Abstract

Subduction zones metamorphic fluids are pivotal in geological events such as volcanic eruptions, seismic activity, mineralization, and the deep carbon cycle. However, the mechanisms governing carbon mobility in subduction zones remain largely unresolved. Here we present the first observations of immiscible H2O-CH4 fluids coexisting in retrograde carbonated eclogite from the Western Tianshan subduction zone, China. We identified two types of fluid inclusions in host ankerite and amphibole, as well as in garnet and omphacite. Type-1 inclusions are water-rich with CH4 vapor, whereas Type-2 are CH4-rich, with minimal or no H2O. The coexistence of these fluid types indicates the presence of immiscible fluid phases under high-pressure conditions (P = 1.3-2.1 GPa). Carbonates in subduction zones can effectively decompose through reactions with silicates, leading to the generation of abiotic CH4. Our findings suggest that substantial amounts of carbon could be transferred from the slab to mantle wedge as immiscible CH4 fluids. This process significantly enhances decarbonation efficiency and may contribute to the formation of natural gas deposits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Massive carbonates preserved in seafloor sediments and altered oceanic crust are transferred into subduction zones, and different views on their behavior have led to controversy on the estimation of subduction carbon flux1,2,3,4,5. Early experimental and phase equilibrium modeling studies suggest that metamorphic decarbonation and dehydration are decoupled in closed systems during subduction6,7,8. However, phase equilibrium modeling in open systems shows that adding H2O-rich fluid can enhance decarbonation reactions9,10,11,12. Partial melting of the altered oceanic crust can occur at ~120 km, forming carbonate melts1,13,14, though this is mostly limited to localized environments in hot subduction zones. In contrast, carbonate dissolution is considered as the primary decarbonation mechanism in cold subduction zones15,16. Nonetheless, these decarbonation studies only focused predominantly on CO2 and have overlooked methane (CH4), which is also a critical carbon species in subduction zones.

Moreover, determining the behavior and mobility of carbon species in metamorphic fluids during subduction is a vibrant yet formidable area of scientific inquiry. Previous experimental investigations of CH4–H2O fluids indicate that at temperatures below 400 °C, a single CH4–H2O fluid will separate into a CH4-rich fluid and a H2O-rich fluid in shallow depth of sedimentary basin, thus setting an upper-temperature limit for the entrapment temperature of the fluid inclusions17. Thermodynamic evaluations also show that immiscible H2O–CO2 fluids are stable only at temperatures below 400–450 °C in the C–O–H system18. However, recent experimental studies reveal that pressure can significantly expand the immiscibility gap of C–H–O fluids, allowing immiscible C–O–H fluids to exist under subduction zone conditions of 1.5–3.0 GPa and 300–700 °C19,20. The likely occurrence of immiscible C–O–H fluids could lead to extensive decarbonation and serve as a crucial mechanism for the transfer of slab carbon to the mantle wedge. Immiscible H2O–CH4 fluids have been observed in the Alps metasomatized ophicarbonates at <1.5 GPa and ~450 °C21 and in Myanmar jadeitite at 0.6–0.7 GPa and 300–400 °C22. However, direct textural evidence demonstrating the coexistence of two immiscible H2O–CH4 fluid phases at higher temperature and pressure conditions, particularly in high pressure–ultrahigh pressure (HP–UHP, refer to the Supplementary Material) eclogite, remains scarce.

The Chinese Western Tianshan HP–UHP metamorphic belt, the largest oceanic deep subduction zone worldwide23 (see Supplementary Material and Fig. S1), offers a unique opportunity to investigate the fate of the subducted carbonates and the composition and behavior of C–O–H fluids in subduction zones. Here, we present the first observation of two distinct types of fluid inclusions—H2O-rich and CH4-rich—found in amphibole (specifically actinolite) and ankerite (a kind of Fe-dolomite), as well as in garnet and omphacite, within carbonated eclogite from the Western Tianshan metamorphic belt. Our findings demonstrate that immiscible CH4–H2O fluids can occur during HP metamorphism, highlighting an important mechanism for transferring slab carbon to the mantle wedge.

Results and discussion

Mineral assemblage and volume content

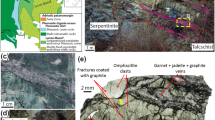

The carbonated eclogite sample (HB142-1) collected from the Western Tianshan metamorphic belt in China has experienced extensive retrograde metamorphism and carbonation. It predominantly comprises amphibole (37%), ankerite (19%), zoisite (18%), garnet (7%) and quartz (5%), with minor remnants of omphacite (2.5%) (Fig. 1). The specific mineral assemblages and their corresponding metamorphic stages are summarized detailed in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Prograde ankerite and its inclusions

The ankerite porphyroblasts in this study exhibit well-defined prograde zoning (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S3). The XMn [=Mn/(Ca + Mg + Fe2+ + Mn)] content of the ankerite decreases from the core (0.65%) to the rim (0.05%), while XCa [=Ca/(Ca + Mg + Fe2+ + Mn)], (45%–51%) is relatively homogeneous. The XFe [=Fe2+/(Ca + Mg + Fe2+ + Mn)] continuously decreases from 16% to 8%, while the XMg [=Mg/(Ca + Mg + Fe2+ + Mn)] increases from 37% to 44%, corresponding to core to rim (Supplementary Fig. S3c). Thus, Fe# [=Fe/(Fe2+ + Mg)] decreases accordingly from 0.32–0.27 in the core, via 0.24–0.21 in the mantle, to 0.19–0.16 in the rim (Supplementary Fig. S3c). The residual ankerite core has been replaced by newly formed ankerite and quartz (Fig. 2a, b, Supplementary Fig. S3 and Table S1).

a Element iron (Fe) mapping of ankerite (Ank) illustrates the well-preserved ankerite chemical zoning. The residual bright Ank core is replaced by the darker Ank and quartz (Qz). b Enlarged BSE image showing the inclusions of lawsonite (Law), graphite (Gr), chlorite (Chl), talc (Tlc) and actinolite (Act) in Ank core in (a). c Calcite (Cal) and Qz inclusion in Ank. d Magnisite (Mgs) inclusion in Ank. e Fluid inclusions (FIs) in Ank core are parallel to the cleavage direction of Ank, belonging to primary fluid inclusions. f Fluid inclusions in Ank rim are beaded along the fracture, belonging to secondary fluid inclusions. g Raman spectra showing the differences of Raman peaks among Ank, Cal and Mgs.

The ankerite core contains prograde inclusions such as graphite, chlorite, actinolite, talc and lawsonite (Fig. 2b), as well as calcite (probably after aragonite; Fig. 2b, c) and magnesite (Fig. 2d). The Fe# of most magnesite inclusions (Supplementary Fig. S4) in ankerite is 0.36–0.25, with a few prograde remnants of 0.47–0.46 in ankerite core (Supplementary Table S1). Numerous fluid inclusions are confined to the cleavages of the prograde ankerite core and mantle (Fig. 2e). In contrast, the ankerite rim lacks mineral inclusions but contains bead-like secondary fluid inclusions that cross-cut its cleavage direction (Fig. 2f). The Raman spectra clearly show differences among calcite, ankerite and magnesite (Fig. 2g). The characteristic Raman peaks are 1087, 713 and 284 cm−1 for calcite; 1096, 318 and 206 cm−1 for magnesite; and 1096, 723 and 298 cm−1 for ankerite (Fig. 2g).

Amphibole and its inclusions

Amphibole is the main component of the retrograde eclogite, which is almost the retrograde product of omphacite. The Si and XMg [=Mg/(Fe2+ + Mg)] contents vary from 7.7 to 7.0 and from 0.85 to 0.68, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). Thus, the composition changes from actinolite to magnesio-hornblende (Supplementary Fig. S3e). The composition of amphibole inclusions contained in ankerite mantle is actinolite. In contrast, amphibole inclusions contained in the ankerite rim changed to hornblende, which is comparable to that of the matrix rim (Supplementary Fig. S3e). We also identified a large number of fluid inclusions in the retrograde amphibole (Fig. 3a, b).

a A large number of fluid inclusions observed in actinolite. The fluid inclusions grow along their long-axis directions. b Enlarged image showing numerous fluid inclusions with oriented distribution in retrograde amphibole (Amp). The fluid inclusions can be divided into Type-1 and Type-2 fluids. c Ankerite (Ank) and actinolite (Act) porphyroblasts are in equilibrium, and Ank is cut by paragonite (Pg). d Enlarged images showing the presence of fluid inclusions in actinolite (Act). e, f Hyperspectral confocal Raman maps showing the presence of CH4 in fluid inclusions in the Ank core and Act, whose locations marked in squares in (c) and (d). g–j Representative images and the corresponding sketches showing the presence of two types CH4-rich fluid inclusions in Ank and Act, respectively. k The coexistence of Type-1 of H2O-rich fluid inclusions and Type-2 of CH4-rich fluid inclusions in garnet (Grt) mantle. l Symbiotic fluid inclusions had significantly different ratios of CH4/H2O in the rim of omphacite (Omp). The insert enlarged images show the Type-1 and Type-2 fluid inclusions. The coexistence of Type-1 and Type-2 fluid inclusions demonstrates that immiscible fluid phases must have occurred during HP metamorphism.

Two types of fluid inclusions in ankerite and amphibole

The fluid inclusions first observed in ankerite (Figs. 2e, f and 3e) and actinolite (Fig. 3a–d, f) can be categorized into Type-1 and Type-2. Type-1 inclusions are H2O-rich, containing liquid phase with bubbles (Fig. 3g, i). Raman measurements indicate that Type-1 fluid inclusions in amphibole and ankerite are H2O-rich, exhibiting a characteristic broad peak at 3440 cm−1. They also contain vapor CH4 with sharp Raman peaks range from 2916 to 2918 cm−1, along with weaker bands around 2331–2328 cm−1, indicating the presence of minor N2 (Fig. 4). Occasionally, daughter crystals such as calcite and graphite show weak peaks at 1087 and 1583 cm−1, respectively. In contrast, Type-2 inclusions are CH4-rich, with short columnar, elliptoid or irregular shape, composed of pure gas phase (Fig. 3h, j). The Raman peaks of CH4 in Type-2 fluid inclusions range from 2913 to 2915 cm−1, which are lower than those observed in Type-1 fluid inclusions (Fig. 4). There is also N2 with relatively weaker Raman bands at ~2330 cm−1 (Fig. 4). There is no detectable H2O at room temperatures in Type-2 inclusions, although a thin film of H2O may exist on the inner surface of the fluid inclusions.

a in host ankerite. b in host actinolite. The black and blue Raman peaks represent the full spectrum of the host mineral and the liquid phase of H2O peaks, respectively; the purple and red Raman peaks are corresponding to the gas phase. The inset images are electron micrographs of the fluid inclusions showing the existence of the two types of fluid inclusions. The inset Raman spectra are the retest results to confirm the existence of CH4.

We also employed 3D Raman imaging to vividly illustrate the two novel types of fluid inclusions that were discovered (Fig. 5). The outcomes of 3D modeling are consistent with our petrological observations (Figs. 3 and 4). Type-1 fluid inclusions, present in both actinolite (Fig. 5a) and ankerite (Fig. 5b), are characterized by a liquid H2O phase accompanied by CH4 bubbles. In contrast, Type-2 fluid inclusions, found in actinolite (Fig. 5c) and ankerite (Fig. 5d, e), are comprised solely of gas phase CH4 and N2.

Type-1 of H2O-rich fluid inclusions consist of liquid H2O phase and CH4 bubbles both in amphibole (a) and ankerite (b). Type-2 of CH4-rich fluid inclusions composed of gas phase CH4 and N2 both in amphibole (c) and ankerite (d, e) respectively. It should be noted that the CH4 bubbles in (b) are very active, and the 3D Raman did not capture the methane signal. We added the methane bubbles based on the position of methane observed under the polarized light microscope.

Two types of fluid inclusions in garnet and omphacite

The fluid inclusions in the core of garnet and omphacite are homogeneous, comprising H2O liquid with CH4 vapor, akin to previous reports on CH4–H2O fluid inclusions in garnet and omphacite from the prograde to peak metamorphic stage24. However, the fluid in the outer mantle of the garnet displays two distinct types of fluid inclusions (Fig. 3k). Echoing those found in ankerite and amphibole, Type-1 inclusions are rich in H2O, featuring liquid H2O phase with CH4 bubbles and occasionally N2. Conversely, Type-2 inclusions are rich in CH4, predominantly consisting of CH4 and N2, with only a minor quantity of water (Fig. 3k and Supplementary Fig. S5). Fluid inclusions in omphacite, likewise, exhibit distinct CH4/H2O ratios (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. S5). It is noteworthy that Type-1 fluid inclusions were also detected in paragonite inclusion that contained in garnet (Fig. 3k), marking the first report of CH4-bearing fluid inclusions in white mica from the Western Tianshan subduction zone.

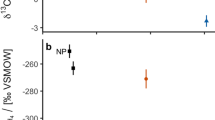

The carbon and hydrogen isotope composition of CH4 released from garnet and omphacite in the retrograde eclogite sample HB142-1 has been reported in ref. 24. The δ13C values of CH4 range from −29.7‰ to −30.2‰, while the δ2H values fall between −370.6‰ and −363.7‰24. These δ13C and δ2H values for CH4 extracted from the Western Tianshan eclogites are notably consistent, positioning entirely in the range indicative of potentially abiotic origin of CH424.

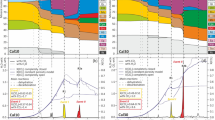

The conditions and origin of immiscible H2O–CH4 fluids in subduction zone

The P–T conditions of the carbonated eclogite sample HB142-1 were calculated by the phase equilibrium modeling and Raman spectroscopic carbonaceous material thermometry25 (Fig. 6a). The P–T pseudosections were contoured with Fe# [=Fe2+/(Mg + Fe2+)] isopleth for ankerite and magnesite (Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7). The intersection of Fe# isopleths from the ankerite core and its prograde magnesite inclusions record prograde metamorphism at ~1.9 GPa and 480 °C, a temperature estimate that is corroborated by the 460–500 °C range from graphite solid inclusions contained in ankerite core25. The presence of coesite pseudomorphs in the mantle of garnet (Supplementary Fig. S5a, b) and ankerite (Supplementary Fig. S3b) suggests that the sample was subjected to UHP conditions. Despite the limitations of the ankerite solid solution model in calculating the UHP condition of the eclogite, the residual magnesite inclusions in the ankerite mantle can document UHP conditions at ~2.8 GPa and 550–580 °C by intersecting their Fe# isopleths with the quartz-coesite transition line (Supplementary Fig. S7). Petrological observations indicate that the garnet rim is in equilibrium with the ankerite rim, pointing to a corresponding P–T condition of 1.8–2.1 GPa and 580 °C for the ankerite rim (Supplementary Fig. S7). This temperature estimate is also consistent with the 540–580 °C range obtained from the Raman spectroscopy analysis of graphite solid inclusions contained in ankerite rim25. Additionally, the calculated oxygen fugacity values range from 2.15 to 1.19 log units below the Fayalite–Magnetite–Quartz buffer (FMQ-2.5–FMQ-1.19; see “Methods” section for details). This indicates a reducing environment, which is also consistent with the presence of abiotic CH4 (Figs. 2–5).

a The boundary of miscibility and immiscibility of H2O and CH4 under HP-UHP conditions defined by petrological observation. b The critical curves of the low-pressure (<0.3 GPa) section modified after refs. 29,44,45. The high-pressure section modified after refs. 30,31. The metamorphic facies diagram is modified after ref. 59 The purpler area is the P–T path range of the subducted slab surface in the W1300 model from ref. 60, and the yellow green area is the P–T range recorded by the exhumed natural blueschist and eclogite from ref. 59.

The fluid inclusions in the core of garnet and omphacite are homogeneous, comprising a single type of fluid inclusion. However, the outer mantle region exhibits a transition to two distinct types of inclusions, which implies that phase separation took place during the decompression process. Furthermore, the fluid inclusions in the retrograde actinolite maintain the elongated orientation characteristic of the precursor omphacite, as illustrated in Fig. 3a, b. This observation suggests that the initial mixed fluid separated into Type-1 H2O-rich and Type-2 CH4-rich fluid inclusions due to decompression. These two types of inclusions represent two immiscible phases that have separated from a common precursor fluid. Therefore, based on the spatial distribution of the coexisting CH4-rich and H2O-rich fluid inclusions—found in the core of the prograde ankerite (Fig. 2a, e), in the retrograde amphibole (Fig. 3a–d), in the retrograde ankerite rim (Fig. 2a, f), and in the outer mantle of garnet and omphacite (Fig. 3k, l)—it is evident that the formation of Type-1 inclusions occurred synchronous with Type-2 inclusions in their respective host minerals. This suggests that the immiscible gap for CH4 and H2O in the Western Tianshan subduction zone is constrained to 1.8–2.1 GPa, 480–590 °C (Fig. 6).

Moreover, the Raman shift of CH4 is sensitive to variations in pressure (and temperature) and could be used to determine its density and partial pressure26. In Type-2 fluid inclusions, the Raman shift of CH4 ranges from 2913 to 2915 cm−1, which is lower than the 2916–2918 cm−1 range noted in Type-1 inclusions (Fig. 4). This lower Raman shift in Type-2 inclusions is indicative of a higher partial pressure26, suggesting that these inclusions captured under subduction zone conditions. Therefore, the synchronous coexistence of Type-1 and Type-2 fluid inclusions provides compelling evidence that two distinct, immiscible fluid phases must have occurred during the HP metamorphism.

Additional field observations have revealed that interlayered eclogite facies rocks from the Münchberg massif contain immiscible CH4 and H2O fluids at conditions of 630 °C, 1.7–2.4 GPa27. Furthermore, recent experimental studies have shown that an increase in pressure can significantly expand the immiscibility gap in C–H–O fluids19,20. For example, immiscible hydrocarbon fluids can form from an initial sodium formate solution under conditions of 1.5–2.5 GPa and 600–700 °C, whereas such formation is not observed at the lower pressure condition of 0.2 GPa19,20. Recent solubility experiments also indicate phase separation of CH4 and H2O at 1.3 GPa due to the low solubility of CH4 in H2O; however, at P > 2 GPa, the solubility of CH4 in H2O can exceed 35 mol% at low temperature28. This is consistent with our observation that the mixed H2O–CH4 fluid inclusions were observed in the conditions of 2.2–3.5 GPa during the prograde to peak metamorphism24, and the occurrence of Type-2 CH4-rich fluids below 2.1 GPa in this study. Therefore, the immiscibility gap for methane should be between 1.3 and 2.1 GPa in subduction zone, with pressures that are either too low or too high being unfavorable for the immiscibility of CH4 and H2O.

It is to note, due to the changes in temperature and pressure conditions caused by retrograde metamorphism, fluid inclusions will inevitably undergo phenomena such as necking or selective leakage. Necking predominantly alters the morphology of the inclusion, manifesting as a reduction in diameter or division into smaller entities29,30,31,32,33. Selective leakage, on the other hand, typically results in the expulsion of gaseous constituents from the inclusion, whilst retaining liquid components29,30,31,32,33. However, this study documents a significant occurrence of Type-2 pure methane gas inclusions (Figs. 3–5 and Supplementary Fig. S5), which demarcate distinct phases, unequivocally evidencing the presence of immiscibility phenomena.

The mechanisms for the formation of CH4

Abiotic CH4 is prevalent in various geological settings, including Precambrian crystalline shields, volcanic and geothermal systems, crystalline intrusions, serpentinized ultramafic rocks, and within olivine-hosted fluid inclusions in mafic, ultramafic, and even dolomitic marbles34,35,36,37,38,39,40. In mafic eclogites, the reduction of the ankerite under conditions of low oxygen fugacity is considered the primary mechanism for the genesis of abiotic CH424,36. The oxygen fugacity of eclogites from the Western Tianshan oceanic crust can be as low as FMQ-2.4–FMQ-3.524, suggesting that CH4 is the dominant carbon species in such a reduced environment, as inferred from field observations24,36,38 and DEW modeling41. Additionally, we have observed the texture of prograde ankerite core decomposition to calcite, magnesite, magnetite, and graphite (Supplementary Fig. S4). This reaction can be summarized as:

In addition, talc is not easily preserved in eclogite. Fortunately, well-preserved talc together with graphite and calcite inclusions have been found in residual ankerite core in this study (Fig. 2a–d). Our observations indicate that a reaction involving talc, graphite and calcite decomposition to ankerite, quartz and CH4 (Fig. 2). This reaction could be written as:

Moreover, the prograde ankerite core has been replaced by a newly formed ankerite mantle and quartz (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. S3). Thus, the reaction can also be expressed as:

Recent experimental evidence supports the kinetics-controlled Ca-carbonate to CH4 in aqueous fluids in subduction zones, demonstrating that silicate involvement and/or increased pressure can accelerate the reaction rates through short-lived fluid–rock interactions42. In addition, silicate dissolution boosts the CO2 or CH4 concentrations in subduction zone fluids, probably associated with the formation of complexes containing Si–O–C bonds43.

We have observed abundant fluid inclusions in retrograde garnet, omphacite, ankerite and amphibole (Figs. 2–5), along with graphite and hydrous minerals such as lawsonite, chlorite, talc and actinolite as inclusions in the residual ankerite core (Fig. 2a, b). This further demonstrates that the reaction of graphite and hydrous silicate minerals is an important mechanism to generate abiotic CH424. Graphite provides the carbon source, while silicate minerals supply the hydrogen necessary for forming abiotic CH4. The reactions observed in this study can be represented as:

Therefore, the occurrence of these reaction textures indicates that the reactions between C-bearing minerals (carbonate and graphite) and hydrous silicate (talc, lawsonite, chlorite and actinolite) can yield CH4 during HP–UHP metamorphism.

The critical curves of H2O‒CO2, H2O‒CH4 and H2O‒N2 binary systems

To enhance the global significance of this study on the immiscibility of C–O–H fluids, we have compiled data across various binary systems—encompassing H2O‒CO2, H2O‒CH4 and H2O‒N2—and obtained critical curves spanning from low pressure29,44,45 to high pressure30,31. The H2O‒CH4 (and H2O‒N2) system generally exhibits higher temperature of immiscibility compared to the H2O‒CO2 system (Fig. 6b). The immiscible gap for H2O‒CO2 is narrower compared to that of the H2O‒CH4 system. At pressures below 0.3 GPa, the critical curve slopes of H2O‒CO2 and H2O‒CH4 shift, which restricts their miscibility ranges to mostly below 450 °C. This corresponds to lower-grade metamorphism beneath greenschist facies (Fig. 6b) and is consistent with previous experimental results, thermodynamic calculations and petrological observations17,18,32. Conversely, under high pressures, the critical curves for both H2O‒CO2 and H2O‒CH4 binary systems incline positively, indicating an expansion of their immiscibility gap with increasing pressure (Fig. 6b). Thus, even at temperatures exceeding 400 °C with HP conditions up to eclogite facies, CH4 and H2O can remain immiscible, as evidenced by the immiscible Type-1 and Type-2 fluid inclusions observed in this study (Figs. 2–5). The P–T conditions recorded by ankerite core are plotted near the H2O‒CH4 binary critical curve (Fig. 6b), suggesting that the fluid composition closely resembles the H2O‒CH4 binary system. The P–T conditions recorded by the mantle of garnet, ankerite and amphibole are in the range of immiscible experiments19, but a little far from the H2O‒CH4 binary critical curve (Fig. 6b), possibly due to the presence of additional components such as N2 (see the Supplementary Material) and salt, as the addition of salt can significantly increase the gap of immiscible fluids19,33. The micro-thermometry data have revealed that the salinity of the majority fluid inclusions in the Western Tianshan ranges from 0.72 to 4.49 wt% NaCl46,47. Additionally, analyses of apatite in eclogites and HP veins in the Western Tianshan have indicated a little chlorine content and a relatively higher fluorine content47,48, further validating the low salinity of eclogitic fluids. The actual fluids in the subduction zone are anticipated to be more complex potentially containing additional components like organic hydrocarbons, including ethane, acetic acid, isobutane and others49. Water-rich fluids containing these hydrocarbons may form coexisting immiscible fluids20 and undergo phase separation under appropriate conditions.

Implications for carbon flux and mobility in subduction zones

In subduction zone, the input carbon flux from sediment is 57–60 MtC/yr, from oceanic crust is 18–25 MtC/yr, and from the lithospheric mantle is 1.3–10 MtC/yr1,2. The output flux from volcanic island arcs is 23 MtC/yr50. However, previous carbon flux studies have predominantly focused on CO2 and neglected CH4. It is estimated that a global CH4 flux of 10.8 Mt/y can be released from modern subduction zones24, which translates to carbon is 8.1 MtC/yr. Consequently, the proportion of the carbon flux released by eclogites as methane is not negligible, significantly exceeding the outputs of abiotic CH4 released by HP serpentinization (<1.5 Mt/y)21 and mid-ocean ridge (1.1–1.9 Mt/y)51. This substantial quantity of abiotic CH4 that could significantly contribute to the formation of hydrocarbon reservoirs. The question remains, however, whether this substantial subduction-generated abiotic CH4 can upward migrate to the shallow crust and accumulate in reservoir. The observed immiscibility of H2O–CH4 fluids under cold subduction zone conditions in this study suggests a critical mechanism that may drive natural gas migration and accumulation.

Under HP metamorphic condition in subduction zones, such as ~2 GPa and 550 °C reported in this study, which significantly surpass the critical point of CH4, the Type-2 pure CH4 is predicted to exist in a supercritical fluid state41. Supercritical fluids are characterized by properties that are intermediate between those of gases and liquids. For instance, they can penetrate porous materials like a gas but dissolve substances like a liquid52. This dual nature makes supercritical methane an effective agent for transporting carbon upwards to the mantle wedge. Owing to the less dense, tends to rise and can carry dissolved carbon along with it, effectively removing carbon from subduction zone fluids53. The immiscibility of H2O and CH4 will further expand the efficiency of decarbonization19. As a result, the actual mass of slab carbon transferred to the mantle wedge along cracks, veins, shear zones, or fold hinges54,55,56 should be considerably larger than the mass of carbon apparently dissolved in the H2O-rich fluids. The methane emitted from mud volcanoes, which widely distributed in the Alpes-Tethys suture zone and the Pacific Rim, is believed to be related to fluid immiscibility in subduction zones56. Accordingly, the estimation of carbon flux should be revisited to account for immiscibility and demethanization phenomena in subduction zones. The upward migration of supercritical immiscible CH4 could be a key factor in the formation of potential abiotic natural gas deposits. Notably, the deep and ultra-deep natural gases have been identified along the southern margin of the Junggar Basin, located near the northern edge of the Western Tianshan subduction zone. Some of these gases exhibit abiotic carbon isotope characteristics ranging from −26.8‰ to −11.2‰57. This further suggesting that a portion of these abiotic CH4 gases may originate from the immiscible CH4 fluids in the subduction zone.

Methods

Major element compositions and scanning electron microscope analysis

Major element and Raman spectroscopy analysis were both conducted at Peking University. The former was performed on a JEOL JXA-8230 electron microprobe using a 15 kV acceleration voltage and 10 nA beam current. The beam diameter was set to 2 μm for silicates and 10 μm for carbonates. Backscattered electron (BSE) images were acquired by utilizing a Quanta 200F ESEM scanning electron microscope (SEM) at Peking University with a 2 min scanning time under conditions of 15 kV and 120 nA to characterize internal structures and determine locations as guidance for analysis.

Raman spectroscopy analysis and 3D imaging

Raman spectroscopy was performed on a HORIBA Jobin Yvon confocal LabRAM HR Evolution micro-Raman system equipped with a frequency-doubled green Nd-YAG laser (532 nm). The laser spot size was focused to 1 μm and the accumulation time varied between 60 and 120 s. The estimated spectral resolution was >1.0 cm−1 and the calibration used synthetic silicon. Hyperspectral Raman images were collected along a regular grid of points, nearly equidistant in both directions, with a computer-controlled, automated X–Y mapping stage. The details are in ref. 24. 3D imaging of fluid inclusions was performed using a WITec alpha300R confocal Raman microscope (WITec GmbH) with 532 nm cobalt laser excitation at the Center for High Pressure Science & Technology Advanced Research. The energy of the laser source was between 10 and 20 mW, and the spectral collection range was 100–3600 cm−1. The spatial resolution of single-point acquisitions along the x and y axis was 0.3 μm and 0.3 μm, while that along the z axis was between 0.5 and 0.8 μm. The time of single-point acquisitions was 1–2 s, and the time of single-inclusion scanning was ~15–20 h. 3D imaging and modeling analyses of the fluid inclusions were performed using Image J software.

P–T and oxygen fugacity conditions calculated for the carbonated eclogite

The P–T conditions of the carbonated eclogite sample HB142-1 were calculated using the Perple_X software of version 6.7.49 and Raman spectroscopic carbonaceous material thermometry25. The details are shown in Supplementary Notes and Figs. S6, S7. The Fe3+/∑Fe ratio in a representative garnet that contained omphacite inclusions in garnet core was measured by the flank method58 with the JEOL JXA-8100 electron microprobe at the Key Laboratory of Orogenic Belts and Crustal Evolution, School of Earth and Space Sciences, Peking University, China. The detailed analytical procedure of the flank method followed ref. 24. We calculated fO2 at 560 °C and 27.5 kbar and 580 °C and 22 kbar, corresponding to garnet core and rim, respectively. The compositions of the garnet and the calculated fO2 results are listed in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3, respectively.

Data availability

All data are included in the main text and Supplementary file.

References

Dasgupta, R. & Hirschmann, M. M. The deep carbon cycle and melting in Earth’s interior. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 298, 1–13 (2010).

Kelemen, P. B. & Manning, C. E. Reevaluating carbon fluxes in subduction zones, what goes down, mostly comes up. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3997–4006 (2015).

Plank, T. & Manning, C. E. Subducting carbon. Nature 574, 343–352 (2019).

Stewart, E. M. & Ague, J. J. Pervasive subduction zone devolatilization recycles CO2 into the forearc. Nat. Commun. 11, 6220 (2020).

Lan, C. Y., Tao, R. B., Huang, F., Jiang, R. Z. & Zhang, L. F. High-pressure experimental and thermodynamic constraints on the solubility of carbonates in subduction zone fluids. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 603, 117989 (2023).

Molina, J. F. & Poli, S. Carbonate stability and fluid composition in subducted oceanic crust: an experimental study on H2O-CO2-bearing basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 176, 295–310 (2000).

Kerrick, D. M. & Connolly, J. A. D. Metamorphic devolatilization of subducted marine sediments and the transport of volatiles into the earth’s mantle. Nature 411, 293–296 (2001).

Kerrick, D. M. & Connolly, J. Metamorphic devolatilization of subducted oceanic metabasalts: implications for seismicity, arc magmatism and volatile recycling. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 189, 19–29 (2001).

Connolly, J. A. D. Computation of phase equilibria by linear programming: a tool for geodynamic modelling and its application to subduction zone decarbonation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 236, 524–541 (2005).

Gorman, P. J., Kerrick, D. M. & Connolly, J. A. D. Modeling open system metamorphic decarbonation of subducting slabs. Geochem. Geophys. Gesyst. 7, Q04007 (2006).

Tian, M., Katz, R. F. & Jones, D. W. R. Devolatilization of subducting slabs, Part I: Thermodynamic parameterization and open system effects. Geochem. Geophys. Gesyst. 20, 5667–5690 (2019).

Tian, M., Katz, R. F. & Jones, D. W. R. Devolatilization of subducting slabs, Part II: Volatile fluxes and storage. Geochem. Geophys. Gesyst. 20, 6199–6222 (2019).

Poli, S. Carbon mobilized at shallow depths in subduction zones by carbonatitic liquids. Nat. Geosci. 8, 633–636 (2015).

Poli, S. Melting carbonated epidote eclogites: carbonates from subducting slabs. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 3, 27 (2016).

Frezzotti, M. L., Selverstone, J., Sharp, Z. D. & Compagnioni, R. Carbonate dissolution during subduction revealed by diamond-bearing rocks from the Alps. Nat. Geosci. 4, 703–706 (2011).

Ague, J. J. & Nicolescu, S. Carbon dioxide released from subduction zones by fluid-mediated reactions. Nat. Geosci. 7, 355 (2014).

Holloway, J. R. Graphite-CH4–H2O–CO2 equilibria at low-grade metamorphic conditions. Geology 12, 455–458 (1984).

Huizenga, J. M. Thermodynamic modelling of C-O-H fluids. Lithos 55, 101–114 (2001).

Li, Y. Immiscible C-H-O fluids formed at subduction zone conditions. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 3, 12–21 (2017).

Huang, F., Daniel, I., Cardon, H., Montagnac, G. & Sverjensky, D. A. Immiscible hydrocarbon fluids in the deep carbon cycle. Nat. Commun. 8, 15798 (2017).

Brovarone, A. V. et al. Massive production of abiotic methane during subduction evidenced in metamorphosed ophicarbonates from the Italian Alps. Nat. Commun. 8, 14134 (2017).

Shi, G., Tropper, P., Cui, W., Tan, J. & Wang, C. Methane (CH4)-bearing fluid inclusions in the Myanmar jadeitite. Geochem. J. 39, 503–516 (2005).

Zhang, L. F., Wang, Y., Zhang, L. J. & Lü, Z. Ultrahigh pressure metamorphism and tectonic evolution of Southwestern Tianshan Orogenic Belt, China: a comprehensive review. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 474, 133–152 (2018).

Zhang, L. J. et al. Massive abiotic methane production in eclogites during cold subduction. Natl. Sci. Rev. 10, nwac207 (2023).

Rahl, J. M., Anderson, K. M., Brandon, M. T. & Fassoulas, C. Raman spectroscopic carbonaceous material thermometry of low-grade metamorphic rocks: calibration and application to tectonic exhumation in Crete, Greece. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 240, 339–354 (2005).

Zhang, J. L. et al. An equation for determining methane densities in fluid inclusions with Raman shifts. J. Geochem. Explor. 171, 20–28 (2016).

Klemd, R., van den Kerkhof, A. M. & Horn, E. E. High density CO2-N2 inclusions in eclogite facies metasediments of the Münchberg gneiss complex, SE Germany. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 111, 409–419 (1992).

Pruteanu, C. G., Ackland, G. J., Poon, W. C. & Loveday, J. S. When immiscible becomes miscible—methane in water at high pressures. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700240 (2017).

Hurai, V. Fluid inclusion geobarometry: pressure corrections for immiscible H2O–CH4 and H2O–CO2 fluids. Chem. Geol. 278, 201–211 (2010).

Churakov, S. V. & Gottschalk, M. Perturbation theory based equation of state for polar molecular fluids II. Fluid mixtures. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 2415–2425 (2003).

Abramson, E. H., Bollengier, O. & Brown, J. M. The water-carbon dioxide miscibility surface to 450 °C and 7 GPa. Am. J. Sci. 317, 967–989 (2017).

Yardley, B. W. D. & Bottrell, S. H. Immiscible fluids in metamorphism: implications of two-phase fluid flow for reaction history. Geology 16, 199–202 (1988).

Heinrich, W. Fluid immiscibility in metamorphic rocks. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 65, 389–430 (2007).

Etiope, G. & Lollar, B. S. Abiotic methane on earth. Rev. Geophys. 51, 276–299 (2013).

Etiope, G. & Schoell, M. Abiotic gas: atypical, but not rare. Elements 10, 291–296 (2014).

Tao, R. B. et al. Formation of abiotic hydrocarbon from reduction of carbonate in subduction zones: constraints from petrological observation and experimental simulation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 239, 390–408 (2018).

Boutier, A., Vitale Brovarone, A., Martinez, I., Sissmann, O. & Mana, S. High pressure serpentinization and abiotic methane formation in metaperidotite from the Appalachian subduction, northern Vermont. Lithos 396, 106190 (2021).

Peng, W. G. et al. Abiotic methane generation through reduction of serpentinite-hosted dolomite: implications for carbon mobility in subduction zones. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 311, 119–140 (2021).

Klein, F., Grozeva, N. G. & Seewald, J. S. Abiotic methane synthesis and serpentinization in olivine-hosted fluid inclusions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 17666–17672 (2019).

Harada, H. & Tsujimori, T. Methane genesis within olivine-hosted fluid inclusions in dolomitic marble of the Hida Belt, Japan. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 11, 1186 (2024).

Guild, M. & Shock, E. L. Predicted speciation of carbon in subduction zone fluids. In Carbon in Earth’s Interior, Geophysical Monograph 1st edn, Vol. 249 (eds Manning, C. E., Lin, J.-F., & Mao, W. L.) ch. 24, pp. 285–302 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2020).

Peng, W. G. et al. An experimental study on kinetics-controlled Ca-carbonate aqueous reduction into CH4 (1 and 2 GPa, 550 °C): implications for C mobility in subduction zones. J. Petrol. 63, 1–18 (2022).

Tumiati, S. et al. Silicate dissolution boosts the CO2 concentrations in subduction fluids. Nat. Commun. 8, 616 (2017).

Diamond, L. W. Introduction to gas-bearing, aqueous fluid inclusions. In Fluid Inclusions: Analysis and Interpretation Vol. 32, 101–158 (Mineralogical Association of Canada, 2003).

Kaszuba, J. P., Williams, L. L., Janecky, D. R., Hollis, W. K. & Tsimpanogiannis, I. N. Immiscible CO2‐H2O fluids in the shallow crust. Geochem. Geophys. Gesyst. 7, Q10003 (2006).

Gao, J. & Klemd, R. Primary fluids entrapped at blueschist to eclogite transition: evidence from the Tianshan meta-subduction complex in northwestern China. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 142, 1–14 (2001).

Gao, J., John, T., Klemd, R. & Xiong, X. Mobilization of Ti–Nb–Ta during subduction: evidence from rutile-bearing dehydration segregations and veins hosted in eclogite, Tianshan, NW China. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 4974–4996 (2007).

Zhang, L. J., Zhang, L. F., Lu, Z., Bader, T. & Chen, Z. Y. Nb-Ta mobility and fractionation during exhumation of UHP eclogite from southwestern Tianshan, China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 122, 136–157 (2016).

Sverjensky, D., Daniel, I. & Brovarone, A. V. The changing character of carbon in fluids with pressure: organic geochemistry of Earth’s upper mantle fluids. In Carbon in Earth’s Interior, Geophysical Monograph 1st edn, Vol. 249 (eds Manning, C. E., Lin, J.-F., & Mao, W. L.) ch. 22, pp. 259–269 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2020).

Bekaert, D. V. et al. Subduction-driven volatile recycling: a global mass balance. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 49, 37–70 (2021).

Merdith, A. S. et al. Pulsated global hydrogen and methane flux at mid-ocean ridges driven by Pangea breakup. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 21, e2019GC008869 (2020).

Ni, H. W., Zhang, L., Xiong, X. L., Mao, Z. & Wang, J. Y. Supercritical fluids at subduction zones: evidence, formation condition, and physicochemical properties. Earth Sci. Rev. 167, 62–71 (2017).

Bali, E., Audétattattat, A. & Keppler, H. Water and hydrogen are immiscible in Earth’s mantle. Nature 495, 220–222 (2013).

Ague, J. Fluid flow in the deep crust. Treat. Geochem. 4, 203–239 (2014).

Bebout, G. E. & Penniston-Dorland, S. C. Fluid and mass transfer at subduction interfaces—the field metamorphic record. Lithos 240, 228–258 (2016).

Dai, J. X. et al. Geochemical characteristics of natural gas from mud volcanoes in the southern Junggar Basin. Sci. China Earth Sci. 42, 178–190 (2012).

Gong, D. Y. et al. Discovery of multi-types of natural gases in the eastern Junggar basin and its implication for petroleum exploration. Acta Geol. Sin. 97, 19672 (2023).

Hofer, H. E. & Brey, G. P. The iron oxidation state of garnet by electron microprobe: its determination with the flank method combined with major-element analysis. Am. Mineral. 92, 873–885 (2007).

Penniston-Dorland, S. C., Kohn, M. J. & Manning, C. E. The global range of subduction zone thermal structures from exhumed blueschists and eclogites: rocks are hotter than models. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 428, 243–254 (2015).

Syracuse, E. M., van Keken, P. E. & Abers, G. A. The global range of subduction zone thermal models. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 183, 73–90 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Professor Rixiang Zhu, Huajian Wang and Wang Zhang from the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences for their insightful discussions. Thanks to Professor Yong Tang from the Xinjiang Branch of China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) for the inspiration from his report. We thank two anonymous reviewers and another two anonymous reviewers for the early version for their constructive reviews and to the senior editor Teresa Schauperl for her careful editorial handling and helpful suggestions. This study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFA0708501) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42172060). This is a contribution to the project of Theory of Hydrocarbon Enrichment under Multi-Spheric Interactions of the Earth (THEMSIE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.J.Z. and L.F.Z. designed research; L.J.Z. collected the samples and performed research; L.J.Z. and X.W. analyzed data; L.J.Z. and N.Q. performed the 3D analysis; L.J.Z. wrote the paper; and L.J.Z., Y.L., and L.F.Z. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Tatsuki Tsujimori and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Qi, N., Li, Y. et al. Immiscible metamorphic water and methane fluids preserved in carbonated eclogite. Commun Chem 7, 267 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01355-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01355-4

This article is cited by

-

High-pressure chemistry

Communications Chemistry (2025)