Abstract

China is experiencing rapid urbanisation and population ageing. Older people need to age-in-place healthily to reduce the health and social care pressure on families and the government. Studies have explored older people’s need for community care in China, and the importance of neighbourhoods. Affordance theory, central to understanding how individuals perceive the environment, has been widely used in child-related research, but rarely applied to the ageing population. This is closely linked to person-environment fit, achieved when people can interact positively with the built environment including open spaces. The main residential types in urban China are work-unit (Danwei) communities and commodity communities, but research on ageing-in-place in these settings remains limited, especially regarding the role of neighbourhood outdoor space. This article explores older people’s experiences of ageing in both settings, how they exercise, adapt to changing environments, and how neighbourhood outdoor space supports age-in-place. Interviews were conducted with 42 older people from both community types, and thematic analysis was employed using NVivo 15 software. Findings revealed that older people in the work-unit community expect more from community care services, while social isolation is a risk in both settings. Neighbourhood outdoor spaces are perceived as important places for physical exercise and social interaction. Engagement with these spaces is often supported by adult children, partners and neighbours. However, caregiving responsibilities for grandchildren can hinder older people’s use of outdoor space and socialisation. Participants demonstrated adaptations they made to fit with the physical and social environments of their neighbourhood. Therefore, future building or retrofitting of age-friendly community environments and care services should support older people’s use of outdoor spaces to maintain health and socialisation. Importantly, the lack of older residents’ involvement in age-friendly community retrofitting challenges their adaptation to evolving physical and social environments, which is essential for ageing-in-place.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The one-child policy in the 1970s resulted in a decline in family size combined with a sustained decrease in mortality, as well as accelerating the process of population ageing in China (Chen and Liu, 2009; Zhang, 2017). The population aged 60 and above in China is about 264 million, accounting for 18.7% of the total population (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2021). This ageing proportion is predicted to reach 35% by 2050 (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2017). The ageing demographic in China has put pressure on the healthcare and pension systems due to older people suffering from an increasing number of chronic illnesses, lack of health education and healthy behaviour promotion, as well as insufficient care resources. Issues such as unfair insurance system and the risk of long-term financial unsustainability in the pension system compound these challenges (Dong and Wang, 2014; Wang and Chen, 2014).

Ageing-in-place is a common policy response to the population ageing phenomenon (World Health Organisation 2015). This means ‘remaining living in the community, with some level of independence, rather than in residential care’ (Davey et al. 2004, p.133). It can also be understood as the individual remaining in their own home or neighbourhood and suggests that the individual is fit to meet changing conditions and needs (Fänge et al. 2012). Urbanisation and the separation of generations, as well as the continuous transformation of community environments lead older people to age in increasingly unfamiliar places, serving as key environmental factors contributing to their social exclusion (Scharf and Keating 2012). Habitation of an environment over an extended period can transform a meaningless geographic space into a place that has personal meaning, via repetition of patterns of use, increasingly differentiated awareness, and the accumulation of layers of emotional attachments (Rowles and Bernard 2013). Therefore, ageing-in-place is considered beneficial for older people’s sense of attachment, security, and familiarity with homes and communities, and is also related to their sense of identity (Wiles et al. 2012).

In China, the government has shifted away from building more nursing homes due to nursing homes are unpopular among older people as they conflict with filial piety. Additionally, the limited number of beds in these homes cannot meet the growing ageing population’s needs, and affordability remains a major issue for families (Chen and Han 2016). China is actively promoting ageing-in-place and an adequate care service system for the aged, following three principles. First, there is the need to provide care at home as the foundation for enabling older people to stay in their homes. Second, the use of community-based care services provides a support to ensure that older people have access to essential services and support within their communities. Third, the provision of care institutions forms a supplementary option for older people who need health and social care support (State Council of the People’s Republic of China 2019). Therefore, older people’s homes and residential communities are expected to take on the primary responsibility of supporting them to reside independently and to flourish for as long as possible. Cities in China are seeking to support ageing-in-place through a community-based social service paradigm. Building meaningful connections among older people and preventing social isolation via healthcare management, health education, recreational activities and volunteer participation are considered to be influential (Jiang et al. 2018).

The following sections establish the theoretical foundation for this study. They begin by explaining how the ageing process interacts with an evolving environment and underscore the benefits of green spaces for older people. The concept of affordance is then introduced as a core theoretical basis for understanding person-environment fit (P-E fit) in later life. Based on this foundation, the significance of the study, research gaps and research questions are then articulated.

Ageing and the environment

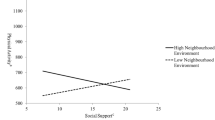

One of the most prominent theories in the field of environmental gerontology is Lawton and Nahemow’s (1973) ecology model of ageing, which introduced the P-E fit concept. They consider the ageing process as a continual adaptation to external environment and individual capabilities and functioning. The external environment compromise physical environment such as older people’s home, neighbourhood, and social environment including varied quantity and quality of social connections (Cao and Hou 2022). The individual competence differ among individuals and vary over time and encompass cognitive ability, psychological adjustment, physical health, or other qualities (Lawton and Nahemow 1973). The ecology model of ageing proposes that individual’s behaviours and outcomes depend on the interaction between personal competence and environmental press, where excessive or too little press could cause maladaptive behaviour and negative affect (Scharlach 2017). The fit between person and environment can be seen as successful adaptation, whereas misfit signifies maladaptation (Oswald and Wahl 2019). It is reasonable to assume that an adequate physical environment can support older people to build resilience against failing health; they can also negotiate with the surrounding environment and support themselves with ageing-in-place.

Healthy, accessible and supportive environments enable older people to do the things that are important to them and support their rights regarding ageing-in-place (World Health Assembly 2016). Supportive socio-material surroundings can enable older people to develop new approaches to moving outdoors and new ways to organise their daily life, even with declined mobility (Luoma-Halkola and Häikiö 2022). Therefore, ageing-in-place can be promoted by building age-friendly environments, which can maximise older people’s capacity and capabilities (World Health Organization 2015). Age-friendly features include the physical environment (outdoor spaces and buildings, transportation, housing), the social environment (social participation, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, communication and information) and municipal services (community support and health services) (World Health Organization 2017). These factors have become the focus of many scholars whose work aims to improve older people’s wellbeing, especially the built and social environments (Kim et al. 2022), to encourage civic participation (Chan and Cao 2015) and more community care services (Zhou and Walker 2021).

Benefits of green space

Three interlaced modes of how older people benefit from outdoor environments have been suggested: participation in outdoor physical activity, exposure to outdoor natural environments, and social interaction in outdoor spaces (Sugiyama and Ward Thompson 2007). There is an extensive array of research on the various benefits of participation in physical activity, such as improved strength, aerobic capacity, flexibility, physical function and cognition, and reduced risk of depression and dementia (Lee et al. 2014; Lü et al. 2016; Cunningham et al. 2020). Taking part in various activities also allows older people to feel a greater level of self-esteem and self-respect, to exercise their competence and to maintain caring and supportive relationships (World Health Organization 2007). In contrast, an outdoor environment that hinders mobility not only heightens the fear of moving outdoors and exacerbates unmet physical activity needs but is also linked to poorer quality of life among older people (Rantakokko et al. 2010). Direct contact with nature, such as fresh air, smelling flowers, hearing rustling leaves and watching wildlife, is necessary to engage the physiological, sensory, emotional and other benefits of nature (Freeman et al. 2019). Older people also perceive gardening to be vital to their physical and psychological wellbeing, as they value the aesthetics of gardens, opportunities to connect with nature and the sense of achievement that can be developed in the process (Scott et al. 2015). Apart from exposure to the natural environment, social contact is also a critical pathway to improving health and wellbeing through activities (Lovell et al. 2015). Green spaces allow older people to meet friends and socialise (Esther et al. 2017), contributing to strengthening and maintaining a sense of community and social interaction, and establishing more integrated social networks (Kweon et al. 1998; Kim and Kaplan 2004; Enssle and Kabisch 2020). Older people perceive going outdoors to be an opportunity for informal encounters with neighbours or friends, which is a source of social inclusion and identity building (Duggan et al. 2008).

Factors that impact older people’s experience of going outdoors to gain these benefits have also been explored. Older people’s mobility is embedded in the context that they live with, yet this context is not only geographically related (Schwanen and Páez 2010), but also reflects the household, family, community and society (Hanson 2010). Therefore, the social, cultural and geographic context need to be considered simultaneously when discussing mobility. For example, having grandchildren in the household positively impacts Chinese older people’s utilitarian activity patterns, which is explained by the fact that older people often take on the task of taking grandchildren to and from school (Liu et al. 2020). Partner’s health and mobility status is another aspect that impacts older people’s ability to go out. A partner with better mobility and health status can support the other’s limitations, for example, driving them places, and vice versa (Freeman et al. 2019). A stressful life event, such as changing into a single-person household in old age, can lead to reduced outdoor mobility (Stjernborg et al. 2014).

Affordance

The concept of affordances (Gibson 1979) highlights that opportunities inherent in the physical environment, or affordances, can be perceived by people, thereby inviting and supporting people’s activities, or preventing them if the opportunities are absent. Besides, Kyttä (2003) further developed affordance into various categories (potential, perceived, used, and shaped affordance), highlighting that people can actively shape their environment to create new affordances, or to change existing ones. To proactively create and design affordances of the environment can be regarded as an effort to regulate the person-environment fit (Kyttä et al. 2004). It is also the relationship between the feature of an environment and the perceiver’s ability that determines how the environment’s affordance is perceived (Chemero 2018). In the case of humans, affordances not only include the action opportunities provided by the material environment but are also shaped by sociocultural practices, which vary across different forms of life and are reflected in the ways people engage in activities within their communities (Rietveld and Kiverstein 2014). They further state that the world can sometimes motivate people to act in certain ways, because we are solicited by the specific possibilities for action in our situation. Their arguments link with Costall’s (1995) viewpoint that the concept of affordance proposed by Gibson should be socialised. Social affordances are possibilities for social interactions or actions that are shaped by social practices (de Carvalho 2020), and the possibility that people can offer new affordances to one another.

As this study aims to explore how older people perceive and adapt to their neighbourhood environment to age-in-place, it is important to provide a more integrated understanding of the ageing process and the environment (Fig. 1). Based on this, we will investigate how older people’s capabilities, and the external environment influence their outdoor activities and experiences of ageing-in-place, as well as what efforts they have made to achieve the P-E fit.

Research significance

Ageing can be clearly understood based on certain physical, sociocultural and temporal factors (Chapman 2009). Research on ageing-in-place has concentrated on its correlation with place, social networks, support, technology and personal traits, with a call for additional investigation into its connection with informal social networks within communities (Pani-Harreman et al. 2021). The complexity of residential decisions, and how the out-of-home spaces is variously used are the directions to be further explored in conceptual and empirical terms (Wahl et al. 2012). Current explorations into ageing-in-place in China mainly focus on community care services (Zhou and Walker 2021) and older people’s needs (Cao et al. 2014). Further research is needed to explore ageing in different residential communities, and to understand how older people use their neighbourhood outdoor space to achieve P-E fit and understand the affordances of a place. This study aims to fill these gaps by addressing the following questions:

-

1.

What are the multiple factors influencing older people’s experiences of ageing in work-unit and commodity communities?

-

2.

How do these factors impact their use of outdoor space?

-

3.

How do older people adapt to their neighbourhood environment while ageing-in-place?

Regarding the research context, the urban house ownership rate in China reached 89.3% in 2010 (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2011), comprising 11.2% old or traditional private housing, 38% commodity housing and 40.1% work-unit housing. The latter two forms represent the primary types of home ownership among China’s urban residents. Compared to traditional private housing, both have clearly defined community boundaries, and therefore they are the focus of this study. However, these two types of residential communities are fundamentally different in terms of the residents and the outdoor space. Work-unit residential communities were originally owned by the public-sector institutions and enterprises, provided for employees to reside in as a fundamental welfare; they were sold to existing tenants or employees during the housing reform in the 1990s (Wang and Murie 1996; Wang 1995). They have very limited outdoor space for walking and recreation (Yan et al. 2014) but strong social cohesion in terms of the residents’ past experiences (Li et al. 2022a). Commodity housing residential communities are mainly young family communities (Li et al. 2022a), usually set within landscaped gardens (Li et al. 2012). The differences in outdoor spaces may result in differences in older people’s outdoor activities and social interactions. In the very limited amount of existing research on this, a study in Beijing found that the environmental challenges facing older people in the work-unit residential community are the lack of an elevator, sanitary issues, cleanliness in the stairways and lack of activity space. Older people with Beijing Hukou in commodity residential communities with more modern dwellings felt especially disconnected from others apart from their co-residing children (Yu and Rosenberg 2020). However, residents lacking official registration status (Hukou) are reported to have lower place attachment and less participation in civic engagement than those with official registration status (Wu et al. 2019).

Observational studies in China reveal that older adults are the main users of parks and community green spaces, comprising 53.5% (Tu et al. 2015) and 61.3% (Pleson et al. 2014) across all age groups. This is different from findings in Western countries, where older people are the minority users, such as in the US (Cohen et al. 2016; Park and Ewing 2017), Australia (Cranney et al. 2016; Levinger et al. 2023) and Belgium (van Dyck et al. 2013). Studies in Australia found that older people perceive shopping centres, civic places, cafes, restaurants and churches as third places that contribute to their social health (Alidoust et al. 2019). The dominance of older people in green space in China exemplifies best practice in ageing-in-place approaches in a global context. However, there is still a lack of understanding about barriers and facilitators that impact this ageing population’s participation in regular outdoor physical activity (Guo et al. 2016).

Research method

Semi-structured interviews were used to investigate older people’s perceptions and stories about using their neighbourhood’s outdoor space as this allowed the researcher to control the topics of the interview but still offered participants the opportunity to explore any issues they felt were important (Longhurst 2003; Ayres 2008). The purposive category of participants was people aged 60 and over, which is the current legal definition of older people in China, considering the heterogeneity in age, gender, mobility level and household composition. The research site selection criteria included location within districts with the highest ageing population rates in the central urban areas, the presence of sufficient potential participants, contrasting environmental conditions and access for researchers. Based on these criteria, the study recruited participants from a work-unit community and a commodity residential community in Beijing (Figs. 2 and 3). The recruitment of participants followed purposeful random sampling and snowballing strategies. A few potential participants refused to participate in this study due to time constraints or lack of interest in the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the [removed for peer review]. Prior to the interviews, all the participants were provided with an information sheet, the reason for the study was explained to them, they were given the opportunity to ask questions and asked for their consent to participate in the study.

The interviews were conducted in the communal outdoor space in the residential communities, where participants felt comfortable. The first author conducted 21 interviews on an old work-unit residential community, and 22 interviews on a commodity residential community. Table 1 provides more information about the interview participants. The interviews started with a set of grounding questions designed to obtain information about the participants’ personal circumstances, including their gender, age, living arrangements, length of time at their current residence, mobility situation, and mode of commuting daily. They then moved on to address substantive issues with questions designed to elicit the participants’ thoughts and experiences in relation to outdoor space in their neighbourhood and their experiences of ageing-in-place. During the interview, the researcher avoided guiding the respondents to give biased answers to ensure the fairness of the data.

All the participant data was anonymised with a reference number (e.g., C1_1_M_90: the first participant in the work-unit residential community, male, aged 90) and imported into NVivo 15 software for analysis. A thematic analysis approach was used to identify, analyse and report themes within the data, and describe the data in detail (Braun and Clarke 2006). The analysis process followed the phases outlined and applied by Braun and Clarke (2006) and Neville et al. (2021), which include familiarisation with the dataset, generating initial codes, collating codes into themes, reviewing and refining themes, defining and naming themes and producing the report. This study identified 127 nodes, which were refined into three main themes – personal situation, social environment, and physical environment – and nine sub-themes (Fig. 4).

Results

Three themes emerged from the analysis highlighting personal circumstances, the social environment, and the importance of the physical environment. The first theme, ‘personal situation’, with the sub-themes ‘maintaining health as a driving force’, ‘financial considerations’, and ‘placing hopes in community care’, portrayed participants’ concerns about health issues and ageing-in-place. The second theme, ‘social environment’, with the sub-themes ‘diverse family contact’ and ‘neighbourhood connections’, captured the approaches applied by older people’s family members and neighbours to facilitate or inhibit their range of outdoor activities and social participation. The third theme, ‘physical environment’, contains the sub-themes ‘satisfaction and attachment to the natural environment’ and ‘community retrofitting as an opportunity’. This theme reflects the importance of physical environment, especially natural elements like plants, in fostering older people’s sense of attachment, and highlights barriers to older people’s participation in community retrofitting. These three themes will be presented in this section. The integration of these themes, which reflect how older people adapt to their neighbourhood physical and social environment to achieve a better fit while ageing-in-place, will be discussed in Section 4.1.

Personal situation

This section discusses the reasons older adults go outdoors, the changes in the range of places they visit, their financial concerns, and their expectations of community care regarding ageing-in-place.

Maintaining health as a driving force

In both communities, the majority of older adults expressed a strong desire to age-in-place, prioritising their own and their partner’s ability to maintain good health, independence and mobility. Many respondents noted that they wished to avoid being a burden on their children due to their health issues. Older people’s strong desire to maintain health and mobility serves as a driving force for them to go outdoors and exercise. With their lengthening list of health problems and declining mobility, the participants habitually changed the outdoor spaces they visited. Participants in good health and with good mobility usually go to more distant places, for example, to a city-level park by bus, while those experiencing health and mobility problems usually walk in the local area, within their residential community. In the work-unit community, older people with limited mobility may be unable to go out as often as they wish because their residential building does not have a lift. An example of these changes was noted by one participant:

I’m not going to the Summer Palace and the Old Summer Palace anymore. I used to go there two years ago. Sometimes with my partner, sometimes with other neighbours, I just went there by bus. But not now […] I cannot walk for a distance. [C1_6_M_73]

Financial considerations

Financial situation was also a significant factor influencing participants’ choice of outdoor space and ageing-in-place. Some participants cared about daily living costs; for example, they used to take public transport to the parks because it was free for them to ride the bus and to enter the parks that charged admission fees, and they may also choose to go out in order to save on takeaway costs. The mismatch between older people’s expectations of the care home and their financial status or the charges applied by care homes also meant that they had to make the choice to age-in-place.

The care homes now are very expensive, require many deposits; we cannot afford it. Those cheap care homes, it is like waiting for death, very lonely and lifeless. Some people went there for just one month and came back. They cannot bear that environment. Staying at home is better. [C1_20_F_75]

Placing hopes in community care

Participants in the commodity residential community mostly co-reside or live near with their adult children, while participants in the work-unit community noted more financial considerations and a greater need for accessible and affordable community care. They rely more on the community care services that can support their independence and the choice to age-in-place, especially for older people who lack support from their family members. One participant noted:

I’m not moving, especially at this age. I choose ageing-in-place and don’t plan to go to the care home. Ageing-in-place is a nice choice. Now the community care services are about to start. They have not actually started their work yet. I think things will get better after they start to provide services. [C1_15_F_87]

Overall, older adults place great importance on their health, expressing a strong desire to age-in-place in good health to avoid burdening their children or facing the costs associated with nursing homes. They also express hopes for further improvements in community care services. However, an inevitable decline in mobility significantly alters the scope of their outdoor activities.

Social environment

This section includes two sub-themes that describe the impact of family members and neighbours on older people’s social lives and outdoor activities, highlighting key social factors that shape their ageing experience.

Diverse family contact

Different living arrangements determine whether older people have close contact with their family members and, therefore, influence the arrangement of their daily lives. Parent-child relationships dominate Chinese family relationships across different generations. Children providing care for their parents is a traditional behaviour that represents filial piety in Chinese culture (Yeh 2003). Several participants mentioned not wanting to live with their children due to lifestyle differences and generational gap. However, those who do live with their children benefit from daily support and companionship, which helps them maintain social connections and facilitates outdoor activities. As one participant said, with the help of her children, she could go to a distant park to watch other people’s activities, which is an important thing in her life:

My son takes me to walk around, listen to people singing the song and Beijing opera. I like sitting there to listen to opera. My son will walk around. He will take me to listen to the other group of people singing the opera until everyone leaves. [C1_21_F_95]

However, in the case that participants move to their children’s home to receive care or take care of their grandchildren, even though they are still living in the residential communities, they are uprooted from their own social networks. This phenomenon is more common in the commodity community. In this case, older people can be in danger of isolation, especially lost support from their partner. One participant who lost her partner a few years ago and wanted to return to the community where she used to live, said:

So I still have this idea now, but I can’t make it happen. I just want to go back to the residential community where I worked. It’s not much different from the residential community here, because it’s a gated community where everyone is from the same company, and we all know each other. We used to have things to talk about together. [C2_9_F_80]

Partners and spouses also play an important role in daily living, offering emotional support and companionship to each other. They build their lives and habits together through years of shared experiences. Numerous participants said they got used to going outdoors with the companionship of their partner. However, this companionship may end if their partner experienced health problems, which results in a reduction in their own activities and social interactions and could lead to social isolation. One participant stated:

It was about 10 years ago, my partner was still alive. We went to Longtan Park every day. There are many activities. We exercised together […] I could walk at that time. But my partner passed away afterwards. I do not have interests and motivations by myself. They have partners to go with. I really admire those old partners. It is two people anyway. [C2_9_F_80]

Many participants who reside with their children and grandchildren help to supervise their grandchildren and the majority of their daily lives are grandchildren-centred. They spend most of their time doing housework, cooking, taking grandchildren to and from school, and so on. A majority of participants stated that taking care of grandchildren occupied their leisure and rest time. Consequently, they do not have time to do their own activities or to go somewhere else, which could in turn influence their wider social connections. One participant who mentioned childcare duties when asked about their daily outdoor activities, said:

I do not have many activities now. She [the participant’s grandchild] is young and pretty troublesome […] I used to go to parks very often, every week, any time as I wanted. But now I go out much less since I have a grandchild. [C1_9_F_75]

After the end of their childcare duties, they might feel exhausted and lose the motivation to do more outdoor activities. In contrast, others who maintain greater mobility tend to be more active compared to the period in which they took care of grandchildren and they can resume their range of activities. One participant noted:

I just strolled around the residential community when my grandchild was young. Now I’m not strolling here [within the residential community]. I usually play table tennis in Long Tan park [a large city-level park]. [C2_17_F_67]

Older people who lack connection or interaction with their family members, for example, children or partners, tend to have greater social needs from their neighbourhood. In contrast, older people may use the outdoor space and build their social networks outside their communities more actively with companionship from their children or partners.

Neighbourhood connections

It was commonly understood amongst interviewees in the work-unit community that close relationships with neighbours are reciprocal and mutually supportive. The close relationships between neighbours even became a motivation for them to go out more frequently. One participant highlighted the following:

Here is like a small home anyway. It is nice to have many friends. You will not be happy if you do not have many friends […] This is the environment that I am familiar with. I have lots of friends and know many neighbours. We have good relationships […] It is nice to meet with each other. It is delightful to go out because I know lots of people. Sometimes I can meet with someone when I go out and then we can walk together and have some communications with each other. It simply makes me feel happy. [C1_20_F_75]

The need for social connections was also echoed by another participant who stated that she wants to move back to her previous work-unit residential community. She shared that she used to watch movies with her neighbours at the so-called ‘big pitch’ in their residential community. This showcases how the physical environment provides a social bond. Older people’s acquaintances within the residential community and in their neighbourhood also play a role in satisfying older people’s social needs. Close relationships with acquaintances facilitate older people’s use of outdoor space, and in turn emphasise the importance of social profiles in a place. One example is the dance group that was spontaneously organised within the work-unit community and engaged in daily dance and chorus practice in the community’s green space. Below, a participant shares how the group is self-managed and how attachments are formed between members:

This dancing group is organised by ourselves, there are no community committees in charge of us, no. Someone who is responsible for taking the stereo is also quite hard, and every year we pay 20 yuan [RMB] per person to buy the tapes and machines and so on. In the Chinese New Year we sometimes have a gala […] There is a group of people [dancing] in the evening, and we are the group [dancing] in the morning […] There was an old lady who couldn’t walk long distances anymore, and she still came over, and she said ‘I miss you guys if I don’t come for a day’. [C1_16_F_76]

A small number of participants in the commodity community reported being familiar with neighbours, either through a decade of living there or while they also care for their grandchildren. Most participants in the commodity community exhibited a relatively distant relationship with their neighbours because they have quite different backgrounds compared with residents from work-unit communities who used to work together. It is worth noting that participants in both communities also reported poor relationships with their new neighbours because they were not acquainted with some of the new residents or rental households; they regarded themselves as ‘older Beijingers’, and the new residents as the ‘new Beijingers’ or ‘outsiders’. This increasing number of new households and departure of longstanding neighbours as a result of urbanisation often results in older people in the residential community feeling unfamiliar with the surrounding social environment. Some participants explained that the reason they do not go to the small green space close to their community is because they do not know or are unfamiliar with the people who frequently use that space. People’s decisions about whether or not to use a space are influenced by who else is using it. This reflects the importance of social relationships in mediating people’s choice of space to visit.

As well as the informal social support from family members and neighbours, another theme emphasised by participants was the opportunity to participate in community matters. This theme particularly emerged from the work-unit community as its retrofitting was about to start whilst the interviews were being conducted. Participants expressed concerns about how their community would be changed, and made suggestions regarding the community retrofitting. Formalised engagement could therefore provide opportunities for older people to feel included as well as generating a sense of attachment to the community. However, it seems that there were some difficulties with the retrofitting process, as many of the participants reported that their voices were not heard. For example, one interviewee said:

When I saw this news last year, I started to prepare the suggestions. I sent my suggestions letter immediately when they started the retrofitting. It is my own suggestions. I sent a copy to the community secretary and a copy to the community director. No response. Nobody replied to me. [C1_3_M_87]

As people age, their social networks tend to shrink to the neighbourhood level or even to within the community. Even though one of the community committee members in the work-unit community said they had been organising activities in different seasons, using different themes according to different holidays, many participants still expressed their need for community-based activities. The reason for this might be because the activities they need are more regular activities where they can establish habits and build mutual relationships between neighbours. This is also reflected in the commodity community, as highlighted by one participant:

The community does not have many activities. Residents can enhance their social interactions with neighbours if there are many activities in the community. It seems that we do not have many interactions now. [C2_6_F_65]

This section reflects the changing social lives that older individuals experience as they navigate different roles, including those of parent, partner, grandparent and longstanding neighbour. Disruptions in social relationships may heighten the risk of social isolation for older adults. It is incumbent upon community committees to support older individuals in maintaining and fostering social connections.

Physical environment

This section discusses the differences in older individuals’ satisfaction with their communities’ physical environment and how they develop attachment through planting and maintaining greenery within the community. It also highlights the potential for community retrofitting to support ageing-in-place for older adults.

Satisfaction and attachment to the natural environment

Many participants in the work-unit community reported lower satisfaction with the environment and property management within their community but greater satisfaction with the environment outside their community; for example, other nearby residential communities and outdoor spaces. This is reflected in older people preferring to go to other places outside their community for activity, as one participant explained:

It is very organised here. The plants are all pruned. I will sit in the pavilion for rest when I get tired of strolling […] It is nice here, looks structured. It is not like our community, it is messing up everywhere. I usually stroll here when I feel bored in our community. [C1_6_M_73]

On the other hand, participants in the commodity residential community were more satisfied with their community environment. This satisfaction brings them pleasure and also encourages them to have contact with the natural elements and activities outside the home. One participant proudly described their community as a park:

The environment of this community is quite nice. It is like a park. The trees, plants, and ground cover are all green. There are few communities nearby that have large spaces like our community. The community over there does not have green space or space for activity. [C2_3_F_82]

Older people’s mobility, social interactions and emotions were promoted through both looking at the natural elements, and participatory activities with natural elements (planting and taking care of plants) in their residential communities. Their environment-related activities and strong sense of attachment was developed through their voluntary repetitive care for these natural elements. Below is a statement by a participant about older people taking care of plants together with a neighbour:

In the past few years, we [the participant and his neighbour in the work-unit community] even went to weed the peonies, feeling that it was less desolate that way. The peonies in the front yard were originally salvaged from a flowerpot I found in the garbage dump, and they were already withered. After bringing them back, I propagated them, and they have thrived for over a decade now. Everyone treats this place [the front yard of the residential building] as their own home with sincerity and dedication. [C1_6_M_73]

The attachment to plants exhibited by these voluntary planting and nurturing experiences in communities sometimes also involves developing social relationships with neighbours, therefore promoting attachment to communities. At the time the work-unit community was built, the majority of plants were planted by residents. Some neighbours who have grown and looked after plants together over the years to improve and maintain their community environment have formed a kind of bond, which is vital in promoting people’s attachment to the community. A similar theme was also identified in the commodity residential community as the residents are usually unacquainted with each other; when some older people move in, they might choose to grow plants to help them adapt to the new environment. As one participant said:

We grew three trees before, but the property management removed them. This [an orchard within the green space in the community] was grown by us, another two over there, and a pomegranate tree. We have grown them since we moved to live here. [C2_12_F_75]

In both communities, older people were observed making efforts in changing the physical features of their community to enable them and their neighbour to sit and chat together, presenting their perceived control of the community environment to enable the activities that contribute to their social life. Figure 5 showcases the plant pots on the platform, the blossom and the plants that older people planted on the grounds in the work-unit community.

Although the act of older residents planting in community communal areas is perceived as beneficial for them, this behaviour is increasingly hindered by community committees or property management as the level of management increases. This conflict became particularly pronounced with the age-friendly retrofitting of the work-unit that was initiated by the community; one participant expressed his disappointment:

They threw away my peonies when they [the community committee] started the community retrofitting. I felt heartbroken. Because I have feelings about them [the peonies]. I still think about how to take care of them even though I almost cannot move. [S1_1_M_90]

Although older individuals in commodity communities exhibit greater satisfaction with their community environment, those in work-unit communities then develop a stronger attachment to their community through collective activities, such as gardening. However, such activities face challenges amidst the current wave of renovations in older communities across China.

Community retrofitting as an opportunity

Older people’s ability to accept change in their environment usually decreases as they age. Therefore, they tend to keep things and environments unchanged. As a member of the work-unit community committee said, one very old resident who is over 90 years old requires the stairs in front of his residential building entrance to be retained rather than changed to a ramp, because he is used to taking the stairs. Some participants expressed nostalgia when talking about community retrofitting, which could also reflect their attachment to the community. The comment below illustrates older people’s fear of breaking the existing balance between their abilities and the environment.

I feel uneasy, I do not know how they will retrofit again. [C1_6_M_73]

However, expectations regarding the retrofitting were also expressed because of dissatisfaction with the existing environment. Concerns regarding how the community retrofitting would be conducted were widespread because it was directly relevant to their ageing-in-place experiences. Nonetheless, it seems that there were certain communication issues between older people and the community committee during the retrofitting planning stage, as mentioned in Section 3.2.2 noting that older people wish to participate in community matters. Older people themselves know what they want from retrofitting their residential community, and their voice being heard is thus key to ensuring they have a sense of control over the environment and participate in community matters. Thus, the retrofitting results could be more age-friendly and support older people to accept the environmental changes and maintain their ‘fit’ with the environment.

Discussion

This discussion section provides an integrated analysis of the themes outlined above, with a new understanding of ageing-in-place through the use of outdoor spaces and addressing the third research question. It also highlights the differences in ageing-in-place between the two community types, and the importance of older adults being involved in the retrofitting process, responding to the first and second research questions. Finally, the differences in ageing-in-place in China and other countries are also discussed.

Understanding of ageing-in-place through the use of neighbourhood outdoor spaces

The results explored how older people’s ageing-in-place experience is influenced by a complex interaction between their personal situation, social relationships and their local neighbourhood outdoor spaces.

Although older people regard outdoor activities as a way to maintain health, their engagement in such activities is influenced by the fit among their abilities, the neighbourhood physical environment, and their social networks. In the interviews, older people indicated the various ways they use outdoor spaces. Some use them less frequently and in a smaller range due to their own or their partner’s mobility and health issues, as well as childcare duties, while others use them more extensively and in a larger range due to good mobility and health, or because they have companionship from family members or neighbours. Longitudinal research in Europe found that grandchild care has health benefits and suggest the importance of the widely provision of grandparental childcare in Europe (Di Gessa et al. 2016). It cannot be denied that childcare responsibilities stimulated older people’s level of activity (Liu et al. 2020). But our findings elaborate that some older people are deprived of their time and activities in the process, losing the opportunity to visit distant neighbourhood green space or engage in wider social connections. Research in Canada observed that participants modified the physical environment to solicit social interaction (Hand et al. 2020). In order to achieve a better P-E fit, older people in this study also making efforts to change the physical environment to enable them to meet and socialise. In addition, they make efforts over the years to maintain and improve their community environment and they perceive the community’s shared areas as ‘home’. As a physical setting for shared use by residents, the communal areas can render the experience meaningful and memorable, contributing indirectly to place attachment (Zhu and Fu 2017).

Social-related activity enables older people establish and socialise with their networks, which in turn support them to be more physically and socially active while they age-in-place. They can build relationships of mutual companionship by going outdoors together and living more actively. However, their outdoor behaviours may be inhibited due to a lack of social-related affordance. This study explains that they may experience a lack of companionship or feel unfamiliar with others using the space, leading them to decide not to go out. In contrast, some older people adapt to their neighbourhood social affordance more proactively by building the social interaction in the neighbourhood. For example, they may carry out regular activities that attract others to observe and become immersed, or different groups of older people may establish the order of different activities that are carried out in one area. The opportunities they create for social interaction provide them with a sense of control about how to use the place, as well as developing a sense of attachment and belonging to a group of people. This arguably exemplifies the concept of social affordances, which refers to the opportunities for social interaction shaped by collective social practices (de Carvalho 2020).

Another aspect of social-related activity involves active engagement in community affairs, as exemplified in this study by empowering older individuals to assume their civic roles and voice their concerns and suggestions regarding community retrofitting. This also reflects their attempts to maintain the environment they are accustomed to. While the conversion of steps into accessible ramps is viewed as a necessary way to make the environment more age-friendly, some older people in the residential community vehemently advocate for the preservation of entrance steps, as they are accustomed to them. The results in this study underscore the critical importance of involving older individuals in the retrofitting process, as their insights and desires for the transformation of their residential community are essential to ensuring that the retrofitting outcomes align with age-friendly principles. As mentioned in Section 3.3.2, despite the constraints on their participation, certain older community members in this study demonstrate a robust sense of empowerment when it comes to engaging with community matters, echoing previous research indicating that the built environment serves as an indirect affordance for participation (Torres-Antonini 2001; Zhu and Fu 2017).

Ageing in work-unit and commodity communities

It is clear that older people in both communities wish to age-in-place rather than move to a care home. This article has provided insights into similarities and differences in ageing in these two communities.

It is surprising that Zhou and Walker (2021) found in China that community care services did not significantly impact on older people’s preference for ageing-in-place. However, the rationale behind this is that community care in China is too limited and the existing places are not meeting older people’s needs. This is echoed in this study as participants in the work-unit community expected to receive community care services to improve their ageing-in-place experiences at reasonable prices. Older adults either have limited financial capacity or limited expectations regarding how much they are willing to pay for care homes. As a result, they often find care homes to either be unsatisfactory or unaffordable in terms of environments and services, which increases their reliance on community care services. In contrast, participants in the commodity community live with or close to their adult children and rely more on their families to support them to age-in-place.

Relationships with neighbours, especially perceived support are important for older people (Greenfield and Reyes 2015). Neighbourhood social interactions, such as frequently engaging in physical activities with friends, enhance older people’s likelihood of meeting the recommended levels of weekly physical activity (Chaudhury et al. 2016). The housing policy in China that combined work and housing before the housing reform period in the 1990s established unique neighbour relationships; for example, the strong social ties between older neighbours can moderate the negative impact of residing in disadvantaged communities (Miao et al. 2019). In this study, older people and their longstanding neighbours in the work-unit community have developed strong connections, such as neighbours acting as a facilitator to encourage older people going outdoors to be physically and socially active. However, longstanding neighbours leaving and being replaced by new neighbours put older people residing in the work-unit community at risk of social isolation. This echoes previous research in Beijing that focused on older people with Beijing Hukou and found that those living in work-unit communities are rooted in their immediate neighbourhood, and their ability to maintain familiarity with the social environment has been weakened due to the transient nature of the residents (Yu and Rosenberg 2020). Evidence in Shanghai found that the segregation level between local and migrant older people increased from 2000-2010, with the highest wellbeing inequality and intensification of segregation in high-priced commodity communities (Liu et al. 2015). In this study, some older residents in the commodity community were moving from their own home to reside with or near their children in order to receive care from their children or care for their grandchildren. As migrants, they may experience more difficulties in establishing connections with their neighbours. An article found that older people in China migrating with adult children reported feelings of rootlessness, loneliness, lack of attachment to the community, family and neighbourhood relationships, and poor self-acceptance (Wang and Lai 2022). Even though participants in the commodity community described their community outdoor space as the park, they still depend on the community committee for permission to utilise the space for activities that are crucial to enable them to build networks with neighbours.

Older people’s participation in age-friendly community retrofitting

International studies have shown that older people can play active roles in urban improvement processes (Lager et al. 2013; Hand et al. 2020), and implementing an age-friendly approach in the process requires their close engagement (Buffel et al. 2012; Buffel and Phillipson 2016). This finding aligns with the present study, which emphasises the importance of recognising older adults’ abilities in enhancing their residential communities within China’s age-friendly retrofitting initiatives, as a foundation for broader urban engagement.

Empowering older people’s role in the redesign of an age-friendly city for themselves through participation and co-production is considered a vital dimension of age-friendly practice (Handler 2018). Previous research in urban China also highlights that understanding older people’s need to renovate their current accommodations to be more age-friendly is one of the key challenges in promoting age-friendly communities (Xiang et al. 2021). This study revealed the practical conflicts in the age-friendly retrofitting process: that removing plants grown by older people without asking fails to value their attachment to the community. Similarly, retrofitting in a community environment that older people are familiar with can cause anxiety as they may not be sure what changes will be made or whether they can manage the changes. Desirable outdoor environments and housing, social participation and community services comprise older people’s main requirements for an age-friendly community in China (Li et al. 2022b). Considering the general physical environment challenges in work-unit communities, such as the limited outdoor space for walking and recreation (Yan et al. 2014), older people should be involved in the retrofitting process and able to make their voices heard to protect their needs, and to prepare them for changes during community retrofitting.

Ageing-in-place in China and other countries

In this study, neighbourhood and municipal parks and communal outdoor space in communities were favoured by older people in both types of communities for outdoor activity to keep healthy and maintain social networks. This side-steps the fact that in China, older people are the main group using the parks and community green spaces (Pleson et al. 2014; Tu et al. 2015). This is different from older people in The Netherlands, who continued participating in activities at the local community centre, and attending coffee mornings held in a church adjacent to the square and in care homes to cope with future declines in mobility and health (Lager et al. 2015). Additionally, coffee shops and fast-food restaurants are popular neighbourhood destinations for older people in Minneapolis metropolitan area (Finlay et al. 2020). Unlike the context of New Zealand, where many people’s homes are set within large gardens, providing opportunities for gardening activities (Freeman et al. 2019), residential communities in urban China are often gated with dense residential buildings due to highly concentrated populations and limited land resources (Wang et al. 2018). It was gratifying to find in this study that older people in the work-unit community are able to find nature connection opportunities in the limited communal space to develop attachment to their community via gardening activities. These differences between China and Western countries mentioned above highlight the unique value of neighbourhood parks and communal outdoor space in the communities in support older people ageing-in-place in China. Other studies found that a communal garden is an underused resource for addressing care home residents’ isolation issues (Freeman et al. 2019; Fielder et al. 2021). This study interprets that there is a need to protect older people’s ability and opportunities to directly engage with nature in residential communities, as gardening is not only a casual leisure activity, but also beneficial for physical and psychological wellbeing (Scott et al. 2015). Older people’s efforts to engage with nature have been obstructed by the increasing management by the community committees, removing their plants and restricting their planting activities. Together with the limited activity space within the community, they fulfilled more needs and achieved greater satisfaction with nearby activity space. Similar to a previous study in China, older people residing in older communities showcased higher demands for the access outdoor spaces than those in newer communities, and a stronger need for community public facilities to be retrofitted (Li et al. 2022b).

In a study examining long-term care patterns across 29 European countries, Nordic and Western European nations demonstrate a strong state responsibility for providing formal care, whereas Mediterranean and Central-South Eastern countries rely primarily on families for informal care (Damiani et al. 2011). Due to the filial piety culture, Chinese older people prefer to age-in-place. However, reliance on elder care support and services from non-family members has become inevitable as a result of the one-child policy (Song et al. 2018). Participants in this study, particularly those residing in work-unit communities or lacking sufficient care from their children, view community-based care services as a preferred option for aging-in-place. The Chinese government has been working to expand the capacity of community-based formal care. However, such services remain underdeveloped, with issues of low-quality provision and inadequate monitoring of standards (Hu 2019; Wong and Leung 2012). More critically, there is a shortage of professionally trained staff, including nurses, social workers, and personal care workers (Wong and Leung 2012). As aforementioned, the conflicts between the community committee and the older residents during the community retrofitting process, underscore the need for community committee to deepen its understanding of the biological, social, and psychological aspects of ageing, as well as to improve communication skills with older people. Future community workers and service providers require enhanced training, as emphasized by Black (2008), who advocates for the integration of respect for autonomy into all service and program objectives.

Conclusion and implications

This study aims to advance the understanding of how to support older people who reside in work-unit and commodity residential communities in Beijing to age-in-place. Using the P-E fit and affordances theories as the foundation, this study examined the extent to which the affordances provided by the neighbourhood influence the fit between older people and neighbourhood they reside in. Older people in this study demonstrated how they integrate their abilities with their neighbourhood’s physical and social environment to achieve a better P-E fit, which is the key to enabling age-in-place. This study also explored the differences in ageing within these two types of communities, and justified the importance of older people’s participation in age-friendly retrofitting processes. These findings contribute a new perspective to studies on older people’s ageing in their communities, future ageing-in-place policies, and age-friendly environment development.

China is now actively improving its older people’s service system. Taking Beijing as an example, the Implementation Opinions on Improving Beijing’s Elderly Service System (General Office of the Beijing Municipal People’s Government 2023) proposes establishing street-level service centres for older people. These centres would offer amenities such as community canteens, senior learning centres, and recreational and entertainment facilities. This study demonstrated that older people’s expectations of community care services are not being met, especially for older people who reside in the work-unit community and who rely more on community care. Community committee staff and community care service providers need more training and a deeper understanding of the social challenges older people face to enhance service quality. This includes those in work-unit communities who may be separated from longtime neighbours, as well as those moving to commodity communities to care for grandchildren or receive support from their adult children, all of whom may risk social isolation. Although Choi (2022) argues that building age-friendly communities should prioritise the built environment rather than the social environment, a study in China highlights that in the process of residents making their community a home, communal space in communities are more important than social relationships (Zhu and Fu 2017). This study reinforces the importance of outdoor space to support older people’s fit with their communities and ageing-in-place, given their preference for using outdoor spaces for exercise to maintain health and social relationships. However, the continued improvement of outdoor spaces to be more age-friendly necessitates consideration of how older people use the space to enable their social connections, and how their social connections facilitate their use of the outdoor space. Neighbourhood outdoor spaces such as communal gardens and neighbourhood parks can be utilised by community committees to organise regular activities to support older people to build social connections.

The community age-friendly retrofitting wave in China is a vital and direct opportunity for older people to be able to participate in community matters and build their confidence in negotiating with their own needs and changing the community environment. These are keys to ensuring older people’s environment-related and social-related engagement to enable older people to age-in-place well. Beijing issued the Guidelines on the Comprehensive Improvement of Older Communities for the Implementation of Age-Friendly Retrofitting and Barrier-Free Environment Construction, which recommend creating suggesting building barrier-free public activity spaces, and utilising unused public space to install participatory and accessible planting areas (Beijing Municipal Commission of Housing and Urban-Rural Development 2021). This study argues that age-friendly retrofitting in old communities does not necessarily require extensive, large-scale renovations. As aforementioned, the need to support older people to age-in-place through community-based programs and neighbourhood outdoor space has significant potential to be utilised by community groups. We further suggest that the changes in the retrofitting process need to be small and involve older people’s participation to utilise and improve existing places and opportunities in residential communities for older people to plant and organise their meeting places, and utilise these spaces to organise community activities.

Limitations and future research

This study operated on a small scale, aiming to obtain in-depth insights into the perspectives of older people. Future research endeavours should extend to diverse urban settings and a broader array of community types. This study has identified differences in the use of outdoor spaces between older people with good mobility and those with limited mobility, as well as among older people with different household compositions. Future research with a larger sample size is needed to further validate these findings and explore the differences in space usage between older people who actively participate in social activities and those who are socially isolated. Older people who migrate to reside with their adult children are also a group that warrants special attention. During the data collection process, the work-unit community underwent age-friendly renovations, providing additional relevant content and helping reveal design issues. This study paves the way for understanding how older people perceive affordances and their efforts in achieving the fit between themselves and their neighbourhood environment to age-in-place. Future research should investigate how older people use neighbourhood outdoor space and age-friendly retrofitting in various community settings, with a specific focus on promoting the engagement of the older people and supporting the P-E fit in this process.

Data availability

Due to the ethically and politically sensitive nature of the research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly. Please contact the corresponding author to discuss the underlying data.

References

Ayres L (2008) ‘Semi-Structured Interview’, In: L Given (ed) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc, p 811-813

Beijing Municipal Commission of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (2021) Guidelines on the Comprehensive Improvement of Older Communities for the Implementation of Age-Friendly Retrofitting and Barrier-Free Environment Construction. https://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengcefagui/202105/W020210802576579852131.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2024

Black K (2008) Health and aging-in-place: Implications for community practice. J Community Pract 16(1):79–95

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Buffel T, Phillipson C (2016) Can global cities be ‘age-friendly cities’ ? Urban development and ageing populations. Cities 55:94–100

Buffel T, Phillipson C, Scharf T (2012) Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’ cities. Crit Soc policy 32(4):597–617

Cao MJ, Guo XL, Yu H et al. (2014) Chinese community‐dwelling elders’ needs: promoting ageing in place. Int Nurs Rev 61(3):327–335

Cao X, Hou SI (2022) Aging in community mechanism: Transforming communities to achieving person–environment fit across time. J Aging Environ 36(3):256–273

Chan ACM, Cao T (2015) Age-friendly neighbourhoods as civic participation: Implementation of an active ageing policy in Hong Kong. J Soc Work Pract 29(1):53–68

Chapman SA (2009) Ageing well: emplaced over time. Int J Sociol Soc policy 29(1/2):27–37

Chaudhury H, Campo M, Michael Y et al. (2016) Neighbourhood environment and physical activity in older adults. Soc Sci Med 149:104–113

Chemero A (2018) An outline of a theory of affordances. In: Jones K (ed) How Shall Affordances be Refined? Four Perspectives: a Special Issue of Ecological Psychology. Routledge, New York, p 185–191

Chen F, Liu G (2009) Population Aging in China. In: Uhlenberg P (ed) International Handbook of Population Aging. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, p 157–172

Chen L, Han WJ (2016) Shanghai: Front-runner of community-based eldercare in China. J aging Soc policy 28(4):292–307

Choi YJ (2022) Understanding aging in place: Home and community features, perceived age-friendliness of community, and intention toward aging in place. Gerontologist 62(1):46–55

Cranney L, Phongsavan P, Kariuki M et al. (2016) Impact of an outdoor gym on park users’ physical activity: A natural experiment. Health place 37:26–34

Cohen DA, Han B, Nagel CJ et al. (2016) The first national study of neighborhood parks: Implications for physical activity. Am J preventive Med 51(4):419–426

Costall A (1995) Socializing affordances. Theory Psychol 5(4):467–481

Cunningham C, O’Sullivan R, Caserotti P et al. (2020) Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta‐analyses. Scand J Med Sci sports 30(5):816–827

Damiani G, Farelli V, Anselmi A et al. (2011) Patterns of long term care in 29 European countries: evidence from an exploratory study. BMC Health Serv Res 11:1–9

Davey J, de Joux V, Nana G et al. (2004) Accommodation options for older people in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Centre for Housing Research Aotearoa/New Zealand. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=f42bb8e783c2795e7d0a54a203340bb9c169b8e7. Accessed 10 Nov 2024

Di Gessa G, Glaser K, Tinker A (2016) The impact of caring for grandchildren on the health of grandparents in Europe: A lifecourse approach. Soc Sci Med 152:166–175

de Carvalho E M (2020) Social Affordance. In Vonk J, Shackkelford T (ed) Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_1870-1. p 1–4

Dong K, Wang G (2014) China’s pension challenge: adaptive strategy for success. Public Adm Dev 34(4):265–280

Duggan S, Blackman T, Martyr A et al. (2008) The impact of early dementia on outdoor life: A ‘shrinking world’? Dementia 7(2):191–204

Enssle F, Kabisch N (2020) Urban green spaces for the social interaction, health and well-being of older people—An integrated view of urban ecosystem services and socio-environmental justice. Environ Sci policy 109:36–44

Esther YHK, Winky HKO, Edwin CHW (2017) Elderly satisfaction with planning and design of public parks in high density old districts: An ordered logit model. Landsc urban Plan 165:39–53

Fänge A, Oswald F, Clemson L (2012) Aging in Place in Late Life: Theory, Methodology, and Intervention. J Aging Res 2012:1–2

Fielder H, Marsh P (2021) I used to be a gardener’: connecting aged care residents to gardening and to each other through communal garden sites. Australas J Ageing 40(1):e29–e36

Finlay J, Esposito M, Tang S et al. (2020) Fast-food for thought: Retail food environments as resources for cognitive health and wellbeing among aging Americans? Health place 64:102379

Freeman C, Waters DL, Buttery Y et al. (2019) The impacts of ageing on connection to nature: The varied responses of older adults. Health place 56:24–33

General Office of the Beijing Municipal People’s Government (2023) Implementation Opinions on Improving Beijing’s Elderly Service System. https://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/gfxwj/202311/t20231101_3293045.html. Accessed 28 Feb 2024

Gibson JJ (1979) The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton, Mifflin and Company

Greenfield EA, Reyes L (2015) Continuity and change in relationships with neighbors: Implications for psychological well-being in middle and later life. J Gerontol Ser B: Psychological Sci Soc Sci 70(4):607–618

Guo Y, Shi H, Yu D et al. (2016) Health benefits of traditional Chinese sports and physical activity for older adults: a systematic review of evidence. J Sport Health Sci 5(3):270–280

Hand C, Rudman DL, Huot S et al. (2020) Enacting agency: exploring how older adults shape their neighbourhoods. Ageing Soc 40(3):565–583

Handler S (2018) Alternative age-friendly initiatives: redefining age-friendly design. In Buffel T, Handler S, Phillipson (ed) Age-Friendly Cities and Communities, Policy Press, Bristol, p 211–230

Hanson S (2010) Gender and mobility: new approaches for informing sustainability. Gend, Place Cult 17(1):5–23

Hu B (2019) Projecting future demand for informal care among older people in China: the road towards a sustainable long-term care system. Health Econ, Policy Law 14(1):61–81

Kim J, Kaplan R (2004) Physical and Psychological Factors in Sense of Community. Environ Behav 36(3):313–340

Kim K, Buckley T, Burnette D et al. (2022) Measurement indicators of age-friendly communities: Findings from the AARP age-friendly community survey. gerontologist 62(1):e17–e27

Kweon B, Sullivan W, Wiley A (1998) Green Common Spaces and the Social Integration of Inner-City Older Adults. Environ Behav 30(6):832–858

Kyttä M (2003) Children in outdoor contexts: affordances and independent mobility in the assessment of environmental child friendliness. Helsinki University of Technology

Kyttä M, Kaaja M, Horelli L (2004) An Internet-Based Design Game as a Mediator of Children’s Environmental Visions. Environ Behav 36(1):127–151

Jiang N, Lou VW, Lu N (2018) Does social capital influence preferences for aging in place? Evidence from urban China. Aging Ment health 22(3):405–411

Lager D, Van Hoven B, Huigen PP (2013) Dealing with change in old age: Negotiating working-class belonging in a neighbourhood in the process of urban renewal in the Netherlands. Geoforum 50:54–61

Lager D, Van Hoven B, Huigen PP (2015) Understanding older adults’ social capital in place: Obstacles to and opportunities for social contacts in the neighbourhood. Geoforum 59:87–97

Lawton MP, Nahemow L (1973) Ecology and the Aging Process. In: Eisdorfer C, Lawton MP ed The psychology of Adult Development and Aging. American Psychology Association, Washington, p 619–674

Lee H, Lee JA, Brar JS et al. (2014) Physical activity and depressive symptoms in older adults. Geriatr Nurs 35(1):37–41

Levinger P, Dreher BL, Dunn J, Garratt S et al. (2023) Parks Visitation, Physical Activity Engagement, and Older People’s Motivation for Visiting Local Parks. J Aging Phys Act 1(aop):1–10

Li J, Dai Y, Wang CC et al. (2022b) Assessment of environmental demands of age-friendly communities from perspectives of different residential groups: a case of Wuhan, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(15):9120

Li SM, Zhu Y, Li L (2012) Neighbourhood Type, Gatedness and Residential Experiences in Chinese Cities: A Study of Guangzhou. Urban Geogr 33(no.2):237–255

Li Y, Yu J, Gao X et al. (2022a) What does community‐embedded care mean to aging‐in‐place in China? A relational approach. Can Geographer/Le Géographe canadien 66(1):132–144

Liu Y, Dijst M, Geertman S (2015) Residential segregation and well-being inequality over time: A study on the local and migrant elderly people in Shanghai. Cities 49:1–13

Liu Z, Kemperman A, Timmermans H (2020) Social-ecological correlates of older adults’ outdoor activity patterns. J Transp Health 16:100840

Longhurst R (2003) Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Key methods Geogr 3(2):117–132

Lovell R, Husk K, Cooper C et al (2015) Understanding how environmental enhancement and conservation activities may benefit health and wellbeing: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 15(1):864

Lü J, Fu W, Liu Y (2016) Physical activity and cognitive function among older adults in China: a systematic review. J sport health Sci 5(3):287–296

Luoma-Halkola H, Häikiö L (2022) Independent living with mobility restrictions: older people’s perceptions of their out-of-home mobility. Ageing Soc 42(2):249–270

Miao J, Wu X, Sun X (2019) Neighborhood, social cohesion, and the Elderly’s depression in Shanghai. Soc Sci Med 229:134–143

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2011) The Ninth Report of the ‘Eleventh Five-Year Plan’ Series of Economic and Social Development Achievements. https://www.stats.gov.cn/zt_18555/ztfx/sywcj/202303/t20230301_1920369.html. Accessed 22 Mar 2024

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2021) Seventh National Census Bulletin (No. 5). https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/202302/t20230206_1902005.html. Accessed 28 Mar 2024

Neville S, Napier S, Adams J et al. (2021) Older people’s views about ageing well in a rural community. Ageing Soc 41(11):2540–2557

Oswald F, Wahl H W (2019) Physical contexts and behavioral aging. In Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology

Pani-Harreman KE, Bours GJ, Zander I et al. (2021) Definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’: a scoping review. Ageing Soc 41(9):2026–2059

Park K, Ewing R (2017) The usability of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for measuring park-based physical activity. Landsc Urban Plan 167:157–164

Pleson E, Nieuwendyk LM, Lee KK et al. (2014) Understanding older adults’ usage of community green spaces in Taipei, Taiwan. Int J Environ Res public health 11(2):1444–1464

Rantakokko M, Iwarsson S, Kauppinen M et al. (2010) Quality of life and barriers in the urban outdoor environment in old age. J Am Geriatrics Soc 58(11):2154–2159

Rietveld E, Kiverstein J (2014) A rich landscape of affordances. Ecol Psychol 26(4):325–352

Rowles G D, Bernard M (2013) The meaning and significance of place in old age. In: Rowles G D, Bernard M (ed) Environmental gerontology: Making meaningful places in old age. Springer Publishing Company, New York, p3–24

Scharf T, Keating N C (2012) Social exclusion in later life: a global challenge. In: Scharf T, Keating N C (ed) From exclusion to inclusion in old age: A global challenge. Policy Press, Bristol, p1–16

Scharlach AE (2017) Aging in context: Individual and environmental pathways to aging-friendly communities—The 2015 Matthew A. Pollack Award Lecture. Gerontologist 57(4):606–618

Schwanen T, Páez A(2010) The mobility of older people: an introduction. J Transport Geogr 18(5):591–595

Scott TL, Masser BM, Pachana NA (2015) Exploring the health and wellbeing benefits of gardening for older adults. Ageing Soc 35(10):2176–2200

Song, Sörensen Y, Yan S, E C (2018) Family support and preparation for future care needs among urban Chinese baby boomers. J Gerontology: Ser B 73(6):1066–1076

State Council of the People’s Republic of China (2019) Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Promoting the Development of Elderly Services. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-04/16/content_5383270.htm. Accessed 11 Mar 2024

Stjernborg, Emilsson V, U M, Ståhl A (2014) Changes in outdoor mobility when becoming alone in the household in old age. J Transp Health 1(1):9–16