Abstract

We investigate how sensory and motor components of the visual system respond to carrier (first-order) and envelope (second-order) motion features for global motion perception. While both ocular following responses (OFRs) and perceptual judgments exhibit higher responsivity to envelope motion, carrier motion alone was insufficient, leading to large perceptual direction errors and speed biases and minimal OFRs. Shorter presentation times selectively impaired perceptual speed discriminability by decreasing the signal and increasing noise, with no corresponding effect on oculomotor responses. In direction discriminability analysis, in contrast, OFRs and perceptual responses have a similar relative noise pattern to motion features, suggesting shared noise sources in global motion processing. Trial-by-trial correlation analysis confirmed the dissociation where perceptual speed was uncorrelated with OFR speed, whereas perceptual direction showed a delayed correlation with eye direction relative to movement onset. This delayed correlation timing for direction suggests global motion modulates both systems via feedback control processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In viewing dynamic visual scenes, the visual system can engage in motion perception, smooth eye movements, or an integrated combination of both, relying on sensory motion signals mainly processed in the middle temporal (MT) area1,2,3,4,5. It is well-established not only that area MT plays a pivotal role in encoding motion signals for both perception and eye movements, but also that these two systems exhibit divergent processing mechanisms depending on cognitive demands such as attention, expectation, and motor planning1,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

The neural processing of visual motion differs substantially between first-order (e.g., luminance-defined) and second-order (e.g., contrast-defined) types, with significant consequences for both smooth pursuit eye movements and perception. In area MT, for instance, first-order motion stimuli elicit stronger neural responses than second-order stimuli17,18,19. This neural distinction manifests in pursuit initiation: first-order motion drives higher initial eye acceleration, whereas second-order motion results in longer initiation latencies20,21,22. A different aspect of this dissociation is seen in perception, where spatial summation impairs the perception of first-order, but not second-order, motion as a function of increased stimulus size23. Further findings suggest that the first-order and second-order motion systems contribute differently to smooth pursuit eye movements; the precision of low-level speed estimation (measured with first-order motion) predicts pre-saccadic acceleration, while the precision of high-level speed estimation (based on position-tracking via second-order motion) predicts post-saccadic pursuit accuracy24. These findings suggest that first-order and second-order motion may be processed by distinct mechanisms across both oculomotor and perceptual systems.

Although studies have often demonstrated a dissociation between perception and smooth eye movements, where the two systems show different sensitivities to the same stimulus, these investigations have typically relied on stimuli such as uniform motion fields (often used in ocular following studies) or single moving targets (such as a Gabor or random dot patch), rather than more complex scenes8,9,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. Consequently, it remains unclear how the processing of different motion features, such as first-order (carrier) and second-order (envelope) signals, might diverge for ocular following and perception during global motion perception. To examine sensory tuning of the ocular following system to motion features, we focused on the initiation period of ocular following responses (OFRs), an short-latency eye movement evoked by large-field motion33,34. Many studies have compared motion perception to voluntary smooth pursuit and the initiation of pursuit is known to be modulated by top-down cognitive factors such as attention and expectation6,12,14,35. We therefore used the closely related, involuntary OFR, which is also thought to rely on similar early motion processing pathways such as area MT32. Following the analytical approach common in smooth pursuit research, our analysis focused specifically on the initial period of the response, which can be assumed as open-loop period and considered a direct readout of sensory processing because it is driven by feedforward visual signals before visual feedbacks can modify the eye movement4,5. Crucially, trial-by-trial variations in smooth eye movements during this interval are often considered to be largely accounted for by errors in sensory estimation rather than noise in the motor system (though see Rasche & Gegenfurtner36, for a different view) making it a reliable proxy for the underlying sensory encoding computations2,4,5,37.

In this study, we employ a global motion perception task designed to probe how the oculomotor and perceptual systems differently solve the classic ‘aperture problem'38,39. The underlying principle of this problem is that the visual system should estimate a single global motion vector from ambiguous local motion signals38,40,41,42. Each individual motion-sensitive neuron, limited by its small receptive field, captures only a one-dimensional component of the true 2D motion, specifically, the component orthogonal to an object’s contour38,40,41,42 (Fig. 1).

Direction signals orthogonal to the preferred orientation (red arrows) are also consistent with a global speed and direction of motion (orange arrows). a Illustrates an example of a rigid object, b illustrates the present study, in which narrow band carrier stimuli are viewed through apertures, each of which can be moved independently or as a group. Note that this illustration is intended to depict a brief, instantaneous ( ~ 100 ms) phase of motion processing, and does not imply any orientation change in the carriers due to prolonged exposure. Orientation shifts resulting from long-duration motion were not part of the experimental design or analysis.

To this end, we designed a combined paradigm, with a simultaneous psychophysical matching task and OFR measurements to three classes of moving complex motion stimuli in three presentation timings (Fig. 2). Our three types of stimulus conditions deliver motion information through the movement of either or both of two features of an array of Gabor patches: carrier (first-order) and envelope (second-order)4,24,43. These motion sources are illustrated in the right panel of Fig. 1, where orange illustrates the motion of narrowband carriers and blue illustrates the motion of the Gaussian envelope,

-

1)

The Carrier+Envelope motion condition was generated by movements of the entire Gabor patches, therefore, the movement of the Gabor image array was rigid (both orange and blue motions in the right panel of Fig. 1.

-

2)

The Carrier motion with stationary envelope (drifting sine-wave) condition was generated by changing the phase of the sinewave carrier within a stationary Gaussian envelope. These drifting stimuli are often used for initiation of smooth pursuit eye movements as a step-ramp target4,12,44,45. This condition is illustrated by orange motion and stationary blue in the right panel of Fig. 1.

-

3)

The Envelope motion with stationary carrier (drifting Gaussian) condition was generated by drifting the envelope, while fixing the phase of the sinewave carriers stationary. This condition is illustrated by moving blue and stationary orange in the right panel of Fig. 1.

a The first frame of stimuli in all three conditions were identical and contained ≈ 83 randomly oriented Gabors presented within a 12.5° radius of an invisible circle. The position of the Gabors was random, subject to an exclusion area (2.1°) around each Gabor to prevent overlaps. Motion information was delivered through either motion of the carrier (within a static envelope), the envelope (over a static carrier) or both features. b Participants adjusted the speed and direction of a 1/F noise probe to match that of the estimated global motion of the Gabor motion array. The location of the mouse pointer relative to the center was used to determine the direction and speed of probe motion in real time. The probe stimulus was moved in the direction towards pointer location at a speed that increased linearly with the distance of the pointer from the center. The speed of the probe ranged from 0°/s at the inner annulus circle to a maximum speed of 37.5 °/s at the outer boundary circle. c Trial sequence. After fixation for 1250, 1500, or 1750 ms (at random across trials), one of three motion signal conditions were presented for 150, 300 or 500 ms (randomly interleaved across trials), followed by the matching phase. Eye movements were recorded at 1 KHz throughout the experiment.

The movement of the carrier in conditions 1 and 2 is comparable and would be expected to drive similar responses in direction selective cells in primary visual cortex46. The carrier motion in conditions 1 and 3 is not expected to generate a response from direction-selective first-order simple cells, without a non-linear stage, such as rectification47.

Here, we asked participants to respond to both speed and direction simultaneously unlike previous studies that measured speed and direction independently, and we simultaneously recorded OFRs. Since processing of speed and direction signals precedes accurate global motion estimation, their simultaneous measurement is especially important for addressing the aperture problem in this context. To anticipate the results, data on response speed and direction error reveal that both systems are overall more sensitive to envelope motion. Specifically, envelope motion drove higher initial eye speeds and resulted in lower direction errors in both ocular following and perceptual reports. The contribution of carrier motion, by contrast, was highly specific: it selectively influenced perceptual speed, and while it generated only negligible ocular following and impaired direction accuracy on its own, it synergistically boosted ocular following speed and enhanced direction accuracy in combination with the envelope signal. Furthermore, our discriminability analysis suggests that while perceptual speed was impaired by both signal and noise at short presentation times, direction information is shared between the perceptual and oculomotor systems, albeit with different levels of internal noise. Crucially, a trial-by-trial correlation analysis showed that this shared direction signal emerged with a significant delay relative to eye movement onset, suggesting that global motion processing is modulated by a shared feedback mechanism.

Results

Significant contributions of both envelope motion and carrier motion in perceiving speed

We first examined the perceived speed from the psychophysical matching task. Fig. 3a shows the mean match speed, averaged across observers (left) and individual data for the 12.5 ˚/s speed condition for (a) Carrier+Envelope (orange), (b) Carrier only (red) and c) Envelope only (olive green) conditions (see Supplementary Fig. 1a for 7.5 ˚/s speed condition). The overall speed estimations made by the 1/F noise motion probe were higher than global motion speed, and this is likely because motion stimuli with broad bandwidths appear slower26.

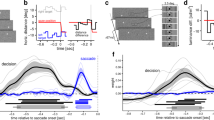

a Individual Absolute perceived speed estimates for 150 ms, 300 ms and 600 ms. Capped error bars to the left of each time condition represent the mean ± 1 SEM. Clustered bar charts consist of three pairs of colored bars, each showing estimated speeds for three local motion conditions. Each gray dot represents an individual’s mean estimated speed, and the error bars indicate ± 1 SD. The three bar pairs are arranged in ascending order of the grand mean of estimated speed, maintaining that the participant order is consistent across all time conditions. The color saturation represents the three presentation durations: 150 ms (full); 300 ms (medium) and 600 ms (light). b Example eye speed traces for Carrier + Envelope, Carrier motion, Envelope motion conditions for 600 ms duration. c Ocular following response speed for each motion condition for 150 ms and 600 ms presentation durations. Data for the 7.5 ˚/s conditions are in the same format in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Fig. 1, for clarity. The shaded area indicate mean ± SEM. d Discriminability of speed between Carrier+Envelope and Carrier condition in 150 ms, 300 ms, and 600 ms duration. Percent correct is calculated by linear discriminant analysis. Color saturation indicates the three presentation durations. The error bars with the shaded area indicate mean ± SEM. Data for the 7.5 ˚/s conditions are in the same format in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Fig. 2, for clarity.

The mean ± SD of perceived speed for the Carrier+Envelope condition was 16.5 ± 5.50 ˚/s for the 150 ms duration, 15.7 ± 4.12 ˚/s for the 300 ms duration, and 15.4 ± 4.83 ˚/s for the 600 ms duration. For the Carrier only condition, the mean perceived speed was 14.8 ± 6.64 ˚/s for the 150 ms duration, 13.1 ± 5.81 ˚/s for the 300 ms duration, and 12.6 ± 5.98 ˚/s for the 600 ms duration. The Envelope only condition showed mean perceived speeds of 16.9 ± 6.19 ˚/s for the 150 ms duration, 16.8 ± 5.17 ˚/s for the 300 ms duration, and 17.5 ± 5.80 ˚/s for the 600 ms duration.

Both the averaged data and individual participant data showed that the Carrier only motion condition resulted in lower speed estimates compared to the other two conditions featuring Envelope motion. To confirm this, a 2 (motion feature) × 3 (time) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on the data. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of motion feature (F2,26 = 9.46, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.421). However, the main effect of time was not significant after applying a Greenhouse-Geisser correction for a violation of sphericity (F1.30, 16.91 = 1.20, p = 0.305). Crucially, after the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied, the interaction between motion feature and time was no longer statistically significant (F2.32, 30.18 = 3.11, p = .052, partial η² = 0.193).

Therefore, we conducted post-hoc comparisons with a Bonferroni correction on the significant main effect of motion feature. These tests revealed that perceived speed in the Carrier only condition (M = 13.49, SD = 6.00) was significantly lower than in the Envelope only condition (M = 17.09, SD = 5.60; t(13) = -4.92, pBonferroni < 0.001, Cohen’s d = -1.32). However, there were no significant differences between the Carrier+Envelope condition (M = 15.88, SD = 4.24) and either the Carrier only condition ((t(13) = 2.25, pBonferroni = 0.127, Cohen’s d = 0.60) or the Envelope only condition ((t(13) = -1.21, pBonferroni = .301, Cohen’s d = -0.47) after correction.

Overall, these findings illustrate how carrier (first-order) motion and envelope (second-order) influence speed perception of global motion. Although the Carrier only condition yielded significantly lower speed estimates than the Envelope only condition, adding an envelope cue to the carrier did not result in a statistically significant increase in perceived speed. This suggests a mixed outcome where, although envelope (second-order) motion signals are a robust cue, carrier (first-order) motion signals still provide a substantial contribution to the global speed percept.

Differential and interacting contributions of envelope and carrier motion to the ocular following response

We investigated the OFRs during global motion perception task shown in Fig. 3b. The observed onset latency of eye movements was ~100 ms, which is longer than the typically reported 70-85 ms for human OFRs33. Eye acceleration in the Carrier+Envelope and Carrier-only conditions exhibited constant acceleration, lasting for ~350 ms. The mean absolute eye speed for the 150 ms and 600 ms conditions is shown in Fig. 3c (see Supplementary Fig. 1b for the 300 ms condition). In contrast to earlier studies on voluntary smooth pursuit, our results showed that second-order (envelope) motion was the primary driver of ocular following in our task20,21.

We examined the peak speeds of OFRs and their time point from the averaged eye velocity data. When the 12.5 ˚/s of global speed stimulus was presented for 150 ms, peak eye speed was 3.9 ˚/s (gain: 0.31) at 249 ms in the Carrier+Envelope motion condition, 0.9 ˚/s (gain: 0.07) at 202 ms in the Carrier motion only condition, and 1.9 ˚/s (gain: 0.15) at 231 ms in the Envelope motion only condition (Fig. 3c). Comparing this to the 7.5 ˚/s global speed stimulus presented for 150 ms, the peak eye speed in the condition with Carrier+Envelope motion was 2.9 ˚/s (gain: 0.38) at 245 ms (See Supplementary Fig. 1c). The Carrier motion only condition showed a peak of 0.8 ˚/s (gain: 0.11) at 180 ms, and the Envelope motion only condition reached 1.5 ˚/s (gain: 0.20) at 238 ms.

In the 300 ms presentation condition, we observed delayed and higher peak eye velocities similar to those in the 150 ms presentation condition (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The eye speeds showed a peak velocity of 5.0 ˚/s (gain: 0.40) at 365 ms in the Carrier+Envelope motion condition, 0.9 ˚/s (gain: 0.08) at 218 ms in the Carrier motion only condition, and 2.4 ˚/s (gain: 0.19) at 379 ms in the Envelope motion only condition. Under the 7.5 ˚/s global speed stimulus for 300 ms, Carrier + Envelope motion condition’s peak eye speed was 3.8 ˚/s (gain: 0.51) at 368 ms (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The Carrier motion only condition showed 0.9 ˚/s (gain: 0.12) at 388 ms, and the Envelope motion only condition reached 1.8 ˚/s (gain: 0.24) at 385 ms.

Finally, when stimuli were presented for 600 ms, the peak eye velocity and its timing were similar to those observed in the 300 ms presentation time condition. Peak velocities were 5.1 ˚/s (gain: 0.41) at 404 ms in the Carrier+Envelope motion condition, 0.9 ˚/s (gain: 0.07) at 211 ms in the Carrier motion only condition, and 2.3 ˚/s (gain: 0.19) at 370 ms in the Envelope motion only condition. In contrast, with the 7.5 ˚/s global speed stimulus presented for 600 ms, the peak eye speed reached 4.1 ˚/s (gain: 0.54) at 362 ms in the Carrier+Envelope motion condition, 0.8 ˚/s (gain: 0.11) at 375 ms in the Carrier motion only condition, and 1.9 ˚/s (gain: 0.25) at 386 ms in the Envelope motion only condition (Supplementary Fig. 1e).

Across all presentation durations and global target speeds, the Carrier+Envelope motion condition consistently elicited the highest peak eye speeds and gains, followed by the Envelope motion only condition, and then the Carrier motion only condition. Notably, lower global target velocities (7.5 ˚/s) generally resulted in lower peak eye speeds compared to the higher global target velocities (12.5 ˚/s) across all stimulus types. However, in some instances, the gain for the 7.5 ˚/s condition was comparable to or even slightly higher than the 12.5 ˚/s condition (for example, in the Carrier + Envelope condition at 600 ms, 0.54 versus 0.41). This suggests a more efficient tracking, relative to the target speed, at lower velocities. While OFRs do scale somewhat with global motion speed, the observed gains suggest they might be less sensitive to global motion speeds.

Short presentation time decreases speed discriminability of perceptual estimates, not of oculomotor outcomes

We found a striking contrast between perception and OFRs. Although the Carrier and Carrier+Envelope conditions possess similar motion energy and accordingly produced comparable perceptual speed estimates, the ocular following system responded profoundly differently; eye movements were minimal for the Carrier only condition but highly responsive to Carrier+Envelope motion, which clearly departs from the energy-based model’s predictions of similar outcomes for these two conditions. Conversely, in the Envelope motion only condition, both perceptual estimates and eye movements exhibited higher responses than expected, even though the energy-based model predicted reduced outcomes. Interestingly, this contrasts with studies showing that smooth pursuits are elicited by second-order stimuli, albeit with reduced responses. This suggests that the contribution of envelope (second-order) features to the OFR may be modulated in our global motion perception task.

We sought to directly compare the speed of eye movements and perceptual estimates to envelope motion signals. However, because perceptual and OFRs have different inherent noise, it is challenging to directly compare the sensitivity of the two systems to motion features. To address this, we performed Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) to observe how the envelope motion signal influences the signal-to-noise ratio of both OFRs and perceptual responses. LDA calculates discriminability, a metric that reflects the signal-to-noise ratio by indicating how much the signal (mean velocity) changes relative to the data’s inherent noise. Figure 3d shows the speed discriminability between the Carrier+Envelope and Carrier-only conditions, calculated to investigate the influence of superimposed envelope motion signal onto carrier motion signal on the ocular following and perceptual speeds. We found that the discriminability of perceptual speed is lower than that of OFRs, and that it is reduced for the 150 ms presentation time.

This latter finding appears to conflict with the results of our 2 (motion feature) × 3 (time) repeated-measures ANOVA on perceptual responses, which showed that the main effect of time was not significant. Post-hoc tests on the effect of time confirmed no significant differences in mean perceived speed between 150 ms and 300 ms (t(13) = 1.35, pBonferroni = 0.60), 300 ms and 600 ms (t(13) = 0.04, pBonferroni = 1.00), or 150 ms and 600 ms (t(13) = 1.05, pBonferroni = 0.93). However, this apparent discrepancy can be explained because the ANOVA tests for differences in the mean (signal), whereas discriminability also accounts for changes in mean plus variability (noise). An examination of the standard deviations of perceived speed shows a trend of decreasing perceptual noise with longer presentation times. An examination of the data reveals that the reduced perceptual discriminability at the 150 ms presentation time is due to a combination of a weaker signal (smaller mean difference between conditions) and higher noise (greater response variability). For instance, the mean difference in perceived speed between the Carrier + Envelope and Carrier only conditions was smallest at 150 ms (1.64) and increased with longer durations to 2.68 at 300 ms and 2.84 at 600 ms. Concurrently, an examination of the standard deviations (intra-individual variance) shows that perceptual noise was generally largest at the 150 ms presentation time. The SDs for the 150, 300, and 600 ms conditions were, respectively: 4.77, 4.69, and 4.52 for Carrier + Envelope; 4.93, 4.31, and 4.51 for Carrier only; and 5.19, 4.34, and 4.72 for Envelope only. This combination of a weaker signal and higher noise likely accounts for the reduced discriminability at 150 ms. This pattern contrasts with OFR initiation, which showed similar discriminability across all presentation time conditions.

Carrier motion alone is insufficient for direction estimation, but shows synergistic effect with envelope motion

The stimuli are designed to represent real-world motion signal distributions, involving the integration process of various motion signals into a global motion percept. To investigate how the visual system is tuned to integrate and resolve ambiguous local motion signals (known as the aperture problem) in perceptual and ocular following systems for global motion estimation, we analyzed the direction errors in both perceptual estimates and OFRs. Direction error, in this context, reflects the deviation of the system’s response from the true global motion direction, indicating how well the system applies the intersection of constraints rule to overcome local ambiguities and derive a coherent global motion percept (see Fig. 1).

In a matching task, direction errors were quantified as the absolute angular difference between the global motion direction and participants’ reported estimates and eye direction (Fig. 4a, b; see Methods for details). To characterize performance, we analyzed individual median direction errors using Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) across three stimulus conditions (Carrier+Envelope, Carrier, and Envelope) and durations (150 ms, 300 ms, and 600 ms) in Fig. 4a. For group-level representation, the reported median direction errors represent the median of individual participants’ median errors, and the MAD reflects the dispersion of these individual medians.

a Individual direction Error of perceptual estimates for 150 ms, 300 ms, and 600 ms. Capped error bars to the left of each time condition represent the mean of median ± 1 SEM. Clustered bar charts to the right of each time condition consist of three pairs of colored bars, each showing the direction error estimates for three local motion conditions. Each bar with a bright dot indicates the interquartile range (IQR) and median. The three bar pairs are arranged in ascending order of the individual grand median of direction error, maintaining consistency in participant order across all time conditions. The color saturation represents the three presentation durations: 150 ms (full), 300 ms (medium), and 600 ms (light). b Time-binned distributions of perceptual responses (green) overlapped on eye movement directions (see legend) in the 12.5 ˚/s condition. Data combined from 300 ms and 600 ms presentations. Each 50 ms time bin is represented by a different color. The different motion conditions are represented in Carrier+Envelope motion, carrier motion with stationary envelope, and envelope motion with stationary carrier. c Ocular following response error for each motion condition for 150 ms presentation durations. Data for the rest of conditions are displayed in the same format in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Fig. 3, for clarity. The shaded area indicates mean ± SEM. d, e Discriminability (d) between Carrier + Envelope and Carrier condition in 150 ms, 300 ms, and 600 ms duration, and (e) between two consecutive direction (22.5˚). Percent correct is calculated by linear discriminant analysis. Color saturation indicates the three presentation durations. The shaded area indicates mean ± SEM. Data for the 7.5 ˚/s conditions are in the same format in the Supplementary Information, Supplementary Fig. 2, for clarity.

The Carrier+Envelope condition consistently showed the lowest median direction errors: 5.73 ± 1.72 at 150 ms, 4.53 ± 1.49 at 300 ms, and 4.11 ± 1.72 at 600 ms (Median ± MAD). In contrast, the Carrier only condition exhibited the highest median direction errors: 19.18 ± 4.90 at 150 ms, 18.31 ± 4.05 at 300 ms, and 22.12 ± 5.06 at 600 ms (Median ± MAD). The Envelope-only condition presented an intermediate level of performance for median direction errors: 1.23 ± 2.24 at 150 ms, 8.99 ± 3.22 at 300 ms, and 8.92 ± 3.85 at 600 ms (Median ± MAD).

Both averaged and individual participant data suggested substantial differences in direction error across motion conditions. To confirm this, a 2 (motion feature) × 3 (time) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on the direction error data. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of motion feature (F2,26 = 256.45, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.901). Post-hoc comparisons showed that the Carrier+Envelope condition yielded significantly lower errors compared to both the Carrier-only (Mean Difference = -14.24, pBonferroni < 0.001) and Envelope-only (Mean Difference = -4.11, pBonferroni < 0.001) conditions. The Envelope only condition also resulted in significantly lower errors than the Carrier only condition (Mean Difference = 10.13, p < 0.001). The main effect of time was also statistically significant (F2,26 = 54.85, p = 0.006, partial η2 = 0.326). For the interaction between motion feature and time, a Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied, and this interaction remained statistically significant (F2.53,32.94 = 3.88, p = 0.023, partial η2 = 0.230).

Overall, the presence of an envelope significantly improved directional accuracy and reduced variability (Fig. 4b, c). The Carrier+Envelope combination yielded the most precise judgments, while the Carrier-only condition resulted in the highest errors, and the Envelope-only condition fell in between (Fig. 4b, c). The Carrier-only motion condition led to larger and more variable perceptual direction errors, indicating its insufficiency for accurately estimating global motion direction. Conversely, the Carrier + Envelope condition consistently exhibited the smallest perceptual direction errors across all time durations, suggesting that combining both motion features enhances the visual system’s ability to estimate global motion direction accurately. Furthermore, a significant main effect of time indicated that longer presentation durations improved direction estimation accuracy, with errors decreasing as stimulus duration increased.

Higher directional discriminability in perception compared to oculomotor responses

We began by inspecting the raw direction distributions for each motion signal type (Fig. 4b, see Supplementary Fig. 4 for 7.5 ˚/s speed condition). This initial observation suggested two key points. First, the overall variability appeared consistently higher for oculomotor responses than for perceptual reports. However, despite this clear difference in magnitude, both systems seemed to share a similar relative pattern of variability across the conditions.

To formally quantify these initial observations and compare the system’s sensitivities, we then applied the same LDA framework used in our prior speed analysis (cf. Fig. 3d). This quantitative analysis validated both of our initial findings. It confirmed that both systems share an similar relative pattern of variability, showing that adding an envelope signal has a similar effect in both cases, regardless of presentation timing (Fig. 4d). It also confirmed that the absolute noise level was indeed significantly higher in the oculomotor system (Fig. 4e). This suggests that while both the perceptual and oculomotor systems may draw from a shared sensory signal, the perceptual system is significantly more effective at separating this signal from its own internal noise, resulting in more reliable behavioral outcomes.

Delayed correlation between perceptual and eye direction suggests shared feedback signals

We previously observed a dissociation in the signal and noise patterns for speed, in contrast to direction information, which appeared to be shared between the perceptual and oculomotor systems. To further investigate whether the two systems share common signal and noise sources, we analyzed the trial-by-trial correlation between eye movements and perceptual responses (Fig. 5). Figure 5a illustrates the correlation between the final perceptual estimates and the OFRs over time for the 12.5°/s global motion condition (see Supplementary Supplementary Fig. 5 for similar results from the 7.5°/s condition). While the analysis revealed no significant clusters of correlation for speed, a significant time cluster emerged for the direction correlation during the later phase of eye movement initiation. Although eye speed increases nearly linearly from 100 ms up to ~300 ms (Fig. 3b, c), this significant direction correlation was confined to the later part of the acceleration period (194–266 ms), rather than the onset of the movement itself (Fig. 5a, right panel; cluster-based permutation test, p < 0.001). The timing of this cluster, occurring well after the eye movement onset at ~100 ms, suggests that it reflects processing beyond the initial open-loop period. This finding implies that a feedback mechanism begins to align both perceived direction and pursuit direction during this later acceleration phase.

a Time courses of correlation between perceptual estimations and eye movements for 12.5 ˚/s of global motion in Carrier+Envelope condition. Green shaded area represents mean ± SEM across participants. The left panel shows the speed correlation, and the right panel shows the direction correlation. Gray lines depict individual participant data. The red line with shaded area in plot with thick red line at the bottom indicates a significant time cluster (p < 0.001, cluster-based permutation test). b, c Comparison of correlation coefficients between the early phase (100–172 ms, initial eye movements) and the later phase (194–266 ms, defined by the significant time cluster). b Group data. Gray dots represent the mean correlation for each participant. Error bars indicate ±1 SEM. The asterisk denotes statistical significance (p < 0.001). c Scatter plots showing the relationship between perceptual estimations and eye movements for speed (left two panels) and direction (right two panels) during the early and later phases, respectively. Individual trials are shown as colored points, where each color represents a different participant. The red line indicates the grand regression line across all participants, while the gray lines show individual regression lines.

Discussion

In this study, we examined how the feature sensitivity of ocular following responses (OFRs) that arise during a global motion perception task aligns with (or diverges from) perceptual sensitivity to distinct motion features; carrier and envelope motion. Our findings reveal that both perceptual judgments and OFRs exhibit higher sensitivity to envelope motion, reflecting a common reliance on second-order motion signals, for both estimating speed and direction of global motion. In contrast, carrier motion primarily influenced perceived speed only (not perceived direction) and had limited influence on both speed and direction of OFRs. In speed discriminability analysis, the effectiveness of the envelope signal was reduced at short presentation timings, whereas for directional discriminability, both perception and ocular following were unaffected by presentation time and exhibited similar signal and noise characteristics, although perception consistently showed a better signal-to-noise ratio. Further trial-by-trial correlation analysis confirmed that ocular following and perceptual estimates are correlated in the later phase of eye movement initiation. This correlation was specific to direction, whereas no such relationship was found for speed, and its delayed timing suggests that a feedback mechanism, rather than an pure open-loop process, is responsible for modulating a shared directional signal between the two systems.

In contrast to previous studies that second-order motion ( ≈ envelope motion in this study) elicits compromised eye movements and neural responses21,22,48, our results demonstrate that viewing the carrier motion alone does not sufficiently drive the initiation of OFRs during global motion perception. This finding contrasts with previous studies that compared the effects of carrier or internal motion on smooth pursuit eye movements and perception using single-target paradigms. Hughes49 examined the influence of carrier motion during fixation (in a preliminary experiment), steady-state pursuit, and a subsequent speed discrimination task. They reported a strong effect of carrier motion on pursuit gain, but less consistent effects on perceived speed, and a perceptual bias during fixation. Wu et al. 50 reported that smooth pursuit with internal motion target was consistently biased in the direction of internal motion, whereas perceptual biases were inconsistent across observers. Maechler et al. 51 showed that directional biases of smooth pursuit eye movements tracking an inferred location based on peripheral targets were driven by the perceived positions, not their physical positions. Mukherjee, et al. 37, demonstrated that aperture movement in random dot kinematograms significantly affects pursuit initiation acceleration. Unlike these studies, our paradigm focused on the initiation of OFRs, which is naturally generated during global motion perception. This distinction underscores that the visual system dynamically adjusts feature sensitivity depending on task goals, and that the feature sensitivity of OFRs observed during perception differs not only from that of conventional smooth pursuit eye movement paradigms, but also from that of the perceptual system.

Several studies have examined how the visual system integrates motion signals across space and how this process compares between perception and initiation of OFRs. Watamaniuk and Heinen28 showed that, using random dot kinematograms with varying levels of motion noise, both smooth pursuit and perceptual direction judgments remained reliably biased toward the signal motion direction, suggesting that the two systems share robust spatial integration mechanisms under noisy conditions. Boström & Warzecha52 found that perceptual speed discrimination was significantly more sensitive than the OFR and that the two system’s responses were uncorrelated. Simoncini et al. 26 showed that increasing the spatiotemporal bandwidth of motion stimuli enhanced OFRs while impairing perceptual speed discrimination, suggesting that the two systems employ different gain control mechanisms for motion integration. Especially, for the 12.5 ˚/s condition, our result that overall matched speed with 1/F noise stimuli containing envelope motion was higher than global speed of stimuli is consistent with a their finding that perceived speed is reduced with broad band stimuli26. However, this effect was not observed for stimuli with only carrier motion (Fig. 3a). In contrast, for the 7.5 °/s condition, the change in perceptual speed was not as large as the difference in global motion speed relative to the 12.5 °/s condition, and a similar trend was observed in the eye velocity (Supplementary Fig. 1). As a result, at this slower speed, the matched perceptual speeds were consistently higher than the global motion speed across all local motion signal types.

By comparing maintained fixation and steady-state pursuit, both of which involve a target stabilized on the fovea, researchers have investigated how extra-retinal signals influence the processing of visual input and how smooth pursuit eye movements differ from motion perception under matched retinal conditions. For example, Hafed and Krauzlis53 demonstrated that ongoing eye movements, such as smooth pursuit, can constrain visual perception and significantly enhance perceptual coherence, even when retinal stimulation remains constant. They showed that this occurs because motor commands provide crucial extra-retinal spatial information that helps resolve inherent ambiguities in visual inputs, leading to a more coherent percept during tracking than during fixation. Tavassoli and Ringach27 found that smooth pursuit eye movements exhibit greater sensitivity than perceptual responses in tasks involving target perturbation discrimination. Spering and Gegenfurtner54 showed that motion perception and smooth pursuit process contextual motion differently: perception relies on motion contrast, while pursuit reflects motion assimilation. Souto et al. 55 further demonstrated that motion integration during smooth pursuit is anisotropic, with stronger integration occurring along the pursuit axis.

It could indicate that the distinction in signal integration in different channels may be tailored to unique demands of each type of visual objective, whether it be for the reflexive tracking of visual image in OFRs or the voluntary pursuit of a singular object in smooth pursuit eye movements6.

The findings of our study have significant implications for the configuration of step ramp targets used for research on the initiation of smooth pursuit eye movements. The classical step ramp paradigm is configured such that a pursuit target is initially displaced to the opposite side of the target movement direction. This ensures that tracking eye movements begin immediately once the target moves across the fovea, eliminating smooth pursuit latency. This method inadvertently has potential compromise that causes position-based motion in the opposite direction to the intended target direction24. Recent research has attempted to mitigate this concern by employing local motion for the step-ramp target (with a phase shift of a sinusoidal carrier grating); however, our data indicate that local motion for step-ramp and the movement of a rigid image for tracking have distinct influences on smooth eye movements4,12,44,45. It is important, however, to clarify that our study focuses on OFRs, which are distinct from voluntary pursuit. Specifically, as a global motion perception study, our work primarily elicits these reflexive ocular following behaviors. While our approach differs from classic pursuit paradigms, our findings nonetheless highlight potential methodological issues within them. Therefore, given the differences between our study of ocular following and the broader literature on smooth pursuit, we believe further research is needed to reconcile how these related smooth eye movement behaviors are influenced by various task paradigms.

Methods

Participants

Data were collected from 20 participants (9 male and 11 female, mean age: 24.3 ± 6.2 years). We excluded the data from 6 participants who completed fewer than 400 trials in further analysis, which was decided by trial number distribution. The excluded participants include those who showed poor quality eye tracking recordings, e.g. trials were frequently self-canceled or the participant took excessive breaks during the task. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. The Institutional Review Board of Northeastern University approved the study and all ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants were either undergraduate students compensated with course credit or individuals who volunteered to participate.

Apparatus and experimental procedure

All visual stimuli were presented on a gamma-corrected 27-inch LCD monitor (BENQ XL2720Z; maximum and minimum luminance of 247.7 cd/m2 and 1.25 cd/m2, respectively, and luminance of the gray background was 124.5 cd/m2) with a spatial resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels and a vertical refresh rate of 144 Hz. Control of visual stimuli and acquisition of eye position signals were performed using Psychtoolbox56 and the Eyelink Toolbox57 in Matlab. Participants were seated at a viewing distance of 64 cm from the monitor in an otherwise dim room. The participants placed their heads on a chinrest to reduce noise from head movements. The entire experiment took about 1 h including a training session and self-paced breaks.

Each trial started with the appearance of a central white fixation spot. Subjects were required to maintain fixation within an invisible square window ( ± 1°) around fixation for 1250, 1500 or 1750 ms at random between trials before the stimuli were presented. After successful fixation, one of three Gabor motion arrays (see below for details), selected at random between trials, were presented. Note that the first frame of all stimuli was identical, so participants had no way of knowing which condition was being presented until the stimuli moved.

Other than the requirement to fixate the spot at the start of each trial, there were no other instructions about the participants’ eye movements, therefore, they were able to move their eyes freely. We took this step to avoid participants adopting stereotyped eye movement patterns and to study natural behavior to noisy, complex stimuli. After the Gabor motion array was viewed, participants were asked to report the global direction and speed of the Gabor motion array using a probe stimulus, the speed and direction of which was adjusted in real time with a mouse (see Fig. 2B). The task was to match the direction and speed of the probe stimuli to the global apparent direction and speed of the Gabor motion pattern. The probe stimulus consisted of two concentric circles (15° and 6.6°) forming an annulus. The motion probe stimulus appeared in the center of the annulus when the participants placed their cursor in the area between the two annuli. The orientation of cursor relative to the center determined the direction of motion of the probe stimulus and the distance from the center determined its speed. Once the observer was satisfied that the speed and direction of the probe stimulus matched that of the Gabor array, they were instructed to press the left mouse button to record the response. A time window of 5 s was imposed. On average, participants completed 470 ± 11 trials.

Stimuli

In each trial, one of three types of Gabor (standard deviation 0.35˚, spatial frequency 0.5 cycle/˚, and Michelson contrast 100%) motion arrays was presented for 150, 300, or 600 ms. The first screen of the three types of stimuli was identical, then, either the Gabor carriers, the Gabor envelopes or both carrier and envelope were moved toward a global motion direction at a speed of 7.5 or 12.5°/s. The global direction of motion of the Gabor array was randomly chosen from sixteen evenly spaced directions (0°, ±22.5°, ±45°, ±67.5°, ±90°, ±115.5°, ±135°, ±157.5°, and 180°). The orientations of the Gabors were randomly selected from eight evenly spaced orientations (0°, 22.5°, 45°, 67.5°, 90°, 115.5°, 135°, and 157.5°). The local speed of each Gabor was dependent on the projected vector of the global motion and on each Gabor’s orientation.

Gabor centers were randomly assigned to positions within an invisible square window (25° × 25°, i.e., ±12.5° from fixation), and only Gabors falling within a radius of 12.5° from the center of the screen were rendered visible. In conditions involving envelope motion, each Gabor envelope moved across this invisible square window. When a Gabor reached one edge of the square, it was repositioned to the opposite edge, effectively wrapping around the invisible square window. As before, only Gabors falling within a radius of 12.5° from the center of the screen were rendered visible. The use of this additional square window, instead of only use of the circular invisible window, was intended to prevent Gabors from abruptly disappearing or reappearing near the edge of the circular aperture, which could otherwise disrupt the perception of continuous motion and produce flicker-like artifacts. As a result, approximately 83 Gabors were shown in each frame.

The matching stimulus was 1/F (Pink) noise that was presented with a Gaussian envelope (standard deviation 1.5˚) with 100% peak Michelson contrast. Pink noise was used as the matching probe stimulus instead of Gabor gratings because of its broad spatial frequency, temporal frequency and orientation content. The speed of the Pink noise was under the control of the participant, as described above, in the range 0-37.5 ˚/s. A video of the task performance can be found in our data and code repository.

Acquisition and analysis of eye movements

For each participant, binocular gaze positions were acquired using an infrared eye tracker (EyeLink 1000 Plus, SR research) with a sampling rate of 1 kHz under control of the Eyelink Toolbox57. The eye tracker was calibrated using the default calibration by presenting a circular point in nine positions.

Eyelink edf datafiles were converted to Matlab files using Edf2Mat Matlab Toolbox designed and developed by Adrian Etter and Marc Biedermann at the University of Zurich (https://github.com/uzh/edf-converter), from which we calculated velocity by differentiation of the eye position data with the Matlab function gradient(). The velocity data were smoothed to remove high-frequency signals with a low-pass filter (20 Hz, 2nd order Butterworth filter).

Given our interest in how motion features influence the initiation of eye movements, we focused our analysis on the initiation of OFRs. To exclude trials contaminated by saccadic or unexpected eye movements, we employed an automated saccade detection algorithm58 rather than relying on manual classification35,44,50,59,60. This algorithm, originally developed for detecting (micro)saccades during fixation by identifying sustained deviations from the velocity distribution, was adapted to detect movements unrelated to OFRs by adjusting the detection threshold according to the variability in each phase of eye movement. Therefore, we adjusted both the baseline time window and the standard deviation threshold of the algorithm. All saccade detection results were visually inspected to verify the reliability of the algorithm and ensure that only trials reflecting clean OFRs were retained for further analysis.

Main data were segmented relative to stimulus onset, from −300 ms to +400 ms. Trials containing missing samples were excluded (0.6% of the total dataset). The saccade detection was then performed on unrotated eye velocity data for each motion condition. To examine the later phase of eye movement, additional data segmentation were performed from −300 ms to +550 ms for 300 ms presentation condition (1.5% of the total dataset excluded) and −300 ms to +850 ms for 600 ms presentation condition (2.0% of the total dataset excluded). These datasets were used solely for the plots of time-resolved eye velocity and direction errors in the 300 ms and 600 ms presentation conditions.

Then, to ensure that participants maintained fixation during the initial phase of motion presentation, we identified trials containing saccadic or unexpected eye movements in the period of main dataset ( − 100 to +100 ms relative to stimulus onset)59,60. The standard deviation of the velocity distribution was calculated from a window of -200 to 0 ms relative to stimulus onset across trials, then eye movements whose velocity exceeded a threshold ≥ 6 standard deviations of that distribution and with the duration ≥ 6 ms were classified as saccades58. This procedure yielded an elliptical saccade detection boundary in velocity space, with the corresponding thresholds of ηx = 5.2 ± 0.2 ˚/s and ηy = 6.1 ± 0.3 ˚/s across overall global speed conditions and motion signal conditions. On average, 18.5% of trials were excluded in this step.

Next, we assumed that OFRs are initiated in a time window of 100 to 250 ms relative to stimulus onset (Fig. 3b). In the initiation of OFRs, it is expected that eye velocity slowly increases and is usually less than the stimulus velocity. The saccade detection thresholds were based on the standard deviation of the eye movement velocity in the time window of 150 to 250 ms, which was the later part of initiation of eye movements. Therefore, the detection algorithm was used to capture excessive velocity deviations, including potential saccades not attributable to OFRs, while also allowing for the possibility that OFRs might not have been initiated at all. Because velocity is more variable in initiation of eye movements and we wanted to detect and exclude only extraordinary eye movements, we used a higher threshold than used for saccade detection during the fixation interval. Therefore, we applied a criterion of 8 standard deviations based on a window of 150 to 250 ms relative to stimulus onset across trials. From the data that had already excluded trials with saccades during the fixation period, an additional 0.2% of trials were rejected based on saccade detection in this open-loop window. To see the thresholds calculated in the procedure, See Supplementary Table 1.

To examine closed-loop periods of OFRs, we plotted the eye velocity in the direction of global motion in the 300 ms and 600 ms durations for each motion condition. In the 600 ms presentation condition, we identified saccades in the time windows from 250 ms to 600 ms relative to stimulus onset using the same baseline window for each motion condition. To detect saccades more conservatively considering the larger variability of eye velocity in this interval, we used a threshold of 10 standard deviations. The thresholds derived from this procedure are in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. Figure 3b, c and 4c is plotted excluding 50 ms data before onset and 50 ms after the offset of saccades detected with this criterion. For the 300 ms presentation condition, saccades were detected in the time window from 250 ms to 600 ms to examine eye movements after stimulus offset.

Peak velocity in each presentation time condition was estimated within specific time windows relative to stimulus onset between 0 ms and 300 ms for the 150 ms presentation, 0 ms and 500 ms for the 300 ms presentation, and 0 ms and 600 ms for the 600 ms presentation.

For the trial-by-trial correlation analysis, we removed outliers from the perceptual reports. Specifically, trials exceeding ±3 standard deviations from the mean were excluded. This process led to the removal of ~1% of the data.

Statistical analyses

To test the statistical significance of the effects of stimulus signal types on behavioral performance in the speed and direction matching task, we conducted two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs and calculated partial η2 as a measure of effect size using jamovi (2.3.28). For all repeated-measures ANOVAs, the assumption of sphericity was evaluated using Mauchly’s test. If the assumption was violated, the degrees of freedom were corrected using the Greenhouse-Geisser method. Following a significant interaction in the ANOVA, further comparison analyses were performed using paired t-tests, with a Bonferroni correction applied to adjust for multiple comparisons.

To identify time periods where eye velocity significantly deviated from zero while correcting for multiple comparisons, we performed a non-parametric cluster-based permutation test implemented in the FieldTrip toolbox for MATLAB61. This procedure tested the observed eye velocity time-series against the null hypothesis of no deviation from zero. The analysis proceeded in two steps. First, a dependent-samples t-test was conducted at each time point, comparing the observed data to zero. All adjacent time points exceeding an uncorrected significance level of p < 0.05 were grouped into clusters. Second, a cluster-level statistic was computed for each cluster by summing the t-values of all its constituent time points (maxsum). To generate a null distribution, this entire procedure was repeated 10,000 times, with the data labels randomly permuted for each iteration. An observed cluster was considered statistically significant if its cluster statistic fell into the top 2.5% or bottom 2.5% of this null distribution, corresponding to a two-sided test with a significance level of p < 0.05.

We defined the time window of the significant cluster as the later phase and, for comparison, an early phase of the same duration after eye movement onset. The data from this early phase was subsequently tested against zero with a one-sample t-test.

Linear discriminant analysis

Although both OFRs and perceptual responses are measured in the same units (˚/s for speed, ˚ for direction), they exhibit inherently different means (signal) and levels of variability (noise). This makes a direct comparison of their sensitivity to motion features challenging. Therefore, we used Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) to compute a single index of discriminability, which reflects the signal-to-noise ratio of each system’s response. We calculated the discriminability between the Carrier+Envelope and Carrier-only conditions to specifically quantify the effect of envelope motion. A higher discriminability score would indicate that adding envelope motion produced a more distinct representation, either by increasing the mean separation between the conditions (signal) or by reducing their variability (noise). We adopted a leave-one-trial-out cross-validation approach, where one trial was held out as test data while the remaining trials were used for training of linear discriminant classifier.

Although the number of trials was generally balanced between the two conditions, slight variations arose due to random assignment of task variables. Since the decision boundary can be biased toward the majority class, especially when classes are not separable, we employed a conservative resampling strategy. Specifically, we randomly sampled a subset of trials from the condition with a larger number of trials to match the number of trials in the condition with fewer trials. The resampled data were then used to train the LDA classifier and the held out trial was used as test data. This process was repeated for all trials to ensure robust validation of the classification accuracy. Although the number of trials in the Carrier + Envelope and Carrier-only conditions was typically similar across participants and sessions, slight imbalances occasionally occurred due to the randomization of task parameters. This ensured that classification performance reflected meaningful signal differences between the two conditions, rather than being driven by unequal class frequencies.

Discriminability was calculated by comparing the Carrier+Envelope and Carrier only conditions for each presentation time condition. Additionally, for direction discriminability, we further calculated how well two adjacent directions were discriminated by comparing data from directions separated by 22.5˚ intervals. For this particular analysis, data were combined across all presentation timings due to insufficient trial numbers within individual timing conditions.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Preprocessed behavioral and eye tracking data have been deposited in OPENICPSR (https://doi.org/10.3886/E207887V5)62.

Code availability

Code is available in OPENICPSR (https://doi.org/10.3886/E207887V5)62. The code was written in Matlab (version 2022b).

References

Katz, L. N., Yates, J. L., Pillow, J. W. & Huk, A. C. Dissociated functional significance of decision-related activity in the primate dorsal stream. Nature 535, 285–288 (2016).

Osborne, L. C., Lisberger, S. G. & Bialek, W. A sensory source for motor variation. Nature 437, 412–416 (2005).

Maunsell, J. H. & Van Essen, D. C. Functional properties of neurons in middle temporal visual area of the macaque monkey. I. Selectivity for stimulus direction, speed, and orientation. J. Neurophysiol. 49, 1127–1147 (1983).

Lisberger, S. G. Visual guidance of smooth pursuit eye movements. Annu Rev. Vis. Sci. 1, 447–468 (2015).

Lisberger, S. G. Visual guidance of smooth-pursuit eye movements: sensation, action, and what happens in between. Neuron 66, 477–491 (2010).

Choi, K., Woo, S. & Lee, J. Motor-effector dependent modulation of sensory-motor processes identified by the multivariate pattern analysis of EEG activity. Sci. Rep. 13, 3161 (2023).

Kowler, E. Eye movements: the past 25 years. Vis. Res 51, 1457–1483 (2011).

Spering, M. & Montagnini, A. Do we track what we see? common versus independent processing for motion perception and smooth pursuit eye movements: a review. Vis. Res. 51, 836–852 (2011).

Spering, M. & Carrasco, M. Acting without seeing: eye movements reveal visual processing without awareness. Trends Neurosci. 38, 247–258 (2015).

Saproo, S. & Serences, J. T. Attention improves transfer of motion information between V1 and MT. J. Neurosci. 34, 3586–3596 (2014).

Krauzlis, R. J. Recasting the smooth pursuit eye movement system. J. Neurophysiol. 91, 591–603 (2004).

Park, J., Kim, S., Kim, H. R. & Lee, J. Prior expectation enhances sensorimotor behavior by modulating population tuning and subspace activity in sensory cortex. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg4156 (2023).

Ditterich, J., Mazurek, M. E. & Shadlen, M. N. Microstimulation of visual cortex affects the speed of perceptual decisions. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 891–898 (2003).

Son, S., Moon, J., Kim, Y. J., Kang, M. S. & Lee, J. Frontal-to-visual information flow explains predictive motion tracking. Neuroimage 269, 119914 (2023).

Liu, L. D. & Pack, C. C. The contribution of area MT to visual motion perception depends on training. Neuron 95, 436–446 e433 (2017).

Mante, V., Sussillo, D., Shenoy, K. V. & Newsome, W. T. Context-dependent computation by recurrent dynamics in prefrontal cortex. Nature 503, 78–84 (2013).

O’Keefe, L. P. & Movshon, J. A. Processing of first- and second-order motion signals by neurons in area MT of the macaque monkey. Vis. Neurosci. 15, 305–317 (1998).

Vaina, L. M. & Soloviev, S. First-order and second-order motion: neurological evidence for neuroanatomically distinct systems. Prog. Brain Res. 144, 197–212 (2004).

Smith, A. T., Greenlee, M. W., Singh, K. D., Kraemer, F. M. & Hennig, J. The processing of first- and second-order motion in human visual cortex assessed by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). J. Neurosci. 18, 3816–3830 (1998).

Butzer, F., Ilg, U. J. & Zanker, J. M. Smooth-pursuit eye movements elicited by first-order and second-order motion. Exp. Brain Res. 115, 61–70 (1997).

Lindner, A. & Ilg, U. J. Initiation of smooth-pursuit eye movements to first-order and second-order motion stimuli. Exp. Brain Res. 133, 450–456 (2000).

Hawken, M. J. & Gegenfurtner, K. R. Pursuit eye movements to second-order motion targets. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 18, 2282–2296 (2001).

Glasser, D. M. & Tadin, D. Increasing stimulus size impairs first- but not second-order motion perception. J. Vis. 11, 22–22 (2011).

Wilmer, J. B. & Nakayama, K. Two distinct visual motion mechanisms for smooth pursuit: evidence from individual differences. Neuron 54, 987–1000 (2007).

Sheliga, B. M., Chen, K. J., Fitzgibbon, E. J. & Miles, F. A. Initial ocular following in humans: a response to first-order motion energy. Vis. Res. 45, 3307–3321 (2005).

Simoncini, C., Perrinet, L. U., Montagnini, A., Mamassian, P. & Masson, G. S. More is not always better: adaptive gain control explains dissociation between perception and action. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1596–1603 (2012).

Tavassoli, A. & Ringach, D. L. When your eyes see more than you do. Curr. Biol. 20, R93–R94 (2010).

Watamaniuk, S. N. & Heinen, S. J. Human smooth pursuit direction discrimination. Vis. Res. 39, 59–70 (1999).

Ledgeway, T. & Hess, R. F. Failure of direction identification for briefly presented second-order motion stimuli: evidence for weak direction selectivity of the mechanisms encoding motion. Vis. Res. 42, 1739–1758 (2002).

Priebe, N. J., Churchland, M. M. & Lisberger, S. G. Reconstruction of target speed for the guidance of pursuit eye movements. J. Neurosci. 21, 3196–3206 (2001).

Derrington, A. M., Badcock, D. R. & Henning, G. B. Discriminating the direction of second-order motion at short stimulus durations. Vis. Res 33, 1785–1794 (1993).

Kreyenmeier, P., Kumbhani, R., Movshon, J. A. & Spering, M. Shared mechanisms drive ocular following and motion perception. Eneuro 11, ENEURO.0204-24.2024 (2024).

Gellman, R. S., Carl, J. R. & Miles, F. A. Short latency ocular-following responses in man. Vis. Neurosci. 5, 107–122 (1990).

Miles, F. A., Kawano, K. & Optican, L. M. Short-latency ocular following responses of monkey. I. Dependence on temporospatial properties of visual input. J. Neurophysiol. 56, 1321–1354 (1986).

Jeong, W., Kim, S., Park, J. & Lee, J. Multivariate EEG activity reflects the Bayesian integration and the integrated Galilean relative velocity of sensory motion during sensorimotor behavior. Commun. Biol. 6, 113 (2023).

Rasche, C. & Gegenfurtner, K. R. Precision of speed discrimination and smooth pursuit eye movements. Vis. Res. 49, 514–523 (2009).

Mukherjee, T., Battifarano, M., Simoncini, C. & Osborne, L. C. Shared sensory estimates for human motion perception and pursuit eye movements. J. Neurosci. 35, 8515–8530 (2015).

Nishida, S. Y., Kawabe, T., Sawayama, M. & Fukiage, T. Motion perception: from detection to interpretation. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 4, 501–523 (2018).

Pack, C. C. & Born, R. T. Temporal dynamics of a neural solution to the aperture problem in visual area MT of macaque brain. Nature 409, 1040–1042 (2001).

Amano, K., Edwards, M., Badcock, D. R. & Nishida, S. Adaptive pooling of visual motion signals by the human visual system revealed with a novel multi-element stimulus. J. Vis. 9, 4.1–25 (2009).

Masson, G. S. From 1D to 2D via 3D: dynamics of surface motion segmentation for ocular tracking in primates. J. Physiol. Paris 98, 35–52 (2004).

Masson, G. S. & Perrinet, L. U. The behavioral receptive field underlying motion integration for primate tracking eye movements. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 1–25 (2012).

Lisi, M. & Cavanagh, P. Dissociation between the Perceptual and Saccadic Localization of Moving Objects. Curr. Biol. 25, 2535–2540 (2015).

Lee, J. & Lisberger, S. G. Gamma synchrony predicts neuron-neuron correlations and correlations with motor behavior in extrastriate visual area MT. J. Neurosci. 33, 19677–19688 (2013).

Egger, S. W. & Lisberger, S. G. Neural structure of a sensory decoder for motor control. Nat. Commun. 13, 1829 (2022).

Hubel, D. H. & Wiesel, T. N. Receptive fields of single neurones in the cat’s striate cortex. J. Physiol. 148, 574–591 (1959).

Chubb, C. & Sperling, G. Drift-balanced random stimuli: a general basis for studying non-fourier motion perception. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 5, 1986–2007 (1988).

Ilg, U. J. & Churan, J. Motion Perception Without Explicit Activity in Areas MT and MST. J. Neurophysiol. 92, 1512–1523 (2004).

Hughes, A. E. Dissociation between perception and smooth pursuit eye movements in speed judgments of moving Gabor targets. J. Vis. 18, 4–4 (2018).

Wu, X. & Spering, M. Tracking and perceiving diverse motion signals: Directional biases in human smooth pursuit and perception. PLoS ONE 17, e0275324 (2022).

Maechler, M. R., Heller, N. H., Lisi, M., Cavanagh, P. & Tse, P. U. Smooth pursuit operates over perceived not physical positions of the double-drift stimulus. J. Vis. 21, 6 (2021).

Bostrom, K. J. & Warzecha, A. K. Open-loop speed discrimination performance of ocular following response and perception. Vis. Res. 50, 870–882 (2010).

Hafed, Z. M. & Krauzlis, R. J. Ongoing eye movements constrain visual perception. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1449–1457 (2006).

Spering, M. & Gegenfurtner, K. R. Contrast and assimilation in motion perception and smooth pursuit eye movements. J. Neurophysiol. 98, 1355–1363 (2007).

Souto, D., Chudasama, J., Kerzel, D. & Johnston, A. Motion integration is anisotropic during smooth pursuit eye movements. J. Neurophysiol. 121, 1787–1797 (2019).

Brainard, D. H. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat. Vis. 10, 433–436 (1997).

The MathWorks. Eyelink toolbox. https://in.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/3176-eyelink-toolbox (2023).

Engbert, R. & Kliegl, R. Microsaccades uncover the orientation of covert attention. Vis. Res 43, 1035–1045 (2003).

Lee, J., Yang, J. & Lisberger, S. G. Control of the gain of visual-motor transmission occurs in visual coordinates for smooth pursuit eye movements. J. Neurosci. 33, 9420–9430 (2013).

Hohl, S. S., Chaisanguanthum, K. S. & Lisberger, S. G. Sensory population decoding for visually guided movements. Neuron 79, 167–179 (2013).

Maris, E. & Oostenveld, R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods 164, 177–190 (2007).

Moon, J. & Bex, P. Data and code - Distinctive Feature Sensitivity of Ocular Following Initiation during Global Motion Perception. https://www.openicpsr.org (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH R01EY032162. We thank Joonyeol Lee (Center for Neuroscience Imaging Research, Institute for Basic Science and Department of Biomedical Engineering, Sungkyunkwan University) for the constructive comments on earlier version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, JM and PB; Methodology, JM and PB; Investigation, JM and PB; Formal Analysis, JM and PB; Writing – Original Draft, JM and PB; Writing – Review and Editing, JM and PB; Funding Acquisition, PB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Matteo Lisi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jasmine Pan. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moon, J., Bex, P. Distinctive feature sensitivity of ocular following initiation during global motion perception. Commun Biol 8, 1808 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09114-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09114-4

This article is cited by

-

Distinctive feature sensitivity of ocular following initiation during global motion perception

Communications Biology (2025)