Abstract

Men who have sex with men (MSM) who use dating applications (apps) have higher rates of engaging in condomless anal sex than those who do not. Therefore, we conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of an interactive web-based intervention in promoting safer sex among this population. The intervention was guided by the Theory of Planned Behavior and co-designed by researchers, healthcare providers, and MSM participants. The primary outcome was the frequency of condomless anal sex in past three months. Secondary outcomes included five other behavioral outcomes and two psychological outcomes. This trial was registered on ISRCTN (ISRCTN16681863) on 2020/04/28. A total of 480 MSM were enrolled and randomly assigned to the intervention or control group. Our findings indicate that the intervention significantly reduced condomless anal sex behaviors by enhancing self-efficacy and attitudes toward condom use among MSM dating app users, with the effects sustained at both three and six months.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, online dating has become increasingly popular and widespread worldwide, revolutionizing the way people approach potential partners. At the same time, smartphone dating applications (apps) have grown in popularity among men who have sex with men (MSM)1. With anonymity and geo-location features, dating apps have played a central role in facilitating sexual partner-seeking among MSM2,3. However, it is important to note that while dating apps can make it more convenient and efficient for users to seek potential sexual or romantic partners4, they also greatly enhance the convenience of casual sex5. When compared to traditional offline venues, dating apps offer MSM an overabundance of connections5, and their network of sexual relationships becomes more mixed6. However, research has shown that sexual mixing patterns and the social networks that shape them could, in part, determine the transmission dynamics of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among MSM7. Thus, the sexual safety of MSM dating app users requires greater attention.

Existing research has demonstrated a robust association between using dating apps and specific sexual behaviors, showing that dating app users are more likely to have had condomless sexual intercourse than non-dating app users8,9. In addition, other behaviors, such as substance use during sex (chemsex) and group sex, are also common among dating app users10,11. These aforementioned behaviors have long been considered “risky” or “unsafe”, as any one of these sexual behaviors can be associated with multiple potential risks, including the acquisition or transmission of HIV or STIs2,3. Using “unsafe” or “risky” might be legitimate from an HIV or STI prevention perspective, but such risk-based language may perpetuate stigma and be perceived as judgmental, undermining efforts to promote sexual health12. Diverse factors can constrain or facilitate individuals’ actions and the associated level of sexual risk, so it is important to always maintain linguistic precision and neutrality, as well as acknowledge the social context when promoting safe sex practices.

It has been well documented that MSM populations are disproportionately affected by HIV and other STIs13,14, highlighting the importance of specific prevention interventions. To prevent HIV infections, researchers and scholars worldwide have tried different measures, the most prevalent of which include traditional behavioral prevention (i.e., consistent and correct condom use) and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)15. However, despite the growing scientific evidence of its efficacy and safety, PrEP is not yet widely available in Southeast Asia, and uptake of PrEP remains low in the Asia-Pacific region16. In China, it is estimated that less than 1% of MSM at high risk of infection are using PrEP for HIV prevention17. Furthermore, delivery of PrEP without proper assessment and monitoring by healthcare professionals may lead to inappropriate use and, ultimately, failure to prevent HIV transmission18.

Currently, PrEP is not available as part of public healthcare services in Hong Kong and can only be purchased from private healthcare providers at a high cost or from other countries such as Thailand19. In addition, as a tailored approach to preventing HIV infection, PrEP is not effective in preventing other STIs. As such, behavioral interventions that promote the consistent and correct use of condoms remain the most cost-effective HIV/STI prevention methods20. However, condoms are not always used consistently among MSM, and there is evidence that frequent dating app users are more likely to report inconsistent condom use with their casual partners21. It is therefore important to improve condom use to prevent MSM from being affected with HIV and other STIs. Given the popularity of dating app use and its internet-based nature, there is huge potential for health promotion via the Internet. Consequently, innovative online interventions that promote safer sex practices among dating app users should be designed and implemented, as they can contribute to the availability of rich information and the delivery of multi-component interventions22.

Interactive web-based interventions have been reviewed and proven to be effective in sexual health promotion23. To date, there have been a growing number of online interventions designed for MSM populations to promote HIV-preventive behaviors22,24,25. However, most of these interventions have been conducted in Western countries, with study samples focusing on populations such as White and African Americans, while fewer studies have been conducted in non-Western contexts25. Current intervention studies in China have identified programs that have been effective in promoting HIV self-testing among MSM26,27, although not all studies emphasizing HIV have produced significant improvements in most common prevention behaviors28,29. It has been suggested that HIV was not the most interesting topic of discussion among Hong Kong MSM Internet users29. In addition, while intervention content is generally delivered through a pre-determined sequence of steps, existing evidence is inconclusive as to whether this navigation style or self-paced intervention is more effective25. Self-paced interventions, which allow the recipient to control the pace, could be more time-flexible and user-friendly, and more user control has been shown to positively influence users’ perception of efficiency30, thus warranting more research.

Since there is still stigma attached to HIV in Asian cultures, and homosexuality remains a taboo in traditional Chinese culture, web-based online interventions for MSM are highly warranted and recommended because of their potential advantages of being anonymous, repetitive, and delivered at a convenient time compared to face-to-face interventions23. Although there are intervention studies for Chinese MSM, they have not targeted current dating app users and have overwhelmingly emphasized HIV prevention. Additionally, given that dating app use is an emerging sexual risk factor31, there is an urgent need for tailored, interactive interventions to promote safer sex behaviors. In Hong Kong, where PrEP is not yet readily available, it is particularly important to promote behaviors such as consistent condom use and regular HIV/STI testing. Therefore, this study aimed to develop a self-paced, interactive web-based intervention to encourage positive attitudes toward consistent condom use and HIV/STI testing, and to evaluate its effectiveness in promoting these behaviors among MSM currently using dating apps.

Results

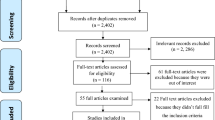

From 30 November 2020 to 19 October 2021, a total of 480 MSM were enrolled in the study, with 240 participants in the intervention group and 240 in the control group. Of these, 429 participants completed the 3-month follow-up (T1) interview, while 387 completed the 6-month follow-up (T2) interview, resulting in an overall dropout rate of 19.38%. The trial flow diagram for the recruitment and follow-up of participants is shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics and baseline study outcomes of the study participants. The mean (standard deviation) age was 28.69 (7.43) years. Of the 480 participants, 401 (83.54%) were gay and 79 (16.46%) were bisexual and other sexual orientations. Regarding relationship status, approximately half of the participants (237/480, 49.38%) were in a relationship or married, while the other half (243/480, 50.63%) were single. Among all the participants, 417 (86.88%) had a bachelor’s degree or higher and 63 (13.13%) did not. In terms of employment, 287 (59.79%) of the 480 participants were employed full-time, while 193 (40.21%) were not.

In terms of baseline study outcomes, 205 participants (42.71%) reported engaging in condomless anal sex within the last three months. During the same period, 50 participants (10.42%) participated in chemsex, and 82 participants (17.08%) engaged in group sex. Additionally, 170 participants (35.42%) underwent HIV testing, while 92 participants (19.17%) were tested for other STIs within the last three months. No significant heterogeneity in demographic data and study outcomes was found between study non-dropouts and dropouts, except for significant differences in the mean age and the number of participants who had engaged in chemsex in the last three months. Detailed comparisons between study dropouts and non-dropouts are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Regarding the primary outcome measure (i.e., condomless anal sex within the last three months), participants in the intervention group exhibited a significant reduction in the likelihood of engaging in condomless anal sex in the last three months (overall time-by-group interaction: p = 0.010). At follow-up interviews, the between-group difference was statistically significant (3-month follow-up: OR = 0.59, p = 0.009; 6-month follow-up: OR = 0.64, p = 0.040), indicating that participants in the intervention group were less likely to engage in condomless anal sex within the last three months at both follow-up time points. However, the time-by-group interaction was not statistically significant for other behavioral outcomes related to chemsex, group sex, HIV testing, and other STI testing, suggesting that the intervention did not alter these outcomes. Additionally, the analysis of the number of sex partners with whom participants had condomless anal sex in the last three months revealed a statistically significant overall time-by-group interaction (p = 0.043). Within the intervention group, there was a statistically significant decrease in the mean number of partners from baseline to the 6-month follow-up (mean difference = −0.26, p = 0.039). However, no statistically significant within-group differences were observed in the control group. Detailed results can be found in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 2.

For psychological outcome measures, the intervention group showed a significantly larger improvement in condom use self-efficacy, as measured by the CSES total score (time-by-group interaction: p < 0.001). The between-group difference was statistically significant at both 3-month (mean difference: 3.46, p < 0.001) and 6-month follow-up interviews (mean difference: 3.31, p = 0.002). Moreover, the intervention group demonstrated a significantly larger improvement in condom use attitude, as measured by the MCAS total score (time-by-group interaction: p < 0.001). The between-group difference was statistically significant at both 3-month (mean difference: 3.77, p = 0.047) and 6-month follow-up interviews (mean difference: 8.65, p < 0.001). Table 3 presents these results. Additionally, the intervention group exhibited significantly larger improvements in all subscale scores of the CSES, and in three subscale scores of the MCAS. Supplementary Table 3 presents the results of these subscale scores.

The mediation analysis revealed that the intervention did not exert a statistically significant direct effect on the primary outcome after accounting for the influence of mediators (OR: 0.77, p = 0.234). However, the analysis identified significant indirect effects of the intervention through changes in CSES scores (OR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.75 to 0.97) and MCAS scores (OR: 0.88; 95% CI: 0.74 to 0.98). These findings indicate a full mediation effect, where the intervention appears to reduce the occurrence of condomless anal sex by improving both condom use self-efficacy and attitudes toward condom use. Table 4 and Fig. 2 show the results of mediation analysis.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first self-paced, interactive, web-based intervention developed specifically for Chinese MSM dating app users. Our study found that the web-based intervention with interactive features could reduce the rate of condomless anal sex in the past three months among MSM currently using dating apps, and the effect of the intervention was significant at both 3-month and 6-month follow-ups. Additionally, there was a statistically significant reduction in the number of sex partners with whom participants had condomless anal sex from baseline to the 6-month follow-up within the intervention group. The intervention also significantly increased users’ self-efficacy and attitudes toward condom use, with effects significant from three to six months. Consistent with previous research23,25,32, our study provided further evidence of the effectiveness of web-based health interventions in prompting consistent condom use and enhancing sexual self-efficacy among Chinese MSM. Importantly, the findings from our mediation analysis offer compelling insights into the mechanisms by which our intervention influenced sexual behavior. The significant indirect effects through improved condom use self-efficacy and more positive attitudes toward condom use underscore the critical role of psychological factors in fostering consistent condom use. These findings align with the Theory of Planned Behavior, which suggests that behavioral change is often preceded by shifts in attitudes and perceived control over the behavior in question. The intervention’s ability to enhance condom self-efficacy and attitudes toward condom use was the key factor in reducing condomless anal sex among participants. This indicates that future interventions might benefit from placing a greater emphasis on these mediators to achieve a more substantial impact on sexual health outcomes.

However, it is important to acknowledge that some constructs related to the Theory of Planned Behavior, such as subjective norms and intention, were not measured in the current study. The absence of a psychometrically robust scale to measure subjective norms related to condom use in local contexts prevented their inclusion in this study. Consequently, there is a pressing need to develop a valid and reliable instrument for measuring these subjective norms. Furthermore, future studies should aim to incorporate measures of subjective norms, intentions to use condoms, and other factors such as perceived facilitation of condom use. Understanding how interventions influence these factors could lead to enhanced condom use and better sexual health outcomes. Additionally, condom use is a complex behavior involving many scenarios. Future studies should consider collecting more detailed information related to condom use, such as condom use during the last sexual encounter and the types of sex partners involved.

Our intervention is characterized by outstanding features, including co-designed intervention content, cultural specificity, highly interactive gamification elements, and flexibility in the timing of use. Given that condomless anal sex without PrEP is well-recognized to be associated with HIV/STI transmission20, the primary outcome of our intervention program was to increase consistent condom use. Unlike most health interventions developed exclusively by researchers or healthcare providers, our intervention was co-designed with the participation of MSM dating app users33, researchers, and healthcare providers. This co-design is reflected in the components of our interventions, which features a range of realistic yet tricky scenarios that may lead to potentially risky sexual behaviors, along with relevant educational content. Specifically, these scenarios were identified by incorporating real-life experiences from dating app-using participants and insights from front-line healthcare service providers. Our study is one of the few co-designed interventions that has shown significant effects on both reducing condomless sex behaviors and improving attitudes toward condom use. This is consistent with evidence from reviews that peer participation in sexual health interventions can simultaneously improve sexual behavior and attitudes34.

The highly interactive nature of our intervention is another novel and significant feature within the context of existing evidence. It has been documented that interactive interventions can provide personalized feedback and promote active learning23. In addition, web-based interventions have recognized advantages, such as being anonymous, repetitive, and convenient23. By combining these features, we incorporated interactive games into our intervention, introducing various real-life scenarios where different decisions would lead to different endings. In line with previous studies32,35, our results indicate that such interaction components yielded a significant effect on consistent condom use, suggesting that this interaction may help motivate situational reflection among MSM and, in turn, improve their actual condom use behavior. Furthermore, we paid special attention to user experience and user flexibility by not controlling participants’ engagement with the intervention, allowing them to maintain their self-pacing. The entire intervention was hosted on a website accessible from any device connected to the Internet. Most educational or informative pages were designed to be one page long, featuring graphical illustrations. As for the interactive game in the intervention group, the actual duration of each play depended on the participants’ engagement but typically lasted around 5–10 minutes.

In addition, despite the flexible time commitment required from the participants and the relatively low cost of this intervention, the effects of the intervention continued to be significant at the 3-month and 6-month follow-ups, indicating that the intervention has relatively good sustainability. In comparison to similar interactive web-based interventions designed to reduce condomless anal sex among MSM in Western countries32,36, which did not account for the use of dating apps among MSM, their intervention effects of promoting consistent condom use lasted only three months. In addition, their findings may not be generalizable to populations in Asia-Pacific countries due to differences in cultural contexts, such as Chinese culture, where homosexuality is still considered taboo. While the effect of our intervention in promoting condom adherence was sustained and remained significant in the sixth-month follow-up, longer-term effects were not tracked. This limitation warrants future research to examine the intervention’s impact over a longer period.

However, our intervention did not significantly reduce the rate of group sex and chemsex, nor did it have an effect on increasing the uptake of HIV and STI testing. The non-significant effects on these behavioral outcomes could be explained by the considerable reductions in individual sexual activities and the decrease in HIV/STI testing accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic37,38,39. Additionally, study dropouts engaged in chemsex behaviors at a significantly higher rate than those who completed all follow-ups, which could have influenced the intervention’s effect. Moreover, the lack of significant results related to group sex and chemsex may also be attributed to the baseline characteristics of the participants, as only 10.42% of our participants engaged in chemsex and 17.08% engaged in group sex. The low incidence of such behaviors might have limited the room for improvement through the intervention. Regarding HIV and other STI testing behaviors, our educational content recommends screening for HIV/STIs after any condomless sexual activities. However, the significantly improved consistent condom use, self-efficacy, as well as attitude among study participants, may have led them to perceive a reduced need for the testing. Drawing from successful practices in improving HIV testing, it is recommended that future interventions incorporate an HIV risk assessment tool and include timely reminders to facilitate testing behaviors in a more effective manner.

There are several limitations and implications for further studies. First, both the primary and secondary measures are self-reported, which may result in potential social desirability and recall bias. The use of anonymous web-based interventions may have encouraged a more open and trusting environment, thereby reducing the impact of such bias. Future collaboration with sexual health services could be considered to include more objective data from medical records, and in-depth interviews could also be supplemented to obtain more qualitative feedback. Second, dichotomous measures of behavioral outcomes may be less sensitive to change than continuous measures23. It would be more appropriate to collect data on the frequency of sexual behaviors when measuring behavior change. Third, although timely reminders were used to facilitate participants’ completion of the intervention, and those in the intervention group engaged in the interactive game at least once, this study did not capture participants’ actual use of the intervention, such as the frequency or duration of their visits, which may have impacted the effectiveness of the intervention32. This highlights the importance of future web-based interventions, adequately considering and recording specific digital engagement strategies, with detailed process evaluation recommended. Fourth, 28.78% (194/674) of eligible MSM declined to participate in this study during the recruitment process, which is similar to another local study targeting Hong Kong MSM27. However, as specific reasons for refusal were not recorded in this study, this may have resulted in a failure to reach those who are more vulnerable or have particular concerns. Further research should therefore document and analyze such reasons to improve the accessibility and generalizability of the intervention.

In addition, this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the incidence of sexual encounters and corresponding sexual behaviors appeared to be lower compared to the pre-pandemic period. Therefore, these findings cannot be generalized to the entire MSM population, and more research is needed to explore the post-pandemic situation. Lastly, although PrEP is still not readily accessible to the majority and remains costly in Hong Kong and mainland China, it is a crucial component of comprehensive HIV prevention. It is also worth noting that this study did not include HIV-positive or transgender populations, whose sexual safety is equally important. Therefore, a more comprehensive approach should be developed in the future to promote safer sex among a broader range of populations.

In conclusion, our study provides evidence for the effectiveness of a web-based interactive intervention in reducing condomless anal sex behaviors among MSM dating app users, with the effect being significant at the 3-month follow-up and lasting for six months. We also demonstrate that such an intervention can improve self-efficacy and attitudes toward condom use, with significant effects sustained at both three- and six-month follow-ups. The mechanistic analysis demonstrated that the intervention effectively decreased the occurrence of condomless anal sex by enhancing self-efficacy for condom use and fostering more favorable attitudes toward condom use. It is recommended that similar studies be customized for other regions in Asia, taking into account the diverse cultural, social, and healthcare landscapes across different regions. In the meantime, future online interventions could build on this by introducing more tailored components to promote specific behavioral changes.

Methods

Study design

This study was a two-arm, assessor-blinded, randomized, parallel-group trial with a 6-month follow-up period, conducted in Hong Kong from November 2020 to April 2022. The trial was registered on ISRCTN (ISRCTN16681863) on 28 April 2020, under the registry name “The safe use of dating applications (apps) among men who have sex with men: developing and testing an interactive web-based intervention to reduce risky sexual behaviours”. The trial protocol has been published40, and there were no important changes to the methods or study content after the trial commencement.

Participants

The study participants were enrolled using convenience sampling. Participants were eligible for inclusion in this study if they (i) were self-identified as cis male, (ii) were MSM who self-reported having ever had sexual contact with men, (iii) were aged 18 or above, (iv) were current dating app users, (v) were HIV-negative, (vi) had been sexually active in the last 12 months, and (vii) were able to read and understand Chinese. Sample size calculations were described in detail in the protocol40, and a total of 400 participants (200 in each group) was necessary to achieve 80% power at a 0.05 significance level. To recruit as many participants as possible from different sources, both online and offline recruitment methods were employed. These included direct recruitment via dating apps and mass university emails, and posting promotional materials with the help of social media and local non-governmental organizations targeting the MSM population.

Randomization and masking

Randomization was performed using a computer-generated block randomization procedure with a block size of 4 and a 1:1 randomization ratio. The computer-generated sequence was created by an independent programmer, who also developed an online platform that managed masking and allocation concealment. Participants were automatically assigned by the platform based on the randomization ratio only after they had successfully registered on the platform. All participants and research team members were blinded to the allocation sequence prior to assignment (i.e., allocation concealment). However, participants were not blinded after allocation, and blinding to group assignment was not feasible given the nature of the intervention. The research team was not blinded either. It is important to highlight that our eHealth intervention was self-paced, and the study questionnaires were self-administered. This setup minimized any direct interaction between participants and the research team regarding intervention content, thereby reducing the potential for bias introduced by the research team.

Procedures

Participants were screened for eligibility through an online screening questionnaire. Eligible participants were asked to sign an electronic consent form and use their email addresses to register for the study. After enrollment, the research team sent each participant a confirmation message and further instructions for participating in the study. After completing the baseline questionnaire, they were then randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group and were automatically guided to the web content corresponding to their allocation. In addition to instructions provided via pop-up messages when participants entered the platform, timely reminder messages from our trained research assistant were also sent to participants who did not complete the intervention content.

The intervention, named “Safe Fun Battle”, was designed to promote safer sex behaviors among Chinese MSM dating app users. Underpinned by the Theory of Planned Behavior41, the intervention consisted of interactive components and knowledge-based information about safer sex practices, including condom use, an introduction to different STIs, and guidance on how to get tested. The theory posits that all behaviors are influenced by an individual’s intentions, which are determined by attitudes, normative beliefs, and perceived control. Accordingly, we incorporated scenarios into the interactive game where personal beliefs and attitudes about sexual health primarily drive the decision-making process. For example, participants could choose whether to trust the negative HIV test results presented by a virtual partner and decide whether to go condomless in the game. Additionally, the intervention provided comprehensive information on safer sex and sexual health. Exposure to accurate knowledge was expected to raise awareness of potential risks, thereby enhancing participants’ perceived control over their sexual behaviors.

To better understand the needs and real-life experiences of MSM dating app users, we initially conducted an exploratory qualitative study involving thirty-one sexually active MSM dating app users33. Based on their usage of dating apps, specific sexual activities coordinated via these apps, and their experiences arranging sexual encounters, the research team designed three sets of tailored scenarios. The content of the intervention was also co-developed with local organizations offering community support and STI testing services to the MSM population. Specifically, the principal investigator of this study initially proposed some scenarios, after which all relevant stakeholders, working as a team, provided detailed suggestions based on their own experience or practices. Afterward, internal pilot tests were conducted within the team to confirm the appropriateness of the content, and unstructured discussions were held periodically. We continuously revised our intervention content until a final consensus was reached. Notably, the gamification elements and educational content designed for the intervention group were discussed and confirmed with front-line workers. By incorporating real-life examples collected from the qualitative interviews and practical insights from local community workers, the intervention aimed to improve participants’ perceived self-efficacy and decision-making skills related to condom use, negotiation and HIV/STI testing in real-life contexts.

Three sets of tailored scenarios were selected as the background for the games, including The Hotel Room, When Sex Encounters Drugs, and Cruising at the Sauna. In each storylines, participants were exposed to various situations illustrating the potential consequences of meeting sexual partners through dating apps, as well as the risks to sexual health during sexual encounters. They had to make virtual decisions in each context, with each action leading to a different ending for the stories. Depending on the player’s choices, there were 11 possible endings to the stories. The endings were tied to the content of the information pages. For example, if players chose to have condomless sex and were exposed to the risks of STI transmission, they were directed to the relevant information pages to learn more about safer sex practices, a good condom use guide, an introduction to different STIs, and how to get tested. There were also neutral endings where players made informed and safe decisions in every situation. In these cases, they were presented with general reminders for safe dating app usage42, highlighting the potential risk of sexual abuse associated with app use. This caution was based on a previous study that reported a higher incidence of sexual abuse among dating app users. In addition, participants were also presented with information related to chemsex, along with a list of local supporting organizations and the services they offer.

The control group was provided with brief information and educational materials from the online platform, which were not related to the intervention component on dating apps and safer sex. Participants were offered three information pages that provided an expanded description of sexual orientation, discrimination against sexual orientations, and disclosing one’s sexual orientation (coming out).

All participants were encouraged to review the content of their assigned group at their convenience throughout the study period in a self-paced manner. Every action on the study website would be recorded automatically and monitored daily by the research assistant. This allowed the research team to quickly check whether individual participants accessed different study components and to track their progress. Reminder messages were sent to the participants when it was time to complete the first (at 3 months post-enrollment) and second (at 6 months post-enrollment) follow-up surveys. In these messages, the participants were also reminded to complete any required study components they had not yet finished. The detailed flowchart is shown in Fig. 3.

When the participants registered for the intervention, they provided an email address or phone number for identification and verification. Each set of information could only be used once, and all registered participants could only access the content assigned to them. Participants had unlimited access to their respective content throughout the 6-month study period (Supplementary Note 1). Both groups completed self-administrated online assessments three times: at baseline, at 3 months (first follow-up), and 6 months after baseline (second follow-up). All study data were de-identified and strictly confidential, and only members of the research team were authorized to access them. The intention-to-treat principle was applied throughout the study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the frequency of condomless anal sex in the past 3 months, measured by asking participants how often they used a condom during different types of sex. Responses to this self-reported item ranged from “never” to “always”, with only “always” being considered consistent condom use. All other answers were considered inconsistent condom use. Secondary outcomes included five other behavioral outcomes and two psychological outcomes. Four secondary behavioral outcomes were measured in the same way as condom use, including the frequency of group sex, chemsex, HIV testing, and other STI testing behaviors in the past 3 months. These behavioral outcomes were analyzed as binary variables. Additionally, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the primary outcome, the number of sex partners with whom participants had condomless anal sex in the last 3 months was also recorded, though this metric was not mentioned in the published protocol40.

In addition, self-efficacy and attitude toward condom use were collected as psychological outcomes. Self-efficacy in condom use was measured by the validated traditional Chinese version of the Condom Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES)43, a 14-item instrument covering three domains: (1) consistent condom use, (2) correct condom use, and (3) condom use communication. Participants rated their responses on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very unsure) to 5 (very sure), with a total score ranging from 14 to 70. Higher scores indicated a higher level of condom use efficacy. The scale had good reliability in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.93.

Attitudes toward condom use were measured by the UCLA Multidimensional Condom Attitudes Scale (MCAS), which has been modified and validated in Hong Kong before44,45. It is a 23-item instrument covering six domains: (1) reliability and effectiveness, (2) excitement, (3) displeasure, (4) identity stigma, (5) embarrassment about negotiation, and (6) embarrassment about purchase. Participants rated their responses on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with a total score ranging from 23 to 161. Higher scores indicated a more positive attitude toward condom use. The scale had good reliability in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.90.

Finally, participants’ sociodemographic characteristics were also collected, including age, sexual orientation, relationship status, education level, employment status, and monthly personal income.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented to characterize the sociodemographics and study outcomes of the participants at each time point. Comparisons between participants who completed the study (non-dropouts) and those who did not (dropouts) were performed using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and independent samples t-tests for continuous variables. Generalized linear mixed-effects models with logit links were used to analyze binary outcomes (i.e.,: the practice of condomless anal sex, group sex, chemsex in the last three months, receiving HIV testing, and other STI testing in the last three months). Linear mixed-effects models were used to assess differential change in continuous outcomes (i.e.,: scores on the CSES and MCAS, as well as the number of sex partners with whom participants engaged in condomless anal sex in the past 3 months). Time, group, and the interaction between group and time were included as independent variables. The intention-to-treat principle was applied. These models could handle missing follow-up assessments without the need for imputation. The odds ratio (OR), mean difference, and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated. To investigate potential mediating effects, Hayes’ Process Model 4 was utilized for mediation analysis46. In this analysis, group allocation served as the independent variable, while changes in CSES and MCAS scores from baseline to the 6-month follow-up were mediators. The dependent variable of interest was the occurrence of condomless anal sex reported at the 6-month follow-up. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corporation). All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a statistical significance level of 5%.

Ethics consideration

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (HKU/HA HKW IRB), reference number: UW 18-152. Electronic informed consent was obtained from each study participant. The study reporting follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) ‐ EHEALTH checklist47 and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data availability

A more comprehensive abstract is detailed in the Supplementary Note 2. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article and additional, related documents are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Macapagal, K., Kraus, A., Moskowitz, D. A. & Birnholtz, J. Geosocial networking application use, characteristics of App-Met sexual partners, and sexual behavior among sexual and gender minority adolescents assigned male at birth. J. Sex. Res. 57, 1078–1087 (2020).

Choi, E. P., Wong, J. Y. & Fong, D. Y. The use of social networking applications of smartphone and associated sexual risks in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: a systematic review. AIDS Care 29, 145–155 (2017).

Zou, H. C. & Fan, S. Characteristics of men who have sex with men who use smartphone geosocial networking applications and implications for HIV interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 46, 885–894 (2017).

Wei, L. et al. Use of gay app and the associated HIV/syphilis risk among non-commercial men who have sex with men in Shenzhen, China: a serial cross-sectional study. Sex. Transm. Infect. 95, 496–504 (2019).

Chan, L. S. Ambivalence in networked intimacy: Observations from gay men using mobile dating apps. N. Media Soc. 20, 2566–2581 (2017).

Bowman, B. et al. Sexual Mixing and HIV Transmission Potential Among Greek Men Who have Sex with Men: Results from SOPHOCLES. AIDS Behav. 25, 1935–1945 (2021).

Ruan, Y. et al. Sexual mixing patterns among social networks of HIV-positive and HIV-negative Beijing men who have sex with men: a multilevel comparison using roundtable network mapping. AIDS Care 23, 1014–1025 (2011).

Choi, E. P. H. et al. The impacts of using smartphone dating applications on sexual risk behaviours in college students in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 11, e0165394 (2016).

Yeo, T. E. & Ng, Y. L. Sexual risk behaviors among apps-using young men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. AIDS Care 28, 314–318 (2016).

Anzani, A., Di Sarno, M. & Prunas, A. Using smartphone apps to find sexual partners: a review of the literature. Sexologies 27, e61–e65 (2018).

Holloway, I. W., Pulsipher, C. A., Gibbs, J., Barman-Adhikari, A. & Rice, E. Network influences on the sexual risk behaviors of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men using geosocial networking applications. AIDS Behav. 19, 112–122 (2015).

Marcus, J. L. & Snowden, J. M. Words Matter: Putting an End to “Unsafe” and “Risky” Sex. Sexually Transmitted Dis. 47, 1–3 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. HIV prevalence in China: integration of surveillance data and a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 955–963 (2013).

Tsuboi, M. et al. Prevalence of syphilis among men who have sex with men: a global systematic review and meta-analysis from 2000-20. Lancet Glob. Health 9, E1110–E1118 (2021).

Hillis, A., Germain, J., Hope, V., McVeigh, J. & Van Hout, M. C. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among men who have sex with men (MSM): a scoping review on PrEP service delivery and programming. Aids Behav. 24, 3056–3070 (2020).

Phanuphak, N. et al. Implementing a status-neutral approach to HIV in the Asia-Pacific. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 17, 422–430 (2020).

Xu, J., Tang, W., Zhang, F. & Shang, H. PrEP in China: choices are ahead. Lancet HIV 7, e155–e157 (2020).

Wang, H., Tang, W. & Shang, H. Expansion of PrEP and PEP services in China. Lancet HIV 9, e455–e457 (2022).

Wang, Z., Lau, J. T. F., Fang, Y., Ip, M. & Gross, D. L. Prevalence of actual uptake and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong, China. PLoS ONE 13, e0191671 (2018).

Wang, C. et al. Condom use social norms and self-efficacy with different kinds of male partners among Chinese men who have sex with men: results from an online survey. BMC Public Health 18, 1175 (2018).

Badal, H. J., Stryker, J. E., DeLuca, N. & Purcell, D. W. Swipe right: dating website and app use among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 22, 1265–1272 (2018).

Cao, B. et al. Social media interventions to promote HIV testing, linkage, adherence, and retention: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e394 (2017).

Bailey, J. V. et al. Interactive computer‐based interventions for sexual health promotion. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006483.pub2 (2010).

Knight, R., Karamouzian, M., Salway, T., Gilbert, M. & Shoveller, J. Online interventions to address HIV and other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections among young gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc 20. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25017 (2017).

Xin, M. et al. The effectiveness of electronic health interventions for promoting HIV-preventive behaviors among men who have sex with men: meta-analysis based on an integrative framework of design and implementation features. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e15977 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating efficacy of promoting a home-based HIV self-testing with online counseling on increasing HIV testing among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 22, 190–201 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. An Online Intervention Promoting HIV Testing Service Utilization Among Chinese men who have sex with men During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A quasi-experimental Study. AIDS Behav, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-04100-5 (2023).

Cheng, W. et al. Online HIV prevention intervention on condomless sex among men who have sex with men: a web-based randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 644 (2019).

Lau, J. T., Lau, M., Cheung, A. & Tsui, H. Y. A randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of an Internet-based intervention in reducing HIV risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. AIDS Care 20, 820–828 (2008).

Crutzen, R., Cyr, D. & de Vries, N. K. The role of user control in adherence to and knowledge gained from a website: randomized comparison between a tunneled version and a freedom-of-choice version. J. Med. Internet Res. 14, e45 (2012).

Choi, E. P. H. et al. The association between smartphone dating applications and college students’ casual sex encounters and condom use. Sex Reprod. Healthc. 9, 38–41 (2016).

Hightow-Weidman, L. B. et al. A randomized trial of an online risk reduction intervention for young black MSM. AIDS Behav. 23, 1166–1177 (2019).

Choi, K. W. Y. et al. The experience of using dating applications for sexual hook-ups: a qualitative exploration among HIV-negative men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. J. Sex Res. 1–10 https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1886227 (2021).

Sun, W. H., Miu, H. Y. H., Wong, C. K. H., Tucker, J. D. & Wong, W. C. W. Assessing participation and effectiveness of the peer-led approach in youth sexual health education: systematic review and meta-analysis in more developed countries. J. sex. Res. 55, 31–44 (2018).

Swanton, R., Allom, V. & Mullan, B. A meta-analysis of the effect of new-media interventions on sexual-health behaviours. Sex. Transm. Infect. 91, 14–20 (2015).

Rosser, B. R. et al. Reducing HIV risk behavior of men who have sex with men through persuasive computing: results of the Men’s INTernet Study-II. AIDS 24, 2099–2107 (2010).

Phillips, T. R. et al. Sexual health service adaptations to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Australia: a nationwide online survey. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 45, 622–627 (2021).

Starks, T. J. et al. Evaluating the impact of COVID-19: a cohort comparison study of drug use and risky sexual behavior among sexual minority men in the USA. Drug Alcohol Depend. 216, 108260 (2020).

Choi, E. P. H., Hui, B. P. H., Kwok, J. Y. Y. & Chow, E. P. F. Intimacy during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey examining the impact of COVID-19 on the sexual practices and dating app usage of people living in Hong Kong. Sex Health. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH22058 (2022).

Choi, E. P. H. et al. The safe use of dating applications among men who have sex with men: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial to evaluate an interactive web-based intervention to reduce risky sexual behaviours. BMC Public Health 20, 795 (2020).

Andrew, B. J. et al. Does the theory of planned behaviour explain condom use behaviour among men who have sex with men? A meta-analytic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 20, 2834–2844 (2016).

Choi, E. P. H., Wong, J. Y. H. & Fong, D. Y. T. An emerging risk factor of sexual abuse: the use of smartphone dating applications. Sex. abuse: J. Res. Treat. 30, 343–366 (2018).

Zhao, Y. et al. Translation and Validation of a Condom Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES) Chinese Version. AIDS Educ. Prev. 28, 499–510 (2016).

Helweg-Larsen, M. & Collins, B. E. The UCLA Multidimensional Condom Attitudes Scale: documenting the complex determinants of condom use in college students. Health Psychol. 13, 224–237 (1994).

Choi, E. P. H., Fong, D. Y. T. & Wong, J. Y. H. The use of the multidimensional condom attitude scale in Chinese young adults. Health Qual. life outcomes 18, 331 (2020).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis : a regression-based approach. Third edition. edn, (The Guilford Press, 2022).

Eysenbach, G. CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 13, e126 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (Early Career Scheme), reference number: 27607518. Eric Pui Fung Chow is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Investigator Grant (GNT1172873). The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Edmond Pui Hang Choi is the principal investigator and oversees the whole project. Edmond Pui Hang Choi designed the study and carried out the analysis. Chanchan Wu undertook the literature search and drafted the manuscript. Kitty Wai Ying Choi coordinated participant recruitment and data collection. Pui Hing Chau carried out the analysis. Edmond Pui Hang Choi, Chanchan Wu, Kitty Wai Ying Choi, Pui Hing Chau, Eric Yuk Fai Wan, William Chi Wai Wong, Janet Yuen Ha Wong, Daniel Yee Tak Fong, and Eric Pui Fung Chow provided critical input to the manuscript revision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, E.P.H., Wu, C., Choi, K.W.Y. et al. Ehealth interactive intervention in promoting safer sex among men who have sex with men. npj Digit. Med. 7, 313 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01313-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01313-3