Abstract

Earning mothers worldwide constantly juggle the delicate balance between their professional and personal lives. For Indian women, this challenge is amplified by a unique socio-cultural landscape that reveres and restricts them. In India, women are revered as Shakti, embodying strength and resilience, and are expected to seamlessly excel in multiple roles, especially as mothers, a status held in the highest regard. This expectation aligns with the supermom notion, which assumes that women must possess extraordinary abilities to thrive in every aspect of life. While some research discusses the supermom notion from the above standpoint, there is a lack of research examining how mothers interpret and relate to it. This study aims to fill that gap by examining how earning mothers in India perceive the concept and its role in shaping their sense of success in both personal and professional spheres. A content analysis of responses from 305 earning mothers was conducted using symbolic interactionism as a framework, revealing a near-even split. At the same time, some viewed the supermom notion as a source of strength; others saw it as a heavy burden. Moreover, their perspectives often diverged significantly from the conventional definition, indicating how lived experiences may shape their understanding. By adopting a psycho-social lens, the paper explores these contrasting perspectives to reveal the broader impact of the supermom notion on earning mothers, offering a more profound insight into its perceived role in their personal and professional lives. Ultimately, the paper presents the psychological and practical implications of the findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In India’s evolving urban landscape, a growing number of educated women are successfully balancing full-time careers with motherhood (Verma, 2020). Unlike previous generations, where many women had to forgo professional aspirations once they became mothers, today’s urban working women are navigating both roles without feeling the need to sacrifice one for the other. This shift suggests a transformation in societal and personal perspectives and expectations on work-life balance.

While women from lower socio-economic backgrounds in India have long managed the dual responsibilities of employment and motherhood, research indicates that for many, this has been a necessity rather than a choice—often leading to adverse experiences such as low wages, discrimination, poor working conditions, long hours of work and very few holidays (Srivastava and Srivastava, 2010). In contrast, educated, urban women in well-paying jobs may experience these dual roles differently, potentially viewing them as integral to their sense of identity and fulfilment. The term ‘supermom’ has been further popularised through mass media articles that highlight the lives of prominent women who have successfully balanced motherhood with demanding professional careers. For instance, Indian actresses such as Sridevi (T.N.N., 2018) and Aishwarya Rai (Fernandes, 2017) have been portrayed as embodying the supermom ideal, reinforcing the cultural visibility and aspirational quality associated with this notion. Given this evolving dynamic, exploring how today’s women perceive motherhood is crucial, particularly concerning cultural ideals such as the “supermom” narrative. Understanding the meaning they attach to this notion can offer valuable insights into how they navigate the challenges of motherhood while developing a personal and professional identity in contemporary India.

The complex roles women have played in Indian historical and mythological contexts, particularly in relation to motherhood, offer valuable insights into how societal, religious, and cultural narratives have shaped and been shaped by the multifaceted identities of women in India. Bhattacharji (2010) delves into the role of motherhood in ancient Indian society in a fascinating chapter on motherhood, highlighting how it was both a revered and obligatory aspect of a woman’s life. Motherhood has been idealised in various institutional structures, including religion, media, and law, often without corresponding empowerment for women (Krishnaraj, 2010). Though the term supermom does not have a direct native (Hindi) equivalent term as it is a relatively recent cultural construct largely emerging from Western contexts, it is a concept that has increasingly entered Indian discourse, particularly in urban settings, through media, advertising, and social commentary (Sarkar, 2020). The term encapsulates the multifaceted responsibilities that modern Indian mothers undertake, often juggling professional commitments with familial duties.

The term “motherhood” emerged as a subject of interest among social scientists in the late 19th century in the West (Rich, 1976). Motherhood encompasses the care and nurturing of children, with primary caregiving responsibilities falling on mothers. The modern concept of a “good mother” emerged in the mid-20th century, gaining prominence in the 1950s (Paré and Dillaway, 2005; Porter, 2010). From 1945 to 1965, women were encouraged to have large families, with motherhood seen as their “true destiny” (Porter, 2010). A good mother was expected to love her children unconditionally and prioritise their care. By the 1970s, this role expanded to include responsibility for children’s cognitive development and entertainment. In 1990s, the idea of “stay-at-home mothers” evolved further and the modern interpretation of a mother emphasised active involvement in all aspects of her child’s psychological, emotional, and physical well-being and development (Hays, 1996; Johnston and Swanson, 2003; Paré and Dillaway, 2005; Tardy, 2000; Warner, 2006) leading many professional women to leave their careers to focus on family (Belkin, 2003; Vavrus, 2000).

However, some women continued to be employed. For instance, the World Bank (n.d.) reports that India’s female labour force participation rate was around 31% in 1990. Although this rate experienced fluctuations over the years, it highlights that a substantial proportion of women were actively engaged in the workforce during that decade. With changing neoliberal economic, political, and cultural aspects, mothers were increasingly encouraged or required to participate in paid work (Schmidt et al., 2023). Motherhood literature suggests that working mothers are often labelled a “supermom,” where they are expected to balance their career and family without compromising their children’s success (DeMeis and Perkins, 1996; Hays, 1998). A more recent definition of the supermom notion states, “Being a supermom demands mothers to have higher (super) capacities to perform well in all life domains. In a practical sense, a supermom has a job, can carry out household/family responsibilities smoothly, can present herself in full control, and can keep herself together and is on top of it all” (Oliver, 2011, p.9). The concept of supermom implies that “even when women have jobs outside the home, their primary responsibility should still be motherhood” (Paré and Dillaway, 2005, p.72). Alvesson and Willmott (2002) highlight how organisations engage in identity regulation processes to shape employees’ self-perceptions and work orientations. In a similar vein, the self-identity of earning mothers is influenced by broader societal expectations, with the notion of the supermom functioning as a form of identity regulation that prescribes idealised standards for both maternal and professional roles. This dual burden on earning mothers is referred to as the “second shift”, as coined by Hochschild in her 1989 work, “The Second Shift” (Brailey and Brittany, 2019). In her work, Hochschild examines the dual burden faced by working women who, after completing a full day of paid employment, return home to perform the majority of household and childcare duties. She also uncovers persistent gender imbalances in domestic responsibilities despite women’s significant participation in the workforce. This imbalance often leads to feelings of guilt, marital tension, and exhaustion among women. To combat the perception of being inadequate mothers, many earning mothers continue to place their families first (O’Reilly, 2010).

Despite extensive research on motherhood and its challenges, we are unaware of any studies that explore how mothers interpret and engage with the concept of the supermom ideal. Existing literature on supermom primarily discusses it as the ability to ‘do it all, ’ which presents a one-dimensional perspective. According to identity theory (Stryker and Burke, 2000), identities are internalised role expectations; the more salient an identity, the more likely it is to guide behaviour across situations. Since the supermom identity reflects internalised role expectations to excel at work and home, it is expected to be invoked across various social situations in both personal and professional lives, making it salient to their self-concept. Therefore, the central research question is to investigate the meaning that the supermom notion holds for mothers, the significance they attach to it, and whether they perceive it as beneficial or detrimental. We research urban earning mothers based in India. Our study employs a qualitative approach, utilising symbolic interactionism to examine the subjective interpretations of the supermom notion. Symbolic interactionism helps to understand the subjective meanings mothers develop about the supermom notion based on their reality of social interactions and experiences. By centring on mothers’ perspectives, our research provides a deeper understanding of the complexities and impact of the supermom notion on their identity formation.

Literature review

The sociocultural context of motherhood

In Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, Rich (1976) critically examines motherhood, differentiating between the oppressive institution of motherhood and the empowering, complex experience it can represent. Additionally, Chodorow (1995) expands our understanding of gender identity and roles, emphasising how they are co-constructed through mother-child relationships and influenced by societal norms. Chodorow argues that self-awareness regarding one’s gender, thoughts, emotions, and cultural contexts shapes individual gender identities. The sociological understanding of gender stems from historical, cultural, and societal norms that shape gender roles based on upbringing and internalised beliefs. The symbolic interactionism perspective is crucial for examining how societal influences and unconscious aspects of motherhood contribute to mothers’ self-identity. As women’s self-identity shifts, they increasingly embrace multiple societal roles (Oliver, 2011). Consequently, motherhood forms the foundation of the supermom notion, rooted in the belief that women desire to ‘have it all’ and make a difference (Edley, 2004; Kinser, 2008)

Supermom through a social constructivism lens

From a theoretical perspective, social constructivism posits that knowledge and meaning are created through social interactions and shared beliefs within cultural and historical contexts (Berger and Luckmann, 1966). In the Indian context, the concept of the “supermom” is a powerful social construct shaped by traditional gender roles, societal expectations, and evolving economic realities. In Indian culture, the ten-armed goddess Durga symbolises the “supermom” ideal (Sheer, 2011). The image of the supermom, who efficiently manages a career, domestic responsibilities, and motherhood, has been glorified, particularly in urban and middle-class India (Radhakrishnan, 2009). However, many working mothers admit that achieving this is impossible, leading many to prioritise motherhood over their careers (Iyer, 2013). The identity of motherhood often overshadows all other aspects of a woman’s identity, with Indian women being raised from childhood to embody the ideal mother (Sinha, 2010). This idealised version of motherhood reflects how society constructs and perpetuates gendered expectations through media, familial norms, and collective values, creating a narrative that women are inherently capable of seamlessly balancing these multiple roles (John, 2008).

Motherhood in India is deeply embedded in the country’s socio-historical and cultural fabric. In a patriarchal society like India, motherhood is not just an individual or biological experience but a socially constructed role laden with expectations, responsibilities, and norms. Although in colonial India, the society redefined the ideal of motherhood in response to nationalist movements, the image of the “ideal Indian woman” or “Bharat Mata” (Mother India) became a symbol of the nation itself. Chatterjee (1993) argues that the nationalist discourse relegated women to the domestic sphere, idealising their roles as mothers and keepers of tradition. Therefore, the glorification of motherhood continued to exert control over women’s bodies and reproductive work while framing them as vital to the nation’s moral and spiritual integrity.

In postcolonial India, the valorisation of motherhood continues, with the modern state upholding traditional roles for women even as it encourages women’s participation in public life. Historically, the role of women in India has been primarily defined by their reproductive function (Chakravarti, 1993). Welfare policies, for instance, often promote maternal health and child welfare, reinforcing the idea that women’s primary role is that of a caregiver (Desai, 2010). Women are central to the care economy, bearing a significant portion of the burden of “unpaid care work,” including household chores and family responsibilities. These tasks, both physical and psychological, often hinder even educated women in professional roles from pursuing “paid work” (Agarwal, 2021; Oxfam India Inequality Report, 2020; Krishnaraj, 2010). In recent decades, feminist movements and organisations in India have sought to challenge traditional gender roles, advocating for greater recognition of women’s contributions beyond motherhood. These movements underscore the importance of shared responsibilities in child-rearing and household tasks, advocating for a reassessment of rigid gender roles that disproportionately burden women with caregiving (Basu, 1995).

Supermom in today’s social media

The notion of the supermom distorts traditional motherhood by promoting misleading stereotypes and restrictive labels, and is criticised in literature (Hauser, 2005), used in advertisements (Skenazy, 2007), and analysed in academic works (Hays, 1998; Paré and Dillaway, 2005). Social media often portrays motherhood as unrealistic, which can affect how mothers perceive themselves and others (Djafarova and Trofimenko, 2017). The identities of real-life mothers are both influenced by and overshadowed by media representations of motherhood (Glenn et al., 1994), which evolve into “culturally constructed consensuses” (Lang, 2006, p.15). The portrayal of motherhood in the media affects societal perceptions of women and how women perceive themselves, with mothering reinforcing women’s gender identity (Douglas and Michaels, 2004; Greenlee, 2014; McMahon, 1995). In India, despite the glorification of motherhood (Altekar, 1959), mothers still face discrimination linked to caste, class, and geography (Krishnaraj, 2010).

Detrimental effects of motherhood

In India’s patriarchal and collectivist society, women are expected to handle domestic responsibilities (Samantroy, 2020). Earning mothers experience more significant parental role overload than their partners (Aryee et al., 2005; Buddhapriya, 2009). Despite an increase in the number of women entering the workforce, they remain a smaller segment than men and are underrepresented in decision-making roles (Rajadhyaksha and Bhatnagar, 2000). Urban millennial men still lag in sharing childcare and household duties (Yarrow, 2018). With limited childcare options and rigid work schedules, earning women in India face significant stress before and after work (Nipun Bharat, 2021; Rout et al., 1999). Mothers are still seen as the primary caregivers (Krishnaraj, 2010), adding to motherhood’s ‘invisible labour’ (Pandey, 2020; Sarkar, 2020).

Beneficial effects of motherhood

However, there is also some evidence that motherhood is viewed in a positive light. Studies suggest benefits such as increased male involvement in child-rearing (Das and Žumbytė, 2017), contribution by earning mothers to family income (Mathur, 1992), and motherhood boosting women’s careers and confidence in managing both work and family (Das & Mohan, 1991). One of the reasons motherhood is viewed optimistically as an institution is that it serves as an alternative source of female identity, involving decision-making in child-rearing practices (Ghosh, 2016). Therefore, in female-led households, motherhood can be somewhat fulfilling as it gives women a degree of influence over their children’s well-being (Choudhuri, 2014). According to the work-family enrichment model, these dual roles enable women to experience positive affect and build personal and psychological resources that they can utilise across various roles (Greenhaus and Powell, 2006).

The literature review suggests that, although numerous studies have explored motherhood and its implications, there are limited investigations into the concept of the supermom (Shah et al., 2025). Besides, most of these studies focus only on the traditional idea, discussing it from only one perspective, i.e., the belief of being able to ‘do it all’. However, no studies analyse mothers’ interpretation of the supermom notion and how important they consider this notion to be in their lives. Thus, we collected data to understand how earning mothers perceive the notion of being a supermom and whether they view it as detrimental or beneficial for their personal and professional lives.

Method

Research design

In this paper, motherhood refers to heterosexual relationships within the framework of socio-legal marriage and where paid work occurs outside the home. Also, we have made a deliberate choice to use the term “earning mothers” to describe our study respondents instead of “working women” to acknowledge the often-overlooked “invisible labour” (Dean et al., 2022) that women perform - encompassing childcare, housework, and emotional and social caregiving - regardless of their employment status. This decision reflects our commitment to recognising the full spectrum of women’s contributions, highlighting their invaluable roles at home and in the workplace as we define the target population of our study.

The data for this study were collected as part of a larger research project on earning mothers, and this paper focuses only on the qualitative responses from the project, providing a nuanced understanding of the supermom notion in the Indian context. Symbolic interactionism emphasises that people construct their perceptions and interpretations through social interactions, with subjective meaning at its core. This is the premise underlying the analysis and discussion of our findings. Patton (2002) explains that individuals “construct shared meanings through their interactions, and these meanings become their reality” (p. 112).

Blumer (1969, p. 2) outlines three fundamental principles of this approach: first, people act based on the meanings things hold for them; second, these meanings emerge from social interactions; and third, individuals interpret and refine these meanings through personal experiences. These principles highlight the significance of examining how individuals attribute meaning to objects, events, and experiences. Reconstructing these subjective perspectives provides valuable insights into social realities (Flick, 2006, p. 67; Pascale, 2011). Symbolic interactionism has been widely applied in sociology, anthropology, criminology, psychology, and education (Angrosino, 2007; Pascale, 2011; Willis et al., 2007).

The central research question guiding this study is to explore the meanings that mothers attribute to the notion of the “supermom,” the significance they assign to this concept in their lives, and whether they perceive it as a supportive ideal or a potentially harmful expectation. We divided the central research question into three broad qualitative questions as presented below. A pilot study with 10 earning mothers used the same inclusion criteria, resulting in minimal changes to the qualitative questions. The final qualitative questions were the following:

1) Who is a ‘supermom’ to you? This question aimed to capture how earning mothers defined the notion of supermom.

2) Must you be a ‘supermom’ to succeed in work, family, and life? This question aimed to understand the viewpoint of the earning mothers about how essential it is to be a supermom to succeed in various life domains. We considered success in work as doing one’s job efficiently and progressing towards career goals, success in family as handling home responsibilities and relationships with children well, and success in life as dealing with and managing various life challenges.

3) Is being a ‘supermom’ beneficial for achieving success in personal and professional life, or is it a trap? This question aimed to understand what meaning earning mothers attach to the supermom notion and whether they perceive it as beneficial or a trap, drawing from their lived experiences based on interactions with family members, peers, and significant others at work. We considered success in terms of a sense of achievement and fulfilment in their personal and professional roles.

Sample selection

Data for the study were collected from earning mothers from the urban areas using convenience and snowball sampling through the authors’ personal and professional networks. The earning mothers were assured of confidentiality and anonymity, and we obtained their written consent via a Google form. Therefore, informed consent was obtained from all the earning mothers through this online process. An information sheet outlining the purpose and details of the study was presented at the beginning of the survey, followed by an informed consent form. The earning mothers were asked to indicate their consent by selecting either “Yes” or “No.” Only those who chose “Yes” were included in the study, confirming their voluntary agreement to participate. The earning mothers were also informed that they could withdraw from the survey at any point without any consequences. Initial participants recruited additional participants from their referrals. The sampling included Indian-earning mothers aged 25 to 50, fluent in English and engaged in full-time or part-time paid employment or self-employment. Earning mothers could be married, partnered, divorced, separated, or single.

Data collection

We created a preliminary email list and sent the questionnaire to potential participants, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity and subsequently additional data were obtained through referrals. We collected data online from 322 earning mothers who provided written consent through Google Forms to participate in the study voluntarily and data was collected between May 14, 2024 and May 31, 2024. Data was collected after the study was approved by FLAME University’s Institutional Review Board. After data cleaning the final sample resulting in 305 usable responses.

Sample description

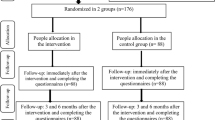

The average age of earning mothers was 41 to 45 years, with 47.4% aged 45 to 50. Approximately 94% were married, 4.6% were divorced or separated, and only 1% were single or unmarried. From the sample, 56.5% had two children, and 41.5% had one child. Nearly 50% held a postgraduate degree, and 80.4% were in full-time employment, with 89.9% working in the private sector. They averaged 43 working hours per week over 5.56 days. One-third had been with their current organisation for up to 5 years, while 34% had over 20 years of work experience spanning various employment sectors (see Fig. 1).

Data analysis and results

Overview of the steps in developing the coding system

The data were screened for missing or incomplete responses, resulting in the exclusion of 35 incomplete definitions of the supermom notion. The remaining 270 out of 305 responses were retained and analysed inductively. Qualitative data regarding the meanings that mothers attribute to the notion of the “supermom,” the significance they assign to this concept in their lives, and whether they perceive it as a supportive ideal or a potentially harmful expectation were analysed using content analysis (Mayring, 2000). Manual coding ensured a nuanced understanding, allowing multiple iterations to refine and develop the coding framework. We employed a two-step process in content analysis to provide clarity and alignment with the qualitative questions, resulting in the creation of codes and categories (see Fig. 2)

-

1.

In the first step, we refined the textual units for each of the usable 270 responses into clear, concise statements without losing the original meaning of the textual units. We identified keywords based on the statements, and then specific codes emerged from the perspectives of earning mothers on the supermom concept. This inductive, bottom-up method identifies emerging patterns and develops fresh insights, making it particularly effective for exploratory studies (Chandra and Shang, 2019). Each developed code distinguished perceptions and beliefs and was named based on relevant literature. For instance, the codes were identified with aspects related to Ability, Competence, and Parenting skills, which we later included within the broader category- Super-competence.

-

2.

In the second step, we organised the codes into broader categories that captured the earning mothers’ attributed meanings and helped contextualise these meanings. For example, in the category of Psychological Resources, codes reflecting shared positive emotions and attitudes were grouped, while for the category of Super-mothers, codes affirming the belief that all mothers are inherently supermoms were grouped.

-

3.

We followed an inclusion and exclusion criterion for coding to ensure consistency, transparency, and analytical rigour. Inclusion criteria involved selecting statements that were relevant to the qualitative questions, reflected participants’ experiences or perspectives, and aligned with the study’s conceptual focus. These included direct statements that reflected patterns contributing to an understanding of key themes. Exclusion criteria, on the other hand, involved omitting irrelevant, repetitive statements without added insight or outside the scope of the study’s objectives. Establishing clear criteria helped maintain the analytical boundaries of the research and supported the development of meaningful and credible findings. For instance, a statement reflecting a happy or smiley approach to juggling work and life was coded under ‘Attitudes’ rather than ‘Positive emotions’, as it aligned most closely with a way of thinking and doing things rather than evoking a specific emotion.

Defining categories and codes

Through content analysis, codes emerged organically from the textual data (see Table 1). The first category, ‘Psychological Resources,’ is derived from the concept of resources, which refers to inherently valuable entities, such as self-esteem, strong relationships, health, social support, and inner peace (Hobfoll, 2002). Within this category, we grouped statements under the codes ‘Positive emotions’ and ‘Attitudes’ related to the concept of a supermom. Positive emotions encompass responses such as interest, contentment, love, and joy, which signify well-being and also contribute to personal growth and success. These emotions are adaptive responses and appraisals of beneficial situations (Cohn and Fredrickson, 2009). As defined by Allport (1935), attitudes are predispositions shaped by experience that influence how individuals perceive and react to situations. They guide behaviour and shape the interpretation of events (Pickens, 2005). This classification of statements referring to positive emotions and attitude is also supported by King et al. (1999), who argue that individuals with sufficient resources are less likely to experience stressful situations that negatively impact their psychological and physical well-being.

The second category, ‘Super-competence,’ is centred on an individual’s ability and capacity, with the concept of competencies requiring both action (a range of alternative behaviours) and the intention to engage in activities (Boyatzis, 2008). Within this category, we included statements related to codes - ‘Ability’ (statements reflecting the ability to do it all, giving one’s best), ‘Competence’ (statements reflecting time management, multitasking, and problem-solving), and ‘Parenting skills’ (statements reflecting aspects of nurturing, upbringing, and parenting responsibilities). Ability can be understood based on recent advances in identity theory, which suggests that people attempt to confirm their identities during social interactions by shaping the situation so that its meaning aligns with how they perceive themselves (Burke, 1991; Stryker and Burke, 2000). The extent to which individuals can act in line with their identities (identity salience) and influence others to recognise that identity depends on the social context (Stryker and Serpe, 1982). Some individuals are better able than others to behave in ways that express their identity. As a result, they are also more capable of shaping situations so that the meanings involved align with their understanding of the situation, themselves, and others (Cast, 2003). Furthermore, Erpenbeck and Heyse (2007) differentiate between ability or capacity and competence, asserting that competent individuals can act independently in unfamiliar situations and solve problems creatively.

Parenting skills can be defined as the ability developed through acquiring a strong foundation of knowledge about the child’s key developmental processes and understanding how development typically unfolds over time (Stevens, 1984). Parenting is understood not simply as a natural process but as a social phenomenon shaped by cultural norms. It is viewed as a continually redefined concept, socially constructed in response to historical, social, and economic changes (Ambert, 1994).

The third category, ‘Super-mothers,’ is based on the idea that being a supermom requires exceptional capabilities to excel in all areas of life. Hays (1996) discusses “intensive mothering” and how expectations from society place immense responsibilities on mothers, regardless of their employment status. Statements reflecting this concept were categorised under the code ‘Motherhood.’ This included statements linking motherhood to being a supermom and considering non-earning mothers to be supermoms, as they also require higher capacities to carry out several roles beyond employment.

The fourth category, ‘Super-balance,’ is rooted in the concept of work-life balance, which is defined as achieving satisfying experiences in all life domains by effectively distributing personal resources, such as energy, time, and commitment, across these domains (Kirchmeyer, 2000). Participants frequently highlighted various aspects of balancing responsibilities as a key part of being a supermom. We categorised these aspects into three codes to capture the nuanced understanding they brought to work life balance: ‘Work-Home Balance’ (statements mentioning the word ‘home’, reflecting balancing work and family responsibilities), ‘Life Domains Balance’ (statements mentioning the word ‘life’, reflecting managing personal, professional, and elderly care), and lastly, ‘Personal-Social Lives Balance’ (statements mentioning the word ‘community’, reflecting juggling work, personal life, and community obligations).

The fifth category, ‘Super-taxing,’ is rooted in the ideology of intensive mothering, which portrays parenting as a child-centred, emotionally demanding, labour-intensive, and time-consuming role, traditionally seen as best suited for women as the primary caregivers. This perspective emphasises that a child’s needs should take precedence over the mother’s, with caregiving responsibilities leaving little room for activities beyond child-rearing, implying that a mother should find complete fulfilment in her child (Hays, 1998). To capture negative perspectives on the supermom notion, we created the codes, which included statements expressing disapproval of this notion; thus, we categorised these differing viewpoints under three codes: ‘Disbelief,’ ‘Myth,’ and ‘Trap,’ based on how participants articulated their critiques of the supermom notion. The justification for naming these codes is as follows: The distinction between believing or disbelieving a proposition is decisive in shaping human behaviour and emotion. When a statement is believed to be true, it serves as a foundation for thought and action; if dismissed as false, it holds no influence and is treated merely as a collection of words. (Harris et al., 2008).

On the other hand, myth can be defined as a symbolic representation of the world shaped by the human mind, serving as a framework for understanding and organising experience. It functions as a charter for behaviour, offering support for established social norms by connecting present situations to meaningful past events. Myths legitimise current obligations and privileges by grounding them in tradition and precedent (Honko, 1972). The term trap describes scenarios within society that function like traps—similar to a fish trap—where individuals, organisations, or entire societies become engaged in specific actions or relationships that eventually turn out to be harmful or undesirable, yet offer no simple way to escape or avoid them (Platt, 1973).

Frequency analysis of codes

We conducted a frequency analysis of codes based on 270 responses (see Table 1) regarding the meanings that mothers attribute to the notion of the “supermom,” the significance they assign to this concept in their lives, and whether they perceive it as a supportive ideal or a potentially harmful expectation. We ensured equal emphasis on each code (Elliott, 2018), allowing for a structured assessment of whether the supermom notion affects success at work and other life domains. Therefore, this analysis offers key insights into how the notion of a supermom is perceived and which aspects are considered most significant. The most prominent category is ‘Super Balance’ with ‘Work-life balance’ (75 statements), ‘Life domains balance’ (13 statements) and ‘Personal social life balance’ (7 statements), highlighting balance as one of the essential aspects of being a supermom. The second most significant category is ‘Super-competence,’ with Parenting skills (61 statements) and Competence (29 statements) and Ability (12 statements), emerging as codes, implying that earning mothers believe that being a supermom requires them to excel in childcare, professional duties and multitasking. ‘Psychological Resources’ further shape perceptions, with Positive emotions (16 statements) and Attitudes (12 statements) reinforcing a positive view of motherhood. However, some participants strongly challenge the supermom notion, as seen in codes like Disbelief (5 statements), Myth (12 statements), and Trap (7 statements), indicating scepticism toward the societal pressure associated with this role. The category ‘Super-mothers’ had the least number of statements (21). The frequency analysis suggests that while many embrace the supermom identity, others recognise its unrealistic and burdensome expectations.

Qualitative question 1: Who is a ‘supermom’ to you?

Definitions: Understanding beliefs regarding the supermom notion

Content analysis of 270 usable responses uncovered how earning mothers define and perceive the notion of supermom. The statements reflected the subjective meanings they attached to the notion of a supermom. Some earning mothers described a supermom as someone who fulfils her responsibilities while experiencing positive emotions. As a result, 16 statements related to happiness, love, empathy, and satisfaction were categorised under the code ‘Positive emotions.’ Meanwhile, statements emphasising the importance of maintaining a positive attitude while balancing, juggling, and managing responsibilities, along with a calm and confident mindset, were placed under ‘Attitudes.’ The ‘Attitudes’ code encompassed 12 statements about managing multiple roles positively, reflecting self-growth, self-care, ambition, and preserving dignity. Selected representative quotes reflecting these codes are presented below:

“A supermom is the one who handles the office, home, children, family, friends, parents - everything right from morning to night and makes everyone happy, including herself. ”

Indian Navy Officer and mother of two

“A supermom is a mom who creates a beautiful balance between her own space, taking care of herself, like food, exercise, mental health, work, and her family. Each supermom has their way of balancing. There is nothing right or wrong about it.”

Freelance Artist and mother of one

“A supermom is emotionally balanced and physically healthy even after job and home responsibilities.”

Professor & HoD and mother of two

The above statements (16 for Positive emotions and 12 for Attitude) imply that some earning mothers associate the supermom notion with successfully managing multiple roles while maintaining a positive attitude and deriving emotional fulfilment. Through this finding, we argue that rather than viewing the supermom notion as an unattainable standard, some earning mothers assert that each mother develops her unique approach to these demands. Many explicitly link the concept to positive emotions, arguing that a true supermom does not just fulfil multiple responsibilities but does so with a sense of peace, satisfaction, and happiness. Furthermore, the earning mothers emphasise that emotional stability, confidence in decision-making, and the ability to provide love and comfort are essential qualities. Notably, the emphasis on self-care in the quotes above challenges the traditional expectation that mothers must constantly sacrifice for others, pointing to a healthier approach towards motherhood. Thus, their perspectives reject an unhappy and dissatisfied definition of a supermom in favour of a more emotionally fulfilling interpretation supported by psychological resources.

Furthermore, the data revealed two critical dimensions in defining the notion of a supermom, challenging conventional assumptions in the two categories of ‘Super-mothers’ and ‘Super-balance’. First, 21 earning mothers rejected the idea that employment status determines whether a mother is a supermom, arguing that all mothers embody this role, regardless of their formal employment status. Therefore, the category of ‘Super-mothers’ implies that some earning mothers believe that all mothers can be considered supermoms because motherhood, regardless of employment status, involves continuous emotional labour, caregiving, and household management. Research indicates that stay-at-home mothers experience time pressure and emotional demands similar to those of working mothers (Nomaguchi and Milkie, 2003) and that the mental load of managing family life primarily falls on women (Daminger, 2019). Therefore, the category of ‘Super-mother’ acknowledges all mothers as supermoms, highlighting the significance of their often-invisible (Pandey, 2020; Sarkar, 2020) contributions to family and society. This perspective disrupts narratives that equate professional work with greater worth, instead emphasising all mothers’ diverse and equally demanding responsibilities.

Second, the ‘Super-balance’ category (total statements for codes Work-home balance 75, Life domains balance 13, Personal-social lives balance 7) reinforced that being a supermom is not about relentless self-sacrifice but skillfully managing multiple life domains. Research shows successful working mothers often rely on time management, support systems, and adaptive strategies to manage competing responsibilities (Damaske, 2011). Moreover, the notion of a supermom is increasingly redefined to include self-care and boundary-setting as essential components of sustainable parenting (Christopher, 2012). This perspective shifts the focus from martyrdom to mastery in managing diverse life roles. Furthermore, earning mothers in our study insisted that there is no single correct way to achieve this balance, reframing motherhood as an individualised and adaptable experience rather than a rigid ideal. By integrating self-care and community contribution into the definition, these perspectives challenge the traditional notion that a mother’s success is measured solely by her service to others. Instead, they indicate that the earning mothers view motherhood as multidimensional and self-sustaining as it helps them achieve personal fulfilment as well as perform multiple roles. The selected representative quotes below illustrate this view, emphasising self-care, mental well-being, and a broader social impact as essential components of the supermom identity.

“All moms are supermoms - whether working or non-working.”

Full-time Professor and mother of one

“A supermom is a woman who successfully manages the household, cares for and creates an environment that is most healthy for herself, and her family (extended too) while holding a job or being active in her community, constantly making an impact both towards people close to her and society in general.”

Proprietor in Education and mother of one

Earning mothers asserted that abilities (12 statements) are fundamental to the supermom identity, rejecting that motherhood is solely defined by sacrifice or endurance. As reflected in the code ‘competence’ (61 statements), they emphasised that being a supermom requires fulfilling multiple roles and actively demonstrating skills such as multitasking, prioritisation, problem-solving, and adaptability. This perspective challenges traditional portrayals of motherhood as instinctual or selfless, instead framing it as a dynamic skill set requiring competence and strategic decision-making. Moreover, 29 statements coded as parenting skills underscore the importance of parenting know-how and nurturing behaviours, further reinforcing that a supermom does parenting effectively along with managing other responsibilities. Based on the frequency analysis, we argue that some earning mothers believe that supermoms develop the necessary abilities and competences to accomplish the goals of their personal and professional roles and they balance responsibility with self-growth. Some selected representative statements are presented below:

“She is determined to make the best of what she has for her family, she has high EQ, she multitasks, she wants to give her children and her family the best, and she will give it her all for it, but she also believes in self-love. She believes she must be happy and at peace with where she is in life to enhance and nurture her family life”.

Marketing Executive and mother of one

“A mother who succeeds in her career and prioritises her children’s educational, cultural, emotional, and social progress is a real supermom.”

Insurance Officer and mother of one

While the supermom belief may appear empowering to some earning mothers, it often places unrealistic, exhausting, and unsustainable expectations according to other earning mothers in this study. According to this other group, the notion that supermoms must seamlessly balance work, household duties, and parenting while maintaining emotional and physical well-being can have significant negative consequences. For several earning mothers, this expectation becomes overwhelmingly super-taxing. Several earning mothers outright rejected the supermom notion, expressing disbelief in its validity—these responses were categorised under the code ‘Disbelief’ (5 statements). Others dismissed the supermom ideal as a mere illusion, stating that it does not exist in their reality; these perspectives were grouped under the code ‘Myth.’ (12 statements). The following selected representative statements illustrate these sentiments:

“There is nothing like a supermom. Women have been blessed with some skills; some they learn in progression. She cannot balance everything. Compromises must be made, and this takes a toll on her. She cannot be enough and cannot fit into all roles. She certainly is enough to be called a human. Society expects her to be sufficient in everything, everywhere, and for everyone, which is a myth. Breaking the stereotypes is what is needed. To be gentle towards women and not expect everything out of them.”

Consultant- Learning & Development and mother of two

“There is nothing like a Supermom or Superwoman in this world. When you prioritise work, you tend to compromise life and family. When you give priority to your family, you might not be able to do a great job at work. Achieving a perfect balance in work, life, and family is difficult. So, you change your priorities occasionally to manage things.”

Associate Professor, mother of two

Additionally, some earning mothers viewed the supermom expectation as a ‘Trap’ (7 statements), highlighting the societal pressure placed on working mothers to perform at their best constantly. These earning mothers described how this ideal enforces unattainable standards, making it challenging to seek balance without guilt or judgment. Collectively, these varying viewpoints emphasise the psychological, emotional, and societal burdens that come with the supermom narrative, and the following selected representative statements reflect these viewpoints:

“This concept of supermom should be made obsolete. Ultimately, there are only women who are mothers, trying in their own ways to provide for themselves and their families. It’s absurd to give women different tags or definitions based on their ability to multitask. This supermom tag is the problem, as it creates a mindset that women have to live up to the expectations of their families and society. It is stereotyping women into such categories that causes distress when they fail to live up to this image. A mom is a mom, Period! And she doesn’t need tags to gain identity as a mother.”

Medical Activity Manager and mother of two

“It’s just a societal trap! Everyone tries to achieve success in their own way, and a definition like “supermom” makes one think that it is some kind of competition. I don’t want to be a supermom. I just want to be happy with whatever I can do in my capacity and be in the right balance - work, family, life.”

Co-founder of an IT company and mother of two

In conclusion, the codes derived from the qualitative responses and their frequency analysis revealed both positive and negative perceptions and beliefs regarding the supermom notion. The presence of these varied perceptions highlights the complexity of the concept. It underscores the need for a nuanced interpretation to determine its impact on mothers’ success in both their professional and personal lives. This exploration offers valuable insights into the multifaceted experiences of earning mothers and their relationship with the idea of being a supermom.

Qualitative question 2: Must you be a ‘supermom’ to succeed in work, family, and life?

We conducted another frequency analysis of all 305 responses (see Table 2) to categorise the responses. The answer to the question was either ‘yes’ or ‘no’, which provided a basis for the third qualitative question and helped clarify the segregation of responses. The ‘yes’ responses positively impacted this group of mothers and were noted as a beneficial perspective for succeeding in work, family, and life. Similarly, ‘no’ responses were considered detrimental to this group of mothers and were noted as such. To minimise researcher bias, we enlisted two independent student coders who were trained in the coding process and were provided with relevant literature on the supermom notion. They were instructed to code the ‘yes’ statements reflecting a positive view (beneficial perspective) as 1 and ‘no’ statements reflecting a negative view (detrimental perspective) as 0. Following best practices in qualitative data analysis (O’Connor and Joffe, 2020), we assessed intercoder reliability, achieving a 95% agreement rate. We included the responses that received consistent coding and excluded those with discrepancies. The subsequent frequency analysis (see Table 2) revealed that 51% of respondents viewed the supermom notion positively, while 49% expressed a negative perception, indicating a nearly equal division of opinions.

Qualitative question 3: The role of the supermom notion in achieving success

We analysed the responses to whether being a supermom is beneficial for success in personal and professional life or a trap. We found that the responses revolved around two main perspectives, as seen in the findings for qualitative question 2 (see Table 2). As explained earlier, from a beneficial perspective, we considered statements that highlight the positive aspects and advantages of the supermom notion to achieve success in work, family, and life. Nearly half of the earning mothers (51%) perceive the supermom notion as a valuable and empowering concept that enables mothers to balance their personal and professional responsibilities successfully. As some earning mothers expressed, being a supermom helps juggle motherhood and career roles, allowing women to provide for their families while maintaining a sense of achievement. Some earning mothers highlighted the importance of seeking support from elders or helpers, emphasising that managing multiple responsibilities does not have to be a solitary struggle. Instead, the more a mother balances her various roles, the more she grows and explores different aspects of her life, personally and professionally. From this beneficial perspective, we can infer that the supermom notion is not about perfection but about adaptability, resourcefulness, and fulfilment, making it a beneficial mindset for those who embrace it. Some selected representative statements reflecting this beneficial aspect are presented below:

“Being a supermom is useful as it helps juggle the role of mother and working successfully to provide for her family.”

Full-time Assistant Professor and a mother of two

“A supermom manages everything like the house, family, children’s studies, and her career, trying to manage things with others’ help, like our elders or helpers, etc. It is beneficial as the more you get involved, the more you explore your life - personally or professionally”.

Full-time Englishteacher and a mother of three

To the same question, another set of earning mothers (49%) opined that the supermom notion is not required to succeed in work, family and life. They perceive the notion as imposing an unrealistic and exhausting standard on mothers, often leading to undue pressure. As some earning mothers pointed out, the expectation of being a supermom is a trap, leaving little room for rest and self-care. The responses reflected that the belief that mothers must excel in every aspect of life without faltering is unattainable and detrimental to their well-being. Another mother emphasised that success stems from a healthy mindset and continuous growth, not from an impossible ideal of perfection. This can be interpreted as viewing mothers as infallible beings who must flawlessly juggle work, home, and personal responsibilities, ignoring their human limitations adds to their stress. Expecting mothers to never make mistakes and be perfect in every role is not only unfair but also absurd according to some earning mothers. Conclusively, these perspectives highlight the damaging effects of the supermom expectation, reinforcing the idea that it is more of a myth than an empowering reality. Some selected representative statements are presented below:

“Success comes from a healthy mindset and motivation to keep improving. Being a mother does not mean being a superhuman. She is a normal person, just like anyone else. Expecting her not to make any mistakes or to be perfect in every category is absurd. So it is a myth.”

Accounts Head and a mother of two

“Supermom is definitely a trap…You can’t be a superhuman being. One needs time to rejuvenate and have lower expectations of themselves.”

Part-time teacher and a mother of one

Discussion

Motherhood has long been central to a woman’s identity, where her worth is often tied to caregiving (Uberoi, 2006). The notion of ‘supermom’, as imposed by society, familial norms, collective values, and projected by the media, further reinforces the expectation that women can balance caregiving and economic contributions (Radhakrishnan, 2009). The desirability for a mother to be a perfect person in all spheres of life thus brings about more challenges, negative emotions, stress and burnout. The objective of our study was to understand how earning mothers themselves interpret the notion of being a supermom and what significance they attach to it. Content analysis of data collected from 305 earning mothers in urban India unravelled the subjective meanings they attach to the ‘supermom’ notion, offering a deeper understanding of the perceptions towards this concept. Understanding how mothers define and navigate this concept provides valuable insights into the evolving dynamics of motherhood, work, and societal expectations in India. The following paragraphs discuss key findings of the study and their contribution to the literature.

First, our findings challenge prevailing narratives in motherhood literature by indicating that earning mothers in India do not necessarily accept the societal and media-driven supermom ideal, but instead actively construct their own definitions. Most of them interpret the notion in ways that are more complex and elaborate than the traditional definition of ‘doing it all’ (Radhakrishnan, 2009). Moreover, these constructed meanings differ for different individuals. They may define the notion in terms of psychological resources, super-competence, super-balance, super-taxing or just motherhood itself. Thus, contrary to the dominant discourse on the supermom notion as a unidimensional construct, our findings highlight a more nuanced reality. The subjective and multiple interpretations of the supermom notion among earning mothers contribute to the interdisciplinary literature on organisational behaviour, feminism, and motherhood (Adhikari, 2022; Greenberg et al., 2021; Sharma and Dhir, 2022).

Second, our findings reveal that earning mothers are divided in their views of the supermom notion. While some see it as detrimental and a trap, many others see it as beneficial. In our study, we received an equivalent number of responses for the positive and negative perceptions. The results contradict the current literature, which primarily indicates a negative perception of the notion as an unrealistic and burdensome expectation (Basu, 1995; Iyer, 2013). Our study reveals that individuals are likely to view it positively as much as negatively. The difference of opinion can be an outcome of different interpretations of the notion. The difference may possibly reflect the intersectional inequalities the mothers have experienced in their lives, such as economic status, social class, educational resources, and the number of children (Schmidt et al., 2023), as well as their social interactions. By highlighting the presence of both negative and positive perspectives about the notion of supermom, our study contributes to the motherhood literature (Bhaumik and Sahu, 2025; Sharma and Dhir, 2022).

Third, our findings underscore that earning mothers may perceive the supermom notion in multiple positive ways. They may associate it with positive emotions, attitude, competencies, parenting skills, and work-life balance across different aspects of life (Table 1). Many of the earning mothers affirmed that embracing the supermom role fosters competence, satisfaction and happiness. They viewed it as empowering and linked it to self-growth, problem-solving, multitasking, and balance in various life domains. For them, juggling multiple roles was not a burden but a source of pride, dignity and fulfilment. These results, however, contradict existing studies that highlight its adverse effects, including stress and burnout (Dugan and Barnes-Farrell, 2020), guilt (Maclean et al., 2021), unfair division of labour (Brailey and Brittany, 2019; Pandey, 2020) and sacrifice (Sarkar, 2020). The findings suggest that the notion of the supermom can be viewed in multiple positive ways, rather than only negatively, thereby contributing to the motherhood literature (Shah et al., 2025).

Fourth, we did not find any conclusive evidence on the significance of the supermom notion for earning mothers. The mothers’ responses suggest that the importance of the supermom notion may vary across earning mothers (Table 1). Some viewed it as a super capacity to excel in all roles or balance different life domains. A few viewed it as the ability to manage emotions and maintain a positive attitude. Some others viewed it as just another term for motherhood, applicable to every mother who handles multiple responsibilities. Regardless of how they defined the notion, some believed in its importance and benefits. In contrast, others did not attach any significance to it, either because they viewed it as a myth or a trap, or because they were indifferent to the concept. Thus, the results suggest that the supermom notion may not hold the same significance for everyone, despite media projections or societal expectations. By offering a more complex, realistic, and divided perspective on how earning mothers view the supermom notion, we extend motherhood scholarship. This insight also opens new avenues for understanding how contemporary mothers may perceive their identities and engage with their roles.

Fifth, we used symbolic interactionism as the methodology to understand the beliefs about the supermom notion. Symbolic interactionism emphasises that the social norms are not fixed but instead constructed through repeated social exchanges, and that they can shape an individual’s perceptions and beliefs. As Burke (1991) states, individuals consistently endeavor to modify their activities and behaviours to ensure that feedback from others confirms the identities they project. From a symbolic interactionist perspective (Flick, 2006), the notion of the supermom is shaped through daily social interactions.

Women who receive affirmation and positive reinforcement for their ability to juggle multiple responsibilities often internalise and project strengthened versions of the “supermom” identity. Positive evaluations from family, peers, and colleagues regarding their performance in traditionally feminine roles can bolster both their commitment to these roles and their self-esteem. From a symbolic interactionist perspective, such identity validation serves as a potent social reward. Empirical studies suggest that among various forms of social reinforcement, affirmations that confirm one’s identity (e.g., being recognised as a “good mother,” “good wife,” or “good friend”) are particularly influential in shaping self-concept and behaviour (McCall and Simmons, 1978). Thus in our study, the mothers’ responses reflected their viewpoints, which were possibly based on their lived experiences of interactions in multiple roles, both within the family and as working professionals.

Practical implications

As the supermom notion persists, its perceptions can shape the actions and behaviours of earning mothers. The fact remains that earning mothers balance the home and work front. Women’s health, leisure, and recreation highlight two key aspects: the considerable effort a woman invests as a mother, wife, and homemaker, and her entitlement to rejuvenate her energy and reserve personal time for herself as an individual (Kasturi, 1995). From an individual earning mother’s perspective, using informal sources of social support, such as family and friends’ support as well as formal support networks can go a long way in reducing the adverse psychological effects such as anxiety related to the dual burden that they may experience (Shamir Balderman and Shamir, 2024). Institutions can foster supportive practices to counter stress related to the roles of motherhood and employment. The government maternity policies though timely, there is a need for implementation of additional incentive programs and policies to support career growth for mothers in both the public and private sectors. The media can showcase different perspectives of earning mothers on the ‘supermom’ notion through advertisements, TV shows, and films, to discourage a unidimensional perspective while highlighting the importance of emotional, social, and institutional support that they deserve.

Additionally, organisations offering women’s leadership training can boost self-esteem and self-efficacy in earning mothers, helping them thrive personally and professionally. Family and marriage counselors can promote awareness among family members to create a supportive environment for mothers. Diversity, equity, and inclusion agencies can develop programs that recognise and reward earning mothers while offering resources to help them manage multiple roles. Organisations can also foster a supportive ecosystem in recruitment, performance evaluation, and work arrangements to help mothers balance their responsibilities more efficiently and effectively.

Limitations and future directions

The study’s reliance on snow-ball and convenience sampling limits the generalisability of its findings, as the data primarily reflect the experiences of well educated, well-compensated mothers from middle to upper-class backgrounds. This narrow demographic focus may not capture the diverse realities of working mothers across different socio-economic strata. Additionally, the absence of data on critical socio-cultural factors, such as caste or city of employment, leaves significant gaps in understanding how these socio-cultural elements shape perceptions of the supermom notion.

Another limitation of the study is the absence of in-depth interviews, which restricted the depth of exploration into participants’ lived experiences. The insights from this study are based on three open-ended questions and their descriptive answers and this approach may not sufficiently capture the complexities of the development of the supermom notion or its influence on success across various life domains. In future, conducting in-depth interviews will be particularly valuable in uncovering the personal narratives, challenges, information regarding how their social interactions can shape their perceptions regarding the supermom notion and coping mechanisms that quantitative methods might overlook. Moreover, future studies can examine the implications of beliefs about the supermom notion in the lives of mothers and how these implications may vary depending on whether they view it as beneficial or detrimental. Furthermore, exploring the impact of demographic factors such as marital status, home support, caregiving responsibilities, and socioeconomic status will provide a more comprehensive understanding of how the supermom concept influences success across both professional and personal spheres.

Furthermore, future research can empirically investigate whether a beneficial view of supermom and quality of work and family roles is associated with actual positive outcomes for earning mothers, such as emotional well-being, work-life balance and job satisfaction. As per work-family enrichment theory (Greenhaus and Powell, 2006), positive experiences in one domain can enhance the quality of life in another. Besides, role accumulation theory argues that participating in multiple roles can lead to positive outcomes (Voydanoff, 2001). Studies also indicate that it may reduce distress (Barnett et al., 1992; Voydanoff and Donnelly, 1999), and quality of roles may improve physical and psychological health (Barnett and Hyde, 2001; Perry-Jenkins et al., 2000).

Conclusion

Although scholarly literature and societal values define the supermom notion as the ability to ‘do it all,’ our study reveals a more nuanced reality. We found that earning mothers in India a) interpret the supermom notions in several ways, b) vary in their opinion about the notion (ranging from beneficial to detrimental, myth and a trap), c) may perceive the notion in multiple positive ways that contradict prior studies, and d) differ in the extent to which they attach significance to it. Our findings highlight the complexity of the supermom notion, and suggest that it may be shaped by individual circumstances and personal beliefs. Future research can further explore how these perceptions influence mothers’ personal and professional lives, and thus give us deeper understanding about the criticality of the supermom notion, and its role in the life of earning mothers.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available at Shah, Dr Shalaka (2025), “Data of Indian Earning Mothers & Supermom Notion”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/bx8s53223j.1.

References

Adhikari H (2022) Anxiety and depression: comparative study between working and non-working mothers. ACADEMICIA: Int Multidiscip Res J 12(2):273–282

Agarwal B (2021) Livelihoods in COVID times: gendered perils and new pathways in India. World Dev 139:105312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105312

Allport GW (1935) Attitudes. In Murchison C. (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 798–844). Clark University Press

Altekar AS (1959) The position of women in Hindu civilization: From prehistoric times to the present day. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers

Alvesson M, Willmott H (2002) Identity regulation as organizational control: producing the appropriate individual. J Manag Stud 39(5):619–644

Ambert A-M (1994) An international perspective on parenting: social change and social constructs. J Marriage Fam 56(3):529–543. https://doi.org/10.2307/352865

Angrosino M (2007) Doing ethnographic and observational research. Sage

Aryee S, Srinivas ES, Tan HH (2005) Rhythms of life: antecedents and outcomes of work-family balance in employed parents. J Appl Psychol 90(1):132–146

Barnett RC, Hyde JS (2001) Women, men, work, and family. Am Psychol 56:781–796

Barnett RC, Marshall NL, Sayer A (1992) Positive spillover effects from job to home: a closer look. Women Health 19(2/3):13–41

Basu A (1995) The Challenge of Local Feminisms: Women’s Movements in Global Perspective. Westview Press

Belkin L (2003) The opt-out revolution. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/10/26/magazine/26WOMEN.html

Berger PL, Luckmann T (1966) The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Anchor Books

Bhattacharji S (2010) Motherhood in Ancient India. In: M. Krishnaraj (ed.) Motherhood in India: glorification without empowerment? Routledge India, pp 45–67

Bhaumik S, Sahu S (2025) Lived experiences of urban working mothers during pandemic: a matricentric exploration in the indian context. Women’s Stud Int Forum 109:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2025.103067

Blumer H (1969) Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and methods. Prentice Hall

Boyatzis RE (2008) Competencies in the 21st Century. J Manag Dev 27:5–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710810840730

Brailey C, Brittany S (2019) Women, work, and inequality in U.S.: revisiting the “Second Shift. J Sociol Soc Work 7(1):29–35

Buddhapriya S (2009) Work-family challenges and their impact on career decisions: a study of Indian women professionals. Vikalpa: J Decis Mak 34(1):31–46

Burke PJ (1991) An identity theory approach to commitment. Soc Psychol Q 54:239–251

Cast AD (2003) Power and the ability to define the situation. Soc Psychol Q 66(3):185–201. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519821

Chakravarti U (1993) Gendering Caste Through a Feminist Lens. Stree Publications

Chandra Y, Shang L (2019) Inductive coding. In: Qualitative Research Using R: A Systematic Approach. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3170-1_8

Chatterjee P (1993) The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories. Princeton University Press

Chodorow NJ (1995) Gender as a personal and cultural construction. Signs 20(3):516–544. https://doi.org/10.1086/494999

Choudhuri T (2014) Women workers in urban informal sector: The case of workers in rice mills and nursing homes in Burdwan [PhD thesis in sociology.]. Vidyasagar University. Medinipur

Christopher K (2012) Extensive mothering: employed Mothers’ constructions of the good mother. Gend Soc 26(1):73–96

Cohn MA, Fredrickson BL (2009) ’ Positive Emotions’. In: S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (2nd edn). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195187243.013.0003

Damaske S (2011) For the Family? How Class and Gender Shape Women’s Work. Oxford University Press

Daminger A (2019) The cognitive dimension of household labor. Am Sociol Rev 84(4):609–633

Das M, Žumbytė I (2017) The motherhood penalty and female employment in urban India. Policy Research Working Paper, 8004

Das & Mohan (1991) Gender and Work-A research Paper presented at National Seminar: Kuvempu University, Karnataka, India as quoted. In: Sudha DK (ed.) APH Publishing Corporation

Dean L, Churchill B, Ruppanner L (2022) The mental load: building a deeper theoretical understanding of how cognitive and emotional labor overload women and mothers. Community Work Fam 25(1):13–29

DeMeis DK, Perkins HW (1996) Supermoms” of the Nineties: homemaker and employed mothers’ performance and perceptions of the motherhood role. J Fam Issues 17(6):776–792. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251396017006003

Desai N (2010) Women and Society in India. Ajanta Publications

Djafarova E, Trofimenko O (2017) Exploring the relationship between self-presentation and self-esteem of mothers in social media in Russia. Comput Hum Behav 73:20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.021

Douglas SJ, Michaels MW (2004) The mommy myth: The idealization of motherhood and how it has undermined women. Free Press

Dugan AG, Barnes-Farrell JL (2020) Working mothers’ second shift, personal resources, and self-care. Community, Work Fam 23(1):62–79

Edley P (2004) Entrepreneurial Mothers’ Balance of Work and Family: Discursive Constructions of Time, Mothering, and Identity. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452233123.n15

Elliott V (2018) Thinking about the coding process in qualitative data analysis. Qual Rep 23(11):2850–2861

Erpenbeck J, Heyse V (2007) Wege der Kompetenzentwicklung. Waxmann Verlag

Fernande D (2017) Aishwarya Rai Bachchan is a supermom: Aaradhya is my top priority, says actor. The Indian Express. https://indianexpress.com/article/entertainment/bollywood/aishwarya-rai-supermom-aaraadhya-bachchan-abhishek-bachchan-4919265/

Flick U (2006) An Introduction to Qualitative Research. Sage

Ghosh B (2016) The Institution of Motherhood: a critical understanding. In: Manna S, Patra S (eds.) Motherhood– Demystification and Denouement (1st edn). Levant Books, pp 17–29

Glenn EN, Chang G, Forcey LR (1994) Mothering: Ideology, experience, and agency. Routledge

Greenberg D, Clair JA, Ladge J (2021) A feminist perspective on conducting personally relevant research: working mothers studying pregnancy and motherhood at work. Acad Manag Perspect 35(3):400–417

Greenhaus JH, Powell GN (2006) When work and family are allies: a theory of work-family enrichment. Acad Manag Rev 31:72–92

Greenlee JS (2014) The Political Consequences of Motherhood. University of Michigan Press

Harris S, Sheth SA, Cohen MS (2008) Functional neuroimaging of belief, disbelief, and uncertainty. Ann Neurol 63(2):141–147

Hauser ML (2005) Confessions of Super Mom. New American Library

Hays S (1996) The cultural contradictions of motherhood. Yale University Press

Hays S (1998) The cultural contradictions of motherhood. Yale University Press

Hobfoll SE (2002) Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev Gen Psychol 6(4):307–324

Honko L (1972) The problem of defining myth. Scr Inst Donneriani Abo 6:7–19. https://doi.org/10.30674/scripta.67066

Iyer L (2013) I’m pregnant, not terminally ill, you idiot! Amaryllis

John ME (ed.) (2008) Women’s Studies in India: A Reader. Penguin

Johnston DD, Swanson DH (2003) Undermining mothers: a content analysis of the representation of mothers in magazines. Mass Commun Soc 6(3):243–265

Kasturi L (1995) Development, patriarchy, and politics: Indian women in the political process, 1947-1992. Centre for Women’s Development Studies. http://www.cwds.ac.in/OCPaper/DevelopmentPatriarchyandPolitics.pdf

King DW, King LA, Foy DW, Keane TM, Fairbank JA (1999) Posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of female and male Vietnam veterans: risk factors, war-zone stressors, and resilience-recovery variables. J Abnorm Psychol 108:164–170

Kinser AE (2008) Mothering feminist daughters in postfeminist times. J Motherhood Initiative Res Community Involvement, 10(2). https://jarm.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/jarm/article/view/18038

Kirchmeyer C (2000) Work-life initiatives: greed or benevolence regarding workers’ time? In: Cooper CL, Rousseau DM (Eds.) Trends in organizational behaviour: Time in organizational behaviour. Wiley, pp 79–93

Krishnaraj M (Ed.) (2010) Motherhood in India: Glorification without Empowerment? (1st ed.). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203151631

Lang P (2006) Narrating motherhood(s), breaking the silence: Other mothers, other voices. International Academic Publishers

Maclean EI, Andrew B, Eivers A (2021) The motherload: Predicting experiences of work-interfering-with-family guilt in working mothers. J Child Fam Stud 30:169–181

Mathur D (1992) Women, Family and Work. Rawat Publications

Mayring P (2000) Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, http://qualitative-research.net/fqs/fqs-e/2-00inhalt-e.html

McCall GJ, Simmons JL (1978) Identities and Interactions: An Examination of Human Associations in Everyday Life (Rev.). Free Press

McMahon M (1995) Engendering motherhood: Identity and self-transformation in women’s lives. Guilford Press

Nipun Bharat (2021) Department of School Education & Literacy, Ministry of Education, Government of India. https://www.education.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/nipun_bharat_eng1.pdf

Nomaguchi KM, Milkie MA (2003) Costs and rewards of children: The effects of becoming a parent on adults’ lives. J Marriage Fam 65(2):356–374

O’Connor C, Joffe H (2020) Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qual Methods 9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

Oliver N (2011) The Supermom Syndrome: an intervention against the need to be king of the Mothering Mountain. In Library and Archives Canada, Published Heritage Branch, Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Heritage Branch

O’Reilly A (2010) Outlaw(ing) motherhood: A theory and politic of maternal empowerment for the twenty-first century. Hecate 36(1/2):17–29

Oxfam India Inequality Report (2020). On women’s backs. https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/Oxfam_Inequality%20Report%202020%20single%20lo-res%20%281%29.pdf

Pandey G (2020) Coronavirus: How India’s lockdown sparked a debate over maids. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-India

Paré ER, Dillaway HE (2005) Staying at home” versus “working”: a call for broader conceptualizations of parenthood and paid work. Mich Fam Rev 10:66–87

Pascale CM (2011) Cartographies of knowledge: Exploring qualitative epistemologies. Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452230368

Perry-Jenkins M, Repetti RL, Crouter AC (2000) Work and family in the 1990s. J Marriage Fam 62:981–998

Pickens J (2005) Attitudes and perceptions. Organ Behav health care 4(7):43–76

Platt J (1973) Social traps. Am Psychol 28(8):641

Porter M (2010) Focus on mothering: Introduction. Hecate, 36(1/2), 5–16

Patton Q (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications

Radhakrishnan S (2009) Professional women, good families: respectable femininity and the cultural politics of a “new” India. Qual Sociol 32(2):195–212

Rajadhyaksha U, Bhatnagar D (2000) Life role salience: a study of dual-career couples in the Indian context. Hum Relat 53(4):489–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700534002

Rich A (1976) Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. Virago Press

Rout UR, Lewis S, Kagan C (1999) Work and family roles: Indian career women in India and the west. Indian J Gend Stud 6(1):91–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/097152159900600106

Samantroy E (2020) Women’s participation in domestic duties and paid employment in India: the missing links. Indian J Labour Econ 63(2):437–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00217-6

Sarkar S (2020) Working for/from home’: an interdisciplinary understanding of mothers in India. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 12(5). https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n5.rioc1s26n6

Schmidt EM, Décieux F, Zartler U, Schnor C (2023) What makes a good mother? Two decades of research reflecting social norms of motherhood. J Fam Theory Rev 15(1):57–77

Shah SS, Chaudhry S, Shinde S (2025) Supermoms—Tired, admired, or inspired? Decoding the impact of supermom beliefs: a study on Indian employed mothers. PLoS ONE 20(4):0321665

Shamir Balderman O, Shamir M (2024) Social support, happiness, work–family conflict, and state anxiety among single mothers during the covid-19 pandemic. Human Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–12

Sharma R, Dhir S (2022) An exploratory study of challenges faced by working mothers in India and their expectations from organizations. Glob Bus Rev 23(1):192–204

Sheer A (2011) Will the real mothers please stand up? In: S. P. Walravens (Ed.) Torn: True stories of kids, career and the conflict of modern motherhood. Coffee town press, pp 81–83

Sinha C (2010) Images of motherhood: The Hindu code bill discourse. In: In motherhood in India: Glorification without empowerment. Routledge, pp 321–346

Skenazy L (2007) That supermom in your ad? Real moms can’t stand her. Advertising Age, pp 28

Srivastava N, Srivastava R (2010) Women, work, and employment outcomes in rural India. Econ Polit Wkly 45(28):49–63