Abstract

Although computerized cognitive training (CCT) is an effective digital intervention for cognitive impairment, its dose-response relationship is understudied. This retrospective cohort study explores the association between training dose and cognitive improvement to find the optimal CCT dose. From 2017 to 2022, 8,709 participants with subjective cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and mild dementia were analyzed. CCT exposure varied in daily dose and frequency, with cognitive improvement measured weekly using Cognitive Index. A mixed-effects model revealed significant Cognitive Index increases across most dose groups before reaching the optimal dose. For participants under 60 years, the optimal dose was 25 to <30 min per day for 6 days a week. For those 60 years or older, it was 50 to <55 min per day for 6 days a week. These findings highlight a dose-dependent effect in CCT, suggesting age-specific optimal dosing for cognitive improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Computerized cognitive training (CCT) aims at improving or maintaining cognitive abilities by transforming the conventional cognitive training tasks into digital form. In CCT, patients are trained with computerized cognitive tasks which are designed from the classic psychiatric paradigms that can stimulate certain cognitive domains1. Under the assumption of maintaining or improving cognitive abilities, clinical trials have been designed to prove the effects of cognitive training in patients with cognitive impairment caused by diverse neurological or psychiatric diseases2,3,4,5. Due to the benefits of applying cognitive training in the early stages of dementia, cognitive training is recommended as a non-pharmacological treatment in the guideline of MCI6. However, despite lots of discussions about the efficacy of cognitive training7,8,9,10, few studies focused on the methodologies, especially on the training dose that could substantially affect the efficacy of cognitive training11,12.

A meta-analysis has summarized the types, delivery methods, and training dose of CCT to explore the optimal training plan for old people12. According to this study, training less than 30 min might be ineffective and training efficacy might decline when training more than 3 times a week12. However, the results were limited by the small number of literature and there is currently lack of clinical research focusing on the dose-response relationship of CCT. Consequently, studies always chose training doses according to training task contents or clinical practice rather than an evidence-based guideline, which ranged from 15 min to 100 min per day7,11. The “best guess” approach for dose selection would impede the findings in research and compromising the application of CCT in a evidence-based approach.

The dose-dependent characteristic has been observed in neuroplasticity that underlying the basis of cognitive training13,14. The short-term synaptic plasticity and long-term potentiation occur in milliseconds to minutes, but the formation of new neural fibers requires several days to months15,16. Changes in gray matters spread to the bilateral cortex after 3-week training of juggler, while one-week training only leads to changes in occipito-temporal junction17. Learning effects may also vary significantly when the learning session is prolonged18. Given that, we hypothesized that cognitive training might have dose-dependent effects on patients suffering from cognitive impairment.

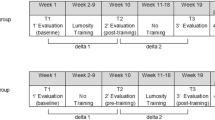

Therefore, we aimed to explore the dose-response relationship of CCT and estimate the optimal dose for patients with cognitive impairment in this retrospective cohort study using the real-world data. By comparing the weekly changes in Cognitive Index19 (WCCI) in different dose groups (Fig. 1), we illustrated the dose-response relationship of CCT and found age substantially affecting the dose-response relationship. Specifically, the optimal doses were different in participants younger or older than 60 years. The estimation of the optimal dose of CCT could not only help physicians with suggestions on treatment doses for patients with cognitive impairment, but also make the CCT a more robust evidence-based therapy in cognitive disorders.

Results

Demographic characteristics of study population

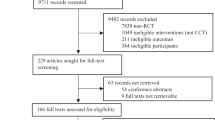

From 2017 to 2022 we enrolled 21,845 eligible participants in total and the details of the recruitment process are presented in a flowchart (Fig. 2). The demographic characteristics of the final 8709 participants are presented in Table 1. The average (SD) age of the participants was 63.2 (12.3) years. And 4752 participants (54.6%) had less than a high school education; 3957 participants (45.4%) had high school or higher education. Of the participants included, 5301 (60.9%) were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 2735 (31.4%) were diagnosed with mild dementia, and 673 (7.7%) were diagnosed with subjective cognitive decline (SCD). Participants were grouped into two age groups, in which 3691 participants were under 60 years and 5018 participants were 60 years or older.

Association of the training frequency with cognitive improvement

The relationship between the training frequency and WCCI showed a trend that the training effect would reach the threshold when training for 6 days per week (Fig. 3a). And training for 7 days per week would cause a sharp decline in WCCI. The trend was verified in the mixed effect model in both age groups. In the participants aged under 60 years old, an increasing trend was found in WCCI (p value for trend: <0.001) and reach a maximum of 1.2 (95% CI, [0.7, 1.8], p < 0.001; Fig. 3b; Supplementary Table 3) when taking training for 6 days per week. In participants aged 60 years or older, we also observed an increasing trend in WCCI (p value for trend: 0.04) for training days. The increasing WCCI reached a threshold of 0.9 (95% CI, [0.4, 1.4], p < 0.001; Fig. 3c; Supplementary Table 4) when taking training for 6 days per week.

Dose-response relationship of training frequency was first explored by comparing the absolute WCCI among various dose groups in the entire study population (a) with black circles indicating mean value of WCCI. For patients aged under 60 years (b), or aged 60 years or older (c), the dose-response relationship of training frequency was elucidated through estimated cognitive improvement with (red circles) or without (blue circles) statistical significance based on mixed effects model. The error bar depicted the 95% confidence interval.

Association of the daily training dose with cognitive improvement

Next, we examined the dose-response relationship between daily dose and WCCI (Fig. 4). We also observed a trend of increasing WCCI with the extension of daily dose and the WCCI reached the maximum when training for 45 to <50 min/day. When the training duration exceeded 55 min/day, there was a sharp decline in WCCI (Fig. 4a). The mixed effect model revealed an age-dependent dose-response relationship in daily dose. In the participants aged under 60 years old, an increasing trend was observed in WCCI (p value for trend: <0.001) among the participants taking 1–6 times the baseline daily dose. And the optimal daily dose was 5–6 times the baseline daily dose (25 to <30 min/day: adjusted effect estimate, 1.9 (95% CI, [0.8, 3.0]; p < 0.001; Fig. 4b; Supplementary Table 5). This estimated dose is in accordance with the first peak of WCCI in Fig. 4a. In participants aged 60 years or older, we observed a positive trend in WCCI (p value for trend: <0.001) for the dose range from 1 to 11 times the baseline daily dose (5 to <55 min/day; Supplementary Table 6). The optimal dose was 10–11 times the baseline dose (50 to <55 min/day: adjusted effect estimate, 3.9 (95% CI, [1.4, 6.4]; p = 0.002); Fig. 4c; Supplementary Table 6) and training for 60 min and above did not confer further increases in WCCI (adjusted effect estimate, 2.0 (95% CI, [0.2, 3.9]; p = 0.03)).

Dose-response relationship of daily dose was first explored by comparing the absolute WCCI among various dose groups in the entire study population (a) with black circles indicating mean value of WCCI. For patients aged under 60 years (b), or aged 60 years or older (c), the dose-response relationship of daily dose was elucidated through estimated cognitive improvement with (red circles) or without (blue circles) statistical significance based on mixed effects model. The error bar depicted the 95% confidence interval.

Ultimately, we investigated the variations in the dose-response relationship across SCD, MCI, or mild dementia participants with our subgroup analysis demonstrating consistent trends across the three subgroups (Supplementary Figure 1). Significant trends (p < 0.05) were observed in WCCI with increased daily dose in all subgroups and with training frequency in SCD or MCI subgroups. The exception was the mild dementia subgroup, in which the p value for trend in training frequency did not reach significance (Supplementary Tables 7–12).

Discussion

Using the large cohort of computerized cognitive training in the real world, we analyzed the dose-response relationship between training doses and changes in cognitive abilities which were measured by Cognitive Index. Our findings give several contributions to the application of CCT: (1) showed dose-dependent effects in cognitive training and suggested the optimal doses for self-adapted CCT, (2) the results also suggested that higher dose would not certainly lead to the increase in WCCI, (3) further, our results show that age has an impact on the dose-response relationship. The optimal daily dose was doubled in the older participants (age ≥60 years) compared to the younger participants (age <60 years). The optimal training frequency was 6 days per week in both age groups.

Our findings revealed that the optimal doses were estimated as 25 to <30 min training per day in participants under 60 years old. Some studies chose the daily doses closed to the optimal daily dose found in our study and showed a significant improvement in cognitive abilities with the intervention of CCT20,21,22,23. Our findings also revealed the optimal daily dose of 50 to <55 min/day in participants aged 60 years or older. Thus, in future clinical trials, higher dose may be considered for administration when recruiting participants aged 60 years or older. Meanwhile, our findings revealed the optimal training frequency was 6 days/week. However, most studies on CCT set the training frequency to less than 6 days per week7, indicating that the training effect may not reach the maximum.

CCT beyond the optimal dose does not yield incremental cognitive benefits according to our results. A meta-analysis has mentioned there may be a maximal dose of cognitive training after which the training effects would decline, although it concluded that the optimal training frequency was 3 days a week12. Factors such as cognitive fatigue may be responsible for declining training effects24. Similar non-linear dose-response models were found in other non-pharmacological interventions such as walking steps and moderate-to-vigorous physical activities (MVPA)25,26,27.

The dose-response relationship and training efficacy were differentiated by age groups (<60 years and ≥60 years). The older group got the highest cognitive gains when training for almost double dose than the younger group. In a study investigating the association between daily steps and all-cause mortality, different results were also observed in two age groups (<60 years and ≥60 years)27. However, the older people required a small number of steps to get similar health benefits compared to the younger people. The decreasing metabolic rate, aerobic capacity and biochemical inefficiencies may explain the difference in walking steps27. The decreasing volume of brain structure, neural excitability and plasticity could impair the learning ability in older people28,29. Therefore, the older people might need more time to gain the optimal training effect.

Investigating the dose-response relationship is a crucial prerequisite for establishing non- pharmacological intervention as an robust evidence-based therapy30. A dearth of research on treatment dose has impeded CCT’s application as a broadly acceptable therapy for cognitive disorders, although there has been substantial exploration of the effectiveness of CCT7. It is hard to study the dose-response relationship of cognitive training using inflexible and time-limited randomized controlled trials which cannot satisfy the patients’ needs11. Meta-analysis may find clues for the dose-response associations, but the results are limited by sparse data and diverse types of training12. Although a few clinical trials reported the effect of training doses, they mainly study the cumulative dose through the clinical trials, and the results were limited by small sample size and trial design31,32. Specifically, Lampit et al. reported the relationship between training weeks and cognitive abilities32. They found the global cognitive abilities reaching the maximum at the end of training (36 weeks) but the optimal daily or weekly dose was unknown. Some research of other non-pharmacological interventions studies the dose-response relationship by analyzing the average dose of the individual (i.e., one patient under one exposure)25,27 which would neglect the variation of dose through the study.

One major strength of our study is using the repeated measurement data from a large cohort in the real world, in contrast to the other studies. CCT enables us to monitor the training effects from the beginning to the end of training and makes it possible to analyze the dose-response relationship by measuring the exposures (dose) and outcomes (changes in cognitive abilities) every week. Similarly, longitudinal real-world data from a cognitive training platform has been used to analyze the learning trajectories of cognitive training tasks33. However, this study focused on predicting the next performance in cognitive training and the effect of training dose has yet to be elucidated.

Our study has some limitations and results should be interpreted with caution. The study results were based on the repeated measurement data of a retrospective cohort. Thus, the results are limited by selection bias and confounding bias such as history bias, testing bias, and test-retest effect. However, the large sample size and mixed effects model can reduce these biases. The second limitation concerns the validity of Cognitive Index. Although the validity of the Cognitive Index has been examined in a previous study in patients with MCI and dementia19, it should be further tested with longitudinal data to ensure that the changes in Cognitive Index can reflect cognitive abilities. A third limitation pertains to the limited sample size for subgroup analyses. Although subgroup analyses revealed consistent trends across different cognitive statuses, it was notable that more participants are required to make the findings more robust for specific type of population. Another limitation of our study concerns potential cognitive improvement due to the practice effect from continuous cognitive testing. However, the varied content of cognitive assessments each week helped mitigate the practice effect. Furthermore, as the practice effect impacted all participants simultaneously, leading to improvement in everyone’s Cognitive Index, the impact of this practice effect on estimating optimal dose was limited.

In conclusion, we revealed the dose-response relationship of CCT with multilevel variables and found the optimal doses in two age groups (<60 and ≥60 years). Our results provided the evidence for dose selection in CCT and can contribute to the future guidelines for making the CCT a broadly acceptable treatment.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this retrospective cohort study conducted in a real-world setting, we screened individuals with cognitive complaints or impairments who were users of the reported computerized cognitive training platform34 from 2017 to 2022 in Beijing. This cognitive training platform recruited participants from community residents and hospital outpatients. Before initiating cognitive training, it was mandatory to assess the cognitive status of each registered participant. Qualified assessors conducted cognitive assessment (i.e., MoCA and CDR) in both community settings and hospitals, and cognitive status was diagnosed based on specific diagnostic criteria. The diagnosis of SCD was based on cognitive complaints without evidence of objective cognitive decline. MCI was diagnosed using criteria derived from Petersen criteria: (1) cognitive complaints (2) Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)35 with a score of ≥18 to ≤26 (adjusted for education level), Clinical Dementia Rating Scale global score (CDR-GS) ≤ 0.5 (at least one cognitive domain ≥0.5) (3) maintaining independence in activities of daily living36,37 (4) not demented. Diagnosis of dementia was based on DSM-V criteria for major neurocognitive disorder38, with dementia severity rated using CDR-GS (mild: 0.5–1, moderate: 2, severe: 3)39. Diagnoses including cognitive status and other medical conditions were documented in the user profiles after confirmation by neurologists, geriatricians, or certified general practitioners. When documenting diagnoses on the platform, doctors selected diagnoses from a list of options or manually entered them if not listed.

During the initial screening, 21,845 participants were recruited. The inclusion criteria were participants with SCD, MCI, or mild dementia, age ≥40 years, and training duration ≥2 weeks. The exclusion criteria included: Cognitive status included moderate to severe dementia; diagnoses encompassed cancer, unstable systemic disease, or psychiatric disorders. The final analysis included 8709 participants diagnosed with SCD, MCI, or mild dementia. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Xuanwu Hospital (NO.2023027) with a waiver of informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study using de-identified data. The study protocol has been registered at Clinicaltrial.gov (NCT05922319).

Computerized cognitive training

Participants diagnosed with SCD, MCI, or mild dementia were suggested to take the CCT as therapy. The demographic information and diagnosis were accessible on the CCT platform34 and the data extraction was permitted by the platform users. Time and scores of training tasks were automatically recorded by the CCT platform. The CCT procedure was proven to be effective in improving cognitive function and was described in the Supplementary Materials34. Briefly, the training tasks target cognitive abilities of human intelligence (defined according to Cattell–Horn–Carroll (CHC) intelligence theory40). Every task was designed to target specific cognitive abilities based on the psychological paradigms. Participants were encouraged to take the cognitive training at home for at least 3 days per week, for at least 20 min per training day. The cognitive function was assessed by the Cognitive Index which was calculated based on the performance in the CCT with a strong correlation with MoCA (r = 0.8) and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (r = 0.7)19.

Procedure of CCT

Computerized cognitive training (CCT) used in the research was designed to exercise multiple cognitive domains (Memory, executive function, thinking, perception, attention, calculation etc.) of people34. The training tasks were designed based on the psychological paradigms such as Corsi block-tapping task, Delayed match to sample, Face-name task, Spatial monitoring task, Size matching task, Visual search task, Pursuit tracking task, Continuous performance test, Flanker task, Stroop task, Mental arithmetic task and so on. For each paradigm, multiple training tasks were designed, and each task was set into different levels of difficulty. We recommended users to complete a minimum of 7 specific cognitive training tasks each day, with each task lasting 2 min, after finishing 6- minute warm-up exercise. At the beginning of the training, every user was given the similar training tasks with the same level of difficulty. The software will adjust the content of the next training task based on the user’s performance on the initial round of training to ensure that the training effectively targets impaired cognitive functions. The difficulty of tasks aimed at improving the same cognitive function will also gradually increase in response to the user’s performance.

Cognitive Index

The performance in every task was recorded as task scores and was normalized based on the percentile in the population. The cognitive ability of a specific cognitive domain was obtained by averaging all the task scores targeting the same cognitive domain. The Cognitive Index was calculated by averaging the scores for each cognitive domain19.

Exposures and outcomes

The exposure was CCT with different training doses. The training dose of CCT was usually defined as training frequency (e.g., the number of training days per week) or training duration (e.g., the minutes of training) in a certain period11,12. Specifically, we assessed the effect of number of training days per week (frequency) and average training duration per training day (daily dose) in this study. The relationship between the training frequency and daily dose can be illustrated with this formula:

The daily dose was divided into 13 categories with an interval of 5 min and the training frequency has 7 categories according to the number of training days per week.

The outcome was the change in cognitive abilities from last week. As shown in the Fig. 1, the exposures and outcomes were measured repeatedly during the training process. At the end of each week, the CCT platform recorded variables such as training duration in a week, number of training days in a week, and the real-time Cognitive Index. The Cognitive Index was used to monitor cognitive abilities through the training process, and the weekly change in Cognitive Index between adjacent weeks can present the fluctuation in cognitive status. Consequently, the outcome of this research was the change in Cognitive Index between adjacent weeks which was defined as weekly changes in Cognitive Index.

Statistical analysis

Participants’ characteristics were summarized by the mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables (i.e., age) and as the frequency and percentage for categorical variables (i.e., sex, education level, and cognitive status). We first explored the effect of training frequency or daily dose on WCCI, separately. We calculated the average WCCI of various dose groups to investigate the dose-response relationship, along with the corresponding standard error. Then, we applied the linear mixed effects model for analysis and treated the training frequency and daily dose as fixed effects in the model. With the linear mixed effects model, we were able to (1) account for the random effects due to the individual variability, for the cognitive training record was measured repeatedly of each participant; (2) assess the effect of training frequency and daily dose simultaneously. With the mixed effects model, we aimed to find the optimal dose (i.e., the training frequency or daily dose at which the maximum WCCI was observed), in terms of the maximum fixed effect of training frequency or daily dose estimated by the model. The covariates contained the education level, age, and sex. In the process of modeling, we selected the proper model based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and the interpretation of the model. To ensure the balance between the complexity and interpretability, we finally chose to apply random intercept fixed slope model for assessing the dose-response relationship of CCT.

According to the definition of old people by the World Health Organization41, sixty years old is the cut-off point to separate whether people could be defined as “old people”, and the cognitive ability is largely affected by age. Thus, we applied the random intercept fixed slope model to participants aged 60 years or older, or participants under 60 years old, separately. The dose-response relationship was explored separately in the two age groups. To investigate differences among participants with various cognitive statuses, we conducted subgroup analysis to examine the dose-response relationship in individuals with SCD, MCI, or mild dementia. To assess the association between the training effects (illustrated by WCCI) and increasing training dose, we conducted a trend analysis. We calculated the p value for trend by using a quasi-continuous variable in the model. A p value for trend less than 0.05 was considered indicative of a significant association.

Modeling process

Before the final models were built, four potential models were built to assess the balance between complexity and interpretability. The four models were assessed based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and the interpretation of the model. The AIC and BIC are both penalized-likelihood information criteria and the smaller values indicate the better model. The four models included: a random intercept model (model 1), a random intercept fixed slope model (model 2), a random intercept random slope model (model 3), and a random intercept random slope with fixed quadratic term model (model 4). As presented in Supplementary Table 1, model 4 conveys the smallest AIC and BIC. However, the quadratic term in model 4 can bring the complexity of interpretation, and the AIC and BIC index did not present a large decrease comparing to model 3. Furthermore, as presented in Supplementary Table 2, by freeing the slope term as model 3 did not improve the model performance significantly. Therefore, the final decision is to apply random intercept fixed slope model (model 2) for the rest of the modeling process.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy purposes but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Turnbull, A., Seitz, A., Tadin, D. & Lin, F. V. Unifying framework for cognitive training interventions in brain aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 81, 101724 (2022).

Edwards, J. D. et al. Randomized trial of cognitive speed of processing training in Parkinson disease. Neurology 81, 1284–1290 (2013).

Bowie, C. R. et al. Cognitive remediation for treatment-resistant depression: effects on cognition and functioning and the role of online homework. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 201, 680–685 (2013).

Hagovska, M., Takac, P. & Dzvonik, O. Effect of a combining cognitive and balanced training on the cognitive, postural and functional status of seniors with a mild cognitive deficit in a randomized, controlled trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 52, 101–109 (2016).

Subramaniam, K. et al. Computerized Cognitive Training Restores Neural Activity within the Reality Monitoring Network in Schizophrenia. Neuron 73, 842–853 (2012).

Petersen, R. C. et al. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 90, 126–135 (2018).

Hill, N. T. et al. Computerized Cognitive Training in Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 174, 329–340 (2017).

Gates, N. J. et al. Computerised cognitive training for preventing dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd012279.pub2 (2019).

Willis, S. L. et al. Long-term Effects of Cognitive Training on Everyday Functional Outcomes in Older Adults. JAMA 296, 2805 (2006).

Rosen, A. C., Sugiura, L., Kramer, J. H., Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Gabrieli, J. D. Cognitive Training Changes Hippocampal Function in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Pilot Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 26, 349–357 (2011).

Hampstead, B. M., Gillis, M. M. & Stringer, A. Y. Cognitive rehabilitation of memory for mild cognitive impairment: a methodological review and model for future research. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 20, 135–151 (2014).

Lampit, A., Hallock, H. & Valenzuela, M. Computerized cognitive training in cognitively healthy older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of effect modifiers. PLoS Med. 11, e1001756 (2014).

Loriette, C., Ziane, C. & Ben Hamed, S. Neurofeedback for cognitive enhancement and intervention and brain plasticity. Rev. Neurol. 177, 1133–1144 (2021).

Lüscher, C., Nicoll, R. A., Malenka, R. C. & Muller, D. Synaptic plasticity and dynamic modulation of the postsynaptic membrane. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 545–550 (2000).

Tetzlaff, C., Kolodziejski, C., Markelic, I. & Wörgötter, F. Time scales of memory, learning, and plasticity. Biol. Cybern. 106, 715–726 (2012).

Zucker, R. S. & Regehr, W. G. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 355–405 (2002).

Driemeyer, J., Boyke, J., Gaser, C., Büchel, C. & May, A. Changes in Gray Matter Induced by Learning—Revisited. PLoS One 3, e2669 (2008).

Shibata, K. et al. Overlearning hyperstabilizes a skill by rapidly making neurochemical processing inhibitory-dominant. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 470–475 (2017).

Liu, L.-Y. et al. Validation of a computerized cognitive training tool to assess cognitive impairment and enable differentiation between mild cognitive impairment and dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-230416 (2023).

Tarraga, L. A randomised pilot study to assess the efficacy of an interactive, multimedia tool of cognitive stimulation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 77, 1116–1121 (2006).

Sheng, C. et al. Advances in Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Subjective Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 77, 903–920 (2020).

Mingming, Y., Bolun, Z., Zhijian, L., Yingli, W. & Lanshu, Z. Effectiveness of computer-based training on post-stroke cognitive rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 32, 481–497 (2022).

Bakheit, A. M. O. et al. A prospective, randomized, parallel group, controlled study of the effect of intensity of speech and language therapy on early recovery from poststroke aphasia. Clin. Rehabil. 21, 885–894 (2007).

Holtzer, R., Shuman, M., Mahoney, J. R., Lipton, R. & Verghese, J. Cognitive Fatigue Defined in the Context of Attention Networks. Aging Neuropsychol. Cognit. 18, 108–128 (2010).

Del Pozo Cruz, B., Ahmadi, M., Naismith, S. L. & Stamatakis, E. Association of Daily Step Count and Intensity With Incident Dementia in 78 430 Adults Living in the UK. JAMA Neurol 79, 1059–1063 (2022).

Ekelund, U. et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ, l4570, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4570 (2019).

Paluch, A. E. et al. Daily steps and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis of 15 international cohorts. The Lancet Public Health 7, e219–e228 (2022).

Burke, S. N. & Barnes, C. A. Neural plasticity in the ageing brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 30–40 (2006).

Kirov, I. I. et al. Global brain volume and N-acetyl-aspartate decline over seven decades of normal aging. Neurobiol. Aging 98, 42–51 (2021).

Sikkes, S. A. M. et al. Toward a theory‐based specification of non‐pharmacological treatments in aging and dementia: Focused reviews and methodological recommendations. Alzheimers Dementia 17, 255–270 (2021).

Hampstead, B. M., Sathian, K., Moore, A. B., Nalisnick, C. & Stringer, A. Y. Explicit memory training leads to improved memory for face-name pairs in patients with mild cognitive impairment: results of a pilot investigation. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 14, 883–889, (2008).

Lampit, A. et al. The Timecourse of Global Cognitive Gains from Supervised Computer-Assisted Cognitive Training: A Randomised, Active-Controlled Trial in Elderly with Multiple Dementia Risk Factors. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 1, 33–39 (2014).

Steyvers, M. & Schafer, R. J. Inferring latent learning factors in large-scale cognitive training data. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 1145–1155 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. The effects of 7‐week cognitive training in patients with vascular cognitive impairment, no dementia (the Cog‐VACCINE study): A randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Dementia 15, 605–614 (2019).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699 (2005).

Lawton, M. P. & Brody, E. M. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9, 179–186 (1969).

Rai, G. S., Gluck, T., Wientjes, H. J. & Rai, S. G. The Functional Autonomy Measurement System (SMAF): a measure of functional change with rehabilitation. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 22, 81–85 (1996).

Association, A. P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 5th ed. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (2013).

Berg, L. Clinical Dementia Rating. Br. J. Psychiatry 145, 339–339, https://doi.org/10.1192/s0007125000118082 (1984).

McGrew, K. S. in Contemporary Intellectual Assessment: Theories, Tests, and Issues. (eds Flanagan, D. P. & Harrison, P. L.) Ch. The Cattell-Horn-Carroll Theory of Cognitive Abilities: Past, Present, and Future, 136–181 (The Guilford Press, 2005).

World Health Organization. China country assessment report on ageing and health (WHO, 2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFC3602600), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82220108009, 81970996). The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.T. acquired funding, designed the study, and supervised the study’s implementation. L.L. handled the implementation of the study, data analysis and manuscript writing. H.W. designed the study and statistical analysis methods. L.L. and H.W. contributed equally to this study and shared co-first authorship. Z.Z., Q.Z. and M.D. collected, managed and analyzed the data. Y.X., Z.M., L.C. and X.W. participated in the study design and manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Z.Z., Q.Z., M.D., Z.M., L.C. and X.W. are employed by Beijing Wispirit Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China. All the authors declare no conflicts of interest in the conduct of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Wang, H., Xing, Y. et al. Dose–response relationship between computerized cognitive training and cognitive improvement. npj Digit. Med. 7, 214 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01210-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01210-9

This article is cited by

-

Developing digital biomarker for predicting cognitive response to multi-domain intervention

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Donepezil for cancer-related cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis

Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2025)