Abstract

This study examines the relationship between corruption and economic resilience in Saudi Arabia, focusing on how the country maintains economic resilience despite persistent issues such as bribery, embezzlement, and abuse of power. Employing both quantitative and qualitative analysis, and drawing from official government data covering the period 2016–2022, the study identifies critical drivers of resilience—including oil wealth, targeted public investment, economic diversification strategies, and proactive anti-corruption initiatives. While corruption predictably undermines economic performance by distorting markets, weakening institutions, and increasing inefficiencies, Saudi Arabia’s case demonstrates that strategic legal reforms and empowered oversight bodies can mitigate these effects. The findings underscore the importance of continuous institutional development, transparent regulatory frameworks, and effective law enforcement in safeguarding growth. The study contributes to ongoing scholarly debates on corruption and the resource curse by offering a case-based analysis of how strong governance mechanisms can protect resource-rich economies. It also calls for further research on sectoral vulnerabilities and improved corruption measurement methodologies to inform anti-corruption strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has increased its anti-corruption efforts significantly. The Oversight and Anti-Corruption Authority (Nazaha) has reported hundreds of arrests and investigations each month, targeting government officials from various agencies. These high-profile campaigns indicate a growing institutional commitment to transparency and accountability, even as corruption continues to pose a challenge worldwide (Nazaha, 2023). Studies have shown that corruption can have a detrimental impact on the economy and overall development (Song et al., 2021). Across different political and economic systems, corruption crimes—such as bribery, embezzlement, and abuse of power—have been linked to inefficiency, increased business costs, and reduced investor confidence (Magakwe, 2024). For instance, the United Nations and the World Economic Forum estimate that corruption costs approximately 5% of global GDP. Additionally, Transparency International estimates that the cost of corruption in developing countries is around $1.26 trillion annually.

This focus responds to a noticeable gap in the literature, where much of the scholarship on corruption and economic growth tends to concentrate on Western or transitional economies, often overlooking the dynamics in rentier states with centralized governance structures. This is notably acute in rentier states that heavily depend on natural resource revenues, which encounter specific challenges: while resource wealth can mitigate economic shocks, it also fosters rent-seeking behaviors that undermine governance and create opportunities for corrupt practices (Haque and Tausif, 2025). In the case of Saudi Arabia, corruption presents a potential challenge to economic growth and stability. However, despite these concerns, the Saudi economy has exhibited significant resilience, maintaining steady growth and development over recent decades.

This study explores the paradoxical relationship between corruption and economic resilience in Saudi Arabia by investigating the mechanisms that mitigate the adverse effects of corruption. It examines the role of institutional frameworks, government intervention, and legal reforms in countering corruption’s economic consequences, particularly in the context of Vision 2030, a national blueprint aimed at promoting transparency, accountability, and diversification beyond oil dependency (Vision 2030, 2016). Additionally, the study contributes to broader discussions on the “resource curse” by assessing how Saudi Arabia has leveraged its natural resources while avoiding many of the pitfalls associated with resource dependence.

For the purposes of this study, economic resilience refers to a country’s ability to foster continuous economic growth while effectively navigating and withstanding financial shocks (Mulenga, 2024). It reflects the capacity to maintain stability in the face of significant systemic challenges, such as corruption and various financial crimes. This resilience includes vital elements such as fostering and preserving investor confidence, ensuring that public services are delivered effectively to citizens, and safeguarding long-term developmental objectives, even when confronted with governance-related risks.

Understanding the factors that contribute to this resilience is crucial for both academic inquiry and policy formulation. While much of the literature emphasizes the detrimental effects of corruption on economies, which are well-documented, less attention has been given to how certain economies manage to sustain stability and maintain institutional performance despite corruption-related challenges. Saudi Arabia presents a unique case study in this regard, as it has successfully pursued economic diversification and large-scale reforms while simultaneously implementing anti-corruption initiatives.

This paper fills a gap in the existing literature by presenting a detailed mixed-methods analysis of Saudi Arabia’s experience from 2016 to 2022. It evaluates the country’s anti-corruption policies, oversight institutions, and economic outcomes to determine whether the legal and institutional reforms have contributed to economic resilience. In doing so, it contributes a case study to the global discussion on corruption, governance, and sustainable development.

This study seeks to answer the following research question

How has Saudi Arabia managed to sustain economic resilience in the face of persistent corruption-related risks?

The central hypothesis is that a combination of institutional reforms, strengthened oversight mechanisms, and strategic planning under Vision 2030 has helped mitigate the economic consequences of corruption and supported sustained growth.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows:

Section “Literature Review” reviews the existing literature on corruption, economic resilience, rentier states, and the resource curse.

Section “Methodology” outlines the study’s methodology, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Section “Analysis” analyzes corruption in Saudi Arabia, focusing on the role of institutional reforms, legal enforcement mechanisms, and strategic planning under Vision 2030 in mitigating corruption’s economic effects.

Section “Discussion” presents and discusses the main findings of the study, analyzing how institutional reforms and anti-corruption measures have influenced economic resilience in Saudi Arabia.

Section “Results and Recommendations” summarizes key results, offers policy recommendations, and outlines potential areas for future research.

Section “Limitation” addresses the study’s limitations.

Section “Conclusion” concludes with a summary of the main contributions and implications of the research.

Literature review

Corruption crimes, including bribery, embezzlement, and abuse of power, have been widely studied in economic literature due to their significant impact on growth and development. Scholars such as Ahmad and Tanzi (2002), Mauro (1995, 1996), Mugellini et al (2021), Spyromitros and Panagiotidis (2022), Tanzi (1998) and Wei (2002) argue that corruption serves as a significant barrier to economic growth and development. It increases transaction costs, making financial dealings more complex and reducing overall efficiency. Furthermore, corruption distorts market competition by favoring specific businesses over others, which undermines a fair and level playing field. This environment of unfairness also discourages foreign investment, as investors are hesitant to navigate a landscape filled with corruption and uncertainty. Similarly, Rose-Ackerman (2007) emphasizes that corruption undermines institutional frameworks, diminishes public trust, and leads to the inefficient allocation of resources, which in turn poses a considerable hurdle to the economy.

Some economists, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, proposed the controversial “grease the wheels” hypothesis. They argued that in rigid bureaucracies, corrupt practices, such as bribery, could enhance efficiency by allowing processes to bypass bureaucratic red tape that often slows down processes and hinders progress (Huntington, 1968; Leff, 1964). Recent studies, such as those by Dreher and Gassebner (2013), have supported this perspective. However, other studies have challenged this view, suggesting that any short-term benefits of corruption are ultimately outweighed by the long-term decline of institutions (Méon and Sekkat, 2005).

Recent studies continue to explore the complex relationship between corruption and economic performance. A 2023 study found that corruption in Saudi Arabia increases costs, misallocates resources, and weakens institutional integrity, ultimately hindering economic growth (Altorkostani, 2023). Similarly, a 2024 study on Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey revealed that corruption significantly hinders economic development by distorting market mechanisms and deterring foreign investment (Susilo, 2024). These findings reinforce long-standing concerns that corruption undermines economic efficiency and institutional stability.

The paradox of economic resilience in resource-rich, corruption-prone countries has been a major research topic. Saudi Arabia, like many other oil-rich economies, has managed to sustain economic growth despite persistent corruption. According to Karl (1997), resource wealth can act as a buffer against the adverse effects of corruption by ensuring a steady flow of revenue, which mitigates fiscal instability. However, Ali and Bhuiyan (2022); Amundsen (2017); Ross (2012) argue that heavy dependence on natural resources can lead to the “resource curse,” where corruption thrives due to rent-seeking behaviors and weak institutional controls. While Saudi Arabia has maintained growth, its efforts to diversify the economy and strengthen governance frameworks under Vision 2030 indicate an awareness of the long-term risks associated with resource dependence.

Recent studies have thoroughly examined how legal frameworks and institutional mechanisms can effectively reduce the negative effects of corruption on society (Heywood, 2018). Transparency International (2021) reports that countries with robust legal frameworks, independent judiciaries, and strong enforcement of anti-corruption laws tend to mitigate corruption’s adverse effects on economic growth. Saudi Arabia has implemented extensive anti-corruption initiatives through institutions such as the National Anti-Corruption Commission (Nazaha). In addition to the establishment of Nazaha in 2011, Saudi Arabia enacted the Nazaha Law in 2024, which mandates the immediate dismissal of any government employee found guilty of corruption. This law reflects the country’s commitment to enhancing government integrity, promoting ethical behavior, and building public trust. Comparatively, nations like Singapore and the Nordic countries have successfully implemented stringent anti-corruption policies, demonstrating that a combination of legal measures and cultural shifts can significantly curb corruption’s impact (Johansson, 2023; Johnston, 2005; Rothstein, 2011).

Accurately measuring corruption remains challenging due to its covert nature. Indices like Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index and the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators are commonly used, but they rely heavily on perceptions, which can be subjective. Hence, recent studies highlight the necessity for more objective, data-driven methods, such as forensic financial analysis and case studies, to better understand the actual impact of corruption on economic performance (Ellili et al., 2024; Lyra et al., 2022; Williams and Beare, 1999). As Saudi Arabia continues to refine its anti-corruption measures, integrating more empirical methodologies could enhance transparency and accountability.

Under Vision 2030, Saudi Arabia aims to reduce its dependence on oil by diversifying its economy and strengthening governance frameworks. The government’s anti-corruption initiatives are integral to creating a more transparent and attractive investment climate. In 2023, Saudi Arabia attracted foreign direct investment inflows totaling 96 billion riyals ($25.6 billion), surpassing its official target under the National Investment Strategy (Ministry of Investment, 2024). The success in exceeding FDI targets suggests that anti-corruption efforts have positively influenced investor confidence by fostering a stable and predictable economic environment (IMF, 2024).

Methodology

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to examine the complex and multifaceted relationship between corruption and economic growth in Saudi Arabia. The research integrated both quantitative data analysis and qualitative insights to provide a comprehensive understanding of the issue.

Data sources and quantitative analysis

For the quantitative component, data were collected from both domestic and international sources. Domestic sources include official statistics from the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Economy and Planning, and Nazaha (the Saudi Oversight and Anti-Corruption Authority). International datasets were obtained from international organizations such as the World Bank, OPEC, and Transparency International.

The corruption statistics used in this study specifically refer to reported cases—that is, allegations and complaints formally registered with Nazaha. These figures reflect the volume of corruption-related incidents brought to the attention of authorities but do not necessarily indicate cases that were investigated, prosecuted, or adjudicated. Due to the lack of publicly available disaggregated data, it was not possible to assess the progression of these cases through the legal system. This limitation is acknowledged, and the study emphasizes that the data reflect the scope of reported corruption, not enforcement outcomes.

Qualitative analysis

The qualitative component consisted of an extensive literature review aimed at identifying relevant theoretical frameworks and empirical studies on corruption and economic development. This review informed the interpretation of the quantitative findings and allowed for a more nuanced understanding of how corruption affects economic resilience, particularly in resource-rich countries such as Saudi Arabia.

Analytical framework

By integrating empirical data with contextual analysis, the study seeks to uncover the underlying mechanisms that mitigate the negative economic impacts of corruption and to identify the legal, institutional, and policy factors contributing to Saudi Arabia’s economic resilience.

Analysis

The prevalence of corruption in Saudi Arabia

The World Bank recognizes corruption as “the single greatest obstacle to economic and social development.” (World Bank, 2020) Corruption is a widespread hurdle that exists in many nations under various labels and shapes. Corruption vitally undermines economic growth, development, and good governance. Numerous academics make an effort to characterize corruption precisely, but they maintain that the definition of corruption must encompass additional elements (Pozsgai-Alvarez, 2020). The only way to directly assess or evaluate corruption is through the use of other economic and social variables. (Bussell, 2015) Nevertheless, corruption can be defined as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain. A multitude of activities, such as bribery, embezzlement, misuse of public funds, improper use of official authority, illicit enrichment, and money laundering, are examples of potentially corrupt practices (Dreher and Schneider, 2010).

Corruption presents a significant and entrenched challenge in Saudi Arabia, with detrimental effects on various aspects of public and private life (Al-Shammari and Abu Bakr, 2013). For decades, Saudi Arabia has suffered from the spread of phenomena such as bribery, embezzlement, favoritism, and abuse of power, which have eroded trust in government institutions and affected the quality of public services. In 2023, Nazaha reported that bribery crimes made up approximately 58 percent of all corruption cases, totaling around 47,000 incidents. The second most common form of corruption was the exploitation of official influence, which accounted for 21% of cases. Contract exploitation represented 4%, while embezzlement of public funds constituted about 3% of the cases (Nazaha, 2023).

Additionally, in its latest report issued in May 2025, Nazaha revealed that it conducted approximately 2775 inspections of various government agencies. They investigated 435 suspects, including employees from the Ministries of Interior, Defense, Municipalities and Housing, Human Resources and Social Development, Transport and Logistics Services, and Health, for their involvement in bribery and exploitation of official influence. As a result, 120 individuals were arrested in accordance with the Code of Criminal Procedure (Nazaha, 2025).

The detrimental effects of corruption on Saudi Arabia are multiple, as it leads to the waste of huge financial resources that could have been invested in development and infrastructure projects (Nazaha, 2022). It is anticipated that the public treasury has experienced costs of up to 15% during the last few decades. According to official reports released by the Anti-Corruption Commission (Nazaha), tens of thousands of incidents of corruption are identified each year in collaboration with other government authorities. These cases cost the public Treasury tens or hundreds of billions of dollars each year (Alatawi, 2023). They also undercut the idea of equality and create socioeconomic gaps, perpetuating a culture of favoritism and nepotism (Nazaha, 2015). This has also damaged the quality of government programs, services, jobs, and other connected matters. Internationally, corruption undermines Saudi Arabia’s reputation and lowers its foreign investment appeal.

In 2023, there were several cases of corruption involving municipal employees. In one instance, an employee in the Lands and Real Estate Department of a city’s municipality was implicated in illegally transferring ownership of several residential and commercial plots valued at over 10 million riyals in exchange for a bribe (Nazaha, 2023). In another case, a group of citizens collaborated with an employee from the Ministry of Justice, who misused his position to attempt to illegally transfer ownership of land worth 12.5 million riyals. Additionally, a municipal employee in a certain region unlawfully awarded projects worth 11 million riyals to a commercial establishment that he actually owned.

In 2024, the CEO of the Royal Commission for AlUla Governorate was suspended due to his involvement in corruption alongside others. He was accused of abusing his influence and laundering money for national talent companies in which he held a stake. The charges against him totaled 206 million riyals. Another notable case involved the head of a notary public at the Ministry of Justice, who illegally seized large tracts of state-owned land during his tenure. He sold this land for 148 million riyals. Additionally, a municipal employee was implicated in a scheme where he received 63 million riyals in exchange for issuing approximately 300 supply orders irregularly to private commercial companies. The total value of these approved orders amounted to around 171 million riyals. These incidents caused significant delays in various development, improvement, and construction projects. Several government tenders and initiatives, which could have benefited many citizens across Saudi Arabia, stalled and were not resumed until many years later (Nazaha, 2024).

The Saudi leadership has realized the seriousness of this problem and has taken many measures to combat it, such as tightening laws and regulations, establishing specialized oversight bodies, and enhancing transparency in government procedures (SPA Saudi Press Agency, 2014). Wide-ranging awareness campaigns have also been launched to change behaviors and encourage citizens to report cases of corruption.

Corruption has a significant negative impact on the political, economic, and social growth of any country. It could impede all efforts to bring about change and progress (Spyromitros and Panagiotidis, 2022). Furthermore, it is the most common reason for slowing down action in many developing countries. Like other countries, Saudi Arabia has been dealing with corruption for decades, which has affected the public sector and various government agencies.

The literature and official data from Saudi Arabia both demonstrate that corruption has detrimental effects on the government (Nazaha, 2020). It leads to higher government expenditures, stunts economic growth, and undermines the quality of government initiatives, services, and employment (Al-Ghannam, 2011). In certain government projects, costs have escalated substantially due to corrupt practices like bribery and favoritism. This has resulted in a decline in the quality of public services, particularly in crucial sectors like education and health. The funds that were meant to be allocated to these sectors have been siphoned off into the hands of corrupt individuals, severely impacting the well-being of the public and compromising the effectiveness of vital services (Nazaha, 2021).

For instance, in 2024, the CEO of the Royal Commission for AlUla Governorate was suspended due to his involvement in corruption alongside others. He was accused of abusing his influence and laundering money for national talent companies in which he held a stake. The charges against him totaled 206 million riyals. Another notable case involved the head of a notary public at the Ministry of Justice, who illegally seized large tracts of state-owned land during his tenure. He sold this land for 148 million riyals. Additionally, a municipal employee was implicated in a scheme where he received 63 million riyals in exchange for issuing approximately 300 supply orders irregularly to private commercial companies. The total value of these approved orders amounted to around 171 million riyals. These incidents caused significant delays in various development, improvement, and construction projects. Several government tenders and initiatives, which could have benefited many citizens across Saudi Arabia, stalled and were not resumed until many years later (Nazaha, 2024).

In the January 2024 monthly report, Nazaha revealed that it has identified instances of corruption totaling more than 619,700,000 SR (165,234,908 USD) (Nazaha, 2024). These cases encompassed a range of misconduct, including the fraudulent awarding of government contracts, unauthorized allocation of projects to personal contacts, misappropriation of public funds allocated for public initiatives, and illicit granting of supply permits to private firms. This is just a small sampling from a single monthly report that highlights the extent to which corruption can hinder government initiatives, misappropriate public funds, and create significant obstacles to development, ultimately undermining the performance of public institutions.

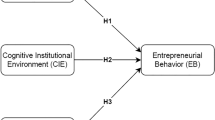

The following (Fig. 1) presents the data on corruption cases reported by the Saudi official government agency (Nazaha) from 2016 to 2022, along with the corresponding Saudi score based on the Transparency International index (Fig. 2). The Saudi score ranged from 46 to 53 out of 100 during this period, indicating an average ranking according to the Transparency International Perception Index (Transparency International, 2024). The data also indicates that despite the rise in reported corruption cases and concerns within Saudi Arabia as per government reports, Transparency International’s score suggests that the country’s overall performance has not experienced a significant change. This discrepancy may be attributed to differing definitions, scopes, and perceptions of corruption between Saudi Arabia and the international community. While the global perception of Saudi Arabia has remained relatively stable, this may be due to a lag in how international evaluations reflect domestic legal and institutional reforms. Consequently, these evaluations can sometimes be inaccurate or fail to fully represent the current reality.

Furthermore, as we will discuss later, the increase in corruption cases may not have significantly affected the national economy. This is supported by the ongoing growth in various sectors, the rise in non-oil revenues, the increase in foreign direct investment, and the stability of credit ratings during the same period. These factors suggest a level of institutional resilience despite the persistent challenges in governance.

The role of oil revenues

Saudi Arabia’s dependence on oil as a primary source of income

The Saudi economy is so indistinguishably linked to the pivotal role of oil that it is impossible to discuss the economy without considering its impact. Since its discovery in the 1930s, “black gold” has been the backbone of the Saudi economy and a major source of its wealth. It is the cornerstone of economic renaissance, financial stability, and strengthening Saudi Arabia’s international position (Ansari, 2017). For decades, Saudi Arabia has relied mainly on oil and energy revenues, which allowed it to achieve significant economic growth and finance huge projects, whether in infrastructure works such as roads, airports, and other constructions, as well as in the health and education sectors and other fields, which is one of the main reasons for the renaissance of Saudi Arabia and placing it among the ranks of countries. Accordingly, it is considered the main pillar of the national economy to provide government resources from jobs and a primary income for the state and citizens alike (Ramady, 2010). Over the past few years, it has become evident that oil plays a vital role as the primary source of income for the Saudi general budget (Ministry of Finance, 2024a). This reliance on oil is reflected in the fact that it contributes roughly between 60 and 75% of the state’s annual revenues. Please refer to Fig. 3 and Fig. 4.

The Impact of oil price fluctuations on the economy and corruption risks

The impact of fluctuations in oil prices on the economy can be extremely significant, especially considering that oil revenues make up the majority of Saudi Arabia’s income. As a result, the oil sector is heavily influenced by global events, both in times of increase and decrease in oil prices. Therefore, the dramatic decline in oil prices, which dropped to around $28 in 2016 and around $12 in 2020, resulted in a budget deficit of billions of dollars (OPEC: OPEC Basket Price, 2023). The fluctuations in oil prices can have significant impacts on various economic factors, including economic growth, employment rates, GDP per capita growth, and other key economic metrics (Wang et al., 2022). Consequently, these fluctuations in global oil prices, particularly over the last decade, indicate that these revenues cannot be considered a dependable source of income in the future. See Fig. 5.

Periods of high oil revenue can create environments where spending is uncontrolled and financial oversight is weak. When funds are abundant, there is less pressure to ensure transparent and fair allocation. In these situations, large-scale infrastructure projects, procurement contracts, and discretionary spending are often at risk of corruption, including bribery, kickbacks, favoritism, and embezzlement. The lack of strong oversight mechanisms during times of economic boom commonly results in the misappropriation of public funds and the strengthening of patronage networks (Akinsola, 2025).

When oil prices decline, financial pressures can increase corruption as government officials and institutions attempt to exploit scarce resources (Alaye and Ogunbanwo, 2024). Budget deficits may lead to illicit activities, such as misappropriating emergency funds, manipulating procurement processes, or diverting public assets to address personal or institutional failures. As a result, the pervasive economic uncertainty that comes with such downturns often erodes the integrity of institutions, making them more vulnerable to corrupt practices and undermining public trust.

Government strategies to diversify the economy and reduce reliance on oil

The Saudi government has recognized the magnitude of these challenges related to the oil sector and the global economic fluctuations that have significantly affected this vital sector. One of the main strategies of Saudi Vision 2030 was to diversify the economy and reduce dependence on oil alone as the primary source of income (Vision 2030, 2016).

Since the arrival of Prince Mohammed bin Salman as the Crown Prince, he has realized the necessity of this economic transformation and the necessity of economic reforms by establishing the Council of Economic and Development Affairs in 2016, which aims to put in place the necessary mechanisms to implement the comprehensive economic reform plan that aims to create other economic sectors as sources of income, such as the tourism, sports, and industry sectors, by establishing many related development projects (Grand and Wolff, 2020).

Despite the remaining challenges, there is a positive sign in Saudi Arabia’s non-oil revenue growth (Waheed et al., 2020). According to the Saudi Ministry of Finance, Non-oil revenues grew by 27% in the second quarter compared to the first quarter of 2024, reaching approximately 141 billion Saudi riyals (Ministry of Finance, 2024a). This suggests a promising trend towards economic diversification. This also demonstrates the extent to which oil and non-oil revenues have increased, thereby contributing to the reduction of the budget deficit.

In recent years, Saudi Arabia has experienced an economic transformation following the launch of Vision 2030. This initiative aims to diversify the economy and reduce reliance on oil as the sole source of national income. According to government sources, including the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Planning and Economy, as well as international data from the International Monetary Fund, there has been significant growth in non-oil sectors such as sports, tourism, renewable energy, agriculture, and logistics (Saudi Vision 2030, 2023).

One notable development is the establishment of the Royal Commission for AlUla, which promotes an archaeological and tourist destination that attracts visitors from around the globe. Additionally, the Riyadh Season, initiated in 2019, serves as a vibrant tourist attraction for both residents and tourists from abroad. This event has evolved into a global brand, partnering with various companies and sports clubs worldwide, including Spain’s La Liga and Italy’s AS Roma, along with other major sporting events.

In 2020, the Saudi Tourism Authority was restructured into the Ministry of Tourism to align with Vision 2030, which aims to attract over 150 million tourists by 2030. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia is undertaking numerous vital projects, such as NEOM, Trojena, LINE, and Oxagon, which are designed to establish the country as a hub for biotechnology, robotics, and AI-driven industries (Vision 2030, 2016).

Government support and economic policies

Government initiatives to promote economic growth and its anti-corruption dimensions

Saudi Arabia has undergone many economic, social, and developmental reforms in the past few years, intending to keep pace with global political and economic developments and serve its interests. (Moshashai et al., 2020) The most notable of these initiatives was a set of programs aimed at economic reform by diversifying the economy on the one hand, enhancing sustainability, and improving the quality of life on the other hand. The most prominent of these initiatives are Saudi Vision 2030, the National Transformation Program 2020, and the Public Investment Fund. By diversifying and enhancing the Saudi economy, lowering reliance on oil, and allowing the private sector to play a significant role in the economy, Saudi Vision 2030 aims to establish Saudi Arabia as a global economic hub.

In other words, it provides a comprehensive and all-encompassing road map for the country’s economic, social, and political transformation. On the other hand, the National Transformation Program 2020 is one of the primary means of achieving Vision 2030, as well as developing infrastructure and preparing the environment for the public and private sectors to achieve economic development objectives (Moshashai et al., 2020). Finally, the Public Investment Fund, which is among the world’s largest sovereign funds, is dedicated to advancing Vision 2030 by channeling investments into major projects within Saudi Arabia and globally. These projects play a crucial role in diversifying the national economy as part of the broader strategy (Sam, 2023).

Importantly, economic diversification under Vision 2030 is not only a developmental priority but also a structural anti-corruption measure. By weakening the economic foundations that traditionally facilitated patronage networks and elite capture, these reforms help build institutional resilience, reduce opportunities for abuse of power, and promote greater transparency in public finance. This often leads to improved legal structures, greater oversight, and stronger enforcement mechanisms—all of which are essential in preventing corruption. For instance, the move to privatize parts of the healthcare and education sectors necessitates higher levels of regulatory scrutiny and financial transparency. This discourages informal networks and illicit deals, such as those commonly observed in public procurement and contracts.

The role of the Saudi Vision 2030 in addressing economic challenges

The Saudi Vision was introduced in 2016 as a long-term plan to achieve its strategic objectives by 2030. (Saudi Vision 2030, 2023) Among the most prominent economic challenges facing Vision 2030 are the heavy reliance on oil, limited job opportunities leading to high unemployment rates (see Fig. 6), and insufficient private sector investment in non-oil industries such as tourism and sports.

Despite the fact that we are only halfway there, numerous official reports show that the vision is succeeding in many of its objectives and projects (Ministry of Economy and Planning, 2024). For instance, according to the vision’s key performance indicators, non-oil activities contribute 50% of GDP in 2023, a historic figure for a country whose economy is heavily reliant on oil and other energy sources for revenue (Saudi Vision 2030, 2023). Additionally, reports show that by the end of 2023, inflation had dropped by 1.6% from 3.1% in 2022 (Saudi Vision 2030, 2023). Furthermore, the vision played a role in expanding employment prospects, resulting in a decrease in Saudi Arabia’s unemployment rate from 8% in 2022 to 7.7% in 2023. See Fig. 6. Furthermore, the value of the assets of the Public Investment Fund increased by roughly 2.09 trillion compared to 2016, reaching 2.81 trillion Saudi riyals by the end of 2023. This exceeds the general target set by the vision, which was estimated at 2.7 trillion riyals (Saudi Vision 2030, 2023).

The “Resource Curse” and its implications

The concept of the “Resource Curse” and its potential impact on economies

The concept of the resource curse is a relatively new and widely used term in political and economic circles. This notion refers to the phenomenon whereby nations endowed with abundant natural resources—such as gas, oil, and the like—frequently experience slow economic growth and are afflicted by corruption, which has an impact on both their political and financial systems (Lashitew et al., 2021). In one way or another, this results in these nations’ incapacity to completely capitalize on the wealth of their natural resources and in the government’s failure to accomplish successful economic and social development to satisfy the fundamental requirements of the populace.

The foundation of this concept is these countries’ complete reliance on natural resources as a single source of income, which makes the economy vulnerable and unstable in the face of global market fluctuations. For instance, in their study, Gröning and Busse investigated the impact of natural resource abundance on governance indicators (Busse and Gröning, 2013). It discovered a direct correlation between oil exports and higher levels of corruption in countries rich in oil. The study analyzed data from a selection of natural resource-rich countries over a period of time from 1984 to 2007, involving nearly 130 countries in a panel setting. Moreover, Okada and Samreth investigated the effect of oil rents on corruption in 157 countries (Okada and Samreth, 2017). The research findings indicate a persistent positive correlation between elevated oil rents and increased instances of corruption. The study also discovered that, in nations with moderate levels of corruption, the impact of oil rents on corruption was more significant, whereas in highly corrupt countries, its effect was less noticeable (Okada and Samreth, 2017).

What are the factors that contribute to the resource curse?

Current studies suggest that the “resource curse” can have significant negative consequences, including increased corruption (Sharma and Mishra, 2022). However, the relationship between natural resources and corruption is complex and influenced by various factors, such as the quality of government institutions, economic diversification, and democratic institutions. In a recent study conducted by Narh in 2023, the author demonstrates a significant correlation between the resource curse and the quality of government institutions (Narh, 2023). The study suggests that higher-quality government institutions play a crucial role in mitigating the adverse effects and risks associated with the resource curse. As a result, one of the factors influencing this is improving the quality of these government institutions through long-term development plans, as well as improving and enacting regulations designed to protect these institutions from favoritism and corruption.

Moreover, numerous studies have revealed the importance and role of economic diversification in resource-rich countries in mitigating the effects of the resource curse (Lashitew et al., 2021). Diversification in the economy reduces the economy’s reliance on oil revenues as the sole source of income, lowering the impact and possibility of exposure to global market fluctuations (Charfeddine and Barkat, 2020). Furthermore, diversification contributes to the creation of new and promising investment opportunities for both domestic and international investors in other critical sectors such as industry, tourism, education, and others. Finally, economic diversification involves expanding a country’s economy by reducing its reliance on a single industry or sector (Matallah, 2020). This strategy aims to decrease the concentration of power and wealth in one sector, potentially leading to increased opportunities for competition and innovation in various areas such as industry, trade, and tourism. By diversifying the economy, countries can create a more stable and resilient economic foundation while also fostering growth and development in multiple sectors.

Discussion

1. How has Saudi Arabia managed to avoid or reduce the negative impacts of the resource curse? Why is its economy not as severely affected by corruption?

Oil revenues and corruption risks

While oil revenues have undeniably played a central role in Saudi Arabia’s economic development, they have also created conditions conducive to certain types of corruption. Resource-rich states often fall into what is known as the “rentier state model,” where government income is primarily derived from rents (such as oil revenues) rather than taxation. This economic structure can reduce the need for government accountability to citizens and diminish public scrutiny over state spending. As a result, oil wealth can create fertile ground for rent-seeking behavior, patronage networks, and weak financial oversight.

In Saudi Arabia, the sheer scale of oil income has historically allowed for discretionary public spending with limited transparency, which in turn increases the risk of corruption crimes such as bribery, embezzlement, and abuse of public funds. The centralization of oil revenues in state hands enables elite capture, where those with access to political power disproportionately benefit from public wealth through illicit means. In such environments, institutions may struggle to enforce anti-corruption measures effectively, especially when political or social elites are involved.

Oil wealth as a buffer

At the same time, Saudi Arabia’s oil wealth has paradoxically insulated the economy from the worst consequences of corruption. Because oil revenues generate substantial fiscal surpluses, the government has been able to maintain high levels of public investment, infrastructure development, and social spending—even when corruption siphons off some public resources. In other words, the sheer volume of oil income has, to some extent, cushioned the economic impact of corruption, masking inefficiencies and losses that might cripple a less resource-rich economy.

However, this buffering effect does not eliminate the underlying risks. If global oil prices fall significantly or long-term diversification efforts stagnate, the protective role of oil wealth could weaken. In this sense, Saudi Arabia’s resilience may not only stem from oil revenues but also from institutional reforms, strong centralized governance, and a recent push for transparency and accountability through agencies like Nazaha and broader Vision 2030 reforms.

Recent economic performance provides empirical support for this dynamic. For instance, in 2022, Saudi Arabia showcased remarkable resilience amidst global economic disruption and ongoing internal corruption investigations involving senior officials. According to data from the World Bank, the nation achieved an impressive real GDP growth rate of 7.5%, a testament to its capability to sustain economic momentum in challenging times. (World Bank Open Data, 2023)This growth was underpinned by ambitious infrastructure initiatives, such as NEOM, the futuristic city project, the Line, a revolutionary urban development, and the Red Sea Project, which collectively attracted significant foreign investment, reflecting strong market confidence in the country’s economic direction. Furthermore, the government demonstrated a commitment to progress by increasing public spending on infrastructure and development to approximately 1.285 billion Saudi riyals, despite the backdrop of rising corruption cases. These strategic investments indicate a determination to push forward with development and modernization, even in the face of adversity (Ministry of Finance, 2024a, 2024b).

Balancing rentier benefits and institutional capacity

Thus, Saudi Arabia’s case reveals a dual dynamic: oil wealth increases vulnerability to corruption through rent-seeking incentives but also equips the state with financial means to mitigate its effects. The country’s resilience is therefore not solely a product of oil abundance, but also of deliberate institutional efforts to strengthen the rule of law, build anti-corruption capacity, and diversify the economy. This balance between structural risk and policy response is central to understanding how the Saudi model diverges from other resource-rich states that have succumbed to the resource curse. Consequently, these factors play a vital role in mitigating corruption’s impact on the Saudi economy:

a. Oil revenues: Over the years, Saudi Arabia has relied solely on oil revenues as the primary foundation of its economy. This dependence was the cornerstone of its evolution and achievements throughout its journey from the beginning of the 1930s. Saudi official sources indicate that natural resources have been the backbone of the country and also shape roughly 75% of its income (Ministry of Finance, 2024b). Therefore, significant oil revenues have been instrumental in offsetting budget deficits resulting from issues like corruption or other issues. These revenues also played a crucial role in mitigating the effects of any shortages or other economic challenges. For example, in 2023, Saudi Arabia’s oil revenues amounted to approximately 1.21 trillion Saudi riyals, reflecting the immense financial significance of the oil industry to the country (Ministry of Finance, 2024a). The exact figures regarding the total extent and amount of corruption are not readily available. However, it is important to note that there were approximately 45,000 to 48,000 documented incidents of financial and administrative corruption in the previous year (Nazaha, 2023). It is essential to acknowledge that while these reported cases are concerning, they might only represent a small percentage of the overall oil revenues. This suggests that, within the Saudi context, the substantial oil wealth could be seen as more of a blessing than a curse.

b. Government Support: Saudi Arabia is a monarchy and an economy that relies heavily on oil revenues. This heavy reliance on a single natural resource has led to its economy being described as a “rentier economy” (Lashitew and Werker, 2020). Countries whose economies are heavily dependent on income from natural resources such as oil or gas often face challenges related to the volatility of these resources’ prices and their direct impact on government revenues. Despite the challenges posed by dependence on oil, there are positive aspects to this economic system.

Huge oil revenues have enabled the Saudi government to achieve many accomplishments, such as infrastructure, government support, and investments. Saudi Arabia has demonstrated great resilience to global economic challenges due to several factors: the sovereign wealth fund, large cash reserves, strategic vision, and rapid response to crises. Examples of Saudi Arabia’s resilience include the 2014 global oil crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the Saudi economy is heavily dependent on oil, the Kingdom has demonstrated its ability to withstand and adapt to global economic challenges. This is thanks to wise economic policies, significant investments in infrastructure, and an ambitious strategic vision to diversify the economy. This also explains why Saudi Arabia and its citizens have not been significantly or profoundly affected by the political and economic upheavals that have swept through the region. However, achieving full economic diversification requires sustained efforts and wide-ranging structural reforms.

c. Government Anti-Corruption Agencies: In addition to the previously mentioned reasons, the presence and effectiveness of anti-corruption agencies—known by various names, such as Nazaha, the Administrative Investigation Authority, and the Oversight and Investigation Authority—have likely played a significant role in Saudi Arabia’s ability to mitigate the effects of corruption. The main goal of these agencies is to enhance accountability and transparency within government bodies, allowing for increased oversight and investigation of corrupt activities.

In 2019, the Saudi government announced a significant restructuring of its anti-corruption efforts by merging two key agencies—the Administrative Investigation Authority and the Oversight and Investigation Authority—into the already existing Nazaha (Saudi Royal Decree No. (A/277), 2019). This merger marks a pivotal shift in the country’s approach to combating corruption.

With this new structure, Nazaha has been granted broader authority and resources to investigate instances of corruption. It retains most of the powers of the previous agencies while maintaining its own authority. Crucially, Nazaha is now able to pursue corrupt individuals regardless of their government positions or social standing, ensuring that no one is above the law. By consolidating these functions under one commission, Saudi Arabia aims to create a more effective and cohesive strategy to promote transparency and accountability in the public sector.

This authority had a significant influence on several cases that Nazaha uncovered, which demonstrated the involvement of some ministers and their deputies, as well as businessmen and princes from the royal family. These cases have reinforced and affirmed the effectiveness of this authority (Nazaha). This underscores a robust political resolve to tackle corruption at the highest levels of the government and to ensure the requisite backing for these anti-corruption endeavors.

In 2024, Royal Decree No. M/25 brought about significant changes to the organization of the Oversight and Anti-Corruption Authority (Nazaha). The decree provided a clearer definition of corruption crimes, particularly in Article Two, which outlined specific offenses such as bribery, misappropriation of public funds, abuse of power, and any other acts categorized as corruption under existing laws. These offenses were designated as falling within the jurisdiction of Nazaha.

Furthermore, the reorganization led to the establishment of specialized units within Nazaha, each with its own distinct focus. (Saudi Royal Decree No. (M/25), 2024) These units include the Anti-Corruption Unit, the Integrity Protection and Transparency Enhancement Unit, the Administrative Oversight and Investigation Unit, the Criminal Investigation and Prosecution Unit, and the International Cooperation Unit. These units serve to enhance Nazaha’s capabilities in addressing corruption and promoting transparency both domestically and internationally.

As a result, the effectiveness of these government agencies—embodied in the Authority (Nazaha)—in battling corruption and addressing this crime with significant economic, political, and social ramifications serves as constant evidence of the scope of corruption in Saudi Arabia as well as the promptness of the government’s response in apprehending offenders and bringing them to justice. Furthermore, Nazaha’s role in increasing awareness is demonstrated by its monthly publication of information about the inspection tours it undertakes throughout different regions, the number of people they have arrested and investigated, and the decisions it makes for those who are being held in these cases (Nazaha, 2024). Thus, the agency plays a vital role in discouraging individuals from engaging in corruption or misusing their positions of power for personal gain. Additionally, it promotes a culture of transparency in its operations, which is essential for building public trust and accountability. While it is important to acknowledge that no single agency can entirely eliminate corruption, Nazaha has the potential to significantly reduce and limit opportunities for corrupt activities, fostering a more honest and ethical environment among government institutions.

On February 18, 2024, Saudi Arabia introduced the Whistleblower, Witness, Expert, and Victims Protection Law (The Whistleblower, Witness, Expert, and Victim Protection Act, 2024). This modern legislation is designed to protect all whistleblowers and witnesses involved in serious crimes that warrant arrest. Examples of such crimes in Saudi Arabia include embezzlement, financial fraud, and corruption, all of which can lead to imprisonment for more than 3 years.

The law also establishes penalties for anyone who uses force or violence against a protected person after they have disclosed the truth, or who tries to intimidate them into silence. This includes threats, blackmail, or offering gifts or benefits to persuade a protected person not to reveal the truth. Additionally, anyone who intentionally discloses information that could harm a protected person is also subject to penalties.

Furthermore, the law classifies any offenses committed by public employees or individuals in similar positions—related to the crimes mentioned in Articles 24, 25, and 26 of the law—as acts of corruption. The legislation enforces criminal penalties for any behavior that could harm those under protection, including imprisonment for up to three years and fines of up to five million riyals.

d. The Rule of Law: The rule of law is a fundamental principle that holds that everyone is subject to the law and that the law protects all people’s rights and freedoms equally (Lucy, 2020). When the rule of law prevails in a country, it fosters a stable and transparent environment that attracts investment and reduces corruption. Therefore, when discussing the role of government institutions in uncovering corruption cases, it is crucial not to discriminate between corrupt individuals, whether they are ordinary citizens, ministers, princes, or high-ranking businessmen. As a result, the rule of law has a significant impact on neutralizing the effects of corruption and not favoring officials and those in high positions in the state, which positively reflects in the strengthening of political and economic stability (Djouadi et al., 2024).

In recent years, starting in 2017, the Saudi government has placed great emphasis on strengthening the rule of law. This period coincided with the appointment of Prince Mohammed bin Salman as Crown Prince, during which significant economic reforms were introduced (Saudi Royal Decree No. M/73, 2022). Additionally, the government focused on developing laws to address corruption, which included the establishment of specialized courts dedicated to handling corruption cases. Saudi Arabia has demonstrated a strong dedication to enhancing transparency and accountability within its legal framework (Alatawi, 2024). This commitment involves the implementation of various mechanisms to ensure that individuals who breach the law are held accountable for their actions. The overarching goal is to combat corruption, foster confidence in governmental bodies, and reinforce the autonomy of the judiciary. These initiatives are instrumental in upholding the impartiality of the judicial process when addressing cases involving corruption, abuse of power for personal gain, and other related decisions.

2. What lessons can be drawn from Saudi Arabia’s experience with the economic effects of corruption for other countries facing comparable challenges?

The relationship between corruption, economic growth, and economic stability is complex and influenced by many factors. While corruption can hinder economic growth, elements such as effective economic management and diversification also play essential roles. Overreliance on natural resources can generate wealth, but it can lead to corruption and fluctuations in economic growth if not properly managed.

It’s important to consider that economic conditions in countries can change over time due to various factors, including wars and political transformations. The effectiveness of the legal system is crucial in the fight against corruption. Furthermore, many countries—especially those rich in natural resources—should focus on diversifying their economies to ensure stability and adaptability in the face of global challenges.

Being able to adapt swiftly to economic changes and consistently implement reforms is vital for addressing issues in a timely and organized manner. Finally, anti-corruption agencies are essential in reducing the impact of corruption by promoting accountability and transparency. The independence of these agencies is key to ensuring that everyone, regardless of political or social status, is held accountable under the rule of law.

Saudi Arabia’s journey toward economic resilience in the face of corruption can be better understood when compared to other resource-rich countries like Nigeria and Norway. Despite being Africa’s largest oil producer and having significant oil wealth, Nigeria has experienced the “resource curse,” characterized by chronic corruption, weak institutions, and economic instability (Amundsen, 2017; Olujobi, 2021). Ongoing mismanagement and a lack of transparency have hindered infrastructure development and discouraged foreign investment.

In contrast, Norway—another oil-rich nation—has successfully managed to build strong institutions, maintain transparency, and invest its oil revenues into a sovereign wealth fund that promotes long-term economic stability. Norway’s focus on transparency and accountability has enabled it to maintain steady economic performance and avoid the common pitfalls associated with the resource curse (Halonen, 2014; Norouzi and Ataei, 2022). Saudi Arabia seems to follow a middle path: although corruption remains a challenge, the country has made deliberate efforts to reform its institutions. Its anti-corruption measures and economic diversification initiatives have alleviated many of the typical impacts associated with the “resource curse.” This comparison underscores the importance of governance quality in shaping how resource wealth influences economic resilience.

Results and recommendations

Key findings

This study has identified several significant findings concerning the relationship between corruption and economic resilience in Saudi Arabia:

-

a.

As documented by Nazaha, reported corruption cases in Saudi Arabia have increased significantly in recent years. However, this rise can likely be attributed to improvements in detection, reporting mechanisms, and government transparency, rather than an actual increase in the perception of corruption.

-

b.

Saudi Arabia’s economic resilience appears to be influenced by multiple factors beyond oil wealth, including proactive anti-corruption measures, strong centralized governance, a strategic vision for economic diversification (Vision 2030), and substantial government public investments.

-

c.

Despite its characteristics as a rentier state, Saudi Arabia has implemented significant institutional reforms that mitigate the risks traditionally associated with the resource curse, corruption, and financial crimes. These reforms include legal reforms, the restructuring of Nazaha (the Oversight and Anti-Corruption Authority), economic reforms, and enhanced enforcement mechanisms.

-

d.

While oil wealth can serve as both a risk factor and a buffer, it presents incentives for rent-seeking and corruption, as well as a reduction in financial transparency. However, it also provides the fiscal flexibility needed to absorb inefficiencies associated with corruption without causing immediate economic instability.

-

1.

Policy recommendations

Based on these findings, the following recommendations are proposed to strengthen anti-corruption efforts and further enhance Saudi Arabia’s economic resilience:

-

a.

Implement Clear Transparency and Reporting Standards for Corruption Cases. Mandate that Nazaha and relevant judicial bodies publish comprehensive public reports that classify corruption cases into distinct categories: reported, under investigation, prosecuted, or adjudicated. Additionally, establish a centralized digital transparency portal that allows the public to access annual corruption data, promoting external oversight and supporting academic research.

-

b.

To safeguard the operational independence of Nazaha, it is essential to implement legislative measures that protect it from interference by political or executive branches. This will ensure that Nazaha can conduct investigations and prosecutions autonomously. Additionally, oversight mechanisms should be established to evaluate Nazaha’s annual performance, which will enhance institutional accountability while maintaining its independence.

-

c.

Enhance Whistleblower Protection Frameworks. Enact a comprehensive whistleblower protection law that ensures confidentiality, grants legal immunity, and includes anti-retaliation provisions for individuals reporting corruption. Establish an independent reporting channel, separate from the standard bureaucratic structure, to encourage disclosures from employees in both the public and private sectors.

-

d.

Implement Risk-Based Integrity Reviews in High-Risk Sectors. Mandate corruption risk assessments in sectors with significant public spending, such as infrastructure, defense, healthcare, and procurement. Establish integrity compliance units within ministries and state-owned enterprises to oversee contract transparency, vendor vetting, and the management of conflicts of interest.

-

e.

Enhance preventive education and ethics training by integrating anti-corruption and public ethics modules into training programs for civil servants, law enforcement personnel, and judicial officers. Collaborate with universities, think tanks, and media organizations to raise awareness about anti-corruption efforts and foster a culture of transparency and accountability.

-

2.

Future research

While this study provides insights into the interplay between corruption and economic resilience in Saudi Arabia, several avenues remain open for further academic exploration:

-

a.

Comparative Studies: Future research could compare Saudi Arabia’s experience with other natural resource-rich countries, such as the Gulf Cooperation Council, to identify applicable strategies and challenges in each context.

-

b.

Impact of Legal Reforms: Empirical studies could evaluate the effectiveness of recent legal reforms, such as the restructuring of Nazaha and the establishment of specialized anti-corruption courts.

-

c.

Analyzing the Economic Impact of Corruption: Future research also should aim to quantitatively assess the direct and indirect economic costs of corruption in Saudi Arabia. This includes examining how specific types of corruption (such as procurement fraud, embezzlement, and favoritism) affect GDP growth, investment flows, and public trust in institutions. Sectoral analysis—particularly in high-risk sectors such as construction, defense, and healthcare—would provide a more detailed perspective.

VII. Limitation

-

1.

A major limitation of this study is its dependence on reported cases of corruption, which may not fully reflect the entire legal process of each case. Additionally, the absence of publicly accessible disaggregated data on the prosecution and adjudication stages hinders the ability to evaluate the effectiveness of enforcement.

-

2.

This research focused on understanding why the Saudi economy remains stable and flexible despite the presence of corruption and the factors that may influence this. Although comparing the economic performance of other countries and linking them to the concept of corruption and its impact may provide further insight, this was not within the scope of this research.

-

3.

The definition of corruption and its extent may vary from one country to another. Its direct impact on the economy may be influenced by other factors, such as social or political ones. Generalizing the results would not be accurate due to the differing circumstances between countries based on these considerations.

-

4.

The sources providing data on corruption may vary greatly, making it difficult to obtain reliable and comparable figures. This is due to the different methodologies used in collecting and analyzing data, leading to varying results. Additionally, the sensitive nature of this topic often leads some parties to hide or provide inaccurate information, further complicating the process of obtaining a clear picture of the extent and levels of corruption. Therefore, the differences in data greatly impact the quality of research and studies on this topic. These variations in methodologies make it challenging to build accurate statistical models and generalize the results, thus limiting our ability to understand the scope of this issue and its impact on society.

-

5.

There may not be a direct relationship between the level of corruption and the economic performance of countries. Some countries with high levels of corruption may still achieve significant and stable economic growth, while others with relatively low corruption rates may struggle economically.

Conclusion

This study examined the complex relationship between corruption crimes and economic resilience in Saudi Arabia. It revealed that, despite persistent challenges such as bribery, embezzlement, and abuse of power, the country has maintained notable economic stability and growth. These findings support recent research that emphasizes the importance of strong institutions, as well as policy and legal reforms, in mitigating the negative effects of corruption (Heywood, 2018; Kaufmann et al., 2002).

While the prevailing view in the literature suggests that corruption undermines growth by distorting markets and weakening governance (Kolstad and Wiig, 2009; Mauro, 1995), Saudi Arabia’s experience presents a nuanced exception: strong state capacity, strategic management of oil revenues, and proactive anti-corruption measures have facilitated continued progress.

Contrary to the “grease the wheels” hypothesis (Leff, 1964), which claims that corruption can promote development in rigid bureaucracies, this research indicates that Saudi Arabia’s economic resilience results not from tolerating corruption but from actively confronting it. Key components of this strategy include legal reforms, empowering oversight bodies, and pursuing economic diversification under Vision 2030. By comparing Saudi Arabia’s trajectory with that of other resource-rich nations, this research highlights the critical importance of coherent anti-corruption policy, institutional integrity, and political commitment in reducing the economic impacts of corruption and securing sustainable development.

The findings suggest that policymakers may need to devise more effective strategies to combat corruption, as official statistics indicate that corruption remains widespread in Saudi Arabia. This research contributes to the growing body of literature on the intricate relationship between corruption and economic growth by delivering a context-specific analysis of a resource-dependent economy that is actively pursuing reform initiatives. It offers valuable insights for policymakers and researchers, recommending further exploration of this relationship in various contexts to develop actionable recommendations for promoting sustainable development and effectively combating corruption.

Data availability

All data supporting this study's findings are publicly available or may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ahmad E, Tanzi V (2002) Managing Fiscal Decentralization. Pitfalls on the road to fiscal decentralization (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) 328

Akinsola K (2025) Legal oversight of state-owned enterprises: governance structures, compliance, and public accountability (SSRN Scholarly Paper 5128102). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5128102

Alatawi OD (2023) The role of decentralization in combating corruption in Saudi Arabia [PhD Dissertation]. University of The Pacific

Alatawi OD (2024) The Saudi Arabian legal system’s approach to white-collar crimes: challenges and potential reforms. Cogent Soc Sci 10(1):2413622

Alaye A, Ogunbanwo O (2024) Oil Politics and Governance: emerging socio-economic trends in Nigerian states. Acta Universitatis Danub Jurid 20:126

Al-Ghannam F (2011) The extent of the effectiveness of modern methods in combating administrative corruption (from the point of view of members of the Saudi Shura Council). Naif Arab University for Security Science

Ali HE, Bhuiyan S (2022) Governance, natural resources rent, and infrastructure development: evidence from the Middle East and North Africa. Polit Policy 50(2):408–440

Al-Shammari A, Abu Bakr M (2013) Administrative corruption, its phenomena and ways to treat it. King Saud Univ-Deans Sci Res 8(3):83

Altorkostani B (2023) Corruption and its impact on economic performance in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. World Res Bus Adm J 3(1):35–86

Amundsen I (2017) Nigeria: defying the resource curse. In Corruption, Natural Resources and Development (17–27). https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/edcoll/9781785361197/9781785361197.00008.xml

Ansari D (2017) OPEC, Saudi Arabia, and the shale revolution: insights from equilibrium modelling and oil politics. Energy Policy 111:166–178

Busse M, Gröning S (2013) The resource curse revisited: governance and natural resources. Public Choice 154:1–20

Bussell J (2015) Typologies of corruption: a pragmatic approach. In greed, corruption, and the modern state: essays in political economy. Edward Elgar Publishing

Charfeddine L, Barkat K (2020) Short- and long-run asymmetric effect of oil prices and oil and gas revenues on the real GDP and economic diversification in oil-dependent economy. Energy Econ 86:104680

Djouadi I, Zakane A, Abdellaoui O (2024) Corruption and economic growth nexus: empirical evidence from dynamic threshold panel data. Bus Ethics Leadersh 8(2):49–62

Dreher A, Gassebner M (2013) Greasing the wheels? The impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. Public Choice 155(3):413–432

Dreher A, Schneider F (2010) Corruption and the shadow economy: an empirical analysis. Public Choice 144(1):215–238

Ellili N, Nobanee H, Haddad A, Alodat AY, AlShalloudi M (2024) Emerging trends in forensic accounting research: bridging research gaps and prioritizing new frontiers. J Econ Criminol 4:100065

Grand S, Wolff K (2020) Assessing Saudi Vision 2030:a 2020 review. Atl Counc 17(1):1–80

Halonen A-B (2014) Avoiding the curse by transparency and ethics?: A comparative study of the transparency and ethical principles of the sovereign wealth funds of Norway and Kazakhstan [Master thesis, Universitet i Agder/University of Agder]. https://uia.brage.unit.no/uia-xmlui/handle/11250/219941

Haque MI, Tausif MR (2025) Entrepreneurship, oil rents and corruption in Middle East and North African countries. Soc Sci Humanit Open 11:101341

Heywood PM (2018) Combating corruption in the twenty-first century: new approaches. Daedalus 147(3):83–97

Huntington SP (1968) Political Order in Changing Societies. (1st ed). Yale University Press

IMF (2024) Republic of Uzbekistan: Selected Issues. International Monetary Fund (211):22. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798400283345.002.A001

Johansson S (2023) Is there a proper way to combat corruption?: A comparison of the anti-corruption strategies of Iran, Thailand, Denmark, and Singapore [Linnaeus University]. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-126947

Johnston M (2005) Syndromes of corruption: wealth, power, and democracy. Cambridge University Press

Karl TL (1997) The paradox of plenty: oil booms and petro-states. University of California Press

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Lora E, Pritchett L (2002) Growth without governance [with Comments]. Econ ía 3(1):169–229

Kolstad I, Wiig A (2009) Is transparency the key to reducing corruption in resource-rich countries? World Dev 37(3):521–532

Lashitew AA, Ross ML, Werker E (2021) What drives successful economic diversification in resource-rich countries? World Bank Res Obs 36(2):164–196

Lashitew AA, Werker E (2020) Do natural resources help or hinder development? Resource abundance, dependence, and the role of institutions. Resour Energy Econ 61:101183

Leff NH (1964) Economic development through bureaucratic corruption. Am Behav Scientist 8(3):8–14

Lucy W (2020) Access to justice and the rule of law. Oxf J Leg Stud 40(2):377–402

Lyra MS, Damásio B, Pinheiro FL, Bacao F (2022) Fraud, corruption, and collusion in public procurement activities, a systematic literature review on data-driven methods. Appl Netw Sci 7(1):83

Magakwe J (2024) Curbing corruption, bribery, and money laundering in public procurement processes: an international perspective. In Corruption, Bribery, and Money Laundering—Global Issues (156). IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.1004005

Matallah S (2020) Economic diversification in MENA oil exporters: understanding the role of governance. Resour Policy 66:101602

Mauro P (1995) Corruption and growth. Q J Econ 110(3):681–712

Mauro P (1996) The effects of corruption on growth, investment, and government expenditure. IMF Working Papers 98:1–28

Méon P-G, Sekkat K (2005) Does corruption grease or sand the wheels of growth? Public Choice 122(1):69–97

Ministry of Economy and Planning (2024) Ministry of Economy and Planning Annual Indicators [Annual]. https://mep.gov.sa/ar/knowledge-base/annual-indicators

Ministry of Finance (2024a) Saudi Ministry of Finance—Official website. https://www.mof.gov.sa/en/Pages/default.aspx

Ministry of Finance (2024b) Budget Statement 2024—Fiscal Year 2024. https://www.mof.gov.sa/en/budget/2024/Pages/default.aspx

Ministry of Investment (2024) Saudi Arabian Ministry of Investment [Gov]. https://misa.gov.sa/ar/

Moshashai D, Leber AM, Savage JD (2020) Saudi Arabia plans for its economic future: Vision 2030, the National Transformation Plan and Saudi fiscal reform. Br J Middle East Stud 47(3):381–401

Mugellini G, Della Bella S, Colagrossi M, Isenring GL, Killias M (2021) Public sector reforms and their impact on the level of corruption: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev 17(2):e1173

Mulenga R (2024). Navigating global economic volatilities: towards economic resilience. J Econ, Finance Manag (JEFM), 3(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10822328

Narh J (2023). The resource curse and the role of institutions revisited. Environ Dev Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-04279-6

Nazaha (2015) Wasta, its concept, causes and effects (32;1–28)

Nazaha (2020) Nazaha annual report [Annual]. Oversight and Anti-Corruption Authority

Nazaha (2021) Nazaha annual report (p. 8). Oversight and Anti-Corruption Authority

Nazaha (2022) Nazaha annual report. Oversight and Anti-Corruption Authority

Nazaha (2023) Nazaha annual report. Oversight and Anti-Corruption Authority

Nazaha (2024). Nazaha official website. https://www.nazaha.gov.sa/

Nazaha (2025). Nazaha annual report. Oversight and Anti-Corruption Authority

Norouzi N, Ataei E (2022) Transition of a rentier oil country to a sustainable economy: a case study for Norway. Thail World Econ 40(1):39–68

Okada K, Samreth S (2017) Corruption and natural resource rents: evidence from quantile regression. Appl Econ Lett 24(20):1490–1493

Olujobi OJ (2021) Nigeria’s upstream petroleum industry anti-corruption legal framework: the necessity for overhauling and enrichment. J Money Laund Control 26(7):1–27

OPEC: OPEC Basket Price (2023). https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/data_graphs/40.htm

Pozsgai-Alvarez J (2020) The abuse of entrusted power for private gain: Meaning, nature and theoretical evolution. Crime Law Soc Change 74(4):433–455

Ramady MA (2010) The Saudi Arabian Economy: policies, achievements, and challenges. Springer Science and Business Media

Rose-Ackerman S (2007) International handbook on the economics of corruption. Edward Elgar Publishing

Ross ML (2012) The oil curse: how petroleum wealth shapes the development of nations. Princeton University Press, https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781400841929/html

Rothstein B (2011) Anti-corruption: the indirect ‘big bang’ approach. Rev Int Political Econ 18(2):228–250

Sam AJ (2023) Saudi Arabia’s public investment fund as a tool for economic diversification and sports diplomacy [Leipzig University] https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.33191.32167

Saudi Royal Decree No. (A/277) (2019). www.spa.gov.sa/2010367

Saudi Royal Decree No. (M/25) (2024)

Saudi Royal Decree No. M/73 (2022)

Saudi Royal Decree No. (M/110) (2022)

Saudi Vision 2030 (2023) Saudi Vision 2030 Annual Report 2023. https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/ar/annual-reports

Sharma C, Mishra RK (2022) On the good and bad of natural resource, corruption, and economic growth nexus. Environ Resour Econ 82(4):889–922

Song C-Q, Chang C-P, Gong Q (2021) Economic growth, corruption, and financial development: global evidence. Econ Model 94:822–830

SPA Saudi Press Agency (2014) Al-Sharif: the establishment of “Nazaha” reflects the serious desire to investigate corruption. Al-madina Newspaper, 6

Spyromitros E, Panagiotidis M (2022) The impact of corruption on economic growth in developing countries and a comparative analysis of corruption measurement indicators. Cogent Econ Financ 10(1):2129368

Susilo J (2024) Literature review: the impact of corruption on economic growth, a case study by country: Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkiye. AICOS: Asian Journal Of Islamic Economic Studies, 1(01), Article 01

Tanzi V (1998) Corruption around the world: causes, consequences, scope, and cures. Staff Pap 45(4):559–594

The Whistleblower, Witness, Expert, and Victim Protection Act, Pub. L. No. M/148 (2024)

Transparency International (2024) Saudi Arabia. Transparency.Org. https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/saudi-arabia

Vision 2030 (2016) Saudi Arabia Vision 2030: an ambition nation section, effectively governed. Government of Saudi Arabia. https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/rc0b5oy1/saudi_vision203.pdf

Waheed R, Sarwar S, Dignah A (2020) The role of non-oil exports, tourism and renewable energy to achieve sustainable economic growth: what we learn from the experience of Saudi Arabia. Struct Change Econ Dyn 55:49–58

Wang G, Sharma P, Jain V, Shukla A, Shahzad Shabbir M, Tabash MI, Chawla C (2022) The relationship among oil prices volatility, inflation rate, and sustainable economic growth: evidence from top oil importer and exporter countries. Resour Policy 77:102674

Wei S-J (2002) Corruption in economic transition and development: grease or sand? United Nation-UNECE 1:1–36

World Bank (2020) Combating Corruption. World Bank Publications. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/governance/brief/combating-corruption

World Bank Open Data (2023) World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org

Williams JW, Beare ME (1999) The business of bribery: Globalization, economic liberalization, and the "problem" of corruption. Crime Law Soc Change 32(2):115–146. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008375930680

Author information

Authors and Affiliations