Abstract

With recent advancements in AI capabilities, much analytical and media attention has focused on its ability to produce art. A less explored element is how artists create AI models for interactive artworks. This paper will argue that adopting AI systems has expanded the interactive art form by generating new modes of engagement. Interactive art creates meaning through co-creation between artworks, audiences, and artists. AI’s ability to create independent systems that learn and respond to stimuli allows artists to facilitate dynamic relationships between their works and viewers. This paper will focus on Ian Cheng’s 2018–2019 digital AI installation, BOB (Bag of Belief), as a case study to demonstrate the potential of AI to generate these dynamic relationships. The work consists of a creature with a digital body that interacts with its environment, and an AI model with the appearance of sentience that allows it to act independently and adapt to stimuli. BOB’s AI model increases unpredictability and agency, encouraging social rather than tool-like interactions. Granting artworks increased control and agency represents not a new art form, but a development for interactive art that generates new interaction methods between artworks and audiences. This facilitates exploration into novel themes, including relationships between human and nonhuman intelligences, different models of the mind, and how artworks are understood as new technologies enable them to act independently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: a new frontier in interactive art

Interactive art is defined by the relationship between spectators and artworks, with interaction creating a dialogue where new versions of artworks are collectively constructed (Kluszczynski 2010, p. 2). Artists create situations facilitating viewer engagement, fostering direct relationships with artworks and indirect ones with creators. This engagement constitutes interactive art’s primary medium, a temporally based, process-oriented hypermedium where interaction drives meaning (Hlávková 2021, p. 2). This paper will argue that adopting new media expands interactive art by increasing potential modes of interaction, thereby allowing new themes to emerge. Artificial intelligence has caused such an expansion by enabling artworks that act independently and form dynamic relationships with viewers. While this does not constitute a new art form, it marks a new frontier for interactive art.

While interaction is the medium that defines interactive art, physical elements and artifacts structure possible interactions. These structural elements function as media, technologies used to make art that are associated with, but do not define a specific art form (Lopes 2007, pp. 246–247). New media can create new art forms, as with photography, or expand existing ones. For example, digital technology has been adopted into existing art forms with digitally constructed images and songs belonging to visual art and music traditions (Lopes 2009, p. 16, 18). Digital technology has already contributed to interactive art by increasing modes of interaction and facilitating exploration of human-technology relationships (Ahmedien 2024, p. 2). AI integration further expands this by introducing autonomous agents that participate as active co-creators, enabling social interaction with apparently sentient artworks.

Artists creating digital agents with self-authored AI systems provide strong case studies demonstrating dynamic social relationships between artworks and audiences. This paper will use Ian Cheng’s 2018–2019 work, BOB (Bag of Beliefs), as a case study to demonstrate the potential of AI to expand interactive art. Cheng’s self-authored AI model creates a digitally embodied agent that explores how sentience is recognized and the divide between biological and digital entities. BOB’s AI mind and digital body enable it to respond and adapt based on viewer interactions, generating dynamic, social relationships between the artwork and audiences. AI’s ability to create art that acts independently as a free agent expands the methods of participation that artists and audiences can investigate within interactive art. This expansion allows new themes to emerge through interaction, opening new explorations into human–nonhuman interaction, models of mind, and how art is defined and engaged with.

Defining interactive art

The typical gallery experience involves interaction between artists, viewers, and artworks. Mental engagement with a passive art object is a rich form of interaction, but not co-creative. Co-creation is fundamental to interactive artworks because they remain incomplete until participants engage with them (Kluszczynski 2010, p. 2). Meaning is produced through the types of interaction provided, such as navigating within a work or changing its form. Therefore, interaction between artworks and audiences is a primary artistic medium where ideas and themes are generated through engagement.

This paper proposes two necessary conditions to define interactive art: (1) Interaction is a required element for the work and is part of the medium, and (2) Interaction affects the meaning of the work. The first means interactive artworks require participation; the physical construction of the work is not the final product (Kluszczynski 2010, p. 2). The second means the audience’s engagement physically and conceptually changes the work (Wong et al. 2009, p. 180). These conditions preclude artworks where interaction serves functional purposes, such as The Cellini Salt Cellar (1543). Its function of storing and spooning salt is incidental to artistic meaning. Some traditional visual artworks encourage physical engagement, like Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533), which requires the correct vantage point to see its anamorphic skull. However, audience interaction does not influence the work’s meaning and does not function as a medium.

Interactive art’s primary medium is the process-based engagement that emerges through physical and mental co-creation between artworks and audiences. While physical media are not the primary driver of meaning, they are essential for structuring interactions. Sherry Irvine’s description of artistic mediums supports nonphysical elements like interaction, communicating conceptual and thematic content. Physical tools or technologies do not always define artistic mediums; they emerge from the conventions and practices developed through working with certain materials. Irvin argues that the abandonment of many traditional media in contemporary art, and the blurring of boundaries between art forms, has expanded possible artistic mediums to include more nonconventional and nonphysical forms, like using rules for engagement and display (Irvin 2022, p. 63, 128). In interactive art, the structured engagement between viewers and the artwork’s physical components is the artistic medium.

This medium of interaction is process-oriented and temporally based. C. Thi Nguyen’s concept of process art suggests that physical and mental processes can constitute a medium. He argues that esthetic content can emerge from audience engagement, choices, reactions, and movements. Physical components are not the primary vehicle of meaning in such works and exist to enable processes (Nguyen 2020, pp. 1–2). This applies to interactive art where physical features guide engagement through affordances that direct interaction (Boden 2007, p. 218). The temporal element of interactive art aligns with Lenka Hlávková's concept of the hypermedium. Hypermedia relies on real-time processes and exists as long as active engagement continues (Hlávková 2021, p. 2). The physical and mental engagement required for interactive artworks exemplifies this real-time process; once engagement ends, so does the medium. These frameworks present interaction as a temporally based medium requiring active engagement, where meaning emerges through co-creation rather than passive observation.

Early interactive art emphasized physical engagement. This is seen in Roy Ascott’s 1959 Change Paintings, which consist of multiple plexiglass screens with abstract oil-painted elements that viewers overlay to create different visual pairings. While the paintings themselves are not the primary artistic medium, they are necessary elements of the work. They guide the co-creative process of changing plexiglass to create new combinations that allow viewers to explore different creative expressions (Ascott 1964, p. 128). Adopting new technologies can expand possible modes of engagement within interactive art.

Digital interactive art

Digital technology has created new modes of engagement and co-creation for interactive art, causing new themes to emerge through audience participation (Ahmedien 2024, p. 2). Interfaces, sensors, and projections enable real-time reaction to audience input, broadening the possible connections between artworks and viewers, creating sustained interactions and immersive simulations (Ahmedien 2024, p. 2, 9). Lev Manovich notes that interactive digital technology has shifted engagement from passive representation to active simulation through virtual reality systems that encourage physical movement (Manovich 2001, pp. 111–112). Rather than presenting representations of external reality, digital systems can facilitate immersive engagement with what is represented (Manovich 2001, pp. 15–16). These new technologies and systems expand the hypermedium by facilitating new ways to interact with artworks.

In contrast to reactive digital systems, early interactive works such as Change Paintings relied on instrumental interaction where the choices of the artists and the physical media broadly define possible outcomes. This type of interaction reflects Ryszard W. Kluszczynski’s Strategy of Instrument, where objects and interfaces are emphasized for their ability to generate interactions and events rather than how they facilitate communication or reactivity (Kluszczynski 2010, p. 4). In contrast, digital technology has been used to encourage what Xiaobo and Yuelin describe as dynamic interaction systems that can be directly influenced by audiences and have outputs that track and adapt to participant engagement (Xiaobo and Yuelin 2014, p. 167).

The increased reactivity offered by digital technology creates opportunities for new themes to emerge through interaction, like the relationship between humans and technology (Ahmedien 2024, p. 2). Diaa Ahmedien argues that digital interactive art is well-positioned to investigate these relationships by facilitating symbiotic engagement. This is achieved through interaction with digital systems, starting with investigation and adaptation to learn the best means of communication, giving way to an intuitive use of a system’s affordances. This establishes a dialogue where interaction becomes streamlined, and a symbiotic relationship is achieved. Symbiosis creates a space where the relationship between humans and technology can be investigated (Ahmedien 2024, p. 8).

The 2023 artwork Space Odyssey by the creative studio HOLOGRIX demonstrates how reactive simulations expand modes of interaction. The work presents a digital representation of outer space and generates user avatars as abstract shapes. These avatars are manipulated through real-time tracking of participants’ body movements, allowing them to explore and manipulate the virtual space. Ahmedien asserts that, through trial-and-error, participants learn to intuitively use the system, allowing for exploration of the divide between virtual and real space in a dynamic co-creative relationship (Ahmedien 2024, p. 7). While simulations like this have led to more dynamic interaction, they have limited capacity to form social relationships.

How AI expands interactive art

Digital technology has developed interactive art, but AI systems represent a further qualitative expansion by introducing autonomous artworks that act as independent agents (Castellanos 2022, p. 156). Agency is the ability to govern behavior, adapt to new situations, and change thought processes to better navigate the environment (Castellanos 2022, pp. 163–164). Integrating AI systems with digital simulations creates embodied agents: AI systems with a physical or simulated body that exists within and can influence their environment (Sporns and Pegors 2021, p. 75). This builds on the non-instrumental symbiotic relationships generated by digital technology by facilitating dynamic and social relationships that integrate audiences and artworks as autonomous agents that co-create meaning. This causes new emergent meanings beyond investigations into human technological relationships to emerge.

Ian Cheng’s BOB (Bag of Beliefs) demonstrates AI’s ability to generate dynamic, social relationships by presenting an adaptable, digitally created creature with the appearance of sentience. It functions as an embodied agent with a digital avatar that grows and changes based on its experiences and environment. Viewers offer BOB various objects, promoting social engagement where BOB’s behavior is observed and influenced. Cheng’s use of AI to create a creature with its own needs and motivations, ability to learn, grow, and take independent action results in an artwork that mimics intelligence and awareness, encouraging dynamic, co-creative relationships (Cheng 2018).

Audience engagement with BOB (Bag Of Beliefs) illustrates the range of themes AI systems can support in interactive art. Social engagement with BOB’s artificial mind can generate investigations into relationships between non-human minds and viewers. Analyzing BOB’s AI framework and how viewers perceive its behavior as sentient explores different models of the mind and how sentience is constructed and perceived. Finally, interaction with BOB in a gallery setting challenges how art is defined and understood. Its unpredictability and independence disrupt the object-subject relationship where viewers observe and act upon art objects. BOB’s role as an embodied agent anticipates how art might help navigate developing relationships with AI as such systems become more autonomous. These emergent themes expand the concepts and scenarios that interactive art can explore. Interaction with BOB facilitates these themes through its internal systems and digital body, which enables it to foster dynamic relationships.

Conceptualizing AI in art: neural networks and ILP systems

AI systems’ potential for creative thinking and problem-solving to challenge and enhance art production has been a popular subject for those researching the intersection between art and technology (Poltronieri 2022, pp. 29–30). The ethical implications of these systems, like the replacement of artists and bias in data sets, have seen much academic and media interest (Flick 2022, p. 73). Less attention has been paid to artists using AI to create interactive works featuring embodied, expressive agents. The computer scientist Michael Mateas was an early contributor to this topic, coining the term “interactionist AI” in 2001 (Mateas 2001, p. 147). He describes these systems as agents that can interact within the physical or virtual world. He argues for their artistic potential to disrupt the subject-object relationships expected in galleries by imbuing the object with the ability to take independent action (Mateas 2001, p. 1478). While relevant analysis, the accelerating advancement of systems such as neural networks and inductive logical programming necessitates further exploration of how these new systems are applied to artworks.

Neural networks and inductive logical programming (ILPs) are two AI systems artists use for interactive artworks. Neural networks are associated with recent advancements in universal generators like chatbots and art generators. Artists have used these systems as collaborators in symbiotic, co-creative relationships (Chung 2022, p. 263). Inductive logical systems have had less mainstream discussion but have also advanced, improving their ability to interpret new data with minimal background training (Evans and Grefenstette 2018, p. 5598). ILPs can form recognizable logical systems with limited data (Evans 2020, p. 19), making them strong models for creating art with agency and the appearance of sentience, like BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (Cheng 2020).

Neural networks: collaboration in the work of Sougwen Chung

Neural network programming is considered the current “state of the art” for building AI systems and is associated with recent advancements in universal text and image generators. These models use a connected network of “neurons” trained on enormous amounts of data (Santos et al. 2021, p. 122). When information is processed, each neuron is responsible for a specific computation before it feeds the values to the rest of the network. These systems are good at efficiently processing substantial amounts of information but are data-hungry and have trouble adapting (Evans 2020, pp. 18–19). It is also difficult to understand how results were reached because there are thousands of input parameters, and it is not always clear how each one affects the conclusion (Evans and Grefenstette 2018, pp. 5598–5599).

Art generators that produce an image from a text input typically use neural network models (Santos et al. 2021, p. 123). Artists like Sougwen Chung use these systems as co-creators in visual, performance, and interactive artworks (Chung 2022, p. 263). Chung’s interest in AI started when she used machine learning and robotics to develop her drawing and design abilities. Her recent work explores AI and robotics as a collaborative medium (Chung 2022, p. 259). Chung’s ongoing project, Drawing Operations Unit: Generation 1–4 (also known as D.O.U.G._1–4), is an AI program initially trained on a deep learning dataset based on two decades of her art (Chung 2022, p. 263). D.O.U.G one and two focus on mimicry with the neural network learning Chung’s style. D.O.U.G._2 has been used in performances where it was applied to a robotic hand that drew with her as a physical co-creator (Chung 2022, pp. 265–266). D.O.U.G._3 explores collective creation by incorporating data from New York City. Motion vectors from public cameras in NYC were linked to D.O.U.G., and the movement of pedestrians and traffic influenced the drawing systems. In the 2018 work Omnia per Omnia, Chung paints alongside five small robots using D.O.U.G._3 on a large canvas placed on the floor (Chung 2022, pp. 167–168). The work expands collaboration to include the collective movement of a city.

Chung’s use of neural networks advances interactive art by exploring AI-human artistic creative relationships. D.O.U.G can learn and act independently, but its function is to draw and collaborate rather than exist as an independent and reactive entity. An AI art generator can improve its artistic ability and creatively adapt within its field, but it will be limited in other areas. D.O.U.G demonstrates the potential of AI to examine human-technology symbiosis through a collaborative, experimental application of this new media (Ahmedien 2024, p. 2). However, it lacks the broad adaptability associated with living organisms, and the impenetrable logic of neural network systems makes their thought processes hard to understand and relate to (Evans and Grefenstette 2018, pp. 5598–5599). AI does not think like humans, but recognizable internal thought systems benefit social engagement. For these reasons, some artists seeking to create interactive AI art that has the appearance of sentience have looked to different models like Inductive Logic programming.

Inductive logic programming: transparent logical systems

Inductive Logic programming is a symbolic AI based on cognitive psychology and logical systems, contrasting with neural networks that mimic the brain’s structure (Bo Zhang et al. 2021, p. 2). ILP models use rules to train the system to construct logical programs from examples and form axioms. One rule might be, “If it is a pointed leaf, then it belongs to x family of trees.” Positive or negative examples are also provided, like “leaf one has multiple points and is from a maple tree,” and “leaf two is rounded and not from a maple tree.” ILPs are data efficient and follow a recognizable logical system reminiscent of human rational processes, making it easy to understand how their conclusions are reached (Bo Zhang et al. 2021, p. 2). They run into problems when dealing with noisy or ambiguous data where their hard and logical rules can become inflexible to contrary information (Evans and Grefenstette 2018, p. 5599).

ILPs and symbolic AI, in general, have fallen out of fashion, but some researchers continue to improve these models (Bo Zhang et al. 2021, p. 2). The AI researcher Richard Evans has sought to mitigate ILP’s issues with his Differentiable Inductive Logic framework, which was presented in his and Edward Grefenstette’s 2017 paper “Learning Explanatory Rules from Noisy Data” (Evans and Grefenstette 2018, pp. 5598–5599). Their model inserts how neural networks learn into an ILP system, creating a flexible model that can adapt to inconsistent information. This is achieved by letting some logical clauses hold more weight than others. Instead of a positive or negative rule, it is assigned a value along a probability, like a fractional value between 0 and 1. This makes the internal axioms more flexible and easier to adjust with added information (Evans and Grefenstette 2018, p. 5601).

Evan’s model, and ILPs in general, have the potential for artists to create original AI works that fit within the concept of interactionist AI. Compared to the impenetrable logic of neural networks, ILPs use more streamlined logical systems, making their inner workings easier to understand. Recognizing aspects of how we think and interact with our environment as biological life within an artificial mind makes social connections easier. Ian Cheng cites Evan and Grefenstette’s work as a major influence for parts of the AI system used in BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (Cheng 2020).

BOB (Bag of Beliefs)

The conception of BOB came from Ian Cheng’s desire to create art with a nervous system (Cheng 2018). Much of his work centers on using AI as a medium to create unpredictable artworks that can react to stimuli and change (Cheng 2018). His 2015–2017 Emissaries video project series uses AI and cedes control to it within a digital simulation. The three simulations include various characters interacting with a dynamic environment and one protagonist character with objectives. This creates a changing narrative where the protagonist has goals, but the way those goals are reached is not planned (Cheng 2018). While this work explores similar themes to BOB (Bag of Beliefs), it is not interactive as its changing features are self-contained. BOB (Bag of Beliefs) is an interactive AI work that facilitates a dynamic relationship between the viewers and an artwork that appears alive.

When creating BOB, Ian Cheng began by using a creature as a compositional space, treating the life cycle and physical and mental needs as formal elements (Cheng 2018). BOB can be understood in two parts: what is perceived visually, BOB’s animated body and environment, and the AI model, which viewers experience through engagement.

Generating interaction: BOB’s digital embodiment

BOB is displayed on monitors in the gallery, set in an empty white space that becomes more cluttered as its life progresses. The AI system is presented as an embodied agent within a digital simulation, appearing as a snake-like creature within a simple but changing environment. It displays features of biological life as it grows and dies. After the death of BOB, a new iteration will be born. BOB’s digital environment is accessible with a cursor that can influence its movement and give it objects. This interaction is a requirement and a feature as BOB needs proper nutrition to develop physically, and engagement by spectators to mentally develop.

BOB’s body is composed of tube-like spiny segments with an interior ball spring mechanism allowing flexibility and range of movement (Wang 2024). Each of BOB’s body segments has external sensors that react to stimuli, and internal sensors keep track of homeostasis. The body is a swarm intelligence, with each node having some independence and awareness while collaborating. BOB’s design is balanced between alien and organic (Wang 2024). It develops like organic life, starting in a juvenile state with a head and several segments, which increase over time. A fully grown BOB is shown in Fig. 1. This growth has a “fractal” quality, with its body branching outward and acquiring secondary heads (Cheng 2020). An asymmetrical and multiheaded body plan like this is uncommon in nature, highlighting BOB’s inorganic features. Its face has mammalian qualities, with front-facing eyes and a cat-like mouth placed on a worm-like body, creating an alien juxtaposition. These contrasting formal elements cause BOB to be simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar.

The red head on the left is the original face; the gray heads grow as BOB ages. Various items, including shrubs, stones, and fruits, viewers can give to BOB can be seen in the space (Cheng 2020). Cheng (2020) BOB (Bag of Beliefs) https://iancheng.com/bob.

BOB’s digital body is crucial in generating dynamic social relationships, demonstrating the value of embodied AI systems. While its AI system enables independence and adaptation, its body helps communicate internal states and emotions to viewers. Anna Strasser emphasizes the importance of embodiment in her concept of social reciprocity, a defining feature of social interaction, referring to the exchange of social cues between agents. Embodied AI agents are well-suited to social communication because their digital or physical bodies generate social cues that can be identified and interpreted (Strasser 2017, p. 112). BOB’s digital body enables basic social communication, conveying social cues through facial and physical expressions. However, its alien features introduce limits on this communication, presenting the audience with a creature that seems alive but does not mimic human intelligence.

BOB’s AI architecture: the Congress of Demons and Inference Engine

BOB’s AI model forms its mind and provides the appearance of sentience. This makes BOB a free agent, allowing relationships distinct from the typical ones between viewers and artworks. BOB was created to consider how sentience is recognized. While it is not a genuinely sentient being, it displays recognizable aspects of it. Cheng identified the ability to recognize and react to upsets as a feature of sentience that BOB’s AI model would display. Responding to an upset requires some conception of reality to be present since it results from a mismatch between expectations and reality (Cheng 2020). A thermostat may react to stimuli but has no internal recognition or assumptions about changes in its environment. Beings with awareness can identify an incongruence and take action to address it. If that action does not achieve the desired result, it may lead to frustration. This process requires internal awareness; when beliefs are destabilized, presuppositions and inferences are updated to maintain a consistent worldview. Recognizing this behavior in another being creates the appearance of cognition, which supports the development of social relationships. Humans are already predisposed to personify or relate to things, even those with no indication of sentience (Złotowski et al. 2014, pp. 347–348). A being that appears to share awareness and sentience makes this anthropomorphizing process easier. BOB’s adaptability results from an AI model comprising competing desires and an adjustable worldview.

Two aspects comprise BOB’s AI model: the Congress of Demons, which was inspired by psychologist Carl Jung, and the Inference Engine, inspired by the AI researcher Richard Evans (Cheng 2020). Jung’s conception of the ego as a multitude of competing subpersonalities with different motives and beliefs informs the Congress of Demons. These “demons” represent different desires and behaviors. Only one can be in control at a time, so they compete for dominance (Cheng 2018). These include the Eater Demon, Fight Demon, Flee Demon, and Play Demon (Cheng 2020). Viewers can see which of these demons is currently dominant in a downloadable app called the BOB Shrine. This app facilitates interaction with BOB and will be discussed in more detail later. If a new object is added to BOB’s environment, the “Alertness Demon” will take control. If BOB learns that the object is food, the “Eater Demon” will become dominant and will remember that this object is edible. This memory leads the “Eater Demon” to come forth when the same object is seen in the future (Cheng 2020).

Jung viewed the development of sentience as the result of the brain becoming increasingly efficient at organizing competing desires (Cheng 2020). Cheng incorporated this concept into BOB’s AI. The organization of competing demons forms a “meta demon,” which organizes and assesses the assumptions and rules made by individual demons (Cheng 2020). BOB’s demons may compete, but they work together to inform BOB’s behavior, particularly when established rules are challenged, requiring reassessment of conclusions. Reassessing a conclusion is a complicated process that requires energy. Cognition, therefore, cannot be based on concrete presuppositions; fluidity is necessary. If they are overly rigid, an incorrect assumption can lead to a chain reaction destabilizing other beliefs (Evans 2020, pp. 191–192; Cheng 2020). BOB’s ability to reassess its beliefs contributes to its appearance of sentience.

The Inference Engine is the system by which BOB forms a consistent, rules-based worldview, and is described by Cheng as an interpretation of Richard Evans’ Differentiable Inductive Logic framework (Cheng 2020). This system constructs rules based on sensory data and previous experiences. If BOB becomes sick after eating a green apple, the inference is formed that green things should be avoided (Cheng 2020). When a green apple is presented to BOB in the future and the Alertness Demon takes control, it will reference the Inference Engine for available data on the object. Different demons weigh certain inferences more than others. The Eater Demon cares more if an object is editable than the Play Demon. The Inference Engine acts as a kind of memory where beliefs about specific objects and features of objects are stored for reference (Cheng 2020).

The Congress of Demons and the Inference Engine are not discrete systems; they interact to form BOB’s beliefs. Strong assumptions are formed when BOB’s expectations are not met. Sudden changes to which the demon is in control are remembered as upsets. These function as formative experiences and are given more weight in the Inference Engine (Cheng 2020). If a green apple appears and the Eater Demon knows it is food, it will take over, but if it unexpectedly makes BOB sick, the Flee or Fight Demon will quickly gain dominance. This event will cause a spike in emotion. BOB’s emotions are tracked on a negative to positive arousal scale. Events like the one described above rapidly shift these scales, which are remembered more clearly than minor shifts. This also applies to a positive experience; a green apple being more nutritious than previously assumed is an upset to an assumption and quickly shifts BOB’s level of arousal. These upsets in emotional state are marked as strong memories and inform BOB’s decisions in the future (Cheng 2020).

The Congress of Demons and the Inference Engine work to facilitate BOB’s behavior and mental growth. The congress explores a Jungian mind model that facilitates independent action. The Inference Engine organizes BOB’s assumptions into consistent beliefs. These features of the AI model create an embodied agent that mimics aspects of sentience.

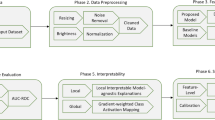

BOB Shrine app: affordances and social engagement

Interaction is primarily facilitated through the BOB Shrine app, which extends BOB’s body, allowing a view from BOB’s perspective, expression on its face, and some control over its movement (Cheng 2018). The app displays mental and physical state through several valences, including beliefs about objects like “isgood”, “isSafe”, and “isKin”, and physical needs like “energy,” “rest,” “bladder,” and “stomach”. The page showing BOB’s mental and physical state is presented in Fig. 2.

Metabolism and general physical needs are shown in the center left. Below are the charts that communicate BOB’s emotional and physical arousal levels. The middle area shows which part of BOB’s personality is currently dominant, and the right area shows BOB’s knowledge of a particular object (Cheng 2020). Cheng (2020) BOB (Bag of Beliefs) https://iancheng.com/bob.

While the app provides viewers control, some unpredictability remains in the work. Several offerings have ambiguous names, like “BlackOrb” and “LuckStone.” How BOB will react to objects is not always apparent, even those with more explicit meanings like “shrub”. The ambiguity attached to these objects removes some of the audience’s control over their interaction. This unpredictability is increased for the average viewer who enters the experience relatively blind. A brief introduction to the work will be provided by wall text or a gallery worker, but not all of the app’s details are fully explained. Viewers must experiment with different objects and learn with BOB, creating a cooperative relationship between the artwork and the audience. The app facilitates a process like the one described by Ahmedien, where viewers streamline their relationship with interactive work through a trial-and-error process of engagement (Ahmedien 2024, p.8). However, BOB’s agency interrupts this process, positioning the artwork not as a system to be explored but as an individual to be engaged with.

Viewers are granted some control over how BOB views and interacts with offerings. Objects can be assigned value based on two slides, one from orderly to chaotic and the other from lucky to cursed (Cheng 2020). This lets users tailor their experience, but there is still uncertainty in how BOB will interact with offerings. A BOB who has had positive experiences with fruit may try to eat the “SpikyFruit” object, which could cause harm. A less-trusting BOB may avoid the fruit. Viewers are limited in predicting how BOB will react because they are likely unaware of all the experiences of the current iteration. Someone may give an apple to BOB with benevolent intentions, but if a previous person used an apple to cause a negative experience, BOB might react with fear (Cheng 2020).

When giving an offering to BOB, there is an option to add a “parental caption” to provide further information about the purpose and nature of the object. This was included to mitigate BOB becoming too rigid in its assumptions. When testing, Cheng found that BOB would refuse to engage with specific colors because of negative early experiences with that color. The issue was not fixed even after increasing BOB’s propensity to revisit assumptions (Cheng 2020). Cheng’s solution was to let spectators add a “parental caption” that provides information as text when offering an object. These captions are remembered by “Angels” which parallel the Congress of Demons that take control when a caption is added to an object and remember the accuracy of the caption (Cheng 2020) If a particular iteration of BOB decides green things are poisonous, adding the caption “green is yum” to a green apple counters BOB’s total avoidance (Cheng 2020). This captioning system is shown in Fig. 3. BOB will be pleased if the captions accurately match the object’s qualities. If the captions are inaccurate, the relationship with BOB will deteriorate. The relationship with BOB is trackable on the app, shown as a “Reputation” score ranging from one to five. However, some of the captions are ambiguous, leading communication with BOB through this system to require effort and maintain some unpredictability (Davis 2019).

Users can create sentences with the provided words to give BOB more information about an object. In this case, the metal object is said to be dangerous with the phrase “metallic is kinda lethal” (Davis 2019). Davis (2019) Artist Ian Cheng Has Created an AI Creature Named “BOB.” Now, It’s Up to Viewers to Decide His Fate https://news.artnet.com/art-world/ian-cheng-bob-gladstone-1488823. Accessed 18 July 2023.

The caption system provides the viewer with basic linguistic communication, allowing some control over how BOB will act. While BOB cannot respond verbally, the results of messages are seen through its behavior and mood (Cheng 2018). The term “parental” communicates the artist’s intention by encouraging certain assumptions about relationships with BOB and how its artificial mind functions. BOB is designed to encourage a sense of responsibility and social engagement. This, combined with the animal-like qualities of BOB, mimics aspects of how humans relate to pets (Cheng 2020). Viewers could give BOB false information or be cruel to him, but the captioning system primes them to be benevolent with their interactions.

The BOB Shrine app can be understood through affordances, which are features of an object that suggest certain behaviors. Positive affordances indicate opportunities, like a teacup’s handle suggesting how it should be picked up. Interactive artworks tend to have explicit affordances indicating how viewers should engage with the work (Boden 2007, p. 218). The BOB Shrine App’s user interface suggests social interaction and uses imagery associated with video chatting software, showing BOB’s changing facial expressions. This streamlines BOB’s ability to provide social cues that aid communication (Strasser 2017, p. 112). The interface adopts the imagery of software built for video chatting, guiding the kinds of social relationships viewers can form with BOB

These BOB Shrine App design choices and BOB’s appearance of sentience encourage social rather than tool interaction. These features contrast with the text box of a neural network image generator, which appears as a digital tool (Strasser 2017, p. 106). The affordances provided by Cheng present BOB as an independent agent and facilitate relationship building.

Emergent themes in interactive AI art

BOB (Bag of Beliefs) presents an embodied agent capable of engaging with its environment. Its ILP AI system creates a being with a recognizable logic structure and the appearance of sentience. Interaction is facilitated through an app that provides affordances that encourage social interaction. These elements foster dynamic, co-creative themes to emerge from engagement. While this work provides space to explore the relationship between humans and technology, its role as an embodied, independent AI system facilitates a broad range of emergent themes. Three will be discussed. The first explores how human and nonhuman intelligence might interact and form relationships. The second is the way sentience and models of the mind are understood. The third is expanding how interaction with art can operate through presenting an independent, unpredictable being as an artwork.

The relationship between AI and humans is a theme in BOB (Bag of Beliefs), but Ian Cheng has indicated that he was particularly concerned with broader themes of relationships. He comments on this in an interview for his 2018 solo exhibition of BOB.

“I figured by trying to make an artwork that can change, and hopefully change on its own, that you would have a relationship to it, the way that you have to a pet or a cousin or any other living creature” (Cheng 2018).

Cheng’s reference to animal and familial relationships suggests his concern with relationships and social connection. Interaction with BOB examines how humans engage with non-human minds, including AI and animal intelligence. This is achieved through BOB’s AI system, which uses recognizable logical structures, and its digital embodiment that recalls biological life. The Congress of Demons that guides BOB’s behavior and the Inference Engine that structures its beliefs allow viewers to see the logic behind its behavior and emotions. Understanding BOB’s mind helps viewers engage with it as an individual entity with agency. However, BOB is not only presented as an AI system but also as a hybrid combining AI and a digital body with biological aspects. This encourages the perception that BOB is more than a technological system. The animal elements of the design are present in an early concept sketch shown in Fig. 4. Interacting with BOB does not feel like engaging with a technological interface; it is more like encountering animal intelligence. BOB’s digital embodiment also contributes to social interaction, allowing viewers to recognize physical and emotional cues through facial and physical reactions (Strasser 2017, p. 112). BOB’s internal AI construction generates the appearance of thought, and external design references biological systems, exploring how different intelligences might interact through social engagement.

The sketch shows BOB’s fractal, branching body structure and features a distinctly cat-like face, an aspect that remains in the final version of the work but is more emphasized here (Cheng 2020). Cheng (2020) BOB (Bag of Beliefs) https://iancheng.com/bob.

Cheng’s use of AI explores different models of mind, cognition, and sentience, particularly through BOB’s structured beliefs and competing desires. An adjacent theme emerges through the influence of animal intelligence on BOB’s inner life, which opens a conceptual space investigating non-anthropocentric models of mind (Cheng 2020). There is often a preoccupation with AI seeming human, hence the popularity of the Turing Test, designed to assess the ability of an AI to copy humans in its interactions. This interest encourages anthropocentric mimicry, but if any truly sentient AI is developed, it may not think like humans. Using animal sentience as a basis explores how AI is distinct from human minds. Like BOB, animal intelligence and behavior differ from our own, but relationships and interaction are still possible. Communication is limited with animals, but we can assume that offering food is likely to generate a positive response, and making a sudden movement will result in a negative one. While a relationship can be formed, the differences in cognition are a gap that must be bridged. BOB operates similarly; viewers can take actions that will change how BOB interacts with them. However, they cannot account for all factors that have influenced BOB’s behavior, nor can they communicate with it the same way they would with another person. Engaging with BOB’s apparent sentience reflects on different models of the mind and sentience, particularly in how AI is constructed and understood.

A third relevant theme is exploring the potential for AI as a medium for interactive art through its expansion of the function of galleries. BOB’s independence makes it act unpredictably, contributing to Cheng’s goal of creating a work that misbehaves and breaks the typical gallery rules (Cheng 2018). The limited control viewers have over BOB also disrupts expectations of how interactive art is generally engaged with. Like traditional interactive art, the artist sets the stage, and the viewer participates. However, AI increases unpredictability and introduces agency into the artwork (Castellanos 2022, p. 165). Imbuing the artwork with the ability to take independent action allows it to disrupt the typical subject-object relationships expected in the gallery. It creates a social relationship between the object and the viewer. This provides a space for examining how the relationship between artwork, artist, and audience can evolve and suggests a possible role of art to facilitate participant observation scenarios where theories of cognition and sentience can be explored (Castellanos 2022, p. 165).

These three themes emerge from the dynamic relationships generated through social interaction. BOB’s logical behavior, biological imagery, and emotional cues encourage viewers to relate to BOB as a living entity, generating themes of how human and non-human intelligences interact. The exploration of mind models emerges from BOB’s apparent sentience, raising questions about how the line between the appearance of thought and its existence is drawn. Finally, BOB’s unpredictability examines how interactive art functions in a gallery through an evolving and independent artwork. BOB’s AI architecture facilitates these three themes. BOB’s independence and recognizable mind create the dynamic social interactions that support these explorations.

Conclusion: the implications of BOB (Bag of Beliefs) as Interactive Art

BOB (Bag of Beliefs) fits within the two conditions of interactive art outlined at the start of this paper: (1) Interaction is a required element for the work and is part of the medium, and (2) Interaction affects the meaning of the work. It fits condition one because interactivity is part of the medium and is required to complete the work. Without interaction, BOB’s mental and physical growth would be limited. If BOB is kept healthy through food offerings, it will grow; if BOB is malnourished, branches of its body will fall off, and its growth potential will not be met. BOB learns from experiences that participants provide through their offerings. Like with social animals, a lack of social engagement will stunt BOB’s mental development. Interaction is set up to create a feedback loop where BOB relies on viewers to grow, and viewers can only learn about BOB through interacting with it. Since BOB’s AI creates a creature that can respond to stimuli, spectator exploration of BOB’s personality changes its behavior and relationships with BOB. This dynamic interaction is part of the work and functions through audience participation. Condition two is met since the meaning of BOB, Bag of Beliefs, is communicated and generated through interaction. The themes presented in BOB, like different models of the mind (Cheng 2020), human-technology relationships, and unpredictability within a gallery setting (Cheng 2018), are understood through engaging with BOB.

While BOB meets these two conditions, the work also expands the types of communication and engagement possible in interactive art. The formation of dynamic relationships represents a new type of interaction that contrasts with the relatively one-sided engagement typically seen in the art form. It builds upon the increased reactivity digital technology has contributed to interactive art by enabling independent artworks that can grow and change. When combined with the existing quality of interactive art changing based on the viewer’s actions, the capacity of AI systems to mimic sentience and cognition opens the way for more socially reciprocal relationships between interactive artworks and audiences.

An expansion of an art form creates space for new themes and explorations to be generated. The interactive, changing relationships viewers can create with BOB open new engagement possibilities between art objects and audiences. This expansion has value outside debates in art and provides fertile ground for exploring how we relate to advancing technology. Fostering a relationship between human and non-human digital minds represents a novel approach to artmaking and explores the nature of AI-human relations. As AI improves, discussions of how new forms of intelligence can be interacted with are inevitable. Interactive, digital AI artworks like BOB (Bag of Beliefs) provide insights into potential scientific and cultural shifts relating to non-organic intelligence (Castellanos 2022, p. 165). BOB may not be genuinely sentient, but it does not behave like a passive and lifeless thing; it has a recognizable inner life. The use of AI provides BOB with enough of the features of sentience for those engaging with the work to form a relationship with it as an independent entity.

As AI technology advances, new art forms that lead to novel explorations of how art and technology are understood will likely be developed. However, understanding how these technologies are incorporated into existing art forms provides insight into cognition, sentence, and AI. BOB (Bag of Beliefs) demonstrates how AI is uniquely suited to generate new relationships in interactive and participatory art that explore how we relate to art and developing technology.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Ahmedien DAM (2024) A drop of light: an interactive new media art investigation of human-technology symbiosis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11(721):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03206-y

Ascott R (1964) The construction of change. Camb Opin Mod Art Br 41:37–42

Boden M (2007) Creativity and conceptual art. In: Goldie P, Schellekens E (eds) Philosophy & conceptual art. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 216–237

Castellanos C (2022) Intersections of living and machine agencies: possibilities for creative AI. In: Vear C, Poltronieri F (eds) The language of creative AI practices, aesthetics and structures. Springer, Cham, pp 155–166. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-10960-7

Cheng I (2018) BOB, Emissaries Serpentine Galleries. Serpentine Galleries. http://www.serpentinegalleries.org/whats-on/ian-cheng-bob/

Cheng I (2020) Minimum viable sentience what I learned from upsetting BOB. http://iancheng.com/minimumviablesentience

Chung S (2022) Sketching symbiosis: towards the development of relational systems. In: Vear C, Poltronieri F (eds) The language of creative AI practices, aesthetics and structures. Springer, Cham, pp 155–166. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-10960

Davis B (2019) Artist Ian Cheng has created an AI creature named ‘BOB.’ Now, it’s up to viewers to decide his fate. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/ian-cheng-bob-gladstone-1488823

Evans R, Grefenstette E (2018) Learning explanatory rules from noisy data (extended abstract). In: Proceedings of the twenty-seventh international joint conference on artificial intelligence, International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, pp 5598–5602. https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2018/792

Evans R (2020) Kant’s cognitive architecture. Dissertation, Imperial College, London. https://www.doc.ic.ac.uk/~re14/Evans-R-2020-PhD-Thesis.pdf

Flick W (2022) The ethics of creative AI. In: Vear C, Poltronieri F (eds) The language of creative AI practices, aesthetics and structures. Springer, Cham, pp 155–166. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-10960-7

Hlávková Z (2021) Opera as hypermedium: meaning-making, immediacy, and the politics of perception, 1st edn, vol 1. Oxford University Press, New York

Irvin S (2022) Immaterial: rules in contemporary art. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kluszczynski R (2010) Strategies of interactive art. J Aesthet Cult 2:1–27. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269984433_Strategies_of_interactive_art

Lopes D (2009) A philosophy of computer art. Taylor & Francis Group, Abingdon https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/peking/detail.action?docID=446874

Lopes D (2007) Conceptual art is not what it seems. In: Goldie P, Schellekens E (eds) Philosophy & conceptual art. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 238–255

Manovich L (2001) The language of new media. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Mateas M (2001) AI hybrid art and science practice. Leonardo 34(2):147–153. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1577018

Nguyen CT (2020) The arts of action (philosophers’. Imprint) 20(14):1–27. http://www.philosophersimprint.org/020014/

Poltronieri F (2022) Towards a symbiotic future: art and creative AI. In: Vear C, Poltronieri F (eds) The language of creative AI practices, aesthetics and structures. Springer, Cham, pp 155–166. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-10960-7

Santos I, Castro L, Rodriguez-Fernandez N et al. (2021) Artificial neural networks and deep learning in the visual arts: a review. Neural Comput Appl 33:121–157. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00521-020-05565-4

Sporns O, Pegor T (2021) Information-theoretical aspects of embodied artificial intelligence. In: Iida F, Pfeifer R, Steels L, Kuniyoshi Y (eds) Embodied artificial intelligence. Springer, Berlin, pp 74–85

Strasser A (2017) Social cognition and artificial agents. In: Müller V (ed) Philosophy and theory of artificial intelligence. Springer, Cham, pp 106–135

Wang Y (2024) Personal interview with artist. 28, February

Wong KJCO, Joonsung Y(2009) Interactive art: the art that communicates Leonardo 41(2):180–181. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20532638

Xiaobo L, Yuelin L (2014) Embodiment, interaction and experience: aesthetic trends in interactive media arts. Leonardo 47(2):166–169. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43834153

Zhang B, Zhu J, Su H(2021) Toward the third generation artificial intelligence Sci China Inf Sci 66(2):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11432-021-3449-x

Złotowski J, Proudfoot D, Yogeeswaran K et al. (2014) Anthropomorphism: opportunities and challenges in human-robot interaction. Int J Soc Robot 7:347–360. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12369-014-0267-6

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJS conducted research, wrote the main manuscript, and provided analysis. MJ assisted with the research, analysis, and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study. The research is a theoretical and philosophical investigation based on published sources and publicly available artworks; it did not involve human participants, human data, or animals.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required for this study as it did not involve human participants or the collection of any personal data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sklar, S.J., Jiang, M. Art with agency: artificial intelligence as an interactive medium. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1546 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05863-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05863-z