Abstract

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive motor neuron degeneration, leading to paralysis and respiratory failure. Current therapies offer limited benefits, highlighting the need for novel therapeutic strategies. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) and CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing hold promise, but their effective delivery to the central nervous system (CNS) remains a significant challenge. Here, a potential approach involves utilizing engineered Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) as a self-replicating nanocarrier for targeted ASO delivery to motor neurons. By leveraging JEV’s natural neurotropism and “Trojan horse” mechanism of immune cell-mediated CNS entry, this strategy overcomes the blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barriers (BBB/BSCB). Incorporation of ASO sequences within the JEV genome facilitates co-packaging and sustained therapeutic delivery, while microRNA (miRNA)-mediated attenuation may enhance safety and CNS specificity. This theoretical framework offers a potential paradigm shift in CNS gene therapy for ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases by enabling efficient, targeted, and sustained ASO delivery. However, experimental validation remains critical to assess its safety and therapeutic efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

ALS is a devastating neurodegenerative disease characterized by the progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons, resulting in muscle weakness, paralysis, and eventual respiratory failure. The disease typically begins focally and advances along neuroanatomical pathways, with a median survival of 3–5 years following symptom onset1,2. While ALS is primarily classified as a motor neuron disease, clinical heterogeneity is common. Up to 50% of patients experience non-motor symptoms, including cognitive impairments, executive dysfunction, and frontotemporal dementia1. This spectrum of manifestations complicates diagnosis and highlights the multifactorial nature of disease progression.

The global ALS incidence ranges from 0.6 to 3.8 cases per 100,000 person-years, with notably higher prevalence observed in European populations (2–4 cases per 100,000 person-years)3. The disease is broadly categorized into familial ALS (fALS) and sporadic ALS (sALS). fALS, often inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, accounts for 10–15% of cases, while the remaining majority are classified as sporadic4. To date, mutations in over 40 genes have been associated with ALS pathogenesis5,6. These include superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), TAR DNA-binding protein of 43 (TDP-43), fused in sarcoma (FUS), TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), and chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72)2,5,6. Mutations in these genes often lead to the formation of toxic protein aggregates, compromising motor neuron function. Of particular relevance is the hexanucleotide repeat expansion (HRE) in C9orf72, which accounts for 30–50% of fALS and 7% of sALS cases, with a pronounced prevalence in European populations1. SOD1 mutations, the second most common genetic contributor to fALS in Europe (14.8% prevalence)7, promote the formation of cytotoxic SOD1 aggregates that compromise the function of astrocytes and motor neurons7,8. While SOD1 mutations are detected in only 2% of all ALS cases, they remain a vital focus due to their defined molecular pathology and therapeutic tractability9,10. Importantly, the prevalence of ALS-associated mutations varies substantially across ethnic and geographic populations11, emphasizing the necessity of global context in both research and treatment design.

Despite advances in genetic characterization, the molecular mechanisms driving ALS remain incompletely understood. The disease is multifactorial, involving several interconnected mechanisms. A prominent hallmark of ALS is neuroinflammation, predominantly driven by activated microglia and astrocytes. These glial cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β), exacerbating motor neuron degeneration12,13. Additionally, the activation of Type I and Type II interferons (IFN-I and IFN-II) observed in ALS models underscores their contribution to sustained inflammatory responses14,15,16,17. Recent evidence has implicated the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) pathway, a sensor of cytosolic DNA that subsequently induces IFN responses, in ALS pathology, particularly in the context of SOD1- and TDP-43-driven neuroinflammation14,15,16. Moreover, infiltration of peripheral T cells into the CNS further suggests immune dysregulation contributing to disease progression18. Another defining feature of ALS pathology is protein aggregation, wherein misfolded SOD1, TDP-43, and FUS proteins form intracellular aggregates that disrupt normal cellular function19,20,21. Notably, TDP-43 pathology, characterized by cytoplasmic mislocalization and aggregation, is nearly ubiquitous in sALS, resulting in both loss-of-function and toxic gain-of-function effects22. These aggregates also exhibit prion-like properties, enabling cell-to-cell propagation that amplifies neurodegeneration19,20,21. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction constitute additional critical pathological features in ALS. Mutant SOD1 and TDP-43 proteins induce mitochondrial fragmentation, impairing energy production and elevating reactive oxygen species. The damaged mitochondria not only compromise cellular energy metabolism but also perpetuates neuroinflammation by releasing mitochondrial DNA and RNA:DNA hybrids into the cytosol, further activating the cGAS-STING pathway and driving chronic neuroinflammation14,15.

RNA dysregulation also plays a significant role in ALS pathogenesis. Mutations in RNA-binding proteins, including TDP-43, FUS, and the C9orf72 repeat expansion, disrupt normal RNA metabolism23,24,25. Specifically, C9orf72 expansions generate toxic RNA foci and dipeptide repeat proteins, leading to cellular toxicity. Persistent aggregation of RNA-binding proteins and aberrant stress granule formation further aggravate neuronal dysfunction25,26,27. While fALS is largely driven by genetic mutations, sALS, which accounts for the majority of cases, is thought to arise from a combination of environmental exposures, aging, and cellular stress28,29,30. Potential triggers include viral infections [e.g., enteroviruses such as coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3), and rabies virus], which may induce neuroinflammation and protein mislocalization31,32,33; exposure to toxins and heavy metals such as pesticides, lead, mercury, and β-N-methylamino-L-alanine34,35,36; and physical trauma or intense exercise, which could heighten ALS risk through chronic inflammation37,38,39. Understanding these diverse mechanisms is essential for developing targeted therapies that address the underlying causes of ALS rather than merely alleviating symptoms.

Currently, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved therapies, including riluzole, edaravone, and sodium phenylbutyrate–taurursodiol offer only modest benefits in slowing disease progression40. In parallel, a pharmacological approach using ultrahigh-dose methylcobalamin has shown encouraging results in early-stage ALS. In a large multicenter phase 3 trial, intramuscular administration of 50 mg methylcobalamin twice weekly significantly slowed ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R) decline over 16 weeks, with a favorable safety profile41. Notably, patients who received methylcobalamin alongside riluzole demonstrated greater functional preservation, suggesting a synergistic interaction. Biochemical evidence, including reductions in plasma homocysteine and modulation of oxidative stress and excitotoxicity pathways, further supports methylcobalamin’s role as a mechanistically grounded adjunctive therapy41. These findings emphasize the importance of early, stratified intervention and broaden the therapeutic framework for ALS to include both symptomatic and disease-modifying modalities. Alongside pharmacological advances, molecular therapies targeting genetic drivers of ALS are gaining momentum. ASO, and CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing have emerged as promising strategies. ASOs are synthetic, single-stranded nucleotides (3∼15 kDa) engineered to selectively bind and degrade mutant mRNA, thereby modulating pathogenic gene expression42,43,44. In 2023, tofersen became the first FDA-approved ASO for ALS, specifically targeting SOD1 mRNA45. Administered via intrathecal injection (delivery into the spinal cord), tofersen reduces toxic SOD1 protein levels and biomarkers like neurofilament light chain in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)9,45. This direct CNS-delivery bypasses the limitations of BBB and BSCB, which block over 90% of small molecules and essentially all large biologics (e.g., siRNAs, DNA, unmodified ASO)46,47,48. To enhance ASO bioavailability and reduce immune activation, modern designs incorporate chemical modifications (e.g., 2′-O-methoxyethyl) that improve stability and reduce Toll-like receptor and CpG-mediated responses49,50,51. Despite an overall favorable safety profile, occasional adverse events such as mild myelitis have been reported52, highlighting the need for optimized delivery and dosing strategies. Encouragingly, well-designed ASO displays high sequence specificity with minimal off-target effects. For instance, tofersen has effectively reduced toxic SOD1 protein aggregates responsible for motor neuron degeneration and progressive muscle weakness8,53. Clinical trials evaluating intrathecally administered tofersen in ALS patients with SOD1 mutations (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT02623699 and NCT03070119)9,54,55,56, and ongoing studies are investigating its potential in delaying ALS onset in presymptomatic adult SOD1 mutation carriers (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04856982). A summary of current FDA-approved ALS therapies and investigational agents under clinical evaluation, including trial phases, routes of administration, and molecular targets, is provided in Table 1.

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing offers a complementary approach by directly correcting genetic mutations. Guided by single-guide RNA (sgRNA), CRISPR/Cas9 enables precise excision of mutated SOD1 genes, preventing the production of toxic proteins implicated in ALS pathophysiology57,58,59. CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing provides a route to permanently inactivate or correct ALS-linked mutations, with recent studies addressing critical delivery and specificity challenges. A 2020 study in SOD1-mutant ALS mice used base-editing Cas9 to introduce a stop codon, significantly prolonging survival60. Preclinical studies of CRISPR/Cas9-based therapy have demonstrated extended survival and delayed disease progression in G93A-SOD1 mouse models; however, clinical trials in ALS patients have yet to commence. Translating CRISPR technology to clinical settings requires rigorous control of precision and safety, as double-strand breaks from Cas9 can induce off-target mutations or large genomic rearrangements. This emphasizes the importance of high-fidelity guide design and alternative editing strategies such as base editors or prime editors that minimize DNA breaks59. Another challenge is Cas9 immunogenicity, given its bacterial origin, potentially triggering immune responses that clear edited cells or cause inflammation61. To mitigate this, researchers are exploring transient delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNP) rather than DNA vectors. For instance, virus-like nanoparticles (VLP) loaded with Cas9 RNP have successfully enabled in vivo genome editing in retina, liver, and brain tissues without persistent Cas9 expression62,63. By focusing on precision (to avoid off-target effects) and novel delivery mechanisms (to overcome size and immune barriers), CRISPR-based therapies are rapidly evolving toward safe and effective clinical application in ALS.

Despite their potential, effective CNS delivery of ASO and CRISPR-based therapies remains a formidable challenge. Conventional delivery methods, such as intrathecal injections and viral vectors, are limited by their invasiveness, transient efficacy, and poor BBB/BSCB penetration. To address these barriers, we propose an innovative strategy that integrates therapeutic ASO into the genome of positive-strand RNA viruses, specifically the JEV. By embedding ASO within the viral genome, the approach enables co-packaging with viral RNA, facilitating a self-replicating and CNS-targeted delivery system. Leveraging JEV’s intrinsic neurotropism and its capacity to cross BBB/BSCB barriers through immune cell-mediated pathways, this framework could transform ALS therapy and have broader applications for other neurodegenerative diseases. Although currently theoretical, this model demands rigorous experimental validation to ascertain its feasibility, safety, and therapeutic potential.

Nanotechnological innovations for overcoming CNS delivery barriers

Significant progress in ASO and CRISPR/Cas9 technologies has been tempered by challenges in translating these tools into effective ALS therapies, including poor in vivo stability, off-target effects, immunogenicity64,65, and restricted distribution across the BBB and BSCB. These barriers serve as selective interfaces regulating molecular exchange between systemic circulation and the CNS, thus restricting access of therapeutics to the affected upper and lower motor neurons. The BBB consists of a complex network of brain microvascular endothelial cells, neurons, microglial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes, interconnected by glycocalyx layers and tight junctions. Although morphologically similar to the BBB, the BSCB has comparatively lower expression of tight junction proteins and P-glycoprotein transporters66, potentially offering a less restrictive route for drug delivery. Furthermore, the glymphatic system, responsible for waste clearance from interstitial solutes and CSF circulation, interacts closely with BBB transport mechanisms to influence CNS homeostasis and therapeutic efficacy. Overcoming these obstacles requires innovative delivery strategies addressing the shortcomings of existing delivery routes67. For example, systemic intravenous administration results in rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system, as observed with edaravone and investigational treatments like AP-101 and tegoprubart (AT-1501)68. On the other hand, intrathecal administration, as used with tofersen55 and NurOwn69, provides direct CNS access but remains invasive with potential procedural complications. Alternatively, non-invasive intranasal delivery is impeded by mucociliary clearance mechanisms, significantly restricting consistent CNS drug delivery.

Nanotechnology is driving innovative solutions to surmount the BBB/BSCB and enhance CNS drug bioavailability. Nanoparticle (NP) carriers offer versatile platforms for protecting therapeutic molecules, including DNA, and RNA from degradation while facilitating their transport across physiological barriers70. Functionalized NP, engineered with surface ligands such as peptides and antibodies to target transport receptors on BBB endothelial cells, enhance transcellular transit, prolong systemic circulation, and provide controlled cargo release70. Recent studies demonstrate these advantages: Chen et al. developed calcium phosphate lipid NP to deliver SOD1-targeting ASO to motor neurons, achieving effective gene silencing in an ALS model without the immunogenic risks associated with viral vectors71. These nanocarriers elicited minimal immune clearance and exhibited excellent tolerability61,71. In parallel, ligand-functionalized NP have been effectively validated in Alzheimer’s models, where NP decorated with BBB-targeting peptides and neuron-specific ligands successfully crossed into the brain and accumulated at disease sites72. A single systemic administration of these nanocomplexes effectively knocked down the pathogenic gene (BACE1) and mitigated neuropathology in mice72. Interestingly, a metabolically responsive nanocarrier featuring a precisely engineered surface glucose configuration was recently developed to enhance brain accumulation following systemic administration73. This strategy leveraged transient glycemic spikes, induced by fasting, to promote glucose transporter-1 translocation across endothelial cells of the BBB, thereby facilitating transcytosis into the CNS. Modulating the glucose density on the nanocarrier surface enabled fine control over its biodistribution, with preferential accumulation observed in neuronal populations. These findings highlight the potential of ligand-directed, metabolically activated nanocarriers as a promising approach for achieving selective, efficient, and minimally invasive CNS delivery73.

Additionally, natural nanocarriers, including exosomes and cell membrane-camouflaged NP, demonstrate intrinsic BBB-crossing capabilities coupled with exceptional biocompatibility and minimal immunogenicity74,75,76. Engineered exosomes expressing neuron-specific rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) peptides, such as LAMP2B, have been effectively utilized for brain-targeted siRNA delivery77. Exosome-based NP, being cell-derived vesicles, offer exceptional biocompatibility and negligible immunogenicity, making them suitable for repeated administration. Exosomes from engineered stem cells can be loaded with therapeutic siRNAs or proteins77,78, demonstrating the ability to navigate across the BBB and modulate neuroinflammatory responses in animal models, which is particularly relevant for neurodegenerative diseases like ALS. Similarly, lipid-based NP leverage their hydrophobic characteristics to traverse the BBB and enhance drug absorption. Solid lipid NP have significantly enhanced riluzole delivery in vivo79, while riluzole nanoemulsion administered intranasally bypasses BBB constraints, thereby increasing CNS bioavailability and reducing systemic toxicity80. Advanced surface modifications of the nanocarrier further enhance CNS targeting and therapeutic bioavailability. Ligand-functionalized NP actively engage specific receptors abundantly expressed on endothelial cells and neurons, such as low-density lipoprotein receptor, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), transferrin receptor, and lactoferrin receptor81,82. Angiopep-2, a 19-amino acid oligopeptide, enhances BBB penetration via LRP1-mediated transcytosis83,84, with Angiopep-2-derived conjugates such as ANG-1005 and PepFect 32 facilitating receptor-mediated BBB crossing85,86,87. Similarly, natural ligand-functionalized NP employing apolipoprotein, transferrin, and lactoferrin significantly enhance CNS targeting through receptor-mediated transport across brain endothelial cells88,89,90,91.

Emerging approaches that integrate nanocarriers with technologies such as focused ultrasound (F.US) or convection-enhanced delivery (CED) further augment CNS drug delivery by transiently disrupting the BBB. F.US, in particular, has shown versatility in facilitating the delivery of therapeutic agents to the brain. For example, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-liposomes loaded with glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor plasmids have shown efficacy in a Parkinson’s disease model when administered in conjunction with microbubble-mediated F.US92. Similarly, a recent study employed calcium phosphate lipid NP to systemically deliver the SOD1 ASO tofersen to the brain in ALS mouse models, utilizing transcranial F.US with microbubbles. Magnetic resonance imaging and immunohistological analyses confirmed enhanced ASO-loaded NP penetration into the brain, reduced SOD1 expression specifically within the F.US-exposed regions, and increased motor neuron survival in the spinal cord, without evidence of structural changes, neuroinflammation, or tissue damage, indicating high tolerability and safety93. In another strategy, brain-penetrating NP with a dense PEG corona, delivered via CED, prolonged survival and eliminated tumors in glioma xenografted rats more effectively than conventional methods94. These findings underscore F.US-assisted NP delivery of ASO as a promising therapeutic approach with broad implications for ALS and other CNS diseases. Nevertheless, deliberate BBB disruption carries inherent risks of compromising neuroprotective functions, necessitating careful optimization to balance efficacy and safety.

Despite these advances, achieving effective bioavailability and CNS specificity remains challenging95,96. The performance of NP is influenced by their physicochemical properties, including size, surface characteristics, molecular interactions, and their ability to navigate physiological barriers. Even after successfully crossing the BBB, therapeutic NP must selectively target diseased neurons while minimizing off-target effects on healthy tissues95,96. These constraints highlight the need for refined delivery systems that maximize CNS targeting while minimizing toxicity. Future research should focus on optimizing nanotechnology-based approaches to enhance motor neuron specificity and therapeutic retention. Innovations such as self-amplifying or replication-competent NP could substantially improve drug bioavailability, enabling sustained and efficient delivery of therapeutic cargo to the CNS.

Advances in viruses and virus-like particles for targeted CNS therapy

Viruses and VLP are at the forefront of innovative strategies for targeted gene therapy in the CNS, emerging as a cutting-edge delivery vehicle that combines the efficiency of viral entry with enhanced safety and specificity. These engineered viral shells, derived from viruses such as lentivirus or plant viruses, can be loaded with therapeutic payloads, including mRNA, proteins, or gene editors, but contain no viral genome, rendering them incapable of replication. Notably, VLP are capable of overcoming key challenges associated with crossing the BBB and BSCB97,98,99. Unlike synthetic NP, VLP emulate the structural and functional properties of natural viruses, leveraging evolutionarily refined pathways to penetrate CNS. These biomimetic approaches facilitate more efficient and precise delivery compared to conventional nanocarriers, addressing critical limitations in CNS therapeutics.

VLP, as outlined in Table 2, can be engineered to replicate the entry mechanisms of lipid-enveloped viruses. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), for example, crosses the BBB via membrane-mediated transport100, while the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) exploits angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor binding and lipid fusion to access the CNS101. The “Trojan horse” strategy, inspired by neurotropic viruses like flaviviruses and rhabdoviruses, further informs VLP design. In this approach, immune cells serve as carriers to shuttle viral particles into the CNS, a principle exemplified by constructs like rabies virus-inspired silica-coated gold nanorods (AuNRs@SiO2), which effectively cross the BBB to target neuronal pathways102. Recent innovations have advanced this paradigm, with VLP now modified to display ligands such as those targeting transferrin or low-density lipoprotein receptors that enhance receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) across the BBB103. Furthermore, by swapping surface glycoproteins, VLP can be engineered for specific cell-type targeting; for instance, incorporating vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein enables broad delivery104,105,106, while measles virus glycoprotein directs particles to neurons and glia, facilitating precise CNS penetration via receptor-mediated uptake107,108,109. These developments significantly improve CNS targeting specificity, though challenges persist in achieving precise cell-type selectivity and ensuring long-term safety and efficacy110,111. Beyond their ability to cross the BBB and target-specific cell types, VLP offer unique advantages for delivering therapeutic payloads to the CNS. One such advantage is the delivery of gene-editing tools like Cas9 as pre-formed RNP. This approach provides a transient burst of editing activity, reducing off-target effects and immune reactions compared to sustained Cas9 expression from DNA vectors. Additionally, researchers have engineered self-amplifying RNA VLP that amplify therapeutic gene expression within target cells. For example, self-replicating RNA (replicon) encoding a reporter gene was packaged into plant VLP; upon delivery, the RNA auto-replicated, leading to robust protein production in vivo at doses significantly lower than those required for non-replicating mRNA112. In a mouse model, these self-amplifying VLP achieved high levels of transgene expression in lymph nodes from a single injection, demonstrating the potential for a single-dose, high-yield gene therapy platform112. For CNS disorders like ALS, this technology could be adapted to deliver replicating RNA encoding neuroprotective factors or gene silencers, sustaining therapeutic levels in motor neurons without the need for repeated dosing. The therapeutic potential of VLP is tempered by biological and physical barriers that influence delivery efficiency. Moreover, while RMT offers the advantage of selective receptor-specific interactions, it presents vulnerability to protein corona formation—a dynamic layer of host proteins that coats NP and viral vectors upon entering biological fluids. The protein corona’s impact is dual-edged: certain compositions may obstruct receptor binding, thus reducing uptake113, while others may enhance interactions with CNS cells103. Inspired by viruses such as human cytomegalovirus and vaccinia virus, which evade immune clearance by integrating host proteins (e.g., CD59) into their envelopes114, researchers have explored protein corona engineering to optimize VLP performance. Such modifications have improved therapeutic outcomes in oncolytic virus models115, and similar strategies are now being adapted to enhance VLP delivery to the CNS, adding a nuanced layer to their design.

Viral vectors, particularly adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), remain pivotal in CNS gene therapy, excelling in preclinical and clinical settings for delivering therapeutic genetic payloads, including in vivo gene editing62,116,117. Preclinical studies using dual-AAV system to deliver cytidine base editors have successfully introduced targeted mutations into the mutant SOD1 gene in ALS mouse models, significantly extending survival, slowing disease progression, and improving neuromuscular function60. Likewise, the specialized AAV variant AAV-PHP.B has shown promise in delivering CRISPR-Cas9 guide RNAs to target the human SOD1 (huSOD1) transgene in SOD1-G93A mice118. When administered intracerebroventricularly in neonatal mice, this approach reduced mutant huSOD1 protein levels, restored motor function, and extended lifespan by over 110 days; a single intrathecal or intravenous injection in presymptomatic adults prolonged survival by at least 170 days118. Recent progress in AAV engineering, including directed evolution of capsids in primates to evade neutralizing antibodies and rational design of capsid mosaics that combine traits such as low immunogenicity and high neural uptake, has yielded variants with superior CNS tropism and reduced off-target effects119,120,121. These next-generation AAVs enhance transduction efficiency in CNS cells while aiming to minimize immune responses and off-target transduction of peripheral organs, thereby amplifying their promise for treating neurodegenerative disorders.

Despite their potential, AAVs and other viral vectors present notable safety concerns. These include off-target effects, genome integration risks, and immune responses that may precipitate severe adverse events such as cytokine storms, inflammation, and other toxicities122. These issues are especially critical in the delicate CNS milieu. Moreover, while AAV-mediated therapy has shown great promise, as exemplified by Zolgensma® for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and ongoing ALS trials, immune-related side effects remain a significant concern. High doses of AAVs can trigger T-cell responses to the capsid or transgene, and many patients carry neutralizing anti-AAV antibodies from natural exposure, which can limit therapeutic efficacy. The immunogenicity of viral vectors further complicates their applicability in repeated or chronic administrations, highlighting the need for safer alternatives. To address these challenges, researchers are developing improved AAV variants with less immunogenic capsids and exploring strategies such as transient immune suppression during therapy to mitigate immune activation. Mitigation strategies are emerging to further enhance safety. These include capsid modifications to evade immune detection, co-administration of immunosuppressive regimens to reduce immune activation, and the incorporation of precise gene regulation mechanisms into AAV payloads, such as tissue-specific promoters or CRISPR-based on/off switches, to avoid off-target gene expression117. Additionally, non-integrating vectors and transient expression systems are being developed to minimize genomic risks while preserving therapeutic benefits123,124.

VLP, in contrast, provide a non-replicating platform that potentially circumvents these immune-related drawbacks, rendering them appealing for CNS applications. Yet, their non-replicative nature necessitates repeated administrations to sustain therapeutic effects, posing practical challenges for chronic conditions like ALS that require sustained intervention. To overcome this, research is pivoting toward self-amplifying VLP or hybrid systems that integrate viral replication elements. Experimental models featuring VLP with replicon RNA enable transient gene expression without repeated administration125. These nascent technologies, while early-stage, signal a transformative direction for VLP-based CNS therapies. Future efforts could prioritize enhancing VLP stability, CNS specificity, and immunological compatibility to bridge the gap to clinical viability. By tackling these hurdles, VLP and advanced viral vectors hold the potential to revolutionize treatment paradigms for ALS and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Rationale and theoretical basis for JEV-based ASO delivery

The JEV, a 50 nm-sized, enveloped, positive-sense RNA flavivirus endemic to Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific, possesses distinctive biological properties that render it a compelling candidate for CNS-targeted gene therapy. As a well-documented neurotropic pathogen responsible for viral encephalitis126,127, JEV’s ability to efficiently target neurons offers a compelling opportunity for therapeutic repurposing. By interacting with specific cellular receptors and chaperones, including glycosaminoglycans and heat shock protein 70, JEV penetrates neuronal membranes through Src kinase and caveolin-1 pathways, enabling targeted CNS delivery127,128,129. In its wild-type (WT) form, JEV predominantly affects hippocampal and cortical neurons, eliciting neuroinflammation and apoptosis. However, this neuroaffinity can be harnessed through genetic engineering to transform JEV into a safe and effective delivery vehicle for ASO capable aim at silencing mutant SOD1 mRNA, a key driver of ALS pathology. Recent studies on flavivirus neurotropism further support this potential, demonstrating that engineered flavivirus can retain CNS targeting while attenuating virulence130.

Proposed mechanism for CNS delivery

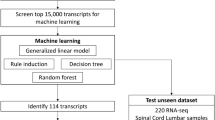

The therapeutic strategy leverages JEV’s inherent “Trojan horse” mechanism to traverse the restrictive BBB and BSCB. Upon infection, the engineered JEV virions are internalized by peripheral immune cells, specifically monocytes or macrophages, which are known to naturally infiltrate the CNS during inflammatory states—a hallmark of ALS pathology131,132. Following intravenous administration, these virions stimulate a controlled immune response, recruiting additional antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages that subsequently take up the viral nanocarriers (Fig. 1). These infected immune cells then act as cellular shuttles, enabling the JEV virions to cross CNS barriers and access ALS-affected regions. Once within the CNS, the immune cells release the engineered virions, which proceed to infect bystander neuronal cells and initiate ASO-mediated silencing of mutant SOD1 (Fig. 1). To further refine and optimize this delivery system, an ex vivo loading strategy could be employed. Autologous monocytes, particularly specific subsets known to infiltrate the CNS during ALS progression, such as lymphocytes antigen 6 complex (Ly6C)-high monocytes, could be isolated from the patient. These monocytes would then be infected with engineered JEV particles in vitro, and subsequently reinfused133. This approach leverages the natural migratory properties of these immune cells while allowing for precise control over the number and type of cells carrying the therapeutic payload, potentially enhancing delivery efficiency and reducing off-target effects. The feasibility of ex vivo loading has been successfully demonstrated in other CNS-targeted therapies, such as macrophage-mediated delivery of nanozymes for neurodegenerative diseases134. This dual-step delivery leverages the precision of ASO therapy with the innate trafficking capabilities of immune cells, offering a minimally invasive alternative to direct CNS injection. Emerging research on immune-mediated CNS delivery, including macrophage-based NP transport, reinforces the feasibility of this approach135,136.

Intravenous administration of miRNA-modified viral particles carrying ASO presents a promising therapeutic strategy for ALS. Upon introduction, the viral particles activate the host’s innate immune system, recruiting immune cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages. These immune cells engulf the viral particles, aiding their migration across the blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barriers. Once within the CNS, the infected immune cells release miRNA-attenuated viral particles, which specifically target motor neurons and other bystander cells. Upon infection, the viral particles release ASOs that inhibit the translation of pathogenic mRNA, particularly mutated SOD1, thus reducing neuronal damage. This targeted delivery system effectively addresses ALS progression by leveraging the neuron-specific infectivity of JEV.

Theoretical basis for a self-replicating JEV-based therapeutic system

Genome engineering for sustained ASO delivery

JEV’s genomic architecture as a positive-strand RNA virus provides an ideal platform for developing a self-replicating therapeutic system. The WT JEV genome, approximately 11 kb in length, encodes three structural proteins (capsid [C], precursor membrane [prM/M], and envelope [E]) and seven non-structural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) (Fig. 2a)137. Upon entering the host cell, the positive-strand RNA genome functions directly as mRNA, bypassing the need for transcription and enabling immediate translation of viral proteins via internal ribosome entry site (IRES) elements that efficiently hijack host ribosomes. We further exploit this inherent efficiency by strategically inserting the ASO sequence at the 3’ end of the genome, adjacent to a protease-recognition sequence (Fig. 2a, lower right). This design enables co-packaging of both the viral genome and the ASO within the same viral particle, maximizing ASO delivery to neuronal cells.

a, b Structural organization of the JEV with surface and inner views highlighting the viral components, including capsid (C), membrane (M), envelope (E), and viral RNA. The WT JEV genome encodes specific structural and non-structural proteins, as illustrated in its genomic organization. This genome can be genetically engineered to incorporate a miRNA insertion between the 5′-UTRs and the structural proteins. Additionally, an ASO can be designed and inserted between the structural proteins and the 3′-UTR, flanked on its right by a proteolytic sequence recognized by one of JEV’s own proteases, such as NS3. c In this modified genome, upon cellular entry, viral replication initiates as the positive-strand JEV genome functions directly as mRNA, producing the typical JEV polyprotein via IRES (i). JEV proteases, including NS3, cleave the polyprotein at specific sites to generate individual viral proteins. Importantly, the JEV protease also recognizes and cleaves the proteolytic site linker engineered to flank the ASO, releasing it into the cytoplasm. This released ASO targets mutated SOD1 mRNA, promoting its degradation and preventing translation of the dysfunctional SOD1 protein via RNAi (ii). Concurrently, the viral RdRp (NS5) transcribes the positive-strand genome into a negative-strand template, facilitating synthesis of a new positive-strand genome. This newly replicated genome, along with the transcribed ASO, is subsequently assembled and packaged into a new virion capable of infecting bystander cells (iii).

Targeted ASO release and RNAi activation

Once inside neuronal cells, the engineered JEV particle releases its genomic RNA, initiating a controlled sequence of molecular processes. The ASO, positioned at the genome’s 3’ end and tethered via a protease-recognition sequence, is cleaved by the JEV-encoded NS3 proteases during polyprotein translation (Fig. 2b). This cleavage releases the ASO into the cytoplasm (Fig. 2c), where it binds and degrade the mutant SOD1 mRNA, reducing the production of misfolded SOD1 proteins associated with ALS pathology [Fig. 2c, (ii)]. This design leverages the virus’s natural proteolytic machinery to ensure precise and timely release of the ASO, aligning its therapeutic action with the viral replication cycle.

However, the protease-dependent release remains constrained by several critical dependencies. Efficient ASO release requires successful translation of the viral polyprotein, functional expression of the NS3 protease, and precise cleavage at engineered recognition sites, tying the process to the host’s translational machinery. In diseased, senescent, or post-mitotic cells like neurons, where translation capacity is often diminished, this dependency could delay or reduce ASO liberation. Furthermore, temporal delays introduced by polyprotein synthesis, potential misfolding, or incomplete cleavage can further diminish the yield of functional ASO, weakening therapeutic efficacy during the crucial early stages of infection.

A refined strategy exploits the catalytic capabilities of self-cleaving ribozymes to liberate an ASO directly from an RNA transcript, bypassing the requirements for translation or proteolytic cleavage through the intrinsic properties of structured RNA motifs138,139,140. In this configuration, the ASO is embedded within the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of the JEV genome, flanked by two catalytic ribozymes: a 5’ hammerhead ribozyme (R1) and a 3’ hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme (R2). A subgenomic promoter (SGP) upstream governs the transcription of this cassette during viral replication (Fig. 3a).

a Schematic of the engineered JEV genome encoding an ASO cassette flanked by self-cleaving ribozymes. The gRNA includes inhibitory sequences ([A], [B]), an SGP, hammerhead ribozyme ([R1]), the ASO payload, and HDV ribozyme ([R2]), and buffer sequences ([B1], [B2]). b Predicted U-shaped self-folding structure of the full-length gRNA. Inhibitory sequence [A] pairs with [B], forming a dsRNA stem (dsRNA-1) with six base pairs (A-U, A-U, G-C, G-C, C-G, C-G), while AA pairs with UU to form a shorter secondary stem (dsRNA-2) comprising two base pairs (A-U, A-U). These interactions stabilize the U-shaped hairpin conformation, spatially constraining ribozymes [R1] and [R2] in a linear, inactive state, thereby preventing premature ASO cleavage. c Upon viral entry, the incoming positive-strand JEV genome is immediately translated via IRES, producing the full complement of JEV polyproteins, including the RdRp NS5. Concurrently, (i) the same positive-stranded genome serves as a template for NS5 to synthesize a full-length complementary negative-strand RNA. This negative strand then acts as a replication intermediate to generate new positive-strand gRNA, each containing the intact ASO cassette, which are subsequently packaged into progeny virions. (ii) In parallel, the negative-strand template supports transcription via the internal SGP, generating linear ASO-containing RNA transcripts. (iii) In this unfolded conformation, ribozymes [R1] and [R2] adopt catalytically active structures and cleave the flanking sequences, releasing a free RNA-ASO. The liberated ASO hybridizes to mutant SOD1 mRNA, triggering RNAi-mediated degradation and suppressing toxic protein translation. Inset: Schematic of the hammerhead ribozyme cleavage mechanism, highlighting stem-loop formation and the catalytic core necessary for RNA cleavage.

To preserve genomic RNA’s (gRNA) integrity during replication and packaging, the ribozymes are rendered inactive by flanking inhibitory sequences, denoted as A (AAGGCC) and B (GGCCUU). These sequences engage in base-pairing with complementary ribozymes regions, forming stable double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) structures, dsRNA-1 and dsRNA-2, which disrupt the essential stem-loop configurations required for catalytic function (Fig. 3b). For instance, AAGGCC pairs with UUCCGG, stabilizing an inactive conformation that precludes premature cleavage (Fig. 3b). Upon cellular entry, the gRNA undergoes translation via an IRES, yielding viral polyproteins, including the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), NS5 (Fig. 3c). The RdRp synthesizes a negative-sense RNA intermediate, which subsequently acts as a template for SGP-driven transcription [Fig. 3c, (i)]. This process generates a linear subgenomic RNA containing the R1-ASO-R2 cassette, free of inhibitory sequences [Fig. 3c, (ii)]. Unconstrained, the ribozymes refold into their catalytically active conformations, triggering self-cleavage.

The R1 adopts a sophisticated three-stem architecture, exemplified by the sequence GGUCUGAUGAGGCCGUUAGGCCGAAACU. Stem I forms through base-pairing between the ribozyme’s 5’ end (GGU) and the ASO’s 5’ end (e.g., ACU from AGUCA), establishing a stable duplex with G-A, G-U, and U-A pairings. Stem II arises internally, with GCC pairing with GGC to form a robust G-C, C-G, G-C triad. Stem III emerges from GUU pairing with AAC, yielding G-A, U-A, and U-C interactions. At the structure’s core, conserved motifs CUGAUGA and GAAA, linked by single-stranded loops, harbor a catalytic site where magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) facilitate a 2’-O-transphosphorylation reaction, cleaving the RNA backbone following a conserved GUC triplet. This cleavage generates a 2’,3’-cyclic phosphate on the ribozyme fragment and a 5’-hydroxyl on the liberated ASO (Fig. 3c, inset).

Simultaneously, the HDV R2 at the ASO’s 3’ boundary adopts a pseudoknot structure, defined by nested base-paired regions and a compact catalytic core. It executes an analogous Mg²⁺-dependent cleavage near its 5’ end, severing the bond immediately downstream of the ASO’s 3’ terminus. This reaction yields a 5’ fragment—the released ASO—with a 3’-hydroxyl, and a 3’ fragment, including R2 and trailing sequences (e.g., UGGUU), bearing a 5’-hydroxyl and 2’,3’-cyclic phosphate. Together, these cleavages excise the ASO as an intact RNA molecule with defined termini, unencumbered by residual sequences. The unprotected ribozyme fragments will be degraded by host RNases, while the ASO becomes immediately available to engage and silence its target mRNA [Fig. 3c, (iii)]. This ribozyme-mediated mechanism liberates ASO release from translational constraints, ensuring therapeutic efficacy irrespective of host protein synthesis dynamics. The rapid generation of subgenomic RNA and subsequent cleavage mitigates the delays inherent in proteolytic strategies, enabling immediate action against pathogenic transcripts during the initial phases of infection. Meanwhile, the gRNA, shielded by its inhibitory duplexes, maintains stability and replication competence, preserving the SGP-ribozyme-ASO cassette for integration into nascent virions. Each infection cycle thus delivers a potent ASO dose while propagating the therapeutic construct, offering both immediate impact and sustained therapeutic impact across successive rounds of viral replication.

Irrespective of the release mechanism, the liberated RNA-ASO hybridizes with its target SOD1 mRNA in the cytoplasm, forming a dsRNA duplex that activates the host’s RNA interference (RNAi) machinery to degrade the pathogenic transcript (Fig. 4). This RNA-centric approach contrasts with traditional DNA-based ASO, which relies on RNase H-mediated cleavage, and instead leverages RNAi for precise gene silencing. The RNA-based ASO integrates seamlessly with the JEV replication dynamics. During viral replication, the RdRp transcribes the ASO directly from the genomic template, incorporating it into the viral RNA pool without requiring chemical modifications such as phosphorothioate linkages. Such modifications, often necessary for stabilizing DNA-based ASO, could disrupt RdRp activity and impair transcription. By utilizing an unmodified RNA-ASO, this system ensures efficient production and functionality, minimizing off-target effects and enhancing therapeutic specificity. The JEV platform’s versatility is evident in its capacity to implement either protease-dependent or ribozyme-driven release strategies, offering a robust and adaptable framework for delivering RNA-based therapeutics to address ALS.

This figure illustrates two strategies for ASO to degrade mutant SOD1 mRNA. (Left panel) DNA-based ASO: chemically synthesized DNA-ASO is directly delivered into the cells, where it binds complementary mutated SOD1 mRNA in the cytoplasm, forming an RNA:DNA duplex. This duplex recruits RNase H, which degrades the target mRNA upon binding. (Right panel) JEV-based ASO delivery: Our proposed engineered JEV viral vectors are initially expressed within cells to produce infectious virions carrying the ASO. Upon infection, the viral genome is processed to release RNA-ASO, which binds to the complementary mutated SOD1 mRNA, forming an RNA duplex. This complex is loaded into the RISC, leading to target mRNA degradation via RNAi.

Self-amplifying therapeutic cycle

In addition, this engineered JEV vector is expected to establish a self-perpetuating therapeutic cycle within the CNS. Following ASO release, as discussed earlier, the viral RNA genome will continue its replication within the host cell. The JEV RdRp synthesizes a negative-strand RNA intermediate, which serves as a template for producing new positive-strand genomes [Fig. 2c, (iii)]. These newly synthesized genomes, integrated with therapeutic ASO, are encapsulated into progeny virions [Fig. 2c, (iii)]. The resulting virions bud from infected neurons and subsequently infect neighboring cells, thereby ensuring continuous ASO delivery and amplifying the therapeutic effect over time (Fig. 1). To further amplify the therapeutic potential, the viral genome can incorporate a feedback-responsive element, such as an aptamer strategically positioned within the 5’-UTR. This element modulates replication rates in response to intracellular levels of mutant SOD1 mRNA or protein, dynamically adjusting the therapeutic output to the disease burden. Such a mechanism optimizes efficacy and minimizes off-target effects141,142, tailoring the intervention to the pathological state of the cell. By leveraging this self-replicating architecture, the system is expected to diminish the necessity for repeated, invasive ASO administrations, offering a theoretical basis for a sustained and adaptive therapeutic approach in ALS treatment.

Enhancing safety through miRNA-mediated attenuation

Building on the self-amplifying therapeutic cycle, the neurovirulent potential of the JEV necessitates robust safety measures to render it suitable for therapeutic applications. A promising strategy to mitigate neuroinflammation and neurotoxicity involves miRNA-mediated attenuation. This strategy leverages the regulatory capacity of miRNAs, which modulate gene expression by targeting mRNA for degradation or translation inhibition via interactions with the 3’-UTR of target mRNAs143. By strategically embedding miRNA target sequences within specific regions of the JEV genome, viral replication can be confined to neuronal tissues, thereby minimizing off-target virulence in non-neuronal sites while retaining JEV’s neurotropic properties for CNS-specific delivery.

Evidence supporting miRNA attenuation in viral vectors

The effectiveness of miRNA-based viral attenuation has been substantiated across diverse viral platforms, demonstrating its versatility and precision. For instance, an engineered CVB3 containing miRNA-133 and miRNA-206 target sites in its 5’-UTR showed reduced replication in skeletal muscle and myocardial cells, where these miRNAs are abundantly expressed. This modification attenuated virulence without compromising the virus’s capacity to stimulate immune responses144. Complementing studies have successfully achieved multi-organ detargeting by integrating tissue-specific miRNA sequences, such as miR-206, miR-29a-3p, and miR-124-3p, thereby limiting viral replication in the pancreas, heart, and brain while preserving therapeutic functionality145. In the realm of oncolytic viruses, miRNA modifications have similarly enhanced safety profiles. Incorporation of miR-34a/c target sequences, which are preferentially expressed in normal cells, into the CVB3 genome resulted in a virus with reduced toxicity to healthy tissues while retaining oncolytic efficacy against lung cancer in murine models146. Further refinements, including the integration of tumor-suppressive miR-145/miR-143 targets, have reduced cardiotoxicity while maintaining oncolytic activity against lung cancer cells147. These findings underscore the potential of miRNA-mediated attenuation to improve both the safety and tissue specificity in viral vector-based therapies.

miRNA modifications for enhanced JEV-based ALS therapy

Building on these advancements, a multifaceted approach refines the safety and specificity of the JEV as a therapeutic vector for ALS. This approach integrates three distinct miRNA-based modifications to optimize the vector’s performance:

-

1.

Brain- and spinal cord-specific miRNAs: Incorporating target sequences for miRNAs highly expressed in neuronal tissues, such as miR-124 and miR-9, to confine viral replication to the CNS.

-

2.

SOD1-targeting miRNAs: Embedding miRNAs targeting mutant SOD1 mRNA to complement the ASO strategy, establishing dual mechanisms for reducing SOD1 expression.

-

3.

Replication-attenuating miRNAs: Inserting miRNA target sequences that restrict viral replication that bolster systemic safety, particularly during intravenous administration.

These miRNA targets are strategically positioned within the JEV genome, including regions between the 5′-UTR and capsid coding sequence, between NS5 and the 3′-UTR, or within intergenic segments separating structural and non-structural protein coding sequences. This design allows for replication to be fine-tuned by tissue- and target-specific miRNAs, enabling the engineered JEV to function as a selective ASO delivery vector with reduced off-target effects while preserving therapeutic efficacy.

Integrated strategy for JEV-based ALS therapy

The development of a JEV-based ALS therapy requires a coordinated strategy that enhances CNS specificity while maintaining safety and delivery efficiency. This approach integrates brain- and spinal cord-enriched miRNAs, along with miRNAs targeting mutant SOD1 or viral replication elements (Fig. 5). Preclinical studies using AAV vectors encoding miRNAs against mutant SOD1 in motor neurons have demonstrated substantial reductions in both SOD1 expression and associated neurotoxicity, highlighting the potency of miRNA-guided attenuation148,149. To optimize safety and stability, several configurations have been developed for miRNA integration into the JEV genome (Fig. 5b). These include: (1) insertion of tissue-specific miRNAs, such as miR-124, or SOD1-targeting miRNAs between the 5’-UTR and capsid coding region, or between NS5 and 3’-UTR; (2) co-insertion of tissue-specific and replication-restricting miRNAs to limit systemic viral dissemination; (3) substitution of selected 5’-UTR sequences with miRNA-responsive sequences; and (4) incorporation of miRNAs within intergenic regions that separate structural and non-structural proteins. These modular configurations enable precise post-transcriptional regulation, enhancing the susceptibility of the engineered JEV toward neuronal cells while reducing replication in non-neuronal tissues.

a The WT JEV genome organization is shown, highlighting both the structural (C, PrM, E) and non-structural proteins (NS1-NS5), along with the 5’- and 3’-UTRs. b Modified JEV genomes with various miRNA insertion strategies: Option 1: Insertion of multiple copies of brain/spinal cord-specific miRNAs either between the 5′-UTR and Capsid coding region or between the NS5 and 3′-UTR regions. Option 2: Insertion of a combination of brain/spinal cord-specific miRNAs and miRNAs targeting mutated SOD1 between the 5′-UTR and Capsid coding region. Option 3: Substitution of specific sequences at the 5′-UTR with multiple copies of either brain/spinal cord-specific miRNAs or the combination of brain/spinal cord-specific miRNAs and miRNAs targeting mutated SOD1. Option 4: Insertion of brain/spinal cord-specific miRNAs between the precursor membrane (PrM) and envelope (E) coding regions, as well as between the envelope (E) and NS1-coding regions.

Challenges and considerations

Although miRNA-mediated attenuation presents a promising safety enhancement, careful optimization is required to maintain the therapeutic functionality of the JEV vector. Primary challenges lie in:

-

1.

Balancing attenuation and efficacy: Over-attenuation of viral replication can impair ASO delivery to target cells, reducing therapeutic effectiveness. Achieving an appropriate balance necessitates iterative evaluation of miRNA target locations and combinations to maintain both delivery efficiency and safety.

-

2.

Variability in miRNA expression: Endogenous miRNA expression varies across individuals and disease states. This heterogeneity, especially within neurodegenerative conditions such as ALS, may impact attenuation consistency. Incorporating multiple tissue-specific miRNAs may help mitigate this variability.

-

3.

Viral genome stability: Inserting miRNA target sites must preserve the integrity of essential cis-acting elements required for JEV replication, RNA synthesis, and packaging. Placement within non-essential intergenic regions or the 3’-UTR may offer regulatory flexibility while maintaining genome stability.

Optimizing the JEV-based system: a triad of compatibility, packaging, and stability

Building upon these safety considerations, further refinement of the JEV platform requires attention to three interdependent factors: compatibility, packaging, and stability. These components form the foundation for maximizing therapeutic efficacy while preserving viral function. First, compatibility refers to the ability to insert the ASO sequence in a manner that aligns with virus’s replication dynamics. This must be achieved without disrupting essential cis-acting elements, particularly those located near the 3′ end of the viral genome, which are integral for RNA synthesis and genome packaging150. Perturbations to these elements could compromise viral replication, undermining the self-sustaining ASO delivery mechanism. To circumvent this, the ASO sequence should be positioned downstream of core 3’-UTR elements, preserving the structural integrity necessary for efficient replication and packaging. Second, packaging efficiency is another key consideration, as the introduction of the ASO sequence may influence genome encapsidation in positive-strand RNA viruses like JEV, which rely on specific signals for RNA incorporation. Variations in packaging capacity could reduce the yield of therapeutic virions, necessitating rigorous testing to ensure that the ASO is effectively encapsulated without compromising viral yield or therapeutic potency. Third, stability of the RNA-ASO within both the viral particle and host cell environment is critical for sustained therapeutic impact. Susceptibility to degradation by host cellular nucleases risks reducing ASO availability, but this can be mitigated by incorporating flanking sequences, such as single-stranded RNA aptamers or stem-loop structures, to enhance nuclease resistance and prolong functional longevity. In the present suggested design, the ASO remains unmodified to retain full compatibility with the viral RdRp. However, given the inherent instability of unmodified RNA, future iterations may explore selective chemical modifications to enhance resistance to degradation. These efforts must be guided by empirical compatibility with viral replication machinery, as discussed below151,152.

Beyond these considerations, the design of ASO architecture must be aligned with the intracellular silencing pathway they are intended to engage. As described earlier, the canonical DNA-based gapmer ASO (i.e., tofersen) is engineered to engage the RNase H pathway by incorporating a central DNA “gap” flanked by 2ʹ-modified RNA-like nucleotides (e.g., 2ʹ-O-methoxyethyl RNA). This configuration enables the formation of RNA:DNA heteroduplexes that recruit RNase H to selectively cleave the target transcript153. While the central DNA core must remain minimally modified for enzymatic recognition, chemical modifications to the flanking regions improve nuclease resistance and stability. In contrast, RNA-based ASO that function through the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) adopt double-stranded, siRNA-like architectures. These designs are optimized for Argonaute 2 (AGO2) engagement, incorporating a guide strand with 2ʹ-fluoro and 2ʹ-O-methyl modifications, phosphorothioate linkages, and a 3ʹ dinucleotide overhang to facilitate RISC assembly and activity. A 5ʹ-(E)-vinylphosphonate modification may further enhance AGO2 binding affinity153. These divergent strategies highlight the importance of tailoring ASO chemistry to both the intracellular effector pathway and the biological delivery context.

This need for alignment extends beyond intracellular processing to the selection of the target itself, particularly in the context of genetically heterogeneous diseases such as SOD1-linked ALS. Although SOD1 mutations account for only a small fraction of ALS cases, they include more than 200 pathogenic variants (e.g., A4V, D90A, G93A, G85R, I104F, I114T etc.), each characterized by distinct structural changes154. This diversity severely undermines the utility of single-allele ASO designs that require perfect complementarity to individual mutations. To address this, our JEV-based platform targets a transcript region conserved across nearly all SOD1 variants. Specifically, the system delivers a single RNA-ASO directed against the 3’-UTR of SOD1. This approach reliably engages the RISC pathway, promoting degradation of mutant transcripts independent of the upstream coding sequence. By coupling a conserved molecular target with a neurotropic, self-replicating viral vector, our strategy enables broad allelic coverage while maintaining mechanistic precision and silencing specificity.

JEV’s biological features offer several advantages over traditional viral vectors like AAVs for CNS-targeting gene therapy. Its intrinsic neuronal tropism enhances delivery directly to ALS-affected cells while minimizing off-target exposure. Unlike adenoviruses, JEV’s positive-strand RNA genome acts directly as mRNA, enabling immediate protein synthesis via an IRES, bypassing transcription. Additionally, JEV’s self-amplifying replication, wherein negative-strand RNA intermediates template new ASO-bearing positive-strand genomes, further augments the therapeutic potential. The relatively compact genome and streamlined replication cycle minimize complexity and potential immunogenic burden, making JEV especially well-suited for CNS applications.

Beyond neuron-specific targeting, JEV also offers a broader neurotrophic profile compared to RVG and its peptide derivatives, which are commonly used in NP and lentiviral platforms102,155. RVG binds to specific neuronal receptors such as nicotinic acetylcholine and p75 neurotrophin receptors, limiting its utility to neurons156. This exclusivity is suboptimal for ALS, where disease progression involves not only motor neurons but also astrocytes, microglia, and vascular endothelial cells. JEV naturally infects all these cell types via receptor-mediated endocytosis157, positioning it as a versatile vehicle for addressing the multicellular pathophysiology of ALS. Moreover, JEV’s genomic flexibility allows targeted engineering of both coding and noncoding elements, including envelope proteins and regulatory regions. This facilitates rational attenuation strategies to balance safety with delivery efficiency, a capability that RVG, used primarily as a targeting ligand, inherently lacks. In addition, lessons from live-attenuated JEV vaccines provide additional frameworks for managing neurovirulence and immunogenicity158. When evaluated against other emerging CNS-delivery strategies, including viral vectors, non-viral nanocarriers, and small-molecule therapeutics, the JEV-ASO platform stands out for its integration of self-replication, bioavailability, and cell-type versatility. These features collectively position JEV-ASO as a uniquely capable system for addressing complex neurodegenerative conditions such as ALS (Table 3).

Perspective

The JEV-ASO platform marks a conceptual advance in CNS-targeted gene therapy, uniting the neurotropic specificity and self-replicating nature of JEV with the gene-silencing precision of ASO. This dual modality approach simultaneously addresses three long-standing barriers in ALS therapeutics: achieving neuronal targeting, sustained intracellular presence through autonomous replication, and limiting systemic toxicity through cell-type restricted expression. JEV’s evolutionary refinement for CNS tropism, coupled with its amenability to modular genome engineering, positions it as a distinctive candidate for high-precision, scalable RNA-based interventions.

Despite its promise, several fundamental challenges remain before such a strategy can be realized in translational settings. These challenges revolve around three critical pillars: ensuring transcriptional fidelity of therapeutic payloads, maintaining compatibility with chemical modifications, and preserving structural integrity during genome packaging and release.

Transcriptional fidelity of ASO by viral RdRp

A central limitation of self-replicating RNA vectors lies in the error-prone nature of viral’s RdRp. JEV’s RdRp lacks proofreading capability, introducing mutations at a rate of approximately 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁵ per nucleotide per replication cycle159,160. Such mutational drift risks compromising ASO specificity for mutant SOD1 mRNA and may increase unintended off-target interactions within the CNS. This creates a mechanistic paradox: the very self-amplification that supports sustained delivery also jeopardizes nucleotide precision and, by extension, therapeutic accuracy. One promising direction involves rational modification of RdRp to enhance fidelity. Substitutions in the polymerase’s finger domain, for example, have been shown to reduce misincorporation while preserving enzymatic activity161,162. However, increasing fidelity may impair processivity or polymerase-RNA interactions, potentially diminishing amplification efficiency. Moreover, RdRp infidelity contributes to viral immune evasion159, suggesting that fidelity optimization could alter viral tropism or immunogenicity. These competing pressures necessitate a delicate balance between biochemical stringency and virological fitness.

An alternative avenue centers on increasing the error tolerance of ASO itself. Incorporating degenerate base pairs or multiple SOD1-targeting segments may buffer against minor sequence errors163. Concepts drawn from information theory, such as redundancy and Hamming distance, could guide the engineering of robust RNA sequences capable of retaining function despite replication-associated noise. While these approaches increase robustness, they may also exceed the packaging limits of JEV’s compact genome150, or inadvertently increase off-target potential, underscoring the need for precise computational modeling and empirical validation. The fidelity challenge reflects a broader evolutionary dilemma: to what extent can JEV’s replicative machinery be re-engineered without compromising its neurotropic fitness? Comparative studies across neurotropic viruses, such as measles or rabies, may identify polymerase architectures with superior fidelity125. Advancing this platform will likely depend on a synergistic integration of synthetic ASO design, high-fidelity polymerase design, and systems-level modeling of virus-host interactions.

Exploring chemical modification for future stability gains

While the current JEV-ASO design employs unmodified ribonucleotides to ensure compatibility with viral replication, improving intracellular stability through chemical modification remains a future direction of interest. Achieving this will require reconciling ASO stability with the biochemical constraints of JEV’s RdRp. Common stabilizing modifications, including phosphorothioate linkages and 2’-O-methyl substitutions, are widely employed to improve ASO resistance against cytoplasmic nucleases and prolong intracellular half-life51,163. However, such modifications may impede the transcriptional performance of the viral polymerase, which is evolutionary optimized to recognize unmodified ribonucleotides159. Structural investigations of polymerase-RNA complexes provide valuable insights into this incompatibility. Cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) has revealed how steric and electrostatic barriers introduced by modified nucleotides can disrupt RdRp binding or reduce elongation efficiency164. Studies of related viruses, such as hepatitis C, demonstrate that certain 2’-modifications may still be accommodated, albeit with compromised incorporation rates165. These suggest that selective design of compatible chemical motifs: those minimally disruptive to polymerase engagement, may reconcile stability with transcriptional feasibility.

A more scalable strategy involves high-throughput screening of modification libraries using in vitro transcription assays, coupled with next-generation sequencing to track fidelity and efficiency across diverse ASO templates166. These empirical datasets can feed into predictive models, including machine learning frameworks, to identify optimal modification patterns that balance intracellular durability with polymerase compatibility167,168. Natural analogs such as pseudouridine may further enhance transcript stability while preserving recognition by the viral polymerase, offering a biochemically conservative alternative to synthetic derivatization. Importantly, these challenges extend beyond JEV and reflect a broader constraint across RNA virus-based vectors. Comparative profiling of RdRp tolerance across neurotrophic viruses, such as alphaviruses, rhabdoviruses, and other positive-strand RNA viruses, could yield a classification system for polymerase permissive modifications125. Establishing such design rules would accelerate the rational construction of chemically stabilized, replication-competent ASO delivery systems.

Stability of ASO tethering during polyprotein processing

Ensuring the structural integrity and timely release of the ASO during JEV’s polyprotein translation and processing represents another technical frontier. Improper cleavage or premature degradation could compromise ASO liberation and impair its gene-silencing activity. This necessitates careful mapping of insertion sites within the viral genome that are simultaneously insulated from aberrant proteolysis and accessible to the NS3 protease at the appropriate stage of infection.

Advances in structural virology now permit detailed modeling of JEV’s polyprotein folding landscape. Cryo-EM and molecular dynamics simulations can pinpoint flexible, solvent-accessible domains that are permissive to sequence insertion without disrupting global conformation169. Rationally engineered linkers incorporating NS3 recognition motifs, particularly dibasic sequences shown to be cleaved with high specificity, can further ensure precise ASO release at defined temporal stages. Conformational shielding, achieved through intrinsically disordered linkers or RNA-protein chaperone interactions, may enhance ASO retention during virion assembly. Nonetheless, excessive structural elaboration introduces new risks. Complex linker architectures may delay ASO deployment or interfere with polyprotein maturation, potentially attenuating replication efficiency or eliciting host immune activation. These trade-offs reflect the delicate modularity constraints that govern flaviviral proteome processing. Insertions must not disrupt the spatial and kinetic choreography of viral protein cleavage, which is tightly linked to replication and packaging efficiency.

Alternatively, catalytic self-cleavage ribozymes, as discussed earlier, offer a distinct strategy for ASO release. This mechanism enables direct liberation of the ASO from the RNA transcript independent of host translation machinery. In neuronal environments with limited protein synthesis capacity, this mechanism may offer more consistent and rapid therapeutic activation. By functioning entirely at the RNA level, ribozyme-based designs not only mitigate delays inherent to polyprotein maturation but also expand the engineering flexibility of the JEV genome. Aside from that, cross-species analyses of flavivirus genomes may help identify conserved, non-essential regions suitable for ASO integration125. Moreover, machine learning models trained on protease cleavage datasets can predict linker designs with favorable processing kinetics and minimal structural disruption170,171. These tools may prove critical in navigating the balance between functional ASO release and viral fitness, ensuring that the delivery vehicle remains both biologically viable and therapeutically potent.

Future directions and research horizons

As the molecular features of the JEV-ASO platform become increasingly well characterized, the focus must now shift toward its translational applicability. The capacity for self-replication offers a distinct advantage for sustained delivery in the CNS but also introduces challenges related to replication control, immune modulation, and disease-specific adaptability. Addressing these issues will require an integrated approach that combines molecular engineering with systems-level design tailored to the complexity of neurodegenerative disorders.

Controlling self-replication: toward precision and containment

The autonomous propagation of the JEV-ASO system introduces a paradigm shift in gene therapy by enabling sustained therapeutic output without repeated dosing. At the same time, it introduces regulatory complexity. Although miRNA-mediated attenuation confers tissue selectivity, it offers only partial containment in a setting marked by cellular heterogeneity, fluctuating inflammation, and potential for barrier breach. The challenge, therefore, is not simply to restrict replication, but to encode within the vector a form of molecular self-awareness—an ability to sense, adapt, and constrain its own activity in response to the host environment. Layered regulatory systems, long established in gene circuit design, offer one conceptual scaffold. Suicide cassettes such as the herpes simplex virus (HSV) thymidine kinase system, activated by ganciclovir, function as pharmacological “kill switches”, enabling clinicians to arrest viral replication during adverse events172. These systems are elegant in their simplicity but contingent on pharmacokinetics that may be suboptimal or variable in diseased CNS tissue. Likewise, tetracycline-responsive transcriptional elements173 allow for graded external control but face limitations in chronic neurological conditions, where sustained dosing may alter immune homeostasis or provoke off-target responses. These considerations shift attention toward self-contained regulatory strategies that do not rely on exogenous control.

Negative feedback systems, another gene circuit design, may enable replication scale in response to intracellular thresholds174. Riboswitches sensitive to endogenous metabolites or neural stress markers could fine-tune replication in real time, synchronizing therapeutic activity with disease state175. The use of biomarker-informed regulators, such as neurofilament light chain-responsive switches, exemplifies how precision may be aligned with disease progression. Nonetheless, these strategies must contend with JEV’s compact genome and the intrinsic mutability of its RdRp159, which together constrain circuit complexity and fidelity. The incorporation of orthogonal regulatory parts—genetically insulated from native viral sequences—may reduce interference and drift. Spatial precision also remains essential. The deployment of motor neuron-specific promoters to drive essential viral genes could limit replication to target populations, while receptor engineering of viral envelope proteins may enhance tropism for cell types expressing restricted surface markers (e.g., neuronal nerve growth factor receptor)176. However, the reactive and heterogeneous nature of the ALS-affected CNS complicates such targeting. Shifts in receptor expression and barrier permeability during disease progression introduce unpredictability. Insights from other neurotropic viruses, including rabies and AAV variants176,177, may help refine targeting strategies. Still, spatial control in a degenerating CNS may not suffice; the interplay between virus, host immunity, and neuroinflammatory feedback necessitates integrated strategies that combine containment with immune evasion or modulation.

This complexity points to the growing importance of computational foresight. Stochastic simulations incorporating RdRp mutation rates, immune dynamics, and CNS architecture can forecast replication kinetics and failure modes178. Yet, modeling alone cannot capture the emergent behavior of inflamed neural circuits. Here, machine learning trained on single-cell and spatial transcriptomic datasets may offer an adaptive layer of prediction, identifying context-dependent regulatory vulnerabilities and optimizing circuit design for patient-specific microenvironments. Such models could enable dynamic tuning of replication parameters in silico, prior to clinical translation.

Long-term immunogenicity: navigating the neuroimmune interface

A replicating viral vector introduced into the CNS operates within a tightly regulated immune landscape. In ALS, this landscape is further complicated by chronic inflammation, BBB dysfunction, and cellular turnover. Microglial activation, reactive astrogliosis, and elevated cytokine levels define a microenvironment that not only reacts to therapeutic vectors but may actively shape their fate.

In this context, the cGAS-STING and Type I/II interferon pathways14,16 warrant deeper scrutiny. These pathways—already implicated in ALS pathogenesis—could intersect with vector-induced immune responses in unpredictable ways. The activation of cytosolic sensors such as retinoic acid-inducible gene-I and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 in response to replicating viral RNA might potentiate neuroinflammation. Yet, paradoxically, under certain conditions, these same innate pathways might be reprogrammed toward a neuroprotective phenotype. Thus, the central question evolves from whether immune activation will occur to how it can be strategically directed. While miRNA-mediated attenuation curtails replication in professional antigen-presenting cells, residual viral protein expression may nonetheless provoke adaptive immune responses. The development of neutralizing antibodies may curtail vector efficacy and preclude redosing, and cytotoxic T-cell activation against transduced neurons poses a direct threat to therapeutic durability. Rational design strategies such as CpG motif depletion or incorporation of stealth sequences may mitigate these risks but must be adapted to the neuroinflammatory context of disease.

The backdrop of pre-existing flavivirus immunity further complicates the therapeutic equation. Cross-reactive antibodies could accelerate vector clearance or redirect infection through antibody-dependent enhancement, altering both safety and biodistribution. Concurrently, ALS-associated BBB dysfunction could allow peripheral immune cells to infiltrate the CNS post-administration, reshaping the local immune landscape and potentially tipping the balance between efficacy and toxicity. To navigate this landscape, a shift toward predictive immunological analytics is essential. Single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and longitudinal profiling of immune repertoires can provide a multidimensional view of host-vector interactions. These data, when integrated into computational models, could support anticipatory design of vectors that are optimized not only for genetic compatibility but also for immunological alignment within diseased neural circuits.

Translatability across neurodegenerative landscapes

The core attributes of the JEV-ASO platform, including selective neurotropism, autonomous replication, and modular transcriptional control, provide a flexible foundation that can be tailored to diverse neurological diseases. In Alzheimer’s disease, where pathological processes involve neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, cell-specific targeting combined with ASO targeting amyloid precursor protein or tau transcripts could support multifocal intervention. Anti-inflammatory sequences delivered to glial cells may help suppress neurotoxic cascades, while envelope modifications could enhance vector dissemination across complex brain regions.