the following hypothesis.

H3: Regardless of belief correction, individuals are likely to resist correcting the sharing of misleading information when it is congruent with their partisan positions.

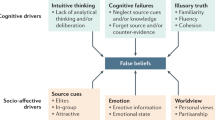

Figure 1 summarizes our hypotheses H1, H2, and H3. Partisan attitudes may indirectly influence sharing behavior by first shaping individuals’ beliefs (i.e., H1) and these altered beliefs, in turn, affect sharing behavior (i.e., H2). Additionally, H3 suggests that partisan attitudes may have a direct impact on sharing behavior, independent of any changes in beliefs.

H1, H2, and H3 suggest that the link between partisan attitudes and sharing behavior may be twofold. Firstly, if both H1 and H2 are validated, it would indicate an indirect influence of partisan attitudes on sharing behavior. Secondly, confirmation of H3 would imply a direct effect of partisan attitudes on sharing behavior.

A Survey

Background: Nuclear power policy in South Korea

Since our study focuses on partisan attitudes, misleading information needs to be related to an issue that is sufficiently salient and partisan to prompt individuals’ partisan identities (Shin and Thorson, 2017; Turner, 1987). Nuclear power policy is a highly salient and politicized issue in South Korea, with two major political parties divided on the issue. The People Power Party (PPP) and the Democratic Party (DP) hold opposing views on nuclear power. The conservative PPP supports the continuation and expansion of nuclear power, while the liberal DP opposes it, and this partisan divide also exists among voters.Footnote 3

As of 2023, there were 26 nuclear reactors in operation in South Korea, accounting for approximately 30.7% of the country’s total electricity mix (IAEA, 2024). In June 2017, the then-president, Moon Jae-in of the DP, decided to phase out nuclear power. Specifically, he declared that the government had no plans to build new nuclear power plants and would also discontinue extending the lifespan of existing plants (McCurry, 2019; Nguyen, 2019).

This nuclear phase-out policy sparked a heated controversy and faced strong opposition from the conservative Liberty Korea Party, which transformed into the PPP in 2020. This divide along the conservative/progressive ideological spectrum or party lines extended to the mass level. In October 2017, an opinion poll (N = 501) showed that 80.8% of progressive voters approved the nuclear phase-out policy, while only 38.7% of conservative voters did (Lee, 2017). According to another opinion poll conducted by the National Election Commission of South Korea in April 2022 (N = 1046), 68.2% of DP supporters endorsed the nuclear phase-out policy while the policy was approved by only 25.8% of PPP supporters. Kelleher (2022) also reported this ideological divide in public opinion on nuclear power policy in South Korea.

Given the partisan divide, the nuclear phase-out policy was one of the prominent issues during the South Korean presidential election that took place on March 9, 2022. The PPP consistently criticized the policy since its announcement by then-President Moon. Yoon Suk-Yeol, the PPP’s presidential candidate and eventual winner of the 2022 election,Footnote 4 pledged to scrap the nuclear phase-out policy if elected. Meanwhile, the DP’s presidential candidate Lee Jae-Myung proposed a nuclear reduction policy that was largely in line with Moon’s phase-out policy. Furthermore, each party’s position on the nuclear power policy was found to be one of the main predictors of the voters’ voting choices in the South Korean presidential election in March 2022 (Kang and Ki, 2022).

The Moon administration provided several justifications for its nuclear phase-out policy, one of which was that it reflected a global trend. In his speech at the ceremony commemorating the permanent closure of the Kori-1 reactor in Busan on June 19, 2017, Moon explicitly stated that “[W]estern developed countries are rapidly reducing their dependence on nuclear power and declaring nuclear phase-out. … Nuclear phase-out is an irreversible trend of the times.”Footnote 5 The government also cited the nuclear phase-out policies of several countries, including Taiwan and the Organization for Economic Co-operation Development (OECD) member countries, as additional evidence to support its decision (e.g., Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism 2017). However, conservative news media and PPP politicians presented evidence to counter the claim that the nuclear phase-out policy reflects a global trend. In this context, information about the global trend of nuclear power generation has become highly politicized, leading to the spread of misleading information laden with partisan motivations in South Korea.

Since the use of nuclear energy is controversial and polarized in South Korea and worldwide (Ho and Kristiansen, 2019), the IAEA, among other governmental and scientific institutions, have suggested the importance to demystify nuclear-related rumors,Footnote 6 and there is a large amount of related misinformation or misleading information spreading online and offline.Footnote 7 This leads to a strand of literature that discusses nuclear-related misleading information and how to correct it (Ho and Kristiansen, 2019, Ho et al. 2022, Persico, 2024). However, there lacks an empirical study exploring how partisan leaning would affect how people understand a piece of misleading information and its correction. The current study could fill this gap, and the results could provide implications for other countries and on other similarly highly technical issue areas.

Survey design

Leveraging the political salience of the issue, we conducted an online survey from September 9 to 13 in 2022. At the beginning of the survey, all participants agreed to informed consent. We asked the participants about their gender, interest in and familiarity with nuclear power policy, and information-sharing habits. We then asked participants about their beliefs regarding misleading information about nuclear power policy. We used the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) projections for nuclear power use in 2050, which was published and circulated in 2021, to construct a pair of misleading pieces of information. The IAEA projections include two different scenarios: in the high case scenario, which assumes accelerated implementation of innovative nuclear technologies, nuclear power use is expected to increase from 10% to 12% by 2050. In the low case scenario, without such an assumption, it is expected to decrease from 10% to 6% by 2050 (IAEA, 2021). We created two misleading statements, one pro-nuclear and the other anti-nuclear, by presenting only one of the two scenarios included in the IAEA projections as follows:Footnote 8

“Given the IAEA’s increased (decreased) projection for nuclear power use in 2050, the nuclear phase-out policy is against (for) the global trend in nuclear power use”.

Since misleading information “is rarely all false [because] it must seem reliable in order to effectively mislead people” (Hendricks and Vestergaard, 2019, 55), we decided to use this pair of “doctored statements” that frame, exaggerate, omit, or cherry-pick facts (see Hendricks and Vestergaard, 2019) instead of more downright false statements. Although no direct false claims are involved in the statements, they provide both biased presentations of a case and misleading conclusions, which is considered effective in misleading individuals’ perceptions of the issue (e.g., Hendricks and Vestergaard, 2019; Wardle, 2017; Wittenberg and Berinsky, 2020).

Participants were then asked to rate their belief in the statement’s truthfulness (i.e., Prior Belief) on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates complete falsehood and 100 indicates complete truth. Next, participants were asked to rate their intention to share the misleading statement with others (i.e., Prior Intention) on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates no intention to share, and 100 indicates a definite intention to share (see Supplementary Information (SI) 1). After collecting participants’ intentions to share, we provided additional details about why the statements are misleading, including the fact that the IAEA’s projections included two scenarios and that the statement they had received was therefore biased due to the omission of one of the scenarios.Footnote 9

We subsequently asked participants to reassess their judgment about the truthfulness of the misleading statement (i.e., Posterior Belief) and whether they would still share it with others (i.e., Posterior Intention). To ensure accurate responses, we presented the participants with the misleading statement they had initially received along with their previous responses. It is worthwhile noting that the before-after design adopted in this study might lead to a concern that respondents may not want to change their beliefs and sharing intentions in order to maintain consistency in their responses. This is indeed a possible scenario although Clifford et al. (2021) suggest that it is not probable. Moreover, in such a case, it would be more difficult for us to observe the effect of corrections. The fact that we uncovered changes in beliefs and intentions in this rather conservative setting demonstrates that the effect of corrections is quite substantial.

Lastly, we asked the participants about their regions of residence, age, and level of education. Note that, to avoid any priming effects caused by asking about the participants’ party identification, we inquired about their party identification and its intensity after they answered the questions about their beliefs and intentions to share misleading information. Finally, the respondents were debriefed at the end of the questionnaire (for the descriptive statistics of the covariates, see SI 1). Figure 2 summarizes the sequence of our survey design.

We obtained a total of 1776 responses. Participants received 1 US dollar for 10 min of participation. The average duration of the interviews in our survey was 11.5 min, with a median time of approximately 8.5 min. Out of these individuals, 889 were presented with the pro-nuclear statement, while 887 received the anti-nuclear statement on a random basis.

Main dependent variables

We are primarily interested in Belief Correction and Intention Correction. The Belief Correction variable captures how participants change their beliefs after the correction. This variable is used as a dependent variable to test H1 but as an independent variable to test H2. We constructed this variable by subtracting participants’ belief ratings after the correction (i.e., Posterior Belief) from their belief ratings before the correction (i.e., Prior Belief). This variable ranges from −100 to 100. A positive value indicates that participants correctly change their beliefs, with a more positive value indicating a greater degree of belief correction. A negative value indicates the “backfire” effect such that participants change their beliefs incorrectly after the correction (see Nyhan and Reifler, 2010), with a more negative value indicating a greater degree of the backfire effect. The Intention Correction variable reflects how participants change their intention to share after the correction. We constructed this variable in the same way as that for Belief Correction. Thus, a positive (negative) value of this variable indicates a decrease (increase) in participants’ intention to share after fact-checking, with a more positive (negative) value indicating a greater (lesser) degree of behavioral correction.

Main independent variable

The independent variable of primary interest is individuals’ partisan attitudes toward the piece of misleading information, which is labeled as Attitude. Although it is difficult to manipulate the partisan identifications of individuals, it is possible to manipulate each individual’s partisan attitude by exposing one of the two misleading statements to each individual. That is, we constructed an Attitude variable that indicates whether the misleading information contradicts or is consistent with a participant’s partisan position on nuclear power policy. Specifically, this variable is assigned a value of “counter-attitudinal” for PPP (DP) supporters presented with the anti-nuclear (pro-nuclear) statement, while a value of “pro-attitudinal” is assigned for PPP (DP) supporters presented with the pro-nuclear (anti-nuclear) statement. By doing so, we obtained a total of 497 counter-attitudinal and 453 pro-attitudinal individuals. A total of 826 independent voters, who serve as a control group, are recorded as “neutral” for this variable, as it is assumed that their opinions on the issue are not systemically influenced by partisan attitudes. Therefore, we can capture the effect of partisan attitudes by comparing the counter-attitudinal/pro-attitudinal groups and the neutral group.

Our construction of the main independent variable relies on the two assumptions. First, nuclear power policy must be sufficiently partisan to activate individuals’ partisan attitudes during individuals’ belief formation. Although nuclear power policy is politically salient and a partisan issue in South Korea as aforementioned, we checked whether the participants viewed the nuclear power policy as a partisan issue by comparing the means of Prior Belief across the three attitudinal groups. If participants consider the nuclear power policy to be partisan, the pro-attitudinal group is expected to have the highest mean for Prior Belief and the counter-attitudinal group to have the lowest mean. Table 1, which presents the descriptive statistics of Belief Correction and Intention Correction by participants’ attitudes toward the misleading information, exhibited the expected pattern. The mean differences between each group were statistically significant (i.e., p < 0.001 and t = 10.996 between the pro-attitudinal and counter-attitudinal groups; p < 0.001 and t = 6.704 between the pro-attitudinal and neutral groups; p < 0.001 and t = −6.298 between the counter-attitudinal and neutral groups).

Second, independents are assumed to have a neutral attitude. This assumption does not mean that they do not have preexisting beliefs about the policy based on their pro- or counter-attitudes. Instead, the correct understanding of the assumption is that, in aggregate, there is no systematic slant in their beliefs stemming from their partisan attitudes. However, it is possible that independent participants can be “partisans in disguise” (Klar and Krupnikov, 2016) that they conceal their partisanship when asked to report. This potential pitfall is avoided if partisans in disguise are balanced between both parties because the directions of the beliefs stemming from each partisan attitude are opposite, which cancels out the bias. Table 1 shows that there is no evidence to suspect that partisans on one side are more likely to be partisans in disguise than the other. The mean of Prior Belief for the neutral group (i.e., independents) is between the partisan groups (i.e., counter- and pro-attitudinal groups), and the distances between each partisan group are almost the same (i.e., 9.03 between the neutral and counter-attitudinal group, and 9.34 between the neutral and pro-attitudinal group).Footnote 10 This suggests that, at least, partisans in disguise are well-balanced between the two parties even if we consider that all independents are partisans in disguise. Moreover, the mean of the neutral group’s Prior Intention is lower than those of counter- and pro-attitudinal groups, which is consistent with the characteristics of independents that they are less likely than partisans to engage in political behaviors including sharing information about a politically salient issue (see Weeks et al. 2017).

Results

Partisan attitudes and belief correction

We begin by testing H1 through evaluation of H1a (resistance effect) and H1b (facilitation effect). To test both H1a and H1b, we conducted an OLS regression analysis with robust standard errors to account for heteroskedasticity. The dependent variable, Belief Correction, was standardized to enhance the substantive interpretation of the coefficients. The main independent variable is Attitude. Specifically, we estimated the following Eq. (1) where ProAttitude and CounterAttitude indicate the type of treatment:

If a respondent \({i}\) is assigned to a statement that is consistent (resp. inconsistent) with her partisan preference, then\({ProAttitud}{e}_{i}=1\) and \(C{ounterAttitud}{e}_{i}=0\,\)(resp. \({ProAttitud}{e}_{i}=0\) and \(C{ounterAttitud}{e}_{i}=1\)). If a respondent \(i\) is in a neutral position, then both ProAttitudei and CounterAttitudei take the value of 0. In addition, Xi is the matrix of the control variables, including the respondent’s interest in and familiarity with the nuclear energy issue, gender, education level, age, and place of residence.Footnote 11 The parameter of primary interest is β1, and we want to test whether β1 < 0, i.e., respondents are less likely to correct their beliefs when the misleading information they received is consistent with their partisan preference.

As shown in Table 1, counter-attitudinal participants rate their prior beliefs quite low compared to pro-attitudinal and neutral participants, which consequently leads them to change their prior beliefs less or even show “backfire” compared to the other groups. This is because the counter-attitudinal participants already believe that misleading information is not true, so they are less likely to rectify their already correct beliefs. To remove this bias embedded in Attitude, we controlled for participants’ prior beliefs about the misleading statement (i.e., Prior Belief).Footnote 12 Thus, Attitude captures the effects of their partisan position on belief correction given the same level of prior belief about misleading information. We also included several covariates, such as participants’ demographic background (sex, age, region of residence, level of education), and their level of interest in and familiarity with the issue of nuclear power policy.Footnote 13

Our results provide evidence for the resistance effect (i.e., H1a) but do not support the facilitation effect (i.e., H1b) (see Model 1 of Table 2.1 in SI 2), which supports H1. As Fig. 3 shows, individuals who received pro-attitudinal misleading information are less likely to correct their beliefs compared to the neutral group by 3.097 (p = 0.018, t = −2.362), which is also equivalent to 0.12 standard deviations. While the magnitude of the effect is modest, it is substantively non-negligible and provides support for the resistance effect. In contrast, we find no evidence that counter-attitudinal participants would correct their beliefs more than neutral participants. Not only is the estimated coefficient for the counter-attitudinal group negative, contradicting the predicted direction of the facilitation effect, but the estimate is also not significant (p = 0.175, t = −1.358).

Alternatively, we created a dummy variable D-Pro (D for dummy) that assigned a value of 1 to the pro-attitudinal group and 0 to the non-pro-attitudinal group (i.e., the counter-attitudinal and neutral groups). We then substituted it for Attitude in our model to ascertain whether the finding on the resistance effect is driven by the specific design of the original variable. While the resistance effect in standard deviations, 0.096, slightly decreases, the regression coefficient for the new dummy variable remains statistically significant (p = 0.048, t = −1.975), which means that the pro-attitudinal group is less likely to correct their beliefs than the non-pro-attitudinal group (see Model 2 of Table 2.1 in SI 2). Taken altogether, our results confirm H1 that individuals’ partisan attitudes affect their belief correction by causing them to resist correcting their erroneous beliefs congruent with their partisan positions.

Partisan attitudes, belief correction, and intention correction

While belief correction may lead individuals to correct their sharing intentions, partisan attitudes may still lead individuals to share pro-attitudinal misleading information. Specifically, on the one hand, H2 states an indirect way in which partisan attitudes might hinder pro-attitudinal voters’ correction of sharing intention by interfering with their belief correction. On the other hand, H3 states that partisan attitudes might directly obstruct pro-attitudinal voters’ correction of sharing intention independent of their belief correction. The verification of H2 would be evidence that partisan attitudes contribute to the spread of misleading information based on mistaken belief. The verification of H3, by contrast, would be evidence that partisan attitudes motivate individuals to spread misleading information regardless of their beliefs.

To test H2 and H3, we estimated another linear model by OLS, this time using Intention Correction as the dependent variable. The primary independent variables are Attitude and Belief Correction. Attitude now captures the direct effect of partisan attitudes that motivate individuals to spread misleading information regardless of their beliefs, which widens the gap between belief correction and intention correction. On the other hand, Belief Correction captures the indirect effect of partisan attitudes on the dissemination of misleading information based on mistaken belief. In addition, the fact that pro-attitudinal participants tend to have greater prior intentions to share misleading information than counter-attitudinal and neutral participants, as shown in Table 1, suggests that we need to control for Prior Intention as we did for Prior Belief in the foregoing analysis. We also added the Frequency variable, which measures how frequently participants share content on social media in their daily lives, as a control for their information-sharing habits. The set of control variables used for belief correction was also included. As a result, we estimated the following Eq. (2) with \({X}_{i}\), including the control variables introduced above:

We found that Belief Correction is positively associated with Intention Correction, which means that correcting mistaken beliefs facilitates individuals’ correction of their intention to share misleading information regardless of their partisan attitudes. Figure 4 illustrates that one standard deviation change in Belief Correction is associated with a 0.145 standard deviation increase in (p < 0.001, t = 4.915). Therefore, we obtained supporting evidence for H2. However, our analysis provides no evidence that partisan attitudes directly motivate individuals to spread misleading information (see Model 3 of Table 2.2 in SI 2). As shown in Fig. 4, the standardized coefficient of Attitude for the pro-attitudinal group is insignificant and essentially zero (p = 0.859, t = −0.177). This means that pro-attitudinal individuals’ intention to share misleading information is indistinguishable from that of independent voters, who do not have such partisan attitudes.

We also found no evidence that the counter-attitudinal group is more likely to correct their sharing intentions than the neutral group. As shown in Fig. 4, the estimated coefficient is substantively or statistically insignificant, as the point estimate is not significant at even the one standard error confidence level (p = 0.678, t = −0.416). We also re-ran the regression model with D-Pro instead of Attitude. The results from this new model are consistent with our findings. The direction of the standardized coefficient for Belief Correction is consistent with H2 (i.e., 0.146) and statistically significant (p < 0.001, t = 5.041). However, the standardized coefficient for D-Pro not only fails to reach statistical significance (p = 0.987, t = −0.016) but is also practically equal to zero (see Model 4 of Table 2.2 in SI 2).

In summary, our findings confirm H2 while rejecting H3, suggesting that partisan attitudes contribute to amplifying the dissemination of misleading information primarily by impeding the development of accurate beliefs, as opposed to directly disconnecting behaviors from beliefs. Our findings reveal that partisan attitudes contribute to the spread of misleading information by hindering belief correction, but we do not find evidence supporting the idea that these attitudes cause individuals to disseminate misleading information by widening the gap between belief and behavior.

Robustness check: discrete measures

The main results reported above are based on our continuous measures of Belief Correction and Intention Correction. Some readers may question the substantiality of the results because the changes in the continuous variables may not necessarily capture the qualitative changes in beliefs and sharing intentions. For example, a change in an individual’s belief from 100 to 80, which suggests that the individual still believes the misleading statement is leaning toward truth, is qualitatively different from the same amount of change from 60 to 40, which now indicates that the individual is qualitatively changing her beliefs from “true” to “false”. To address this issue, we employed a modified coding scheme of Belief Correction and Intention Correction to see if we would reach the same conclusion.

For the Prior Belief and Posterior Belief variables, the participants were asked to indicate whether they believed the misleading statement to be either “true” (=2), “don’t know” (=1), or “false” (=0). We then assigned Belief Correction a value of 2 for those who changed their belief from “true” or “don’t know” to “false,” 1 for those who changed from “true” to “don’t know,” −1 for those who changed from “don’t know” to “true,” −2 for those who changed from “false” to “don’t know” or “true,” and 0 for those who maintained the same responses. This ensures that Belief Correction captures qualitative changes in individuals’ beliefs. Similarly, for Prior Intention and Posterior Intention, participants were asked to indicate whether they wanted to either “share” (=1) or “not share” (=0). We assigned Intention Correction a value of 1 for those who changed their responses from “share” to “not share,” −1 for those who changed from “not share” to “share,” and 0 otherwise (see SI 1). The standardized versions of these variables are used in the OLS estimations.

With these new measures, we conducted the OLS regression analyses with robust standard errors. As shown in the left panels of Fig. 5, all estimated standardized coefficients follow the same pattern as demonstrated in Figs. 3 and 4, which indicates that the results are not qualitatively different from the main results reported (see Models 5 and 7 of Tables 3.1 and 3.2 in SI 3). We also conducted ordered logistic regression analyses and came to the same conclusion (see Models 6 and 8 of Tables 3.1 and 3.2 in SI 3). As shown in the right panels of Fig. 5, the directions and statistical significance of the variables of interest remain the same.

Finally, using the continuous measure of partisan attitudes, we tested if individuals with more intense partisan identities are more likely to believe misleading information congruent with their partisan positions to be true and less likely to correct their beliefs and sharing intentions (see An, Quericia, and Crowcroft 2017). We found no evidence (see SI 4). In conclusion, these results suggest that our findings are robust against the alternative measures.

Discussion and conclusion

In this research, we examine whether the spreading of misleading information is driven by the gap between beliefs and behaviors. We first replicate the empirical regularity that has been established in the literature with our survey experiment in South Korea: partisan attitudes affect individuals’ belief correction, which, in turn, impacts their correction of intentions to share misleading information. However, after partialling out the direct effect of belief correction on sharing intention, we find no evidence that partisan attitudes directly drive individuals to spread misleading information. Our findings, which are robust with different coding strategies of partisan attitudes, therefore suggest that partisan attitudes aggravate the spread of misleading information by hindering belief correction, not by widening the gap between belief and behavior, which is the main theoretical contribution from our finding.Footnote 14

Our study thus provides a key policy implication: mitigating the influence of partisan attitudes on belief correction is essential to curbing the spread of misleading information. Addressing this challenge requires considering both the supply and demand sides of misinformation. On the supply side, strengthening debunking strategies—such as fact-checking and balanced reporting—can help individuals more easily recognize misleading content. On the demand side, it is crucial to reduce affective polarization that drives individuals to reject neutral and factual information (Schmitt et al. 2004; Tsfati, 2007). Therefore, policymakers, journalists, and social media platforms need to go beyond mere debunking efforts, focusing on reducing outgroup animosity. This can be achieved by exposing individuals to diverse viewpoints, promoting empathetic engagement with opposing perspectives, reducing amplification of divisive contents, and facilitating cross-partisan conversations and dialogues.

It is important to consider three caveats in the interpretation of findings. Firstly, we did not explicitly define the intended recipients of the misleading information shared by our participants. Given the tendency for individuals to interact predominantly with like-minded individuals, it is reasonable to speculate that most respondents likely targeted their fellow co-partisans when sharing information. As such, the motivation to spread misinformation to deceive may be weak. However, if we were to specifically identify out-partisans (and/or independents) as the intended targets, different results may arise. This is because partisan voters would now have an incentive to spread disinformation in order to deceive those who hold opposing opinions.

Second, changes in individuals’ intentions do not necessarily mean changes in their actual behaviors, as suggested by the “intention-behavior gap” (Ecker et al. 2022; Sheeran and Webb, 2016). For example, an individual’s information-sharing habit may be one source that disconnects behavior from intention, given that Frequency turned out to be a strong predictor of the correction of sharing intention (see Tables 2.2 and 3.2 in SI 2 and 3). While Mosleh et al. (2020) presented evidence suggesting a correlation between sharing intentions and actual sharing behavior, it is crucial to remain mindful of the potential disparity that may exist between intentions and actions.

Third, while our findings indicate little evidence of partisan bias in the correction of sharing behavior, this result may be due to our research design not incorporating the dynamic nature of partisanship during the election cycle. As partisanship fluctuates during an election cycle (Michelitch and Utych, 2018; Singh and Thornton, 2019), it significantly influences voters’ decisions, resulting in an increased in-party bias in their behavior around election times (Michelitch, 2015; Sheffer, 2020). Our survey was conducted in September 2022, six months after the 2022 presidential election, a period when the salience of partisanship was likely waning. Therefore, the reduced salience of partisan identities at the time of our survey potentially explains the absence of evidence of partisan bias in behavior correction.

There are two avenues for future research. First, our finding that fact-checking does not substantially correct the sharing intention on average (see Table 1) may suggest that, in addition to partisan attitudes obstructing belief correction directly and intention correction indirectly, there may also be a psychological barrier that hinders the correction of intentions. One possibility is that individuals strive to maintain internal consistency between their beliefs and behavioral intentions. The negative effect of Familiarity on the correction of sharing intentions — though statistically significant only with discrete measures (see Models 7 and 8 in Table 3.2, SI 3) — offers suggestive evidence of it. A high level of familiarity with the issue or a committed perception regarding a particular argument may lead individuals to be confident in their initial beliefs, thereby reinforcing a consistency bias (Ahluwalia, 2000). This enhanced consistency bias, in turn, may escalate individuals’ commitment to a failing course of action (Brockner, 1992; Staw, 1981) to avoid appearing inconsistent or admitting that their beliefs are wrong. Investigating this cognitive bias as a source of sticky behavior would be an avenue for future research.

Second, we constructed misleading information by creating biased statements and attempted to correct them by providing balanced information in our survey. While this was inconclusive, we observed that the counter-attitudinal group (and to a lesser extent the neutral group as well) came to believe the misleading statement to be more truthful and were more willing to share the misleading statement after the correction, although the mean intention ratings are still much lower compared to that of the pro-attitudinal group (see Table 1). This observation probably suggests that they may have believed that the misleading statement they believed to be false was in fact partially true, leading them to be more willing to share the “partially true” statement. This echoes the warning that balanced reporting may confuse audiences as it may mislead them to think there is no definite truth (see Boykoff and Boykoff, 2004; Dixon and Clarke, 2013; Merkley, 2020). Given that balanced reporting is an approach commonly employed by fact-checkers, further research could explore its potential unintended effects.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during the current study and the replication codes are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YYU0N9.

Notes

What we call “belief” here follows the conventional usage in the literature which means a level of trust in a piece of information, and by “correction” we mean the process that an individual update their beliefs in a piece of misinformation upon receiving fact-checking or clarification messages (see, for example, Berinsky, 2017, Nyhan, 2020, and Pennycook and Rand, 2021).

We remain agnostic about which theoretical mechanism holds greater explanatory power, as it lies beyond the scope of this study, so long as the two theoretical mechanisms yield the same hypothesis.

Our survey data also reveals a pronounced partisan divide regarding support for South Korea’s nuclear phase-out policy. Participants were asked to rate their level of support or opposition on a scale from 0 to 100, where 0 represents complete opposition and 100 represents complete support, prior to identifying their partisan affiliation. The mean score among People Power Party (PPP) supporters was 33.25 (95% CI: [30.08, 36.41]), while Democratic Party (DP) supporters had a mean score of 67.65 (95% CI: [65.58, 69.72]). Independents reported a mean score of 49.74 (95% CI: [46.79, 52.69]). These differences in mean scores are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level, which suggests that nuclear phase-out policy is a partisan issue in South Korea.

In April 2025, President Yoon Suk-Yeol was removed from office following the Constitutional Court of Korea’s decision to uphold his impeachment by the National Assembly. The impeachment was triggered by his unconstitutional declaration of martial law in December 2024.

The full text in Korean is available at https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20170619071500001.

See, for example, the following webpages: “Addressing the challenges of misinformation” (Nuclear Energy Agency 2021) https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_62435/addressing-the-challenges-of-misinformation and “Let’s Talk About Nuclear Security: National Perspectives on the Importance of Public Communication” (IAEA 2024) https://www.iaea.org/bulletin/lets-talk-about-nuclear-security.

Here is a collection of myths related to nuclear energy and their clarifications provided by Argonne National Laboratory, a research center owned by the Department of Energy of the United States: https://www.anl.gov/article/10-myths-about-nuclear-energy.

Since the survey participants may perceive the IAEA as a pro-nuclear agency, this could introduce idiosyncratic effects on their evaluations of pro-nuclear or anti-nuclear misleading statements. However, our treatment focuses not on the direction of the misleading statements themselves but rather on participants’ partisan attitudes toward these statements. The treatment and control groups are composed of both participants exposed to the pro-nuclear and anti-nuclear statements, ensuring a balanced composition. This balance minimizes the impact of any idiosyncratic effect related to perceptions of the IAEA.

The provision of details is one of the widely used ways to correct mistaken beliefs stemming from misleading information, and its effectiveness has been confirmed in many studies (e.g., Chan and Albarracín, 2023; Ecker et al. 2023; Ecker et al. 2020; van der Meer and Jin, 2020). The script is presented in SI 6.

Table 1 shows that the mean of the neutral group’s Prior Belief is 55.13 (55.50 and 54.75 for the neutral group received the pro-nuclear statement and the anti-nuclear statement, respectively).

The full estimation results are presented in Table 2.1 in SI 2.

It is also necessary to control for Prior Belief of our control group, whose prior beliefs are assumed to be uninfluenced by partisan attitudes, in order to isolate and accurately measure the impact of partisan attitudes on belief correction.

Although we do not introduce control variables in detail throughout this paper to save space, interested readers can refer to the full regression tables in SI for details on these variables.

Of course, we cannot entirely rule out the possibility that the absence of a gap between belief and behavior may be partly attributed to social desirability bias. However, we believe this likelihood is minimal, as our survey was conducted in a non-face-to-face setting with participants’ anonymity fully ensured.

References

Ahluwalia R (2000) Examination of psychological processes underlying resistance to persuasion. J Consum Res 27(2):217–232

Allen J, Watts DJ, Rand DG (2024) Quantifying the impact of misinformation and vaccine-skeptical content on Facebook. Science 384(6699):eadk3451

Alsaad AK (2021) Ethical judgment, subjective norms, and ethical consumption: The moderating role of moral certainty. J Retail Consum Serv 59:102380

An J, Quericia D, Crowcroft J (2017) Partisan sharing: facebook evidence and societal consequences. Procceedings of the Second ACM Conference on Online Social Networks: 13–24

Apuke OD, Omar B (2021) Fake news and COVID-19: Modelling the predictors of fake news sharing among social media users. Telemat Inform 56:101475

Badrinathan S (2021) Educative interventions to combat misinformation: Evidence from a field experiment in India. Am Polit Sci Rev 115(4):1325–1341

Berinsky AJ (2017) Rumors and health care reform: Experiments in political misinformation. Br J Polit Sci 47(2):241–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000186

Boykoff MT, Boykoff JM (2004) Balance as bias: Global warming and the US prestige press. Glob Environ Change 14(2):125–136

Bright J (2016) The social news gap: How news reading and news sharing diverge. J Commun 66(3):343–365

Briñol P, Petty RE (2009) Source factors in persuasion: A self-validation approach. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 20(1):49–96

Brockner J (1992) The escalation of commitment to a failing course of action: Toward theoretical progress. Acad Manage Rev 17(1):39–61

Carnahan D, Bergan DB (2022) Correcting the misinformed: The effectiveness of fact-checking messages in changing false beliefs. Polit Commun 39(2):166–183

Chan MPS, Albarracín D (2023) A meta-analysis of correction effects in science-relevant misinformation. Nat Hum Behav 7:1514–1525

Clifford S, Sheagley G, Piston S (2021) Increasing precision without altering treatment effects: Repeated measures designs in survey experiments. Am Polit Sci Rev 115(3):1048–1065

Cohen GL (2003) Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. J Pers Soc Psychol 85(5):808–822

Dixon GN, Clarke CE (2013) Heightening uncertainty around certain science: Media coverage, false balance, and the autism-vaccine controversy. Sci Commun 35(3):358–382

Dong X, Jiang B, Zeng H, Kassoh FS (2022) Impact of trust and knowledge in the food chain on motivation-behavior gap in green consumption. J Retail Consum Serv 66:102955

Dunne Á, Lawlor MA, Rowley J (2010) Young people’s use of online social networking sites: A uses and gratifications perspective. J Res Interact Mark 4(1):46–58

Echegaray F, Hansstein FV (2017) Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: The case of Brazil. J Clean Prod 142(1):180–190

Ecker UKH, Sharkey CXM, Swire-Thompson B (2023) Correcting vaccine misinformation: A failure to replicate familiarity or fear-driven backfire effects. PLoS ONE 18(4):e0281140

Ecker UKH, O’Reilly Z, Reid JS, Chang EP (2020) The effectiveness of short-format refutational fact-checks. Br J Psychol 111(1):36–54

Ecker UKH, Lewandowsky S, Cook J, Schmid P, Fazio LK, Brashier N, Kendeou P, Vraga EK, Amazeen MA (2022) The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat Rev Psychol 1:13–29

Flynn DJ, Nyhan B, Reifler J (2017) The nature and origins of misperceptions: Understanding false and unsupported beliefs about politics. Adv Polit Psychol 38(51):127–150

Gaines BJ, Kuklinski JH, Quirk PJ, Peyton B, Verkuilen J (2007) Same facts, different interpretations: Partisan motivation and opinion on Iraq. J Polit 69(4):957–974

Hendricks VF, Vestergaard M (2019) Reality lost: Markets of Attention, Misinformation and Manipulation. Springer Open, Cham

Ho SS, Kristiansen S (2019) Environmental debates over nuclear energy: Media, communication, and the public. Environ Commun 13(4):431–439

Ho SS, Chuah ASF, Kim N, Tandoc Jr EC (2022) Fake news, real risks: How online discussion and sources of fact-check influence public risk perceptions toward nuclear energy. Risk Anal 42(11):2569–2583

Hogg MA, Reid SA (2006) Social identity, self-categorization, and the communication of group norms. Commun Theory 16(1):7–30

IAEA (2021) Energy, electricity and nuclear power estimates for the period up to 2050, IAEA Reference Data Series No 1. IAEA, Vienna

IAEA (2024) Country nuclear power profiles 2024 edition: Republic of Korea. IAEA, Vienna. https://cnpp.iaea.org/public/countries/KR/profile/preview. Accessed 28 May 2025

Jordan JJ, Rand DG (2020) Signaling when no one is watching: A reputation heuristics account of outrage and punishment in one-shot anonymous interactions. J Pers Soc Psychol 118(1):57–88

Kang M, Ki Y (2022) Yangdae seongeo yugwonja jeongchaek tupyo pyeongga mithyeobryeok bang-an (Evaluation of policy voting in the 2022 Korean presidential and local elections: Policy suggestions). In: Korean Political Science Association (ed) 2022nyeondo Jungang seongeo gwanli wiwonhoe yeongu yongyeok gyeolgwa bogoseo (External evaluations of the 2022 South Korean presidential election and local elections) pp 333-379. National Election Commission of the Republic of Korea, Gwacheon

Kelleher DS (2022) Trusting is believing: Public deliberation on nuclear facilities in South Korea. Energy Res Soc Sci 89:102540

Khan S, Abbas M (2023) Interactive effects of consumers’ ethical beliefs and authenticity on ethical consumption and pro-environmental behaviors. J Retail Consum Serv 71:103226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103226

Klar S, Krupnikov Y (2016) Independent politics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kraft PW, Lodge M, Taber CS (2015) Why people ‘don’t trust the evidence’: Motivated reasoning and scientific beliefs. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 658(1):121–133

Langenbach BP, Berger S, Baumgartner T, Knoch D (2020) Cognitive resources moderate the relationship between pro-environmental attitudes and green behavior. Environ Behav 52(9):979–995

Lee CS, Ma L (2012) News sharing in social media: The effect of gratifications and prior experience. Comput Hum Behav 28(2):331–339

Lee E-J, Jang J-W (2023) How political identity and misinformation priming affect truth judgments and sharing intention of partisan news. Digit J 11(1):226–245

Lee S-J (2017) Talwonjeon jeongchaek ‘chanseong’ 60.5% vs ‘bandae’ 29.5% (Nuclear phase-out policy: ‘Approve’ 60.5% vs. ‘Disapprove’ 29.5%). Hankyoreh, Seoul. https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/politics/politics_general/815587.html. Accessed 28 May 2025

Leonard KC, Scott-Jones D (2010) A belief-behavior Gap? Exploring religiosity and sexual activity among high school seniors. J Adolesc Res 25(4):578–600

Ma WWK, Chan A (2014) Knowledge sharing and social media: Altruism, perceived online attachment motivation, and perceived online relationship commitment. Comput Hum Behav 39:51–58

Mackie DM, Worth LT, Asuncion AG (1990) Processing of persuasive in-group messages. J Pers Soc Psychol 58(5):812–822

Mahardika H, Thomas D, Ewing MT, Japutra A (2020) Comparing the temporal stability of behavioural expectation and behavioural intention in the prediction of consumers pro-environmental behaviour. J Retail Consum Serv 54:101943

McCurry J (2019) New South Korean president vows to end use of nuclear power. The Guardian, London. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/19/new-south-korean-president-vows-to-end-use-of-nuclear-power. Accessed 28 May 2025

Merkley E (2020) Are experts (news)worthy? Balance, conflict, and mass media coverage of expert consensus. Polit Commun 37(4):530–549

Michelitch K (2015) Does electoral competition exacerbate interethnic or inter-partisan economic discrimination? Evidence from a field experiment in market price bargaining. Am Polit Sci Rev 109(1):43–61

Michelitch K, Utych S (2018) Electoral cycle fluctuations in partisanship: Global evidence from eighty-six countries. J Polit 80(2):412–427

Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism (2017) Wonjeon-gwa Talwonjeon, segyejeok chuse-neun eoneu jjog-ilkka (Nuclear Power or Phase-Out: What Is the Global Trend?) MCST, Sejong. https://www.korea.kr/briefing/policyBriefingView.do?newsId=148840067. Accessed 28 May 2025

Mosleh M, Pennycook G, Rand DG (2020) Self-reported willingness to share political news articles in online surveys correlates with actual sharing on Twitter. PLoS ONE 15(2):e0228882

Nguyen VP (2019) An analysis of Moon Jae-in’s nuclear phase-out policy: The past, present, and future of nuclear energy in South Korea. Georgetown J Asian Aff Winter 66–72

Nuclear Energy Agency (2021) Addressing the challenges of misinformation. Nuclear Energy Agency, Paris. https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_62435/addressing-the-challenges-of-misinformation. Accessed 28 May 2025

Nyhan B (2020) Facts and myths about misperceptions. J Econ Perspect 34(3):220–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.34.3.220

Nyhan B (2021) Why the backfire effect does not explain the durability of political misperceptions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118(15):e1912440117

Nyhan B, Reifler J (2010) When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions. Polit Behav 32:303–330

Osmundsen M, Bor A, Vahlstrup P, Bechmann A, Petersen M (2021) Partisan polarization is the primary psychological motivation behind political fake news sharing on Twitter. Am Polit Sci Rev 115(3):999–1015

Park H, Blenkinsopp J (2009) Whistleblowing as planned behavior: A survey of South Korean police officers. J Bus Ethics 85:545–556

Pennycook G, Rand DG (2021) The psychology of fake news. Trends Cogn Sci 25(5):388–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.02.007

Pennycook G, Epstein Z, Mosleh M, Arechar AA, Eckles D, Rand DG (2021) Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature 592:590–595

Pereira FB, Bueno NS, Nunes F, Pavão N (2022) Fake news, fact checking, and partisanship: The resilience of rumors in the 2018 Brazilian elections. J Polit 84(4):2188–2201

Persico S (2024) Affective, defective, and infective narratives on social media about nuclear energy and atomic conflict during the 2022 Italian electoral campaign. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11:245

Peterson E, Iyengar S (2021) Partisan gaps in political information and Information-seeking behavior: Motivated reasoning or cheerleading? Am J Polit Sci 65(1):133–147

Plume CJ, Slade EL (2018) Sharing of sponsored advertisements on social media: A uses and gratifications perspective. Inf Syst Front 20:471–483

Scheufele DA, Krause NM (2019) Science audiences, misinformation, and fake news. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116(16):7662–7669

Schmitt KM, Gunther AC, Liebhart JL (2004) Why partisan sees mass media as biased. Commun Res 31(6):623–641

Sheeran P, Webb TL (2016) The intention–behavior gap. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 10(9):503–518

Sheffer L (2020) Partisan in-group bias before and after elections. Elect Stud 67:102191

Shin J, Thorson K (2017) Partisan selective sharing: The biased diffusion of fact-checking messages on social media. J Commun 67(2):233–255

Singer JB (2014) User-generated visibility: Secondary gatekeeping in a shared media space. New Media Soc 16(1):55–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813477833

Singh SP, Thornton JR (2019) Elections activate partisanship across countries. Am Polit Sci Rev 113(1):248–253. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000722

Staw BM (1981) The escalation of commitment to a course of action. Acad Manage Rev 6(4):577–587

Su M-H, Liu J, McLeod DM (2019) Pathways to news sharing: Issue frame perceptions and the likelihood of sharing. Comput Hum Behav 91:201–210

Susmann MW, Wegener DT (2022) The role of discomfort in the continued influence effect of misinformation. Mem Cognit 50:435–448

Taber CS, Lodge M (2006) Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. Am J Polit Sci 50(3):755–769

Taber CS, Cann D, Kucsova S (2009) The motivated processing of political arguments. Polit Behav 31:137–155

Tandoc Jr EC, Ling R, Westlund O, Duffy A, Goh D, Wei LZ (2018) Audiences’ acts of authentication in the age of fake news: A conceptual framework. New Media Soc 20(8):2745–2763

Tsfati Y (2007) Hostile media perceptions, presumed media influence, and minority alienation: The case of Arabs in Israel. J Commun 57(4):632–651

Turner JC (1987) Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Blackwell, New York

Van Bavel JJ, Pereira A (2018) The partisan brain: An identity-based model of political belief. Trends Cogn Sci 22(3):213–224

van der Meer TGLA, Jin Y (2020) Seeking formula for misinformation treatment in public health crises: The effects of corrective information type and source. Health Commun 35(5):560–575

Walter N, Murphy ST (2018) How to unring the bell: A meta-analytic approach to correction of misinformation. Commun Monogr 85(3):423–441

Walter N, Tukachinsky R (2020) A Meta-analytic examination of the continued influence of misinformation in the face of correction: How powerful is it, why does it happen, and how to stop it? Commun Res 47(2):155–177

Wardle C (2017) Fake news. It’s complicated. First Draft. https://medium.com/1st-draft/fake-news-its-complicated-d0f773766c79. Accessed 28 May 2025

Weeks BE, Lane DS, Kim DH, Lee SS, Kwak N (2017) Incidental exposure, selective exposure, and political information sharing: Integrating online exposure patterns and expression on social media. J Comput-Mediat Commun 22(6):363–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12199

Wittenberg C, Berinsky AJ (2020) Misinformation and its correction. In Persily N, Tucker JA (eds) Social media and democracy: The state of the field, prospects for reform. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Yaqub W, Kakihdze O, Brockman ML, Memon N, Patil S (2020) Effects of credibility indicators on social media news sharing intent. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems

Acknowledgements

We thank the panel participants at the 2023 World Congress for Korean Politics and Society, especially Brandon Park, and seminar participants at the Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica, for their invaluable comments and advice. This study was financially supported by Research Project Grants from the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (NSTC 110-2410-H-001-100-MY3 and NSTC 113-2628-H-001-015-MY3) and Academia Sinica Grand Challenge Program Seed Grant (AS-GCS-113-H03). All remaining errors are the authors’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the research, wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at National Cheng Kung University (NCKU HREC), Taiwan. The approval number is NCKU HREC-E-110-476-2. It was approved on Apr. 18, 2022. The research design and execution were performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines for ensuring that the rights and welfare of research participants are adequately protected, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

We obtained informed consent from each respondent upon their arrival of the survey portal, and before they started answering the survey questionnaire by clicking “agree” to the statement concerning voluntary participation, data protection, anonymity, use of data, and compensation for participation. The informed consent statement was reviewed and approved by the by the Human Research Ethics Committee at National Cheng Kung University (NCKU HREC) on Apr. 18, 2022.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, M., Park, C., Yoon, J. et al. Partisan attitudes and the motivation behind the spread of misleading information. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1369 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05714-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05714-x