Abstract

This study examines family quality of life (FQOL) in Saudi Arabian families with children who have disabilities, emphasizing the dual roles of giving and receiving social support, alongside economic factors. Prior literature highlights individual influences, including sociodemographic variables and types of disabilities, and identifies social support and resilience as significant contributors to FQOL. A cross-sectional survey was conducted with 200 family members of children with intellectual disability (n = 142) or other disabilities (n = 58). Five domains of FQOL were measured: family interaction, parenting, emotional well-being, physical/material well-being, and disability-related support. Multiple regression analyses revealed that both giving and receiving emotional and instrumental support were significant predictors of family interactions, with giving support showing strong associations. Additionally, maternal education level was linked to emotional well-being and disability-related support, while higher monthly income correlated with improved physical/material well-being. The findings suggest the importance of evaluating FQOL predictors across specific domains, revealing that both giving and receiving support—particularly emotional support—play crucial roles in strengthening family interactions and parenting. Moreover, economic stability and maternal education level are essential for emotional and material well-being within these families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The family is a complex social system of relationships and functions of individual members that interact and affect the needs of all its members (Ling et al., 2022; Summers et al., 2005). This means that it is important to meet the needs of all the family members, not just the needs of children with disabilities (McCarthy & Guerin, 2022). However, for children with disabilities, the family plays an important role (Samuel et al., 2012). Parents may be given more responsibilities for providing care to children with Intellectual Disability (ID) (Lunsky et al., 2017), who are more likely to develop psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety, and stress (Arzeen et al., 2020; Nam & Park, 2017; Sharma et al., 2021; Scherer et al., 2019). Thus, these negatives could simultaneously affect the quality of life (QOL) of individuals with disabilities and their families (Vernhet et al., 2022). However, the presence of a child with ID in the family may have some advantages, such as increased family unity, tolerance, and happiness (Beighton & Wills, 2019; Lakhani et al., 2013).

In past decades, researchers on ID had focused on family well-being, using a comprehensive approach for studying the well-being of children with ID and their families (Ferrer et al., 2017). In addition to understanding the impact of services and support provided to families (Ferrer et al., 2017; Park et al., 2003), and meeting their individual and family needs (Vanderkerken et al., 2019), assessment of Family Quality of Life (FQOL) is important for maintaining family functioning (Rillotta et al., 2012; Dizdarevic et al., 2022). The results of a scoping review by Alnahdi et al. (2022) indicated that FQOL is usually measured via environmental (proximal as well as distal) and economic factors. According to Summers et al. (2005), FQOL consists of five dimensions: family interaction, parenting, emotional well-being, physical/material well-being, and disability-related support.

FQOL studies on families with ID have examined the relationship between these dimensions and the characteristics of family members, such as socioeconomic variables, as well as the characteristics related to children with disabilities (Alnahdi et al., 2022; Ferrer et al., 2017). The impact of health and economic hardships have been identified as strong factors affecting family well-being (Olsson & Hwang, 2008). Household income was a predictor of household satisfaction with FQOL (Ferrer et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2012; Mas et al., 2016). Further, the family type—parents living together or one of the spouses having another partner—was identified as an important factor in the family’s satisfaction with FQOL (Giné et al., 2015; Mas et al., 2016). Higher parental educational levels have been associated with higher levels of FQOL (Vilaseca et al., 2017). Additionally, the type (Alnahdi & Schwab, 2024) and severity of the disability were important predictors of FQOL (Hu et al., 2012; Ferrer et al., 2017).

Providing support to families of children with disabilities is important for improving their FQOL (Meral et al., 2013; Md-Sidin et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2020). Luckasson (1992, p. 151) defines support as: “resources and strategies that aim to promote the development, education, interests, and personal well-being of a person, and that enhance individual functioning.” Several types of support (e.g., professional, social, emotional, and material/instrumental support) are associated with FQOL (Barmak et al., 2025; Cavkaytar et al., 2012; Dai et al., 2024; Hassanein et al., 2022; Feng et al., 2022; Meral et al., 2013; Rillotta et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2020).

Studies have demonstrated that social support has a high impact on FQOL (Hassanein et al., 2022; Lei & Kantor, 2022; Meral et al., 2013; Pozo et al., 2014). For instance, social support fosters the adaptation and stability of families of individuals with disabilities (Migerode et al., 2012), reduces parental stress (Schultz et al., 2022), and increases family members’ subjective well-being (Hamama et al., 2024). Social support is represented in two major cross-cutting dimensions of other types of support: emotional and instrumental support (Declercq et al., 2007; Semmer et al., 2008). While emotional support includes encouragement, upliftment, and friendship (Acoba, 2024; Shang & Fisher, 2014), instrumental support includes helping with household chores and providing material goods (Schultz et al., 2022). Emotional and instrumental support are derived from social networks (Md-Sidin et al., 2010). Families with strong social networks, through which, they receive support have a higher FQOL (Schlebusch et al., 2017; Jansen-van Vuuren et al., 2021). Clark et al. (2012) found a significant association between families’ access to support from others and the FQOL domains. Overall, there is no doubt that support from those close to the family, such as friends, relatives, neighbors, and families with disabled children, contributes to improving FQOL (Araújo et al., 2016; Bhopti et al., 2016).

Some studies indicate that in addition to social support, resilience could play a mediating role in the adaptation of families with disabilities (Norizan & Shamsuddin 2010; Migerode et al., 2012). Resilience is the maintenance of mental health despite negative traumatic events (Kalisch et al., 2015). It is an essential component of strength in transcending life’s difficulties and overcoming them (Egan et al., 2024; Rajan & John, 2017). The results of a meta-analysis conducted by Iacob et al. (2020) on the factors associated with resilience among family caregivers of children with developmental disabilities found that social support was the strongest factor associated with resilience. Likewise, Fereidouni et al. (2021) found higher resilience to be an important predictor of QOL in mothers of children with disabilities, which indicates that social support and resilience may be strongly associated with QOL. Savari et al., (2021) study confirmed the positive relationship between social support, resilience, and QOL in parents of children with disabilities. Families achieve greater resilience through parents’ positive perceptions of their children with disabilities, which arise from providing them with appropriate educational support and meeting their needs (Rajan & John, 2017).

Studies on the factors affecting the FQOL of families with ID in the Gulf region remain limited. Alnahdi & Schwab, (2024) confirmed that in line with previous literature, in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia too, monthly income, and type and severity of the disability are important predictors of FQOL for families, including a family member with ID. The study also showed that younger and less-educated mothers were more satisfied with their FQOL (Author, 2024). Altamimi (2012) found that social support provided to parents of children with disabilities was associated with FQOL. Furthermore, the results of a study conducted in Qatar on mothers of children with ID indicated that receiving/giving social support was an important predictor of mothers’ QOL, whereas resilience was not (Hassanein et al., 2021). Alwhaibi et al. (2020) concluded that mothers of children with disabilities require social and vocational support to improve their QOL.

Research question

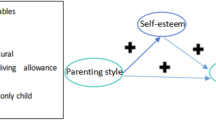

This study explores the variables that might be associated with the FQOL of Saudi Arabian families of children with disabilities. It investigates the association between receiving/giving social support (emotional and instrumental support) for families, and resilience association with FQOL, as hypothesized by previous studies (Fereidouni et al., 2021; Hassanein et al., 2021; Savari et al., 2021). It also examines the associations of variables hypothesized by previous literature as being related to the characteristics of the family (parents’ education, monthly income), and those of children with disabilities (type and severity of the disability) on FQOL (Ferrer et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2012; Mas et al., 2016; Vilaseca et al., 2017), with the difference in the sample in this study, and its inclusion of all family members. Overall, this study aims to provide deeper and more comprehensive insights into FQOL, and its associated variables within Saudi Arabia.

Methods

Procedure

Following the ethical approval, the Ministry of Education in Riyadh authorized the study and allowed its implementation across several public schools in Riyadh that included children with disabilities. The questionnaire was sent electronically via phone messages by school administrations to parents of children with disabilities. They were provided with the contact number of the “data collector,” who would answer their inquiries and questions, and assist participating families in answering the questionnaire. The introductory section of the questionnaire clearly articulated the study’s aims, the intended participant group, and underscored that participation was entirely voluntary. Informed consent was secured through the electronic questionnaire platform, with parents indicating their consent by actively choosing to proceed with and submit the completed questionnaire.

Participants

This study comprised 200 participants from families of children with disabilities: 142 families with ID and 58 with other disabilities (such as hearing, visual, physical, and multiple disabilities), in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. While most of the families included children with moderate or mild disabilities (41.5% and 38%, respectively), only 20.5% included children with severe disabilities. The majority were female participants, comprising mothers and sisters (32% and 27%, respectively). Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the demographic variables of the study participants. Each respondent represented a unique family unit; no two participants were from the same household, ensuring independence of observations. As regards the individuals with disabilities in the families, they were categorized into three age groups: children (6–14 years, 31.5%), youth (15–24 years, 65%), and adults (25 years and above, 3.5%). In terms of gender, 59% were female (n = 118) and 41% were male (n = 82). The severity of the disability was reported by the participating family member based on prior clinical or educational diagnoses they had received.

Instruments

FQOL scale

The FQOL scale developed by the Beach Disability Center (2005) was used to assess families’ satisfaction with their FQOL. It includes 25 items divided into five domains: family interaction—six items (e.g., “My family members talk openly with each other”), parenting - six items (e.g., “Family members help children to learn to be independent”), emotional well-being - four items (e.g., “My family has the support needed to relieve stress”), physical/material well-being—five items (e.g., “My family gets medical care when needed”) and disability-related support—four items (e.g., “My family member with special needs has support to make progress at home”). Items were answered using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

The Arabic version was used in this study (Alnahdi et al., 2021). Cronbach’s alpha for the general scale was .965, and for the subscales, it ranged from α = 0.854 to 0.946 (Alnahdi et al., 2021). In this study’s sample, a reliable internal consistency was achieved for the sub-scales ranging from α = 0.864 to 0.962 and ω = 0.880 to 0.962.

Social Support

The 2-Way Social Support Scale (2-Way SSS) was developed by Shakespeare-Finch and Obst (2011) to assess the benefits of giving and receiving emotional and instrumental support. It consists of 21 items distributed into four domains: receiving emotional support - seven items (e.g., “There is someone I can talk to about the pressures in my life”); giving emotional support—five items (e.g., “I am there to listen to others’ problems”); receiving instrumental support - four items (e.g., “If stranded somewhere, there is someone who would get me”); and giving instrumental support - five items (e.g., “I am a person others turn to for help with tasks”), which are answered on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (always). For all the subscales, the scale achieved internal reliability, which ranged from α = 0.81 to 0.92, and good validity (Shakespeare-Finch & Obst, 2011).

The Arabic version (Hassanein et al., 2022) showed acceptable fit indicators for structural validity and achieved acceptable consistency coefficients for all the subscales, ranging from 0.76 to 0.93. For this study’s sample, good reliability was achieved for the subscales, ranging from α = 0.910 to 0.967 and α = 0.910 to 0.967.

Resilience

The Brief Resilience Scale was developed by Smith et al. (2008). It is a 6-item self-report measure such as (“I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times” and “It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event”). This scale assesses resilience rather than recovery or resistance (Smith et al., 2008). Items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In Smith et al.’s (2008) study, the scale achieved good internal consistency on the four samples, which ranged from α = 0.80 to 0.91, and test-retest reliability on two samples: the first for a month, achieved 0.69 and the other for three months, achieved 0.62.

The Arabic version was validated by Hassanein et al. (2022). Reliability indicators were supported by Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.72). In this study’s sample, a reliable internal consistency was achieved (α = 0.810) and (ω = 0.800).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

As shown in Table 2, the participants rated their FQOL as rather high for all domains. The highest mean was for the FQOL subscale of families participating in family interactions (M = 4.37, SD = 1.05) and the lowest was for emotional well-being (M = 3.41, SD = 1.38). The 2-Way SSS was rated very high for all subscales. The highest and lowest means were in the giving and receiving instrumental support sub-scale (M = 4.44, SD = 0.96, and M = 4.18, SD = 1.18, respectively). Additionally, a high overall mean was obtained for the participants’ resilience (M = 3.82, SD = 1.02). Skewness and kurtosis indices were examined for all subscales. As expected for constructs such as social support and family quality of life, which are often positively perceived, several subscales exhibited moderate to strong negative skewness (e.g., Giving Emotional Support: skewness = −2.15) and elevated kurtosis (e.g., Giving Instrumental Support: kurtosis = 5.18). Nonetheless, all values remained within the acceptable range for regression analysis in large samples (i.e., skewness < |2| and kurtosis < |7|; West, Finch, & Curran, 1995). Given the sample size (N = 200) and the established robustness of multiple regression to moderate violations of normality, parametric analyses were deemed appropriate. Furthermore, diagnostic checks confirmed that the residuals met the assumptions of normality required for regression.

Multiple regression

In this part, we have used standard multiple regression rather than hierarchical regression because the study was exploratory and lacked a theoretical basis for ordering predictor blocks (Keith, 2019). We did start by treating all predictors equally allowed for unbiased estimation of their unique contributions, which aligns with best practices in exploratory research where suppressor effects and collinearity between variables (e.g., income and social support) may distort hierarchical models (Cohen et al., 2013; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013).

Five multiple regressions were separately run for each subscale of the five domains of FQOL to examine the10 hypothesized/potential predictors: type of disability (ID versus others), severity of disability (mild, moderate, severe), mothers and fathers’ education levels (not educated, less than high school, high school, bachelor’s, graduate studies), monthly income (5000−, 5000 to 10,000, 10,000+, 15,000+), receiving emotional support, giving emotional support, receiving instrumental support, giving instrumental support, and resilience.

As shown in Table 3, four variables—receiving emotional support, giving emotional support, receiving instrumental support, and giving instrumental support—were statistically significant predictors of family interactions. However, providing emotional and instrumental support was the strongest predictors, as evidenced by their higher partial correlation (0.19; 0.16) as compared with other variables.

Table 4 shows that two variables—giving emotional and instrumental support—were statistically significant predictors of parenting. Giving emotional support was the strongest predictor, as evidenced by its partial correlation (0.223) in comparison with giving instrumental support (0.172).

Table 5 shows that two variables—less educated mothers and receiving instrumental support—were statistically significant predictors of emotional well-being. Receiving instrumental support was the strongest predictor, as evidenced by its partial correlation (0.306) in comparison with mothers’ education (−0.016).

As shown in Table 6, three variables—monthly income, giving instrumental support, and receiving instrumental support—were statistically significant predictors of physical and material wellbeing. Receiving instrumental support was the strongest predictor, as evidenced by its higher partial correlation (0.28) in comparison with those of other variables.

As shown in Table 7, two variables—less-educated mothers and receiving instrumental support—were statistically significant predictors of disability-related support. However, receiving instrumental support was the stronger predictor (0.23) in comparison with mothers’ education (-0.160).

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the predictors of FQOL, including social support and resilience, among Saudi Arabian families of children with disabilities. Overall, its results indicate that these families have a fairly high FQOL. Especially in the “family interaction” and “parenting” domains very high subscales were found, as both these domains relate to satisfying needs and bonding within the family setting (Alnahdi et al., 2022). These outcomes could be explained by earlier findings indicating higher family unity and levels of tolerance within families, including children with ID (Beighton & Wills, 2019; Lakhani et al., 2013). For the other three domains (emotional well-being, physical/material well-being, and disability-related support), the empirical means were slightly lower, but still rather high. These results can be explained by the association of these domains with aspects of support outside the family, where emotional well-being relates to the presence of support from relatives and friends, and disability-related support to the presence of support from service providers and professionals, who provide their services to families (Alnahdi et al., 2022). While physical/material well-being is related to the family’s source of income and material stability (Alnahdi et al., 2022), it is important to note that all participants having a high group mean does not automatically imply that all families experience high levels of FQOL, as individual experiences vary (as can be seen from the standard deviations). Hence, interventions should focus on families with low levels of FQOL.

This study investigated some possible factors that could contribute to a positive experience of FQOL.

First, the results corroborate that social support is the most important predictor of FQOL within this study. Social support comprises two main types: emotional and instrumental support. Wise and Stake (2002) consider both types to have a positive effect on well-being. In this study, family interactions for all forms of social support (receiving and giving emotional and instrumental support) were significant predictors. However, giving emotional support had the highest impact. It was also the strongest predictor for parenting and was significantly linked with this FQOL domain. Emotional support between family members is formed through sharing daily experiences, exchanging conversations, counseling, and spending time together (Bar-Tur et al., 2019). This explains the close association between emotional support, family interactions, and parenting.

Emotional well-being and (less surprisingly) disability-related support were predictors of receiving instrumental support, whereas for physical/material well-being, giving and receiving instrumental support were significant predictors. This result was expected because instrumental support is associated with auxiliary services, such as healthcare, financial, and home assistance, that may achieve well-being (George et al., 1989).

The high impact of support (e.g., social, emotional, and instrumental) is in line with previous studies (Cavkaytar et al., 2012; Hassanein et al., 2021; Hassanein et al., 2022; Lei & Kantor, 2022). However, the new aspect which this study brought to light is that for total FQOL, instrumental support seems so be somewhat more important than emotional support, as it was relevant for all its five domains. The importance of effective support stems from its importance to health, as many studies (Schultz et al., 2022; Semmer et al., 2008) have indicated a positive relationship between instrumental support and health care.

Second, as compared to receiving social support, giving support had higher relevance for the FQOL domains, as it was a significant predictor for four of its five domains. Giving support to others is more positively associated with well-being than receiving support (Zanjari et al., 2022). It also positively affects family members and improves their health (Reblin& Uchino, 2008). Hassanein et al. (2022) advise the importance of benefiting from this aspect in training families of children with disabilities to provide support to other families who have children with disabilities, by acting as their mentors. Support for families of children with disabilities becomes more beneficial when it comes from individuals who have faced needs and difficulties similar to theirs (Konrath & Brown, 2013). However, the positive benefits of social support are achieved through a balance of reciprocally providing and receiving support (Shakespeare-Finch & Obst, 2011).

Regarding parents’ socioeconomic background, only mothers’ education was found to be a significant negative predictor of disability-related support and emotional well-being, as the lower their education, the higher was their FQOL. However, fathers’ education did not seem to play a role in FQOL. This result might be linked to the fact that tasks related to the family and care taking (“unpaid care work”) are taken on by mothers, with fathers playing a subordinate role (UNRISD, 2010).

Not surprising and in line with previous research (Ferrer et al., 2017; Mas et al., 2016), monthly income plays a significant role in physical/material well-being.

Contrary to the results of previous studies (Boehm & Carter, 2019; Meral et al., 2013) the type of disability and its severity were not found as significant predictors of any FQOL domain. A possible explanation for this might be that this study included only two groups of children with disabilities. Moreover, those with “other disabilities” (other than ID) might be very heterogeneous in their intellectual functioning and disabilities.

Finally, against the backdrop of literature (Fereidouni et al., 2021; Savari et al., 2021), in this study, resilience did not show up as a significant predictor of FQOL. However, this does not automatically indicate that resilience is not of high relevance for FQOL. As social support and resilience are strongly linked with each other (Iacob et al., 2020), the overlapping variance might have just been too high to be a significant predictor when social support was already considered. Our finding that resilience did not emerge as a significant predictor of FQOL, while social support did, aligns with previous evidence from a Qatar. In a study involving 88 Qatari mothers of children with intellectual disabilities, giving and receiving social support together explained 62% of the variance in FQOL, whereas resilience did not contribute significantly once social support was entered into the regression model (Hassanein et al., 2021). The authors attributed this outcome to possible shared variance, proposing that social support, as a relational and culturally embedded resource, may subsume the effect of resilience. A similar finding was reported by Fereidouni et al. (2021), who also found resilience to be non-significant when both constructs were included in predictive models, likely due to high collinearity. This pattern may reflect overlapping variance between resilience and support, and the prominent role of social-communal mechanisms in collectivist societies. In such contexts, resilience may be enacted and sustained through interpersonal relationships rather than as a purely individual trait. These interpretations offer a plausible explanation for our findings and highlight the importance of future research investigating resilience as a mediator or moderator within the broader framework of social support.

Implications for practice for future research

During the last few decades, research on families, especially including families of children with disabilities, indicated that QOL also needs to be assessed using a family-centered approach, instead of simply focusing on an individual’s QOL. Based on this study’s findings, it is evident that social, instructional, and emotional support are crucial for FQOL. This study offers important implications for both policy-making and clinical practice.

The clear identification of emotional, social, and instrumental support as key predictors of FQOL among Saudi families of children with disabilities suggests the need for a comprehensive, family-centered support policy framework. Policymakers should allocate specific resources to strengthen family support networks. These networks facilitate the exchange of emotional and psychological support, and are particularly essential in disadvantaged areas that lack such resources. For example, support centers can actively advertise possibilities to enable contacting other families having children with disabilities. Bringing families together and helping them take action for others will effectively augment their FQOL. In addition, the findings support the integration of FQOL indicators into national assessments and service monitoring systems. The Saudi Ministries of Human Resources and Social Development and Health could operationalize this by incorporating FQOL measures into service eligibility criteria and by designing targeted interventions addressing specific domains such as parenting, emotional well-being, and financial stability.

Achieving clinical improvements in the care of families with children with disabilities necessitates a paradigm shift in the focus of service providers. Professionals, including special educators, rehabilitation therapists, and family counselors, should be trained to identify and foster supportive exchange mechanisms within and among families. This approach differs from the traditional focus on individual therapy or exclusively child-oriented interventions. For instance, incorporating structured peer mentoring programs into early intervention and disability centers can have a significant positive impact. Experienced parents can mentor new families, enhancing the long-term FQOL. Furthermore, support centers and NGOs should facilitate access to community services that provide practical assistance. These services include financial assistance, assistive technology, and respite care.

As with all studies, this study is affected by several limitations that require careful analysis. First, although data on the intellectual and functional abilities of the children were not collected using formal standardized assessments, severity information was reported by family members based on previous clinical diagnoses. This approach, while not clinical in nature, reflects how families understand and experience their child’s condition in daily life—an important perspective in family-centered research. Second, the study relied heavily on self-reported data from family members. While self-reports are essential for understanding personal experiences, they may be subject to social desirability bias and may not fully capture the complexity of family circumstances. Third, as occurs in many predictive models, the study may have omitted other relevant variables, such as the general health status of all family members. These variables may also influence FQOL outcomes. Finally, due to the correlational design, causal relationships cannot be inferred.

Future research employing longitudinal or experimental designs is needed to better understand the underlying causal mechanisms. In addition, future research could aim to gather more detailed information on children with disabilities. Additionally, conducting surveys that include multiple family members and incorporating diverse data sources will be beneficial. This approach would allow for a more comprehensive assessment of inter-rater variability and a more thorough understanding of FQOL.

Conclusion

This study underpinned the importance of social support in FQOL, not only receiving support, but also giving social support to people inside and outside the family, including relatives, neighbors, and friends, for psychologically benefitting FQOL. Therefore, this study reveals that having relationships and support networks are key factors for high FQOL. Moreover, instrumental support seems to be of higher relevance that emotional support. The fact that different patterns of predictors were found for FQOL’s five domains (family interaction, parenting, emotional well-being, physical/material well-being, and disability-related support) supports the importance of a domain-specific assessment of FQOL.

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

Acoba EF (2024) Social support and mental health: the mediating role of perceived stress. Front Psychol 15:1330720. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1330720

Alnahdi GH, Schwab S (2024) Families of Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: Variables Associated with Family Quality of Life. Children 11(6):734. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060734

Alnahdi GH, Schwab S, Elhadi A (2021) Psychometric properties of the Beach center family quality of life scale: Arabic version. J Child Fam Stud 30(12):3131–3140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02142-8

Alnahdi GH, Alwadei A, Woltran F, Schwab S (2022) Measuring Family Quality of Life: Scoping Review of the Available Scales and Future Directions. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(23):15473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315473

Altamimi A (2012) Relationship between social support and quality of life of parents of children with disabilities at early intervention. J Educ Sci 25(2):513–533. https://doi.org/10.12785/jeps/210104

Alwhaibi RM, Zaidi U, Alzeiby I, Alhusaini A (2020) Quality of life and socioeconomic status: a comparative study among mothers of children with and without disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Child Care Pract 26(1):62–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2018.1512951

Araújo CACD, Paz-Lourido B, Gelabert SV (2016) Types of support to families of children with disabilities and their influence on family quality of life. Cienc Saude Coletiva 21:3121–3130. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320152110.18412016

Arzeen N, Irshad E, Arzeen S, Shah SM (2020) Stress, depression, anxiety, and coping strategies of parents of intellectually disabled and non-disabled children. J Med Sci 28(4):380–383. https://doi.org/10.52764/jms.20.28.4.17

Barmak E, Süleymanoğlu PST, Çıldır B, Sarımehmetoğlu EA (2025) Investigation of family functioning and social support levels in families with a child with autism spectrum disorder. Hacet Univ Fac Health Sci J 12(1):130–145. https://doi.org/10.21020/husbfd.1359870

Bar-Tur L, Ifrah K, Moore D, Katzman B (2019) Exchange of emotional support between adult children and their parents and the children’s well-being. J Child Fam Stud 28:1250–1262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01355-2

Beach Center on Disability (2005) The Beach Center Family Quality of Life scale. Lawrence, KS: Beach Center, University of Kansas

Beighton C, Wills J (2019) How parents describe the positive aspects of parenting their child who has intellectual disabilities: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 32(5):1255–1279. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12617

Bhopti A, Brown T, Lentin P (2016) Family quality of life: a key outcome in early childhood intervention services—a scoping review. J Early Interv 38(4):191–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815116673182

Boehm TL, Carter EW (2019) Family quality of life and its correlates among parents of children and adults with intellectual disability. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil 124(2):99–115. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-124.2.99

Cavkaytar A, Ceyhan E, Adiguzel OC, Uysal H, Garan O (2012) Investigating education and support needs of families who have children with intellectual disabilities. Online Submiss 3(4):79–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/154079691303800403

Clark M, Brown R, Karrapaya R (2012) An initial look at the quality of life of Malaysian families that include children with disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 56(1):45–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01408.x

Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS(2013) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge

Dai Y, Chen M, Deng T, Huang B, Ji Y, Feng Y, Zhang L (2024) The importance of parenting self‐efficacy and social support for family quality of life in children newly diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: A one‐year follow‐up study. Autism Res 17(1):148–161. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.3061

Declercq F, Vanheule S, Markey S, Willemsen J (2007) Posttraumatic distress in security guards and the various effects of social support. J Clin Psychol 63(12):1239–1246. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20426

Dizdarevic A, Memisevic H, Osmanovic A, Mujezinovic A (2022) Family quality of life: perceptions of parents of children with developmental disabilities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Int J Dev Disabil 68(3):274–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2020.1756114

Egan LA, Park HR, Lam J, Gatt JM (2024) Resilience to stress and adversity: a narrative review of the role of positive affect. Psychol Res Behav Management, 2011-2038. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.s391403

Feng Y, Zhou X, Qin X, Cai G, Lin Y, Pang Y, Zhang L (2022) Parental self-efficacy and family quality of life in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in China: the possible mediating role of social support. J Pediatr Nurs 63:159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2021.10.014

Fereidouni Z, Kamyab AH, Dehghan A, Khiyali Z, Ziapour A, Mehedi N, Toghroli R (2021) A comparative study on the quality of life and resilience of mothers with disabled and neurotypically developing children in Iran. Heliyon 7(6):e07285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07285

Ferrer F, Vilaseca R, Guàrdia Olmos J (2017) Positive perceptions and perceived control in families with children with intellectual disabilities: relationship to family quality of life. Qual Quant 51:903–918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-016-0318-1

George LK, Blazer DG, Hughes DC, Fowler N (1989) Social support and the outcome of major depression. Br J Psychiatry 154(4):478–485. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.154.4.478

Giné C, Gràcia M, Vilaseca R, Salvador Beltran F, Balcells‐Balcells A, Dalmau Montala M, Maria Mas Mestre J (2015) Family quality of life for people with intellectual disabilities in Catalonia. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil 12(4):244–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12134

Hamama L (2024) Perceived social support, normalization, and subjective well-being among family members of a child with autism spectrum disorder. J autism Dev Disord 54(4):1468–1481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05857-9

Hassanein EE, Adawi TR, Johnson ES (2021) Social support, resilience, and quality of life for families with children with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 112:103910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103910

Hassanein EEA, Adawi TRT, Al-Attiyah AA, Elsayad WAM (2022) The relative contribution of resilience and social support to family quality of life of a sample of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder in Qatar. Dirasat Educ Sci 49(4):119–140. https://doi.org/10.35516/edu.v49i4.3327

Hu X, Wang M, Fei X (2012) Family quality of life of Chinese families of children with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 56(1):30–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01391.x

Iacob CI, Avram E, Cojocaru D, Podina IR (2020) Resilience in familial caregivers of children with developmental disabilities: a meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 50:4053–4068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04473-9

Jansen-van Vuuren J, Lysaght R, Batorowicz B, Dawud S, Aldersey HM (2021) Family quality of life and support: perceptions of family members of children with disabilities in Ethiopia. Disabilities 1(3):233–256. https://doi.org/10.3390/disabilities1030018

Kalisch R, Müller MB, Tüscher O (2015) A conceptual framework for the neurobiological study of resilience. Behav Brain Sci 38:e92. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x1400082x

Keith TZ (2019) Multiple regression and beyond: An introduction to multiple regression and structural equation modeling, 3rd ed. Routledge

Konrath S, Brown S (2013). The effects of giving on givers. In M L.Newman & N A.Roberts (Eds.), Health and social relationships: The good, the bad, and the complicated (pp. 39–64). American Psychological Association

Lakhani A, Gavino I, Yousafzai A (2013) The impact of caring for children with mental retardation on families as perceived by mothers in Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 63(12):1468. https://doi.org/10.31248/rjfsn2019.081

Lei X, Kantor J (2022) Social support and family quality of life in Chinese families of children with autism spectrum disorder: the mediating role of family cohesion and adaptability. Int J Dev Disabil 68(4):454–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2020.1803706

Ling G, Potměšilová P, Potměšil M (2022) Families who have a child with a disability: a literature review of quality of life issues from a Chinese perspective. J Fam Soc Work 25(2-3):67–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2023.2165586

Luckasson R (1992) Mental retardation, definition, classification, and systems of supports (9th ed.). Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation

Lunsky Y, Robinson S, Blinkhorn A, Ouellette-Kuntz H (2017) Parents of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and compound caregiving responsibilities. J child Fam Stud 26:1374–1379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0656-1

Mas JM, Baqués N, Balcells-Balcells A, Dalmau M, Giné C, Gràcia M, Vilaseca R (2016) Family quality of life for families in early intervention in Spain. J Early Interv 38(1):59–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815116636885

McCarthy E, Guerin S (2022) Family‐centred care in early intervention: a systematic review of the processes and outcomes of family‐centred care and impacting factors. Child Care Health Dev 48(1):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12901

Md-Sidin S, Sambasivan M, Ismail I (2010) Relationship between work-family conflict and quality of life: an investigation into the role of social support. J Manag Psychol 25(1):58–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011013876

Meral BF, Cavkaytar A, Turnbull AP, Wang M (2013) Family quality of life of Turkish families who have children with intellectual disabilities and autism. Res Pract Pers Sev Disabil 38(4):233–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/154079691303800403

Migerode F, Maes B, Buysse A, Brondeel R (2012) Quality of life in adolescents with a disability and their parents: the mediating role of social support and resilience. J Dev Phys Disabil 24:487–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-012-9285-1

Nam SJ, Park EY (2017) Relationship between caregiving burden and depression in caregivers of individuals with intellectual disabilities in Korea. J Ment Health 26(1):50–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2016.1276538

Norizan A, Shamsuddin K (2010) Predictors of parenting stress among Malaysian mothers of children with Down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res 54(11):992–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01324.x

Olsson MB, Hwang CP (2008) Socioeconomic and psychological variables as risk and protective factors for parental well‐being in families of children with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 52(12):1102–1113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01081.x

Park J, Hoffman L, Marquis J, Turnbull AP, Poston D, Mannan H, Nelson LL (2003) Toward assessing family outcomes of service delivery: Validation of a family quality of life survey. J Intellect Disabil Res 47(4‐5):367–384. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00497.x

Pozo P, Sarriá E, Brioso A (2014) Family quality of life and psychological well‐being in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: a double ABCX model. J Intellect Disabil Res 58(5):442–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12042

Rajan AM, John R (2017) Resilience and impact of children’s intellectual disability on Indian parents. J Intellect Disabil 21(4):315–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629516654588

Reblin M, Uchino BN (2008) Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Curr Opin Psychiatry 21(2):201–205. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0b013e3282f3ad89

Rillotta F, Kirby N, Shearer J, Nettelbeck T (2012) Family quality of life of Australian families with a member with an intellectual/developmental disability. J Intellect Disabil Res 56:71–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01462.x

Samuel PS, Rillotta F, Brown I (2012) The development of family quality of life concepts and measures. J Intellect Disabil Res 56(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01486.x

Savari K, Naseri M, Savari Y (2021) Evaluating the role of perceived stress, social support, and resilience in predicting the quality of life among the parents of disabled children. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912x.2021.1901862

Scherer N, Verhey I, Kuper H (2019) Depression and anxiety in parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one 14(7):e0219888. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219888

Schlebusch L, Dada S, Samuels AE (2017) Family quality of life of South African families raising children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 47:1966–1977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3102-8

Schultz BE, Corbett CF, Hughes RG (2022) Instrumental support: A conceptual analysis. Nurs Forum 57:665–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12704

Semmer NK, Elfering A, Jacobshagen N, Perrot T, Beehr TA, Boos N (2008) The emotional meaning of instrumental social support. Int J stress Manag 15(3):235. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.15.3.235

Shakespeare-Finch J, Obst PL (2011) The development of the 2-way social support scale: a measure of giving and receiving emotional and instrumental support. J Personal Assess 93(5):483–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.594124

Shang X, Fisher KR (2014) Social support for mothers of children with disabilities in China. J Soc Serv Res 40(4):573–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2014.896849

Sharma R, Singh H, Murti M, Chatterjee K, Rakkar JS (2021) Depression and anxiety in parents of children and adolescents with intellectual disability. Ind Psychiatry J 30(2):291. https://doi.org/10.4103/ipj.ipj_216_20

Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J (2008) The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med 15:194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

Summers JA, Poston DJ, Turnbull AP, Marquis J, Hoffman L, Mannan H, Wang M (2005) Conceptualizing and measuring family quality of life. J Intellect Disabil Res 49(10):777–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00751.x

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2013) Using multivariate statistics. MA: Pearson

UNRISD (2010) Why Care Matters for Social Development, Research and Policy Brief No. 9 (Geneva)

Vanderkerken L, Heyvaert M, Onghena P, Maes B (2019) The relation between family quality of life and the family‐centered approach in families with children with an intellectual disability. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil 16(4):296–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12317

Vernhet C, Michelon C, Dellapiazza F, Rattaz C, Geoffray MM, Roeyers H, … Baghdadli A (2022) Perceptions of parents of the impact of autism spectrum disorder on their quality of life and correlates: Comparison between mothers and fathers. Quality Life Res, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-021-03045-3

Vilaseca R, Gràcia M, Beltran FS, Dalmau M, Alomar E, Adam‐Alcocer AL, Simó‐Pinatella D (2017) Needs and supports of people with intellectual disability and their families in Catalonia. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 30(1):33–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12215

West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ (1995) Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In RH Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 56–75). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.935749

Wise D, Stake JE (2002) The moderating roles of personal and social resources on the relationship between dual expectations (for instrumentality and expressiveness) and weil-Being. J Soc Psychol 142(1):109–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540209603889

Zanjari N, Momtaz YA, Kamal SHM, Basakha M, Ahmadi S (2022) The influence of providing and receiving social support on older adults’ well-being. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health: CP EMH 18:e174501792112241. https://doi.org/10.2174/17450179-v18-e2112241

Zeng S, Hu X, Zhao H, Stone-MacDonald AK (2020) Examining the relationships of parental stress, family support and family quality of life: a structural equation modeling approach. Res Dev Disabil 96:103523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103523

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman Center for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2024-005. Open access funding provided by the University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H.A. and L.A.; Data curation, A.A.; Methodology, G.H.A., L.A and A.A.; Writing—original draft, A.A., and S.S.; Writing—review and editing, A.A., S.S.and G.H.A; Interpretation of results, A.A. and S.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University (Approval No: SCBR-28/2023; Date of approval: 31 August 2023). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Prior to data collection, all participants were provided with comprehensive information regarding the study, including its purpose, procedures, the intended use of data (i.e., analysis in aggregated form and publication in academic journals without disclosure of any personal information), and their right to withdraw at any time without negative consequences. Informed consent was obtained electronically between 5 September 2023 and 20 October 2023 through the online questionnaire platform. On the introductory page of the survey, participants were required to read the study information and indicate their agreement by clicking the “Agree” button before being able to proceed to the questionnaire. By submitting their responses, participants confirmed their informed consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alwadei, A., Schwab, S., Alotaibi, L. et al. Giving could be as important as receiving: the role of emotional and instrumental support in family interactions among Saudi Arabian families with children with disabilities. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1591 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05912-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05912-7