Abstract

Nucleotide modifications deviate nanopore sequencing readouts, therefore generating artifacts during the basecalling of sequence backbones. Here, we present a reference-guided, iterative approach to polish modification-disturbed basecalling results. We show that such an approach is uniquely suitable for training biomolecule-specific high-accuracy basecallers, by improving the basecalling of both artificially-synthesized and real-world molecules. With demonstrated efficacy and reliability, we exploit the approach to precisely basecall therapeutic RNAs consisting of artificial or natural modifications. We first analyzed vaccine mRNAs, which are artificially modified to promote stability and reduce immunogenicity. Specifically, we quantified the sequence purity and integrity, the two most important quality metrics to be controlled during mRNA vaccine production. We also analyzed BioRNAs, which are human tRNA-based carriers for therapeutic RNA interference (RNAi) agents. Specifically, we examined modification hotspots, which are naturally incorporated in vivo during BioRNA production and essential for therapeutic efficacy. Our analysis expands the scope of therapeutic RNA quality control, from the conventional sequence-level to the current modification status-level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In nanopore sequencing, basecalling refers to the process of interpreting nucleotide sequence backbones from ionic current signals1. Basecallers released by Oxford Nanopore Technologies, the company that commercialized nanopore sequencing, rely upon deep learning models. For instance, the Guppy basecaller, which was developed for the earlier R9.4.1 flowcell chemistry, builds on the long short-term memory network. The state-of-the-art research-oriented Bonito and production-ready Dorado basecallers, which are compatible with the latest R10.4.1 (for DNA sequencing) and RNA (for RNA sequencing) flowcells, are built on the transformer network. Previous studies2,3,4,5,6,7,8 have confirmed that the accuracy of these basecallers is highly likely to be compromised by chemically modified nucleotides, which can be faithfully preserved by native nanopore sequencing libraries. For instance, Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK114, for DNA sequencing) and Direct RNA Sequencing Kit (SQK-RNA004, for RNA sequencing) directly ligate candidate molecules with adaptors, without the requirement of PCR which will eliminate modifications, for the characterization of nucleotide sequences in their native forms. Such preserved modifications will deviate nanopore sequencing signals from their canonical counterparts therefore introducing basecalling artifacts. For instance, precisely basecalling modification-rich tRNAs has long been a challenge. According to a most recent study in yeast, basecalling artifacts were frequently-found near modification hotspots, thereby introducing excessive alignment mismatches, deletions and insertions as opposed to the reference genome9. Such a compromised basecaller thus hinder the rigorous investigation of nucleotide sequences using nanopore sequencing.

More recently, nanopore sequencing has been used for quality control10 and optimizing11 therapeutic RNAs. For example, mRNA vaccines produced through in vitro transcription are usually densely-modified (e.g. ubiquitously substituting uridines with pseudouridines or N1-methylpseudouridines), to reduce innate immune responses and promote stability and efficacy12. Such dense modifications might strongly compromise basecalling, further biasing the quantification of mRNA vaccine purity and integrity. As reported by the latest quality control study, modification-disturbed basecalling resulted in the overestimation of truncated (therefore low-quality) vaccine mRNAs, compared to the ground-truth capillary electrophoresis result10. Consequently, the validity of nanopore sequencing as a generic method to characterize therapeutic RNA was significantly undermined.

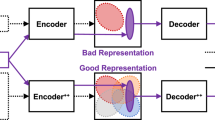

To address such bioinformatic challenges, we present an iterative workflow to polish the nanopore sequencing basecalling for native reads. This iterative basecalling method builds upon the hypothesis that initial analyses with, e.g. Guppy, Bonito and Dorado produce acceptable basecalling accuracy. Iterative basecalling next polishes such yielded sketch sequences by aligning them to ground-truth references. Such polished sequences, paired with their raw nanopore sequencing signals, will be used to train the updated basecallers. Such a process iterates until basecalling accuracy converges, as shown in Fig. 1A.

A Workflow overview. Sequence++ represents sequences corrected with the reference. Basecaller++ represents the basecaller updated using Sequence++. B Mappability and alignment accuracy of RNA control oligos, in which counterparting canonical nucleotides were substituted using N1-methyladenosine (m1A), N6-methyladenosine (m6A) or 5-methylcytosine (m5C) respectively. Distributions of alignment accuracy were shown with ecdf (empirical cumulative distribution function). Guppy, results produced by the Guppy basecaller; Round1-4, results produced by each iteration. C RNA control oligo alignments from Guppy and iterative basecalling Round4 were visualized with IGV. Without losing generality, reads aligned to the reference contig “5mers_1_curlcake_1” were shown. D Alignment position comparison between Guppy and iterative basecalling Round4 results. Train, results for train datasets used in (B, C); Test, results for test datasets that are independent of “Train”. Arrows represent alignment directions. E Mappability and alignment accuracy comparison between train and test datasets.

Results

Iterative basecalling for accurately decoding nucleotide sequence backbones

We benchmarked iterative basecalling with RNA control oligos8. Among these oligos, all the counterparting canonical nucleotides were substituted with N1-methyladenosine (m1A), N6-methyladenosine (m6A) or 5-methylcytosine (m5C). We first basecalled and aligned these oligos using Guppy, and found compromised mappability (the percentage of reads that could be aligned) and alignment accuracy. We next performed iterative basecalling, and considered basecalling performance (see METHODS) convergence as the stopping criterion. As shown in Figs. 1B and S1, we noticed significant basecalling improvements in the first two iterations and marginal improvements from subsequent iterations, which further suggested two iterations are sufficient enough for most use-cases. Nevertheless, we left the number of iterations as a user-defined parameter, for maximizing the flexibility of our iterative workflow. We then confirmed the improvement of mappability and clearance of basecalling artifacts through iterative basecalling with IGV (Fig. 1C). Importantly, we noticed that for the m1A oligos, Guppy generally failed to analyze shorter sequencing reads. Iterative basecalling, on the other hand, recovered such reads therefore can more precisely determine the read-length distribution, which is a critical quality metric for RNA molecules.

We also confirm that our iterative approach will polish, rather than deviating basecalling. We ran end-product basecallers that were trained in Fig. 1B and Guppy on both train and independent test datasets. By comparing yielded sequences, we noticed consistent alignment positions (Fig. 1D). Such results confirm that iterative basecalling produces the same sequence scaffolds, with higher per-nucleotide accuracy, compared to Guppy. We further confirmed that iterative basecalling will decode actual nucleotide sequences, rather than overfitting sketch sequences initially basecalled using Guppy. By comparing mappability and alignment accuracy between train and test datasets, we only observed negligible differences (Fig. 1E). We also analyzed an independent sequencing batch as reported by Begik et al.5, and observed consistent basecalling improvements (Fig, S2, see METHODS).

rRNA and tRNA sequence analysis

We applied iterative basecalling to analyze RNAs in real-world biological scenarios. As a proof-of-concept, we first analyzed 18S and 25S yeast rRNA nanopore sequencing data which was previously published13. Specifically, such a dataset surveyed rRNAs (1) purified from mutant strains (CBF5_GLU and NOP58_GLU) which have distinct modification patterns; (2) produced using in vitro transcription (IVT) which contain no modification. We iteratively trained then benchmarked a basecaller for yeast rRNAs (Fig. S3A–C, see METHODS), further applying it on the independent test dataset. Iterative basecalling could still improve mappability, even though great performance has already been made by Guppy. Meanwhile, iterative basecalling can significantly remove basecalling errors, thus increasing alignment accuracy. In addition, we observed similar mappability and alignment accuracy between train and test datasets, which suggested a negligible overfitting when training the iterative basecaller. Noticeably, we observed that the basecalling of IVT rRNAs, which contain no modification, could also be optimized by iterative basecalling (Fig. 2A, B, see METHODS). Such an observation suggested that the “vanilla” Guppy (in this case version 6.0.6+8a98bbc paired with generic basecalling model template_r9.4.1_450bps_hac) might be suboptimal to analyze certain RNA species, which could be accurately analyzed using iterative basecalling instead.

A Mappability and alignment accuracy of yeast rRNAs. CBF5_GLU and NOP58_GLU, mutant strain rRNAs which have different RNA modification patterns; IVT, rRNAs made by in vitro transcription which contain no modification. Train, polished basecalling results for datasets used during iterative basecaller training; Test, polished basecalling results for independent test datasets; Guppy, initial Guppy basecalling results for test datasets. B IGV visualization for initial Guppy and polished basecalling results. C Mappability and alignment accuracy of native yeast tRNAs. Train, polished basecalling results for datasets used during iterative basecaller training; Test, polished basecalling results for independent test datasets; Guppy, initial Guppy basecalling results for test datasets. D IGV visualization for initial Guppy and polished basecalling results. Yeast tRNA species Gln-CTG and Gly-GCC were chosen for visualization, as examples for all-canonical and modification-containing transcripts, respectively.

We also analyzed previously published nano-tRNAseq profiles, which surveyed 42 yeast tRNA species, each having unique modification patterns ranging from densely-modified to all-canonical9. We trained then benchmarked the iterative basecaller (Fig. S3D, E, see METHODS), further applied it on an independent biological replicate test dataset. As shown in Fig. 2C, D, similar to yeast rRNA analyses, we noticed remarkably improved basecalling over Guppy, consistent performance between train and test reads, as well as optimized basecalling of all-canonical molecules such as tRNA Gln-CTG (see METHODS). Taken together, we proved the precise sequence interpretation of biological RNA molecules by the iterative basecalling workflow.

mRNA vaccine purity and integrity analysis

Building upon the benchmarked efficacy and reliability of iterative basecalling, we next leveraged such a workflow to quantify the purity and integrity of vaccine mRNAs. As a proof-of-concept, we revisited datasets and conclusions from the VAX-seq study10. Vaccine mRNAs are generally produced with the plasmid-based in vitro transcription system. To quantify the purity and integrity of mRNA vaccine products, VAX-seq exploited sequencing and bioinformatic approaches. Without losing generality, the performance of VAX-seq was evaluated using eGFP as the “mock vaccine mRNA”. In particular, VAX-seq performed native RNA nanopore sequencing on all-canonical and U-to-N1-methylpseudouridines fully-replaced mRNA vaccines, and concluded that modifications yielded a significantly higher fraction of truncated transcripts. Contradictorily, VAX-seq reported only a minor transcript length difference between all-canonical and fully-replaced mRNAs by capillary electrophoresis. To scrutinize such a discrepancy, we performed iterative basecalling (Fig. S4, see METHODS), and observed significant and consistent basecalling improvements on both train and test datasets (Fig. 3A, B, see METHODS). We then determined the alignment status breakdown for test reads, and noticed no reverse, as well as negligible non-primary and supplementary alignments (Fig. 3C). We further surveyed alignment positions, and noticed no off-target (overlapping with the plasmid backbone), and >80% full-length (spanning the entire eGFP coding sequence) transcripts, in both all-canonical and fully-replaced samples (Fig. 3D). Altogether, such results demonstrated the purity and integrity of N1-methylpseudouridylated mRNA vaccines produced with the plasmid-based in vitro transcription system.

A Mappability and alignment accuracy of vaccine mRNAs. U.M., canonical mRNA; m1Psi, U-to-N1-methylpseudouridines fully-replaced mRNA. Train, polished basecalling results for datasets used during iterative basecaller training; Test, polished basecalling results for independent test datasets; Guppy, initial Guppy basecalling results for test datasets. B IGV visualization of initial Guppy and polished basecalling results. For the alignment track, the “downsample reads” option was enabled for the visualization purpose. C The SAM file flag breakdowns, which encode alignment status for test reads. D Per-read alignments for test reads.

BioRNA modification hotspot inspection

Precisely resolved sequence backbones by the iterative basecalling enhance the rigorous determination of nucleotide modifications. As a real-world preclinical usecase, we inspected modification hotspots within BioRNAs. BioRNAs are engineered from human tRNAs, and are molecular carriers for therapeutic RNA interference (RNAi) agents. In particular, the candidate RNAi agent is incorporated in the BioRNA anti-codon loop for the stable large-scale production, and released by the endogenous microRNA processing pathway after the cellular absorption14. Our previous effort suggested the indispensability of modification hotspots for the BioRNA folding and metabolic stability15,16. Therefore, we controlled the BioRNA quality from the modification perspective. We prioritized two widely-used BioRNA carriers (BioRNASer and BioRNALeu) in our analysis. In these carriers, we used the Sephadex aptamer as the placeholder for therapeutic RNAi molecules. In addition, we synthesized and sequenced their canonical counterparts (ChemoRNASer and ChemoRNALeu) as control samples (see METHODS). The schematic of Bio/ChemoRNA structures and modifications are shown in Fig. 4A. We performed nanopore native RNA sequencing on these BioRNA and ChemoRNA molecules (see METHODS).

A Structures and modification patterns of Bio and ChemoRNA. B Mappability and alignment accuracy of BioRNAs (containing modifications) and ChemoRNAs (no modification). Train, polished basecalling results for datasets used during iterative basecaller training; Test, polished basecalling results for independent test datasets; Bonito, initial Bonito basecalling results for test datasets. C IGV visualization of initial Bonito and polished basecalling results. For the alignment track, the “downsample reads” option was enabled for the visualization purpose. D The sequencing signal comparison between BioRNAs and corresponding ChemoRNAs. Signals mapped to the same nucleotide position were summarized using a probability density distribution (upper panel). Distribution differences between Bio and ChemoRNAs were quantified by KS-test D-values (lower panel): larger D-values indicate higher modification likelihood.

For each Bio/ChemoRNA category, we iteratively trained and benchmarked a basecaller (Fig. S5, see METHODS), further applying it on the independent test dataset. We found that iterative basecalling could generate significant and consistent basecalling improvements, even in unmodified ChemoRNAs, on both train and test datasets (Fig. 4B, C, see METHODS). Based on these precisely determined sequence backbones, we inspected BioRNA modification hotspots. Specifically, we calculated the signal mean distribution for every nucleotide using Remora, then quantified the distribution difference between BioRNA and ChemoRNA using the KS-test D-value (see METHODS). A higher D-value represents a stronger BioRNA signal deviation, which suggests the presence of modification. As shown in Fig. 4D, we discovered potential modification hotspots near Positions 19, 71 and 98, for both BioRNASer and BioRNALeu. These modification hotspots are located in D, anti-codon and T-arms respectively, and are conserved across different human tRNA species. The preservation of these modification hotspots, particularly those in the D and T loops that are also conserved in natural human tRNAs, may suggest proper folding and metabolic stability17 of our BioRNAs. Meanwhile, we detected another hotspot (Position 8) in the acceptor-stem. Such a discovery contradicts our prior knowledge that the Position 8 is unmodified in human tRNAs. Considering BioRNAs are produced using E.coli, and the E.coli tRNA U8 (U at Position 8) is in general converted into 4-thiouridine (s4U) through enzymatic reactions18, we explained this hotspot as an E.coli-specific s4U modification. For this hotspot, further characterizations on its biochemical and molecular properties, as well as investigations into its influence on the BioRNA therapeutic efficacy are planned as our future efforts.

Discussion

In nanopore sequencing, precisely resolving sequence backbones from electric signals, known as basecalling, is the prerequisite for virtually all the downstream bioinformatic analyses. For instance, we have demonstrated that precise basecalling can significantly facilitate pinpointing nucleotide modifications at the single-nucleotide resolution, thereby establishing a general two-step modification detection paradigm8. To accomplish precise basecalling, in this paper, we report a reference-guided iterative bioinformatic workflow. Specifically, our approach polishes basecalling results, based on the a priori knowledge about the ground-truth reference sequence. Our approach is thus uniquely suitable for training biomolecule-specific high-accuracy basecallers. For instance, we confirmed the superior performance in basecalling control oligos, as well as native rRNAs and tRNAs using our approach. Building upon such benchmarked basecalling performance, we leveraged our approach for the quality control of therapeutic molecules. Specifically, we basecalled the VAX-seq data as the basis for quantifying the mRNA vaccine purity and integrity, as well as the BioRNA data as the basis for inspecting modification hotspots in RNAi drugs. We finally confirmed the generalizability of the iterative approach across various basecalling frameworks released by Oxford Nanopore Technologies, including Guppy (Figs. 1B–D, 2 and 3) which was developed for the earlier R9.4.1 flowcell chemistry, as well as Bonito (Fig. 4) and Dorado (Fig. S6, see METHODS) which are compatible with the latest RNA flowcell chemistry.

The success of our iterative approach depends on the performance of initial basecalling. As a result, “non-basecallable” nanopore sequencing signals, such as those significantly deviated by modifications, are unlikely to be properly handled, as one major limitation of our approach. We therefore expect the development of generic basecallers, in particular ones that are tolerant to various categories of modifications as described in our previous research19, to be one potential solution.

During the iterative basecalling process, sequence backbones will be polished based on the reference sequence. Thus, sequence discrepancies between the provided reference and real-world biomolecules could introduce systematic basecalling artifacts, as another limitation of our approach. For instance, single nucleotide polymorphism sites, which are generally not recorded in the reference, cannot be properly handled by our approach. To maximize the performance of iterative basecalling, the quality of reference sequence, as well as the sequence homogeneity of candidate biomolecules, need to be guaranteed. To examine the reference-candidate sequence discrepancies, further controlling for their resulting systematic artifacts during the iterative basecalling, we recommend to perform companion cDNA sequencing experiments.

While this paper primarily focuses on the polishing of modification-disturbed basecalling, our iterative approach could also promote the interpretation of canonical sequences. For example, basecalling accuracy of unmodified RNAs, such as rRNAs produced from IVT, tRNA species Gln-CTG and chemically-synthesized ChemoRNAs, was largely improved by iterative basecalling (Figs. 2 and 4). Therefore, we highlight the iterative basecalling as a general approach for polishing sequence backbones.

Methods

The production and purification of BioRNAs

The design and production of bioengineered human seryl-tRNA (TGA) and leucyl-tRNA (TAA) (BioRNASer and BioRNALeu) have been described in our previous studies20,21. In brief, human tRNA sequences were obtained from GtRNAdb (https://gtrnadb.ucsc.edu/) and anti-codon regions were replaced by a Sephadex aptamer to establish recombinant human tRNA constructs. Target tRNA coding sequences (Table S1) were amplified with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with specific primers. RNA expression plasmids were then constructed by infusing amplicons into a pBSTNAV vector with the In-Fusion® HD Cloning kit (Takara). After verification with DNA sequencing, plasmids were transformed to E. coli HST08 competent cells to express and accumulate BioRNASer and BioRNALeu through overnight fermentation on a large scale (~500 mL). The total RNA was isolated from the overnight culture using the phenol extraction method, and subsequently loaded and separated on the ENrich-Q 10 × 100 anion exchange column (Bio-Rad) integrated in the NGC Quest 10 Plus chromatography system (Bio-Rad) for purifying target BioRNAs. The total RNA was eluted using the gradient method, which consist of buffer A (10 mM monosodium phosphate, pH 7.0) and buffer B (buffer A + 1 M sodium chloride, pH 7.0) at a constant flow rate of 2 mL/min. To purify BioRNAs, the column was first equilibrated with buffer A for 6.7 min, followed by elution with 55% buffer B for 4.8 min, then 55–70% buffer B for 40 min (for BioRNASer), or 55–75% buffer B for 30 min (for BioRNALeu). The column was subsequently washed using 100% buffer B for 10 min, with an additional re-equilibration using buffer A for 10 min. Fractions of target RNA peaks were collected during the total RNA elution, and then loaded onto urea PAGE gels to verify size and homogeneity. Pure fractions were combined, desalted and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-2mL centrifugal filters (30 k; MilliporeSigma) to obtain ready-to-use pure BioRNAs. The BioRNA purity was determined by the urea PAGE analysis, and quantified using the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously reported16,21. BioRNA products with high homogeneity (>98%) were used in the nanopore sequencing study.

ChemoRNAs and Nano-tRNAseq adaptors

The chemically synthesized, Sephadex aptamer-tagged human seryl-tRNA (TGA) and leucyl-tRNA (TAA) (ChemoRNASer and ChemoRNALeu), and Nano-tRNAseq9 adapters were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies. Specifically, for nano-tRNAseq 5’ RNA splint adapters, the first four nucleotides at the 3’ terminal were designed as rUrGrGrC and rUrGrGrU, which are complementary to seryl-tRNA and leucyl-tRNA, respectively. Other Nano-tRNAseq adapters, including 3’ RNA:DNA splint adapters and ONT reverse transcription adapters (RTAs, oligo A and oligo B) were synthesized as reported in the original study. Sequences of ChemoRNAs and adapters were listed in Table S1.

The nanopore sequencing of BioRNAs and ChemoRNAs

BioRNA and ChemoRNA nanopore sequencing libraries were constructed first following the nano-tRNAseq protocol9, then using the Direct RNA Sequencing Kit (SQK-RNA004, Oxford Nanopore Technologies) following manufacturer’s instructions. Specifically:

Adapter annealing

5’ RNA splint adapters and equal moles (~108 pmol) of 3’ RNA:DNA splint adapters were mixed with a dilution buffer consisting of Tris-HCl (10 mM, pH 7.5), NaCl (500 mM), and 1 μL of RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor (N2511, Promega) to a final concentration of ~50 ng/μL for each adapter in a total volume of 20 μL. The mixture was incubated at 75 °C for 15 s, further cooled to 25 °C at a rate of 0.1 °C/s (a total of 500 s) to anneal splint adapters. RTA oligo As and oligo Bs (~82 pmol for each, ~200 ng in total) were annealed under the same condition as splint adapters.

Ligation 1

1 μg of target RNA (ChemoRNASer, ChemoRNALeu, BioRNASer or BioRNALeu) was ligated to pre-annealed splint adapters (RNA:adapters = 1.2:1, molar ratio) in a 20 μL reaction system containing T4 RNA ligase 2 (10U, M0239S, Promega), 1 × Reaction Buffer (B0216S, NEB), 10% PEG 8000 (B0216S), 400 μM ATP (B0216S), and 1 µL RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor. The reaction was conducted at room temperature for 1 h. Ligation products were purified with 1.8x volume of well-mixed, room temperature AMPure RNAClean XP beads (A63987, Beckman Coulter) following manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrations of purified samples were determined using the Tecan plate reader (Tecan), and the quality of ligated RNAs was evaluated by urea polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) analyses.

Ligation 2 and reverse transcription (RT)

Purified “Ligation 1” products (400 ng, ~10.4 pmol, for two sequencing replicates) were further ligated to pre-annealed RTA adapters (RNA:adapters = 1:2, molar ratio) with the T4 DNA Ligase (M0202M, NEB) in a 30 μL reaction buffer constituted by 6 μL of NEBNext Quick Ligation Reaction Buffer (B6058S, NEB), 1 μL of RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor and RNase-free water by incubating at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, the ligation product was mixed with 4 μL of dNTPs (10 mM, N0447S, NEB) and 26 μL of RNase-free water to pre-denature the RNA at 65 °C for 5 min and then cooled down on ice for 2 min. A mixture of Maxima H Minus Reverse Transcriptase (4 μL, EP0751, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 16 μL of Maxima H Minus Reverse Transcriptase Buffer, and 2 μL of RNasin Ribonuclease Inhibitor (80U) were added to the pre-treated RNA sample to perform RT by incubation at 60 °C for 1 h, 85 °C for 5 min, then cooling to 4 °C. AMPure RNAClean XP beads were then added to purify the RT products according to the protocol. The quantity and quality of the purified samples were determined by the Tecan plate reader and the urea PAGE gel, respectively.

Ligation 3 and final library

Following purification, 40 μL (two replicates) of RT products were ligated to 12 μL of RNA Ligation Adapter (RLA, provided by the SQK-RNA004 kit) in an 80 μL reaction system, supplemented with 16 μL of NEBNext Quick Ligation Reaction Buffer and 6 μL of T4 DNA Ligase for a 30-min incubation at room temperature. The ligation products were purified using AMPure RNAClean XP beads following the protocol provided by the SQK-RNA004 kit. Afterwards, MinION flow cells (RNA chemistry) were primed following manufacturer’s instructions. Meanwhile, Elution Buffer (provided by the SQK-RNA004 kit) re-suspended libraries were gently mixed with 37.5 μL of Sequencing Buffer (provided by the SQK-RNA004 kit) and 25.5 μL of Library Solution (provided by the SQK-RNA004 kit) to obtain final libraries. A total volume of 75 μL final library was loaded to each flow cell for sequencing.

The step-by-step validation of RNA purity and quality throughout the library preparation process was presented in Figure S7.

Iterative basecalling with the Guppy-Taiyaki workflow

The Guppy-Taiyaki workflow is used to analyze nanopore sequencing data produced by the earlier R9.4.1 flowcell chemistry.

RNA control oligos, yeast rRNAs and tRNAs, as well as vaccine mRNAs were iteratively basecalled with the Guppy-Taiyaki workflow. The workflow consists of (1) Guppy (version 6.0.6+8a98bbc) for basecalling and alignment; (2) Samtools (version 1.16) for alignment result processing including merge, sort and index22; (3) Taiyaki (version 5.3.0) for training Guppy model, including 3.1) data preparation by scripts generate_per_read_params.py, get_refs_from_sam.py, prepare_mapped_reads.py and merge_mappedsignalfiles.py; 3.2) model training by scripts train_flipflop.py and dump_json.py; (4) iterating the above steps with the trained model. Specifically, Poly(A) tails and adapter signals will be trimmed during the basecalling process, following the default setup of the Guppy-Taiyaki workflow. The workflow is summarized in Fig. S8.

For Step 1, the initial basecalling used Guppy model “template_rna_r9.4.1_70bps_hac.jsn”, together with the “--disable_qscore_filtering” flag to keep as many reads as possible for downstream analyses. All other flags were set default. Subsequent iterations used the trained model with the “--disable_qscore_filtering” flag, and other flags were set default. In particular, a stand-alone Minimap223 (version 2.24-r1122) was used to optimize tRNA alignments, with “-ax map-ont -k5 -w5” flags as recommended in the original study9.

For Step 2, default flags for Samtools merge, sort and index were used for all analyses.

For Step 3, The “--reverse” flag was used for get_refs_from_sam.py, with other flags set default. Flags for generate_per_read_params.py and merge_mappedsignalfiles.py were set default. The initial iteration used the model checkpoint “r941_rna_minion.checkpoint” that is provided by Taiyaki, to run the prepare_mapped_reads.py (a customized version: https://github.com/wangziyuan66/IL-AD/blob/main/scripts/trna/train_flipflop.py was used for the tRNA analysis); the model checkpoint trained in the previous iteration was used for subsequent iterations. All other flags were set default during this process.

As for model training, the model template “mLstm_flipflop.py” that is provided by Taiyaki, and flags “--size 256 --stride 10 --winlen 31”, were used for train_flipflop.py. Other flags were set default. Default flags for dump_json.py were used for generating final models.

Iterative basecalling with the Bonito workflow

The Bonito workflow is used to analyze nanopore sequencing data produced by the latest R10.4.1 (for DNA sequencing) and RNA (for RNA sequencing) flowcell chemistry.

BioRNAs and ChemoRNAs were iteratively basecalled with the Bonito (version 0.8.1) workflow, including (1) the “bonito baseball” option for basecalling, alignment and training data preparation; (2) the “bonito train” option for model training; (3) iterating Step 1 and 2 with the trained model. Specifically, Poly(A) tails and adapter signals will be trimmed during the basecalling process, following the default setup of the Bonito workflow. The workflow is summarized in Fig. S9.

For Step 1, the initial basecalling used Bonito model “rna004_130bps_hac@v3.0” with “--chunksize 3000 --save-ctc --min-accuracy-save-ctc 0.9” flags to prepare high-quality training data. All other flags were set default. Subsequent iterations used the trained model with flags “--chunksize 3000 –save-ctc --min-accuracy-save-ctc 0.9”, and other flags were set default.

For Step 2, the initial model training fine-tunes the model “rna004_130bps_hac@v3.0”. Subsequent iterations fine-tune the model produced from the previous iteration. Flags “--size 256 --epochs 5 --lr 5r-4” (other flags were set default) during the training process.

Iterative basecalling with the Dorado workflow

BioRNAs and ChemoRNAs were also analyzed with Dorado-based iterative basecalling workflow. Dorado shares the same model architecture with Bonito. Thus, we converted Bonito models trained in each iteration as the corresponding Dorado models, using the “bonito export” option. The Dorado version 0.8.1 was used throughout the analysis.

Basecalling performance evaluation

Basecalling performance was “functionally” evaluated by downstream alignment results, including mappability (the ratio between aligned reads, regardless of SAM flags, and all reads), alignment accuracy (the “alignment_accuracy” entry in the basecalling summary file, calculated as the ratio between correctly aligned bases “alignment_num_correct” and the sum of correctly aligned bases and mismatches “alignment_num_aligned”, insertions “alignment_num_insertions” and deletion “alignment_num_deletions”), alignment consistency (alignment start and end positions) as opposed to results produced by “vanilla” Guppy, Bonito or Dorado, and IGV visualization (version 2.17.4).

Nanopore sequencing signal analysis

We first basecalled nanopore sequencing reads using Bonito (version 0.8.1) to produce move-tables, which track signal chunks corresponding to individual nucleotides (stored as mv tags in the generated bam files). We next executed the Remora (version 3.2.0) pipeline “Reference Region Metric Extraction” (https://github.com/nanoporetech/remora/blob/master/notebooks/metrics_api.ipynb) to extract the per-nucleotide signal mean values. Throughout the analysis, all the Bonito parameters were set as default. The “reverse_signal” flag for Remora was set as True, and all the other Remora parameters were set as default.

Statistics and reproducibility

For training the iterative basecalling models, the design of training and test datasets, including the number of reads, whether training and test reads were collected in the same flowcell and the same biological batch, were summarized in Table S2. The computational costs were summarized in Table S3.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The BioRNA nanopore sequencing data was deposited at NCBI under the BioProject PRJNA1155679. The RNA oligo nanopore sequencing data was downloaded from NCBI under the BioProject PRJNA1050579 (runs SRR27324841, SRR27324838 and SRR27324839). Corresponding reference sequences were downloaded from the Table S2 of8. The yeast native rRNA nanopore sequencing data was downloaded from ENA under accession number PRJEB48183 (samples ERR7162388, ERR7162390 and ERR7162391). Corresponding reference sequences were downloaded from https://github.com/adbailey4/yeast_rrna_modification_detection/tree/main/notebooks/data. The yeast native tRNA nanopore sequencing data was downloaded from ENA under accession number PRJEB55684 (samples ERR10224971 and ERR10224975). Corresponding reference sequences and modification annotations were downloaded from https://github.com/novoalab/Nano-tRNAseq/tree/main/ref. The mRNA vaccine nanopore sequencing data was downloaded from NCBI under the BioProject PRJNA856796 (runs SRR22888949 and SRR22888950). The corresponding reference sequence was downloaded from https://github.com/scchess/Mana/tree/main/data. The basecalling sequencing summary files were uploaded to Figshare: https://figshare.com/s/f39c893a85928aefd10c, (https://doi.org/10.25422/azu.data.29429399.v1) and the associated metadata is provided in Table S4.

Code availability

The Taiyaki iterative basecalling framework can be found at: https://github.com/wangziyuan66/iterative-labeling-toolkit-taiyaki (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16905223). The Bonito iterative basecalling framework can be found at: https://github.com/wangziyuan66/iterative-labeling-toolkit-bonito (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16905231).

References

Pagès-Gallego, M. & de Ridder, J. Comprehensive benchmark and architectural analysis of deep learning models for nanopore sequencing basecalling. Genome Biol. 24, 71 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Accurate detection of m6A RNA modifications in native RNA sequences. Nat. Commun. 10, 4079 (2019).

Parker, M. T. et al. Nanopore direct RNA sequencing maps the complexity of Arabidopsis mRNA processing and m6A modification. Elife 9, e49658 (2020).

Price, A. M. et al. Direct RNA sequencing reveals m6A modifications on adenovirus RNA are necessary for efficient splicing. Nat. Commun. 11, 6016 (2020).

Begik, O. et al. Quantitative profiling of pseudouridylation dynamics in native RNAs with nanopore sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1278–1291 (2021).

Jenjaroenpun, P. et al. Decoding the epitranscriptional landscape from native RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, e7–e7 (2021).

Nguyen, T. A. et al. Direct identification of A-to-I editing sites with nanopore native RNA sequencing. Nat. Methods 19, 833–844 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Adapting nanopore sequencing basecalling models for modification detection via incremental learning and anomaly detection. Nat. Commun. 15, 7148 (2024).

Lucas, M. C. et al. Quantitative analysis of tRNA abundance and modifications by nanopore RNA sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 72–86 (2024).

Gunter, H. M. et al. mRNA vaccine quality analysis using RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 14, 5663 (2023).

Zeglinski, K. et al. An optimized protocol for quality control of gene therapy vectors using nanopore direct RNA sequencing. Genome Res. 34, 1966–1975 (2024).

Sahin, U., Karikó, K. & Türeci, Ö mRNA-based therapeutics—developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 759–780 (2014).

Bailey, A. D. et al. Concerted modification of nucleotides at functional centers of the ribosome revealed by single-molecule RNA modification profiling. Elife 11, e76562 (2022).

Traber, G. M. & Yu, A.-M. RNAi-based therapeutics and novel RNA bioengineering technologies. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 384, 133–154 (2023).

Li, M.-M. et al. Chimeric microRNA-1291 biosynthesized efficiently in Escherichia coli is effective to reduce target gene expression in human carcinoma cells and improve chemosensitivity. Drug Metab. Disposition 43, 1129–1136 (2015).

Wang, W.-P. et al. Bioengineering novel chimeric microRNA-34a for prodrug cancer therapy: high-yield expression and purification, and structural and functional characterization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeutics 354, 131–141 (2015).

Suzuki, T. The expanding world of tRNA modifications and their disease relevance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 375–392 (2021).

Lauhon, C. T., Erwin, W. M. & Ton, G. N. Substrate specificity for 4-thiouridine modification in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23022–23029 (2004).

Wang, Z. et al. Training data diversity enhances the basecalling of novel RNA modification-induced nanopore sequencing readouts. Nat. Commun. 16, 679 (2025).

Li, P.-C. et al. In vivo fermentation production of humanized noncoding RNAs carrying payload miRNAs for targeted anticancer therapy. Theranostics 11, 4858 (2021).

Tu, M.-J. et al. Expression and purification of tRNA/pre-miRNA-based recombinant noncoding RNAs. in RNA Scaffolds: Methods and Protocols (Springer, 2021).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Xinlei Sheng for his valuable discussions. We thank the University of Arizona High Performance Computing team and the College of Pharmacy Information Technology Group for their support. H.D. is supported by the University of Arizona Health Sciences Career Development Award, and the University of Arizona Accelerate For Success Award. A.-M.Y. is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences [R35GM140835] and National Cancer Institute [R01CA225958 and R01CA253230], National Institutes of Health (NIH). J.Q. is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [R01HL159675 and R01HL152293], National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [R21AI163753] and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [R01DK132251], National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.D. and A.-M.Y. conceived the idea. Z.W., Z.L., and H.D. performed the analysis. M.-J.T., K.K.W., and Y.F. performed the experiment. N.H., H.H.Z., X.S., J.Q., A.-M.Y., and H.D. supervised the project. Z.W., M.-J.T., A.-M.Y., and H.D. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.D. has a patent application related to this work (Hongxu Ding, An Iterative Approach to Polish the Nanopore Sequencing Basecalling for Therapeutic RNA Quality Control, US Provisional Patent Application No. 63/693,352). Z.W. has received travel expenses from Oxford Nanopore Technologies to speak at the 2025 RNA annual meeting. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Aylin Bircan, Laura Rodriguez Perez.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Tu, MJ., Liu, Z. et al. A reference-guided iterative approach to polish the nanopore sequencing basecalling for therapeutic RNA quality control. Commun Biol 8, 1406 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08811-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08811-4