Abstract

In this study, we review the application of digital technologies for health in China, examining the structure of its digital health governance. China’s digital health governance is of political commitment, cross-sectoral collaboration, and a comprehensive, all-encompassing approach that engages the entire society. However, the fragmentation of data remains a fundamental obstacle. The whole-of-society approach offers a valuable example for other low- and middle-income countries in promoting digital transformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of digital technologies for health presents a transformative opportunity to enhance health interventions and strengthen health systems1,2. The potential of digital transformation of a health system has emerged as an innovative and promising way for equitable access to meet diverse population health needs3,4,5. However, its implementation in low-resource settings necessitates a comprehensive and systematic approach and is contingent upon the establishment of a robust governance framework and the formulation of a coherent digital strategy. In the absence of robust governance, digital health systems may prove unable to adequately address health needs, priorities, and may lack transparency and accountability6,7. The Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–20258, proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO), has identified the strategic objective of “strengthening governance for digital health at global, regional, and national levels” as a key priority.

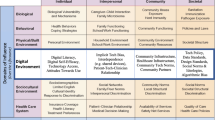

In China, the digital change in the health system has made big progress over the last 15 years, moving through three main stages: health care informatization (before 2010), big data-driven health care (2011–2019), and internet-based health care (after 2020). This progress has been supported by policies that encourage cooperation across sectors to create a governing ecosystem for the digital health system. However, these policies were often introduced in response to emerging issues at each stage, and a comprehensive analysis to understand the governance structure and actions is limited. To fill the research gap, this study aims to review the application of digital technologies for health in China, map the structure of its digital health governance based on the World Health Organization and International Telecommunication Union guideline on digital health governance9 (Fig. 1), and offer policy implications for promoting digital transformation of health particularly in source-limited settings.

The governance structure of digital health was displayed based on the World Health Organization and International Telecommunication Union guidelines on digital health governance, with the key elements including leadership and governance; strategy and investment; standards and interoperability; infrastructure; legislation, policy, and compliance; workforce; and service and applications.

Leadership and governance

To facilitate the digital transformation of the health system in China, a multi-tiered governing system has been gradually established, involving health and non-health government agencies, industry associations, and academic institutions.

At the governmental level, the State Council is responsible for the coordination of the overarching strategy for digital health development. The Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Promoting the Development of Internet Plus Health Care10 outlines 14 initiatives led by 12 ministries and commissions. The National Health Commission serves as the coordinating center in digital health governance, in collaboration with the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Finance, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, National Healthcare Security Administration, State Administration for Market Supervision and Administration, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, China Association for Science and Technology, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Public Security, and the State Office of Internet Governance11. This coordinated approach is designed to facilitate the advancement of the national digital health agenda across a diverse range of government functions and priorities.

Additionally, industry associations and academic institutions contribute to the governing ecosystem for digital health. For example, the Yinchuan Internet-based Health Care Association, constituted by the leaders of pertinent enterprises in the Yinchuan region of Ningxia province, represents the inaugural industry organization for digital health in China. The association has initiated the development of nine industry self-regulatory conventions, including the Internet Hospital Consultation List and Electronic Medical Record Basic Specifications, Internet Hospital Off-label Medication Management Specifications, and has played a pivotal role in the formulation of industry self-regulatory norms, the promotion of industry standards, the provision of industry services, and the organization of industry exchanges. The academy also made a contribution to the governance12. The National Center for Telemedicine and Internet Medicine, which was established in 2018, is dedicated to research in priority areas, including internet-based healthcare pricing, quality assurance, insurance system, and related management policies13. The results of these research projects provided valuable insights in shaping policies in digital health and contributed to the evidence base for governance in China’s rapidly evolving digital health landscape.

Strategy and investment

China’s digital health governance system is centered on three core functions that facilitate digital health transformation: health care informatization (before 2010), big data-driven health care (2011–2019), and internet-based health care (after 2020) (Fig. 2). The objective of this governance system is to strengthen the health system and provide support for the Healthy China 2030 Initiative14.

The digitization of health-related data has been a key part of the digital health transformation, with the relevant strategies being developed since 2002. This started with the publication of the Functional Specification of Hospital Information System15 by the Minister of Health, which provided guidance on the transition to electronic health record (EHR). Subsequently, a series of policies were proposed to guide the informatization of primary health care centers, hospitals, and public health facilities. In 2020, the Health Commission issued the Opinions on Strengthening the Construction of a Standardized System for Health Information for All16, which aimed to create a health information platform at the national, provincial, municipal, and county levels. This platform facilitates the exchange of health data across regions and health facilities, providing a dynamic EHR that incorporates health care, health insurance, and pharmaceutical data for each resident.

As advanced digital health technologies such as big data emerged, China began to assert its role in improving the health system, proposing targeted strategies for enhanced development and application. For example, the State Council issued the Guiding Opinions on Promoting and Regulating the Development of Big Data Applications in Healthcare17 in 2016, aimed at encouraging data sharing across different sectors and creating information systems. Big data has become a pivotal aspect in the optimization of health resource allocation, the facilitation of policy reform, and the provision of data-driven insights for decision-making processes. Big data is mainly used in governance, clinical research, public health, and intelligent medical devices, and could serve as the basis for drug monitoring and administration. The National Health Insurance Information Platform uses artificial intelligence to detect and stop fraudulent insurance claims, ensuring that health insurance funds are used safely and effectively.

The integration of people-centered health information and the increased need for online or remote health care during the pandemic has led to the emergence of internet-based health care, including teleconsultation, telemedicine, online consultation, and the purchase of drugs, as a key application scenario for digital health. The Chinese government takes internet-based health care as an important part of the digital industry. In 2018, the State Council published the Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Promoting the Development of Internet Plus Health Care10 which outlined a strategy to strengthen the internet-based health system, improve the supporting ecosystem, and enhance the supervision mechanism. This plan focused on providing diverse healthcare services, including medical services, public health services, general practice in primary health care, essential drug supply, health insurance services, health education, and artificial intelligence-based services. This showed the central government’s commitment to promoting technological advancement and organizational change to create an innovative delivery of healthcare services based on the Internet.

Standards and interoperability

In order to facilitate the effective sharing of digital health information and interoperability among data platforms and devices across health facilities, the National Health Commission set a plan in the 14th Five-Year Plan for health standardization18 in 2022, to optimize the national standardization system in alignment with the Standardization Law and other relevant regulations.

The Opinions on Strengthening the Construction of a Standardized System for Health Information for All16 have established standards for data integration across hospitals, primary health care centers, and public health facilities. That framework provided guidelines through the four key areas: medical record formats, disease classifications, surgical procedure coding, and standardized medical terminology. Currently, the key referenced standards include international standards such as the International Classification of Diseases, Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine, and Health Level Seven, along with national standards such as the Basic Dataset of Telemedicine Service19, the Basic Dataset of Electronic Medical Record20, and the Basic Dataset of Health Record for Residents21, which have been issued by the National Health Commission.

Regarding interoperability, technical specifications have been established for data exchange protocols, data collection interfaces, and network access standards. These include the National Community Medical Institutions Informatization Construction Standards and Norms22, the Technical Specification for Hospital Information Platform Based on EHR23, the National Hospitals Informatization Construction Standards and Norms24, and the Technical Specification for Telemedicine Information System25.

Infrastructure

The development of infrastructure is a fundamental prerequisite for digital transformation. The World Health Organization has identified four essential elements that needs to be considered: power supply, network connectivity, devices, and digital literacy. China has worked across sectors and making significant investments in infrastructure, creating a strong base for the digital transformation of its health system.

Latest data indicates that China achieved significant progress in its national reliable power supply level in 2023. According to the data from the 2023 Annual Report on National Power Reliability, urban power grids nationwide have a power supply reliability rate of 99.976%, and rural grids have reached 99.900%26. This reflects the efforts under the national rural revitalization strategy, which has worked to reduce the gap in power services between urban and rural areas. In addition to traditional power sources, renewable energy sources like hydropower, nuclear, wind, and solar energy have grown to ensure a sustainable and reliable power supply.

Following initiatives like the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Health Informatization27 and the Broadband China Strategy28, China has made expanding network infrastructure a priority. Efforts are being made to improve rural broadband, encourage telecom expansion, and lower network fees. By the third quarter of 2024, China had installed more than 4.042 million 5G base stations, accounting for 66% of global deployments and achieving 100% coverage in all prefecture-level cities and urban county areas29. This infrastructure not only supports widespread 5G use but also sets the stage for future 6 G technology, with international standards expected in 2025 and commercial rollout planned for 203030. Additionally, China’s IPv6 user base has grown to 822 million, making it the country with the largest IPv6 user population worldwide31. Although there has been progress in digital infrastructure, the urban-rural gap still exists. As of June 2024, internet access in rural China was at 63.8%, which is 21.5 percentage points lower than in urban areas32. Given China’s large population base, this gap is particularly pronounced. It primarily reflects the first level of the digital divide—issues related to access and infrastructure. The limited internet connectivity in rural areas not only directly restricts a substantial portion of the population from utilizing digital health platforms but also indirectly exacerbates the second and third levels of the digital divide, such as disparities in digital literacy and actual utilization.

To improve accessibility for the vulnerable aging population, age-appropriate devices like smartphones, televisions, speakers, and wearables have been introduced for older users, guided by the Internet Plus Action Guidance33, recognizing the significance of digital inclusion. The Digital Ageing in China initiative, which includes the Silver Ageing Digital Classroom, offers targeted training and resources, particularly for rural and underdeveloped areas. Over 300,000 on-site sessions have been conducted in communities, nursing homes, and senior universities, benefiting more than one million elderly individuals. Additionally, the “Information Accessibility” mini-program on WeChat provides online tutorials for over 360 apps, with more than 340,000 active learners34.

Legislation, policy, and compliance

The regulatory framework for digital healthcare in China began to take shape in 2010, reaching a significant peak with the issuance of key regulations in 2017 and 2018. These regulations, such as Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Promoting the Development of Internet Plus Health Care10, the Administrative Measures for Internet-based Diagnosis35, and the Administrative Measures for Internet-based Hospitals35, have been crucial in shaping the landscape for digital healthcare.

A major focus is data privacy and security. The Personal Information Protection Law of China36 designates health data as sensitive personal data, emphasizing the need for robust privacy protections37. Adopted on August 20, 2021, and effective from November 1, 2021, the law represents a substantial overhaul of China’s data protection framework38. Other pivotal regulations, including the Medical Practitioners Law39, the Detailed Rules for the Supervision of Internet Diagnosis and Treatment40, and the Regulation on the Administration of Medical Institutions41, reinforce patient privacy protection through regulatory oversight and punitive measures. EHR systems implement a variety of privacy protection strategies, including the classification of information according to confidentiality levels, a hierarchical management structure, access notifications, and anonymization. The National Health Commission, the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and regional health departments are responsible for regulating the use, supervision, and management of EHR systems, ensuring compliance with established privacy standards.

The effective functioning of digital health applications requires data exchange and integration across health facilities. Data Security Law42, Administrative Measures on Standards, Security and Services of National Health Big Data43, have provided detailed guidance on structuring data-sharing frameworks, establishing backup and recovery protocols, and auditing user activities, including data creation, modification, and deletion. In 2020, the Information Security Technology—Guide for Health Data Security44 was published by the State General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine, in collaboration with the National Standardization Administration. This document established protocols for secure data access and storage. Key stakeholders, including the National Health Commission, State Internet Information Office, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Public Security, and State Administration for Market Supervision and Administration, are responsible for maintaining data security and compliance within data systems.

While China’s digital health legislation has become more comprehensive in recent years, challenges persist. Scholars have pointed out several issues that remain unresolved. First, the responsibilities of law enforcement agencies are not clearly defined. Multiple agencies are involved in data protection, but their roles are often unclear, leading to inefficiencies in enforcement. Second, the Personal Information Protection Law of China has ambiguities in defining the scope and meaning of “health data” and “separate consent”38. Furthermore, a review of current legislation reveals that it is well-suited for traditional medical concerns, such as medical accidents, disputes, and the storage of electronic medical records. However, it does not adequately address newer challenges in digital healthcare, such as online diagnosis and treatment qualifications or the balancing of privacy protection with data sharing45. Additionally, while the tiered regulation system allows for local flexibility, it may lead to inconsistent standards and enforcement across different regions, ultimately undermining the uniformity and effectiveness of digital healthcare laws nationwide.

Workforce

The digital health workforce refers to the diverse group of individuals involved in the development, maintenance, utilization, and management of information and communication technology (ICT) systems in the healthcare sector. This includes not only technical personnel responsible for creating and maintaining digital health platforms but also healthcare professionals who use electronic systems in their everyday practice.

The Healthy China 2030 Initiative14, published in 2016, highlighted the importance of establishing a health university-based training cloud platform supported by massive open online courses (MOOCs). A study shows that the nursing students trained by MOOC have improved their clinical operation and theoretical knowledge compared to face-to-face teaching46. Similarly, a Tuberculosis Control Program’s E-learning project has demonstrated success by improving the clinical knowledge and quality of healthcare provided by tuberculosis health workers, expanding access to high-quality continuing education, and reducing the associated costs47,48. A survey on digital health education found that individuals who had taken digital health courses in college were more familiar with the terminology of digital health and more confident about the future integration into medical practice and research. A significant majority of respondents (87.24%) recognized the need to prepare for entering the digital health system, and over 90% expressed the need to acquire digital health knowledge and skills49.

Strengthening the workforce involves the implementation of degree programs and in-service training. In 2017, a policy50 was enacted to cultivate professionals with a broad skill set in the era of digital health, by encouraging vocational colleges and universities to establish degree programs in health management, intelligent older health care, and other related fields. For example, the Ministry of Education introduced new medical-related majors in 202351, including medical device and equipment engineering, gerontology, health insurance, pharmaceutical management, and biomedical data science. In-service training is primarily delivered through expert guidance and educational resources through network platforms, with the training focused on the utilization of EMR, implementing remote surgical teaching. These approaches ensure that healthcare workers are equipped with the knowledge and tools necessary to integrate digital technologies into their practice efficiently

Service and application

We conducted a systematic review to examine the current applications of digital health technology in China, identifying a total of 623 studies related to innovative digital health technologies (Fig. 3). A significant acceleration in the growth of these studies was noted starting in 2018. In terms of technological classification, more than half of the studies focused on telehealth systems, particularly those related to the point of service. Other prominent categories included communication systems, diagnostic information systems, and decision support systems.

A systematic review was conducted to measure the service and applications of innovative digital health technology in China. The temporal trend was estimated, and the types of the technologies were further classified according to the technologies, targeted diseases or conditions, and targeted prevention stages.

The innovative technologies were applied across a wide range of health areas, with a focus on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, followed by metabolic diseases, infectious diseases, cognitive and neurological disorders, cancer, and musculoskeletal disorders. Notably, over 70% of the technologies were developed for the treatment and prevention of diseases. Additionally, digital innovations targeting disease detection and rehabilitation, such as for stroke52 and depression53, were identified as key areas of progress. Emerging technologies, particularly 5 G and artificial intelligence, have been pivotal in advancing digital health. These innovations are expected to play a crucial role in driving the transformation of digital health by enhancing the accessibility of healthcare resources and facilitating the seamless flow of health information, thus fostering broader improvements in healthcare delivery and outcomes.

Discussion and recommendations

In the context of the global digital transformation, the health sector is receiving unprecedented attention. In order to advance digital health, the World Health Organization has launched a series of policies, including the Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–20258. This strategy places governance at the core, aiming to enhance the necessary capabilities and competencies for countries to advance, innovate, and disseminate digital health technologies, and ultimately contribute to universal health coverage. However, the implementation of these principles is deeply shaped by the specific local governance structures and contexts. This study analyzes China’s policies and practices, and maps the architecture of digital health governance within the country. Findings from this study offer valuable insights into governance structures that can facilitate digital transformation and could serve as an example for other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to navigate similar challenges in digital health transformation.

China’s governance structure for digital health is supported by political commitment, cross-sectoral collaboration, and a whole-of-society approach. The State Council has issued overarching strategies, including the Guiding Opinions on Promoting and Regulating the Development of Big Data Applications in Healthcare17 (2016) and the Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Promoting the Development of Internet Plus Health Care10 (2018). A multi-sectoral cooperation mechanism has been established, comprising 12 ministries and commissions, including those health-related sectors (e.g., the National Health Commission, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and National Healthcare Security Administration) as well as cross-cutting sectors that play a pivotal role in digital health functions. Moreover, academic institutions and private sectors like industry associations play an active role in governance, reinforcing a whole-of-society approach to digital health transformation. Their participation reinforces the whole-of-society approach to digital health transformation, ensuring that a broad range of stakeholders contribute to the ongoing development and regulation of digital health technologies. A key driver of this transformation is the development of digital and physical infrastructure—the first level of the digital divide. Disparities at this level create a cascading effect: limited internet access in rural areas not only hampers connectivity but also reduces digital literacy (second level) and limits the use of digital health services like telemedicine and remote monitoring (third level). This layered divide risks widening health disparities between urban and rural populations, highlighting an infrastructure gap in China that warrants attention for other LMICs.

Notwithstanding the progress, the fragmentation of data remains a foundational obstacle and has emerged as a priority for the next step. While informatization efforts began as early as 2002, the issue of “information silos” continues to hinder progress. The use of vertical, standalone ICT solutions has led to isolated systems that fail to communicate with one another, preventing access to the full spectrum of relevant health information. At the provincial level, efforts are being made to address these issues. For example, the Beijing Health Commission’s 2024 work plan prioritizes the integration of health data across a network of more than 170 hospitals in the city54. This approach is intended to connect various data sources and create a more unified system for healthcare information. Health insurance data is seen as a central element in this integration effort, serving as a crucial link that can connect healthcare service documents across different platforms. To further enhance data integration, a more comprehensive approach is needed. This would involve not only hospitals and healthcare centers but also primary care providers, public health programs, insurance reimbursement systems, and personal health data from wearable devices, to enable a more connected and efficient healthcare ecosystem to support better decision-making and health outcomes.

Motivating the data integration requires a strong focus on privacy protection and security55. Innovative solutions, such as privacy-preserving computing, have been proposed. Privacy-preserving computing, using technologies like secure multi-party computation, federated learning, and trusted execution environments, enables secure data sharing while maintaining privacy. These technologies allow computations on encrypted data, ensuring privacy during integration and analysis. Since 2023, the Suzhou Health Commission has developed a secure platform for medical data sharing, utilizing privacy-preserving technologies. The platform enables secure sharing of demographic data, EHRs, health knowledge, and public health records, enhancing data security, regulatory effectiveness, and healthcare standards56.

Policies gain significance only when effectively translated into practice. To evaluate the effectiveness of policy implementation across different regions, China has conducted the National Healthcare Information Standardization Maturity Measurement Program since 2020. This program evaluated the informatization capabilities of participating regions and hospitals through technical assessments23. Utilizing the National Health Informatization Development Index57, the program comprehensively measures cities across three key dimensions: governance capacity, infrastructure development, and application efficacy. The results highlight significant progress in China’s health informatization efforts, showcasing advancements in organizational frameworks, foundational infrastructure, and improved collaboration mechanisms among healthcare institutions. Moreover, the findings indicate increased maturity in data sharing and exchange, reflecting enhanced interoperability within the healthcare system.

Tailored governance models were observed across provinces and regions. In resource-rich areas, local health authorities build regional health information platforms through a bottom-up integration of medical data from all levels of healthcare institutions. Resource-scarce regions adopt a top-down approach, where large hospitals collaborate with a limited number of primary care facilities to provide support and foster regional medical cooperation58. For example, Zhejiang Province, which has the leading GDP per capita across China, focused on efficient healthcare services and life-course health management by utilizing digital platforms like Digital Health Angel, Zhejiang Medical Mutual Recognition, and Zhejiang Nursing59. Qinghai Province, located in the western part of China, addresses the accessibility challenges posed by its vast geographical landscape by offering telemedicine. This includes the establishment of a four-tier remote medical service system that connects provincial, municipal, county, and grassroots levels, thus improving healthcare access in the region60.

The adoption and utilization of healthcare providers and the general population are also essential for the digital transformation. To promote the utilization of healthcare providers, especially in low- and middle-income countries, it is critical to establish supportive infrastructure, provide tailored training, and implement incentive policies that foster a conducive environment for their adoption61. For the general public, while digital health technologies are becoming more common, there are still several challenges. These include issues with usability, concerns about security and privacy, a lack of industry standards, and various technical problems37,62. Further monitoring and evaluation are needed, from the perspective of digital health users, to further provide a supporting ecosystem for the digital transformation.

In the era of digital transformation, China’s governance structure and experience can offer useful lessons for other LMICs. Digital health has great potential to make health systems more efficient and sustainable. It can also help provide better care across different situations and for various population needs. However, many LMICs struggle with weak governance that does not align with the core Health for All values63. There is a need to move beyond the current focus on project-based, externally funded, and isolated efforts and instead drive digital transformation to build sustainable and integrated digital health systems. China’s experience highlights key elements for digital health governance: (1) a clear national strategy and a way to coordinate between government bodies and other groups; (2) basic infrastructure, such as power, network connections, devices, and digital skills; (3) strong focus on privacy and data security through laws and new technology; (4) training programs to improve digital skills for healthcare workers and vulnerable groups; and (5) strategies that are adapted to the local situation and development stage. It is important to understand that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach for digital health governance. Each country will need a tailored structure and strategy, based on its health system, government, and the role of the private sector.

In summary, this study systematically examined digital health governance in China, and highlighted policy arrangements, implementations, challenges, and the path forward. The whole-of-society approach to digital transformation in health systems offers a valuable example and policy insights for other LMICs in promoting digital transformation based on the Health for All values and adapting to local contexts.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Sheikh, A.et al.Health information technology and digital innovation for national learning health and care systems. Lancet Digit. Health3, e383–e396 (2021).

Kickbusch, I.et al.The Lancet and Financial Times Commission on governing health futures 2030: growing up in a digital world. Lancet 398, 1727–1776 (2021).

Xiong, S.et al. Digital health interventions for non-communicable disease management in primary health care in low-and middle-income countries. NPJ Digit. Med.6, 12 (2023).

Bond, R. R. et al. Digital transformation of mental health services. Npj Ment. Health Res. 2, 13 (2023).

Gunasekeran, D. V., Tseng, R., Tham, Y. C. & Wong, T. Y. Applications of digital health for public health responses to COVID-19: a systematic scoping review of artificial intelligence, telehealth and related technologies. NPJ Digit. Med. 4, 40 (2021).

WHO. Digital health platform handbook: building a digital information infrastructure (infostructure) for health. (2020).

Tiffin, N., George, A. & LeFevre, A. E. How to use relevant data for maximal benefit with minimal risk: digital health data governance to protect vulnerable populations in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 4, e001395 (2019).

WHO. Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025 (2021).

International Telecommunication Union & WHO. National eHealth strategy toolkit (2012).

General Office of the State Council of PRC. Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Promoting the Development of Internet Plus Health Care. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2018-04/28/content_5286645.htm (2018).

Yang, F., Shu, H. & Zhang, X. Understanding “Internet Plus Healthcare” in China: policy text analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e23779 (2021).

National Standardization Management Platform. The Yinchuan Internet-based Health Care Association. https://www.ttbz.org.cn/OrganManage/Detail/4693 (2022).

Office of Hospital Development and Telemedicine Center. The National Centre for Telemedicine and Internet Medicine. https://www.zryhyy.com.cn/zryhyyhlw/c104280/202202/8f4a3d7c37144dfcb8f12a028a4b22fd.shtml (2022).

the CPC Central Committee, the State Council of PRC. Healthy China 2030 Initiative. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2016-10/25/content_5124174.htm (2016).

Minister of Health of PRC. Functional Specification of Hospital Information System. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/zcjd/201304/96d8f6b4aa39478fbe8e3ab23cb44461.shtml (2002).

National Health Commission of PRC. Opinions on Strengthening the Construction of a Standardized System for Health Information for All. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/cms-search/xxgk/getManuscriptXxgk.htm?id=4114443b613546148b275f191da4662b (2020).

General Office of the State Council of PRC. Guiding Opinions on Promoting and Regulating the Development of Big Data Applications in Healthcare. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-06/24/content_5085091.htm (2016).

National Health Commission of PRC. 14th Five-Year Plan for health standardization. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-01/27/content_5670684.htm (2022).

National Health Commission of PRC. Basic Dataset of Telemedicine Service. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/mohwsbwstjxxzx/s8553/201708/dbecdd253dd8473a9c951a6fb30e1a6e.shtml (2017).

National Health Commission of PRC. Basic Dataset of Electronic Medical Record. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fzs/s7852d/201406/a14c0b813b844c9dbd113f126fa9cb17.shtml (2014).

National Health Commission of PRC. Basic Dataset of Health Record for Residents. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fzs/s7852d/201108/05095b1b337d4576b3a1ac4d2094b21a.shtml (2011).

National Health Commission of PRC, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of PRC. National Community Medical Institutions Informatization Construction Standards and Norms. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2019-09/16/content_5430265.htm (2019).

National Health Commission of PRC. Technical Specification for Hospital Information Platform Based on EHR. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fzs/s7852d/201406/a14c0b813b844c9dbd113f126fa9cb17.shtml (2014).

National Health Commission of PRC. National Hospitals Informatization Construction Standards and Norms. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/gongwen12/201804/5711872560ad4866a8f500814dcd7ddd.shtml (2018).

National Health Commission of PRC. Technical Specification for Telemedicine Information System. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/mohwsbwstjxxzx/s8553/201708/dbecdd253dd8473a9c951a6fb30e1a6e.shtml (2017).

National Energy Administration, C. E. C. 2023 Annual Report on National Power Reliability. https://prpq.nea.gov.cn/uploads/file1/20240701/668226d2c7c0f.pdf (2024).

National Health Commission of PRC, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of PRC, National Disease Control and Prevention Administration of PRC. 14th Five-Year Plan for National Health Informatization. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s3585u/202211/49eb570ca79a42f688f9efac42e3c0f1.shtml (2022).

The State Council of PRC. State Council’s Notice on Issuing the “Broadband China” Strategy and Implementation Plan. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2013/content_2473876.htm (2013).

Beijing TD Industry Alliance. 5G Industry and Market Development Report(Q3). https://www.docin.com/p-4764488846.html (2024).

IMT-2030(6G) Promotion Group. 6G Vision and Potential Key Technologies White Paper. https://www.xdyanbao.com/doc/lpj8c1bemk?userid=57555079&bd_vid=15883747879748192676 (2021).

Global IPv6 Forum, China Next Generation Internet Engineering Center. 2024 Global IPv6 Support Degree White Paper. https://www.ipv6testingcenter.com/uploads/file/2024%E5%85%A8%E7%90%83IPv6%E6%94%AF%E6%8C%81%E5%BA%A6%E7%99%BD%E7%9A%AE%E4%B9%A6%E4%B8%AD%E6%96%87.pdf (2025).

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). The 54th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development. 15 (2024).

The State Council of PRC. State Council’s Guiding Opinions on Actively Promoting the “Internet Plus” Action. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2015-07/04/content_10002.htm (2015).

China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT). Digital Technology Gerontechnology Development Report (2024). 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 (2024).

National Health Commission of PRC, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of PRC. Notification from the National Health Commission and the Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine on the Issuance of the Interim Measures for Internet-based Medical Diagnosis and Treatment and Two Other Documents. https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2019/content_5358684.htm (2018).

The NPC Standing Committee. Personal Information Protection Law of China. https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail2.html?ZmY4MDgxODE3YjY0NzJhMzAxN2I2NTZjYzIwNDAwNDQ%3D (2021).

Calzada, I. Citizens’ Data Privacy in China: The State of the Art of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL). Smart Cities 5, 1129–1150 (2022).

He, Z. When data protection norms meet digital health technology: China’s regulatory approaches to health data protection. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 47, 105758 (2022).

The NPC Standing Committee. Medical Practitioners Law. https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail2.html?ZmY4MDgxODE3YjY0NTBlNjAxN2I2NTdiYTk1MDAxMTY%3D (2021).

National Health Commission of PRC, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of PRC. Detailed Rules for the Supervision of Internet Diagnosis and Treatment. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s3594q/202203/fa87807fa6e1411e9afeb82a4211f287.shtml (2022).

The State Council of PRC. Regulation on the Administration of Medical Institutions. https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail2.html?ZmY4MDgxODE4MGUwYTYxMzAxODExZTMzYWNlNzFlZjI%3D (2022).

The NPC Standing Committee. Data Security Law. https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail2.html?ZmY4MDgxODE3OWY1ZTA4MDAxNzlmODg1YzdlNzAzOTI%3D (2021).

National Health Commission of PRC. Administrative Measures on Standards, Security and Services of National Health Big Data. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/mohwsbwstjxxzx/s8553/201809/f346909ef17e41499ab766890a34bff7.shtml (2018).

State Administration for Market Regulation, National Standardization Administration. Information Security Technology—Guide for Health Data Security. https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=239351905E7B62A7DF537856738247CE (2020).

Zhao, B. & Feng, Y. Mapping the development of China’s data protection law: major actors, core values, and shifting power relations. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 40, 105498 (2021).

Cao, W. et al. Massive open online courses-based blended versus face-to-face classroom teaching methods for fundamental nursing course. Medicines 100, e24829 (2021).

Wang, Z. Y. et al. The effectiveness of E-learning in continuing medical education for tuberculosis health workers: a quasi-experiment from China. Infect. Dis. Poverty 10, 72 (2021).

Wang, Z. Y. et al. Process evaluation of E-learning in continuing medical education: evidence from the China-Gates Foundation Tuberculosis Control Program. Infect. Dis. Poverty 10, 23 (2021).

Ma, M. et al. The need for digital health education among next-generation health workers in China: a cross-sectional survey on digital health education. BMC Med. Educ. 23, 541 (2023).

National Health and Family Planning Commission of PRC, Ministry of Finance of PRC, National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Notice on Issuing the 13th Five-Year Plan National Training Program for Health and Family Planning Professionals. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/qjjys/s3593/201705/64deeb7370b74f7180221964e68fe5a7.shtml (2017).

The General Office of the Ministry of Education of PRC. Notice on Issuing the Guiding Specialty Directory for Talent Development in Health Services and Health Industry. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202401/content_6924809.htm (2023).

Fatehi, V., Salahzadeh, Z. & Mohammadzadeh, Z. Mapping and analyzing the application of digital health for stroke rehabilitation: scientometric analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 20, 321–330 (2025).

Plessen, C. Y., Panagiotopoulou, O. M., Tong, L., Cuijpers, P. & Karyotaki, E. Digital mental health interventions for the treatment of depression: a multiverse meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 369, 1031–1044 (2025).

Beijing Municipal Health Commission. Beijing Municipal Health Commission’s Notice on Issuing the Beijing 2024 Plan for Improving Medical Services. https://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/gfxwj/202403/t20240321_3596305.html (2024).

Yao, Y. & Yang, F. Overcoming personal information protection challenges involving real-world data to support public health efforts in China. Front. Public Health 11, 1265050 (2023).

NSFOCUS. Privacy Computing White Paper on Its Application in the Fields of Science, Education, and Health. https://book.yunzhan365.com/tkgd/qrrb/mobile/index.html (2023).

National Health Commission. National Health Information Development Index. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/mohwsbwstjxxzx/s8561/202304/3aff99e9527540bc8b5b387f86d184b6.shtml (2023).

Huang, M., Wang, J., Nicholas, S., Maitland, E. & Guo, Z. Development, status quo, and challenges to China’s health informatization during COVID-19: evaluation and recommendations. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e27345 (2021).

Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission. Digital Transformation in Health and Wellness Yields Rich Results in Zhejiang Province. http://www.zj.xinhuanet.com/20241209/fd3ef312fe6b417a8cf27be20b64b7dc/c.html (2024).

Qinghai Daily. “Internet +” Brings Smart Healthcare from the Cloud to Reality. http://www.qhio.gov.cn/system/2024/08/10/030255236.shtml (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Health workers’ adoption of digital health technology in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull. World Health Organ. 103, 126–135f (2025).

Pan, J., Ding, S., Wu, D., Yang, S. & Yang, J. Exploring behavioural intentions toward smart healthcare services among medical practitioners: a technology transfer perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 57, 5801–5820 (2019).

Gotsadze, G., Zoidze, A., Gabunia, T. & Chin, B. Advancing governance for digital transformation in health: insights from Georgia’s experience. BMJ Glob. Health https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2024-015589 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72274005 and 72304013), and Beijing Nova Program (20230484284). The study sponsor had no role in the study design, data analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the paper, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors helped develop the study concept and design. M.W. contributed to the statistical analysis and manuscript writing. XR.L., Y.D., Z.L., XN.L., X.Z., and J.W. contributed to the information screening and analysis. M.R. provided technical guidance on the data interpretation. Y.J. provided overall guidance and critical revision. All authors revised the paper and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, M., Lu, X., Du, Y. et al. Digital health governance in China by a whole-of-society approach. npj Digit. Med. 8, 496 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01876-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01876-9