Abstract

Individuals with schizophrenia experience significant cognitive impairments and alterations in brain function. However, the shared and unique brain functional patterns underlying cognition deficits and symptom severity in schizophrenia remain poorly understood. We design an interpretable graph-based multi-task deep learning framework to enhance the simultaneous prediction of schizophrenia illness severity and cognitive functioning measurements by using functional connectivity, and identify both shared and unique brain patterns associated with these phenotypes on 378 subjects from three datasets. Our framework outperforms both single-task and state-of-the-art multi-task learning methods in predicting four Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) subscales and four cognitive domain scores. The performance is replicable across three datasets, and the shared and unique functional changes are confirmed by meta-analysis at both regional and modular levels. Our study provides insights into the neural correlates of illness severity and cognitive implications, offering potential targets for further evaluations of treatment effects and longitudinal follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a chronic neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a detachment from reality. It manifests as positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions) and negative symptoms (e.g., restricted affect, reduced emotional variability), affecting ~24 million people globally1. Cognitive impairments, a core feature of SZ2, often emerge before the full onset of the disorder3, and they can range from mild to severe4,5. These cognitive deficits involved domains such as working memory, executive functioning, language, processing speed, motor skills, and attention4.

Resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) captures neural activity fluctuations using blood-oxygen-level-dependent signals and has been widely used to study both cognitive functioning6,7,8 and SZ. Functional connectivity (FC) derived from rs-fMRI provides valuable insights into various cognitive states8,9. Recent studies have linked brain functional regional variability in frontal and parietal cortices to different statuses of multiple cognitive domains, including attention9, working memory9, processing speed9, motor skills10, and verbal learning11, particularly in healthy individuals. Moreover, FC has proven to be useful for distinguishing individuals with SZ from healthy controls12,13. Previous studies have found that functional changes in regions such as the cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas are associated with different stages of SZ14,15,16,17, particularly symptoms such as auditory hallucinations and reduced emotional expressivity.

Despite the broad literature on cognition and SZ, the functional alterations associated with normal cognitive functioning and SZ symptom severity remain difficult to disentangle from those related to cognitive impairments. Comprehensive whole-brain analyses that disentangle brain regions associated with normative cognitive functioning, SZ-related cognitive impairments, and illness severity are essential for elucidating the neural correlates of schizophrenia-related symptomatology and cognitive dysfunction. Clearly delineating these associations would facilitate the identification of brain regions most strongly linked to specific clinical outcomes, enable the development of targeted interventions, and enhance our understanding of how SZ disrupts particular cognitive processes. However, such studies remain scarce. For instance, functional disruptions in several regions18,19,20 have been associated with cognitive deficits in SZ. Some evidence indicates that functional changes associated with cognitive deficits in SZ, such as in the supplementary motor area, overlap with those underlying individual variability in normative cognitive functioning in healthy individuals21,22. However, it remains unclear whether these regions are more closely associated with SZ-specific cognitive impairments or with typical cognitive variability. On the other hand, neurobiological studies have suggested that alterations in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway and increased activity in the prefrontal and orbitofrontal regions relating to ventral striatum and cingulate cortex are more closely associated with psychotic symptoms (e.g., hallucinations and delusions) than with cognitive deficits23,24,25,26. However, whether additional regions are more closely associated with SZ symptom severity than with cognitive impairments in SZ remains to be further investigated.

To fill these gaps, building on previous studies, we propose two hypotheses in this study (1) shared neural mechanisms underlie both SZ symptom severity and cognitive deficits, which can be detected through regional functional changes; and (2) distinct mechanisms, reflected in functional regional alterations, are independently associated with either symptom severity or variability in cognitive functioning. To test these hypotheses, a method capable of extracting shared and unique functional markers for SZ symptom severity and the extent of cognitive functioning from FC is necessary.

In recent years, predictive modeling approaches—especially deep learning—have shown promise in revealing complex associations in rs-fMRI data for both disease and cognitive trait prediction27,28. Since FC can be naturally represented as a graph structure, where regions of interest (ROIs) are modeled as nodes and connectivity strengths as edges, graph neural networks29 have been widely adopted. To date, studies systematically disentangling the shared and distinct functional alterations underlying SZ symptom severity and cognitive impairments within a unified predictive framework are scarce. Most existing approaches focus on either clinical or cognitive outcomes in isolation30,31,32,33,34, limiting their ability to identify overlapping and task-specific neural substrates. Multi-task deep learning provides a promising strategy to leverage shared representations across multiple tasks, thereby improving generalization and performance35,36,37,38,39. Here, “multi-task” refers to the model’s multiple simultaneous outputs, which is distinct from the multi-task fMRI paradigm. However, there remains a critical need for an interpretable multi-task method that effectively utilizes a graph-based backbone to extract both shared and unique important regions associated with SZ illness severity and cognitive function.

To address these challenges, we propose a graph-based multi-task learning framework that simultaneously predicts four SZ severity measurements and four cognitive scores. The framework is applied to three SZ datasets with SZ illness severity measurements (from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)40) and cognitive assessments, and outperforms single-task learning and state-of-the-art multi-task learning methods. We further extract both shared and distinct regional contributions to illness severity and cognitive deficits, and conduct meta-analyses based on the BrainMap database41 to compute the probabilities of these biomarkers contributing to SZ and cognition at both regional and modular levels. Our findings reveal that shared neural mechanisms are primarily located in regions such as the supplementary motor area, dorsal cingulate cortex, middle temporal gyrus, anterior prefrontal cortex, middle frontal gyrus, and visual cortex related to the default mode, visual, and salience networks (SNs). Additionally, regions such as the posterior cingulate cortex, Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas, inferior frontal gyrus, and retrosplenial cortex are more strongly associated with SZ symptom severity. In contrast, the superior and inferior temporal gyri, anterior cingulate cortex, and superior parietal lobule—particularly within the attention and SNs—are more closely linked to cognitive performance. These insights advance our understanding of the neural basis underlying SZ and cognitive impairment and may inform future clinical interventions targeting distinct and shared biomarkers.

Results

Demographic and clinical assessment

This study included 135 Center for Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE)42 and 37 Institute of Mental Health (IMH)43 subjects, with no significant difference in age (t = 0.98, p = 0.33). The total PANSS score and its three subscale scores were comparable between the two samples (total t = 1.42, p = 0.16; positive t = 1.57, p = 0.12; negative t = 1.04, p = 0.30; general t = 1.44, p = 0.15). The processing speed, working memory, and verbal learning domains were assessed using Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS)44 for the COBRE sample and Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS)45 for the IMH sample. The attention domain was measured using BACS in both samples. No significant difference was observed in attention domain scores between the two samples (t = −0.29, p = 0.77). Group comparisons on other cognitive domain measures were not conducted due to differences in assessment tools in the two samples. Moreover, this study included 206 subjects from the Strategic Research Program for the Promotion of Brain Science (SRPBS)46 sample for replication of the framework. The total PANSS score and its three subscale scores were comparable between the COBRE and SRPBS samples (total t = 0.95, p = 0.34; positive t = 1.69, p = 0.10; negative t = 0.92, p = 0.36; general t = 0.71, p = 0.48). The demographic details, PANSS, and cognitive functioning scores are shown in Table 1.

The prediction of multiple cognition scores and PANSS scales in COBRE

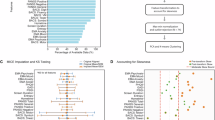

Figure 2a illustrates the prediction accuracy of four PANSS subscales and total scores and four cognitive domain scores, assessed by Pearson’s correlation and mean absolute error (MAE) between actual and predicted values by using single-task and multi-task learning networks (Fig. 1c). Single-task learning was trained with encoder and decoder components, without joint attention, to predict each task separately.

a The progression of functional alterations across different stages of schizophrenia (SZ), beginning with healthy cognitive functioning, followed by emerging cognitive deficits, the onset of mild SZ symptoms, and subsequently more severe symptoms. The Venn diagram presents the objective of our study: to disentangle shared functional changes associated with both illness severity and cognitive deficits, as well as the distinct functional changes unique to illness severity and variability in cognitive functioning. It is important to note that, because SZ is highly heterogeneous, its progression follows multiple pathways—for example, some subgroups maintain relatively intact cognitive function despite severe symptoms81. To simplify our investigation, we adopt a linear-progression model in which individuals move from normative cognitive functioning to cognitive impairment and then to increased symptom severity in SZ. b The preprocessing of rs-fMRI images and the construction of the graph representation, where ROIs are treated as nodes and connectivity values are treated as edges. c Our interpretable graph-based multi-task learning network, designed to predict four PANSS and four cognition domain scores simultaneously based on functional connectivity. This network uses a graph transformer model as a common encoder to capture features common to both SZ and cognition prediction. The common features are subsequently processed by separate encoding modules based on graph attention networks to extract features specific to cognition and SZ prediction, respectively. A shared attention module, implemented using a bottleneck-like multilayer perceptron (MLP), is introduced to identify salient shared regions contributing to both predictions. The decoder module, implemented using top-K pooling layers, is employed to identify important regions specific to each item prediction. Finally, an individual output layer is used to generate the individual outcome for each item. d The structure of the results analysis. We compare our proposed method with single-task learning and state-of-the-art multi-task learning baselines, as well as ablated variants of our approach. We then extract both shared and task-specific important regions associated with illness severity and cognitive deficits. These identified regions are further validated through meta-analyses by estimating their likelihood of association with SZ and cognitive functions at both regional and modular levels.

a The box-plot charts of Pearson’s correlation coefficients and mean absolute error (MAE) between the actual and predicted scores using single-task learning (green) and multi-task learning (orange) over 10 runs of five-fold cross-validation on the COBRE (n = 135) and IMH datasets (n = 37). “*” indicates that multi-task learning significantly improves the accuracy compared to single-task learning, confirmed by Student’s t-test, and applied a false discovery rate (FDR) correction across the full set of tests, using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure with p < 0.05. b Scatter plots of actual and predicted scores from one run for both the COBRE and IMH samples. Blue and yellow colors represent the performance of PANSS and cognitive domain scores predictions.

For the COBRE sample, the multi-task learning network predicted the PANSS positive, negative, general psychopathology subscale, and total scores, processing speed, attention, working memory, and verbal learning scores with Pearson’s correlation of 0.52 ± 0.03, 0.52 ± 0.03, 0.52 ± 0.02, 0.50 ± 0.03, 0.50 ± 0.04, 0.51 ± 0.04, 0.30 ± 0.04, and 0.27 ± 0.04, respectively. Multi-task learning significantly improved correlations over single-task learning for PANSS positive subscale (16.7%, p = 0.001), negative subscale (9.7%, p = 0.046), general psychopathology subscale (13.9%, p = 0.046), and total (5.9%, p = 0.046) scores, processing speed (8.3%, p = 0.046), and attention (7.5%, p = 0.046) scores, respectively, as confirmed by Student’s t-test, and applied a false discovery rate (FDR) correction across the full set of tests, using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Improvements in working memory and verbal learning predictions were not statistically significant, possibly due to weaker correlations between these two domains and PANSS scores (Fig. S2), potentially reducing the effectiveness of multi-task learning. Furthermore, multi-task learning significantly reduced MAE values by 10.6% (p = 0.010) for PANSS positive subscale score, 10.0% (p = 0.031) for general psychopathology subscale score, 7.6% (p = 0.031) for total score, and 4.1% (p = 0.031) for processing speed domain scores compared to single-task learning.

Figure 2b displays scatter plots of actual and predicted scores based on FC. We conducted additional analyses comparing the predicted PANSS scores between healthy controls and patients. The predicted means for controls on the positive, negative, general, and total subscales are 2.7, 2.8, 4.3, and 7.3, respectively, versus 8.8, 10.1, 16.7, and 36.5 for patients. Student’s t-test confirmed that controls’ predicted scores are significantly lower than patients’ across all subscales (positive p = 7.6 × 10−14, negative p = 8.3 × 10−19, general p = 2.6 × 10−14, total p = 8.1 × 10−17), indicating that the model successfully differentiates between groups. Moreover, we then evaluated the predicted cognition scores between healthy controls and patients. The predicted means for controls on processing speed, attention, working memory, and verbal memory were 45.9, 45.9, 42.8, and 43.0, respectively, versus 37.9, 38.4, 39.2, and 40.4 for patients. All differences were significant (processing speed p = 2.4 × 10−8, attention p = 7.3 × 10−9, working memory p = 0.001, verbal memory p = 0.002), indicating that the model successfully differentiates between groups. Moreover, for the control group, the correlations between predicted and actual values of processing speed, attention, working memory, and verbal memory are 0.41, 0.44, 0.34, and 0.35 for the control group, and are 0.45, 0.40, 0.38, and 0.22 for the patient group, respectively.

Comparisons with the baseline methods

To evaluate the effectiveness of our model, we compare it with several baselines, including graph attention network (GAT), general, powerful, and scalable (GPS), and two state-of-the-art multi-task learning methods the Brain Network Transformer Multi-task Learning Network (BNT-MT)38 and Multi-Level Attention Network (ML-Att)39. To ensure fair comparisons with the multi-task learning frameworks, we constructed GAT-MT by incorporating a shared GAT convolution layer along with two task-specific GAT convolution layers for encoders; a similar construction was applied to GPS-MT. BNT-MT employs a brain network transformer as a shared encoder for multiple cognitive predictions, while ML-Att introduces a unified joint attention mechanism for multi-task learning. The number of attention heads in GPS and BNT-MT was set to 4, consistent with our model configuration. The convolution kernel settings for ML-Att followed the specifications provided in the original publication.

Figure 3a illustrates the prediction accuracies of four PANSS subscales and total scores and four cognitive domain scores on the COBRE sample, showing the box plot of 10 runs. ML-Att and BNT-MT generally outperform GPS-MT and GAT-MT in most prediction tasks. Compared to BNT-MT and ML-Att, our method achieves significantly improved correlations for all PANSS and cognitive predictions, with relative gains ranging from 3% to 53%, and significantly reduced MAE by 3% to 18% in most prediction tasks, as validated by Student’s t-tests (p < 0.05). We attribute these improvements to incorporating the shared attention module and uniquely interpretable decoder modules that effectively disentangle shared and task-specific features.

a Box-plot charts of Pearson’s correlation coefficients and mean absolute error (MAE) between the actual and predicted scores, comparing GAT-MT, GPS-MT, BNT-MT, ML-Att, and our proposed method across 10 runs of five-fold cross-validation on the COBRE dataset. The asterisks (“*”) indicate that our method achieves significantly higher correlations compared to all other methods, as determined by Student’s t-test, and applied a FDR correction across the full set of tests, using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (p < 0.05). b The results of the ablation study, comparing the full model against four ablated variants on the COBRE dataset. Our full model outperforms all variants in most prediction tasks, with performance improvements also confirmed by Student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

Ablation study

To further assess the effectiveness of the shared attention module and top-K pooling decoder, we compared our proposed model with four ablated variants (1) a model without the shared attention module (w/o Share); (2) a model without top-K pooling (w/o Top); (3) a model using top-K pooling to generate shared attention weights, replacing the bottleneck-like multilayer perceptron (MLP) module (Share-top); and (4) a model using the bottleneck-like MLP in the decoder to replace top-K pooling (Decoder-MLP). Figure 3b shows that incorporating both the shared attention module and top-K pooling significantly improves correlation scores and reduces MAE in most prediction tasks, confirmed by Student’s t-test (p < 0.05), underscoring the importance of capturing shared representations and performing item-specific feature selection. Moreover, replacing top-K pooling with a bottleneck-like MLP, or vice versa, results in significantly inferior performance compared to our proposed model in most prediction tasks, confirmed by Student’s t-test (p < 0.05). A potential explanation is that the bottleneck-like MLP, with its larger number of parameters, may be better suited for capturing complex relationships but is more prone to overfitting. In contrast, top-K pooling is more parameter-efficient and better adapted for modeling item-specific relationships.

Transfer learning from COBRE to IMH samples

The multi-task learning network was trained on the COBRE sample and evaluated for replicability on the IMH sample using transfer learning, given the smaller size of the IMH dataset. For the IMH sample, multi-task learning predicted the PANSS positive, negative, general psychopathology subscale, total, processing speed, attention, working memory, and verbal memory scores with Pearson’s correlations of 0.51 ± 0.04, 0.51 ± 0.05, 0.51 ± 0.04, 0.52 ± 0.05, 0.40 ± 0.03, 0.45 ± 0.04, 0.39 ± 0.07, and 0.52 ± 0.06, respectively, as shown in Fig. 2. Compared to single-task learning, multi-task learning significantly improved correlations for PANSS positive subscale (11.7%, p = 0.038), general psychopathology subscale (12.8%, p = 0.038), and total (13.0%, p = 0.040) scores, and attention (20.5%, p = 0.038), as confirmed by the student’s t-test. It also significantly reduced MAE for PANSS positive subscale (12.1%, p = 0.032), negative subscale (10.5%, p = 0.048), general psychopathology subscale (19.7%, p = 0.032), and total (7.9%, p = 0.048), demonstrating improved replicability and performance over single-task learning.

Similar to the experiment in the COBRE sample, we conducted additional analyses comparing the predicted PANSS and cognition scores between healthy controls and patients. Specifically, controls’ predicted means are 2.3, 2.9, 3.3, and 8.3 for the four PANSS subscales, compared with 4.5, 5.3, 9.9, and 20.7 for patients. All pairwise comparisons were significant (positive p = 9.7 × 10−5, negative p = 1.0 × 10−4, general p = 4.0 × 10−6, total p = 3.9 × 10−7), again demonstrating that the model reliably distinguishes patients from controls. Predicted means on processing speed, attention, working memory, and verbal memory were 72.7, 54.9, 18.7, and 42.4 for the control group, respectively, versus 65.9, 49.7, 17.3, and 34.9 for the patient group. Differences in attention (p = 0.04), working memory (p = 0.01), and verbal memory (p = 0.001) were significant; processing speed showed a non-significant trend (p = 0.07). Moreover, for the control group, the correlations between predicted and actual values of processing speed, attention, working memory, and verbal memory are 0.58, 0.34, 0.41, and 0.44 for the control group, and are 0.39, 0.45, 0.26, and 0.38 for the patient group, respectively. These results double-confirm the model’s specificity in capturing clinically meaningful variations within and between groups.

Importance maps for the prediction of each PANSS and cognition item

Figure 4a shows the importance maps used to predict four PANSS subscales and total scores and four cognitive domain scores in both samples, generated from the top-K pooling, preserving regions with the top 25% importance weights. The left panel shows similar importance maps across PANSS score scales, primarily in the prefrontal, temporal, and occipital cortices. Corresponding importance maps of PANSS scales across datasets were highly correlated, with Pearson correlations ranging from 0.63 to 0.76 (all p < 0.001), indicating the robust reproducibility of the importance maps for predicting PANSS scores. Correlations between the importance maps for the four PANSS score scales ranged from 0.70 to 0.94 (all p < 0.001) for the COBRE sample and 0.93 to 0.99 (all p < 0.001) for the IMH sample (Fig. 4b).

a The importance maps for PANSS positive, negative, general psychopathology subscale, and total scores, along with attention, working memory, verbal learning, and processing speed domain scores across both samples. b The correlation of the importance weights between the PANSS and cognition domain scores for both samples.

The right panel of Fig. 4a shows similar importance maps across cognition domain scores, primarily in the prefrontal, temporal, and parietal cortices. Importance maps for attention, working memory, processing speed, and verbal learning/memory were highly reproducible across both samples, with correlations of 0.68 to 0.78 (all p < 0.001). The four cognition domain scores exhibited similar importance maps, with correlations ranging from 0.64 to 0.80 (all p < 0.001) for the COBRE sample and 0.87 to 0.97 (all p < 0.001) for the IMH sample (Fig. 4b).

The importance maps of the PANSS scores were significantly correlated with those of the cognition domain scores, with Pearson correlations ranging from 0.11 to 0.41 (all p < 0.001) for the COBRE sample and from 0.30 to 0.57 (all p < 0.001) for the IMH sample. These results suggested shared and unique salient functional regions associated with illness severity and cognitive functioning.

Shared importance maps for the prediction of PANSS and cognitive domain scores

Figure 5a shows shared importance maps contributing to the prediction of both PANSS and cognitive domain scores for the COBRE and IMH samples, preserving the top 10% of regions based on attention weights extracted from the shared attention module. The attention weights range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater contributions. For the COBRE sample, the prefrontal cortex, middle temporal cortex, anterior insula, and inferior occipital cortex showed the highest contributions, with attention weights of 0.8–1.0 (Fig. 5a). Shared importance maps for the IMH sample were significantly correlated with those of COBRE (r = 0.86, p < 0.001), indicating robust reproducibility of the shared importance maps.

a The shared importance maps derived from the shared attention model, where higher attention weights indicate greater contributions to the prediction of both cognitive functioning and SZ severity. b The probability that each region contributes to illness severity (blue) and cognitive functioning (yellow) at the regional level, based on mappings to the Brodmann atlas for cortical regions and the AAL atlas for subcortical regions, as validated by meta-analysis. c The module-level probabilities of regional contributions to illness severity (blue) and cognitive functioning (yellow), also validated by meta-analysis.

To assess whether shared regions contribute equally to both illness severity and cognitive deficits, a meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the probability of shared important regions contributing to both parameters. For the COBRE sample, these probabilities were 0.51 for SZ and 0.49 for cognitive functioning, while both are 0.50 for the IMH sample, suggesting nearly equal contributions (around 0.50). Since the Power atlas47 does not provide anatomical labels, to evaluate region-level contributions, cortical ROIs from the Power atlas were mapped to Brodmann areas in the MNI space, which is defined based on cytoarchitectonic and generally used for regional-level analysis. We then calculated the probability that each shared important region within a given Brodmann area contributed to both clinical conditions (Fig. 5b). Similarly, subcortical and cerebellar ROIs from the Power atlas were mapped to the AAL atlas in the MNI space. Results showed that all shared regions contributed comparably to both SZ severity and cognitive functioning. In the COBRE sample, for example, the middle frontal gyrus, supplementary motor cortex, anterior prefrontal cortex, gyrus rectus, primary and secondary visual cortices, middle temporal gyrus, and dorsal cingulate cortex were associated with SZ severity with probabilities ranging from 0.47 to 0.54, and with cognitive functioning with probabilities from 0.46 to 0.53. Similar patterns were observed in the IMH sample, where all shared regions contributed nearly equally to both outcomes, with probabilities around 0.50.

To further assess module-level functional contributions, we calculated the probability that shared important regions within each brain network contributed to both clinical outcomes (Fig. 5c). At the modular level (Fig. 5c), shared regions exhibit balanced contributions to both SZ and cognition. For the COBRE sample, important regions within the default mode network (DMN) and visual network (VN) contributed to illness severity and cognitive functioning with probabilities of 0.49 and 0.51, respectively; the frontoparietal (FP) network with 0.53 and 0.47; the SN with 0.50 and 0.50; and the ventral attention (VAN) network with 0.54 and 0.46. Similar trends were observed for the IMH sample. These findings suggest that symptom severity and cognitive deficits are supported by a common functional network architecture spanning the DMN, VN, SN, FP, and VAN, each contributing nearly equally to both clinical dimensions.

Unique importance maps for the prediction of PANSS

Unique importance maps for PANSS score prediction were generated by subtracting the shared importance map from the overlapping regions of the four importance maps of PANSS score predictions in Fig. 4a, retaining only the top 10% importance weights. Regions appearing in the unique map were present in all four subscales and total scores, with weights averaged across them (Fig. 6a). The weights were further normalized by dividing by the maximum value. Higher weights indicate higher contributions to the prediction. For the COBRE sample, regions within the prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, parietal cortex, medial temporal cortex, cerebellum, and superior occipital cortex demonstrated the highest contributions (weights ranging from 0.8 to 1.0). These maps exhibited reproducibility across datasets, as indicated by a correlation of 0.38 (p < 0.05) between COBRE and IMH samples.

a The unique importance maps for SZ severity, capturing the difference between the overlapping important regions across the four PANSS subscales and total scores from top-K pooling layers and the shared importance map from the shared attention model. A higher importance weight indicates a greater contribution to prediction. b, c The probability that regions contribute to illness severity at the regional level and modular levels, as confirmed by meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis further confirmed the strong contribution of these unique regions to illness severity, with probabilities of 0.94 (COBRE) and 0.97 (IMH). At the regional level, the visuo-motor coordination area, frontal eye fields, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, associative visual cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, retrosplenial cortex, orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus, Wernicke’s area, Broca’s area, and regions in the cerebellum contributed to illness severity in the COBRE sample, with probabilities ranging from 0.62 to 0.83. Similarly, for the IMH sample, the frontal eye fields, gyrus rectus, associative visual cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus, Wernicke’s area, Broca’s area, and putamen showed probabilities ranging from 0.63 to 0.73. These results highlight the significant role of specific functional pathways within these regions in predicting illness severity, as confirmed by meta-analysis.

At the modular level, regions within the DMN, VN, FP, and SN networks for the COBRE sample contributed to illness severity prediction with probabilities of 0.99, 0.86, 0.92, and 0.71, respectively (Fig. 6b). Similarly, for the IMH sample, the FP, SN, and subcortical networks demonstrated contributions of 0.94, 0.86, and 0.63, respectively. These findings underscore the important roles of specific functional pathways within the DMN, VN, SN, and FP networks in illness severity prediction, further validated by meta-analysis.

Unique importance maps for the prediction of cognition functions

Unique importance maps for cognition function prediction were generated by subtracting the shared importance map from the overlapping regions of the four importance maps of cognitive score predictions in Fig. 4a, retaining only the top 10% importance weights. Regions appearing in the unique map were present in all four cognitive scores, with weights averaged across them (Fig. 7a). The weights were also further normalized by dividing by the maximum value. For the COBRE sample, regions in the middle frontal cortex, superior temporal cortex, insula, and subcortical areas showed the highest contributions (weights 0.8–1.0, left panel of Fig. 7a) to predicting cognitive functioning. For the IMH sample, regions in the superior frontal and parietal cortices also demonstrated high contributions (weights 0.85–0.98). However, importance maps from the IMH and COBRE samples were only weakly correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.17, p = 0.08), possibly due to differences in cognitive assessments between the samples.

a The unique importance maps for cognitive functioning, capturing the difference between the overlapping important regions across the four cognition domain scores from top-K pooling layers and the shared importance map from the shared attention model. A higher attention weight indicates a greater contribution to prediction. b, c The probability that regions contribute to cognitive functioning (in yellow), as confirmed by meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis confirmed strong associations between these regions and cognitive functioning, with probabilities of 0.98 for the COBRE sample and 0.99 for the IMH sample. At the regional level, contributions from the COBRE sample included the superior parietal lobe, inferior temporal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, ventral anterior cingulate cortex, perirhinal cortex, fusiform gyrus, auditory cortex, anterior middle frontal gyrus, insula, caudate, and putamen, with probabilities ranging from 0.66 to 0.92. For the IMH sample, contributing regions included the primary somatosensory cortex, primary motor cortex, inferior temporal gyrus, angular gyrus, gyrus rectus, secondary visual cortex, orbital part of the inferior frontal gyrus, retrosplenial cortex, and insula, with probabilities ranging from 0.66 to 0.90. These results highlighted the significant role of specific functional pathways within these regions in cognition functioning prediction, as confirmed by meta-analysis.

At the modular level (Fig. 7b), analyses revealed that for the COBRE sample, the memory retrieval (MER), SN, subcortical, VAN, and dorsal attention (DAN) networks contributed to cognitive functioning predictions with probabilities of 0.66, 0.97, 0.81, 0.93, and 0.66, respectively. For the IMH sample, the SM, cingulo-opercular, auditory, DMN, and SN networks contributed with probabilities of 0.97, 0.73, 0.92, 0.99, and 0.66, respectively. These findings emphasize the importance of functional pathways within the SN, VAN/DAN, subcortical, MER, and related networks for accurate cognitive functioning prediction.

Replication on the SRPBS dataset

To further evaluate the replicability of our framework, we applied it to a larger SRPBS dataset comprising 83 patients with SZ and 123 healthy controls (demographics in Table 1). The multi-task learning network predicted PANSS positive, negative, general psychopathology subscales, and total scores, as well as processing speed, attention, working memory, and verbal memory, achieving Pearson correlations of 0.43 ± 0.03, 0.47 ± 0.03, 0.46 ± 0.03, 0.47 ± 0.04, 0.43 ± 0.02, 0.44 ± 0.02, 0.33 ± 0.03, and 0.36 ± 0.03, respectively (Fig. 8a). Compared with single-task learning, multi-task learning significantly improved correlations for the PANSS positive (15.9%, p = 0.036), negative subscale (21.3%, p = 0.008), general psychopathology subscale (20.3%, p = 0.014), total score (12.6%, p = 0.005), and attention (21.0%, p = 0.014) (Student’s t-test with Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction). Furthermore, multi-task learning significantly reduced MAE values by 16.2% (p = 0.001) for PANSS positive subscale score, 17.1% (p = 0.001) for PANSS negative subscale score, 18.2% (p < 0.001) for general psychopathology subscale score, 13.6% (p = 0.001) for total score, and 8.4% (p = 0.005) for attention domain scores compared to single-task learning. These improvements demonstrate that our framework’s predictive power replicates on a larger, independent cohort.

a The box-plot charts of Pearson’s correlation coefficients and MAE between the actual and predicted scores using single-task learning (green) and multi-task learning (orange) over 10 runs of five-fold cross-validation on the SRPBS sample (n = 206). “*” indicates that multi-task learning significantly improves the accuracy compared to single-task learning (Student’s t-test with FDR correction via the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure, p < 0.05). b The distinct and shared importance maps derived for the SRPBS sample, where higher attention weights indicate greater contributions to the prediction of both cognitive functioning and SZ severity. c The prediction performance on a dataset of healthy subjects—HCP (n = 875). The model pretrained on the COBRE dataset achieved significantly lower MAE values—closer to zero—than the model trained from scratch. Moreover, pretraining significantly improved prediction correlations across all four cognitive domains and substantially reduced MAE for processing speed and working memory. “*” denotes these improvements (Student’s t-test with FDR correction, p < 0.05).

We then visualized the key brain regions identified in the SRPBS sample (Fig. 8b). The pattern of important regions and prediction performance remained largely consistent with those from the COBRE dataset. To quantify this consistency, we correlated importance weights from the SRPBS sample with those from the COBRE sample. The Pearson correlations were 0.62 (p < 0.001), 0.47 (p < 0.001), and 0.23 (p < 0.001) for SZ prediction, cognitive prediction, and shared representations, respectively. These findings confirm the robustness of our results.

Validation on a healthy sample

To evaluate whether our framework captures functional variability associated with normative cognition—and to assess its specificity for schizophrenia—we validated it on 875 healthy controls from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) dataset48, which includes rs-fMRI and cognitive assessments. We mapped HCP cognitive-battery scores for processing speed, working memory, verbal memory, and attention to the domains in our study. The model was first pretrained on the COBRE dataset and then fine-tuned only at the output layer using the HCP data. Finally, we compared its predictions to those of an otherwise identical model trained without the pretrained parameters.

Since PANSS scores for HCP participants are all set as zero, we did not report correlations for PANSS predictions. The correlation and MAE performance are presented in Fig. 8c. Both with and without pretraining, the model yielded near-zero predictive performance across the four PANSS scores in the healthy HCP sample, as expected. However, the pretrained model achieved significantly lower MAE values, closer to zero. Moreover, the pretrained model significantly improved the prediction correlations across all four cognitive domains and substantially reduced the MAE for processing speed and working memory, compared to the model trained without pretraining. These results demonstrate the model’s capacity to capture normative functional variability beyond clinical populations. This additional validation strengthens the generalizability of our framework and highlights its relevance for both clinical and normative cognitive phenotyping.

Discussion

This study aimed to disentangle shared brain functional patterns associated with SZ illness severity and cognitive deficits, as well as distinct regional associations specific either to illness severity or variability in cognitive functioning. We proposed a graph-based multi-task deep learning framework, simultaneously predicting PANSS scores (negative, positive, general psychopathology subscales, total) and cognitive domain scores (attention, processing speed, working memory, verbal learning). Our method demonstrated superior predictive performance compared to single-task learning and state-of-the-art multi-task learning methods. Interpretation of predictive results across the COBRE and IMH datasets revealed overlapping implicated regions. Furthermore, meta-analysis confirmed both shared and distinct roles of these brain regions, highlighting common and unique functional neural correlates underlying SZ symptom severity and cognitive deficits. The predictive performance and identification of shared and distinct brain regions are replicable on the SRPBS dataset.

Traditional rs-fMRI studies have primarily relied on statistical approaches for group-wise comparison49. More recently, the focus has shifted toward predictive modeling, with deep learning emerging as a powerful tool to uncover complex relationships in rs-fMRI data for disease and cognition prediction27,28. Graph-based learning methods closely align with the brain’s network topology by incorporating neighborhood relationships, preserving information integrity, and capturing node-level abnormalities underlying SZ pathophysiology and cognitive deficits. Among these methods, graph convolutional networks (GCNs)29 capture latent, nonlinear relationships in graph-structured data by aggregating information from neighboring nodes based on connectivity strength, thereby exploiting the spatial relationships between brain regions. They have demonstrated success in classifying psychiatric disorders33,34 and predicting cognition32,50 based on FC. However, conventional GCNs treat all neighboring nodes equally during aggregation, which causes computational inefficiencies and redundant information. To address this, GATs51 were developed as an extension of GCNs by incorporating attention mechanisms to learn the relative importance of different neighbors for each node. This enables more expressive feature learning and has been successfully applied to SZ diagnosis30 and cognitive prediction31. More recently, transformer-based methods have been adapted for graph representation50,52, leveraging the capabilities of attention mechanisms to model complex dependencies. One such approach, the GPS graph transformer, integrates transformer mechanisms with GCN-style message passing and has achieved state-of-the-art performance across various graph-based tasks53,54,55. Our framework leverages GPS and GAT as shared and task-specific encoders, respectively, to capitalize on the strengths of both models.

Multi-task learning provides a promising strategy to leverage shared representations across multiple tasks, thereby improving generalization and performance35,36,37,38,39. Recently, a transformer multi-task learning network38 introduced a brain transformer-based model using a shared encoder to predict multiple cognitive scores. Such architectures are well-suited for simultaneously estimating SZ symptom severity and cognitive deficits, such as attention, working memory, verbal learning, and processing speed, by exploiting inter-task relationships. However, although designed to utilize shared features, these models often fail to fully exploit task-specific information in the latent space, limiting their capacity to extract the complementary features. To address this issue, our previous study 39 proposed a multi-level multi-task network by incorporating a bottleneck-like MLP-based mechanism that captures both shared and task-specific features for cognitive prediction, based on the convolutional neural network (CNN). While effective in exploring the shared and specific biomarkers, this approach was implemented based on the CNN backbone, which cannot effectively model the spatial relationship of brain connectome data. In contrast, graph-based methods are better suited for capturing these topological structures. Therefore, there remains a critical need for a method that effectively utilizes a graph-based backbone to extract both shared and unique important regions associated with SZ illness severity and cognitive function, a capability that remains scarce in current literature. Our proposed graph-based multi-task framework addresses this gap by effectively leveraging both complementary and shared information, resulting in an improvement of 5%–25% in prediction accuracy compared to single-task methods. These findings suggest that cognitive features may enhance the prediction of symptom severity, and vice versa. Moreover, our method significantly outperforms several state-of-the-art multi-task learning approaches, demonstrating the robustness and efficacy of the proposed framework.

Note that, in several multi-task learning works, a task trade-off is observed, where optimizing one task can sometimes adversely affect the performance of another. We also analyze the training process of our framework. In the early training stages, improvements in the correlation scores for working memory and verbal learning were accompanied by declines in other tasks, and vice versa. However, as training progressed, the trends in working memory and verbal learning became more aligned with those of the other tasks. We infer that this pattern may result from the incorporation of shared mechanisms in the model, where complementary features across tasks help mitigate imbalanced training effects.

This study identified the supplementary motor area, middle frontal gyrus, anterior prefrontal cortex, gyrus rectus, primary/secondary visual cortex, middle temporal gyrus, and dorsal cingulate cortex, which are in key implicated brain networks—SN, DMN, VS, and FP networks, as shared salient contributors to predictions of both PANSS scores and cognitive domain scores. Meta-analysis confirmed that these markers contributed nearly equally to both illness severity and cognitive functioning (probabilities around 0.5). Specifically, functional change in the supplementary motor area has been observed in patients with SZ20, and our study further confirmed that this area is closely related to the cognitive deficits in SZ. The anterior prefrontal cortex within the SN, as well as the gyrus rectus, middle temporal gyrus, and dorsal cingulate cortex within the DMN, have previously been linked to various psychotic symptoms56 and cognitive domains57,58. Additionally, the middle frontal gyrus, associated with FP and DMN networks, supports executive control, while the primary and secondary visual cortices, associated with the VS network, facilitate perception and internal model construction necessary for executive processing in SZ59,60. These findings support that cognitive deficits are central to SZ psychopathology, characterized by shared brain functional alterations linked to both symptom severity and cognitive deficits. These regions may serve as promising targets for therapeutic interventions aimed at improving both clinical symptoms and cognitive performance. Given this overlap, cognitive remediation strategies61 may benefit from tailoring training paradigms to distinct cognitive profiles rather than adopting a uniform approach. Whether profile-specific remediation can enhance treatment efficacy or patient adherence remains an important question for future investigation.

Unique brain functional changes specifically associated with SZ symptom severity were identified in regions such as the frontal eye fields, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, associative visual cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, retrosplenial cortex, orbital inferior frontal gyrus, Wernicke’s area, Broca’s area, cerebellar regions, and areas involved in visuo-motor coordination. These regions are situated within DMN, VS, SN, FP, and subcortical networks. Meta-analysis confirmed that these regions substantially contributed to SZ symptoms. Alterations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex are associated with familial risk of SZ62, while the posterior cingulate cortex may increase internal focus, favoring memory-based perceptions over sensory inputs that typically ground individuals in reality63. Functional alterations involving the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and retrosplenial cortex within DMN have been observed in SZ, indicating potential disrupted internal network communication64,65. Our study further confirmed their unique power in predicting SZ symptom severity. Additionally, neurobiological studies have shown that alterations in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway—particularly in the prefrontal, orbitofrontal, and cingulate cortices—are more closely associated with psychotic symptoms23,24. Our study also confirmed that functional alterations in these regions can be observed and are related to the severity of SZ symptoms. Moreover, we found that Wernicke’s area, Broca’s area, and the putamen, which are closely associated with auditory and verbal hallucination66, also emerged as specific predictors of SZ. Extending previous findings, our study further confirmed that the above regions across DMN, VS, SN, FP, and subcortical networks are more closely related to SZ symptom severity than to cognitive impairments. The “unique” patterns associated with SZ symptom severity may offer important insights into its clinical heterogeneity. For example, distinct functional alterations in regions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, Broca’s area, and posterior cingulate cortex—each uniquely linked to symptom severity—may help delineate subtypes characterized by predominant positive or negative symptoms67. Beyond traditional network-level analyses, our study not only identified the key networks associated with SZ symptom severity but also pinpointed the specific contributing regions within each network. Moreover, these unique patterns may help explain treatment resistance in certain patients and underscore the potential of these regions as targets for future research in treatment development and personalized intervention.

Brain functional changes uniquely linked to cognitive domains predominantly involved the superior parietal lobe, inferior and superior temporal gyri, ventral anterior cingulate cortex, perirhinal cortex, auditory cortex, anterior middle frontal gyrus, insula, caudate, and putamen, associated with DAN, VAN, and SN networks. These regions significantly contributed to attention, processing speed, verbal learning, and working memory. Dysfunction in the perirhinal cortex notably affects cognitive abilities related to object recognition, spatial memory, and fine-grained object discrimination68. Early auditory processing within the auditory cortex has been linked to variability in various cognitive functions, including social and neuro-cognition69. Functional alterations in the putamen have been observed in SZ, and our findings further suggest that these changes may be more closely related to cognitive variability in SZ patients rather than to symptom severity. Furthermore, the superior parietal lobe within the DAN network supports orienting and sustaining attention toward relevant external information70, while the superior temporal gyrus within the VAN network mediates automatic reorienting responses to unexpected stimuli, crucial for effective DAN functioning71. Together, they form the “top-down” attention mechanism, whose disruption underlies attention variability72. Alterations in the ventral anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and anterior middle frontal gyrus (associated with SN/VAN) have been linked to improvements in processing speed and overall cognitive performance73,74. In conclusion, the above regions identified in our study represent unique neural correlates of cognitive functioning and may underlie the observed nature of cognitive variability, being distinct from SZ-specific cognitive deficits, which may inform cognitive profiling and predict functional outcomes in daily living or employment.

These results highlighted potential applications of our graph-based multi-task learning framework for predicting and analyzing psychopathology severity and cognitive functioning. However, our study had limitations. The COBRE and IMH datasets used different tools for cognitive assessments, which can lead to variations in scoring. Transfer learning techniques and decoder optimization reduced these differences, demonstrating the feasibility of cross-dataset prediction. However, validation in larger samples with correlation with other relevant clinical measures, such as symptoms and cognitive functioning response to interventions, can proffer insights for the use of brain functional changes in prognostication at the regional level. Moreover, our study adopts a simplified linear-progression model of SZ, from normative cognitive functioning to cognitive impairment and then to increased symptom severity. However, because SZ is highly heterogeneous, the extent of cognitive impairment differs markedly across subtypes. For example, patients with paranoid-type SZ demonstrate relatively preserved cognitive function compared to those with undifferentiated or residual-type SZ67. A more detailed analysis of these subtype-specific trajectories would therefore be a valuable avenue for future research.

In conclusion, this study provided a graph-based multi-task deep learning framework enabling relatively robust and replicable predictions of SZ illness severity and cognitive functioning. We successfully identified and disentangled both shared functional brain patterns associated with illness severity and cognitive deficits, as well as distinct regions uniquely linked to each condition. Taken together, our findings suggest that both shared and unique functional signatures could contribute to more refined diagnostic stratification, facilitate prognosis by identifying individuals at greater risk for severe cognitive impairment or clinical decline, and support personalized treatment strategies (e.g., neuromodulation or cognitive training) targeting specific neural circuits. Future research should investigate whether these identified functional alterations generalize to other clinical parameters, such as illness duration and medication status, thereby expanding the utility and impact of this analytical approach.

Methods and materials

Participants

This study utilized three datasets with a total of 378 subjects (160 SZ subjects and 218 healthy controls) with measurements of cognitive functioning and illness severity scores for subjects with SZ. The COBRE dataset, used for model training and validation, included anatomical and functional MR data from 60 individuals with SZ and 75 healthy controls, aged from 18 to 66. Cognitive functioning in domains of working memory, processing speed, and verbal learning was assessed using the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery44, and the attention domain was assessed using the BACS45. The IMH dataset, used for external validation, included 17 patients with SZ and 20 healthy controls, aged from 22 to 58, with cognitive functioning measured using the BACS, which included the same domains, such as working memory, processing speed, attention, and verbal memory. Illness severity in both datasets was assessed using the PANSS. This study involved 83 patients with SZ and 123 healthy controls, aged from 19 to 67, from the Japanese SRPBS dataset46, used for replication. Cognitive functioning domains were measured using BACS, which included the same domains, such as working memory, processing speed, attention, and verbal memory. Illness severity in all datasets was assessed using the PANSS. Table 1 shows the demographic details, PANSS, and cognitive functioning scores, with details of distributions and correlations shown in the Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2. The Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of the University of New Mexico, IMH, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, and Kyoto University approved this study, and informed consent was obtained from study participants.

This study involved 875 subjects from the HCP48, including behavioral and 3 T MRI data for healthy controls validation. All research involving HCP adult data was conducted in accordance with ethical standards established by the IRB at Washington University in St. Louis and at the University of Minnesota. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. Cognitive functioning in domains of working memory and processing speed was assessed using the NIH Toolbox - Pattern Completion Processing Speed (mean ± SD 114.2 ± 14.9), List Sorting Working Memory (111.1 ± 11.2), and in domains of attention and verbal learning was assessed using Short Penn Continuous Performance Test (57.2 ± 4.2) and Penn Word Memory Test (35.6 ± 3.0).

Image acquisition and preprocessing

In the IMH dataset, a 3 T Philips Achieva scanner with an 8-channel head coil was used. Both datasets included T1-weighted and rs-fMRI images. Raw T1 and rs-fMRI images of the COBRE, SRPBS, and HCP datasets are publicly available. T1-weighted images were processed with FreeSurfer75, and rs-fMRI images were processed using fMRIprep, with details described in the Supplementary Document. This study employed a Power brain atlas47 with 264 ROIs. Functional brain networks were represented as 264 × 264 FC matrices, with elements calculated using Pearson’s correlation between brain region time series. To remove the effects of age and gender on FC, we modeled age and gender as covariates within the ComBat function76 and regressed out their effects on FC for each dataset. To further evaluate the effectiveness of regressing out sex effects, we compared the prediction performance of the full dataset (with sex regressed out) to that of a sex-paired subsampled dataset. No significant differences in predictive performance were observed between the two datasets. Detailed experimental settings and results are provided in the Supplementary Document.

Graph representation construction

The brain FC can be naturally modeled as a graph G with brain ROIs as nodes V and the connectivity between these ROIs as edges A (Fig. 1b). A FC graph \({\bf{G}}=({\bf{V}},{\bf{A}},{\bf{X}})\) was constructed from the rs-fMRI data for each participant. \({\bf{A}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times N}\) represented the adjacency matrix, defined as a thresholded FC matrix that preserves only the highest 10% positive edges for each node to maintain its connection sparsity77. \({\bf{X}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times D}\) represented the features of N nodes, defined as their Pearson correlation with all other nodes in our study. D was the length of node features. Our previous study has shown that the connectivity profiles reflect the comprehensive connection information in the brain network78, and it has been demonstrated to be the most effective node feature through extensive experiments79.

Interpretable graph-based multi-task prediction

This study proposed an interpretable graph-based multi-task learning framework on FC to predict PANSS positive, negative, general psychopathology subscales, and total scores, as well as four cognitive domain scores simultaneously. Specifically, the framework employs graph transformer layers as encoders for both SZ and cognition prediction. To disentangle shared and distinct functional patterns, we introduce a shared attention module based on a bottleneck-like MLP mechanism, which first compresses the number of nodes to extract salient shared features, then expands them back to the original space to retain important regional information. Additionally, we apply a top-K pooling decoder to preserve task-specific important regions, selecting the most informative features for each prediction task. Figure 1c illustrates the overall framework of neural network models in this study. We introduce each module in detail as follows.

Common encoder

The common encoder was designed to capture features shared between illness severity and cognitive functioning. It consisted of a single graph transformer convolution layer, specifically employing the general, powerful, scalable graph transformer (GPS)53, followed by a ReLU activation function. The GPS convolution integrates the strengths of traditional transformers and spatial graph convolutions, enabling effective learning of representations across nodes and reducing the over-smoothing issue seen in traditional GCNs in various tasks53,54,55. Here, we did not explicitly incorporate additional positional or structural encodings beyond the implicit spatial structure captured by the graph convolutional layers. Our rationale for this choice stems from two considerations. First, in functional brain connectivity graphs, the adjacency matrix already captures pairwise relationships among brain regions based on functional correlation strengths, and node features (connectivity profiles) implicitly encode topological context. Second, since the Power atlas defines fixed node positions across subjects, spatial coordinates are constant and not learned or individualized.

Cognition encoder and PANSS encoder

The cognitive- and PANSS-specific encoders were designed to extract features relevant to predicting cognitive functioning and illness severity. Each encoder consisted of one layer of graph attention (GAT)51 convolution, and a ReLU activation function. GAT convolution uses self-attention to assign different weights to neighboring nodes, effectively enabling nodes to focus on relevant features without needing to know the graph structure upfront. To avoid over-smoothing of the node features in the aggregation of neighborhoods, we adopted a one-layer GAT convolution in the encoder. Our experiments demonstrated that combining a GPS-based common encoder with GAT-based specific encoders achieved superior performance compared to other encoder combinations, such as GAT + GAT (GAT-MT) or GPS + GPS (GPS-MT), as shown in Fig. 3a.

Shared attention model

The shared attention model identifies salient brain regions contributing to both illness severity and cognitive functioning. It consists of a convolution operation, a bottleneck-like MLP, and a sigmoid activation function, as previously adopted in our earlier study39. Initially, features generated by the PANSS and cognition encoders are concatenated, resulting in a combined feature matrix of size \(N\times 2D^{\prime}\), where N is the number of nodes and \(D^{\prime}\) is the dimension of features for predicting illness severity or cognitive functioning. Then, a convolution operation with a kernel size of \(1\times 2D^{\prime}\) was applied to the concatenated features to fuse both features for predicting illness severity and cognitive functioning while reducing the dimension from \(2D^{\prime}\) to 1. To capture the most important regions contributing to both illness severity and cognitive functioning prediction, a bottleneck-like MLP with two fully connected layers was employed to generate the attention weights. The first fully connected layer reduced the feature dimension from N nodes to N/r hidden nodes, compressing the feature while preserving the most important information. The second fully connected layer mapped N nodes back to N/r hidden nodes, learning dependencies among all nodes. A sigmoid function was then used to threshold the learned attention weights, where higher attention weights indicated a larger contribution to prediction and lower weights indicated a smaller contribution. Significant shared feature for illness severity and cognitive functioning prediction was emphasized by multiplying the learned attention weights with the features generated by the cognition or PANSS encoders, while non-related features were compressed. To provide complementary information between illness severity and cognitive functioning, we cross-combined the significant features from the shared attention model with the specific features from the encoder models. Specifically, for illness severity prediction, we added the significant features for cognitive functioning prediction to the features generated by the PANSS encoder. For cognitive functioning prediction, we added the significant features for illness severity prediction to the features generated by the cognition encoder.

Decoder

For each prediction, the decoder consisted of a top-K pooling operation. The top-K pooling mechanism acted as a node sampling procedure, reducing the total number of nodes to optimize the target objective. It employed a trainable projection vector to compute a score for each node. The top K nodes were retained based on their scores, with higher-scoring nodes selected for prediction and lower-scoring nodes discarded. Therefore, each score reflected the importance of the corresponding node for the prediction. The ablation study in Fig. 3b shows that the combination of the bottleneck-like MLP and top-K pooling achieves the best performance compared to using either interpretable technique alone.

Output layer

Each prediction uses an output layer comprising two fully connected layers, dropout, and a ReLU activation function, allowing simultaneous prediction of all eight scores.

Loss function

Each task was formulated as a regression problem using root mean squared error (RMSE) loss, and the total loss was computed as the unweighted sum of the eight individual task losses. Specifically, the loss function was described as

\({L}_{c}\) is defined as the summation of RMSE between actual and predicted scores of the four cognition, and \({L}_{p}\) is defined as the summation of RMSE between actual and predicted scores of the four PANSS scales. We tuned λ over the range \([\frac{1}{6},\,\frac{1}{5},\,\frac{1}{4},\,\frac{1}{3},\,\frac{1}{2},\,1,\,2,\,3,\,4,\,5,\,6]\) and evaluated the correlation between actual and predicted scores for all eight tasks. The final value of λ was selected based on both the magnitude of the correlations and the stability of performance across tasks. Specifically, we calculated the ratio of the mean correlation to the standard deviation across the eight tasks for each λ value. A higher ratio indicates better overall performance, balancing accuracy and consistency. λ = 2 yielded the highest ratio, with a relatively high mean correlation and low variability across tasks, and was therefore chosen as the final setting, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Training and validation

The COBRE dataset was designed as a population-based study, featuring a large sample size and a broader range of PANSS scores. Five-fold cross-validation was employed, and the experiment was repeated 10 times. Pearson’s correlation and MAE between the actual and predicted scores were used to assess prediction accuracy.

Transfer learning for cross-dataset validation

This study employed transfer learning from the COBRE sample to the IMH and SRPBS samples, in which the prediction model was initially trained on the COBRE data and subsequently fine-tuned on the output layer using the other data. Transfer learning was necessary due to the small sample size of the IMH dataset, which helped harmonize measurement scales across different datasets.

Implementation details

All the models were implemented using Python 3.8 and PyTorch 1.12 on an NVIDIA A100 GPU. To avoid overfitting, we introduced dropout layers after the readout layer and between two fully connected layers in the output layer, with a dropout rate of 0.5. Moreover, we adopted L2-norm regularization with a weight setting of 0.001 and employed early stopping to prevent overfitting. The Adam optimizer was used, with the batch size set to 10. For the regression task, the learning rate and number of epochs were set to 0.0001 and 40, respectively. The details of parameter settings are in the Supplementary Document.

The generation of importance maps

The neural networks were designed for interpretability, using the shared attention model and top-K pooling (Fig. 1c) to identify shared and unique brain regions associated with illness severity and cognitive deficits. Shared importance maps were derived from attention weights in the shared attention model. The unique importance maps were generated by subtracting the shared importance maps from overlapping the importance maps of the four cognitive domain scores or the four PANSS subscales and total scores obtained from top-K pooling layers. Importance weights in the shared importance map are based on attention weight, whereas in the unique importance map, they represent the averaged weights across the four scores. Higher weights in either map highlight key brain features, indicating potential biomarkers for SZ severity or cognitive deficits.

Meta-analysis on the importance maps of SZ

A meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the validity of the shared and unique importance maps for SZ and cognition by calculating their contributions toward illness severity and cognitive functioning using the BrainMap database41. The BrainMap database provides MNI coordinates for each experiment, which were subsequently mapped onto the 264 ROIs used for FC in this study, identifying activated and non-activated ROIs across experiments to assess their relevance to symptom severity and cognitive functioning. We investigated the probability of each importance map contributing to both clinical parameters. Cognitive functioning studies focusing on attention, working memory, and language were included to align with this study’s cognitive domain scores, with relevant studies extracted using keywords from the Supplementary Table S1 and an age range of 18–66 years, according to participants’ age in our study. As a result, 162 functional studies on SZ and 118 functional studies on cognitions were obtained. A Naive Bayes classifier80 was used to compute the probabilities of the overall importance map, each region’s, and each module’s importance maps contributing to illness severity and cognitive functioning.

Statistics and reproducibility

Demographic and clinical variables were reported as mean and standard deviation. All significant results were confirmed using Student’s t-test and applied a FDR correction using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure with a significance level of p < 0.05. Reproducibility was assessed in both the IMH and SRPBS datasets, and we found that prediction performance and importance weights were consistent across cohorts.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Center for Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) Study (https://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/retro/cobre.html), the Human Connectome Project (HCP) study (https://www.humanconnectome.org/), and the Japanese SPRBS study (https://bicr-resource.atr.jp/srpbsopen/).

Code availability

Software used in the data analyses includes FreeSurfer 6.0 (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu), fMRIprep (https://fmriprep.org/en/stable/), Sleuth (https://www.brainmap.org/sleuth/), and MATLAB. Custom algorithms for the interpretable graph-based multi-task deep learning method were written in Python 3.8 and are available at the GitHub repository (https://github.com/jingxia001/MT-SZ/tree/main).

References

Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019permalink/27a7644e8ad28e739715382d31e77589dd7 (2021).

McCutcheon, R. A., Keefe, R. S. & McGuire, P. K. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia aetiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 1902–1918 (2023).

Bowie, C. R. & Harvey, P. D. Cognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2, 531–536 (2006).

Austin, M. P., Mitchell, P. & Goodwin, G. M. Cognitive deficits in depression possible implications for functional neuropathology. Br. J. Psychiatry 178, 200–206 (2001).

Broyd, S. J. et al. Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 33, 279–296 (2009).

Fornito, A., Yoon, J., Zalesky, A., Bullmore, E. T. & Carter, C. S. General and specific functional connectivity disturbances in first-episode schizophrenia during cognitive control performance. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 64–72 (2011).

Huang, C.-C. et al. Transdiagnostic and illness-specific functional dysconnectivity across schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 5, 542–553 (2020).

Adhikari, B. M. et al. Functional network connectivity impairments and core cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 4593–4605 (2019).

Sheffield, J. M. & Barch, D. M. Cognition and resting-state functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 61, 108–120 (2016).

Walther, S. et al. Aberrant hyperconnectivity in the motor system at rest is linked to motor abnormalities in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 43, 982–992 (2017).

Antoniades, M. et al. Verbal learning and hippocampal dysfunction in schizophrenia a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 86, 166–175 (2018).

Du, Y., Niu, J., Xing, Y., Li, B. & Calhoun, V. D. Neuroimage analysis methods and artificial intelligence techniques for reliable biomarkers and accurate diagnosis of schizophrenia achievements made by Chinese scholars around the past decade. Schizophr. Bull. sbae, 110 (2024).

Passiatore, R. et al. Changes in patterns of age-related network connectivity are associated with risk for schizophrenia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2221533120 (2023).

Mehta, U. M. et al. Resting-state functional connectivity predictors of treatment response in schizophrenia—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 237, 153–165 (2021).

Cai, M. et al. Disrupted local functional connectivity in schizophrenia an updated and extended meta-analysis. Schizophrenia 8, 93 (2022).

Reid, M. A. et al. Assessments of function and biochemistry of the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 625–633 (2010).

Homan, P. et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy investigations of functionally defined language areas in schizophrenia patients with and without auditory hallucinations. NeuroImage 94, 23–32 (2014).

Sakurai, T. et al. Converging models of schizophrenia—Network alterations of prefrontal cortex underlying cognitive impairments. Prog. Neurobiol. 134, 178–201 (2015).

He, Z. et al. Aberrant intrinsic brain activity and cognitive deficit in first-episode treatment-naive patients with schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 43, 769–780 (2013).

Yang, F. et al. Correlation of abnormalities in resting state fMRI with executive functioning in chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 299, 113862 (2021).

Picó-Pérez, M. et al. Multimodal meta-analysis of structural gray matter, neurocognitive and social cognitive fMRI findings in schizophrenia patients. Psychol. Med. 52, 614–624 (2022).

Karlsgodt, K. H., Sun, D. & Cannon, T. D. Structural and functional brain abnormalities in schizophrenia. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 19, 226–231 (2010).

McCutcheon, R. A., Abi-Dargham, A. & Howes, O. D. Schizophrenia, dopamine and the striatum from biology to symptoms. Trends Neurosci. 42, 205–220 (2019).

Xu, H. & Yang, F. The interplay of dopamine metabolism abnormalities and mitochondrial defects in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 464 (2022).

Zeng, J. et al. Neural substrates of reward anticipation and outcome in schizophrenia a meta-analysis of fMRI findings in the monetary incentive delay task. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 448 (2022).

Howes, O. D. & Kapur, S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia version III—the final common pathway. Schizophr. Bull. 35, 549–562 (2009).

de Filippis, R. et al. Machine learning techniques in a structural and functional MRI diagnostic approach in schizophrenia a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 15, 1605–1627 (2019).

Zeng, L.-L. et al. Multi-site diagnostic classification of schizophrenia using discriminant deep learning with functional connectivity MRI. EBioMedicine 30, 74–85 (2018).

Zhang, S., Tong, H., Xu, J. & Maciejewski, R. Graph convolutional networks a comprehensive review. Comput. Soc. Netw. 6, 1–23 (2019).

Yu, R., Pan, C., Fei, X., Chen, M. & Shen, D. Multi-graph attention networks with bilinear convolution for diagnosis of schizophrenia. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27, 1443–1454 (2023).

Baek, I., Namgung, J. Y., Park, Y., Jo, S. & Park, B. -y Identification of functional dynamic brain states based on graph attention networks. NeuroImage 11, 121185 (2025).

Huang, S.-G., Xia, J., Xu, L. & Qiu, A. Spatio-temporal directed acyclic graph learning with attention mechanisms on brain functional time series and connectivity. Med. Image Anal. 77, 102370 (2022).

Lei, D. et al. Graph convolutional networks reveal network-level functional dysconnectivity in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 48, 881–892 (2022).

Etemadyrad, N. et al. Functional connectivity prediction with deep learning for graph transformation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 35, 4862–4875 (2022).

Zhang, Y. & Yang, Q. An overview of multi-task learning. Natl. Sci. Rev. 5, 30–43 (2018).

Liang, W. et al. Exploiting task relationships for Alzheimer’s disease cognitive score prediction via multi-task learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 152, 106367 (2023).

Huang, Z.-A. et al. Federated multi-task learning for joint diagnosis of multiple mental disorders on MRI scans. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 70, 1137–1149 (2022).

Kan, X., Cui, H., Han, K., Guo, Y. & Yang, C. Multi-task Learning for Brain Network Analysis in the ABCD study. In Proc. IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (2024).

Xia, J., Chen, N. & Qiu, A. Multi-level and joint attention networks on brain functional connectivity for cross-cognitive prediction. Med. Image Anal. 90, 102921 (2023).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. A. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 261–276 (1987).

Laird, A. R. et al. Neural architecture underlying classification of face perception paradigms. Neuroimage 119, 70–80 (2015).

Mayer, A. R. et al. Functional imaging of the hemodynamic sensory gating response in schizophrenia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 34, 2302–2312 (2013).

Chan, Y. H., Yew, W. C., Chew, Q. H., Sim, K. & Rajapakse, J. C. Elucidating salient site-specific functional connectivity features and site-invariant biomarkers in schizophrenia via deep neural networks. Sci. Rep. 13, 21047 (2023).

Nuechterlein, K. H. et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, Part 1 test selection, reliability, and validity. Am. J. Psychiatry 165, 203–213 (2008).

Keefe, R. S. et al. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr. Res. 68, 83–297 (2004).

Tanaka, S. C. et al. A multi-site, multi-disorder resting-state magnetic resonance image database. Sci. Data 8, 227 (2021).

Power, J. D. et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 72, 665–678 (2011).

Van Essen, D. C. et al. The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project an overview. Neuroimage 80, 62–79 (2013).

Worsley, K. J. et al. A general statistical analysis for fMRI data. Neuroimage 15, 1–15 (2002).