Abstract

This mixed-methods study explores the complex relationship between parental social media disengagement, parent-teenager communication, emotional regulation, and adolescent social media addiction within the Chinese context. A total of 503 Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years (M = 15.78, SD = 1.23) participated in the quantitative phase, which utilized validated measures including the Parental Social Media Disengagement Scale (PSMDS) and the Chinese Social Media Addiction Scale (CSMAS). The study also incorporated in-depth qualitative interviews with 30 participants (15 adolescents and 15 parents) to provide a richer understanding of the phenomena. Quantitative results revealed that higher levels of parental social media disengagement were associated with lower levels of adolescent social media addiction, with parent-teenager communication and emotional regulation serving as partial mediators. Furthermore, emotional regulation moderated this relationship, indicating that adolescents with stronger emotional regulation skills experienced greater benefits from parental disengagement. Qualitative findings highlighted positive transformations in family dynamics and communication when parents reduced their social media use, emphasizing the role of parental modeling in fostering emotional resilience and healthier digital habits among adolescents. These findings highlight the importance of holistic interventions targeting family communication and emotional regulation to mitigate adolescent social media addiction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The spread of social media has greatly changed adolescent social life, offering new ways for connection and self-expression, yet also presenting notable risks (Boyd, 2008; Twenge et al. 2019; Baccarella et al. 2018; Reid and Weigle, 2014). Among these risks, social media addiction—defined by uncontrolled, compulsive use that interferes with daily activities—has become a growing concern (Andreassen, 2015; Kuss et al. 2013; Moretta et al. 2022). Many studies link this addiction to negative effects, including poorer academic performance, disrupted sleep, and increased anxiety and depression (Hou et al. 2019; Keles et al. 2020). Given how common these problems are, it is important to identify the factors that affect adolescent social media addiction.

Parental influence, long recognized as vital to adolescent development, holds particular importance for behavior regulation. Traditional studies often focus on parental supervision, such as monitoring screen time or restricting content access (Gentile et al. 2014; Sanders et al. 2016). In contrast, parental engagement involves actively participating in adolescents’ digital lives, such as discussing social media experiences or modeling healthy behaviors (Reid Chassiakos et al. 2016). This study examines a specific form of parental engagement: parental social media disengagement, where parents deliberately reduce their own social media use to encourage more meaningful face-to-face interactions. By modeling balanced media consumption and promoting real-life connections, this disengagement potentially acts as a protective factor against adolescent social media addiction (Livingstone and Helsper, 2008; Nikken, 2017; Gold, 2014).

Despite growing awareness of the indirect ways parental behavior shapes adolescent outcomes, research predominantly centers on direct interventions like screen-time limits. Less attention has been paid to the indirect influence of parents’ own digital habits on adolescent social media use, especially in non-Western contexts where familial and social norms differ significantly. Further complicating this picture, parent-teenager communication and emotional regulation may play central mediating and moderating roles. While studies show communication fosters adolescent well-being by providing guidance and emotional support (Boniel-Nissim et al. 2015; Padilla-Walker and Coyne, 2011; Reid Chassiakos et al. 2016), the specific interplay between parental disengagement, communication dynamics, and emotional regulation has not been fully investigated. Additionally, emotional regulation, the ability to manage emotional experiences in a healthy manner (Thompson, 1994), may be particularly relevant for adolescents coping with social media pressures (Schweizer et al. 2020; Liu and Ma, 2019), yet the theoretical justification for examining it as both a mediator and moderator remains underdeveloped.

This mixed-methods study examines the interplay of parental social media disengagement, parent-teenager communication, emotional regulation, and adolescent social media addiction in the Chinese cultural context, addressing key gaps in the literature. The quantitative phase tests statistical relationships among these variables, while the qualitative phase explores adolescents’ and parents’ lived experiences. Together, these approaches aim to offer contextual insights and reveal mechanisms driving outcomes, advancing understanding of indirect parental influences on adolescent digital behaviors.

The study positions emotional regulation as both a mediator—showing how parental disengagement may reduce addiction by improving self-regulation—and a moderator—identifying which adolescents benefit most from this parental behavior. Integrating emotional regulation provides a framework to assess how individual differences affect the impact of parental strategies in a culturally specific setting. Findings can guide evidence-based interventions that combine parental disengagement, family communication, and emotional regulation training to address adolescent social media addiction effectively.

Literature review

Adolescent social media addiction

Adolescent social media addiction, characterized by excessive and compulsive use that disrupts daily activities, shares core features with behavioral addictions, including mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse (Andreassen, 2015; Kuss and Griffiths, 2017). It is important to note that while “social media addiction” is a term widely used in research, it is not yet formally recognized as a distinct disorder in diagnostic manuals like the DSM-5 or ICD-11 (Al-Samarraie et al. 2022; Sun and Zhang, 2021). This absence stems from ongoing debates about whether social media use meets the stringent criteria for addiction, such as evidence of physiological dependence or severe functional impairment, which are more clearly established for substances or gaming disorder—the latter recognized in the ICD-11 (Cheng et al. 2021; World Health Organization, 2019). The conceptualization of social media addiction in this study draws on established frameworks for behavioral addictions, which emphasize compulsive engagement, loss of control, and adverse impacts on daily functioning (Andreassen, 2015; Kuss and Griffiths, 2017). For example, while gaming disorder in the ICD-11 requires persistent impaired control and significant life disruption over 12 months, our study adapts similar principles—such as preoccupation and negative consequences—to social media use, though without claiming clinical diagnostic equivalence. However, diagnosing addiction in adolescents presents unique challenges due to the developmental characteristics of this life stage, where intense social media use may sometimes reflect normative exploration rather than pathological behavior (Livingstone and Blum-Ross, 2020). Consequently, some researchers suggest that problematic social media use in adolescents may be more accurately described as compulsive or excessive behavior rather than a full addiction (Moretta et al. 2022). Here, “compulsive behavior” refers to repetitive actions driven by urges to reduce discomfort, whereas “addiction” implies a deeper loss of control and dependence (Grant et al. 2010). We adopt “social media addiction” to reflect the severity of disruption observed in our sample and to align with existing literature, while acknowledging these conceptual nuances and the need for further empirical validation. Given these complexities, our study operationalizes social media addiction based on self-reported measures of compulsive use, preoccupation, and negative consequences, as outlined in the Chinese Social Media Addiction Scale (CSMAS; Liu and Ma, 2018). The CSMAS assesses dimensions such as mood alteration, withdrawal, and conflict, enabling us to capture a spectrum of problematic use—from excessive engagement to severe dependence—while recognizing that not all cases meet a clinical threshold (Li et al. 2023). However, we note the limitations of self-reports, particularly in adolescents, where social desirability or lack of insight may blur the line between normative and pathological use, potentially inflating prevalence estimates (Moreno et al. 2013). This phenomenon aligns with broader addiction frameworks, in which individuals persist in repetitive behaviors despite adverse consequences, driven by reward-seeking or the desire to alleviate distress (Berridge and Robinson, 2003; Brand et al. 2016). In the context of social media, the “reward” typically involves social validation, peer acceptance, and a sense of belonging—needs that become especially pronounced during adolescence (Kuss and Griffiths, 2017; Sun and Zhang, 2021; Throuvala et al. 2019).

Adolescents’ sensitivity to social cues and need for peer connection make social media platforms highly appealing due to their instant, ongoing interaction (Butler, 2024; Steinberg and Morris, 2001). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and the quest for online status increase dependence on social media for validation (Andreassen, 2015; Tutgun-Ünal and Deniz, 2015). However, overuse harms academic performance, mental health, and offline relationships (Webster et al. 2021). Academically, excessive use causes time displacement and cognitive fatigue, leading to poor focus, procrastination, and reduced grades (Malak et al. 2022; Shi et al. 2020). Psychologically, it is linked to increased anxiety, depression, and distress (Keles et al. 2020), worsened by cyberbullying, negative comparisons, and pressure to uphold idealized images (Hawi and Samaha, 2017; Oberst et al. 2017). Late-night screen time also disrupts sleep, heightening stress and emotional instability.

Recent research shows that excessive social media use heightens cyberbullying risks, especially for adolescent girls (Marinoni et al. 2024), highlighting broader issues with digital overengagement beyond addiction. Herrick (2016) notes that heavy social media activity, often seen as “cyber proficiency,” may not reflect true competence and can increase vulnerability to online threats. Socially, addiction weakens real-world ties, as adolescents favoring virtual over face-to-face interaction experience greater loneliness and disconnection (Cao et al. 2018). Paradoxically, more online time often lowers meaningful engagement (Hou et al. 2019; Rachubińska et al. 2021). Vulnerability to addiction stems from individual, social, and environmental factors that shift during adolescence. Traits like impulsivity, low self-esteem, and emotional instability strongly predict addiction (Liang et al. 2023; Zhao et al. 2022), with impulsive teens struggling to control use and those with low self-esteem seeking validation online (Balakrishnan and Griffiths, 2017; Hawi and Samaha, 2017). These risks grow amid adolescent challenges such as peer pressure, identity exploration, and romantic relationships (Sadowski, 2021).

Peer influence and social anxiety play key roles in social media addiction. Fear of exclusion drives excessive use (Tosuntaş et al. 2024), while social anxiety leads some adolescents to favor virtual spaces as safer, controlled settings (Pontes et al. 2018). As peer networks and online status grow more critical, teens may adopt addictive behaviors (Brown and Larson, 2009; Throuvala et al. 2019). Environmental factors amplify this trend. Platform designs, such as personalized feeds, instant notifications, and rewards, extend engagement (Balakrishnan and Griffiths, 2017; Liang et al. 2023), and widespread smartphone use makes disconnection harder. Persuasive design elements (Cemiloglu et al. 2021; Oulasvirta et al. 2012) form habitual cycles, testing adolescents’ self-control and promoting addiction.

Parental influence on adolescent behavior

Parents significantly shape adolescent behavior, as noted in developmental theories (Newman and Newman, 2020; Smetana, 2010). Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977) suggests that teens learn behaviors and values by observing and imitating parents, with this influence being strong during adolescence (Pratt et al. 2010). Parental Mediation Theory (Livingstone and Helsper, 2008) outlines three media management strategies—restrictive mediation (setting rules), active mediation (discussing content), and co-viewing (sharing experiences)—each affecting media habits (Clark, 2011). Studies show parental supervision and control notably impact online behavior (Baldry et al. 2019; Marinoni et al. 2023). Parental Modeling Theory highlights indirect effects, where frequent parental social media use may normalize overuse in teens (Nikken, 2017; Taraban and Shaw, 2018). Pairing modeling with open communication enhances its effect, helping adolescents observe, discuss, and manage online challenges (Alt and Boniel-Nissim, 2018; Padilla-Walker and Coyne, 2011).

Direct parental control strategies—such as setting screen time limits, monitoring internet use, and enforcing social media rules—effectively mitigate risky behaviors like excessive media use and exposure to harmful content (Love et al. 2016; Stewart et al. 2022). A meta-analysis by Collier et al. (2016) found that restrictive mediation reduces negative outcomes, including aggression, substance use, and risky sexual behavior. However, the effectiveness of these strategies relies on consistent enforcement, the quality of the parent-child relationship (Shakya et al. 2012), and adolescents’ perceptions of their fairness and legitimacy (Baldry et al. 2019).

Recent research highlights the complexity of parental control in the digital age. For example, Marinoni et al. (2023) showed that perceived parental control protected boys from cyberbullying, with its effectiveness mediated by reduced online time during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings suggest that parental control can shape adolescents’ digital engagement indirectly. However, as adolescents grow older, they require greater autonomy, and overly restrictive measures can provoke resistance (Soenens et al. 2017). Combining control strategies with autonomy support—such as involving adolescents in setting boundaries—enhances their legitimacy and encourages internalization of healthy media habits (Kuczynski, 2002).

Indirect parental influences, like modeling balanced media use through social media disengagement, support direct controls. Parents limiting their own use promote healthy digital habits, boosting teens’ self-regulation and focus on real-life interactions (Morgan and Fowers, 2022; Nikken, 2017). Unlike rules, these strategies help teens adopt lasting positive behaviors (Wang et al. 2022). This varies by culture, as views on parental authority and teen autonomy differ (Livingstone and Blum-Ross, 2020). Blending direct and indirect methods improves outcomes. Direct controls set limits, while modeling encourages sustained change. For example, Wang et al. (2022) found that parental disengagement cuts problematic media use by enhancing parent-child interactions. Beyens et al. (2022) note added benefits, like less cyberbullying and better well-being. Parents who reduce social media use offer meaningful engagement and positive examples, whereas heavy use may normalize risks like online disinhibition, heightening vulnerability (Morgan and Fowers, 2022; Wang et al. 2022).

Parental influence on adolescent behavior is multifaceted, encompassing both direct control strategies and indirect modeling. While direct interventions like screen time limits are effective in establishing boundaries, parental modeling of healthy media habits is crucial for fostering self-regulation and responsible behavior. Nevertheless, older adolescents, who often assert more independence, may respond more favorably to approaches that strike a balance between firm guidelines and recognition of their autonomy needs (Van Petegem et al. 2012). Finally, it is essential to acknowledge that parental control and modeling strategies are perceived differently across cultures and family structures, and overly restrictive or intrusive practices can become counterproductive (Baldry et al. 2019). By reducing their own social media use, involving adolescents in decision-making, and prioritizing real-life interactions, parents can support their children’s well-being and long-term development in today’s digital world.

Parent-teenager communication

Parent-teenager communication is a cornerstone of adolescent development, shaping emotional regulation, academic success, and adaptive behaviors (Bully et al. 2019; Farley and Kim-Spoon, 2014). Its importance is especially pronounced during adolescence, when youths face psychosocial challenges, engage in identity exploration, and strive for greater autonomy, yet still benefit from parental guidance (Steinberg, 2005; Smetana, 2010).

Effective communication fosters academic achievement, mental health, and strong social relationships (Padilla-Walker and Coyne, 2011). A supportive emotional climate, built on open dialogue, enhances well-being and reduces psychological distress (Kapetanovic and Skoog, 2021). Moreover, robust communication can shield adolescents from risky behaviors like substance abuse, delinquency, and problematic internet use, as those who feel comfortable discussing challenges with parents are better equipped to handle peer pressure and avoid harmful influences (Boniel-Nissim et al. 2015; Alt and Boniel-Nissim, 2018).

However, effective communication requires more than frequency; it must support connection and autonomy (Jenson and Bender, 2014). For instance, active listening—in which parents convey genuine interest and empathy—creates a trusting environment for adolescents to share their thoughts (Rogers, 1957; Kim and White, 2018). Validating emotions, even those differing from parental views, strengthens the relationship and encourages honesty (Linehan, 1993; Paley and Hajal, 2022). Additionally, clear, consistent communication fosters understanding and cooperation when parents explain rationales for rules and maintain stable boundaries (Smetana, 2010). Engaging in guided conversations about online experiences, using open-ended questions to prompt critical thinking, can empower adolescents to make informed decisions about social media use (Bağatarhan et al. 2023). Finally, a flexible, collaborative approach that allows negotiation and compromise can enhance teenagers’ autonomy and sense of responsibility (Zapf et al. 2024), further reinforcing positive online behaviors.

Communication also mediates the relationship between parental behaviors and adolescent outcomes, particularly regarding media use (Chen and Shi, 2019; Collier et al. 2016). Open discussions coupled with parental monitoring decrease aggression and externalizing behaviors while fostering critical thinking about digital consumption (Padilla-Walker et al. 2016; Boniel-Nissim and Sasson, 2018). Furthermore, Alt and Boniel-Nissim (2018) showed that effective communication reduces adolescents’ fear of missing out (FoMO), thus mitigating social media addiction and supporting healthier media habits. Additionally, consistent communication enhances the effectiveness of parental involvement. Frequent, high-quality discussions enable adolescents to internalize risks and benefits of media use, reinforcing parental monitoring efforts (Reid Chassiakos et al. 2016). Padilla-Walker et al. (2015) found that communication quality significantly predicts the success of parental mediation in fostering empathy, self-regulation, and lower aggression. In the realm of social media, communication augments strategies such as parental social media disengagement. Conversations regarding online safety and digital literacy teach adolescents to make prudent choices, limiting excessive use and exposure to harmful content (Boniel-Nissim et al. 2020; Meherali et al. 2021).

Despite its value, gaps remain. Few studies explore how communication mediates parental social media disengagement and teens’ online behaviors. While media-related communication is studied, its role in disengagement strategies for addiction prevention is less clear. Most findings come from cross-sectional designs, limiting insights into communication’s evolution as teens grow (Kapetanovic and Skoog, 2021). Longitudinal studies could reveal how ongoing communication shapes outcomes in a shifting digital landscape. Cross-cultural research is also needed to examine how norms affect communication and behavior, informing tailored parent-teen interventions across diverse settings.

Emotional regulation in adolescents

Emotional regulation, encompassing the processes by which individuals influence their emotional experiences and expressions, is especially critical during adolescence—a period of heightened sensitivity to social feedback, identity formation, and autonomy (Gross, 2015; Roth et al. 2019; Zhang and Fathi, 2024; Thompson, 1994). This developmental stage demands effective regulation to navigate interpersonal relationships, academic pressures, and identity exploration (Fathi et al. 2023; Steinberg, 2005). Ongoing maturation of the prefrontal cortex, responsible for higher-order cognitive functions like decision-making and impulse control, further contributes to these evolving capacities (Blakemore and Choudhury, 2006; Casey et al. 2008). Adolescents who regulate emotions successfully thus exhibit greater resilience, experience healthier social interactions, and demonstrate lower rates of anxiety and depression (Derakhshan and Fathi, 2024; Gross and John, 2003; Gioia et al. 2021).

This study explores how emotional regulation, parental social media disengagement, and adolescent social media addiction interact, with regulation serving as both mediator and moderator. This builds on research showing regulation’s key role in development and addiction (Compas et al. 1995; Zeman et al. 2006), including the I-PACE model linking affective and cognitive factors to online behavior (Brand et al. 2016). We use the Process Model of Emotion Regulation (Gross, 2015) to explain regulation stages and Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1977) to highlight reciprocal influences among regulation, parental disengagement, and addiction.

We propose that parental social media disengagement can facilitate adolescents’ emotional regulation by altering the emotional climate at home. By reducing their own social media use, parents model healthy digital habits and create space for more meaningful family interactions. This shift decreases stress and increases emotional support (Morris et al. 2007; Caro-Cañizares et al. 2024), thus fostering adolescents’ ability to understand and manage emotions. Adolescents with strong emotional regulation skills are better equipped to handle stressors without resorting to maladaptive coping, such as excessive social media use or substance abuse (Liu and Ma, 2019). Secure attachment relationships can further bolster self-regulation, helping adolescents withstand the temptations of the online world (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2010). In contrast, deficits in emotional regulation heighten vulnerability to addictive behaviors, as adolescents may turn to digital platforms to avoid or suppress negative emotions (Hormes et al. 2014; Gioia et al. 2021). Notably, emotional dysregulation is a risk factor for various behavioral addictions, including problematic internet and social media use (Alimoradi et al. 2022).

Emotional regulation also moderates the link between parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction, aligning with the Differential Susceptibility Model (Belsky and Pluess, 2009). According to this model, individual differences in emotional regulation can amplify adolescents’ responsiveness to both positive and negative environmental inputs. Adolescents who exhibit stronger regulation skills are more likely to internalize parental disengagement in a constructive manner, translating parents’ positive example into their own healthy technology habits. Conversely, those who struggle with emotional regulation may find it difficult to integrate beneficial parental behaviors, potentially seeking excessive media use as a coping mechanism instead. Empirical data suggest that the success of parental strategies (e.g., emotional support, guidance) is contingent on adolescents’ regulatory capacities (Eisenberg et al. 2004; Karaer and Akdemir, 2019; Schweizer et al. 2020).

Examining both the mediating and moderating roles of emotional regulation provides a more nuanced view of how environmental factors (like parental social media disengagement) and individual characteristics (like regulation capacities) interact. On one hand, emotional regulation can explain why parental disengagement affects adolescents’ social media habits (i.e., by lowering stress and raising emotional support). On the other, emotional regulation can influence how strongly parental behaviors impact adolescents, indicating that not all adolescents respond equally. This two-pronged examination captures the full complexity of emotional development and behavioral outcomes, recognizing that both process-level changes (mediation) and individual differences (moderation) shape adolescent social media addiction.

The purpose of the study

Rooted in an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018), this study investigated the complex relationship between parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction in the Chinese context. This design is particularly well-suited to address the research questions because it allows us to first establish quantitative relationships between key variables and then delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms and contextual factors through qualitative exploration.

Central to this study is the concept of parental social media disengagement, defined as parents’ deliberate reduction of their own social media use to prioritize real-life interactions and model healthy technology habits for their adolescents. Grounded in Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977) and the broader literature on parental influence (e.g., Padilla-Walker and Coyne, 2011), we posit that parental social media disengagement can serve as a protective factor against adolescent social media addiction.

Furthermore, we examine the mediating roles of parent-teenager communication and emotional regulation in this relationship. Drawing on the Process Model of Emotion Regulation (Gross, 2015), we propose that parental disengagement can foster a more open and emotionally supportive family environment, which, in turn, can enhance adolescents’ communication skills and emotional regulation capacities, reducing their susceptibility to social media addiction.

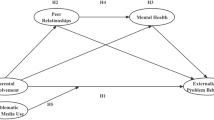

Finally, we explore the moderating role of emotional regulation, drawing on the Differential Susceptibility Model (Belsky and Pluess, 2009). We hypothesize that adolescents with higher levels of emotional regulation will be more responsive to the positive influence of parental social media disengagement, as they are better equipped to observe, internalize, and apply their parents’ modeled behaviors. Specifically, this study was designed to test the following hypotheses:

-

H1: Parental social media disengagement will be negatively associated with adolescent social media addiction.

-

H2: Parent-teenager communication will mediate the relationship between parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction.

-

H3: Emotional regulation will mediate the relationship between parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction.

-

H4: Emotional regulation will moderate the relationship between parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction, such that the association will be stronger for adolescents with higher levels of emotional regulation.

Methods

This study uses an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018) to explore the link between parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction in China. The quantitative phase tests relationships among key variables, followed by a qualitative phase that examines underlying mechanisms and context.

A mixed-methods approach is crucial as it allows us to integrate the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative research (Greene, 2007). Quantitative research provides valuable data on the prevalence and correlates of social media addiction, enabling us to test hypotheses and identify patterns (Kuss and Griffiths, 2017). However, it is limited in its ability to explain the “why” and “how” behind these associations. Qualitative research, on the other hand, provides rich insights into lived experiences, allowing us to explore the complex social and emotional dynamics that contribute to addiction (Creswell and Creswell, 2017).

In this explanatory sequential design, the quantitative phase serves as the foundation. It identifies significant statistical associations that guide the subsequent qualitative inquiry (Ivankova et al. 2006). For instance, if quantitative data reveal a negative correlation between parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction, the qualitative phase will explore the underlying mechanisms driving this relationship. This might involve examining how parental disengagement influences family communication patterns, alters the emotional climate, and fosters healthier coping mechanisms.

By conducting in-depth interviews with parents and adolescents, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of how reduced parental social media use influences family dynamics and individual well-being. We might explore how parental disengagement affects the quality of parent-child interactions, time spent together, and adolescents’ perceptions of their parents. Furthermore, we can investigate how parental disengagement might promote emotional regulation and reduce adolescents’ reliance on social media. Additionally, the qualitative phase will provide contextual insights into the barriers and facilitators parents encounter when attempting to disengage from social media. This might include exploring social pressures, perceived needs for online connection, and strategies used to overcome challenges. We can also examine the positive consequences of disengagement, such as increased family time and improved parent-child relationships.

The integration of quantitative and qualitative data will be achieved through triangulation, where we compare and contrast findings from both phases to identify areas of convergence and divergence (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018). This iterative process allows us to validate quantitative findings with qualitative insights, providing a more nuanced and holistic understanding.

Participants

The study involved 503 Chinese adolescents aged 13 to 18 years (Mage = 15.78, SDage = 1.23), with a relatively balanced gender distribution of 267 males and 236 females (see Table 1). The participants were recruited from public middle schools across various regions of mainland China, including urban centers in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, as well as rural areas in Sichuan and Henan provinces. This geographical diversity was intentional, aimed at capturing a broad spectrum of socioeconomic backgrounds and ensuring that the sample reflected the heterogeneity of the Chinese adolescent population.

Recruitment used a multi-stage sampling process to obtain a representative sample. We compiled a list of public middle schools in target regions and used stratified random sampling to select schools, ensuring balance across urban and rural areas and socioeconomic levels. Of 20 schools invited, 10 participated: four urban (two in Beijing, one each in Shanghai and Guangzhou) and six rural (three each in Sichuan and Henan). Schools were chosen based on location, student socioeconomic status, and administrative cooperation. After selection, we held sessions with teachers and parents to outline the study’s objectives and procedures, highlighting voluntary participation and data confidentiality. Only students with signed consent from themselves and their parents were included. A power analysis with G*Power 3.1 (α = 0.05, power = 0.80) determined a minimum sample of 395 participants to detect medium effects (Cohen’s d = 0.30); our final sample of 503 exceeded this, strengthening the study’s reliability.

Participants had diverse demographics, reflecting varied family dynamics in urban and rural China. Specifically, 62.5% were from single-child families, aligning with China’s one-child policy legacy, and 37.5% from multi-child families. Parental education varied: 57.3% had secondary education, 14.8% primary, and 27.9% university degrees, offering insights into how education might shape parental views on social media and child engagement. Family income also varied: 39.2% below median, 46.7% at median, and 14.1% above, enriching the analysis of socioeconomic influences on social media use and addiction. Parental occupations included 31.4% manual labor, 24.6% service, 19.7% administrative, and 24.3% professional/managerial roles, adding depth to the study.

The study was approved by University X’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), ensuring ethical compliance. All participants and parents provided informed consent after receiving clear explanations of the study’s aims, methods, and their rights, demonstrating the research team’s commitment to ethical standards.

After the quantitative phase, we purposively selected 30 participants (15 adolescents and 15 parents) from the initial pool for qualitative exploration. This approach sought to reflect diverse experiences of social media addiction and parental disengagement, while covering key demographics. The qualitative sample mirrored the broader quantitative sample’s diversity, including 15 adolescents (7 males, 8 females) and 15 parents (8 mothers, 7 fathers). This deliberate choice provided a detailed view of how parental social media disengagement, parent-teen communication, emotional regulation, and adolescent social media addiction interact in the Chinese context.

Measures

Parental social media disengagement scale (PSMDS)

The PSMDS measures adolescents’ perceptions of their parents’ efforts to reduce social media use for better interactions. Developed through a literature review, expert review, and pilot testing with 50 adolescents, the scale was refined using exploratory factor analysis, resulting in a 12-item scale with two dimensions: Active Disengagement (e.g., “My parent actively puts away their phone when we’re talking”) and Passive Disengagement (e.g., “My parent seems less distracted by their phone during family meals”). It showed strong reliability (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.85 for Active Disengagement, 0.80 for Passive Disengagement) and good construct validity (χ²/df = 2.23, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.06). The scale was culturally adapted via translation, back-translation, and cognitive interviews with 20 Chinese adolescents, followed by a pilot test with 100 participants to confirm reliability and validity. Multi-group confirmatory factor analysis established invariance across gender and urban-rural subgroups in China.

Social media addiction scale (CSMAS)

The CSMAS (Liu and Ma, 2018) assesses adolescents’ social media addiction with 28 items across six factors: Preference for Online Social Interaction, Mood Alteration, Negative Consequences and Continued Use, Compulsive Use and Withdrawal, Salience, and Relapse. Sample items include “I feel safer through social media communication” and “I feel anxious when I cannot use social media”. The scale has strong psychometric properties, with Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.75 and 0.90, making it a reliable measure widely used in Chinese digital addiction research.

Emotional regulation questionnaire (ERQ)

The Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) assesses two strategies of emotional regulation: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. The 10-item scale uses a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 4 = “Strongly Agree”). Sample items include “I can calm myself down when angry” and “I can control impulsive urges”. In this study, the ERQ demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85), with confirmatory factor analysis supporting its two-factor structure (CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04). Factor loadings ranged from 0.65 to 0.81. The ERQ is widely applied in research on emotional regulation and psychological outcomes, making it well-suited to this study.

Parent-adolescent communication scale (PACS)

The Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale (PACS), developed by Barnes and Olson (1982), evaluates communication quality between parents and adolescents. It includes 20 items divided into two subscales: Openness (e.g., “I can discuss my beliefs with my parent without feeling restrained”) and Problems (e.g., “I sometimes doubt what my parent tells me”). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”). Higher scores on the Openness subscale indicate positive communication, while higher scores on the Problems subscale reflect communication difficulties. Reliability is strong, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.85 to 0.90 for Openness and 0.75–0.85 for Problems.

Semi-structured interview guide

A semi-structured interview guide was developed to explore social media use, parental disengagement, and their effects on family dynamics and emotional well-being. The guide outlined key themes while allowing flexibility to adapt to participants’ unique perspectives. Open-ended questions (see Appendix A) encouraged participants to share detailed narratives, fostering a conversational atmosphere. Interviewers were trained to establish rapport, create a comfortable and non-judgmental environment, and probe for clarification or elaboration when necessary. This flexible approach allowed interviews to adapt to each participant’s communication style, ensuring a productive and meaningful exchange.

Procedures

Quantitative data collection occurred during school hours in classrooms to reduce disruption and ensure comfort. Trained research assistants outlined the study’s purpose, stressed confidentiality, and answered questions. Participation was voluntary with the right to withdraw, encouraging honest answers. Paper-and-pencil questionnaires measured parental social media disengagement, parent-teen communication, emotional regulation, and social media addiction, suiting diverse digital literacy levels, especially in rural areas, for fair access. Demographic data provided context.

Afterward, the qualitative phase involved semi-structured interviews with individuals in private, comfortable settings, led by seasoned researchers holding advanced degrees in psychology and social sciences. These interviewers, with over five years of qualitative experience in adolescent psychology, family dynamics, and digital media, were trained in culturally sensitive methods, aiding rapport and detailed responses on sensitive issues.

To ensure trustworthiness, member checking followed each interview, letting participants review and clarify points. Regular peer debriefing sessions allowed the team to discuss and assess interview data, reducing bias and maintaining rigor. Interviews, conducted in Mandarin, lasted 45–60 min. With explicit consent, audio was recorded, transcribed verbatim, and checked for accuracy by interviewers and an independent bilingual translator, supporting data validity, cultural fit, and reliability.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS version 28.0 (IBM Corp, 2021). Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, provided an overview of the variables, while Pearson’s correlation coefficients assessed bivariate relationships between parental social media disengagement (PSMDS), parent-teenager communication (PTCS), emotional regulation (ERQ), and adolescent social media addiction (SMAS) (Field, 2018).

Hypotheses were tested through a series of linear regression analyses using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017). Model 1 examined the direct effect of PSMDS on SMAS, controlling for demographic variables such as age, gender, family income, and parental education. Model 2 incorporated PTCS and ERQ as mediators to test whether the association between PSMDS and SMAS was mediated by communication and emotional regulation. Mediation effects were evaluated using bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to calculate bias-corrected confidence intervals (Preacher and Hayes, 2004). Moderation analysis tested whether the relationship between PSMDS and SMAS was influenced by adolescents’ emotional regulation skills. An interaction term (PSMDS * ERQ) was included to explore whether the strength or direction of the relationship varied by emotional regulation levels (Baron and Kenny, 1986).

To address potential common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted, confirming that no single factor accounted for the majority of variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Data screening procedures ensured validity and reliability, including checks for outliers (standardized residuals > ±3), normality of residuals (Shapiro-Wilk test, Q-Q plots), and multicollinearity (Variance Inflation Factor values < 10) (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2019). Missing data were handled using multiple imputation, pooling results from imputed datasets for robust estimates (Rubin, 1987).

The qualitative data, derived from semi-structured interviews, were analyzed using thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase framework. NVivo 12 software facilitated coding and theme development, ensuring rigor and transparency. Triangulation integrated quantitative and qualitative findings, comparing results to identify convergent and divergent patterns.

Results

Quantitative results

Data screening and assumptions

Prior to the main analyses, data were screened for accuracy, outliers, and missingness. To ensure the fidelity of the data entered from the paper-and-pencil questionnaires, a double-entry procedure was performed on 10% of the dataset, randomly selected. Any discrepancies found during this process were cross-verified with the original questionnaire forms and corrected, resulting in an initial data entry error rate of less than 1%. Outliers were subsequently identified using standardized residuals exceeding ±3 SD (a total of 12). Sensitivity analyses showed no meaningful changes to the results upon their exclusion, so they were retained. Shapiro-Wilk tests and Q-Q plots indicated normality of residuals, and residual-versus-predicted plots confirmed homoscedasticity. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values below 10 suggested no multicollinearity problems (Field, 2018; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2019). Missing data were handled using multiple imputation, generating five imputed datasets pooled for final estimates (Rubin, 1987). Additionally, to address potential common method bias, a Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The results, presented in Appendix B, indicated that common method bias is unlikely to significantly affect the validity of the reported relationships.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Descriptive statistics for all key variables are summarized in Table 2. The mean score for parental social media disengagement (PSMDS) was 3.45 (SD = 0.85), indicating a moderate level of disengagement among parents. The mean score for parent-teenager communication (PTCS) was 3.78 (SD = 0.72), suggesting relatively open and frequent communication. The mean score for emotional regulation (ERQ) was 3.21 (SD = 0.68), and the mean score for social media addiction (SMAS) was 3.96 (SD = 0.89), indicating moderate levels of addiction among the adolescents. Skewness and kurtosis values fell within acceptable ranges, justifying subsequent parametric tests.

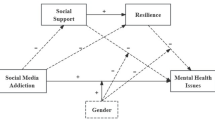

Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to assess the bivariate relationships among the key variables. As summarized in Table 3, parental social media disengagement was significantly negatively correlated with adolescent social media addiction (r = −0.42, p < 0.001), indicating that higher levels of parental disengagement were associated with lower levels of addiction. Parent-teenager communication was significantly positively correlated with parental social media disengagement (r = .38, p < 0.001) and significantly negatively correlated with social media addiction (r = −0.30, p < 0.001). Emotional regulation was significantly positively correlated with both parental social media disengagement (r = .31, p < 0.001) and parent-teenager communication (r = 0.35, p < 0.001), and significantly negatively correlated with social media addiction (r = −0.45, p < 0.001). These correlations suggest that better communication and emotional regulation skills are associated with lower levels of social media addiction.

In addition to these primary correlations, partial correlations controlling for demographic variables (age, gender, family income, and parental education level) were also examined. These partial correlations were consistent with the zero-order correlations, suggesting that the observed relationships were robust and not confounded by demographic factors.

Mediation and moderation analyses

To test the hypothesized mediating and moderating effects, we conducted a series of linear regression analyses using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017). A mediation analysis examined whether parent-adolescent communication (PACS) and emotional regulation (ERQ) mediated the relationship between parental social media disengagement (PSMDS) and adolescent social media addiction (SMAS). The PROCESS macro (Model 4; Hayes, 2017) was employed, with 5000 bootstrap samples to produce bias-corrected confidence intervals (Preacher and Hayes, 2004). This approach accommodates potential skewness in the indirect effect distribution.

As shown in Table 4, both PACS and ERQ significantly mediated the PSMDS–SMAS link. PSMDS was negatively associated with SMAS (total effect = −0.42, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), and while the direct effect remained statistically significant (−0.20, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001), partial mediation was indicated. The combined indirect effects through PACS and ERQ accounted for approximately 36% of the total effect, suggesting additional unmeasured factors (e.g., parental warmth or family environment) may also influence adolescent susceptibility to social media addiction.

A moderation analysis tested whether ERQ moderated the PSMDS–SMAS relationship (PROCESS Macro Model 1; Hayes, 2017). This step was grounded in literature highlighting the pivotal role of emotional regulation in shaping adolescent outcomes in technology use (Gross, 2002; Eisenberg et al. 2004).

Table 5 indicates a significant PSMDS × ERQ interaction (p < 0.05), suggesting that ERQ modifies the negative association between parental disengagement and adolescent social media addiction. A simple slopes analysis showed the PSMDS–SMAS link was significantly stronger (b = −0.32, p < 0.001) for adolescents with high ERQ (1 SD above the mean) compared to those with low ERQ (b = −0.08, p < 0.05).

These analyses indicate that both parent-adolescent communication and emotional regulation partially mediate the negative association between parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction. Additionally, emotional regulation moderates this relationship, with adolescents with higher emotional regulation skills benefiting more from parental disengagement. These findings highlight the complex interplay between parental behaviors and adolescents’ individual characteristics in shaping their susceptibility to social media addiction.

Overall, the results supported the hypotheses. Parental social media disengagement was negatively associated with adolescent social media addiction, partially mediated by improved parent-teenager communication and enhanced emotional regulation. Furthermore, the moderation analysis indicated that adolescents with better emotional regulation benefited more from parental social media disengagement. These findings underscore the importance of communication and emotional regulation in mitigating social media addiction and offer practical implications for interventions.

Qualitative findings

The qualitative phase of this study, comprising in-depth interviews with adolescents and their parents, yielded a tapestry of rich and nuanced narratives that illuminate the complex dynamics of parental social media disengagement and its impact on adolescent social media addiction. Through meticulous thematic analysis, four overarching themes emerged, offering profound insights into the lived experiences and perspectives of the participants:

Evolving family connections: from digital distraction to genuine engagement

Parental social media disengagement acted as a catalyst for profound transformations in family dynamics, shifting interactions from distracted digital engagement to genuine presence and connection. Parents, across various demographics, reported feeling liberated from the constant pull of their devices, allowing them to invest more fully in their relationships with their children. A father of two teenagers from an urban setting shared, “Before, it felt like a constant juggling act, trying to balance my phone and my kids. Now, when I’m with them, my phone stays in my pocket, and they have my undivided attention. It’s as though we’re truly seeing each other again”. This sentiment was echoed by a mother from a rural area, who expressed, “In our village, everyone is always on their phones. But when I made a conscious decision to put mine down, I realized how much I was missing out on with my daughter. We can now have real conversations without interruptions, and it’s made our bond so much stronger”.

Adolescents, too, noticed and appreciated this shift. A 16-year-old boy from an urban area remarked, “It used to feel like my parents were always half-present, even when they were physically there. Now, I feel like they’re really with me, and it makes me feel valued”. A 13-year-old girl from a rural background added, “My mom used to be on her phone all the time, even during dinner. Now, she actually talks to me and asks about my day. It makes me feel like she cares”.

Beyond individual interactions, parental disengagement had a ripple effect, transforming the overall emotional climate of the household. Family meals, once punctuated by the ping of notifications, became sacred spaces for shared laughter and meaningful conversations. One family from an urban setting described how they started having regular “tech-free Tuesdays,” where everyone put their devices away and engaged in activities like board games or cooking together. A rural family shared how they rediscovered the joy of spending time outdoors, going on hikes and picnics without the distraction of social media. As one 15-year-old boy poignantly reflected, “It’s like we’ve traded the virtual world for the real one, and it’s so much more fulfilling”.

The power of communication: strengthening trust and mutual understanding

Parental disengagement from social media catalyzed a marked increase in open and authentic communication, fostering stronger trust and understanding within families. Adolescents across diverse backgrounds reported feeling safer and more connected to their parents, leading to increased willingness to share their experiences and concerns. A 16-year-old urban male adolescent confided, “I used to think my parents wouldn’t get the whole online thing, so I kept a lot to myself. But now that they’re more present, I feel like I can actually talk to them about anything. It’s like we’re on the same wavelength”. Similarly, a 14-year-old female adolescent from a rural village noted, “My mom used to be so busy with her phone, she barely listened when I tried to talk to her. Now, she actually looks at me and asks questions. It makes me feel like she really cares about what I have to say”.

This enhanced openness facilitated a shift in the parent-child dynamic, with parents becoming supportive guides, helping their children navigate the complexities of the digital world. A suburban mother of a 15-year-old son explained, “Before, I felt like I was always a step behind, trying to understand what my son was up to online. Now, we have open conversations about social media, and I feel more equipped to help him make smart choices”. Even parents who initially felt hesitant about technology found ways to bridge the generational gap. A father from a rural community, who self-identified as “not very tech-savvy,” shared, “I may not understand all the apps and games my kids use, but I’ve learned to ask questions and show interest. It’s opened up a whole new world of conversation for us”.

Beyond discussions about social media, this enhanced communication permeated all aspects of family life, fostering a deeper sense of emotional intimacy and connection. Adolescents reported feeling validated and understood, decreasing their reliance on social media for external affirmation. As one 17-year-old urban female adolescent poignantly stated, “My parents’ presence has filled a void I didn’t even know was there. Now, I don’t need to chase likes and comments to feel good about myself. I have my family”. Additionally, a 15-year-old male adolescent from a rural setting observed a qualitative shift in the family dynamic beyond mere conversation, noting, “We laugh more now, we do more things together as a family. It’s not just about talking; it’s about feeling closer”.

Fostering emotional resilience: moving from digital dependence to personal strength

The qualitative data illuminated the profound role of emotional regulation in mitigating adolescent susceptibility to social media addiction, particularly when coupled with parental social media disengagement. Adolescents with well-developed emotional regulation skills described a sense of empowerment and self-efficacy in navigating the often turbulent emotional currents of the digital world. One 17-year-old girl articulated this newfound strength, saying, “Before, social media was like a rollercoaster – one minute I’d be on top of the world, the next I’d be in a pit of despair. Now, I feel more grounded. I can handle the ups and downs without getting sucked into the endless scroll”.

This shift towards emotional autonomy was echoed by parents, who observed a marked transformation in their children’s behavior. One father noted, “My son used to have these explosive outbursts, especially when things didn’t go his way online. Now, he’s much calmer and more collected. He even talks about his feelings instead of bottling them up”. This suggests that parental disengagement, by reducing the constant barrage of digital stimuli and fostering a more emotionally connected environment, can serve as a crucible for forging emotional resilience in adolescents.

Furthermore, the interviews revealed a fascinating interplay between parental modeling and adolescent emotional regulation. Adolescents whose parents actively practiced disengagement often internalized these behaviors, recognizing them as a blueprint for healthy coping. One 15-year-old boy shared, “Seeing my dad put his phone away and focus on us made me realize that there are other ways to deal with boredom or anxiety. I started reading more, playing my guitar, even just going for walks. It’s like I’ve discovered a whole new world outside of my phone”.

This internalization of healthy habits extended beyond mere imitation. Adolescents reported a greater awareness of their emotional states and a conscious effort to employ adaptive strategies, such as mindfulness and deep breathing, when faced with challenging situations. This newfound emotional intelligence, nurtured in the context of parental disengagement, served as a powerful shield against the addictive allure of social media.

Addressing the digital world: a collaborative process of challenges and learning

The qualitative data painted a nuanced portrait of the digital landscape, highlighting both the allure and the perils of social media. Parents and adolescents across different demographics acknowledged the challenges of disengagement, recognizing the constant tug-of-war between the desire for connection and the need for boundaries. A mother from an urban area (age 45) admitted, “It’s like trying to quit smoking. You know it’s bad for you, but it’s so easy to slip back into old habits. It takes constant vigilance and willpower”. Similarly, a rural father (age 42) shared, “In our village, everyone is always on WeChat. It can feel isolating to disconnect, but I know it’s important for my family”.

Adolescents, too, grappled with the complexities of navigating a world where social media is deeply intertwined with their social lives and identities. While they appreciated their parents’ efforts, they also voiced concerns about being left out or misunderstood. A 15-year-old urban girl noted, “I want my parents to be present, but I also want them to understand my world. It’s a tough balance”. Echoing this sentiment, a 17-year-old boy from a rural area added, “Sometimes I feel like my parents are from a different planet. They don’t get how important social media is for staying connected with my friends”.

Despite these challenges, the interviews revealed a remarkable spirit of resilience and adaptability. Parents shared a range of creative strategies they had employed to successfully disengage from social media. A mother of three from an urban area proudly declared, “We’ve turned our living room into a ‘no-phone zone’ after dinner. It’s become a sacred space for us to connect, play games, and just be a family”. Meanwhile, a rural father found success with a more gradual approach, explaining, “I started by setting specific times each day when I wouldn’t use my phone. It was hard at first, but it got easier over time”.

Adolescents also played an active role in shaping their digital experiences. Empowered by their parents’ example and open communication, they became more mindful of their social media use. A 17-year-old urban girl shared, “I used to feel like I was constantly chasing likes and comments. Now, I’m more focused on building real relationships and pursuing my passions offline. It’s liberating”. A 16-year-old boy from a rural area added, “I’ve started setting time limits for myself on social media. It’s helped me focus more on my studies and spend more time with my family”.

These narratives underscore the dynamic and evolving nature of navigating the digital landscape. It is not a solitary struggle but a shared journey of challenges and growth. Through open communication, mutual respect, and a willingness to adapt, families can forge a path towards a healthier and more balanced relationship with technology.

Discussion

This mixed-methods investigation explores the intricate relationships among parental social media disengagement, parent-teenager communication, emotional regulation, and adolescent social media addiction within a Chinese context. By integrating quantitative and qualitative data, the study not only finds support for its hypothesized associations but also highlights nuanced mechanisms that may extend beyond traditional foci in the literature. The analysis underscores the interplay between familial dynamics and individual competencies, contributing to theoretical discussions and offering practical implications for addressing addiction in an increasingly digital landscape.

Parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction

The study identified a statistically significant negative association between parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction, corroborating prior evidence of parental influence on youth media behaviors (Kuss and Griffiths, 2017; Nikken, 2017). Anchored in Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977), this finding suggests that parents who prioritize offline interactions over digital engagement model adaptive media habits, which adolescents may subsequently emulate. Qualitative data enrich this interpretation, revealing that adolescents perceive greater familial connection when parents eschew social media, with practices such as device-free meals potentially diminishing the allure of online validation. This indirect influence contrasts sharply with the literature’s emphasis on direct controls—such as monitoring or restriction—which often dominate discussions of parental mediation (Gentile et al. 2014; Sanders et al. 2016).

This contribution is noteworthy in potentially reorienting debates from coercive strategies, which may engender adolescent resistance (Soenens et al. 2017), toward a subtler, modeling-based approach. In China’s collectivistic milieu, where familial harmony is paramount, parental disengagement may leverage cultural norms to enhance its efficacy, potentially fostering a home environment less saturated with digital distractions (Beyens et al. 2022). The partial mediation by communication and emotional regulation suggests that while these mechanisms are critical, a direct effect persists, which could be attributable to unexamined factors such as heightened parental emotional availability or a reinforced family climate (Farley and Kim-Spoon, 2014; Kapetanovic and Skoog, 2021). This residual effect invites reconsideration of the assumption that parental influence operates solely through explicit mediation, inviting further exploration of implicit relational dynamics in addiction prevention.

This finding offers a new perspective for Social Learning Theory, highlighting its application to digital behaviors in current family settings. In these settings, parental actions act as important guides, especially with widespread media use. For practical application, this suggests that efforts helping parents to control their own media use could bring future advantages for adolescent well-being, particularly in cultures where close community ties are valued.

The mediating role of parent-teenager communication

The partial mediation of parent-teenager communication in the relationship between parental disengagement and adolescent social media addiction highlights a potentially pivotal mechanism of influence. Quantitative results indicate that reduced parental social media use is associated with enhanced communication quality, which in turn appears to cultivate healthier adolescent media habits. Qualitative insights further reveal that open dialogue may enable parents to guide adolescents’ online experiences, potentially contributing to media literacy and possibly diminishing reliance on social media for emotional validation (Boniel-Nissim et al. 2020). This finding aligns with research on active parental mediation, which prioritizes discussion over restriction (Clark, 2011; Padilla-Walker and Coyne, 2011), yet it diverges from studies fixated on rule-based approaches (Livingstone and Helsper, 2008).

This contribution adds to current debates by suggesting communication as a conduit for indirect parental influence, challenging the prevailing focus on restrictive mediation as the primary deterrent to addiction. Unlike control-oriented strategies, which may undermine adolescent autonomy and provoke defiance (Soenens et al. 2017), active communication may foster self-regulation and resilience, aligning with developmental needs during adolescence (Smetana, 2010). In the Chinese context, where hierarchical yet interdependent family structures prevail, this mechanism may be particularly potent, as adolescents value parental guidance that respects their emerging autonomy.

This result helps connect Social Learning Theory with attachment ideas. It indicates that parental disengagement might improve parental availability, potentially leading to stronger, more secure communication that could protect adolescents from addiction (Mikulincer and Shaver, 2010). In practice, this supports interventions teaching parents how to engage in understanding, open dialogue. Such skills might boost the positive effects of disengagement and provide a workable option instead of technology-focused controls.

The mediating and moderating roles of emotional regulation

Emotional regulation appears to function as a dual-force mechanism—both mediating and moderating—the link between parental disengagement and adolescent social media addiction, offering a more nuanced lens on addiction dynamics. As a mediator, it partially accounts for how disengagement is associated with reduced addiction: quantitative data indicate that adolescents in less digitally distracted households exhibit improved emotional management, which correlates with lower addiction levels (Liu and Ma, 2019). This suggests that parental disengagement may cultivate a home environment conducive to emotional skill development, potentially reducing the propensity for maladaptive coping via social media (Gross, 2015). However, the mediation is incomplete, indicating a direct effect of disengagement—possibly through enhanced parental presence or a less media-centric family ethos—that may independently contribute to curbing addiction (Kapetanovic and Skoog, 2021).

As a moderator, emotional regulation appears to amplify the impact of parental disengagement: adolescents with superior regulation skills exhibit greater reductions in addiction when parents disengage, compared to peers with weaker capabilities (Schweizer et al. 2020). This interaction underscores a critical contingency: the efficacy of parental behavior may be influenced by the adolescent’s pre-existing emotional competencies, reflecting a synergy between external influence and internal capacity.

This dual role contributes to debates by suggesting an integration of environmental and individual factors into a cohesive framework, offering an alternative to views that attribute addiction solely to external controls or personal deficits. It invites a re-examination of the literature’s potential overreliance on parental action (e.g., Baldry et al. 2019) by highlighting the adolescent’s agency in modulating outcomes, aligning with developmental theories of self-regulation (Steinberg, 2005). Moreover, it suggests complexities not always captured by cross-sectional assumptions about uniform effects, revealing heterogeneity in how familial strategies resonate across individuals.

In terms of theoretical contribution, this finding could enhance the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model (Brand et al. 2016). It points to emotional regulation as a key link between parental behavior and addiction. This also calls for longitudinal research to clarify the cause-and-effect relationship: does disengagement improve regulation, or the other way around? From a practical standpoint, this highlights the importance of integrated interventions. Combining parental disengagement with emotional regulation training (like mindfulness programs; Extremera et al. 2019) might lead to better results, especially in high-stress places like China, where academic pressures can worsen media reliance.

Qualitative insights

Qualitative data from Chinese families suggest the cultural specificity of these findings, indicating how familial interdependence may amplify the effects of parental disengagement. Adolescents reported that parents’ reduced social media use enhanced attentiveness and guidance, strengthening emotional bonds and supporting healthier media habits. This aligns with collectivist norms prioritizing family unity (Nikken, 2017), contrasting with individualistic contexts where autonomy-focused strategies often predominate (Livingstone and Blum-Ross, 2020).

This contribution deepens cross-cultural debates by suggesting that indirect parental influence may hold unique potency in societies valuing interconnectedness, raising questions about the universality of Western-centric models of addiction prevention. It suggests that cultural frameworks modulate the efficacy of familial interventions, highlighting the importance for researchers to contextualize findings rather than extrapolate broadly. Practically, it highlights the potential of culturally tailored programs that leverage familial cohesion to address digital overreliance, offering potential insights for developing a blueprint for non-Western settings.

Practical implications and future directions

This mixed-methods study suggests an interplay of factors associated with adolescent social media addiction and provides insights for targeted interventions. Quantitative data emphasize parental modeling and communication, while qualitative findings highlight how presence, dialogue, and emotional ties appear to shape teens’ media habits. Thus, it is recommended that parent-focused interventions consider going beyond reducing social media use, promoting a home environment that values real-life interaction through “tech-free” zones, device-free times, group activities, and meaningful talks (Nikken, 2017). Strengthening face-to-face engagement may support open communication, aligning parental goals with teen behaviors. Programs could aim to teach parents key skills—active listening, empathy, and age-appropriate conversation—to build a healthier media setting (Padilla-Walker and Coyne, 2011).

The study also stresses nurturing teens’ emotional regulation, given its mediating and moderating roles in relation to addiction. Schools or community programs can teach mindfulness, stress management, and coping strategies (e.g., relaxation, cognitive reappraisal) to help lessen reliance on social media for emotional relief (Schweizer et al. 2020). Parent strategies could also aim to bolster emotional regulation, with workshops training parents in techniques like modeling calm responses and encouraging adaptive handling of emotions, potentially enhancing the benefits of disengagement (Casale et al. 2016). Combining modeling with emotional regulation coaching may offer a promising approach to guide teens away from addictive digital habits.

Additionally, qualitative findings point to various barriers (e.g., parents’ perceived social obligations online, concerns about missing crucial updates) and facilitators (e.g., social support, communal norms favoring offline quality time) to parental social media disengagement. Tailored interventions might provide parents with practical resources—for instance, guidelines to manage personal social media usage or suggestions for alternative family activities—while also fostering community-wide dialogue about healthy technology habits. Engaging local schools, neighborhood organizations, or culturally relevant platforms could bolster community support and normalize reduced screen exposure among families, particularly in Chinese cultural settings that value collective well-being. These practical implications suggest that family-based interventions may contribute to improving adolescent digital habits by empowering parents with actionable tools and community backing. On a policy level, the findings advocate for government or educational initiatives to fund and implement family workshops and school programs focused on emotional regulation and media balance. Such policies could integrate these strategies into existing public health frameworks, promoting widespread adoption across urban and rural Chinese communities to address the growing challenge of adolescent social media addiction (Beyens et al. 2022).

Looking ahead, future research should prioritize longitudinal designs to examine the evolving dynamics between parental behaviors, communication patterns, emotional regulation, and adolescent social media addiction over time. Such designs can address the limitations of the current cross-sectional framework, clarifying causality and tracking long-term impacts. Cross-cultural studies are also necessary for assessing generalizability and for developing culturally sensitive interventions. As digital platforms continue to evolve, ongoing research must remain adaptable, exploring emerging technologies’ impacts on adolescent well-being and investigating how parental practices—including social media disengagement—can evolve in response. From a policy perspective, these research directions could inform the development of evidence-based guidelines for educators and policymakers, ensuring that interventions remain relevant amid technological advancements. Finally, future inquiries should explore diverse family structures, including single-parent, blended, or multigenerational households, with the aim of tailoring interventions to better meet the varied needs of families navigating the digital age.

Limitations

This mixed-methods study offers insights into parental social media disengagement and adolescent social media addiction but has limitations. First, the cross-sectional quantitative data limit our ability to confirm causal links. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine the timing and interaction of these factors as teens grow and digital contexts change, tracking long-term effects of disengagement and communication, pinpointing intervention opportunities, and assessing shifts over time.

Second, the qualitative phase deepened understanding of parents’ and teens’ experiences, but its small sample size restricts generalizability. Future research should use larger, more varied samples across socioeconomic levels, family types, and cultures to boost external validity and inform tailored interventions. Third, reliance on self-reports risks social desirability bias and recall errors. Adding observational or objective social media use data could strengthen validity. Finally, while we studied communication’s mediating role and emotional regulation’s moderating role, other factors—like communication content, peer influence, and diverse regulation strategies—warrant further exploration.

Additionally, academic fields interpret “addiction” differently, affecting how our findings are viewed. Psychiatrists often use clinical criteria from the DSM-5 or ICD-11, emphasizing severe conditions, which may not fully align with our focus on behavioral and emotional patterns rather than clinical thresholds. Psychologists might prioritize compulsive habits and emotional dependence, even below clinical levels, leading to differing views on our reported addiction’s significance. We define addiction via behavioral frameworks, acknowledging this may not match clinical standards perfectly, and suggest future research combine both perspectives for a fuller understanding.

Conclusion

This mixed-methods study provides evidence suggesting that parental social media disengagement, supported by open communication and a nurturing family environment, may play an important role in reducing indicators of adolescent social media addiction. The findings also suggest a positive impact of parental disengagement on strengthening family bonds, fostering emotional well-being, and its association with adolescents’ emotional regulation skills. These results underscore the need for a family-centered approach to addressing the challenges posed by adolescent social media use. Recognizing the interplay between parental behavior, communication, and emotional dynamics can inform the development of more effective, culturally relevant interventions to help families maintain healthy digital habits. Future research should expand on these findings by employing longitudinal designs, exploring diverse cultural contexts, and integrating objective measures of media use and emotional regulation. As technology evolves, continued research and innovative strategies will continue to be important for safeguarding adolescent well-being in the digital era.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Al-Samarraie H, Bello KA, Alzahrani AI, Smith AP, Emele C (2022) Young users’ social media addiction: causes, consequences and preventions. Inf Technol People 35(7):2314–2343. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-11-2020-0753

Alimoradi Z, Lotfi A, Lin CY, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH (2022) Estimation of behavioral addiction prevalence during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Addiction Rep. 9(4):486–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-022-00435-6

Alt D, Boniel-Nissim M (2018) Parent–adolescent communication and problematic internet use: the mediating role of fear of missing out (FoMO). J Fam Issues 39(13):3391–3409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18783493

Andreassen CS (2015) Online social network site addiction: a comprehensive review. Curr Addiction Rep. 2(2):175–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9

Bağatarhan T, Siyez DM, Vazsonyi AT (2023) Parenting and Internet addiction among youth: the mediating role of adolescent self-control. J Child Fam Stud 32(9):2710–2720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02341-x

Balakrishnan J, Griffiths MD (2017) Social media addiction: What is the role of content in YouTube? J Behav Addictions 6(3):364–377. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.058

Baldry AC, Sorrentino A, Farrington DP (2019) Cyberbullying and cybervictimization versus parental supervision, monitoring and control of adolescents’ online activities. Child Youth Serv Rev 96:302–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.058

Bandura A (1977) Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall

Baccarella CV, Wagner TF, Kietzmann JH, McCarthy IP (2018) Social media? It’s serious! Understanding the dark side of social media. Eur Manag J 36(4):431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.07.002

Barnes HL, Olson DH (1982) Parent-adolescent communication scale. In DH Olson, HI McCubbin, H Barnes, A Larsen, M Muxen, & M Wilson (Eds.), Family inventories: Inventories used in a national survīey of families across the family life cycle (pp. 33-48). St. Paul: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota. https://doi.org/10.1037/t56782-000

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Personal Soc Psychol 51(6):1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173